Abstract

Mycobacteria spontaneously form surface-associated multicellular communities, called biofilms, which display resistance to a wide range of exogenous stresses. A causal relationship between biofilm formation and emergence of stress resistance is not known. Here, we report that activation of a nitrogen starvation response regulator, GlnR, during the development of Mycobacterium smegmatis biofilms leads to peroxide resistance. The resistance arises from induction of a GlnR-dependent peroxide resistance (gpr) gene cluster comprising of 8 ORFs (MSMEG_0565-0572). Expression of gpr increases the NADPH to NADP ratio, suggesting that a reduced cytosolic environment of nitrogen-starved cells in biofilms contributes to peroxide resistance. Increased NADPH levels from gpr activity likely support the activity of enzymes involved in nitrogen assimilation, as suggested by a higher threshold of nitrogen supplement required by a gpr mutant to form biofilms. Together, our study uniquely interlinks a nutrient sensing mechanism with emergence of stress resistance during mycobacterial biofilm development. The gpr gene cluster is conserved in several mycobacteria that can cause nosocomial infections, offering a possible explanation for their resistance to peroxide-based sterilization of medical equipment.

Keywords: mycobacteria, biofilms, peroxide, starvation, GlnR

Introduction

Under most detergent-free in vitro conditions, mycobacterial species grow as surface-associated, three-dimensionally organized multicellular communities, called biofilms, which develop through dedicated genetic programs (Ojha et al., 2005, 2008; Weiss and Stallings, 2013; Gupta et al., 2015; Chuang et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017; Clary et al., 2018). Biofilm-like multicellular aggregates of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTMs) have also been reported from clinical and environmental specimens (Feazel et al., 2009; Bosio et al., 2012; Mullis and Falkinham, 2013; Fennelly et al., 2016). Biofilms of Mycobacterium avium, a prominent member of NTMs, have been implicated in pathogenesis (Rose and Bermudez, 2014), although biofilms of other pathogenic mycobacterial species including M. tuberculosis in the context of their host environments remain to be evaluated. Further clinical significance of mycobacterial biofilms is highlighted by at least two unique phenotypes, which are not associated with their single-cell planktonic counterparts. First, mycobacterial biofilms harbor a sizable subpopulation of bacilli that can survive extreme conditions including exposure to antibiotics and antiseptics (Falkinham, 2007; Ojha et al., 2008; Rose et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017; Clary et al., 2018). Second, biofilm growth of some mycobacterial species, including the pathogenic species M. canettii, fosters horizontal gene transfer (Nguyen et al., 2010; Boritsch et al., 2016), which possibly accelerates the propagation of drug resistance mutations in these species. Although mycobacterial biofilms are increasingly being recognized as potential targets for effective anti-mycobacterial strategies, mechanisms underlying the emergence of stress tolerance in biofilms remain unknown.

Biofilm development in the model mycobacterial species, M. smegmatis, is a genetically programmed process that appears to occur in distinct stages, each demarcated by its specific genetic requirements (Ojha et al., 2005; Ojha and Hatfull, 2007; Yang et al., 2017). While the cell surface glycopeptidolipid (GPL) is necessary for optimum substratum attachment, a nucleoid-associated protein, Lsr2, is required for cell–cell aggregation (Yang et al., 2017). Moreover, gene expression analysis of an extragenic suppressor of an lsr2 mutant revealed that cell–cell aggregation is a critical checkpoint in the developmental process (Yang et al., 2017). Expression levels of 83 genes are dependent on intercellular aggregation and aggregated growth (Yang et al., 2017), suggesting that the physicochemical interactions among cells induce transcriptional reprogramming for further maturation of architecture and physiological adaptation of resident cells.

A large number of 83 aggregation-dependent genes are under the control of GlnR, a conserved OmpR-like transcription factor that regulates nitrogen assimilation in response to its limited availability (Amon et al., 2008; Jenkins et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017). GlnR-dependent upregulation of three ammonium transporters (Amt), glutamine/glutamate synthases (GlnA) and nitrite/nitrate reductases facilitate efficient assimilation of environmental nitrogen in a cell (Amon et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2017). In addition, GlnR also induces urecase, amidase, xanthin permeases, which likely maximize the total intracellular nitrogen pool (Jenkins et al., 2013). However, the fact that GlnR induces over 100 genes in mycobacteria opens up questions about its wider influence in mycobacterial growth and adaptation. Studies in other species support a global role of GlnR, extending beyond nitrogen assimilation. In Saccharopolyspora erythraea, GlnR controls the expression of carbohydrate ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, thereby facilitating carbon uptake in response to nitrogen starvation (Liao et al., 2015). Similarly, GlnR also appears to control the expression of a key phosphate-sensing regulator, PhoP, in S. erythraea, implying a possible role of GlnR in phosphorous homeostasis (Yao and Ye, 2016). In addition to controlling nutrient balance in bacteria, GlnR also influences secondary metabolism in actinomycetes. In Streptomyces coelicolor and Streptomyces avermitilis, GlnR modulates the synthesis of antibiotics by directly regulating the transcription of pathway-specific genes (He et al., 2016; Urem et al., 2016). Lastly, GlnR also controls osmolyte levels in S. coelicolor (Shao et al., 2015), and pH homeostasis in Streptococcus salivarius (Huang and Chen, 2016).

Given a global role of GlnR in other species, we asked whether its activation during biofilm development in M. smegmatis has any significance beyond nitrogen assimilation. We report here that GlnR activation for nitrogen assimilation during biofilm growth also increases resistance to peroxide. The phenotype is caused by induction of a GlnR-dependent peroxide resistance (gpr) cluster of genes. The gpr cluster is comprised of 8 open reading frames (ORFs) – MSMEG_0565-0572– encoding genes of diverse functions. The upstream region of this uncharacterized operon has binding sites for both GlnR and SoxR, which is a MarR-family transcription factor that responds to oxidative stress to maintain redox homeostasis (Dietrich et al., 2008; Jenkins et al., 2013). However, gpr induction responds differently to GlnR and SoxR activities. While GlnR is a strong positive regulator of gpr, inducing it by ∼100-fold under limiting nitrogen, SoxR is a modest negative regulator causing twofold de-repression under peroxide stress. Emergence of peroxide resistance through a nutrient sensing mechanism provides a direct link between form and function of mycobacterial biofilms.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

All plasmids and strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively. Unless indicated, M. smegmatis, mc2155 (wild-type), was maintained at 37°C in 7H9ADC (Becton Dickinson) with 0.05% (v/v) Tween-80 for planktonic cultures. 7H10ADC agar (Becton Dickinson) was used for plate cultures. When necessary, hygromycin, kanamycin, and zeocin were added at 150, 20, or 25 μg/mL, respectively, to culture recombinant strains. Escherichia coli (DH5α) was grown at 37°C in LB broth or LB agar. Pellicle biofilms of M. smegmatis strains were grown as described earlier (Yang et al., 2017). Briefly, 10 μL of saturated planktonic cultures were inoculated into 10 mL of detergent-free Sauton’s medium or modified M63 medium in either 60 mm polystyrene dishes or 12-well polystyrene plates, and incubated stationary at 30°C untill indicated time. The N0 version of Sauton’s medium was prepared by omitting asparagine, and by replacing the ferric ammonium citrate with ferric citrate. The N1/2 version was prepared by reducing the initial concentrations of the above mentioned nitrogen sources by half.

Construction of Mutants and Plasmids

Mutations in M. smegmatis mc2155 were constructed using recombineering as described previously (Yang et al., 2017). Briefly, allelic exchange substrates for a given target gene were generated by SOEing-PCR on either side of a loxP flanked zeocin-resistant cassette using the respective primers listed in Supplementary Table S3. The purified PCR-products were electroporated into an electrocompetent recombineering strain, mc2155-pJV53-SacB, and plated on 7H10ADC with 25 μg/mL zeocin. Mutant genotypes of zeor colonies were confirmed by PCR. The recombineering plasmid, pJV53-SacB, was rescued from mutants by plating them on 7H10ADC with 15% sucrose, and screening sucrose resistant colonies for kanamycin sensitivity. The zeor marker was removed by excision using a Cre recombinase expressed from pCre-SacB, which was electroporated into the rescued mutant cells and transformants were screened for loss of zeor. The zeos colonies were screened on 7H10ADC with 15% sucrose to obtain clones without the pCre-SacB plasmid. The rescued unmarked mutants were complemented as indicated.

RNA-seq

Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 and ΔglnR were grown in detergent-free Sauton’s medium to form matured pellicle biofilms. Total RNA was extracted using a Qiagen RNeasy kit and contaminating DNA was removed with the turbo DNA-free kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For each sample, 5 μg of total RNA was processed for rRNA removal using the Ribo Zero kit (Illumina). Strand-specific DNA libraries were then prepared with 100 ng of mRNA using the Scriptseq Complete Kit- Bacteria (Illumina). Libraries were sequenced on the NextSeq500 platform (Illumina) and analyzed by Rockhopper (McClure et al., 2013) at default settings using the reference genome of M. smegmatis mc2 155 (NC_008596).

RT-qPCR

All oligonucleotides used for RT-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table S3. DNA-free RNA for RT-qPCR was extracted as described for RNA-seq. For each sample, 200 ng of RNA was used for reverse transcription using the Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-qPCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7000 fast RT-qPCR System (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green Master Mix following the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative expression of target gene is calculated either as 2-ΔCt(gene-SigA)or2-ΔCt(targetgene1-SigA)-ΔCt(targetgene2-SigA), in which SigA transcript was the endogenous control.

Antibiotics and Peroxide Sensitivity Assays

Exponential phase culture (OD600 = 0.3) of each strain grown in Sauton’s medium with 0.05% (v/v) Tween80 was harvested and washed once with phosphate buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-80 (PBST). Approximately 2 × 107 CFU/mL of each strain was resuspended in nitrogen-free (N0) Sauton’s medium with 0.05% (v/v) Tween80 at 37°C for 3 h. 400 μg/mL rifampicin, 1 μg/mL streptomycin or 20 mM H2O2 were added and incubated at 37°C for the indicated period; unexposed cultures were used as control. At the indicated time point, the exposed and unexposed cultures were diluted and plated on 7H10ADC for bacterial viability.

Measurement of Intracellular NADPH/NADP Ratio

Average intracellular NADPH/NADP ratios of planktonic culture and biofilms were measured according to previous publication with minor modifications (Vilcheze et al., 2005). Briefly, exponential phase planktonic and biofilm cultures from normal and N0 Sauton’s medium were harvested and washed once with PBS and then resuspended in PBS. Large aggregates from biofilms were broken up by 8–10 repeated passaging through 18-G needles. 1.5 mL single cell suspensions at density of 108–109 CFU/mL of each strain were pelleted and resuspended in 0.75 mL 0.2 M HCl (for NADP extraction) or 0.75 mL of 0.2 M NaOH (for NADPH extraction). After 10 min at 55°C, the suspensions were cooled to 0°C and neutralized by adding either 0.75 mL of 0.1 M NaOH for NADP extraction or 0.75 mL of 0.1 M HCl for NADPH extraction, while vortexing at high speed. After incubation for 10 min on ice, the suspensions were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were filtered and transferred to a new tube and used immediately. The concentrations of NADP and NADPH in the suspensions were determined by spectrophotometric measurement of the rate of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma # M2128) reduction by the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Sigma # G6378) in the presence of phenazine ethosulfate (Sigma # P4544) at 570 nm. The rate of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide reduction is proportional to the concentration of the nucleotides. Purified NADP (Sigma # 10128031001) and NADPH (Sigma # 10107824001) were used for standard curves, which were used for determination of the nucleotides in each sample. Serial dilutions of samples were tested to ensure the values were in the linear range of the NADP/NADPH standard curve.

Peroxide Sensitivity Assay for Microfluidic Biofilms

Biofilms as microcolonies were grown in a CellASIC ONIX (Cat # EV262) microfluidic platform, using CellASIC microfluidic plates (M04S-03) with headspace of 150 μm. Approximately 106 CFU/mL of bacteria in 10 μL media were perfused at a pressure of 1.7 kPa (0.25 psi) into each culture chamber of the plate for 6 s, followed by no perfusion for 30 min. This allowed optimum attachment of single cells to the culture chamber surface at a density that then grew into separate colony biofilms. For microfluidic culturing, detergent-free Sauton’s media was perfused across each culture chamber at the manufacturer’s recommendation of a dual pressure of 3.4 kPa (0.5 psi) at 37°C for 4 days to provide adequate nourishment and minimal stress to biofilm-like colonies. Incubation of ΔglnR was extended by an additional day to allow colony biofilms to grow to the same size as wild type. Colony biofilms were exposed to 20 mM H2O2 in Sauton’s media via microfluidic perfusion for 3 h followed by overnight perfusion of Sauton’s media with 1 μg/mL Calcein AM to stain survivors. Images of colony biofilms were collected by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) at 20× magnification under green channel (excitation 488 nm). Corresponding DIC image of each colony was also captured for overlaying the fluorescence signal. The images were analyzed by ImageJ. To compare the numbers of surviving cells among strains after H2O2 exposure, the number of green CalceinAM-stained cells was calculated from the maximum intensity projection of the z-stacks of each biofilm-like colony, normalized to colony surface area. For each strain, at least three biofilm-like colonies over two fields of view were analyzed.

Results

GlnR and Biofilm Formation in M. smegmatis

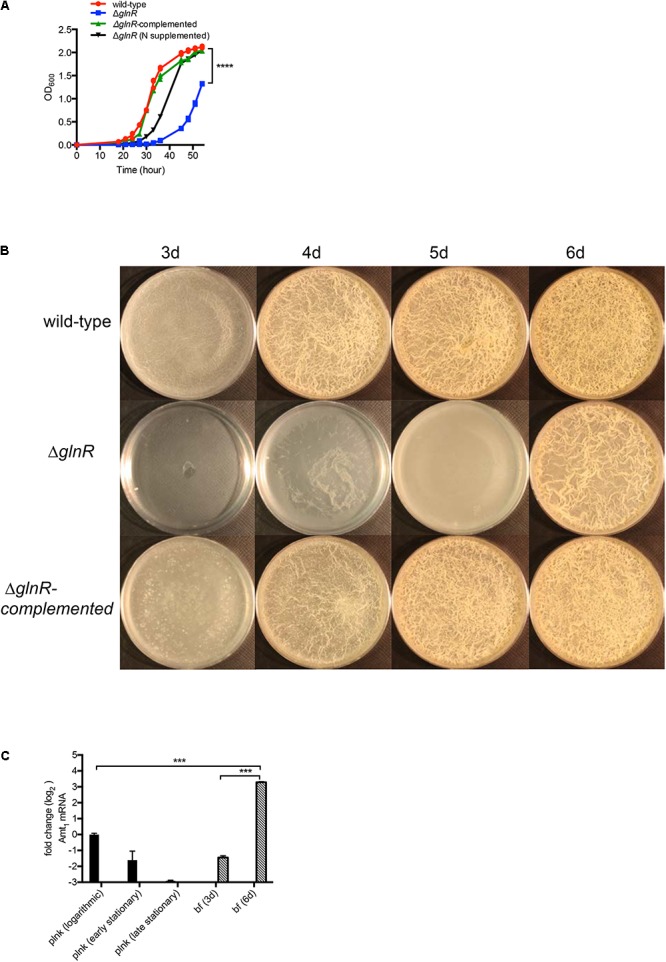

In our earlier study we identified 61 genes induced during maturation of M. smegmatis biofilms to be GlnR-dependent (Jenkins et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017). We therefore tested the effect of glnR mutation on development of M. smegmatis biofilms. Deletion of glnR produced no apparent phenotype in modified M63 medium, which was used in our earlier study (Yang et al., 2017) (Supplementary Figure S1). However, the mutation caused delayed planktonic growth and retarded biofilm development in Sauton’s medium (Figures 1A,B), which has poorer nitrogen source relative to the modified M63 medium. Lack of adequate nitrogen source in Sauton’s medium appeared to be the primary cause for ΔglnR phenotype, because the mutant growth could be substantially rescued by addition of casamino acid as supplemental nitrogen source (Figure 1A). Moreover, similar to the observation in modified M63 medium (Yang et al., 2017), late-stage (6-day) biofilms of wild-type (mc2155) M. smegmatis in Sauton’s medium also exhibited > 50-fold induction of a GlnR-dependent ammonium transporter (MSMEG_2425; Amt1) (Figure 1C). The induction was not observed in planktonic culture of the strain (Figure 1C), indicating that nitrogen availability in the medium is sufficiently high to prevent peak level of GlnR activation in planktonic cells, but not high enough to do so in biofilms. Based on these findings, and to maintain consistent growth conditions used in previous studies of GlnR mutant of M. smegmatis (Jenkins et al., 2013), we chose to use Sauton’s medium for this study.

FIGURE 1.

GlnR-dependent growth of M. smegmatis in planktonic and biofilm cultures in Sauton’s medium. (A) Planktonic growth of wild-type, ΔglnR and ΔglnR-complemented strains in Sauton’s medium with 0.05% (v/v) Tween80. Growth of ΔglnR is also rescued by supplementation of Sauton’s medium with 0.5% (w/v) casamino acid and 0.2% (w/v) ammonium sulfate. (B) A top-down view of pellicle biofilms of wild-type, ΔglnR and ΔglnR complemented strains in detergent-free Sauton’s medium at the indicated time point. (C) Expression of a GlnR-dependent ammonium transporter (Amt1) in planktonic (plnk) and biofilm (bf) cultures of wild-type M. smegmatis at indicated stages of growth. Logarithmic, early- and late-stationary phases of planktonic cultures correspond to OD 0.3, 1.5 and 2.5, respectively. Stages of biofilms at which cells were harvested are indicated as days after incubation. Expression was determined by real-time PCR and normalized with the SigA transcripts. Data represent mean of two independent experiments. ∗∗∗ and ∗∗∗∗ denote p < 0.001 and 0.0001, respectively (t-test).

Growth retardation of ΔglnR in planktonic cultures (Figure 1A) suggests that a basal activity of the regulator is necessary for optimum uptake of nitrogen sources. Delayed but matured biofilm development by ΔglnR raised the possibility of either an alternative mechanism of induction of GlnR-dependent genes, or existence of alternative pathways for nitrogen assimilation. To investigate these possibilities we compared the transcriptomes of 6-day biofilms of wild-type and ΔglnR strains. Expression of GlnR-dependent genes was significantly retarded in biofilms of ΔglnR mutant, compared to the wild-type (Supplementary Table S4), suggesting that secondary mechanisms of nitrogen assimilation are triggered in the mutant. This was further substantiated by upregulation in ΔglnR mutant biofilms of acetamidase (amiE or MSMEG_5335) and D-amino acid dehydrogenase (Supplementary Table S4).

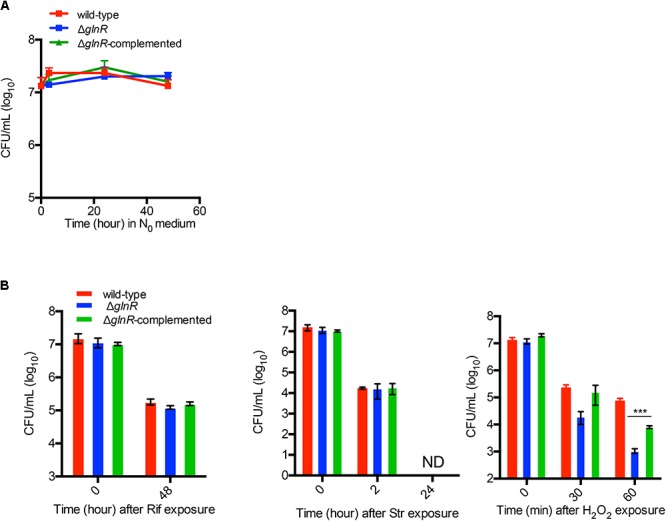

GlnR Activation and Peroxide Resistance

A global effect of GlnR on gene expression patterns (Jenkins et al., 2013; Jessberger et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017) raised a possibility that its activation during adaptation of M. smegmatis to low nitrogen may also impact other functions of cells. We investigated the effect of GlnR on persistence under stress exposure by comparing the sensitivity of nitrogen-starved cells of wild-type, ΔglnR and ΔglnR complemented strains to two commonly used anti-TB antibiotics: rifampicin (Rif) and streptomycin (Str) at 10X MIC. We also included hydrogen peroxide – a routinely used sterilizing agent for control of biofilm-related contaminants of surgical equipment in nosocomial settings (Falagas et al., 2011). We excluded isoniazid (INH) due to its selective activity on growing cells. We chose to test GlnR-activated planktonic cells by exposing them to N0-Sauton’s medium. GlnR was activated within 3 h of exposure to N0-Sauton’s medium (Supplementary Figure S2). Because viability of ΔglnR remains unaltered during the first 48 h of exposure to the N0-Sauton’s medium (Figure 2A), the exposure periods to the stressors were kept within this time limit. All three strains appeared equally sensitive to high concentrations of Rif and Str (Figure 2B). Interestingly, ΔglnR mutant showed significantly greater sensitivity to peroxide exposure in a 60-min period (Figure 2B), and the phenotype was substantially reversed in the complemented strain (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

GlnR-dependent resistance of M. smegmatis to hydrogen peroxide under nitrogen-limiting condition. (A) Survival of wild-type, ΔglnR and ΔglnR-complemented strains in nitrogen-free Sauton’s (N0) medium for up to 48 h. Exponentially growing cells (OD 0.3) cultured in Sauton’s medium with 0.05% (v/v) Tween80 were washed and resuspended in N0 medium for indicated time points prior to plating the dilutions on 7H10ADC plate. (B) Effect of streptomycin (Str; 1 μg/mL), rifampicin (Rif; 400 μg/mL), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 20 mM) on survival of wild-type, ΔglnR and ΔglnR -complemented strains in N0 medium. Cells were incubated in N0 medium for 6 h prior to exposure to each condition for the indicated period of time. Data are representative of mean of three biologically independent experiments. ∗∗∗ indicates p (t-test) < 0.001.

Peroxide Resistance Arises From GlnR-Dependent Induction of gpr

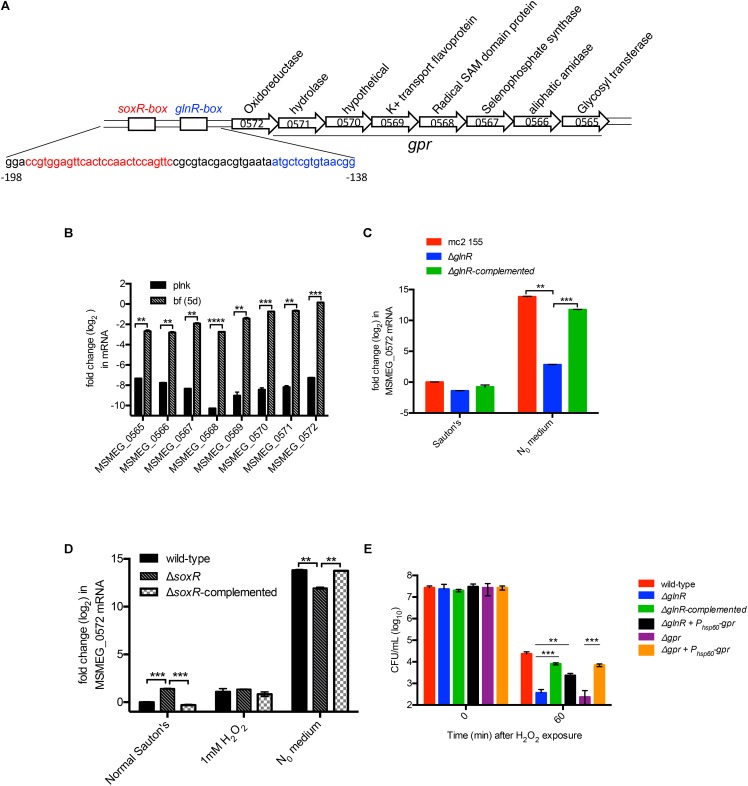

To determine the basis of GlnR-dependent peroxide resistance we analyzed the nucleotide sequence of GlnR-dependent genes. Upstream region of one of the GlnR-dependent operons comprising of 8 ORFs (MSMEG_0565 to MSMEG_0572) contained binding sites for both GlnR and SoxR (Dietrich et al., 2008; Jenkins et al., 2013) (Figure 3A). Since SoxR plays important role in redox homeostasis in many bacterial species (Storz and Imlay, 1999), we speculated that this locus could be under dual regulation of SoxR and GlnR, and that its activation by either of the two regulators possibly confers peroxide resistance. Biofilm-specific expression of all 8 ORFs in Sauton’s medium was verified by RT-qPCR (Figure 3B). We next tested the role of SoxR and GlnR in activation of the operon using MSMEG_0572 as a representative member. As expected from earlier studies (Jenkins et al., 2013; Jessberger et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017), expression of the operon in wild-type cells was highly (>500 fold) induced upon 3-h exposure to N0 Sauton’s medium in a GlnR-dependent manner (Figure 3C). However, SoxR activity appears to have very modest (∼2-fold) negative effect on the induction of the operon (Figure 3D). Interestingly, exposure to peroxide did not induce the operon (Figure 3D). Together, these expression profiles indicate that regulation of the operon exclusively depends on GlnR under the tested conditions.

FIGURE 3.

GlnR-dependent peroxide resistance in M. smegmatis results from activation of a cluster comprising of eight genes (MSMEG_0565 to 0572), called gpr. (A) Schematic representation of gpr and the upstream GlnR and SoxR-binding regions, called GlnR-box and SoxR-box, respectively. Nucleotide sequence of the two regions are indicated below in their corresponding color codes. (B) Expression of each of the eight genes in gpr cluster in logarithmic phase (OD 0.3) planktonic culture and in 6-day biofilms, both cultured in Sauton’s medium. Transcripts were normalized with SigA transcripts. (C) GlnR-dependent induced expression of gpr cluster (represented by MSMEG_0572) in N0 medium. Indicated strains were cultured in normal Sauton’s medium untill OD 0.3 and transferred to N0 medium for 3 h prior to mRNA analysis by real-time PCR. Cells collected from Sauton’s medium before exposure to N0 medium were used as reference. Fold-change relative to transcript level in wild-type cells in Sauton’s medium was calculated. (D) Expression of gpr (represented by MSMEG_0572) is unresponsive to SoxR and peroxide in Sauton’s medium. Indicated strains were cultured and processed as described for (C), except that an additional set exposed to a sub-lethal concentration (1 mM) of H2O2 for 60 min was also included. (E) Expression of gpr is sufficient to restore peroxide resistance in ΔglnR mutant. Viability of the indicated strains before (0 min) and after 30 min of exposure to 20 mM H2O2. Data in (B–E) represent mean of three biologically independent experiments. ∗∗ and ∗∗∗ indicates p (t-test) < 0.01 and <0.001, respectively.

We next asked if expression of MSMEG_0565-72 operon is necessary and sufficient to exhibit GlnR-dependent peroxide resistance. A deletion mutant of the operon exhibited similar level of peroxide sensitivity as ΔglnR under N0-Sauton’s medium (Figure 3E), and the phenotype was rescued by plasmid-borne expression of the operon by a constitutive (Phsp60) promoter. Importantly, constitutive expression of the operon by Phsp60 promoter was also able to substantially rescue peroxide sensitivity of ΔglnR, indicating that peroxide resistance in M. smegmatis is primarily contributed by GlnR-dependent activation of MSMEG_0565-72 operon. We therefore call this operon as GlnR-dependent peroxide resistance or gpr.

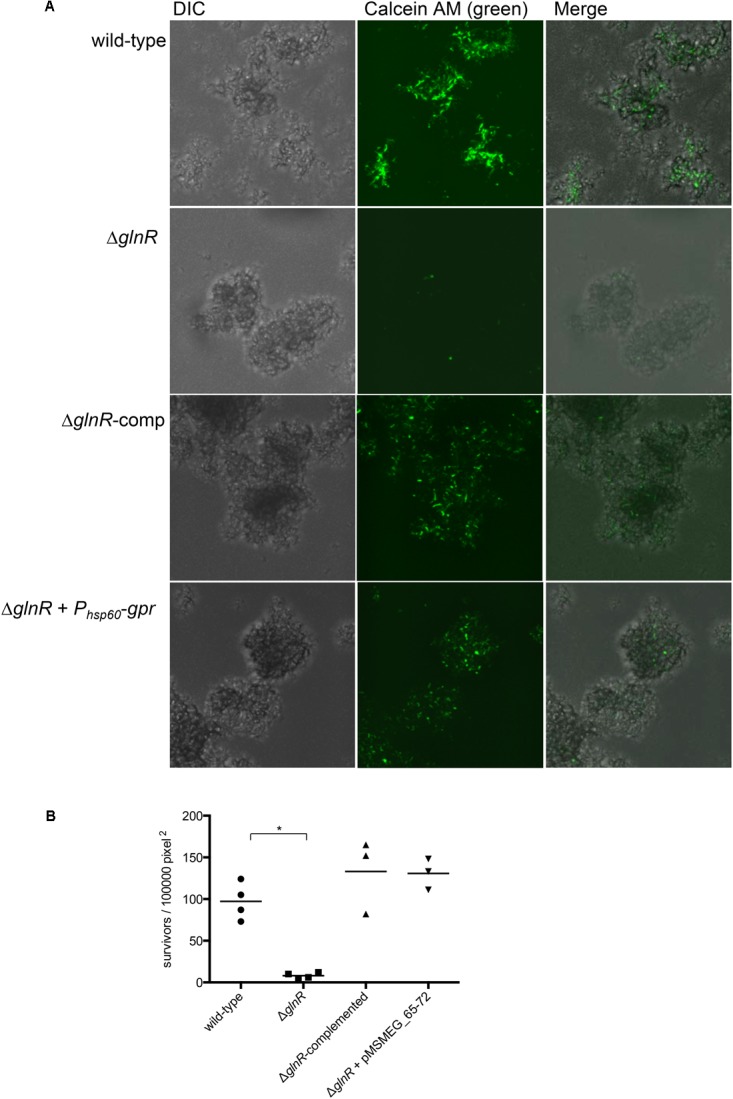

To obtain a direct evidence for roles of glnR and gpr in peroxide resistance of M. smegmatis biofilms, we employed a microfluidic-based growth model to visualize surviving cells in peroxide exposed biofilms by confocal microscopy. To calibrate the growth model we first determined the timing of activation of GlnR by using a reporter strain of M. smegmatis, which harbored constitutively expressing mCherry and Dendra-2 fused to the promoter of Amt1 (MSMEG_2425). Expression of Dendra-2 in biofilms could be visualized after 4 days of growth in Sauton’s medium (Supplementary Figure S3). Subsequent incubation led to bacterial growth in the flow channels, leading to increased backflow pressure. We therefore used 4-day stage of wild type biofilms for our analysis, although biofilms of ΔglnR were cultured for an additional day to allow them to achieve similar size as wild-type. Following peroxide exposure, live cells in biofilms were probed by calcein AM, which remains non-fluorescent until its passive diffusion to the cytosol and hydrolysis by intracellular hydrolases produces fluorescent calcein (Rego et al., 2017). Compared to wild-type biofilms, the number of viable cells in peroxide exposed ΔglnR biofilms was significantly reduced (Figures 4A,B). The mutant phenotype could be complemented by plasmid-borne expression of either glnR from its native promoter or a constitutive expression of gpr from the hsp60 promoter. We thus conclude that induced expression of gpr upon activation of GlnR during maturation of M. smegmatis biofilms directly contributes to their peroxide resistance.

FIGURE 4.

GlnR-dependent expression of gpr induces peroxide resistance in M. smegmatis biofilms. (A) Visualization of peroxide resistant survivors (green) in 4-day biofilms of the indicated strains. Biofilms, cultured in CellASIC Onix microfluidic system perfused with Sauton’s medium, were exposed with the medium containing 20 mM H2O2 for 3 h prior to staining with Calcein AM (1 μg/mL). Distributions of live cells (green) in colony biofilms were determined from images acquired by confocal microscopy. The micrographs represent maximum intensity projection of green signal across z-stacks analyzed by ImageJ. (B) A summary plot of frequency of green cells in four independent biofilms of wild-type and mutants, and three for the complemented strains. Data represent mean from 3 to 4 independent biofilms of each strain formed in a microfluidic chamber. ∗denotes p (Mann–Whitney) < 0.05.

Physiological Role of gpr in Biofilm Development

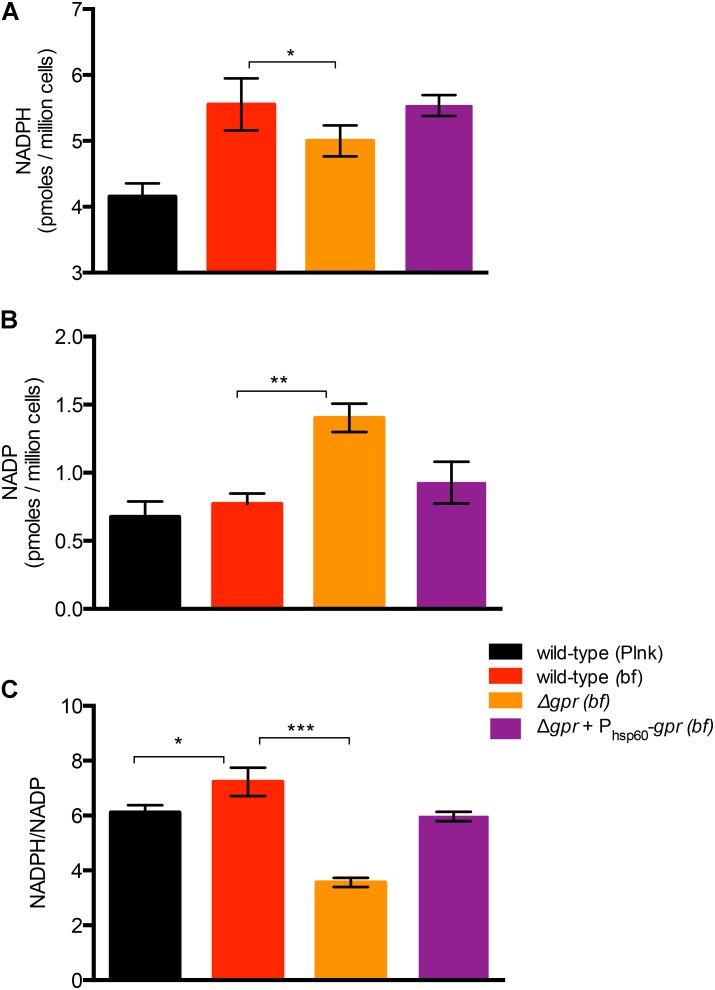

Nitrogen assimilation in majority of bacterial species occurs at the expense of the redox currency, NADPH (van Heeswijk et al., 2013), which serves as a co-factor for several enzymes, including glutamate synthase, involved in synthesis of ammonia and amino acids. Two subunits of NADPH-dependent glutamate synthase, encoded by MSMEG_3225 and MSMEG_3226, are induced in biofilms by ∼30-fold (Yang et al., 2017), and their induction is GlnR-dependent (Supplementary Table S4). This suggests a greater demand of NADPH for nitrogen-starved cells in biofilms. This is consistent with ∼5-fold increase NADPH/NADP ratio after 3 h of incubation of wild-type cells in N0-Sauton’s medium, relative to normal Sauton’s medium (Supplementary Figure S4). The increase in the ratio appears to be contributed by a modest decrease (<2-fold) in NADPH, relative to NADP (∼7-fold), suggesting that NADPH is likely regenerated from existing NADP by reductases induced in nitrogen-starved cells. Regeneration of NADPH, as opposed to new synthesis, is preferred perhaps due to lack of nutrients in N0-Sauton’s medium. We therefore hypothesized that induction of the putative reductases encoded by genes in gpr cluster likely regenerate NADPH pool to meet the metabolic demand of nitrogen-starved cells. Nitrogen-starved Δgpr mutant indeed produced a lower NADPH/NADP ratio than wild-type and complemented cells (Supplementary Figure S4). The decreased ratio in the mutant was due to reciprocal change in NADP and NADPH levels, consistent with the idea that existing NADP are reduced to regenerate NADPH (Supplementary Figure S4).

To test gpr-dependent redox homeostasis during biofilm development, we first compared the NADPH and NADP levels between planktonic and wild-type cells. Interestingly, the average NADPH/NADP ratio in biofilm cells of wild-type increased by ∼18%, relative to its planktonic counterpart, indicating that biofilm cells have a more reduced cytosolic environment (Figure 5C). The increase in the ratio resulted from a disproportionate increase in NADPH (∼34%), compared to NADP, which was maintained at a steady level (Figures 5A,B). This suggests increase in both new synthesis of NADP and its reduction. This was in contrast to the scenario observed in planktonic cells in N0-Sauton’s medium (Supplementary Figure S4). Expectedly, the average NADPH/NADP ratio in biofilms of Δgpr mutant declined by nearly 50%, relative to wild-type, and the phenotype was substantially restored in the complemented strain (Figures 5A–C). Decline in the ratio in the mutant was due to accumulation of NADP, with concomitant decrease in NADPH (Figures 5A–C). Together, we infer that GlnR-dependent induction of gpr in a subpopulation of biofilm cells that experience nitrogen starvation is critical for maintenance of higher NADPH pool to meet their metabolic demand.

FIGURE 5.

Role of gpr in maintenance of redox homeostasis of M. smegmatis. (A,B) Levels of oxidized (NADP) form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate in biofilms of wild-type, Δgpr and the complemented strains cultured in normal Sauton’s medium. (C) Ratio of NADPH to NADP calculated from (A,B). Data represent mean of three biologically independent experiments ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate p (t-test) < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

A corollary to gpr-dependent redox homeostasis is that Δgpr mutant has impaired ability to assimilate nitrogen that impacts its growth in biofilms. Relative to wild-type, biofilm growth of Δgpr cells in normal Sauton’s medium was moderately retarded, but the effect was more pronounced in nitrogen-depleted (N1/2) Sauton’s medium, which has been shown to increase GlnR-dependency of M. smegmatis in biofilms (Yang et al., 2017) (Figures 6A,B). A mutant lacking a GlnR-dependent operon (MSMEG_2425-27), which was previously shown to display nitrogen-responsive biofilm defect (Yang et al., 2017), served as a reference in our analysis of Δgpr phenotype (Figures 6A,B). Phenotype of Δgpr could be complemented by plasmid-borne expression of gpr (Figures 6A,B). The defect was specific to biofilm culture, as no difference in planktonic growth of Δgpr mutant was observed (Figure 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Role of gpr in biofilm formation of M. smegmatis. (A) A top-down view of pellicle biofilms of the indicated strains after days of growth in detergent-free Sauton’s medium and modified Sauton’s medium with half the normal nitrogen source (N1/2). In contrast to the wild type, which formed thick-textured biofilms in both medium, Δamt1 and Δgpr mutants formed untextured biofilms in N1/2 Sauton’s medium, and the phenotype was partially rescued by nitrogen restoration in normal Sauton’s medium. (B) Biomass of the pellicles described in (A) from three independent experiments. The order of columns in the plot corresponds to the order in which the strains are indicated in (A). Data represent mean of three biologically independent experiments. ∗∗, ∗∗∗, and ∗∗∗∗ denote p < 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively (t-test). (C) Planktonic growth of the indicated strains in N1/2 Sauton’s medium.

Our preliminary attempts to identify specific gene(s) of gpr that could complement Δgpr phenotype were unsuccessful (data not shown), suggesting that interaction between multiple genes of the cluster give rise to its function.

Discussion

Mycobacteria express and utilize dedicated genes to build stress resistant biofilms (Richards and Ojha, 2014), raising a possibility that genetic programs involved in adaptation of resident cells within the architecture, and those in stress resistance overlap with each other. In this study, we provide evidence supporting this hypothesis by demonstrating a causal relationship between nitrogen-starvation response exhibited by biofilm cells and emergence of peroxide resistance in these cells. Peroxide resistance is likely a result of recalibration of NADPH/NADP ratio, skewed toward a more reduced cytosolic environment, to meet the increasing demand of NADPH for nitrogen assimilation in starved cells. These cells likely reside in interiors of biofilms, as suggested by localization of GlnR-activated cells in these regions of biofilms (Supplementary Figure S3). It is noteworthy that E. coli also acquire greater resistance to peroxide upon exposure to nitrogen starvation (Jenkins et al., 1988), although underlying mechanism remains unknown in this species.

The contribution of gpr cluster in maintenance of NADPH pool suggests specific function of encoded reductases in the process, although identity of these enzymes and their mechanisms remain open to further investigation. MSMEG_0572 appears to represent DsrE-family reductases, which are conserved in a wide range of environmental species of bacteria. Moreover, similar to MSMEG_0572, its orthologs in these species exhibit a syntenic arrangement with respect to the remaining seven genes of gpr cluster, suggesting that the entire cluster has migrated across genomes during evolution. This also raises the possibility that the cluster could function as a unit, rendering a possible explanation to our inability in identifying individual genes responsible for the phenotype associated with Δgpr strain. Interestingly, one of the genes in the cluster, MSMEG_0567, is homologous to selenophosphate synthetase, which is directly involved in the synthesis of selenocysteine (Sec) (Turanov et al., 2011). Sec in prokaryotes is incorporated in polypeptide by a set of specialized accessory factors, which facilitate Sec-tRNA to decode the UGA codon (Krol, 2002). The UGA codon in mRNA decoded as Sec must have a downstream Sec insertion sequence (SECIS), which forms a unique stem-loop structure recognized by the accessory factors that recruit Sec-tRNA during translation (Krol, 2002). Bioinformatics search using bSECIS program (Zhang and Gladyshev, 2005) of all gpr ORFs identified a SECIS element comprising of 39 bp downstream of UGA codon of MSMEG_0571, suggesting that the codon in this ORF is decoded as Sec, thereby giving rise to a selenoprotein. The resulting selenoprotein is extended by 518 amino acids (aa) to terminate at the originally annotated stop codon (UAG) of MSMEG_0569 (Supplementary Figure S5). BLAST search of thus encoded 818aa long selenoprotein encompassing MSMEG_0567 to MSMEG_0569 reveals a conserved nitrilase-like domain in the N-terminal region and a flavin-dependent oxidoreductase domain in the C-terminal region (Supplementary Figure S5). This domain architecture is consistent with the fact that majority of the selenopoteins known so far are oxidoreductase (Hatfield et al., 2014), supporting the function of gpr cluster in redox homeostasis. The gpr cluster also includes a putative aliphatic amidase (MSMEG_0566), which could directly contribute to nitrogen assimilation.

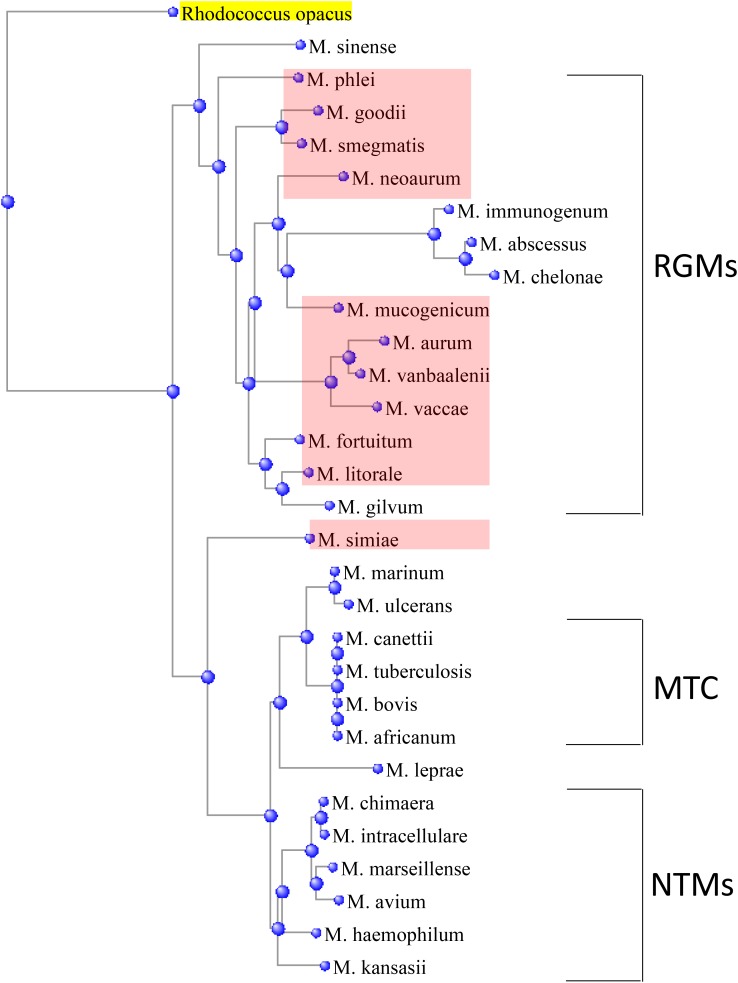

A homology search for gpr cluster in 29 mycobacterial species reveals its presence in only a few members, which are evolutionarily linked based on 16S rRNA phylogeny (Figure 7). Most of these species are classified as rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) (Runyon, 1959). Interestingly, gpr is absent in a clinically important RGM, M. abscessus, suggesting that its transfer to RGM from a common ancestor is a relatively recent evolutionary event. Moreover, evidence of horizontal gene transfer is supported by the presence of gpr in the only slow-growing non-tuberculosis mycobacteria, M. simiae (Figure 7). Presence of gpr in M. mucogenicum, M. goodii, and M. simiae, which are emerging pathogens in nosocomial infections (van Ingen et al., 2008; Adekambi, 2009; Parikh and Grant, 2017; Salas and Klein, 2017), raises clinical significance of our findings and possibly offers insight into resistance of these species to peroxide-mediated sterilization of surgical and medical equipment.

FIGURE 7.

Presence of gpr locus in a subset (shaded pink) of rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGMs), which are depicted in relationship to the other RGMs, slow-growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTMs), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTC), based on their similarities in 16S rRNA sequences. A member of NTM, Mycobacterium simiae, is an outlier. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by distance method using Rhodococcus opacus as an outgroup.

Lack of gpr in a majority of mycobacteria suggests a different mechanism of GlnR-dependent nitrogen assimilation in these species, consistent with the differences between GlnR activities in M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis as described previously (Williams et al., 2015). Further understanding of molecular underpinnings of these differences is likely to identify a role of GlnR in biofilm development and associated stress tolerance in these species.

Author Contributions

AO and YY conceived this study. YY, JR, JG, and AO designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments. YY and AO wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged technical help from Advanced Light Microscopy and Image Analysis, Applied Genomic Technologies, and Media core laboratories of the Wadsworth Center.

Footnotes

Funding. AO received funding from the NIH (AI107595).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01428/full#supplementary-material

References

- Adekambi T. (2009). Mycobacterium mucogenicum group infections: a review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15 911–918. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amon J., Brau T., Grimrath A., Hanssler E., Hasselt K., Holler M., et al. (2008). Nitrogen control in Mycobacterium smegmatis: nitrogen-dependent expression of ammonium transport and assimilation proteins depends on the OmpR-type regulator GlnR. J. Bacteriol. 190 7108–7116. 10.1128/JB.00855-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boritsch E. C., Khanna V., Pawlik A., Honore N., Navas V. H., Ma L., et al. (2016). Key experimental evidence of chromosomal DNA transfer among selected tuberculosis-causing mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 9876–9881. 10.1073/pnas.1604921113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosio S., Leekha S., Gamb S. I., Wright A. J., Terrell C. L., Miller D. V. (2012). Mycobacterium fortuitum prosthetic valve endocarditis: a case for the pathogenetic role of biofilms. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 21 361–364. 10.1016/j.carpath.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y. M., Dutta N. K., Hung C. F., Wu T. C., Rubin H., Karakousis P. C. (2016). Stringent response factors PPX1 and PPK2 play an important role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism, biofilm formation, and sensitivity to isoniazid in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 6460–6470. 10.1128/AAC.01139-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clary G., Sasindran S. J., Nesbitt N., Mason L., Cole S., Azad A., et al. (2018). Mycobacterium abscessus smooth and rough morphotypes form antimicrobial-tolerant biofilm phenotypes but are killed by acetic acid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62:e1782-17. 10.1128/AAC.01782-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich L. E., Teal T. K., Price-Whelan A., Newman D. K. (2008). Redox-active antibiotics control gene expression and community behavior in divergent bacteria. Science 321 1203–1206. 10.1126/science.1160619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falagas M. E., Thomaidis P. C., Kotsantis I. K., Sgouros K., Samonis G., Karageorgopoulos D. E. (2011). Airborne hydrogen peroxide for disinfection of the hospital environment and infection control: a systematic review. J. Hosp. Infect. 78 171–177. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkinham J. O., III. (2007). Growth in catheter biofilms and antibiotic resistance of Mycobacterium avium. J. Med. Microbiol. 56(Pt 2), 250–254. 10.1099/jmm.0.46935-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feazel L. M., Baumgartner L. K., Peterson K. L., Frank D. N., Harris J. K., Pace N. R. (2009). Opportunistic pathogens enriched in showerhead biofilms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 16393–16399. 10.1073/pnas.0908446106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennelly K. P., Ojano-Dirain C., Yang Q., Liu L., Lu L., Progulske-Fox A., et al. (2016). Biofilm formation by Mycobacterium abscessus in a lung cavity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193 692–693. 10.1164/rccm.201508-1586IM [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K. R., Kasetty S., Chatterji D. (2015). Novel functions of (p)ppGpp and Cyclic di-GMP in mycobacterial physiology revealed by phenotype microarray analysis of wild-type and isogenic strains of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 2571–2578. 10.1128/AEM.03999-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield D. L., Tsuji P. A., Carlson B. A., Gladyshev V. N. (2014). Selenium and selenocysteine: roles in cancer, health, and development. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39 112–120. 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. M., Zhu H., Zheng G. S., Liu P. P., Wang J., Zhao G. P., et al. (2016). Direct involvement of the master nitrogen metabolism regulator GlnR in antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. J. Biol. Chem. 291 26443–26454. 10.1074/jbc.M116.762476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. C., Chen Y. Y. (2016). Role of VicRKX and GlnR in pH-dependent regulation of the Streptococcus salivarius 57.I Urease Operon. mSphere 1:e33-16. 10.1128/mSphere.00033-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins D. E., Schultz J. E., Matin A. (1988). Starvation-induced cross protection against heat or H2O2 challenge in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 170 3910–3914. 10.1128/jb.170.9.3910-3914.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V. A., Barton G. R., Robertson B. D., Williams K. J. (2013). Genome wide analysis of the complete GlnR nitrogen-response regulon in Mycobacterium smegmatis. BMC Genomics 14:301. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger N., Lu Y., Amon J., Titgemeyer F., Sonnewald S., Reid S., et al. (2013). Nitrogen starvation-induced transcriptome alterations and influence of transcription regulator mutants in Mycobacterium smegmatis. BMC Res. Notes 6:482. 10.1186/1756-0500-6-482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol A. (2002). Evolutionarily different RNA motifs and RNA-protein complexes to achieve selenoprotein synthesis. Biochimie 84 765–774. 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01405-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C. H., Yao L., Xu Y., Liu W. B., Zhou Y., Ye B. C. (2015). Nitrogen regulator GlnR controls uptake and utilization of non-phosphotransferase-system carbon sources in actinomycetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 15630–15635. 10.1073/pnas.1508465112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure R., Balasubramanian D., Sun Y., Bobrovskyy M., Sumby P., Genco C. A., et al. (2013). Computational analysis of bacterial RNA-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:e140. 10.1093/nar/gkt444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullis S. N., Falkinham J. O., III. (2013). Adherence and biofilm formation of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare and Mycobacterium abscessus to household plumbing materials. J. Appl. Microbiol. 115 908–914. 10.1111/jam.12272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K. T., Piastro K., Gray T. A., Derbyshire K. M. (2010). Mycobacterial biofilms facilitate horizontal DNA transfer between strains of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 192 5134–5142. 10.1128/JB.00650-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A., Anand M., Bhatt A., Kremer L., Jacobs W. R., Jr., Hatfull G. F. (2005). GroEL1: a dedicated chaperone involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis during biofilm formation in mycobacteria. Cell 123 861–873. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A., Hatfull G. F. (2007). The role of iron in Mycobacterium smegmatis biofilm formation: the exochelin siderophore is essential in limiting iron conditions for biofilm formation but not for planktonic growth. Mol. Microbiol. 66 468–483. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05935.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A. K., Baughn A. D., Sambandan D., Hsu T., Trivelli X., Guerardel Y., et al. (2008). Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis biofilms containing free mycolic acids and harbouring drug-tolerant bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 69 164–174. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06274.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh R. B., Grant M. (2017). Mycobacterium goodii endocarditis following mitral valve ring annuloplasty. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 16:14. 10.1186/s12941-017-0190-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rego E. H., Audette R. E., Rubin E. J. (2017). Deletion of a mycobacterial divisome factor collapses single-cell phenotypic heterogeneity. Nature 546 153–157. 10.1038/nature22361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J. P., Ojha A. K. (2014). Mycobacterial Biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2:MGM2-0004-2013. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0004-2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S. J., Babrak L. M., Bermudez L. E. (2015). Mycobacterium avium possesses extracellular DNA that contributes to biofilm formation, structural integrity, and tolerance to antibiotics. PLoS One 10:e0128772. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S. J., Bermudez L. E. (2014). Mycobacterium avium biofilm attenuates mononuclear phagocyte function by triggering hyperstimulation and apoptosis during early infection. Infect. Immun. 82 405–412. 10.1128/IAI.00820-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyon E. H. (1959). Anonymous mycobacteria in pulmonary disease. Med. Clin. North Am. 43 273–290. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)34193-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas N. M., Klein N. (2017). Mycobacterium goodii: an emerging nosocomial pathogen: a case report and review of the literature. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 25 62–65. 10.1097/IPC.0000000000000428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z., Deng W., Li S., He J., Ren S., Huang W., et al. (2015). GlnR-mediated regulation of ectABCD transcription expands the role of the GlnR regulon to osmotic stress management. J. Bacteriol. 197 3041–3047. 10.1128/JB.00185-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz G., Imlay J. A. (1999). Oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2 188–194. 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turanov A. A., Xu X. M., Carlson B. A., Yoo M. H., Gladyshev V. N., Hatfield D. L. (2011). Biosynthesis of selenocysteine, the 21st amino acid in the genetic code, and a novel pathway for cysteine biosynthesis. Adv. Nutr. 2 122–128. 10.3945/an.110.000265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urem M., Swiatek-Polatynska M. A., Rigali S., van Wezel G. P. (2016). Intertwining nutrient-sensory networks and the control of antibiotic production in Streptomyces. Mol. Microbiol. 102 183–195. 10.1111/mmi.13464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heeswijk W. C., Westerhoff H. V., Boogerd F. C. (2013). Nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli: putting molecular data into a systems perspective. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77 628–695. 10.1128/MMBR.00025-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ingen J., Boeree M. J., Dekhuijzen P. N., van Soolingen D. (2008). Clinical relevance of Mycobacterium simiae in pulmonary samples. Eur. Respir. J. 31 106–109. 10.1183/09031936.00076107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcheze C., Weisbrod T. R., Chen B., Kremer L., Hazbon M. H., Wang F., et al. (2005). Altered NADH/NAD+ ratio mediates coresistance to isoniazid and ethionamide in mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 708–720. 10.1128/AAC.49.2.708-720.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L. A., Stallings C. L. (2013). Essential roles for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rel beyond the production of (p)ppGpp. J. Bacteriol. 195 5629–5638. 10.1128/JB.00759-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. J., Jenkins V. A., Barton G. R., Bryant W. A., Krishnan N., Robertson B. D. (2015). Deciphering the metabolic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to nitrogen stress. Mol. Microbiol. 97 1142–1157. 10.1111/mmi.13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Thomas J., Li Y., Vilcheze C., Derbyshire K. M., Jacobs W. R., et al. (2017). Defining a temporal order of genetic requirements for development of mycobacterial biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 105 794–809. 10.1111/mmi.13734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L. L., Ye B. C. (2016). Reciprocal regulation of GlnR and PhoP in response to nitrogen and phosphate limitations in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82 409–420. 10.1128/AEM.02960-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Gladyshev V. N. (2005). An algorithm for identification of bacterial selenocysteine insertion sequence elements and selenoprotein genes. Bioinformatics 21 2580–2589. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.