Many Vibrio species are zoonotic pathogens, infecting both animals and humans, resulting in significant morbidity and, in extreme cases, mortality. While many Vibrio species virulence genes are known, their associated regulation is often modestly understood. We set out to identify genetic factors of V. parahaemolyticus that are involved in activating exsA gene expression, a process linked to a type III secretion system involved in host cytotoxicity. We discover that V. parahaemolyticus employs a genetic regulatory switch involving H-NS and HlyU to control exsA promoter activity. While HlyU is a well-known positive regulator of Vibrio species virulence genes, this is the first report linking it to a transcriptional master regulator and type III secretion system paradigm.

KEYWORDS: HlyU, Vibrio, enteric pathogens, gene regulation, transposons, type III secretion

ABSTRACT

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a marine bacterium that is globally recognized as the leading cause of seafood-borne gastroenteritis. V. parahaemolyticus uses various toxins and two type 3 secretion systems (T3SS-1 and T3SS-2) to subvert host cells during infection. We previously determined that V. parahaemolyticus T3SS-1 activity is upregulated by increasing the expression level of the master regulator ExsA under specific growth conditions. In this study, we set out to identify V. parahaemolyticus genes responsible for linking environmental and growth signals to exsA gene expression. Using transposon mutagenesis in combination with a sensitive and quantitative luminescence screen, we identify HlyU and H-NS as two antagonistic regulatory proteins controlling the expression of exsA and, hence, T3SS-1 in V. parahaemolyticus. Disruption of hns leads to constitutive unregulated exsA gene expression, consistent with its known role in repressing exsA transcription. In contrast, genetic disruption of hlyU completely abrogated exsA expression and T3SS-1 activity. A V. parahaemolyticus hlyU null mutant was significantly deficient for T3SS-1-mediated host cell death during in vitro infection. DNA footprinting studies with purified HlyU revealed a 56-bp protected DNA region within the exsA promoter that contains an inverted repeat sequence. Genetic evidence suggests that HlyU acts as a derepressor, likely by displacing H-NS from the exsA promoter, leading to exsA gene expression and appropriately regulated T3SS-1 activity. Overall, the data implicate HlyU as a critical positive regulator of V. parahaemolyticus T3SS-1-mediated pathogenesis.

IMPORTANCE Many Vibrio species are zoonotic pathogens, infecting both animals and humans, resulting in significant morbidity and, in extreme cases, mortality. While many Vibrio species virulence genes are known, their associated regulation is often modestly understood. We set out to identify genetic factors of V. parahaemolyticus that are involved in activating exsA gene expression, a process linked to a type III secretion system involved in host cytotoxicity. We discover that V. parahaemolyticus employs a genetic regulatory switch involving H-NS and HlyU to control exsA promoter activity. While HlyU is a well-known positive regulator of Vibrio species virulence genes, this is the first report linking it to a transcriptional master regulator and type III secretion system paradigm.

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a ubiquitous marine bacterium and is a leading cause of seafood-borne gastroenteritis globally (1). In brackish estuaries, these Gram-negative bacteria exist free-living in the water column, within marine sediments, and in commensal relationships with many bivalve shellfish, including oysters (2). After human consumption of contaminated shellfish, V. parahaemolyticus can cause vibriosis, leading to nausea, fever, diarrhea, and occasionally vomiting. Although generally self-limiting, V. parahaemolyticus causes significant morbidity during foodborne outbreaks (3). V. parahaemolyticus environmental isolates frequently exhibit genetic profiles; however, a clinically relevant pandemic V. parahaemolyticus serotype (O3:K6) has emerged, being isolated in patients around the world (1, 4). Additionally, specific V. parahaemolyticus strains that possess a toxin-antitoxin plasmid have emerged as significant shrimp pathogens, where major economic losses have occurred in aquaculture industries (5, 6). Thus, it appears these marine bacteria continue to evolve and are a serious threat to the seafood industry and human health.

V. parahaemolyticus virulence factors include hemolysins, toxins, and two type III secretion systems (T3SS), T3SS-1 and T3SS-2. The T3SS of pathogens acts as a molecular needle-like structure to deliver bacterial effector proteins into host cells (7). Sequence analysis of various V. parahaemolyticus clinical isolates has revealed that many contain both T3SSs (8, 9). T3SS-2 has primarily been linked to enterotoxicity (10, 11), whereas T3SS-1 has been linked to cellular disruption and rapid cytotoxicity (12–14). Many effectors are delivered via T3SS-1 into host cells and have targeted actions. VopQ contributes to rapid cell death during V. parahaemolyticus infection by interacting with lysosomal H+ V-ATPases, causing lysosomal rupture and release of contents (15). Additionally, T3SS-1 effector proteins VopS, VopR, and VPA0450 have been implicated in immune evasion and actin rearrangement (13, 16). Other virulence mechanisms in V. parahaemolyticus include colonization factors (such as pili) and two type 6 secretion systems (T6SS) that likely aid in killing other bacteria or acting on macrophages during infection (17–19).

Over 40 genes within multiple genetic operons contribute to the formation of V. parahaemolyticus T3SS-1. The majority of these genes require the master regulator ExsA for their expression (20). ExsA and its orthologues in other bacteria are members of the AraC/XylR family of transcriptional regulators, many of which are implicated in bacterial pathogenesis mechanisms (21). In the cases of Yersinia species (LcrF), Pseudomonas species (ExsA), and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC; GrlA), these regulators have been demonstrated to activate T3SS-related genes and have been linked to virulence phenotypes (22–25).

ExsA transcriptional activator roles are well documented, although it is not known how V. parahaemolyticus interprets environmental signals to activate exsA expression and thus initiate T3SS-1 biogenesis. In this study, we used a genome-wide transposon mutagenesis approach to identify genetic regulators of exsA expression. Through the design of a sensitive and quantitative luminescence screen, we identified a cis-acting genetic switch and implicate HlyU as a critical V. parahaemolyticus virulence determinant.

RESULTS

A sensitive functional screen identifies genes linked to exsA promoter activation.

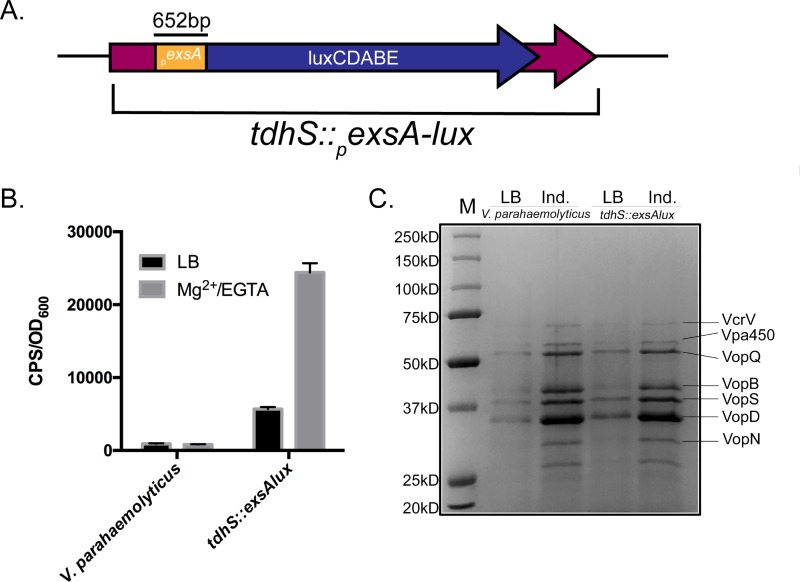

We initially generated a recombinant V. parahaemolyticus strain containing a promoterless bioluminescent reporter cassette (luxCDABE) transcriptionally fused to the exsA promoter region from V. parahaemolyticus. The pexsA-luxCDABE fusion was integrated into the tdhS locus of the V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 genome (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1A). We chose the tdhS locus, as TdhS is not required for T3SS-1 activity (14). This strain (referred to as the Vp-lux strain) quantitatively reports the activity of the exsA promoter in real time by emitting bioluminescence, thereby allowing for sensitive in situ measurement of exsA promoter activation (Fig. 1B). The strain responded to magnesium and EGTA (T3SS-1-inducing conditions) by increasing exsA promoter activity as expected (Fig. 1B). A T3SS-1 protein secretion assay indicated that the Vp-lux strain secreted effectors similarly to wild-type V. parahaemolyticus (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

Integration of an exsA promoter-luxCDABE fusion into the tdhS locus (tdhS::exsA-lux) results in bioluminescence and a normal T3SS-1 secreted protein profile. (A) Schematic representation of the constructed exsA promoter-luxCDABE fusion inserted within the tdhS chromosomal locus. (B) Comparison of bioluminescence emitted by the indicated V. parahaemolyticus strains. Bacteria were cultured under T3SS-1-inducing conditions, sampled after 3 h of growth, and then assessed for light emission. cps/OD, counts per second divided by optical density (600 nm) of the cell suspension at time of collection. (C) Total secreted protein profiles of V. parahaemolyticus strains as determined by SDS-PAGE. Bacteria were grown in LB medium or LB supplemented with MgSO4 and EGTA (induced [Ind.] for T3SS-1 activity). Labeled protein species have been previously identified by mass spectrometry analyses in wild-type V. parahaemolyticus (35). M, protein standard.

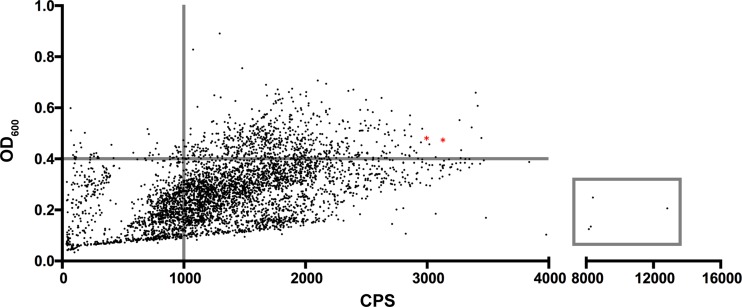

Consequently, we employed a conjugative plasmid encoding a hyperactive transposase and its associated transposon (26) to mutagenize the Vp-lux strain. An optimized triparental mating approach resulted in the isolation of 4,302 stable transposants at an average transposition frequency of 1 × 10−6. Using a high-throughput 96-well plate formatted assay, the transposants were screened for exsA promoter activity via bioluminescence. The Vp-lux strain served as a reference for defined normal growth and light emission. The screen identified a spectrum of mutants that exhibited altered bioluminescence levels compared to those of the parent Vp-lux strain (Fig. 2). Prior to investigating specific mutants, they were divided into 4 groups (or quadrants) to facilitate downstream analyses. This was achieved by establishing categories based on an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4 and a counts per second (cps) value of 1,000 and produced four quadrants (separate groups), including low-bioluminescence and normal growth, normal bioluminescence and normal growth, low bioluminescence and low growth, and high bioluminescence and any growth (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Bioluminescence scatterplot of Vp-lux Tn5 insertional mutants. Transposon insertion mutants were assayed for bioluminescence emission. Each dot represents an individual mutant, and two representative controls (Vp-lux strain) are indicated as red asterisks. The vertical and horizontal bars represent boundaries used to categorize mutants based on light emission (exsA promoter activity) and cell growth, respectively. The box encompasses high-light-emitting mutants selected for further study. CPS, counts per second.

Mutants that fell into the low-luminescence and normal-growth quadrant were further subjected to statistical narrowing. Using a binning procedure, mutants were subdivided into three categories by luminescence emission (measured in counts per second; low bioluminescence, 0 to 100 cps; low-moderate bioluminescence, 101 to 300 cps; and moderate bioluminescence, 301 to 1,000 cps). The means and standard deviations for each group were calculated. The means and standard deviations were calculated as 63.30 ± 10.68, 155.1 ± 22.32, and 542.7 ± 126.6, respectively. Six mutants whose cps reading was less than 1 standard deviation below the mean were then selected for further characterization in the low-bioluminescence group. Within the low-moderate and moderate bioluminescence groups, 3 and 4 mutants were selected for characterization, respectively. Lastly, 5 of the most bioluminescent mutants (Fig. 2, gray box) were also selected for characterization. Details of the selected mutants and statistical data are listed in the supplemental material (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Identification of genes with specific insertional transposons that alter exsA promoter activity.

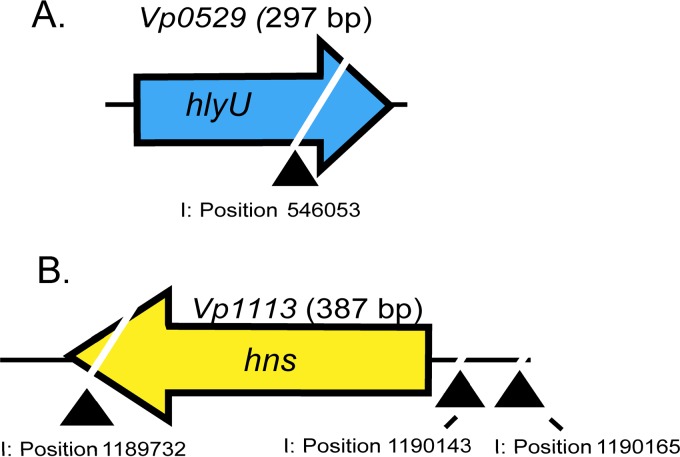

Using a genomic DNA marker retrieval protocol, we successfully identified chromosomal locations of transposition within mutants from the low-moderate and moderate light-emitting groups. From the low-moderate luminescence group linked to deficient exsA promoter activity, we mapped transposon insertions exclusively within Vp0529 (Fig. 3A). Notably, for Vp0529, we identified three isolates with the exact same transposon insertion site. These likely represent a single clone that generationally expanded during the mutagenesis procedure or, alternatively, this chromosomal site is favored for transposon insertion. For the moderate bioluminescence group, we mapped two transposon insertion mutants, Vpa0179 (phoX) and Vp1473 (merR operon) (Fig. S1). Within the high-luminescence group linked to increased exsA promoter activity, 3 independent transposon insertions were mapped near or within Vp1133 (hns) (Fig. 3B) and one insertion was mapped within Vp1633 (RTX toxin) (Fig. S1).

FIG 3.

Schematic diagram of transposon insertion sites within selected genes of interest identified by luminescence screening of the Vp-lux Tn5 mutant library. The triangles represent approximate transposon insertion sites with the approximate DNA base location in the V. parahaemolyticus genome (NBCI accession numbers NC_004603 and NC_004605; I, chromosome I).

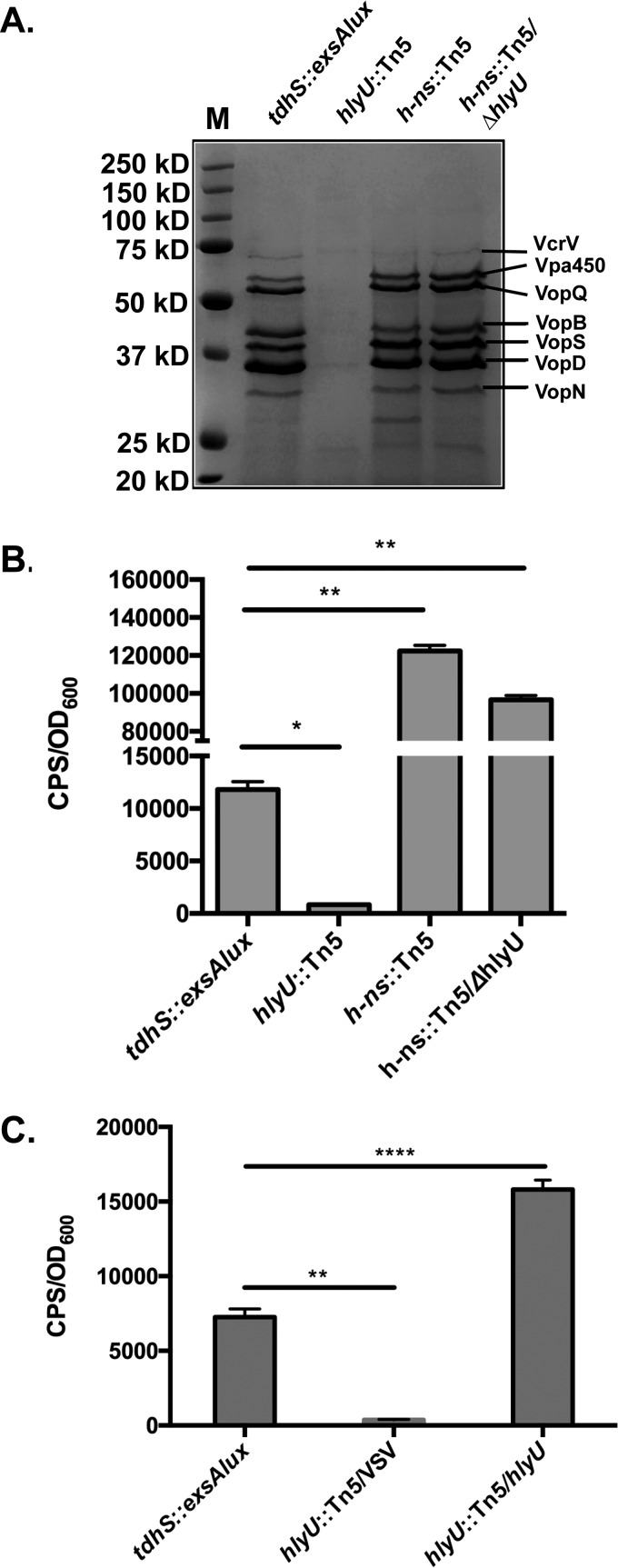

Our initial efforts focused on Vp0529 and Vp1133, since multiple independent mutant insertions were isolated from the lux reporter screen for these genes (Fig. 3) and therefore strongly implied a role in exsA regulation. In silico analysis of Vp0529 using NCBI BLAST indicated sequence similarity to HlyU, a DNA binding protein of many Vibrio species that acts as a positive regulator of virulence genes (27–31). Vp1133 encodes a histone-like nucleoid-structuring protein (H-NS) and has previously been implicated in exsA repression (32). To investigate this further, an assay that evaluates T3SS-1 protein secretion was performed. Critically, a marked decrease in many T3SS-1-dependent proteins was observed for the Vp0529 Tn5 insertion mutant compared to the Vp-lux parent strain (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the Vp1133 mutant displayed secretion of many T3SS-1-dependent proteins, comparable to the parent strain.

FIG 4.

Protein secretion and exsA promoter activity assays with the Vp-lux (tdhS::exsA-lux) strain and specific transposon insertion mutants. (A) Total secreted proteins were collected from culture supernatants of the indicated Tn5 insertion mutants and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining. A protein ladder was included (M), and previously identified proteins are labeled. (B) Luciferase assays were conducted with the indicated Tn5 insertion mutants and the hns::Tn5 ΔhlyU double mutant (strain Vp-EL) (n = 2). The error bars indicate standard deviations from the mean values. A two-tailed t test was conducted to compare data sets. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005. (C) Complementation of the hlyU::Tn5 mutant with pVSV105 encoding hlyU was performed, followed by a luciferase assay. A two-tailed t test was used to compare data sets. **, P < 0.005; ****, P < 0.0001.

HlyU has previously been implicated as an H-NS derepressor, leading to rtxA1 toxin expression in V. vulnificus (33). To investigate if HlyU acts as a derepressor of H-NS in V. parahaemolyticus or, alternatively, as a bona fide transcriptional activator, we deleted hlyU in the context of the hns::Tn5 mutant (strain Vp-EL) and performed protein secretion and luciferase reporter assays. Vp-EL behaved similarly to the Δhns::Tn5 mutant, exhibiting T3SS-1 effectors and translocators along with enhanced luciferase activity (driven by the exsA promoter) (Fig. 4A and B). Therefore, in the absence of H-NS, HlyU is not required for T3SS-1 protein secretion or for exsA promoter activity. To confirm the role of HlyU for exsA promoter activity in cells expressing H-NS, we subjected the hlyU::Tn5 mutant to genetic complementation. Enhanced restoration of luminescence was observed for the hlyU complemented strain that was significantly above the level of the Vp-lux parent strain (Fig. 4C).

hlyU null mutants are deficient for T3SS-1-dependent secretion and cytotoxic effects.

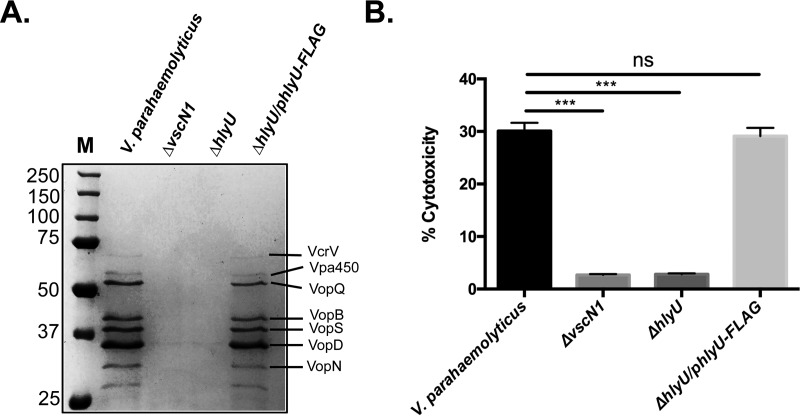

To validate the phenotypes measured in the hlyU::Tn5 mutant and to rule out any effects due to transposon insertion, an hlyU null mutant derived from wild-type V. parahaemolyticus was generated (strain hlyU1) and tested for protein secretion. In complete agreement with the hlyU::Tn5 mutant, T3SS-1 protein secretion for hlyU1 was deficient compared to that of wild-type V. parahaemolyticus and appeared similar to that of a ΔvscN1 T3SS-1-deficient strain (Fig. 5A). Genetic complementation of strain hlyU1 with the wild-type hlyU coding region in trans fully restored T3SS-1 protein secretion.

FIG 5.

V. parahaemolyticus ΔhlyU mutant (strain hlyU1) is deficient for secretion of T3SS-1 proteins and exhibits reduced host cell cytotoxicity during infection. (A) Total secreted proteins were collected and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie staining. A protein standard was included (M), and previously identified protein species are labeled. (B) Percent cytotoxicity was calculated after infection of HeLa cells with various strains by measuring released lactate dehydrogenase levels. All strains contained pVSV105 or phlyU-FLAG as indicated. Statistical bars indicate standard deviations from the means, and statistical significance was determined by a paired two-tailed t test compared to the V. parahaemolyticus control. ***, P < 0.001. ns, not significant.

To investigate the role of HlyU in the context of infection-like conditions, we conducted in vitro HeLa infections with V. parahaemolyticus strains followed by a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release cytotoxicity assay. As expected, wild-type V. parahaemolyticus resulted in rapid HeLa cytotoxicity in a vscN1 (T3SS-1 ATPase)-dependent manner (Fig. 5B), confirming previous reports (34, 35). hlyU1 was significantly deficient in producing HeLa cytotoxicity (Fig. 5B), comparing closely to the low cytotoxicity levels observed for the ΔvscN1 strain. Genetic complementation of hlyU1 restored HeLa cytotoxicity to wild-type V. parahaemolyticus levels, indicating that HlyU contributed to V. parahaemolyticus cytotoxic activity during in vitro infection.

Taken together, the protein secretion, promoter activation, and cytotoxicity data all indicated that HlyU was required for exsA promoter activation that supported expression of T3SS-1-related genes, leading to HeLa cell cytotoxicity during infection.

Purified HlyU binds upstream of exsA.

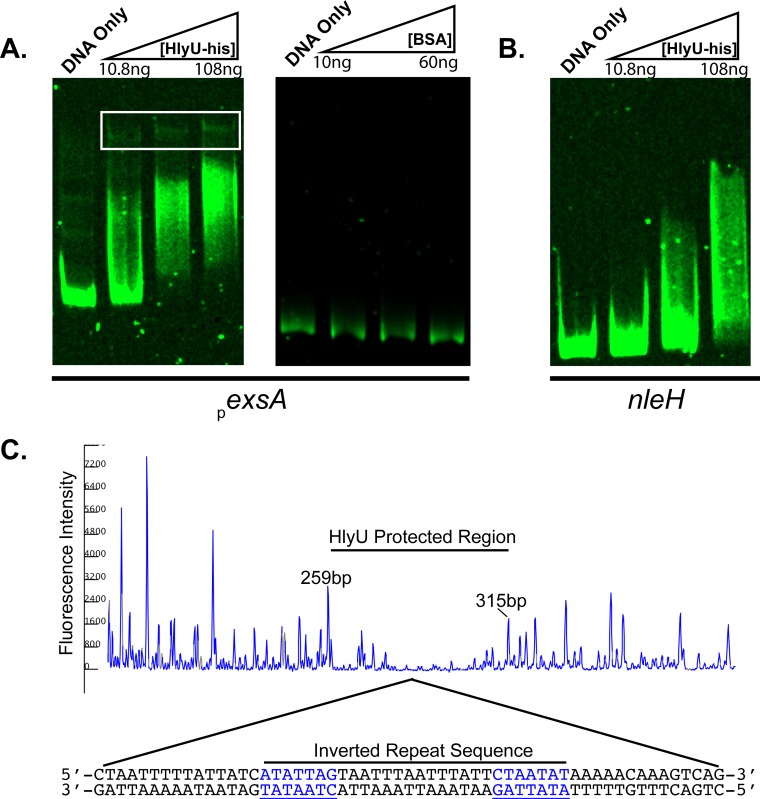

HlyU is a member of the SmtB/ArsR family of regulator proteins that bind to DNA using a winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) domain structure (27). Based on the hlyU1 deficiency for T3SS-1-associated phenotypes, we set out to investigate whether HlyU binds to V. parahaemolyticus DNA. We hypothesized that DNA near the exsA promoter (located within our lux reporter constructs) should contain sequences that direct HlyU binding to DNA. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed and purified a HlyU-His fusion protein (see Materials and Methods). Native HlyU is 98 amino acids in length (NCBI accession no. NP_796908.1) and has a predicted molecular mass of 11.2 kDa. Overexpressed HlyU-His appeared as an approximately 11-kDa protein by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S2). Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA) next were performed using an exsA promoter DNA fragment mixed with increasing amounts of purified HlyU protein. The exsA promoter DNA fragment demonstrated multiple shifts, with concentrated DNA species appearing with larger amounts of HlyU-His (Fig. 6A). For these larger HlyU-His amounts, Sypro red and SYBR green staining revealed protein-DNA complexes which appeared as tight bands coinciding with reduced mobility through the acrylamide gel matrix (Fig. S3). In contrast, no mobility shift was apparent for increasing amounts of bovine serum albumin (BSA), indicating that the exsA promoter region did not support nonspecific protein binding (Fig. 6A). Based on densitometric analyses of HlyU-bound exsA promoter DNA (Table S2), an apparent binding affinity ranging from 5 to 6.3 μM (95% confidence interval) was determined (Fig. S4). A nonspecific DNA fragment next was mixed with purified HlyU-His. While some minor shifts were observed at low HlyU levels (as seen by smearing), no major shifts or concentrated DNA species were apparent with increasing amounts of HlyU-His (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that small amounts of HlyU-His interacted with DNA weakly, and larger HlyU amounts specifically bound the exsA promoter region DNA, leading to homogenous protein-DNA complexes (see Discussion).

FIG 6.

Electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA footprinting assays indicate HlyU binding to a region within the exsA promoter. (A) Six percent TBE-polyacrylamide gels were loaded with reaction mixtures containing exsA promoter DNA and increasing amounts of purified HlyU-His or bovine serum albumin (BSA). An exsA promoter DNA-only control was included as indicated. The white box indicates slow-migrating, concentrated DNA species. (B) A 6% TBE-polyacrylamide gel was loaded with reaction mixtures containing nleH1 DNA and increasing amounts of purified HlyU-His. Following electrophoresis, gels were stained with SYBR green to specifically stain DNA. (C) A DNase I footprinting assay using purified HlyU-His was used to identify a DNA binding region for HlyU-His within the exsA promoter. The approximate base pair numbers of the HlyU-His footprint region are indicated (259 to 315 bp) and are based on capillary electrophoresis internal size standards. The DNA sequence associated with the identified HlyU protected region is displayed below the chromatogram. A 7-bp inverted repeat (labeled in blue) and separated by 14 bp is centrally located within the HlyU-His protected region.

HlyU protects an inverted repeat sequence within the exsA promoter region from DNase I digestion.

We set out to identify the DNA region bound by HlyU within the exsA promoter region. Fluorescently end-labeled exsA promoter DNA was mixed with purified HlyU-His and then treated with DNase I. The reaction mixtures were purified and then subjected to a DNA footprinting assay. As shown in Fig. 6C, a 56-bp region repeatedly and specifically produced low fluorescence signals indicative of an HlyU-protected region (undigested by DNase I). Sequence examination of this DNA region resulted in the identification of a perfect 7-base inverted repeat sequence, 5′-ATATTAG-3′, separated by an A/T tract of 14 bases. Furthermore, a 10-base direct-repeat palindromic sequence centered within the A/T tract is present (TAAATTAAAT) (Fig. 6C). Bioinformatic analyses indicated that this region of DNA is highly conserved in all current V. parahaemolyticus sequences in public databases and is located upstream of exsA in every case (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have identified a genetic regulatory switch that controls T3SS-1 gene expression by using a transposon mutagenesis approach coupled to a sensitive luciferase reporter screen. We set out to identify genes that promote exsA gene expression, which encodes the master transcriptional regulator of T3SS-1 in V. parahaemolyticus. The data suggest that V. parahaemolyticus HlyU acts as a derepressor by binding to DNA and relieving H-NS-mediated repression of exsA gene expression, thus leading to T3SS-1 activation. Critically, we demonstrated that HlyU is strictly required for V. parahaemolyticus to secrete specific effectors and induce rapid T3SS-1-mediated host cell cytotoxicity.

Within Vibrio species, it is well established that HlyU proteins act as global regulators of virulence genes. In V. vulnificus, HlyU functions to derepress the rtxA1 toxin gene antagonizing H-NS binding (36). In this way HlyU acts as a derepressor, by removal of the H-NS-mediated repression, and not as a true RNA polymerase-recruiting transcriptional activator. In V. cholerae, HlyU acts to enhance promoter activity at genes associated with virulence. Insertional mutation of the hlyU gene in V. cholerae leads to a significant decrease in virulence within an infant mouse infection model, highlighting the importance of this gene for virulence (31). In V. anguillarum, HlyU controls the expression of the rtxACHBDE and vahI gene clusters, whose protein products mediate the V. anguillarum hemolysin and cytotoxicity activities in fish (29).

Our data provide evidence that V. parahaemolyticus utilizes HlyU to positively regulate T3SS-1 expression, which is, to our knowledge, the first report linking this regulator to a type III secretion paradigm. Our transposon library approach separately and frequently identified both hlyU and hns as encoding protein regulators of exsA expression. H-NS has previously been implicated in T3SS-1 regulation in V. parahaemolyticus (32); therefore, we have independently confirmed those findings using a different approach. Our data suggest that HlyU is critical to derepress the exsA promoter by disrupting H-NS activity. In the absence of H-NS, HlyU is not required for exsA promoter activity (Fig. 4B). Instead, extremely elevated exsA promoter activity was observed in the absence of H-NS, suggesting that HlyU is not strictly required to activate the exsA promoter and likely serves a role to displace a negative regulator. Collectively, the data suggest that HlyU and H-NS form a genetic regulatory switch that serves to tightly control T3SS-1 gene expression in V. parahaemolyticus. Different genetic regulatory factors likely contribute to auxiliary exsA regulation, as our screen did identify other genes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material); however, the robustness of the phenotypes linked to hlyU and hns mutants implicate these respective genes in a central regulatory mechanism for V. parahaemolyticus T3SS-1 gene expression.

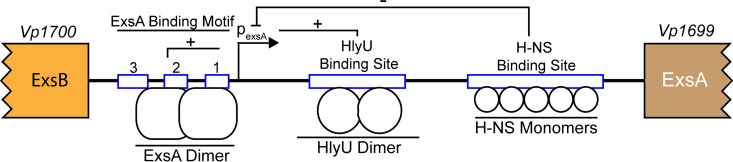

Negative regulation mediated by H-NS is a common paradigm for virulence genes, especially those found within genomic pathogenicity islands (37). It has been proposed that H-NS acts to protect the genome from foreign DNA that is acquired from various genetic transfer events. H-NS propensity to binding A/T-rich sequences likely serves to silence deleterious gene expression, which could stabilize the acquisition of new DNA while limiting detrimental fitness costs (38). Furthermore, pathogens capable of conditionally derepressing H-NS by expressing specialized DNA binding regulatory proteins would benefit from fine-tuning of virulence gene expression. Indeed, multiple examples of H-NS derepression by DNA binding proteins are known, including HilD (Salmonella), Ler (E. coli), and VirB (Shigella) (39–41). Many of these proteins bind at distinct DNA motifs and promote bending or alteration of DNA structure at specific genome sites. The consequence of DNA binding often locally displaces H-NS, thus supporting efficient promoter access and gene transcription (42). In the case of V. parahaemolyticus, we demonstrate that HlyU binds to DNA downstream of a previously reported exsA transcriptional start site and adjacent to where H-NS binds the DNA (43) (Fig. 7). The current data are not able to identify the exact regulatory mechanism underlying the HlyU–H-NS regulation of exsA expression; however, we hypothesize that under certain environmental or infection conditions HlyU is crucial to trigger exsA promoter activity.

FIG 7.

Schematic diagram of the intergenic region involved in exsA gene regulation. The ExsA binding motif and H-NS binding site have been previously identified. A putative HlyU binding site, as identified in this study, is shown. The ExsA binding motif has three box elements, each composed of conserved DNA sequences: 1, GC box; 2, A box; 3, TTAGN4TT. Protein-DNA interactions at specific sites within the exsA promoter region are shown. Plus and minus signs indicate positive and negative regulatory roles, respectively, on exsA promoter activity.

HlyU protein sequences are highly conserved among Vibrio species (ranging from 81 to 100% identity) (27). Numerous structure-function studies have established that HlyU proteins form stable homodimers and possess a winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) domain structure which is modeled to bind DNA within two major grooves (27, 44). Furthermore, HlyU dimerization is necessary for DNA binding activity in V. cholerae, and specific amino acids within HlyU contribute to DNA binding (27). These critical amino acids are conserved in all V. parahaemolyticus HlyU homologues within databases. We demonstrate here that V. parahaemolyticus HlyU binds to the DNA upstream of exsA using EMSA. Interestingly, we did observe various degrees of DNA shifts that were dependent on the amount of HlyU (Fig. 6A). A similar observation was previously reported for V. cholerae HlyU (27). The current data cannot differentiate if the DNA shifts were due to (i) increased HlyU binding at multiple sites, creating larger DNA-protein complexes, or (ii) different physical conformations of DNA-protein complexes. DNase I footprinting assays repeatedly detected a single contiguous 56-bp stretch of protected exsA promoter DNA, suggesting that HlyU binds at or near this site. We identified a perfect 7-base inverted repeat located within this putative HlyU binding site. This feature is in agreement with V. cholerae HlyU, which also binds at an inverted repeat near its rtx operon; however, the sequence motif is different in each case. HlyU proteins from other Vibrio species bind at different repeat-type sequence motifs (27, 29); thus, it appears that some flexibility in sequence recognition exists. HlyU is considered a global virulence regulator, so it might be expected to recognize different sequences across the genome. Additional detailed studies will be required to determine sequence specificity requirements for HlyU binding to DNA.

In summary, we have identified a primary genetic switch composed of the DNA binding proteins HlyU and H-NS that serves to regulate T3SS-1 gene expression in V. parahaemolyticus. V. parahaemolyticus required HlyU to support the expression of ExsA, the master transcriptional regulator of multiple T3SS-1-associated genes. During infection-like conditions, HlyU was necessary for rapid host cell cytotoxicity mediated by T3SS-1. HlyU bound DNA near an inverted repeat located upstream of exsA which likely disrupts H-NS-mediated repression at this gene locus in V. parahaemolyticus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 was grown in Luria broth (LB; L3522; Sigma) or LBS (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 20 g NaCl, pH 8.0). All mutant derivatives described in this study were derived from V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 (Table 1). All Escherichia coli strains were cultured in LB. The following antibiotics (Sigma) were used in growth medium as required: chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml and 30 μg/ml for V. parahaemolyticus and E. coli, respectively), erythromycin (10 μg/ml and 75 μg/ml for V. parahaemolyticus and E. coli, respectively), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and ampicillin (100 μg/ml). V. parahaemolyticus was routinely grown at 30°C or 37°C aerobically with shaking at 200 rpm for 16 to 18 h. Agar (A5306; Sigma) was added to medium at 1.5% (wt/vol) for solid medium preparations. All plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD 2210633 | Wild-type V. parahaemolyticus | 8 |

| ΔvscN1 strain | V. parahaemolyticus vscN1 null mutant | 35 |

| Vp-lux (tdhS::exsA-lux) strain | V. parahaemolyticus with the exsA promoter fused to luxCDABE gene cassette, integrated into chromosomal tdhS locus | This study |

| hlyU::Tn5 strain | Vp-lux strain with transposon-disrupting hlyU | This study |

| h-ns::Tn5 strain | Vp-lux strain with transposon-disrupting hns | This study |

| hlyU1 | V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 ΔhlyU | This study |

| Vp-EL | hns::Tn5-ΔhlyU | This study |

| DH5α | Escherichia coli cloning strain | Stratagene |

| DH5αλpir | E. coli host for oriR6K-dependent plasmid replication | |

| BL21(λDE3) | E. coli host for protein overexpression studies | Novagen |

| pRE112 | Suicide plasmid, R6K origin of replication | 49 |

| pJW15 | p15A-based plasmid with promoterless luxCDABE gene cassette | 50 |

| pΔtdhS | Deletion construct for tdhS within pRE112 | This study |

| ptdhS-exsAlux | Integration construct to place promoter exsA-luxCDABE onto the V. parahaemolyticus chromosome within the tdhS locus | This study |

| pEVS104 | Conjugative helper plasmid with mobilization machinery, used in triparental matings | 26 |

| pEVS170 | Mini-Tn5 transposon plasmid, erythromycin selection, R6K origin of replication | 26 |

| pVSV105 | Vibrio shuttle vector with lac promoter and multiple cloning site, replication competent in V. parahaemolyticus and DH5αλpir | 45 |

| pFLAG-CTC | Cloning plasmid to create C-terminal FLAG sequence fusions | Sigma |

| pFLAG-CTC-hlyU | hlyU fused with FLAG sequence | This study |

| phlyU-FLAG | Expresses hlyU under the control of the lac promoter in pVSV105 | This study |

Generation of a pexsA-luxCDABE transcriptional reporter in the V. parahaemolyticus tdhS allele.

Primers NT393 and NT390 (synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies [IDT]) were used in a PCR (with Phusion DNA polymerase; M0535S; New England BioLabs) with V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNA as the template. This approach amplified a contiguous DNA fragment encompassing upstream flanking sequence of tdhS to a partial coding sequence of the gene. Similarly, primers NT391 and NT392 were used to amplify a distal tdhS coding sequence and downstream flanking DNA. These DNA fragments were digested with PacI, ligated together with T4 DNA ligase, and then used as a DNA template in a PCR with primers NT393 and NT392. The resulting DNA fragment was blunt-end cloned into the Eco53kI site of pRE112 to create pΔtdhS. Primers NT337 and NT339 next were used with V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNA in a PCR to amplify the V. parahaemolyticus exsA promoter region. The resulting DNA product was subjected to restriction digestion with EcoRI and BamHI and then cloned upstream of the promoter-less luxCDABE gene cassette in pJW15. Finally, PacI digestion was used to excise the exsA-luxCDABE DNA fragment from pJW15, which was then cloned into the PacI site of pΔtdhS to generate ptdhS::exsAlux. ptdhS::exsAlux then served as a chromosomal integration suicide construct via delivery into V. parahaemolyticus using triparental conjugal mating. Chromosomal integrants were selected with medium containing chloramphenicol and then streak purified. The integrants were then subjected to allelic exchange by SacB-mediated sucrose selection. Stable integrants within the tdhS allele were screened by PCR and then confirmed by Sanger sequencing. All oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

List of oligonucleotides used in this study

| Designation | Sequence (5′→3′) | Description or purpose |

|---|---|---|

| NT337 | CCGAATTCAATCGGTTACATTTAATTAGCGC | exsA promoter forward |

| NT339 | CCGGATCCCCGTTTCTGTGTTTAGTTGGCCTG | exsA promoter reverse |

| AL390 | CGCTTAATTAATACATTGACCGGAGCTTG | tdhS mutant construction |

| AL391 | CCTTAATTAAAGAGCGGTCATTCTGCTG | tdhS mutant construction |

| AL393 | AGCTTACAGCTTGGTATGCCT | tdhS mutant construction |

| AL394 | GTGGCTATGCACTGGCAGAT | tdhS mutant construction |

| NT394 | AAGAGCTCACAGTATCCACTTACGTTGTTACG | ΔhlyU mutant construction |

| NT395 | AACTCGAGTTCTTGTAGATTCATGTGTTGG | ΔhlyU mutant construction |

| NT396 | AACTCGAGTGCGCAAACTGATCGCACAGACTG | ΔhlyU mutant construction |

| NT397 | AAGGTACAAGCACGAGCAATCAACTCGC | ΔhlyU mutant construction |

| NT398 | AACTCGAGTCAAGATACTTGGTTTAGTGAGC | hlyU genetic complementation |

| NT399 | AAGGTACCGTTTGCGCAATAAAGACCGTGAAGG | hlyU genetic complementation |

| NT400 | AGAATTCCATATGAATCTACAAGAAATGGAGAA | HlyU overexpression |

| NT401 | AACTCGAGGTTTGCGCAATAAAGACCGTGAAGG | HlyU overexpression |

| NT402 | 6-FAMN/CCGAATTCAATCGGTTACATTTAATTAGCGC | exsA promoter forward-6-FAM |

| M13F | GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | Sequencing primer |

| nleH1-F | GCGGTACCATGCTATCACCATCTTCTGTAAA | nleH1 gene fragment |

| nleH1-R | GCACAATTGCCAATTTTACTTAATACCACACTAATAAG | nleH1 gene fragment |

Generation of strain hlyU1 and construction of a plasmid for hlyU1 genetic complementation.

A DNA fragment with the hlyU allele deleted was derived from V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNA by ligation PCR (primers are described in Table 2), cloned into pRE112, and then introduced into wild-type V. parahaemolyticus. Chloramphenicol selection for allelic exchange and then sucrose selection generated an hlyU null strain denoted the hlyU1 strain. An hlyU1 complementation construct was built using vibrio shuttle vector pVSV105 as a plasmid backbone (45). The hlyU DNA coding region was amplified by PCR using primers NT398 and NT399 and V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNA as the template. The hlyU DNA fragment was directionally cloned into pVSV105 as a KpnI and XhoI fragment. The resulting plasmid was transformed into E. coli DH5αλpir and then conjugated into the appropriate V. parahaemolyticus strains.

Mini-Tn5 mutant library generation within the Vp-lux reporter strain.

A mutagenesis procedure was followed, with minor modifications (26). Briefly, a conjugal mating on LBS agar allowed for the delivery of the plasposon pEVS170 into the Vp-lux strain. The mating mixture was plated onto selective LBS agar medium (pH 8.0) containing 10 μg/ml erythromycin and incubated at 22°C for 36 h. Transposants were then individually picked and grown on M9 minimal medium overnight. Finally, the transposants were grown overnight in LB (pH 8.0) supplemented with erythromycin and then frozen in 20% (vol/vol) glycerol in 96-well plate format.

Luciferase reporter library screen.

Overnight cultures of the mini-Tn5 mutant library in 96-well plates were grown at 37°C in 5.0% CO2. A volume of 200 μl of LB medium supplemented with 5 mM EGTA and 15 mM MgSO4 was accurately pipetted into each well of a sterile 96-well clear-bottom, white-walled plate (number 3632; Corning). A sterilized 96-metal-pin well replicator (V&P Scientific) was used to sample the overnight 96-well plate cultures, and then the replicator was used to inoculate each well of the 96-well plate supplemented with LB medium. These plates were incubated with shaking at 30°C and 250 rpm for 3.5 h. Luminometry (counts per second, read at 1 s per well) and OD600 endpoint readings were taken using a Victor X5 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Statistical binning to categorize transposon mutants.

To narrow mutants down to a reasonable number for genetic characterization, we undertook a statistical binning approach. All mutants that fell below 1,000 cps and above an OD600 of 0.4 were binned according to their counts per second into three categories: low glowers (less than 100 cps), low-moderate glowers (100 to 200 cps), and moderate glowers (200 to 1,000 cps). Statistical means and standard deviations were calculated for each group, and mutants that fell 1 standard deviation below the mean for each group were selected for characterization. These data are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Genetic marker retrieval.

Genomic DNA from selected V. parahaemolyticus transposants was isolated and restriction enzyme digested to completion using HhaI, followed by a heat inactivation of HhaI. The digested DNA (final concentration of approximately 40 ng/μl) was then treated with T4 DNA ligase overnight. Finally, the ligated DNA was transformed into E. coli DH5αλpir using a standard procedure, and transformants containing self-replicating plasposons were selected on erythromycin LB agar medium. The plasposons were retrieved from the E. coli hosts using a standard miniprep procedure and were subjected to Sanger sequencing using the M13 forward sequencing primer. The sequencing data were compared to the RIMD2210633 reference V. parahaemolyticus genome to identify the genetic locus were transposition had occurred.

Protein secretion assays.

T3SS-1 protein secretion assays were performed as previously described (35). Culture conditions that support T3SS-1 expression were a starting OD600 of 0.025 in LB supplemented with 15 mM MgSO4 and 5 mM EGTA and a 4-h incubation at 30°C (250 rpm).

Cytotoxicity assays.

HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco 11995) supplemented with fetal bovine serum, seeded in a sterile 24-well plate (number 3526; Costar) at a density of 105 cells/ml, and incubated for 16 h at 37°C in 5.0% CO2 prior to infection. The HeLa cells were washed twice with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.46 mM KH2PO4) before infection with selected V. parahaemolyticus strains. V. parahaemolyticus strains were cultured overnight in LB broth at 37°C and 200 rpm. The cultures were diluted in PBS and adjusted for cell number using OD600 measurement and then transferred to phenol red-free DMEM (Gibco 21063) (without serum), resulting in bacterial suspensions of ∼5 × 105 cells/ml. One milliliter of the relevant suspension was added to the appropriate wells of a HeLa cell-seeded 24-well plate for a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 5 (verified by viable plate counts). Uninoculated DMEM was added to wells containing the uninfected HeLa cells and the maximal LDH release condition controls. The 24-well plate was incubated for 4 h at 37°C and 5.0% CO2. A cytotoxicity kit (88954; Pierce) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following formula was used to calculate percent cytotoxicity: (experimental OD490 − uninfected OD490)/(maximal release OD490) × 100.

Construction of a recombinant plasmid to overexpress and purify HlyU-His.

Primers NT400 and NT401 were used in a PCR with V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNA to amplify the hlyU open reading frame without its stop codon. The resulting DNA fragment was digested with NdeI and XhoI and then cloned into the corresponding restriction sites within pET21a+ (Novagen), thus creating an in-frame fusion to a hexahistidine coding sequence (C-terminal His tag). The recombinant plasmid was initially transformed into DH5α and DNA sequence verified. Finally, the plasmid was moved into E. coli BL21(λDE3) for HlyU-His protein overexpression using a T7 inducible promoter system.

Overexpressed HlyU-His was purified from the soluble fraction of bacterial lysates using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA)–agarose (Qiagen) and column chromatography as previously described (46). Extensively washed and purified HlyU-His was eluted from columns using an elution buffer (10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM phosphate buffer).

EMSA.

The electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as previously described (47), with a few minor modifications. Purified HlyU-His or BSA (B9000S; New England BioLabs) was mixed with a PCR-amplified exsA promoter DNA fragment in binding buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5 at 20°C], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 M KCl, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 5%, vol/vol, glycerol, 0.01 mg ml−1 BSA). A PCR-amplified nleH1 gene fragment (derived from EPEC genomic DNA) served as an unrelated nonspecific DNA control. Six percent Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE)–polyacrylamide gels were prerun with 1.5 μl of 6× TBE loading dye (6 mM Tris, 0.6 mM EDTA, 30%, vol/vol, glycerol, 0.0006%, wt/vol, bromophenol blue, 0.0006%, wt/vol, xylene cyanol FF) and then loaded with the equilibrated protein-DNA samples. The gel was run for 4 h (100 V, 4°C) and then stained with SYBR green fluorescent DNA dye (Invitrogen) at a 1× concentration in TBE buffer and imaged using a VersaDoc MP5000 system (Bio-Rad). Protein staining and processing of TBE gels was performed using SYPRO Ruby Red (Bio-Rad) as previously described (48) and then imaged using a VersaDoc MP5000 system (Bio-Rad).

6-FAM DNase I footprinting assay.

A 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-end-labeled exsA promoter fragment was amplified by PCR using V. parahaemolyticus genomic DNA as the template with primers NT337 and NT402. Using the same EMSA binding conditions, the 6-FAM-labeled exsA promoter PCR product was mixed with purified HlyU-His or BSA and allowed to equilibrate for 30 min. Various amounts of DNase I (0.5 to 2 U) were added to the protein-DNA mixture, followed by immediate incubation at 37°C for 20 min. To stop DNase I activity, reaction mixtures were rapidly heated to 75°C for 10 min and then purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The samples were then subjected to capillary electrophoresis on an ABI-3730XL DNA Analyzer (Genome Québec Innovation Center). The chromatogram from this analysis was matched with a Sanger DNA sequencing reaction of the same exsA promoter DNA fragment. The HlyU-His protected region was identified by searching the chromatogram for a region with decreased 6-FAM fluorescence output. This experiment was repeated four times and included independent binding and DNase I digestion reactions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Aaron Liu, Courtney Nieforth, and Divya Thomas for technical assistance. Rosalie Fréchette, at the Genome Québec Innovation Center, assisted with troubleshooting the DNase I footprinting assay.

This work was supported by an operating grant (RGPIN/342111-2013) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00653-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ceccarelli D, Hasan NA, Huq A, Colwell RR. 2013. Distribution and dynamics of epidemic and pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus virulence factors. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:97. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton AE, Garrett N, Stroika SG, Halpin JL, Turnsek M, Mody RK. 2014. Increase in Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections associated with consumption of Atlantic Coast shellfish—2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:335–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung PS, Boor KJ. 2004. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of foodborne Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections. Foodborne Pathog Dis 1:74–88. doi: 10.1089/153531404323143594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Stine OC, Badger JH, Gil AI, Nair GB, Nishibuchi M, Fouts DE. 2011. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: serotype conversion and virulence. BMC Genomics 12:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo H, Tinwongger S, Proespraiwong P, Mavichak R, Unajak S, Nozaki R, Hirono I. 2014. Draft genome sequences of six strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from early mortality syndrome/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease shrimp in Thailand. Genome Announc 2:e00221-. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00221-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CT, Chen IT, Yang YT, Ko TP, Huang YT, Huang JY, Huang MF, Lin SJ, Chen CY, Lin SS, Lightner DV, Wang HC, Wang AH, Hor LI, Lo CF. 2015. The opportunistic marine pathogen Vibrio parahaemolyticus becomes virulent by acquiring a plasmid that expresses a deadly toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:10798–10803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503129112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng W, Marshall NC, Rowland JL, McCoy JM, Worrall LJ, Santos AS, Strynadka NCJ, Finlay BB. 2017. Assembly, structure, function and regulation of type III secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:323–337. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makino K, Oshima K, Kurokawa K, Yokoyama K, Uda T, Tagomori K, Iijima Y, Najima M, Nakano M, Yamashita A, Kubota Y, Kimura S, Yasunaga T, Honda T, Shinagawa H, Hattori M, Iida T. 2003. Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae. Lancet 361:743–749. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12659-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Wong HC, Nong W, Cheung MK, Law PT, Kam KM, Kwan HS. 2014. Comparative genomic analysis of clinical and environmental strains provides insight into the pathogenicity and evolution of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. BMC Genomics 15:1135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchie JM, Rui H, Zhou X, Iida T, Kodoma T, Ito S, Davis BM, Bronson RT, Waldor MK. 2012. Inflammation and disintegration of intestinal villi in an experimental model for Vibrio parahaemolyticus-induced diarrhea. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002593. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiyoshi H, Kodama T, Saito K, Gotoh K, Matsuda S, Akeda Y, Honda T, Iida T. 2011. VopV, an F-actin-binding type III secretion effector, is required for Vibrio parahaemolyticus-induced enterotoxicity. Cell Host Microbe 10:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarbrough ML, Li Y, Kinch LN, Grishin NV, Ball HL, Orth K. 2009. AMPylation of Rho GTPases by Vibrio VopS disrupts effector binding and downstream signaling. Science 323:269–272. doi: 10.1126/science.1166382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broberg CA, Zhang L, Gonzalez H, Laskowski-Arce MA, Orth K. 2010. A Vibrio effector protein is an inositol phosphatase and disrupts host cell membrane integrity. Science 329:1660–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.1192850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ono T, Park KS, Ueta M, Iida T, Honda T. 2006. Identification of proteins secreted via Vibrio parahaemolyticus type III secretion system 1. Infect Immun 74:1032–1042. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1032-1042.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda S, Okada N, Kodama T, Honda T, Iida T. 2012. A cytotoxic type III secretion effector of Vibrio parahaemolyticus targets vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit c and ruptures host cell lysosomes. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002803. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higa N, Toma C, Koizumi Y, Nakasone N, Nohara T, Masumoto J, Kodama T, Iida T, Suzuki T. 2013. Vibrio parahaemolyticus effector proteins suppress inflammasome activation by interfering with host autophagy signaling. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003142. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shime-Hattori A, Iida T, Arita M, Park KS, Kodama T, Honda T. 2006. Two type IV pili of Vibrio parahaemolyticus play different roles in biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 264:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang R, Zhong Y, Gu X, Yuan J, Saeed AF, Wang S. 2015. The pathogenesis, detection, and prevention of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front Microbiol 6:144. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y, Fang L, Zhang Y, Sheng H, Fang W. 2015. VgrG2 of type VI secretion system 2 of Vibrio parahaemolyticus induces autophagy in macrophages. Front Microbiol 6:168. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, Shah DH, Konkel ME, Call DR. 2008. Type III secretion system 1 genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus are positively regulated by ExsA and negatively regulated by ExsD. Mol Microbiol 69:747–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J, Tauschek M, Robins-Browne RM. 2011. Control of bacterial virulence by AraC-like regulators that respond to chemical signals. Trends Microbiol 19:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King JM, Schesser Bartra S, Plano G, Yahr TL. 2013. ExsA and LcrF recognize similar consensus binding sites, but differences in their oligomeric state influence interactions with promoter DNA. J Bacteriol 195:5639–5650. doi: 10.1128/JB.00990-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vakulskas CA, Brady KM, Yahr TL. 2009. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExsA. J Bacteriol 191:6654–6664. doi: 10.1128/JB.00902-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimenez R, Cruz-Migoni SB, Huerta-Saquero A, Bustamante VH, Puente JL. 2010. Molecular characterization of GrlA, a specific positive regulator of ler expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 192:4627–4642. doi: 10.1128/JB.00307-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wattiau P, Cornelis GR. 1994. Identification of DNA sequences recognized by VirF, the transcriptional activator of the Yersinia yop regulon. J Bacteriol 176:3878–3884. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.3878-3884.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyell NL, Dunn AK, Bose JL, Vescovi SL, Stabb EV. 2008. Effective mutagenesis of Vibrio fischeri by using hyperactive mini-Tn5 derivatives. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:7059–7063. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01330-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukherjee D, Pal A, Chakravarty D, Chakrabarti P. 2015. Identification of the target DNA sequence and characterization of DNA binding features of HlyU, and suggestion of a redox switch for hlyA expression in the human pathogen Vibrio cholerae from in silico studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43:1407–1417. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mou X, Spinard EJ, Driscoll MV, Zhao W, Nelson DR. 2013. H-NS is a negative regulator of the two hemolysin/cytotoxin gene clusters in Vibrio anguillarum. Infect Immun 81:3566–3576. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00506-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Mou X, Nelson DR. 2011. HlyU is a positive regulator of hemolysin expression in Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol 193:4779–4789. doi: 10.1128/JB.01033-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu M, Alice AF, Naka H, Crosa JH. 2007. The HlyU protein is a positive regulator of rtxA1, a gene responsible for cytotoxicity and virulence in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun 75:3282–3289. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00045-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams SG, Attridge SR, Manning PA. 1993. The transcriptional activator HlyU of Vibrio cholerae: nucleotide sequence and role in virulence gene expression. Mol Microbiol 9:751–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kodama T, Yamazaki C, Park KS, Akeda Y, Iida T, Honda T. 2010. Transcription of Vibrio parahaemolyticus T3SS1 genes is regulated by a dual regulation system consisting of the ExsACDE regulatory cascade and H-NS. FEMS Microbiol Lett 311:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu M, Rose M, Crosa JH. 2011. Homodimerization and binding of specific domains to the target DNA are essential requirements for HlyU to regulate expression of the virulence gene rtxA1, encoding the repeat-in-toxin protein in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. J Bacteriol 193:6895–6901. doi: 10.1128/JB.05950-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park KS, Ono T, Rokuda M, Jang MH, Okada K, Iida T, Honda T. 2004. Functional characterization of two type III secretion systems of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infect Immun 72:6659–6665. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6659-6665.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarty D, Baker NT, Thomson EL, Rafuse C, Ebanks RO, Graham LL, Thomas NA. 2012. Characterization of the type III secretion associated low calcium response genes of Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633. Can J Microbiol 58:1306–1315. doi: 10.1139/w2012-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu M, Naka H, Crosa JH. 2009. HlyU acts as an H-NS antirepressor in the regulation of the RTX toxin gene essential for the virulence of the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus CMCP6. Mol Microbiol 72:491–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoebel DM, Free A, Dorman CJ. 2008. Anti-silencing: overcoming H-NS-mediated repression of transcription in Gram-negative enteric bacteria. Microbiology 154:2533–2545. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navarre WW, McClelland M, Libby SJ, Fang FC. 2007. Silencing of xenogeneic DNA by H-NS-facilitation of lateral gene transfer in bacteria by a defense system that recognizes foreign DNA. Genes Dev 21:1456–1471. doi: 10.1101/gad.1543107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner EC, Dorman CJ. 2007. H-NS antagonism in Shigella flexneri by VirB, a virulence gene transcription regulator that is closely related to plasmid partition factors. J Bacteriol 189:3403–3413. doi: 10.1128/JB.01813-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez LC, Banda MM, Fernandez-Mora M, Santana FJ, Bustamante VH. 2014. HilD induces expression of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 genes by displacing the global negative regulator H-NS from ssrAB. J Bacteriol 196:3746–3755. doi: 10.1128/JB.01799-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winardhi RS, Gulvady R, Mellies JL, Yan J. 2014. Locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded regulator (Ler) of pathogenic Escherichia coli competes off histone-like nucleoid-structuring protein (H-NS) through noncooperative DNA binding. J Biol Chem 289:13739–13750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.545954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorman CJ. 2004. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun F, Zhang Y, Qiu Y, Yang H, Yang W, Yin Z, Wang J, Yang R, Xia P, Zhou D. 2014. H-NS is a repressor of major virulence gene loci in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front Microbiol 5:675. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saha RP, Chakrabarti P. 2006. Molecular modeling and characterization of Vibrio cholerae transcription regulator HlyU. BMC Struct Biol 6:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunn AK, Millikan DS, Adin DM, Bose JL, Stabb EV. 2006. New rfp- and pES213-derived tools for analyzing symbiotic Vibrio fischeri reveal patterns of infection and lux expression in situ. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:802–810. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.802-810.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas NA, Deng W, Baker N, Puente J, Finlay BB. 2007. Hierarchical delivery of an essential host colonization factor in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 282:29634–29645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hellman LM, Fried MG. 2007. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for detecting protein-nucleic acid interactions. Nat Protoc 2:1849–1861. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomassin JL, He X, Thomas NA. 2011. Role of EscU auto-cleavage in promoting type III effector translocation into host cells by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol 11:205. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards RA, Keller LH, Schifferli DM. 1998. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207:149–157. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macritchie DM, Ward JD, Nevesinjac AZ, Raivio TL. 2008. Activation of the Cpx envelope stress response down-regulates expression of several locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded genes in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 76:1465–1475. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01265-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.