Abstract

Aim

The amount of injuries, illnesses and mental health problems was calculated among circus arts students, using a method designed to capture more than just time-loss and/or medical injuries. Furthermore, injury incidence rate, injury incidence proportions, anatomical injury location and severity of injuries were assessed.

Methods

A total of 44 first-year, second-year and third-year circus arts students were prospectively followed during one academic year. Every month, all students were asked to complete questionnaires by using the online Performing Artist and Athlete Health Monitor, which includes the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre Questionnaire on Health Problems.

Results

In total, 41 students completed the entire follow-up period. The response rate was 82.9%. During the academic year, all (100%) students reported a health problem. A total of 261 health problems were reported consisting of 184 injuries (70.5%), 51 illnesses (19.5%), 15 mental problems (5.0%) and 11 other health problems (3.1%). The injury incidence rate was 3.3 injuries per 1000 hours (95% CI 2.7 to 3.9). Monthly incidence proportion for substantial injuries (ie, problems leading to moderate or severe reductions in training volume or in performance or complete inability to participate in activities) ranged from 6.8% to 34.1%. Shoulder (n=51; 27.7%), lower back (n=29; 15.8%), wrist (n=26; 14.1%) and ankle (n=17; 9.2%) were the most reported injuries. The average duration of the injuries was 6.9 days (median=2.0; SD=15.0).

Conclusions

We implemented a new registration method for circus artists, which captures a complete picture of the burden of health problems in circus students. Our study showed that the burden of injuries is high in this population.

Keywords: injury, overuse, prospective

What are the findings?

Our study showed that that the burden of injuries is high in circus arts students. The injury incidence rate was 3.3 injuries per 1000 hours (95% CI 2.7 to 3.9). Monthly incidence proportion for all injuries ranged from 31.6% to 69.0% and from 6.8% to 34.1% for substantial injuries.

The new injury recording method, using the Performing Artist and Athlete Health Monitor, captures a complete picture of the burden of health problems in circus students.

Introduction

Circus arts is a discipline that is often physically very challenging for the artists.1 It combines acrobatic elements on the floor and/or in the air with dance, theatre and comedy. The artists perform frequently activities that require a high level of strength, high impact loads and extreme ranges of movement.1 The workload is often very high, with lots of performances and little time to recover. This makes artists prone to injuries. A recent review showed that only a few studies have focused on the epidemiology of injuries in circus artists.1 These studies found injury rates ranging from 7.37 to 9.7 per 1000 performances or athlete-exposures (A-Es).2–4 A-E is defined as ‘one athlete participating in one practice or competition in which he or she was exposed to the possibility of an athletic injury, regardless of the time associated with that participation.’5

Even a smaller number of studies have focused on injuries in circus arts students. In this specific target group, injuries can be highly disadvantageous, because they may lead to physical discomfort, medical treatment, absence from rehearsals and performances, study delay and even drop-out from school. Two studies on injuries included circus arts students.6 7 One of these studies reported an injury incidence of 0.3 injuries per 1000 hours.7 However, this might be an underestimation of the full extent of injury problems in circus students, because only medical attention injuries were taken into account.7 In sports, a new surveillance method was designed to address methodological challenges involved in injury registration,8 which was later adapted to record all types of health problems including non-time loss injuries, time loss injuries and illnesses.9 In comparison with standard methods of injury registration, this approach provides more information on true consequences of injuries over time.8 10 Although some athletic groups have been investigated using this new method,11 12 no studies have included circus art students. The aim of this study was to use this new method and gain more insight into the amount of health problems (ie, injuries, illnesses and mental health problems), injury incidence rate, injury incidence proportions, anatomical injury location and severity of injuries among circus arts students.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We invited all first, second and third-year students (n=44) of the Bachelor Circus Arts of Codarts Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The students are enrolled in a 4-year educational programme, resulting in a Bachelor of Arts. They study a wide range of circus disciplines, ranging from juggling to acrobatics, and choose a specialisation in their first year in which they wish to excel. Codarts School of Circus Arts is an international school in which students from more than 16 different nationalities are enrolled. All students were informed about the procedure and provided written informed consent. Our data were routinely collected for management purposes and for educational purposes and not for the purpose of this particular study. Therefore, The Dutch Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO) stated that no medical ethical approval was necessary for this questionnaire study, as stated in the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (http://www.ccmo.nl/nl/toetsingscommissie-ccmo-of-metc?55a37b93-dd8c-4bf8-8883-2d30c35ff8ba).

Procedures

At the beginning of the academic year (end of August 2016), height and body weight were recorded by the research team of Codarts Rotterdam. An intake questionnaire was administered, which included items on age, year of education and previous injuries (ie, injuries lasting at least 1 week in the previous year).

All first, second and third year students were prospectively followed during the entire 2016/2017 academic year. Students who were injured at the start of the academic year, as well as students who dropped out of the programme during the academic year (n=3), were included in the study. The time they were enrolled in the programme was taken into account in the analyses. Every month, all students were asked to complete questionnaires by using a web-based system (Performing Artist and Athletes Health Monitor (PAHM)). PAHM was developed by Codarts Rotterdam and used to monitor physical and mental health in performing artists and athletes. This system consists of several questionnaires and items (ie, visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scale; VAS stress scale; Self-Estimated Functional Inability because of Pain questionnaire;13 Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre Questionnaire on Health Problems;9 mental complaints;14 15 injury characteristics (location, history and acute or overuse onset16–18 ); items on sleep quality, mental energy, feelings and emotions, satisfaction with rehearsals and performances, taking distance and exposure (minutes spend on different activities)). Every month, students automatically received a link to the questionnaire by email. A reminder was sent to all students who did not respond on the questionnaire after 1 week.

In PAHM, the Dutch translation of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) Questionnaire on Health Problems11 12 was included. The original9 and Dutch OSRTC questionnaire11 12 consisted of four key questions on the consequences of health problems on participation, training volume and performance as well as the degree to which the student perceived symptoms. All items ranged from 0 (no problem, no reduction, no effect or no symptoms) to 25 (cannot participate at all or severe symptoms). Questions 1 and 4 were scored on a four-point scale (0–8–17–25), while questions 2 and 3 were scored on a five-point scale (0–6–13–19–25). The severity of a health problem was calculated on a scale of 0 (no health problem) to 100 (cannot participate at all due to sever health problems) by summing the score of the four questions, according to the method proposed by Clarsen and colleagues.9 If the severity score was 0, the questionnaire was finished for that month. However, if a symptom was reported, the students were asked whether they referred to a physical injury, mental problem or an illness. For physical injuries, the student was automatically directed to an injury registration form based on an international consensus statement on injury surveillance methodology for football to collect further details (eg, location, history and acute or overuse onset).16–18

Students were defined to be substantially injured if they reported problems leading to moderate or severe reductions (value ≥13 on question 2 or 3 of the OSTRC) in training volume, or moderate or severe reductions in performance or complete inability to participate in activities at least once during follow-up.8 If a student reported the same type of health problem on two or more consecutive months, this was counted as one case of a (fluctuating) problem.12

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (SPSS V.24.0), and statistical significance level was set at an alpha level >0.05. Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline characteristics of all participants using means and SD or number and percentages (%). Injury incidence rate was calculated as the number of injuries per 1000 hours spending on physical circus activities.19 The corresponding 95% CIs were obtained using the following formula: (#injuries/exposure±1.96 SE) * 1000.19 The (substantial) injury incidence proportion (IP) for one academic year was calculated by dividing the number of students that reported at least one (substantial) injury during the academic year by the number of respondents19 The (substantial) IP per month was calculated by dividing the number of students that reported at least one (substantial) injury during that month by the number of respondents in that same month. The proportion of all injuries that affect a particular body part was calculated by dividing the number to the location into the total number of injuries affecting that particular body part and multiplying it with 100, resulting in a percentage. The severity of all injuries was calculated by the mean duration in days, the median and the SD.

Results

Response and baseline characteristics

All circus students agreed to participate and were consequently included in the present study. The cohort comprised of 44 circus students (females=47.7%), the mean age was 22.0 years (2.8) and mean BMI was 22.1 kg/m2 (1.8). Fourteen first-year (31.8%), 18 second-year (40.9%) and 12 third-year (27.3%) students were included in the present study. In total, 421 questionnaires were sent to the students and 349 were completed, resulting in a response rate of 82.9%.

Health problems

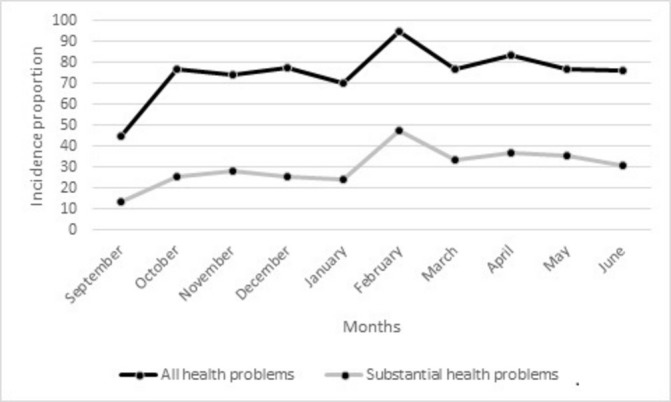

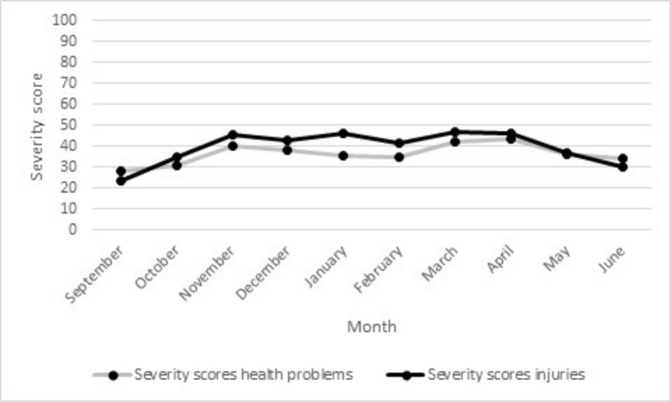

During the academic year, all (100%) students reported a health problem. In the 10 monthly questionnaires, a total of 261 health problems were reported consisting of 184 injuries (70.5%), 51 illnesses (19.5%), 15 mental problems (5.0%) and 11 other health problems (3.1%). The 44 students reported on average 5.9 (2.1) health problems during the academic year with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 10 health problems. Figure 1 shows that between 44.7% and 94.7% of the students reported a health problem on a monthly basis, and between the 13.2% and 47.4% of the students reported a substantial health problem on a monthly basis. Figure 2 shows that students with health problems reported monthly severity scores between 28.1 and 43.1.

Figure 1.

Monthly incidence proportion of all health problems and substantial health problems (X-axis: months; Y-axis: incidence proportion (percentage))

Figure 2.

Monthly average severity scores of all health problems and injuries (X-axis: months; Y-axis: severity score).

Injuries

During the academic year, 42 (95.5%) students reported in total 184 injuries. Of these, 130 were unique cases. The remaining 54 injuries were subsequent injuries. These injuries were reported in at least two consecutive questionnaires and therefore did not calculate as a unique injury.

The 14 first-year circus students and 18 second-year students spend on average 25 hours per week on physical circus activities, resulting in a total exposure of 32 000 hours during the data collection of 40 weeks. However, two second-year students dropped out of the educational programme after 4 months. Adjusting for this dropped out results in a total exposure for the first-year and second-year students of 30 800 hours. The 12 third-year students spend on average 19 hours on physical circus activities, resulting in a total exposure of 9120. However, one third-year student dropped out of the educational programme after 3 months. Adjusting for this dropped out results in a total exposure for third-year students of 8588 hours. The total exposure of all circus students was 39 388 hours. The total time equates to an injury incidence rate of 3.3 injuries per 1000 hours (95% CI 2.7 to 3.9).

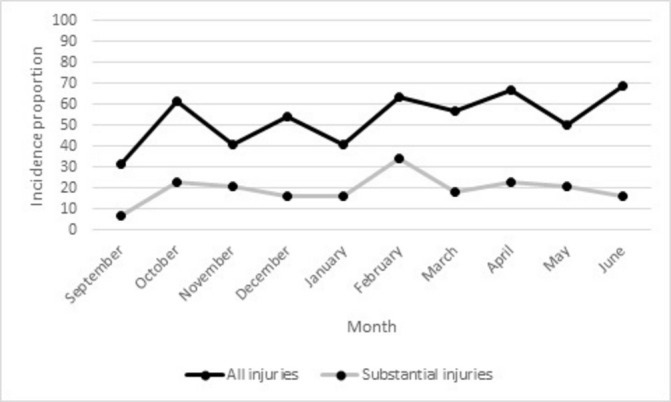

The 42 students reported on average 4.4 (1.6) injuries during the academic year with a minimum of one and a maximum of eight injuries. Figure 3 shows that the monthly incidence proportion of all injuries ranged from 31.6% to 69.0% and from 6.8% to 34.1% for substantial injuries. Figure 2 shows that students with injuries reported monthly severity scores between 23.6 and 46.1. The shoulder (n=51; 27.7%), lower back (n=29; 15.8%), wrist (n=26; 14.1%) and ankle (n=17; 9.2%) were the most reported anatomical injury locations in the 10 questionnaires. The average duration of the injuries was 6.9 days (15.0) with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 134 days. The median was 2.0 days.

Figure 3.

Monthly incidence proportion of all injuries and substantial injuries (X-axis: months; Y-axis: incidence proportion (percentage)).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the amount of health problems, injury incidence rate, injury incidence proportions, anatomic injury location and injury severity in first-year, second-year and third year circus arts students. The main findings of this study were that 44 circus students reported 261 health problems. The injury incidence rate was 3.3 injuries per 1000 hours. Monthly incidence proportion for substantial injuries ranged from 6.8% to 34.1%. Shoulder, lower back, wrist and ankle were the most reported injuries. The average duration of the injuries was 6.9 days.

Our injury incidence rate was comparable with the injuries incidence rates in Dutch talented female gymnasts (5.2 injuries per 1000 hours; 95% CI 3.9 to 7.1)11 and in Swedish talented athletes (4.1 injuries per 1000 hours of exposure to sports).20 These injury incidence were classified as high and justifies our conclusion that the burden of injuries is high in circus arts students. Futhermore, our injury incidence density is 10 times higher than the incidence density of 0.3 injuries per 1000 hours found in the study by Wanke and colleagues.7 This might be explained by the use of different injury definitions. Wanke and colleagues7 used a medical attention injury in which only physical problems that led to a consultation with a medical doctor or physiotherapist were categorised as an injury. Selecting only time-loss injuries in our dataset (answer ‘not able to participate’ on question 1, 2 or 3 of the OSTRC Questionnaire) led to a reduction in injury incidence from 3.2 to 0.4 injuries per 1000 hours of exposure to circus activities. This lower injury incidence is in agreement with the injury incidence reported by Wanke and colleagues.7

Although injury prevalence differed from other studies, the anatomic injury locations in our study were in agreement with the study of Munro.6 In our study, the majority of injuries were located at the shoulder, lower back, wrist and ankle. In the study by Munro,6 the top three anatomical areas were ankle, lumbar spine and shoulder.

Strengths of the study

One major strength of this study is the response rate of the monthly questionnaire of 82.9%. There are several reasons that might explain the high response rate. First, we used adequate guidance during the data collection to increase involvement of students and teachers. Second, we used PAHM to give students visual feedback of the collected data to improve their commitment to this study. Third, we asked for feedback from our students to improve PAHM. The feedback was incorporated in the new versions of PAHM. We recommend to use this approach when using similar registration methods.

A unique aspect of the current study is that all students were enrolled in a circus educational programme. A thorough investigation on the severity and magnitude of self-reported injury problems in this group is lacking. Although the sample size is relatively small, the presented data are accurately measured, and the response rate is high, which suggests that the results are representative for this specific target population.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we used student-reported outcomes. This methodology exposes a potential limitation. Most circus students lack medical expertise. Therefore, we were unable to record specific diagnoses for the reported injuries and profound onset mechanisms. We recommend that future studies include a follow-up from the medical staff during the data collection period to gain more insight in the injury type and aetiology.

A second limitation is that students recorded a questionnaire every month, instead of every week, as proposed by Clarsen and colleagues.8 This may have led to a slight underestimation of injuries, as students may forget a physical problem that occurred 2 weeks earlier. However, Clarsen and colleagues8 showed that the average prevalence and severity of health problems was not affected by the sampling frequency up to a frequency of one sample every 4 weeks. We therefore believe that students are able to provide reliable information about a health problem from 1 month back.

Third, the used methodology implies that the problem’s severity is constant between two recordings. It is therefore unclear at what specific day the severity of the injury was the highest. However, due to this method, the students were not overloaded with questionnaires every week, leading to a high compliance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All three authors have substantially contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by National Association of Applied Sciences SIA (grant number 2015-02-73P).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Wolfenden HE, Angioi M, Orlando C. Musculoskeletal injury profile of circus artists: a systematic review of the literature. Med Probl Perform Art 2017;32:51–9. 10.21091/mppa.2017.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Orlando C, Levitan EB, Mittleman MA, et al. The effect of rest days on injury rates. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011;21:e64–71. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shrier I, Meeuwisse WH, Matheson GO, et al. Injury patterns and injury rates in the circus arts: an analysis of 5 years of data from Cirque du Soleil. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1143–9. 10.1177/0363546508331138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamilton GM, Meeuwisse WH, Emery CA, et al. Examining the effect of the injury definition on risk factor analysis in circus artists. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2012;22:330–4. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dick R, Ferrara MS, Agel J, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men's football injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988-1989 through 2003-2004. J Athl Train 2007;42:221–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munro D. Injury patterns and rates amongst students at the national institute of circus arts: an observational study. Med Probl Perform Art 2014;29:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wanke EM, McCormack M, Koch F, et al. Acute injuries in student circus artists with regard to gender specific differences. Asian J Sports Med 2012;3:153 10.5812/asjsm.34606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clarsen B, Myklebust G, Bahr R. Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology: the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) overuse injury questionnaire. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:495–502. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarsen B, Rønsen O, Myklebust G, et al. The Oslo sports trauma research center questionnaire on health problems: a new approach to prospective monitoring of illness and injury in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:754–60. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fredriksen H, Clarsen B. High prevalence of injuries in the norwegian national ballet. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:595.3–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093494.97 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richardson A, Clarsen B, Verhagen E, et al. High prevalence of self-reported injuries and illnesses in talented female athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2017;3:e000199 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Beijsterveldt AM, Richardson A, Clarsen B, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses in first-year physical education teacher education students. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2017;3:e000189 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramel EM, Moritz U. Validation of a pain questionnaire (SEFIP) for dancers with a special created test battery. Med Probl Perform Art 1999;14:196–203. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laws H, Apps J. Fit to Dance 2: Report of the second national inquiry into dancers’ health and injury in the UK. London: Dance UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Rossum J. De mentale kant van het dansvak : van der Linden M, Wildschut L, Zeijlemaker J, Danswetenschap in Nederland - Deel 5. Amsterdam: Vereniging voor Dans Onderzoek, 2008:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuller CW, Bahr R, Dick RW, et al. A framework for recording recurrences, reinjuries, and exacerbations in injury surveillance. Clin J Sport Med 2007;17:197–200. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3180471b89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fuller CW, Molloy MG, Bagate C, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures for studies of injuries in rugby union. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:328–31. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fuller CW, Ekstrand J, Junge A, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:193–201. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.025270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knowles SB, Marshall SW, Guskiewicz KM. Issues in estimating risks and rates in sports injury research. J Athl Train 2006;41:207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. von Rosen P, Heijne A, Frohm A. High injury burden in elite adolescent athletes: a 52-week prospective stuInjury Burden in Elite Adolescent Athletes: A 52-Week Prospective Study. J Athl Train 2018;53:262–70. 10.4085/1062-6050-251-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]