Abstract

Our previous study indicated that loureirin A induces hair follicle stem cell (HFSC) differentiation through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation. However, if and how microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) modulate loureirin A-induced differentiation remains to be elucidated. In the present study, HFSCs were separated from the vibrissae of rats and identified by CD34 and keratin, type 1 cytoskeletal (K)15 expression. Microarray-based miRNA profiling analysis revealed that miR-339-5p was downregulated in loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation. miR-339-5p overexpression by transfection with miR-339-5p mimics markedly inhibited the expression of K10 and involucrin, which are markers of epidermal differentiation, whereas inhibition of miR-339-5p by miR-339-5p inhibitor transfection promoted the expression of K10 and involucrin. These results suggest that miR-339-5p is a negative regulator of HFSC differentiation following induction by loureirin A. These findings were confirmed by a luciferase assay. Homeobox protein DLX-5 (DLX5) was identified as a direct target of miR-339-5p. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that miR-339-5p inhibited DLX5. Overexpression of miR-339-5p by mimic transfection significantly inhibited protein Wnt-3a (Wnt3a) expression, while inhibition of miR-339-5p by inhibitor transfection significantly increased the expression of Wnt3a. Furthermore, small interfering RNA targeting DLX5 was transfected into HFSCs, and western blot analysis revealed that Wnt3a, involucrin and K10 expression was significantly downregulated. Taken together, these results suggest that miR-339-5p negatively regulated loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation by targeting DLX5, resulting in Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway inhibition. This may provide a possible therapeutic target for skin repair and regeneration.

Keywords: hair follicle stem cells, loureirin A, microRNA-339-5p homeobox protein DLX-5, differentiation

Introduction

Skin defects are often caused by acute and chronic disease (1). It is difficult to achieve satisfactory treatment for patients with skin defects that encompass a large area (2). With the development of skin tissue engineering, a novel method for wound healing can be provided (3). The key to tissue engineering is the choice of seed cells (4). Hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs), residing in the bulge area, are critical for epidermal regeneration in response to wounding (5). HFSCs have the unique capacity to differentiate into keratinocyte cells, hair follicles, sebaceous glands, endothelial cells and even neural lineage cells (6–9). However, the differentiation potential of HFSCs is poor in vitro and in vivo. Small molecules can be used to promote HFSC activation, which will be useful for regenerative medicine (10). Resina draconis, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine, has a long history of clinical efficacy against wounds, ulcers and other hard-to-heal injuries (11). Our previous study indicated that loureirin A, the main active flavonoid ingredient of Resina draconis, can promote HFSC differentiation by activating the protein Wnt-9b (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling pathway and inducing HFSC-seeded tissue-engineered skin to repair skin wounds (12).

Animal genomes encode hundreds of microRNA (miRNAs/miRs) genes and recent studies provide new insights into these short non-coding RNAs, by demonstrating their key roles in many biological processes, which include cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation (13,14). However, aberrant miRNA expression can lead to the development of disease (15). miRNAs are also central regulators in epidermal stem cell maintenance and wound healing (16). miR-24, miR-125b and miR-214 have unique functions in the maintenance of the hair follicle in the telogen phase, by inhibiting the transcriptional program that drives HFSC proliferation, differentiation and hair shaft assembly (17–19). miR-22 can repress homeobox proteins DLX-3 and DLX-4 expression to promote keratinocyte differentiation and hair shaft formation (20). However, it has not been determined if and how miRNAs modulate loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation.

Each miRNA can bind to numerous different mRNAs and assemble with Argonaute proteins, to form miRNA-induced silencing complexes that direct post-transcriptional silencing of complementary mRNA targets (21). miR-339-5p is a cancer-relevant miRNA that participates in various cell processes, including cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (22,23). Additionally, miR-339-5p regulates neural crest stem cell maintenance and differentiation (24). DLX5 is a transcription factor that is associated with epithelial cell differentiation (25). DLX5 positively regulates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (26), as well as signaling pathways that modulate stem cells pluripotency (27), based on Gene Ontology enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis in the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). It has also been reported that DLX5 is associated with the maintenance of pluripotent stem cells during developmental processes (28). However, it has not been well documented whether miR-339-5p targets DLX5 to regulate the differentiation of HFSCs.

In the present study, a miRNA array of HFSCs treated with loureirin A was performed. Among the differentially expressed miRNAs identified, miR-339-5p was further studied as an underlying suppressor of HFSC differentiation. Notably, DLX5 was identified as a target gene of miR-339-5p in HFSCs. The present study aimed to clarify if miR-339-5p targeted DLX5 to inhibit HFSCs differentiation via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. This may provide a potential molecular therapeutic target for the treatment of skin defects.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and identification

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (3 days old; 20±2 g; n=180) and mothers (3 months old; 300±20 g; n=5) were provided by the Laboratory Animal Centre of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (permit no. SCXK 2013-0020; Guangzhou, China). Rats were maintained in an environment with controlled humidity (50±5%), temperature (22±1°C), 12 h light/dark cycle and 0.03% CO2 conditions, with ad libitum access to milk from their mothers. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (Guangzhou, China). Male SD rats (20±2 g) were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 50 mg/kg. The rats were sacrificed by decollation and subsequently sterilized using 75% ethyl alcohol. HFSCs were isolated and cultured as previously reported, with some modifications (29). Briefly, hair follicles were separated from the vibrissae and subsequently digested with 1 g/l collagenase type I (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 min at 37°C, followed by 2.5 g/l trypsin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were cultivated with keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Primary rat HFSCs were passaged 6–7 days later.

HFSCs were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells/well. When cells reached 80% confluence, hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen CD34 and keratin, type I cytoskeletal 15 (K15) were assayed by double immunofluorescence staining. Cell samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and subsequently rinsed with PBS. Cells and nuclear membranes were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for 15 min at room temperature. Following this, cells were overlaid with 5% bovine serum albumin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed with PBS and incubated with primary antibodies against CD34 (1:100; cat no. bsm-10820M; BIOSS, Beijing, China) and K15 (1:100; cat no. bs-4762R; BIOSS) at 4°C overnight. Cells were washed with PBS and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. A0482; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and Alexa Fluor 555-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. A0453; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, cells were washed three times with PBS and counterstained with DAPI (1:1,000; cat. no. C1002; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 5 min at room temperature. Slides were observed with an Olympus IX71 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at magnification, ×100.

Treatment of HFSCs with loureirin A

Loureirin A was purchased from the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (cat. no. 200402; Beijing, China). HFSCs were seeded at a density of 5×104 cells/well in 6-well culture plates. When 80% confluence was reached, cells were treated with K-SFM containing 20 µg/ml loureirin A for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. HFSCs cultured with K-SFM only were used as a control. After 24 h, the cells were extracted for RNA extraction.

RNA extraction and microarray-based miRNA profiling analysis

Total RNA was extracted from HFSCs with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA quantity and purity was assessed using a K5500 micro-spectrophotometer. A260/A280>1.5 and A260/A230>1 indicated acceptable RNA purity and a RNA integrity number value of >7 in the Agilent 2200 RNA TapeStation system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) indicated acceptable RNA integrity. Genomic DNA contamination was evaluated by gel electrophoresis, as described previously (30). miRNA profiling was performed at Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). For advanced data analysis, all biological replicates were pooled and calculated to identify differentially expressed miRNAs based on the threshold (P<0.05). Data were analyzed by Multiexperiment Viewer 4.9.0 (http://mev.tm4.org/).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted from HFSCs using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as described above. Reverse transcription and qPCR was performed using the Prime Script™ RT reagent kit and SYBR Premix EX Taq II kit (both Takara Biotechnology, Co., Ltd., Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The thermocycling conditions used in the CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec and final extension at 60°C for 30 sec. miRNA expression was quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq method (31). The primers for miRNA were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and the sequences were as follows: miR-3589 forward, 5′-CGGAGGAAACCAGCAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; miR-347 forward, 5′-TCTCCTGTCCCTCTGGGT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; miR-203a-3p forward, 5′-CGGCGTGAAATGTTTAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; miR-339-5p forward, 5′-GTGTCCCTGTCCTCCAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; miR-3099 forward, 5′-GGCGTAGGCTAGAAAGAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; miR-6216 forward, 5′-AGCGGATACACAGAGGCA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; miR-3566 forward, 5′-TACCGGCTGCCTAACAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; U6 forward, 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACATAT-3 and reverse, 5′-TTGCGTGTCATCCTTGCG-3′.

Electrotransfection of HFSCs with miR-339-5p mimic, miR-339-5p inhibitor or small interfering (si)RNA targeting DLX5 (siDLX5)

HFSCs were collected with 0.25% trypsin digestion when cell confluence reached 80%. miRNA sequences were purchased from Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.. Cells were electrotransfected with 0.2 µg of miR-339-5p mimic (5′-UCCCUGUCCUCCAGGAGCUCACG-3′), miR-339-5p mimic negative control (NC; sequence unavailable), miR-339-5p inhibitor (5′-CGUGAGCUCCUGGAGGACAGGGA-3′), miR-339-5p inhibitor NC (sequence unavailable) or siDLX5 using a NEPA21 electroporator (Nepa Gene Co., Ltd., Ichikawa, Japan) in Opti-minimum essential media (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's electrotransfection protocol. The sequence of the siDLX5 was: 5′-GCAGCCAGCUCAAUCAAUUTT-3′ and the negative control sequence was: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′. HFSCs were seed at density of 5×105 cells/well in 6-well culture plates. After 48 h, cells were harvested for western blot and immunofluorescence analyses.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) on ice for 30 min. The supernatant for each protein group was obtained by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min and protein was quantified with the bicinchoninic acid protein assay. HFSC protein extracts (20 µg/lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to microporous polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, followed by blocking with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris buffered saline 0.01% Tween-20 at room temperature for 3 h. The blot was probed with DLX5 (1:10,000; cat. no. ab109737; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 (K10; 1:10,000; cat. no. ab76318; Abcam), involucrin (1:100; cat. no. OM174239; Omnimabs, Alhambra, CA, USA), protein Wnt-3a (Wnt3a; 1:10,000; cat. no. ab172612), β-actin (1:50,000; cat. no. ab49900) and GAPDH (1:10,000; cat. no. ab181602) primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Following this, the blot was probed by a horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (1:20,000; cat. no. ab6721; all Abcam), at room temperature for 1 h and washed with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20. Bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol and analyzed by ImageJ software version 1.4 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The relative value of the target protein was calculated by comparison with the corresponding internal reference gene for each group.

Co-transfection of HFSCs with pLUC-DLX5 and miR-339-5p mimic or inhibitor and luciferase reporter assay

HFSCs were collected and electrotransfected with 0.2 µg pLUC-DLX5 plasmid (Shenzen Huaan Pingkang Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), and subsequently electrotransfected with the miR-339-5p mimic, miR-339-5p inhibitor, or the corresponding negative controls (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.), as described above. In the pLUC-DLX5 cloning vector, miRNA target sites predicted by TargetScan software (version 7.1; http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71/) were inserted after the Renilla luciferase region. Activity was normalized to firefly luciferase activity. After 48 h, the luminescence of each well was collected and quantified with the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA).

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cells were stained on coverslips. Cell samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were subsequently stained with the anti-DLX5 antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. ab109737; Abcam) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 555-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. A0453; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were counterstained with DAPI (1:1,000) for 5 min at room temperature for nuclei visualization. Microscopic analysis was performed with a ZOE™ Fluorescent Cell Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Fluorescence intensity was measured in five viewing areas for 200–300 cells per coverslip and analyzed using ImageJ software version 1.4.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P-values were calculated using the unpaired Student's t-test, or one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni procedure. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Morphology and identification of HFSCs

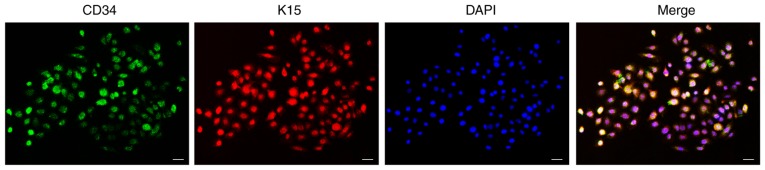

The cultured cells were cobblestone-like and exhibited the typical morphology of stem cells. Cultured cells proliferated well and were confluent after approximately 7 days. Cells stained positive for both CD34 and K15 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Morphology and identification of HFSCs. HFSCs stained positive for CD34 (green) and K15 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 25 µm. HFSC, hair follicle stem cell; CD34, hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen CD34; K15, keratin, type I cytoskeletal 15.

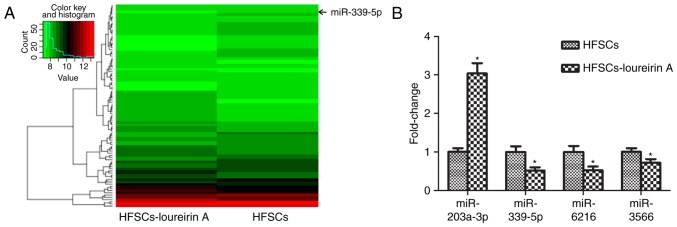

miR-339-5p is a negative regulator of loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation

The present study aimed to determine if differential miRNA expression existed in HFSCs following treatment with loureirin A. Microarray-based miRNA profiling analysis is an effective method for the prediction of the mechanisms underlying the effects of Chinese medicine monomers, including loureirin A (32). A total of 92 differentially expressed miRNAs were identified between the control and loureirin A groups. Compared with the control, 41 miRNAs were upregulated and 51 miRNAs were downregulated in the loureirin A group. Data were analyzed and a cluster diagram was created, with P<0.05 taken as the filter condition of differential gene expression (Fig. 2A). In particular, miR-203a-3p, miR-339-5p, miR-6216 and miR-3566 exhibited prominent differences; these were also confirmed with RT-qPCR (Fig. 2B). By contrast to the control group, miR-339-5p, miR-6216 and miR-3566 were down-regulated, while miR-203a-3p was upregulated. The function of miR-339-5p in HFSCs is largely unknown, so further in vitro analysis of miR-339-5p was conducted.

Figure 2.

miR-339-5p was downregulated in loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation. (A) Cluster diagram of differentially expressed miRNAs. Green indicates the degree of downregulation, while red indicates the degree of upregulation. Compared with the control group, 92 miRNAs with differential expression were identified. (B) Fold-change in relative miRNA expression in HFSCs treated with loureirin A. In the total database of the miRNA microarray, certain potential candidate miRNAs were selected and examined by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. *P<0.05 vs. control group. miRNA/miR, microRNA; HFSC, hair follicle stem cell.

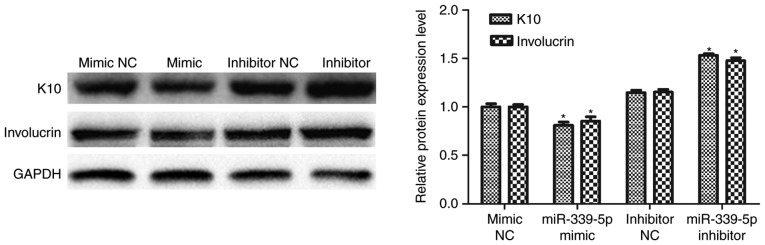

Downregulation of miR-339-5p promotes HFSC differentiation

K10 and involucrin are markers of epidermal differentiation. miR-339-5p was transfected into HFSCs and western blot analysis was performed to determine if miR-339-5p was involved in the regulation of K10 and involucrin expression. The result revealed that K10 and involucrin expression decreased in the miR-339-5p mimic group, compared with the mimic NC group and increased in the miR-339-5p inhibitor group compared with the inhibitor NC group (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

miR-339-5p was a negative regulator in loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation. K10 and involucrin expression decreased in the miR-339-5p mimic group compared with the mimic NC group, and increased in the miR-339-5p inhibitor group compared with the inhibitor NC group. *P<0.05 vs. the respective control groups. miR-339-5p, microRNA-339-5p; NC, negative control; K10, keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10.

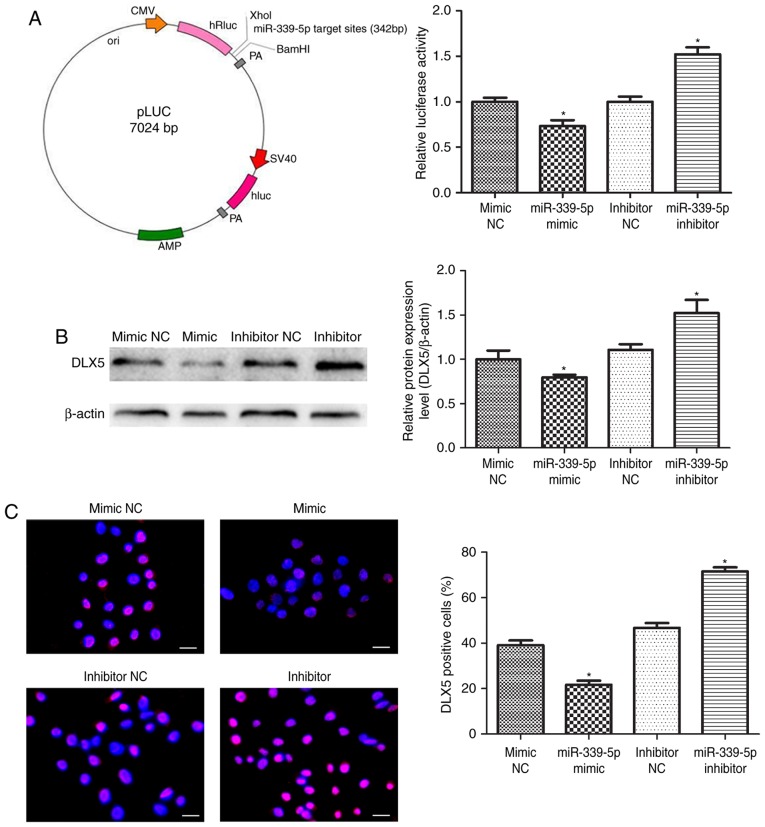

DLX5 is a potential target of miR-339-5p

HFSCs were co-transfected with the luciferase reporter carrying miR-339-5p target sites in the pLUC-DLX5 cloning vector (Fig. 4A, left), as well as the miR-339-5p mimic, miR-339-5p inhibitor or negative controls. The luciferase activity of pLUC-DLX5, containing the DLX5 3′untranslated region (UTR), was significantly reduced by the miR-339-5p mimics and markedly increased with the miR-339-5p inhibitor (Fig. 4A, right). Western blot and immunofluorescence analyses revealed that reduced endogenous DLX5 expression was due to increased miR-339-5p expression in the mimic group, and increased endogenous DLX5 expression was due to reduced miR-339-5p expression in the presence of the miR-339-5p inhibitor (Fig. 4B and C). These results suggest that miR-339-5p directly regulates the expression of DLX5.

Figure 4.

DLX5 was a direct target of miR-339-5p. (A) The construction profile of the pLUC-DLX5 vector containing the miR-339-5p target sites in DLX5 3′UTR. Relative luciferase activity of HFSCs that were co-transfected with pLUC plasmid and miR-339-5p mimic, inhibitor, or corresponding controls. (B) DLX5 expression was measured in transfected HFSCs. (C) Representative images of DLX5 immunofluorescence staining of transfected HFSCs. Red indicates DLX5 fluorescence, and blue indicates the DAPI counterstain. Scale bar, 25 µm. *P<0.05 vs. control group. DLX5, homeobox protein DLX-5; miR-339-5p, microRNA-339-5p; HFSC, hair follicle stem cells; NC, negative control.

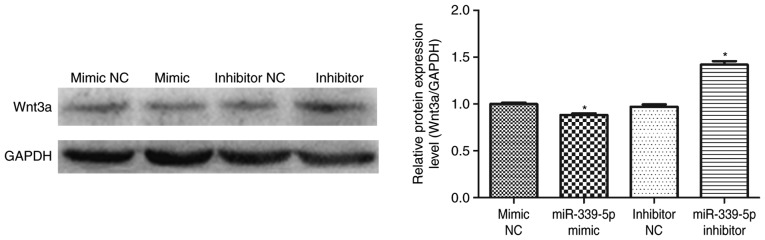

Downregulation of miR-339-5p increases Wnt3a protein expression in HFSCs

miR-339-5p was transfected into HFSCs and western blot analysis was performed to determine if miR-339-5p was involved in the regulation of Wnt3a expression. The results demonstrated that Wnt3a expression decreased in the miR-339-5p mimic group compared with the mimic NC group. Furthermore, Wnt3a levels increased in the miR-339-5p inhibitor group compared with the inhibitor NC group (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Expression of Wnt3a, the target gene of DLX5, decreased due miR-339-5p mimic transfection. Wnt3a expression increased in the miR-339-5p inhibitor group compared with the inhibitor NC group. *P<0.05 vs. control groups. DLX5, homeobox protein DLX-5; miR-339-5p, microRNA-339-5p; NC, negative control; Wnt3a, protein Wnt-3a.

Downregulation of DLX5 inhibits HFSCs differentiation

siDLX5 was transfected into HFSCs and western blot analysis was performed to determine if DLX5 was involved in the regulation of Wnt3a, involucrin and K10 expression. The results revealed that Wnt3a, involucrin and K10 expression was significantly decreased in the siDLX5 group compared with the control group (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Wnt3a, involucrin and K10 expression decreased in hair follicle stem cells transfected with siDLX5. *P<0.05 vs control group. K10, keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10; siDLX5, homeobox protein DLX-5 small interfering RNA; Wnt3a, protein Wnt-3a.

Discussion

HFSCs are located in the bulge region of the outer root sheath of the hair follicle and exhibit high proliferative and differential capacity. It is widely accepted that CD34 and K15 are markers of HFSCs (33,34). In the present study, the cultured hair follicle cells positive expression of CD34 and K15 was confirmed, indicating that the separated epithelioid cells were HFSCs. Our previous study demonstrated that HFSC-seeded tissue-engineered skin could repair full-thickness skin defects (35), and that loureirin A accelerates the healing process via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (12). However, if and how miRNAs modulate loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation remains unclear. The present study revealed that downregulation of miR-339-5p expression promoted loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation; DLX5 was a potential target of miR-339-5p; and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway may be involved in the regulatory effects of miR-339-5p/DLX5. These findings suggest that miR-339-5p and DLX5 may be key targets in drug development for wound healing.

The present study demonstrated that miR-339-5p expression downregulation promoted loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation. Microarray data and RT-qPCR analyses identified that miR-339-5p was downregulated in HFSCs induced by loureirin A. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that certain miRNAs can be differently expressed in the skin (36). A previous study indicated that miR-339-5p is involved in the development and metastasis of certain cancers (37). However, little is known about the role of miR-339-5p in HFSCs. The results of the present study demonstrate that miR-339-5p was downregulated in HFSCs treated with loureirin A. Additionally, it was revealed that the expression of K10 and involucrin decreased with miR-339-5p mimic transfection, and expression increased with miR-339-5p inhibitor transfection. Therefore, it was hypothesized that HFSC differentiation may be associated with miR-339-5p expression.

In order to further identify the function of miR-339-5p in HFSC differentiation, miR-339-5p mimics and inhibitors were transfected into HFSCs. Western blot analysis was used to detect the expression of proteins associated with HFSC differentiation. K10 and involucrin are epidermal differentiation markers (38,39). The expression of both these proteins was significantly reduced in the miR-339-5p mimic transfection group, and significantly increased in the miR-339-5p inhibitor transfected group. These data indicate that miR-339-5p may have negatively regulated the differentiation of HFSCs.

In the current study, it was revealed that DLX5 was targeted by miR-339-5p. DLX5 is a transcription factor that can modulate epithelial cell differentiation. Therefore, the focus of the present study was on DLX5. The pLUC-DLX5 cloning vector, which contained miR-339-5p target sites in the DLX5 3′UTR, was constructed to co-transfect with the miR-339-5p mimic or inhibitor. The results revealed that the luciferase activity of pLUC-DLX5 was significantly reduced by miR-339-5p mimic, and markedly increased by the miR-339-5p inhibitor. To further confirm this result, miR-339-5p mimics and inhibitor were transfected into HFSCs and DLX5 protein expression was detected by western blot and immunofluorescence analyses. DLX5 expression was significantly reduced in the miR-339-5p mimic transfection group, compared with the mimic NC group. Similarly, DLX5 expression was significantly increased in the miR-339 inhibitor transfection group, compared with the inhibitor NC group. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that DLX5 was targeted by miR-339-5p, which may be directly responsible for HFSC differentiation.

Notably, the present study demonstrated that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was involved in the regulatory effects of miR-339-5p/DLX5. Wnt3a expression significantly decreased in the miR-339-5p mimic group and significantly increased in the miR-339-5p inhibitor group. siDLX5 was transfected into HFSCs and western blot analysis revealed that Wnt3a, involucrin and K10 expression was significantly downregulated. Wnt3a, an essential component of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (40), induces the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into epidermal-like cells through activation of the classic Wnt signaling pathway (41). Furthermore, our previous results reported that loureirin A promotes HFSC differentiation by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (12). From these data, it may be hypothesized that miR-339-5p decreased HFSC differentiation by regulating DLX5 expression, resulting in Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway inhibition. However, the present study was conducted in vitro. The precise role of miR-339-5p/DLX5 in the differentiation of HFSCs must be fully elucidated in vivo.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that miR-339-5p is a negative regulator in loureirin A-induced HFSC differentiation. Downregulation of miR-339-5p expression results in increased DLX5 expression. The present study provided evidence for miR-339-5p and DLX5 as potential therapeutic molecular targets for the treatment of skin wounds.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- miR-339-5p

microRNA-339-5p

- HFSCs

hair follicle stem cells

- DLX5

homeobox protein DLX-5

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- K10

keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10

- K15

keratin, type I cytoskeletal 15

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2017A030312009) and the Educational Commission of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2016KTSCX020).

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

DC and AL conceptualized and developed the study design. XL, YW and FX performed most of the experiments. FZ and SZ prepared the cells for experimentation. JZ participated in western blot and immunofluorescence assays. FZ, SZ and JZ acquired and analyzed the data. XL, FZ, SZ and JZ discussed the results and wrote the manuscript. DC and AL made comments, suggested appropriate modifications and made corrections. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Yeh DD, Nazarian RM, Demetri L, Mesar T, Dijkink S, Larentzakis A, Velmahos G, Sadik KW. Histopathological assessment of OASIS Ultra on critical-sized wound healing: A pilot study. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:523–529. doi: 10.1111/cup.12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmann-Fritsch F, Marino D, Reichmann E. About ATMPs, SOPs and GMP: The hurdles to produce novel skin grafts for clinical use. Transfus Med Hemothr. 2016;43:344–352. doi: 10.1159/000447645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirsch T, Rothoeft T, Teig N, Bauer JW, Pellegrini G, De Rosa L, Scaglione D, Reichelt J, Klausegger A, Kneisz D, et al. Regeneration of the entire human epidermis using transgenic stem cells. Nature. 2017;551:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature24487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y, Zhang W, Li Y, Fang G, Zhang K. Scalded skin of rat treated by using fibrin glue combined with allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:289–295. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strong AL, Neumeister MW, Levi B. Stem cells and tissue engineering regeneration of the skin. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:635–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veijouyeh Joulai S, Mashayekhi F, Yari A, Heidari F, Sajedi F, Ghoroghi Moghani F, Nobakht M. In vitro induction effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on differentiation of hair follicle stem cell into keratinocyte. Biomed J. 2017;40:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Zhao H, Qiao J, Zhang S, Liu S, Li N, Lei X, Ning L, Cao Y, Duan E. Expansion of hair follicle stem cells sticking to isolated sebaceous glands to generate in vivo epidermal structures. Cell Transplant. 2016;25:2071–2082. doi: 10.3727/096368916X691989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quan R, Du W, Zheng X, Xu S, Li Q, Ji X, Wu X, Shao R, Yang D. VEGF165 induces differentiation of hair follicle stem cells into endothelial cells and plays a role in in vivo angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:1593–1604. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najafzadeh N, Sagha M, Tajaddod Heydari S, Golmohammadi MG, Oskoui Massahi N, Moghaddam Deldadeh M. In vitro neural differentiation of CD34+ stem cell populations in hair follicles by three different neural induction protocols. In Vitro Cell Develop Biol-Anim. 2015;51:192–203. doi: 10.1007/s11626-014-9818-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores A, Schell J, Krall AS, Jelinek D, Miranda M, Grigorian M, Braas D, White AC, Zhou JL, Graham NA, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase activity drives hair follicle stem cell activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:1017–1026. doi: 10.1038/ncb3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Xiong T, Yang Y, Li J, Mao J. Resina draconis as a topical treatment for pressure ulcers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:565–574. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu A, Du B, Yi H, Tang Y, Li X, Zhang S, Zhou J, Chen D. Loureirin A activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway to promote wound with follicle stem cell-seeded tissue-engineered skin healing. J Biomater Tiss Eng. 2016;6:427–432. doi: 10.1166/jbt.2016.1467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandra S, Vimal D, Sharma D, Rai V, Gupta SC, Chowdhuri DK. Role of miRNAs in development and disease: Lessons learnt from small organisms. Life Sci. 2017;185:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Rao SS, Wang ZX, Cao J, Tan YJ, Luo J, Li HM, Zhang WS, Chen CY, Xie H. Exosomes from human umbilical cord blood accelerate cutaneous wound healing through miR-21-3p-mediated promotion of angiogenesis and fibroblast function. Theranostics. 2018;8:169–184. doi: 10.7150/thno.21234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reza AMMT, Choi YJ, Kim JH. MicroRNA and transcriptomic profiling showed miRNA-dependent impairment of systemic regulation and synthesis of biomolecules in rag2 ko mice. Molecules. 2018;23:E527. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ojeh N, Pastar I, Tomic-Canic M, Stojadinovic O. Stem cells in skin regeneration, wound healing, and their clinical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:25476–25501. doi: 10.3390/ijms161025476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amelio I, Lena AM, Bonanno E, Melino G, Candi E. miR-24 affects hair follicle morphogenesis targeting Tcf-3. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e922. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Ge Y, Fuchs E. miR-125b can enhance skin tumor initiation and promote malignant progression by repressing differentiation and prolonging cell survival. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2532–2546. doi: 10.1101/gad.248377.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed MI, Alam M, Emelianov VU, Poterlowicz K, Patel A, Sharov AA, Mardaryev AN, Botchkareva NV. MicroRNA-214 controls skin and hair follicle development by modulating the activity of the Wnt pathway. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:549–567. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan S, Li F, Meng Q, Zhao Y, Chen L, Zhang H, Xue L, Zhang X, Lengner C, Yu Z. Post-transcriptional regulation of keratinocyte progenitor cell expansion, differentiation and hair follicle regression by miR-22. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonas S, Izaurralde E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:421–433. doi: 10.1038/nrg3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansson MD, Damas ND, Lees M, Jacobsen A, Lund AH. miR-339-5p regulates the p53 tumor-suppressor pathway by targeting MDM2. Oncogene. 2015;34:1908–1918. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou C, Liu G, Wang L, Lu Y, Yuan L, Zheng L, Chen F, Peng F, Li X. MiR-339-5p regulates the growth, colony formation and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells by targeting PRL-1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichi S, Costa FF, Bischof JM, Nakazaki H, Shen YW, Boshnjaku V, Sharma S, Mania-Farnell B, McLone DG, Tomita T, et al. Folic acid remodels chromatin on Hes1 and Neurog2 promoters during caudal neural tube development. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36922–36932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu B, Wang Q, Wang YA, Hua S, Sauvé CG, Ong D, Lan ZD, Chang Q, Ho YW, Monasterio MM, et al. Epigenetic activation of WNT5A drives glioblastoma stem cell differentiation and invasive growth. Cell. 2016;167:1281–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rakowiecki S, Epstein DJ. Divergent roles for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in epithelial maintenance and breakdown during semicircular canal formation. Development. 2013;140:1730–1739. doi: 10.1242/dev.092882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babaie Y, Herwig R, Greber B, Brink TC, Wruck W, Groth D, Lehrach H, Burdon T, Adjaye J. Analysis of Oct4-dependent transcriptional networks regulating self-renewal and pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:500–510. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfrum K, Wang Y, Prigione A, Sperling K, Lehrach H, Adjaye J. The LARGE principle of cellular reprogramming: Lost, acquired and retained gene expression in foreskin and amniotic fluid-derived human iPS cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang E, Lian X, Chen W, Yang T, Yang L. Characterization of rat hair follicle stem cells selected by vario magnetic activated cell sorting system. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2009;42:129–136. doi: 10.1267/ahc.09016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang G, Zhao T, Wang L, Hu B, Darabi A, Lin J, Xing MM, Qiu X. Studying different binding and intracellular delivery efficiency of ssDNA single-walled carbon nanotubes and their effects on LC3-related autophagy in renal mesangial cells via miRNA-382. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:25733–25740. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b07185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng J, Yu L, Chen W, Lu X, Fan X. Circulating exosomal microRNAs reveal the mechanism of fructus meliae toosendan-induced liver injury in mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2832. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ge W, Zhao Y, Lai FN, Liu JC, Sun YC, Wang JJ, Cheng SF, Zhang XF, Sun LL, Li L, et al. Cutaneous applied nano-ZnO reduce the ability of hair follicle stem cells to differentiate. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11:465–474. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1310947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chacon-Martinez CA, Klose M, Niemann C, Glauche I, Wickstrom SA. Hair follicle stem cell cultures reveal self-organizing plasticity of stem cells and their progeny. EMBO J. 2017;36:151–164. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu A, Chen X, Yi H, Li F, Chen D. Accelerating the healing of skin defects transplanted FSC-seeded tissue-engineered skin. J Biomater Tiss Eng. 2015;5:574–578. doi: 10.1166/jbt.2015.1345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aberdam D, Candi E, Knight R, Melino G. miRNAs, ‘stemness’ and skin. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan H, Zhao M, Huang S, Chen P, Wu WY, Huang J, Wu ZS, Wu Q. Prolactin inhibits BCL6 expression in breast cancer cells through a microRNA-339-5p-dependent pathway. J Breast Cancer. 2016;19:26–33. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi Y, Nouri M, Martino MM, Fattahi A, Alizadeh E, Darabi M, Rahmati-Yamchi M, Zarghami N. Cytoprotection, proliferation and epidermal differentiation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells on emu oil based electrospun nanofibrous mat. Exp Cell Res. 2017;357:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sundaramurthi D, Krishnan UM, Sethuraman S. Epidermal differentiation of stem cells on poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) nanofibers. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:2589–2599. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimomura Y, Agalliu D, Vonica A, Luria V, Wajid M, Baumer A, Belli S, Petukhova L, Schinzel A, Brivanlou AH, et al. APCDD1 is a novel Wnt inhibitor mutated in hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Nature. 2010;464:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature08875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun TJ, Tao R, Han YQ, Xu G, Liu J, Han YF. Wnt3a promotes human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into epidermal-like cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The analyzed datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.