Abstract

The link between Zika virus infection during pregnancy and microcephaly and other neurodevelopmental defects in infants, referred to as congenital Zika syndrome (CZS), was recently discovered. One key question that remains is whether such neurodevelopmental abnormalities are limited to the recently evolved Asiatic ZIKV strains or if they can also be induced by endemic African strains. Thus, we examined birth registries from one particular hospital from a country in West Africa, where ZIKV is endemic. Results showed a seasonal pattern of birth defects that is consistent with potential CZS, which correspond to a range of presumed maternal infection that encompasses both the peak of the warm, rainy season as well as the months immediately following it, when mosquito activity is likely high. While we refrain from definitively linking ZIKV infection and birth defects in West Africa at this time, in part due to scant data available from the region, we hope that this report will initiate broader surveillance efforts that may help shed light onto mechanisms underlying CZS.

Keywords: Zika virus; ZIKV; birth defects; microcephaly; congenital Zika syndrome; West Africa; seasonality

Introduction

Since 2015, when an initial link between Zika Virus (ZIKV) and microcephaly was discovered in Brazil, the term congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) has been coined to reflect a broad range of Zika-linked neurodevelopmental damages 1 beyond microcephaly 1– 3, including ocular 4, 5 and auditory defects 6, 7. The overall risk of Zika-linked birth defects has been estimated at ~10% and 15% for infections during the 1st trimester 8, potentially impacting thousands of infants in the US and US territories alone. Concerns exist that ZIKV-related outcomes are underreported, particularly when ZIKV infections result in neurodevelopmental abnormalities without visible microcephaly (e.g., developmental delays and learning disabilities that would not be immediately noticeable 9– 11). Such outcomes are likely not recorded, particularly if the causative infection was asymptomatic 12. Further, a recent CDC report that examined birth defect records from 15 US jurisdictions showed a statistically significant increase in prevalence of birth defects potentially consistent with CZS in areas with documented local ZIKV transmission in the second half of 2016 13. Notably, the majority of infants and fetuses with birth defects potentially related to ZIKV infection in this report lacked ZIKV infection testing, which may be in part attributed to lack of known maternal exposure or other such indicators 14. Nonetheless, these findings are alarming and underscore not only the need for continued monitoring and surveillance, but also the need to better understand the full extent – as well as mechanisms – of neurodevelopmental defects associated with CZS.

Can we expect to find cases of congenital Zika syndrome in the African Continent?

Currently our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie CZS remains limited, including the possibility that ZIKV infection is a necessary but insufficient condition for CZS 15. One key question is whether ZIKV-mediated birth defects are associated with a specific strain of ZIKV, which, for example, could have evolved after ZIKV migrated from South East Asia to French Polynesia and Brazil 16. However, other studies suggest that African strains are likely to be as pathogenic as the Asiatic strains (e.g., 17, 18). Thus, the lack of connection between ZIKV infection in pregnancy and birth defects prior to the 2015–16 Brazilian outbreak may instead be attributable to the benign nature of ZIKV infection in adults 19 and lack of surveillance, among other factors. This can be illustrated by a report of a handful of birth defects in Hawaii in 2009–2012, which now has been shown to be associated with ZIVK infection, but was undetected as such until the Brazilian microcephaly epidemic brought ZIKV into the spotlight 20.

Earlier studies from the African Continent – where ZIKV is endemic – have documented a relatively high prevalence of ZIKV antibodies in human populations (e.g., Nigeria 21, Sierra-Leone 22). Despite this, there exists negligible data regarding CZS across the African Continent; nevertheless, lack of evidence should not be taken as definitive proof of absence 17. Thus, here we examine birth registries from one particular hospital in West Africa from a country considered by the WHO to be at medium risk of a ZIKV outbreak 23. As there are ongoing security concerns in this location, to ensure the safety of the hospital and staff, the hospital name and location have been kept anonymous. The study was approved by the Committee on Administration of the hospital in lieu of a functioning Ethics Committee.

Case study: seasonality of CZS-type birth defects in a hospital in West Africa

Risk of major neurodevelopmental defects, such as microcephaly, appears to be particularly high if vertical transmission occurs during the first trimester, especially within a “vulnerability window” around 12 weeks (10 to 14 weeks) post-conception 8, 24. Thus, we hypothesized that – similar to seasonal malaria infections, which peak a few weeks following abundant rainfalls during the “rainy” season, typically from August through October in the study region 25, 26 – seasonal variations in the number of CZS-type birth defects would be detectable from the aforementioned hospital data. Such expectations are consistent with prior findings from Senegal (West Africa) 27 and Kenya (East Africa) 28, where Rift Valley Fever epizootics were associated with heavy rainfalls. Our hypothesis was further informed by the temporal relationships between the number of ZIKV infections and microcephaly cases reported in Brazil 29. We expected that the peak of CZS-type birth defects (such as documented cases of microcephaly and/or stillbirth) would coincide with vertical ZIKV transmission at around 12-weeks post-conception during the peak of the rainy season, assuming an approximate 3-week lag between maternal infection and vertical transmission 30, as suggested by data from Brazil in 2015 31.

Methods

A total of 13445 birth registries (2009–2015) from a non-governmental hospital in West Africa were examined to determine whether we could identify a seasonal pattern of birth defects potentially attributable to ZIKV infection (i.e., CZS-type birth defects). The number of births and respective outcomes (i.e., live birth versus stillbirth) and reported complications (i.e., fetal malformation, breech, etc.) were collated by month/year. Reporting standards for birth complications varied between years; thus, we focused exclusively on visible neurodevelopmental complications (such as microcephaly) and pregnancy losses (such as stillbirth) that could be attributed to potential CZS 1, 2 ( Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). To infer the “vulnerability window” of 12 weeks (spanning 10 to 14 weeks) post-conception, we assumed that births that were not reported as premature in the records were full-term, thus enabling us to infer the likely month of conception 29.

We also considered national average monthly temperature and rainfall data for the study years, collected from the World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal database. These values were treated as proxy indicators for mosquito activity in the hospital catchment area at time of maternal infection. To visualize any relevant trends, we plotted these data, as well as the average percentage of birth defects consistent with potential CZS by month.

Results and discussion

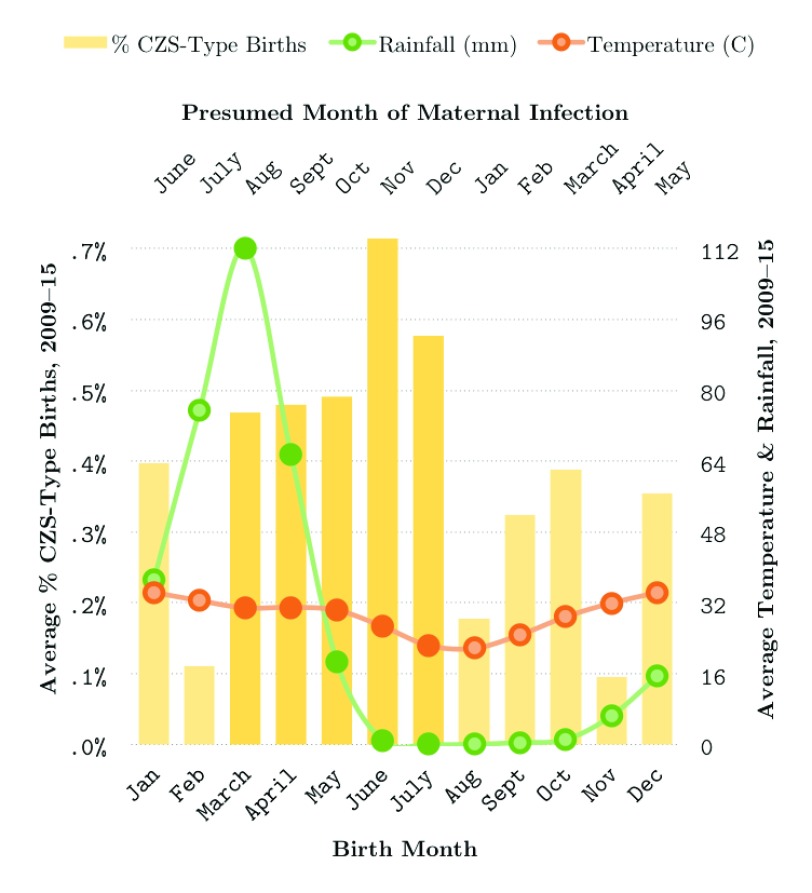

As shown in Figure 1, the average percentage of births consistent with potential CZS demonstrates a marked peak between March and July, which places maternal month of infection between August and December of the previous year. These months encompass the peak and latter half of the warm, rainy season (August–October) as well as the first half of the cool, dry season that immediately follows (October–December) in the study region, which likely represent months with considerable mosquito activity. Notably, the hospital from which these birth defects data were acquired generally experiences a peak in childhood malaria cases every October, which falls squarely in the middle of the August to December range of presumed maternal month of ZIKV infection determined here.

Figure 1. Average birth defects consistent with congenital Zika syndrome per month, with corresponding average daily temperatures and rainfall during presumed maternal month of infection.

With this in mind, the early months of the cool, dry season (October–December) are likely hospitable enough for mosquito vectors to thrive and spread pathogens, including ZIKV; this may explain why the range of our presumed maternal month of infection (August–December) extends past the rainy season, given that mosquitoes require a balanced environment for survival, including both moderate rainfall and optimal temperatures 32.

Our results suggest that a seasonal pattern exists with respect to CZS-type birth defects reported in the study region ( Figure 1), where the largest fraction of said defects appear to occur in the months of March through July. Furthermore, this pattern can be linked to ecological evidence, such as rainfall and temperature trends that likely facilitate maternal ZIKV infection. While consistent with the expectation that some of these defects might be attributable to (unreported) ZIKV infections that occurred early in pregnancy (and indeed resemble temporal patterns from studies in Brazil 29), our findings stop short of definitively linking ZIKV infection and birth defects in the study region, in part due to scant data. Instead, by reviewing the potential limitations of the data analyzed here, we hope that this report will initiate broader surveillance efforts that may help shed light onto mechanisms that underlie CZS, including utilization of data that might already be available across various African countries where ZIKV is endemic and/or competent vectors exist (e.g., Gabon 33, Central African Republic 34). For example, a recent WHO Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies 35 reported a number of microcephaly cases from Angola (a country listed in the High risk category 23) that appear to be linked to ZIKV infection, despite the lack of direct PCR confirmation from the specimens. Due to only recent implementation of active surveillance in the country, the true magnitude of the event is not yet clearly understood. Nonetheless, it is important for insights into a broader pattern of potential CZS defects, despite the lack of experimental ZIKV infection confirmation or lack of evidence of ongoing active ZIKV transmission in Angola (i.e. only two ZIKV cases were reported from Angola in early 2017 36).

Several conservative assumptions made in this analysis, such as assuming a gestation period of ~9 months, or not classifying “low birth weights” (which may represent full-term births of ZIKV-infected fetuses) as a CZS-type birth defect, would likely lead to underestimation of potential trends, if any. We also assumed that the available birth records were representative of the pregnancy/birth patterns that occur across the entire region. Other limitations of the available data are related to the standard of care that is feasible in much of West Africa, including (i) lack of family history and/or genetic testing for mutations in loci responsible for primary microcephaly; (ii) lack of laboratory evidence or testing for ZIKV and/or other infections, including TORCH agents 37, 38, often due to inability to pay for testing (e.g., 39); and (iii) lack of detailed clinical prenatal history, including whether rash and/or other symptoms of Zika infection were present at any point during pregnancy. This final limitation may be considered minor, given that the majority of ZIKV infections are asymptomatic 19, 24. Additionally, no data were available regarding other clinically relevant factors that are also associated with microcephaly 40, such as history of excessive alcohol consumption or recreational drug use, and/or prolonged exposure to pesticides, such as pyriproxyfen. However, the former life-style factors are unlikely to have a seasonal effect spanning several years, and the role of the latter factor as a causative agent of microcephaly remains unclear 41. There is also a lack of precise ecological data, including estimates of rainfalls in the hospital catchment area, the distribution and feeding habits of mosquitoes, and whether or not said mosquitoes carry ZIKV, as well as data regarding ZIKV prevalence in the human population.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that using the data we already have – even in the absence of formal surveillance systems for CZS – can provide compelling, introductory insights. In the future, work that employs existing data from hospitals across the African continent – which encompasses countries with a variety of climates, dry and rainy seasons, and suitability for widespread mosquito habitats – should be pursued.

Data availability

Figshare : Data for Figure 1. Average birth defects consistent with congenital Zika syndrome per month, with corresponding average daily temperatures and rainfall during presumed maternal month of infection. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.5387029. Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Funding Statement

This work was partially supported by the Research Seed Award from Kent State University (to HP) and by Research For Health, Inc. (to RH).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; referees: 3 approved with reservations]

Supplementary material

Supplemental Table 1. A list of birth complications (as recorded in the health records) consistent with potential congenital Zika syndrome.

Supplemental Table 2. A list of birth complications (as recorded in the health records) that are not consistent with potential congenital Zika syndrome and/or missing.

References

- 1. Melo AS, Aguiar RS, Amorim MM, et al. : Congenital Zika Virus Infection: Beyond Neonatal Microcephaly. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(12):1407–1416. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lucey D, Cummins H, Sholts S: Congenital Zika Syndrome in 2017. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1368–1369. 10.1001/jama.2017.1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moore CA, Staples JE, Dobyns WB, et al. : Characterizing the Pattern of Anomalies in Congenital Zika Syndrome for Pediatric Clinicians. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(3):288–295. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh PK, Guest JM, Kanwar M, et al. : Zika virus infects cells lining the blood-retinal barrier and causes chorioretinal atrophy in mouse eyes. JCI Insight. 2017;2(4):e92340. 10.1172/jci.insight.92340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Culjat M, Darling SE, Nerurkar VR, et al. : Clinical and Imaging Findings in an Infant With Zika Embryopathy. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):805–811. 10.1093/cid/ciw324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glantz G: Zika and Hearing Loss: The Race for a Cure Continues. Hear J. 2016;69(12):22–24. 10.1097/01.HJ.0000511123.79295.d0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leal MC, Muniz LF, Ferreira TS, et al. : Hearing Loss in Infants with Microcephaly and Evidence of Congenital Zika Virus Infection - Brazil, November 2015–May 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(34):917–919. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6534e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reynolds MR, Jones AM, Petersen EE, et al. : Vital Signs: Update on Zika Virus-Associated Birth Defects and Evaluation of All U.S. Infants with Congenital Zika Virus Exposure - U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(13):366–373. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6613e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vogel G: INFECTIOUS DISEASE. Experts fear Zika’s effects may be even worse than thought. Science. 2016;352(6292):1375–1376. 10.1126/science.352.6292.1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hotez PJ: What Does Zika Virus Mean for the Children of the Americas? JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(8):787–789. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soares de Souza A, Moraes Dias C, Braga FD, et al. : Fetal Infection by Zika Virus in the Third Trimester: Report of 2 Cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(12):1622–1625. 10.1093/cid/ciw613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hotez P, Aksoy S: Will Zika become the 2016 NTD of the Year?Blog, posted January 7, 2016 by Peter Hotez and Serap Aksoy.2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delaney A, Mai C, Smoots A, et al. : Population-Based Surveillance of Birth Defects Potentially Related to Zika Virus Infection - 15 States and U.S. Territories, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(3):91–96. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6703a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fitzgerald B, Boyle C, Honein MA: Birth defects potentially related to Zika virus infection during pregnancy in the United States. JAMA. 2018. 10.1001/jama.2018.0126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Oliveira WK, Carmo EH, Henriques CM, et al. : Zika Virus Infection and Associated Neurologic Disorders in Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1591–1593. 10.1056/NEJMc1608612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Faria NR, Quick J, Claro IM, et al. : Establishment and cryptic transmission of Zika virus in Brazil and the Americas. Nature. 2017;546(7658):406–410. 10.1038/nature22401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nutt C, Adams P: Zika in Africa-the invisible epidemic? Lancet. 2017;389(10079):1595–1596. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31051-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu Z, Chan JF, Tee KM, et al. : Comparative genomic analysis of pre-epidemic and epidemic Zika virus strains for virological factors potentially associated with the rapidly expanding epidemic. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e22. 10.1038/emi.2016.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, et al. : Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2536–2543. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumar M, Ching L, Astern J, et al. : Prevalence of Antibodies to Zika Virus in Mothers from Hawaii Who Delivered Babies with and without Microcephaly between 2009–2012. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(12):e0005262. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fagbami AH: Zika virus infections in Nigeria: virological and seroepidemiological investigations in Oyo State. J Hyg (Lond). 1979;83(2):213–219. 10.1017/S0022172400025997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robin Y, Mouchet J: [Serological and entomological study on yellow fever in Sierra Leone]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1975;68(3):249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. WHO, World Health Organization: Zika Virus risk assessment in the WHO African Region: a technical report. February 2016.2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 24. Honein MA, Dawson AL, Petersen EE, et al. : Birth Defects Among Fetuses and Infants of US Women With Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy. JAMA. 2017;317(1):59–68. 10.1001/jama.2016.19006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brewster DR, Greenwood BM: Seasonal variation of paediatric diseases in The Gambia, west Africa. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1993;13(2):133–146. 10.1080/02724936.1993.11747637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sivakumar MVK: Predicting rainy season potential from the onset of rains in Southern Sahelian and Sudanian climatic zones of West Africa. Agr Forest Meteorol. 1988;42(4):295–305. 10.1016/0168-1923(88)90039-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilson ML, Chapman LE, Hall DB, et al. : Rift Valley fever in rural northern Senegal: human risk factors and potential vectors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50(6):663–675. 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davies FG, Linthicum KJ, James AD: Rainfall and epizootic Rift Valley fever. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63(5):941–943. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reefhuis J, Gilboa SM, Johansson MA, et al. : Projecting Month of Birth for At-Risk Infants after Zika Virus Disease Outbreaks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(5):828–832. 10.3201/eid2205.160290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lessler J, Chaisson LH, Kucirka LM, et al. : Assessing the global threat from Zika virus. Science. 2016;353(6300):aaf8160. 10.1126/science.aaf8160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Q, Sun K, Chinazzi M, et al. : Spread of Zika virus in the Americas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(22):E4334–E4343. 10.1073/pnas.1620161114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blanford JI, Blanford S, Crane RG, et al. : Implications of temperature variation for malaria parasite development across Africa. Sci Rep. 2013;3: 1300. 10.1038/srep01300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grard G, Caron M, Mombo IM, et al. : Zika virus in Gabon (Central Africa)--2007: a new threat from Aedes albopictus? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(2):e2681. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berthet N, Nakouné E, Kamgang B, et al. : Molecular characterization of three Zika flaviviruses obtained from sylvatic mosquitoes in the Central African Republic. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14(12):862–865. 10.1089/vbz.2014.1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. WHO: Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, Week 48: 25 November – 1 December 2017.2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 36. WHO: Zika situation report. 20 January 2017.2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coyne CB, Lazear HM: Zika virus - reigniting the TORCH. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(11):707–715. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vouga M, Baud D: Imaging of congenital Zika virus infection: the route to identification of prognostic factors. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36(9):799–811. 10.1002/pd.4880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eballé AO, Ellong A, Koki G, et al. : Eye malformations in Cameroonian children: a clinical survey. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:1607–1611. 10.2147/OPTH.S36475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Calvet G, Aguiar RS, Melo ASO, et al. : Detection and sequencing of Zika virus from amniotic fluid of fetuses with microcephaly in Brazil: a case study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(6):653–660. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00095-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bar-Yam Y, Nijhout HF, Parens R, et al. : The Case for Pyriproxyfen as a Potential Cause for Microcephaly; From Biology to Epidemiology. arXiv preprint arXiv: 170303765.2017. 10.1101/115279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]