Abstract

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently occurring form of all cancers. The cost of care for BCC is one of the highest for all cancers in the Medicare population in the United States. Activation of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway appears to be a key driver of BCC development. Studies involving mouse models have provided evidence that activation of the glioma-associated oncogene (GLI) family of transcription factors is a key step in the initiation of the tumorigenic program leading to BCC. Activation of the Wnt pathway is also observed in BCCs. In addition, the Wnt signaling pathway has been shown to be required in Hh pathway-driven development of BCC in a mouse model. Cross-talks between Wnt and Hh pathways have been observed at different levels, yet the mechanisms of these cross-talks are not fully understood. In this review, we examine the mechanism of cross-talk between Wnt and Hh signaling in BCC development and its potential relevance for treatment. Recent studies have identified insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1), a direct target of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, as the factor that binds to GLI1 mRNA and upregulates its levels and activities. This mode of regulation of GLI1 appears important in BCC tumorigenesis and could be explored in the treatment of BCCs.

Keywords: basal cell carcinoma, Hh, Wnt, cross-talk, IGF2BP1, GLI1, therapeutic mechanisms

1. Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common form of cancer, affecting more than two million Americans each year. The vast majority of BCCs occur sporadically, but patients with the rare heritable disorder, basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS), have marked susceptibility to developing BCCs [1]. BCC used to be more common in people over age 40, but is now also diagnosed in the younger population [2,3,4]. BCC lesions occur mostly on areas of skin that are regularly exposed to sunlight or other ultraviolet radiation, particularly the face, ears, neck, scalp, shoulders, and back. Meanwhile, BCC has also been reported from virtually every part of the skin surface [5]. Anyone with a history of sun exposure can develop BCC. However, people who are at highest risk are the ones in the fair skinned populations [6,7,8]. Immunocompromised patients have also been reported to have a higher risk of developing BCC than the general population [9,10] and BCCs appear to show a more aggressive behavior in these patients [11]. Chronic exposure to arsenic might also be responsible for the incidence of BCC development [12,13,14]. BCCs can be generally classified in four groups according to the form of growth pattern. These groups are: (i) the nodular including the micronodular form; (ii) the infiltrative including the morphoeic form; (iii) the superficial, apparently multicentric form, and (iv) the mixed form including a combination of any two or all of the types. Micronodular, infiltrative; and morpheaform patterns often show a greater aggressive behavior [2,3]. Primary lesions in the head and neck have been shown to recur frequently, while those affecting the ears, the genital organs, and other mucosal surfaces show a high propensity to metastasize (reviewed in [15]). Although the death rate from BCCs is low as BCC rarely metastasizes [5,16], if untreated BCC can destroy the tissues and nearby organs, causing ulceration and disfigurement. Advanced BCCs are resistant to treatment and associated with high morbidity [1,17,18,19]. BCC morbidity is considerable and constitutes a huge burden on the healthcare service worldwide. The cost of care for BCC patients is one of the highest for all cancers in the Medicare population in the United States [15]. In addition, people who develop BCC are predisposed to developing further BCCs and other malignancies [20].

The Hh signaling pathway has been identified as one of the drivers of BCC development [1,21,22]. Drugs targeting this pathway have been developed in the treatment of advanced, inoperable, or metastatic BCCs. Those drugs have been particularly directed against smoothened (SMO), which is an important component of the Hh pathway. Although this treatment method has been proven beneficial in many cases [23,24], the development of resistance remains a major concern as about 20% of patients develop resistance during the first year of treatment [19,23,25]. Studies have now shown that other pathways interact with the Hh pathway in BCC development [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Interestingly, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is one of those pathways. Investigating those interactions could be valuable in identifying better strategies in the treatment of advanced, inoperable and/or resistant BCCs. In this review, we have discussed specifically what is known on the cross-talk between Hh and Wnt signaling pathways in BCC development, based on the literature covering the last two decades and the potential relevance of this cross-talk in the treatment of SMO inhibitors’ resistant BCCs.

2. BCC and Hh Signaling Pathway

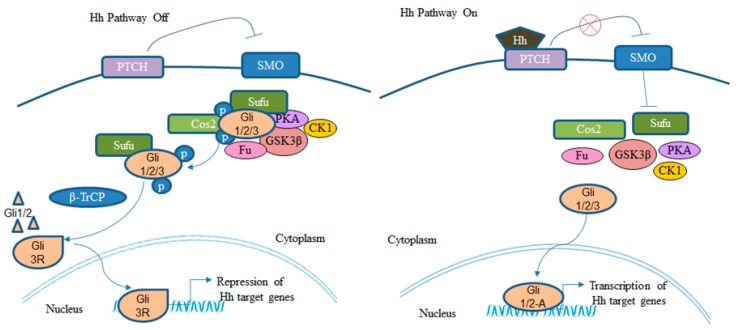

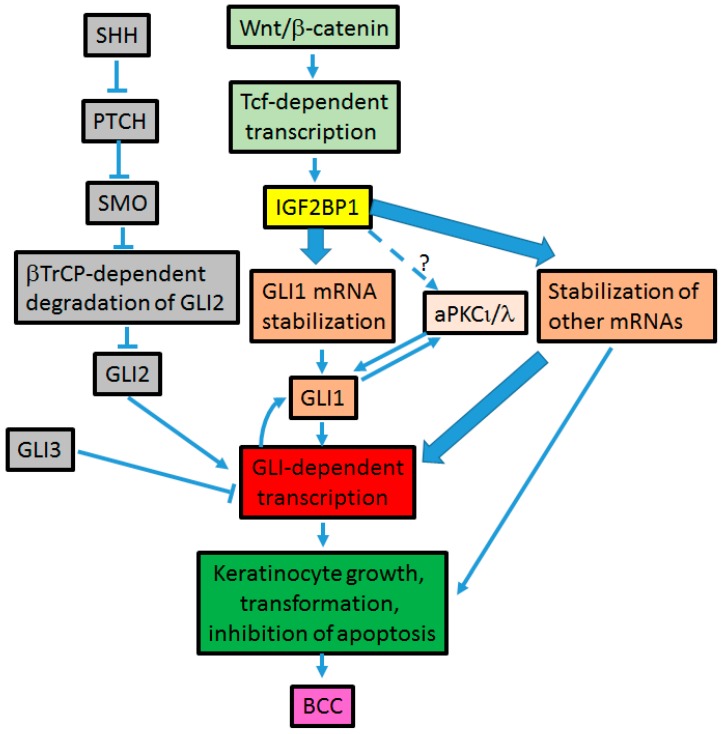

The Hh signaling is a critical pathway governing embryonic development and stem cell maintenance. However, its aberrant regulation is implicated in the development of many cancers including BCC [33]. The Hh pathway is mediated by the Ci/GLI family of zinc finger transcription factors. The transmembrane receptors Patched (PTCH) and Smoothened (SMO) play critical roles in the Hh signaling. In the absence of the Hh ligand, its receptor PTCH inhibits the function of SMO, thereby inactivating the Hh signaling. When the Hh ligand binds to PTCH, the inhibitory effect of PTCH on SMO is removed leading to the activation of the transcription factor Ci/GLI (Figure 1) (reviewed in [34]). Three GLI genes have been identified in vertebrates. GLI1 being predominantly a transcriptional activator, whereas GLI2 and GLI3 can perform as both activators and repressors [35,36]. Activating mutations of SMO or suppressing mutations of PTCH have been shown to constitutively activate the Hh signaling pathway [33]. Studies have also shown that constitutive activation of Hh signaling pathway is a key factor driving the development of BCC [1,37]. Loss of function mutation of the PTCH gene and gain of function mutation of the SMO gene have been observed in BCCs [21,22]. Indeed, patients with the autosomal dominant nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome are predisposed to BCC and medulloblastoma since they have inherited mutations in one allele of the PTCH1 gene, and BCCs from these patients lack the normal PTCH1 gene [38]. Over-expression of Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) has been shown to result in the formation of BCC in murine studies [37], and activation of GLI1 has been identified as a key step in the initiation of the tumorigenic program leading to BCC [39]. GLI1 is highly expressed in human BCC [40]. Therefore, inhibiting GLI1 expression and activity would be a critical step towards BCC treatment. Over-expression of GLI1 in BCCs appears modulated not only by the upstream Hh signaling but also by alternative mechanisms [30,31] (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This warrants the exploration of those mechanisms, especially their interaction with the Hh pathway while developing new strategies in BCC treatment. One such mechanism modulating GLI1 expression and activity is Wnt/β-catenin-dependent [27,41].

Figure 1.

The canonical Hh signaling pathway. GLI 3R; GLI 3 repressor; GLI 1/2-A; GLI 1 and 2 activators [34,42].

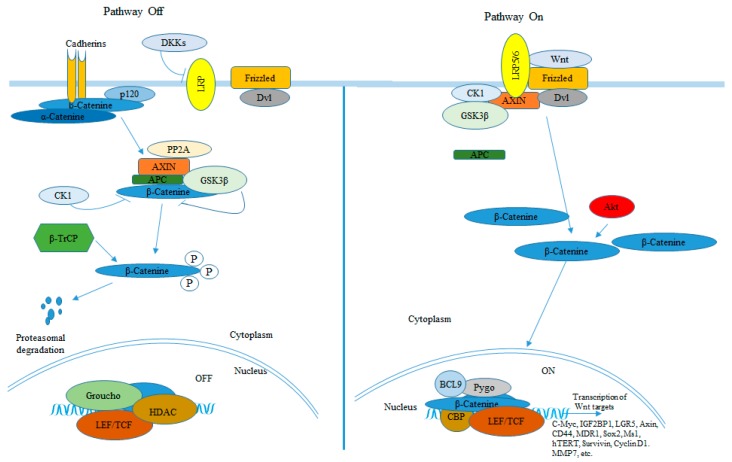

Figure 2.

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [55,56,57,58,60,64,66,68].

Figure 3.

Cross-talk between Wnt and Hh signaling pathways [27,41,88,89,90];  mechanisms of insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein (IGF2BP1) -driven BCC tumorigenesis;

mechanisms of insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein (IGF2BP1) -driven BCC tumorigenesis;  potential mechanism.

potential mechanism.

3. BCC and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

The Wnt signaling is another pathway implicated in basal cell carcinoma development. Similarly to the Hh pathway, the Wnt signaling pathway plays a critical role in patterning and cell proliferation of embryonic and adult tissues. However, aberrant activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is responsible for the development of many human cancers as well [43]. β-catenin is a pivotal player in the signaling pathway initiated by Wnt proteins. In the absence of Wnt signaling, β-catenin, which is found in a complex together with axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and glycogen synthase kinase β (GSK3β), is phosphorylated by GSK3β and subsequently ubiquitinated and degraded in the proteasomes. Binding of Wnt proteins to the receptors Frizzled and LDL-receptor related protein (LRP) families on the cell surface leads to GSK3β inactivation resulting in the release of unphosphorylated β-catenin from the multiprotein complex. β-catenin is then translocated into the nucleus, where it binds to Tcf/Lef causing the activation of Wnt target genes (Figure 2). Loss of function mutation of the tumor suppressor APC, stabilizing mutations of β-catenin, or mutations in axin result in constitutive activation of the Wnt signaling pathway [44]. Aberrant activation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway has been implicated in the development of many cancers including colorectal cancer (reviewed in [45]), breast cancer (reviewed in [46]), and melanoma [47,48]. Activation of the Wnt pathway has also been observed in BCCs as shown by over-expression of Wnt proteins [49,50] and the presence of β-catenin harboring stabilizing mutations [51]. Additionally, cytoplasmic and/or nuclear localization of β-catenin have been observed in different human BCC tumors [50,52,53,54].

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is known to promote cell growth, morphogenesis, and stem cell maintenance. It is also one of the major pathways stimulating the stemness of a rare population of cells in the tumor bulk responsible for the resistance of cancer to conventional chemo treatment, resulting in the relapse of the disease and metastasis. The Wnt/β-catenin sustains the proliferation and self-renewal capabilities of those particular cells through regulation of its many targets. hTERT is one of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling direct targets. By upregulating hTERT expression and activity in cancer cells, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling stimulates their immortality [55,56], their invasion and metastasis capabilities [57]. Aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling was also shown to upregulate BIRC5/Survivin [58,59], which in turn inhibits caspase-3 and -7 and prevents apoptosis adding to the immortality of cancer cells. Musashi-1 [60,61,62,63], and Sox2 [64,65] are markers of stem cells that are overexpressed in many cancers and contribute to their tumorigenic phenotype by stimulating cell proliferation and drug resistance, respectively. These stem cell markers have been demonstrated to be upregulated by the Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling also promotes drug resistance by regulating other genes including MDR-1 [66,67], CD44, MMP7 [68] and IL-10 [69]. The Wnt/β-catenin regulates many genes involved in cell cycle progression, migration, invasion, and extracellular matrix remodeling. However, these Wnt targets have not been specifically identified in BCC. But, they could possibly contribute to the resistance of advanced BCC to treatment. Studies have shown that inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs [70,71,72] and could improve the efficacy of immunotherapy [73,74]. Therefore, targeting the Wnt pathway could be an effective approach in the treatment of advanced, inoperable and/or resistant BCCs.

4. Cross-Talk between Hh and Wnt Signaling Pathways in BCC Development (Figure 3)

Interaction between Hh and Wnt signaling has been shown to be fundamental in the coordination of key processes during embryonic development, stem cell maintenance, and tumorigenesis. However, the mechanisms of those interactions are still not fully understood. In normal skin, both Wnt and Hh signaling are required during hair follicle morphogenesis as Wnt signaling initiates hair bud formation, whereas Hh signaling proliferates the follicle epithelium needed to form a mature follicle [75,76,77,78,79]. Cross-talk between Wnt and Hh signaling seems to exist in skin pathogenesis as well. Upregulation of Wnt genes by GLI1 was shown in BCC-like tumors in late tailbud tadpole stages [49]. Additionally, Wnt proteins were found to be overexpressed in human BCC tumors [49,50]. The first evidence of a requirement of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in Hh pathway-driven development of BCCs was shown in a BCC mouse model, M2SMO [80]. The study demonstrated that blockade of the canonical Wnt signaling prevented Hh signaling-driven tumorigenesis [80]. Wnt and Hh are two major pathways that have been postulated to interact at multiple levels [49,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88], yet the mechanisms of these interactions are not clear. Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which both pathways relate to each other in BCC would be critical in the perspective of developing novel therapeutic approaches in the treatment of this disease and alleviate the cost of care for BCCs.

In our previous studies, we demonstrated that the mechanism of cross-talk between Hh and Wnt signaling pathways in BCC development employs GLI1 mRNA stabilization by the insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein (IGF2BP1) [41]. IGF2BP1 (also known as IMP1, CRD-BP, and ZBP1) is a direct target of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [89]. We showed that IGF2BP1 binds to a segment of the coding region of GLI1 mRNA and stabilizes it. We also demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling induces the expression and transcriptional activity of GLI1 in an IGF2BP1 dependent manner [41]. The binding region of IGF2BP1 on GLI 1 mRNA that we identified was narrowed to a 61-nucleotide segment in a different study and was shown to exhibit two characteristic stem-loop motifs [90]. The use of GLI1 mRNA competitors harboring the two stem-loops effectively prevented GLI1 mRNA-IGF2BP1 interaction in vitro. Knockdown of IGF2BP1 in colorectal and breast cancer cell lines using the RNAi approach significantly lowered GLI1 expression in these cells. Furthermore, the RNA oligo that effectively competed with GLI1 mRNA-IGF2BP1 interaction was efficient at reducing GLI1 expression in colorectal and breast cancer cells [90]. IGF2BP1 is over-expressed in BCC and its expression positively correlates with the activation of both Wnt and Hh signaling pathways [27].

One of the obstacles in studying BCC development is the absence of human BCC cell lines. We developed and characterized a human BCC cell line, the UW-BCC1 cell line. IGF2BP1 is highly expressed in this cell line. Knockdown of IGF2BP1 in this cell line using a specific IGF2BP1 shRNA significantly reduced its growth, proliferation, invasion capability, as well as promoted its apoptosis. Inhibition of IGF2BP1 had a more pronounced effect on the tumorigenic phenotype of this cell line than inhibition of GLI1, probably due to the pleiotropic effect of IGF2BP1 on other oncogenes including c-myc and β-TrCP1. Collectively, the regulation of GLI1 expression and activities by IGF2BP1 plays an important role in BCC development [27]. A significant clinical relevance of the mode of action of IGF2BP1 for BCC treatment is that the regulation of GLI-dependent transcriptional activity by IGF2BP1 seems SMO independent [41]. Additionally, inhibition of IGF2BP1 appears to prevent PTCH mutant driven GLI transcriptional activity [27]. This implies that the Hh signaling could be inhibited by downregulating IGF2BP1 and therefore bypassing SMO. Additional studies using BCC cell lines are warranted to further confirm this novel mechanism that could be explored in the development of new treatment strategies for BCCs especially for SMO inhibitor resistant BCCs.

A previous study showed that IGF2BP1 binds to the coding region of β-TrCP1 mRNA and shields it from degradation by a microRNA [91]. A large number of microRNAs has been identified in BCCs, some of which are tumor suppressors [92]. IGF2BP1 might achieve its oncogenic property in BCCs by binding to GLI1 mRNA and shielding it from degradation by a microRNA as well. This possibility should be explored for BCC treatment.

5. BCC Treatment

Surgical resection and/or radiation therapy is the mainstream of treatment for small, early stage, and localized BCCs. However, different approaches are used in the treatment of BCC depending on the BCC subtype, its stage of development, and its location. Imiquimod [93,94,95,96] and topical 5-fluorouracil [97] have been approved in the treatment of superficial BCCs. The photodynamic therapy [98,99] is another approach used in the treatment of nodular and superficial BCCs. However, treatment options for advanced and metastatic BCCs are still emerging. New drugs approved or in clinical trials for the treatment of advanced or metastatic BCCs include the SMO inhibitors sonidegib [100,101] and antifungal itraconazole [102]. The systematic use of vismodegib has proven successful in many cases [23,24,103,104]. Vismodegib is the SMO inhibitor that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of advanced/inoperable and metastatic BCCs [23]. Although the use of this drug showed a significant response rate (48% in advanced and metastatic BCCs) [23,24], about 20% of patients presenting advanced or metastatic BCC develop resistance during the first year [105]. Drug resistance is an obstacle that impairs the success of cancer therapies. Recent studies demonstrated that vismodegib resistant BCCs are still addicted to the Hh pathway and that mutation in the ligand binding pocket of SMO is one of the mechanisms developed by BCC to resist treatment to vismodegib [31,106]. The use of some GLI antagonists downstream of SMO was found to be effective in suppressing the Hh pathway in SMO inhibitor resistant BCCs. Those antagonists include an inhibitor of atypical Protein Kinase C-iota/lambda (aPKC-ι/λ) that phosphorylates GLI1, and arsenic trioxide that inhibits GLI2 [31]. Therefore, targeting factors downstream of SMO was proposed as a better approach to overcome resistance [31]. IGF2BP1 regulates GLI1 downstream of SMO and appears to be an attractive candidate gene to target in the treatment of BCCs including SMO inhibitor resistant BCCs.

IGF2BP1 is a multifunctional RNA-binding protein involved in different processes such as mRNA turnover, translation control, and localization. IGF2BP1 expression is temporally and spatially regulated. IGF2BP1 is abundantly expressed in fetal and neonatal tissues. Its expression is crucial in the regulation of many transcripts essential for normal embryonic development [107,108,109]. While scarce or absent in normal adult tissues, IGF2BP1 is found to be de novo activated and/or overexpressed in various cancers [48,89,108,109,110,111,112,113]. Its expression was shown to be associated with the most aggressive form of some cancers [108,111,114]. IGF2BP1 also regulates other factors implicated in cancer development, metastasis, and resistance to drug including c-myc [115], MDR1 [116], β-TrCP1 [89], CD-44 [117], and cIAP1 [118]. We showed that Hh signaling could be inhibited by downregulating IGF2BP1 and this mechanism bypasses SMO [41]. This mode of regulation of oncogenes by IGF2BP1 portrays it as an attractive target in the treatment of BCCs including SMO inhibitor resistant BCCs. IGF2BP1 binds to its targets to regulate their expression and activities. Identifying small molecules that prevent IGF2BP1-GLI1 mRNA interaction would be beneficial in BCC treatment.

6. Conclusions

Although the number of new cases of BCC is still on the rise each year, the molecular mechanisms driving its development are still unclear. A cross-talk between Wnt and Hh signaling pathways appears to play a significant role in BCC development. This cross-talk is modulated by IGF2BP1, which activates GLI1, the key element driving BCC development. Inhibiting IGF2BP1 or preventing its interaction with GLI1 mRNA seems to represent a sound approach in BCC treatment. However, further studies including in vivo studies to delineate the contribution of IGF2BP1 to BCC development will bring new insights on the potential candidacy of IGF2BP1 as a target for therapy. This may potentially lead to the designing of new agents effective in the treatment of BCCs, including advanced, inoperable, or SMO inhibitor resistant BCCs. This would alleviate the cost of care for BCCs and reduce the morbidity associated with the advanced form of this disease. Additionally, this would represent a better alternative to multiple surgical procedures especially for immunocompromised patients and patients with basal cell nevus syndrome who can develop tens to hundreds of BCCs in their lifetime.

Author Contributions

F.K.N. and C.G.Y. conceived, designed, and drafted the manuscript; V.S.S. and P.B.T. participated in the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

The research described in this publication was made possible by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIMHD-G12MD007581) through the Research Centers in Minority Institutions-Center for Environmental Health (RCMI-CEH) at Jackson State University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Epstein E.H. Basal cell carcinomas: Attack of the hedgehog. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrc2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milroy C.J., Horlock N., Wilson G.D., Sanders R. Aggressive basal cell carcinoma in young patients: Fact or fiction? Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2000;53:393–396. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leffell D.J., Headington J.T., Wong D.S., Swanson N.A. Aggressive-growth basal cell carcinoma in young adults. Arch. Dermatol. 1991;127:1663–1667. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1991.01680100063005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christenson L.J., Borrowman T.A., Vachon C.M., Tollefson M.M., Otley C.C., Weaver A.L., Roenigk R.K. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rippey J.J. Why classify basal cell carcinomas? Histopathology. 1998;32:393–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin A.I., Chen E.H., Ratner D. Basal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2262–2269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra044151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomas A., Leonardi-Bee J., Bath-Hextall F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012;166:1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karagas M.R., Greenberg E.R., Spencer S.K., Stukel T.A., Mott L.A. Increase in incidence rates of basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer in New Hampshire, USA. New Hampshire Skin Cancer Study Group. Int. J. Cancer. 1999;81:555–559. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990517)81:4<555::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Euvrard S., Kanitakis J., Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1681–1691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanik E.L., Pfeiffer R.M., Freedman D.M., Weinstock M.A., Cahoon E.K., Arron S.T., Chaloux M., Connolly M.K., Nagarajan P., Engels E.A. Spectrum of immune-related conditions associated with risk of keratinocyte cancers among elderly adults in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:998–1007. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oram Y., Orengo I., Griego R.D., Rosen T., Thornby J. Histologic patterns of basal cell carcinoma based upon patient immunostatus. Dermatol. Surg. 1995;21:611–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulshan S., Rahman M.J., Sarkar R., Ghosh S., Hazra R. An Interesting Case of Basal Cell Carcinoma with Raynaud’s Phenomenon Following Chronic Arsenic Exposure. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2016;55:100–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng P.S., Weng S.F., Chiang C.H., Lai F.J. Relationship between arsenic-containing drinking water and skin cancers in the arseniasis endemic areas in Taiwan. J. Dermatol. 2016;43:181–186. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kile M.L., Hoffman E., Rodrigues E.G., Breton C.V., Quamruzzaman Q., Rahman M., Mahiuddin G., Hsueh Y.M., Christiani D.C. A pathway-based analysis of urinary arsenic metabolites and skin lesions. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011;173:778–786. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahhas A.F., Scarbrough C.A., Trotter S. A Review of the Global Guidelines on Surgical Margins for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2017;10:37–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCusker M., Basset-Seguin N., Dummer R., Lewis K., Schadendorf D., Sekulic A., Hou J., Wang L., Yue H., Hauschild A. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: Prognosis dependent on anatomic site and spread of disease. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014;50:774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson N.M., Holliday A.C., Luyimbazi D.T., Phillips M.A., Collins G.R., Grider D.J. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma with loss of p63 and mismatch repair proteins. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wysong A., Aasi S.Z., Tang J.Y. Update on metastatic basal cell carcinoma: A summary of published cases from 1981 through 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:615–616. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson G.A., Kelly D., Prior L., Stanley E., MacEneaney O., Walsh T., Kelly C.M. An unusual case of basal cell carcinoma of the vulva with lung metastases. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2016;18:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong C.S., Strange R.C., Lear J.T. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:794–798. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reifenberger J., Wolter M., Knobbe C.B., Kohler B., Schonicke A., Scharwachter C., Kumar K., Blaschke B., Ruzicka T., Reifenberger G. Somatic mutations in the PTCH, SMOH, SUFUH and TP53 genes in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005;152:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Zwaan S.E., Haass N.K. Genetics of basal cell carcinoma. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2010;51:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekulic A., Migden M.R., Oro A.E., Dirix L., Lewis K.D., Hainsworth J.D., Solomon J.A., Yoo S., Arron S.T., Friedlander P.A., et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2171–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Axelson M., Liu K., Jiang X., He K., Wang J., Zhao H., Kufrin D., Palmby T., Dong Z., Russell A.M., et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval: Vismodegib for recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:2289–2293. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang J.Y., Mackay-Wiggan J.M., Aszterbaum M., Yauch R.L., Lindgren J., Chang K., Coppola C., Chanana A.M., Marji J., Bickers D.R., et al. Inhibiting the hedgehog pathway in patients with the basal-cell nevus syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2180–2188. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhary S.C., Tang X., Arumugam A., Li C., Srivastava R.K., Weng Z., Xu J., Zhang X., Kim A.L., McKay K., et al. Shh and p50/Bcl3 signaling crosstalk drives pathogenesis of BCCs in Gorlin syndrome. Oncotarget. 2015;6:36789–36814. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noubissi F.K., Kim T., Kawahara T.N., Aughenbaugh W.D., Berg E., Longley B.J., Athar M., Spiegelman V.S. Role of CRD-BP in the growth of human basal cell carcinoma cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014;134:1718–1724. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu N., Liu G.J., Liu J. Genetic association between TNF-alpha promoter polymorphism and susceptibility to squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim A.L., Back J.H., Zhu Y., Tang X., Yardley N.P., Kim K.J., Athar M., Bickers D.R. AKT1 Activation is Obligatory for Spontaneous BCC Tumor Growth in a Murine Model that Mimics Some Features of Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016;9:794–802. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atwood S.X., Oro A.E. “Atypical” regulation of Hedgehog-dependent cancers. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:133–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atwood S.X., Sarin K.Y., Whitson R.J., Li J.R., Kim G., Rezaee M., Ally M.S., Kim J., Yao C., Chang A.L., et al. Smoothened variants explain the majority of drug resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakshi A., Chaudhary S.C., Rana M., Elmets C.A., Athar M. Basal cell carcinoma pathogenesis and therapy involving hedgehog signaling and beyond. Mol. Carcinog. 2017;56:2543–2557. doi: 10.1002/mc.22690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wicking C., Smyth I., Bale A. The hedgehog signalling pathway in tumorigenesis and development. Oncogene. 1999;18:7844–7851. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Athar M., Li C., Kim A.L., Spiegelman V.S., Bickers D.R. Sonic hedgehog signaling in Basal cell nevus syndrome. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4967–4975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohatgi R., Scott M.P. Patching the gaps in Hedgehog signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/ncb435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lum L., Beachy P.A. The Hedgehog response network: Sensors, switches, and routers. Science. 2004;304:1755–1759. doi: 10.1126/science.1098020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oro A.E., Higgins K.M., Hu Z., Bonifas J.M., Epstein E.H., Jr., Scott M.P. Basal cell carcinomas in mice overexpressing sonic hedgehog. Science. 1997;276:817–821. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hahn H., Wicking C., Zaphiropoulous P.G., Gailani M.R., Shanley S., Chidambaram A., Vorechovsky I., Holmberg E., Unden A.B., Gillies S., et al. Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell. 1996;85:841–851. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsson M., Unden A.B., Krause D., Malmqwist U., Raza K., Zaphiropoulos P.G., Toftgard R. Induction of basal cell carcinomas and trichoepitheliomas in mice overexpressing GLI-1 [In Process Citation] Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3438–3443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green J., Leigh I.M., Poulsom R., Quinn A.G. Basal cell carcinoma development is associated with induction of the expression of the transcription factor Gli-1. Br. J. Dermatol. 1998;139:911–915. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noubissi F.K., Goswami S., Sanek N.A., Kawakami K., Minamoto T., Moser A., Grinblat Y., Spiegelman V.S. Wnt signaling stimulates transcriptional outcome of the Hedgehog pathway by stabilizing GLI1 mRNA. Cancer Res. 2009 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Justilien V., Fields A.P. Molecular pathways: Novel approaches for improved therapeutic targeting of Hedgehog signaling in cancer stem cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:505–513. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polakis P. The oncogenic activation of beta-catenin. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1999;9:15–21. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nusse R. Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res. 2005;15:28–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taipale J., Beachy P.A. The Hedgehog and Wnt signalling pathways in cancer. Nature. 2001;411:349–354. doi: 10.1038/35077219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takebe N., Warren R.Q., Ivy S.P. Breast cancer growth and metastasis: Interplay between cancer stem cells, embryonic signaling pathways and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Breast Cancer Res. BCR. 2011;13:211. doi: 10.1186/bcr2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim T., Havighurst T., Kim K., Albertini M., Xu Y.G., Spiegelman V.S. Targeting insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) in metastatic melanoma to increase efficacy of BRAF(V600E) inhibitors. Mol. Carcinog. 2018;57:678–683. doi: 10.1002/mc.22786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elcheva I., Tarapore R.S., Bhatia N., Spiegelman V.S. Overexpression of mRNA-binding protein CRD-BP in malignant melanomas. Oncogene. 2008;27:5069–5074. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mullor J.L., Dahmane N., Sun T., Ruiz i Altaba A. Wnt signals are targets and mediators of Gli function. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:769–773. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lo Muzio L., Pannone G., Staibano S., Mignogna M.D., Grieco M., Ramires P., Romito A.M., De Rosa G., Piattelli A. WNT-1 expression in basal cell carcinoma of head and neck. An immunohistochemical and confocal study with regard to the intracellular distribution of beta-catenin. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:565–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doglioni C., Piccinin S., Demontis S., Cangi M.G., Pecciarini L., Chiarelli C., Armellin M., Vukosavljevic T., Boiocchi M., Maestro R. Alterations of beta-catenin pathway in non-melanoma skin tumors: Loss of alpha-ABC nuclear reactivity correlates with the presence of beta-catenin gene mutation. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;163:2277–2287. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63585-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamazaki F., Aragane Y., Kawada A., Tezuka T. Immunohistochemical detection for nuclear beta-catenin in sporadic basal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001;145:771–777. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Bahrawy M., El-Masry N., Alison M., Poulsom R., Fallowfield M. Expression of beta-catenin in basal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003;148:964–970. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saldanha G., Ghura V., Potter L., Fletcher A. Nuclear beta-catenin in basal cell carcinoma correlates with increased proliferation. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004;151:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaitner S., Reiche J.A., Schaffauer A.J., Hiendlmeyer E., Herbst H., Brabletz T., Kirchner T., Jung A. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) is a target gene of beta-catenin in human colorectal tumors. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3331–3338. doi: 10.4161/cc.21790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y., Toh L., Lau P., Wang X. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) is a novel target of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in human cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:32494–32511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.368282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang B., Xie R., Qin Y., Xiao Y.F., Yong X., Zheng L., Dong H., Yang S.M. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) promotes gastric cancer invasion through cooperating with c-Myc to upregulate heparanase expression. Oncotarget. 2016;7:11364–11379. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen X., Duan N., Zhang C., Zhang W. Survivin and Tumorigenesis: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. J. Cancer. 2016;7:314–323. doi: 10.7150/jca.13332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang J., Lyu H., Wang J., Liu B. MicroRNA regulation and therapeutic targeting of survivin in cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015;5:20–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rezza A., Skah S., Roche C., Nadjar J., Samarut J., Plateroti M. The overexpression of the putative gut stem cell marker Musashi-1 induces tumorigenesis through Wnt and Notch activation. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:3256–3265. doi: 10.1242/jcs.065284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang M.R., Xi S., Shukla V., Hong J.A., Chen H., Xiong Y., Ripley R.T., Hoang C.D., Schrump D.S. The Pluripotency Factor Musashi-2 Is a Novel Target for Lung Cancer Therapy. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018;15:S124. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201707-608MG. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chatterji P., Rustgi A.K. RNA Binding Proteins in Intestinal Epithelial Biology and Colorectal Cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2018;24:490–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y., Fan Y., Wang X., Huang Z., Shi K., Zhou B. Musashi-2 is a prognostic marker for the survival of patients with cervical cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:5425–5432. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Piva M., Domenici G., Iriondo O., Rabano M., Simoes B.M., Comaills V., Barredo I., Lopez-Ruiz J.A., Zabalza I., Kypta R., et al. Sox2 promotes tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014;6:66–79. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y., Dong J., Li D., Lai L., Siwko S., Li Y., Liu M. Lgr4 regulates mammary gland development and stem cell activity through the pluripotency transcription factor Sox2. Stem Cells. 2013;31:1921–1931. doi: 10.1002/stem.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang H., Zhang X., Wu X., Li W., Su P., Cheng H., Xiang L., Gao P., Zhou G. Interference of Frizzled 1 (FZD1) reverses multidrug resistance in breast cancer cells through the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Cancer Lett. 2012;323:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamada T. Studies on molecular mechanism of drug resistance of mycobacteria and recombinant BCG to prevent infection of intracellular pathogens. Nihon Saikingaku Zasshi. 2000;55:613–627. doi: 10.3412/jsb.55.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duchartre Y., Kim Y.M., Kahn M. The Wnt signaling pathway in cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2016;99:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yaguchi T., Goto Y., Kido K., Mochimaru H., Sakurai T., Tsukamoto N., Kudo-Saito C., Fujita T., Sumimoto H., Kawakami Y. Immune suppression and resistance mediated by constitutive activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in human melanoma cells. J. Immunol. 2012;189:2110–2117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang X., Xu J., Wang H., Wu L., Yuan W., Du J., Cai S. Trichostatin A, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer SW480 and prostate cancer PC3 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;456:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wickstrom M., Dyberg C., Milosevic J., Einvik C., Calero R., Sveinbjornsson B., Sanden E., Darabi A., Siesjo P., Kool M., et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates MGMT gene expression in cancer and inhibition of Wnt signalling prevents chemoresistance. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8904. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takebe N., Miele L., Harris P.J., Jeong W., Bando H., Kahn M., Yang S.X., Ivy S.P. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: Clinical update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12:445–464. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gattinoni L., Ji Y., Restifo N.P. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in T-cell immunity and cancer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:4695–4701. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spranger S., Bao R., Gajewski T.F. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huelsken J., Vogel R., Erdmann B., Cotsarelis G., Birchmeier W. beta-Catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533–545. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huelsken J., Birchmeier W. New aspects of Wnt signaling pathways in higher vertebrates. Curr. Opin. Genetics Dev. 2001;11:547–553. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andl T., Reddy S.T., Gaddapara T., Millar S.E. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.St-Jacques B., Dassule H.R., Karavanova I., Botchkarev V.A., Li J., Danielian P.S., McMahon J.A., Lewis P.M., Paus R., McMahon A.P. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr. Biol. CB. 1998;8:1058–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chiang C., Swan R.Z., Grachtchouk M., Bolinger M., Litingtung Y., Robertson E.K., Cooper M.K., Gaffield W., Westphal H., Beachy P.A., et al. Essential role for Sonic hedgehog during hair follicle morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1999;205:1–9. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang S.H., Andl T., Grachtchouk V., Wang A., Liu J., Syu L.J., Ferris J., Wang T.S., Glick A.B., Millar S.E., et al. Pathological responses to oncogenic Hedgehog signaling in skin are dependent on canonical Wnt/beta3-catenin signaling. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1130–1135. doi: 10.1038/ng.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Akiyoshi T., Nakamura M., Koga K., Nakashima H., Yao T., Tsuneyoshi M., Tanaka M., Katano M. Gli1, downregulated in colorectal cancers, inhibits proliferation of colon cancer cells involving Wnt signalling activation. Gut. 2006;55:991–999. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Borycki A., Brown A.M., Emerson C.P., Jr. Shh and Wnt signaling pathways converge to control Gli gene activation in avian somites. Development. 2000;127:2075–2087. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Iwatsuki K., Liu H.X., Gronder A., Singer M.A., Lane T.F., Grosschedl R., Mistretta C.M., Margolskee R.F. Wnt signaling interacts with Shh to regulate taste papilla development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2253–2258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607399104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee C.S., Buttitta L.A., May N.R., Kispert A., Fan C.M. SHH-N upregulates Sfrp2 to mediate its competitive interaction with WNT1 and WNT4 in the somitic mesoderm. Development. 2000;127:109–118. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li X., Deng W., Lobo-Ruppert S.M., Ruppert J.M. Gli1 acts through Snail and E-cadherin to promote nuclear signaling by beta-catenin. Oncogene. 2007;26:4489–4498. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marcelle C., Stark M.R., Bronner-Fraser M. Coordinate actions of BMPs, Wnts, Shh and noggin mediate patterning of the dorsal somite. Development. 1997;124:3955–3963. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maeda O., Kondo M., Fujita T., Usami N., Fukui T., Shimokata K., Ando T., Goto H., Sekido Y. Enhancement of GLI1-transcriptional activity by beta-catenin in human cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2006;16:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bhatia N., Thiyagarajan S., Elcheva I., Saleem M., Dlugosz A., Mukhtar H., Spiegelman V.S. Gli2 is targeted for ubiquitination and degradation by beta-TrCP ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:19320–19326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Noubissi F.K., Elcheva I., Bhatia N., Shakoori A., Ougolkov A., Liu J., Minamoto T., Ross J., Fuchs S.Y., Spiegelman V.S. CRD-BP mediates stabilization of betaTrCP1 and c-myc mRNA in response to beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2006;441:898–901. doi: 10.1038/nature04839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mehmood K., Akhtar D., Mackedenski S., Wang C., Lee C.H. Inhibition of GLI1 Expression by Targeting the CRD-BP-GLI1 mRNA Interaction Using a Specific Oligonucleotide. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016;89:606–617. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.102434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elcheva I., Goswami S., Noubissi F.K., Spiegelman V.S. CRD-BP protects the coding region of betaTrCP1 mRNA from miR-183-mediated degradation. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Heffelfinger C., Ouyang Z., Engberg A., Leffell D.J., Hanlon A.M., Gordon P.B., Zheng W., Zhao H., Snyder M.P., Bale A.E. Correlation of Global MicroRNA Expression With Basal Cell Carcinoma Subtype. G3. 2012;2:279–286. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang X., Dinehart M.S. Triple Hedgehog Pathway Inhibition for Basal Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2017;10:47–49. doi: 10.25251/skin.1.supp.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Karabulut G.O., Kaynak P., Ozturker C., Fazil K., Ocak O.B., Taskapili M. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of large nodular basal cell carcinoma at the medial canthal area. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017;65:48–51. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_958_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schulze H.J., Cribier B., Requena L., Reifenberger J., Ferrandiz C., Garcia Diez A., Tebbs V., McRae S. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: Results from a randomized vehicle-controlled phase III study in Europe. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005;152:939–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Neville J.A., Williford P.M., Jorizzo J.L. Pilot study using topical imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of nodular basal cell carcinoma after initial treatment with curettage. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD. 2007;6:910–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arits A.H., Parren L.J., van Marion A.M., Sommer A., Frank J., Kelleners-Smeets N.W. Basal cell carcinoma and trichoepithelioma: A possible matter of confusion. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008;47(Suppl. 1):13–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jerjes W., Hamdoon Z., Abdulkareem A.A., Hopper C. Photodynamic therapy in the management of actinic keratosis: Retrospective evaluation of outcome. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2017;17:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Szeimies R.M., Ibbotson S., Murrell D.F., Rubel D., Frambach Y., de Berker D., Dummer R., Kerrouche N., Villemagne H., Excilight Study Group A clinical study comparing methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy and surgery in small superficial basal cell carcinoma (8–20 mm), with a 12-month follow-up. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV. 2008;22:1302–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dummer R., Guminski A., Gutzmer R., Dirix L., Lewis K.D., Combemale P., Herd R.M., Kaatz M., Loquai C., Stratigos A.J., et al. The 12-month analysis from Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 Treatment (BOLT): A phase II, randomized, double-blind study of sonidegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016;75:113.e5–125.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ramelyte E., Amann V.C., Dummer R. Sonidegib for the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2016;17:1963–1968. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2016.1225725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim D.J., Kim J., Spaunhurst K., Montoya J., Khodosh R., Chandra K., Fu T., Gilliam A., Molgo M., Beachy P.A., et al. Open-label, exploratory phase II trial of oral itraconazole for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:745–751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Von Hoff D.D., LoRusso P.M., Rudin C.M., Reddy J.C., Yauch R.L., Tibes R., Weiss G.J., Borad M.J., Hann C.L., Brahmer J.R., et al. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1164–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Weiss G.J., Tibes R., Blaydorn L., Jameson G., Downhour M., White E., Caro I., Von Hoff D.D. Long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of vismodegib in two patients with metastatic basal cell carcinoma and basal cell nevus syndrome. Dermatol. Rep. 2011;3:e55. doi: 10.4081/dr.2011.e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chang A.L., Oro A.E. Initial assessment of tumor regrowth after vismodegib in advanced Basal cell carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. 2012;148:1324–1325. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sharpe H.J., Pau G., Dijkgraaf G.J., Basset-Seguin N., Modrusan Z., Januario T., Tsui V., Durham A.B., Dlugosz A.A., Haverty P.M., et al. Genomic analysis of smoothened inhibitor resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hansen T.V., Hammer N.A., Nielsen J., Madsen M., Dalbaeck C., Wewer U.M., Christiansen J., Nielsen F.C. Dwarfism and impaired gut development in insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein 1-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:4448–4464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4448-4464.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ioannidis P., Kottaridi C., Dimitriadis E., Courtis N., Mahaira L., Talieri M., Giannopoulos A., Iliadis K., Papaioannou D., Nasioulas G., et al. Expression of the RNA-binding protein CRD-BP in brain and non-small cell lung tumors. Cancer Lett. 2004;209:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Leeds P., Kren B.T., Boylan J.M., Betz N.A., Steer C.J., Gruppuso P.A., Ross J. Developmental regulation of CRD-BP, an RNA-binding protein that stabilizes c-myc mRNA in vitro. Oncogene. 1997;14:1279–1286. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Doyle G.A., Betz N.A., Leeds P.F., Fleisig A.J., Prokipcak R.D., Ross J. The c-myc coding region determinant-binding protein: A member of a family of KH domain RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5036–5044. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ioannidis P., Mahaira L., Papadopoulou A., Teixeira M.R., Heim S., Andersen J.A., Evangelou E., Dafni U., Pandis N., Trangas T. 8q24 Copy number gains and expression of the c-myc mRNA stabilizing protein CRD-BP in primary breast carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;104:54–59. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ioannidis P., Trangas T., Dimitriadis E., Samiotaki M., Kyriazoglou I., Tsiapalis C.M., Kittas C., Agnantis N., Nielsen F.C., Nielsen J., et al. C-MYC and IGF-II mRNA-binding protein (CRD-BP/IMP-1) in benign and malignant mesenchymal tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;94:480–484. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ross J., Lemm I., Berberet B. Overexpression of an mRNA-binding protein in human colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:6544–6550. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gu L., Shigemasa K., Ohama K. Increased expression of IGF II mRNA-binding protein 1 mRNA is associated with an advanced clinical stage and poor prognosis in patients with ovarian cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2004;24:671–678. doi: 10.3892/ijo.24.3.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Prokipcak R.D., Herrick D.J., Ross J. Purification and properties of a protein that binds to the C-terminal coding region of human c-myc mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9261–9269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sparanese D., Lee C.H. CRD-BP shields c-myc and MDR-1 RNA from endonucleolytic attack by a mammalian endoribonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1209–1221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.King D.T., Barnes M., Thomsen D., Lee C.H. Assessing specific oligonucleotides and small molecule antibiotics for the ability to inhibit the CRD-BP-CD44 RNA interaction. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Faye M.D., Beug S.T., Graber T.E., Earl N., Xiang X., Wild B., Langlois S., Michaud J., Cowan K.N., Korneluk R.G., et al. IGF2BP1 controls cell death and drug resistance in rhabdomyosarcomas by regulating translation of cIAP1. Oncogene. 2015;34:1532–1541. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]