Abstract

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), also referred to as non-celiac wheat sensitivity (NCWS), is a clinical syndrome characterized by both intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms responsive to the withdrawal of gluten-containing food from the diet. The aim of this review is to summarize recent advances in research and provide a brief overview of the history of the condition for the benefit of professionals working in gastroenterology. Academic databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar were searched using key words such as ”non-celiac gluten sensitivity”, “gluten related disorders”, and the studies outlined in reference page were selected and analysed.

Most of the analysed studiers agree that NCGS would need to be diagnosed only after exclusion of celiac disease and wheat allergy, and that a reliable serological marker is not available presently. The mechanisms causing symptoms in NCGS after gluten ingestion are largely unknown, but recent advances have begun to offer novel insights. The estimated prevalence of NCGS, at present, varies between 0.6 and 6%. There is an overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and NCGS with regard to the similarity of gastrointestinal symptoms. The histologic characteristics of NCGS are still under investigation, ranging from normal histology to slight increase in the number of T lymphocytes in the superficial epithelium of villi. Positive response to gluten free diet for a limited period (e.g., 6 weeks), followed by the reappearance of symptoms after gluten challenge appears, at this moment, to be the best approach for confirming diagnosis. The Salerno expert criteria may help to diagnose NCGS accurately in particular for research purposes but it has limited applicability in clinical practice.

Key Words: Celiac disease, Non celiac gluten sensitivity, Wheat allergy

Non Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is a clinical syndrome characterized by both intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms responsive to the withdrawal of wheat and related cereals from the diet (1). These symptoms have been found to relapse following a gluten challenge NCGS may be diagnosed only after exclusion of celiac disease (CD) and wheat allergy as an established serological marker is not yet available. NCGS is often suspected by the patients themselves leading to self-diagnosis and self-treatment (2). It is important to consider that wheat, in addition to gliadin, contains a number of other potentially bioactive components that may cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as amylase trypsin inhibitors (ATIs) (3) and fermentable oligo-disaccharides-monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) (4). A large number of IBS patients appear to respond to GFD, suggesting that gluten-containing food may be a trigger for IBS symptoms in at least a significant subset of patients (5).

History of NCGS

The concept of NCGS was described for the first time in 1978 by Ellis et al. (6). These authors reported some patients with abdominal pain and diarrhea without histological duodenal lesions who improved after GFD. Similarly, in 1980, Cooper et al. (7) reported 8 females with abdominal pain, diarrhea and normal duodenal histology who again improved with GFD, with reoccurrence of symptoms following gluten challenge. The consensus findings of the first international expert meeting where NCGS has been defined was published in 2012 (8).

Composition of Wheat

White Flour comprises about 80% starch and 10% protein (9). The indigestible oligosaccharides such as fructo-oligosaccharides and fructans constitute 13.4% of the dietary fiber in wheat (9) the latter contains also a considerable amount of indigestible ologisacharides galactans (9). Gluten represents 75-80% of the wheat proteins and it comprises 2 major groups: the glutenin and the gliadin proteins. Due to their amino acid sequences, the gluten proteins are partially resistant to digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract, thus resulting in the formation of various peptides with a high degree of potential immunogenicity in the small intestine (10).

Pathophysiology of NCGS

The mechanisms that determine symptoms in NCGS after gluten ingestion are still largely unknown, but it is evident that there are marked differences with CD, a condition that is related to an autoimmune process with adaptive immune system activation, as well as wheat allergy (WA), which is IgE-dependent (1). Sapone et al. (8) (6) suggests that intestinal permeability and adaptive immune system may have a less pronounced role in NCGS than in CD. Having said that, the presentation of NCGS is not yet fully understood and this issue is controversial as we explain below.

It is worth noting that gluten has been found to have some intrinsic biologic properties (11) causing alteration of cellular morphology and motility (12), as well as cytoskeleton organization and intercellular contact through the tight junction proteins (13).

Some Gliadin peptides bind the TLR2 receptor that increase Interleukin 1 production, a proinflammatory cytokine, through the mediation of Myd88 (14). MyD88 is a key protein mediating the release of zonulin in response to gluten ingestion and this increases the mucosal permeability. NCGS patients show higher levels of TLR2 compared to those with CD, causing dysbiosis similar to that observed in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (15).

The intestinal cells exposed to gluten show a reduced survival, as suggested by increased apoptosis and a reduction of nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) and protein synthesis (16).

A study by Junker et al. (3) pointed the attention toward other molecules in wheat, the ATIs, capable of triggering the Toll-like receptor 4 pathways leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines (3).

In addition, non-protein components of wheat, the fermentable oligo-disaccharides-monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs), have been found to cause non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms in the context of NCGS (1).

In 2016, Uhde, et al. (17) showed that individuals with wheat sensitivity display highly increased serum levels of intestinal fatty acid-binding protein, in conjunction with elevated levels of soluble CD14, lipopolysacchide (LPS)-binding protein, and antibodies to bacterial LPS and flagellin, all of which declined in response to the elimination of gluten-containing food (i.e., wheat, rye, and barley) from diet. The study provided clear evidence for an immunological mechanism underlying NCGS distinct from CD, whereby intestinal epithelial cell damage leads to microbial tranalsocation and extensive systemic immune activation. The study also provided a panel of objective serologic markers with diagnostic potential. Because circulating microbial LPS is known to bind directly to TLR4 on the luminal surface of brain blood vessels with increased local cytokine secretion (18), the findings may also explain some of the neuropsychiatric symptoms related to NCGS.

Genetic of NCGS

Up to half of NCGS patients may have genes coding for the HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8 molecules. HLA DQ2/DQ8 are present in 95% of all celiac patients and their absence can be used to rule out the diagnosis of CD in 95% of all cases (8). HLA DQ2-DQ8 are present in 30% of Healthy subjects. As such, it does not appear to be a significant association between the celiac disease HLA markers and NCGS.

Clinical Diagnosis of NCGS

Volta et al (19), in a multi-center Italian study of 486 patients responsive to a gluten-free diet (GFD), reported that most patients showed associated gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms. Bloating and abdominal Pain were the most important gastrointestinal symptoms (> 80%), whereas more than 50% of these patients reported diarrhea, 27% alternating bowel habits and 24% constipation (19). Other symptoms included epigastric pain, nausea, aerophagia, gastro-esophageal reflux disease and aphtous stomatitis. Tiredness, lack of well-being, neuropsychiatric symptoms as headache, anxiety, “foggy mind”, arm/leg numbness, depression, muscle or joint pain, weight loss, dermatitis, skin rash featured prominently among the extraintestinal symptoms of NCGS. There was an “overlap” between irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and NCGS with regard to symptoms (20). In patients with clinical characteristics compatible with Rome III criteria for IBS, particularly in those with diarrhea, NCGS is diagnosed in a high percentage of cases; (21). Shahbazkhani et al. (22) found a large percentage of IBS patients (83%) to be gluten sensitive in their trial (72 patients). Also in patients with allergic disorders, a high prevalence of NCGS was reported by Massari et al. (77 NCGS/262 allergic patients) (23). The reported prevalence of NCGS, at this moment, varies between 0.6 and 6% (1). Anti-gliadinliadin antibodies may be present in about 50% of patients with suspected NCGS (24). Based on Salerno expert criteria, the patient may have 1 to 3 main symptoms that are quantitatively assessed using a Numerical Rating Scale with a score ranging from 1 to 10 (21, 25). The double blind placebo controlled gluten challenge (8 g/day) includes a one-week challenge followed by a one-week wash-out of strict GFD and a new crossover to the second one-week challenge (25). The vehicle for the challenge should contain cooked, homogeneously distributed gluten (25).

A variation of 30% in 1 to 3 main symptoms between the gluten and placebo may discriminate positive from negative results (25). The Salerno Criteria (25) is the most reliable tool so far for diagnosing NCGS. However, it has a limited applicability in clinical practice outside the clinical trials. Most of the clinicians use an open gluten challenge fashion to ascertain the diagnosis of NCGS. An open gluten challenge is the most practical way forward, despite reduced diagnostic accuracy. Further study would be needed to introduce a pragmatic and more practical policy to help clinician to diagnose NCGS in absence of more sensitive and specific biomarkers.

The clinical observation in Salerno expert criteria includes an administration of a modified version of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) based on reviews of gastrointestinal symptoms and clinical symptoms almost largely used to evaluate common symptoms of Gastrointestinal Disorders (26). The patient identifies 1 to 3 main symptoms that may be evaluated using a Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) with a score ranging from 1 (mild) to 10 (severe). The instruction includes item evaluating also extra intestinal symptoms. Elli et al. (27) performed a multicenter double-blind-placebo controlled trial with crossover enrolling 134 patients (17 males and 117 females); 98 of these patients underwent a gluten challenge after 3 weeks long GFD and 28 of these, all females, reported a symptomatic relapse and deterioration of quality of life.

Duodenal Histology of NCGS

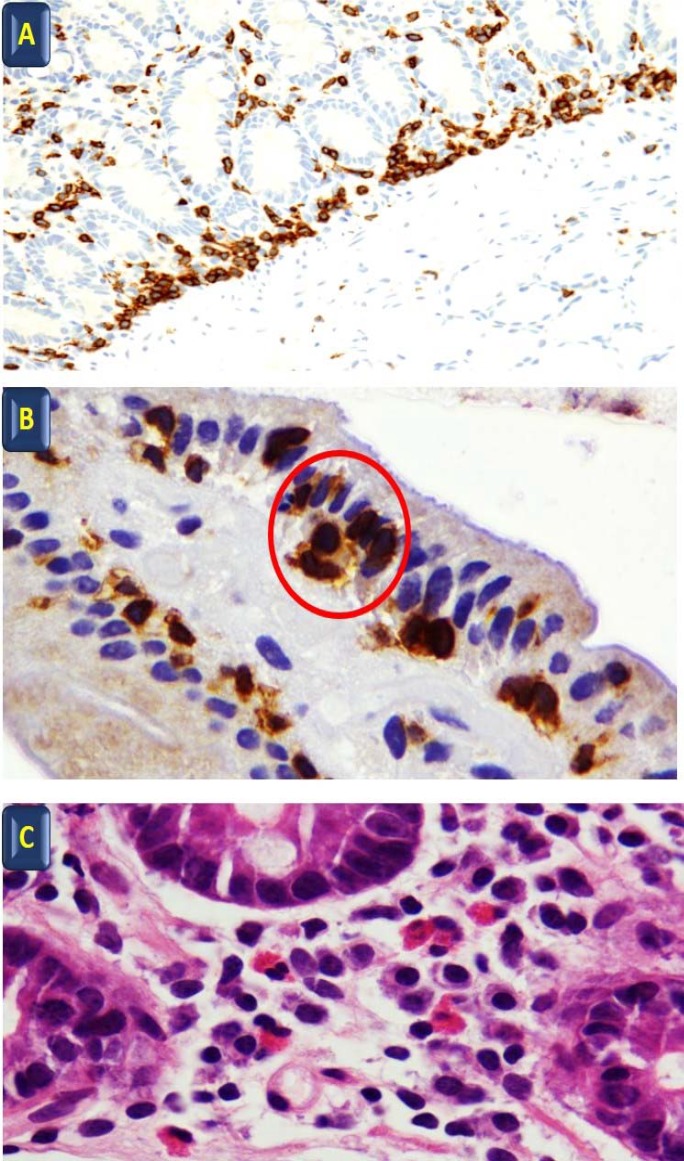

The histologic characteristics of NCGS are still under investigation, ranging from reports of apparently normal histology to slight increase of T lymphocytes in the superficial epithelium of normal villi (28). In a recent editorial, Talley and colleagues (29) reported the presence of high intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) and increased duodenal eosinophils in some cases of NCGS, but underlined the overlap of these findings in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (29). Villanacci V et al. (30) have reported that patients with NCGS might have a normal number of T lymphocytes but a peculiar disposition of this cells in small “cluster” of ¾ elements in the superficial epithelium and a linear disposition in the deeper part of the mucosa together with an increased number of eosinophils in lamina propria (Villanacci V unpublished data). A slight increase of gamma delta T cell receptors in NCGS has also been reported by some studies (1). Brottveit et al. (31) studied the initial mucosal immunologic events in CD and NCGS patients before and after a gluten challenge, showed an increase of interferon gamma and Heat Shock Protein 27 levels after gluten challenge and confirmed the presence of a higher density of intraepithelial lymphocytes. Bucci et al. (32) did not found any gliadin related immunologic alteration in the duodenal mucosa of NCGS patients. In NCGS patients, basophil activation was reported to be positive in 66% of patients responding to wheat blind challenge and to be associated with duodenal intraepithelial lymphocytosis and eosinophilic infiltration of the duodenum and the colon (33). Sub-microscopic changes or duodenal Intraepithelial Lymphocytosis may be present in about 50% of NCGS cases under definition of Microscopic Enteritis (34).

Open Questions

The lack of standardized biomarkers remains an important challenge in the diagnosis of NCGS. The clinical symptoms are not specific and they may be confused with other conditions like IBS (1). The current algorithm recommends the exclusion of CD and wheat allergy and symptomatic improvement on GFD (25).

Principal remaining questions pertain to what is triggering NCGS and why some people suddenly become gluten intolerant. The factors implicated in the occurrence of NCGS remain largely unknown and it is unclear who is susceptible to this condition. It has been suggested that dysbiosis following a gastroenteritis might count as a risk factor for NCGS (35).

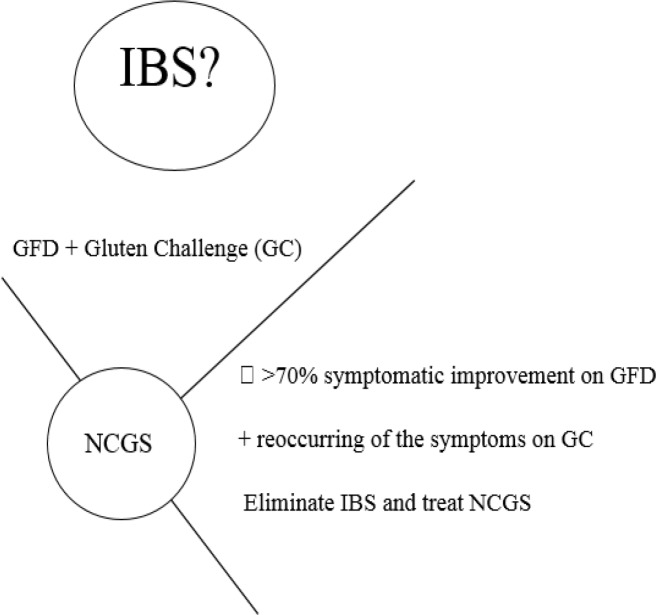

The future research agenda should explore the genetic background, histological characteristic, susceptibility and risk factors for NCGS in addition to developing reliable biomarkers. It is essential to separate NCGS from IBS as IBS is a non-specific condition and IBS therapies not only are not effective in NCGS, but also these medications and their side effect may impair the quality of life of NCGS patients and adversely drain the healthcare resources (36-42). See table 1 and figures 1, 2.

Table 1.

Gluten free diet effect assessed by double-blind placebo-controlled oral gluten challenge trials in IBS patients (authors and reference number first column

| Authors | No of IBS | Study design | Am Gluten | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper et al. 1980 (7) | 6 | DBPC | (20 g/d) | Sig Improv |

| Biesiekierski et al. 2011 (41) | 34 | DBPC | (16 g/d) | Sig Improv |

| Carroccio et al. 2012 (34) | 276 | DBPC | (13 g/d) | Sig Improv |

| Shahbazkhani et al (22) | 72 | DBPC | 52g/day | Sig Improv |

| Di Sabatino et al. 2015 (38) | 61 | DBPC | (4.375 g/d) | Sig Improv |

| Zanini et al. 2015 (37) | 35 | DBPC | (10g/d) | Sig Improv |

| Elli et al. 2016 (27) | 98 | DBPC | (5.6 g/d) | Sig Improv |

| Barmeyer et al 2016 (40) | 35 | Observational | 90% | |

| Zanwar et al (39) | 60 | DBPC |

Abbreviations: Sig Improvement: significant improvement, DBPC: double blind placebo controlled; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome

Figure 1.

A: Linear disposition of T lymphocytes at the base of the mucosa CD3 immunohistochenistry 40x; B: Cluster of ¾ lymphocytes in the superficial epithelium (red circle) CD3 immunohistochemistry 100x; C: Eosinophils in lamina propria H&E 100 x

Figure 2.

Studies listed in table 1 suggest over 70% of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) respond to gluten free diet (GFD) with reoccurring the symptoms on gluten challenge (GC). For targeted and effective treatment it is essential to recognise and differentiate non-coeliac gluten sensitivity from IBS

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Elli L, Roncoroni L, Bardella MT. Non Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: Time for sifting the grain. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8221–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Glija OH, Hausken T. The relation between Celiac Disease, Non Celiac Gluten Sensitivity and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nutr J. 2015;14:92. doi: 10.1186/s12937-015-0080-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Junker Y, Zessig S, Kim SI, Barisani D, Wesser H, Leffler DA. Wheat Amylase Trypsin Inhibitor drive intestinal inflammation via activation of toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2395–401. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muir JG, Gibson PR. The Low FODMAP Diet for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Other Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9:450–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroccio A, Mansueto P, D’Alcamo A, Iacono G. Non Celiac Wheat Sensitivity as an Allergic condition: personal experience and narrative review. Am J Gastroenterology. 2013;108:1845–52. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis A, Linaker BD. Non Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Lancet. 1978;1:1386–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper BT, Holmes GK, Ferguson R, Thompson RA, Allan RN, Coole MT. Gluten-sensitive diarrhea without evidence of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology. 1980:7980–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, Dolisenk J, Green PH, Hadjivassiliou M. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shevry PR, Howlesfod M, Picoren V, Lampi AM, Gebruer I, Borcs D, et al. Natural variation in grain composition of wheat and related cereals. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:8295–303. doi: 10.1021/jf3054092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. American J Gastroenterology. 2013;108:728–36. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elli L, Dolfini E, Bardella MT. Gliadin cytotoxicity and in vitro cell cultures. Toxicol Lett. 2003;146:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roncoroni L, Elli L, Bardella MT, Perrucci G, Ciulla M, Lombardo V. Extracellular matrix proteins and displacement of cultired fibroblasts from duodenal biopsies in Celiac patients and controls. J Transl Med. 2013;11:91. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolfini E, Elli L, Roncoroni L, Costa B, Colleoni MP, Lo russo V. Damaging effects of Gliadin on three- dimensional cell culture model. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5973–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i38.5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palova-Jelinkova L, Danova K, Drasarova H, Dvorak M, Funda DP, Fundova P. Pepsin digest of wheat gliadin fraction increases production of IL-1beta via TLR4/MyD88/TRIF/MAPK/NF-kB signaling pathway and anNLRP3 inflammasome activation. PL0S One. 2013;8:e62426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo Surdo G, Giorgio F, Piscitelli D, Montenegro L, Covelli C, Fiore MG. May the assessment of baseline mucosal molecular pattern predict the development of Gluten related disorders among Microscopic Enteritis? World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8017–25. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i35.8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolfini E, Roncoroni L, Elli L, Fumagalli C, Colombo R, Ramponi S. Cytoskeleton reorganization and ulastructural damage induced by gliadin in a three dimensional in vitro model. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7597–601. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i48.7597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uhde M, Ajamian M, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Indart A. Intestinal Cell Damage and Systemic Immune activation in individuals reporting sensitivity to Wheat in the absence of coeliac disease. GUT. 2016;65:1930–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z, Jalabi W, Shpargel KB, Farabaugh KT, Dutta R, Yin X, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and neuroprotection against experimental brain injury is independent of hematogenous TLR4. J Neurosci. 2012;32:11706–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volta U, Bardella MT, Calabro’ A, Troncone R, Corazza GR. An Italian prospective multicenter survey in patients suspected of having Non Celiac Gluten Sensitività. BMC Med. 2014;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esvaran S, Goel A, Cley WD. What role does wheat paly in the symptoms of Irritable Bowel Sindrome? Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2013;9:95–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, Murray JA, Marietta E, O'Neill J, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:903–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shahbazkhani B, Sadeghi A, Malekzadeh R, Khatavi F, Etemadi M, Kalantri E, et al. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Has Narrowed the Spectrum of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2015;7:4542–54. doi: 10.3390/nu7064542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massari S, Liso M, De Santis L, Mazzei F, Carlone A, Mauro S. Occurence of Non Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in patients with Allergic Disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;155:390–4. doi: 10.1159/000321196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volta U, Tovoli F, Cicala R, Parisi C, Fabbri A, Piscaglia M. Serological tests in Gluten Sensitività (Non celiac gluten intolerance) J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:680–5. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182372541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Carroccio A, Castillejo G. Diagnosis of Non Celiac Gluten Sensitività (NCGS): The Salerno Experts Criteria. Nutrients. 2015;7:4966–77. doi: 10.3390/nu7064966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulich KR, Madisch A, Pacini F, Piqué JM, Regula J, Van Rensburg CJ, et al. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in dyspepsia: a six-country study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elli L, Tomba C, Branchi F, Roncoroni L, Lombardo V, Bardella MT. Evidence for the presence of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in Patients with Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Results from a Multicenter Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Gluten Challenge. Nutrients. 2016;8:84. doi: 10.3390/nu8020084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsh N, Villanacci V, Srivastava A. Histology of gluten related disorders. Gastroenterology Hepatology Bed Bench. 2015;8:171–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tally NJ, Walker NM. Celiac Disease and Non Celiac Gluten or Wheat Sensitivity: The Risks and Benefits of diagnosis. JAMA Inern Med. 2917;177:615–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villanacci V, Lanzini A, Lanzarotto F, Ricci C. Observations on the paper of Carroccio et al "non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity". Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:619–20. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brottveit M, Beitnes AC, Tollefser S, Brade JE, Jahnsen FL, Joharsen FE. Mucosal cytokine response after short term gluten challenge in Celiac Disease and Non Celiac Gluten Sensitività. Am.J. Gastroenterol. 2013;108:842–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bucci C, Zingone F, Russo C, Morra I, Tortora R, Pogna N, et al. Gliadin does not induce mucosal inflammation or basophil activation in patients with Non Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:1294–99e. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroccio A, Mansueto P, Iacono G, Soresi M, D’Alcamo A, Cavataio F. Non Celiac Wheat Sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo controlled challentge exploring a new entità. Am.J.Gastroenterology. 2012;107:1989–06. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rostami K, Aidulaimi D, Holmes G, Johnson MW, Robert M, Srivastava A, Microscopic Enteritis. Bucharest Consensus. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2593–604. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rostami K, Rostami-Nejad M, Al Dulaimi D. Post gastroenteritis gluten intolerance. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2015;8:66–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soubieres A, Wilson P, Poullis A, Wilkins J, France M. Burden of irritable bowel syndrome in an increasingly cost-aware National Health Service. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2015;6:46–51. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2014-100542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zanini B, Bacche R, Ferrarese A, Ricci C, Panzarotto F, Ma rullo M. Randomized Clinical Study: Gluten challenge induces symptom recurrence in only a minority of patients who meet clinical criteria for non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:868–76. doi: 10.1111/apt.13372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR. True Nonceliac Gluten Sensitività in Real Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:165–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zamwar VG, Pawar SV, Gambhire PA, Jain SS, Su rude RG, Shah VB. Symptomatic improvement with gluten restriction in irritable bowel sindrome: a prospective, randomized, double blinded placebo controlled trial. Intest Res. 2016;14:343–50. doi: 10.5217/ir.2016.14.4.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barmeyer C, Schumman M, Mever T, Zeimak C, Zuberber T, Segmurd B. Long-term response to gluten free diet as evidence for non celiac wheat sensitivity in one third of patients with diarrhea-dominant and mixed-type irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:26–38. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2663-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biesiekierski JR, Peter SL, Newnhan ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effect of gluten in patients with self-reported Non Celiac Gluten Sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable poorly absorbed, short chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:320–8e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meijer CR, Shamir R, Mearin ML. Coeliac disease and non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:429–32. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]