Abstract

Background:

Prospective real-life data on the safety and effectiveness of rituximab in Chinese patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) or follicular lymphoma (FL) are limited. This real-world study aimed to evaluate long-term safety and effectiveness outcomes of rituximab plus chemotherapy (R-chemo) as first-line treatment in Chinese patients with DLBCL or FL. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation management was also investigated.

Methods:

A prospective, multicenter, single-arm, noninterventional study of previously untreated CD20-positive DLBCL or FL patients receiving first-line R-chemo treatment at 24 centers in China was conducted between January 17, 2011 and October 31, 2016. Enrolled patients underwent safety and effectiveness assessments after the last rituximab dose and were followed up for 3 years. Effectiveness endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Safety endpoints were adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, drug-related AEs, and AEs of special interest. We also reported data on the incidence of HBV reactivation.

Results:

In total, 283 previously untreated CD20-positive DLBCL and 31 FL patients from 24 centers were enrolled. Three-year PFS was 59% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 50–67%) for DLBCL patients and 46% (95% CI: 20–69%) for FL patients. For DLBCL patients, multivariate analyses showed that PFS was not associated with international prognostic index, tumor maximum diameter, HBV infection status, or number of rituximab treatment cycles, and OS was only associated with age >60 years (P < 0.05). R-chemo was well tolerated. The incidence of HBV reactivation in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive and HBsAg-negative/hepatitis B core antibody-positive patients was 13% (3/24) and 4% (3/69), respectively.

Conclusions:

R-chemo is effective and safe in real-world clinical practice as first-line treatment for DLBCL and FL in China, and that HBV reactivation during R-chemo is manageable with preventive measures and treatment.

Trial Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01340443; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01340443.

Keywords: Asian, Hematopoietic Malignancy, Hepatitis B Virus, Observational Study, Rituximab

摘要

背景:

关于利妥昔单抗治疗中国弥漫大B细胞淋巴瘤(DLBCL)和滤泡性淋巴瘤 (FL)患者的疗效与安全性的真实世界证据十分有限。本研究通过前瞻性、非干预性的多中心临床研究观察中国真实医疗环境中利妥昔单抗联合化疗(R-Chemo)作为一线方案治疗DLBCL和FL患者的长期疗效与安全性。同时一并观察R-Chemo治疗中乙肝病毒再激活的现状。

方法:

研究为前瞻性、多中心、单组的非干预性研究。2011年1月17日至2016年10月31日,纳入国内24个中心的CD20阳性初治DLBCL和FL患者。所有患者在结束最后1次利妥昔单抗治疗后再随访3年。基线收集的数据包括年龄、性别、疾病分期、国际预后指数、滤泡性淋巴瘤国际预后指数、结外侵犯、活动状态和病史等。本研究报道疗效、安全性和乙肝病毒感染的管理现状。

结果:

共有来自24个中心的CD20阳性初治的283例DLBCL患者和31例FL患者纳入本研究。DLBCL患者3年无病进展生存率为59%(95%可信区间 50%-67%);FL患者3年无病进展生存率为46%(95%可信区间 20%-69%)。R-Chemo耐受性良好。在HBsAg阳性患者中,乙肝病毒再激活率为13% (3/24);在HBsAg阴性/ HBcAb阳性患者中,乙肝病毒再激活率为4% (3/69)。

结论:

前瞻非干预性研究证实R-Chemo在中国真实医疗环境中治疗CD20阳性初治DLBCL和FL患者是有效且安全的一线方案。经过积极的预防和治疗,R-Chemo治疗中的乙肝病毒再激活可控。

INTRODUCTION

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) is the fifth most common type of cancer, accounting for 4–5% of new cancer cases and 3% of cancer-related deaths.[1] Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL) are the most common subtypes of B-cell NHL, accounting for 31% and 22% of new cases in patients from developed countries, respectively.[2] In China, DLBCL is the most common form of NHL, accounting for 40–50% of newly diagnosed cases.[3] Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is highly endemic in China compared with developed countries. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) can be detected in 25–61% of patients with DLBCL and 20–40% of those with FL.[4] Rituximab plus chemotherapy (R-chemo) is the standard first-line treatment for patients with DLBCL or FL, with several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) having demonstrated its benefits.[5,6,7,8,9,10] Reactivation of HBV is a well-established complication of R-chemo and can result in hepatic mortality and interruptions in chemotherapy.[11,12]

It is of great importance to generate real-world data to translate the outcomes of clinical trials into actual clinical practice, having important implications for oncologists treating patients with comorbidities such as HBV infection. Despite the clinical importance of rituximab in real-world clinical settings in China, prospective real-life data on the safety and effectiveness of R-chemo in patients with DLBCL or FL are limited. We therefore performed a prospective, multicenter, noninterventional study to evaluate R-chemo as first-line treatment in Chinese patients with DLBCL or FL. Interim analyses were performed 120 days after the last rituximab administration. Short-term findings showed that R-chemo was well tolerated, and the overall response rate (ORR) among patients with DLBCL was 94.2%. Furthermore, HBsAg positivity represented a poor prognostic factor for complete response (CR) rate in Chinese patients with DLBCL.[13]

In this study, we evaluated long-term safety and effectiveness outcomes of R-chemo in real-world clinical settings in Chinese patients with DLBCL or FL. HBV reactivation management was also investigated.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Jiangsu Cancer Hospital (No. 2010NL-053). This study was performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01340443).

Study design and patients

We conducted a prospective, multicenter, single-arm, noninterventional study of previously untreated CD20-positive DLBCL or FL patients receiving first-line R-chemo treatment at 24 centers in China between January 17, 2011, and October 31, 2016. Study sites were selected from practice settings geographically distributed across China. All treatment decisions were at the investigator's discretion, including individual dose, duration of R-chemo, and method and frequency of clinical assessments, in accordance with local labeling information (rituximab administered at a dose of 375 mg/m[2] body surface area, once every 3 weeks) and standard clinical practice. Enrolled patients underwent safety and effectiveness assessments after the last rituximab dose and were followed up for 3 years. Follow-up was conducted every 3 months for the first 2 years and every 6 months for the 3rd year. Data collected at baseline included age, sex, disease stage, international prognostic index (IPI), FLIPI, extranodal involvement, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG), and medical history. IPI score is an ordered categorical variable categorized as 0–1 for low risk, 2 for low-intermediate risk, 3 for intermediate-high risk, and 4–5 for high risk. FLIPI score is categorized as 0–1 for low risk, 2 for intermediate risk, and 3–5 for high risk. Baseline data, safety and treatment effectiveness, and HBV infection management were collected from the patients' medical records.

Safety and effectiveness assessments

Safety endpoints included adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), drug-related AEs (ADRs), and AEs of special interest (AESI), according to the Common Terminology Criteria for AEs (CTCAE) Version 4.0 (CTCAE v4.0).[14] Effectiveness endpoints included ORR, CR, unconfirmed CR (CRu), partial response (PR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). ORR was defined as the proportion of patients achieving CR, CRu, or PR. Treatment response was evaluated using standardized response criteria for NHL.[15] PFS was defined as the time from receiving the first dose of treatment until disease progression or death. OS was defined as the time from receiving the first dose of treatment until death from any cause. Measurements for assessment were recorded every two cycles. Computed tomography (CT) and laboratory examinations were performed in accordance with local clinical practice. The management of HBV was evaluated, including diagnostic techniques for HBV infection and liver function screening before R-chemo, monitoring of viral replication during and after R-chemo, use of antiviral prophylaxis, and HBV reactivation. HBV reactivation was defined according to the consensus definition of the Chinese Society of Hematology (Chinese Medical Association), Chinese Anti-Cancer Association, and Chinese Society of Hepatology (Chinese Medical Association).[4] For patients with active HBV infection or inactive carriers (HBsAg positive), reactivation was defined as detectable HBV DNA or ≥1 log10 of baseline or change in status from HBeAg negative to HBeAg positive. For patients with resolved hepatitis (HBsAg negative/hepatitis B core antibody [HBcAb] positive), reactivation was defined as positive HBsAg or detectable HBV DNA.[4]

Statistical analysis

We estimated that 300 patients would have the power of at least 80% to detect AEs with incidence rate no <0.54%. All DLBCL or FL patients who received ≥1 dose of R-chemo were included in the safety analysis population. Patients who received ≥1 dose of R-chemo and had undergone ≥1 tumor assessment after baseline were evaluable for effectiveness and were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics, HBV infection and replication, and use of antiviral prophylaxis. Demographic data were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Response rates were assessed by calculating percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the ITT population. Survival endpoints were analyzed with the log-rank test. We used Cox model regression to assess the effect of prognostic factors on PFS and OS in multivariate analyses in DLBCL patients. Given the limited number of patients with FL, Cox regression analysis was not performed in FL patients. Estimates of prognostic factors were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs based on the Cox regression. Two-sided statistical tests were performed with a 5% level of significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients and treatment

Overall, 314 patients were enrolled at 24 centers. One patient withdrew from the study because of a serious protocol violation, leaving 313 patients (DLBCL = 282 and FL = 31) in the safety analysis population. A total of 287 patients (DLBCL = 258 and FL = 29) were included in the ITT population. The main reason for exclusion from the ITT population was lack of tumor assessment at baseline. Of the patients who did not complete the study per protocol, 29 (9.2%) died, 66 (21.0%) were lost to follow-up, 5 (1.6%) violated the inclusion criteria, 7 (2.2%) withdrew their informed consent, and 5 (1.6%) discontinued because of AEs (except death).

The baseline characteristics of patients in the ITT population are summarized in Table 1. The ITT population of DLBCL patients included 154 (59.7%) patients aged ≤60 years, 98 (38.0%) patients aged 60–80 years, and 6 (2.3%) patients aged >80 years. One hundred and ninety-seven (77.0%) patients had a low or low-intermediate IPI risk score, and 252 (97.6%) patients had an ECOG score ≤2. The ITT population of FL patients included 21 (72.4%) patients aged ≤60 years and 8 (27.6%) patients aged 60–80 years. Among FL patients, 20 (68.9%) had a low or intermediate FLIPI risk score, and all patients had an ECOG score ≤2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the previously untreated CD20-positive DLBCL or FL patients receiving first-line R-chemo treatment

| Variables | FL (n = 29) | DLBCL (n = 258) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 10 (34.5) | 148 (57.4) |

| Age (years) | 53.3 (29.3–79.6) | 57.2 (12.8–88.4) |

| ≤60 years | 21 (72.4) | 154 (59.7) |

| 61–80 years | 8 (27.6) | 98 (38.0) |

| >80 years | 0 | 6 (2.3) |

| Stage | ||

| I | 0 | 38 (14.8) |

| II | 4 (13.8) | 86 (33.5) |

| III | 16 (55.2) | 66 (25.6) |

| IV | 9 (31.0) | 67 (26.1) |

| ECOG | ||

| 0 | 3 (10.3) | 68 (26.4) |

| 1 | 24 (82.8) | 167 (64.7) |

| 2 | 2 (6.9) | 17 (6.6) |

| 3 | 0 | 6 (2.3) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| IPI | ||

| Low risk | – | 131 (51.2) |

| Low-intermediate risk | – | 66 (25.8) |

| Intermediate-high risk | – | 43 (16.8) |

| High risk | – | 16 (6.3) |

| FLIPI | ||

| Low risk | 9 (31.0) | – |

| Intermediate risk | 11 (37.9) | – |

| High risk | 9 (31.0) | – |

| Bulky disease* | 14 (48.3) | 80 (31.0) |

| Extranodal sites ≥1 | 24 (82.8) | 151 (58.5) |

Data were shown as n (%) or median (range). –: Not applicable; ECOG: Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status; IPI: International prognostic index; FLIPI: Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index; FL: Follicular lymphoma; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Bulky disease*: Tumor maximum diameter ≥7.5 cm.

A total of 1390 R-chemo treatment courses were completed by 258 DLBCL patients, including 1284 (92.4%) rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) courses and 76 (7.6%) rituximab monotherapy courses. Among FL patients, 22 (75.9%) patients received R-CHOP and 8 (27.6%) patients received rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-CVP). The numbers of cycles of completed treatment according to risk group (categorized by IPI or FLIPI score) of DLBCL and FL patients are listed in Table 2. Fifty-seven (22.1%) DLBCL patients completed eight cycles of treatment, while 122 (88.4%) patients in the low-risk group and 63 (87.5%) in the low-intermediate risk group completed more than four treatment cycles. Thirty-four (70.0%) patients in the intermediate-high- and high-risk groups completed more than six cycles of treatment. For FL patients, approximately 90% of patients in each risk group completed more than four cycles of treatment.

Table 2.

Cycles of treatment completed by IPI or FLIPI among patients with DLBCL or FL receiving R-chemo

| Cycles of treatment completed | IPI* | FLIPI† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low-intermediate | Intermediate-high | High | Total | Low | Intermediate | High | Total | |

| <4 | 16 (11.6) | 9 (12.5) | 1 (7.1) | 4 (11.8) | 30 (11.6) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (10.3) |

| 4–5 | 41 (29.7) | 18 (25.0) | 3 (21.4) | 6 (17.7) | 68 (26.4) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (13.8) |

| 6–7 | 53 (38.4) | 33 (45.8) | 5 (35.7) | 12 (35.3) | 103 (39.9) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 9 (31.0) |

| 8+ | 28 (20.3) | 12 (16.7) | 5 (35.7) | 12 (35.3) | 57 (22.1) | 2 (22.2) | 6 (54.6) | 5 (55.6) | 13 (44.8) |

| Total | 138 | 72 | 14 | 34 | 258 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 29 |

Data were shown as n (%). *IPI used for DLBCL; †FLIPI used for FL. IPI: International prognostic index; FLIPI: Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index; FL: Follicular lymphoma; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; Chemo: Chemotherapy; R: Rituximab

Effectiveness

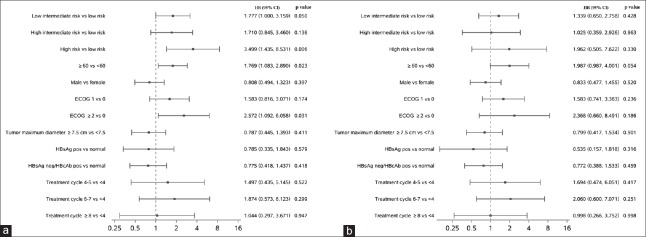

First-line R-chemo treatment in Chinese patients with DLBCL resulted in an ORR of 94.2% (CR, 55.0%; CRu, 18.2%; and PR, 20.9%). In FL patients, the ORR was 100.0% (CR, 65.5%; CRu, 10.3%; and PR, 24.1%). The median PFS was not achieved for DLBCL patients, whereas the median PFS for FL patients was 2.3 years. The 3-year PFS rate was 59% (95% CI: 50–67%) for DLBCL patients and 46% (95% CI: 20–69%) for FL patients. In univariate analyses, higher IPI score, age >60 years, and ECOG score >2 appeared to be predictive of shorter PFS in DLBCL patients [Figure 1]. PFS did not appear to be associated with tumor maximum diameter, HBV infection status, or number of rituximab treatment cycles. In multivariate analyses, PFS was not associated with any of these variables.

Figure 1.

Univariate and multivariate analyses using Cox regression for progression-free survival. (a) Univariate analysis. (b) Multivariate analysis. ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAb: Hepatitis B core antibody.

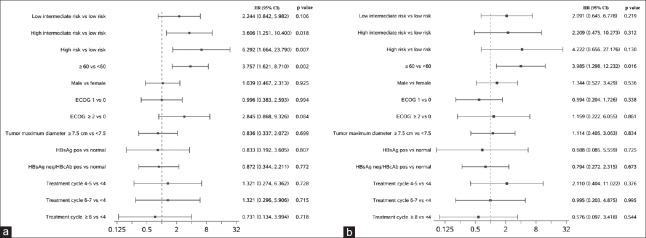

Median OS was not reached for DLBCL or FL patients in the ITT population. The 3-year OS rate was 90% (95% CI: 85–93%) in DLBCL patients and 93% (95% CI: 74–98%) in FL patients. Univariate analyses identified that higher risk (indicated by IPI score) and age >60 years appeared to be predictive factors for shorter OS in DLBCL patients [Figure 2], while tumor maximum diameter, HBV infection status, and number of rituximab treatment cycles were not associated with OS. In multivariate analyses, only age >60 years was associated with decreased OS.

Figure 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses using Cox regression for overall survival. (a) Univariate analysis. (b) Multivariate analysis. ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAb: Hepatitis B core antibody.

Safety

R-chemo was generally well tolerated as first-line treatment in patients with DLBCL or FL. The incidence of AE-related deaths was 2.1% (n = 6) and 3.2% (n = 1) for DLBCL and FL patients, respectively. Of the 282 DLBCL patients, 6 (2.1%) terminated the study and 16 (5.7%) underwent dose reductions because of AEs. Of the 31 FL patients, 1 (3.2%) terminated the study and 1 (3.2%) had a dose reduction.

The long-term and short-term reported AEs of R-chemo are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Short-term data were collected 120 days after the last rituximab dose administration, and long-term data were collected from 120 days after the last rituximab dose administration to the study end. Most AEs occurred within 120 days after the last rituximab dose administration. Of note, no SAE, AESI, or ADR was reported in FL patients from 120 days after the last rituximab dose administration to the study end. The most common AEs in the short term, after R-chemo administration, were low white blood cell count (n = 142, 50.4%), low neutrophil count (n = 61, 21.6%), and nausea (n = 52, 18.4%) in DLBCL patients. The corresponding figures were 13 (41.9%), 7 (22.6%), and 6 (19.4%) for FL patients. In the long term, the most common AE (incidence ≥5%) was low white blood cell count, which was reported in 22 (7.8%) DLBCL patients and 2 (6.5%) FL patients.

Table 3.

Summary of AEs, SAEs, AESIs, and ADRs reported during the short- and long-term treatment in patients with DLBCL receiving R-chemo (n (%))

| Safety | Short/long-term (days) | Total (n = 282) | Age (years) | IPI risk | ECOG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤60 (n = 164) | 60–80 (n = 112) | >80 (n = 6) | Low (n = 151) | Low- intermediate (n = 76) | Intermediate- high (n = 37) | High (n = 18) | >2 (n = 29) | ≤2 (n = 253) | |||

| AE (any grade) | ≤120 | 264 (93.6) | 153 (93.3) | 105 (93.8) | 6 (100) | 139 (92.1) | 73 (96.1) | 36 (97.3) | 16 (88.8) | 8 (27.6) | 253 (100) |

| >120 | 63 (22.3) | 35 (21.3) | 26 (23.2) | 2 (33.3) | 35 (23.2) | 15 (19.7) | 10 (27.2) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (3.4) | 62 (24.5) | |

| AE (grade 3–5) | ≤120 | 147 (52.1) | 76 (46.3) | 67 (59.8) | 4 (66.7) | 65 (43.0) | 45 (59.2) | 26 (70.2) | 11 (61.1) | 7 (24.1) | 140 (55.3) |

| >120 | 19 (6.7) | 10 (6.1) | 8 (7.1) | 1 (16.7) | 10 (6.6) | 3 (3.9) | 4 (10.8) | 2 (11.1) | 0 | 19 (7.5) | |

| SAE | ≤120 | 44 (15.6) | 22 (13.4) | 21 (18.8) | 1 (16.7) | 13 (8.6) | 17 (22.4) | 8 (21.6) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (13.8) | 40 (15.8) |

| >120 | 7 (2.5) | 2 (1.2) | 5 (4.5) | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (10.8) | 0 | 0 | 7 (2.8) | |

| AESI | ≤120 | 48 (17.0) | 24 (14.6) | 24 (21.4) | 0 | 23 (15.2) | 12 (15.8) | 9 (24.3) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (13.8) | 44 (17.4) |

| >120 | 4 (1.4) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 2 (5.4) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.6) | |

| ADR | ≤120 | 140 (49.7) | 78 (47.5) | 59 (52.7) | 3 (50.0) | 73 (48.3) | 40 (52.6) | 20 (54.1) | 7 (38.9) | 3 (10.3) | 137 (54.2) |

| >120 | 6 (2.1) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (3.6) | 0 | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.7) | 0 | 0 | 6 (2.4) | |

AE: Adverse event; SAE: Severe adverse event; AESI: Adverse event of special interest; ADR: Adverse drug reaction; IPI: International prognostic index; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; Chemo: Chemotherapy; R: Rituximab.

Table 4.

Summary of AEs, SAEs, AESIs, and ADRs reported during the short- and long-term treatment in patients with follicular lymphoma receiving R-chemo (n (%))

| Safety | Short/long-term (days) | Total (n = 31) | Age (years) | FLIPI risk | ECOG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤60 (n = 23) | 60–80 (n = 8) | Low (n= 11) | Intermediate (n = 11) | High (n = 9) | >2 (n = 2) | ≤2 (n = 29) | |||

| AE (any grade) | ≤120 | 28 (90.3) | 21 (91.3) | 7 (87.5) | 10 (90.9) | 11 (100) | 7 (77.8) | 0 | 28 (96.5) |

| >120 | 4 (12.9) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (22.2) | 0 | 4 (13.8) | |

| AE (grade 3–5) | ≤120 | 14 (45.2) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (27.2) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (55.5) | 0 | 14 (48.3) |

| >120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SAE | ≤120 | 4 (12.9) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (22.2) | 0 | 4 (13.8) |

| >120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AESI | ≤120 | 7 (22.6) | 4 (17.4) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (33.3) | 0 | 7 (24.1) |

| >120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ADR | ≤120 | 18 (58.1) | 12 (52.2) | 6 (75.0) | 6 (54.5) | 7 (63.6) | 5 (55.5) | 0 | 18 (62.1) |

| >120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Short-term (≤120 days): Data collected 120 days after the last rituximab dose administration; long-term (>120 days): Data collected from 120 days after the last rituximab dose administration to the study end. AE: Adverse event; SAE: Severe adverse event; AESI: Adverse event of special interest; ADR: Adverse drug reaction; Chemo: Chemotherapy; R: Rituximab; IPI: International prognostic index; FLIPI: Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index; ECOG: Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status.

Hepatitis B virus reactivation and antiviral prophylaxis

Screening for HBV infection status was performed before R-chemo treatment and defined according to HBV serological marker (HBsAg and HBcAb) positivity. In this study, HBV infection data were available for 98.9% (279/282) of DLBCL patients and 96.8% (30/31) of FL patients. Among DLBCL patients, 8.6% (24/279) were HBsAg positive, 24.7% (69/279) were HBsAg negative/HBcAb positive, 53.4% (149/279) were HBsAg/HBcAb double negative, and 14.9% (37/279) had unknown HBV infection status at baseline.

HBV reactivation was observed only in patients with DLBCL. The incidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients was 13% (3/24) and 4% (3/69), respectively. Among HBsAg-positive patients, two reactivations were observed during the first cycle of treatment, and one was observed during the eighth cycle of treatment. All three HBV reactivation cases received antiviral prophylaxis. Among HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients, two reactivations were observed during the first cycle of treatment, and one was observed during the fifth cycle of treatment. Only one of these three reactivation cases received antiviral prophylaxis. No patient died or developed hepatitis following HBV reactivation.

Among HBsAg-positive patients with DLBCL, 17/24 were monitored for HBV DNA and 17/24 received antiviral prophylaxis. For patients with HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive status, 31/69 were monitored for HBV DNA and 7/69 received antiviral prophylaxis. The time of first and last use of antiviral prophylaxis relative to rituximab treatment is shown in Table 5. For HBsAg-positive patients, antiviral prophylaxis was typically administered before the first dose of rituximab and continued after the last dose. Among the available antiviral agents, lamivudine was most commonly used to treat HBV reactivation in this study, although entecavir and adefovir dipivoxil were also used as prophylactic antiviral therapy [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 5.

Time of first and last use of HBV antiviral prophylaxis relative to rituximab treatment

| Baseline of HBV infection status | Antiviral prophylaxis | First use of antiviral prophylaxis | Last use of antiviral prophylaxis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earlier than first use of rituximab | Later than first use of rituximab | Earlier than last use of rituximab | Later than last use of rituximab | ||||||

| Number of cases | Median days | Number of cases | Median days | Number of cases | Median days | Number of cases | Median days | ||

| HBsAg+ (n = 24) | Adefovir dipivoxil | 2 | 3.5 (6, 1) | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 3 | 1113 (473, 1251) |

| Entecavir | 3 | 1 (1, 1) | 1 | 1 (1, 1) | 0 | NA | 4 | 137.5 (6, 1187) | |

| Lamivudine | 3 | 1 (1, 1) | 2 | 14.5 (2, 27) | 0 | NA | 9 | 1111 (213, 1294) | |

| HBsAg−/HBcAb+ (n = 69) | Entecavir | 0 | NA | 1 | 21 (21, 21) | 0 | NA | 1 | 1096 (1096, 1096) |

| Lamivudine | 2 | 1 (1, 1) | 2 | 69.5 (20, 119) | 0 | NA | 8 | 884 (2, 1531) | |

Median data are reported as median (range). HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAb: Hepatitis B core antibody; NA: Not applicable.

One AESI of Grade 1 pulmonary fibrosis was reported. The lower right lung of the patient showed a small amount of fibrosis.

DISCUSSION

This noninterventional study of R-chemo as first-line treatment in patients with DLBCL or FL prospectively collected data on outcomes from patients in real-life clinical practice in China. Our findings show that R-chemo is effective and safe in Chinese patients with DLBCL or FL, and that HBV reactivation during R-chemo can be controlled with appropriate preventive measures and treatment.

The efficacy and effectiveness of R-chemo as the standard first-line treatment for DLBCL patients have been widely evaluated in clinical trials and observational studies. The MabThera International Trial (MInT), which compared CHOP-like chemotherapy with and without rituximab in patients aged 18–60 years with DLBCL, reported a 3-year PFS rate with R-chemo of 85%.[6] The RiCOVER-60 study comparing six or eight cycles of CHOP-14, with or without rituximab, in patients aged 60–80 years with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas, reported a 73.4% 3-year PFS rate after six cycles of R-CHOP-14, and a 68.8% 3-year PFS rate after eight cycles.[8] In a trial including patients aged >80 years who received six cycles of rituximab combined with low-dose CHOP, a 2-year PFS of 47% was reported.[16] Due to differences in study designs and enrolled patients, PFS rates between RCTs and real-world studies are difficult to compare directly. In real-world clinical settings in China, patients tended to be younger (59.7% of patients were ≤60 years) and had low or low-intermediate prognosis risk (76.4%, as identified by IPI); however, 24% of patients had history of heart or liver diseases.[13] Our study reported a 59% 3-year PFS rate in DLBCL patients, reflecting the complex patients in real world. In real-world settings, a retrospective analysis of Japanese patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP as first-line therapy during 1996–2005 reported a 61.3% 3-year PFS rate.[17] In China, multiple, retrospective single-center studies of rituximab in DLBCL patients reported 3-year PFS rates ranging from 65% to 80%.[18,19] However, these retrospective studies may have reported higher PFS rates because of potential biases. In real-world clinical settings in China, chemotherapy treatments and the completed treatment cycles were different in patients, for instance, 92.4% of DLBCL patients received R-CHOP and 88.4% of DLBCL patients completed more than four treatment cycles. Multivariate analyses of DLBCL patients showed that the number of rituximab treatment cycles was not associated with PFS. Different chemotherapies received by patients could result in different effectiveness for DLBCL or FL. Since we aimed to demonstrate the whole picture of R-chemo as first-line treatment in real-world clinical settings, effectiveness of different chemotherapies in particular was not compared.

Consistent with several RCTs,[5,6,7,8,9,16] our findings confirmed that rituximab is generally well tolerated and safe in real-world clinical settings, as no unexpected toxicities were reported. Nevertheless, in clinical practice in China, where HBsAg may be detected among 25–61% of patients with DLBCL, the risk of HBV reactivation and the management of HBV infection during R-chemo treatment remain significant concerns. In our study, most patients with HBsAg-positive status (71%, 17/24) received HBV DNA monitoring and antiviral prophylaxis, and 13% (3/24) were identified as having HBV reactivation. Numerous studies have reported a 16–70% incidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients with lymphoma receiving R-chemo.[20] In 2015, a meta-analysis of 14 studies showed a decreased risk of HBV reactivation and hepatitis in HBsAg-positive lymphoma patients receiving prophylaxis. In addition, patients given prophylactic lamivudine had a significant reduction in overall mortality and mortality attributable to HBV reactivation compared with a control group.[21] Given the significant risk of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients, multiple clinical guidelines, including those of the CMA, recommend the screening of all patients, or patients at higher risk of HBV reactivation, for HBV infection. Furthermore, for patients with HBsAg-positive status, prophylactic antiviral therapy is preferred.[4]

Unlike the consistent recommendations for HBsAg-positive patients, the optimal management of patients with HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive status is less clear. A recent meta-analysis reported a pooled rate of 9% HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients after treatment with rituximab.[22] We found that the incidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients was 4% (3/69). Our relatively low incidence of HBV reactivation might be attributable to HBV infection status monitoring and subsequent prophylactic use. A total of 31/69 (45%) patients with HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive status was monitored for HBV DNA, and 7/69 (10%) received antiviral prophylaxis. The European Association for the Study of the Liver and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network currently favor prophylaxis in this patient population during cancer treatment.[23,24] The CMA endorses close monitoring of the HBV DNA viral load in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients receiving immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs. Those patients testing positive for HBsAg and HBV DNA should undergo antiviral prophylaxis. As observed in the present study, the maintenance of antiviral treatment after completion of antitumor therapy and long-term monitoring during the management of HBV infection are far from optimal and require adherence to local guidelines.

Our findings show that the majority of physicians in China acknowledged the importance of HBV screening and HBV DNA monitoring. However, the definition of HBV infection is inconsistent, and HBV infection monitoring and antiviral treatment remain suboptimal. Nevertheless, no patient died or developed hepatitis following HBV reactivation. These findings suggest that HBV reactivation during R-chemo can be controlled with appropriate preventive measures and treatment.

In this study, one AESI of Grade 1 pulmonary fibrosis was reported. The lower right lung of the patient showed a small amount of fibrosis, which was reported during R-chemo treatment, but this was judged by the investigator as not related to rituximab. Previous studies have reported <0.03% rituximab-related lung toxicity.[25] Pulmonary toxicity related to rituximab is rare but potentially fatal, and any patient experiencing respiratory symptoms in association with rituximab therapy should be monitored closely.

Our study is one of the few prospective evaluations of the long-term effectiveness of R-chemo in DLBCL patients in real-world settings in China to date. The prospective design of the study allowed the use of accurate definitions of AEs with closer and more systematic surveillance during the follow-up period, to provide estimates of effectiveness and safety profiles that are closest to clinical practice. Our study shows that R-chemo is an effective and well-tolerated regimen during a 3-year follow-up. Apart from its health benefits, economic evaluations of rituximab show that its use both as monotherapy and in combination with chemotherapy is a cost-effective intervention for the treatment of DLBCL or FL globally.[26] In 2016, a cost-effectiveness study of R-CHOP compared with CHOP was performed in China and concluded that R-CHOP was significantly more cost-effective than CHOP alone.[27] Taken together, R-chemo should remain part of the standard regimen for first-line treatment of DLBCL or FL in China, and additional patients are likely to further benefit with increased patient affordability of rituximab.

Some limitations should be emphasized when interpreting the results of this study. First, although a standard protocol was implemented across all participating centers, the reporting practices of physicians were not always consistent, which could have introduced bias into the results. Second, the limited numbers of FL patients may have reduced the robustness of the analyses. Additional studies in these populations are therefore required to fully establish the safety and effectiveness profiles of R-chemo in the treatment of DLBCL and FL.

In conclusion, this 3-year follow-up study indicates that R-chemo is effective and well tolerated in real-world clinical practice as first-line treatment in patients with DLBCL or FL in China. A standardized approach to the management of HBV infection, including screening, monitoring, antiviral prophylaxis, and follow-up strategies, is required in DLBCL or FL patients receiving R-chemo.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81570186) and the Health and Family Planning Commission of Jiangsu Province (No. H201511).

Conflicts of interest

This work was sponsored by Shanghai Roche Pharmaceuticals Ltd., that was involved in the study design, collection and interpretation of the data, and the writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yuan-Yuan Ji

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–11. doi: 10.1038/35000501. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang YN, Zhou XG, Zhang SH, Wang P, Zhang CH, Huang SF, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 369 B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases, with reference to the 2001 World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms (in Chinese) Chin J Pathol. 2005;34:193–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-293050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chinese Society of Hematology, CMA, Committee of Malignant Lymphoma, Chinese Anti.cancer Association, Chinese Society of Hepatology, CMA. Consensus on the management of lymphoma with HBV infection (in Chinese) Chin J Hematol. 2013;34:988–93. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2013.11.019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A, Pettengell R, Trneny M, Imrie K, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: A randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:379–91. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trümper L, Osterborg A, Trneny M, Shepherd L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1013–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70235-2. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, Schmits R, Mohren M, Lengfelder E, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: A randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:105–16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: A study by the Groupe D'etudes des Lymphomes de L'adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, Cunningham D, Flores E, Catalano J, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105:1417–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3175. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee RS, Bell CM, Singh JM, Hicks LK. Hepatitis B screening before chemotherapy: A survey of practitioners' knowledge, beliefs, and screening practices. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:325–8. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000597. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turker K, Oksuzoglu B, Balci E, Uyeturk U, Hascuhadar M. Awareness of hepatitis B virus reactivation among physicians authorized to prescribe chemotherapy. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:e90–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.07.008. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Song Y, Su L, Xu L, Chen T, Zhao Z, et al. Rituximab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment in Chinese patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in routine practice: A prospective, multicentre, non-interventional study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:537. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2523-7. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 15]. Avaialble from: https://www.evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/About.html .

- 15.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peyrade F, Jardin F, Thieblemont C, Thyss A, Emile JF, Castaigne S, et al. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:460–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70069-9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seki R, Ohshima K, Nagafuji K, Fujisaki T, Uike N, Kawano F, et al. Rituximab in combination with CHOP chemotherapy for the treatment of diffuse large B cell lymphoma in Japan: A retrospective analysis of 1,057 cases from Kyushu Lymphoma Study Group. Int J Hematol. 2010;91:258–66. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0475-2. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Wang L, Ma Y, Han T, Huang M. The enhanced international prognostic index for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Med Sci. 2017;353:459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.02.002. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong HJ, Xu PP, Zhao WL. Efficacy of additional two cycles of rituximab administration for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in first remission (in Chinese) Chin J Hematol. 2016;37:756–61. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2016.09.006. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riedell P, Carson KR. A drug safety evaluation of rituximab and risk of hepatitis B. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:977–87. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.918948. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.918948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Zhang HM, Chen LF, Chen YQ, Chen L, Ren H, et al. Prophylactic lamivudine to improve the outcome of HBsAg-positive lymphoma patients during chemotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.07.010. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Z, Li X, Wu S, Liu Y, Qiao Y, Xu D, et al. Risk of hepatitis B reactivation in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients with undetectable serum HBV DNA after treatment with rituximab for lymphoma: A meta-analysis. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:429–33. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9817-y. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9817-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelenetz AD, Wierda WG, Abramson JS, Advani RH, Andreadis CB, Bartlett N, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, version 1.2013. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:257–72. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0037. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton C, Kaczmarski R, Jan-Mohamed R. Interstitial pneumonitis related to rituximab therapy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2690–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200306263482619. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200306263482619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knight C, Maciver F. The cost-effectiveness of rituximab in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2007;7:319–26. doi: 10.1586/14737167.7.4.319. doi: 10.1586/14737167.7.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu XC, Bi C, Chen W. Cost-effectiveness of rituximab in the treatment of diffuse large b-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients (Dlbcl) in China. Value Health. 2016;19:A888. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.08.271. [Google Scholar]