Abstract

Despite the recent growth of mindfulness research worldwide, there remains little research examining the application of mindfulness-based interventions in resource-limited, international settings. This study examined the application of Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) for HIV-infected individuals in South Africa, where rates of HIV are highest in the world. Mixed methods were used to examine the following over a three-month follow up: (1) feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary adaptation of MBSR for this new context; and (2) effects of MBSR on immune functioning, self-reported mindfulness (MAAS, FFMQ), depression, anxiety, and stress (DASS-21). Ten individuals initiated MBSR, and seven completed all eight sessions. Results indicated medium effect size improvements in immune functioning (CD4 count and t-cell count; d = .5) through the three-month follow up, though the small sample size limited power to detect a statistically significant effect. From baseline to post-treatment, improvements in “Observing” and “Non-reactivity” (FFMQ) approached statistical significance with large effect sizes (observing: d = 1.5; p = .08; non-reactivity: d = .7; p = .07). There were no statistically significant changes in depression, anxiety, or stress throughout the study period. Primary areas for adaptation of MBSR included emphasis on informal practice, ways to create “space” without much privacy, and ways to concretize the concepts and definitions of mindfulness. Feedback from participants can shape future adaptations to MBSR for this and similar populations. Findings provide preliminary evidence regarding the implementation of MBSR for individuals living with HIV in South Africa. A future randomized clinical trial with a larger sample size is warranted.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Immune Functioning, HIV, Global Mental Health

Introduction

South Africa has the highest number of HIV-infected individuals compared to any other country in the world (UNAIDS, 2014), with over six million individuals living with HIV. More than 10% of the South African population is infected with HIV, with the majority of infected adults being between the ages of 20 and 50 (AVERT, 2013). Individuals with HIV have a compromised immune system and are at risk for opportunistic infections; in lower socio-economic areas, infections such as tuberculosis (TB) are particularly common, resulting in a high rates of HIV and TB comorbidity (Hoffmann & Kamps, 2007). Comorbid psychiatric disorders also are prevalent among individuals living with HIV, more generally and in South Africa specifically, with depression and anxiety disorders being the most prevalent (Brandt, 2009; Olagunju, Ogundipe, Erinfolami, Akinbode, & Adeyemi, 2013; Olley, Zeier, Seedat, & Stein, 2005). Further, psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety, and psychological stress more broadly may worsen immune functioning and accelerate disease progression among individuals living with HIV (Antoni, 2003).

An established evidence base exists for cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM) to address stress among individuals living with HIV and improve immune functioning (Antoni, 2003; Brown & Vanable, 2008; Scott-Sheldon, Kalichman, Carey, & Fielder, 2008), as well as a less developed but accumulating evidence base for mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (Riley & Kalichman, 2015). Although the majority of evidence for MBSR among individuals living with HIV is based in the US (Riley & Kalichman, 2015), some preliminary work has evaluated mindfulness-based interventions for individuals living with HIV in international settings, such as Iran (Jam et al., 2010; SeyedAlinaghi et al., 2012), Canada (Gayner et al., 2012), and Spain (Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2014). The evidence base for MBSR’s effects on immune functioning among individuals living with HIV is promising, although mixed given the early stages of the literature (Riley & Kalichman, 2015). In contrast to CBSM, which focuses on changing thought content, MBSR focuses on acceptance-based strategies and observation of thoughts, as opposed to evaluating and restructuring thoughts to cope with stress (Baer, 2003). Research has suggested that greater acceptance of thoughts and feelings is associated with lower rates of depression and better quality of life among individuals living with HIV (Delaney & O’Brien, 2012) and improved HIV-related self care (Moitra, Herbert, & Forman, 2011). For individuals living with HIV in an impoverished setting with chronic exposure to stressors in one’s environment, an acceptance-based approach may be appropriate (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007; Carlson, 2012). Further, there also has been some evidence of the challenges in implementing the cognitive component of CBT in this setting (Andersen et al., 2016). However, there has been minimal research evaluating a mindfulness-based intervention in sub-Saharan Africa, where there is a generalized HIV epidemic. Important questions around both effectiveness and implementation exist when applying an intervention such as MBSR to this new setting.

This study evaluated the implementation and preliminary effectiveness of MBSR for individuals living with HIV in South Africa. Specific aims included (1) examining the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary adaptation of MBSR for this setting; and (2) evaluating changes in the following outcomes over a three-month follow up after an MBSR course: immune functioning (assessed via blood test results) and self-reported mindfulness, depression, anxiety and stress. We hypothesized that the adapted MBSR protocol would be feasible and acceptable in this setting, and that MBSR would be associated with improvements in immune functioning and mindfulness and reductions in depression, anxiety and stress over the three-month follow up.

Method

Participants

The sample inclusion criteria were the following: 1) confirmed HIV diagnosis > six months prior; 2) at least eighth grade English reading level (all assessments were administered in English, though the researcher administering assessments was fluent in English and Afrikaans, two of the official languages used in the province, and was on hand to translate where required). Exclusion criteria included: 1) active substance use disorder, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder; and 2) diagnosis of communicable diseases other than HIV (to prevent further illness and additional confounding variables). Eligibility was determined by a screening intake interview and biographical assessment (conducted by the lead researcher TM).

Seventeen individuals were screened for this study and met all inclusion criteria. Of those, 10 individuals returned to complete the baseline assessment and initiated MBSR. See Table 1 for all demographic characteristics for individuals screened who completed the baseline. Of all individuals assessed for screening (n = 17), only 5.8% (n = 1) had heard of mindfulness before this study. Of those who completed the baseline assessment, 50% (n = 5) had a cell phone, 30% (n = 3) could play an MP3 file on their phone or MP3 player, and 60% (n = 6) had a CD player. At baseline, 30% (n = 3) of the 10 individuals assessed were employed, and 50% (n = 5) were not prescribed ARVs.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | Screening (n=17) | Baseline (n=10) | Three-Month Follow Up (n=5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 94% | 100% | 100% |

| Male | 6% | 0% | 0% |

| Language | |||

| Afrikaans | 47% | 60% | 40% |

| English | 18% | 20% | 40% |

| Xhosa | 35% | 20% | 20% |

| Age | |||

| 20–29 years | 29% | 20% | 40% |

| 30–39 years | 47% | 50% | 60% |

| 40–49 years | 18% | 20% | 0% |

| 50+ | 6% | 10% | 0% |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 6% | 10% | 0% |

| Grade 10 | 70% | 50% | 60% |

| Grade 12 | 18% | 30% | 20% |

| Diploma | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Undergraduate | 6% | 10% | 20% |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 24% | 30% | 40% |

| Unemployed | 76% | 70% | 60% |

| Income | |||

| <ZAR1 500,00 | 82% | 80% | 60% |

| ZAR1 501 – 3 000 | 6% | 10% | 20% |

| ZAR3 001 – 5 000 | 6% | 0% | 0% |

| ZAR5 001 – 7 500 | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| ZAR7 501 – 10 000 | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| >ZAR10 000 | 6% | 10% | 20% |

Note. 1USD=~13ZAR at the time of the study.

Procedure

This study used an open-label, hybrid effectiveness-implementation pilot trial design (Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne, & Stetler, 2012) to examine the application of MBSR in an HIV positive population in a resource-limited international setting with the highest prevalence rate of HIV in the world. We used mixed methods to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary adaptation of MBSR for this new context and the effects of MBSR on immune functioning, self-reported mindfulness, depression, anxiety and stress. Permission to conduct this study was received from the the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Research Ethics Committee and the Nelson Mandela Bay Health District

Prior to recruitment, the lead researcher (TM) had meetings with local community leaders to discuss the nature of the research and inclusion criteria. Potential participants were provided the contact information of the lead researcher; if interested in participating, individuals were instructed to contact the researcher. If someone preferred the researcher to contact him/her, he/she signed a written consent authorizing the organization to provide the researcher with the contact details. When the potential participant made contact with the researcher, he/she was given a clear outline of what the research entailed and ethical considerations. Individual sessions with potential participants were arranged to conduct screening and determine eligibility. Individuals who met inclusion criteria provided written informed consent, and if interested, were enrolled in the study. Baseline questionnaires were administered prior to the start of the eight-week MBSR group.

MBSR course

The participants then participated in an eight-week MBSR course, which consisted of eight weekly sessions of two hours as well as one day of approximately six hours for a retreat (seventh week). The course followed the established MBSR protocol (Kabat-Zinn, 2013) with iterative adaptations made for the local context (described below in “Adaptations to MBSR for local context”). The course was held at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. The course was run by an MD trained MBSR facilitator (MDK) who is registered with the Health Professionals Council of South Africa (HPCSA) and completed a formal MBSR training with Jon Kabat-Zinn and Saki Santarelli in 2005. The participants were given an MP3 player to take home with them each week to listen to the guided meditations to counter any situation where a person may not have access to an audio player. At the end of the course, they were given the MP3 player to keep, but they were not made aware of this at the beginning of the course, so it could not be seen as an incentive to continue participating in the course. If the participants’ MP3 player was reported lost or stolen, an alternative arrangement was made so that they had access to the mindfulness practices. Specifically, participants who lost their MP3 players were provided with a CD if they owned a CD player, or the MP3 audio file could be loaded on to the participants’ phones. If participants did not have access to transport to get to the course, transport was reimbursed, so that there was no cost associated with participating in the research. There was no financial compensation for attending the course.

Adaptations to MBSR for local context

We did not want to assume uniform adaptations a priori and rather wanted to use the interactions during the initial application of mindfulness in this setting to observe the cultural factors that may require adaptation (Edwards, 2016). Throughout the course, we did incorporate feedback and insight from running the course, which did not majorly change content or structure but rather the way in which concepts were explained and home practice formalized. One primary example for the need for adaptation was regarding language. Although participants were required to speak English to enroll in the study, for the majority, their first language was either Afrikaans or Xhosa, and there is no direct translation of the term mindfulness in either language. As a result, the term itself was discussed at length in the beginning; trying to find the descriptive words in their mother language that best defined the concept was a challenge in itself. Additionally, concepts like “self-reflection”, “intention/intentional”, “autopilot” were discussed as there are no everyday direct common language translations. Efforts were made to explain concepts in as concrete a way as possible. As one example, the facilitator summarized the main points after each group in a brief, one page, easy-to-read way for participants to take home. Additionally, minimal take home reading was assigned; rather between-session mindfulness practice was experiential and largely focused on informal mindfulness practice.

Another primary adaptation was the need to create more time in session to reflect on observations and reactions that came up over the course of the past week. The group in general lived with a high degree of day to day uncertainty, as the areas where they lived were affected by gang violence, and several of the participants experienced significant stresses and trauma during the course of the MBSR intervention. Time was made for sharing observations of feelings and emotions that participants noticed between sessions. It became more and more apparent that these discussions were very important and that time should be made to facilitate this as part of learning the MBSR strategies, as numerous exercises in the protocol, for instance, in reviewing the exercises of the calendar of positive / negative events, evoked a high degree of emotion that was described as part of the discussion around this exercise. To enable that time, and in part because the poetry was all in advanced English, we decided to reduce the emphasis on the English poetry, and instead emphasize mindful observations from lived experience. For example, one morning on the way to group, two of the participants passed a man dead on the street, not an uncommon sight in these areas. The difficulties and observations shared from this experience took the place of the poetry on that day in a very seamless way, bringing much to the surface which could be held in mindful reflection.

A third primary adaptation was that informal mindfulness practice (e.g., eating, washing) was emphasized over formal practice in between sessions because of the lack of feasibility of private space or uninterrupted time due to the tight and crowded living quarters many were facing. During session, the amount of formal practice in session was reduced in order to create more space in session for sharing of mindful observations from stressors that arose throughout the week. Every session included a formal mindfulness exercise (ranged from 20 to 45 minutes per session), followed by inquiry, observations, and questions. The sessions emphasized mindful observation in day-to-day life and identifying new ways of responding. Flexibility around amount and duration of formal practice has been an adaptation used prior when adapting MBSR for low-income, predominantly Black women with a history of trauma exposure (Dutton, Bermudez, Matas, Majid, & Mylers, 2013).

Finally, minor adaptations were also made to accommodate the resource-limited setting and needs of participants; we found that the participants often reported they did not have food available to take with their medications, so we elected to provide healthy foods during session and the full-day retreat, with a focus on mindful eating and low cost foods they could afford themselves. Providing food has also been done in prior research adapting MBSR for an underserved population (Dutton et al., 2013). Charging their phones or MP3 players was also often a barrier to formal mindfulness practice due to limited electricity, so participants could charge their devices during the MBSR sessions and retreat day. Apart from the reduced reliance on poetry and abbreviated formal practice in session to allow for greater emphasis on sharing reactions from previous weeks’ stress, and emphasizing informal vs. formal home practice, the program followed the themes and flow of traditional MBSR.

Measures

The following measures were administered at baseline, post-treatment, and three-month follow-up. Each battery of tests took about an hour in total to complete.

Demographics and clinical questionnaire

Demographic characteristics assessed included employment, age, gender, income, education, preferred language, and clinical characteristics included whether someone was prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ARVs).

Feasibility and acceptability

Feasibility and acceptability were assessed based upon participant attendance rates and individual, semi-structured interviews at post-treatment and the three-month follow up. Individual, semi-structured interviews assessed acceptability of the MBSR course, perspectives on barriers and facilitators to attending MBSR, and recommendations for future adaptation to promote feasibility. Open-ended questions probed participants’ perceived experience of the course, perceived benefits from doing the MBSR course, challenges about doing the MBSR course, and social support, including whether individuals had support from others regarding course participation and whether they would recommend it to others. Additional questions probed more details regarding mindfulness practice, including which exercises were used outside of the course and when, and plans to continue mindfulness exercises after the course. Significant life events and life changes experienced during the course and within the three months after the course were also probed to contextualize study findings. For feasibility and acceptability considerations for subsequent adaptation of MBSR, participants also reported on whether they had ever heard of mindfulness (yes/no), and whether they had any of the following at home: CD player, MP3 player, cell phone (and type of cell phone).

Blood test results

Blood tests were used to assess immune functioning, specifically to measure CD4 count and total T-cell count (separately). CD4+ T lymphocytes play an essential role in facilitating the availability and activity of specialized immune cells. In HIV, increases in CD4 count typically reflect an increase in the efficacy of the immune response and a slower HIV disease progression (Black & Slavich, 2016). Blood was drawn at baseline, post-treatment, and the three-month follow up, and sent to a local lab (Pathcare) for analysis. The results were provided directly to participants by a trained physician and study staff member. Participants then provided consent to share the results with the other members of the research team.

Depression anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21)

DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report measure, designed to assess levels of depression, anxiety and stress, with three separate subscales for each. The Depression subscale measures hopelessness, low self-esteem, and low positive affect (e.g., “I was unable to feel enthusiastic about anything”). The Anxiety subscale assesses autonomic arousal, musculoskeletal symptoms, situational anxiety and subjective experience of anxious arousal (e.g, “I felt scared without any good reason”). The Stress subscale assesses tension, agitation, and negative affect (e.g., “I find it difficult to relax”) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). For Depression, a score of 10 to 13 indicates mild depressive symptoms, 14–20 moderate, and 21 and over severe. For Anxiety, scores of 8–9 reflect mild anxiety symptoms, 10–14 moderate, and 15 and over severe. For Stress, scores 15–18 indicate mild levels of stress, 19–25 moderate, and 26 and over severe (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The DASS-21 has been used in an African context prior, including in Ghana, Tanzania and Nigeria (Kretchy, Owusu-Daaku, & Danquah, 2014; Oladiji, Akinbo, Aina, & Aiyejusunle, 2009).

Five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ)

FFMQ is a 39-item self-report scale that measures five facets of a general tendency to be mindful including: Observing, Describing, Acting with Awareness, Non-judging of inner experience and Non-Reactivity to inner experience (Baer et al., 2008). Observing refers to an individual’s ability to notice sensations and/or changes in their internal/external environment (e.g., “when I’m walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving”). Describing refers to an individual’s ability to articulate feelings, emotions, beliefs and opinions (e.g., “I’m good at finding words to describe my feelings”). Acting with Awareness refers to an individual’s ability to be conscientious about their actions without distraction (e.g., “when I do things, my mind wanders off and I’m easily distracted”). Non-judging of inner experience refers to an individual’s ability to experience what they are feeling without criticizing oneself or believing that their thoughts and feelings are wrong and should not be felt (e.g., “I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions”). Non-reactivity to inner experience refers to an individual’s ability to perceive feelings and emotions without reacting or getting lost in them (e.g., “I perceive my feelings and emotions without having to react to them”). The FFMQ has been used prior in research in South Africa (Kok, 2011).

Mindfulness attention and awareness scale (MAAS)

MAAS is a 15-item self-report measure of the state of mindfulness. It has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Example items include: “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present” and “I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past.” The community norm for this measure (based on a non-meditating community sample in the UK) is M = 4.20, SD = .69 (n = 436) (Brown & Ryan, 2003). This measure has been used in other research in South Africa (Nell, 2016).

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were examined for all quantitative study outcomes (CD4, T-cell, DASS-21, FFMQ, MAAS) at baseline, post-intervention, and three-month follow up. Paired-samples t-tests were used to examine significance of mean differences. Paired-samples t-tests were examined from baseline to post-treatment and baseline to three-month follow up separately for DASS-21, FFMQ, and MAAS outcomes to examine changes in these measures immediately following MBSR in addition to the three-month follow up. For CD4 and T-cell counts, paired sample t-tests were conducted from baseline to three-month follow up only due to the longer anticipated time window needed to potentially detect significant changes. All analyses were also conducted using non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to account for the small sample size. However, the pattern of results did not change with the non-parametric tests. Parametric tests are therefore reported for ease of interpretation. Cohen’s d was reported as an estimate of effect size to illustrate the standardized differences between means (approximately .2 = small effect, .5 = medium effect, .8 = large effect; Cohen, 1988).

Results

Feasibility and Acceptability

Regarding treatment initiation and attendance, of the individuals who completed the baseline assessment, 100% (n = 10) initiated the MBSR course. Of the 10 initiators, 70% (n = 7) completed all eight sessions of the MBSR course. The three non-completers provided reasons for non-attendance. Two did not return after the first session and reported family difficulties as being the reason for non-attendance. One more participant dropped out prior to the end of the eight-week course, as she found employment which required her to work at the same time as the scheduled course. Of the treatment completers, 71% (n = 5) completed the three-month follow up.

Table 2 provides a summary of participant responses by question at post-treatment and three-month follow up in response to their experience of the course. All participants reported benefiting from the course and that they would recommend it to family and friends to manage stress more effectively. Regarding specific mindfulness practices, patients reported a variety of exercises that they continued to use in their everyday life, including body scan, breath awareness, mindful eating, mindful dish washing, and other examples of being more present in day-to-day experiences and emotions. One individual reported using mindfulness practices specifically to cope with painful side effects from ARVs. Successfully obtaining employment also was reported as a change from the MBSR course in three interviews and the other two indicated it helped them cope with work stress. At the three-month follow up, 100% of individuals who completed treatment (n = 5) were employed. Three participants that were unemployed at the start of the research found employment by the three-month follow up, and the remaining two participants who were employed at the start of the study remained employed. Overall being able to better respond and manage stress was another theme that came up in interviews. Regarding specific feedback about treatment structure, two individuals wanted more follow up sessions, and another indicated that out of session practice was difficult due to being busy.

Table 2.

Participant Feedback on Mindfulness Course

| Feedback Question / Item | Participant Responses |

|---|---|

| 1. How did you experience the mindfulness course? | “I experienced a lot, learned a lot. Exercise [mindful movement] helped me a lot, so when I am stressed I remember my exercise [mindful movement].” P1 “I learned a lot to control my stress levels. I recognise my anger sooner, so I can walk away” P3 “It was helpful because you were helping us manage life. It was an opportunity for me to have time for myself.” P4 “It was very worthwhile. Frequency of meeting kept it fresh in my mind–easier to do the mindful practices – dishes, driving. I did more during sessions than homework. Homework was difficult, life was busy.” P5 |

| 2. What do you think of the course now that you have finished it? | “I feel like a different person.” P1 “It was helpful – exercises…I am more mindful when eating food” P2 “I would like to still be attending – have more follow ups.” P3 “Helpful, I am starting to be more mindful of every day activities i.e. eating.” P4 “I would want to do more practice on the meeting days. Wished to have more time. Was at a basic level, would have liked to go deeper. Three months was too long a break – I hadn’t integrated it enough for it to be habit.” P5 |

| 3. Do you feel you would recommend it to your friends? How do you think they may benefit? | “Yes, it’s going to help them a lot. I am going to give my notes to my cousin” P1 “Yes, it would help them being more mindful and relax more” P2 “Yes, for stress reduction.” P3 “Certainly would recommend it to friends. Life is very stressful at the mo[ment], colleagues would benefit to get a handle on things. Also to learn to be more aware of relationship.” P4 |

| 4. Have you used any of the mindfulness skills in your life? Which ones and when? | Tai Chi, Yoga warm up exercises. I use the body scan mp3 sometimes.” P1 “Bringing awareness to the body 2/3 × per day. And mindful eating.” P2 “Yes, being more present with experience.” P3 “Yes, mindful eating; exercising [mindful movement] for pain in tummy from ARV’s; focusing mind on one task.” P4 “Mindful breathing exercise – Once a week.” P5 |

| 5. Did any part of your life change significantly during the course or within the 3 months after the course? | “I got a job”. P1 “I got a job and a boyfriend at the same time” P2 “Death of brother (suicide). Got a job as a public speaker. I was using drugs during the course – tik; because of stress of relationship. I stopped about a month ago.” P3 “I am not as frantic about things as I used to be. I try to handle things in smaller chunks – not so overwhelming. More aware of my thoughts.” P4 “No, most of my stress was at work.” P5 |

| 6. Any other thoughts you wish to discuss? | “Before the course I was in the closet. After the course I didn’t feel the shame about my status.” P1 “My family have been very supportive.” P2 “My appetite is back (3 months now). I started ARV’s two weeks ago. I remember to be mindful about 5 times per week. My relationship to life has changed, because I am now taking responsibility.” P3 “I didn’t practice after the course before the 3 month follow up. After the course I was involved in lots of conflicts with my ex, I had family staying for 4 weeks, I had a foot injury and was immobile, financial difficulties, work stress.” P4 |

| 7. What have been the benefits for you from doing the MBSR course? | “My life is very okay now since I have been doing the mindful program.” P1 “That I can relax more. How to live my life and not worry about my status.” P2a “For me being mindful. I see my life in a different way. How to eat healthy and stay healthy” P2b “It means a lot to me and I’ve learned a lot to handle stress.” P3a “I’ve learned how to control my stress levels.” P3b “I am gaining a lot and I am not emotional anymore about my family things.” P4a “More information.” P4b “Learning to not sweat the small stuff. To put challenging situations into perspective and maintain a sense of hopefulness and calmness.” P5a “Even though I haven’t been practicing, the knowledge is there and I can always pick it up again. Biggest benefit has been how to manage stress & emotions better. Also how to manage my reaction in certain circumstances.” P5b “It is a benefit because now I can think before I do something and do it mindfully.”P6a “I have managed to look at things (situations) differently – more calm, relaxed, how to handle myself.” P7a |

| 8. What has been difficult about doing the MBSR course? | “I like the course very much and I will like to do it more.” P1b “The mind thing. My mind always wonders no matter how hard I try to stay focused.” P2a “Dealing with stress. The stress part, because the stress was always there” P2b “Focusing sometimes.” P3a “It is not difficult. Also helpful to me.” P4b “Honouring attendance whilst balancing a busy work and home schedule.” P5a “Being consistent in practice when the stresses of everyday life become overwhelming.” P5b “It was difficult to focus at first but now I can focus on me and things around me.” P6a “I could not always find the time to do the practice.” P7a |

Note. All responses were from the three-month follow up except where noted that they were from post-treatment following eight-week MBSR course. Questions 1–6 were delivered as a structured interview, and 7–8 were self-report. 7–8 were administered at both post-treatment and the three-month follow up.

at end of eight week course;

at three month follow up.

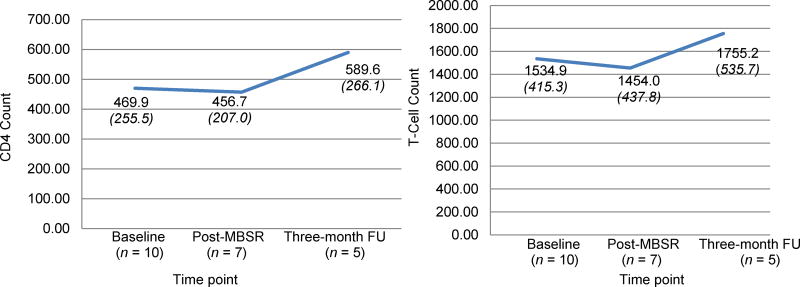

Immune Functioning (CD4 and T-cell Count)

Effect sizes indicated medium improvements in immune functioning from baseline to the three-month follow up for both CD4 count (d = .46; t(4) = −.98; p = .38) and T-cell counts (d = .46; t(4) = −.73; p = .51), though the small sample size limited power to detect a statistically significant effect. See Figure 1 for the means and standard deviations at each time point for CD4 and T-cell counts separately.

Figure 1.

Immune functioning results (CD4 and t-cell count) from baseline to three-month follow up. Means and standard deviations (SDs italicized in parentheses) are presented.

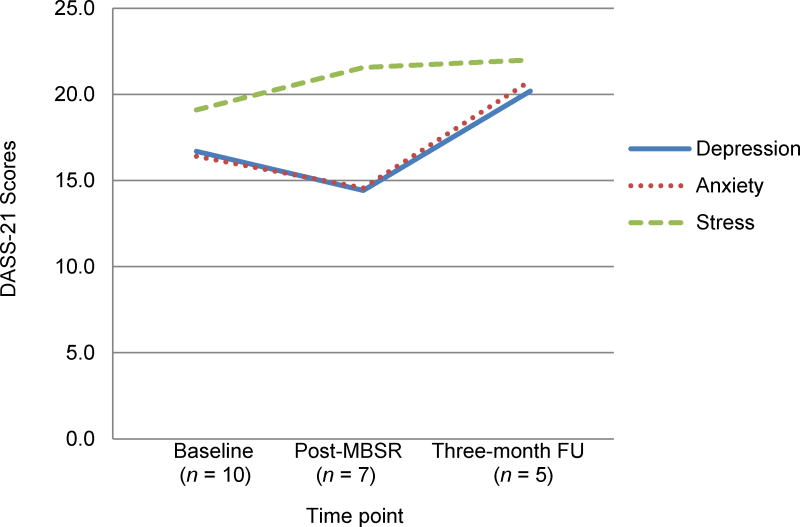

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

There were no significant changes in depression, anxiety, or stress from baseline to post-treatment or the three-month follow up period (all p’s >.2). See Figure 2 for the means and standard deviations at each time point for depression, anxiety, and stress separately. Although not a statistically significant change, depression and anxiety decreased from baseline to post-treatment, with a small effect size (Cohen’s d =.2 for both). From baseline to the three-month follow up, the improvements following MBSR did not sustain for either depression (t(4) = −1.33; p = .26) or anxiety: (t(4) = −.40; p = .71). There were no changes in stress following the MBSR course; stress remained within the moderate range throughout the study period (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), with no significant change from baseline to the three-month follow up: (d = .21; t(4) = −.56; p = .61).

Figure 2.

Depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21) scores from baseline through the three-month follow up.

Means and SDs listed here for clarity:

Depression: Baseline: M = 16.7 (8.6); Post-MBSR: 14.4 (12.8); Three-month FU: M = 20.2 (15.5).

Anxiety: Baseline: M = 16.4 (8.9); Post-MBSR: 14.6 (14.8); Three-month FU: M = 20.8 (14.7).

Stress: Baseline: M = 19.1 (9.2); Post-MBSR: 21.6 (9.8); Three-month FU: M = 22.0 (10.1).

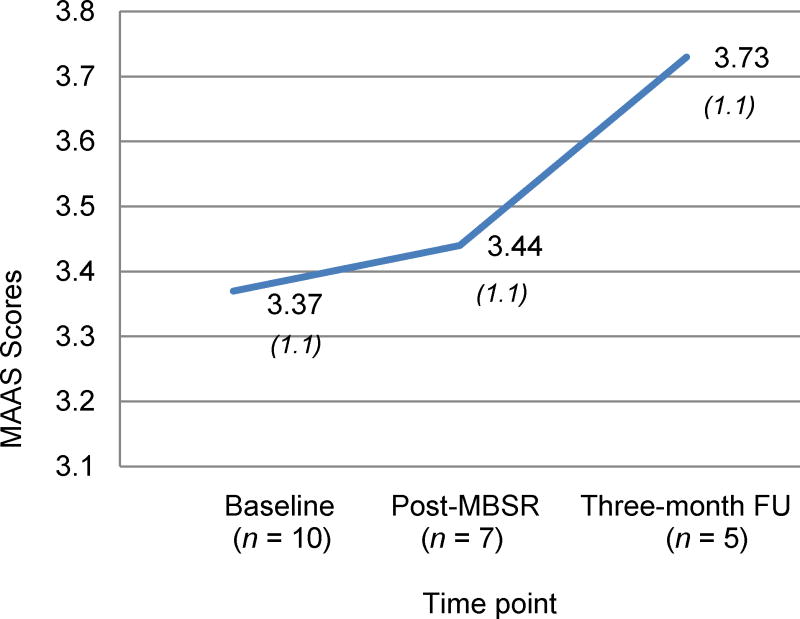

Mindfulness

As depicted in Figure 3, overall tendency to be mindful (as measured by the MAAS) increased from baseline through the three-month follow up with a small-medium effect size (Cohen’s d = .3), though the small sample size limited power to detect a statistically significant effect. MAAS scores did not significantly change from baseline to post-treatment (d = .05; t(6) = .46; p = .66).

Figure 3.

Mindfulness attention and awareness scale (MAAS) scores from baseline to the three-month follow up. Means and standard deviations (SDs italicized in parentheses) are presented.

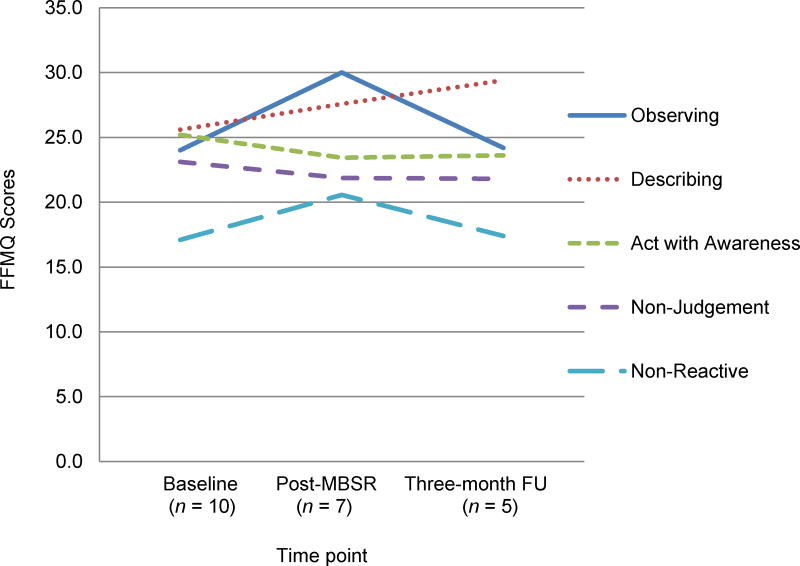

On the FFMQ, the subscales of observing, describing, and non-reactivity increased from baseline to immediately following MBSR. Though not statistically significant at p < .05, improvements in observing and nonreactivity approached statistical significance from baseline to post-treatment (observing: t(6) = −2.10; p = .08; nonreactivity: t(6) = −2.21; p = .069), with effect sizes as very large for observing (Cohen’s d = 1.5) to medium-large for non-reactivity (Cohen’s d = .7). There was also a medium-large effect size for increases in describing from baseline through the three-month follow up (Cohen’s d = .7), although this did not reach statistical significance (t(4) = −.90; p = .42). There were no significant changes in other FFMQ scales at any time point (all p’s >.3). See Figure 4 for the means and SD’s for all subscales by time point.

Figure 4.

Five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ) scores from baseline through three-month follow up.

FFMQ Means and SDs displayed here for clarity:

Observing: Baseline: M = 24.0 (3.8); Post-MBSR: 30.0 (4.0); Three-month FU: M = 24.2 (5.2).

Describing: Baseline: M = 25.6 (4.6); Post-MBSR: 27.6 (4.2); Three-month FU: M = 29.4 (5.3).

Awareness: Baseline: M = 25.2 (5.9); Post-MBSR: 23.4 (7.1); Three-month FU: M = 23.6 (4.1).

Non-Judgment: Baseline: M = 23.1 (6.3); Post-MBSR: 21.9 (3.7); Three-month FU: M = 21.8 (6.1).

Non-Reactive: Baseline: M = 17.1 (5.4); Post-MBSR: 20.6 (5.0); Three-month FU: M = 17.4 (5.7).

Discussion

This study examined the application of a MBSR among individuals living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, where the prevalence rates of HIV are the highest in the world. The focus of this research was to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and adaptation of MBSR for individuals living with HIV in an impoverished South African context, and examine preliminary effectiveness on immune functioning, levels of mindfulness, depression, anxiety and stress over a three-month follow up period. More research is needed to determine optimal strategies for implementation of MBSR (Riley & Kalichman, 2015), especially when adapting for resource-limited, cross-cultural settings (Fuchs et al., 2013). Prior research adapting mindfulness-based treatments for diverse populations has often lacked explicit considerations or justifications for adapting the approach for the specific group (Fuchs et al., 2013).

Results indicated medium effect sizes on immune functioning (both CD4 count and T-cell count) through the three-month follow up. The current study contributes to the body of information available about how MBSR may support immune functioning among HIV positive individuals in a resource-limited international setting, where rates of HIV, stress, poverty, and exposure to violence are high. For individuals living in environments where chronic psychosocial stress is high, exposure to stress may result in increases in serum cortisol levels, which in turn can have a negative impact on cell mediated immunity. Cortisol is well known as an immunosuppressant peptide, and an integral part of the negative feedback loop during an immune response. This relationship is supported by early prior research demonstrating a significant negative correlation between cortisol levels and CD4+ T lymphocytes (Wiedenfeld et al., 1990). Our findings of the medium effect sizes of MBSR on immune functioning are consistent with prior evidence from other settings. In the US, Creswell et al. (2009) found that MBSR buffered CD4 count decline (compared to a one-day seminar control). Our findings are consistent with two studies from Iran that showed increases in CD4 count following MBSR: a small, single group pilot study (Jam et al., 2010) and a larger randomized clinical trial (SeyedAlinaghi et al., 2012). SeyedAlinaghi et al. 2012 found that CD4 count increased following MBSR through a nine-month follow up, before returning to baseline levels at one year (compared to a supportive education control).

Riley and Kalichman (2015) noted that the effects of MBSR on immune functioning may sustain beyond changes in psychological outcomes, which is consistent with our findings. In our study, depression and anxiety decreased from baseline to post-treatment only, with a small effect size (Cohen’s d = .2 for both). Stress remained within the moderate range throughout the study period. SeyedAlinaghi et al. (2012) found that CD4 count increased following MBSR up to a nine-month follow up, surpassing effects on psychological well-being that only maintained through the six-month follow up. Similarly, Jam et al. (2010) found that the significant increases in CD4 counts sustained following improvements in psychological distress, which were only evident immediately following the MBSR intervention.

More research is needed to identify treatment mechanisms for MBSR (Riley & Kalichman, 2015). Accordingly, we examined numerous facets of mindfulness at post-treatment and three-month follow up to add to the existing literature regarding what components of mindfulness are being targeted when delivering MBSR in this context. The components of mindfulness assessed in the FFMQ that approached statistically significant improvements from baseline to post-treatment were Observing (p = .08) and Non-reactivity (p = .07), with effect sizes as very large for Observing (Cohen’s d = 1.5) to medium-large for Non-reactivity (Cohen’s d = .7). Only the Describing subscale continued to improve through the three-month follow up with a medium-large effect size (Cohen’s d = .7), although this was not a statistically significant change. When comparing this sample’s FFMQ scores to a community norm (a non-meditating community sample of adults in the UK; Baer et al., 2008), this sample was at or above the community norm for each subscale, with the exception of Non-reactivity (baseline was just below community norm). For the subscales that showed increases in this study, this sample scored higher than the community norm (Observing and Non-reactivity at post-treatment, and Describe at the three-month follow up). These findings suggest that the MBSR intervention increased one’s ability to observe their own experience without reacting to them through the duration of the intervention, and that the skills that sustained following the intervention were one’s ability to articulate and label what they observed in their experience. These findings are consistent with a prior study applying MBSR to individuals living with HIV in Canada (Gayner et al., 2012) that found MBSR was most helpful in increasing similar aspects of mindfulness (i.e., curiosity, decentering). Further, secondarily, they found that these increases in mindfulness were significantly correlated with reductions in avoidance and increases in positive affect evident at the six-month follow up (Gayner et al., 2012). Additional research is needed to identify potential psychological mechanisms of MBSR on both psychological outcomes and health outcomes, including immune functioning (Riley & Kalichman, 2015).

This study also provides important information about the challenges of providing mindfulness cross-culturally in a resource-limited, international setting. These findings build on prior work on this topics (Fuchs et al., 2013) and approached adaptation with a focus on the cross-cultural clinical application and interactions as an opportunity for iterative adaptation (Edwards, 2016). The primary adaptations to MBSR for this context were: (1) clarifying language and explanation of mindfulness concepts that did not have a direct translation in one’s mother tongue; (2) emphasizing informal mindfulness practice over formal practice due to feasibility concerns at home in often tight and overcrowded living arrangements; and (3) creating more space in session to share mindful observations from lived experiences week to week largely by reducing reliance on poetry. Several of the participants experienced significant stresses and trauma during the course of the MBSR intervention, and it became apparent to the facilitator that space to share observations throughout the week and in reaction to exercises was important to the process of learning MBSR in this setting. In the program, there was a constant balance between keeping fidelity with the MBSR program and creating a space where individuals could “be”, and feel that their voices were being heard. Many of the women in the group described themselves voiceless in society and in their relationships. As such, we posit the MBSR group gave these individuals a space to voice their experiences and reactions in a new way. Finally, to accommodate to the needs of the participants, a few practical adaptations were made, including: 1) summarizing each week’s content in a brief, one page, easy-to-read handout; 2) assigning minimal take home reading, rather between-session mindfulness practice was experiential and largely focused on informal mindfulness practice; 3) providing healthy foods during session and at the full-day retreat, with a focus on mindful eating, due to food insecurity among many of the patients; and 4) allowing participants to charge their devices during sessions and the retreat, as charging their phones or MP3 player to listen to the mindfulness audio was also often a barrier to formal mindfulness practice due to limited electricity availability.

Regarding participant attendance, used as a primary indicator of feasibility and acceptability (Proctor et al., 2011), 70% of individuals who initiated treatment completed all eight sessions of the MBSR course (n = 7). Given the high levels of stress in this sample and chaotic environments, this represents quite a high retention rate, particularly given that financial incentives were not provided for participation. Individuals who did not complete treatment in our study provided reasons; two cited family difficulties, and the other was due to employment. It is interesting to note the increases in employment over the course of the study period. Of those who attended at least one treatment session, 30% were employed at the start of the MBSR course, whereas 100% at the three-month follow up. The prior literature examining the effects of MBSR on functional outcomes and employment have been limited (Riley & Kalichman, 2015). Although the course did not address obtaining employment per se, increased employment is a primary way in which a behavioral intervention may be cost effective. Future research in a larger sample is needed to test effects on changes in employment, what drives these changes, and a formal examination of cost effectiveness.

The semi-structured interview feedback provides important contextual information to interpret study results. From this data, one theme that emerged from discussions with participants is the high levels of ongoing stressors that they experience (e.g., unemployment, lack of financial resources, illness and death of loved ones, work pressures, family pressures). The high levels of ongoing stress were reflected in the DASS scores; stress remained high (at the moderate level) throughout the study period. Yet, despite the high levels of stress throughout the study period, there were improvements in biological indicators of improved immune functioning and stress response, as indicated by increasing CD4 and t-cell counts. These findings must be understood in the context of this impoverished, HIV endemic setting, where stress levels remain high due to numerous societal and structural factors. Further, individuals may also have an increased awareness of depression and anxiety symptoms from mindfulness practice and the MBSR course, which may influence responding on self-report measures. Yet, alongside the elevated stress levels, participation in the MBSR course still showed medium effect sizes on improved immune response, suggesting that perhaps individuals are identifying healthier ways to cope with the ongoing stress. This is in line with the prior evidence that the effects of MBSR on immune functioning may sustain beyond psychological changes (Jam et al., 2010; Riley & Kalichman, 2015; SeyedAlinaghi et al., 2012).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

As a preliminary, exploratory study, there were a number of limitations in this study, including a small sample size that may not be generalizable to the larger population of HIV-infected individuals in South Africa, and lack of a control group. Further, the small sample size limited our power to detect a statistically significant effect, which is why we also included measures of effect size for this preliminary study. We were not able to account for the varying stressors and life events over the course of the study period that may have influenced results, for instance those that were mentioned in the semi-structured interviews, including starting a new relationship, finding a job after a period of unemployment, and numerous stressors such as exposure to violence and a close family member dying. These experiences likely contributed to the participant’s immune fluctuations, thus making it more difficult to draw conclusions as to whether mindfulness specifically is influencing immune functioning. Additionally, although some participants stated that they engaged in mindfulness practices following the eight-week course, we did not verify this or measure the amount of mindfulness practice that they did. There were also some limitations in the measures used. The measures used to assess mindfulness as well as depression, anxiety and stress were all self report measures, which are susceptible to biases and rely on the participants having insight into themselves. Another issue with regard to these measures is that very little research has been done with them in South Africa, thus further work is needed to continue to validate these measures in this setting. Further limitations regarding the research measures were that they were only available in English, and for all of the research participants, English was their second language. This also meant that the sample was biased towards people that could speak a certain level of English. Finally, although we attempted to conduct a three-month follow up assessment with the individuals who dropped out of treatment, we were unable to locate these individuals at that time.

Future directions following from the current study include conducting a larger randomized clinical trial to evaluate this approach, identifying mediators of the effects of MBSR on disease progression (i.e., changes in mindfulness or coping styles; Riley & Kalichman, 2015; Witek-Janusek et al., 2008), as well as evaluating the feasibility and acceptability of a task shifting model for delivery of this approach. Sustainable and scalable delivery in this resource-limited setting will have to be led by peers, lay counselors, or perhaps nurses (Magidson et al., 2017). Future adaptations may also consider specifically focusing on ARV initiation or adherence, particularly given the low rates of ARV use in this sample. If MBSR continues to prove beneficial for this population, researchers must work with local departments of health to implement and disseminate this approach into HIV care settings.

Acknowledgments

Funding: TLM and DE received support from Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University to conduct the research project. Dr. Magidson’s time on this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health [K23DA041901]. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We would like to acknowledge Alida Sandison and Danie Venter for their assistance and support conducting this study and the research participants for participating in the 8-week mindfulness course and the study. We would like to acknowledge Christopher Funes’ review and technical support for the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee, approved by the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Research Ethics Committee and the Nelson Mandela Bay Health District, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author Contributions

TLM: Designed and executed the study under the mentorship of DE, wrote the initial draft of the paper. DE: Supervised TLM on all aspects of study design and write up. MDK: Ran the MBSR groups, oversaw adaptation for the local context, and provided critical revisions to this manuscript. JFM: Oversaw manuscript preparation and collaborated with the other authors in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

References

- Andersen LS, Magidson JF, O’Cleirigh C, Remmert JE, Kagee A, Leaver M, … Joska J. A pilot study of a nurse-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy intervention (Ziphamandla) for adherence and depression in HIV in South Africa. Journal of Health Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1359105316643375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Antoni MH. Stress management and psychoneuroimmunology in HIV infection. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8(1):40–51. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AVERT. South Africa HIV and Aids Statistics. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/south-africa.

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, … Williams JMG. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment. 2008;15(3):329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DS, Slavich GM. Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2016;1373(1):13–24. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R. The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: A systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2009;8(2):123–133. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.1.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Cognitive-behavioral stress management interventions for persons living with HIV: A review and critique of the literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(1):26–40. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9010-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(4):822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry. 2007;18(4):211–237. doi: 10.1080/10478400701598298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE. Mindfulness-based interventions for physical conditions: A narrative review evaluating levels of evidence. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:1–21. doi: 10.5402/2012/651583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney E, O’Brien WH. The association between acceptance and mental health while living with HIV. Social Work in Mental Health. 2012;10(3):253–266. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2011.649107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Bermudez D, Matas A, Majid H, Mylers NL. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for low-income, predominantly African American women with PTSD and a history of intimate partner violence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JB. Cultural intelligence for clinical social work practice. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2016;44(3):211–220. doi: 10.1007/s10615-015-0543-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs C, Lee JK, Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Using mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments with clients from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds: Clinical considerations, meta-analysis findings, and introduction to the special series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayner B, Esplen MJ, DeRoche P, Wong J, Bishop S, Kavanagh L, Butler K. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to manage affective symptoms and improve quality of life in gay men living with HIV. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35(3):272–285. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Garcia M, Ferrer MJ, Borras X, Muñoz-Moreno JA, Miranda C, Puig J, … Fumaz CR. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on the quality of life, emotional status, and CD4 cell count of patients aging with HIV infection. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(4):676–685. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0612-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann C, Kamps BS. HIV medicine. Paris: Flying Publisher; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jam S, Imani AH, Foroughi M, SeyedAlinaghi S, Koochak HE, Mohraz M. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program in Iranian HIV/AIDS patients: a pilot study. Acta Medica Iranica. 2010;48(2):101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (Revised and updated edition) New York: Bantam Books trade paperback; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kok R. Exploring mindfulness in self-injuring adolescents in a psychiatric setting. Journal of Pscyhology in Africa. 2011;21(2):185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kretchy IA, Owusu-Daaku FT, Danquah SA. Mental health in hypertension: assessing symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress on anti-hypertensive medication adherence. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson JF, Gouse H, Psaros C, Remmert JE, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA. Task shifting and delivery of behavioral medicine interventions in resource poor global settings: HIV/AIDS treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Vranceanu A, Greer J, Safren S, editors. Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Handbook of Behavioral Medicine. New York: Springer; 2017. pp. 297–320. [Google Scholar]

- Moitra E, Herbert JD, Forman EM. Acceptance-based behavior therapy to promote HIV medication adherence. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1660–1667. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.579945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nell W. Mindfulness and psychological well-being among black South African university students and their relatives. Journal of Psychology in Africa. 2016;26(6):485–490. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2016.1250419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oladiji JO, Akinbo SR, Aina OF, Aiyejusunle CB. Risk factors of post-stroke depression among stroke survivors in Lagos, Nigeria. African Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;12(1):47–51. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v12i1.30278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olagunju AT, Ogundipe OA, Erinfolami AR, Akinbode AA, Adeyemi JD. Toward the integration of comprehensive mental health services in HIV care: An assessment of psychiatric morbidity among HIV-positive individuals in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care. 2013;25(9):1193–1198. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.763892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olley BO, Zeier MD, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder among recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2005;17(5):550–557. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, … Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley KE, Kalichman S. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for people living with HIV/AIDS: Preliminary review of intervention trial methodologies and findings. Health Psychology Review. 2015;9(2):224–243. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.895928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Fielder RL. Stress management interventions for HIV+ adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, 1989 to 2006. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27(2):129–139. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SeyedAlinaghi S, Jam S, Foroughi M, Imani A, Mohraz M, Djavid GE, Black DS. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction delivered to human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients in Iran: Effects on CD4+ T lymphocyte count and medical and psychological symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74(6):620–627. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31825abfaa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. 2014 Progress Report on the Global Plan. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/documents/JC2681_2014-Global-Plan-progress_en.pdf.

- Wiedenfeld SA, O’Leary A, Bandura A, Brown S, Levine S, Raska K. Impact of perceived self-efficacy in coping with stressors on components of the immune system. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59(5):1082–1094. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, Chroniak C, Durazo-Arvizu R, Mathews HL. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2008;22(6):969–981. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]