Abstract

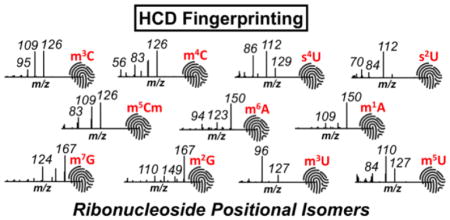

The analytical identification of positional isomers (e.g., 3-, N4-, 5-methylcytidine) within the >160 different post-transcriptional modifications found in RNA can be challenging. Conventional liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) approaches rely on chromatographic separation for accurate identification because the collision-induced dissociation (CID) mass spectra of these isomers nearly exclusively yield identical nucleobase ions (BH2+) from the same molecular ion (MH+). Here we have explored higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) as an alternative fragmentation technique to generate more informative product ions that can be used to differentiate positional isomers. LC-MS/MS of modified nucleosides characterized using HCD led to the creation of structure- and HCD energy-specific fragmentation patterns that generated unique fingerprints, which can be used to identify individual positional isomers even when they cannot be separated chromatographically. While particularly useful for identifying positional isomers, the fingerprinting capabilities enabled by HCD also offer the potential to generate HPLC-independent spectral libraries for the rapid analysis of modified ribonucleosides.

Keywords: RNA modification, positional isomers, nucleoside analysis, LC-MS/MS, HCD fragmentation

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Over 160 types of post-transcriptional nucleoside modifications have been documented in various types of ribonucleic acid (RNA).[1] These chemical modifications range from simple methylation or thiolation to complex hypermodifications. They are added mostly to the nucleobase (except for ribose methylation) through simple or complex enzymatic pathways. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is now viewed as the gold standard analytical platform for both identification [1–5] and quantification [6–10] of modified ribonucleosides.

As noted extremely early in the development of LC-MS methods for modified nucleosides,[11] collision-induced dissociation (CID) of the protonated molecular ion (MH+) more often than not leads to fragmentation at the N-glycosidic bond of ribonucleosides generating a diagnostic nucleobase ion (BH2+). This nearly universal fragmentation pathway enables one to differentiate modifications that reside on the nucleobase (leading to neutral loss of an unmodified ribose at 132 Da) or modification on the ribose (typically methylation leading to a neutral loss of 146 Da). Various laboratories have exploited this feature to create powerful analytical platforms for the identification of known and detection of previously unknown modifications.[3, 8, 12–14]

Despite the demonstrated utility of CID-based LC-MS/MS of modified nucleosides from RNA, it is well understood that chromatographic reproducibility and resolving power are necessary to deal with modified nucleosides that exist as positional isomers, as the common MH+ to BH2+ transitions for such isomers yield equivalent mass spectral responses. Of all the ribonucleoside modifications, methylations are the most abundant class of positional isomers.[1] For example, the isomers of methylcytidine (3-, N4-, and 5-methylcytidine) are indistinguishable based on the evaluation of m/z of MH+ and BH2+ ions alone from the mass spectra. Such positional isomers of methylations observed in vivo have significant biological relevance. For instance, m5C, commonly found in the anticodon loop of archaeal and eukaryotic tRNAs, is linked to structural and metabolic stabilization of the tRNA.[15] Therefore, distinguishing positional isomers helps delineate the functional impact of a specific modification.

Typically, the analyst will rely on previously reported chromatographic behavior [1, 6, 11] or the use of analytical standards to identify and differentiate modified nucleosides that can be present as positional isomers. Another approach used in distinguishing positional isomers is multistage fragmentation (MSn),[16,17] where analysis of the data generated by second and third (or more) stages of dissociation can discriminate among different structural possibilities. However, acquisition of sequential fragmentation events impacts the duty cycle of analysis, which can hinder accurate qualitative and quantitative measurements for co-eluting nucleosides. Another technique to address the challenge of ribonucleoside positional isomers is the inclusion of ion mobility separation prior to MS/MS.[17] Here, cross sectional area of the analyte allows for a gas-phase separation, although it remains to be seen if all ribonucleoside positional isomers are amenable to separation in this manner.

Orbitrap-based mass analyzers are equipped with an ion routing multipole (IRM), a multipurpose ion storage device that has an increased peak-to-peak radiofrequency to retain a wider range of m/z values compared to traditional linear ion trap devices.[18, 19] The IRM enables an optional fragmentation mode, higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD), during accumulation of ions.[19] Due to the increased trapping capability of the IRM, HCD MS/MS spectra yield beam type instrument characteristics (i.e., pseudo-MS3).[20] Such pseudo-MS3 approaches provide improved efficiency for structural elucidation of small molecules.[21]

Given the scientific interest in modified ribonucleosides along with the ever-increasing sample types being studied,[22–24] we have been interested in establishing analytical platforms that can be used for the identification and characterization of known and unknown modifications that would be independent of (or significantly less dependent on) separation techniques and protocols. Based on the prior findings of Jensen and co-workers regarding the utility of MSn fragmentation for nucleoside identification[16] combined with the proven capabilities of HCD, in this work we investigated whether the conventional LC-MS/MS approach for nucleoside analysis could be enhanced by using HCD in place of CID. We found conditions for HCD that mimicked CID-type fragmentation, thereby allowing previous neutral loss techniques to still be applied during LC-MS/MS analyses. More significantly, we report that at higher energy values, HCD generates pseudo-MSn product ion spectra that can be used to differentiate positional isomers, even when those isomers would co-elute during LC-MS/MS. Building on that finding, we propose that HCD can be used to generate nucleoside-specific fingerprints, which can enable spectral library matching for any modified ribonucleoside. By using only mass spectrometry data for nucleoside identification, the chromatographic (or separation) conditions can now be more easily optimized around assay needs (e.g., speed or elution order) without requiring additional method development steps based on known nucleoside standards.

Materials and Methods

Cytidine (C), 3-methylcytidine (m3C), N4-methylcytidine (m4C), 5-methylcytidine (m5C), adenosine (A), 1-methyladensoine (m1A), 2-methyladenosine (m2A), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), 8-methyladensine (m8A), guanosine (G), 1-methylguanosine (m1G), 2-methylguanosine (m2G), 7-methylguanosine (m7G), uridine (U), 3-methyluridine (m3U), 5-methyluridine (m5U), 2-thiouridine (s2U), and 4-thiouridine (s4U) were purchased from Carbosynth (Compton, UK). E. coli MRE 600 tRNA, LC-MS grade ammonium acetate, ammonium formate and ammonium bicarbonate, along with nuclease P1 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). LC-MS grade water was obtained from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). LC-MS grade acetonitrile was acquired from Honeywell Burdick & Jackson (Morris Plain, NJ). LC-MS grade formic acid was obtained from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Phosphodiesterase I and alkaline phosphatase were purchased from Worthington (Lakewood, NJ).

LC-MS/MS analysis of nucleosides

Analysis of nucleosides was carried out by LC-MS/MS. An ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system (Vanquish Flex Quaternary, Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) was used. Reversed phase chromatography was carried out using a high strength silica column (Acquity UPLC HSS T3, 1.8 μm, 1.0 mm × 50 mm, Waters, Milford, MA). Three different mobile phase conditions were studied. LC method 1 was composed of 5.3 mM ammonium formate in water, pH 4.5, as mobile phase A (MPA), and a mixture of acetonitrile/water (40:60) with 5.3 mM ammonium formate as mobile phase B (MPB). LC method 2 consisted of 0.1% v/v formic acid in water, pH 3.0, as MPA, and a mixture of acetonitrile/water (40:60) with 0.1% v/v formic acid as MPB. LC method 3 employed 5.3 mM ammonium acetate in water, pH 5.3, as MPA, and a mixture of acetonitrile/water (40:60) with 5.3 mM ammonium acetate as MPB.

The gradient program employed in all three mobile phase conditions consisted of: 0% B (from 0 to 6.3 min), 2% B at 13.1 min, 3% B at 16 min, 5% B at 21.4 min, 25% B at 24.6 min, 50% B at 26.9 min, 75% B at 30.2 min (hold for 0.3 min), 99% B at 33 min (hold for 6 min), then returning to 0% B at 39 min. After that, a re-equilibration step at 0% B for 16 min was employed prior to the next injection. A flow rate of 60 μL min−1 was used. The column temperature was set at 30 °C.

Individual nucleosides were resuspended in MPA at a concentration of 20 ng μL−1. m3C, m4C and m5C were also prepared in MPA at 5 ng μL−1. Additionally, a mixture of m4C and m5C (20 ng μL−1 each) was prepared in MPA. Four micrograms of E. coli tRNA were hydrolyzed to nucleosides as previously reported.[25] The solutions were individually analyzed by injecting 1 μL (standard nucleosides) or 5 μL (E. coli hydrolysate) on column.

An Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) interfaced with a heated electrospray (H-ESI) source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. The analyses were carried out in positive polarity. Full scan data was acquired at a resolution of 120,000, mass range 220–900 m/z, automatic gain control (AGC) 7.5 × 104, and injection time (IT) 100 ms. Data dependent top speed MS/MS (1 s cycle) were acquired at a resolution of 15,000, AGC 1.0 × 104, and IT 200 ms. Depending on the experimental goal, CID or HCD was employed for MS/MS fragmentation. The collision energy setting for CID may range from 0 to 100%, while for HCD it may range from 0 to 200 arbitrary units. The other instrumental conditions were: quadrupole isolation of 1.5 m/z; ion funnel radiofrequency (RF) level 35%; sheath gas, auxiliary gas, and sweep gas of 30, 10 and 0 arbitrary units, respectively; ion transfer tube temperature of 289 °C; vaporizer temperature of 92 °C; and spray voltage of 3.5 kV.

Data processing was done using the Qual browser of Xcalibur 3.0. Accurate m/z values of the precursor and fragment ions were computed by ChemCalc (http://www.chemcalc.org).

Results and Discussion

Model Isomeric Nucleoside Fragmentation in CID and HCD

Reliable and reproducible chromatographic conditions are a requirement for retention time-based differentiation of positional isomers of base-modified nucleosides, due to their identical MH+ and BH2+ ions during mass spectrometry.[6] We initially evaluated CID conditions within the orbitrap to explore the possibility of finding product ions (single or a pattern of multiple) that could uniquely be applied to a specific positional isomer. A change of relative collision energy (CE) from 40% to 100% during CID did not affect the fragmentation pattern as the nucleoside precursor ions yielded nucleobase product ions without exhibiting any other fragment ions (data not shown). Based on the known features of HCD,[18, 19] we reasoned that the HCD capability to trap low mass ions could enable their detection following fragmentation of the nucleobase in multiple pathways at optimal collisional energies. At lower CEs, the HCD-based tandem mass spectrum for ribonucleosides was indistinguishable from that of CID-based tandem mass spectrum (CID-like MS/MS spectra). This observation suggests that HCD can be used for acquiring CID-like MS/MS spectra through conventional N-glycosidic bond cleavage. However, at a CE of 80, low m/z fragment ions were detected, which could potentially be originating from the nucleobase in the HCD-based MS/MS spectrum (e.g., m5C in Supplemental Figure S1). Thus, HCD may offer the potential for both conventional, CID-like MS/MS analysis of modified nucleosides along with additional, higher-energy ring fragmentation that can be used for differentiating structural isomers.

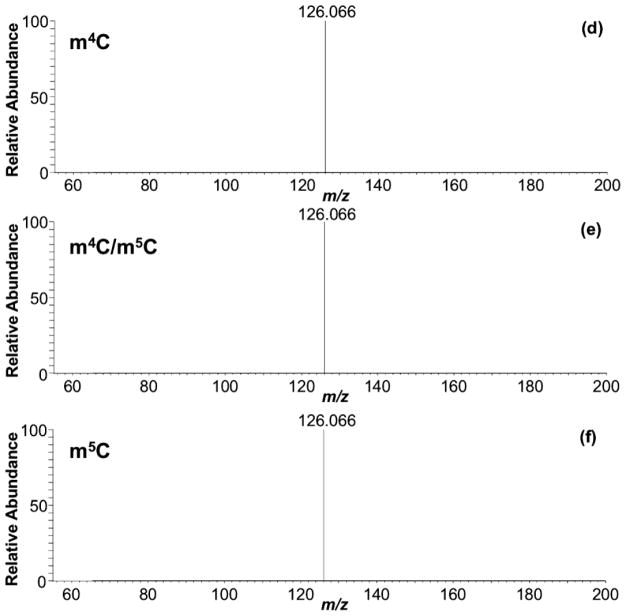

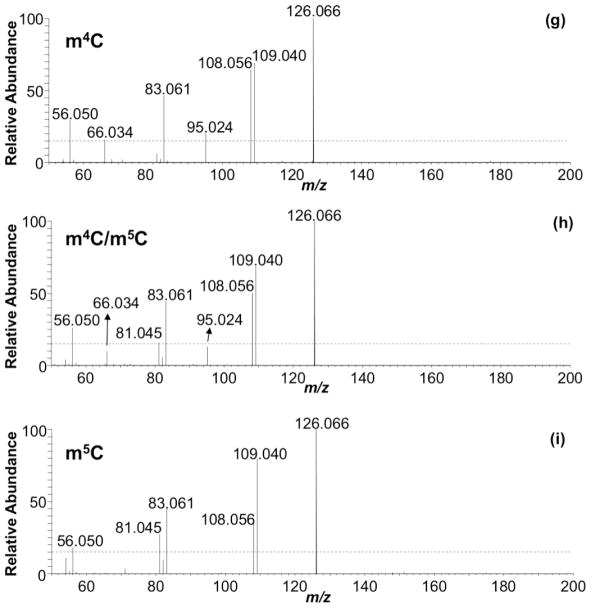

To establish the potential utility of HCD to provide information beyond CID, we initially examined the fragmentation pattern of positional isomers of base-methylated cytidine (m3C, m4C, and m5C) and their reproducible nature in higher-energy HCD-based MS/MS spectra (Table 1). The observed variance in the relative ion abundance (RIA) of product ions was computed for each of positional isomers. The mean and relative standard deviations (RSDs) calculated for the RIAs of non-unique product ions at m/z 126.0667, 109.0402, 108.0562, 83.0609, 82.0293, 81.0453, 56.0500, and 54.0344 are shown in Table 1. These data include replicate analysis (n=5) at different times of the same day for a fixed LC condition (i.e., LC method 1) and fixed amount of nucleoside injected on column (20 ng). Intraday study data (n=20) were also compared against data acquired in two different days employing LC method 1 or LC method 2. The effect of sample amount injected on column was also investigated (i.e., 5 or 20 ng).

Table 1.

RIAs of the non-unique ions with m/z 126.0662, 109.0307, 108.0557, 83.0605, 82.0288, 81.0448, 56.0494, and 54.0337 observed in the HCD MS/MS spectra of m3C, m4C and m5C. Mean and RSD were calculated by accounting data acquired intraday though the analysis of replicates (n=5), and interday (2 different days) where different amount of nucleoside (i.e., 5 and 20 ng) and different LC conditions (i.e., LC method 1 and 2) were employed for the analysis (n=20). m/z represented are based on theoretical calculations.

|

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraday (n=5) | Interday and different conditions (n=20) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| m3C | m4C | m5C | m3C | m4C | m5C | |||

|

|

||||||||

| Non-unique ion m/z | 126.0667 | 100 ± 0.5 | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 99 ± 2.3 | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | |

| 109.0402 | 97 ± 3.5 | 62 ± 6.2 | 85 ± 6.2 | 98 ± 2.6 | 63 ± 5.8 | 83 ± 4.6 | ||

| 108.0562 | 2.3 ± 19 | 63 ± 4.1 | 36 ± 8.6 | 2.2 ± 19 | 63 ± 4.4 | 36 ± 5.5 | ||

| 83.0609 | 6.1 ± 7.5 | 47 ± 5.0 | 45 ± 7.0 | 6.3 ± 6.9 | 46 ± 5.8 | 44 ± 5.6 | ||

| 82.0293 | 4.8 ± 10 | 3.4 ± 8.2 | 9.5 ± 15 | 4.7 ± 16 | 3.3 ± 13 | 9.9 ± 11 | ||

| 81.0453 | 3.4 ± 10 | 7.4 ± 9.7 | 26 ± 11 | 3.3 ± 16 | 7.2 ± 11 | 26 ± 9.9 | ||

| 56.0500 | 2.9 ± 8.5 | 29 ± 7.0 | 16 ± 12 | 2.5 ± 18 | 29 ± 8.8 | 16 ± 10 | ||

| 54.0344 | 1.5 ± 18 | 2.1 ± 29 | 9.5 ± 17 | 1.7 ± 26 | 2.1 ± 25 | 8.8 ± 14 | ||

|

|

||||||||

The examination of the data acquired under these various conditions revealed that the product ions with an RIA ≥ 15% exhibited low RSDs (≤ 12%) while the product ions present at lower levels (RIA of <15%) were less reproducible (RSD ≤ 29%). Based on these reproducibility findings, an RIA minimum threshold of 15% was identified as appropriate for development of an HCD-based nucleoside product ion fingerprinting approach. Further, these results demonstrate that this HCD-based approach should be relatively unaffected by experimental parameters such as chromatographic method, analyte retention factor, sample amount and precursor ion abundance.

Evaluation of the HCD MS/MS spectra of m3C, m4C, and m5C revealed that most of the observed product ions in the current study correspond well with those reported by Jensen et al.[16] in their CID-based MS3 analysis of the methylated cytosine base ion, (BH2+, m/z 126.1). For example, they reported the product ions for m3C (at m/z 109.1, 95.1, 83.1 and 69.2), for m4C (at m/z 109.1, 108.1, 95.1, and 83.2) and m5C (at m/z 109.1, 108.1, 83.4, and 81.4). Almost all of these product ions exhibited an RIA of ≥ 15% in the HCD MS/MS spectra in this work, except the product ions at m/z 83.1 and 69.2 for m3C. These observations suggest the pseudo-MSn nature of the HCD spectra of nucleosides.

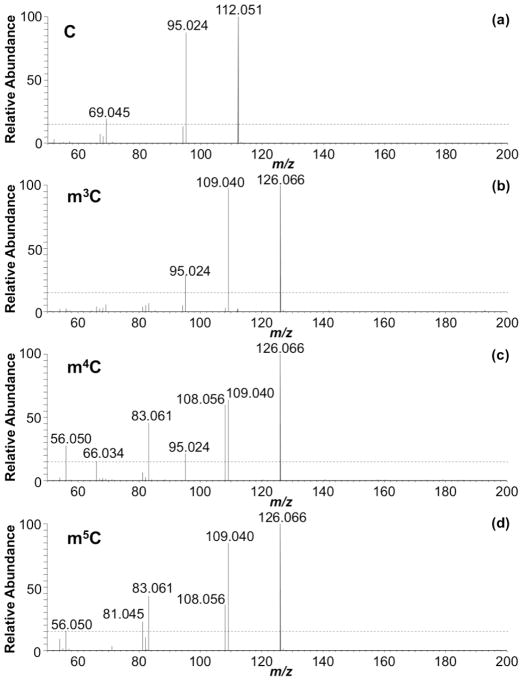

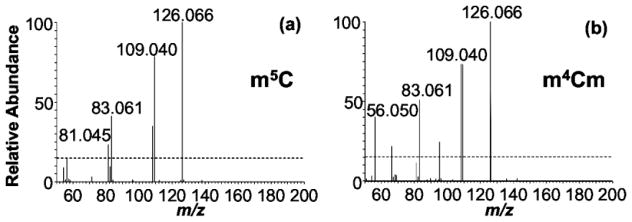

We next examined the HCD MS/MS data to determine whether product ions are generated that are unique to each isomer. For this purpose, the product ions generated from different positional isomers of methylated cytidine are compared against each other and against the unmodified form (Figure 1). HCD of m3C did not generate any unique product ions at the 15% RIA threshold limit. However, a product ion at m/z 95.0245 is commonly observed for both m3C and m4C, allowing them to be differentiated from m5C. HCD of m4C exhibited a unique product ion at m/z 66.0344, allowing it to be differentiated from m3C. HCD of m5C generated a unique product ion at m/z 81.0453, which distinguishes it from m3C and m4C. Thus, m3C, m4C and m5C can be differentiated from each other by HCD based on the presence/absence of specific low mass product ions (Supplemental Table S1). When combined with the other low mass product ions for each isomer discussed above, it appears that HCD can generate isomer-specific product ion fingerprints that can be used for nucleoside identification.

Figure 1.

Fingerprint MS/MS of (a) cytidine, (b) m3C, (c) m4C and (d) m5C acquired by HCD at CE 80. See supplemental Table S1 for more information on the peaks labeled.

Altering the collisional energy (CE, e.g., 60, 80, 100) during HCD resulted in corresponding alteration of the RIA of observed product ions during MS/MS. However, their abundance is negatively correlated with the abundance of methylated base. In other words, as the energy increases, the abundance of BH2+ ion decreased indicating that the product ions are derived from nucleobase. An illustrative comparison of the HCD MS/MS spectra obtained at different CE (60–100, with increments of 20) for m5C is shown in Supplemental Figure S2. Based, in part, on these studies, a CE of 80 was found to provide the best tradeoff between BH2+ ion abundance and low mass product ions for ribonucleoside identification.

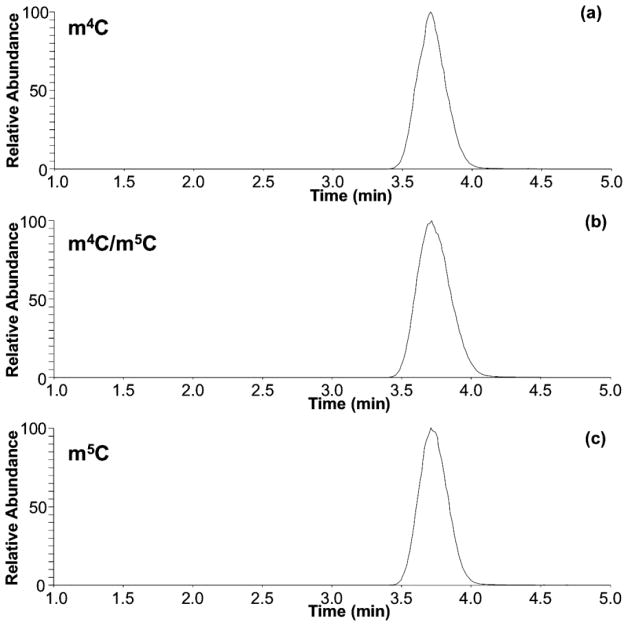

HCD Fingerprinting of Model Nucleoside Isomer Mixtures During LC-MS/MS

With the evidence that HCD-based fingerprints could differentiate the methylated cytidine positional isomers, we next examined the applicability of this approach during LC-MS/MS, when such isomers may co-elute. Under typical ammonium acetate or ammonium formate based mobile phases, m4C and m5C are challenging to resolve chromatographically (Figure 2a). Conventional CID during LC-MS/MS generates product ion spectra that consist of only the molecular and base ions, which cannot be used to differentiate between these two isomers (Figure 2b). However, when HCD was used, the fingerprinting approach could be used to identify the presence (or absence) of these isomers (Figure 2c). The product ion spectra for 100% m4C or m5C matched those described above. When a mixture of both isomers was analyzed, the product ion spectra reflected the proportion of the individual isomer present in the mixture. In fact, there appears to be a quantitative correlation between the RIAs of the product ions present in the HCD spectra and the relative amount of precursor present in the mixture. Future investigations into using product ion RIAs for reporting initial nucleoside abundance are planned.

Figure 2.

Extracted ion chromatograms for m/z 258.1090 acquired for (a) m4C standard, (b) a 1:1 mixture of m4C and m5C, and (c) m5C standard. Similar chromatographic behavior is observed if LC methods 1 or 3 are used. CID MS/MS of (d) m4C standard, (e) 1:1 m4C/m5C mixture, and (f) m5C standard. HCD-based fingerprint of (g) m4C standard, (h) 1:1 m4C/m5C mixture, and (i) m5C standard.

HCD Fingerprinting of Additional Methylated or Other Positional Isomers

To ensure that the HCD fingerprinting approach is generally applicable to modified nucleosides, we examined a few other methylated positional isomers. Methylated adenosines (m1A, m2A, m6A, and m8A – Supplemental Figure S3), methylated guanosines (m1G, m2G, and m7G – Supplemental Figure S4), and methylated uridines (m3U, and m5U – Supplemental Figure S5) were characterized in a manner similar to that described for the methylated cytidines. Table 2 lists the various product ions and RIA for methylated adenosines, guanosines and uridines. Based on these findings, it appears that this HCD approach is broadly applicable to methylated ribonucleosides.

Table 2.

Compilation of peaks m/z and RIAs of ions present in the HCD-based MS/MS spectra of positional isomers of methylated adenosines, guanosines and uridines acquired at CE 80, LC method 1, and 20 ng of nucleoside standard on column. m/z represented are based on theoretical calculations. RIAs are represented as mean (n=3), with RSD <10%.

| m1A | m2A | m6A | m8A | m1G | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak m/z | RIA | Peak m/z | RIA | Peak m/z | RIA | Peak m/z | RIA | Peak m/z | RIA |

| 150.0780 | 100 | 150.0780 | 62 | 150.0780 | 100 | 151.0620 | 51 | 167.0569 | 100 |

| 133.0514 | 20 | 133.0514 | 100 | 123.0671 | 27 | 150.0780 | 100 | 166.0729 | 46 |

| 109.0514 | 20 | 92.0249 | 16 | 94.0405 | 23 | 133.0514 | 92 | 153.0412 | 67 |

| 108.0562 | 17 | 149.0463 | 46 | ||||||

| 106.0405 | 25 | 128.0460 | 22 | ||||||

| 121.0514 | 16 | ||||||||

| 110.0354 | 15 | ||||||||

| 109.0514 | 17 | ||||||||

| 67.0296 | 15 | ||||||||

| m2G | m7G | m3U | m5U | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak m/z | RIA | Peak m/z | RIA | Peak m/z | RIA | Peak m/z | RIA |

| 167.0569 | 100 | 167.0569 | 100 | 127.0508 | 26 | 127.0508 | 47 |

| 149.0463 | 21 | 166.0729 | 38 | 96.0086 | 100 | 110.0242 | 100 |

| 128.0460 | 22 | 149.0463 | 49 | 109.0402 | 32 | ||

| 110.0354 | 22 | 124.0511 | 58 | 84.0449 | 34 | ||

| 57.0453 | 15 | 82.0293 | 27 | ||||

| 57.0340 | 16 | ||||||

| 56.0500 | 22 | ||||||

| 54.0340 | 39 | ||||||

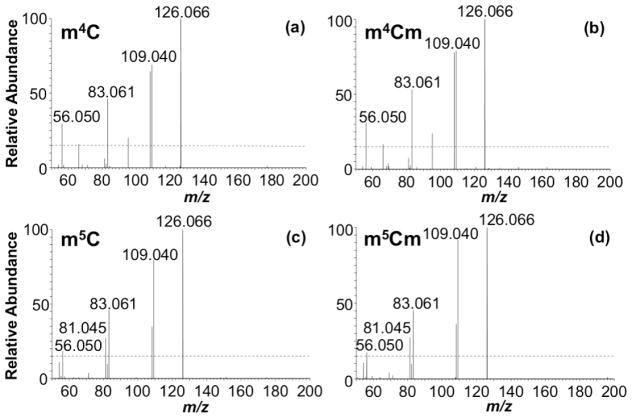

The differentiation of 2′-O-methylated nucleosides from nucleobase methylated nucleosides is easily accomplished during traditional CID-based or low energy HCD-based MS/MS by measuring the fragmentation leading to the nucleobase. For the former, a loss of 146 Da (2′-O-methylated ribose) and detection of canonical base is seen, while in the latter the loss of 132 Da (ribose sugar) will yield the methylated base. However, di-methylated nucleosides (e.g., m4Cm and m5Cm) cannot be differentiated based on CID-type data and would be additional candidates for this HCD-based fingerprinting approach. We tested this possibility by examining the mass spectral fingerprint of m4Cm, and m5Cm using HCD-MS/MS (Figure 3). The fingerprint of m4Cm corresponded with m4C, while that of m5Cm matched well with m5C. This data is consistent with the previous pseudo-MSn behavior of HCD demonstrating that HCD can be used to differentiate nucleobase positional isomers, even when the corresponding ribose group is also modified.

Figure 3.

Fingerprint MS/MS of the nucleoside standards (a) m4C, (b) m4Cm, (c) m5C and (d) m5Cm acquired by HCD and CE 80.

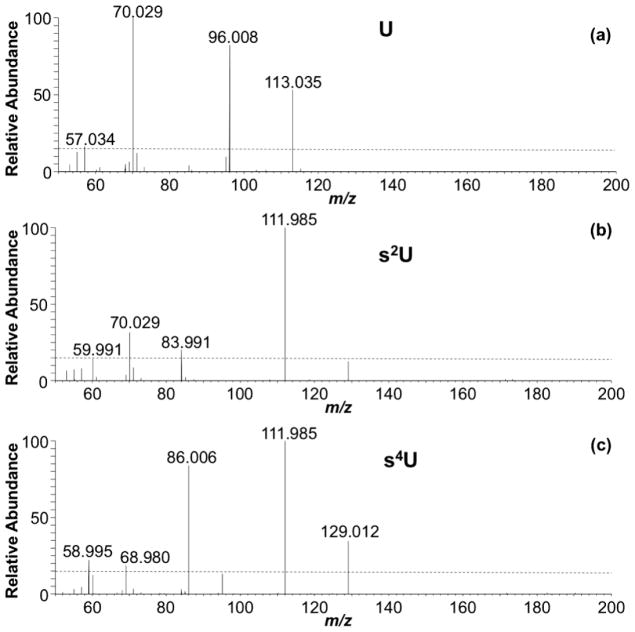

Although the data presented above shows the differentiation of methylated isomers by HCD-based MS/MS fingerprinting, we reasoned that positional isomers of other modifications should also be amenable to this approach. To test this possibility, the mass spectral fingerprints of the positional isomers 2- and 4-thiouridine (s2U, and s4U) were compared (Figure 4). As anticipated, s4U exhibited unique product ions (with RIA ≥ 15%) at m/z 129.0122, 86.0064, 68.9799, and 58.9955, and s2U yielded unique product ions at m/z 83.9908, 70.0293 and 59.9908 (Supplemental Table S1). Thus, even for other types of positional isomers, HCD generates unique product ion fingerprints that can be used to precisely identify the parent isomer present in the sample.

Figure 4.

Fingerprint MS/MS of (a) uridine, (b) s2U and (c) s4U acquired by HCD at CE 80. See supplemental Table S1 for more information on the peaks labeled.

Application of HCD fingerprinting for LC-MS/MS analysis of Positional Isomers in Biological Sample

Using a well-defined set of model modified nucleosides, HCD fingerprinting was found to generate reproducible product ions and RIAs, with no observable retention factor effect. To confirm these findings in a more typical laboratory analysis, we applied this approach for the analysis of modified nucleosides obtained from E. coli total tRNA. The modified nucleosides in this sample have been well characterized previously,[3, 6] thus this sample should provide a good test for the capabilities of HCD-based fingerprinting.

A comparison of the fingerprints acquired for some of the positional isomers detected in this sample is presented in Figure 5. The observed fingerprint product ion pattern of isomers present in E. coli is identical to the specific positional isomer standard’s fingerprint described above. As seen in Figure 5a, the presence of the characteristic peaks at m/z 126.0667 and 109.0402 in the MS/MS spectrum of the precursor with m/z 258.1090 indicated the presence of a methylcytidine modification. Additionally, the absence of peaks at m/z 95.0245 and 66.0344, and the presence of the unique ion at m/z 81.0453 confirmed the identity of the m5C positional isomer. In addition to the characteristic unique ions, the RIAs of non-unique and unique product ions matched well with those specified in Table 1 and the standard m5C shown in Figure 1d. The same can be concluded for other positional isomers detected in E. coli tRNA (Supplemental Figure S6). Thus, the fingerprints acquired from biological samples can be correlated to the fingerprint acquired for specific standards through spectral matching.

Figure 5.

Fingerprint MS/MS of (a) m5C and (b) m4Cm detected in commercial E. coli tRNA.

The fingerprint for m4Cm detected during this analysis is shown in Figure 5b. For this 2′-O-modification, its presence could be confirmed by the occurrence of characteristic ions and RIAs, identical to the respective non-ribose modified methylcytidine (i.e., m4C). Detection of this nucleoside (as well as m5C) in the commercial E. coli tRNA sample was unexpected as neither of these modifications have previously been reported in E. coli tRNAs. These findings suggest that either these modifications are present in tRNA locations not previously reported or, more likely, the sample might be contaminated with (degraded) ribosomal RNA (rRNA), as both modifications have been previously reported in E. coli rRNA[26, 27] and electrophoresis of the commercial tRNA sample did not show any intact rRNA (data not shown). Nevertheless, the data shows that even low abundant modifications can be detected and differentiated by HCD-based fingerprinting during standard bioanalytical characterization of RNA nucleoside digests.

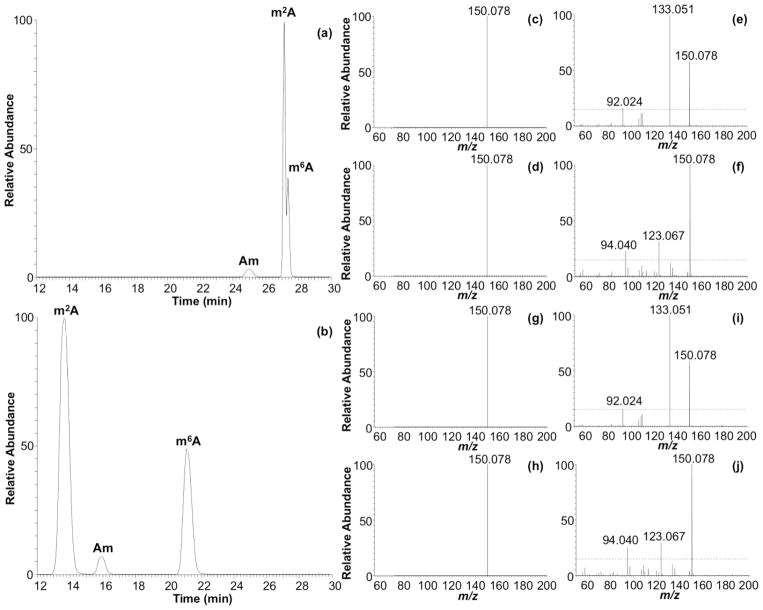

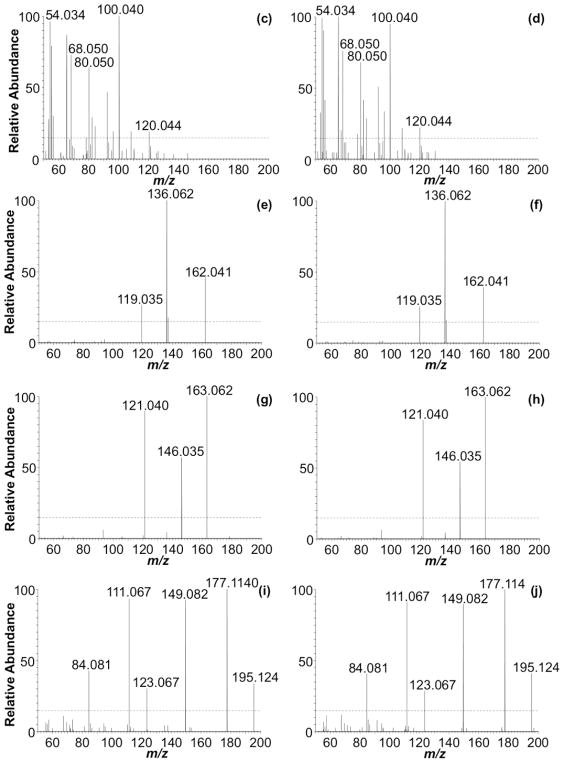

In addition to identifying positional isomers when a standard LC method is ineffective at separating those compounds, another advantage of using HCD fingerprinting is when the LC method is modified (e.g., for method improvement or to enhance MS performance). To illustrate the retention factor insensitivity of HCD fingerprinting, the same E. coli total tRNA nucleoside digest analyzed above was also analyzed using an alternative LC method [9] consisting of 0.1% v v−1 formic acid in water, pH 3.0, as MPA, and acetonitrile/water 40:60, 0.1% v v−1 formic acid, as MPB (LC method 2). The extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) presented in Figure 6 show three of the nucleosides detected at m/z 282.1202 (i.e., Am, m2A, and m6A). Using an ammonium acetate mobile phase, the three peaks, from left to right, correspond to Am, m2A, and m6A, respectively (Figure 6a). However, using formic acid in the mobile phase, the elution order for m2A and Am shifts (Figure 6b). HCD fingerprinting confirms that it is m2A, rather than m6A, which shifts under these mobile phase conditions, and the fingerprint for both positional isomers is essentially identical to those obtained using the ammonium acetate-based mobile phase (Figures 6c–j). Thus, based on these HCD fingerprints, one can readily identify nucleobase isomers without resorting to additional analyses using standards.

Figure 6.

Comparison of extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) and CID MS/MS at CE 40 and HCD MS/MS at CE 80, of Am, m2A, and m6A detected in E. coli under different LC conditions. (a) XIC for m/z 282.1202 employing LC method 3. (b) XIC for m/z 282.1202 employing LC method 2. CID MS/MS spectra of m2A for LC methods 3 and 2 are shown in (c) and (g), respectively. CID MS/MS spectra for m6A for LC methods 3 and 2 are shown in (d) and (h), respectively. HCD MS/MS spectra for m2A for LC methods 3 and 2 are shown in (e) and (i), respectively. HCD MS/MS spectra for m6A for LC methods 3 and 2 are shown in (f) and (j), respectively.

HCD-based Fingerprinting for any Modified Ribonucleoside

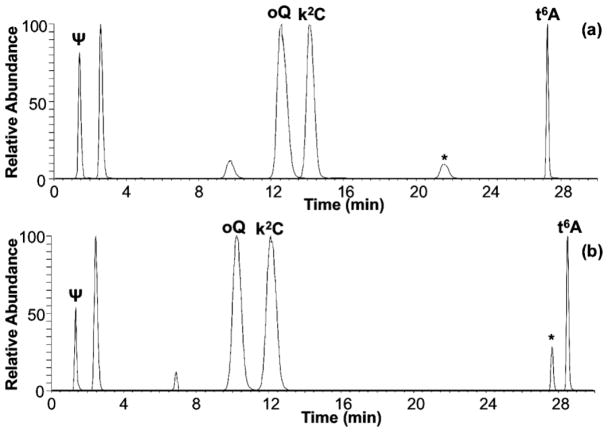

While an important utility of HCD is to use product ion fingerprints to differentiate positional isomers, the more general case holds that any nucleoside presents a characteristic and reproducible fingerprint. For instance, when an E. coli hydrolysate was analyzed by employing either LC method 1 or 2, retention time differences varied differently for each modified nucleoside (Figures 7a–b). Nevertheless, the HCD-based fingerprints of the ribonucleosides were highly reproducible (Figures 7c–j). This observation is illustrated for the RNA modifications pseudouridine (Ψ), epoxyqueousine (oQ), N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A), and 2-lysidine (k2C).

Figure 7.

Comparison of extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) for Ψ, t6A, oQ and k2C detected in E. coli using (a) LC method 1 and (b) LC method 2. * indicates t6A diastereomer. Corresponding HCD fingerprints from each of the different LC methods for Ψ (c) method 1/(d) method 2, t6A (e) method 1/(f) method 2, oQ (g) method 1/(h) method 2 and k2C (i) method 1/(j) method 2.

As employed, HCD-based fingerprints cannot be used to differentiate diastereomers such as D-allo- and L-t6A. The latter is a naturally occurring RNA modification (known simply as t6A) present in tRNA of a variety of organisms (bacteria, fungi, plants and protists).[28] The former has been recently shown by Matuszewski et al.[29] to be present in E. coli tRNA and is linked to the hydrolysis of cyclic t6A (ct6A) under the mild basic conditions employed for RNA hydrolysis. Both diastereomers can be observed in the XICs shown in Figures 7a–b, in which D-allo-t6A (indicated by *) is an earlier eluter when compared to L-t6A. This new approach, however, could be used to provide additional validation or strong support for diastereomers when nucleosides have different elution times but share all mass spectral features, including the HCD fingerprint, in common.

Conclusions

We have found that HCD-based dissociation of modified ribonucleosides during standard LC-MS/MS analysis generates nucleoside-specific product ion fingerprints. These fingerprints can be used in a standard constant-neutral loss mode technique for nucleoside identification. Importantly, positional isomers of modified nucleosides are readily differentiated based on these fingerprints. Moreover, even in those cases where positional isomers co-elute, individual fingerprints can be deconvoluted from the mixture data to identify which isomers are present. These fingerprints are insensitive to chromatographic conditions, precursor ion abundance and sample matrix.

This HCD-based fingerprinting approach enables the detection and confirmation of RNA modifications based exclusively on their mass spectrometric behavior, which allows the possibility of developing an automated protocol for the detection of RNA modifications though spectral matching. Automated nucleoside detection would be possible via the compilation of a spectral library of HCD fingerprints acquired for nucleoside standards and/or nucleosides detected in different organisms, which would then facilitate matching against analytes detected in biological samples. Additionally, this work reveals that the pseudo-MSn nature of HCD generates a rich collection of purine and pyrimidine ring product ions, which should prove useful in situations where a modified nucleoside is not previously characterized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support of this work was provided by the NSF (CHE1507357), DTRA (HDTRA1-15-1-0033), NIH (GM061115 to P.A.B. and OD018485 to P.A.L.) and an NIH T32 Training Grant (GM113770) supporting Cody M. Palumbo. The generous support of the Rieveschl Eminent Scholar Endowment and the University of Cincinnati for these studies is also appreciated.

References

- 1.Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, Piątkowski P, Bagiński B, Wirecki TK, de Crécy-Lagard V, Ross R, Limbach PA, Kotter A, Helm M, Bujnicki JM. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;46:D303–D307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyauchi K, Kimura S, Suzuki T. A cyclic form of N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine as a widely distributed tRNA hypermodification. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;9:105–111. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellner S, Neumann J, Rosenkranz D, Lebedeva S, Ketting RF, Zischler H, Schneider D, Helm M. Profiling of RNA modifications by multiplexed stable isotope labelling. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3516–3518. doi: 10.1039/c3cc49114e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang B-i, Miyauchi K, Matuszewski M, D’Almeida GS, Rubio Mary Anne T, Alfonzo JD, Inoue K, Sakaguchi Y, Suzuki T, Sochacka E, Suzuki T. Identification of 2-methylthio cyclic N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (ms2ct6A) as a novel RNA modification at position 37 of tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:2124–2136. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zallot R, Ross R, Chen WH, Bruner SD, Limbach PA, de Crécy-Lagard V. Identification of a Novel Epoxyqueuosine Reductase Family by Comparative Genomics. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:844–851. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b01100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell SP, Limbach PA. Evaluating the reproducibility of quantifying modified nucleosides from ribonucleic acids by LC–UV–MS. J Chromatogr B. 2013;923–924:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su D, Chan CTY, Gu C, Lim KS, Chionh YH, McBee ME, Russell BS, Babu IR, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. Quantitative analysis of ribonucleoside modifications in tRNA by HPLC-coupled mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:828–841. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thüring K, Schmid K, Keller P, Helm M. Analysis of RNA modifications by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. 2016;107:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basanta-Sanchez M, Temple S, Ansari SA, D’Amico A, Agris Paul F. Attomole quantification and global profile of RNA modifications: Epitranscriptome of human neural stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e26–e26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiss M, Reichle VF, Kellner S. Observing the fate of tRNA and its modifications by nucleic acid isotope labeling mass spectrometry: NAIL-MS. RNA Biol. 2017;14:1260–1268. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1325063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pomerantz SC, McCloskey JA. Analysis of RNA hydrolyzates by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 1990;193:796–824. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)93452-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan CTY, Pang YLJ, Deng W, Babu IR, Dyavaiah M, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins. Nature Commun. 2012;3:937. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai WM, Chionh YH, Hia F, Gu C, Kellner S, McBee ME, Ng CS, Pang YLJ, Prestwich EG, Lim KS, Ramesh Babu I, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. A Platform for Discovery and Quantification of Modified Ribonucleosides in RNA: Application to Stress-Induced Reprogramming of tRNA Modifications. Methods Enzymol. 2015;560:29–71. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakaguchi Y, Miyauchi K, Kang B-i, Suzuki T. Nucleoside Analysis by Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2015;560:19–28. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Squires JE, Preiss T. Function and detection of 5-methylcytosine in eukaryotic RNA. Epigenomics. 2010;2:709–715. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen SS, Ariza X, Nielsen P, Vilarrasa J, Kirpekar F. Collision-induced dissociation of cytidine and its derivatives. J Mass Spectrom. 2007;42:49–57. doi: 10.1002/jms.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose RE, Quinn R, Sayre JL, Fabris D. Profiling ribonucleotide modifications at full-transcriptome level: a step toward MS-based epitranscriptomics. RNA. 2015;21:1361–1374. doi: 10.1261/rna.049429.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen JV, Macek B, Lange O, Makarov A, Horning S, Mann M. Higher-energy C-trap dissociation for peptide modification analysis. Nat Meth. 2007;4:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senko MW, Remes PM, Canterbury JD, Mathur R, Song Q, Eliuk SM, Mullen C, Earley L, Hardman M, Blethrow JD, Bui H, Specht A, Lange O, Denisov E, Makarov A, Horning S, Zabrouskov V. Novel Parallelized Quadrupole/Linear Ion Trap/Orbitrap Tribrid Mass Spectrometer Improving Proteome Coverage and Peptide Identification Rates. Anal Chem. 2013;85:11710–11714. doi: 10.1021/ac403115c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Graaf EL, Altelaar AFM, van Breukelen B, Mohammed S, Heck AJR. Improving SRM Assay Development: A Global Comparison between Triple Quadrupole, Ion Trap, and Higher Energy CID Peptide Fragmentation Spectra. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4334–4341. doi: 10.1021/pr200156b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelhameed AS, Kadi AA, Abdel-Aziz HA, Angawi RF, Attwa MW, Al-Rashood KA. Multistage Fragmentation of Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry System and Pseudo-MS3 of Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry Characterize Certain (E)-3-(Dimethylamino)-1-arylprop-2-en-1-ones: A Comparative Study. Sci World J. 2014;2014:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2014/702819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCloskey JA, Graham DE, Zhou S, Crain PF, Ibba M, Konisky J, Söll D, Olsen GJ. Post-transcriptional modification in archaeal tRNAs: identities and phylogenetic relations of nucleotides from mesophilic and hyperthermophilic Methanococcales. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4699–4706. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu L, Liu X, Sheng N, Oo KS, Liang J, Chionh YH, Xu J, Ye F, Gao YG, Dedon PC, Fu XY. Three distinct 3-methylcytidine (m3C) methyltransferases modify tRNA and mRNA in mice and humans. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:14695–14703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.798298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asano K, Suzuki T, Saito A, Wei FY, Ikeuchi Y, Numata T, Tanaka R, Yamane Y, Yamamoto T, Goto T, Kishita Y, Murayama K, Ohtake A, Okazaki Y, Tomizawa K, Sakaguchi Y, Suzuki T. Metabolic and chemical regulation of tRNA modification associated with taurine deficiency and human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:1565–1583. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross R, Cao X, Yu N, Limbach PA. Sequence mapping of transfer RNA chemical modifications by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. 2016;107:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura S, Suzuki T. Fine-tuning of the ribosomal decoding center by conserved methyl-modifications in the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1341–1352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen NM, Douthwaite S. YebU is a m5C Methyltransferase Specific for 16 S rRNA Nucleotide 1407. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:777–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yacoubi BE, Bailly M, Crécy-Lagard Vd. Biosynthesis and Function of Posttranscriptional Modifications of Transfer RNAs. Ann Rev Genet. 2012;46:69–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matuszewski M, Wojciechowski J, Miyauchi K, Gdaniec Z, Wolf WM, Suzuki T, Sochacka E. A hydantoin isoform of cyclic N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (ct6A) is present in tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:2137–2149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.