Key Points

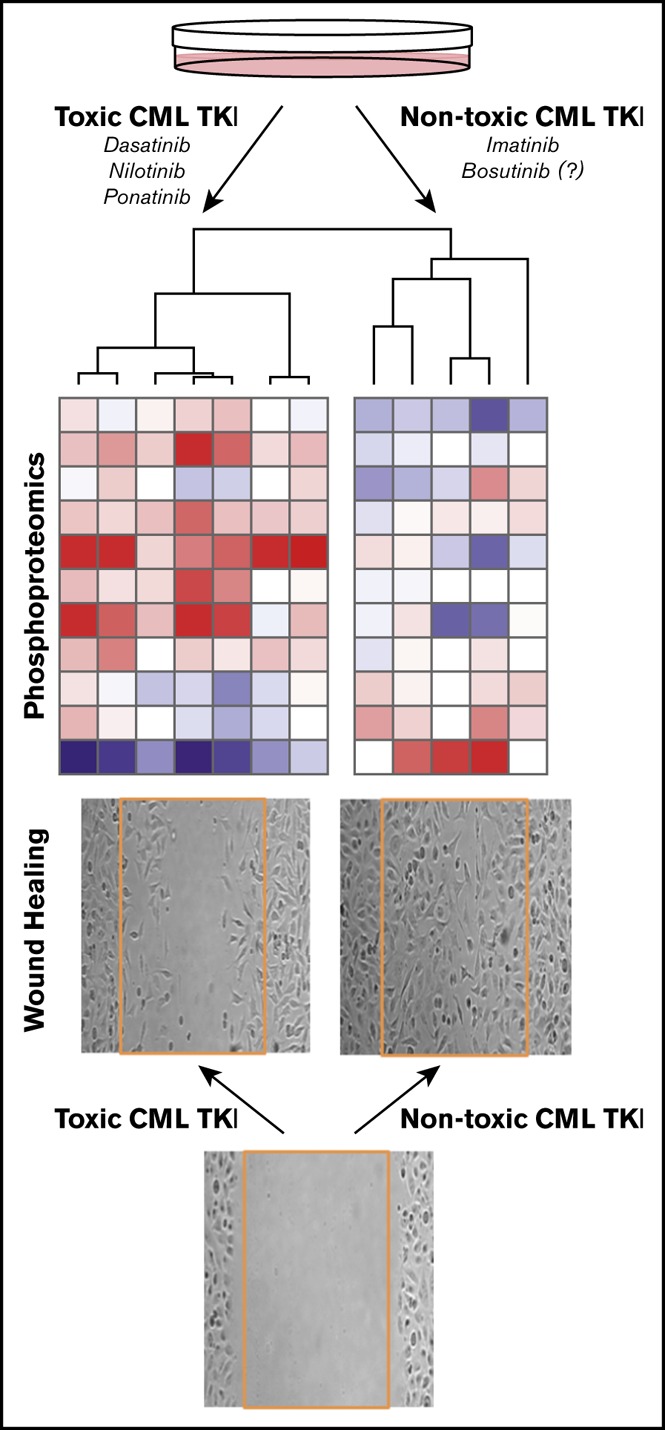

Newer CML kinase inhibitors increase ischemia risk and are toxic to endothelial cells where they produce a proteomic toxicity signature.

This phosphoproteomic EC toxicity signature predicts bosutinib to be safe, providing a potential screening tool for safer drug development.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Targeted therapies have revolutionized cancer care, often converting terminal cancers into chronic diseases. Specifically, lifelong treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients with BCR-ABL–targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has resulted in survival approaching normal life expectancy.1 Unfortunately, many targeted therapies are subsequently recognized to cause vascular toxicities.2 Although the first-generation TKI, imatinib, is safe, newer-generation inhibitors (nilotinib, dasatinib, and ponatinib) are associated with a two- to fivefold increased risk of arterial occlusive events, including heart attack, stroke, and peripheral artery occlusion.3 The molecular mechanisms are not understood, making it difficult to avoid such toxicities when developing next-generation CML therapies. As vascular events can occur years after initiating therapy, long-term follow-up of many CML patients is necessary to distinguish the background risk in this older population (average age, 64 years) from the enhanced risk induced directly by the TKI.4 Bosutinib was recently approved for first-line treatment of CML, although sufficient long-term vascular safety data are not yet available. A meta-analysis of BCR-ABL TKI trials confirmed the significant increased vascular risk with dasatinib, nilotinib, and ponatinib, but the bosutinib data were limited by insufficient power.5 This situation highlights the need for better methods to predict vascular toxicity of novel cancer therapies.

Most cardiovascular ischemic events are caused by atherosclerotic plaque rupture, resulting in arterial thrombosis.6 Healthy endothelial cells (ECs) lining blood vessels are anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic. When injured, the damaged endothelium becomes prothrombotic and promotes leukocyte adhesion until ECs heal the wound. Thus, chronic endothelial damage, from traditional risk factors or toxic drugs, can promote plaque rupture and thrombosis, resulting in ischemia. Emerging data support that vasculotoxic TKIs directly damage ECs in vitro in a dose-dependent manner and enhance atherosclerosis in rodent models.7-9 Specifically, dasatinib enhanced leukocyte adhesion molecule expression in human pulmonary ECs7 and impaired wound healing in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs),10 nilotinib impaired proliferation and survival of human coronary ECs9 and HUVECs,11 and ponatinib impaired survival and migration and increased apoptosis in HUVECs.11 Because these drugs are kinase inhibitors, we hypothesized that the vasculotoxicity of CML TKIs may be due to modulation of distinct signaling pathways in ECs when compared with nontoxic drugs, and if so, a phosphoproteomic profile could be identified to predict vascular toxicity of novel drugs.

Methods

In vitro EC assays

HUVECs were treated with vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide), dasatinib (0.2 μM), ponatinib (0.1 μM), nilotinib (3.0 μM), imatinib (4.0 μM), or bosutinib (0.5 μM) at concentrations consistent with the steady-state peak plasma concentration reported in CML patients.12-16 EC toxicity was quantified using traditional assays for leukocyte adhesion, wound healing, and EC survival.17

P100 phosphoproteomic assay

A mass spectrometry–based proteomic method was used to quantify 96 representative phosphopeptides previously validated to assess cellular states in response to drug perturbations18,19 in HUVECs treated for 3 hours with TKIs.

Detailed methods provided in supplemental Methods.

Results and discussion

HUVECs as a model to investigate vasculotoxicity of TKIs

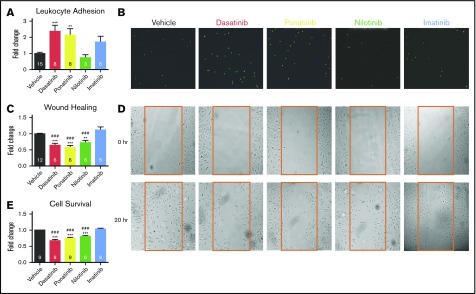

The effects of 4 approved CML TKIs on HUVEC function were compared side by side at peak concentrations using assays relevant to vascular occlusive disease. Dasatinib and ponatinib significantly increase leukocyte adhesion to ECs compared with vehicle or imatinib (Figure 1A-B), and all 3 toxic TKIs significantly impaired wound healing and cell survival (Figure 1C-E). Imatinib was not associated with HUVEC toxicity in any assay. These data are consistent with most of the literature, although nilotinib did not enhance leukocyte adhesion to HUVECs, while it increased THP1 adhesion to EA.hy ECs,10 and nilotinib did not impair wound healing in a prior study.11 The variable effect of nilotinib may be due to a steep dose–response effect on ECs that also depends on EC type,9,10 consistent with dose-dependent cardiovascular ischemia in nilotinib-treated CML patients.20 Overall, the data in Figure 1 combined with published results confirm that TKIs that are vasculotoxic in patients also impair critical functions in the HUVEC in vitro model, thereby supporting exploration of acute TKI-induced signaling changes in HUVECs to attempt to predict vasculotoxicity.

Figure 1.

HUVECs as a model for TKI-associated vascular toxicity. HUVECs were treated with clinically relevant concentrations of nontoxic imatinib and compared directly to 3 toxic TKIs (dasatinib, ponatinib, and nilotinib). (A-B) Leukocyte adhesion (A) was quantified from representative images (B) of adherent fluorescently labeled U937 leukocytes. (C-D) Wound healing (C) was determined by quantifying the number of HUVECs that migrated into the scratch wound from representative images (D) after 20 hours. (E) HUVEC survival was quantified by the Cell TiterGlo Luminescent assay. Data are presented as mean fold change ± standard error of the mean relative to vehicle-treated control. Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance and Dunnett post-test. **P < .01; ***P < .001 vs vehicle. ###P < .001 vs imatinib. The number of experiments per condition is displayed within each bar. (B,D) Original magnification ×4.

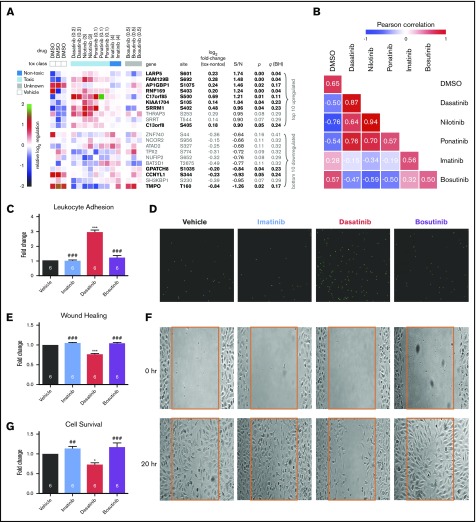

Identifying a phosphoproteomic signature that predicts EC toxicity of TKIs

HUVECs were exposed to peak plasma concentrations of each TKI for 3 hours, and 96 sentinel phosphopeptides that have been validated to be representative of cellular states in response to drug perturbations18 were interrogated by mass spectrometry; 71 of these 96 phosphopeptides could be quantified in HUVECs, and the complete phosphoproteomic data set is available at https://panoramaweb.org/project/LINCS/P100/begin.view. A previously validated signal-to-noise–based marker selection algorithm21 was used to identify phosphopeptides that distinguish between toxic TKIs (dasatinib, ponatinib, and nilotinib) and nontoxic imatinib. Phosphopeptides were rank ordered by signal-to-noise ratio (top and bottom 10 shown in Figure 2A). From those 20, the 11 peptides that discriminate the 2 classes with P < .05 (q < .25, given the small number of analytes for subsequent follow-up) were selected as sentinels of the EC toxicity signature (Figure 2A, bold).

Figure 2.

A phosphoproteomic signature of vascular toxicity predicts that bosutinib is nontoxic to human ECs in vitro. Phosphoproteomic profiling was performed on HUVECs treated with each TKI for 3 hours. (A) Marker selection was used to identify the top and bottom 10 peptides that distinguish the toxic (dasatinib, ponatinib, and nilotinib) from the nontoxic (imatinib) TKIs as ranked by signal to noise. Eleven peptides were chosen as the toxicity signature based on P < .05 and q < .25 (bold). (B) The similarity of each drug to one another based on the 11-phosphopeptide signature was calculated using averaged Pearson correlation coefficients. Bosutinib is more similar to the nontoxic TKI, imatinib. The diagonal (each drug vs itself) may be interpreted as replicate reproducibility. (C-D) Leukocyte adhesion (C) was quantified from representative images (D) of adherent fluorescently labeled U937 leukocytes. (E-F) Wound healing (E) was determined by quantifying the number of HUVECs that migrated into the scratch wound from representative images (F). (G) HUVEC survival was quantified by the Cell TiterGlo Luminescent assay. Data in panels C-F are presented as mean fold change ± standard error of the mean relative to vehicle-treated control. Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance and Dunnett post-test. *P < .05; ***P < .001 vs vehicle. ##P < .01; ###P < .001 vs dasatinib. The number of experiments per condition is displayed within each bar. (D,F) Original magnification ×4. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Using this 11-phosphopeptide “toxicity signature,” the similarity of each TKI to one another, including bosutinib, was computed (Pearson correlation; Figure 2B). As expected, the toxic TKIs were highly similar to one another and dissimilar from imatinib and vehicle. Bosutinib produced a HUVEC proteomic profile that is more similar to imatinib and vehicle than to the toxic TKIs, to which it is highly dissimilar. The predicted lack of toxicity of bosutinib based on the proteomic signature was then tested using the assays from Figure 1 and compared with imatinib as a nontoxic control and dasatinib as a toxic control. Like imatinib, bosutinib did not affect leukocyte adhesion, wound healing, or cell viability in HUVECs, and the results for bosutinib were significantly different from dasatinib (Figure 2C-G). Thus, bosutinib behaved as a TKI that is nontoxic to human ECs, as predicted by the proteomic data. Whereas there are limited data examining the endothelial effects of bosutinib, one prior study in HUVECs showed that bosutinib did not impair wound healing while dasatinib did.11 Clinical reports suggest a favorable vascular profile for bosutinib when compared with imatinib,22 but longer-term follow-up is needed.5

The intention of this study was to test the concept that proteomic profiling in human ECs can predict toxicity of novel drugs, and the results with bosutinib support the potential for such methods to be used to predict clinical risk of BCR-ABL TKIs. All systemically administered medications circulate in contact with the vascular endothelium, an important nidus for the etiology of vascular disease. Thus, if confirmed by follow-up studies, such a method has potential to predict toxicity of other drugs classes, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors that cause hypertension or antimyeloma immune-modulatory agents that promote venous thrombosis. In addition, such phosphoproteomic data could nominate underlying mechanisms driving vascular toxicity. Substantial future studies are needed to verify any mechanistic hypotheses derived from these data, yet one compelling example is the identification of TMPO as the gene/protein with the most downregulated phosphosite in HUVECs treated with toxic TKIs (Figure 2A, bottom). TMPO encodes lamina-associated polypeptide 2, which localizes lamin A to the inner nuclear membrane.23 Mutations in TMPO are associated with familial dilated cardiomyopathy,24 and lamin A mutations cause progeria, a vascular aging syndrome associated with EC dysfunction and early death from cardiovascular ischemia.25 This proof-of-concept study supports the potential of proteomic profiling of drug effects on human ECs to predict vasculotoxicity. Such a proteomic screening approach might be applied to new TKIs in the pipeline, other therapeutics in development, and nominate cotreatments to prevent the adverse vascular impact and improve long-term outcomes in cancer survivors.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgment

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health Common Fund’s Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures program (National Human Genome Research Institute grant U54HG008097) (J.D.J.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.G., Q.L., J.J.M., W.B., S.P.R., L.L., M.P., A.L.C., K.C.D., J.M., A.O., S.B.E., J.D.J., and D.D. performed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared figures; S.G., J.J.M., J.D.J., and I.Z.J. drafted the manuscript; and J.D.J. and I.Z.J. conceived of the study and provided support and oversight.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Iris Z. Jaffe, Molecular Cardiology Research Institute, Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington St, Box 80, Boston, MA 02111; e-mail: ijaffe@tuftsmedicalcenter.org.

References

- 1.Soverini S, Mancini M, Bavaro L, Cavo M, Martinelli G. Chronic myeloid leukemia: the paradigm of targeting oncogenic tyrosine kinase signaling and counteracting resistance for successful cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moslehi JJ. Cardiovascular toxic effects of targeted cancer therapies. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1457-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopal S, Miller KB, Jaffe IZ. Molecular mechanisms for vascular complications of targeted cancer therapies. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130(20):1763-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valent P, Hadzijusufovic E, Hoermann G, et al. Risk factors and mechanisms contributing to TKI-induced vascular events in patients with CML. Leuk Res. 2017;59:47-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douxfils J, Haguet H, Mullier F, Chatelain C, Graux C, Dogné JM. Association between BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukemia and cardiovascular events, major molecular response, and overall survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):625-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P, Tabas I, Fredman G, Fisher EA. Inflammation and its resolution as determinants of acute coronary syndromes. Circ Res. 2014;114(12):1867-1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guignabert C, Phan C, Seferian A, et al. Dasatinib induces lung vascular toxicity and predisposes to pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(9):3207-3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadzijusufovic E, Albrecht-Schgoer K, Huber K, et al. Nilotinib-induced vasculopathy: identification of vascular endothelial cells as a primary target site. Leukemia. 2017;31(11):2388-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sukegawa M, Wang X, Nishioka C, et al. The BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, nilotinib, stimulates expression of IL-1β in vascular endothelium in association with downregulation of miR-3p. Leuk Res. 2017;58:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreutzman A, Colom-Fernández B, Jiménez AM, et al. Dasatinib reversibly disrupts endothelial vascular integrity by increasing non-muscle myosin II contractility in a ROCK-dependent manner. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(21):6697-6707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gover-Proaktor A, Granot G, Shapira S, et al. Ponatinib reduces viability, migration, and functionality of human endothelial cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(6):1455-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Futosi K, Németh T, Pick R, Vántus T, Walzog B, Mócsai A. Dasatinib inhibits proinflammatory functions of mature human neutrophils. Blood. 2012;119(21):4981-4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Shah NP, et al. Ponatinib in refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(22):2075-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fava C, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Jabbour E. Development and targeted use of nilotinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2009;2:233-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larson RA, Druker BJ, Guilhot F, et al. ; IRIS (International Randomized Interferon vs STI571) Study Group. Imatinib pharmacokinetics and its correlation with response and safety in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a subanalysis of the IRIS study. Blood. 2008;111(8):4022-4028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbas R, Hsyu PH. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of bosutinib. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2016;55(10):1191-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett Mueller K, Lu Q, Mohammad NN, et al. Estrogen receptor inhibits mineralocorticoid receptor transcriptional regulatory function. Endocrinology. 2014;155(11):4461-4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abelin JG, Patel J, Lu X, et al. Reduced-representation phosphosignatures measured by quantitative targeted MS capture cellular states and enable large-scale comparison of drug-induced phenotypes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(5):1622-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litichevskiy L, Peckner R, Abelin JG, et al. A library of phosphoproteomic and chromatin signatures for characterizing cellular responses to drug perturbations. Cell Syst. 2018;6(4):424-443.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochhaus A, Saglio G, Hughes TP, et al. Long-term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5-year update of the randomized ENESTnd trial. Leukemia. 2016;30(5):1044-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould J, Getz G, Monti S, Reich M, Mesirov JP. Comparative gene marker selection suite. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(15):1924-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortes JE, Jean Khoury H, Kantarjian H, et al. Long-term evaluation of cardiac and vascular toxicity in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias treated with bosutinib. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(6):606-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naetar N, Ferraioli S, Foisner R. Lamins in the nuclear interior - life outside the lamina. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(13):2087-2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor MR, Slavov D, Gajewski A, et al. ; Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry Research Group. Thymopoietin (lamina-associated polypeptide 2) gene mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat. 2005;26(6):566-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shumaker DK, Dechat T, Kohlmaier A, et al. Mutant nuclear lamin A leads to progressive alterations of epigenetic control in premature aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(23):8703-8708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.