Abstract

Purpose of Review

Collaborative care (CoCM) is an evidence-based model for the treatment of common mental health conditions in the primary care setting. Its workflow encourages systematic communication among clinicians outside of face-to-face patient encounters, which has posed financial challenges in traditional fee-for-service reimbursement environments.

Recent Findings

Organizations have employed various financing strategies to promote CoCM sustainability, including external grants, alternate payment model contracts with specific payers and the use of billing codes for individual components of CoCM. In recent years, Medicare approved fee-for-service, time-based billing codes for CoCM that allow for the reimbursement of patient care performed outside of face-to-face encounters. A growing number of Medicaid and commercial payers have followed suit, either recognizing the fee-for-service codes or contracting to reimburse in alternate payment models.

Summary

Although significant challenges remain, novel methods for payment and cooperative efforts among insurers have helped move CoCM closer to financial sustainability.

Keywords: Collaborative care, Healthcare financing, Health service reimbursement, Financial sustainability, Health Policy

Introduction

The Collaborative Care Model (CoCM) was originally developed by researchers at the University of Washington in the 1990s to improve outcomes for adults with depression in primary care. To date, the efficacy and effectiveness of CoCM have been shown in more than eighty RCTs1,2. Additionally, using its core principles, others have extended CoCM to the treatment of individuals: (1) in a variety of treatment settings (e.g., inpatient treatment3 and specialty medical care4), (2) with a number of mental health diagnoses (e.g., anxiety1, bipolar disorder5 and post-traumatic stress disorder6–8) and (3) of different age ranges (e.g., adolescents9). Despite its robust evidence base and extensive use, payment for this care model has remained a challenging task for states, municipalities, payers and healthcare systems. In many cases, uncertainty about CoCM implementation10 and maintenance costs11–13, as well as the lack of a clear pathway for reimbursement to cover these costs, has made the model appear financially untenable14. In this paper, we describe the CoCM clinical model, past and current strategies for its financing in various practice settings and funding approaches for larger implementation efforts. Specifically, we will highlight representative grey and white literature-derived examples of CoCM financing from federal programs, research studies, healthcare systems, academic medical centers and managed care organizations. Instances of alternate reimbursement model utilization for CoCM, such as case-rate payments and bundled payments, will be highlighted. Finally, the authors will discuss the importance of multi-payer reimbursement strategies, as well as newer time-based, fee-for-service codes that are increasingly billable from both public and commercial payers.

Treatment - The Collaborative Care Model

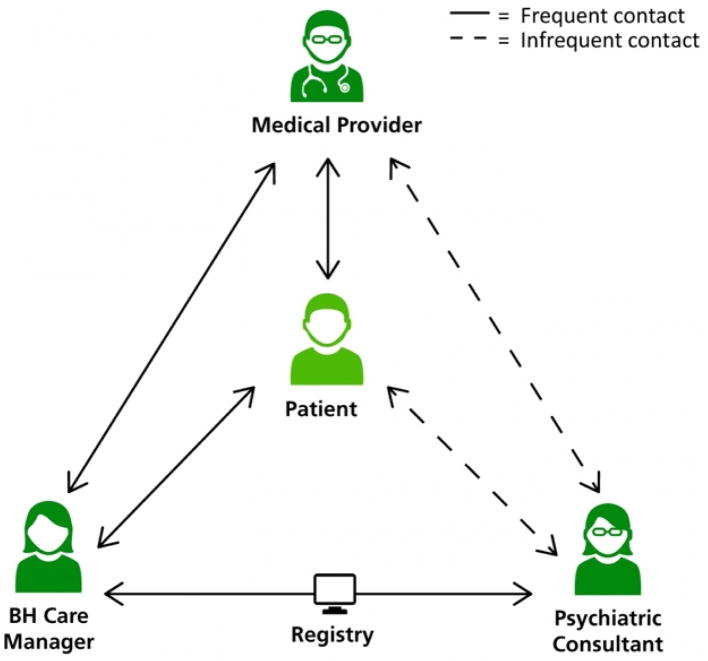

CoCM is a specific type of team-based integrated care that requires systematic follow-up and coordination between behavioral health and primary care medical providers15. The model deploys behavioral health care managers in medical practices to provide assessments, brief psychosocial interventions and medication management support, all with back-up and regular consultation from a designated psychiatric consultant. A CoCM registry is maintained by the primary care practice and care manager to track patients’ progress toward treatment goals. Figure 1 demonstrates the model of systematic collaboration between the primary care provider, psychiatric consultant and care manager, with the patient at the center. Typical frequency of contact between the patient and individual care team members is also denoted in the figure with dashed and solid lines. Since traditional fee-for-service reimbursement is based on face-to-face time between a patient and provider, CoCM poses a number of payment challenges. Of all providers on the CoCM treatment team, behavioral health care managers spend the most time face-to-face with the patient. Depending on their background and credentials, this time may or may not be billable. For example, licensed independent clinical social workers (LICSWs) are reimbursed by most public and private payers for behavioral health evaluations and psychotherapy16. This is, however, not the case for registered nurses (RNs) or others in the same role. Additionally, care managers in CoCM are incentivized to provide as much patient interaction as possible through telephone, secure messaging17 and other mechanisms to maximize their efficiency and patient reach. This work has often gone unreimbursed. Although psychotherapy and pharmacology services are billable with telehealth fee-for-service codes for beneficiaries of Medicare and a growing number of Medicaid and commercial payers18–20, behavioral health care management has not historically qualified as a billable service in this regard. In the CoCM model, psychiatric consultants see a relatively small percentage of the total patient panel face-to-face, limiting their fee-for-service billing opportunities. Instead, the consultant spends time (often unreimbursed) interacting directly with the primary care provider, treatment planning or reviewing cases with the care manager.

Figure 1.

15. Reprinted from “AIMS Center - Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions. Collaborative Care - Team Structure (2018). Available at: https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/team-structure.” Used with permission from the University of Washington AIMS Center

Current and Historical Funding Sources for Collaborative Care

Historically, due to the lack of clear options for CoCM financing and reimbursement, health care organizations around the country have employed a variety of strategies. Some have primarily sought reimbursement in the form of traditional fee-for-service (FFS) public or commercial payer codes for specific billable services based on the level of training and background of the behavioral health care manager. As mentioned previously, this has compelled some organizations to prioritize the hiring of providers that are able to independently bill for mental health assessments, psychotherapy and counseling, such as licensed independent clinical social workers (LICSWs) or PhD-level therapists16. Others have approached financing differently; a multitude of federal programs, healthcare systems, academic medical centers and managed care organizations have self-funded implementations, created tailored payment models or offered grants to cover the costs of CoCM initiation. Some examples of federal programs have included the Re-Engineering Systems of Primary Care Treatment of PTSD and Depression in the Military (RESPECT- MIL) program (funded primarily through Army Medical Command Behavioral Health resources)8,21 and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) CoCM initiatives21–24. The University of California-Davis Health System, an academic center, funded its Depression Care Management project through various grants and the California Department of Health Management and Education21. Another academic implementation at the University of Washington, termed the Behavioral Health Integration Program (BHIP), has been funded through a combination of public insurance billing, commercial billing and internal support25. Montefiore Medical Center in New York funded a similar program partially through a CMS Health Care Innovation Award26. The multi-center and geographically diverse Care of Mental, Physical and Substance-use Syndromes (COMPASS) study was the first large-scale implementation initiative for TEAMcare27, which adapted the CoCM model for patients with depression and chronic medical illness. This effort was financed through a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) grant, although each participating organization developed its own plan for sustainable funding after completion of the study28. A number of managed care organizations, such as Group Health (now Kaiser Permanente of Washington State)29 and Intermountain Healthcare30,31 have invested significant portions of their discretionary health care dollars in CoCM and behavioral health integration more broadly. Other CoCM programs have been primarily funded through grants that include (but are not limited to) the MacArthur Initiative on Depression and Primary Care at Dartmouth and Duke, the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) Behavioral Health Service Expansion Funding, the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health Integrated Health Care Initiative, the ICARE Partnership and the RWJF Depression in Primary Care National Program32.

Adjusted Case Rate Reimbursement - Washington’s Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP)

The Washington State Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP), which began in 2007, was financed through a partnership between the State of Washington, the Community Health Plan of Washington, more than 100 community health clinics and 30 community mental health centers throughout the state33. Until 2018, it was funded by the State of Washington and administered by a non-profit managed care plan, the Community Health Plan of Washington (CHPW), in collaboration with the Public Health Department of Seattle and King County. Initially, MHIP provided CoCM for unemployed adults, the temporarily disabled, veterans and their family members, the uninsured, low-income mothers, children and other older adults33. In addition to traditional fee-for-service payments to primary care providers who saw patients face-to-face, participating clinics received lump sum payments for on-site care managers adjusted by caseload size33. This funding strategy was employed, in part, due to results from prior research on chronic physical disease that found case rate payments to be the most practical and straightforward way to reimburse for the care management of patients with complex, chronic needs16,34. Additionally, psychiatric consultants received contract payments from CHPW for systematic review of CoCM caseload patients and treatment recommendations to the patients’ primary care providers (PCPs). Beginning in 2009, due to concern for substantial variation in quality and outcomes across the participating community health clinics, a pay-for-performance initiative was implemented to make a portion of the program funding to participating clinics contingent on meeting several quality indicators associated with evidence-based CoCM33. This payment strategy withheld twenty-five percent of payments to each clinic until it met a number of agreed upon quality indicators35,36. Recent evidence has demonstrated substantial improvements in quality of care and clinical outcomes in MHIP patients served after the introduction of this pay-for-performance (P4P) component33,37. Since its inception, more than 50,000 patients have been treated in the MHIP program throughout Washington State36.

Bundled Payments - Minnesota’s DIAMOND Project

In 2008, healthcare leaders in Minnesota spearheaded Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction (DIAMOND) - a joint effort to make CoCM reimbursable with specifically designed billing codes for all of the state’s major commercial payers. Partially due to the realization that inconsistencies in billing requirements among different payers would threaten the viability of CoCM in Minnesota, this project was led by a unique partnership that included the state’s six largest commercial health plans, the Minnesota Department of Human Services and medical providers within the state38. The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), a quality improvement organization in Minnesota, played a major role in coordinating and supporting this state-wide effort. Together, these groups and organizations agreed that improving depression care was a priority and that the fee-for-service reimbursement system available at the time (largely for chronic care management) was inadequate for primary care practices to support depression care management38. ICSI helped broker an agreement from major parties involved to initiate CoCM with a common set of depression improvement goals and outcomes (e.g., the Patient Health Questionaire-9)38. Under DIAMOND, primary care providers implemented CoCM for depression care and could bill for a negotiated bundled monthly payment rate, which was designed to cover all associated clinical costs (including care managers’ salaries/benefits and supervision time from a psychiatrist)38. While anti-trust regulations prevented medical groups from disclosing the specific terms of their negotiated bundled payments, ICSI independently assessed CoCM startup and maintenance costs for each practice38. Findings demonstrated that the availability of this bundled payment mechanism was enough for many diverse practices to accept the burden of CoCM startup costs (such as hiring care managers and registry development) and to enroll patients from different payers in their CoCM program38. The financial success of the DIAMOND project has been ascribed to multiple components of the design and implementation strategy. Its authors contend that the presence of the ICSI (as a broker) and the agreement on major outcome benchmarks by important stakeholders (the state, payers and providers) were instrumental. This made it possible for clinics to provide and bill for CoCM services in a similar fashion irrespective of a patient’s commercial insurance company, thereby substantially reducing administrative burden. DIAMOND also released outcomes publicly in a timely manner (without relying on the sometimes lengthy peer-review process) and attempted to demonstrate return on investment (by publishing reports on work productivity increases from CoCM), both in an effort to maintain stakeholder engagement38. To date, the DIAMOND project remains one of the largest and most extensively described multi-payer efforts to reimburse for CoCM services.

Medicare, FQHC and RHC Fee-For-Service Reimbursement

In 2016, the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded its efforts to facilitate behavioral health care access in primary care by offering the opportunity for fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement of CoCM for Medicare beneficiaries. Beginning in CY 2017, three temporary G-codes, G0502, G0503 and G0504, became billable39. These codes, which were designed similarly to Medicare’s CY 2015-initiated, time-based Chronic Care Management (CCM) codes40,41, reimbursed treating (billing) practitioners for the cumulative time that they and their staff spent managing patients in the evidence-based CoCM model over the course of a calendar month. Briefly, G0502 was used for the first seventy minutes in the first month for behavioral health care manager activities (with the stipulation that the care manager was working with a psychiatric consultant). G0503 could be used for the first sixty minutes in a subsequent month of behavioral health care manager activities. G0504 allowed for the billing of an additional thirty minutes in a calendar month of behavioral health care manager activities listed above39,42. At the same time, CMS also created a fourth billing code, G0507, for behavioral health care management services not meeting criteria for CoCM39. In CY 2018, these G-codes were transitioned to largely identical CPT codes 99492, 99493, 99494 and 99484 (see Table 1)42,43.

Table 1.

Medicare CPT Payment Summary – 201842

| CPT | Description | Payment/Patient (Non-Facilities*) | Payment/Patient (Facilities*) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 99492 | Initial psych care mgmt, 70 min/month – CoCM | $161.28 | $90.36 |

| 99493 | Subsequent psych care mgmt, 60 min/month – CoCM | $128.88 | $81.72 |

| 99494 | Initial/subsequent psych care mgmt, additional 30 min CoCM | $66.60 | $43.56 |

| 99484 | Care mgmt services, minimum 20 min – General Behavioral Health Integration (BHI) Services | $48.60 | $32.76 |

“Non-Facilities” refers to primary care settings, while “Facilities” refers to hospital or other facility settings.

Adapted from “AIMS Center - Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions. Cheat Sheet on Medicare Payments for Behavioral Health Integration Services. (2018). Available at: https://aims.uw.edu/sites/default/files/CMS_FinalRule_BHI_CheatSheet.pdf.” Adapted with permission from the University of Washington AIMS Center.

Additionally, to improve access to behavioral health care in rural and underserved areas, CMS rendered CoCM and general behavioral health integration services billable to Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) in CY 2018 with different stipulations; instead of three codes, only one CoCM code is available for RHCs and FQHCs43,44. This code, G0512, which can be billed no more than once per month, reimburses the average of the payment for G0502 (99494) and G0503 (99493). It accounts for a minimum of 70 minutes of care time in an initial month of treatment and 60 minutes in subsequent months (see Table 2)44. There is no analogous code to G0504 (99494), meaning there is no payment to RHCs or FQHCs for additional time spent in a calendar month43. One additional code, G0511, is available for general behavioral health integration not meeting criteria for CoCM43,44.

Table 2.

FQHC and RHC Medicare Codes and Payment Summary – 201844

| Code | Description | Payment |

|---|---|---|

| G0511 | General Care Management Services – Minimum 20 min/month | $62.28 |

| G0512 | Psychiatric CoCM – Minimum 70 min initial month and 60 min subsequent months | $145.08 |

Adapted from “AIMS Center - Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions. Cheat Sheet on Medicare Payments for Behavioral Health Integration Services in Federally Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Clinics. (2018). Available at: https://aims.uw.edu/sites/default/files/CMS_FinalRule_FQHCs-RHCs_CheatSheet.pdf.” Adapted with permission from the University of Washington AIMS Center.

Although CoCM Medicare G-codes were designed to incentivize evidence-based CoCM and have been extensively marketed to systems and providers14,39, their uptake appears to have been relatively slow nationwide. According to preliminary CY 2017 Medicare claims data recently provided to the University of Washington’s Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center from the American Psychiatric Association (APA), there are relatively few healthcare systems or clinics that have adopted and continued to use these codes (Becky Yowell, personal communication, 15 May 2018).

Medicare’s comparable chronic care management (CCM) codes, which were released in January 2015, showed a similarly slow uptake. The CCM model, like CoCM, is intended to enhance care continuity, care coordination, and ongoing management for patients with chronic conditions41. Patients are eligible for CCM if: (1) they have two or more chronic conditions expected to last at least twelve months, (2) these conditions place the patient at significant risk of death, acute exacerbation/decompensation, or functional decline and (3) a comprehensive care plan is established45. Medicare’s CCM codes, which were specifically designed to reimburse for these services (outside of face-to-face clinical encounters), were billable for all beneficiaries who met criteria41. In a 2017 study, O’Malley and colleagues found that, during the first fifteen months of the new CCM payment policy, only about 4.5 percent of eligible non-institutional primary care providers billed Medicare for this service41. The same study also noted some of the most common barriers to code uptake, which included Medicare-stipulated patient cost-sharing, perceived inadequate reimbursement, requisite workflow modifications and inadequate health information capabilities41. Due to the similarities between Medicare’s CCM and CoCM codes, it is likely that practices will encounter similar implementation challenges, although this requires further investigation. Of note, recent studies have used computer modeling to demonstrate that, under certain conditions, both CoCM and CCM codes may be cost-neutral or profitable for health systems40,46.

Medicaid and Commercial Payer Reimbursement for CoCM

In recent years, a number of state Medicaid and commercial payers have also begun reimbursing for CoCM. Unlike in Medicare, where new billing codes are often available to all beneficiaries nationwide at the same time, Medicaid and commercial payers are managed at the state or local level, leading to substantial heterogeneity in reimbursement of newer service additions, such as CoCM. The first known state Medicaid payer to embrace CoCM was the previously mentioned Community Health Plan of Washington (CHPW), which provided case-rate reimbursement for the state’s MHIP program in collaboration with Public Health-Seattle and King County beginning in 2007. However, of the five Washington State Medicaid products at the time, CHPW was the only payer reimbursing. In early 2017, the Washington State Legislature appropriated funds through its budget bill47 to adopt existing Medicare fee-for-service CoCM codes for the beneficiaries of all state Medicaid products beginning in July, 201736. This initiative was intended to improve statewide access to behavioral health care and to financially assist practices that had already implemented or were planning to implement CoCM36.

New York State Medicaid launched CoCM reimbursement in 2015 through its Collaborative Care Medicaid program (CCMP). Similarly to MHIP in Washington State, the CCMP provided value-based reimbursement using monthly case-rate payments for eligible managed care beneficiaries enrolled in a qualified CoCM program48–50. CCMP also included a pay-for-performance component that was similar, but not identical, to that of the post-2009 MHIP program33. It stipulated that 25% of the monthly, patient-level case-rate payment was initially withheld, but could be paid retroactively after six months for patients that: (1) improved clinically or (2) had their treatment plan adjusted due to their lack of clinical improvement49. This pay-for-performance initiative was designed to incentivize fidelity to the evidence-based operations of the CoCM model. Elsewhere, the state of Maryland recently appropriated pilot lump-sum funding for CoCM in three of its Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs)51,52. Other states, including and Hawaii53 and Ohio (Mary Gabriel, personal communication, 14 May 2018), have recently announced that Medicaid will reimburse for CoCM CPT codes in the near future. Furthermore, an increasing group of commercial payers nationwide are beginning to offer reimbursement for the CoCM CPT codes.

Multi-Payer Efforts for Collaborative Care Reimbursement

Formal reimbursement for CoCM by third-party payers, although increasingly common, has historically been the exception rather than the rule. Most CoCM initiatives to date have been funded through clinical implementation grants, research studies, or discretionary spending from single-payer systems (e.g. the Veterans Health Administration) or managed care organizations (e.g. Intermountain Health or Kaiser Permanente). Even as a growing number of insurance companies nationwide have initiated reimbursement for CoCM CPT codes, these decisions have largely been made unilaterally in single-payer efforts. This has, at times, led to precarious situations and difficult choices. In the cases of organizations who are already providing CoCM but can no longer solely rely on previous sources of funding (e.g. grants or institutional support), a decision must be made whether to continue to offer the service for all patients regardless of payer (potentially taking a financial loss) or to restrict it to those whose insurance plans are reimbursing (potentially limiting the impact and reach of the program). Even after an organizational decision is made in this regard, clinical and operational challenges arise when attempting to differentially deliver health services by patients’ insurance provider and when there are significant intra-system differences in payer mix at the clinic level. A third option for these organizations is to bill all patients for more universally reimbursed, non-CoCM fee-for-service codes (e.g. psychotherapy and mental health evaluation), although this could potentially create new workforce restrictions (e.g. the mandated hiring of LICSWs for the care manager role) and would not provide reimbursement for care coordination outside of face-to-face visits. In the case of organizations that have yet to implement CoCM and are looking to do so in the wake of the newly available billing codes, it will likely take a critical mass of payers reimbursing to instill confidence that the service can be financially viable and sustainable. In both scenarios, cooperative, multi-payer efforts by regional insurance providers to begin reimbursement for CoCM codes at the same time (similar to Minnesota’s DIAMOND project) would act as major facilitators by reducing administrative burden and financial risk for individual clinics and organizations.

Conclusions

CoCM is an effective treatment for depression and other common mental health conditions in the primary care setting. Historically, its unconventional workflow and team structure, which include elements of care outside of face-to-face visits, have posed significant challenges to financing and reimbursement. In recent years, Medicare and a growing number of Medicaid and commercial payers have recognized novel fee-for-service billing codes specifically for CoCM. Although these codes have successfully offered payment for services that previously went unreimbursed, their payer adoption and clinical uptake have been slow. The authors contend that a cooperative, multi-payer approach (using either fee-for-service codes or bundled payments) would be most effective in facilitating CoCM and its corresponding fee-for-service billing code usage nationwide. With more streamlined opportunities for reimbursement of CoCM, clinics and organizations would have a clearer pathway for implementation and sustainability of this highly effective, evidence-based model for integrated care.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Carlo was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH20021 Psychiatry– Primary Care Psychiatry Fellowship Program Training Grant)

Contributor Information

Andrew D. Carlo, University of Washington School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences - 1959 NE Pacific Street, Box 356560, Room BB1644, Seattle, WA 98195-6560.

Jürgen Unützer, University of Washington School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences - 1959 NE Pacific Street, Box 356560, Room BB1644, Seattle, WA 98195-6560.

Anna D. H. Ratzliff, University of Washington School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences - 1959 NE Pacific Street, Box 356560, Room BB1644, Seattle, WA 98195-6560.

Joseph M. Cerimele, University of Washington School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences - 1959 NE Pacific Street, Box 356560, Room BB1644, Seattle, WA 98195-6560.

References

- 1.Archer J, et al. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Archer J, editor. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. pp. 2–4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–21. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huffman JC, et al. A collaborative care depression management program for cardiac inpatients: depression characteristics and in-hospital outcomes. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woltmann E, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:790–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerimele JM, Halperin AC, Spigner C, Ratzliff A, Katon WJ. Collaborative care psychiatrists’ views on treating bipolar disorder in primary care: a qualitative study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;36:575–80. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortney JC, et al. Telemedicine-based collaborative care for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:58–67. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel CC, et al. Centrally Assisted Collaborative Telecare for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Among Military Personnel Attending Primary Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:948. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel CC, et al. Implementing collaborative primary care for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder: Design and sample for a randomized trial in the U.S. military health system. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shippee ND, et al. Effectiveness in Regular Practice of Collaborative Care for Depression Among Adolescents: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Psychiatr Serv. 2018 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700298. appi.ps.2017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CF, et al. Organizational Cost of Quality Improvement for Depression Care. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:225–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palinkas LA, Ell K, Hansen M, Cabassa L, Wells A. Sustainability of collaborative care interventions in primary care settings. J Soc Work. 2011;11:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overbeck G, Davidsen AS, Kousgaard MB. Enablers and barriers to implementing collaborative care for anxiety and depression: A systematic qualitative review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0519-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nutting PA, et al. Care management for depression in primary care practice: findings from the RESPECT-Depression trial. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:30–37. doi: 10.1370/afm.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Press MJ, et al. Medicare Payment for Behavioral Health Integration. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:405–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1614134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AIMS Center - Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions. [Accessed: 18th April 2018];Collaborative Care - Team Structure. 2018 Available at: https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/team-structure. Used with permission from the University of Washington AIMS Center, [22nd May 2018]

- 16.Bachman J, Pincus HA, Houtsinger JK, Unützer J. Funding mechanisms for depression care management: opportunities and challenges. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhat A, Mao J, Unützer J, Reed S, Unger J. Text messaging to support a perinatal collaborative care model for depression: A multi-methods inquiry. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;52:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilman M, Stensland J. Telehealth and Medicare: Payment Policy, Current Use, and Prospects for Growth. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3:E1–E17. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.04.a04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas MD, et al. Assessing Telemedicine Utilization by Using Medicaid Claims Data. Psychiatr Serv. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500518. appi.ps.201500518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams SM, et al. TeleMental Health: Standards, Reimbursement, and Interstate Practice. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1078390318763963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanderlip E, et al. APA/APM Rep Dissem Integr Care. 2016. Dissemination of Integrated Care within Adult Primary Care Settings: The Collaborative Care Model; pp. 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dundon M, Dollar K. Primary Care-Mental Health Integration Co-Located, Collaborative Care: An Operations Manual. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith JL, Williams JW, Owen RR, Rubenstein LV, Chaney E. Developing a national dissemination plan for collaborative care for depression: QUERI Series. Implement Sci. 2008;3:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubenstein LV, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Heal J Collab Fam Healthc. 2010;28:91–113. doi: 10.1037/a0020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.University of Washington AIMS Center. Behavioral Health Integration Program (BHIP) 2018 Available at: https://aims.uw.edu/behavioral-health-integration-program-bhip.

- 26.Gilman B, et al. Evaluation of the Round Two Health Care Innovation Awards (HCIA R2): Second Annual Report. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katon WJ, et al. Collaborative Care for Patients with Depression and Chronic Illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman KJ, et al. The COMPASS initiative: description of a nationwide collaborative approach to the care of patients with depression and diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;44:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon GE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1638–44. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reiss-Brennan B, Briot PC, Savitz LA, Cannon W, Staheli R. Cost and Quality Impact of Intermountain’s Mental Health Integration Program. J Healthc Manag. 2010;55:97–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiss-Brennan B, et al. Association of Integrated Team-Based Care With Health Care Quality, Utilization, and Cost. Jama. 2016;316:826. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.RAND. Integration of Primary Care and Behavioral Health: RAND Report to the Pennsylvania Health Funders’ Collaborative. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unützer J, et al. Quality improvement with pay-for-performance incentives in integrated behavioral health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:41–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berenson RA, Horvath J. Confronting the barriers to chronic care management in Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;(Suppl Web):W3-37–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao Y, et al. Designing payment for collaborative care for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1436–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Psychiatric Association. Washington State. Making the Case: Medicaid Payment for the Collaborative Care Model. 2018 Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care/medicaid-payment-and-collaborative-care-model.

- 37.Bao Y, et al. Value-based payment in implementing evidence-based care: the Mental Health Integration Program in Washington state. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23:48–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Donnell AN, Williams M, Kilbourne AM. Overcoming roadblocks: Current and emerging reimbursement strategies for integrated mental health services in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1667–1672. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2496-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Program; Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2017. Federal Register. 2016;81:80170–80562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basu S, Phillips RS, Bitton A, Song Z, Landon BE. Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practices: A modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–588. doi: 10.7326/M14-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Malley AS, et al. Provider Experiences with Chronic Care Management (CCM) Services and Fees: A Qualitative Research Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4134-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.AIMS Center - Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions. Cheat Sheet on Medicare Payments for Behavioral Health Integration Services. 2018 Adapted from works created by the University of Washington AIMS Center, [22nd May 2018], [ https://aims.uw.edu/sites/default/files/CMS_FinalRule_BHI_CheatSheet.pdf]

- 43.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Program; Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2018; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; and Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program. Fed Regist. 2017;82:33950–34203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.AIMS Center - Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions. Cheat Sheet on Medicare Payments for Behavioral Health Integration Services in Federally Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Clinics. 2018 Adapted from works created by the University of Washington AIMS Center, [22nd May 2018], [ https://aims.uw.edu/sites/default/files/CMS_FinalRule_FQHCs-RHCs_CheatSheet.pdf]

- 45.Department of Health and Human Services - Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services - Medicare Learning Network. Chronic Care Management Services. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basu S, et al. Behavioral Health Integration into Primary Care: a Microsimulation of Financial Implications for Practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:1330–1341. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4177-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.State of Washington - Senate Ways & Means. ENGROSSED SUBSTITUTE SENATE BILL 5048 State. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 48.NYS Office of Mental Health/NYS Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services. Medicaid Collaborative Care Depression Treatment Program – Billing Guidance Article. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Psychiatric Association. Making the Case: Medicaid Payment for the Collaborative Care Model. New York State Collaborative Care Initiative: 2012–2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sederer LI, Derman M, Carruthers J, Wall M. The New York State Collaborative Care Initiative: 2012–2014. Psychiatr Q. 2016;87:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11126-015-9375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Psychiatric Association. Maryland Collaborative Care Case Study. Making the Case: Medicaid Payment for the Collaborative Care Model. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care/medicaid-payment-and-collaborative-care-model.

- 52.Madaleno R. Maryland Medical Assistance Program – Collaborative Care Pilot Program. 2018. p. 835. [Google Scholar]

- 53.House of Representatives; Twenty-Ninth Legislature 2017; State of Hawaii. Relating To Improving Access To Psychiatric Care For Medicaid Patients. 2017. p. 1272. [Google Scholar]