Abstract

Purpose

Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations in glioma patients confer longer survival and may guide treatment decision-making. We aimed to predict the IDH status of gliomas from MR imaging by applying a residual convolutional neural network to pre-operative radiographic data.

Experimental Design

Preoperative imaging was acquired for 201 patients from the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania (HUP), 157 patients from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), and 138 patients from The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) and divided into training, validation, and testing sets. We trained a residual convolutional neural network for each MR sequence (FLAIR, T2, T1 pre-contrast, and T1 post-contrast) and built a predictive model from the outputs. To increase the size of training set and prevent overfitting, we augmented the training set images by introducing random rotations, translations, flips, shearing, and zooming.

Results

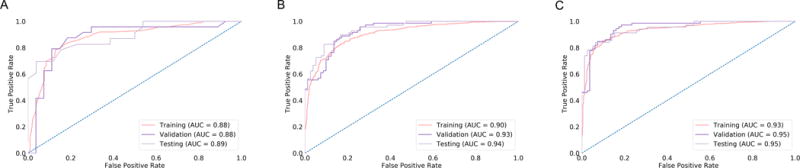

With our neural network model, we achieved IDH prediction accuracies of 82.8% (AUC = 0.90), 83.0% (AUC = 0.93), and 85.7% (AUC = 0.94) within training, validation, and testing sets, respectively. When age at diagnosis was incorporated into the model, the training, validation, and testing accuracies increased to 87.3% (AUC = 0.93), 87.6% (AUC = 0.95), and 89.1% (AUC = 0.95), respectively.

Conclusion

We developed a deep learning technique to non-invasively predict IDH genotype in grade II-IV glioma using conventional MR imaging using a multi-institutional dataset.

Keywords: Deep Learning, Convolutional Neural Network, Isocitrate Dehydrogenase, Glioma, MRI

Introduction

Gliomas are common infiltrative neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS) that affect patients of all ages. They are subdivided into four World Health Organization (WHO) grades (I-IV) (1). More than half of all patients with lower-grade gliomas (WHO grades II and III, LGGs) will experience tumor recurrence eventually (2–4). For grade III gliomas, the five-year survival rates are 27.3% to 52.2%, depending on subtype (5). For grade IV gliomas, the five-year survival rates are just 5% (5).

In 2008, the presence of IDH1mutations, specifically involving the amino acid arginine at position 132, was demonstrated in in 12% of glioblastomas (6), with subsequent reports observing IDH1 mutations in 50-80% of LGGs (7). In the wild-type form, the IDH gene product converts isocitrate into α-ketoglutarate (8). When IDH is mutated, the conversion of isocitrate is instead driven to 2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits downstream histone demethylases (9). The presence of an IDH mutation carries important diagnostic and prognostic value. Gliomas with the IDH1 mutation (or its homolog IDH2) carry a significantly increased overall survival than IDH1/2 wild-type tumors, independent of histological grade (6,10–12). Conversely, most lower grade gliomas with wild type IDH were molecularly and clinically similar to glioblastoma with equally dismal survival outcomes (1). IDH wild-type grade III gliomas may in fact exhibit a worse prognosis than IDH mutant grade IV gliomas (10). Its critical role in determining prognosis was emphasized with the inclusion of IDH mutation status as a classification parameter used in the 2016 update of WHO diagnostic criteria for gliomas (13).

Pre-treatment identification of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) status can help guide clinical decision making. First, a priori knowledge of IDH1 status with radiographic suspicion of a low-grade glioma may favor early intervention as opposed to observation as a management option. Second, IDH mutant gliomas are driven by specific epigenetic alterations, making them susceptible to therapeutic interventions (such as temozolomide) that are less effective against IDH wild-type tumors (14,15). This is supported by in vitro experiments, which have found IDH-mutated cancer cells to have increased radio- and chemo-sensitivity (16–18). Lastly, resection of non-enhancing tumor volume, beyond gross total removal of the enhancing tumor volume, was associated with a survival benefit in IDH1 mutant grade III–IV gliomas but not in IDH1 wild-type high-grade gliomas (19). Thus, early determination of IDH status may guide surgical treatment plans, peri-operative counseling, and the choice of adjuvant management plans.

Non-invasive prediction of IDH status in gliomas is a challenging problem. A recent study by Patel et al. using MR scans from the TCGA/TCIA low-grade glioma database demonstrated that T2-FLAIR mismatch was a highly specific imaging biomarker for the IDH-mutant, 1p19q non-deleted molecular subtype of gliomas (20). Other previous approaches toward prediction utilized isolated advanced MR imaging sequences, such as relative cerebral blood volume, sodium, spectroscopy, blood oxygen level-dependent, and perfusion (21–26). An alternative radiomics approach has also been applied, which extracts radiographic features from conventional MRI such as growth patterns as well as tumor margin and signal intensity characteristics. Radiomic approaches rely on multi-step pipelines that include generation of numerous pre-engineered features, selection of features, and application of traditional machine learning techniques (27). Deep learning simplifies this pipeline by learning predictive features directly from the image. The algorithm accomplishes this by utilizing a back-propagation algorithm which recalibrates the model’s internal parameters after each round of training. Recent studies have shown the potential of deep learning in the assessment of medical records, diabetic retinopathy, and dermatological lesions (28,29). Deep learning has shown promising capabilities in prediction of key molecular markers in gliomas such as 1p19q codeletion and MGMT promoter methylation (30,31). We hypothesize that a deep learning algorithm can achieve high accuracy in predicting IDH mutation in gliomas. In this study, we trained a deep learning algorithm to non-invasively predict IDH status within a multi-institutional dataset of low and high-grade gliomas.

Materials and Methods

Patient Cohorts

We retrospectively identified patients with histologically confirmed World Health Organization grade II-IV gliomas with proven IDH status (after resection or biopsy) at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), and The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA). The study was conducted following approval by the HUP and DanaFarber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center (DF/BWCC) Institutional Review Boards. MR imaging, clinical variables including patient demographics (i.e. age and sex), and genotyping data were obtained from the medical record under a consented research protocol approved by the DF/BWCC IRB. For the TCIA cohort, we identified glioma patients with preoperative MR imaging data from TCGA and IvyGap (32). Under TCGA/TCIA data-use agreements, analysis of this cohort was exempt from IRB approval. All patients identified met the following criteria: (i) histopathologically confirmed primary grade II-IV glioma according to current WHO criteria, (ii) known IDH genotype, and (iii) available preoperative MR imaging consisting of pre-contrast axial T1-weighted (T1 pre-contrast), post-contrast axial T1-weighted (T1 post-contrast), axial T2-weighted fast spin echo (T2), and T2-weighted fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. The scan characteristics for the 3 patient cohorts are shown in Supplemental Figs. 2–4. Patients whose genetic data were not confirmed per criteria (see “Tissue Diagnosis and Genotyping” section below) were excluded. Our final patient cohort included 201 patients from HUP, 157 patients from BWH, and 138 patients from TCIA.

Tissue Diagnosis and Genotyping

For the HUP cohort, IDH1R132H mutant status was determined using either immunohistochemistry (n = 93) or next-generation sequencing, performed by the Center for Personalized Diagnostics at HUP on 108 tumors diagnosed after February 2013. For the BWH cohort, IDH1/2 mutations were determined using immunohistochemistry, mass spectrometry-based mutation genotyping (OncoMap) (33), or capture-based sequencing (OncoPanel) (34,35) depending on the available genotyping technology at the time of diagnosis. OncoMap was performed by Center for Advanced Molecular Diagnostics of the BWH and Oncopanel was performed by Center for Cancer Genome Discovery of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. For patients under the age of 50 in the HUP and BWH cohorts, only gliomas with the absence of IDH1/2 mutation as determined by full sequencing assay were included in our analyses as IDH wild-type as to minimize the possibility of false negatives. IDH-mutated gliomas were defined by the presence of mutation as indicated by immunohistochemistry or sequencing on samples provided to the pathology department at each institution at the time of surgery. IDH1- and IDH2-mutated gliomas were collapsed into one category. For patients in the TCIA cohort, IDH1/2 mutation data were downloaded from TCGA and IvyGap data portal (32).

Tumor Segmentation

For the HUP and TCIA cohorts, MR imaging for each patient was loaded into Matrix User v2.2 (University of Wisconsin, WI), and 3D regions-of-interest were manually drawn slice-by-slice in the axial plane for the FLAIR image by a user (H.Z.) followed by manual editing by a neuroradiologist (Q.S.). For the BWH cohort, tumor outlines were drawn with a user-driven, manual active contour segmentation method with 3D Slicer software (v4.6) on the FLAIR image (K.C.) and edited by an expert neuroradiologist (R.Y.H.) (36,37). The segmented contour was then overlaid with source FLAIR, T2, T1 pre-contrast, and T1 post-contrast images.

Image Pre-Processing

All MR images were isotropically resampled to 1 mm with bicubic interpolation. T1 pre-contrast, T2, and FLAIR images were then registered to T1 post-contrast using the similarity metric. Resampling and registration was performed using MATLAB 2017a (Mathworks, MA). N4 bias correction (Nipype Python package) was applied to remove any low frequency intensity non-uniformity (38,39). Skull-stripping was then applied from the FSL library to isolate regions of brain (40). Image intensities were normalized by subtracting the median intensity of normal brain (non-tumor regions) and then dividing by the interquartile intensity of normal brain. To utilize information from all 3 spatial dimensions, we extracted coronal, sagittal, and axial tumor slices from each patient. Only slices with tumor were extracted. To extract a slice, a bounding rectangle derived from the tumor segmentation was drawn around the tumor. This ensures that the entire tumor area is captured as well as a portion of the tumor margin. Because every tumor is different in size, all slices were resized to 142×142 voxels for input into our neural network.

Gliomas are heterogeneous 3D volumes with complex imaging characteristics across each dimension. In our experiments, we choose to model this 3D heterogeneity by using 3 representative orthogonal slices, one each in the axial, coronal and sagittal planes. Together, these 3 orthogonal slices represent a single “sample” of the 3D tumor volume, and a total of three such samples were chosen for each patient based on the following scheme: 1) the coronal slice with the largest tumor area, the sagittal slice with the 75th percentile tumor area, and the axial slice with the 50th percentile tumor area, 2) the coronal slice with the 50th percentile tumor area, the sagittal slice with the largest tumor area, and the axial slice with the 75th percentile tumor area, 3) the coronal slice with the 75th percentile tumor area, the sagittal slice with the 50th percentile tumor area, and the axial slice with the largest tumor area. While each such sample may be somewhat correlated to other samples of the same tumor, gliomas exhibit marked heterogeneity and each additional set of orthogonal slices captures a marginal but significant amount extra information about that particular tumor. After pre-processing, the total number of patient samples was 603 for HUP, 414 for TCIA, and 471 for BWH. Image samples from the same patient were kept together when randomizing into training, validation, and testing sets. Another method of addressing overfitting is to augment the training data by introducing random rotations, translations, shearing, zooming, and flipping (horizontal and vertical), generating “new” training data (30). The augmentation technique allows us to further increase the size of our training set. For every epoch, we augmented the training data before inputting it into the neural network. Augmentation was only performed on the training set and not the validation or testing sets. Data augmentation was performed in real time in order to minimize memory usage.

Residual Neural Network

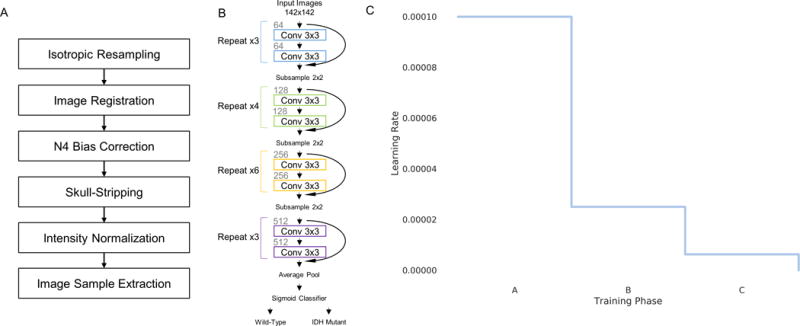

Convolutional neural networks are a type of neural network developed specifically to learn hierarchical representations of imaging data. The input image is transformed through a series of chained convolutional layers that result in an output vector of class probabilities. It is the stacking of multiple convolutional layers with non-linear activation functions that allow a network to learn complex features. Residual neural networks won the 2015 Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge by allowing effective training of substantially deeper networks than those used previously while maintaining fast convergence times (41). This is accomplished via shortcut, “residual” connections that do not increase the network’s computational complexity (41). Our residual network was derived from a 34-layer residual network architecture (Fig. 1A) (41). As with the original residual network architecture, batch normalization was used after every convolutional layer (42). Batch normalization forces network activations to follow a unit Gaussian distribution after each update, preventing internal covariate shift and overfitting (42). The first two layers of the original residual network architecture, which sub-sample the input images, were not used, as the size of our input (142×142) is smaller than that of the original residual net input (224×224).

Figure 1.

(A) Image pre-processing steps in our proposed approach. (B) A modified 34-layer residual neural network architecture was used to predict IDH status. (C) Displays the learning rate schedule. The learning rate was set to .0001 and stepped down to .25 of its value when there is no improvement in the validation loss for 20 consecutive epochs.

Implementation Details

Our implementation was based on the Keras package with the TensorFlow library as the backend. During training, the probability of each patient sample belonging to the wild-type or mutant IDH class was computed with a sigmoid classifier. We used the rectified liner unit activation function in each layer. The weights of the network were optimized via a stochastic gradient descent algorithm with a mini-batch size of 16. The objective function used was binary cross-entropy. The learning rate was set to 0.0001 with a momentum coefficient of 0.9. The learning rate was decayed to 0.25 of its value after 20 consecutive epochs without an improvement of the validation loss. The learning rate was decayed 2 times (Training Phases A–C, Fig. 1B). At the end of training phase A and B, the model was reverted back to the model with the lowest validation loss up until that point in training. The final model was the one with the lowest validation loss at any point during training. Biases were initialized randomly using the Glorot uniform initializer (43). We ran our code on a graphics processing unit to exploit its computational speed. Our algorithm was trained on a Tesla P100 graphics processing unit. Code for image pre-processing as well as trained models utilizing the modality networks heuristic can be found here: https://github.com/changken1/IDH_Prediction.

Training with Three Patient Cohorts

Each patient cohort (HUP, BWH, and TCIA) was randomly divided into training, validation, and testing sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, balancing for mutation status and age. In our experiments training with all three patient cohorts, we combined HUP, BWH, and TCIA training sets. Similarly, we combined HUP, BWH, and TCIA validation sets as well as testing sets. The combined testing set was not disclosed until the model was finalized.

We implemented three different training heuristics. In the first heuristic, we input all sequences and dimensions into a single residual network with input size 12×142×142 (single combined network heuristic, Fig. 2A). In the second heuristic, we trained a separate residual network for each dimension (input size 4×142×142) and combined the sigmoid probabilities of each network with a logistic regression (dimensional networks heuristic, Fig. 2B). In the third heuristic, we trained a separate network for each MRI sequence (input size 3×142×142) and combined the sigmoid probabilities of each network with a logistic regression (sequence networks heuristic, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

The training heuristics tested include a (A) single combined network, (B) dimensional networks, and (C) sequence networks. In the single combined network training heuristic, all sequences and dimensions were inputted into a single network. In the dimensional networks training heuristic, a separate network was trained for each dimension. In the sequence networks training heuristics, a separate network was trained for each MR sequence.

Because IDH status is correlated with age (44), we compared the results of residual neural networks with a logistic regression model based on age of patients in the training and validation sets. We also implemented a logistic regression model combining the sigmoid probability output of the residual neural networks and age.

Independent Testing

We also trained residual networks with two patient cohorts with the goal of seeing if the model could predict IDH mutation status in the independent testing set without having been trained on any patients in that set. In these experiments, we combined the training sets of two patient cohorts. Similarly, we combined the validation sets and testing sets of two patient cohorts. The remaining patient cohort was kept aside as an independent testing set. The testing and independent testing sets were not disclosed until the final model was developed. The sequence networks training heuristic was used for these experiments.

Evaluation of Models

The performance of models was evaluated by assessing the accuracy on training, validation, and testing sets. In addition, sigmoid or logistic regression probabilities were used to calculate Area Under Curve (AUC) of Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) analysis. Bootstrapping was used to calculate the confidence intervals (CI) of the AUC values.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The median age of the HUP, BWH, and TCIA cohorts were 56, 47, and 52 years, respectively (Table 1). The percentage of males was 56%, 57%, and 57%, respectively. The HUP cohort was 19% grade II (72% IDH-mutant), 34% grade III (59% IDH-mutant), and 46% grade IV (3% IDH mutant). The BWH cohort was 20% grade II (100% IDH-mutant), 29% grade III (87% IDH-mutant), and 51% grade IV (26% IDH mutant). The TCIA cohort was 25% grade II (91% IDH-mutant), 32% grade III (70% IDH-mutant), and 43% grade IV (12% IDH mutant). Collectively, the HUP, BWH, and TCIA cohorts were 36%, 59%, and 50% IDH-mutant, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, IDH status, and grade for HUP, BWH, and TCIA cohorts. Age is shown as median (minimum-maximum).

| HUP, n = 201 | BWH, n= 157 | TCIA, n= 138 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 56 (18–88) | 47 (18–85) | 52 (21–84) |

|

| |||

| Sex (% Male) | 56% | 57% | 57% |

|

| |||

| IDH mutation rate | 36% | 59% | 50% |

|

| |||

| Grade & IDH status | |||

| II Wild-Type | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| II Mutant | 28 | 31 | 31 |

| III Wild-Type | 28 | 6 | 13 |

| III Mutant | 41 | 40 | 31 |

| IV Wild-Type | 90 | 59 | 53 |

| IV Mutant | 3 | 21 | 7 |

Optimization of Deep Learning Model

We first determine the optimal training heuristics for the full multi-center data set by comparing three different heuristics (Fig. 3). A logistic regression model using age alone had an AUC of 0.88 on the Training set, 0.88 on the Validation set, and 0.89 on the Testing set (Table 2).

Figure 3.

ROC curves for training, validation, and testing sets from training on three patient cohorts for (A) age only, (B) combining sequence networks, and (C) combining sequence networks + age. The testing set AUC for combing sequence networks + age was 0.95.

Table 2.

Accuracies and AUC from ROC analysis from training on three patient cohorts. The methods shown include age only, the single combined network training heuristic, the dimensional networks training heuristic, and the sequence networks training heuristic.

| Training Set HUP + BWH + TCIA n = 1188 | Validation Set HUP + BWH + TCIA n = 153 | Testing Set HUP + BWH + TCIA n = 147 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Accuracy | AUC | Accuracy | AUC | Accuracy | AUC | |

|

| ||||||

| Age | 82.6% | .88 | 82.4% | .88 | 79.6% | .89 |

|

| ||||||

| Single Combined Network | ||||||

| Single combined network | 86.4% | .93 | 82.4% | .92 | 76.9% | .86 |

| Single combined network + age | 89.1% | .95 | 86.9% | .95 | 84.4% | .92 |

|

| ||||||

| Dimensional Networks | ||||||

| Coronal network | 80.0% | .87 | 77.8% | .89 | 76.9% | .85 |

| Sagittal network | 78.8% | .86 | 79.1% | .88 | 79.6% | .86 |

| Axial network | 82.0% | .90 | 79.7% | .91 | 76.9% | .87 |

| Combining dimensional networks | 83.2% | .91 | 84.3% | .93 | 77.6% | .90 |

| Combining dimensional networks + age | 87.2% | .94 | 85.6% | .94 | 89.1% | .95 |

|

| ||||||

| Sequence Networks | ||||||

| FLAIR network | 65.9% | .72 | 62.1% | .70 | 65.3% | .69 |

| T2 network | 68.4% | .74 | 66.0% | .77 | 67.3% | .73 |

| T1 pre-contrast network | 68.7% | .77 | 72.5% | .75 | 68.7% | .86 |

| T1 post-contrast network | 80.5% | .88 | 82.4% | .89 | 86.4% | .92 |

| Combining sequence networks | 82.8% | .90 | 83.0% | .93 | 85.7% | .94 |

| T1C network + age | 87.2% | .93 | 86.9% | .95 | 87.8% | .94 |

| Combining sequence networks + age | 87.3% | .93 | 87.6% | .95 | 89.1% | .95 |

First, we constructed a single combined network model (Supplemental Fig.1A). After 157 epochs training, the resulting model had an AUC of 0.93 on the Training set, 0.92 on the Validation set, and 0.86 on the Testing set. When combined with age, the single combined network had improved performance with an AUC of 0.95 on the Training set, 0.95 on the Validation set, and 0.92 on the Testing set.

To demonstrate the individual predictive performance for different imaging dimensions, the coronal, sagittal, and axial networks were trained for 92, 82, and 122 epochs, respectively (Supplemental Fig.1B–D). The final model for the coronal, sagittal, and axial networks had Testing set AUCs of 0.85, 0.86, and 0.87, respectively. When the dimensional networks were combined, the AUC was 0.91 on the Training set, 0.93 on the Validation set, and 0.90 on the Testing set. Performance was improved when dimensional networks were combined with age with an AUC of 0.94 on the Training set, 0.94 on the Validation set, and 0.95 on the Testing set.

To demonstrate the individual predictive performance for different MRI sequences, the FLAIR, T2, T1 pre-contrast, and T1 post-contrast networks were trained for 88, 75, 76, and 325 epochs, respectively (Supplemental Fig.1E–H). The final model for the FLAIR, T2, T1 pre-contrast, and T1 post-contrast networks had Testing set AUCs of 0.69, 0.73, 0.86, and 0.92, respectively. When the sequence networks were combined, the AUC was 0.90 on the Training set, 0.93 on the Validation set, and 0.94 on the Testing set. When sequence networks were combined with age the AUC was 0.93 on the Training set, 0.95 on the Validation set, and 0.95 on the Testing set (Fig. 3). Looking at predictive performance for the individual tumor grades, the AUC for the Validation and Testing cohorts were 0.85 (n = 66), 0.91 (n = 81), and .94 (n = 153) for grades 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Overall, combining the sequence networks and age resulted in the highest performance in terms of accuracy and AUC values in the validation and testing set. This approach was subsequently applied to independent data set testing.

Training on Two Patient Cohorts and Independent Performance Testing on the Third Cohort

To examine the generalizability of our model, the sequence network training heuristic was applied to training on two patient cohorts at a time. FLAIR, T2, T1 pre-contrast, and T1 post-contrast residual networks were trained on the combined Training sets of HUP + TCIA, HUP + BWH, and TCGA + BWH with data from the remaining site reserved for independent testing (Supplemental Table 1). The average AUCs for combining sequence networks within the Training, Validation, Testing, and Independent Testing Cohorts were 0.90 (95% CI 0.88-0.92), 0.89 (95% CI 0.84-0.94), 0.92 (95% CI 0.88-0.96), and 0.85 (95% CI 0.82-0.88), respectively. When age was combined with sequence networks, the average AUCs were 0.94 (95% CI 0.92-0.95), 0.95 (95% CI 0.91-0.98), 0.95 (95% CI 0.91-0.98), and 0.91 (95% CI 0.88-0.93) respectively within the Training, Validation, Testing, and Independent Testing sets. Comparatively, a logistic regression model utilizing age alone had an average AUC of 0.88, 0.88, 0.89, and 0.87 respectively within the Training, Validation, Testing, and Independent Testing sets. The average accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity for combined model for age and sequence networks on the independent Testing set was 82.1%, 79.1%, and 87.0%, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the utility of deep learning to predict IDH mutation status in a large, multi-institutional dataset of gliomas as part of a larger effort to apply deep learning techniques to the field of neuro-oncology. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date on the prediction of IDH status from conventional MR imaging and deep learning methods. Furthermore, our algorithm has broad applicability by utilizing conventional MR performed at different institutions, as advanced MR sequences or other modalities may not be part of the standard imaging protocol. Pre-treatment identification of IDH status may be important in clinical-decision making as it may guide patient management, choice of chemotherapy, and surgical approach.

We did not include WHO grade information in our prediction model since this data would not have been known a priori without pathological tissue after invasive biopsy or surgery. The goal of our algorithm was to use conventional MR sequences to predict IDH mutation status before surgery. Furthermore, we did not train separate networks for each tumor grade to reflect the pre-operative clinical scenario, when the WHO grade remains unknown prior to acquisition of pathological tissue from biopsy or surgery. Increasing research and the updated 2016 WHO classification of CNS tumors further emphasize molecular phenotype as a critical determinant of glioma behavior even before the assignment of histopathologic grade (13).

Previous studies have reported an association between radiographic appearance and IDH genotype within gliomas. IDH wild-type grade II gliomas are more likely to display an infiltrative pattern on MRI, compared to the sharp tumor margins and homogenous signal intensity characteristic of IDH mutant gliomas (45). Patel et al. found T2-FLAIR mismatch to be a specific biomarker for IDH-mutant, 1p19q non-deleted gliomas (20). Hao et al. scored pre-operative MRIs of 165 patients from the TCIA/TCGA according to the Visually Accessible Rembrandt Images (VASARI) annotations and found that increased proportion of necrosis and decreased lesion size were the features most predictive of an IDH mutation (46). However, VASARI features overall achieved lower accuracy than texture features in this study. In another study of 153 patients with glioblastoma using the VASARI features, Lasocki et al. found that if a particular glioblastoma does not have a frontal lobe epicenter and has less than 33% non-enhancing tumor, it can be predicted to be IDH1-wildtype with a high degree of confidence (47). One significant limitation of this study is that only five glioblastoma patients had IDH1 mutation (3.3%). Furthermore, Yamashita et al. found that mutant IDH1 glioblastoma patients had a lower percentage of necrosis within enhancing tumor with the caveat that the study included only 11 IDH1 mutant tumors (48).

As such, various studies have used a radiomics approach to predict IDH status. Zhang et al. used clinical and imaging features to predict IDH genotype in grade III and grade IV gliomas with an accuracy of 86% in the training cohort and 89% in the validation cohort (44). Hao et al. used preoperative MRIs of 165 MRIs from the TCIA to predict IDH mutant status with an AUC value of 0.86 (46). Similarly, Yu et al. used a radiomic approach to predict IDH mutations in grade II gliomas with an accuracy of 80% in the training cohort and 83% on the validation cohort (49). Deep learning simplifies the multi-step pipeline utilized by radiomics by learning predictive features directly from the image, allowing for greater reproducibility. In this study, we demonstrate that accurate prediction can be achieved in a multi-institutional patient cohort of both low- and high-grade gliomas without pre-engineered features.

One challenge of training deep neural networks is the need for a large amount of training data. We addressed this by artificially augmenting our imaging data, in real-time, before each training epoch. This has the additional benefit of preventing overfitting, which is another common issue when training networks. We also utilized batch normalization after each convolutional layer to prevent overfitting, as with the original residual network architecture.

We implemented various training heuristics with training on three patient cohorts – namely a single combined network, dimensional networks, and sequence networks. Under the dimensional networks training heuristic, we trained a neural network for coronal, sagittal, and axial dimensions which had similar testing set performance. These results suggest that all dimensions have similar predictive value. Under the sequence networks training heuristic, we trained a neural network for each MR sequence. Notably, T1 post-contrast images conferred a higher predictive value compared to other MR sequences and appeared to drive the vast majority of the accuracy of the combined sequence model with additional sequences contributing a smaller incremental benefit. The only imaging-only models that outperformed the age-only logistic regression model in terms of accuracy in the validation and testing set were the T1 post-contrast network and a model combining sequence networks. Overall, a combination of sequence networks and age offered the highest accuracy in the validation and testing sets.

When the sequence networks training heuristic was applied to training on two patient cohorts at a time, similar results were observed when training on three patient cohorts. For training on HUP + TCIA, HUP + BWH, and TCIA + BWH, combining sequence networks and age had a higher AUC than a logistic regression using age only in the training, validation, testing, and independent testing sets. However, the AUC of the combined sequence network and age model within the independent testing set was lower than that of the testing set. The most likely reason for this are the differences in scan parameters and in IDH mutation rate among the different patient cohorts (Table 1; Supplemental Fig. 2–4). In the ideal scenario, all patient scans would be collected with consistent acquisition parameters (field strength, resolution, slice thickness, echo time, and repetition time), and IDH mutation rate would be the same. However, this would be challenging in practice, as MR scanner models and acquisition parameters, as well as the demographics of patient captured, vary widely from institution to institution. Our study distinguishes itself from past studies in the field by using multi-institutional data and makes an important first step towards achieving the goal of independent validation, which is necessary if radiogenomic tools are to be used in a clinical setting.

There are several possible improvements to this study. First, the potential of advanced MR sequences in the prediction of IDH genotype has been demonstrated in several studies (21–25). We did not utilize such sequences, but future studies can combine advanced imaging modalities with conventional MR imaging to test for possible enhancement of prediction performance. However, addition of these advanced MR sequences is also a limitation in that these sequences may not be available at every institution. Second, sufficient cohort size is a limiting factor in the training of deep neural networks. Although we overcame this partially though data augmentation and extracting multiple imaging samples from the same patient, it is likely a larger patient population would further improve algorithm performance, especially given the heterogeneity in image acquisition parameters. Third, the use of other techniques such as dropout, L1, and L2 regularization may improve the generalizability of our model (50), although we found that data augmentation and batch normalization were sufficient to prevent overfitting of our model, as evidenced by the high testing accuracies. Lastly, incorporation of spatial characteristics of IDH-mutated gliomas (such as unilateral patterns of growth and localization within single lobes) into the deep neural network may further improve model performance (45).

In this study, we developed a technique to non-invasively predict IDH genotype in grade II-IV glioma using conventional MR imaging. In contrast to a radiomics approach, our deep learning model does not require pre-engineered features. Our model may have the potential to serve as a noninvasive tool that complements invasive tissue sampling, guiding patient management at an earlier stage of disease and in follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Our model may have the potential to serve as a noninvasive tool that complements direct tissue sampling, guiding patient management at an earlier stage of disease and in follow-up.

Translational Relevance.

Deep learning algorithms can be trained to recognize patterns directly from imaging. In our study, we use a residual convolutional neural network to non-invasively predict IDH status from MR imaging. IDH status is of clinical importance as patients with IDH-mutated tumors have longer overall survival than their IDH-wild-type counterparts. In addition, knowledge of IDH status may guide surgical planning. By using a large, multi-institutional patient dataset with a diversity of acquisition parameters, we show the potential of the approach in clinical practice. Furthermore, this algorithm offers broad applicability by utilizing conventional MR imaging sequences. Our model offers the potential to complement surgical biopsy and histopathological analysis. More generally, our results (i) show that artificial intelligence can robustly recognize genomic patterns within imaging, (ii) advance non-invasive characterization of gliomas, and (iii) demonstrate the potential of algorithmic tools within the clinic to aid clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a training grant from the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (T90DA022759/R90DA023427) to K. Chang. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U01 CA154601, U24 CA180927, and U24 CA180918 to J. Kalpathy-Cramer.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81301988 to L. Yang, 81472594/81770781 to X. Li., 81671676 to W. Liao), and Shenghua Yuying Project of Central South University to L. Yang.

We would like the acknowledge the GPU computing resources provided by the MGH and BWH Center for Clinical Data Science.

This research was carried out in whole or in part at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at the Massachusetts General Hospital, using resources provided by the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies, P41EB015896, a P41 Biotechnology Resource Grant supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Note: K. Chang and H. X. Bai share primary authorship.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Brat DJ, Verhaak RGW, Aldape KD, Yung WKA, Salama SR, et al. Comprehensive, Integrative Genomic Analysis of Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2015;372:2481–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121. cited 2017 Feb 28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26061751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schomas DA, Laack NNI, Rao RD, Meyer FB, Shaw EG, O’Neill BP, et al. Intracranial low-grade gliomas in adults: 30-year experience with long-term follow-up at Mayo Clinic. Neuro Oncol [Internet] 2009;11:437–45. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-102. cited 2017 Feb 28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19018039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pouratian N, Schiff D. Management of Low-Grade Glioma. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep [Internet] 2010;10:224–31. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0105-7. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20425038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venneti S, Huse JT. The Evolving Molecular Genetics of Low-grade Glioma. Adv Anat Pathol [Internet] 2015;22:94–101. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000049. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25664944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J, Liu M, Blanda R, Kromer C, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro Oncol [Internet] 2015;17(Suppl 4):iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov189. cited 2015 Nov 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26511214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC-H, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An Integrated Genomic Analysis of Human Glioblastoma Multiforme. Science (80-) [Internet] 2008;321:1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18772396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Sicotte H, et al. N Engl J Med [Internet] Vol. 372. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2015. Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors; pp. 2499–508. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMoa1407279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Ye D, Guan K-L, Xiong Y. IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations in Tumorigenesis: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives. Clin Cancer Res [Internet] 2012;18:5562–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1773. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flavahan WA, Drier Y, Liau BB, Gillespie SM, Venteicher AS, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, et al. Insulator dysfunction and oncogene activation in IDH mutant gliomas. Nature [Internet] 2016;529:110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature16490. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nature16490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann C, Hentschel B, Wick W, Capper D, Felsberg J, Simon M, et al. Patients with IDH1 wild type anaplastic astrocytomas exhibit worse prognosis than IDH1-mutated glioblastomas, and IDH1 mutation status accounts for the unfavorable prognostic effect of higher age: implications for classification of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol [Internet] 2010;120:707–18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0781-z. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21088844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houillier C, Wang X, Kaloshi G, Mokhtari K, Guillevin R, Laffaire J, et al. IDH1 or IDH2 mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in low-grade gliomas. Neurology [Internet] 2010;75:1560–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f96282. cited 2017 Feb 28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20975057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, et al. N Engl J Med [Internet] Vol. 360. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2009. IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations in Gliomas; pp. 765–73. cited 2017 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol [Internet] 2016;131:803–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. cited 2017 Feb 28. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SongTao Q, Lei Y, Si G, YanQing D, HuiXia H, XueLin Z, et al. IDH mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in secondary glioblastoma. Cancer Sci [Internet] 2012;103:269–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02134.x. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narita Y, Narita Y, Miyakita Y, Ohno M, Matsushita Y, Fukushima S, et al. IDH1/2 mutation is a prognostic marker for survival and predicts response to chemotherapy for grade II gliomas concomitantly treated with radiation therapy. Int J Oncol [Internet] 2012;41:1325–36. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1564. cited 2017 Jul 16. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22825915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molenaar RJ, Botman D, Smits MA, Hira VV, van Lith SA, Stap J, et al. Radioprotection of IDH1-Mutated Cancer Cells by the IDH1-Mutant Inhibitor AGI-5198. Cancer Res [Internet] 2015;75:4790–802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3603. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohrenz IV, Antonietti P, Pusch S, Capper D, Balss J, Voigt S, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutant R132H sensitizes glioma cells to BCNU-induced oxidative stress and cell death. Apoptosis [Internet] 2013;18:1416–25. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0877-8. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10495-013-0877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sulkowski PL, Corso CD, Robinson ND, Scanlon SE, Purshouse KR, Bai H, et al. 2-Hydroxyglutarate produced by neomorphic IDH mutations suppresses homologous recombination and induces PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Sci Transl Med [Internet] 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal2463. cited 2017 Jul 16. Available from: http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/9/375/eaal2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beiko J, Suki D, Hess KR, Fox BD, Cheung V, Cabral M, et al. IDH1 mutant malignant astrocytomas are more amenable to surgical resection and have a survival benefit associated with maximal surgical resection. Neuro Oncol [Internet] 2014;16:81–91. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not159. cited 2017 Mar 12. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/neuro-oncology/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/neuonc/not159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel SH, Poisson LM, Brat DJ, Zhou Y, Cooper L, Snuderl M, et al. T2–FLAIR Mismatch, an Imaging Biomarker for IDH and 1p/19q Status in Lower-grade Gliomas: A TCGA/TCIA Project. Clin Cancer Res [Internet] 2017 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0560. [cited 2017 Sep 18]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28751449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kickingereder P, Sahm F, Radbruch A, Wick W, Heiland S, von Deimling A, et al. IDH mutation status is associated with a distinct hypoxia/angiogenesis transcriptome signature which is non-invasively predictable with rCBV imaging in human glioma. Sci Rep [Internet] 2015;5:16238. doi: 10.1038/srep16238. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26538165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biller A, Badde S, Nagel A, Neumann J-O, Wick W, Hertenstein A, et al. Improved Brain Tumor Classification by Sodium MR Imaging: Prediction of IDH Mutation Status and Tumor Progression. Am J Neuroradiol [Internet] 2016;37:66–73. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4493. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26494691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pope WB, Prins RM, Albert Thomas M, Nagarajan R, Yen KE, Bittinger MA, et al. Non-invasive detection of 2-hydroxyglutarate and other metabolites in IDH1 mutant glioma patients using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurooncol [Internet] 2012;107:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0737-8. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22015945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andronesi OC, Kim GS, Gerstner E, Batchelor T, Tzika AA, Fantin VR, et al. Detection of 2-Hydroxyglutarate in IDH-Mutated Glioma Patients by In Vivo Spectral-Editing and 2D Correlation Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Sci Transl Med [Internet] 2012;4:116ra4–116ra4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002693. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22238332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi C, Ganji SK, DeBerardinis RJ, Hatanpaa KJ, Rakheja D, Kovacs Z, et al. 2-hydroxyglutarate detection by magnetic resonance spectroscopy in IDH-mutated patients with gliomas. Nat Med [Internet] 2012;18:624–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2682. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22281806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stadlbauer A, Zimmermann M, Kitzwögerer M, Oberndorfer S, Rössler K, Dörfler A, et al. Radiology [Internet] Radiological Society of North America; 2016. MR Imaging–derived Oxygen Metabolism and Neovascularization Characterization for Grading and IDH Gene Mutation Detection of Gliomas; 161422 pp. cited 2017 Apr 7. Available from: http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/radiol.2016161422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parmar C, Grossmann P, Bussink J, Lambin P, Aerts HJWL. Sci Rep [Internet] Vol. 5. Nature Publishing Group; 2015. Machine Learning methods for Quantitative Radiomic Biomarkers; p. 13087. cited 2017 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/srep13087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, Stumpe MC, Wu D, Narayanaswamy A, et al. JAMA [Internet] Vol. 316. American Medical Association; 2016. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs; p. 2402. cited 2017 May 10. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2016.17216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature [Internet] 2017;542:115–8. doi: 10.1038/nature21056. cited 2017 May 10. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nature21056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akkus Z, Ali I, Sedlář J, Agrawal JP, Parney IF, Giannini C, et al. J Digit Imaging [Internet] Springer International Publishing; 2017. Predicting Deletion of Chromosomal Arms 1p/19q in Low-Grade Gliomas from MR Images Using Machine Intelligence; pp. 1–8. cited 2017 Jul 8. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10278-017-9984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korfiatis P, Kline TL, Lachance DH, Parney IF, Buckner JC, Erickson BJ. Residual Deep Convolutional Neural Network Predicts MGMT Methylation Status. J Digit Imaging [Internet] 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10278-017-0009-z. [cited 2017 Sep 18]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28785873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Clark K, Vendt B, Smith K, Freymann J, Kirby J, Koppel P, et al. J Digit Imaging [Internet] Vol. 26. Springer; 2013. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA): maintaining and operating a public information repository; pp. 1045–57. cited 2017 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23884657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas RK, Baker AC, DeBiasi RM, Winckler W, LaFramboise T, Lin WM, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet [Internet] 2007;39:347–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. cited 2017 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17293865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cryan JB, Haidar S, Ramkissoon LA, Linda Bi W, Knoff DS, Schultz N, et al. Clinical multiplexed exome sequencing distinguishes adult oligodendroglial neoplasms from astrocytic and mixed lineage gliomas. Oncotarget [Internet] 2014;5:8083–92. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2342. cited 2017 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25257301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagle N, Berger MF, Davis MJ, Blumenstiel B, DeFelice M, Pochanard P, et al. High-Throughput Detection of Actionable Genomic Alterations in Clinical Tumor Samples by Targeted, Massively Parallel Sequencing. Cancer Discov [Internet] 2012;2:82–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0184. cited 2017 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22585170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang K, Zhang B, Guo X, Zong M, Rahman R, Sanchez D, et al. Multimodal imaging patterns predict survival in recurrent glioblastoma patients treated with bevacizumab. Neuro Oncol [Internet] 2016;18:1680–7. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now086. cited 2017 Feb 28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27257279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin J-C, Pujol S, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging [Internet] 2012;30:1323–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001. cited 2017 Apr 15. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22770690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tustison NJ, Avants BB, Cook PA, Yuanjie Zheng Y, Egan A, Yushkevich PA, et al. N4ITK: Improved N3 Bias Correction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging [Internet] 2010;29:1310–20. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2046908. cited 2017 Mar 6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20378467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorgolewski K, Burns CD, Madison C, Clark D, Halchenko YO, Waskom ML, et al. Nipype: A Flexible, Lightweight and Extensible Neuroimaging Data Processing Framework in Python. Front Neuroinform [Internet] 2011;5:13. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2011.00013. Frontiers. cited 2017 Apr 12. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fninf.2011.00013/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. Neuroimage [Internet] 2012;62:782–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. cited 2017 Apr 12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21979382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang He K, Ren X, Sun SJ. 2016 IEEE Conf Comput Vis Pattern Recognit [Internet] IEEE; 2016. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition; pp. 770–8. cited 2017 Apr 12. Available from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7780459/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ioffe S, Szegedy C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. [cited 2017 Apr 12]; Available from: http://proceedings.mlr.press/v37/ioffe15.pdf.

- 43.Glorot X, Glorot X, Bengio Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. Proc Int Conf Artif Intell Stat (AISTATS’10) Soc Artif Intell Stat [Internet] 2010 [cited 2017 Apr 12]; Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.207.2059.

- 44.Zhang B, Chang K, Ramkissoon S, Tanguturi S, Bi WL, Reardon DA, et al. Multimodal MRI features predict isocitrate dehydrogenase genotype in high-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol [Internet] 2017;19:109–17. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now121. cited 2017 Feb 28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27353503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Qi S, Li L, Ou H, Qiu Y, Ding XY, et al. Oncol Lett [Internet] Vol. 7. Spandidos Publications; 2014. Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation is associated with tumor location and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics in astrocytic neoplasms; pp. 1895–902. cited 2017 Feb 28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24932255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou H, Vallières M, Bai HX, Su C, Tang H, Oldridge D, et al. MRI features predict survival and molecular markers in diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol [Internet] 2017;19:862–70. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now256. cited 2017 Jul 9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/neuro-oncology/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/neuonc/now256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lasocki A, Tsui A, Gaillard F, Tacey M, Drummond K, Stuckey S. Reliability of noncontrast-enhancing tumor as a biomarker of IDH1 mutation status in glioblastoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;39:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamashita K, Hiwatashi A, Togao O, Kikuchi K, Hatae R, Yoshimoto K, et al. MR imaging-based analysis of glioblastoma multiforme: Estimation of IDH1 mutation status. Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:58–65. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi Yu J, Lian Z, Li Y, Liu Z, Gao TY, et al. Noninvasive IDH1 mutation estimation based on a quantitative radiomics approach for grade II glioma. Eur Radiol [Internet] 2017;27:3509–22. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4653-3. cited 2017 Jul 9. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00330-016-4653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srivastava N, Hinton G, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J Mach Learn Res [Internet] 2014;15:1929–58. cited 2017 Apr 12. Available from: http://jmlr.org/papers/v15/srivastava14a.html. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.