Abstract

Purpose

Numerous organizations recommend that patients with cancer receive a survivorship care plan (SCP) comprising a treatment summary and follow-up care plans. Among current barriers to implementation are providers’ concerns about the strength of evidence that SCPs improve outcomes. This systematic review evaluates whether delivery of SCPs has a positive impact on health outcomes and health care delivery for cancer survivors.

Methods

Randomized and nonrandomized studies evaluating patient-reported outcomes, health care use, and disease outcomes after delivery of SCPs were identified by searching MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Cochrane Library. Data extracted by independent raters were summarized on the basis of qualitative synthesis.

Results

Eleven nonrandomized and 13 randomized studies met inclusion criteria. Variability was evident across studies in cancer types, SCP delivery timing and method, SCP recipients and content, SCP-related counseling, and outcomes assessed. Nonrandomized study findings yielded descriptive information on satisfaction with care and reactions to SCPs. Randomized study findings were generally negative for the most commonly assessed outcomes (ie, physical, functional, and psychological well-being); findings were positive in single studies for other outcomes, including amount of information received, satisfaction with care, and physician implementation of recommended care.

Conclusion

Existing research provides little evidence that SCPs improve health outcomes and health care delivery. Possible explanations include heterogeneity in study designs and the low likelihood that SCP delivery alone would influence distal outcomes. Findings are limited but more positive for proximal outcomes (eg, information received) and for care delivery, particularly when SCPs are accompanied by counseling to prepare survivors for future clinical encounters. Recommendations for future research include focusing to a greater extent on evaluating ways to ensure SCP recommendations are subsequently acted on as part of ongoing care.

INTRODUCTION

A seminal Institute of Medicine report identified the transition from active to post-treatment care as being critical to the long-term health of cancer survivors.1 The same report also noted that many patients become “lost in transition” and do not receive the follow-up care they should.1 Among the proposed solutions was a recommendation that, when active treatment ends, all patients receive a survivorship care plan (SCP) that includes a treatment summary as well as a follow-up care plan that addresses topics such as surveillance for recurrence or new cancer, assessment and treatment or referral for persistent effects, evaluation of risk for and prevention of late effects, health promotion, and coordination of care.1

Routine delivery of SCPs has been endorsed by professional organizations (eg, ASCO),2 accrediting bodies (eg, American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer),3 and voluntary health organizations (eg, American Cancer Society).4 However, surveys suggest adoption has been limited.5,6 Reasons provided for limited adoption include the time and resources required to prepare SCPs, lack of reimbursement for preparing SCPs, and coordination challenges with primary care providers.2,7,8 Concerns also include the perceived lack of evidence that SCPs improve outcomes.8,9

In light of concerns about the merits of delivering SCPs, we conducted a systematic review designed to determine what can be learned from published evidence about the impact of SCPs on health outcomes and health care delivery for cancer survivors.

METHODS

Search Strategy

Systematic literature searches were conducted of five databases (ie, PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library) with no specified date, age, sex, or language restrictions. The coverage dates for this review began as follows for each database, and ended for all on July 16, 2017: PubMed/MEDLINE, 1946; Embase, 1947; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, 1976; PsycINFO, 1967; and Cochrane Library, 1993. Keywords were mapped to appropriate controlled vocabulary and subject heading terminology in the development of the search strategies for all databases. The search strategy had four major components, all of which were linked together with the AND operator: cancer terms; SCP terms, including follow-up care, continuous care, and longitudinal care; health and treatment outcome terms, including quality of life, patient satisfaction, screening compliance, survival rate, and psychological factors; and study design and type, including randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials (Appendix, online only). The search strategy used for PubMed/MEDLINE (Appendix,) was adapted for each electronic database. Reference lists from eligible articles and previous reviews of SCP research were also examined to identify publications. In addition, reviewers with expertise in survivorship research (P.B.J., T.A.O., D.K.M., E.D.P., and J.H.R.) nominated additional publications for possible inclusion.

Study Selection

Citations from all search results were downloaded into a reference management software package (EndNote X7.7; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA) and an electronic spreadsheet (Excel 2016; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). After duplicates were eliminated, two paired reviewers independently screened study titles and abstracts and reviewed full-text articles as needed to determine study eligibility. Discussion of discordant eligibility ratings or involvement of a third rater was used to address disagreements. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in English, involved delivery of an SCP to survivors diagnosed with cancer and/or their health care providers, and evaluated patient-reported outcomes (PROs), health care use, or disease outcomes in relation to SCP delivery. For purposes of this review, an SCP was defined as a standardized, multifaceted plan for follow-up or long-term care of cancer survivors who have completed treatment of cancer with curative intent. Randomized studies in which participants in one or more arms received an SCP and nonrandomized studies (using interrupted time series, before and after, and cross-sectional designs) in which all participants received an SCP were eligible for inclusion. Review articles, published abstracts, conference proceedings, and unpublished studies were excluded.

Data Extraction

A standardized electronic spreadsheet was used to extract data on country setting, sample characteristics (ie, size, age, cancer type, and time of participation in relation to cancer diagnosis or treatment completion), study design (ie, aims, number of arms, and timing of outcome assessments), SCP content, delivery and additional intervention elements, features of control or comparison arm(s) as applicable, study outcomes, study measures, and comparisons conducted to evaluate outcomes, results, and conclusions. Two paired reviewers independently entered this information into a spreadsheet and subsequently discussed and resolved discrepancies. Reviewers also independently rated the quality of evidence using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS)10 for nonrandomized studies and items adapted from the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Controlled Trials11 for randomized studies. For the QATQS, selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and global quality were each rated as strong, moderate, weak, or not applicable, on the basis of information included in the published report. For the adapted Cochrane Tool, selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting bias were each rated as being low, high, or unclear, on the basis of information included in the published report. Discussion of discordant quality ratings was used to resolve disagreements.

RESULTS

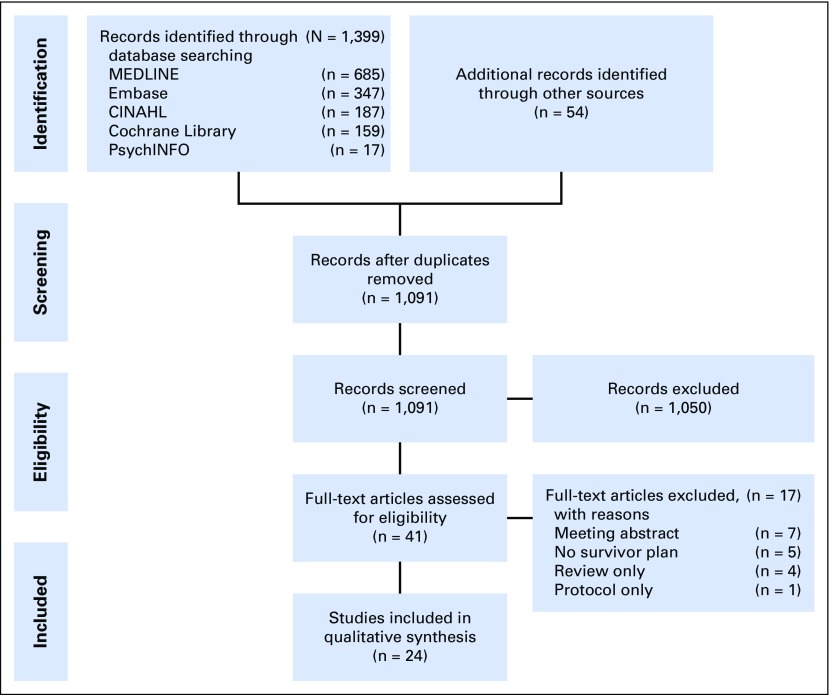

Figure 1 provides details on the study identification, screening, eligibility, and selection process. A total of 1,399 studies were identified through five database searches and 54 additional articles were identified from reference lists and previous reviews. After removing duplicate publications, 1,091 articles were screened for eligibility and 1,050 articles were excluded for not meeting eligibility criteria. The full text of 41 articles was assessed for eligibility, whereupon 17 additional articles were excluded. Agreement on inclusion or exclusion between the two reviewers for the 41 articles was substantial (90%; ĸ = 0.790; 95% CI, 0.594 to 0.985). A total of 24 articles, comprising 11 nonrandomized studies12-22 and 13 randomized studies23-35, were eligible for inclusion in the synthesis. It should be noted that three articles are based on the same study.23,25,27 Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and study findings are summarized in Table 2 for included articles. Given the limited size and marked heterogeneity of the evidence base, analysis focused on qualitative synthesis rather than quantitative synthesis (ie, meta-analysis) of identified literature.

Fig 1.

Diagram of study identification and selection process. CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics (N = 24)

Table 2.

Study Findings (N = 24)

Quality of the Evidence

Table 3 summarizes the QATQS item ratings across the 11 nonrandomized studies. The global rating of study quality was weak for nine studies and moderate for two studies. Consistent with these global ratings, most nonrandomized studies were rated weak for selection bias, study design, and data collection methods.

Table 3.

Quality Ratings for Nonrandomized Studies (N = 11)

Table 4 summarizes the adapted Cochrane Tool risk of bias item ratings within and across the 13 randomized studies. Three studies were notable for a relatively high number of items rated as having a low risk of bias (ie, indicative of more rigorous methodology).27,30,31 In the remainder of the studies, fewer items were rated low risk largely because there was insufficient information to generate a risk rating. Across studies, four aspects of risk were frequently rated low: allocation adequately concealed, baseline outcome assessments similar, baseline characteristics similar, and free of selective outcome reporting. High risk of bias ratings was uncommon except for incomplete outcome data being adequately assessed. Unclear ratings due to insufficient information were common for three aspects of risk: adequate concealment of allocation, adequate prevention of knowledge of allocated intervention by outcome assessors, and adequate protection against contamination.

Table 4.

Risk of Bias Ratings for Randomized Studies (N = 13)

Study Participant Characteristics

We found 17 studies focused on a specific cancer type (breast cancer, n = 9; colorectal cancer, n = 2; lung cancer, n = 2; prostate cancer, n = 1; gynecologic cancer, n = 1; endometrial cancer, n = 1; and Hodgkin lymphoma, n = 1),12,14,16-19,23-30,32-34 two studies focused on two cancer types (breast and colorectal cancer, n = 1; lymphoma and leukemia, n = 1),20,22 and five studies focused on a mix of cancer diagnoses.13,15,21,31,35 Five studies focused on survivors of childhood-onset cancers13,19,21,22,31 and 19 focused on survivors of adult-onset cancers.12,14-18,20,23-30,32-35 Among 23 studies that reported age at participation, the mean or median was between 18 and 39 years in four studies,13,19,21,22 between 40 and 65 years in 17 studies,12,14-18,23-25,27-33,35 and > 65 years in two studies.26,34 Corresponding authors were from the United States in 13 studies,12,14-17,19,21,22,24,30,31,33,35 Canada in six studies,20,23,25,27-29 Australia in three studies,18,26,32 and the Netherlands in two studies.13,34

SCP Characteristics

As noted, 11 nonrandomized studies were identified in which all participants received an SCP and 13 randomized studies were identified in which participants were randomly assigned to conditions that included at least one arm in which an SCP was delivered. In terms of timing of SCP delivery, a distinction can be drawn between studies in which all participants who received an SCP received it within 1 year of treatment completion and studies in which participants received SCPs over wider intervals or longer after treatment completion. Of 23 studies reporting relevant information (eg, time since diagnosis or treatment completion), SCPs were likely all delivered within 1 year of treatment completion in nine studies14,18,20,24,26,30,32,34,35 and otherwise in 14 studies.12,13,16,17,19,21-23,25,27-29,31,33 In addition to a treatment summary, SCPs usually incorporated information about recommended follow-up care. Additional components less commonly incorporated included information on late effects and health care, healthy lifestyle advice, resources for survivorship and supportive care, and assessment of symptoms and unmet needs. Among 23 studies reporting on how SCPs were delivered, methods comprised in-person meetings with participants in 11 studies,14,20,21,23-25,27,30,32-34 in-person meetings or by telephone in one study,18 participant access to websites in seven studies,12,13,15-17,22,35 mail to participants in two studies,19,31 and delivery only to primary care providers (PCPs) in two studies.28,29 Including the last two studies, SCPs were provided to PCPs in 10 studies.13,18,20,23,25,27-29,32,34 Several studies featured additional interactions with participants beyond delivery of SCPs. These included meetings with nutritionists,30 nurse-led counseling and/or coaching,18,31-33 educational classes,20 and planned follow-up visits with PCPs.26

Nonrandomized Study Characteristics and Findings

Among the 11 nonrandomized studies, sample sizes ranged from 10 to 4,021 (median, n = 142). The following outcomes were assessed with study-specific questions administered to participants: satisfaction with care, communication with physician, communication preferences, perceptions of support, evaluation of and reactions to the SCP, receipt of medical services, post-treatment effects, receipt of survivorship care, and knowledge. Two studies used standardized, published PRO measures to assess quality of life, unmet needs, psychological distress, and worry and concern.18,21 Two studies included a baseline (pre-SCP delivery) assessment.18,19 Timing of outcome assessments after SCP delivery in the 11 studies ranged from shortly after delivery to 1 year later.

Results for these studies generally consisted of descriptive statistics characterizing responses to study-generated questions in terms of percentages in various categories. The one exception was an analysis of changes over time in psychological distress scores, which yielded no statistically significant differences.19 Conclusions drawn generally reflected positive evaluations of the feasibility of generating and delivering SCPs, the acceptability to survivors of providing information for SCPs, and survivors’ satisfaction with receiving SCPs.

Randomized Study Characteristics and Findings

Among the 13 randomized studies, the unit of randomization was the participant in 11 studies,23,25-33,35 hospital in one study,34 and oncology practice in one study.24 Sample sizes ranged from 41 to 968 (median, n = 224). The timing of outcome assessments in relation to SCP delivery ranged from shortly after SCP delivery to 5 years after delivery.

Standardized PRO measures or study-specific questions were used in 11 studies to assess patient-reported health states and perceptions of care.23,24,26-30,32-35 Variables assessed in more than one study were quality of life, satisfaction with care, psychological distress, cancer-specific distress, unmet needs, and continuity/coordination of care. No statistically significant differences across intervention conditions were reported in seven studies.23,24,26-28,33,35 Four studies reported findings suggesting beneficial effects of providing SCPs; compared with survivors who did not receive an SCP, those who did reported fewer depressive symptoms,29 less health worry and a less negative outlook,30 greater satisfaction with care,32 and a greater amount of information received.34 One study reported findings suggesting adverse effects of providing SCPs; compared with survivors who did not receive an SCP, those who did reported more symptoms, illness concerns, and emotional impact of illness.34

Six studies assessed health care delivery and use.23,26,27,31,33,34 Outcomes assessed were patient preference for future care, patient identification of the provider responsible for follow-up, adherence to cardiomyopathy screening, health care use, adherence to follow-up recommendations, and physician implementation of survivorship care recommendations. No statistically significant differences across intervention conditions were reported in one study.23 Five studies reported findings suggesting beneficial effects of providing SCPs; compared with survivors who did not receive an SCP, those who did reported a greater preference for shared care,26 greater likelihood of correctly identifying their PCP as responsible for follow-up care,27 greater adherence to cardiomyopathy screening,31 better physician implementation of survivorship care recommendations,33 and more cancer-related contact with their PCP.34

Two studies assessed disease-related end points.28,29 Outcomes assessed were time to diagnosis of recurrence and recurrence-related serious clinical events. No statistically significant differences in either outcome was reported when specialist follow-up care was compared with transfer of follow-up care to a PCP.

Two studies assessed economic end points. In one study, health care costs were reported to be lower in the SCP condition relative to the no-SCP condition.26 In the other study, societal costs and health care costs were higher in the SCP condition relative to the no-SCP condition; however, differences in quality-adjusted life years were negligible.25

DISCUSSION

This work is a comprehensive review of the impact of SCPs on health outcomes and health care delivery. It has a broader scope than previous reviews,36 encompassing several forms of cancer, and includes many more studies of the impact of SCPs on health outcomes and health care delivery than included in previous reviews.37,38

Few conclusions can be drawn about impact of SCPs from the 11 nonrandomized studies that were reviewed, because they were uncontrolled and focused mostly on issues of the feasibility and acceptability of delivering SCPs. Among the 13 randomized studies, most focused on examining the impact of SCPs on patient-reported health states and perceptions of care. These studies generally yielded statistically nonsignificant findings. Among the few significant findings, results suggesting beneficial effects on depressive symptoms, health worry, outlook on life, amount of information received, and satisfaction with care were limited to single studies. Similarly, results suggesting adverse effects on symptom reporting, illness concerns, and emotional impact of illness were limited to a single study. Only six studies reported results for the impact of SCPs on health care delivery and use; however, five of these studies reported significant findings. All the significant findings suggested beneficial effects of SCPs, but, once again, the findings for any specific outcome (eg, physician implementation of survivorship care recommendations) were limited to single studies. The general lack of convergent significant findings across studies seriously limits the extent to which definitive conclusions can be drawn about the impact of SCPs for patient-reported health status, perceptions of care, health care delivery, and health care use. Studies examining disease end points and economic outcomes are too few to draw even tentative conclusions.

Several limitations of the current review deserve mention. These include characteristics of the evidence base (eg, limited number of studies and heterogeneous methodology) that precluded conducting a quantitative synthesis of existing research. Consequently, we were limited to examining whether findings from randomized studies reached statistical significance rather than being able to calculate and aggregate effect sizes irrespective of prespecified significance levels. Additionally, the review was limited to published studies in English and, thus, did not include relevant unpublished studies as well as research in other languages. Finally, the review examined the impact of SCPs only on health outcomes and health care delivery, and did not examine other aspects of SCPs (eg, survivor and provider preferences for SCP content and delivery methods).

Despite these limitations, several recommendations can be offered for future research in survivorship care based on results of this systematic review. First, a better understanding of the impact of SCPs is unlikely until there is greater consistency across studies in the content and delivery of SCPs and the outcomes that are measured. The studies reviewed evaluated SCPs that differed markedly in terms of the follow-up information and care recommendations provided, when they were delivered in relation to treatment completion, and how and to whom they were delivered. There was also little consistency in what outcomes were assessed and even in what measures were used to assess the same outcome (eg, psychological distress).

Second, our review indicates that greater attention needs to be paid to methodological quality. Emphasis should be on randomized studies, given the limited ability to draw definitive conclusions about the impact of SCPs from nonrandomized studies. Future randomized studies of SCPs should be careful to adhere to basic aspects of sound design and analysis, including avoidance of selective reporting of outcomes. Ideally, protocols that prespecify the study’s primary and secondary outcomes should be available and the published report should clearly indicate which analyses are primary and which are secondary or exploratory.

Third, investigators need to give greater thought to the types of outcomes that SCPs are likely to influence. In this context, an important distinction can be made between proximal and distal outcomes.39,40 Studies in this area have tended to focus on more distal outcomes such as survivors’ reports of their health status in the months after delivery of an SCP. More proximal outcomes include survivors’ understanding of survivorship issues and where subsequent care would be delivered. Consistent with this view are results described in the current article showing delivery of SCPs resulted in survivors reporting a greater amount of information received34 and greater likelihood of survivors correctly identifying their PCP as responsible for follow-up care.23 Accordingly, we recommend the adoption of a core set of proximal outcomes in future research on SCPs that includes measures of patient and provider knowledge, communication quality, and understanding of care provider roles. With regard to distal outcomes, results of this review suggest that delivery of SCPs alone is not likely to influence long-term health outcomes. However, sharing and discussing SCPs may positively affect the subsequent behaviors of survivors and their health care providers over an extended period. For survivors, SCPs have the potential to improve their adherence to recommended care (eg, completion of follow-up tests and use of services identified to address cancer’s chronic effects). For providers, SCPs have the potential to improve coordination of care and reduce duplication of services. They can also guide delivery of appropriate services to providers, including services that are not oncology related (eg, age- and risk-specific preventive vaccinations). Adoption of measures that capture the effect of SCP use on these behaviors is recommended for future studies.

Fourth, investigators should consider ways to maximize the impact of the delivery of SCPs. An example is using the delivery of an SCP as an opportunity to coach survivors in how to raise concerns about survivorship issues at subsequent visits with providers. This strategy was used in one of the studies reviewed and resulted in greater physician implementation of SCP recommendations.33 Other possible strategies include periodic review and updating of the SCP with the survivor, ensuring the survivor’s PCP receives a similarly updated document, and brief education on survivorship issues for survivors and their informal caregivers.

Fifth, research on SCPs needs to be situated within the broader context of the delivery of survivorship care. Delivery of SCPs should be viewed as a necessary but not sufficient condition for delivering high-quality cancer care. An SCP is unlikely to be effective if there are no mechanisms in place to implement the plan’s recommendations.41 In addition to providing an SCP to a survivor and his or her health care team, efforts are required to ensure that subsequent care is delivered in a timely and efficient manner consistent with evidence-based standards. Accordingly, research should focus on evaluating the relative benefits of different models of survivorship care, of which delivery of an SCP is but one component. Recent reviews and discussions suggest that key issues requiring additional study include what should be delivered as part of survivorship care, where should it be delivered, and who should deliver it.42,43 Numerous survivorship care models exist44; however, there has been little research to date evaluating their relative strengths and weaknesses.42,43,45 Although there is a growing consensus that survivorship care should be shared between oncology specialists and PCPs for many survivors,43 evidence bearing on the optimal timing for transitioning some or all aspects of follow-up care to PCPs is lacking. Research is needed to evaluate risk stratification models that have been proposed as one means of tailoring the timing of transitions to primary care.46 More broadly, there is a compelling need to address the identified lack of research addressing the adoption of survivorship care models within community-based primary care practices.47 Evaluation of different survivorship care models in real-world settings will likely require moving beyond traditional randomized controlled trials to conduct research informed by implementation science methodology.48 For example, future studies may involve randomization at the practice level to examine the effectiveness of a care model on relevant clinical outcomes, while simultaneously observing and gathering information on process of implementing the model in each practice.49 Use of this and other forms of hybrid effectiveness-implementation research designs can generate findings with the potential of speeding the translation of effective care models into routine clinical practice.49

In conclusion, this systematic review found limited evidence that SCPs improve health outcomes or health care delivery. However, it is premature to conclude that SCPs are not beneficial, given weaknesses in the evidence base that include a limited number of studies, heterogeneity in the content and delivery of SCPs, and unrealistic expectations that one-time delivery of an SCP would improve patient outcomes weeks or months later. Recommendations going forward include consideration of ways to improve the impact of SCPs as well as selection of more appropriate proximal outcomes. In addition, research in this area should consider whether it is time to move beyond studies that look at SCPs in isolation and instead conduct research in which SCPs are embedded in studies evaluating the effectiveness of different survivorship care models in improving health outcomes and health care use for cancer survivors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Leslie Robison and Flora van Leeuwen for assistance with the initial selection of relevant publications and Gina Tesauro for help with database creation.

Appendix

PICO Framework

Question:

What impact does provision of survivorship care plans (SCPs) have on health outcomes and health care delivery?

Patients:

Individuals diagnosed with cancer

Intervention:

Survivor or care provider receipt of an SCP

Comparison:

No receipt of an SCP, alternate method(s) of receiving an SCP, or no comparison (nonrandomized studies)

Outcome:

Patient-reported health outcomes (eg, quality of life), health care use, health care costs, health outcomes (eg, quality-adjusted life years), and health care experience (eg, satisfaction with care)

PubMed/MEDLINE Search Strategy

(Cancer OR Cancers OR Neoplasm OR Neoplasms OR Neoplasia OR "Neoplasms"[Mesh])

((“care planning” OR “care plan*”OR “survivorship care plan*” OR “Follow-up care” OR “follow up care” OR (“follow up” AND care) OR (follow-up AND care) OR “continuity of care” OR “continual care” OR “continuous care” OR “longitudinal care” OR "Patient Care Planning"[Mesh] OR "Continuity of Patient Care"[Mesh]) AND (Survivor* OR Survivorship OR "Survivors"[Mesh])

(“Randomized controlled trial” OR “Non-randomized controlled trial” OR “non-randomized controlled trial” OR "Randomized Controlled Trial" [Publication Type] OR "Non-Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic"[Mesh])

(“patient satisfaction” OR “quality of life” OR QOL OR Distress OR Understanding OR “screening compliance” OR Feasibility OR ("care coordination" AND rating*) OR “disease recurrence” OR “serious clinical event*” OR “social support” OR “survival rate” OR "Treatment Outcome"[Mesh] OR "Patient Outcome Assessment"[Mesh] OR "Patient Satisfaction"[Mesh] OR "Quality of Life"[Mesh] OR "Stress, Psychological"[Mesh] OR "Comprehension"[Mesh] OR "Patient Compliance"[Mesh] OR "Feasibility Studies"[Mesh] OR "Recurrence"[Mesh] OR "Social Support"[Mesh] OR "Survival Rate"[Mesh])

1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. P30 CA008748 to C.S.M.).

Presented at the Cancer Survivorship Symposium, Orlando, FL, February 16, 2018.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Systematic Review of the Impact of Cancer Survivorship Care Plans on Health Outcomes and Health Care Delivery

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Paul B. Jacobsen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Carevive

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Carevive (Inst)

Antonio P. DeRosa

No relationship to disclose

Tara O. Henderson

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics

Deborah K. Mayer

Stock or Other Ownership: Carevive

Chaya S. Moskowitz

Consulting or Advisory Role: BioClinica

Electra D. Paskett

Stock or Other Ownership: Pfizer, Pfizer (I), Meridian Bioscience, Meridian Bioscience (I)

Research Funding: Merck Foundation

Julia H. Rowland

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract 10:345-351, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Surgeons Commision on Cancer Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL, American College of Surgeons, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. : American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin 66:43-73, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forsythe LP, Parry C, Alfano CM, et al. : Use of survivorship care plans in the United States: Associations with survivorship care. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:1579-1587, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, et al. : Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin 62:101-117, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birken SA, Mayer DK: Survivorship care planning: Why is it taking so long? J Natl Compr Canc Netw 15:1165-1169, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ: Survivorship care plans: Prevalence and barriers to use. J Cancer Educ 28:290-296, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salz T, McCabe MS, Onstad EE, et al. : Survivorship care plans: Is there buy-in from community oncology providers? Cancer 120:722-730, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools: Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies. Hamilton, ON, Canada, Effective Public Health Practice Project, 1998. www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

- 11.Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org

- 12.Berman AT, DeCesaris CM, Simone CB, II, et al. : Use of survivorship care plans and analysis of patient-reported outcomes in multinational patients with lung cancer. J Oncol Pract 12:e527-e535, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaauwbroek R, Barf HA, Groenier KH, et al. : Family doctor-driven follow-up for adult childhood cancer survivors supported by a web-based survivor care plan. J Cancer Surviv 6:163-171, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blinder VS, Norris VW, Peacock NW, et al. : Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment plan and summary documents in community oncology care: A pilot program. Cancer 119:164-172, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, et al. : An internet tool for creation of cancer survivorship care plans for survivors and health care providers: Design, implementation, use and user satisfaction. J Med Internet Res 11:e39, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, et al. : Utilization of internet-based survivorship care plans by lung cancer survivors. Clin Lung Cancer 10:347-352, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, et al. : High level use and satisfaction with internet-based breast cancer survivorship care plans. Breast J 18:97-99, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jefford M, Lotfi-Jam K, Baravelli C, et al. : Development and pilot testing of a nurse-led posttreatment support package for bowel cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 34:E1-E10, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, et al. : Increasing rates of breast cancer and cardiac surveillance among high-risk survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma following a mailed, one-page survivorship care plan. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56:818-824, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rushton M, Morash R, Larocque G, et al. : Wellness Beyond Cancer Program: Building an effective survivorship program. Curr Oncol 22:e419-e434, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spain PD, Oeffinger KC, Candela J, et al. : Response to a treatment summary and care plan among adult survivors of pediatric and young adult cancer. J Oncol Pract 8:196-202, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szalda D, Schwartz L, Schapira MM, et al. : Internet-based survivorship care plans for adult survivors of childhood cancer: A pilot study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 5:351-354, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boekhout AH, Maunsell E, Pond GR, et al. : A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: Extended results of a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Surviv 9:683-691, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brothers BM, Easley A, Salani R, et al. : Do survivorship care plans impact patients’ evaluations of care? A randomized evaluation with gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol 129:554-558, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyle D, Grunfeld E, Coyle K, et al. : Cost effectiveness of a survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract 10:e86-e92, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emery JD, Jefford M, King M, et al. : ProCare Trial: A phase II randomized controlled trial of shared care for follow-up of men with prostate cancer. BJU Int 119:381-389, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, et al. : Evaluating survivorship care plans: Results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:4755-4762, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, et al. : Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: A comparison of family physician versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol 24:848-855, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grunfeld E, Mant D, Yudkin P, et al. : Routine follow-up of breast cancer in primary care: Randomised trial. BMJ 313:665-669, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hershman DL, Greenlee H, Awad D, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 138:795-806, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudson MM, Leisenring W, Stratton KK, et al. : Increasing cardiomyopathy screening in at-risk adult survivors of pediatric malignancies: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 32:3974-3981, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jefford M, Gough K, Drosdowsky A, et al. : A randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led supportive care package (SurvivorCare) for survivors of colorectal cancer. Oncologist 21:1014-1023, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maly RC, Liang L-J, Liu Y, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of survivorship care plans among low-income, predominantly Latina breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 35:1814-1821, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolaije KA, Ezendam NP, Vos MC, et al. : Impact of an automatically generated cancer survivorship care plan on patient-reported outcomes in routine clinical practice: Longitudinal outcomes of a pragmatic, cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 33:3550-3559, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith KC, Tolbert E, Hannum SM, et al. : Comparing web-based provider-initiated and patient-initiated survivorship care planning for cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. JMIR Cancer 2:e12, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin TA, Moran-Kelly RM, Concert CM, et al. : Effectiveness of individualized survivorship care plans on quality of life of adult female breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports 11:258-309, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brennan ME, Gormally JF, Butow P, et al. : Survivorship care plans in cancer: A systematic review of care plan outcomes. Br J Cancer 111:1899-1908, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klemanski DL, Browning KK, Kue J: Survivorship care plan preferences of cancer survivors and health care providers: A systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv 10:71-86, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer DK: Survivorship care plans: Necessary but not sufficient? Clin J Oncol Nurs 18(s1, Suppl)7-8, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parry C, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, et al. : Can’t see the forest for the care plan: A call to revisit the context of care planning. J Clin Oncol 31:2651-2653, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer DK, Birken SA, Chen RC: Avoiding implementation errors in cancer survivorship care plan effectiveness studies. J Clin Oncol 33:3528-3530, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, et al. : Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: A systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv 6:359-371, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nekhlyudov L, O'Malley DM, Hudson SV: Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: Gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol 18:e30-e38, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Society of Clinical Oncology : Models of long-term follow-up care. https://www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship/survivorship-3

- 45.Halpern MT, Viswanathan M, Evans TS, et al. : Models of cancer survivorship care: Overview and summary of current evidence. J Oncol Pract 11:e19-e27, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, et al. : Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol 40:804-812, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubinstein EB, Miller WL, Hudson SV, et al. : Cancer survivorship care in advanced primary care practices: A qualitative study of challenges and opportunities. JAMA Intern Med 177:1726-1732, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, et al. : An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol 3:32, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. : Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 50:217-226, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]