Abstract

Background

Bronchopulmonary manifestations of Crohn disease have been rarely described in children, including both subclinical pulmonary involvement and severe lung disease.

Case presentation

A 6.5-year-old girl is described with early recurrent bronchopulmonary symptoms both at presentation and in the quiescent phase of Crohn disease. Pulmonary function tests (lung volumes and flows, bronchial reactivity and carbon monoxide diffusing capacity) were normal. Bronchoalveolar cytology showed increased (30%) lymphocyte counts and bronchial biopsy revealed thickening of basal membrane and active chronic inflammation.

Conclusions

Clinical and histological findings in our young patient suggest involvement of both distal and central airways in an early phase of lung disease. The pathogenesis of Crohn disease-associated lung disorders is discussed with reference to the available literature. A low threshold for pulmonary evaluation seems to be advisable in all children with CD.

Background

Bronchopulmonary manifestations of Crohn disease (CD) in children have been rarely described up to now. As it was already observed in adults [1-3], latent pulmonary involvement is likely to occur also in children with CD [4,5] but few cases of severe lung disease have been reported in the pediatric age [6-10]. We describe a girl who presented early recurrent bronchopulmonary symptoms both at presentation and in the quiescent phase of CD.

Case presentation

A 6.5-year-old Caucasian girl, was admitted reporting a 6-month history of recurrent, bilateral hip arthralgia and recent appearance of abdominal pain and non-bloody diarrhoea, fever and weight loss. Lung examination suggested left lower lobe bronchopneumonia that was confirmed by chest x-ray. Weight and height were 24 kg (+1 SD) and 123 cm (+1 SD) respectively. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 43 mm/h, C-reactive protein (CRP) 190 mg/L and haemoglobin concentration 83 g/L. Mantoux testing (1/1000) was negative and serum immunoglobulins and angiotensin converting enzyme activity were in the normal range. She was HLA-B27 positive. Sonographic examination of hips and knees showed bilateral, clear joint effusion. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was normal and duodenal mucosa biopsies showed signs of active chronic inflammation. At colonoscopy, descending and sigmoid colon and rectum had inflamed and easily bleeding mucosa. lleum and ascending colon were normal. Mucosal biopsy specimens showed extended chronic inflammation with non-caseating epithelioid granulomas in distal colon consistent with the diagnosis of Crohn colitis. The initial treatment consisted of semielemental diet, 1 mg/kg oral prednisone daily, 1 g sulphasalazine daily, oral metronidazole and intravenous ampicillin. Clinical remission of both CD and arthritis was rapidly obtained and pulmonary symptoms and radiological abnormalities resolved. Prednisone was discontinued after three months and sulphasalazine was switched to 1.2 g mesalazine daily after two months. No relapse of CD has been observed since then.

Five months after diagnosis of CD, she had cough and low grade fever and a chest radiograph showed parenchymal density in the middle lobe. Chest auscultation was negative, ESR and CRP were normal, leukocyte count was 5600 cells/mm3. Three weeks later, at a control chest x-ray, middle lobe was normal while a parenchymal density in the upper right lobe appeared (Figure 1). Lung examination was normal and again serologic markers of inflammation were negative. Serum antibodies for Legionella pneumophila, Chlamidia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and respiratory viruses were negative and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis were ruled out. Sweat test was normal. Routine pulmonary function tests were within the normal range (FVC 109%, FEV1 102%, FEF 25–75 118% of predicted values). At bronchoscopy no endoluminal alterations were observed, cytology of bronchoalveolar aspirate had increased lymphocyte counts with 70% macrophages and 30% lymphocytes. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the aspirate and stains and culture for mycobacteria and moulds were negative. Lymphocyte typing in blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was unremarkable (Table 1). Multiple bronchial biopsies showed evident thickening of basal membrane, angiectasies and active chronic inflammation of the tonaca propria (Figure 2). Antimicrobial therapy was discontinued after ten days and radiological abnormalities completely resolved. Colonoscopy with multiple biopsies confirmed the remission of Crohn colitis (Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index = 5).

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph. Parenchymal density in the right upper lobe.

Table 1.

Lymphocyte typing in blood and in bronchoalveolar lavage.

| Lymphocyte typing | Blood | Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| CD3+ (%) | 72 | 94 |

| CD4+ (%) | 45 | 49 |

| CD8+ (%) | 21 | 23 |

| CD4+/CD8+ (ratio) | 2.1 | 2.1 |

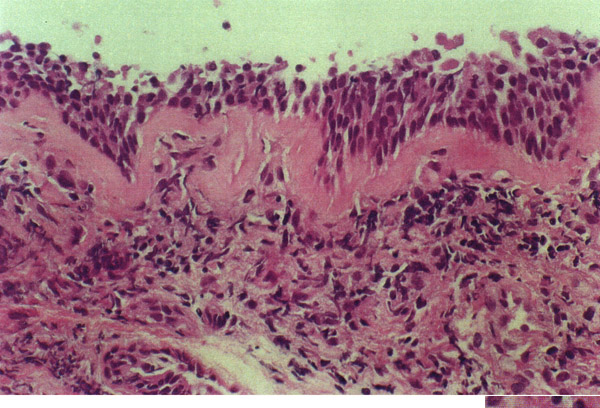

Figure 2.

Bronchial biopsy. Photomicrograph (× 400) of bronchial mucosa showing remarkable basement membrane thickening (asterisks) and mild-moderate submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate (i). The epithelium is normal.

Pulmonary function evaluation, performed when the girl was asymptomatic, was unremarkable. Lung volumes were measured in a constant-volume whole-body plethysmograph, showing normal total lung capacity (98% of the predicted value), functional residual capacity (101% predicted) and residual volume (76% predicted). Spirometry was measured by means of a 12-L bell spirometer (Collins) revealing a normal shaped flow-volume curve, as well as normal forced expiratory volume in 1 sec. (FEV1, 115% predicted), forced vital capacity (FVC, 112% predicted) and FEV1/FVC (89% predicted). No change was observed after the inhalation of salbutamol 200 mcg. Bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR) was tested and ruled out by a methacholine provocation test. The diffusing capacity was also normal with a transfer factor for carbon monoxide (TLCO) of 103% predicted.

A further episode of radiological lung density in the left lower lobe occurred two months later (Figure 3). The patient was treated with oral amoxicillin and prednisone for eight days with prompt clinical and radiological response.

Figure 3.

Chest radiograph. Lung density in the left lower lobe.

Discussion

CD should be regarded as a multisystem disorder that involves mainly the gastrointestinal tract. Although the overall prevalence of concomitant bronchopulmonary manifestations has been evaluated as low as 0.4% [11], subclinical involvement in at least half of adults with CD has been demonstrated by some authors [1,3,12,13] suggesting underlying bronchial inflammation. In children with CD, pulmonary abnormalities have been anecdotally reported, including non-caseating epithelioid granulomas [6,7,9,10], bronchiolitis obliterans [6], desquamative interstitial pneumonitis [14] and bronchopulmonary suppuration [1], as well as respiratory function abnormalities in asymptomatic children [4,5].

The clinical features of bronchopulmonary involvement in our patient seem to be interesting for several reasons. The first is that respiratory symptoms appeared in a young girl concurrently with the early manifestations of intestinal disease. Lung abnormalities were not directly related to the degree of activity of intestinal disease, as suggested by the second colonoscopy that confirmed histological remission of CD. If we make the hypothesis that in CD a common antigenic stimulus may activate the local immune system both in the gut and the lung [7], we might argue that the reactivity of each organ is likely to develop in a partially independent way. Early involvement of the lung in children with CD was also observed by Munck et al. [5] who showed in patients at diagnosis a significant impairment of TLCO suggesting an interstitial pulmonary process.

The results of bronchoalveolar cytology and of bronchial biopsy are consistent with involvement of both distal and central airways. The increased percentage of lymphocytes observed in BAL indicates a lymphocyte alveolitis resembling that already observed in adults with CD or other granulomatous diseases [1] and in the child described by Minic et al. [9]. Thickening of bronchial basal membrane in the absence of granulomatous lesions is an unusual finding in children with CD-associated lung disease. Similar histopathological findings, due to increased subepithelial collagen deposition beneath the basal membrane, have been reported in other chronic respiratory disorders with a strong inflammatory component, such as asthma, chronic bronchitis and tuberculosis [15]. Unfortunately, biopsy specimens were very scarce and we cannot exclude that the evidence of granulomas may have been missed.

Lung abnormalities observed in our patient were unrelated to pharmacological treatment. Respiratory involvement was concurrent with the diagnosis of CD and recurred after three months from sulphasalazine withdrawal. Neither peripheral eosinophilia nor eosinophilia in the BAL – typical signs of mesalamine-induced lung disease [16] – were observed and mesalamine had not to be withdrawn.

Respiratory function tests were normal. In particular, there was no evidence of BHR or reduced carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. BHR was recently observed in 71% of 14 children with CD [4] and in 45% of 38 adults with CD or ulcerative colitis [3] and did not seem to be influenced neither by activity nor by treatment or duration of CD. The pathogenesis of BHR in CD is still unknown but it may be a consequence of subclinical bronchial inflammation, induced by the bronchial homing of lymphocytes activated in the intestinal mucosa. Impairment of TLCO, suggesting an interstitial pulmonary process, has been reported in 19/20 children during active CD and in 5/10 during remission [5]. The apparent discrepancy, between histological and cytological abnormalities and the absence of functional anomalies in our patient, may be due to the still unexplained variability of these phenomena in CD, or to the early phase of lung disease in which studies were performed.

There is increasing evidence that CD-associated respiratory disease represents a problem also in the pediatric age. Although it is not yet clear if these patients represent a subset of CD population and if they need a different therapeutic approach, a low threshold for pulmonary evaluation is advisable in all children with CD.

Competing interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Enrico Valletta, Email: hwwval@tin.it.

Marina Bertini, Email: bertinimarina@hotmail.com.

Luciano Sette, Email: lucseven@infinito.it.

Cesare Braggion, Email: cbraggion@qubisoft.it.

Ugo Pradal, Email: cfc@linus.univr.it.

Marina Zannoni, Email: marina.zannoni@mail.azosp.vr.it.

References

- Bonniere P, Wallaert B, Cortot A, Marchandise X, Riou Y, Tonnel AB, Colombel JF, Voisin C, Paris JC. Latent pulmonary involvement in Crohn's disease: biological, functional, bronchoalveolar lavage and scintigraphic studies. Gut. 1986;27:919–925. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.8.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eade OE, Smith CL, Alexander JR, Whorwell PJ. Pulmonary function in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;3:154–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E, Louis R, Drion V, Bonnet V, Lamproye A, Radermecker M, Belaiche J. Increased frequency of bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Allergy. 1995;50:729–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1995.tb01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansi A, Cucchiara S, Greco L, Sarnelli P, Pisanti C, Franco MT, Santamaria F. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in children and adolescents with Crohn's disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1051–1054. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9906013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck A, Murciano D, Pariente R, Cezard JP, Navarro J. Latent pulmonary function abnormalities in children with Crohn's disease. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:377–380. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentur L, Lachter J, Koren I, Ben-lzhak O, Lavy A, Bentur Y, Rosenthal E. Severe pulmonary disease in association with Crohn's disease in a 13-year-old girl. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29:151–154. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(200002)29:2<151::AID-PPUL10>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder CJ, Lacy D, Raafat F, Weller PH, Booth IW. Crohn's disease with pulmonary involvement in a 3 year old boy. Gut. 1993;34:1636–1638. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.11.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrion F, Bretagne MC, Neimann L, Flechon PE, Canton Ph, Hoeffel JC. Association exceptionelle de lésions pulmonaires, cutanée et d'une iléite terminale chez un enfant de 11 ans. J Radiol. 1982;63:123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minic P, Perisic VN, Minic A. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the lung. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:338–341. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntis JWL, Tarlow MJ, Raafat F, Booth IW. Crohn's disease of the lung. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:1270–1271. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.11.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers BH, dark LM, Kirsner YB. The epidemiologic and demographic characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease: an analysis of a computerized file of 1,400 patients. J Crohn Dis. 1971;24:743–753. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(71)90087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fireman Z, Osipov A, Kivity S, Kopelman Y, Sternberg A, Lazarov E, Fireman E. The use of induced sputum in the assessment of pulmonary involvement in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:730–734. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9270(99)00902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzela L, Vavrecka A, Prikazska M, et al. Pulmonary complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Hepatogastroenterol. 1999;46:1714–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague WG, Sutphen JL, Fechner RE. Desquamative interstitial pneumonitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease of childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4:663–667. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198508000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukanovic R, Roche WR, Wilson JW, Beasley CRW, Twentyman OT, Howarth PH, Holgate ST. Mucosal inflammation in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:434–457. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitton A, Peppercorn MA, Hanrahan JP, Upton MP. Mesalamine-induced lung toxicity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1039–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]