Abstract

Growth and patterning are coordinated during development to define organ size and shape. The growth, proliferation and differentiation of Drosophila wings are regulated by several conserved signaling pathways. Here, we show that the Salvador-Warts-Hippo (SWH) and Notch pathways converge on an enhancer in the expanded (ex) gene, which also responds to levels of the bHLH transcription factor Daughterless (Da). Separate cis-regulatory elements respond to Salvador-Warts-Hippo (SWH) and Notch pathways, to bHLH proteins, and to unidentified factors that repress ex transcription in the wing pouch and in the proneural region at the anterior wing margin. Senseless, a zinc-finger transcription factor acting in proneural regions, had a negative impact on ex transcription in the proneural region, but the transcriptional repressor Hairy had no effect. Our study suggests that a complex pattern of ex transcription results from integration of a uniform SWH signal with multiple other inputs, rather than from a pattern of SWH signaling.

Introduction

One Drosophila gene that integrates signals from multiple growth pathways is expanded [1–4]. The ex gene encodes a FERM-domain protein that activates the Salvador-Warts-Hippo (SWH) pathway of tumor suppressors by at least two mechanisms. First, Ex directly binds with Yorkie (Yki), the Drosophila homolog of Yap and Taz, sequestering Yki in the cytoplasm [5,6]. Secondly, binding of Ex with another FERM domain-containing protein Schip1 can recruit the Hippo (Hpo) kinase Tao-1 and then phosphorylates Hpo [7]. Phosphorylation of Hpo, and then Warts, leads to the phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention of Yki. Both mechanisms of cytoplasmic Yki retention prevent the expression of growth and survival genes including cyclin E, diap1, and bantam by this transcriptional coactivator [8–15].

The ex gene is itself a transcriptional target of Yki and could behave as a negative feedback regulator of the SWH pathway [1]. Since feedback regulators are often among the most general transcriptional targets of signaling pathways, necessary in multiple contexts, they make good general reporters. Accordingly, the ex-LacZ enhancer trap is frequently used as a reporter of Yki activity. In the third instar wing disc, ex-LacZ is transcribed most highly in the proximal wing hinge primordium region of the wing disc, at lower levels in the wing pouch, and absent from the most proximal, wing margin primordium, suggesting a distal-to-proximal gradient of SWH activity that would allow Yki to promote most growth proximally [3,16] (Fig 1C). This is consistent with some models of wing disc growth, which suggest that proximal growth is predominantly under the control of Yki but that growth in the distal wing depends more on Dpp signaling [17,18], possibly because cells in the proximal wing are stretched in comparison to distal wing cells that are more compressed [19,20].

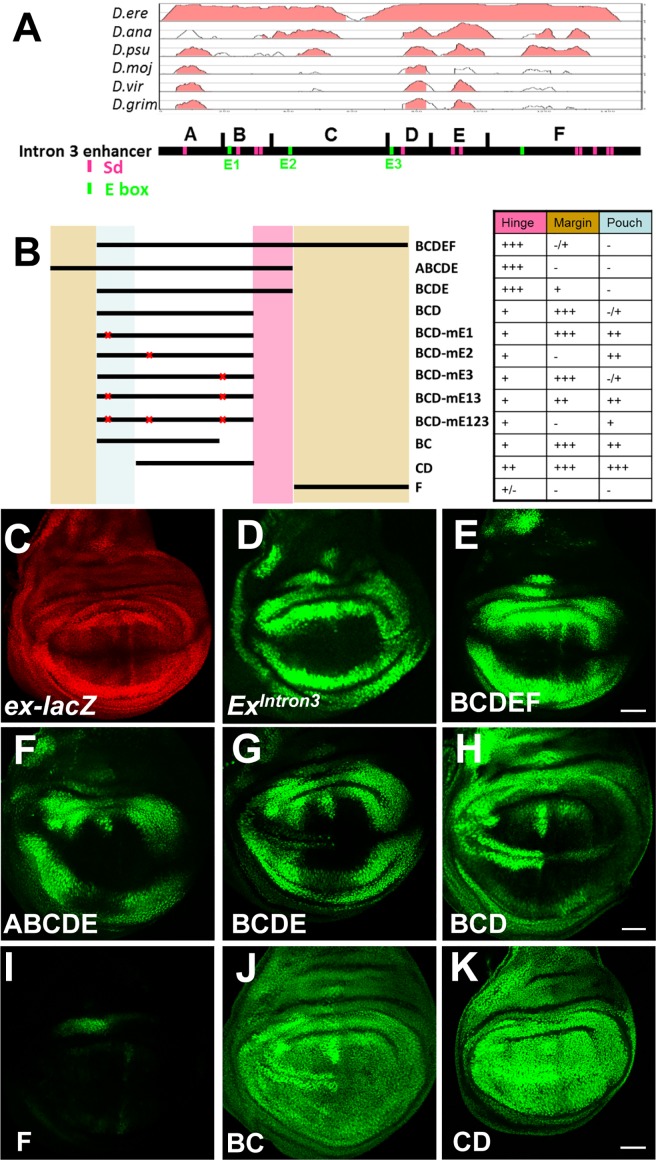

Fig 1. Analysis of the intron-3 enhancer.

(A) Evolutionary conservation of the intron-3 enhancer. VISTA plot [41, 42] of the D. melanogaster intron-3 enhancer (ExIntron3) aligned with sequence from D. erecta, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. mojavensis, D. virilis and D. grimshawl. A window size of 100 bp is used, and regions that are greater than 70% identical are indicated in pink. Regions A-F are defined on the basis of the distribution of sequence conservation among Drosophila. ABCDEF is 1501 bp. A is 1–183; B is 184–345; C is 346–723; D is 724–842; E is 843–1010; F is 1011–1501. Putative E-box and Scalloped (Sd) binding sites are indicated. (B) Deletional or mutational constructs are generated as indicated. Spatial wing expression of each construct is summarized in the table. +++: strong expression; ++: middle expression; +: weak expression; +/-: much weaker or partial expression; -: no expression. Region directing expression in the hinge of wing disc is indicated in pink; regions directing expression in the neuronal precursors of wing disc are pointed in brown; region driving expression in the wing pouch is indicated in blue. (C-K) Wing expression patterns of ex-LacZ and the indicated genomic sub-fragments of ExIntron3. Note the fragments BCDE, BCD, BC and CD drive GFP expression in neuronal precursors. Scale bars, 50 μm.

One factor potentially contributing to the gradient of Yki activity is Notch signaling, which is active at the wing margin [21]. Yki-dependent wing growth depends on Sd, Yki’s DNA-binding protein partner [16,22,23]. Notch induces expression of Vestigial, another Sd-binding protein that is proposed to compete with Yki for Sd and so limit Yki-induced growth in the distal wing pouch [3].

Besides Sd/Yki, under certain circumstances ex is transcriptionally regulated by the bHLH protein Daughterless (Da). In most cells, Da expression is held in check by its inhibitory heterodimer partner Emc, but if Emc is mutated Da expression upregulates and activates ex transcription, reducing growth and survival of emc mutant cells by activating the SWH pathway [4]. Unlike most cells, proneural regions, which are growth-arrested domains within which neural fate determination occurs, express Emc at low levels, which allows Da levels to rise and heterodimerize with the proneural bHLH proteins that drive neural fate determination and differentiation [24]. Unlike emc mutant cells, however, proneural cells do not seem to activate ex transcription, despite lower Emc and higher Da levels. For example the anterior wing margin contains a proneural region that gives rise to the innervated sensory bristles of the anterior wing margin of the adult fly [25,26]. The primordium of the anterior wing margin lies in the distal center of the wing disc, where ex-LacZ is lowest, despite elevated Da and reduced Emc levels there [24]. Another proneural region, the morphogenetic furrow of the eye imaginal disc, also exhibits low ex-LacZ levels despite also lacking Emc protein and expressing elevated Da [1,24].

Through our analysis of ex regulation by Da, we identified an enhancer within intron 3 that replicates most features of ex transcription [4]. The enhancer drives reporter gene activity similar to that of ex-LacZ in most tissues (Figs 1 and S1, this study). This enhancer is activated by Da through one or more of 3 E-box sequences, and demonstrably bound by Da in chromatin from wing imaginal discs [4]. The intron 3 enhancer also contains the sequences that respond to Sd/Yki [4], and is associated with Yki protein in vivo according to previously-published ChIP data [27]. Here, we present a further characterization of the ex intron 3 enhancer that provides insights into the regulation of ex expression and SWH activity by growth-regulatory pathways in the wing imaginal disc.

Materials and methods

Drosophila genetics

Fly culture and cross were performed according to standard procedures at 25°C unless otherwise noted. ex697-LacZ (gift from Claude Desplan; [28]), ExIntron3-GFP (EnhIntron3-GFP; [4]), and scaD120-LacZ [29] were used to monitor transcriptional activity of ex and to define the proneural regions. Mutant clones were generated by FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination by crossing mutant strains with [arm-LacZ] FRT80B (BDSC BL#6341; [30]); [Ubi-GFP] M(3)67C FRT80B [31] and [Ubi-mRFP.nls] FRT40A (BDSC BL#34500). Mutant strains used were h22 FRT80B [32], sensE2 FRT80B (gift from Hugo Bellen; [33]), da3 FRT40A [34]. Heat shocks were performed at 36–48 hr after egg laying (AEL) to induce FLP and animals were dissected at late third instar. For overexpression or knocked-down experiments, the following drivers were used: en-Gal4 UAS-RFP (BDSC BL#30557), nub-Gal4 (BDSC BL#38418) and dpp40C6-Gal4 [35]. UAS-da [4], UAS-da-da [4], UAS-sens (gift from Hugo Bellen; [33]), UAS-h (BDSC BL#36529) transgenes were used to overexpress the corresponding gene products. The Notch, yki and sd were knocked-down using UAS RNAi transgenes, including UAS-N-RNAi (BDSC BL#7078; [36]), UAS-yki-RNAi (BDSC BL#31965), and UAS-sd-RNAi (BDSC BL#29352).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed as described previously [37]. Confocal imaging was performed using Leica SP2 and Zeiss LSM 880 microscopy. Primary antibodies used were anti-Sens (guinea pig, a gift from H. Bellen); beta-galactosidase (mouse, DSHB#40-1a); GFP (rat, NACALAI TESQUE# GF090R). Species-matched Cy2-, Cy3- and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

Enhancer dissection

Subfragments derived from ExIntron3 were obtained by PCR amplification using primers with Bam HI-Xho I or Bgl II-Xho I sites and cloned into the pH-Stinger vector. The putative transcription factor binding sites were predicted using JASPAR database [38] or rVista [39]. Constructs carrying mutated E-box sites or Sd-binding sites were generated by PCR mutagenesis using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). For each construct, a minimum of three independent transgenic lines was analyzed for GFP activity. The expression patterns of each construct were reproducible between different transgenic lines because the pH-Stinger vector contains insulator sequences to eliminate position effects [40].

Results

Deletion analysis of the ExIntron3 enhancer

The ex intron 3 enhancer (ExIntron3; described as EnhIntron3 in our previous paper[4]) was first recognized as a 1.5 kb segment regulating transcription in a pattern similar to the ex-LacZ enhancer trap and which is conserved in other Drosophila species (Fig 1A, 1C and 1D; [4]). In leg, antennal and haltere imaginal discs, ExIntron3–GFP faithfully recapitulated ex-lacZ expression (S1 Fig). However, some differences may exist. Although ExIntron3–GFP and ex-LacZ expression are very similar in the wing imaginal disc, there is less ExIntron3–GFP in the wing pouch than seen for ex-LacZ (Fig 1C and 1D, S1A–S1D Fig). Intriguingly, ExIntron3–GFP expression reduced faster than ex-LacZ in the wing pouch at early third instar stage (S1C and S1D Fig). This could be because ex-LacZ is also influenced by other enhancers elsewhere in the ex gene (or other genes), or it could be that Lac-Z is more stable than GFP so the ex-LacZ pattern is partly reflecting the earlier transcription pattern. In addition, in the eye disc, ex-LacZ is expressed in a gentle anterior-posterior gradient anterior to the morphogenetic furrow, where ExIntron3–GFP is expressed very little (S1E and S1F Fig). Several regions of the enhancer are highly conserved among multiple Drosophila species (Fig 1A).

To dissect the basis for ex transcriptional regulation further, deletion constructs of ExIntron3 were generated and analyzed (Fig 1B). The original 1.5kb region was divided into 6 sections, ABCDEF. Elements A, D, and E in particular showed conservation in the distantly related species D. virilis and D. grimshawi (Fig 1A).

When either element A or F was deleted, the sequences remaining in ABCDE or BCDEF retained the similar expression pattern as full-length ExIntron3 (Fig 1D–1F). Without both elements, however, in the BCDE reporter new transcription appeared in the proneural regions that flank the anterior wing margin (Fig 1G). These are the regions where sensory structures of the anterior wing margin develop [43,44]. This suggests that both elements A and F contain information for blocking ex expression in the wing margin proneural cells, and that either A or F is sufficient for this. However, elements A and F did not share sequence similarity. Element F comprises 1/3 of the entire ExIntron3. Region F alone had weak expression in the distal wing hinge and antenna imaginal discs, while it showed no reporter activity in the eye and leg discs (Fig 1I, S1 Fig). The BCDE element did not show major qualitative expression changes in eye-antennal or leg discs (S1 Fig), indicating that ex is regulated at the wing margin differently from some other proneural regions such as the morphogenetic furrow of the eye disc. Thus, positive aspects of ex enhancer activity appear to map within BCDE sequences.

Little further effect on the pattern of wing disc expression was seen when region E was deleted, but there may be some quantitative differences between BCD-GFP and BCDE-GFP. In BCD-GFP (which was described as Enh658 in our previous paper [4]), GFP seemed somewhat decreased in the distal hinge but higher in the wing margin proneural cells (Fig 1H). Overall, though, sequences within the BCD element were sufficient for much of the ex transcription pattern (except for repression of the wing margin proneural cells that was redundantly encoded by elements A and F).

It was the D sequences that showed the greatest evolutionary conservation (Fig 1A). However, element D alone failed to drive any GFP expression in the wing disc (S1Q Fig). When we tried subdividing element BCD, element BC-GFP showed similar expression as BCD-GFP, except that BC-GFP also drove expression in the wing pouch (Fig 1J). CD-GFP drove even more expression, almost uniformly throughout the wing disc. Although this expression was largely uniform, it seemed the proneural cells of the anterior wing margin continued to maintain slightly higher levels (Fig 1K). Therefore, sequences in region B and D appeared to be necessary to prevent ex transcription in the wing pouch region, excluding the anterior wing margin proneural cells where repression required element A or F

These studies provide an outline for how the pattern of ex transcription defined by ex-LacZ and by ExIntron3–GFP arises, and of the minimum regulatory inputs that are to be expected. The core of the enhancer as illustrated by CD-GFP drives transcription almost uniformly throughout the wing disc, possibly at a somewhat higher level in proneural cells (Fig 1K). Sequences within element B and D both repress ex-transcription in the wing pouch region excluding the proneural cells of the anterior wing margin, whereas sequences A and F redundantly add repression of ex in the proneural cells.

Mutational analysis of transcription factor binding sites in the ExIntron3 enhancer

Because proneural regions are generally defined by bHLH transcription factors, we wondered whether ex transcription near the wing margin depended on the Achaete-Scute Complex (AS-C). Since all the AS-C proteins require dimerization with Da to bind DNA, we examined BCD-GFP expression in da null clones. BCD-GFP expression was reduced in da null mutant clones within the wing margin proneural cells (Fig 2A), consistent with a role for the AS-C in wing margin expression.

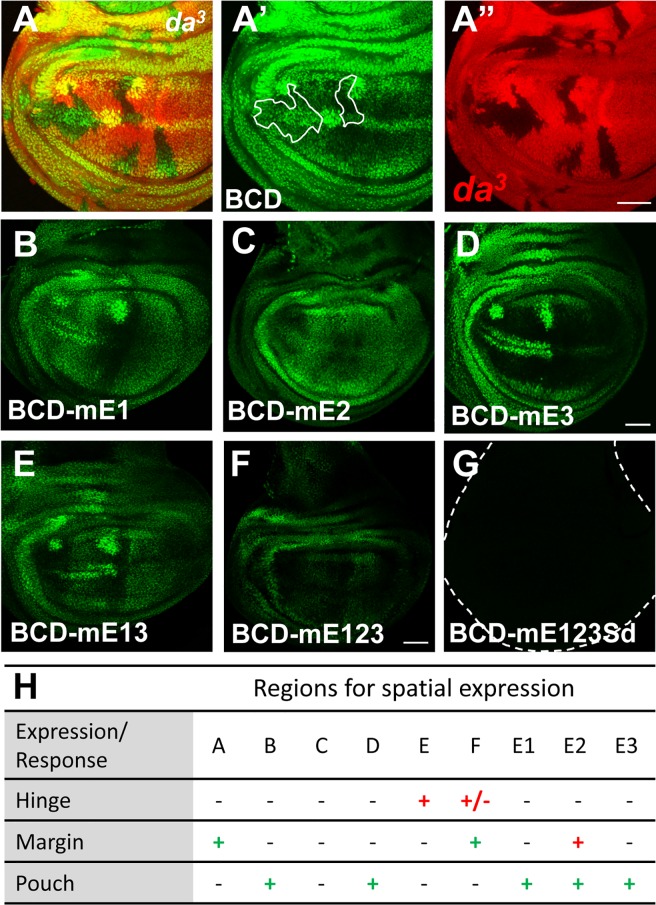

Fig 2. Effect of bHLH protein on ExIntron3 enhancer.

(A) Third instar wing imaginal discs containing da3 mutant cells (RFP [red] negative) are visualized for BCD-GFP reporter expression (A’, green). Note the decreased levels of BCD-GFP in da mutant clones within the wing margin proneural region but not hinge. (B-G) GFP reporter expression driven by the indicated genomic sub-fragments in the third instar wing imaginal discs. (H) Summary of regions important for spatial expression. Note that + (red): sufficiency; +/-: partial sufficiency; + (green): requirement; -: no effect. Scale bars, 50 μm.

AS-C/Da heterodimers bind to DNA through E-box sequences (CANNTG). BCD contains three potential E-box sequences, and these were mutated individually, together, and in combinations (Fig 2, S2A Fig). Mutating all three E-boxes together (in construct BCDmE1,2,3) abolished BCD activity in the anterior wing margin proneural cells (Fig 2F). Whereas E-box 1 and E-box 3 were dispensable, even when mutated together in construct BCDmE1,3 (Fig 2B, 2D and 2E), by contrast E-box 2 was essential for BCD-GFP expression in the wing margin cells (Fig 2C). Because E-box 2 is the only E-box remaining in the BCDmE1,3 construct that drives expression very similar to the parent BCD-GFP element (Fig 2E), it is likely that E-box 2 is also sufficient for ex expression at the anterior wing margin proneural cells (at least within the context of the BCD element).

Interestingly, mutations in any of the E-box sequences also appeared to affect expression outside of the proneural cells. Each of the constructs BCDmE1-GFP, BCDmE2-GFP, BCDmE1,3-GFP and BCDmE1,2,3-GFP led to some expression in the whole of the wing pouch, away from the wing margin (Fig 2B, 2C, 2E and 2F).

Since this enhancer was identified initially as the Daughterless-responsive element of the ex gene, responsible for Da-dependent Ex over-expression when the emc gene was mutated, we also mapped the sequences conferring Da-response, using nub-Gal4 to over-express Da throughout the wing pouch region. We had found previously that the core enhancer BCD retained the induction by Da over-expression, and that E-boxes were required, because no response was seen to Da over-expression in BCDmE1,2,3 (which was called Enh658-mEbox in our previous paper[4]). Here, we report that BCDmE1,3 also failed to respond to Da over-expression (S2C Fig). Thus the response to Da over-expression depended on distinct E-boxes in comparison to ex expression in response to AS-C and Da at the anterior wing margin.

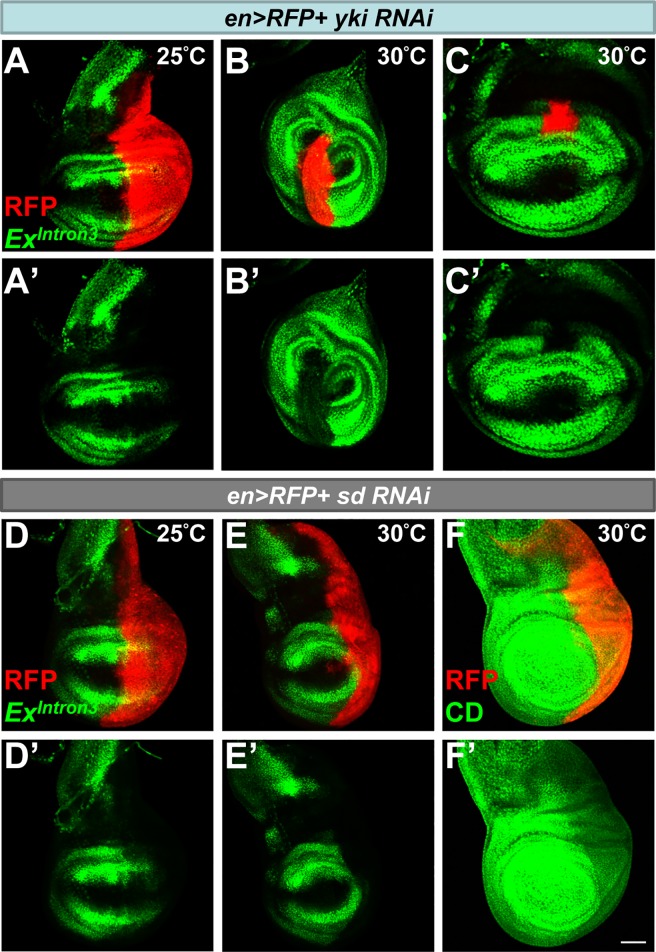

It has been reported that SWH activity is sufficient to activate ExIntron3 expression. Over-expression of Sd and Yki was sufficient to activate expression in the wing pouch [4]. To determine whether SWH pathway was required for the normal activity of ExIntron3, Sd/Yki activity was knocked down by double-stranded RNAs, expressed under the control of en-Gal4. En-Gal4 drives gene expression in the posterior compartment, including the posterior wing hinge region where ExIntron3-GFP is active. GFP expression of ExIntron3 was cell autonomously decreased by knock-down of either Yki or Sd in the wing or leg discs (Fig 3A–3E, S3A and S3B Fig), suggesting that Sd/Yki is necessary for endogenous expression of ex in the proximal part of the wing disc. When Sd and Yki were knocked-down in the background of CD-GFP, which is expressed throughout the wing disc, expression in the wing pouch region was greatly decreased (Fig 3F, S3C–S3F Fig), indicating that Sd and Yki are active throughout the wing disc and needed to activate ex transcription at all locations. Note that the sequences that normally reduce wing pouch expression map to region B of the enhancer, however, as described above.

Fig 3. SWH pathway requires Sd/Yki to regulate ex.

(A) Blockage of the SWH pathway by expressing an RNAi against yki (en>RFP+yki RNAi) leads to the downregulation of ExIntron3-GFP (green) in the posterior compartment (marked by RFP, red) of wing disc at 25°C. (B-C) Leg and wing discs of en>RFP+yki RNAi (red) staining for ExIntron3-GFP (green) at 30°C. Fly cross and culture was performed at 25°C. After 36–48 hr AEL, en>RFP+yki RNAi flies were incubated at 30°C until dissection at late third instar. Note the autonomous reduction of GFP was more obvious in flies that were shifted at 30°C. The altered en domain (marked by RFP, red) at 30°C suggest that Yki may regulate en expression. (D-E) Wing disc of en>RFP+sd RNAi (red) staining for ExIntron3-GFP (green) at 25°C and 30°C, respectively. Note the decrease of GFP was more obvious when animals were shifted and incubated at 30°C. (F) Wing disc of en>RFP+sd RNAi (red) staining for CD-GFP (green) at 30°C. Note that CD-GFP was decreased in a cell autonomous manner. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Twelve putative binding sites of Scalloped (Sd) were predicted across the entire ExIntron3 element (Fig 1A), however, only one of these lies within the CD element. We obtained inconsistent results from mutating this site. When this putative Sd binding sequence (in region D) was disrupted in the CD-GFP construct, expression in the pouch was partially reduced, leading to an expression pattern similar to BC-GFP where the anterior wing margin expression is clearly higher than that of the surrounding wing pouch (S2A and S2E Fig). When this sequence was disrupted in BCDmE123-GFP, expression was completely lost (Fig 2F–2G, S2A, S2D and S2E Fig). Taken together, these studies show that Sd and Yki are required for ExIntron3 expression, and probably at least in part through this Sd site, although it is uncertain whether other sequences could also be involved.

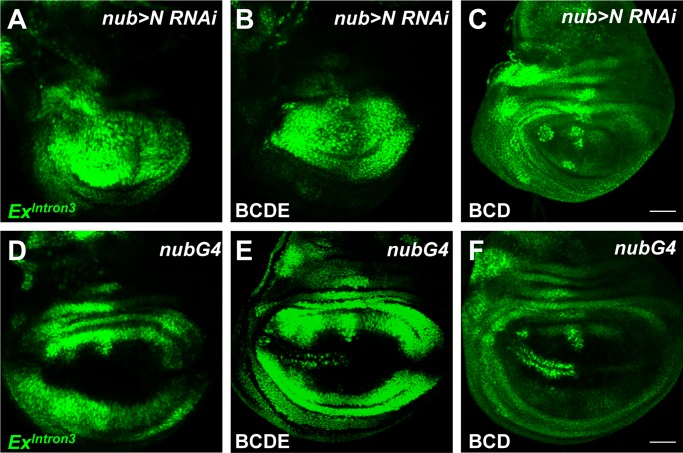

Regulation of the ExIntron3 enhancer by candidate genes

Because the CD element is expressed throughout the wing disc in response to Sd/Yki, and the addition of region B is necessary for repressing ex transcription in the distal wing and pouch, our studies question whether SWH signaling and Sd/yki are responsible for the proximal-distal gradient of ex transcription. It has been proposed that N contributes to proximo-distal patterning of ex transcription, by inducing Vg within the wing pouch [45]. Vg could compete with Yki for Sd and so diminish Sd/Yki activity. Consistent with this model, N knock-down in the wing pouch de-repressed ex transcription [3]. Using N knock-down, we found that N was required for wing pouch repression of the full-length enhancer, and of the BCDE construct, but that the BCD construct remained repressed in the wing pouch even when N was knocked-down (Fig 4). These results suggest that N represses ex transcription in the wing pouch through region E of the enhancer. However, N knockdown abolished expression of ex at the wing margin in BCD-GFP, indicating that N activity contributed to the AS-C/Da-dependent ex expression that occurs there.

Fig 4. Element E is required for Notch-dependent repression.

(A) Blockage of the Notch pathway by expressing an RNAi against Notch in wing pouch (nub>N RNAi) leads to the upregulation of ExIntron3-GFP (green). (B) GFP expression under the control of element BCDE in nub> N RNAi wing discs. Note the de-repression of BCDE-GFP in response to knockdown of Notch. (C) Wing disc of nub>N RNAi staining for BCD-GFP expression. Note that the BCD-GFP did not respond to downregulation of Notch pathway. (D-F) Wing imaginal discs of nub-Gal4 for ExIntron3-GFP (D), BCDE-GFP (E) and BCD-GFP (F), respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm.

The specific identity of pathways repressing of ex transcription in the wing pouch and at the anterior wing margin was explored further using mutations in candidate repressor genes. Senseless (Sens) was a candidate repressor because low levels of Sens have been reported to act as a repressor in vivo [46]. The mammalian homolog of Sens, the growth factor independence 1 (Gfi-1) gene, encodes a zinc finger transcriptional repressor that represses several cell cycle components and proapoptotic Bcl2 family member Bax [47–51]. Sens is expressed in the wing margin cells [33], and a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-chip database of early embryogenesis [52] reported the association of Sens protein with the intron-3 enhancer region of ex. Interestingly, when a linked Da homodimer was overexpressed in the wing pouch, ExIntron3 expression was induced as seen previously when Da monomer was expressed [4], except for sporadic patches of cells that also turned on Sens expression (Fig 5A and 5B). Thus there was a correlation between Sens expression and silencing ExIntron3 expression, as also occurs at the normal anterior wing margin.

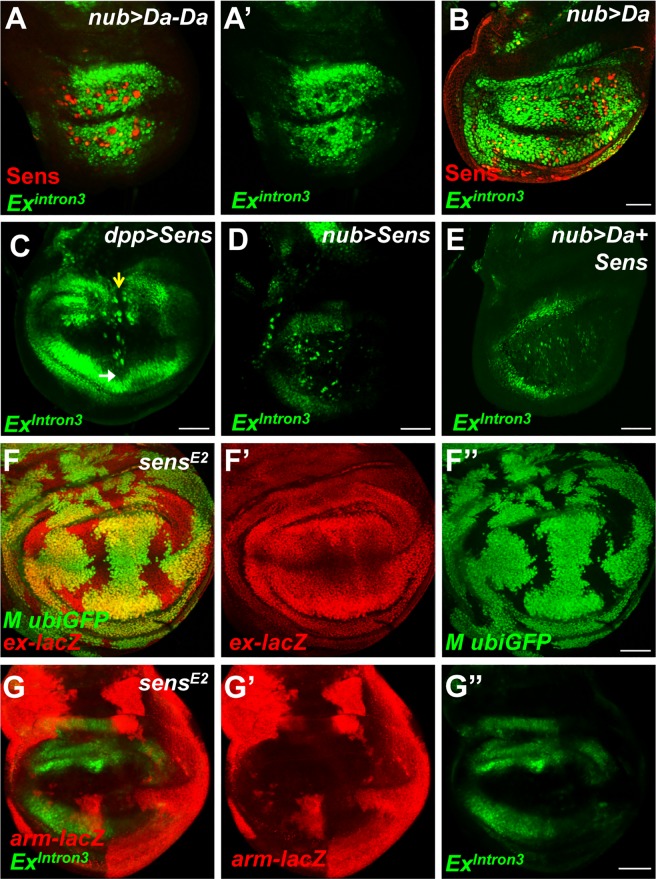

Fig 5. Sens inhibits Da-mediated ex expression in the wing pouch.

(A, B) Wing disc overexpressing Da homodimer (A, nub>Da-Da) or monomer (B, nub>Da) in the wing pouch and staining for ExIntron3-GFP (green) expression. Note the upregulation of ExIntron3-GFP caused by Da homodimer is attenuated in Sens-expressing cells (red). (C) Wing imaginal disc of dpp>Sens staining for ExIntron3-GFP expression. Note the inhibition of ExIntron3-GFP by high levels of Sens in the dorsal proximal wing (indicated by yellow arrow), while ventral wing is barely affected (white arrow). Some enlarged cells with GFP-positive staining are seen around the Dpp domain. (D) Wing disc of nub>Sens staining for ExIntron3-GFP expression. (E) Wing disc of nub>Da+Sens staining for ExIntron3-GFP expression. Note the GFP expression is slightly disrupted as seen in nub>Sens disc. (F-F”) A late third instar wing disc containing sens mutant cells (GFP negative) is visualized for ex-LacZ expression (red, F’). (G-G”) Third instar wing imaginal disc of sens mutant cells (arm-lacZ negative) visualized for ExIntron3-GFP expression (green, G”). Note no elevation of ex-LacZ and ExIntron3-GFP is detected in sens mutant clones. Scale bars, 50 μm.

When Sens was over-expressed using the dpp-GAL4 driver, ExIntron3 expression was reduced where the Dpp expression domain crossed the proximal wing region dorsally, but this was not observed ventrally (Fig 5C). When Sens was over-expressed throughout the wing pouch using nub-Gal4, ExIntron3 expression was slightly reduced (Fig 5D). ExIntron3 expression was unchanged when Da was co-expressed with Sens, clearly demonstrating the capacity of Sens to repress expression (Fig 5E).

To examine ex expression in the absence of Sens, ex-LacZ and ExIntron3 –GFP were examined in sens null mutant clones, but there was little effect; expression remained low in the wing pouch and wing margin (Fig 5F–5G). These results suggest that Sens over-expression may be able to suppress ex expression but is not normally required to do so in the wing pouch or at the anterior wing margin.

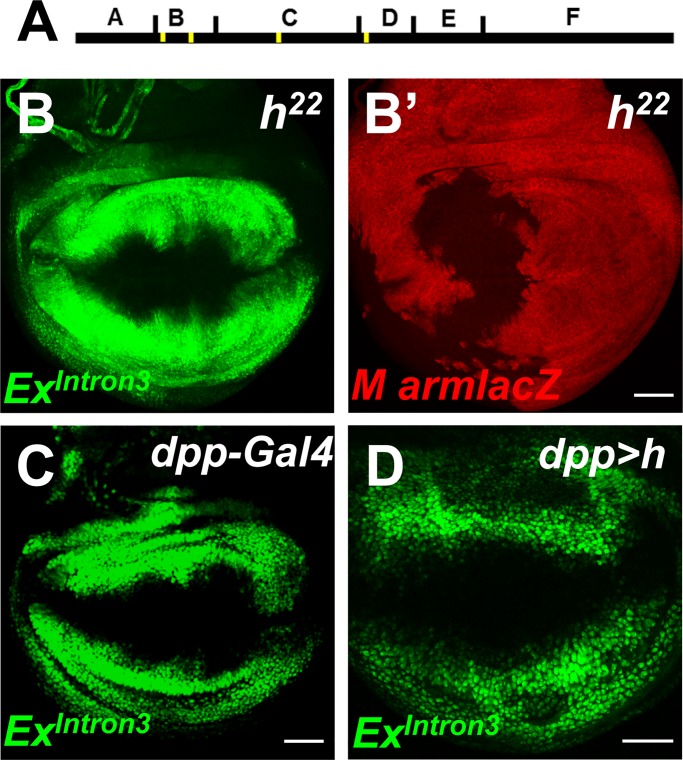

Intriguingly, several putative Hairy binding sites were predicted within intron-3 enhancer (Fig 6A). Proteins of the Hairy/Enhancer of split/Deadpan (HES) family act as a classical transcriptional repressors by binding to C-box (CACNNG) sequence [53–57]. Although Da expression is independent of hairy [58], Hairy antagonizes neurogenesis via binding to the enhancer of another proneural gene achaetae [59]. To investigate ex expression in the absence of hairy (h) activity we used clones homozygous for h null alleles. ExIntron3-GFP was unchanged (Fig 6B). This suggests that h is not required for repressing ex in the wing margin proneural region. Also, overexpression of h was not sufficient to repress ExIntron3-GFP (Fig 6D). Previous studies have shown that ex-lacZ is unaffected in homozygous clones which removes the entire Enhancer of split (E(spl)) complex and deadpan (dpn)[3]. Together, these findings suggest that none of HES repressor proteins can account for the repression of ex in the wing although we cannot completely rule out the possibility that h, E(spl) and dpn might function redundantly.

Fig 6. ex expression is independent of hairy.

(A) Schematic representation of the ABCDEF enhancer. Yellow bars denote putative Hairy binding sites. (B-B’) Clones of homozygous hairy mutant cells are labeled by the lack of LacZ expression (red). Note ExIntron3-GFP (green) is not changed in h clones. (C, D) Expression of ExIntron3-GFP in wing discs of dpp-GAL4 (C) and dpp>h (D) flies. Note ExIntron3-GFP is not affected in Dpp domain when h expression is manipulated. Scale bars, 50 μm.

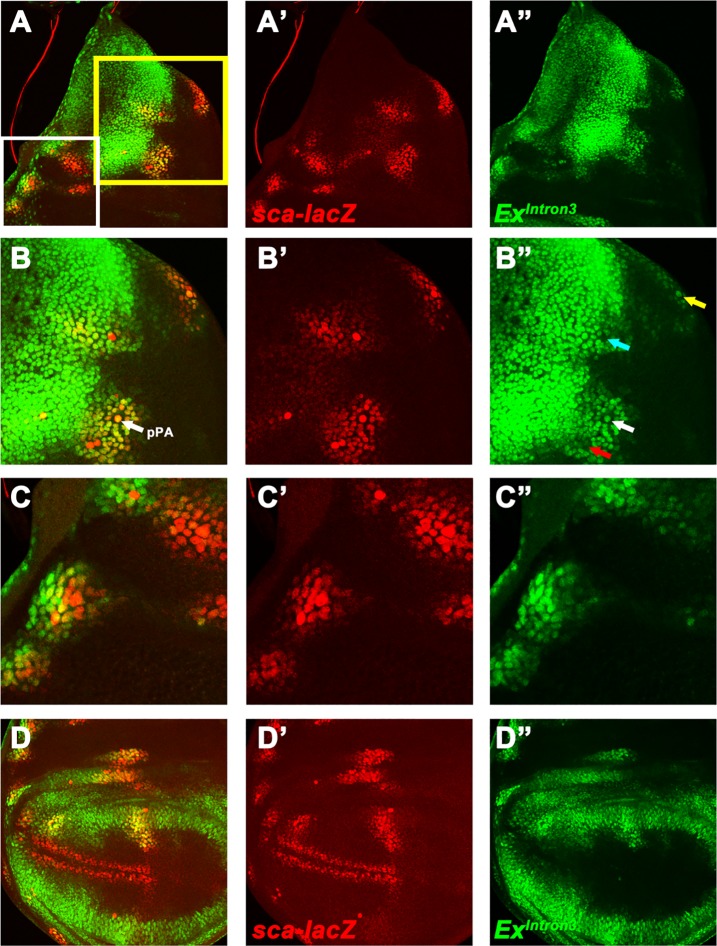

Because Da protein is elevated in all proneural regions yet examined, yet at the anterior wing margin this does not seem to elevate ex transcription, we examined some other proneural regions for comparison. As already mentioned, ExIntron3–GFP is not active in eye imaginal discs. We double labeled ExIntron3 reporter with sca-lacZ to visualize proneural region in the notum and wing (Fig 7). Like the anterior wing margin, ExIntron3 reporter was absent from some SOP cells of notum, such as anterior post-alar SOP. However, ExIntron3 reporter was expressed in many other proneural regions as defined by sca-LacZ expression [29]. For instance, ExIntron3 reporter was expressed more highly in the posterior post-alar SOP than in surrounding cells (Fig 7B). Intriguingly, hypomorphic ex mutants have extra post-alar bristles in the adult thorax [4], suggesting that ex is required for some aspects of proneural cluster development. The variety of expression levels at distinct proneural regions implies spatially-regulated positive and negative inputs acting on ExIntron3.

Fig 7. ex expression in the proneural regions.

Expression patterns of ExIntron3-GFP (green) and sca-LacZ (red) in notum (A-A”) and wing pouch (D-D”). (B-C) Higher magnification of the yellow box (B-B”) and white box (C-C”) in A. Note the anterior scutellar SOP showed higher GFP activity than nearby cells (yellow arrow), the posterior post-alar SOP expressed the GFP at levels similar to other proneural cells (white arrow), whereas the posterior dorsocentral SOP and anterior post-alar SOPs showed reduced levels of GFP activity (blue and red arrows, respectively).

Discussion

The development, differentiation and growth of cells and tissues require precisely regulated patterns of gene expression, depending on the time and spatial location of its activation, and its crosstalk with other signaling pathways. Here we used the Drosophila wing disc as a model system to investigate how ex transcription is regulated. Ex is important as a negative growth regulator that acts through the SWH pathway [1,5–7,60–62]. It restricts wing size in normal development, so that mutants have larger, ‘expanded’ wings [63], and can also be induced to block growth of cells with developmental perturbations, including those with emc mutations that over-express Da [4]. In normal development, ex-LacZ is expressed most highly in the hinge region that surrounds the wing pouch, and expression decreases in a gradient until none is detected at the wing margin (Fig 1C). Unlike expression patterns of ex-LacZ, a relatively ubiquitous distribution of Ex protein is seen in the wing imaginal discs [15, 64–65]. The discrepancy between ex reporter and Ex protein might be due to the post-translational control of Ex protein stability [66]. Alternatively, Ex protein might be strongly influenced by expression patterns in earlier developmental stages (S1A Fig). Regardless, because ex is itself a transcriptional target of the SWH pathway, acting through Sd and Yki, ex-LacZ is extensively used as a transcriptional readout of SWH signaling activity, if not of Ex protein distribution. This transcription pattern of ex could be interpreted to indicate a proximal-to-distal gradient of Sd/Yki activity, which would be consistent with certain models of wing growth regulation that propose that SWH activity represses growth in central regions of the disc whereas Yki activity is higher in proximal regions [67]. Another mechanism predicted to repress growth in central regions of the wing disc is activation of Notch signaling there. Notch signaling induces expression of Vg, a protein that binds Sd in competition with Yki and is therefore predicted to reduce Yki activity (and ex transcription) in central regions of the wing pouch [3]. Since we have identified an ex enhancer whose activity reflects the ex-LacZ reporter in the endogenous gene, we can explore this enhancer to understand how these and other signals are integrated at the ex locus.

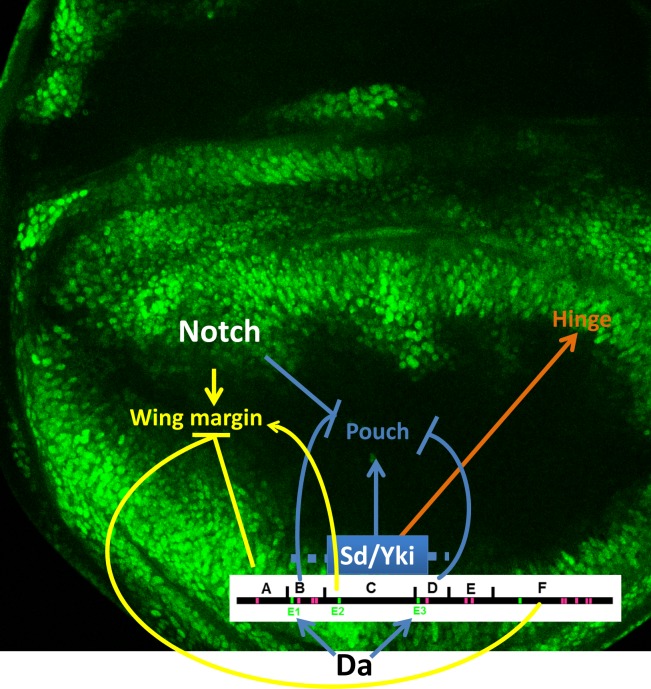

A deletion analysis outlines several major features of ex regulation (Figs 1 and 8). First, the core of the enhancer, centered around the ‘C’ element and probably including contributions from the flanking ‘B’ and ‘D’ elements, is active throughout the wing disc. All this activity depends on both Sd and Yki, suggesting that Yki is active throughout the wing disc. This is consistent with the previous finding that yki is required for growth throughout the wing disc [17,18]. ChIP-seq analysis revealed that Yki binding peaks over ExIntron3 [27]. Although Sd binding has not been mapped yet in Drosophila, it is likely that Sd binding strongly correlates with Yki, as seen for the mammalian YAP1 and TEAD1 proteins [68]. Expression of the Sd/Yki-dependent BC and CD elements provided no evidence of a proximal-distal gradient of Sd/Yki activity. Instead, the overall reduction of ex expression in the central, wing pouch region of the wing disc requires both the B and D regions together, suggesting that two other inputs are both required to achieve this silencing. It does not seem that either of these silencing inputs corresponds to Notch signaling, because although we confirm that Notch is required to silence ex enhancer activity in the wing pouch, it is not required to silence the BCD element.

Fig 8. Model of differential regulation on ex.

In the wing margin proneural region (high SWH activity; low Yki activity), ex is negatively regulated by inputs acting through elements A and F. The E-box site #2 (E2) is required for expression in the wing margin proneural cells while Da acts through E1 and E3 to regulate ex transcription. Sd/Yki regulates ex transcription through element BCD in wing pouch and hinge. Notch acting through element E and other inputs acting through elements B and C repress ex transcription in wing pouch. Note the image of wing disc is adopted from Fig 7D”.

An unexpected aspect of ex transcription regulation is independent regulation of ex enhancer activity in the proneural cells of the anterior wing margin. Activity here was encoded by the BC and CD elements, and depended on an E-box within C (E-box #2). Surprisingly, given the normal role of Notch signaling in lateral inhibition to prevent neural differentiation, the wing margin activity depended positively on N signaling. Anterior wing margin activity was dependent on Da, the obligate heterodimer partner of all proneural genes, indicating that it is possibly encoded by proneural genes of the AS-C. This regulation was unexpected because there was no evidence for ex-LacZ or Exintron3-GFP reporter activity at the anterior wing margin. This is because such expression was silenced by either one of two flanking elements, A and F, acting redundantly. We tested the hypothesis that Sens, which is expressed in the anterior wing margin proneural region and can act as a transcriptional repressor, was responsible for blocking the activity. Although Sens was sufficient to inhibit Exintron3-GFP activity at some ectopic locations, it was not required for Exintron3-GFP repression at any location, including at the anterior wing margin.

We originally identified the ex enhancer through its role in mediating ex transcription in response to elevated Da activity [4]. The Da response was mapped to E-boxes #1 and #3 within elements B and D, respectively. Since Da can bind to DNA as a homodimer, and as no other Class I or Class II bHLH gene is known to be widely expressed in the wing pouch, it is possible that Da homodimers activate this site. The E1 site within element B matches the consensus CACCTG sequence that is preferred by Da-Da homodimers and by homologous E-protein homodimers in mammals [69]. Endogenous Da protein levels are normally elevated at the anterior wing margin, because Emc levels are reduced there, so it is interesting that Exintron3 is activated at the anterior wing margin through distinct E-boxes that differ in sequence from E2 site. One possibility is that it is heterodimers of Da with proneural proteins encoded by AS-C that activates these E-boxes at the anterior wing margin, since we previously showed that ectopically-expressed AS-C proteins can activate the intact enhancer [4]. The consensus E-box site for Sc/Da has been described as GCAGC/GTG and the 5’ flanking base G is essential for the binding specificity of Sc [70]. The E2 site matches both the core sequence and the 5’ flanking base (S2 Fig). In part this could explain why emc loss is detrimental for proliferating progenitor cells in the rest of the wing disc and leads to their ex-dependent loss during growth, in contrast to the proneural cells that normally tolerate elevated Da levels, if Da proteins contribute to distinct dimers in these two situations.

Our analysis shows that multiple regulatory inputs are integrated by the Exintron3 enhancer (Fig 8). Although we confirm previous conclusions that Sd/Yki and Notch signaling regulate ex transcription, our studies indicate that the full enhancer, and hence the widely-used ex-LacZ line, are not straightforward reporters of Yki activity. Instead the smallest sequence that responds to Sd and Yki is active almost uniformly throughout the wing disc, suggesting that this may be the pattern of Yki activity. This may be a useful reporter for SWH activity in future studies. The final ex-LacZ pattern is strongly influenced by additional sequences that silence transcriptional activity in the wing pouch and at the anterior wing margin, in the latter case apparently preventing ex transcription in response to proneural gene activity while preserving sensitivity to ectopic Da expression.

Supporting information

Third instar eye, leg and haltere imaginal discs of ex-LacZ and the indicated genomic sub-fragments. L2: second instar larval stage; eL3: early third instar larval stage.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of three E-box sites (underlined) in BCD region and Sd site (underlined) in D region. The mutated sequences are shown in red. (B-C) BCD-GFP and BCDmE1,3-GFP expression in nub>Da wing discs, respectively. Note that the BCDmE1,3 does not respond to Da overexpression. (D) The same disc shown in 2G. The DAPI staining is used to mark the wing area since there is no GFP activity of BCDmE123Sd-GFP. (E) CDmSd-GFP expression in late third instar wing disc.

(TIF)

(A) Peripordial membrane of en>RFP+yki RNAi (red) staining for ExIntron3-GFP (green) at 25°C. Note that ExIntron3-GFP was decreased in peripordial membrane of wing. (B-C) Leg discs of en>RFP+sd RNAi (red) staining for ExIntron3-GFP and CD-GFP at 30°C, respectively. (D) Wing discs of en>RFP+yki RNAi (red) staining for CD-GFP (green) at 30°C. Note that CD-GFP was decreased in the posterior compartment while some yki knock-down cells close to the proneural region retain a residual GFP expression. (E-F) Wing discs of nub-Gal4 and nub>yki RNAi staining for CD-GFP (green) at 30°C, respectively. Compared to nub-Gal4 control, CD-GFP is decreased in nub>yki RNAi.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Hugo Bellen, Claude Desplan, and Laura Johnston for fly strains. Leica Confocal Imaging was performed in the Analytical Imaging Facility at AECOM. Zeiss confocal microscopy was performed at Neuroscience Program of Academia Sinica (NPAS), Taiwan. Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) were used in this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

LHW received funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 105-2311-B-016-001-MY2; MOST106-3111-Y-016-005) and the Ministry of National Defense-Medical Affairs Bureau, Taiwan (MAB-107-092). Research in NEB’s laboratory was supported by a grant from the NIH (GM047892). Leica Confocal Imaging was performed in the Analytical Imaging Facility at AECOM supported by the NCI (P30CA013330). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript

References

- 1.Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, Tao C, et al. The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 2006; 8(1): 27–36. 10.1038/ncb1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyler DM, Baker NE. Expanded and fat regulate growth and differentiation in the Drosophila eye through multiple signaling pathways. Dev Biol 2007; 305(1):187–201. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djiane A, Zaessinger S, Babaoğlan AB, Bray SJ. Notch inhibits Yorkie activity in Drosophila wing discs. PLoS One 2014; 9(8):e106211 10.1371/journal.pone.0106211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang LH, Baker NE. Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway in a developmental checkpoint monitoring helix-loop-helix proteins. Dev Cell 2015; 32(2):191–202. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badouel C, Gardano L, Amin N, Garg A, Rosenfeld R, Le BT, McNeill H. The FERM-domain protein Expanded regulates Hippo pathway activity via direct interactions with the transcriptional activator Yorkie. Dev Cell 2009; 16(3): 411–420. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh H, Reddy BV, Irvine KD. Phosphorylation-independent repression of Yorkie in Fat-Hippo signaling. Dev Biol 2009; 335(1):188–197. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung HL, Augustine GJ, Choi KW. Drosophila Schip1 Links Expanded and Tao-1 to Regulate Hippo Signaling. Dev Cell 2016; 36(5):511–24. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell 2003; 114(4):457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia J, Zhang W, Wang B, Trinko R, Jiang J.The Drosophila Ste20 family kinase dMST functions as a tumor suppressor by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Genes Dev 2003; 17(20):2514–2519. 10.1101/gad.1134003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pantalacci S, Tapon N, Léopold P. The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell-cycle exit in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5(10):921–927. 10.1038/ncb1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udan RS, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Tao C, Halder G. Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5(10): 914–920. 10.1038/ncb1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu S, Huang J, Dong J, Pan D. hippo encodes a Ste-20 family protein kinase that restricts cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in conjunction with salvador and warts. Cell 2003; 114(4):445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of YAP. Cell 2005; 122(3):421–434. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolo R, Morrison CM, Tao C, Zhang X, Halder G. The bantam microRNA is a target of the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway. Curr Biol 2006; 16(19):1895–904. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson BJ, Cohen SM. The Hippo pathway regulates the bantam microRNA to control cell proliferation and apoptosis in Drosophila. Cell 2006; 126(4):767–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, Jiang J. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev Cell 2008; 14(3):377–387. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zecca M, Struhl G. A feed-forward circuit linking wingless, fat-dachsous signaling, and the warts-hippo pathway to Drosophila wing growth. PLoS Biol 2010; 8(6):e1000386 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh H, Irvine KD. Cooperative regulation of growth by Yorkie and Mad through bantam. Dev Cell 2011; 20(1):109–22. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legoff L, Rouault H, Lecuit T. A global pattern of mechanical stress polarizes cell divisions and cell shape in the growing Drosophila wing disc. Development 2013; 140(19): 4051–9. 10.1242/dev.090878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao Y, Tournier AL, Hoppe A, Kester L, Thompson BJ, Tapon N (2013) Differential proliferation rates generate patterns of mechanical tension that orient tissue growth. EMBO J 2013; 32(21): 2790–803. 10.1038/emboj.2013.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becam I, Rafel N, Hong X, Cohen SM, Milán M. Notch-mediated repression of bantam miRNA contributes to boundary formation in the Drosophila wing. Development 2011; 138(17):3781–9. 10.1242/dev.064774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D. The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Dev Cell 2008; 14(3):388–398. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goulev Y, Fauny JD, Gonzalez-Marti B, Flagiello D, Silber J, Zider A. SCALLOPED interacts with YORKIE, the nuclear effector of the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2008; 18(6):435–441. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharya A, Baker NE. A network of broadly expressed HLH genes regulates tissue-specific cell fates. Cell 2011; 147(4):881–892. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudiere C. Genesis of the Drosophila peripheral nervous system. Trends Genet 1989; 5(8):251–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romani S, Campuzano S, Macagno ER, Modolell J. Expression of achaete and scute genes in Drosophila imaginal discs and their function in sensory organ development. Genes Dev 1989; 3(7):997–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh H, Slattery M, Ma L, Crofts A, White KP, Mann RS, Irvine KD. Genome-wide association of Yorkie with chromatin and chromatin-remodeling complexes. Cell Rep 2013; 3(2):309–18. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blaumueller CM, Mlodzik M. The Drosophila tumor suppressor expanded regulates growth, apoptosis, and patterning during development. Mech Dev 2000; 92(2):251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mlodzik M, Baker NE, Rubin GM. Isolation and expression of scabrous, a gene regulating neurogenesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev 1990; 4(11): 1848–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vincent JP, Girdham CH, O'Farrell PH. A cell-autonomous, ubiquitous marker for the analysis of Drosophila genetic mosaics. Dev Biol 1994; 164(1):328–31. 10.1006/dbio.1994.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janody F, Lee JD, Jahren N, Hazelett DJ, Benlali A, Miura GI, et al. A mosaic genetic screen reveals distinct roles for trithorax and polycomb group genes in Drosophila eye development. Genetics 2004; 166(1):187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wainwright SM, Ish-Horowicz D. Point mutations in the Drosophila hairy gene demonstrate in vivo requirements for basic, helix-loop-helix, and WRPW domains. Mol Cell Biol 1992; 12(6):2475–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nolo R, Abbott LA, and Bellen HJ. Senseless, a Zn finger transcription factor, is necessary and sufficient for sensory organ development in Drosophila. Cell 2000; 102(3): 349–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cronmiller C, Cline TW. The Drosophila sex determination gene daughterless has different functions in the germ line versus the soma. Cell 1987; 48(3):479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staehling-Hampton K, Jackson PD, Clark MJ, Brand AH, Hoffmann FM. Specificity of bone morphogenetic protein-related factors: cell fate and gene expression changes in Drosophila embryos induced by decapentaplegic but not 60A. Cell Growth Differ 1994; 5(6):585–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Presente A, Shaw S, Nye JS, Andres AJ. Transgene-mediated RNA interference defines a novel role for notch in chemosensory startle behavior. Genesis 2002; 34(1–2):165–9. 10.1002/gene.10149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker NE, Li K, Quiquand M, Ruggiero R, Wang LH. Eye development. Methods 2014; 68(1):252–9. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathelier A, Fornes O, Arenillas DJ, Chen CY, Denay G, Lee J, et al. JASPAR 2016: a major expansion and update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44(D1): D110–5. 10.1093/nar/gkv1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loots GG, Ovcharenko I, Pachter L, Dubchak I, Rubin EM. rVista for comparative sequence-based discovery of functional transcription factor binding sites. Genome Res 2002; 12(5):832–9. 10.1101/gr.225502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barolo S, Carver LA, Posakony JW. GFP and beta-galactosidase transformation vectors for promoter/enhancer analysis in Drosophila. Biotechniques 2000; 29(4): 726, 728, 730, 732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubchak I, Brudno M, Loots GG, Mayor C, Pachter L, Rubin EM, Frazer KA. Active Conservation of Noncoding Sequences Revealed by 3-way Species Comparisons. Genome Research 2000; 10(9):1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32: W273–9. 10.1093/nar/gkh458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cubas P, de Celis JF, Campuzano S, Modolell J. Proneural clusters of achaete-scute expression and the generation of sensory organs in the Drosophila imaginal wing disc. Genes Dev 1991; 5(6):996–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skeath JB, Carroll SB. Regulation of achaete-scute gene expression and sensory organ pattern formation in the Drosophila wing. Genes Dev 1991; 5(6):984–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitworth AJ, Russell S. Temporally dynamic response to Wingless directs the sequential elaboration of the proximodistal axis of the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol 2003; 254(2):277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Acar M, Jafar-Nejad H, Giagtzoglou N, Yallampalli S, David G, He Y, et al. Senseless physically interacts with proneural proteins and functions as a transcriptional co-activator. Development 2006; 133(10): 1979–89. 10.1242/dev.02372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimes HL, Gilks CB, Chan TO, Porter S, Tsichlis PN. The Gfi-1 protooncoprotein represses Bax expression and inhibits T-cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93(25):14569–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zweidler-Mckay PA, Grimes HL, Flubacher MM, Tsichlis PN. Gfi-1 encodes a nuclear zinc finger protein that binds DNA and functions as a transcriptional repressor. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16(8):4024–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tong B, Grimes HL, Yang TY, Bear SE, Qin Z, Du K, et al. The Gfi-1B proto-oncoprotein represses p21WAF1 and inhibits myeloid cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 1998; 18(5):2462–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duan Z, Horwitz M. Gfi-1 takes center stage in hematopoietic stem cells. Trends Mol Med 2005; 11(2):49–52. 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basu S, Liu Q, Qiu Y, Dong F. Gfi-1 represses CDKN2B encoding p15INK4B through interaction with Miz-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106(5):1433–8. 10.1073/pnas.0804863106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.modENCODE Consortium, Roy S, Ernst J, Kharchenko PV, Kheradpour P, et al. Identification of functional elements and regulatory circuits by Drosophila modENCODE. Science 2010; 330(6012):1787–97. 10.1126/science.1198374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sasai Y, Kageyama R, Tagawa Y, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S. Two mammalian helix-loop-helix factors structurally related to Drosophila hairy and Enhancer of split. Genes Dev 1992; 6(12B):2620–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tietze K, Oellers N, Knust E. Enhancer of splitD, a dominant mutation of Drosophila, and its use in the study of functional domains of a helix-loop-helix protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992; 89(13):6152–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oellers N, Dehio M, Knust E. bHLH proteins encoded by the Enhancer of split complex of Drosophila negatively interfere with transcriptional activation mediated by proneural genes. Mol Gen Genet 1994; 244(5):465–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohsako S, Hyer J, Panganiban G, Oliver I, Caudy M. Hairy function as a DNA-binding helix-loop-helix repressor of Drosophila sensory organ formation. Genes Dev 1994; 8(22):2743–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Doren M, Bailey AM, Esnayra J, Ede K, Posakony JW. Negative regulation of proneural gene activity: hairy is a direct transcriptional repressor of achaete. Genes Dev 1994; 8(22):2729–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhattacharya A, Baker NE. The role of the bHLH protein hairy in morphogenetic furrow progression in the developing Drosophila eye. PLoS One 2012; 7(10):e47503 10.1371/journal.pone.0047503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher A, Caudy M. The function of hairy-related bHLH repressor proteins in cell fate decisions. Bioessays 1998; 20(4):298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feng Y, Irvine KD. Fat and expanded act in parallel to regulate growth through warts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104(51): 20362–7. 10.1073/pnas.0706722105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ling C, Zheng Y, Yin F, Yu J, Huang J, Hong Y, et al. The apical transmembrane protein Crumbs functions as a tumor suppressor that regulates Hippo signaling by binding to Expanded. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010; 107(23): 10532–10537. 10.1073/pnas.1004279107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson BS, Huang J, Hong Y, Moberg KH. Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein Expanded. Curr Biol 2010; 20(7): 582–90. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boedigheimer M, Laughon A. Expanded: a gene involved in the control of cell proliferation in imaginal discs. Development 1993; 118(4): 1291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deng H, Wang W, Yu J, Zheng Y, Qing Y, Pan D. Spectrin regulates Hippo signaling by modulating cortical actomyosin activity. Elife 2015; 4:e06567 10.7554/eLife.06567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma X, Guo X, Richardson HE, Xu T, Xue L. POSH regulates Hippo signaling through ubiquitin-mediated expanded degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115(9):2150–2155. 10.1073/pnas.1715165115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang H, Li C, Chen H, Wei C, Dai F, Wu H, et al. SCF(Slmb) E3 ligase-mediated degradation of Expanded is inhibited by the Hippo pathway in Drosophila. Cell Res 2015; 25(1):93–109. 10.1038/cr.2014.166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwank G, Restrepo S, Basler K. Growth regulation by Dpp: an essential role for Brinker and a non-essential role for graded signaling levels. Development 2008; 135(24): 4003–13. 10.1242/dev.025635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stein C, Bardet AF, Roma G, Bergling S, Clay I, Ruchti A, et al. YAP1 Exerts Its Transcriptional Control via TEAD-Mediated Activation of Enhancers. PLoS Genet 11(8):e1005465 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20(2):429–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Powell LM, Zur Lage PI, Prentice DR, Senthinathan B, Jarman AP. The proneural proteins Atonal and Scute regulate neural target genes through different E-box binding sites. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24(21):9517–26. 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9517-9526.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Third instar eye, leg and haltere imaginal discs of ex-LacZ and the indicated genomic sub-fragments. L2: second instar larval stage; eL3: early third instar larval stage.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of three E-box sites (underlined) in BCD region and Sd site (underlined) in D region. The mutated sequences are shown in red. (B-C) BCD-GFP and BCDmE1,3-GFP expression in nub>Da wing discs, respectively. Note that the BCDmE1,3 does not respond to Da overexpression. (D) The same disc shown in 2G. The DAPI staining is used to mark the wing area since there is no GFP activity of BCDmE123Sd-GFP. (E) CDmSd-GFP expression in late third instar wing disc.

(TIF)

(A) Peripordial membrane of en>RFP+yki RNAi (red) staining for ExIntron3-GFP (green) at 25°C. Note that ExIntron3-GFP was decreased in peripordial membrane of wing. (B-C) Leg discs of en>RFP+sd RNAi (red) staining for ExIntron3-GFP and CD-GFP at 30°C, respectively. (D) Wing discs of en>RFP+yki RNAi (red) staining for CD-GFP (green) at 30°C. Note that CD-GFP was decreased in the posterior compartment while some yki knock-down cells close to the proneural region retain a residual GFP expression. (E-F) Wing discs of nub-Gal4 and nub>yki RNAi staining for CD-GFP (green) at 30°C, respectively. Compared to nub-Gal4 control, CD-GFP is decreased in nub>yki RNAi.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.