Abstract

Objective

Systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is characterized with various complications which can cause serious organ damage in the human body. Despite the significant improvements in disease management of the SLE patients, the non-invasive diagnosis is entire missing. In this study, we used urinary peptidomic biomarkers for early diagnosis of disease onset to improve patient risk stratification vital for effective drug treatment.

Methods

Urine samples from patients with SLE, lupus nephritis (LN) and healthy controls (HC) were analyzed using capillary electrophoresis coupled to mass spectrometry (CE-MS) for state-of-art biomarker discovery.

Results

A biomarker panel made up of 65 urinary peptides was developed that accurately discriminate SLE without renal involvement from HC patients. The performance of the SLE-specific panel was validated in a multicentric independent cohort consisting of patients without SLE but with different renal disease and LN. This resulted in area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.80 (p<0.0001, 95%-CI 0.65–0.90) corresponding to a sensitivity and a specificity of 83% and 73%, respectively. Based on the end terminal amino acid sequences of the biomarker peptides, an in silico methodology was used to identify the proteases that were up or down regulated. This identified matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) as being mainly responsible for the peptides fragmentation.

Conclusion

A laboratory-based urine test was successfully established for early diagnosis of SLE patients. Our approach determined the activity of several proteases and provided novel molecular information that could potentially influence treatment efficacy.

Keywords: SLE, urine peptide biomarkers, protease prediction

1 Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by numerous clinical pathologies with an overall incidence up to 1000 cases per 100.000 individuals in the general population [1]. Inflammation often involves a broad range of vital organs and causes serious complications with increased mortality and morbidity [2]. The most common organ manifestation is lupus nephritis (LN), affecting approximately 40% of SLE patients [3–5]. Despite advances in the latest therapies, significant and variable organ involvement from patient-to-patient is evident [6]. These facts indicate a need for improvement of the management of patients diagnosed with SLE, possibly guided by appropriate biomarkers.

Pathogenesis of SLE is associated with multiple complex processes affecting not only the skin, but also musculoskeletal system, kidneys and central nervous system (CNS) [6]. Autoantibody accumulation, increase of abundance of proteins from the complement system and activation of macrophages are some of the disrupted molecular responses that lead to inflammation and aggressive disease progression which is often unresponsive to therapies [7]. These effects together with an increase of cell proliferation, production of numerous extracellular proteins, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, cause destructive changes in the functional mechanisms indicative of the renal tubular damage, vascular injury, tubulointerstitial inflammation, and fibrosis [8, 9]. Although the knowledge about these factors resulted in better medical care of SLE patients during the last decades, the prognosis of disease outcome is still not optimal [10]. Factors impacting the moderate clinical efficiency of intervention may also be the higher toxicity of the current medications utilized in intervention [11]. In spite of the efforts for improved strategies and specific molecular drug targeting for immunopathogenic pathways, the data on targeted therapies for SLE onset activity are generally disappointing [12, 13]. In order to prevent later stage SLE-related complications and comorbidities, identification of novel and more reliable panel of surrogate biomarkers reflecting complex underlying processes could be beneficial for patients in guiding treatment or accessing interventional responses, also avoiding possibly unnecessary high-dose drug treatment during long-term disease course.

Currently, the most common biomarkers for monitoring disease activity and its progression appear of moderate advantage. Standard biomarkers such as anti-double stranded (ds) DNA antibodies and complement levels show association with outcome/prognosis of SLE-associated comorbidities and value in clinical practice. However, a number of studies have demonstrated lower specificity of these laboratory tests i.e serum anti-dsDNA antibodies and suggested moderate value in treatment decision making [14, 15]. In a similar manner, complement 3 (C3) and 4 (C4) measurements provided weak performance for diagnosis of SLE [16, 17]. Therefore, additional non-invasive methods appear urgently required to provide important information about pathogenesis of SLE and improve the management of these patients particularly when the disease is at an early stage.

Urine, specifically urinary peptides for biomarker development, have multiple advantages over current available options, as outlined in detail in several recent publications [18–21]. Among these are the opportunity for multiple and non-invasive sampling, the high stability of the urinary peptide biomarkers. When dealing with a disease that, as described above, has multiple complex processes, a biomarker containing multiple components can better reflect these wide range ranging changes. In addition to these specific advantages there is currently, available over 40000 reference datasets, which can enable efficient in silico assessment, moving towards true “liquid biopsy”, as recently introduced [22]. These advantages also render urinary biomarkers as a promising way for monitoring of disease activity, and drug response.

In the past, we have demonstrated the association of urinary peptides with inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis [23] and also graft-versus-host-disease [24]. A similar study has recently identified biomarkers specific for LN that enabled differentiating of LN from other chronic kidney diseases [25]. Based on these data, we generated the hypothesis that urinary peptides could reflect SLE, and may have value in diagnosis of SLE. To test this hypothesis, we used capillary electrophoresis coupled to mass spectrometry (CE-MS) to evaluate the urinary proteomic profiles of samples collected from patients with SLE and healthy controls (HC), aiming at identifying peptides associated with SLE. Such peptides could subsequently be used as biomarkers to assess the success of intervention, possibly even guiding intervention towards personalized therapy.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample characteristics

In total 173 urine samples were used in this study. Samples collected from SLE patients with (n=34) with no renal involvement, and matched (for age, gender, and eGFR ) HC (n=58) were used for the identification of potential biomarkers and development of a classifier of SLE. In addition, samples from 36 subjects with SLE and impaired renal function (LN) were employed to verify the potential biomarkers advanced for SLE. The participants were selected from prospective, longitudinal and prospective SPARE study (Study of biological Pathways, disease Activity and Response markers in patients with systematic lupus Erythematosus), approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Review Board, from NCT01731054, a prospective non-interventional study evaluating MRI imaging in patients with LN and from Bioreclamation (Baltimore MD).

For subsequent validation, samples from LN patients (n=23) and matched (for age, gender, and eGFR) non-SLE patients with different renal diseases (n=22) were employed. This sub-group of participants was selected from Mosaiques Human Urine Database [26]. The study was conducted according the guidelines of Declaration of Helsinki and consent from all participants was obtained.

2.2 Sample preparation

Immediately before preparation, the samples were thawed, a 0.7 mL aliquots were removed and diluted with 0.7 mL 2 M urea, 10 mM NH4OH containing 0.02% SDS. Removal of the high molecular weight polypeptides were performed by filtering using Centrisart ultracentrifugation filter devices (20 kDa molecular weight cut-off; Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany) at 3,000 × g until 1.1 mL of filtrate was obtained. Subsequently, filtrates were desalted using PD-10 column (GE Healthcare, Sweden) equilibrated in 0.01% NH4OH in HPLC-grade water. Finally, samples were lyophilized and stored at 4°C.

2.3 CE-MS analysis

CE-MS analysis was performed as described [27] using a P/ACE MDQ capillary electrophoresis system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, USA) on-line coupled to a MicroTOF MS (Bruker). The electron spray ionization tool (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was grounded, and the ion spray interface potential was set –4.5 kV. Laboratory measurements were automatically controlled by the CE via contact-close-relays. Spectra were accumulated every 3 s, over a range of mass to charge ratio (m/z) 350 to 3000 [28–30]. Shortly before the CE-MS analysis, lyophilisates were resuspended in HPLC-grade water to a final protein concentration of 0.8 μg/μL, based on the BCA assay (Interchim, Montlucon, France).

2.4 Data processing and cluster analysis

Actual molecular mass and signal intensities were calculated using MosaiquesVisu software [31]. Migration time and ion signal intensity (amplitude) were normalized using “internal polypeptide standards”, as described [32]. The resulting peak list characterizes each polypeptide by its molecular mass [Da], normalized migration time [min] and signal intensity. All detected polypeptides were deposited, matched, and annotated in a Microsoft SQL database. During initial clustering, polypeptides within different samples were considered identical, if mass deviation was <50 ppm for small or 75 ppm for larger peptides. Due to analyte diffusion effects, CE peak widths increase with CE migration time. In the data clustering process, this effect was considered by linearly increasing cluster widths over the entire electropherogram (19 min to 45 min) from 2–5%.

2.5. Sequencing

Determination of the primary structure of the urinary peptides was performed using CE-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS, as described in detail previously [33]. In short, samples if separated by LC, were first loaded onto a Dionex C18 nano trap column (100 μm × 2 cm 5 μm) at a flowrate of 5 μl/min and subsequently washed off into an Acclaim PepMap C18 nano column (75 μm × 15 cm, 2 μm 100 μ) at a flowrate of 0.3 μm/min using a Ultimate 3000 RSLC autosampler and pump system (Dionex, Camberley UK). The samples were eluted with a gradient of solvent A:98% 0.1% formic acid, 2% acetonitrile verses solvent B: 80% acetonitrile, 20% 0.1% formic acid starting at 1% B for 5 min rising to 20% B after 90 min and finally to 40%B after 120 min. Once loaded onto the trap column the samples were then washed off into an. The trap and nano flow column were maintained at 35 °C in a column oven in the Ultimate 3000 RSLC [34]. Alternatively, samples were injected and separated using a P/ACE MDQ capillary electrophoresis system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, USA) as described above for CE-MS [27].

The eluents from the CE was directed to an were directed to a hybrid mass spectrometer LTQ Velos dual cell linear trap with Orbitrap FTMS analyzer (Thermo Finnigan, Bremen, Germany) via Agilent ESI sprayer as described above. The eluent from LC was directed to a Proxeon nano spray ESI source (Thermo Fisher Hemel UK) operating in positive ion mode then into Orbitrap Velos FTMS (Thermo Finnigan, Bremen, Germany). The ionization voltage was 2.5 kV and the capillary temperature was 200 °C. The mass spectrometer was operated in MS/MS mode scanning from 380 to 2000 amu. The fragmentation was performed with higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) method at 35% collision energy. The ions were selected for MS2 using a data dependant method with a repeat count of 1 and repeat and exclusion time of 15 s. Precursor ions with a charge state of 1 were rejected. The resolution of ions in MS1 was 60,000 and 7,500 for HCD MS2.

Data files from experiments performed on the HCD-enabled LTQ were searched against the UniProt human non-redundant database using Thermo Proteome Discoverer version 1.2, without any proteolytic enzyme specified. No fixed modification was selected, oxidation of methionine and hydroxylation of proline were set as variable modifications. Mass error window of 10 ppm and 0.05 Da were allowed for MS and MS/MS, respectively [34].

For further validation of obtained peptide identifications, CE-MS/MS analysis was performed on selected peaks, In addition, the strict correlation between peptide charge at the working pH of 2 and CE-migration time was utilized to minimize false-positive identification rates [35]: Estimated CE-migration time of the sequence candidate based on its peptide sequence (number of basic amino acids) was compared to the experimental migration time. CE-migration time deviations below ±2 min corresponding to the CE-MS measurement were accepted.

2.6 Statistical analysis

For definition of the biomarkers, R-based programming language was used. Unadjusted p-values were calculated applying natural logarithm for transformation of the CE intensities spectra and Gaussian approximation to test distribution. Their p-values were calculated using Wicoxcon Rank Sum test followed by multiple testing using the method described by Benjamini and Hochberg [36]. Generation of the SLE-specific classifier was done using support vector machine (SVM)-based Mosa Cluster software [37]. Classification scores provided by this software were expressed by numerical values quantifying the Euclidean distance of the data point to the maximal margin of the separation hyperplane among cases and controls in multidimensional space, defined by the classification score generated in the training cohort. All further statistical calculations were performed using MedCalc (version 12.7.5.0, MedCalc Software, Mariaakerke, Belgium; www.medcalc.be).

2.7 In silico protease prediction

Prediction of the potential proteases responsible for the generation of naturally occurring peptides associated with SLE was performed using Proteasix bioinformatics software [38]. Briefly, N and C terminal cleavage sites of the SLE specific 47 polypeptides were used to calculate in silico the probability of certain protease involved in proteolytic processing and breakdown of their paternal proteins. The proteases which were previously observed by Proteasix were considered as a high confidence. If not then the specificity of the prediction was evaluated by randomly mapping more than 6000 octapeptides sequences using MEPROS database list which contain the information about the frequency of each amino acid at every position in the experimentally confirmed cleavage site of the given protease. Based on mean intensities of the detected peptide markers, activity of the proteases was calculated for each patient and compared between patients groups. Proteases with ≥ 2 cleavage site association and predicted as a high confidence were further investigated [39]. Mann-Whitney test with adjusted p-values <0.05 was applied to identify the proteases with a significant proteolytic activity responsible for the observed protein/peptide fragmentation.

3. Results

3.1 CE-MS analysis of the urine polypeptides

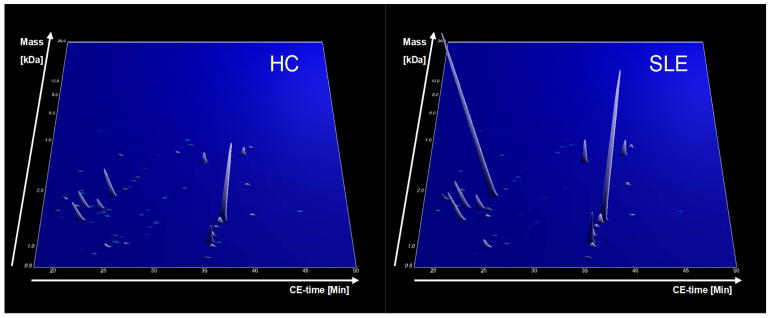

All urine samples were analyzed as described [27, 40]. After the laboratory measurement, the mass and retention time of each peptide marker detected was calibrated and harmonized with the human urinary proteome database [26, 27, 40] to allow consistent data evaluation and comparison with previous results. Schematic representation of the study design is given in Figure 1. All recorded intensities represented in a form of peaks with their appropriate mass and retention time of each patients group (HC and SLE) are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Schematic study design depicting all patients used for generation of the 65 diagnostic biomarker panel without renal involvement and its validation in independent patient cohort.

Figure 2.

Group specific contour plots of SLE and HC cohort (upper panel). Each consisting of digitally compiled data sets of urine samples in a 3D depiction. Molecular mass of the analyzed polypeptides (kDa) in logarithmic scale is plotted against the CE migration time (min) with MS signal intensity in z-axis.

3.2 Biomarker identification

In order to detect the SLE-specific peptides, the peptide marker intensities obtained from 34 samples of patients with SLE were compared to the intensities of 58 HC (Figure 1). Demographic characteristics of the patient groups are shown in Table 1. Only peptides with the frequency of occurrence >50% in at least one of the groups were investigated. This resulted in the identification of just 95 peptides that showed significantly different intensities between the compared patient groups (adj. p<0.05). Due to insufficiency of sample collection and lack of clinical data from the same group of patients used for identification of the potential biomarkers, we investigated the intensities of the 95 potential biomarkers in an additional 36 samples from SLE patients with renal involvement (LN). By doing so, and performing additional statistical analysis, we found out that 65 of the biomarker candidates were SLE specific and remaining 30 showed weak correlation in regard to the disease and therefore were discarded. The verified 65 biomarker candidates were retained as likely SLE-specific.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients from discovery cohort

| HC (58) | SLE (34) | LN (36) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN vs nonrenal SLE | LN vs HC | nonrenal SLE vs HC | ||||

| Sex | F/M: 55/3 (94% F) | F/M: 32/2 (94% F) | F/M: 34/2 (94% F) | |||

| Age | 37.74±11.46 | 40.68±10.24 | 41.44±11.61 | |||

| Race* | 33C, 21B, O4 | 23C, 9B, 1A, 1O, 1U | 17C, 14B, 2A, 3O | |||

| uPCR (mg/mg) | 0.04±0.02 | 0.04±0.05 | 2.88±2.29 | < 0.000001 | < 0.000001 | |

| sCre (mg/dl) | 0.82±0.21 | 0.78±0.16 | 1.52±1.25 | 0.001418 | 0.010633 | |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 91.37±20.05 | 92.28±23.43 | 61.8±37 | 0.000182 | 0.001869 | |

| SLEDAI Global Score** | NA | 2.97±3.05 | 7.61±3.99 | 0.000052 | ||

| rSLEDAI** | NA | 0 | 4.89±2.59 | 0.077739 | ||

| PGA** | NA | 1.84±0.35 | 2.08±0.41 | |||

Abbreviations: uPCA-urine protein to creatinine ratio; sCre-serum creatinine ratio; eGFR –estimated glomerular filtration rate; SLEDAI-systemic lupus erythemathosus disease activity index; rSLEDAI-renal systemic lupus erythemathosus disease activity index ; PGA-physician’s global assessment;

C - Caucasian, B - Black, A - Asian, O - Other, U – unknown;

Values only for the 34 nonrenal SLE and 18 LN patients from the SPARE cohort due to limited clinical data for the 18 LN patients from NCT01731054.

3.3 Peptide sequence information and generation of the SLE diagnostic panel

Tandem mass spectrometry as methodology is used for breaking down precursor ions into smaller fragments in order to reveal chemical structures. This approach enabled sequence information for 47 out of the 65 biomarkers candidates listed in Table 2. In total, 37 of the 47 sequenced peptides originated from different collagen fragments. Almost all (only one exception) were decreased in patients with SLE. In addition, 5 uromodulin fragments were defined and they were increased in SLE patients compared to HC. Two different fragments of fibrinogen alpha were also defined, while one fragment was increased the other one was decreased in SLE patients. The distribution of all 65 biomarker candidates in HC and SLE patients is shown in Figure 3.

Table 2.

List of sequenced peptide markers specific for SLE.

| Mass [Da] | CE-Time [Min] | mean Amplitude SLE | mean Ampli-tude HC | adjusted p-value (BH) | Fold change SLE/HC | Sequence | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 892.27 | 35.19 | 1032.98 | 484.49 | 3.71E-03 | 2.13 | GDGDGDGDAD | ATPase WRNIP1 |

| 840.4 | 25.36 | 11.27 | 45.29 | 2.10E-02 | 0.25 | DGKTGPpGP | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1050.48 | 26.93 | 551.61 | 828.04 | 3.21E-02 | 0.67 | DGRpGPpGPpG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1070.5 | 36.38 | 54.17 | 198.98 | 4.37E-02 | 0.27 | GPpGPpGpPGPP | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1080.5 | 25.69 | 50.91 | 142.23 | 4.18E-03 | 0.36 | DRGEpGPpGPA | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1137.51 | 26.5 | 27.72 | 112.41 | 2.01E-02 | 0.25 | GDRGEpGPpGPA | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1154.51 | 25.72 | 148.69 | 472.3 | 4.64E-02 | 0.31 | PpGEAGKpGEQG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1171.51 | 29.04 | 31.24 | 67.77 | 2.10E-02 | 0.46 | DGAKGDAGApGApG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1286.54 | 29.33 | 40.67 | 114.03 | 3.43E-02 | 0.36 | DGQpGAKGEpGDAG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1444.67 | 20.06 | 15.95 | 75.65 | 1.13E-02 | 0.21 | SpGRDGSpGAKGDRG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1491.73 | 39.89 | 453.22 | 839.27 | 2.39E-02 | 0.54 | VGpPGPPGpPGPPGPPS | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1997.91 | 25.16 | 22.92 | 130.76 | 3.00E-03 | 0.18 | NSGEPGApGSKGDTGAKGEpGP | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 2096.91 | 32.82 | 47.32 | 271.66 | 3.00E-03 | 0.17 | GApGNDGAKGDAGApGApGSQGApG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 2128.98 | 26.92 | 38.42 | 91.63 | 2.72E-02 | 0.42 | DGKTGpPGPAGQDGRpGPpGPpG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 2308.01 | 27.33 | 101.23 | 241.66 | 1.86E-02 | 0.42 | ADGQpGAKGEpGDAGAKGDAGPpGpA | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 2423.09 | 27.7 | 281.13 | 467.7 | 2.10E-02 | 0.60 | LDGAKGDAGPAGpKGEpGSpGENGApG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 2639.29 | 21.44 | 197.06 | 381.82 | 2.01E-02 | 0.52 | KEGGKGPRGETGPAGRpGEVGPpGPpGP | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 3264.57 | 25.7 | 646.7 | 1020.58 | 4.61E-02 | 0.63 | AAGEpGKAGERGVpGPpGAVGPAGKDGEAGAQGPPGP | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 3416.59 | 31.96 | 150 | 811.86 | 2.01E-02 | 0.18 | GPpGADGQPGAKGEpGDAGAKGDAGPPGpAGPAGPPGpIG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1341.57 | 29.94 | 26.65 | 154.08 | 2.25E-03 | 0.17 | GADGQPGAKGEpGDA | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1359.61 | 23.18 | 44.69 | 138.64 | 4.78E-02 | 0.32 | GPpGPSGNAGPpGpPG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1526.69 | 23.89 | 61.17 | 127.66 | 3.43E-02 | 0.48 | DGQPGAKGEpGDAGAKG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1586.73 | 29.02 | 46.98 | 108.81 | 2.35E-02 | 0.43 | RGEQGpAGSpGFqGLP | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1636.74 | 22.52 | 15102.65 | 9684.36 | 2.35E-02 | 1.56 | GSpGSpGPDGKTGPpGPAG | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1874.83 | 30.89 | 30.81 | 97.62 | 2.10E-02 | 0.32 | GPSGpQGpGGpPGPKGNSGEP | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain |

| 1066.48 | 25.98 | 33.71 | 256.07 | 2.90E-02 | 0.13 | GEDGRpGPpGP | Collagen alpha-1(II) chain |

| 1848.8 | 30.73 | 42.85 | 92.45 | 2.35E-02 | 0.46 | QGLpGpPGPSGDqGASGpAGP | Collagen alpha-1(II) chain |

| 3266.48 | 29.96 | 25.4 | 67.14 | 2.76E-02 | 0.38 | PGLGGNFAAqmAGGFDEKAGGAQLGVMqGPMGPM | Collagen alpha-1(II) chain |

| 1623.73 | 24.09 | 7923.12 | 5591.69 | 1.52E-02 | 1.42 | DGApGKNGERGGpGGpGP | Collagen alpha-1(III) chain |

| 2062.93 | 26.46 | 329.2 | 737.51 | 2.81E-03 | 0.45 | DAGAPGApGGKGDAGApGERGpPG | Collagen alpha-1(III) chain |

| 980.5 | 22.53 | 19.24 | 56.91 | 4.44E-03 | 0.34 | PGKDGPRGPT | Collagen alpha-1(III) chain |

| 1357.57 | 29.93 | 62.09 | 165.66 | 4.64E-02 | 0.37 | SpGSPGYQGpPGEP | Collagen alpha-1(III) chain |

| 1837.79 | 30.66 | 46.52 | 144.09 | 3.14E-02 | 0.32 | pGPpGTSGHpGSPGSPGYQG | Collagen alpha-1(III) chain |

| 1657.74 | 23.04 | 17.14 | 155.84 | 7.50E-03 | 0.11 | PGVpGpKGDpGFQGmPG | Collagen alpha-1(IV) chain |

| 2739.23 | 28.46 | 43.82 | 112.75 | 1.86E-02 | 0.39 | EqGpPGPTGPQGPIGQPGpSGADGEPGpR | Collagen alpha-1(V) chain |

| 935.45 | 23.82 | 43.3 | 159.86 | 2.56E-03 | 0.27 | GRpGPpGPpG | Collagen alpha-1(XXVI) chain |

| 1576.75 | 19.51 | 394.31 | 619.15 | 4.16E-02 | 0.64 | EDGHpGKPGRpGERG | Collagen alpha-2(I) chain |

| 3801.79 | 33.48 | 164.86 | 339.76 | 2.40E-02 | 0.49 | DQGPVGRTGEVGAVGPpGFAGEKGpSGEAGTAGPPGTpGPQG | Collagen alpha-2(I) chain |

| 1669.69 | 21.45 | 228.69 | 733.4 | 1.50E-02 | 0.31 | DEAGSEADHEGTHSTK | Fibrinogen alpha chain |

| 1825.79 | 20.13 | 2582.59 | 1472 | 1.13E-02 | 1.75 | DEAGSEADHEGTHSTKR | Fibrinogen alpha chain |

| 1409.58 | 22.11 | 15894.85 | 10788.15 | 1.63E-02 | 1.47 | SGQEGAGDSPGSQFS | Forkhead box protein O1 |

| 2187.96 | 39.54 | 1832.87 | 1185.26 | 4.35E-02 | 1.55 | HEGEPTTFQSWPSSKDTSPA | Mucin-12 |

| 1911.05 | 25.23 | 60713.19 | 14925.34 | 1.51E-06 | 4.07 | SGSVIDQSRVLNLGPITR | Uromodulin |

| 2039.13 | 21.83 | 955.5 | 289.26 | 3.00E-03 | 3.30 | SGSVIDQSRVLNLGPITRK | Uromodulin |

| 1013.37 | 25.06 | 5375.8 | 2516.87 | 4.49E-02 | 2.14 | IQDYDECE | Uromodulin |

| 1467.81 | 24.78 | 1252.24 | 249.04 | 2.38E-05 | 5.03 | DQSRVLNLGPITR | Uromodulin |

| 1580.9 | 24.89 | 1688.38 | 355.52 | 6.40E-05 | 4.75 | IDQSRVLNLGPITR | Uromodulin |

Given are mass and CE time of each peptide marker, mean amplitude of the peptide markers in SLE and HC in development cohort, P-value according to the Benjamini and Hochberg [36] for the comparison of cases and controls (SLE vs HC), fold change calculated as mean amplitude of SLE towards HC, amino acid sequence information and precursor protein name.

Figure 3.

Group specific contour plots of the defined and validated 65 specific peptides for SLE. Showed are compiled data sets of urine samples in a 3D depiction. Molecular mass of the analyzed polypeptides (kDa) in logarithmic scale is plotted against the CE migration time (min) with MS signal intensity in z-axis.

Generation of the SLE-diagnostic panel with 65 peptide markers was carried out by using machine learning algorithms (SVM modelling) commonly employed for classification analysis. This is especially important for categorization of patients into those with or without presence of disease. Therefore, the peptide marker panel developed herein was applied to the discovery cohort (n=92) and achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) of 0.99 in discrimination of SLE from HC. To assess the value and validity of this panel, its performance was assessed in the independent multicentric validation cohort (n=45) including LN and non-SLE patients. Baseline characteristics of the validation set are shown in table 3. This analysis resulted with an AUC of 0.80 (p<0.0001, 95%-CI 0.65–0.90) corresponding to a sensitivity and a specificity of 83% and 73%, respectively (Figure 4). These findings, clearly demonstrated that the urinary peptides are associated with SLE, and support the validity of the approach throughout the classifier development.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the validation set

| Variable | Non-SLE with other CKD (22) | LN (23) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F/M: 14/8 (51% F) | F/M: 18/5 (78% F) | p=0.2898 |

| Age | 42.28.±7.13 | 37.34±13.25 | p=0.1299 |

| eGFR | 94.14±18.77 | 94.47±19.70 | p=0.9534 |

CKD-Chronic kidney disease

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the diagnostic peptide biomarker panel used to discriminate patients having SLE from those without in a) the development cohort consisting of 34 SLE and 58 HC patients after total cross-validation and in b) the validation cohort of 23 LN and 22 non-SLE patients with multiple renal diseases.

3.4 In silico protease identification

Based on the mass and retention time of the naturally occurring peptides detected by the CE-MS technology (47 urinary biomarkers), we next tried to identify in silico the proteases likely responsible for the generation of the SLE-specific urinary peptide markers. Mean intensities of the 47 biomarkers with available amino acid sequence information in both patient groups revealed 8 proteases with increased cleavage activity as shown in Table 4. Majority of the proteases were identified as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), with the most prominent activity of MMP 9. We also found increased activity of serine protease hepsin and decreased activity of kallikrein-2.

Table 4.

Shown are proteases involved in fragmentation of the 47 biomarkers with their number of N or C termini cleavage sites characteristic for each protease; estimated fold change difference based on peptide mean intensities in SLE vs HC patients groups and adjusted p-value calculated by Mann Whitney test.

| Proteases | Number of cleavage sites | Fold change (SLE/HC) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP 3 | 3 | 1.36 | p=0.0159 |

| MMP 8 | 5 | 1.50 | p=0.0057 |

| MMP 9 | 8 | 3.58 | p<0.0001 |

| MMP 12 | 4 | 1.98 | p=0.0001 |

| MMP 13 | 5 | 1.60 | p=0.0006 |

| MMP 14 | 2 | 1.68 | p=0.0011 |

| KLK2 | 3 | 0.64 | p=0.0510 |

| HPN | 2 | 1.33 | p=0.0043 |

MMP-Matrix metalloproteinase; KLK-Kallikrein; HPN-Hepsin

4. Discussion

The course of SLE is manifested with variety and complex molecular features that make management of the disease challenging [41]. Although the most relevant and accurate clinical procedures in assessing SLE complications require regular physical examination and laboratory analysis, SLE is characterized as a serious and common disease with poor long-term prognosis. In this study, we set out to identify urinary biomarkers associated with SLE, that may be of value in disease management. We first developed a SLE-specific panel of 65 peptides that showed highly significant association with SLE in an independent and multicentric validation. Of the 65 peptides making up the SLE panel we identified the amino acid sequence of 47 of them. Based on these data, urinary peptides, specifically the panel presented here, has the potential to improve early diagnosis in clinical settings of SLE, and may provide further insights into the pathophysiological processes implicated in SLE.

Current laboratory diagnostic tests based on the serological determination of anti-double stranded DNA antibodies as well as complement levels widely used for identification of SLE appeared to be insufficient [14, 15, 17]. In particular, sensitivity and specificity measurements of these biomarkers among all SLE patients were ranging from 53–100% and 50–71% respectively, depending on different studies and tests used for monitoring of SLE disease activity. It is essential to note that overall performance of the current molecular signatures is highly variable and of moderate accuracy, also demonstrated by the positive predictive value below 38% [14]. We therefore decided to perform a urinary proteome analysis of clinically well-defined SLE and LN patients collected from prospective, longitudinal, observational and non-interventional study and NCT01731054. The panel developed herein yielded good accuracy when applied to an independent set of LN and non-SLE patients with various renal complications.

Using tandem mass spectrometry, 72% of the potential urinary biomarkers for SLE could be identified. It is likely that the peptides that remained unidentified harbour post-translational modifications, which, via their impact on the molecular mass, interfere with sequence assignment in MS/MS analysis [34]. The majority of the small naturally occurring peptides that were identified originate from different forms of collagen. We found 23 fragments of collagen alpha (I) chain, 3 of collagen alpha (II) chain, 4 of collagen alpha (III) chain, 2 of collagen alpha (III) chain. This is not too surprising due to several reasons. First, collagen fragments are the most abundant peptides in urine [21]. Second, collagen, as an abundant protein in the extracellular matrix, is a major target of proteolysis in inflamed organs [42]. [42]. In addition, significant changes in specific fibrinogen alpha-derived peptides were observed, one down-regulated and one up-regulated in SLE compared to HC. Further, 5 uromodulin fragments were found to be significantly changed, all of them upregulated.

Although the most frequent proteins identified in our study were collagens, little is known about the mechanism and breakdown of these polypeptides. As urinary peptides are analyzed intact, that is they have not been subject to enzymatic treatment with trypsin, further informa-tion on the production of the amino acid sequences can be obtained by analysis of their end terminal amino acids. By matching the cleavage site of the identified peptides with proteases known to produce these end terminal sequences we can identify increased and deceased pro-tease activity. This was carried out using an open source software package Proteasix [38]. We performed the in silico prediction of the protease activity and identified the enzymes poten-tially responsible for the peptide fragmentations. Our analysis predicted significant increased activity of 8 proteases in SLE patients. Among them were matrix metalloproteinase MMP -3,-8,-9,-12,-13 and 14 which were previously demonstrated to be involved in extra cellular matrix (ECM) proteolysis [43]. A recent study confirmed the prominent activity of MMP 9 in SLE pa-tients compared to healthy controls which may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease [44]. In contrast to our prediction, normal levels of MMP 3 have been reported in patients with SLE, while significantly increased levels were noted during treatment with corticosteroids [45]. MMP 8 and MMP 13 collagenases were reported to have an ability to cleave fibrillar collagen proteins [43]. However, the complexity of MMPs role and their localization has not been speci-fied, although the majority of the identified proteases in this study were expressed in a variety of renal compartments. So far, there has been no evidence of their implication in SLE and this requires further investigations.

The current work has several potential limitations. First of all, the study was performed in a relatively small sample size. In order to evaluate in-depth the performance of the classifier, pro-teomic analysis in larger patient groups is needed. Secondly, although in our study design we have used an external validation cohort, which consists of patients with renal involvement, an appropriate cohort of SLE patients without renal impairment and healthy controls is necessary to further assess the value of the biomarkers. Thirdly, relevant clinical data, i.e complement C3 and C4 measurements, are not available for all patients and are entirely missing for the healthy individuals. Such data would be required for comparative analysis with the urinary proteome measurements with the current clinical parameters, to properly assess a possible significant advantage or added benefit. However, the data available from this proof-of-concept study clearly demonstrate a highly significant association of specific urinary peptides with SLE and certainly warrant further (prospective) validation studies. Such studies can address the ques-tion of the specific value of urinary peptide biomarkers and classifiers in the context of SLE pa-tient management.

Collectively, our data demonstrated the utility of multi-marker panel approach in discrimination of SLE patients from healthy individuals and further support the high-priority need for such uri-nary biomarkers to be investigated for drug development and monitoring of treatment re-sponse and ultimately improving personalized medicine.

Acknowledgments

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort was funded by NIH AR 43727.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:

HM is founder and co-owner of Mosaiques Diagnostics, who developed CE-MS technology.

MP,JS are employee of Mosaiques Diagnostics.

References

- 1.Chakravarty EF, Bush TM, Manzi S, Clarke AE, Ward MM. Prevalence of adult systemic lupus erythematosus in California and Pennsylvania in 2000: estimates obtained using hospitalization data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2092–2094. doi: 10.1002/art.22641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kammoun K, Jarraya F, Bouhamed L, Kharrat M, Makni S, Hmida MB, Makni H, Kaddour N, Boudawara T, Bahloul Z, Hachicha J. Poor prognostic factors of lupus nephritis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2011;22:727–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MH, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, Pillemer SR, Reveille JD, Stone JH. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Jordan JM, Katz JN, Kremers HM, Wolfe F. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward MM. Prevalence of physician-diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt ) 2004;13:713–718. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez R, Davidson JE, Beeby MD, Egger PJ, Isenberg DA. Lupus disease activity and the risk of subsequent organ damage and mortality in a large lupus cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:491–498. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menke J, Amann K, Cavagna L, Blettner M, Weinmann A, Schwarting A, Kelley VR. Colony-stimulating factor-1: a potential biomarker for lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:379–389. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Novoa JM, Rodriguez-Pena AB, Ortiz A, Martinez-Salgado C, Lopez Hernandez FJ. Etiopathology of chronic tubular, glomerular and renovascular nephropathies: clinical implications. J Transl Med. 2011;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, Balow JE, Bruijn JA, Cook T, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Ginzler EM, Hebert L, Hill G, Hill P, Jennette JC, Kong NC, Lesavre P, Lockshin M, Looi LM, Makino H, Moura LA, Nagata M. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:241–250. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000108969.21691.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam GK, Petri M. Assessment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S120–S132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lander SA, Wallace DJ, Weisman MH. Celecoxib for systemic lupus erythematosus: case series and literature review of the use of NSAIDs in SLE. Lupus. 2002;11:340–347. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu204oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birmingham DJ, Rovin BH, Shidham G, Bissell M, Nagaraja HN, Hebert LA. Relationship between albuminuria and total proteinuria in systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1028–1033. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04761107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rovin BH, Song H, Birmingham DJ, Hebert LA, Yu CY, Nagaraja HN. Urine chemokines as biomarkers of human systemic lupus erythematosus activity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:467–473. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moroni G, Radice A, Giammarresi G, Quaglini S, Gallelli B, Leoni A, Li VM, Messa P, Sinico RA. Are laboratory tests useful for monitoring the activity of lupus nephritis? A 6-year prospective study in a cohort of 228 patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:234–237. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oelzner P, Deliyska B, Funfstuck R, Hein G, Herrmann D, Stein G. Anti-C1q antibodies and antiendothelial cell antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus - relationship with disease activity and renal involvement. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0724-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esdaile JM, Joseph L, Abrahamowicz M, Li Y, Danoff D, Clarke AE. Routine immunologic tests in systemic lupus erythematosus: is there a need for more studies? J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1891–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Joseph L, MacKenzie T, Li Y, Danoff D. Laboratory tests as predictors of disease exacerbations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Why some tests fail. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:370–378. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mischak H, Coon JJ, Novak J, Weissinger EM, Schanstra JP, Dominiczak AF. Capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry as a powerful tool in biomarker discovery and clinical diagnosis: An update of recent developments. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2009;28:703–724. doi: 10.1002/mas.20205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stalmach A, Albalat A, Mullen W, Mischak H. Recent advances in capillary electrophoresis coupled to mass spectrometry for clinical proteomic applications. Electrophoresis. 2013;34:1452–1464. doi: 10.1002/elps.201200708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filip S, Zoidakis J, Vlahou A, Mischak H. Advances in urinary proteome analysis and applications in systems biology. Bioanalysis. 2014;6:2549–2569. doi: 10.4155/bio.14.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mischak H, Kolch W, Aivalotis M, Bouyssie D, Court M, Dihazi H, Dihazi GH, Franke J, Garin J, Gonzales de Peredo A, Iphöfer A, Jansch L, Lacroix C, Makridakis M, Masselon C, Metzger J, Monsarrat B, Mrug M, Norling M, Novak J, Pich A, Pitt A, Bongcam-Rudloff E, Siwy J, Suzuki H, Thongboonkerd V, Wang L, Zoidakis J, Zürbig P, Schanstra J, Vlahou A. Comprehensive human urine standards for comparability and standardization in clinical proteome analysis. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2010;4:464–478. doi: 10.1002/prca.200900189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mischak H. Pro: Urine proteomics as a liquid kidney biopsy: no more kidney punctures! Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:532–537. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stalmach A, Johnsson H, McInnes IB, Husi H, Klein J, Dakna M, Mullen W, Mischak H, Porter D. Identification of urinary Peptide biomarkers associated with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissinger EM, Metzger J, Dobbelstein C, Wolff D, Schleuning M, Kuzmina Z, Greinix H, Dickinson AM, Mullen W, Kreipe H, Hamwi I, Morgan M, Krons A, Tchebotarenko I, Ihlenburg-Schwarz D, Dammann E, Collin M, Ehrlich S, Diedrich H, Stadler M, Eder M, Holler E, Mischak H, Krauter J, Ganser A. Proteomic peptide profiling for preemptive diagnosis of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2014;28:842–852. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siwy J, Zürbig P, Argiles A, Beige J, Haubitz M, Jankowski J, Julian BA, Linde PG, Marx D, Mischak H, Mullen W, Novak J, Ortiz A, Persson F, Pontillo C, Rossing P, Rupprecht H, Schanstra JP, Vlahou A, Vanholder R. Non-invasive diagnosis of chronic kidney diseases using urinary proteome analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw337. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siwy J, Mullen W, Golovko I, Franke J, Zurbig P. Human urinary peptide database for multiple disease biomarker discovery. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2011;5:367–374. doi: 10.1002/prca.201000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coon JJ, Zürbig P, Dakna M, Dominiczak AF, Decramer S, Fliser D, Frommberger M, Golovko I, Good DM, Herget-Rosenthal S, Jankowski J, Julian BA, Kellmann M, Kolch W, Massy Z, Novak J, Rossing K, Schanstra JP, Schiffer E, Theodorescu D, Vanholder R, Weissinger EM, Mischak H, Schmitt-Kopplin P. CE-MS analysis of the human urinary proteome for biomarker discovery and disease diagnostics. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2008;2:964–973. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolch W, Neususs C, Pelzing M, Mischak H. Capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry as a powerful tool in clinical diagnosis and biomarker discovery. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2005;24:959–977. doi: 10.1002/mas.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mischak H, Julian BA, Novak J. High-resolution proteome/peptidome analysis of peptides and low-molecular-weight proteins in urine. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:792–804. doi: 10.1002/prca.200700043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theodorescu D, Fliser D, Wittke S, Mischak H, Krebs R, Walden M, Ross M, Eltze E, Bettendorf O, Wulfing C, Semjonow A. Pilot study of capillary electrophoresis coupled to mass spectrometry as a tool to define potential prostate cancer biomarkers in urine. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2797–2808. doi: 10.1002/elps.200400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theodorescu D, Wittke S, Ross MM, Walden M, Conaway M, Just I, Mischak H, Frierson HF. Discovery and validation of new protein biomarkers for urothelial cancer: a prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:230–240. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70584-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jantos-Siwy J, Schiffer E, Brand K, Schumann G, Rossing K, Delles C, Mischak H, Metzger J. Quantitative Urinary Proteome Analysis for Biomarker Evaluation in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:268–281. doi: 10.1021/pr800401m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein J, Papadopoulos T, Mischak H, Mullen W. Comparison of CE-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS sequencing demonstrates significant complementarity in natural peptide identification in human urine. Electrophoresis. 2014;35:1060–1064. doi: 10.1002/elps.201300327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pejchinovski M, Klein J, Ramirez-Torres A, Bitsika V, Mermelekas G, Vlahou A, Mullen W, Mischak H, Jankowski V. Comparison of higher energy collisional dissociation and collision-induced dissociation MS/MS sequencing methods for identification of naturally occurring peptides in human urine. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2015;9:531–542. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zürbig P, Renfrow MB, Schiffer E, Novak J, Walden M, Wittke S, Just I, Pelzing M, Neususs C, Theodorescu D, Root C, Ross M, Mischak H. Biomarker discovery by CE-MS enables sequence analysis via MS/MS with platform-independent separation. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2111–2125. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc B (Methodological) 1995;57:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Decramer S, Wittke S, Mischak H, Zürbig P, Walden M, Bouissou F, Bascands JL, Schanstra JP. Predicting the clinical outcome of congenital unilateral ureteropelvic junction obstruction in newborn by urinary proteome analysis. Nat Med. 2006;12:398–400. doi: 10.1038/nm1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein J, Eales J, Zürbig P, Vlahou A, Mischak H, Stevens R. Proteasix: A tool for automated and large-scale prediction of proteases involved in naturally-occurring peptide generation. Proteomics. 2013;13:1077–1082. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pejchinovski M, Siwy J, Metzger J, Dakna M, Mischak H, Klein J, Jankowski V, Bae KT, Chapman AB, Kistler AD. Urine peptidome analysis predicts risk of end-stage renal disease and reveals proteolytic pathways involved in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease progression. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stalmach A, Husi H, Mosbahi K, Albalat A, Mullen W, Mischak H. Methods in capillary electrophoresis coupled to mass spectrometry for the identification of clinical proteomic/peptidomic biomarkers in biofluids. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1243:187–205. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1872-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertsias GK, Salmon JE, Boumpas DT. Therapeutic opportunities in systemic lupus erythematosus: state of the art and prospects for the new decade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1603–1611. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrm3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenz O, Elliot SJ, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Matrix metalloproteinases in renal development and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:574–581. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faber-Elmann A, Sthoeger Z, Tcherniack A, Dayan M, Mozes E. Activity of matrix metalloproteinase-9 is elevated in sera of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;127:393–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribbens C, Porras M, Franchimont N, Kaiser MJ, Jaspar JM, Damas P, Houssiau FA, Malaise MG. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-3 serum levels in rheumatic diseases: relationship with synovitis and steroid treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:161–166. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]