Abstract

Introduction

Binge drinking (four or more drinks for women, five or more drinks for men on an occasion) accounts for more than half of the 88,000 U.S. deaths resulting from excessive drinking annually. Adult binge drinkers do so frequently and at high intensity; however, there are known disparities in binge drinking that are not well characterized by any single binge-drinking measure. A new measure of total annual binge drinks was used to assess these disparities at the state and national levels.

Methods

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2015 data (analyzed in 2016) were used to estimate the prevalence, frequency, intensity, and total binge drinks among U.S. adults. Total annual binge drinks was calculated by multiplying annual binge-drinking episodes by binge-drinking intensity.

Results

In 2015, a total of 17.1% of U.S. adults (37.4 million) reported an annual average of 53.1 binge-drinking episodes per binge drinker, at an average intensity of 7.0 drinks per binge episode, resulting in 17.5 billion total binge drinks, or 467.0 binge drinks per binge drinker. Although binge drinking was more common among young adults (aged 18–34 years), half of the total binge drinks were consumed by adults aged ≥35 years. Total binge drinks per binge drinker were substantially higher among those with lower educational levels and household incomes than among those with higher educational levels and household incomes.

Conclusions

U.S. adult binge drinkers consume about 17.5 billion total binge drinks annually, or about 470 binge drinks/binge drinker. Monitoring total binge drinks can help characterize disparities in binge drinking and help plan and evaluate effective prevention strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Excessive alcohol use is responsible for 88,000 deaths in the U.S. each year, including one in ten deaths among working-age adults,1 and cost the U.S. $249 billion, or $2.05 per drink, in 2010.2 Binge drinking, defined as consuming four or more drinks per occasion for women or five or more drinks per occasion for men,3 accounts for half of these deaths,1 and three quarters of the estimated economic costs.2 Binge drinking typically results in acute impairment, and is a risk factor for a number of health and social problems, including unintentional injuries, interpersonal violence, suicide, alcohol poisoning, high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke, cancer, liver disease, and severe alcohol use disorder.4 Additionally, more than half of all the alcohol sold in the U.S. is consumed while binge drinking.5 Reducing binge drinking among adults is also a leading health indicator in Healthy People 2020.6

Binge drinking is common among U.S adults, and adult binge drinkers do so frequently and at high intensity.7 However, there are important disparities in binge drinking at the state and national levels based on sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, education, and income) that are not well characterized by any single binge-drinking measure.7 For example, the prevalence of binge drinking is known to be significantly higher among adults with higher household incomes compared with those with lower household incomes, but the frequency and intensity of binge drinking are significantly higher among binge drinkers with lower household incomes compared with those with higher household incomes.7 A comprehensive measure of binge drinking is also needed to more fully characterize the public health impact of this behavior, including the risk of binge-drinking-related harms, which typically increases with the number of drinks consumed8–10; and to plan and evaluate evidence-based binge-drinking prevention programs and policies in states and communities.11

The objectives of this study are, therefore, to use a new measure of binge drinking among U.S. adults—total binge drinks—to assess disparities in binge drinking and the public health impact of this behavior at the state and national levels.

METHODS

Study Sample

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a state-based, random-digit-dial landline and cellular telephone survey of noninstitutionalized, civilian U.S. adults aged ≥18 years that is conducted monthly in all states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. BRFSS collects data on leading health conditions and risk behaviors, including binge drinking. States conduct telephone interviews during each calendar month, thus yielding a representative sample for the entire year. Details of the sampling, purpose, and analysis of BRFSS data have been published previously.12

The median BRFSS survey response rate for all states, territories, and District of Columbia, in 2015 was 47.1% (range, 33.9% —61.1%).13 After excluding people with missing information on binge drinking (n=29,582, 5.8%), age (n=4,213, 1.0%), and respondents from U.S. territories, data from 408,800 respondents in the 50 states and District of Columbia were used in the analysis (conducted in 2016), including respondents aged 18–20 years who are under the legal drinking age.

Measures

BRFSS includes four questions assessing alcohol consumption during the past 30 days: (1) number of drinking days, (2) average number of drinks consumed during days in which alcohol was consumed, (3) number of binge-drinking episodes, and (4) largest number of drinks consumed on any one occasion. Current drinking was defined as consumption of one or more drinks of any alcoholic beverage during the past 30 days. Binge drinking was defined as women consuming four or more drinks, and men consuming five or more drinks per drinking occasion. Heavy drinking was defined as women consuming eight or more drinks/week or men consuming ≥15 drinks/week14 Average annual number of binge-drinking episodes among binge drinkers was calculated by multiplying the frequency of binge-drinking episodes reported during the past 30 days by 12. Because BRFSS interviews a representative sample of state residents each month,12 combining monthly estimates of binge-drinking episodes among BRFSS respondents who reported binge drinking, yields a representative sample for the entire year, and accounts for seasonal variations in binge-drinking frequency. The total number of annual binge-drinking episodes was then calculated by summing the annual number of binge-drinking episodes among all binge drinkers. Among binge drinkers, binge-drinking intensity was assessed by using the largest number of drinks consumed during any occasion in the past 30 days. Total annual binge drinks was calculated by multiplying the total annual binge-drinking episodes by binge-drinking intensity of each binge drinker. Total binge drinks consumed per adult was calculated by dividing total annual binge drinks by the weighted population estimate of U.S. adults. Finally, total binge drinks consumed per binge drinker was calculated by dividing total annual binge drinks by the weighted population estimate of U.S. binge drinkers.

Statistical Analysis

Binge-drinking prevalence, frequency, intensity, and total annual binge drinks among U.S. adults and per binge drinker were assessed overall and by sociodemographic characteristics for the U.S. and by state. Binge drinking among U.S. adults who consumed alcohol was stratified by sex, sociodemographic characteristics (age group, race/ethnicity, education level, annual household income), and drinking patterns.

The data were weighted to each state’s adult population and to the respondent’s probability of selection.15 SAS-callable SUDAAN software, release 11.0.0 with SAS, version 9.3, were used to account for the complex sampling design of BRFSS and to calculate weighted estimates of binge-drinking prevalence, the number of binge drinkers, average annual frequency of binge-drinking episodes, and the binge-drinking intensity per binge episode, as well as 95% CIs for the prevalence of binge drinking. To identify statistically significant differences in binge-drinking prevalence within demographic groups t-tests were used (p<0.05). Binge-drinking prevalence was age-adjusted to the 2000 projected U.S. population16 both overall and among groups of respondents stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, education, household income, heavy drinking status, and state.

RESULTS

In 2015, a total of 17.1% of all U.S. adults (37.4 million) reported binge drinking (Table 1). Each binge drinker reported an average of 53.1 binge-drinking episodes annually, or about one episode per week. This resulted in a total of 1.9 billion episodes of binge drinking annually, or an average of 8.4 binge-drinking episodes per U.S. adult per year. Adult binge drinkers also consumed an average of 7.0 drinks per binge-drinking episode. As a result, there were 17.5 billion total binge drinks consumed annually, or 76.6 total binge drinks per U.S. adult per year.

Table 1.

Binge-drinking Prevalence,a,b Frequency,c Intensity,d and Total Binge Drinkse Among Adults Aged >18 Years,f by Selected Characteristics, U.S.,g 2015

| Characteristics | Sample size, n | Binge-drinking prevalence, % (95% CI) | Weighted total population of binge drinkers | Frequency of binge-drinking episodes among binge drinkers, n (95% CI) | Total annual binge-drinking episodesh | Binge-drinking intensity among binge drinkers, n (95% CI) | Total annual binge drinks | Total binge drinks per adult |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 404,800 | 17.1 (16.9, 17.4) | 37,445,243 | 53.1 (51.8, 54.4) | 1,914,250,943 | 7.0 (6.9, 7.1) | 17,487,732,196 | 76.6 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 170,957 | 22.2 (21.9, 22.6) | 24,086,058 | 59.7 (57.9, 61.4) | 1,378,146,019 | 8.0 (7.9, 8.1) | 13,985,243,459 | 126.4 |

| Women | 233,843 | 12.1 (11.8, 12.4) | 13,359,185 | 40.8 (39.4, 42.3) | 536,104,923 | 5.3 (5.2, 5.3) | 3,502,488,736 | 29.8 |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 18–24 years | 21,887 | 25.1 (24.2, 26.1) | 7,352,722 | 47.7 (45.2, 50.2) | 350,668,989 | 8.3 (8.1, 8.6) | 3,657,207,174 | 124.9 |

| 25–34 years | 38,919 | 25.7 (24.9, 26.4) | 10,190,154 | 46.8 (44.3, 49.2) | 476,447,257 | 7.8 (7.6, 8.0) | 4,824,906,952 | 121.5 |

| 35–44 years | 46,443 | 19.6 (19.0, 20.3) | 7,279,466 | 50.1 (47.4, 52.7) | 364,479,489 | 7.3 (7.1, 7.4) | 3,348,140,167 | 90.4 |

| 45–64 years | 154,820 | 13.7 (13.3, 14.0) | 10,509,977 | 56.2 (54.1, 58.3) | 590,817,927 | 6.5 (6.4, 6.7) | 4,738,388,745 | 61.6 |

| >65 years | 142,731 | 4.6 (4.4, 4.9) | 2,112,925 | 62.4 (57.8, 67.0) | 131,837,281 | 5.7 (5.5, 5.9) | 919,089,157 | 20.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Whites, non-Hispanic | 316,507 | 19.2 (18.9, 19.5) | 25,178,519 | 54.0 (52.6, 55.3) | 1,325,569,876 | 7.1 (7.0, 7.2) | 12,253,593,176 | 83.2 |

| Blacks, non-Hispanic | 30,975 | 13.0 (12.3, 13.8) | 3,384,546 | 52.2 (47.6, 56.9) | 172,736,838 | 6.3 (6.1, 6.6) | 1,343,075,786 | 51.8 |

| Hispanics | 27,564 | 16.0 (15.3, 16.7) | 6,055,502 | 46.9 (41.3, 52.6) | 266,068,476 | 6.9 (6.7, 7.2) | 2,442,794,941 | 70.9 |

| American Indians/ Alaska Natives | 5,992 | 17.9 (15.7, 20.4) | 392,230 | 77.7 (56.0, 99.3) | 26,883,978 | 7.8 (7.1, 8.4) | 225,073,872 | 100.5 |

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | 9,077 | 10.0 (8.9, 11.1) | 1,270,693 | 50.2 (56.0, 99.3) | 51,642,021 | 6.5 (5.3, 7.8) | 436,207,300 | 39.2 |

| Education level | ||||||||

| <High school diploma | 30,105 | 14.0 (13.2, 14.9) | 4,109,555 | 66.3 (60.4, 72.2) | 270,351,407 | 8.2 (7.8, 8.5) | 2,973,342,420 | 94.1 |

| High school diploma | 112,103 | 17.4 (16.9, 17.9) | 10,362,055 | 60.0 (57.5, 62.5) | 609,174,728 | 7.4 (7.2, 7.5) | 5,790,769,522 | 90.6 |

| Some college | 111,418 | 17.5 (17.0, 18.0) | 12,363,435 | 52.2 (49.9, 54.6) | 608,537,620 | 6.9 (6.8, 7.1) | 5,311,411,583 | 74.2 |

| College graduate | 150,236 | 19.0 (18.6, 19.5) | 10,561,742 | 42.0 (40.6, 43.4) | 423,876,739 | 6.3 (6.2, 6.4) | 3,402,064,818 | 56.0 |

| Annual household income | ||||||||

| <$25,000 | 88,134 | 14.1 (13.6, 14.6) | 7,392,019 | 61.2 (57.6, 64.8) | 418,440,991 | 7.2 (7.0, 7.4) | 3,934,615,131 | 73.6 |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 86,078 | 17.4 (16.9, 18.0) | 7,678,760 | 54.9 (52.1, 57.6) | 409,284,139 | 7.1 (7.0, 7.3) | 3,912,209,130 | 83.5 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 55,580 | 19.4 (18.7, 20.2) | 5,573,948 | 53.6 (50.1, 57.1) | 283,371,160 | 7.2 (7.0, 7.4) | 2,536,861,342 | 84.8 |

| >$75,000 | 110,408 | 21.7 (21.1, 22.2) | 13,174,928 | 48.0 (45.8, 50.2) | 610,115,567 | 6.9 (6.8, 7.0) | 5,520,266,456 | 87.4 |

| Heavy drinkers | ||||||||

| Yes | 20,964 | 77.8 (76.8, 78.7) | 10,125,470 | 105.8 (102.0, 109.0) | 1,067,347,054 | 9.1 (8.9, 9.3) | 11,503,953,017 | 895.8 |

| No | 180,193 | 25.2 (24.8, 25.7) | 26,320,767 | 29.5 (28.9, 30.2) | 768,417,851 | 6.2 (6.1, 6.2) | 5,418,241,212 | 51.8 |

Age-adjusted to 2000 U.S. projected population (distribution #916), except for age-specific results.

Total number of respondents who reported at least one binge-drinking episode during the past 30 days divided by the total number of respondents.

Average number of binge-drinking episodes reported by all binge drinkers.

Average largest number of drinks consumed by binge drinkers on any occasion during the past 30 days.

Total binge drinks was calculated by multi plying the frequency of binge drinking (I.e., total annual number of binge-drinking episodes) by the binge-drinking Intensity of each binge drinker (I.e., the largest number of drinks consumed by binge drinkers on any occasion). Total binge drinks per adult was calculated by dividing total binge drinks by the weighted total population.

Including respondents aged 18–20 years who are under the legal drinking age.

Respondents were from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Total number of annual binge-drinking episodes was calculated by summing the annual number of binge-drinking episodes among all binge drinkers.

The prevalence of binge drinking among men (22.2%) was about twice that of women (12.1%, p<0.0001), and men accounted for 72% (1.4 billion) of the total annual binge-drinking episodes in 2015. Men also consumed an estimated 14.0 billion (80%) of the 17.5 billion total binge drinks in 2015. Although the prevalence of binge drinking was significantly higher among those aged 18–24 years (25.1%) and 25–34 years (25.7%) compared with older age groups (p < 0.0001), more than half (9.0 billion) of the total binge drinks were consumed by those aged ≥35 years. The prevalence of binge drinking was significantly higher among non-Hispanic whites (19.2%) and American Indians/Alaska Natives (17.9%) compared with other race/ethnicity groups (p< 0.0001). Non-His-panic whites also accounted for most (73%) of the total binge drinks consumed. However, American Indians/ Alaska Natives had the highest annual number of total binge drinks (100.5 binge drinks/adult). Adults with less than a high school education had significantly lower prevalence of binge drinking (14.0%) compared with college graduates (19.0%, p< 0.0001), but they reported consuming 1.7 times the annual number of total binge drinks (94.1 vs 56.0 binge drinks/adult). Respondents with a household income < $25,000 also had a significantly lower prevalence of binge drinking (14.1%) than those with a household income ≥$75,000 (21.7%, p< 0.0001), and consumed fewer total annual binge drinks (73.6 binge drinks/adult) than those with a household income ≥$75,000 (87.4 binge drinks/adult). Finally, heavy drinkers (i.e., those reporting high weekly alcohol consumption) reported much higher binge-drinking prevalence (77.8%) than non-heavy drinkers (25.2%, p<0.0001). Heavy drinkers also reported an average of 105.8 binge-drinking episodes annually (or about two episodes/week) and consumed an average of 9.1 drinks per binge-drinking episode, resulting in 11.5 billion (68%) of the total annual binge drinks consumed.

Among current drinkers, 31.4% reported at least one episode of binge drinking in the past 30 days and current drinkers who reported binge drinking consumed an average of 467.0 binge drinks per year (Table 2). The prevalence of binge drinking among current drinkers was higher among those aged 18–24 years (49.7%) and 25–34 years (41.8%), and then gradually decreased with increasing age (p< 0.0001). However, binge drinkers aged ≥65 years reported consuming an average of 435.0 total binge drinks annually, even though the prevalence of binge drinking among current drinkers in this age group was substantially lower (11.4%, p< 0.0001) than in other age groups. Over half (55.2%) of adult male drinkers aged 1824 years also reported binge drinking, and these binge drinkers reported consuming an average of 621.0 total binge drinks annually. Among both men and women who were current drinkers, the prevalence of binge drinking and total binge drinks consumed annually decreased with increased education and household income. Binge drinkers with less than a high school education consumed over twice as many total binge drinks annually as binge drinkers who were college graduates (723.5 vs 322.1 drinks, respectively), and binge drinkers with household incomes <$25,000 reported 21% more total binge drinks annually than binge drinkers with household incomes of ≥$75,000 (532.3 vs 419.0 drinks, respectively). Men who reported heavy drinking (i.e., consuming >15 drinks/ week) reported an average of 1,533.1 binge drinks/year, or about 29 binge drinks/week.

Table 2.

| Characteristics | Total (n=203,752) | Males (n=99,178) | Females (n=104,574) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge-drinking prevalencec among current drinkers,d % (95% CI) | Total annual binge drinks per current drinkere | Total annual binge drinks per binge drinkere | Binge-drinking prevalencec among current drinkers,’ % (95% CI) | Total annual binge drinks per Current drinkere | Total annual binge drinks per Binge drinkerf | Binge-drinking prevalencec among current drinkers,d % (95% CI) | Total annual binge drinks per Current drinkere | Total annual binge drinks per binge drinkerf | ||

| Total | 31.4 (31.0, 31.8) | 146.6 | 467.0 | 36.8 (36.2, 37.4) | 215.4 | 580.6 | 24.8 (24.3, 25.4) | 64.5 | 262.2 | |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 18–24 years | 49.7 (48.2, 51.2) | 247.2 | 497.4 | 55.2 (53.2, 57.1) | 342.5 | 621.0 | 43.2 (40.9, 45.4) | 132.9 | 307.9 | |

| 25–34 years | 41.8 (40.8, 42.9) | 198.0 | 473.5 | 48.1 (46.7, 49.6) | 282.5 | 587.0 | 33.6 (32.2, 35.0) | 88.2 | 262.3 | |

| 35–44 years | 34.6 (33.6, 35.6) | 159.1 | 459.9 | 41.2 (39.8, 42.6) | 238.2 | 578.2 | 26.4 (25.1, 27.7) | 60.9 | 230.7 | |

| 45–64 years | 26.0 (25.4, 26.6) | 117.1 | 450.8 | 31.3 (30.5, 32.2) | 174.3 | 556.1 | 19.7 (19.0, 20.5) | 50.9 | 257.7 | |

| >65 years | 11.4 (10.8, 11.9) | 49.4 | 435.0 | 14.4 (13.6, 15.3) | 79.3 | 550.2 | 8.0 (7.4, 8.7) | 16.6 | 207.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Whites, non-Hispanic | 31.9 (31.5, 32.4) | 147.6 | 486.7 | 37.4 (36.8, 38.0) | 221.2 | 610.8 | 25.5 (24.9, 26.1) | 63.9 | 270.4 | |

| Blacks, non-Hispanic | 28.3 (26.9, 29.7) | 116.4 | 396.8 | 33.2 (31.1, 35.4) | 166.4 | 491.8 | 23.0 (21.2, 24.8) | 63.3 | 258.0 | |

| Hispanics | 35.8 (34.3, 37.3) | 158.5 | 403.4 | 41.3 (39.3, 43.3) | 217.9 | 482.4 | 26.9 (24.8, 29.1) | 63.7 | 212.9 | |

| American | 43.7 (39.4, 48.2) | 256.3 | 573.8 | 50.0 (44.5, 55.6) | 396.9 | 783.8 | 34.5 (28.5, 41.1) | 62.2 | 170.6 | |

| Indians/ | ||||||||||

| Alaska | ||||||||||

| Natives | ||||||||||

| Asian/Pacific | 22.3 (20.1, 24.6) | 90.2 | 343.3 | 24.9 (22.0, 28.0) | 124.2 | 436.2 | 18.3 (15.4, 21.6) | 43.1 | 185.6 | |

| Islanders | ||||||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||

| <High school diploma | 40.5 (38.6, 42.3) | 296.5 | 723.5 | 45.3 (43.0, 47.6) | 392.9 | 851.8 | 30.7 (27.9, 33.7) | 107.1 | 346.7 | |

| High school diploma | 36.0 (35.1, 36.8) | 200.8 | 558.8 | 41.6 (40.4, 42.7) | 284.1 | 666.6 | 27.5 (26.2, 28.8) | 82.4 | 311.7 | |

| Some college | 30.4 (29.6, 31.1) | 134.1 | 429.6 | 35.8 (34.8, 36.9) | 199.6 | 535.1 | 24.5 (23.5, 25.5) | 64.9 | 261.9 | |

| College | 27.2 (26.6, 27.8) | 83.8 | 322.1 | 31.6 (30.7, 32.4) | 119.4 | 403.9 | 22.8 (22.1, 23.5) | 46.0 | 206.9 | |

| graduate | ||||||||||

| Annual household income | ||||||||||

| <$25,000 | 34.7 (33.7, 35.7) | 194.0 | 532.3 | 40.9 (39.4, 42.4) | 282.7 | 664.1 | 27.9 (26.6, 29.3) | 99.7 | 333.1 | |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 33.0 (32.0, 33.9) | 165.8 | 509.5 | 38.8 (37.4, 40.1) | 240.9 | 626.2 | 25.6 (24.4, 26.9) | 73.0 | 289.5 | |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 31.7 (30.6, 32.8) | 142.1 | 455.1 | 37.8 (36.3, 39.4) | 209.3 | 557.0 | 24.0 (22.5, 25.5) | 57.8 | 248.8 | |

| >$75,000 | 31.6 (30.9, 32.3) | 126.8 | 419.0 | 36.5 (35.6, 37.5) | 185.8 | 525.1 | 25.0 (24.0, 26.1) | 49.8 | 211.2 | |

| Heavy drinkers | ||||||||||

| Yes | 77.8 (76.8, 78.7) | 895.8 | 1,136.1 | 86.3 (85.1, 87.3) | 1,341.1 | 1,533.1 | 68.5 (66.9, 70.1) | 386.1 | 559.8 | |

| No | 25.2 (24.8, 25.7) | 51.8 | 205.9 | 30.4 (29.9, 31.0) | 76.6 | 250.0 | 18.9 (18.4, 19.5) | 22.2 | 119.2 | |

Including respondents aged 18–20 years who are under the legal drinking age.

Respondents were from all 50 states and the District of Columbia

Age-adjusted to 2000 U.S. projected population (distribution #916), except for age-specific results.

Total number of respondents who reported at least one binge-drinking episode during the past 30 days divided by the total number of respondents reporting consumption of ≥1 drinks of any alcoholic beverage during the past 30 days.

Total annual binge drinks per current drinker was calculated by multiplying the frequency of binge drinking (i.e., total annual number of binge-drinking episodes) by the binge-drinking intensity of each binge drinker (i.e., the largest number of drinks consumed by binge drinkers on any occasion), then dividing by the weighted total population of current drinkers.

Total annual binge drinks per binge drinker was calculated by multiplying the frequency of binge drinking (i.e., total annual number of binge-drinking episodes) by the binge-drinking intensity of each binge drinker (i.e., the largest number of drinks consumed by binge drinkers on any occasion), then dividing by the weighted total population of binge drinkers.

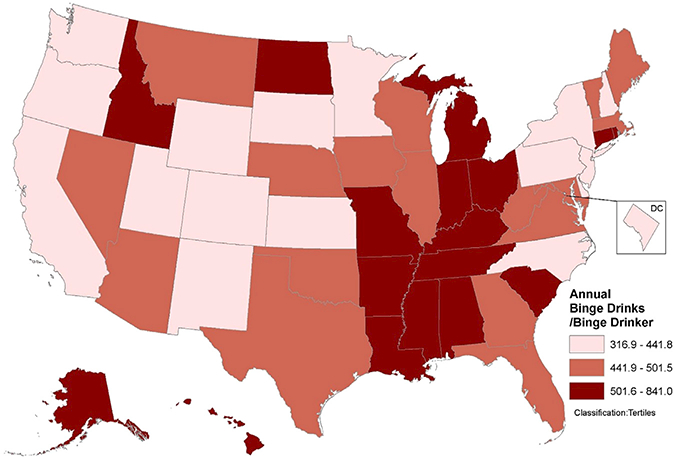

In 2015, the total annual binge drinks per adult in the states ranged from 46.2 in Utah to 128.9 in North Dakota, while the total annual binge drinks per binge drinker ranged from 316.9 in the District of Columbia to 841.0 in Arkansas (Table 3). The highest annual number of total binge drinks per binge drinker was reported in Arkansas (841.0), Mississippi (831.8), Kentucky (652.8), and Hawaii (611.7). Notably, total annual binge drinks per binge drinker (Figure 1) and per adult (Appendix Figure 1, available online) were generally higher in the Mississippi River Valley than in other regions. By contrast, age-adjusted binge-drinking prevalence was generally higher in the Midwest and New England than in other regions (Appendix Figure 2, available online).

Table 3.

Binge-drinking Prevalence,a,b Frequency,c Intensity,d and Total Binge Drinkse Among Adults Aged >18 Yearsf by State, U.S., 2015

| State | Binge-drinking prevalence, % (95% CI) | Frequency of binge-drinking episodes among binge drinkers | Total annual bingedrinking episodesg | Binge drinking intensity | Total annual binge drinks | Total annual binge drinks per adult | Total annual binge drinks per binge drinker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 12.2(11.1,13.5) | 59.8 | 23,217,261 | 7.3 | 215,130,596 | 57.3 | 525.3 |

| Alaska | 20.0(17.8, 22.3) | 56.4 | 5,656,725 | 7.8 | 62,353,929 | 112.9 | 594.2 |

| Arizona | 15.0(13.7,16.4) | 56.9 | 36,815,789 | 7.1 | 332,224,029 | 63.8 | 483.4 |

| Arkansas | 15.2(13.1,17.4) | 69.6 | 20,791,529 | 8.3 | 253,486,160 | 111.5 | 841.0 |

| California | 16.7 (15.9,17.6) | 48.0 | 202,969,409 | 6.5 | 1,744,778,272 | 58.1 | 391.8 |

| Colorado | 18.1(16.9,19.3) | 48.6 | 32,082,519 | 6.6 | 282,191,317 | 67.2 | 423.8 |

| Connecticut | 18.3(17.1,19.5) | 55.2 | 23,497,017 | 7.0 | 258,815,692 | 91.6 | 593.6 |

| Delaware | 15.8(13.9,17.8) | 48.6 | 5,168,982 | 7.0 | 43,135,014 | 58.2 | 412.8 |

| District of Columbia | 24.4(21.8, 27.3) | 46.1 | 5,576,820 | 6.2 | 43,879,257 | 79.2 | 316.9 |

| Florida | 17.2(15.9,18.6) | 52.1 | 118,113,079 | 6.8 | 1,037,830,998 | 64.2 | 453.1 |

| Georgia | 15.8(14.2,17.5) | 58.4 | 63,065,616 | 6.9 | 514,273,516 | 66.7 | 466.8 |

| Hawaii | 19.8(18.3, 21.3) | 65.1 | 12,160,323 | 7.6 | 120,381,961 | 107.4 | 611.7 |

| Idaho | 14.8(13.4,16.5) | 58.1 | 8,630,314 | 7.4 | 82,338,810 | 67.4 | 504.8 |

| Illinois | 20.8(19.3, 22.4) | 50.6 | 94,986,862 | 7.1 | 866,676,037 | 87.5 | 453.2 |

| Indiana | 16.6(15.0,18.2) | 53.1 | 39,397,102 | 7.2 | 404,893,463 | 80.3 | 541.3 |

| Iowa | 21.3(19.8, 22.9) | 55.1 | 21,842,807 | 7.6 | 202,142,522 | 84.4 | 449.2 |

| Kansas | 16.5(15.8,17.2) | 54.4 | 15,910,168 | 7.0 | 135,312,443 | 61.7 | 428.8 |

| Kentucky | 16.1(14.6,17.7) | 72.8 | 32,975,801 | 7.8 | 321,470,006 | 94.2 | 652.8 |

| Louisiana | 18.0(16.3,19.7) | 58.4 | 30,947,527 | 7.6 | 303,589,086 | 85.4 | 543.9 |

| Maine | 20.2(18.7, 21.8) | 57.5 | 9,829,393 | 7.4 | 88,357,485 | 82.4 | 489.5 |

| Maryland | 14.7 (13.2, 16.3) | 59.3 | 33,973,891 | 6.6 | 272,678,552 | 58.5 | 444.5 |

| Massachusetts | 18.7 (17.5, 20.0) | 52.7 | 47,288,417 | 6.5 | 417,282,007 | 77.2 | 488.3 |

| Michigan | 19.8(18.7, 21.1) | 60.3 | 77,429,336 | 7.3 | 775,554,320 | 100.5 | 575.8 |

| Minnesota | 20.5(19.7, 21.4) | 47.8 | 36,321,935 | 7.2 | 325,795,877 | 77.5 | 419.3 |

| Mississippi | 12.5(11.1,14.1) | 64.3 | 16,661,059 | 7.6 | 210,378,008 | 92.9 | 831.8 |

| Missouri | 17.7 (16.2,19.2) | 64.5 | 43,445,143 | 7.8 | 397,708,743 | 84.8 | 533.0 |

| Montana | 21.3(19.6, 23.2) | 55.4 | 8,150,629 | 7.2 | 67,490,635 | 83.7 | 445.6 |

| Nebraska | 20.4(19.3, 21.5) | 50.3 | 12,763,532 | 7.2 | 118,457,501 | 83.1 | 447.5 |

| Nevada | 14.5(12.4,16.9) | 64.7 | 15,837,027 | 7.2 | 137,824,102 | 62.0 | 468.6 |

| New | 17.8(16.2,19.5) | 49.8 | 8,245,356 | 6.4 | 70,267,911 | 65.9 | 425.6 |

| Hampshire | |||||||

| New Jersey | 17.0(15.7,18.4) | 43.2 | 44,184,772 | 6.9 | 366,271,396 | 52.6 | 354.9 |

| New Mexico | 13.6(12.1,15.2) | 49.8 | 9,151,667 | 7.2 | 82,012,459 | 51.6 | 425.9 |

| New York | 17.6(16.6,18.7) | 47.9 | 107,790,058 | 6.8 | 875,103,091 | 56.2 | 369.8 |

| North Carolina | 14.6(13.5,15.7) | 52.1 | 50,169,400 | 6.4 | 424,768,408 | 54.8 | 422.6 |

| North Dakota | 24.9(23.1, 26.7) | 50.5 | 6,746,882 | 7.7 | 75,169,030 | 128.9 | 564.3 |

| Ohio | 19.5(18.1, 21.0) | 51.4 | 77,616,428 | 7.7 | 919,978,898 | 102.4 | 591.7 |

| Oklahoma | 13.6(12.3,15.1) | 62.5 | 20,239,289 | 7.5 | 178,841,984 | 60.6 | 493.2 |

| Oregon | 17.7 (16.2,19.2) | 52.0 | 24,832,806 | 6.3 | 186,307,663 | 58.8 | 384.6 |

| Pennsylvania | 18.5(17.0, 20.0) | 48.9 | 76,331,864 | 7.0 | 706,904,786 | 69.9 | 441.8 |

| Rhode Island | 17.0(15.4,18.8) | 54.0 | 6,370,912 | 7.0 | 63,035,011 | 74.6 | 504.9 |

| South Carolina | 16.3(15.3,17.5) | 61.9 | 32,140,181 | 7.4 | 305,869,730 | 80.4 | 561.7 |

| South Dakota | 17.9(16.3,19.6) | 47.0 | 4,963,768 | 7.6 | 43,633,055 | 67.4 | 416.6 |

| Tennessee | 10.9 (9.5, 12.4) | 63.9 | 30,964,037 | 7.0 | 249,954,016 | 49.0 | 509.8 |

| Texas | 16.1(14.9,17.3) | 51.7 | 150,284,697 | 7.2 | 1,386,402,139 | 68.4 | 472.8 |

| Utah | 11.4(10.7,12.2) | 55.9 | 11,610,783 | 7.3 | 96,298,123 | 46.2 | 418.2 |

| Vermont | 19.0 (17.6, 20.6) | 55.2 | 4,432,492 | 6.8 | 41,339,473 | 81.7 | 501.5 |

| Virginia | 17.0 (15.8,18.2) | 52.5 | 51,026,215 | 7.1 | 488,627,713 | 75.0 | 483.9 |

| Washington | 16.6 (15.7,17.5) | 50.1 | 40,870,916 | 6.2 | 316,195,086 | 56.9 | 378.3 |

| West Virginia | 11.8 (10.7,13.1) | 53.2 | 7,822,466 | 7.9 | 74,714,179 | 51.0 | 500.5 |

| Wisconsin | 24.4 (22.7, 26.2) | 51.3 | 49,266,263 | 7.2 | 471,484,200 | 105.3 | 488.4 |

| Wyoming | 16.9 (15.1, 18.9) | 56.7 | 3,683,677 | 7.0 | 28,123,508 | 62.9 | 413.9 |

Age-adjusted to 2000 U.S. projected population (distribution #916).

Total number of respondents who reported at least one binge-drinking episode during the past 30 days divided by the total number of respondents.

Average number of binge-drinking episodes reported by all binge drinkers.

Average largest number of drinks consumed by binge drinkers on any occasion during the past 30 days.

Total annual binge drinks was calculated by multiplying the frequency of binge drinking (i.e., total annual number of binge-drinking episodes) by the binge-drinking intensity of each binge drinker (i.e., the largest number of drinks consumed by binge drinkers on any occasion). Total annual binge drinks per adult was calculated by dividing total binge drinks by the weighted total population. Total annual binge drinks per binge drinker was calculated by dividing total annual binge drinks by the weighted total population of binge drinkers.

Including respondents aged 18–20 years who are under the legal drinking age.

Figure 1.

Total annual binge drinks per binge drinkera aged ≥18 years by state, U.S., 2015.

aCalculated by dividing the state-specific summation of total annual binge drinks by the estimated number of binge drinkers in each state. Total annual binge drinks was calculated as the number of annual binge-drinking episodes multiplied by the binge-drinking intensity (i.e., the average largest number of drinks consumed on any occasion in the past 30 days for each binge drinker).

DISCUSSION

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to assess total binge drinks consumed by U.S. adults, using a new measure to assess disparities in binge drinking. Adult binge drinkers are doing so frequently and with great intensity, resulting in about 17.5 billion total binge drinks in 2015, significantly increasing the risk for alcohol-attributable harms to themselves and others. Although binge drinking was most common among young adults aged 18–34 years, most of the total binge drinks were consumed by those aged >25 years, and over half were consumed by adults aged ≥35 years, underscoring that binge drinking is a problem across the lifespan. In addition, four of five total binge drinks were consumed by men. Binge drinking was also significantly more common among people with higher educational attainment and household incomes. However, the total annual number of binge drinks per binge drinker was substantially higher among those with lower educational levels and household incomes than among those with higher educational levels and household incomes, emphasizing the usefulness of total binge drinks for assessing disparities in binge drinking. States with higher total binge drinks per binge drinker per year were also widely distributed across geographic regions in the U.S.

The finding that over three quarters of total binge drinks were consumed by adults aged ≥25 years is consistent with the findings of a previous study that found about 70% of binge-drinking episodes were reported by those aged ≥26 years.17 This finding is also consistent with the age distribution of alcohol-attributable deaths in the U.S. About 95% of the 88,000 average annual alcohol-attributable deaths in the U.S. involve adults aged ≥21 years,1 and three quarters of the 2,200 average annual alcohol-poisoning deaths in the U.S., which typically are caused by binge drinking at high intensity, involve adults aged 35–64 years.10

The observed disparities in total binge drinks by race/ ethnicity and SES also reflects known disparities in alcohol-attributable outcomes and life expectancy. For example, non-Hispanic whites, who reported almost three quarters of the total binge drinks, account for the majority of alcohol poisoning deaths in the U.S. However, American Indians/Alaska Natives, who had the highest total binge drinks per binge drinker per year (573.8 binge drinks annually), have the highest age-adjusted alcohol poisoning death rate in the U.S.10 Similarly, the substantially higher rate of total binge drinks per binge drinker per year for those with less than a high school education and household incomes of <$25,000 relative to college graduates and those with household incomes of ≥$75,000, respectively, may help explain reported differences in life expectancy by SES,18 particularly because excessive drinking (including binge drinking) is responsible for one in ten total deaths among working-age adults aged 20–64 years in the U.S.1 This emphasizes the importance of reducing total binge drinks in order to reduce health disparities, including differences in mortality, among adults by race/ethnicity and SES.

Most heavy drinkers (i.e., those reporting high weekly alcohol consumption), especially men, were found to binge drink frequently and at high intensity, as reflected by the high rate of total binge drinks per binge drinker per year. The substantial overlap between these two patterns of alcohol consumption highlights the usefulness of a single-question screen for identifying excessive drinkers in clinical settings.19 Alcohol screening with a brief intervention has been shown to be an effective strategy for reducing excessive drinking in clinical settings.20 In addition, a recent systematic review found that providing screening and brief intervention for excessive drinking using electronic tools (e.g., computers and cell phones) can reduce binge-drinking intensity by 24% among those participating in these interventions.21

The observed differences in the prevalence of binge drinking and total binge drinks in states reflect, in part, differences in state alcohol policies.22 A recent study that examined the relationship between various subgroups of state alcohol policies and binge drinking among adults found that a small number of alcohol policies that raised alcohol prices and reduced its availability had the greatest impact on binge drinking.23 However, these differences probably also reflect other social and cultural factors in states—including racial and ethnic composition, SES, and religious affiliation—that can influence binge drinking as well.24

Previous studies have found that nine in ten adults who binge drink are not alcohol dependent,25 thus, ensuring access to effective treatment will not be sufficient to decrease harms from excessive drinking at the population level. Therefore, strategies to address excessive drinking must also include, in addition to clinically based strategies (e.g., screening and brief interventions), evidence-based policies, such as those recommended by The Community Preventive Services Task Force.11 These include increasing alcohol taxes, regulating alcohol outlet density, and commercial host liability. However, recent reports have shown that these interventions may be underutilized by states relative to their potential effectiveness.26–28 In fact, the total federal and state taxes on alcoholic beverages were about $0.14 per drink (in 2011),29 whereas the economic cost of excessive drinking was about $2.05 per drink (in 2010), and binge drinking is responsible about three quarters of these costs.2 Additionally, recent studies suggest that populations with lower income and educational levels may pay less on a per-capita basis following an alcohol tax increase than populations with higher income and education levels, as they generally have a lower prevalence of current drinking and binge drinking than more affluent populations.30

Limitations

Findings are subject to several limitations. First, BRFSS data are self-reported; alcohol consumption generally, and excessive drinking in particular, is underreported in surveys because of recall bias, social desirability response bias, and nonresponse bias31; these biases could vary among states and by respondent. Second, the median response rate for BRFSS was low, which could increase response bias. Third, the BRFSS measure of the largest number of drinks among binge drinkers may have resulted in higher estimates of binge-drinking intensity than other survey methods because the largest number of binge drinks consumed may be greater than the average number of binge drinks consumed by those who binge drink on multiple occasions.32 However, a recent study found that binge-drinking intensity is quite consistent across binge-drinking episodes among young adults,33 though this has not been assessed among other age groups. BRFSS estimates of binge drinking among adults are also substantially lower than estimates from other surveys,34 and the BRFSS only identifies 22%−32% of presumed alcohol consumption in states based on alcohol sales data.35 In addition, the underreporting of alcohol consumption tends to be greater among binge drinkers than non-binge drinkers, and tends to increase with binge-drinking intensity.36 Therefore, the prevalence, frequency, and intensity of binge drinking are likely to have been substantially underestimated in this study. Additional research is needed to improve survey measures for binge drinking to enhance their usefulness for public health surveillance. Similarly, additional research is needed to assess the prevalence of high-intensity binge drinking across demographic groups, and the relationship between high-intensity binge drinking and various alcohol-attributable harms (e.g., heart disease and cancer).

CONCLUSIONS

To date, binge-drinking prevalence is the most commonly used measure of binge drinking and reducing binge drinking is a leading health indicator in Healthy People 2020.6 However, there are important disparities in binge-drinking behavior that are not apparent based on an assessment of binge-drinking prevalence alone. Monitoring total binge drinks consumed annually and total binge drinks per binge drinker could help overcome some of these limitations, and provide a more sensitive and specific way to plan, implement, and evaluate community and clinical preventive strategies for reducing binge drinking and related harms.

aCalculated by dividing the state-specific summation of total annual binge drinks by the estimated number of binge drinkers in each state. Total annual binge drinks was calculated as the number of annual binge-drinking episodes multiplied by the binge-drinking intensity (i.e., the average largest number of drinks consumed on any occasion in the past 30 days for each binge drinker).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

D Kanny, TS Naimi, and RD Brewer conceptualized the study and D Kanny led the drafting of the article. Y Liu performed data analysis and H Lu preformed GIS mapping. All authors contributed to the interpreted findings, reviewed and edited drafts of the article, and approved the final version.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.12.021.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev ChronicDis. 2014;11:130293 https://doi.org/ 10.5888/pcd11.130293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 National and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49 (5):e73–e79. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsl. 2004;3:3 http:// pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_ Number3.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health—2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/ 112736/1/9789240692763_eng.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerr WC, Mulia N, Zemore SE. U.S. trends in light, moderate, and heavy drinking episodes from 2000 to 2010. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(9):2496–2501. 10.1m/acer.12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Substance abuse. SA-14.3 Reduce the proportion of persons engaging in binge drinking during the past 30 days—adults aged 18 years and older. https://www. healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/substance-abuse/objec tives#5205. Accessed November 30, 2017.

- 7.Kanny D, Liu Y, Brewer RD, Lu H. Binge drinking—United States, 2011. MMWR Suppl 2013;62(3):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinson DC, Maclure M, Reidinger C, Smith GS. A population-based case-crossover and case-control study of alcohol and the risk of injury. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(3):358–366. 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkin DM. Cancers attributable to consumption of alcohol in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(suppl 2):S14–S18. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2011.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanny D, Brewer RD, Mesnick JB, Paulozzi LJ, Naimi TS, Lu H. Vital signs: alcohol poisoning deaths—United States, 2010–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal WklyRep. 2015;63(53):1238–1242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Task Force on Community Prevention Services. Preventing excessive alcohol consumption In: The Guide to Community Preventive Services. New York, NY: U.S. DHHS; 2005. www.thecommunityguide.org/ alcohol/index.html. Accessed August 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokdad A The Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System: past, present and future. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:43–54. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC. Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System. 2015. Summary Data Quality Report. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2015/pdf/ 2015-sdqr.pdf. Published July 29, 2016 Accessed January 11, 2018.

- 14.U.S. DHHS, U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. Methodologic changes in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 2011 and potential effects on prevalence estimates. MMWR Morb Mortal WklyRep. 2012;61(22):410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 U.S. projected population. Healthy People 2000 Stat Notes. 2001;(20):1–9. www.cdc.gov/ nchs/data/statnt/statnt20.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Clark D, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among U.S. adults. JAMA. 2003;289(1):70–75 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–1766. 10.1001/jama.2016.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NIH, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide, 5th ed., Bethesda, MD: U.S: DHHS; 2005. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/Clinicians Guide2005/clinicians_guide.htm. Accessed August 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR,et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(9): 645–654. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tansil KA, Esser MB, Sandhu P, et al. Alcohol electronic screening and brief intervention: a Community Guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):801–811. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naimi TS, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, et al. A new scale ofthe U.S. alcohol policy environment and its relationship to binge drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):10–16. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xuan Z, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, Heeren T, Oussayef N, Naimi TS.The alcohol policy environment and policy subgroups as predictors of binge drinking measures among U.S. adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):816–822. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt JB, Miller JW, Naimi TS, Sui DZ. Religious affiliation and alcohol consumption in the United States. Geogr Rev. 2006;96(4):523–542. 10.1111/j.1931-0846.2006.tb00515.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esser MB, Hedden SL, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Gfroerer JC, Naimi TS. Prevalence of alcohol dependence among U.S. adult drinkers, 2009–2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:140329 10.5888/pcd11.140329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC. Chronic Disease Indicators (CDI) application. www.cdc.gov/cdi. Published 2015. Accessed August 18, 2017.

- 27.CDC. Prevention Status Report (PSR) 2013: Excessive alcohol use. www. cdc.gov/psr/2013/alcohol/index.html. Accessed August 18, 2017.

- 28.CDC. Prevention Status Report (PSR) 2015: alcohol related harms. www.cdc.gov/psr/. Accessed August 18, 2017.

- 29.Naimi TS. The cost of alcohol and its corresponding taxes in the U.S.: a massive public subsidy of excessive drinking and alcohol industries. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(5):546–547. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naimi TS, Daley JI, Xuan Z, Blanchette JG, Chaloupka FJ, Jernigan DH. Who would pay for state alcohol tax increases in the United States? Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:150450 10.5888/pcd13.150450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stockwell T, Donath S, Cooper-Stanbury M, et al. Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in household surveys: a comparison of quantity-frequency, graduated-frequency and recent recall. Addiction. 2004;99 (8):1024–1033. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esser MB, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Naimi TS. Binge drinking intensity: a comparison of two measures. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):625–629. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reich RR, Cummings JR, Greenbaum PE, Moltisanti AJ, Goldman MS. The temporal “pulse” of drinking: tracking 5 years of binge drinking in emerging adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124(3):635–647. https://doi. org/10.1037/abn0000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller J, Gfroerer J, Brewer RD, Naimi T, Mokdad A, Giles W. Prevalence of adult binge drinking: a comparison of two national surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):197–204. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson DE, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Roeber J. U.S. state alcohol sales compared to survey data, 1993–2006. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1589– 1596. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northcote J, Livingston M. Accuracy of self-reported drinking: observational verification of ‘last occasion’ drink estimates of young adults. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(6):709–713. 10.1093/alcalc/agr138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.