Abstract

Background

Humanitarian emergencies increase the risk of gender-based violence (GBV). We estimated the prevalence of GBV victimisation and perpetration among women and men in urban settings across Somalia, which has faced decades of war and natural disasters that have resulted in massive population displacements.

Methods

A population-based survey was conducted in 14 urban areas across Somalia between December 2014 and November 2015.

Results

A total of 2376 women and 2257 men participated in the survey. One in five men (22.2%, 95% CI 20.5 to 23.9) and one in seven (15.5%; 95% CI 14.1 to 17.0) women reported physical or sexual violence victimisation during childhood. Among women, 35.6% (95% CI 33.4 to 37.9) reported adult lifetime experiences of physical or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV) and 16.5% (95% CI 15.1 to 18.1) reported adult lifetime experience of physical or sexual non-partner violence (NPV). Almost one-third of men (31.2%; 95% CI 29.4 to 33.1) reported victimisation as an adult, the majority of which was physical violence. Twenty-two per cent (21.7%; 95% CI 19.5 to 24.1) of men reported lifetime sexual or physical IPV perpetration and 8.1% (95% CI 7.1 to 9.3) reported lifetime sexual or physical NPV perpetration. Minority clan membership, displacement, exposure to parental violence and violence during childhood were common correlates of IPV and NPV victimisation and perpetration among women and men. Victimisation and perpetration were also strongly associated with recent depression and experiences of miscarriage or stillbirth.

Conclusion

GBV is prevalent and spans all regions of Somalia. Programmes that support nurturing environments for children and provide health and psychosocial support for women and men are critical to prevent and respond to GBV.

Keywords: public health, community-based survey

Key questions.

What is already known?

In 2005, the WHO estimated that one in three women globally experience intimate or non-partner physical or sexual violence in their lifetime; however, population-based statistics from conflict affected countries are limited.

What are the new findings?

This study provides population-based estimates of gender-based violence (GBV) victimisation and perpetration among women and men in conflict-affected and non-conflict regions of Somalia.

Individual and social correlates of violence highlight strong correlations between childhood violence victimisation or witness to violence, displacement and minority status, with violence victimisation and perpetration.

Several mental and reproductive health outcomes are also associated with victimisation and perpetration of GBV.

What do the new findings imply?

Violence is not unique to conflict-affected areas and programmes to address and respond to GBV should be brought to scale in both conflict and non-conflict areas, with particular attention to displaced and minority populations.

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV), defined as violence that is perpetrated on the basis of socially ascribed gender differences, is a globally prevalent health, human rights, development and humanitarian issue.1 GBV broadly encompasses physical, sexual and psychological violence that occurs within families, in the general community or that is condoned by the state.2 Estimates produced by the WHO suggest that approximately one in three women and girls experience lifetime physical or sexual violence and imply that the prevalence of all forms of GBV is even greater.1

The issue of GBV is more pronounced in conflict-affected settings where risk of GBV is heightened. The breakdown of protection structures, disruption of family and social networks, displacement, economic disturbances and other events that are associated with conflict often create opportunities for violence that occurs within the context of conflict itself or that is opportunistic in nature.3–12 Furthermore, these situations may exacerbate underlying violence within a community, family or partnership. Studies from humanitarian settings have shown observable increases in some of the most common forms of GBV, intimate partner violence (IPV) and violence within families, which may be associated with the stress of conflict and displacement.3 4 13 14 Limited research has emerged to suggest that risk of violence victimisation is also increased for men in conflict-affected settings, with reports from several African countries and Syria documenting cases of sexual violence victimisation among men.15–18

Numerous international research investigations have highlighted the harmful effects of GBV. These range from the immediate health effects of physical and sexual violence, including injury and infection, to long-term health sequelae of substance use, depression or anxiety, poor pregnancy outcomes (eg, low birth weight) and increased rates of abortion among survivors of violence.19–22 While these health outcomes also occur in non-conflict settings, they may be exacerbated by a conflict and postconflict situations.9 There are also economic costs to the survivor as well as to the wider society associated with lost wages and productivity and increased health expenditures and costs associated with resources used in social services and justice systems.23 For developing economies, addressing GBV is a critical target for sustainable development. Much has been learnt about the population prevalence of GBV and related health outcomes through Demographic Health Surveys, but conflict-affected settings are often excluded from such population-based research.24

The three regions that lie within Somalia (Southern and Central, Puntland and Somaliland) have been affected by conflict since the 1991 government breakdown and ensuing civil war. However, the humanitarian situation that emerged has simultaneously been exacerbated by natural disasters of drought and famine. As a result of these complex issues, over half of the population is estimated to be dependent on humanitarian support.25 Research has drawn attention to the experiences of GBV among Somali refugees residing in other countries.4 26–28 However, few studies have assessed the prevalence, correlates and health outcomes of GBV within the three regions of Somalia itself. This study aimed to provide in-depth information on the prevalence, correlates and health outcomes of GBV in urban areas across the three regions.

Methods

A quantitative survey was developed to estimate the prevalence and correlates of GBV victimisation and perpetration during childhood and adulthood among men and women across the three regions of Somalia: Southern and Central Somalia, Puntland and Somaliland. Though all three regions have been affected by the conflict that emerged in 1991, there are substantial differences in the political and humanitarian contexts across the regions. Somaliland represents the northwestern region and has been a self-declared autonomous state since the conflict in 1991. Puntland, the most northeastern region of the country has been an autonomous state since 1998. The South Central region lies in the southernmost part of the country and is inclusive of the capital Mogadishu. Though all three regions are affected by drought and famine, the South Central region continues to be the most heavily affected by conflict.29 This region has the highest concentration of internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, informal settlements and active humanitarian agencies, followed by Puntland and Somaliland with the least number of IDPs and humanitarian providers. Returnees who have recently been voluntarily repatriated from Kenya also tend to resettle in the South Central region.30 The survey was conducted in 14 urban areas across the three regions between the dates of December 2014 and November 2015.

Study population

Survey research was conducted with adult male and female residents of selected households, aged 18 years and older (or 15 years and older if married or with children/pregnant) and residing in 1 of the 14 targeted urban areas. Individuals were excluded if they were foreigners, lived outside of the three regions of Somalia within the last 5 years and/or declined consent to participate.

Sampling

The study employed a population-based household survey approach across the 14 selected urban areas. These areas were selected based on accessibility, security concerns and population size. Based on 2014 population estimates, these 14 areas represent 48% of the total population.

A target sample of 4520 individuals was estimated based on detecting a prevalence of 20% with 95% CIs within ±2%). Sampling within each region was proportional to the population size and stratified by sex and age, with categorisation of those under and over 20 years of age to ensure adequate sample of youth and non-youth. Prior to sampling, discussions were held with regional authorities and community leaders to inform them of the study and obtain approval to collect study data.

Within each of the 14 sites, sampling was initiated with a randomly selected household. To identify the next household, trained research assistants (RAs) counted three houses alternating each side of the street. For situations in which there was no answer at a selected household or the residents did not match the sampling target, the RA then moved on to the next household. Once an interview was completed, the RA proceeded to the next third house. If the household member met the age and sex criteria for the RA’s quota and agreed to participate, the RA and participant found a private place/time to undergo the informed consent process and complete the interview.

Measures

The survey sought to assess the burden and typology of GBV and health outcomes from residents in their various life situations. The women’s survey consisted of five modules, including: a basic demographic module that collected information on both the participant as well as the participant’s partner for those married or in a relationship; reproductive health; experiences with partners and non-partners, which included multiple violence measures to assess violence victimisation in childhood (aged <15 years) and adulthood (aged ≥15 years); social norms related to GBV and gender equity; and health and psychosocial issues. The men’s survey was composed of the same five modules with questions appropriate to the male experience; however, victimisation items were not stratified by IPV and non-partner violence (NPV) but asked about experiences of violence and the perpetrators of physical, sexual, and psychological violence during adulthood and childhood, while additional questions were included to assess perpetration of IPV and NPV.

Demographic measures were aligned with the measures collected by the International Organization for Migration 2012 Somalia Youth Survey.11 To collect data on lifetime and recent (past 12 months) experience of IPV and NPV among men and women, measures were adapted from the revised Conflict Tactics Scale, the most widely used and validated measure of GBV globally, and the WHO multicountry study on women’s health and domestic violence against women.12 13 These measures assessed the typology of violence, including psychological, physical and sexual violence. Perpetration of IPV and NPV was measured using items adapted from the recent WHO IPV and NPV surveys conducted in East Asia.14 Measures on child abuse and harmful traditional practices, including widow inheritance and female genital mutilation, were adapted from surveys of neighbouring countries, such as the Tanzania Violence Against Children Survey, WHO FGM Multi-Country Study, and Unicef FGM survey.15-17 Additional questions were asked to understand subsequent and related social outcomes, such as experiences of stigma, access to healthcare and protection from GBV and current depression symptoms, which were measured using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) depression subscale.31 The survey underwent pilot testing, was translated to Somali and back-translated to English. During pilot testing, RAs were required to achieve a level of ≥95% inter-rater reliability on the administration of the survey in the field before they could begin data collection.

All surveys were interviewer-administered using secure, password-protected study tablets. The tablet-based surveys included logic checks and skip patterns and lasted approximate 45–60 min. Trained RAs directly entered participants’ data into the tablet, which was subsequently transferred to the study server daily when the study team returned to the office from fieldwork. On transfer, the data were automatically removed from the tablet for secure data storage. All data were anonymously collected to assure the confidentiality of respondents’ data.

Human subjects protections

All research conducted by JHU and partners was reviewed and approved by JHU Institutional Review Board and is consistent with WHO guidelines on research on sexual violence in emergencies.32 Approval from government authorities in each region was secured prior to conducting the study, including the Ministry of Women and Human Rights Development of the Federal Republic of Somalia, the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs in Somaliland and the Ministry of Women Development and Family Affairs in Puntland.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was descriptive in nature with the intent of calculating the aggregated population prevalence estimates of GBV victimisation and perpetration. Descriptive statistics were run for each typology of GBV including psychological, physical and sexual forms of IPV and NPV, as well as physical and sexual forms of violence during childhood. Because 98% of women who reported lifetime IPV also reported recent IPV within the last 12 months, our analysis focuses on all lifetime experiences of GBV. CIs were calculated with prevalence estimates, after adjusting for clustering by site.

To identify correlates of GBV outcomes, composite binary variables were created for any adult lifetime experience of physical or sexual IPV and as well as for any adult lifetime physical or sexual NPV for women. Composite variables were created for adult lifetime physical or sexual IPV perpetration and adult lifetime physical or sexual NPV perpetration among men. Because the men’s survey did not contain separate items for IPV and NPV victimisation, composite variables were created for any adult lifetime experience of violence victimisation among men. Crude and adjusted log binomial regression using sandwich estimator for robust SEs were conducted to identify correlates of the violence outcomes of interest. Prevalence ratios were calculated to estimate the magnitude of the relationships between variables of interest and the dependent variable, given the potential of ORs to overestimate the magnitude of the relationship for variables with a prevalence exceeding 10% reporting GBV outcomes.33 Variables were selected for inclusion in the model on the basis of known confounding (eg, age) or having a significant association with the GBV outcome of interest in bivariate analysis (p<0.05). Model fit was estimated using Pearson’s goodness of fit test, and variance inflation factor was implemented to assess potential collinearity of the variables.34

Finally, we assessed the relationship between violence victimisation among men and women and health outcomes including depression symptomatology and miscarriage and abortion in pregnancy. Scores from the HSCL were dichotomised at a cut-off pertaining to scores of the 75th percentile; for women, this was a score >32 and for men a score >29 represented the highest depression quartile. Miscarriage was measured as any lifetime report of miscarriage or stillbirth. The same robust log binomial regression modelling described above was used to assess these relationships. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata Statistical Software, V.14.

Role of funding source

VP and BR are staff members of the funding agencies and contributed to the initial study design. Beyond this, the funders of the study had no role in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. ALW, NAP and NG had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

A total of 2376 women and 2257 men participated in the survey. Table 1 displays participant demographics stratified by gender.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of female and male participants in Somalia

| Female (n=2376) | Male (n=2257) | |||

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |

| Age (median, IQR) | 27 | (20–36) | 27 | (20–38) |

| Highest level of school attended | ||||

| None | 1568/2339 | 67.0 | 973/2197 | 44.3 |

| Primary | 475/2339 | 20.3 | 607/2197 | 27.4 |

| Secondary | 216/2339 | 9.2 | 468/2197 | 21.3 |

| College | 80/2339 | 3.4 | 155/2197 | 7.1 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Somali | 2333/2369 | 98.5 | 2220/2238 | 99.2 |

| Ethiopian | 27/2369 | 1.1 | 14/2238 | 0.6 |

| Djiboutian | 4/2369 | 0.2 | 2/2238 | 0.1 |

| Yemeni | 4/2369 | 0.2 | 1/2238 | 0.0 |

| Other | 1/2369 | 0.0 | 1/2238 | 0.0 |

| Duration in current town/city | ||||

| Less than 1 year | 142/2352 | 6.0 | 110/2180 | 5.0 |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 322/2352 | 13.7 | 327/2180 | 15.0 |

| Between 4 and 10 years | 604/2352 | 25.7 | 476/2180 | 21.8 |

| Between 11 or more years | 461/2352 | 19.6 | 446/2180 | 20.5 |

| All my life (born here) | 823/2352 | 35.0 | 821/2180 | 37.7 |

| Current employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1059/2283 | 46.4 | 12/2220 | 0.5 |

| Formally employed/business owner | 260/2283 | 11.4 | 655/2220 | 29.5 |

| Casual worker (including pastoralist, working for family business, etc.) | 763/2283 | 33.4 | 1542/2220 | 69.5 |

| Student | 201/2283 | 8.8 | 11/2220 | 0.5 |

| Each month do you have enough money to: | ||||

| Never have enough to meet the basic needs of your family during the month | 1275/2235 | 57.0 | 1210/1955 | 61.9 |

| Meet basic needs of family for less than half of the month | 166/2235 | 7.4 | 111/1955 | 5.7 |

| Meet basic needs of family for about half of the month | 217/2235 | 9.7 | 155/1955 | 7.9 |

| Meet basic needs of family for most but not all of the month | 143/2235 | 6.4 | 119/1955 | 6.1 |

| Meet basic needs of family for all of the month | 434/2235 | 19.4 | 360/1955 | 18.4 |

| Current marital status | ||||

| Never married | 481/2360 | 20.4 | 969/2221 | 43.6 |

| Married, living with someone, engaged | 1486/2360 | 63.0 | 1166/2221 | 52.5 |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 393/2360 | 16.7 | 866/2221 | 3.9 |

| In a polygamous marriage (ref: no) | 510/1636 | 31.2 | 239/1165 | 20.5 |

| Number of other wives (median, IQR) | 2 | (2–2) | 2 | (2–3) |

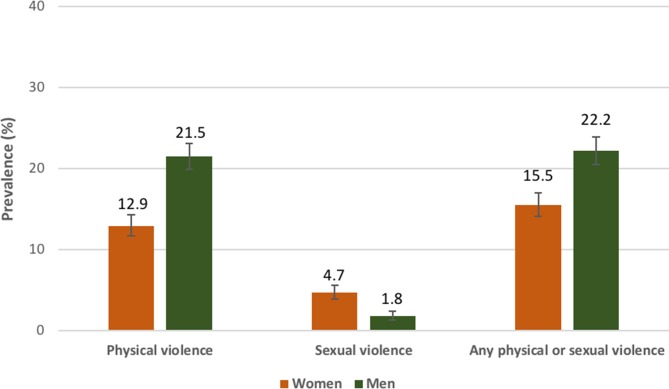

Among men and women, experiences of violence victimisation during childhood (prior to the age of 15 years) were common. One in five men (22.2%, 95% CI 20.5 to 23.9) and one in seven women (15.5%; 95% CI 14.1 to 17.0) reported any physical or sexual violence victimisation during childhood with physical forms of violence being the most common (figure 1). Perpetrators of physical violence during childhood among women included family members (43%), father/stepfather (29%) and teachers (15%), while neighbours (20%), someone from another clan (18%) and strangers (15%) were reported as perpetrators of sexual violence during childhood. Among men, commonly reported perpetrators of physical violence during childhood were father/stepfather (43%), teacher (35%) or family members (24%), while perpetrators of sexual violence included father/stepfather (34%), family friend (16%) and other individuals (16%).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of violence victimisation during childhood among adult men (n=2257) and women (n=2376) in Somalia.

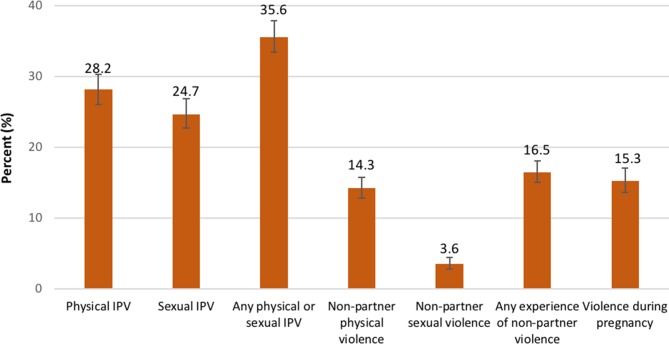

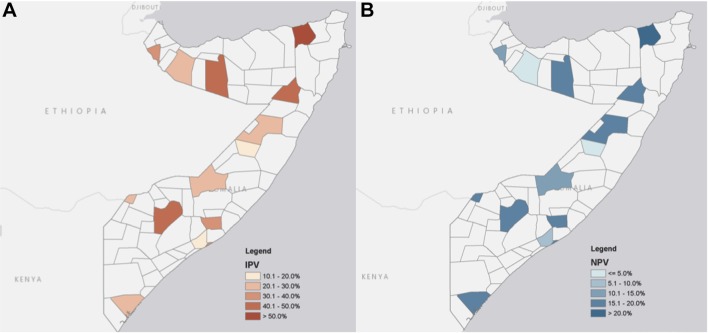

One-third (35.6%; 95% CI 33.4 to 37.9) of women reported lifetime experiences of adult physical or sexual IPV, with physical forms of violence being the most common (figure 2). The prevalence of lifetime experiences of physical or sexual IPV were heterogeneous across the 14 sites (figure 3A). Almost all (97%) of those reporting lifetime IPV also reported IPV within the last 12 months. Lifetime experiences of IPV were positively associated with belonging to a minority clan or no clan and history of migration or displacement within Somalia. Women who reported not having enough money to meet basic needs for half to none of the month and whose current or last partner chewed khat were also more likely to report lifetime history of IPV. Physical or sexual violence victimisation during childhood was associated with a threefold higher prevalence of IPV compared with no experience of violence during childhood (table 2). Because the measure of witnessing violence between parents/caregivers during childhood was not asked for participants with single parents/caregivers, we excluded this variable from the model presented in table 2. However, we conducted a subgroup analysis with those who lived with both parents/caregivers as a child to assess the impact of including this variable in the adjusted model. Witnessing violence during childhood was associated with adult experiences of IPV (adjusted prevalence ratio (adj. PrR): 1.17; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.35, data not displayed) but did not have a substantial impact on the significance or magnitude of effect of any of the other variables in the model indicating it is an additional risk factor.

Figure 2.

Lifetime gender-based violence victimisation among women in Somalia (n=2376). IPV, intimate partner violence.

Figure 3.

Geographic distributions of lifetime prevalence of (A) intimate partner violence (IPV) and (B) non-partner violence (NPV) among women in Somalia (n=2376).

Table 2.

Lifetime IPV and NPV among women in Somalia (n=2376)

| Variable | Lifetime IPV | Lifetime NPV | ||||||||||

| PrR | P values | 95% CI | adj. PrR | P values | 95% CI | PrR | P values | 95% CI | adj. PrR | P values | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.043 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.660 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.070 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.122 | 0.99 to 1.00 |

| Minority clan or not in a clan (ref: majority) | 1.83 | <0.001 | 1.60 to 2.09 | 1.95 | <0.001 | 1.52 to 2.51 | 2.00 | <0.001 | 1.66 to 2.42 | 1.42 | 0.001 | 1.17 to 1.73 |

| Any school (ref: no) | 0.82 | 0.022 | 0.69 to 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.378 | 0.65 to 1.18 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| History of migration or displacement (ref: no) | 1.91 | <0.001 | 1.59 to 2.30 | 1.63 | 0.001 | 1.23 to 2.18 | 1.80 | <0.001 | 1.42 to 2.28 | 1.14 | 0.268 | 0.90 to1.44 |

| Currently employed (ref: no) | 1.26 | 0.009 | 1.06 to 1.50 | 1.36 | 0.098 | 1.23 to 2.18 | 1.51 | 0.001 | 1.19 to 1.92 | 1.06 | 0.586 | 0.87 to 0.29 |

| Enough money to meet basic needs for none to 1/2 of month (ref: more than half to all of the month) | 1.54 | <0.001 | 1.28 to 1.86 | 1.36 | 0.022 | 1.05 to 1.91 | 1.67 | <0.001 | 1.28 to 2.19 | 1.28 | 0.074 | 0.98 to 1.68 |

| Any physical or sexual abuse in childhood (ref: no) | 2.29 | <0.001 | 2.02 to 2.59 | 3.68 | <0.001 | 2.65 to 5.13 | 5.69 | <0.001 | 4.80 to 6.74 | 4.90 | <0.001 | 4.00 to 5.96 |

| Current or last partner chewed khat (ref: no) | 1.74 | <0.001 | 1.52 to 1.98 | 2.13 | <0.001 | 1.67 to 2.72 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

adj. PrR, adjusted prevalence ratio; IPV, intimate partner violence; N/A, not applicable; NPV, non-partner violence; NS, not statistically significant; PrR, prevalence ratio; ref, reference category.

One in six women (16.5%; 95% CI 15.1 to 18.1) also reported adult, lifetime experience of physical or sexual NPV (figures 2 and 3B). Over half (58%) of women who reported sexual NPV also reported experiencing physical NPV and 15% who experienced physical violence also reported sexual NPV. Most commonly reported perpetrators of physical NPV included family members (39%), father/stepfather (23%) and someone from another clan (14%). Strangers were the most commonly reported perpetrators of sexual NPV (21%), followed by street gangs (16%) and police/soldiers (15%; data not displayed). Belonging to a minority clan or no clan and past experiences of physical or sexual violence during childhood were associated with increased experiences of adult physical or sexual NPV (table 2).

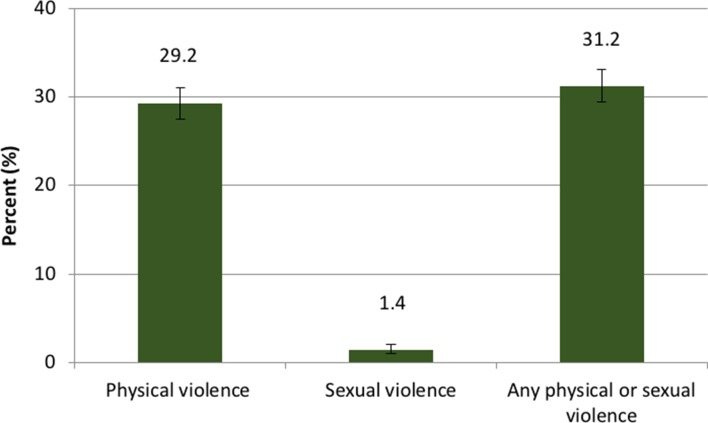

Almost one-third of men (31.24%; 95% CI 29.43 to 33.10) reported victimisation as an adult, the majority of which was physical violence (figure 4). Commonly reported perpetrators of physical violence were father/stepfather (39%), teachers (33%), family members (25%) and individuals from another clan (21%). Family friends (27%) were most frequently reported perpetrators of sexual violence in adulthood, followed by father/stepfather (23%) and someone from another clan (13%; data not displayed). Having any level of education and having enough money to meet basic needs for half to none of the month were associated with adult victimisation, although at low magnitudes of association. Experiencing physical or sexual violence during childhood, however, was associated with almost fivefold increased prevalence of victimisation in adulthood among men (table 3). In the subgroup analysis, witnessing parental/caregiver violence was also associated with increased prevalence of violence victimisation among adult men (adj. PrR: 1.13; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.23; data not displayed).

Figure 4.

Prevalence of violence victimisation among men in Somalia (n=2257).

Table 3.

Lifetime and recent violence victimisation among men in Somalia (n=2257)

| Variable | Lifetime violence victimisation | |||||

| PrR | P value | 95% CI | adj. PrR | P value | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.028 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.182 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| Minority clan or not in a clan (ref: majority) | 1.53 | <0.001 | 1.35 to 1.72 | 1.02 | 0.675 | 0.92 to 1.13 |

| Any school (ref: no) | 1.30 | <0.001 | 1.14 to 1.48 | 1.15 | 0.004 | 1.05 to 1.26 |

| History of migration or displacement (ref: no) | 1.41 | <0.001 | 1.22 to 1.62 | 1.15 | 0.030 | 1.01 to 1.30 |

| Enough money to meet basic needs for none to half of month (ref: more than half to all of the month) | 1.88 | <0.001 | 1.53 to 2.30 | 1.27 | 0.014 | 1.04 to 1.53 |

| Any physical or sexual abuse in childhood (ref: no) | 4.85 | <0.001 | 4.34 to 5.43 | 4.71 | <0.001 | 4.15 to 5.36 |

adj. PrR, adjusted prevalence ratio; N/A, not applicable; NS, not statistically significant; PrR, prevalence ratio; Ref, reference category.

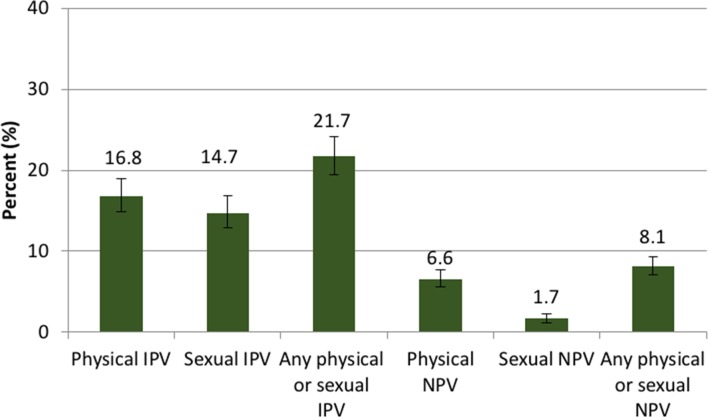

Twenty-two per cent (21.72%; 95% CI 19.53 to 24.08) of men reported lifetime sexual or physical IPV perpetration in adulthood; of these, 93% reported perpetrating violence against their partner within the last year. Lifetime IPV perpetration was associated with participant’s khat use and experiences of physical or sexual violence during childhood. Men who reported having a wife aged 15 years or less when first married were also more likely to report IPV perpetration(table 4). Witnessing parental/caregiver violence was associated with IPV perpetration in the subgroup analysis (ref: no violence: adj. PrR: 1.64; 95% CI 1.28 to 2.11; data not displayed).

Table 4.

Lifetime IPV and NPV perpetration among men in Somalia (n=2257)

| Variable | Lifetime IPV perpetration | Lifetime NPV perpetration | ||||||||||

| PrR | P values | 95% CI | adj. PrR | P values | 95% CI | PrR | P values | 95% CI | adj. PrR | P values | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.006 | 0.98 to 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.286 | 0.97 to 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.844 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.788 | 0.98 to 1.01 |

| Minority clan or not in a clan (ref: majority) | 1.45 | 0.001 | 1.17 to 1.80 | 1.25 | 0.510 | 1.00 to 1.57 | 2.17 | <0.001 | 1.62 to 2.90 | 1.78 | 0.006 | 1.18 to 2.68 |

| History of migration or displacement (ref: no) | 1.45 | 0.006 | 1.12 to 1.89 | 1.12 | 0.430 | 0.85 to 1.48 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Internally displaced (ref: no) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 2.50 | <0.001 | 1.89 to 3.31 | 1.56 | 0.025 | 1.06 to 2.31 |

| Enough money to meet basic needs for none to 1/2 of month (ref: more than half to all of the month) | 1.43 | 0.016 | 1.07 to 1.92 | 1.09 | 0.605 | 0.79 to 1.48 | 1.99 | 0.002 | 1.29 to 3.08 | 1.18 | 0.553 | 0.69 to 2.01 |

| Currently uses khat (ref: no) | 1.92 | <0.001 | 1.55 to 2.40 | 1.54 | <0.001 | 1.22 to 1.96 | 2.34 | <0.001 | 1.65 to 3.32 | 1.93 | <0.001 | 1.36 to 2.75 |

| Any physical or sexual abuse in childhood (ref: no) | 2.71 | <0.001 | 2.21 to 3.34 | 2.35 | <0.001 | 1.84 to 3.02 | 4.37 | <0.001 | 3.28 to 5.81 | 2.62 | <0.001 | 1.79 to 3.84 |

| In polygamous marriage | 1.37 | 0.013 | 1.07 to 1.75 | 1.1 | 0.479 | 0.84 to 1.44 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wife aged<=15 years. when married (ref: no) | 1.69 | 0.000 | 1.32 to 2.16 | 1.37 | 0.013 | 1.07 to 1.75 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Current/most recent partner uses khat (ref: no) | 1.81 | 0.049 | 1.00 to 3.28 | 1.14 | 0.642 | 0.64 to 2.05 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

adj. PrR, adjusted prevalence ratio; IPV, intimate partner violence; N/A, not applicable; NPV, non-partner violence; NS, not statistically significant; PrR, prevalence ratio; Ref, reference category.

Eight per cent (8.13%; 95% CI 7.07 to 9.31) of all men reported lifetime sexual or physical NPV perpetration as adults (figure 5). There was substantial overlap between IPV and NPV reporting: 75% of men who reported NPV perpetration also reported perpetrating violence against a partner and 33% of those who reported IPV perpetration also reported perpetrating NPV as adults. Demographic characteristics associated with NPV perpetration included being a member of a minority or no clan and a history of internal displacement. Use of khat and experiencing physical or sexual violence as a child were associated with increased prevalence of NPV perpetration (table 4). In the subgroup analysis, witnessing parental/caregiver violence was also associated with NPV perpetration (adj. PrR: 1.66; 95% CI 1.20 to 2.30; data not displayed).

Figure 5.

Prevalence of IPV and NPV perpetration among men in Somalia (n=2257). IPV, intimate partner violence; NPV, non-partner violence.

Current depression symptoms among adult women were associated with lifetime IPV (ref: no IPV; adj. PrR: 1.38, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.69) and lifetime NPV (ref: no NPV; adj. PrR: 1.28; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.60) but was not associated with violence during childhood, after controlling for age, clan status, displacement history and employment status. Women who reported any IPV victimisation (adj. PrR 1.36; 95% CI 1.18 to 1.57) were more likely to report history of miscarriage or stillbirth after controlling for age, number of pregnancies and experience of violence in childhood. Among men, current depression symptoms were associated with lifetime violence victimisation (adj. PrR: 1.48; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.83) and lifetime IPV perpetration (adj. PrR: 1.53; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.98). Men who reported perpetrating IPV were almost twice as likely to report having a wife/partner who had ever had a miscarriage or stillbirth (adj. PrR: 1.89; 95% CI 1.07 to 3.35), after controlling for age and number of wife/partner(s)’s pregnancies (data not displayed).

Discussion

GBV is prevalent in all three regions of Somalia, including among highly conflict-affected regions (eg, South Central) and those less affected by conflict. Our estimates suggest that, collectively, physical and sexual violence affect 36% of women and 22% of men across all three regions, which is consistent with estimates reported from other countries in the Middle East and North African region.1 We expected conflict-affected areas to have greater burdens of GBV but found that non-conflict urban areas had similar levels of GBV victimisation and perpetration. Factors related to displacement and GBV programming may provide some explanation for the similiarities in GBV prevalence, including the possibilities that individuals experienced GBV in conflict areas and were subsequently displaced to other regions for security or that GBV programmes are often targeted to humanitarian settings and may be absent in non-conflict settings.35

Experiences of childhood violence victimisation was reported by 16% of women and 22% of men. This is a critical point of intervention, as experiences of violence in childhood affect physical development and health outcomes across the life course and were highly correlated with violence victimisation and perpetration in adulthood. Witnessing violence among adult parents/caregivers during childhood had a similar effect, underscoring the importance of interfamilial transmission of violence and interventions to support parents/caregivers to create a safe and nurturing home and community environment. The impacts of witnessing IPV among adults on violence victimisation and perpetration has been supported by other prospective research.36 37 For survivors, such adverse childhood experiences may shape future relationships, as life course perspectives of childhood sexual violence theorise that early violence leads to the development of maladaptive scripts and behaviours in intimate relationships.38

Migration and internal displacement, as well as minority clan status were also associated with several forms of violence victimisation and perpetration among men and women. These findings highlight the power imbalance associated with minority status and risk for GBV. Minority populations, whether displaced, migrant or a minority clan population, often have smaller (if any) social support structures, lower access to or efficacy in seeking justice and protection and may experience a multitude of stressors such as economic and housing instability, discrimination and challenges with acculturation that can may increase risk of GBV victimisation and/or perpetration.27 39 With approximately 1.1 million people displaced within Somalia by conflict or disaster as of 2016,40 methods to support displaced or migrant populations as well as those in minority populations is important for both prevention of and response to GBV in all regions of Somalia.

Almost one in four of men reported IPV perpetration, and 8% reported NPV perpetration, with substantial overlap between IPV and NPV perpetration. Research into the perpetration of partner and non-partner violence in international settings continues to emerge,41 42 but more information is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying violence perpetration and why men use violence within intimate relationships. Findings from other countries provide insight into both structural and network level factors.42 43

This study highlights similarities and differences in GBV experiences across men and women in Somalia. Approximately one-third of men and women experienced physical forms of violence as adults, while sexual violence was much more commonly reported among women. Similar patterns of violence among men and women have been described in other conflict-affected settings.44 45 Men and women reported similar perpetrators of physical violence during adulthood, which often included family members and other known individuals, but the findings diverged with respect to the individuals reported to perpetrate sexual violence in adulthood. The most common perpetrators of non-partner sexual violence against women were strangers, street gangs and police/soldiers, while men who experienced sexual violence typically reported that this abuse was perpetrated by family members. These differences may reflect contexts reported by Amnesty International, which suggests that women in Somalia who are separated from families during displacement are more likely to experience sexual violence due to the perception that lack ‘male protection’.29

A striking finding was the ubiquity of factors that were associated with violence victimisation and perpetration among women and men. Belonging to a minority clan, having a history of migration or displacement and having low economic resources were all associated with lifetime IPV and NPV victimisation among women as well as lifetime violence victimisation and perpetration among men and speak to the impact of multiple minority statuses on power dynamics and lifetime GBV. Childhood victimisation and witnessing violence as a child were the strongest predictors of these types of violence victimisation and perpetration among women and men. That these adverse childhood experiences are similar among men and women but have very different paths in terms of who is predominantly victimised and who predominantly perpetrates violence as adults has been explained by learnt behaviours in childhood and rigidity to gender norms.46 Unique to men, however, was the use of khat (a chewed leaf that produces stimulant effects). Much like alcohol and other substances in other settings,47 48 the use of khat was significantly associated with IPV perpetration and is an important modifiable risk factor that can be addressed through community interventions.

Finally, we found significant associations between lifetime experiences of violence victimisation with depression symptomatology and reproductive health outcomes, which were consistent among men and women. While these findings are limited by the cross-sectional nature of the research, prohibiting an assessment of the directionality of the relationship, other international and prospective studies have established these relationships.49 50 In a setting with one of the highest maternal mortality rates, where risk of maternal death is 1 in 13,51 addressing GBV, particularly during pregnancy, is a critical step in improving maternal health.

Programmes to respond to GBV in these three regions are complicated and limited by multiple structural factors. Only Somaliland has laws to criminalise rape and these laws have been passed only in 2018.52 The extent to which the laws are enforced, however, remains unknown. In the other two regions and in Somaliland, until the passage of this law, female survivors could be forced to marry their perpetrator or would be accused of adultery if the perpetrator was married.4 For male survivors, there are also no mechanisms to access health services or justice, as social norms maintain that same-sex behaviours—whether consensual or forced—do not occur in Somalia. Both of these issues, coupled with community stigmatisation of GBV victimisation, prevent survivors from reporting cases of violence and accessing services.4 Health and psychosocial services to address and respond to GBV are available through humanitarian efforts,53 and future scale-up may be possible through integration with existing services, provided that mandatory reporting of cases is not legally required. Until then, efforts to focus on primary prevention that seek to change social norms among men and women as they relate to GBV are critical to addressing violence. Primary prevention programmes that engage men and boys will also require trauma-informed health and psychosocial support services for men and boys that have witnessed/experienced violence in childhood and adulthood as a strategy to prevent violence in homes and communities. Primary prevention programmes can also include outreach and training in diverse settings, such as schools, health clinics and nutrition programmes to engage parents/caregivers, teachers, police and local and regional leaders in discussion on prevention and response to harsh parenting, child abuse and neglect to secure the safety of the child and to promote long-term health and well-being of families and communities.

These findings should be viewed in light of the study limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prohibits temporal assessments of the relationships between individual and partner characteristics with the various forms of GBV outcomes. The data were collected from urban settings and those with lower security risk; thus, it is unclear how representative they may be for rural settings or those with high levels of security risk. Our study identified strong relationships between migration, displacement and violence outcomes. More research is needed to understand the nuances of these relationships and how these may affect (similarly or differently) men and women in these regions. Finally, the study was powered on the ability to provide reliable estimates of GBV victimisation among women. The small numbers of men reporting violence victimisation and perpetration limit the power of the regression analysis to identify correlates of violence among men. Furthermore, with limited time for survey implementation, we were unable to assess the extent to which violence among men is gender based; more descriptive and mixed methods research is needed to understand the unique experiences of violence victimisation among men.

GBV is prevalent in Somalia and is more pronounced for those who have experienced or witnessed violence during childhood and for those who are of a minority status. Violence is not unique to conflict-affected areas and programmes to address and response to GBV should be brought to scale in both conflict and non-conflict areas. Addressing GBV is important for improving the public health and human rights of the population and is critical for national development in Somalia and other humanitarian emergencies.

Acknowledgments

This study reflects a joint partnership by the World Bank, Unicef and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to strengthen understanding of typology and scope of gender-based violence (GBV) in Somalia, as well as to improve understanding of attitudes and perceptions of GBV across Somali communities. The study, including design, data analysis and authorship of the final reports, was conducted by Johns Hopkins School of Nursing with field research, data collection and engagement in field consultations undertaken by the INGO CISP (Comitato per lo Internazionale Sviluppo dei Popoli/International Committee for the Development of People). We are grateful for the support of the team of trained Somali research officers. Technical support and guidance on survey administration, drafting and presentation of findings was provided by the World Bank in partnership with Unicef and UNFPA.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: NG, NAP, ALW, VP, BR, AD and FK designed the study concept. AD and FK oversaw data collection. ALW, NG and NAP had full access to study data. ALW conducted statistical analysis and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors review and provided scientific input.

Funding: This study reflects a joint partnership by the World Bank, Unicef and UNFPA.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Johns Hopkins Medical Institute Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Geneva: WHO, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Interagency Standing Committee. Guidelines for gender-based violence interventions in humanitarian settings. Geneva: The IASC Taskforce on Gender in Humanitarian Assistance, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wirtz AL, Pham K, Glass N, et al. Gender-based violence in conflict and displacement: qualitative findings from displaced women in Colombia. Confl Health 2014;8:10 10.1186/1752-1505-8-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirtz AL, Glass N, Pham K, et al. Development of a screening tool to identify female survivors of gender-based violence in a humanitarian setting: qualitative evidence from research among refugees in Ethiopia. Confl Health 2013;7:13 10.1186/1752-1505-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz A, et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Curr 2014;6 10.1371/currents.dis.835f10778fd80ae031aac12d3b533ca7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stark L, Ager A. A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma Violence Abuse 2011;12:127–34. 10.1177/1524838011404252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MSF. Shattered lives: immediate medical care vital for sexual violence victims. Brussels: Medecins Sans Frontieres, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen D, Green A, Wood E. Wartime sexual violence: misconceptions, implications, and ways forward. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Sexual and gender-based violence against refugees, returnees, and internally displaced persons. Geneva, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.UN OCHA. Discussion paper 2: the nature, scope, and motivation for sexual violence against men and boys in armed conflict. Use of sexual violence in armed conflict: identifying gaps in research to inform more effective interventions UN OCHA Research Meeting – 26 June 2008, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Save the Children. Unspeakable crimes against children: sexual violence in conflict. London: Save the Children, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward J, Vann B. Gender-based violence in refugee settings. Lancet 2002;360:s13–s14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11802-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betancourt TS, Abdi S, Ito BS, et al. We left one war and came to another: resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver-child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2015;21:114–25. 10.1037/a0037538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly JTD, Colantuoni E, Robinson C, et al. From the battlefield to the bedroom: a multilevel analysis of the links between political conflict and intimate partner violence in Liberia. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000668 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivakumaran S. Sexual violence against men in armed conflict. European Journal of International Law 2007;18:253–76. 10.1093/ejil/chm013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell W. Sexual violence against men and boys. Forced Migration Review 2007;27:22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chynoweth S. "We Keep It in Our Heart" - sexual violence against men and boys in the syria crisis. Geneva: UNHCR, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christian M, Safari O, Ramazani P, et al. Sexual and gender based violence against men in the Democratic Republic of Congo: effects on survivors, their families and the community. Med Confl Surviv 2011;27:227–46. 10.1080/13623699.2011.645144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and nonpartner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and South African Medical Research Council, 2013. ISBN 978 92 4 156462 5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, et al. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet 2008;371:1165–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Linares MI, Sanchez-Lorente S, Coe CL, et al. Intimate male partner violence impairs immune control over herpes simplex virus type 1 in physically and psychologically abused women. Psychosom Med 2004;66:965–72. 10.1097/01.psy.0000145820.90041.c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, et al. When crises collide: how intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping? Trauma Violence Abuse 2009;10:306–29. 10.1177/1524838009339754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puri L. UN Women. The economic costs of violence against women. High-level Discussion on the “Economic Cost of Violence against Women”: UN Women, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacQuarrie K, Mallick L, Kishor S. Intimate partner violence and interruption of contraception use: DHS analytical studies 57. Rockville, MD: ICF International, 2016. Contract No: AS57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guha-Sapir D, Ratnayake R. Consequences of ongoing civil conflict in Somalia: evidence for public health responses. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000108 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knipscheer J, Vloeberghs E, van der Kwaak A, et al. Mental health problems associated with female genital mutilation. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:273–7. 10.1192/pb.bp.114.047944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson JE, Brown C, Russell EB, et al. Acculturation, partner violence, and psychological distress in refugee women from Somalia. J Interpers Violence 2008;23:1654–63. 10.1177/0886260508314310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morof DF, Sami S, Mangeni M, et al. A cross-sectional survey on gender-based violence and mental health among female urban refugees and asylum seekers in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;127:138–43. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amnesty International. Amnesty International Report 2017/18 - Somalia: Amnesty International, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.UNHCR. Camp coordination and camp management cluster: operational presence of cluster partners: CCCM Cluster, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleijn WC, Hovens JE, Rodenburg JJ. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in refugees: assessments with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Hopkins symptom Checklist-25 in different languages. Psychol Rep 2001;88:527–32. 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.2.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO ethical and safety recommendations for researching, documenting and monitoring sexual violence in emergencies. Geneva: WHO, 2007. ISBN 978 92 4 159568 1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenland S. Interpretation and choice of effect measures in epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol 1987;125:761–8. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon RA. Issues in multiple regression. Am J Sociol 1968;73:592–616. 10.1086/224533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.UN OCHA. Somalia - who does what where matrix - as of september 2017. Gevea: UN OCHA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low S, Tiberio SS, Shortt JW, et al. Intergenerational transmission of violence: The mediating role of adolescent psychopathology symptoms. Dev Psychopathol 2017;1313:1–13. 10.1017/S0954579417001833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith CA, Ireland TO, Park A, et al. Intergenerational continuities and discontinuities in intimate partner violence: a two-generational prospective study. J Interpers Violence 2011;26:3720–52. 10.1177/0886260511403751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browning CR, Laumann EO. Sexual contact between children and adults: a life course perspective. Am Sociol Rev 1997;62:540–60. 10.2307/2657425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prosman GJ, Jansen SJ, Lo Fo Wong SH, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence among migrant and native women attending general practice and the association between intimate partner violence and depression. Fam Pract 2011;28:267–71. 10.1093/fampra/cmq117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Callaghan S, Sydney C. Africa Report on Internal Displacement: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jewkes R, Fulu E, Tabassam Naved R, et al. Women’s and men’s reports of past-year prevalence of intimate partner violence and rape and women’s risk factors for intimate partner violence: A multicountry cross-sectional study in Asia and the Pacific. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002381 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulawa MI, Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, et al. Associations Between Peer Network Gender Norms and the Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence Among Urban Tanzanian Men: a Multilevel Analysis. Prev Sci 2018;19:427–36. 10.1007/s11121-017-0835-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jewkes R, Jama-Shai N, Sikweyiya Y. Enduring impact of conflict on mental health and gender-based violence perpetration in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186062 10.1371/journal.pone.0186062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Kiss L, et al. Men’s and women’s experiences of violence and traumatic events in rural Cote d’Ivoire before, during and after a period of armed conflict. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003644 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vinck P, Pham PN. Association of exposure to intimate-partner physical violence and potentially traumatic war-related events with mental health in Liberia. Soc Sci Med 2013;77:41–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lisak D, Hopper J, Song P. Factors in the cycle of violence: gender rigidity and emotional constriction. J Trauma Stress 1996;9:721–43. 10.1002/jts.2490090405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schafer A, Koyiet P. Exploring links between common mental health problems, alcohol/substance use and perpetration of intimate partner violence: A rapid ethnographic assessment with men in urban Kenya. Glob Ment Health 2018;5:e3 10.1017/gmh.2017.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Messersmith LJ, Halim N, Steven Mzilangwe E, et al. Childhood Trauma, Gender Inequitable Attitudes, Alcohol Use and Multiple Sexual Partners: Correlates of Intimate Partner Violence in Northern Tanzania. J Interpers Violence 2017:088626051773131 10.1177/0886260517731313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwako LE, Glass N, Campbell J, et al. Traumatic brain injury in intimate partner violence: a critical review of outcomes and mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abuse 2011;12:115–26. 10.1177/1524838011404251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002;359:1331–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet 2016;387:462–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.BBC. Somaliland passes first law against rape, 2018. Sect. Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 53.UNHCR. Somalia Situation: Supplementary Appeal, January-December 2017. Geneva: UNHCR, 2017. [Google Scholar]