Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to translate, adapt and validate the Kessler 10-item questionnaire (K10) for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

Narail district, Bangladesh.

Participants

A random sample of 2425 adults of age 18–90 years was recruited.

Outcome measure

Validation of the K10 was the major outcome. Sociodemographic factors were measured to assess if the K10 needed adjustment for factors such as age or gender. The Rasch measurement model was used for the validation, and RUMM 2030 and SPSS V.24 software were used for analyses.

Results

Initial inspection of the total sample showed poor overall fit. A sample size of 300, which is more satiated for Rasch analysis, also showed poor overall fit, as indicated by a significant item–trait interaction (χ2= 262.27, df=40, p<0.001) and item fit residual values (mean=–0.25, SD=2.49). Of 10 items, five items were disordered thresholds, and seven items showed misfit, suggesting problems with the response format and items. After removing three items (‘feel tired’, ‘depressed’ and ‘worthless’) and changing the Likert scale categories from five to four categories, the remaining seven items showed ordered threshold. A revised seven-item scale has shown adequate internal consistency, with no evidence of multidimensionality, no differential item functioning on age and gender, and no signs of local dependency.

Conclusions

Analysis of the psychometric validity of K10 using the Rasch model showed that 10 items are not appropriate for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. A modified version of seven items (K7) with four response categories would provide a psychometrically more robust scale than the original K10. The study findings suggest repeating the K7 version in other remote areas for further validation can substantiate an efficient screening tool for measuring psychological distress among the general Bangladeshi population.

Keywords: phychological distress, rasch analysis, validation, kessler psychological distress scale, rural Bangladesh, item response theory

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides the first reliable data on the Kessler 10-item (K10) questionnaire from a general population of a typical rural district in Bangladesh.

This study used numerous primary data on K10 and associated covariates.

The data were collected through face-to-face interviews of people from a typical rural district that generally represents Bangladesh.

The sophisticated Rasch analysis technique was applied to validate as well as identify a suitable unidimensional structure of the K10. The study provides a unique opportunity to assess psychological distress in a rural population of Bangladesh.

The potential drawback of this study is that it is based on a single-occasion collection of data from a rural district in Bangladesh. While we have attempted to capture the situation in the Narail district, the study needs to be repeated in a random sample of other rural districts to be truly representative of the national population.

Introduction

A high prevalence of psychological distress is recognised worldwide.1 Psychological distress is associated with chronic diseases and other health-related problems,2 and early diagnosis is seen as an important measure to ensure effective and targeted intervention.3 In recent years, epidemiological studies have attempted to employ short dimensional scales to effectively measure and monitor the extent of psychological distress in the general community for the purposes of early diagnosis.4 The Kessler 10-item questionnaire (K10) is one such scale among similar tools, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),5 the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)6 and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS),7 which are designed to assess non-specific psychological distress and screen for common psychiatric disorders.8–11

The K10 was developed in 1992 by Kessler and Mroczek12 to be used in the US National Health Interview Survey as a brief measure of non-specific psychological distress along the anxiety-depression spectrum. The K10 comprises 10 questions (rated on 5-point Likert-type scales, where 1=none of the time to 5=all of the time) about psychological distress. Although K10 is not a diagnostic tool, it does indicate psychological distress and is used to identify people in need of further assessment for anxiety and depression. The K10 measurement of a client’s psychological distress levels can also be used as an outcome measure and assist treatment planning and monitoring.13 In the context of the general population, there is often a shortage of space for the inclusion of more items in the scale. The BDI (21 items),5 HADS (14 items)6 and the DASS (42 items)7 are limited as screening tools because of their long list of items. Moreover, studies confirm that well-constructed short scales can be as strong predictors as the more lengthy instruments or interviews.12 14 Because of its small number of items, the K10 has, since its development, been widely used in many countries, including the USA, Canada and Australia. The tool has also being adopted in WHO’s World Mental Health Survey.8–11 15 Moreover, another advantage of the K10 is that it was developed using methods associated with the item response theory (IRT).15

Although the K10 was originally developed to identify levels of non-specific psychological distress in the general population, the tool has also demonstrated a strong relationship with severe mental illnesses as defined by structured diagnostic interviews.16 As such, clinicians have been encouraged to use the K10 to screen for psychiatric illness.17 18 Further, the K10 has been used as a routine outcome measure in specialist public mental health services in multiple Australian states and territories.4 A recent review of the literature suggests that the K10 is an effective and reliable assessment tool applicable to a variety of settings and cultures for detecting the risk of clinical psychological disorders.19 20 However, a major limitation of the K10 is the lack of consistency across studies about its factor structure. Although it was initially designed to yield a single score indicating the level of psychological distress,15 one study demonstrated a four-factor model with acceptable fit in large community samples21; another study proposed a two-factor solution, one factor for depression and another for anxiety4; while another study did not find an adequate fit.22

Bangladesh is a country of 163 million people23 where mental health complaints are a major public health concern, especially in rural areas.24–26 The prevalence of mental disorders in such areas varies between 6.5% and 31%, possibly due to the use of different protocols and definitions of mental disorders.27 A culturally validated tool is needed for quick screening of psychological distress in Bangladesh, as well as in other countries with similar socioeconomic conditions. Due to lack of published research on the K10 in rural settings, and uncertainties surrounding the scale noted above, we need to develop a valid measurement scale of psychological distress in Bangladesh.

The present study pursues an update of Rasch analysis technique to evaluate the suitability of the K10 for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh, and to provide guidance on suitable modification to the instrument to improve its performance. Accuracy and precision of K10 scores can lead to a more efficient allocation of healthcare resources as well as more efficient screening of psychological distress among the rural population.

Materials and methods

Study population

Participants were recruited from the Narail district, located approximately 200 km Southwest of Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. We recruited a total of 2425 adults aged 18–90 years, from May to July 2017. The study protocol, including its geographical location and population density, is described in detail elsewhere.28

Sample size and statistical power

A sample of approximately 300 is more suitable for a Rasch analysis, because large sample sizes can result in type 1 errors that falsely reject an item for not fitting in the Rasch model.29 A sample size of 300 is considered large enough for 99% confidence that the estimated item difficulty would be within ±½ logit of its stable value.30 We did the analysis of five times with five different random sample sizes of 300 each, from the total sample of 2425, to check the robustness of the models using different subsamples. For the initial test of the model, we also used the total sample.

Sampling frame

A multilevel cluster random sampling technique was used for this cohort study. Out of 13, three unions (smallest rural administrative unit) and one pourashava (smallest urban administrative unit) of Narail Upazilla (the third largest type of administrative division in Bangladesh) were randomly selected at level 1. Two to three villages (a smallest territorial and social unit for administrative and representative purposes), from each selected union and two wards (an electoral district, for administrative and representative purposes) were randomly chosen from selected pourashava at the second level. In total, 150 adults (18–59 years) and 120 older adults (60–90 years) from each of the villages/wards were interviewed. Recruitment strategy and quality assurance in data collection are described previously.28

Patient and public involvement

Our study participants are the general people with or without any particular disease. There was a public involvement in conducting the research including informing the district commissioner, district police super, civil surgeon and the public representatives such as the chairman of the union parishad. We conducted a pilot survey and arranged a focus group discussion regarding the understanding of the questionnaire by the general people.

Recruitment strategy was reported in the protocol paper.28 To maintain an approximately equal number of male and female participants, one female was interviewed immediately after a male participant. Participants did not involve in the recruitment to and conduct of the study. Although the results are being published in peer-reviewed journals, the results will be disseminated via community briefs and presentations at national and international conferences. However, the participants those will be identified with severe psychological depressed, the Organisation for Rural Community Development intends to refer them to the psychologists for their treatment. This is also plan to use the modified version of the questionnaire for mass scale screening programme for measuring psychological distress.

Kessler psychological distress scale

The K10 measures how often participants have experienced symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders in the previous 4 weeks prior to screening.12 Respondents were asked, ‘During the past 4 weeks, how often did you feel: (1) tired out for no good reason; (2) nervous; (3) so nervous that nothing could calm you down; (4) hopeless; (5) restless or fidgety; (6) so restless you could not sit still; (7) sad or depressed; (8) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up; (9) everything was an effort; (10) worthless.’ Items are rated on a five-point ordinal scale: all of the time (score 5), most of the time (score 4), some of the time (score 3), a little of the time (score 2) and none of the time (score 1). Questions 3 and 6 are not asked if the preceding question was answered ‘none of the time’, in which case questions 3 and 6 would automatically receive a score of 1. Scores for the10 questions are summed: the maximum score is 50, indicating severe distress; the minimum score is 10 indicating no distress. Low scores indicate low levels of psychological distress and high scores indicate higher levels of psychological distress.12

Outcome variables

The main outcome measure was the validation of the K10.

Factor variables of differential item functioning

Participants were categorised as either adults (18–59 years) or older adults (60–90 years), and by gender (male or female).

Scale validation

IRT and classical test theory (CTT).

Item response theory

IRT is a paradigm for the design, analysis and scoring of tests, questionnaires and similar instruments measuring abilities, attitudes or other variables.31 It is based on the relationship between individuals’ performances on a test item and their personal performance on an overall measure of the ability that the item seeks to quantify.32 All IRT models attempt to explain observed (actual) item performance as a function of an underlying ability (unobserved) or latent trait.

Classical test theory

CTT is a quantitative approach to testing the reliability and validity of a scale based on its items. CTT is a simple linear model which links the observable score (X) to the sum of two unobservable (often called latent) variables, true score (T) and error score (E), that is, X=T+E. Because of each examinee, there are two unknowns, without simplified assumption the equation will not be solved. The assumptions in the classical test model are that (1) true scores and error scores are uncorrelated, (2) the average error score in the population of examinees is 0 and (3) error scores on parallel tests are uncorrelated.33 The true score (T) is defined as the expected value of the observed score over an infinite number of repeat administrations of the same instrument.33 34

Rationale for using the Rasch analysis instead of the CTT

Similar to the IRT, the CTT is another fundamental measurement theory that researchers employ to construct measures of latent traits. Both IRT and CTT can be used to construct measures of latent traits, but the two measurement systems are entirely dissimilar. A more in-depth explanation of the literature on CTT35–37 and IRT.38–41 So far, the K10 was validated mostly using CTT in which the items and the latent trait being measured are considered separately and, therefore, cannot be meaningfully and systematically compared.42 43 These limitations can be solved rationally using Rasch modelling.38 39 44–46

The Rasch model

The Rasch model was named after the Danish mathematician Rasch.47 The model shows what should be expected of responses to items if measurement (at the metric level) is to be achieved. Two versions of the Rasch model are available:

dichotomous,

47;

and polytomous,

48;

where is the location of person n and is the location of item i., 1, 2, … are thresholds which partitioned the latent continuum of item i into + 1 ordered categories. X is the response value that qualifies the expression by .

The Rasch analysis in this study was conducted using the RUMM 2030 package.49 In the assessment of K10, respondents were presented with the 10-item questionnaire regarding psychological distress. The purpose of the Rasch analysis was to maximise the homogeneity of the trait and to allow more significant reduction of redundancy without sacrificing the measurement of information by decreasing items and scoring levels to yield a more valid and straightforward measure. The Rasch model requires some assumptions that need to be evaluated to ensure that an instrument has Rasch properties. The Rasch assumptions most commonly assessed are (1) unidimensionality, (2) local independence and (3) invariability.

χ2 item–trait interaction statistics define the overall fit of the model for the scale.50 A non-significant χ2 probability value indicated that the hierarchical ordering of the items is consistent across all levels of the underlying trait. A Bonferroni adjustment51 is typical of the alpha value used to assess statistical significance, by dividing the alpha value of 0.05 by the number of items in the scale. Item–person interaction statistics distributed as z-statistic with a mean of 0 and SD of 1 (indicating perfect fit with the model). Values of SD above 1.5 for either items or person suggest a problem. Individual item fit statistics are presented as residuals (acceptable within the range ±2.5) and χ2 statistic (require a non-significant χ2 value).

The Rasch model can be extended to analyse items with more than two response categories, which involves a ‘threshold’ parameter, represented by the two response categories where either response is probable. Common sources of item misfit occur with ‘disorder thresholds’ failure of the respondents to use the response category in a manner consistent with the level of the trait being measured.

Unidimensionality occurs when a set of items measures just one thing in common.52 To establish this, the first step is to run a principal component analysis (PCA) on the residuals to identify two subsets of the items having the most difference. Second, the items loading on the first factor are extracted, items having positive and negative loadings are defined, and estimates for these two sets are derived. Applying an independent t-test to both sets, which conduct t-tests for each person in the sample comparing their score on the set 1 item and set 2 item. If less than 5% of the estimates are outside the range of ±1.96, the scale is considered unidimensional.

In case of local independence,53 the items in a test are expected to be unrelated to each other, that is, the response on each item should not be associated with that of another items. To test for local independence, we need to check the residuals correlation matrix, and any correlation coefficient value greater than 0.3 suggests the two items are locally dependent. In a situation where the correlation value is greater than 0.3, the two items need to be merged into one, called subtest analysis, to achieve a significant improvement on Person Separation Index (PSI) value. If so, it is a sign of local dependency and a violation of one of the Rasch assumptions.

Invariability indicates that ‘items are not dependent on the distribution of persons’ abilities and the persons’ abilities are not dependent on the test items.54 In Rasch measurement theory, the scale should work in the same way, irrespective of which group (eg, gender or age) is being assessed. If for some reason one gender does not display equal likelihood of confirming the item, then the items would display differential item functioning (DIF) and would violate the requirement of unidimensionality.55 DIF is an analysis of variance of the person–item deviation residuals with the person’s factors (eg, age, gender).

The reliability and internal consistency of the model are defined by the PSI.56 In addition to item fit, examination of person fit is essential. A few responses with unusual response pattern (identified by high positive residuals) may seriously affect the fit at the item level. Such aberrant response patterns occur due to unrecorded comorbidity or respondents with cognitive defects. Therefore, if some response pattern showed high positive fit residuals, removal from the analysis may make a significant difference to the scale internal construct validity.

Results

Overview of the respondents

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of both the validation and the total data sets by gender (male and female). The mean (SD, range) age of the total participant sample was 52.0 years (17, 18–90). Of the total sample, 48.5% were men, 27.6% had no formal education, 4% had at least a bachelor’s degree level of education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who were included and who were not in the current study, by gender

| Characteristic | Total n=2425 |

In validation n=300 |

||||

| Total (2425) | Male (1176) | Female (1249) | Total (300) | Male (143) | Female (153) | |

| Age groups (in years) | ||||||

| 18–59 | 1278 (52.7) | 603 (51.3) | 675 (54.0) | 172 (57.3) | 73 (51.0) | 99 (63.1) |

| 60–90 | 1147 (47.3) | 573 (48.7) | 574 (46.0) | 128 (42.7) | 70 (49.0) | 58 (36.9) |

| Education | ||||||

| No education | 671 (27.7) | 289 (24.6) | 382 (30.6) | 76 (25.3) | 37 (25.9) | 39 (24.8) |

| Primary (1–5) | 946 (39.0) | 447 (38.0) | 499 (40.0) | 124 (41.3) | 58 (40.6) | 66 (42.0) |

| Secondary (6–9) | 327 (13.5) | 146 (12.4) | 181 (14.5) | 38 (12.7) | 13 (9.1) | 25 (15.9) |

| SSC or HSC pass (10–12) | 385 (15.9) | 224 (19.0) | 161 (12.9) | 50 (16.7) | 26 (18.2) | 24 (15.3) |

| Degree or equivalent (13–16) | 96 (4.0) | 70 (6.0) | 26 (2.1) | 12 (4.0) | 9 (6.3) | 3 (1.9) |

HSC, Higher Secondary Certificate; SSC, Secondary School Certificate.

Primary analysis of the original set of 10 items and 5 response categories

K10 scores ranged from 10 to 50 with a mean of 16.7 (SD=11.3). Initial inspection of the scale with the total 2425 participants showed poor overall fit with the Rasch model, as indicated by a significant item–trait interaction (χ2=1729.89, df=40, p<0.001) and item fit residual values (mean=–0.25, SD=6.75) outside the acceptable range. Eight items were found to be misfit based on the overall fit residual values outside the range of ±2.5. Five items were found to have disordered thresholds, signifying problems with the five-point response format used for the scale. A check found multidimensionality: the model fit statistics for the five separate random subsamples of 300 each from the total participant sample produced almost identical results, indicating the results and sample selections were robust (table 2).

Table 2.

Model fit statistics for total sample and 5 random samples of 300 with all 10 items

| Initial solution | Total sample n=2425 | Sample 1 n=300 | Sample 2 n=300 | Sample 3 n=300 | Sample 4 n=300 | Sample 5 n=300 |

| Overall model fit, χ2 value | 1727.89 | 262.27 | 212.30 | 204.07 | 194.37 | 282.14 |

| df | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| P values | 0.00000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Item fit residuals (mean (SD)) | –0.25 (6.75) | 0.13 (2.49) | 0.05 (2.40) | –0.23 (2.12) | 0.11 (2.38) | –0.16 (2.64) |

| Person fit residuals (mean (SD)) | –0.29 (1.32) | –0.18 (1.24) | –0.28 (1.33) | –0.34 (1.32) | –0.30 (1.37) | –0.27 (1.32) |

| Person Separation Index | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| Coefficient alpha | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| Unidimensionality test (% that goes beyond 95% CI) | 10.3 (9.6 to 11.2) |

9.3 (6.9 to 11.8) |

11.7 (9.2 to 14.1) |

8.3 (5.9 to 10.8) |

9.0 (6.5 to 11.5) |

10.33 (7.9 to 12.8) |

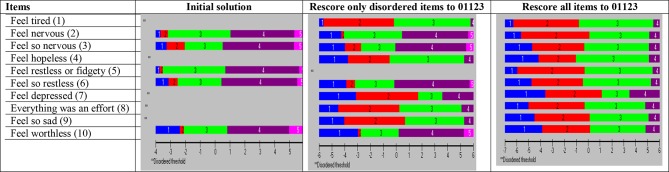

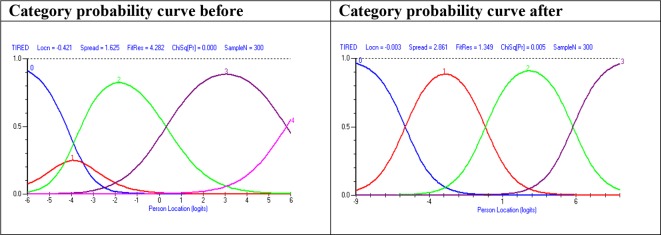

Initial inspection of scores in the random sample of 300 participants showed poor overall fit to the Rasch model (χ2=262.27, df=40, p<0.001) and items fit residual values (mean=–0.25, SD=2.49). However, the person fit residuals (mean=0.18, SD=1.24) were within the acceptable range (table 2, sample 1). Five items were found to have disordered thresholds, and seven of the individuals’ item fit statistics showed misfit, suggesting problems with the five-point response format used for the questionnaire. The value of the PSI (analogous to Cronbach’s alpha) for the original set of 10 items with 5 response categories was 0.84, indicating that the scale worked well to separate persons. The frequency distribution of the items showed (data not shown) mistargeting. Across all five items, the distribution was skewed towards the lower values, indicating low psychological distress among the respondents in the sample. Seven items (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8 and 9) showed misfit (table 3: initial solution) while five items showed disorder thresholds (1, 4, 7, 8, 9) (figure 1: initial solution). A visual examination of the threshold map shows that the estimates of the thresholds defining the categories in item 1 (tired) (figure 2: category probability curve), item 4 (feel hopeless), item 7 (depressed), item 8 (an effort) and item 9 (so sad) do not form distinctive regions of the continuum. We have examined the category probability curve of each disorder threshold item, and found response 1 and 2 adjacent categories were not the same (figure 2, category probability curve).

Table 3.

Fit statistics (location, residuals and p values) of the 10 items for the first random sample of 300

| Items | Initial solution | Rescore only disordered items to 01123* | Rescore all items to 01 123 | ||||||

| Location | Residuals | P values | Location | Residuals | P values | Location | Residual | P values | |

| Feel tired (1) | –0.42 | 4.28 | 0.000*† | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.005 | –0.51 | 1.22 | 0.000† |

| Feel nervous (2) | –0.11 | –0.85 | 0.001† | –0.56 | –1.19 | 0.004† | –0.12 | –3.26 | 0.020 |

| Feel so nervous (3) | 0.13 | –3.16 | 0.000† | –0.32 | –3.65 | 0.002† | 0.05 | –4.13 | 0.002† |

| Feel hopeless (4) | –0.06 | −0.62 | 0.008* | 0.34 | –1.54 | 0.001† | –0.03 | –1.77 | 0.104 |

| Feel restless or fidgety (5) | –0.22 | 0.46 | 0.002† | –0.69 | 0.11 | 0.001*† | –0.26 | –1.93 | 0.302 |

| Feel so restless (6) | 0.08 | –3.11 | 0.000*† | –0.38 | –3.39 | 0.007 | 0.04 | –3.73 | 0.003† |

| Feel depressed (7) | 0.26 | 3.87 | 0.000*† | 0.74 | 3.00 | 0.000† | 0.35 | 3.18 | 0.000† |

| Everything was an effort (8) | –0.15 | –0.33 | 0.125* | 0.28 | –1.90 | 0.000† | –0.16 | –2.36 | 0.301 |

| Feel so sad (9) | 0.16 | –0.48 | 0.058 | 0.65 | –2.32 | 0.001† | 0.25 | –2.64 | 0.003† |

| Feel worthless (10) | 0.34 | 1.33 | 0.001† | –0.06 | 2.41 | 0.003† | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.247 |

*Disordered items.

†P values depend on χ2 values (Bonferroni correction (p value/number of items))=0.05/10=0.005).

Figure 1.

Threshold maps of the original Kessler 10 items.

Figure 2.

Category probability curve of item ‘feel tired’ before and after rescoring.

To address the issue of disordered categories, Rasch analysis was conducted on only the disordered items, by merging the two middle categories (‘a little of the time’ and ‘some of the time’). This reduced the scoring to a four-point format from 01234 to 01123, and made the overall score range 0–40. Following this, eight misfit items were identified with significant χ2 probability values, or high positive or high negative residual values (±2.5), and found only item 5 to be disordered (table 3: only disorder items were rescored as 01123). Then we carried out all items Likert scale categories from five to four categories and found all items were ordered thresholds (figure 1: rescore all items to 01123). However, five items were still misfit in the model (table 3: rescore all items to 01123).

Proposed final analysis of the seven items and four response categories

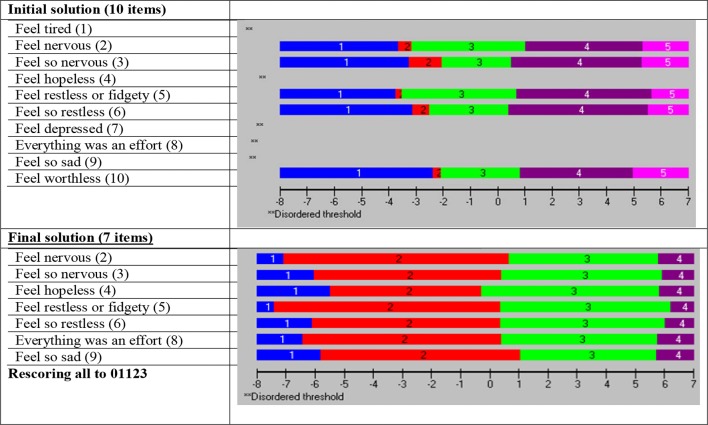

Misfit items were removed one at a time iteratively, based on positive or negative residual values as well as the degree of the significant χ2 probability values. The total model fit and individual item fit statistics were checked after each iteration, until the remaining items were shown to fit Rasch model’s expectations. The three removed items were items 1, 7 and 10.

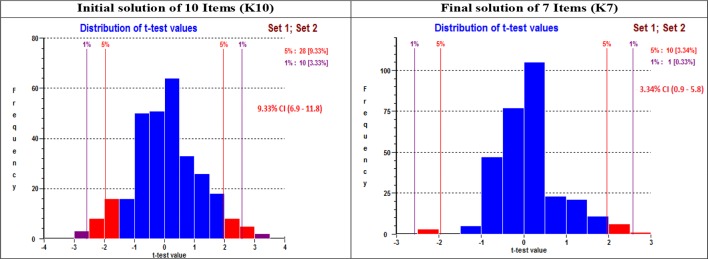

The final solution, retaining seven items, showed overall fit with the model (table 4). The PSI was found to be high (PSI=0.84), making the model suitable for individual use. The items of the K7 scale were assessed for DIF across gender (male/female) and age (adults: 18–59 years) and older adults (60–90 years) (table 5). A significant DIF was found on item 9 (feel so sad); however, using a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha value (0.05/7=0.007), the value became non-significant. In the final model, seven items with four response categories showed all items to have ordered thresholds (figure 3). There was no indication of item or person misfit (table 4: Individuals’ items fit statistics of final K7). Unidimensionality of the K7 scale was tested using PCA (3.34%, 95% CI 0.9% to 5.8%), and from a binomial distribution was found non-significant, which supports unidimensionality of the K7 (table 4, final solution of K10 and figure 4, final solution of K7). The details statistical analysis history of the K10 using Rasch analysis is shown in (online supplementary appendix).

Table 4.

Individuals’ item fit statistics of original (K10) and final 7-item model

| Items | Individuals’ items fit statistics of original K10 | Individuals’ items fit statistics of final K7 | ||||||||

| Location | SE | Residual | χ2 | P values | Location | SE | Residual | χ2 | P values | |

| Feel tired (1) | –0.42 | 0.08 | 4.28 | 46.76 | 0.000 | |||||

| Feel nervous (2) | –0.11 | 0.09 | –0.85 | 19.94 | 0.001 | –0.20 | 0.15 | –1.40 | 3.99 | 0.41 |

| Feel so nervous (3) | 0.13 | 0.09 | –3.16 | 30.36 | 0.000 | 0.10 | 0.15 | –2.66 | 11.01 | 0.03 |

| Feel hopeless (4) | –0.06 | 0.08 | –0.62 | 13.66 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 3.35 | 0.50 |

| Feel restless or fidgety (5) | –0.22 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 16.88 | 0.002 | –0.28 | 0.16 | –0.81 | 3.98 | 0.41 |

| Feel so restless (6) | 0.08 | 0.09 | –3.11 | 30.53 | 0.000 | 0.09 | 0.15 | –2.78 | 8.04 | 0.09 |

| Feel depressed (7) | 0.26 | 0.09 | 3.87 | 70.15 | 0.000 | |||||

| Everything was an effort (8) | –0.15 | 0.08 | –0.33 | 7.21 | 0.125 | –0.09 | 0.15 | –0.86 | 7.03 | 0.13 |

| Feel so sad (9) | 0.16 | 0.09 | –0.48 | 9.11 | 0.058 | 0.34 | 0.16 | –0.56 | 2.42 | 0.65 |

| Feel worthless (10) | 0.34 | 0.09 | 1.33 | 17.69 | 0.001 | |||||

| Initial solution of K10 | Final solution of K7 | |

| Overall model fit | 262.27 | 39.82 |

| df | 40 | 28 |

| P values | 0.000 | 0.068 |

| Item fit residuals (mean (SD)) | 0.13 (2.49) | –0.20 (1.20) |

| Person fit residuals (mean (SD)) | –0.18 (1.24) | –0.63 (1.40) |

| Person Separation Index | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Coefficient alpha | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| Unidimensionality test (% that goes beyond 95% CI) | 9.33 (6.9 to 11.8) | 3.34 (0.9 to 5.8) |

K7, Kessler 7-item questionnaire; K10, Kessler 10-item questionnaire.

Table 5.

Differential item functioning (DIF) on age (adults and older adults) and gender (male and female)

| Items | DIF on age | DIF on gender | ||||||

| MS | F | DF | Prob | MS | F | DF | Prob | |

| Feel nervous (2) | 0.58 | 0.88 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.59 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.34 |

| Feel so nervous (3) | 1.00 | 1.86 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.74 |

| Feel hopeless (4) | 0.07 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.78 | 2.41 | 2.59 | 1 | 0.11 |

| Feel restless or fidgety (5) | 0.49 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.66 | 0.89 | 1 | 0.35 |

| Feel so restless (6) | 0.50 | 0.92 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.98 |

| Everything was an effort (8) | 0.12 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 1 | 0.55 |

| Feel so sad (9) | 5.29 | 6.86 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 1.04 | 1 | 0.31 |

Figure 3.

Threshold maps of the original 10-item (Kessler 10) versus the final 7-item model.

Figure 4.

Dimensionality testing original 10-item (Kessler 10) versus the final 7-item model.

bmjopen-2018-022967supp001.pdf (41.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

The purpose of the paper was to evaluate the suitability of the K10-item questionnaire for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. This article examines the potential contribution of Rasch analysis in exploring several issues concerning the K10. This includes an assessment of the appropriateness of using all K10 items to represent the underlying dimension of psychological distress. In addition, the article includes an evaluation of the validity of the category scoring system, the fit of individual items and an assessment of the potential bias of items by gender and age, from the perspective of the Rasch model. The initial descriptive analysis of the frequency distributions indicated that the 10-item scale with 5 response categories mistargeted the current sample of the rural Bangladeshi population. Non-responses or very few responses in the categories may manifested to the mistargeting. Two items (‘tired’ and ‘depressed’) showed misfit, and two items (‘so nervous’ and ‘so restless’) showed redundancy (ie, little impact on the scale). Moreover, items with disordered thresholds indicating problems with the categorisation of the items and scale showed evidence of multidimensionality. Since the K10 scale has not previously undergone a rigorous psychometric analysis in rural Bangladesh and even in neighbouring countries, the detection of problems was not surprising, even though attention had been paid to targeting when the scale was constructed. In these circumstances, the analysis elaborated on taking advantage of the Rasch model.

One response category was warped, which resulted in four instead of five response categories for each item. Moreover, those items showing misfit were removed from the model gradually after going through all possible steps to improve the model. Item 1 (‘How often did you feel tired out for no good reason’) was removed because it showed high fit residuals value and DIF for age (adults and older adults). Although techniques exist for solving uniform DIF by allowing the item difficulty to vary by group, we believe that option is inappropriate because it is not useful as an everyday screening environment. Therefore, we decided to delete the biased item, which also had a large X2 value. On the other hand, the item may not play the concepts of psychological distress in Bangladesh. This could be one reason why the item works differently according to age (adults and older adults). The removal of this item from the scale improved the overall fit of the model, supporting this decision. Moreover, the item removed was one of the four items that Kessler et al 15 had earlier used to reduce 10–6 items. Item 7 (‘How often did you feel depressed’) was also removed from the scale due to misfit with the model. The large positive residual value indicates misfit in that it contributed little or no information additional to other items, as well as having a large χ2 value. However, the item showed no DIF on age and gender. Removal of the item from the model significantly improved the fit of remaining items. Moreover, the item removed was one of the four items that Kessler et al 15 earlier used to reduce 10–6 items. Item 10 (‘How often did you feel worthless’) has been removed from the scale due to high χ2 value and significant χ2 probability, as well as high positive residuals which contribute to an overall model misfit. The high χ2 value indicates that it adds nothing to the information gained by other items, and this item is the only one, which increased the overall χ2 value and made the overall model misfit. The study results support the retention of item 10.

Removal of items from the scale would eliminate at least some redundancy.57–59 However, our analysis identified that Cronbach’s alpha for the K7 (0.88) was equivalent to the original K10 Cronbach’s alpha (0.87); in addition, the PSI of K7 (0.84) was the same as that of the original K10’s PSI (0.84). A study reported by Fassaert et al 19 showed that some redundancy happens in Cronbach’s alpha, when comparing K10 (0.93) and K6 (0.89). However, our model showed superior value of Cronbach’s alpha K7 (0.88) compared with the original K10 (0.87) model, and confirms adequate fit of the model in the rural settings in Bangladesh. Although we have proposed seven validated items (K7), a previous study proposed six (K6) items17 was more robust than the K10. Of K7, five items were common in K6. We only tested K6 items using Rasch analysis and found a poor overall fit. In particular, the presence of the item ‘feel worthless’ showed a large positive fit residual and significantly large χ2 value, which influenced the overall model misfit under Rasch assumptions. Therefore, the current study found that the K7 model is more robust in our sample compared with K6.17 20

Gender differences in psychology are ubiquitous,60 so it is essential to verify whether the model is affected by gender or not. Our revised seven-item model showed no DIF on gender, that is, there is no gender bias in the revised K7 scale. The K7 scale is equally valid for men and women, which supports the previous findings reported in Australia.61 Another important factor is age, and there is inconsistency in the literature on the relationship between age and psychological distress.62 The study conducted by Kessler et al documented a good deal of inequality in the relationship between age and screening scales of depressive symptoms.63 However, other studies showed a stable non-linear association between age and psychological distress in several cross-sectional epidemiological surveys.62 64 65 Our revised model of K7 confirmed that there is no age bias (adults and older adults), and the model is equally applicable to any one between the age of 18 and 90 years.

Application of the Rasch measurement model in this study has supported the viability of a seven-item version of the K10 scale for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. The scale shows high reliability, with no disordering of thresholds and no evidence of DIF. The model also showed high PSI (0.84) and reliability (0.87), which indicated the power of the test of fit. Furthermore, there is good evidence from this sample that a single total score of psychological distress is viable. Thus, the seven-item scale appears robust when tested against the strict assumptions of the Rasch measurement model.

This paper shows how the Rasch model can be used for rigorous examination and development of measurement instruments such as the K10 psychological distress scale. The Rasch model simplifies measurement problems such as lack of invariance, which was overlooked in traditional analysis.66 The Rasch analysis of the K10 scale indicates that the psychometric properties of the original scale most likely would have been much better if scale developmental had been guided by IRT (Rasch analyses). In future, importance should be given to improving the targeting of person and items. Reducing the number of response categories as well as the number of items might also improve the properties of the scale.67 Therefore, data on the general rural population regarding psychological distress based on the revised seven-item scale from the K10, with four response categories, is superior to the original scale.

This study provides the first reliable data on levels of psychological distress among the general population of rural Bangladesh. The analysis was based on a large data set of adults and older adults across a wide range of age, from whom data were collected directly in a face-to-face interview. The Rasch analysis in this study guided a detailed examination of the structure of the scale. The response category orderings (threshold ordering) were not examined earlier, and evidence from the current study does not support the response format or the validity of the original 10-item scale.

The potential drawback of this study is that it is based on single-occasion collection of data from people in a rural district of Bangladesh. While we have attempted to capture the situation in the Narail district, the study would obviously need to be repeated in a random sample of other rural districts for the results to be truly representative of a national population.

Conclusion

Overall, the authors favour the use of K10 in rural Bangladesh, as has been used elsewhere. However, this study acknowledges that due to cultural variations and strict adherence to Rasch properties, modification is needed to measure psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. The results of this study suggest that a revised seven-item version of the K10, with four response categories, would provide a more robust psychometric scale than the original K10. The modified seven-item scale fulfils all the assumptions of the Rasch model, and the model has shown no DIF on age and sex as well as no local dependency. The study findings can be repeated using a random sample of other remote areas in Bangladesh to further validate the revised scale, as well as to better establish the level of psychological distress nationwide. The tool can be applied in clinical settings at the national level, where psychological distress has yet to be diagnosed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We particularly acknowledge the contribution of Rafiqul Islam, Sajibul Islam, Saburan Nesa and Arzan Hosen for their hard work in door-to-door data collection. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to the study participants for their voluntary participation.

Footnotes

Contributors: MNU and FMAI jointly designed the study. MNU analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. FMAI contributed to writing the manuscript. FMAI supervised the overall analyses and preparation of the manuscript. AAM reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript and read and approved its final version.

Funding: The faculty of health, arts and design of the Swinburne University Technology under the research development grant scheme, funded data collection for this research project.

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the design of the study, data collection or analysis, interpretation of data or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Human Ethics Approval was received from the Swinburne University of Technology Human Ethics Committee (SHR Project 2015/065) in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study participants provided written informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data will be available on request.

References

- 1. Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990-2020. Nat Med 1998;4:1241–3. 10.1038/3218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Egede LE. Effect of comorbid chronic diseases on prevalence and odds of depression in adults with diabetes. Psychosom Med 2005;67:46–51. 10.1097/01.psy.0000149260.82006.fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costello EJ. Early detection and prevention of mental health problems: developmental epidemiology and systems of support. J Clin Child Adolesc 2016;45:710–7. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1236728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sunderland M, Mahoney A, Andrews G. Investigating the factor structure of the kessler psychological distress scale in community and clinical samples of the Australian Population. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2012;34:253–9. 10.1007/s10862-012-9276-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beck AT, Ward CH, MENDELSON M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parkitny L, McAuley J. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS). J Physiother 2010;56:204–04. 10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70030-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andrews G, Peters L. The psychometric properties of the composite international diagnostic interview. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:80–8. 10.1007/s001270050026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:93–121. 10.1002/mpr.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kessler RMD. Final versions of our non-specific psychological distress scale. 1994 Ann Arbor (MI): Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slade T, Johnston A, Oakley Browne MA, et al. 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:594–605. 10.1080/00048670902970882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:184–9. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Slade T, Grove R, Burgess P. Kessler Psychological Distress Scale: normative data from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011;45:308–16. 10.3109/00048674.2010.543653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:783–8. 10.1007/s11606-009-0928-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76. 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health 2001;25:494–7. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, et al. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol Med 2003;33:357–62. 10.1017/S0033291702006700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2010;19 Suppl 1:4–22. 10.1002/mpr.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fassaert T, De Wit MA, Tuinebreijer WC, et al. Psychometric properties of an interviewer-administered version of the Kessler Psychological Distress scale (K10) among Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish respondents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2009;18:159–68. 10.1002/mpr.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2008;17:152–8. 10.1002/mpr.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brooks RT, Beard J, Steel Z. Factor structure and interpretation of the K10. Psychol Assess 2006;18:62–70. 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berle D, Starcevic V, Milicevic D, et al. The factor structure of the Kessler-10 questionnaire in a treatment-seeking sample. J Nerv Ment Dis 2010;198:660–4. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef1f16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bank W. Bangladesh current population. 2016. https://data.worldbank.org/country/bangladesh

- 24. Hosain GM, Chatterjee N, Ara N, et al. Prevalence, pattern and determinants of mental disorders in rural Bangladesh. Public Health 2007;121:18–24. 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Islam MM, Ali M, Ferroni P, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in an urban community in Bangladesh. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:353–7. 10.1016/S0163-8343(03)00067-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hossain MD, Ahmed HU, Chowdhury WA, et al. Mental disorders in Bangladesh: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:216 10.1186/s12888-014-0216-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Uddin MN, Bhar S, Al Mahmud A, et al. Psychological distress and quality of life: rationale and protocol of a prospective cohort study in a rural district in Bangaladesh. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016745 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith AB, Rush R, Fallowfield LJ, et al. Rasch fit statistics and sample size considerations for polytomous data. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:33 10.1186/1471-2288-8-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Linacre JM. Sample Size and Item Calibration Stability. 7, 1994:328. [Google Scholar]

- 31. May K. Fundamentals of item response theory- Hambleton, Rk, Swaminathan, H, Rogers, Hj. Appl Psych Meas 1993;17:293–4. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wise PS. Handbook of educational psychology - Berliner, DC, Calfee, RC. Contemp Psychol 1997;42:983–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lord FM, Novick MR, Birnbaum A. Statistical theories of mental test scores, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ndalichako JL, Rogers WT. Comparison of finite state score theory, classical test theory, and item response theory in scoring multiple-choice items. Educ Psychol Meas 1997;57:580–9. 10.1177/0013164497057004004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lord FM NM. Demonstration of formulae for true measurement of correlation. Am J Psychol 1907;18:161–968. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cappelleri JC, Jason Lundy J, Hays RD. Overview of classical test theory and item response theory for the quantitative assessment of items in developing patient-reported outcomes measures. Clin Ther 2014;36:648–62. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gregory RJ. Psychological testing: history, principles, and applications: Allyn & Bacon, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Birnbaum A. Some latent trait models and their use in inferring an examinee’s ability. Statistical theories of mental test scores, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bock RD. A brief history of item theory response. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 1997;16:21–33. 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1997.tb00605.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chang CH, Reeve BB. Item response theory and its applications to patient-reported outcomes measurement. Eval Health Prof 2005;28:264–82. 10.1177/0163278705278275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nguyen TH, Han HR, Kim MT, et al. An introduction to item response theory for patient-reported outcome measurement. Patient 2014;7:23–35. 10.1007/s40271-013-0041-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bartholomew D. Fundamentals of Item Response Theory - Hambleton, Rk, Swaminathan, H, Rogers, Hj. Brit J Math Stat Psy 1993;46:184–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Raykov T, Marcoulides GA. Fundamentals and models of item response theory. Introduction to Psychometric Theory 2011:269–304. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Andrich D. Controversy and the Rasch model: a characteristic of incompatible paradigms? Med Care 2004;42:I–7. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000103528.48582.7c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andrich D. Rating scales and Rasch measurement. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2011;11:571–85. 10.1586/erp.11.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andrich D. The Legacies of R. A. Fisher and K. Pearson in the application of the polytomous rasch model for assessing the empirical ordering of categories. Educ Psychol Meas 2013;73:553–80. 10.1177/0013164413477107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rasch G. An item analysis which takes individual differences into account. Br J Math Stat Psychol 1966;19:49–57. 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1966.tb00354.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika 1978;43:561–73. 10.1007/BF02293814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. RUMM2030 For analysing assessment and attitude questionnaire data [program], 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Engelhard G. Rasch models for measurement - Andrich, D. Appl Psych Meas 1988;12:435–6. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leon AC. Multiplicity-adjusted sample size requirements: a strategy to maintain statistical power with Bonferroni adjustments. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1511–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gerbing DW, Anderson JC. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J Marketing Res 1988;25:186–92. 10.2307/3172650 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tennant A, Conaghan PG. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology:what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a rasch paper? 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Institute of Medicine Institute of Medicine. Psychological testing in the service of disability determination. Washington (DC), 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smith RM. Fit analysis in latent trait measurement models. J Appl Meas 2000;1:199–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Andrich D, Sheridan B, Lyne A, et al. RUMM: a windows-based item analysis program employing Rasch unidimensional measurement models. Perth, Australia: Murdoch University, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dickens GL, Rudd B, Hallett N, et al. Factor validation and Rasch analysis of the individual recovery outcomes counter. Disabil Rehabil 2017:1–12. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1375030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McDowell J, Courtney M, Edwards H, et al. Validation of the Australian/English version of the Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale. Int J Nurs Pract 2005;11:177–84. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, et al. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol 2012;121:282–8. 10.1037/a0024780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Baillie AJ. Predictive gender and education bias in Kessler’s psychological distress Scale (k10). Soc Psych Psychiatr Epid 2005;40:743–8. 10.1007/s00127-005-0935-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kessler RC, Foster C, Webster PS, et al. The relationship between age and depressive symptoms in two national surveys. Psychol Aging 1992;7:119–26. 10.1037/0882-7974.7.1.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Feinson MC. Are psychological disorders most prevalent among older adults? Examining the evidence. Soc Sci Med 1989;29:1175–81. 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Newmann JP. Aging and depression. Psychol Aging 1989;4:150–65. 10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D Scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res 1980;2:125–34. 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fan X. Item response theory and classical test theory: an empirical comparison of their item/person statistics. Educ Psychol Meas 1998;58:357–81. 10.1177/0013164498058003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hagquist C, Bruce M, Gustavsson JP. Using the Rasch model in nursing research: an introduction and illustrative example. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:380–93. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022967supp001.pdf (41.7KB, pdf)