Abstract

Introduction

Personal finance has been linked to wellness and resiliency; however, the level of financial literacy among residents is low. Development of a personal finance curriculum could improve the financial well‐being of trainees. The first step in this process is understanding residents’ educational needs.

Objective

The objective was to describe the financial knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of residents to inform the design of a personal finance curriculum.

Methods

A qualitative approach using semistructured interviews was used to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of residents in the realm of personal finance. Twelve residents completed interviews: one male and one female resident from the first and third years of training in the specialties of emergency medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics.

Results

Three themes were formulated and analyzed through the existing frameworks: 1) daily finances, 2) financial knowledge and experiences, and 3) approach to financial planning. Prominent subthemes included a lack of knowledge and desire for personal finance education, debt‐related anxiety, and uncertainty where to find reliable financial advice.

Conclusions

Residents report a low level of financial literacy and high interest in financial education. The framework provided in this study can inform the design of education interventions to promote financial wellness in trainees.

Despite residents facing several important financial decisions during their training and established links between financial health and resiliency,1 the level of financial literacy among trainees is low.2, 3 A survey of emergency medicine residents reported that nearly 80% did not receive any financial planning education during residency training,4 and a resident participating in a recent qualitative study on debt stated, “Just how to manage finances, I wish [we had] more. I need more.”5 In the context of increasing debt loads for medical school graduates (median debt $183,000 per recent report),6 this deficiency of personal finance knowledge is a threat to resident wellness and resiliency—both of which depend in part on financial health.1, 7, 8

Previous study within the academic medical community has correlated education debt and poor financial health with stress, burnout, and depressive symptoms.9, 10 Debt has also been identified as a factor contributing to career decisions such as medical students limiting the pool of specialties they consider11, 12, 13 and residents limiting the career paths they consider (including fellowships and academics).14, 15, 16 Additionally, debt has been cited as a factor contributing to personal life choices, such as when to start a family or buy a house.17 Although the only granular information available to date is from relatively small samples, up to 34% of trainees in Canada stated that they had less than $1,000 in their savings accounts, up to 51% paid interest charges on credit cards, and 12% had greater than $10,000 balances on their credit cards.18, 19 This evidence of the pervasive nature of debt and the stress it places on residents adds to the urgency of equipping our trainees with the knowledge, skills, and tools they need to optimize their financial well‐being.

Development of personal finance curricula could help residents navigate these challenges; however, existing examples are limited in scope and scalability2, 3, 20, 21, 22 and the appropriate content and approach for such interventions is unclear. While significant efforts have been made to characterize trainee indebtedness and its effect on attitudes,4, 5, 10, 23 literature characterizing the scope of resident needs in this area is sparse and mostly limited to quantitative surveys.4, 24, 25 This study seeks to fill this gap in the literature by qualitatively exploring the financial knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of residents to inform the design of financial education interventions.

Methods

Study Design

We chose a qualitative approach using semistructured interviews for exploratory data‐gathering of trainee knowledge and attitudes in the realm of personal finance. This method was chosen to provide freedom to explore unforeseen topics while ensuring a baseline level of investigation of target areas. This qualitative data will align with the instrument development model of mixed methods to allow further exploration of this issue on a greater scale.26 The institutional review boards of the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago approved this study.

Measurements

The interview instrument was developed iteratively by three authors (ES, JA, NA) based on existing literature, years of experience discussing personal finances with residents (ES and JA), and experience facilitating semistructured interviews (NA). The goal was to facilitate a flexible and open‐ended assessment of financial knowledge, skills, concerns, and five target areas: education debt, retirement planning, investing, disability insurance, and life insurance. These target areas represent common topics in existing literature and the experience of instrument designers; they were included in the instrument to ensure that all residents commented on each of these areas. Response process validity was established by piloting the instrument with residents not included in the study group. Adjustments were made and piloting continued until the instrument allowed for facilitation of the desired flow and depth of conversation. Three rounds of piloting and revisions were completed. There were no additional adjustments to the instrument during the study period. A copy of the final interview instrument has been provided in Data Supplement S1 (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10090/full).

Study Setting and Population

We recruited 12 residents from the University of Chicago, an urban academic medical center. Residents were recruited to include diversity in specialty, training level, and sex: one male and one female resident from each of the PGY‐1 and PGY‐3 classes from the specialties of internal medicine, emergency medicine, and pediatrics. These specialties were chosen as they represent the three largest specialty training groups.27

Study Protocol

Participants were recruited via e‐mails facilitated by program directors. Each participant received a $20 gift card for participation. To protect the identities of potential participants from the investigators, all scheduling communication, interviews, and transcriptions were conducted by one author (NA) who had previous experience conducting semistructured interviews and did not have any clinical or administrative duties related to the participants. One‐on‐one, in‐person interviews were tape‐recorded in emergency medicine administrative offices of the hospital where participants worked. Verbatim transcriptions were scrubbed of any personally identifying information before distribution to the other investigators. Saturation was defined as the lack of alteration of themes or subthemes with the coding of additional interviews. The interview period was February to March of 2017.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the constant comparative method associated with grounded theory. Two authors (ES, JA) served as coders. Both coding authors were clinicians with formal training in qualitative methods, relevant experience but no formal training in personal finance, and teaching roles in the emergency medicine residency program studied.

Transcripts were reviewed on an ongoing basis using open and axial coding. Authors coding transcripts first independently formulated themes relevant to personal finance education and then together discussed results until a consensus on final themes and subthemes was reached. These consensus themes and subthemes were used for final coding of each transcript. Results were triangulated with existing literature on resident finances.

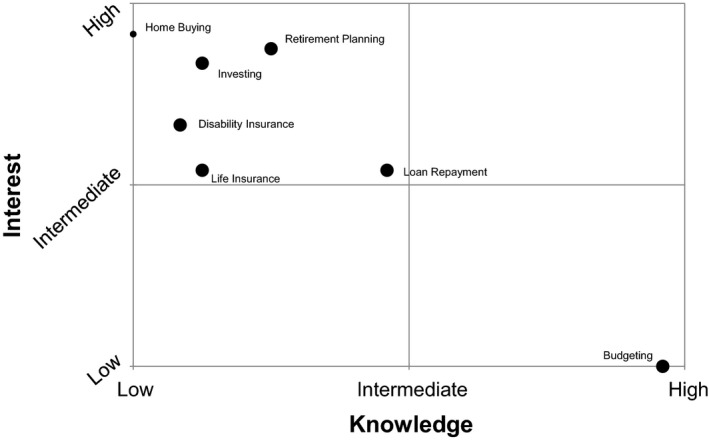

During the coding process, it was noted that subjects had different levels of knowledge and interest in certain topics. In an effort to capture and represent these findings, the authors also coded trainee knowledge and interest for each commonly discussed subject on a three‐tier scale (high, intermediate, low). For example, a resident stating: “I don't know much about [retirement planning] … I am sort of vaguely aware but not really” would be rated as “low” in the category of retirement planning knowledge. Similarly, a statement of “I could probably give a whole lecture on [student loan repayment]” would be rated as “high” in the category of loan repayment knowledge. A null value was recorded when residents did not comment on an area. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. Numerical weights were assigned to coded levels of knowledge and interest (i.e., high = 3, intermediate = 2, low = 1) to allow plotting of mean values.

Results

Three themes were formulated using the 12 interview transcripts (Table 1). Saturation was achieved after nine interviews. All 12 interviews were coded to ensure representation of each target demographic (i.e., training level, sex, and medical specialty).

Table 1.

Themes and Subthemes

| Theme | Subthemes | |

|---|---|---|

| Daily finances | Earning |

|

| Spending |

|

|

| Saving |

|

|

| Borrowing |

|

|

| Protecting |

|

|

| Knowledge and experience | Lack of comfort with knowledge and experience | |

| Desire for more knowledge | ||

| Variable levels of knowledge and interest in target topics (see Figure 1) | ||

| Approach to financial planning | Orientation |

|

| Route decision |

|

|

| Route monitoring |

|

|

| Destination recognition |

|

|

Theme 1: Daily Finances

The first theme is residents’ daily finances. These comments were found to align closely with the financial core competencies described by the United States Department of the Treasury (earning, spending, saving, borrowing, and protecting) and thus have been presented through the lens of this framework.28

Earning

Comments regarding earnings included sentiments of security with their employment (“We are fortunate to have some job security”). One prominent concern, however, was the limited cash flow available on a resident salary:

[Advice to theoretical graduating medical students]: You will not have a cash flow, so plan carefully.

[I'm] putting stuff on my credit card that I probably shouldn't … like paying for a wedding right now. Stuff I know I shouldn't be but I guess just because I am very strapped on money I have to.

Several residents commented that they used or intended to use moonlighting as a supplemental source of income to combat their limited cash flow; however, one resident lamented the sporadic nature of this source of income:

The moonlighting is not consistent [income] … I want to make sure that I am not budgeting too much with that in mind.

Spending

Residents seemed comfortable with their ability to budget; many cited budgeting wisdom and practices instilled in them early on:

From a young age I learned how not to overspend.

[I] have little money and keep careful track of it.

Comments on frugality were also common:

My general philosophy is to try to spend as little as possible.

I am a pretty frugal person.

While several residents commented on frugality, some comments on the justification of spending in spite of financial circumstances were also noted:

It's hard because we are at the end of a really long road of training and … I want to enjoy life a little bit too so … [I'm] giving myself a little bit of a reprieve right now.

This [apartment] has made us significantly happier … so I am not going to regret that.

Saving

Comments on savings, including emergency funds, suggested that residents have limited reserves:

I didn't have like a safety fund of anything.

We are not that many disasters away from just not being able to make it month to month, even with our reserves.

Similar to savings for emergencies, many residents suggested that they did not have retirement funds and/or expressed concerns regarding a late start in contributing to these funds:

I don't know much about [retirement planning] … I am sort of vaguely aware but not really.

[My spouse and I] worry about that, [whether] we started early enough.

Borrowing

One of the most prominent subthemes was that of debt‐related stress and anxiety. A strong sentiment within this subtheme was concern about the ability to repay the balance of their loans:

Loans from all of medical school…probably stress me out the most.

I just have a ton of debt … I can't pay that off in a reasonable amount of time.

It's just the looming large number.

Several residents also expressed specific concerns about the potential discontinuation of the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program:

There is talk about limiting the amount they forgive … [or] they are going to get rid of it. So that scares me because then I will be in debt forever and ever.

I am not going to put all my eggs in one basket because who knows if the [PSLF] money will be there in the end.

Some expressed regret over borrowing, including both the choice to go to medical school and the medical school that they chose:

I am not sure I would redo the whole medical school and residency if I knew what the cost would be.

Sometimes you wonder things like “Should I have tried to apply to more med schools where I could get more money and scholarships?”

A few others expressed satisfaction with borrowing; one as a means to a profession and another with their purposeful minimization of debt in their choice of schools:

I love what I am doing … this is a good investment long‐term I hope.

I went to a much cheaper college … and then when I went to med school I kind of made a … financially motivated decision.

Protecting

Regarding financial protection (i.e., insurance), several residents expressed a lack of consideration of this topic:

I haven't really thought about [insurance] as much as I should.

I know I need to get [insurance] … but to be honest with you … where do you even go to buy disability insurance?

Several residents who had considered insurance expressed a lack of knowledge in the area:

[Insurance] is something I wish I understood … but I found it very confusing.

I could use a lot of guidance and I don't really feel comfortable with my current coverage. I am just planning on not getting disabled.

Theme 2: Knowledge and Experiences

The second theme is residents’ personal finance knowledge and experiences. The most commonly mentioned topics included the five target areas established prior to the interviews (education debt, retirement planning, investing, disability insurance, and life insurance) as well as budgeting and home buying. Subthemes within these areas are listed in Table 1. Residents expressed variable levels of knowledge and interest in each of these areas; these levels are portrayed graphically in Figure 1. The most common sentiments within this theme were a lack of comfort with knowledge and experience and a desire for more knowledge:

Figure 1.

Postgraduate trainee knowledge and interest in target topics. Size of the point on the chart correlates with the number of subjects bringing up each topic. The small point (home buying) represents six subjects that brought up this topic; the large points represent all 12 subjects.

Lack of comfort with knowledge and experience:

I feel like I have a lot left to learn and I need to grow my knowledge.

I don't believe I have enough knowledge to make accurate decisions about anything [financial] at all.

Desire for more knowledge:

I am trying now to become a bit more educated and involved with our financial decisions.

One of my biggest new year's resolutions was to figure out my finances.

Theme 3: Approach to Financial Planning

The third theme is residents’ approach to financial planning. Comments relating to this theme describe learner attempts to orient themselves and align their actions with their interests; thus, these comments have been contextualized using the conceptual framework of wayfinding (orientation, route decision, route monitoring, and destination recognition).29 While wayfinding has traditionally been used to understand physical spaces, we found resident comments to resonate strongly with the operational elements of this framework.

Orientation

Comments regarding orientation are categorized into two subgroups: those characterizing the respondent's financial landscape and those characterizing the respondent's intellectual landscape. Comments about the financial landscape echoed earlier sentiments of limited cash flow and high debt levels:

Right now I don't have enough money … I am still paying off debt.

Comments about the intellectual landscape also echoed earlier sentiments, this time about the lack of comfort with their level of knowledge and a desire for more information:

I feel like I have a lot left to learn and I need to grow my knowledge.

I am at the time of my life when I should be thinking more about [investing].

Route Decision

Many residents expressed concerns about the uncertainty surrounding resources to assist in taking financial actions:

I am not sure what to do, who to talk to, and what to look for.

These concerns were often paired with an acknowledgement of significant pressure and solicitation from the financial industry:

I get these random e‐mails from [financial companies] … I feel like it's a very biased source of information.

I have been pitched a million times.

I get a lot of junk mail about [insurance].

Finally, several trainees commented on desired resources to assist with initial financial planning:

It would be good to do a webinar to go over the basic principles.

It would help if [financial education] was more interactive.

[In a] lecture‐based [format] you can ask questions right there.

Route Monitoring

One particularly interesting sentiment contributing to difficulty in “route monitoring” in financial planning is the lack of normalization of this topic:

It might make some people uncomfortable when we talk about it, but it is good for [trainees] … right now I don't think we have a normal conversation on this.

Other comments on the shortcomings of route monitoring opportunities included a lack of checkpoints:

I still don't know if my loan approach is a good idea or not,

[Regarding medical school loan counseling]: Exit interviews are a joke.

and distrust of the financial industry:

There are so many scuzzy people out there selling products that I have this instinctive distrust.

I feel like they are all selling products, which leaves me with no source of reliable information.

Desired resources for route monitoring focused on the importance of individual feedback and a need for deadlines:

I want something that is for me and what would make sense in my situation.

If it's not a strict deadline … it will never rise to the top of the to‐do list.

Destination Recognition

There were a limited number of comments regarding financial goals or “destinations.” Some residents expressed vague intentions to buy a house, pay off loans, or contribute to college funds for children; however, no residents expressed specific, time‐oriented financial goals that they aimed to achieve.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively examine resident personal finance knowledge, experiences, and attitudes using qualitative methods. Despite the variety and complexity of financial circumstances across the residents interviewed, several themes are clear. The majority of residents report operating on thin budgets with a high burden of debt, which serves as a source of significant anxiety. For many, this anxiety is compounded by the prospect of discontinuation of the federal PSLF program, upon which many residents are relying.5 These results align with reports of debt and anxiety in other studies.4, 5 A strong education in personal finance may help residents avoid pitfalls in these financial circumstances. However, some of the issues contributing to these circumstances are political or the products of past decisions; therefore, the impact of education on these circumstances may be attenuated.

While education cannot directly change the financial circumstances of residents, it can help them best decide how to use their income to achieve their future financial goals. The high level of resident interest in financial education found in this study is consistent with the experience of faculty who lecture on this topic.30 This high level of interest combined with the low levels of financial knowledge reported here and described previously suggest that this educational need is not being met by existing resources.3, 25

Based on subjects’ comments on knowledge and interest, high‐yield topics for a resident personal finance curriculum include 1) how to set financial goals and monitor progress; 2) how to seek advice in the context of high levels of distrust, solicitation, and conflicts of interest in industry professionals; and 3) this study's five target areas (education debt, retirement planning, investing, disability insurance, and life insurance). An additional topic to consider would be home buying, in which half of the residents interviewed reported interest. No residents expressed an interest in learning more about budgeting.

Residents suggested that both asynchronous Web resources and live sessions would be desired for an ideal personal finance curriculum. These comments would support a flipped classroom design where content is reviewed online and classroom sessions are reserved for interactive activities and practical application of what they have learned. This desire for tailored educational content in multiple formats may also shed light on why existing Web‐based and text resources have yet to close this educational gap.

Finally, while this study focused on the finances of residents, medical students may also benefit from a curriculum created to address these needs. Students typically do not have significant income to manage, but to “hit the ground running” with sound financial decisions in residency, financial literacy for medical students is needed.31 Teaching these concepts to graduate trainees alone may result in unnecessary missteps and lost opportunities early in training.

Limitations

Prior to developing a personal finance curriculum based on these results, further triangulation of findings with a larger cohort would be prudent. All residents in this study were volunteers from the same institution; future studies could include geographic diversity to triangulate results with residents in different regions, particularly those with different costs of living. In addition, the sample in this study did not include residents in surgical specialties or specialties with training periods longer than 3 years. Further study to determine differences in trends in these populations is warranted. The qualitative data from this study can be aligned to fit the instrument development model of mixed methods to allow further exploration of this topic on a larger scale.

While age may also affect results, diversity in age was not explicitly sought given the relative homogeneity of age of matriculation to medical school,32 which in this case has been used to extrapolate a degree of homogeneity in the age of medical trainees. Financial background relative to the national population may also affect generalizability; however, detailed information on the financial backgrounds of residents nationwide is not available and therefore cannot be meaningfully factored into selection of a representative sample. Additional methodologic limitations include the potential for payment bias from offering residents $20 gift cards in return for participation and that member checking and external peer debriefing were not performed.

Conclusion

Residents report a low level of financial literacy, high interest in financial education, and uncertainty where to find reliable financial advice. The framework provided in this study may be used to design education interventions to promote financial wellness in graduate medical trainees.

The authors wish to acknowledge Alisa McQueen, MD and John McConville, MD for their assistance in completing this study.

Supporting information

Data Supplement S1. Interview instrument.

AEM Education and Training 2018;2:195–203

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1. Improving Physician Resiliency. American Medical Association, 2015. Available at: http://www.amaalliance.org/assets/docs/improving_physician_resiliency%20-%20ama.pdf. Accessed Aug 4, 2017.

- 2. Mizell JS, Berry KS, Kimbrough MK, Bentley FR, Clardy JA, Turnage RH. Money matters: a resident curriculum for financial management. J Surg Res 2014;192:348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dhaliwal G, Chou CL. A brief educational intervention in personal finance for medical residents. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:374–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glaspy JN, Ma OJ, Steele MT, Hall J. Survey of emergency medicine resident debt status and financial planning preparedness. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:52–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Young TP, Brown MM, Reibling ET, et al. Effect of educational debt on emergency medicine residents: a qualitative study using individual interviews. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:409–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. AAMC . Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Physician Wellness: Preventing Resident and Fellow Burnout. American Medical Association, 2017. Available at: https://www.stepsforward.org/Static/images/modules/23/downloadable/resident_wellness.pdf. Accessed Aug 4, 2017.

- 8. Raj KS. Well‐being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:674–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morra DJ, Regehr G, Ginsburg S. Anticipated debt and financial stress in medical students. Med Teach 2008;30:313–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collier VU, McCue JD, Markus A, Smith L. Stress in medical residency: status quo after a decade of reform? Ann Intern Med 2002;136:384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Phillips JP, Petterson SM, Bazemore AW, Phillips RL. A retrospective analysis of the relationship between medical student debt and primary care practice in the United States. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:542–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grayson MS, Newton DA, Thompson LF. Payback time: the associations of debt and income with medical student career choice. Med Educ 2012;46:983–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morra DJ, Regehr G, Ginsburg S. Medical students, money, and career selection: students’ perception of financial factors and remuneration in family medicine. Fam Med 2009;41:105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frintner MP, Mulvey HJ, Pletcher BA, Olson LM. Pediatric resident debt and career intentions. Pediatrics 2013;131:312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, Kolars JC. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:416–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steiner JW, Pop RB, You J, et al. Anesthesiology residents’ medical school debt influence on moonlighting activities, work environment choice, and debt repayment programs: a nationwide survey. Anesth Analg 2012;115:170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rohlfing J, Navarro R, Maniya OZ, Hughes BD, Rogalsky DK. Medical student debt and major life choices other than specialty. Med Educ Online 2014;19:25603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teichman JM, Tongco W, MacNeily AE, Smart M. Personal finances of urology residents in Canada. Can J Urol 2000;7:1149–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teichman JM, Bernheim BD, Espinosa EA, et al. How do urology residents manage personal finances? Urology 2001;57:866–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chui MA. An elective course in personal finance for health care professionals. Am J Pharm Educ 2009;73:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liebzeit J, Behler M, Heron S, Santen S. Financial literacy for the graduating medical student. Med Educ 2011;45:1145–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boehnke M, Pokharel S, Nyberg E, Clark T. Financial education for radiology residents: significant improvement in measured financial literacy after a targeted intervention. J Am Coll Radiol 2018;15(1 Pt A):97–9.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yoo PS, Tackett JJ, Maxfield MW, Fisher R, Huot SJ, Longo WE. Personal and professional well‐being of surgical residents in New England. J Am Coll Surg 2017;224:1015–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Witek M, Siglin J, Malatesta T, et al. Is financial literacy necessary for radiation oncology residents? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;90:986–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahmad FA, White AJ, Hiller KM, Amini R, Jeffe DB. An assessment of residents’ and fellows’ personal finance literacy: an unmet medical education need. Int J Med Educ 2017;8:192–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bunton SA. Using qualitative research as a means to an effective survey instrument. Acad Med 2016;91:1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. NRMP . Results and Data: 2016 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fitzpayne A. Financial Education Core Competencies. Washington, DC: Department Treasury, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lidwell W, Holden K, Butler J. Universal Principles of Design. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pirotte M. Talking To Residents About Financial Planning In: Dahle J, editor. The White Coat Investor, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jayakumar K, Ginzberg S, Patel M. Personal financial literacy among U.S. medical students. MedEdPublish 2017;6:35. [Google Scholar]

- 32. AAMC . Age of Applicants to U.S. Medical Schools at Anticipated Matriculation. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement S1. Interview instrument.