Vibrio cholerae is a prominent human pathogen that is currently causing a pandemic outbreak in Haiti, Yemen, and Ethiopia. The second messenger molecule cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) mediates the transitions in V. cholerae between a sessile biofilm-forming state and a motile lifestyle, both of which are important during V. cholerae environmental persistence and human infections. Here, we report that in V. cholerae c-di-GMP also controls DNA repair. We elucidate the regulatory pathway by which c-di-GMP increases DNA repair, allowing this bacterium to tolerate high concentrations of mutagens at high intracellular levels of c-di-GMP. Our work suggests that DNA repair and biofilm formation may be linked in V. cholerae.

KEYWORDS: DNA repair, c-di-GMP, VpsT, Vibrio cholerae, biofilm, cyclic di-GMP

ABSTRACT

In Vibrio cholerae, high intracellular cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) concentration are associated with a biofilm lifestyle, while low intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations are associated with a motile lifestyle. c-di-GMP also regulates other behaviors, such as acetoin production and type II secretion; however, the extent of phenotypes regulated by c-di-GMP is not fully understood. We recently determined that the sequence upstream of the DNA repair gene encoding 3-methyladenine glycosylase (tag) was positively induced by c-di-GMP, suggesting that this signaling system might impact DNA repair pathways. We identified a DNA region upstream of tag that is required for transcriptional induction by c-di-GMP. We further showed that c-di-GMP induction of tag expression was dependent on the c-di-GMP-dependent biofilm regulators VpsT and VpsR. In vitro binding assays and heterologous host expression studies show that VpsT acts directly at the tag promoter in response to c-di-GMP to induce tag expression. Last, we determined that strains with high c-di-GMP concentrations are more tolerant of the DNA-damaging agent methyl methanesulfonate. Our results indicate that the regulatory network of c-di-GMP in V. cholerae extends beyond biofilm formation and motility to regulate DNA repair through the VpsR/VpsT c-di-GMP-dependent cascade.

IMPORTANCE Vibrio cholerae is a prominent human pathogen that is currently causing a pandemic outbreak in Haiti, Yemen, and Ethiopia. The second messenger molecule cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) mediates the transitions in V. cholerae between a sessile biofilm-forming state and a motile lifestyle, both of which are important during V. cholerae environmental persistence and human infections. Here, we report that in V. cholerae c-di-GMP also controls DNA repair. We elucidate the regulatory pathway by which c-di-GMP increases DNA repair, allowing this bacterium to tolerate high concentrations of mutagens at high intracellular levels of c-di-GMP. Our work suggests that DNA repair and biofilm formation may be linked in V. cholerae.

INTRODUCTION

Many bacterial species use the second messenger signaling molecule cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) to control cellular behavior. Since its discovery in 1987, research in c-di-GMP signaling has uncovered a largely invariable paradigm, that high intracellular c-di-GMP stimulates an adherent static lifestyle known as a biofilm, while decreasing c-di-GMP results in a motile lifestyle (1). Two classes of enzymes are responsible for changes in intracellular c-di-GMP. Diguanylate cyclase enzymes (DGCs), containing GGDEF active-site motifs, catalyze the cyclization of two GTP molecules to form c-di-GMP. c-di-GMP is degraded into pGpG or 2 GMP molecules by phosphodiesterase enzymes (PDEs) containing EAL or HD-GYP active-site motifs, respectively (1–3). pGpG is further degraded to GMP by the Orn nuclease (4, 5). Furthermore, the enzymatic activities of DGCs and PDEs are thought to be controlled by environmental cues (3). Thus, c-di-GMP functions as one of the major global regulatory pathways that allows bacteria to respond and adapt to their environment.

c-di-GMP additionally regulates bacterial behaviors beyond biofilm formation and motility. For example, Streptomyces species undergo a morphological transition between vegetative and aerial mycelial growth that is controlled by the c-di-GMP-dependent transcription factor BldD (6). In Caulobacter crescentus, certain DGC and PDE enzymes localize to different cellular regions to control the transition from a swarmer to stalked cell phenotype (7, 8). c-di-GMP also regulates virulence and the type II secretion apparatus in V. cholerae (9, 10). However, this list of bacterial phenotypes controlled by c-di-GMP has not been fully elucidated. Further, whether these phenotypes act in a coordinated manner to promote adaptation to a sessile or motile lifestyle is not clear. Here, we report that DNA repair is a new phenotype controlled by c-di-GMP in V. cholerae.

The human pathogen V. cholerae causes the diarrheal disease cholera, ultimately resulting in death by dehydration if left untreated. Currently, the 7th V. cholerae pandemic caused by the El Tor biotype is responsible for numerous infections worldwide, including recent outbreaks in Haiti, Ethiopia, and Yemen (11–13). While infamously known for its epidemics throughout human history, V. cholerae resides harmlessly between disease outbreaks in marine environments, where it is thought to associate with chitinous surfaces as biofilms (14–16). Biofilm formation and motility also contribute to V. cholerae infections. Growth in biofilms induces a hyperinfectious state, while motility is necessary for colonization of the proximal small intestine (17–19). Thus, the transition between biofilm formation and motility is considered a key aspect of the pathogenesis of this bacterium.

The mechanism for c-di-GMP-dependent biofilm formation in V. cholerae has been well studied. In response to specific environmental cues, such as bile acids (20), intracellular c-di-GMP increases. c-di-GMP binds to and activates the c-di-GMP-dependent transcription factor VpsR (27). Activated VpsR then induces the expression of another c-di-GMP-dependent transcription factor, VpsT, which is also directly activated by c-di-GMP binding (21, 22). At high c-di-GMP concentrations, these two transcription factors induce the expression of genes needed for biofilm formation, in particular, the Vibrio polysaccharide (VPS) operons and the gene cluster rbmBCDEF encoding biofilm matrix proteins (23, 24). Concurrently, high c-di-GMP concentrations directly decrease the expression of the flagellar biosynthesis gene cluster through inhibition of the transcription factor FlrA (25). Thus, high c-di-GMP concentrations increase the expression of genes involved in biofilm formation and simultaneously decrease the expression of genes involved in flagellar motility. Moreover, the production of VPS itself inhibits motility (25).

In response to c-di-GMP, VpsT and VpsR regulate the gene expression of other processes in addition to biofilm formation. aphA, a gene involved in virulence regulation and acetoin biosynthesis, is induced by VpsR and c-di-GMP, but only acetoin utilization is significantly impacted (26, 27). VpsR, activated by c-di-GMP, induces transcription of the eps operon encoding proteins necessary for production of the type II secretion system. While not impacting protein secretion, the induction of eps leads to the production of a surface pseudopilus (10). VpsR and c-di-GMP induce transcription of the transcription factor gene tfoY, which impacts motility and type VI secretion (28, 29). In addition, transcriptomic analyses indicate that c-di-GMP signaling and VpsT regulate the expression of various genes; however, the physiological effect of these global gene responses is not well characterized (15, 22).

In the marine environment and human host, V. cholerae likely incurs DNA damage that must be repaired to maintain genome integrity and fitness. Indeed, mutations in key genes of the base excision repair (BER) pathway decrease infant mouse colonization and increase sensitivity to DNA-damaging chemicals (30). DNA glycosylases stimulate the repair of DNA damage through the BER pathway by specifically recognizing and removing lesioned bases (31). While the mechanistic details of the BER pathway have been well studied, only a few regulatory pathways controlling BER gene expression in bacteria have been identified (31–33). Here, we report our findings that increased c-di-GMP induces transcription of the DNA glycosylase Tag (3-methyladenine glycosylase) gene in V. cholerae. We demonstrate that c-di-GMP positively regulates tag expression through the c-di-GMP-dependent transcription factors VpsT and VpsR but not FlrA, indicating that tag may play a role in homeostasis within a biofilm or during biofilm formation. We further demonstrate that VpsT directly regulates the expression of tag in a c-di-GMP-dependent manner. Last, we show that cells with high intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations have increased tolerance to the DNA-methylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS).

RESULTS

c-di-GMP induces expression of tag.

Bacteria use c-di-GMP to modulate disparate aspects of cell physiology ranging from biofilm formation to cell cycle progression. While some of these phenotypes have been characterized in V. cholerae, we hypothesized that there were more remaining to be discovered (34). Thus, we screened a library of transcriptional fusion reporters for promoters regulated by c-di-GMP, as previously reported (27). Of the seven promoters identified, one mapped upstream of the gene VC1672 (referred to as 6:C9 in our previous publication [27]), encoding the DNA glycosylase Tag. In Escherichia coli, Tag initiates the BER pathway by recognizing and removing adenines and guanines methylated at the 3-position in DNA (35, 36).

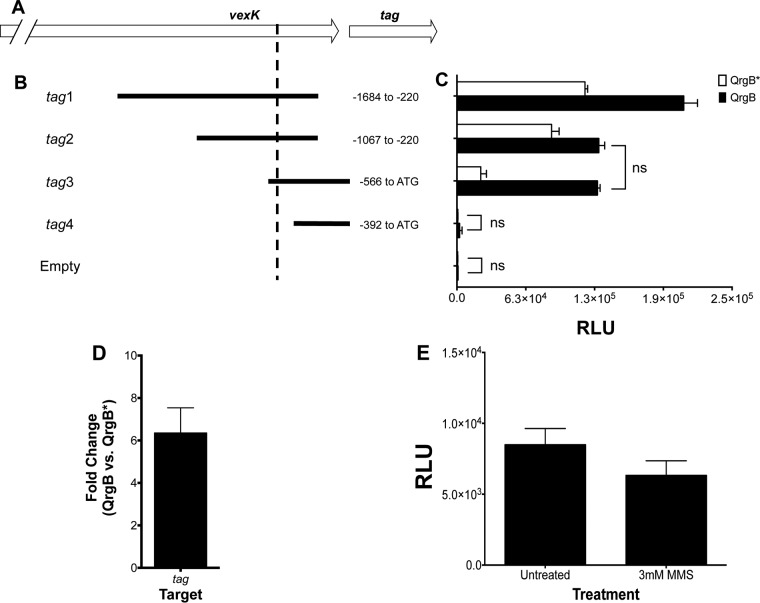

The original region of DNA isolated from the promoter screen, which we refer to as tag1 (Fig. 1A), was ∼1.4 kb long and extended to the upstream gene VC1673, which encodes the AcrB family transporter VexK. Based on the orientation of this DNA sequence, transcription could proceed into tag. To determine the region necessary for c-di-GMP-mediated reporter activity, we modified the lengths of the 5′ and 3′ ends of tag1 and measured promoter activity under different c-di-GMP levels (Fig. 1B and C). To increase intracellular c-di-GMP levels, we overproduced the Vibrio harveyi DGC QrgB from a plasmid. We found that this system generates c-di-GMP at concentrations that are similar to those at growth at low cell density, a growth phase of V. cholerae that naturally has high intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations due to quorum sensing regulation (29, 37). As a negative control, the active-site mutant QrgB*, which does not change c-di-GMP levels, was similarly induced. Induction of QrgB significantly increased the promoter activities of regions tag1 through tag3 relative to QrgB* (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the DNA sequence from −1067 to −566 in both tag1 and tag2 increases basal expression at low c-di-GMP concentrations relative to tag3 (Fig. 1C, white bars). tag3, which contains the sequence from −566 to the ATG start codon of tag, exhibited the greatest fold induction by c-di-GMP. Importantly, this reporter also demonstrates that transcription from these upstream regions proceeds into the tag open reading frame. The promoter activity of the DNA sequence immediately upstream of tag (tag4) was similar to the activity of the promoterless vector control, indicating that this region lacks an active promoter under our conditions (Fig. 1C). 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) experiments identified the transcriptional start site at bp −502 relative to the ATG start codon (Fig. 1A and B, dashed line). To confirm that tag was induced by c-di-GMP, we quantified tag mRNA by quantitative real-time PCR and observed an ∼6-fold increase when QrgB is induced relative to QrgB* (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Promoter characterization of tag. (A and B) Diagrams depicting sizes and locations of promoter truncations relative to the ATG start codon of tag utilized for luciferase reporter assays. The dashed line indicates the transcriptional start site (A, 502 bp upstream of ATG start codon). (C) Luciferase reporter assay of the promoter truncations in panel B. White bars are strains overproducing QrgB*, while black bars are strains overproducing QrgB. The results are averages of the results from three independent experiments with 3 technical replicates each. Error bars indicate standard deviations. All comparisons are considered significant, except those with brackets and ns (nonsignificant; P > 0.05), as determined by a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison test. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of tag mRNA expression levels. The data are average fold changes between QrgB- and QrgB*-expressing strains from 3 biological replicates, and the error bar is the standard deviation. (E) The parent strain (ΔvpsL mutant) harboring tag3 (luciferase reporter with tag promoter) was grown in the absence (left bar) or presence (right bar) of 3 mM MMS. The data are the averages of the results from at least two experiments, and the error bars indicate standard deviations.

Cellular stressors often act as signals to induce gene expression of the pathways that repair their damage, such as double-stranded breaks in DNA and the SOS response in E. coli (38). We were interested in whether tag expression was also modulated by the addition of the methylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), as this chemical induces damage that would be repaired by Tag. Therefore, we measured tag3 expression in the presence and absence of 3 mM MMS. However, we observed no change in tag expression with the addition of MMS (Fig. 1E).

Together, these data indicate that c-di-GMP-regulated expression of tag is driven by a promoter 502 bp upstream of the ATG start codon and that the sequence from bp −566 to −392 is important for expression. Further, regions in the 5′ direction of this promoter sequence increase basal expression. For the remainder of the experiments, the tag3 reporter construct was used to assess tag transcription.

VpsT and VpsR are necessary for tag expression.

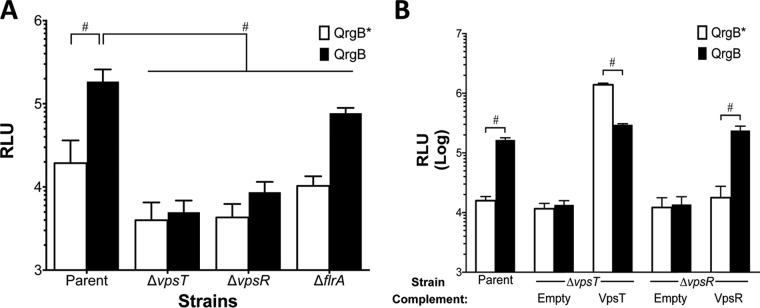

c-di-GMP stimulates biofilm production by activating the transcription factors VpsT and VpsR (22, 27). It also inhibits motility by antiactivation of the master regulator of flagellar biosynthesis, FlrA (25). Therefore, we reasoned that c-di-GMP induction of tag could depend on either of these three c-di-GMP-dependent transcription factors. To test this hypothesis, we conjugated the tag reporter plasmid into V. cholerae strains lacking either vpsT, vpsR, or flrA, and we assayed tag promoter activity at different intracellular c-di-GMP levels. In the parent and ΔflrA isogenic mutant, tag expression increased approximately 10-fold with QrgB overproduction compared to the QrgB* control. tag expression with QrgB overproduction was 2.4-fold lower in the ΔflrA mutant strain than in the wild type (WT), but significant induction was observed (Fig. 2A). However, in the ΔvpsT and ΔvpsR mutant backgrounds, QrgB overproduction had no effect on tag expression compared to the QrgB* control, indicating that VpsT and VpsR are necessary for tag expression (Fig. 2A). We then complemented the ΔvpsT and ΔvpsR mutants by overexpressing VpsT and VpsR, respectively, from a plasmid. Complementing the ΔvpsR mutant strain with VpsR restored c-di-GMP-mediated tag expression to a level similar to that of the parent strain (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, complementation of the ΔvpsT mutant by overexpressing VpsT resulted in increased tag expression regardless of QrgB* or QrgB expression (Fig. 2B). We did observe a 2-fold decrease in tag expression when VpsT and QrgB were overexpressed compared to VpsT and QrgB*; however, this difference was relatively small compared with the 100-fold induction caused by VpsT in a comparison with the empty vector control, and thus, we do not consider it to be biologically meaningful (Fig. 2B). This experiment suggests that high concentrations of VpsT do not require elevated c-di-GMP to activate tag. Either VpsT can function in a c-di-GMP-independent manner or the basal concentration of c-di-GMP in V. cholerae under these conditions is high enough to activate the increased concentrations of VpsT. These results demonstrate that VpsT and VpsR are necessary for c-di-GMP-mediated tag expression.

FIG 2.

VpsT and VpsR are required for tag induction by c-di-GMP. (A) Parent strain (ΔvpsL mutant) and isogenic knockouts (ΔvpsT, ΔvpsR, and ΔflrA mutants) harboring either QrgB* or QrgB and the tag3 luciferase reporter construct were grown in the presence of 100 μM IPTG to induce protein expression. The data are the averages from the results from at least three experiments, and the error bars indicate standard deviations. #, statistical significance (P < 0.05) between strains, as determined by a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison test. (B) tag expression in the ΔvpsT and ΔvpsR mutant backgrounds with vectors harboring IPTG-inducible VpsT and VpsR, respectively. All strains contain tag3 and either QrgB* or QrgB, as well as an expression vector for VpsT or VpsR or an empty vector negative control. Data represent averages of the results from at least three different experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. #, statistical significance (P < 0.05) comparing QrgB* and QrgB for that given strain/condition, as determined by a two-tailed Student t test.

VpsT activates tag transcription in E. coli and binds to the tag promoter in vitro.

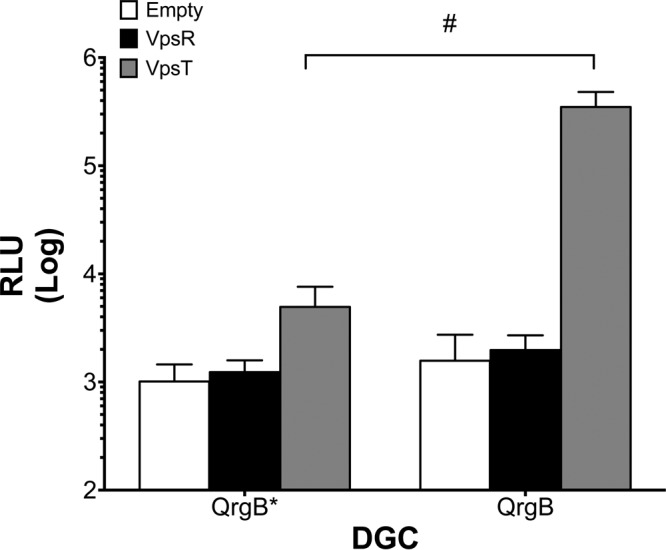

Since vpsT expression is activated by vpsR in a c-di-GMP-dependent manner (39), and vpsT was required for tag expression (Fig. 2A and B), we hypothesized that VpsT was the primary c-di-GMP-dependent activator of tag. To test this hypothesis, we measured tag expression in a heterologous host, E. coli. We reasoned that this in vivo system would allow us to isolate the impact of VpsT and VpsR on tag expression without pleiotropic effects due to the complex regulatory relationship between VpsT and VpsR (40). tag expression increased approximately 200-fold relative to the empty vector control when VpsT was coexpressed with QrgB to generate high c-di-GMP concentrations, while no induction was observed with VpsR coexpressed with QrgB (Fig. 3). tag expression was not induced when the inactive QrgB* was coexpressed with VpsT or VpsR, indicating that c-di-GMP is required for this induction (Fig. 3). These data indicate that VpsT, but not VpsR, is sufficient to regulate tag expression in a c-di-GMP-dependent manner in E. coli and that no other V. cholerae-specific proteins are required for this induction.

FIG 3.

VpsT and c-di-GMP induce tag expression in E. coli. A three-plasmid system was established wherein the tag reporter, either QrgB* or QrgB, and either VpsT, VpsR, or empty vector were transformed into DH10b E. coli. IPTG (100 μM) was added at subculture, and luciferase activity was measured at mid-exponential phase. The data are averages of the results from three experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. #, statistical significance (P < 0.05) comparing QrgB* and QrgB for each condition, as determined by a two-tailed Student t test.

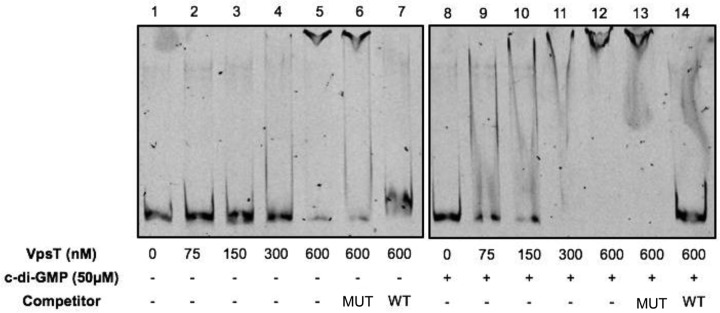

To determine if VpsT bound to the tag promoter in vitro, we carried out electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). We generated 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein (5′-FAM)-labeled probes containing the tag3 region (Fig. 1B, FAM-tag3) and incubated them with purified histidine-tagged VpsT for in vitro binding. VpsT partially bound to FAM-tag3 at a concentration of 300 nM and almost completely shifted the probe at 600 nM (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 7). c-di-GMP enhances the in vitro DNA binding ability of VpsT at promoters of genes involved in biofilm formation (22). Thus, to determine if c-di-GMP enhanced DNA binding at the tag promoter, we included 50 μM c-di-GMP in the binding reaction mixture (Fig. 4, lanes 8 to 14). Partial binding occurred at 75 nM VpsT with near-complete shifting observed at 300 nM VpsT, indicating that c-di-GMP enhances VpsT DNA binding at the tag promoter in vitro in a manner similar to the vpsL promoter (41, 42). The U-shaped bands that we observed when c-di-GMP was added to the binding reaction mixture (Fig. 4, lanes 9 to 11) are likely the result of the dissociation between c-di-GMP and VpsT during electrophoresis, which would result in VpsT dissociating from the labeled probe, as previously described by Ayala et al. (42).

FIG 4.

c-di-GMP enhances VpsT affinity at the tag promoter in vitro. Lanes 1 to 7, increasing concentrations of purified VpsT-HIS were incubated with the fluorescently labeled tag promoter (FAM-tag3). When indicated, the mutant (MUT) or wild-type (WT) VpsT binding site competitor was added to the reaction at 100× excess relative to the probe concentration. Lanes 8 to 14, the same as lanes 1 to 7, except that 50 μM c-di-GMP was added to the reaction mixtures.

Recently, a 20- to 22-bp VpsT binding consensus site containing a palindromic sequence was described (41). We reasoned if the interaction between VpsT and the tag promoter was specific, the addition of a 22-bp oligonucleotide containing the VpsT binding site to the binding reaction (WT competitor) would compete away interactions between VpsT and FAM-tag3. Conversely, adding an oligonucleotide with a disrupted palindromic region (mutant [MUT] competitor) would have no effect on interactions between VpsT and FAM-tag3. Indeed, the addition of the WT competitor to the binding reaction without c-di-GMP resulted in a nearly complete reduction in the shifted probe, while the addition of the mutant competitor did not compete away VpsT binding from FAM-tag3 (Fig. 4, lanes 6 and 7). In the presence of 50 μM c-di-GMP, the WT competitor completely competed away binding of VpsT, while the mutant competitor had no effect (Fig. 4, lanes 13 and 14). These results indicate that VpsT specifically binds to the tag3 region, and c-di-GMP increases the affinity of VpsT binding. Taken together, these data suggest that VpsT directly regulates tag expression and that VpsR regulates tag expression indirectly through the induction of VpsT (41).

c-di-GMP increases tolerance of the alkylating agent MMS.

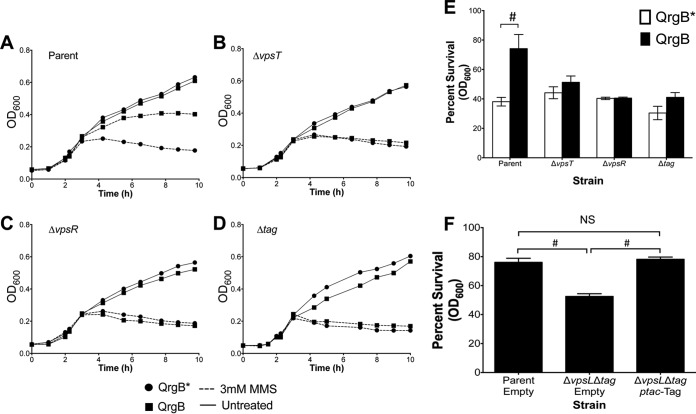

Tag is an enzyme in the BER pathway that recognizes and removes methylated adenines (3meA) and guanines (3meG) at the N3 position (35). 3meA is a lethal nonmutagenic lesion that blocks DNA replication, whereas 3meG is innocuous (36). Since c-di-GMP induces tag expression, we hypothesized that cells with high intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations would be more tolerant of MMS treatment, which generates 3meA, than cells with basal intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations. To test this, QrgB or QrgB* was induced for 2 h in the parent background before treatment with 3 mM MMS, and growth was quantified every hour for 10 h by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The parent strain used in these experiments is a V. cholerae ΔvpsL mutant that is incapable of forming biofilms; thus, biofilm formation itself cannot be induced by c-di-GMP and is not responsible for the observed differences.

V. cholerae strains expressing QrgB* or QrgB displayed similar growth curves for all strains examined in the absence of MMS treatment (Fig. 5A to D, solid lines), indicating that c-di-GMP has no deleterious effects on growth under these conditions. In the parent strain, the induction of c-di-GMP led to significantly more growth in the presence of MMS (Fig. 5A, squares). Quantification of optical density after 6 h of treatment revealed that increased c-di-GMP led to an approximate 2-fold increase in survival compared to the QrgB* control (Fig. 5E).

FIG 5.

High c-di-GMP increases tolerance to the methylating agent MMS. (A to D) Strains were cultured 1:1,000 and grown in the presence of 100 μM IPTG to overproduce QrgB* and QrgB. After 2 h, cells were left untreated (solid lines) or treated with 3 mM MMS (dashed lines), and the OD600 was measured every hour for 10 h. Error bars, which are obscured by symbols, are standard deviations. (E) Quantification of survival (percentage of treated OD divided by untreated OD) for a given strain after 6 h of treatment. (F) Complementation of the ΔvpsL Δtag mutant strain by expressing Tag in trans. Error bars are standard deviations. #, P value of <0.05, determined by a two-tailed Student t test; NS, comparison was not significant (P > 0.05).

As VpsT and VpsR were necessary for tag expression, we repeated the experiment in ΔvpsT and ΔvpsR mutant backgrounds and found that these strains lacked a c-di-GMP-mediated increase in MMS tolerance (Fig. 5B, C, and E). Similarly, high c-di-GMP concentrations did not significantly increase the survival of a V. cholerae Δtag mutant (Fig. 5D and E). Interestingly, the Δtag mutant was only slightly more sensitive to MMS than the parent strain (Fig. 5E), indicating that under basal c-di-GMP conditions, Tag plays a small role in MMS resistance. Complementing the Δtag mutant strain by overproducing Tag from a plasmid restored parent survival (Fig. 5F). Together, these data indicate that high c-di-GMP conditions promote the growth of V. cholerae in the presence of alkylation damage.

Induction of tag by c-di-GMP suggests that DNA repair might be important in V. cholerae biofilm formation. To test this hypothesis, we measured biofilm formation of the WT and the Δtag mutant exposed to 0, 3, and 6 mM MMS. The deletion of tag did not affect biofilm formation at either concentration, which we hypothesize is due to redundant mechanisms for dealing with MMS damage in a biofilm. Interestingly, the addition of MMS significantly increased biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner in both the WT and Δtag mutant backgrounds (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

The dinucleotide second messenger c-di-GMP is best known for its role in transition from a motile state to a biofilm state in many Gram-negative bacteria, including V. cholerae (3). In many cases, genes involved in biofilm formation are turned on through changes in the activities of transcription factors (22, 25, 27, 43). Past studies indicate that there are potentially multiple genes or pathways regulated by c-di-GMP besides genes directly related to motility or biofilm formation (10, 22, 27, 44). In this study, we demonstrate that c-di-GMP regulates expression of the DNA repair gene tag. Strains lacking the biofilm regulators VpsT and VpsR were unable to induce tag expression at high c-di-GMP concentrations. Importantly, we demonstrate that VpsT induction of tag leads to increased tolerance to MMS when cells have high intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations independent of biofilm formation.

We determined that the region necessary for tag expression by c-di-GMP is between 566 bp and 392 bp upstream of the ATG translational start codon. Additionally, this region is in the coding region of the upstream gene vexK encoding the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) multidrug efflux pump VexK. VexK can efflux detergents and was upregulated in human volunteers of V. cholerae infection, while tag was not identified as an in vivo-expressed gene, suggesting that tag is not upregulated during human host infection and that these genes are under independent regulatory control (45, 46).

We determined that the transcriptional start of tag is located 502 bp upstream of the translation start site. This transcription start site was independently identified in a systematic RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis to identify all the transcription start sites of V. cholerae (47). Thus, the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) for tag mRNA is 502 bp long. The most common 5′ UTR lengths in the Gram-negative organisms E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae range from 25 to 35 bp, with the longest reaching 700 bp (48). The relatively long 5′ UTR of the tag transcript suggests that c-di-GMP may be only one of the signals regulating tag expression in V. cholerae. It is possible that there are additional transcriptional start sites closer to the translation start site of tag that were missed in our analyses; however, a luciferase fusion to this region (tag4) showed no activity above the vector control level, and no such start sites were detected in the previously published RNA-seq analysis (47). The function of this long 5′ UTR in DNA repair is an intriguing question that warrants further investigation. Interestingly, a systematic search for small RNAs (sRNAs) detected a putative sRNA in this 5′ UTR from bases −227 to −121 relative to the ATG start codon located on the coding strand of the tag gene (49). Due to the lack of additional transcription start sites in this region, we hypothesize that this sRNA might be processed from the 5′ UTR of tag. Whether this sRNA has any biological function remains to be determined.

In V. cholerae, three transcription factors act to sense and respond to c-di-GMP by altering transcription at key promoters of genes necessary for VPS or flagellar biosynthesis. VpsR and VpsT are c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factors that induce expression of the VPS operon when intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations are high (22, 27, 50). We demonstrate that both VpsR and VpsT are necessary for the induction of tag by c-di-GMP, but VpsT appears to directly regulate this gene (Fig. 6). Binding site sequences exist for VpsT in the promoters of vpsL, a component of the VPS operon, and the promoter for the stationary-phase sigma factor rpoS; however, we could not identify a canonical VpsT binding site in the tag promoter (41, 51). We are currently working to determine the VpsT binding sequence in the tag promoter. FlrA, the c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factor necessary for flagellar biosynthesis, was not needed for tag induction by c-di-GMP, suggesting that tag expression is not advantageous in a motile lifestyle.

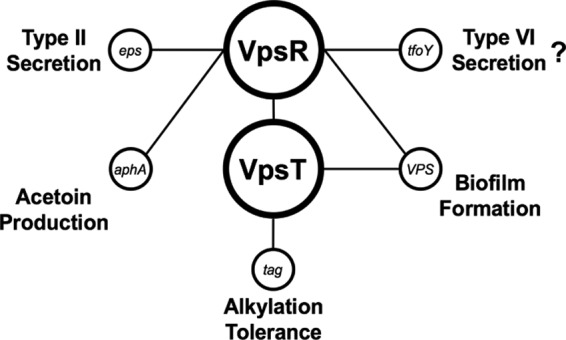

FIG 6.

Model of the VpsR/VpsT c-di-GMP regulatory network in V. cholerae. In response to high c-di-GMP concentrations, VpsR becomes an active transcription factor and induces the expression of vpsT. VpsT is also a c-di-GMP-dependent transcription factor and together, VpsT and VpsR induce the expression of genes involved in biofilm formation. c-di-GMP-activated VpsR has been shown to directly regulate promoters other than those that regulate biofilm production, such as tfoY, which regulates motility and type VI secretion, the eps operon involved in type II secretion, and aphA, which regulates acetoin production. In this work, we uncovered another phenotype regulated by the central c-di-GMP-dependent transcription factors, which is alkylation tolerance through the induction of tag indirectly by VpsR and directly by VpsT.

A previous microarray analysis suggests that c-di-GMP can regulate other forms of DNA repair in addition to the BER pathway in V. cholerae. Overproduction of a DGC in the El Tor biotype A1552 resulted in the upregulation of mutL, a gene involved in methyl-directed mismatch repair, while in the classical biotype O395, DGC overproduction led to an increase in the gene encoding photolyase (phrB), which is involved in light-dependent DNA repair after UV radiation damage (15). Although these regulatory pathways have not been studied, the multiple connections to DNA repair suggest that tag induction by c-di-GMP may just be one example of how V. cholerae uses c-di-GMP signaling to coordinate DNA repair.

Various stressors, including DNA-damaging agents, increase biofilm formation in E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (52, 53). Additionally, the SOS response pathway regulates biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa, demonstrating a link between DNA damage and biofilm formation (54). In contrast, growth in a biofilm increases mutability in P. aeruginosa through the production of endogenous reactive oxygen species (55). These findings demonstrate that stress can induce biofilm formation, or, conversely, that biofilms can induce stress. We hypothesized that c-di-GMP-induced tag expression likely accompanies environmental biofilm formation in V. cholerae, based on the following pieces of evidence: (i) VpsT regulates tag expression under high-c-di-GMP conditions, (ii) vpsT expression is epistatic to vpsR (39), and (iii) high levels of VpsR activated by c-di-GMP result in biofilm formation (50). However, biofilm formation in the WT strain was similar to that in the Δtag mutant strain under untreated and MMS-treated conditions. We hypothesize that the fitness advantage of tag induction by c-di-GMP may be relevant under other environmental conditions not tested here.

We demonstrate a novel example of dinucleotide second messenger signaling regulating a core cellular process, DNA repair. It is becoming clear that the roles of the VpsR and VpsT pathways in V. cholerae expand beyond biofilm formation. Indeed, this c-di-GMP regulatory node controls a variety of phenotypes in response to changing c-di-GMP concentrations, including type II secretion, acetoin production, and tfoY transcription (Fig. 6). Consequently, these two transcription factors should not be viewed solely as biofilm regulators but rather as the central transcriptional regulators of c-di-GMP-regulated phenotypes in V. cholerae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions and strain construction.

All strains, primers, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S1 to S3 in the supplemental material. The V. cholerae strains used in this study were derived from the El Tor biotype strain C6706str2. Where indicated, a strain unable to form mature biofilms was used (CW2034, ΔvpsL mutant [37]) to allow for accurate measurement of optical density and lux reporter gene expression. The ΔvpsT, ΔvpsR, ΔvpsT ΔvpsR, and Δtag unmarked mutant strains were constructed in the ΔvpsL mutant parent strain using the pKAS32 suicide vector, as described previously (56). All V. cholerae strains were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 35°C with shaking at 220 rpm, unless stated otherwise. Concentrations of 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 100 μg/ml kanamycin, 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 100 μM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were added when needed. Escherichia coli S17-λpir was used as the donor in biparental conjugation to mobilize plasmids into V. cholerae with selection against the donor using polymyxin B (10 U/ml).

DNA manipulations.

Standard procedures were used for DNA manipulations (57). PCR was carried out with Phusion polymerase (NEB). Restriction enzymes were purchased from NEB. The primers used in this study are listed in Table S3. Reporter plasmids were constructed by Gibson Assembly (NEB) using PCR-generated inserts and pBBRlux linearized by BamHI and SpeI restriction digestion. Expression vectors were constructed by Gibson Assembly using PCR-amplified inserts (vpsT, vpsR, and tag) and pEVS143 linearized by EcoRI and BamHI restriction digestion. The vectors used for gene deletions were generated by Gibson Assembly using three fragments: 1 kb of sequence upstream of the gene of interest, 1 kb of sequence downstream of the gene of interest, and MfeI- and BglII-linearized pKAS32. pET28B (Novagen) was used for protein purification. PCR-amplified vpsT (vca0952) was cloned into XhoI- and NcoI-linearized pET28b using Gibson Assembly.

Reporter gene expression.

Overnight cultures of V. cholerae or E. coli harboring reporter plasmids (pBBRlux derivatives) were diluted to a starting OD600 of 0.04 in 1 ml LB supplemented with appropriate concentrations of antibiotics and IPTG. Two hundred microliters of dilutions was added to black 96-well plates (Cellstar) in triplicate and grown at 35°C while shaking at 220 rpm. Luminescence readings were taken at mid-exponential phase using an EnVision multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer) and were normalized for relative light units (RLU) by dividing the luminescence reading by the OD600.

RNA isolation, quantitative real-time PCR, and 5′ RACE.

Overnight cultures of V. cholerae harboring QrgB or QrgB* were diluted 1:1,000 in 10 ml LB in triplicate, supplemented with appropriate concentrations of antibiotics and IPTG. Cultures were grown for 3 h (OD600, ∼1.0) at 35°C with shaking at 220 rpm. Cells were pelleted, and RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Five nanograms of total RNA was treated with Turbo DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the instructions in the manual. DNA-free RNA was converted into cDNA using GoScript reverse transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative real-time PCRs (qRT-PCRs) were carried out using SYBR green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with final primer concentrations of 250 nM. Data were analyzed via the ΔΔCT method using gyrA as a reference gene and cDNA from QrgB*-overproducing strains as the calibrator.

5′ RACE was carried out using the 5′ RACE assay (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was extracted from V. cholerae cells harboring the tag1 pBBRlux reporter plasmid and converted to cDNA. Primers for nested PCR amplification can be found in Table S3.

Protein expression and purification.

The VpsT-pET28b expression vector was transformed into E. coli BL21λ(DE3). Sequence-verified clones were cultured into 250 ml LB supplemented with kanamycin and grown at 35°C shaking at 220 rpm to an OD600 of 0.7. Protein expression was induced by adding a 1 mM final concentration of IPTG. The growth temperature was switched to 16°C and the shaking speed was lowered to 160 rpm, and cells were incubated overnight (approximately 16 h). Cells were pelleted and resuspended in buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 550 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, cOmplete mini EDTA-free Roche protease inhibitor tablets [2 per 50 ml], 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and lysed by homogenization.

Nickel nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Qiagen) was incubated in buffer A for 20 min at 4°C. Cell lysates were centrifuged for 25 min at 10,000 × g and 4°C to pellet insoluble material. The soluble lysate was incubated with the Ni-NTA resin for 30 min at 4°C. The column was washed with 20 column volumes of buffer A and eluted by step elution with buffer A supplemented with 75, 125, 250, and 500 mM imidazole. Elution fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and those containing protein were pooled and dialyzed against dialysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol [BME], 10% glycerol) overnight at 16°C. Protein concentrations were estimated using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad) with purified bovine serum albumin (Sigma) to generate a standard curve.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

EMSA reactions were carried out by incubating purified VpsT-HIS with 5′-FAM-labeled probes (FAM-tag3). Twenty-microliter reaction mixtures consisted of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM BME, and 10% glycerol. Poly(dI-dC) (Sigma) was added to all reaction mixtures at a concentration of 1 μg/μl. When indicated, c-di-GMP was added at a final concentration of 50 μM; otherwise, an equal volume of water was added. The 22-bp wild-type or 20-bp mutant VpsT binding site single-stranded oligomers were annealed to generate double-stranded oligomers by incubating equimolar ratios of complementary oligonucleotides (Table S3) at 94°C for 2 min and were cooled at room temperature overnight. A 100× molar excess competitor was added when indicated. All components except the labeled probe were mixed at room temperature and incubated for 10 min. FAM-tag3 probe was then added at a final concentration of 2.5 nM, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 30°C. Ten microliters of the reaction mixture was loaded onto a prerun 5% polyacrylamide Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gel, and electrophoresis was carried out for 90 min at 90 V at 4°C. Fluorescent band migration was visualized on Typhoon FLA 9000 imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Growth assays.

Overnight cultures were diluted to a starting OD600 of 0.004 in 1 ml LB supplemented with ampicillin and IPTG. Two hundred microliters of the culture was moved into wells of a 96-well plate (Cellstar) in triplicate and incubated at 35°C with shaking at 220 rpm. After 2 h of growth, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or MMS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added at the indicated concentrations, and growth was monitored by measuring the OD600 every hour for 10 h using an EnVision multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer). For calculating the percent survival, the quotient of the OD600 of MMS-treated wells divided by the OD600 of untreated wells was multiplied by 100 at a given time point.

Statistical analysis.

Data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses (details in figure legends) were calculated with Prism version 6 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material was supported by NIH grants GM109259, GM110444, and AI130554.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00005-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ross P, Weinhouse H, Aloni Y, Michaeli D, Weinberger-Ohana P, Mayer R, Braun S, de Vroom E, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, Benziam M. 1986. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325:279–281. doi: 10.1038/325279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galperin MY, Nikolskaya AN, Koonin EV. 2001. Novel domains of the prokaryotic two-component signal transduction systems. FEMS Microbiol Lett 203:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Römling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orr MW, Donaldson GP, Severin GB, Wang J, Sintim HO, Waters CM, Lee VT. 2015. Oligoribonuclease is the primary degradative enzyme for pGpG in Pseudomonas aeruginosa that is required for cyclic-di-GMP turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E5048–E5057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507245112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramírez-Guadiana FH, del Carmen Barajas-Ornelas R, Ayala-García VM, Yasbin RE, Robleto E, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2013. Transcriptional coupling of DNA repair in sporulating Bacillus subtilis cells. Mol Microbiol 90:1088–1099. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tschowri N, Schumacher MA, Schlimpert S, Chinnam NB, Findlay KC, Brennan RG, Buttner MJ. 2014. Tetrameric c-di-GMP mediates effective transcription factor dimerization to control Streptomyces development. Cell 158:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul R, Weiser S, Amiot NC, Chan C, Schirmer T, Giese B, Jenal U. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev 18:715–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.289504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abel S, Chien P, Wassmann P, Schirmer T, Kaever V, Laub MT, Baker TA, Jenal U. 2011. Regulatory cohesion of cell cycle and cell differentiation through interlinked phosphorylation and second messenger networks. Mol Cell 43:550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. 2005. The EAL domain protein VieA is a cyclic diguanylate phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem 280:33324–33330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506500200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sloup RE, Konal AE, Severin GB, Korir ML, Bagdasarian MM, Bagdasarian M, Waters CM. 2017. Cyclic di-GMP and VpsR induce the expression of type II secretion in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 199:e00106-. doi: 10.1128/JB.00106-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alam MT, Ray SS, Chun CN, Chowdhury ZG, Rashid MH, Madsen Beau De Rochars VE, Ali A. 2016. Major shift of toxigenic V. cholerae O1 from Ogawa to Inaba serotype isolated from clinical and environmental samples in Haiti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0005045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartels SA, Greenough PG, Tamar M, VanRooyen MJ. 2010. Investigation of a cholera outbreak in Ethiopia's Oromiya Region. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 4:312–317. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuna A, Gajewski M. 2017. Cholera—the new strike of an old foe. Int Marit Health 68:163–167. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2017.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischler AD, Camilli A. 2004. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol 53:857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beyhan S, Tischler AD, Camilli A, Yildiz FH. 2006. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J Bacteriol 188:3600–3613. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3600-3613.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutz C, Erken M, Noorian P, Sun S, McDougald D. 2013. Environmental reservoirs and mechanisms of persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Front Microbiol 4:375. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamayo R, Patimalla B, Camilli A. 2010. Growth in a biofilm induces a hyperinfectious phenotype in Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 78:3560–3569. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00048-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millet YA, Alvarez D, Ringgaard S, von Andrian UH, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2014. Insights into Vibrio cholerae intestinal colonization from monitoring fluorescently labeled bacteria. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004405. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler SM, Camilli A. 2004. Both chemotaxis and net motility greatly influence the infectivity of Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308052101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koestler BJ, Waters CM. 2014. Bile acids and bicarbonate inversely regulate intracellular cyclic di-GMP in Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 82:3002–3014. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01664-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casper-Lindley C, Yildiz FH. 2004. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 186:1574–1578. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1574-1578.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krasteva PV, Fong JC, Shikuma NJ, Beyhan S, Navarro MV, Yildiz FH, Sondermann H. 2010. Vibrio cholerae VpsT regulates matrix production and motility by directly sensing cyclic di-GMP. Science 327:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1181185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fong JCN, Syed KA, Klose KE, Yildiz FH. 2010. Role of Vibrio polysaccharide (vps) genes in VPS production, biofilm formation and Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis. Microbiology 156:2757–2769. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong JCN, Yildiz FH. 2007. The rbmBCDEF gene cluster modulates development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 189:2319–2330. doi: 10.1128/JB.01569-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava D, Hsieh M-L, Khataokar A, Neiditch MB, Waters CM. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP inhibits Vibrio cholerae motility by repressing induction of transcription and inducing extracellular polysaccharide production. Mol Microbiol 90:1262–1276. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacikova G, Lin W, Skorupski K. 2005. Dual regulation of genes involved in acetoin biosynthesis and motility/biofilm formation by the virulence activator AphA and the acetate-responsive LysR-type regulator AlsR in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 57:420–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivastava D, Harris RC, Waters CM. 2011. Integration of cyclic di-GMP and quorum sensing in the control of vpsT and aphA in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 193:6331–6341. doi: 10.1128/JB.05167-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metzger LC, Stutzmann S, Scrignari T, Van der Henst C, Matthey N, Blokesch M. 2016. Independent regulation of type VI secretion in Vibrio cholerae by TfoX and TfoY. Cell Rep 15:951–958. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pursley BR, Maiden MM, Hseih M-L, Fernandez NL, Severin GB, Waters CM. 2018. Cyclic di-GMP regulates TfoY in Vibrio cholerae to control motility by both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. J Bacteriol 200:e00578-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00578-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies BW, Bogard RW, Dupes NM, Gerstenfeld TA, iSimmons LA, Mekalanos JJ. 2011. DNA damage and reactive nitrogen species are barriers to Vibrio cholerae colonization of the infant mouse intestine. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001295. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krokan HE, Bjoras M. 2013. Base excision repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5:a012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gómez-Marroquín M, Vidales LE, Debora BN, Santos-Escobar F, Obregón-Herrera A, Robleto EA, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2015. Role of Bacillus subtilis DNA glycosylase MutM in counteracting oxidatively induced DNA damage and in stationary-phase-associated mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 197:1963–1971. doi: 10.1128/JB.00147-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogasawara H, Teramoto J, Hirao K, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A, Utsumi R. 2004. Negative regulation of DNA repair gene (ung) expression by the CpxR/CpxA two-component system in Escherichia coli K-12 and induction of mutations by increased expression of CpxR. J Bacteriol 186:8317–8325. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8317-8325.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Clayton RA, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Tettelin H, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Umayam L, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Read TD, Richardson D, Ermolaeva MD, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, Mcdonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann RD, Nierman WC, White O, Salzberg SL, Smith HO, Colwell RR, Mekalanos JJ, Venter JC, Fraser CM. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477–484. doi: 10.1038/35020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karran P, Lindahl T, Ofsteng I, Evensen GB, Seeberg E. 1980. Escherichia coli mutants deficient in 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase. J Mol Biol 140:101–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sikora A, Mielecki D, Chojnacka A, Nieminuszczy J, Wrzesiński M, Grzesiuk E. 2010. Lethal and mutagenic properties of MMS-generated DNA lesions in Escherichia coli cells deficient in BER and AlkB-directed DNA repair. Mutagenesis 25:139–147. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gep052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waters CM, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, Bassler BL. 2008. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J Bacteriol 190:2527–2536. doi: 10.1128/JB.01756-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radman M. 1975. SOS repair hypothesis: phenomenology of an inducible DNA repair which is accompanied by mutagenesis. Basic Life Sci 5A:355–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beyhan S, Bilecen K, Salama SR, Casper-Lindley C, Yildiz FH. 2007. Regulation of rugosity and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae: Comparison of VpsT and VpsR regulons and epistasis analysis of vpsT, vpsR, and hapR. J Bacteriol 189:388–402. doi: 10.1128/JB.00981-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conner JG, Zamorano-Sánchez D, Park JH, Sondermann H, Yildiz FH. 2017. The ins and outs of cyclic di-GMP signaling in Vibrio cholerae. Curr Opin Microbiol 36:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zamorano-Sánchez D, Fong JCN, Kilic S, Erill I, Yildiz FH. 2015. Identification and characterization of VpsR and VpsT binding sites in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 197:1221–1235. doi: 10.1128/JB.02439-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayala JC, Wang H, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. 2015. Repression by H-NS of genes required for the biosynthesis of the Vibrio cholerae biofilm matrix is modulated by the second messenger cyclic diguanylic acid. Mol Microbiol 97:630–645. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hickman JW, Harwood CS. 2008. Identification of FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factor. Mol Microbiol 69:376–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim B, Beyhan S, Meir J, Yildiz FH. 2006. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol 60:331–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bina XR, Provenzano D, Nguyen N, Bina JE. 2008. Vibrio cholerae RND family efflux systems are required for antimicrobial resistance, optimal virulence factor production, and colonization of the infant mouse small intestine. Infect Immun 76:3595–3605. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01620-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lombardo M-J, Michalski J, Martinez-Wilson H, Morin C, Hilton T, Osorio CG, Nataro JP, Tacket CO, Camilli A, Kaper JB. 2007. An in vivo expression technology screen for Vibrio cholerae genes expressed in human volunteers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:18229–18234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705636104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papenfort K, Förstner KU, Cong J-P, Sharma CM, Bassler BL. 2015. Differential RNA-seq of Vibrio cholerae identifies the VqmR small RNA as a regulator of biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E766–E775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500203112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim D, Hong JS-J, Qiu Y, Nagarajan H, Seo J-H, Cho B-K, Tsai S-F, Palsson BØ. 2012. Comparative analysis of regulatory elements between Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae by genome-wide transcription start site profiling. PLoS Genet 8:e1002867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley ES, Bodi K, Ismail AM, Camilli A. 2011. A genome-wide approach to discovery of small RNAs involved in regulation of virulence in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002126. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yildiz FH, Dolganov NA, Schoolnik GK. 2001. VpsR, a member of the response regulators of the two-component regulatory systems, is required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and EPS(ETr)-associated phenotypes in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J Bacteriol 183:1716–1726. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1716-1726.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Ayala JC, Benitez JA, Silva AJ. 2014. The LuxR-type regulator VpsT negatively controls the transcription of rpoS, encoding the general stress response regulator, in Vibrio cholerae biofilms. J Bacteriol 196:1020–1030. doi: 10.1128/JB.00993-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang XS, Garcia-Contreras R, Wood TK. 2007. YcfR (BhsA) influences Escherichia coli biofilm formation through stress response and surface hydrophobicity. J Bacteriol 189:3051–3062. doi: 10.1128/JB.01832-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gotoh H, Zhang Y, Dallo SF, Hong S, Kasaraneni N, Weitao T. 2008. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, under DNA replication inhibition, tends to form biofilms via Arr. Res Microbiol 159:294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gotoh H, Kasaraneni N, Devineni N, Dallo SF, Weitao T. 2010. SOS involvement in stress-inducible biofilm formation. Biofouling 26:603–611. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2010.501895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boles BR, Singh PK. 2008. Endogenous oxidative stress produces diversity and adaptability in biofilm communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:12503–12508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801499105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 1996. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene 169:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green MR, Sambrook J. 2014. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.