Summary

Sleep is a behavior conserved from invertebrates to vertebrates, and tightly regulated in a homeostatic manner. The molecular and cellular mechanism determining the amount of rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) and non-REMS (NREMS) remains unknown. Here we identified two dominant mutations affecting sleep/wakefulness through an electroencephalogram/electromyogram-based screening of randomly mutagenized mice. A splicing mutation of the Sik3 protein kinase gene causes a profound decrease in total wake time, due to an increase in inherent sleep need. Sleep deprivation affects regulatory-site phosphorylation of the kinase. Sik3 orthologues regulate sleep also in fruit flies and roundworms. A missense mutation of the leak cation channel NALCN reduces the total amount and episode duration of REMS, apparently by increasing the excitability of REMS-inhibiting neurons. Our results substantiate the utility of forward genetic approach for sleep behaviors in mice, demonstrating the role of SIK3 and NALCN in regulating the amount of NREMS and REMS, respectively.

Sleep is an animal behavior ubiquitously conserved from vertebrates to invertebrates including flies and nematodes1–3, and is tightly regulated in a homeostatic manner. Sleep in mammals exhibits the cycles of rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) and non-REMS (NREMS) that are defined by the characteristic activity of electroencephalogram (EEG) and electromyogram (EMG). Time spent in sleep is determined by a homeostatic sleep need, a driving force for sleep/wakefulness switching, which increases during wakefulness and dissipates during sleep4,5. The spectral power in the delta-range frequency (1-4 Hz) of EEG during NREMS has been regarded as one of best markers for the current level of sleep need. On the other hand, the level of arousal is positively correlated with the sleep latency, which can be regulated independently of sleep need6, reflecting the overall activity of wake-promoting neurons. Traditional approaches to locate the neural circuits regulating sleep/wakefulness behavior included local ablation of brain regions7–9. Recent advances in optogenetic and chemogenetic research have directly demonstrated that switching between sleep/wake states is executed by subsets of neurons in the basal forebrain10, lateral hypothalamus11,12 and locus coeruleus13, and that switching between NREMS and REMS is executed by a neural network in the pons and medulla14,15. Despite the accumulating information about executive neural circuitries regulating sleep/wake states, the molecular and cellular mechanisms that determine the propensity of switching between wakefulness, REMS and NREMS remain unknown. To tackle this problem, we have employed a phenotype-driven forward genetic approach that is free from specific working hypotheses16. Previously, a series of forward genetic studies using flies and mice successfully uncovered the molecular network of the core clock genes regulating circadian behaviors17–19. Sleep-regulating genes were also discovered through the screening of mutagenized flies1,2. However, genetic studies for sleep using mice has been challenging because of the effective compensation and redundancy in sleep/wakefulness regulation, and the need of EEG/EMG monitoring for the staging of wakefulness, NREMS and REMS.

Sik3 splice mutation increases NREMS

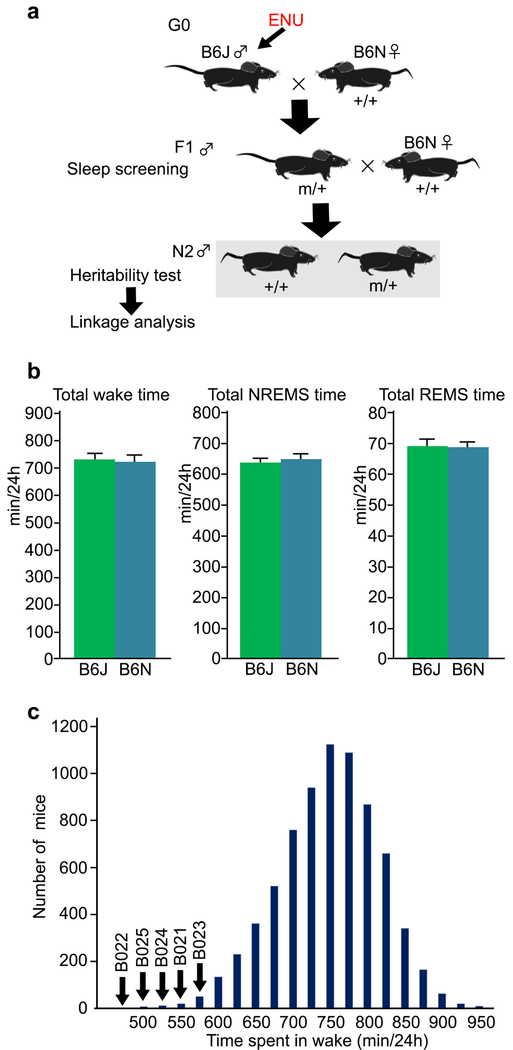

We induced random point mutations in C57BL/6J (B6J) males (G0) by ethylnitrosourea (ENU) and screened more than 8,000 heterozygous B6J x C57BL/6N (B6N) F1 mice for dominant sleep/wakefulness abnormalities through EEG/EMG-based sleep staging (Extended Data Fig. 1a). B6N was chosen as a counter strain because its sleep/wakefulness parameters are highly similar to B6J (Extended Data Fig. 1b), and the entire list of the single nucleotide polymorphisms has recently become available20.

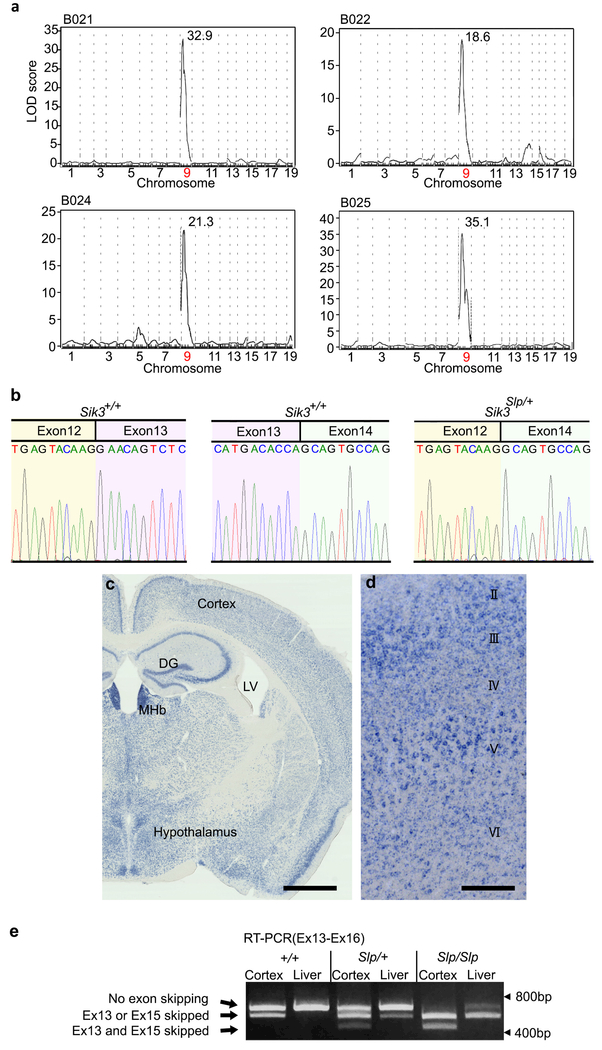

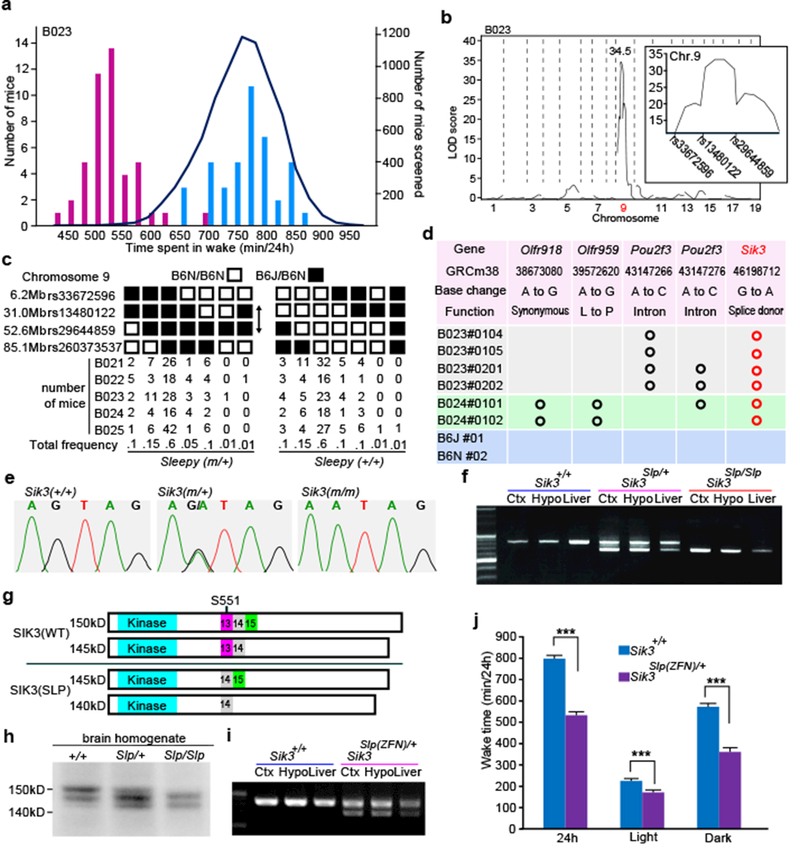

Through our screening, we established a mutant pedigree, termed Sleepy, with a markedly prolonged sleep time. Five founders of the Sleepy mutant pedigree were born by in vitro fertilization using sperm from the same ENU-treated G0 male, and showed daily wake time (524 ± 19.7 min; mean ± SD) which was shorter than the mean of all mice screened by >3 standard deviations (Extended Data Fig. 1c). The Sleepy pedigree showed clear dominant inheritance of reduced wake time (Fig. 1a). Linkage analysis in the B6J x B6N N2 generation of five Sleepy pedigrees (B021-B025) produced a single LOD score peak on chromosome 9 (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 2a), between rs13480122 (chr9: 31156626) and rs29644859 (chr9: 52785119) (Fig. 1b,c). Whole-exome sequencing of Sleepy mutants identified a heterozygous single nucleotide substitution at the splice donor site (chr9: 46198712) for intron 13 of the Sik3 gene (Fig. 1d,e). The mutation predicted an abnormal skipping of exon 13 (Sik3Slp/+), which was confirmed by RT-PCR and sequencing of the Sik3 mRNA (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 2b).

Figure 1 |. Identification of Sik3 splicing mutation responsible for reduced total wake time.

a, Wake time distribution of B023 N2 littermates (bars) and all mice screened (curve). Blue and Purple bars indicates retrospectively genotyped Sik3+/+ and Sik3Slp/+ mice, respectively, b, QTL analysis of B023 pedigree (n = 93) for total wake time. (Inset) LOD score peak between rs13480122 and rs29644859. c, Haplotype analysis of Sleepy mutant pedigrees, B021-B025, in terms of the presence of Sleepy phenotypes, d, Exome sequencing results from Sleepy mutant mice of B023 and B024 pedigrees together with wildtype mice within the region of LOD score peak, e, Direct sequencing of Sik3 gene, f, RT-PCR of Sik3 mRNA produced smaller bands specific to Sik3Slp mice, g, Structures of wildtype and mutant SIK3 proteins, h, Immunoblotting of brain homogenates showing wildtype and mutant SIK3 protein variants, i, RT-PCR of brain mRNA from ZFN-based Sik3Slp/+ mice showing smaller bands lacking exon 13, in addition to larger bands containing the exon 13. j, Sik3Slp(ZFN)/+ mice (n = 15) showed shorter total wake time than wildtype littermates (n = 14). Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *** P < 0.001. Values are means ± sem.

SIK3 is a protein kinase expressed broadly in neurons of the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus and brain stem (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d), and belongs to the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) family. SIK3 has a serine-threonine kinase domain at the N-terminus and a protein kinase A (PKA) recognition site (S551) in the middle portion (Fig. 1g)21. The skipping of exon 13 results in an in-frame deletion of 52 amino acids, encompassing the PKA site (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 2e). Immunoblotting of brain homogenates from Sik3Slp/+ and Sik3Slp/Slp mice using anti-SIK3 antibody detected smaller SIK3 proteins as predicted (Fig. 1g,h). The nature of this mutation, taken together with our results on SIK3 orthologues in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans (see below), suggests that Sik3Slp is a gain-of-function allele.

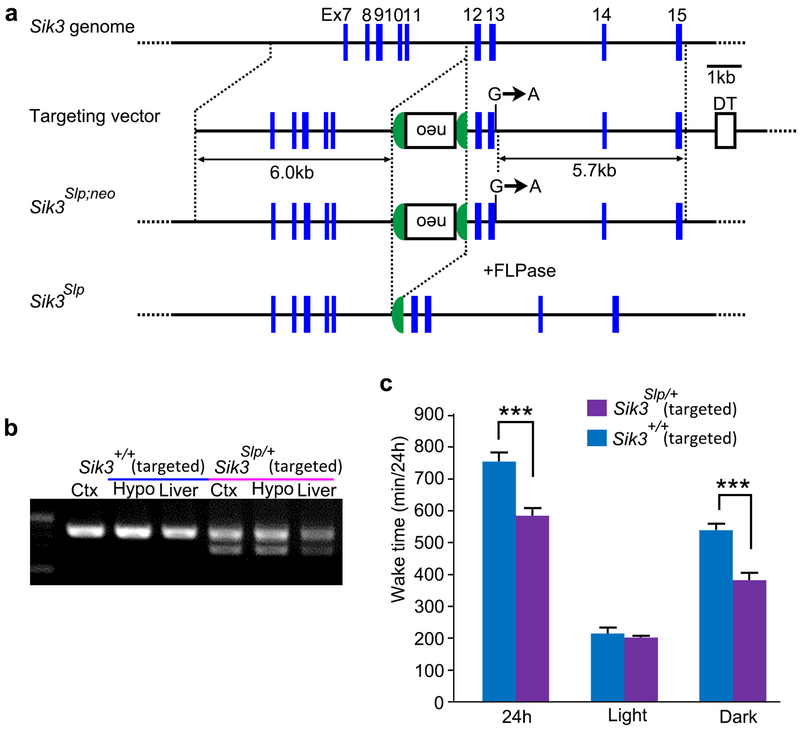

To genetically confirm that the Sik3 splice mutation is the sole cause of the long-sleep phenotype, we introduced the Sik3 exon 13-skipping allele in wildtype mice by using either the conventional knock-in in ES cells or the zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology (Fig. 1i, Extended Data Fig. 3b). As expected, these mouse lines exhibited markedly reduced wake time (Fig. 1j, Extended Data 3c), similar to the original Sleepy pedigree. Thus, the lack of the exon 13 of the Sik3 gene causes the Sleepy phenotype.

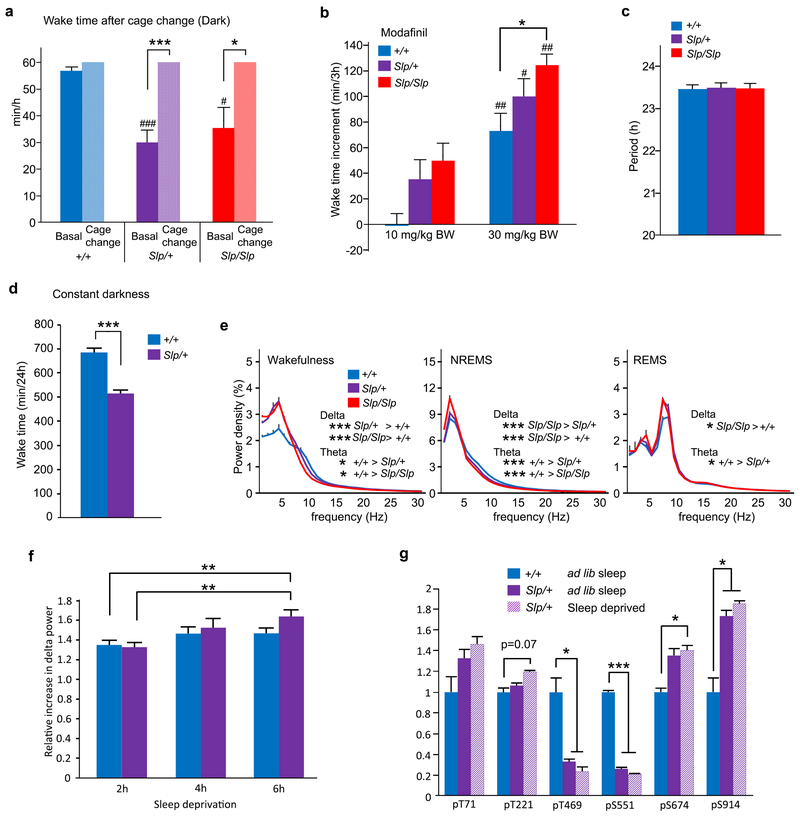

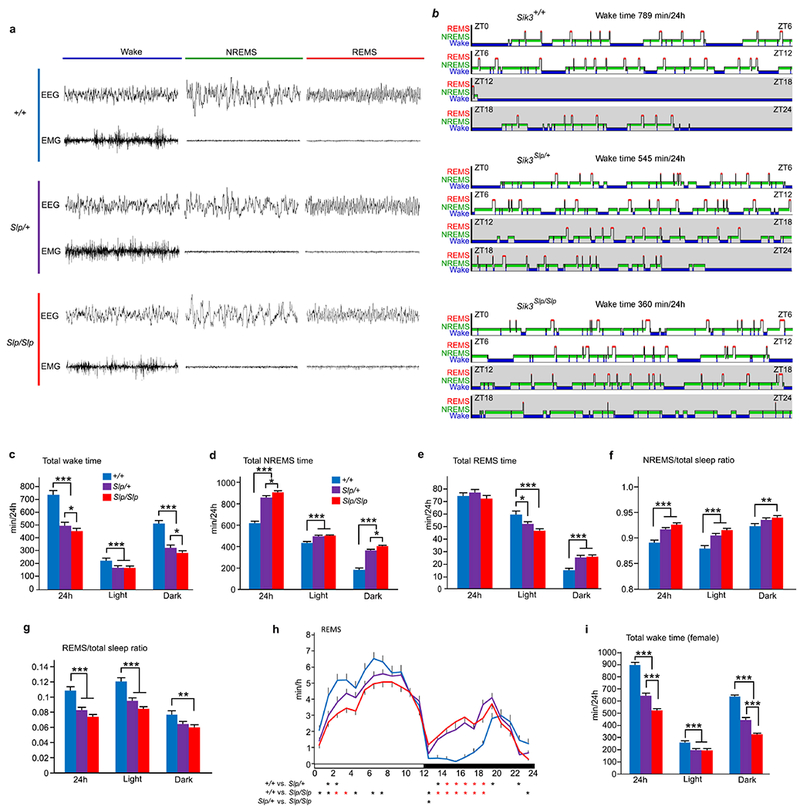

Increased sleep need in Sleepy mutants

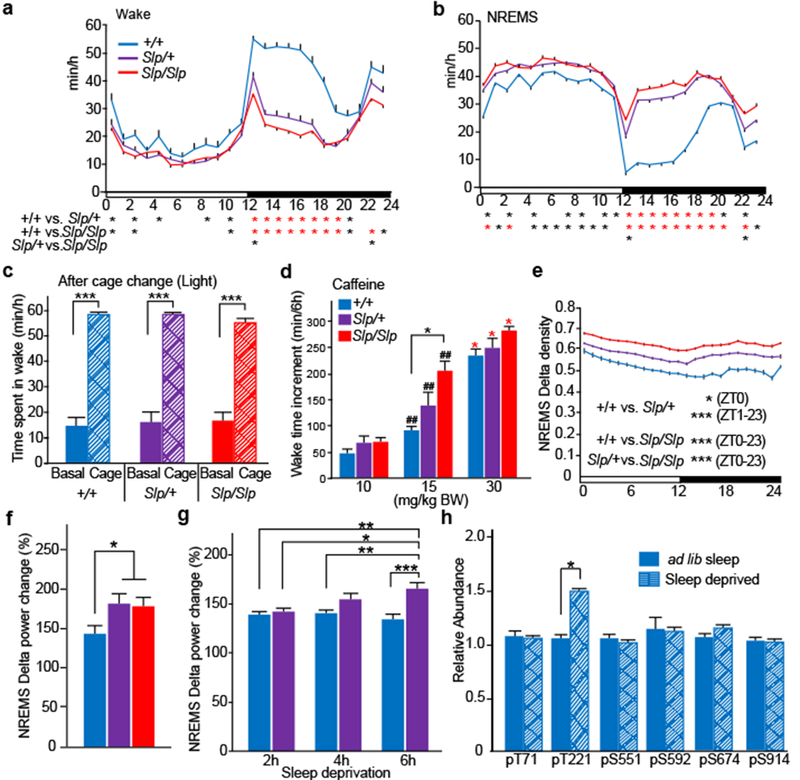

No overt abnormality in the sleep EEG/EMG was seen in the Sleepy mutants (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Detailed examination of sleep/wakefulness behavior of Sleepy mutants showed that, although Sik3Slp/+ mice exhibit reduced wake time and increased NREMS time both in the light and dark phases, the hypersomnia phenotype is more pronounced in the dark phase (Fig. 2a,b), possibly due to a ceiling effect in the light phase. Homozygous Sik3Slp/Slp mice had even shorter total wake time and longer NREMS time than Sik3Slp/+ mice (Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig. 4b,c,d), showing an allele dosage effect. Total REMS time was similar among genotype groups (Extended Data Fig. 4e). Sik3Slp/+ and Sik3Slp/Slp mice had higher a NREMS/total sleep ratio (Extended Data Fig. 4f) and a lower REMS/total sleep ratio (Extended Data Fig. 4g), indicating a NREMS-specific change in Sleepy mutant mice. Longer time spent in REMS during the dark phase seems to be secondary to the increased sleep amount and be compensated with shorter REMS time during the light phase (Extended Data Fig. 4h). Female Sik3Slp/+ and Sik3Slp/Slp mice also exhibited similar phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 4i).

Figure 2 |. Increased sleep need and normal wake-promoting response of Sik3 mutant mice.

a-b, Circadian variation in wakefulness (a) and NREMS (b) in Sik3+/+ (n = 22), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 32) and Sik3SlpJslp (n = 31) mice. One-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Black asterisk: P < 0.05; Red asterisk: P < 0.001. c, Time spent in wakefulness from ZT4 to ZT5 after cage change at ZT5 of Sik3+/+ (n = 6), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 9) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 6) mice. One-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *** P < 0.001. d, Wake time for 6-h after caffeine injection at ZT0 in Sik3+/+ (n = 6), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 6) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 6) mice. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05. ## vs. 10 mg/kg BW, P < 0.01. Red asterisk: vs. 15 mg/kg BW, P < 0.01. e, NREM delta density of Sik3 mutant mice (Sik3+/+, n = 22; Sik3Slp/+, n = 32; Sik3Slp/Slp, n = 31) across the LD cycle. One-way repeated ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, f, Increase in NREMS delta power of Sik3+/+ (n = 7), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 7) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 10) mice after 6-h sleep deprivation. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05. g, Increase in NREMS delta power after 2 h-, 4 h- and 6 h-sleep deprivation of Sik3+/+ (n = 11) and Sik3Slp/+ (n = 11) mice relative to NREM delta power of the same ZT during basal sleep. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05. ** P < 0.01. *** P < 0.001. h, Phosphorylation of FLAG-SIK3 of Flag-Sik3+/+ brains with or without 4-h sleep deprivation. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05. Values are means ± sem.

We next examined whether the short wake time of Sleepy mice is due to a defective wake-promoting response to behavioral or pharmacologic stimuli. A novel cage environment strongly mobilizes the wake-promoting system in mice6. Both Sik3Slp/+ and Sik3Slp/Slp mice exhibited prominent wake responses to cage change, similar to wildtype littermates during the light phase (Fig. 2c) and the dark phase (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Sik3Slp/+ and Sik3Slp/Slp mice also showed increased wake time in response to the administration of caffeine (Fig. 2d) or modafinil (Extended Data Fig. 5b), to similar or even slightly higher degrees than Sik3+/+ littermates. We then examined the behavioral circadian rhythm of the Sleepy mutants. The circadian period length as assessed by wheel-running behavior under constant darkness was similar among genotype groups (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Sleepy mutant mice showed a robust reduction in wake time also under constant darkness, similar to light-dark conditions (Extended Data Fig. 5d).

Given the apparently normal wake-promoting and circadian systems, we then hypothesized that the Sleepy mutants have an inherently higher sleep need. Indeed, Sleepy mutant mice exhibited a higher density of slow-wave activity during NREMS in an allele-dosage dependent fashion (Fig. 2e), suggesting that the base-line sleep need is increased in the mutants. Lower-frequency power in EEG was increased also during wakefulness in Sleepy mutant mice (Extended Data Fig. 5e), which may be associated with local cortical synchronization due to increased sleep need22. Furthermore, 6 h of sleep deprivation from the onset of the light phase increased NREMS delta power of Sik3Slp mice in a larger extent than Sik3+/+ mice (Fig. 2f). To examine dose-dependent effects, we conducted 2, 4 and 6 h of sleep deprivation. Under our conditions, Sik3+/+ mice showed only a slight increase after 2 h of sleep deprivation, whereas Sik3Slp/+ mice exhibited a marked dose-dependent increase in the delta power (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 5f), demonstrating their exaggerated response to sleep deprivation.

If SIK3 constitutes a part of the enigmatic molecular pathway determining the level of homeostatic sleep need, then the protein should be modulated by sleep deprivation. Because the function of SIK3 is regulated by its own phosphorylation23, we examined its phosphorylation status in the brain from mice in which a FLAG-tag was inserted in the N-terminus of SIK3 using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation with anti-SIK3 antibody and anti-FLAG antibody detected FLAG-SIK3 protein in the brain as expected (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c,d). To examine whether sleep deprivation affects the phosphorylation status of SIK3, brains of Flag-Sik3 mice were harvested after sleep deprivation. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of immunopurified FLAG-tagged proteins showed that sleep deprivation specifically increases the phosphorylation of residue T221, which is closely associated with the kinase activity of SIK323 (Fig. 2h). In the same way, we introduced a FLAG sequence in the Sik3Slp allele, and obtained mice expressing FLAG-SIK3 (SLP) protein (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). In addition to the expected decrease in the phosphorylation of S551, FLAG-SIK3 (SLP) in the brains showed a decrease in the phosphorylation of T469, another PKA-site24, and an increase in the phosphorylation of S914 compared with Flag-Sik3 mice under ad lib sleep during the light phase (Extended Data Fig. 5g). After sleep deprivation, these phosphorylation changes were sustained and a significant increase in the phosphorylation of S674, another PKA-site24, was recognized (Extended Data Fig. 5g). Thus, the lack of the S551-containing region disturbs the phosphorylation status of other PKA-sites in a complex fashion, suggesting a mechanistic link with the increased sleep need of Sleepy mutant mice.

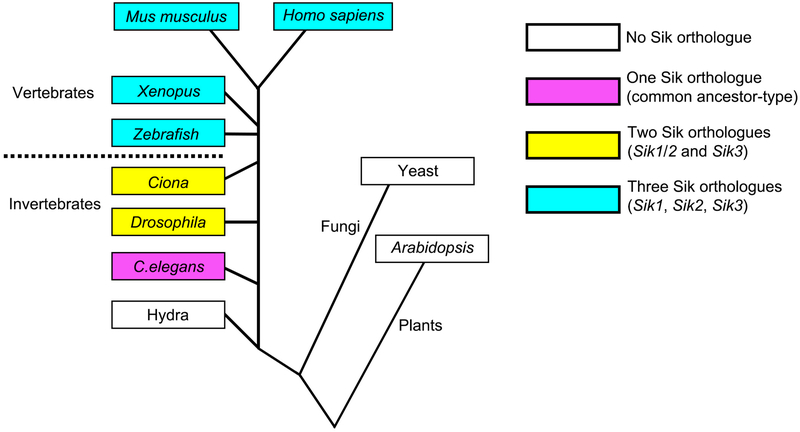

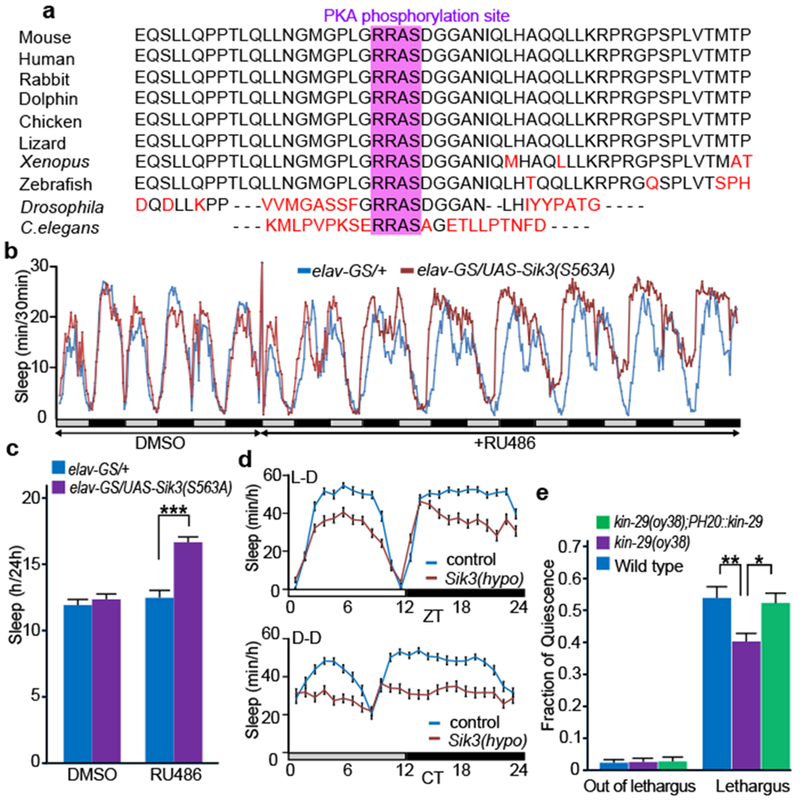

Conserved role of Sik3 in invertebrates

The exon 13-encoded region of SIK3 is highly conserved among vertebrate animals (Fig. 3a). Importantly, there is a PKA-recognition site within the exon 13-encoded region, which is conserved even in Sik3 orthologues of Drosophila and C. elegans (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 7). To examine the role of Sik3 orthologue in sleep-like behaviors in Drosophila, we expressed a phosphorylation-defective SIK3 (S563A: serine residue equivalent to mouse SIK3 S551) in neuronal cells in an RU486-inducible fashion. Daily sleep time of adult flies is increased upon induction of SIK3(S563A) (Fig. 3b,c). Conversely, flies with a hypomorphic Sik3 mutation showed reduced sleep time in the light-dark cycle and in the constant darkness (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, a null mutation of kin-29, the C. elegans orthologue of Sik3, reduced the fraction of quiescence during L4-adult lethargus, a sleep-like state in C. elegans3 (Fig. 3e). Pan-neuronal expression of kin-29 rescued this phenotype. Thus, orthologues of Sik3 also seem involved in the regulation of sleep amount in fruit flies and nematodes.

Figure 3 |. Role of Sik3 orthologues in invertebrate sleep-like behaviors.

a, The phylogenetic conservation of exon 13-encoded region of Sik3. b,c, Sleep time before and after induction of Sik3(S563A) by RU486 under constant darkness (32 per group). One-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *** P < 0.001. d, Sleep time of control and Sik3 hypomorphic mutant in 12h light-12h dark condition (upper, 16 per group, P < 0.001) and in constant darkness (lower, 16 per group, P < 0.001). One-way repeated measures ANOVA. e, Sik3 null mutant worms, kin-29(oy38) (n = 15), exhibited reduced quiescence during lethargus than wildtype worms (n = 10). kin-29(oy38);PH20::kin-29 (n = 9) in which wildtype kin-29 was expressed in neuronal cells restored normal quiescence during lethargus. Fraction of quiescence out of lethargus were similar ( P = 0.98). One-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. Values are means ± sem.

Nalcn mutation reduces REMS

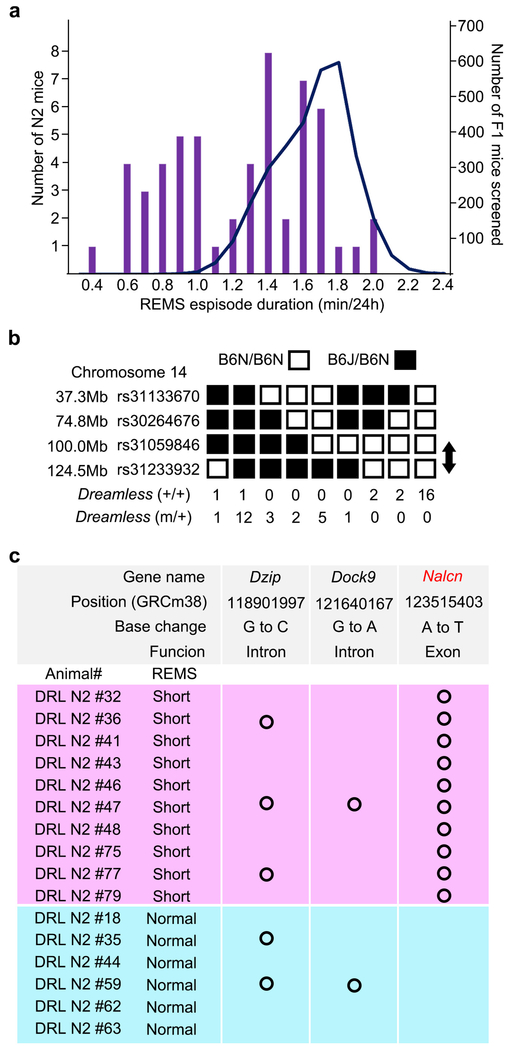

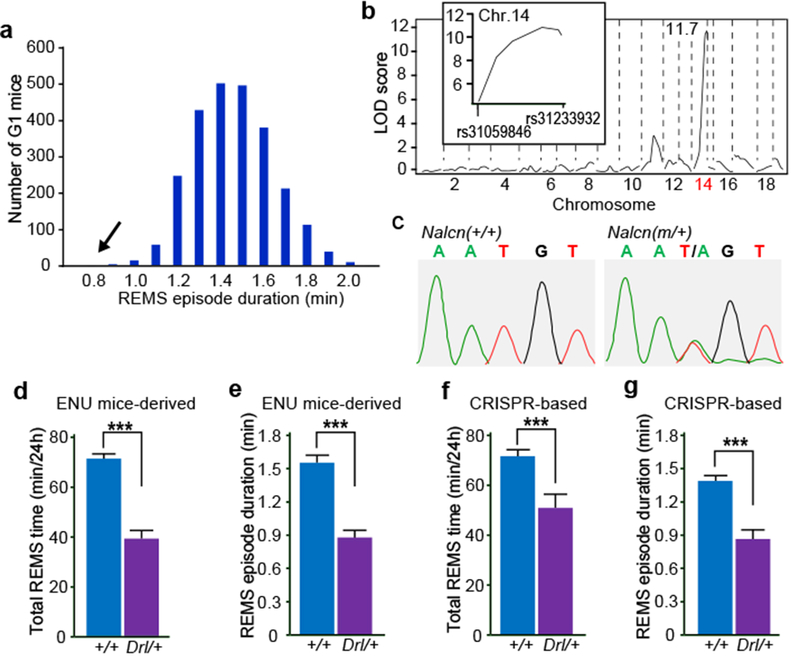

The EEG/EMG-based dominant screening of ENU-mutagenized mice also yielded a mutant pedigree with a REMS abnormality, termed Dreamless. The founder of the pedigree showed a short REMS episode duration (Fig. 4a), that was heritable in the offspring (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Linkage analysis in the B6J x B6N N2 generation showed a single LOD score peak near rs31233932 (chr14: 124108797) on chromosome 14 (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 8b). Whole-exome sequencing combined with direct sequencing of candidate genes identified a heterozygous missense mutation in the Nalcn gene (chr14: 123515403) as the only functionally relevant mutation within the mapped region in Dreamless mutants (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 8c). We then confirmed the causal relationship of the Nalcn gene mutation to the REMS phenotype by introducing the same nucleotide substitution in wildtype mice using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. CRISPR NalcnDrl/+ mice showed a short REMS episode duration, similar to the original Dreamless pedigree (Fig. 4d-g).

Figure 4 |. Missense mutation in Nalcn gene reduces REMS time and episode duration.

a, Histogram of REMS episode duration of G1 mice screened (mean ± SD = 1.41 ± 0.19 min). Arrow indicates the founder of Dreamless mutant pedigree. b, QTL analysis of Dreamless mutant pedigree (n = 56) for REM sleep episode duration. (Inset) LOD score peak near rs31233932. c, Direct sequencing of the Nalcn gene. d-e, Total REMS time (d) and REMS episode duration (e) of NalcnDrI/+ mice (n = 29) and Nalcn+/+ (n = 25) mice of the Dreamless mutant pedigree. Two-tailed Student’s t-test. *** p < 0.001. f-g, Total REMS time (f) and REMS episode duration (g) of NalcnDrl/+ mice (n = 11) and Nalcn+/+ (n = 17) mice produced by CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Two-tailed Student’s t-test. *** P < 0.001. Values are means ± sem.

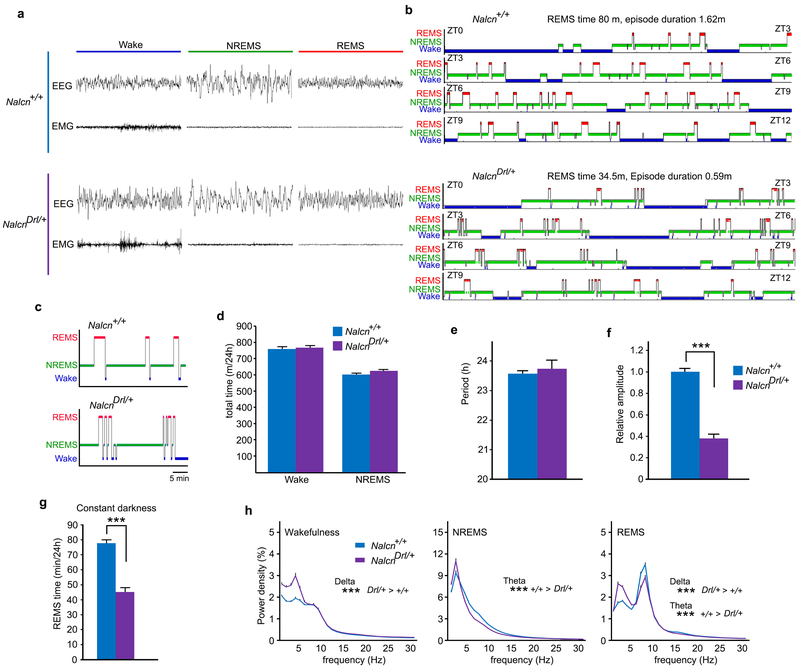

Dreamless mutants showed theta (6-9Hz)-dominant EEG and appropriate muscle atonia during REMS, and did not show any overt abnormality in the EEG/EMG (Extended Data Fig. 9a). NalcnDrl/+ mice showed a reduced total REMS time due to a short average REMS episode duration (Fig. 4d-g and Extended Data Fig. 9b,c). In other words, NalcnDrl/+ mice failed to maintain REMS state properly, resulting in highly unstable REMS. Total time spent in wake and NREMS of NalcnDrl/+ mice was similar to that of Nalcn+/+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 9d). NalcnDrl/+ mice had normal circadian period lengths but showed greatly reduced amplitude of behavioral circadian rhythms under constant darkness (Extended Data Fig. 9e,f), consistent with the recently reported involvement of NALCN in the circadian regulation of neuronal excitability in the suprachiasmatic nucleus25. Marked reduction in REMS time of NalcnDrl/+ mice was observed also under constant darkness (Extended Data Fig. 9g). Spectral analysis of EEG showed a decrease in theta-range power during NREMS and REMS and an increase in low-frequency power during Wake and REMS in NalcnDrl/+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 9h), suggesting the possibility that NALCN may regulate various oscillations in the brain.

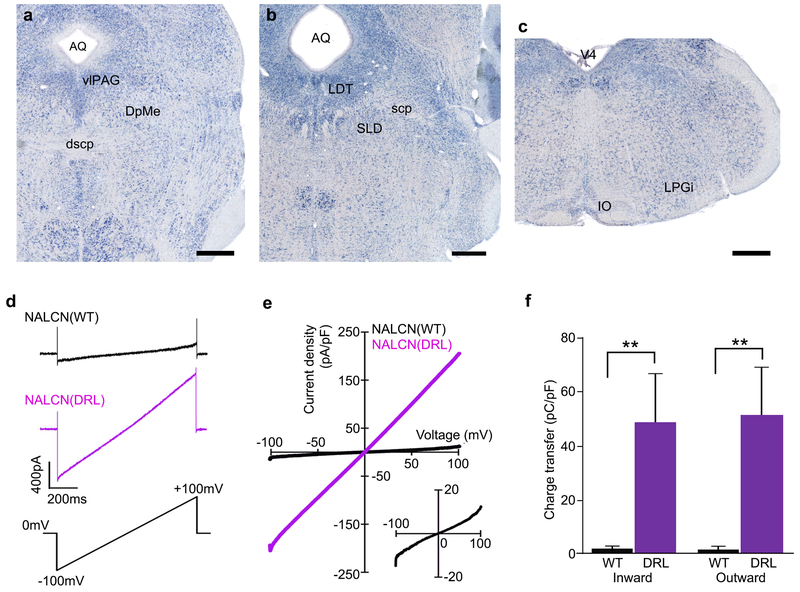

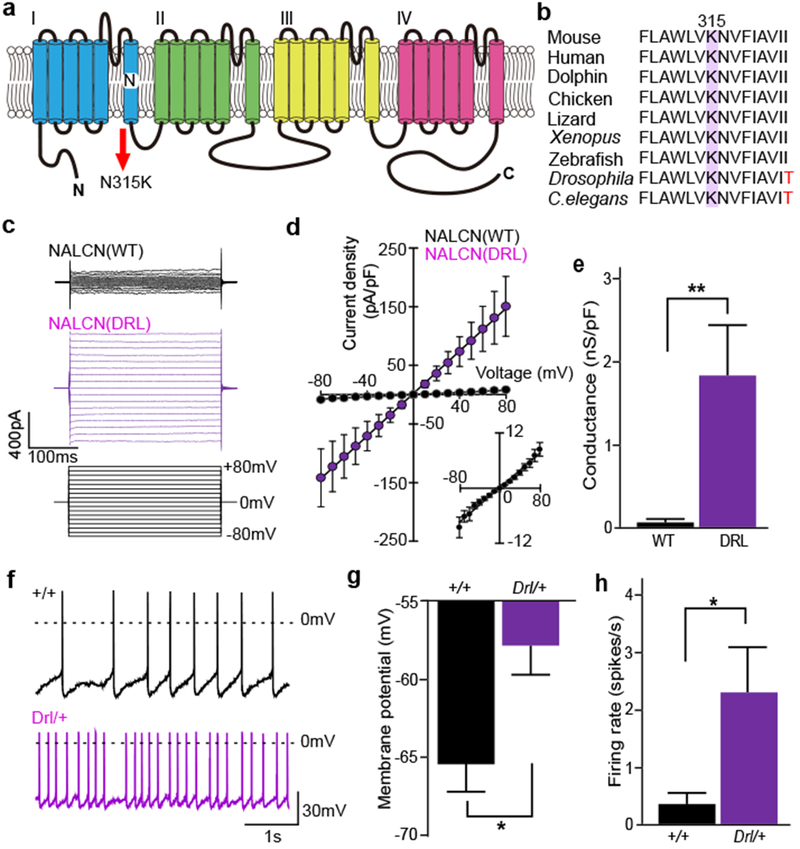

NALCN is a voltage-independent, non-selective cation channel with a proposed role in the control of neuronal excitability26. It is highly expressed in several brainstem nuclei involved in REMS regulation, such as the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray, deep mesencephalic nucleus (DpMe) and sublateral dorsal nucleus7,9,14,15 (Extended Data Fig 10a,b,c). The mutation results in N315K substitution in helix S6 of domain I (Fig. 5a), which is conserved among vertebrates and invertebrates (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5 |. Dreamless mutation in Nalcn gene increases excitability of neurons in the “REM-off” area.

a, Schematic structure of NALCN protein. b, Phylogenetic conservation of N315 residue in NALCN. c, Representative traces of membrane currents in response to 300-ms step pulses ranging from −80 mV to +80 mV in 10 mV increments (Vh = 0 mV, lower) recorded from HEK293T cells transfected with NALCN (upper) or NALCN(DRL) (middle). d, Mean current-voltage (I-V) curves in NALCN (n = 5, black circles) or NALCN(DRL) (n = 7, purple circles and lower right). e, The conductance of NALCN(DRL)-transfected cells was larger than that of NALCN-transfected cells (NALCN, 0.09 ± 0.02 nS/pF, n = 5; NALCN(DRL), 1.81 ± 0.62 nS/pF, n = 7). Mann-Whitney Utest. ** P < 0.01. f, Representative trace of membrane potentials of DpMe neurons in Nalcn+/+ (upper) and NalcnDrl/+ mice (lower). Dashed lines indicate 0 mV level. g-h, Mean membrane potentials (g) and spontaneous firing rates (h) of DpMe neurons (Nalcn+/+, n = 33; NalcnDrl/+, n = 31). Mann-Whitney U test. * P < 0.05. Values are means ± sem.

To examine whether the mutation changes the electrophysiological properties of NALCN, we made patch-clamp recordings from HEK293 cells cotransfected with NALCN or NALCN(DRL), together with UNC80 and SRC (Y529F), which allows constitutive activation of NALCN27,28. Both NALCN and NALCN(DRL) showed linear current-voltage relationships (Fig. 5c,d and Extended Data Fig. 10d,e), with similar equilibrium potentials (NALCN, −2.1 ± 1.6 mV, n = 7; NALCN(DRL), −1.2 ± 0.7 mV, n = 5, P = 0.94, Mann-Whitney U test). However, the ionic conductance of NALCN(DRL) was much larger than that of NALCN (Fig. 5e). Similarly, the charge transfer of inward and outward currents in NALCN(DRL)-transfected cells was markedly higher than in NALCN-transfected cells (Extended Data Fig. 10f), raising the possibility that NALCN(DRL) may increase the intrinsic excitability of REMS-regulatory neurons. To test this possibility, whole-cell current-clamp recordings were made from neurons in the DpMe (Extended Data Fig. 10a), which contains “REM-off ‘ cells 15,29,30, using brain slices from NalcnDrl/+ and Nalcn+/+ mice. The DpMe neurons in NalcnDrl/+ slices exhibited depolarization (Nalcn+/+, −65.6 ± 1.7 mV, n = 33 cells; NalcnDrl/+, −57.8 ± 2.0 mV, n = 31 cells; P = 0.01, Mann-Whitney Utest) and higher spontaneous firing rate (Nalcn+/+, 0.4 ± 2.3 spikes/s, n = 33 cells; NalcnDrI/+, 2.3 ± 0.8 spikes/s, n = 31 cells; P = 0.03, Mann-Whitney U test) compared with Nalcn+/+ slices (Fig. 5f,g,h).

Discussion

Our EEG/EMG-based forward genetic screen in mice has identified new sleep phenotypes and mutated genes. Yet our study also illustrates a conserved role of SIK3 in the sleep behavior of vertebrates and invertebrates. We think that the Sleepy mutation in SIK3 increases the animal’s intrinsic sleep need, because Sleepy mutant mice exhibit the following: i) a higher density of slow-wave activity, a reliable index of homeostatic sleep need; ii) a larger increase of NREM delta power after sleep deprivation; iii) a normal waking response to behavioral or pharmacologic arousal stimuli. Furthermore, we found that the functionally relevant phosphorylation status of SIK3 is modulated by sleep deprivation. Taken together with the finding that the Sleepy mutation markedly increases the baseline NREMS amounts in an allele dosage-dependent fashion, we propose that SIK3 functions in the intracellular signaling pathway that dictates sleep need and regulates the daily amount of sleep.

We propose that NALCN works in the neuronal groups regulating REMS9,14,15 for the maintenance and termination of REMS episodes. The narrow abdomen (na) mutant, carrying a loss-of-function mutation in Drosophila orthologue of NALCN, exhibits increased sensitivity to anesthesia31 and abnormal circadian behavior32 in part through a blunted circadian change in neuronal excitability25. The crucial role of NA in enhancing bi-stability between wakefulness and anesthetized state, as well as between wakefulness and sleep33, is consistent with de-stabilized REMS episodes of the Dreamless mutant mice. Thus, like the case of SIK3 above, NALCN orthologues also appear to play conceptually analogous roles in regulating sleep-related behaviors both in mice and fruit flies. Our results argue for the utility of unbiased forward genetic screens for discovery of novel genes, alleles and pathways regulating sleep in mammals.

Methods

Animals and mutagenesis

Male C57BL/6J mice (CLEA Japan) were treated with ethylnitrosourea (85 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) by intraperitoneal injection twice at weekly intervals at the age of 8 weeks. At the age of 25-30 weeks, the sperm of the mice was used for in vitro fertilization with eggs of C57BL/6N mice to obtain F1 offspring. Mice were provided food and water ad libitum, and were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and housed under controlled temperature and humidity conditions. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tsukuba and the RIKEN BioResource Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas.

Surgery

EEG/EMG electrode implantation was performed as described previously34, with isoflurane (3% for induction, 1% for maintenance) used for anesthesia. Seven days after surgery, the mice were tethered to a counterbalanced arm (Instech Laboratories) that allowed free movement and exerted minimal weight.

Screening scheme

At the age of 12 weeks, male mice were implanted with EEG/EMG electrodes and then screened for sleep/wakefulness behavior. Examined parameters were total time spent in wake, NREMS and REMS, episode duration of wake, NREMS and REMS, appearance of muscle atonia during REMS, and rebound sleep after 4-h sleep deprivation by shaking the cages. For quantitative parameters, we selected mice whose phenotypes deviated from the average by at least 3 standard deviations. After confirming the reproducibility of the sleep phenotype, the mice were selected for offspring production by natural mating or IVF with wildtype females to examine the heritability of the sleep phenotypes. If at least 30% of the male littermates showed sleep phenotypes similar to their father, we considered the sleep abnormalities to be heritable.

Linkage analysis

SNPs of N2 mice were determined using a custom TaqMan Genotyping assay (Thermo Fisher). The custom probes were designed based on the polymorphism data between C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N20. QTL analysis was performed using J/qtl software (Jackson Laboratory).

Whole exome sequencing

Whole exomes were captured with SureSelectXT2 Mouse All Exon (Agilent) and processed to a paired end 2 × 100-bp run on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform at the UTSW McDermott Center Next Generation Sequencing Core. Reads were mapped to the University of California Santa Cruz mm9 genome reference sequence for C57BL/6J using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner and quality filtered using SAMtools. Cleaned BAM files were used to realign data and call variants using the Genome Analysis ToolKit to detect heterozygous mutations.

Sleep behavior analysis

The recording room was kept under 12-h light-dark cycles and a constant temperature (24-25 °C). To examine sleep-wake behavior under baseline conditions, EEG/EMG signals were recorded for two consecutive days from the onset of the light phase. EEG/EMG data were visualized and analyzed using a MatLab (MathWorks)-based, custom semi-automated staging program followed by visual inspection. EEG signals were subjected to fast Fourier transform analysis from 1 to 30 Hz with 1-Hz bin using MatLab-based custom software. Epochs containing movement artifacts were included in the state totals but excluded from subsequent spectral analysis. Sleep/wakefulness was staged into wakefulness, NREM sleep and REM sleep. Wakefulness was scored based on the presence of low amplitude, fast EEG and high amplitude, variable EMG.

NREMS was characterized by high amplitude, delta (1-4 Hz) frequency EEG and low EMG tonus, whereas REMS was staged based on theta (6-9 Hz) dominant EEG and EMG atonia. Hourly delta density during NREMS indicates hourly averages of delta density which is the ratio of delta power to total EEG power at each 20-second epoch. For the power spectrum of sleep/wakefulness, EEG power of each frequency bins was expressed as a percentage of the total EEG power over all frequency bins (1-30Hz) and sleep/wakefulness states34,35. For sleep deprivation, mice were sleep deprived for 2, 4 and 6 hours from the onset of the light phase by gently touching the cages when they started to recline and lower their heads. Food and water were available. To evaluate the effect of sleep deprivation, NREM delta power during the first hour after sleep deprivation was expressed relative to the same zeitgeber time of the basal recording or relative to the mean of the basal recording. For caffeine and modafinil injection experiments, mice were fully acclimatized for intraperitoneal injection before sleep recording. After 24-h baseline recording, mice received intraperitoneally caffeine (Sigma), modafinil (Sigma) or vehicle (0.5% methyl cellulose (Wako)) at ZT0, followed by 12-h recording. Injections were delivered once per week, with each injection followed by a 6-8 day washout period, during which mice remained in the recording chamber. To examine the sleep/wakefulness behavior under constant darkness, after 48-h recording under a LD 12: 12 cycle, EEG/EMG recording continued in constant darkness for 3 days.

Circadian behavior analysis

Mice were housed individually in a cage (Width 23 cm, Length 33 cm, Height 14 cm) containing a wireless running wheel (Med Associate #ENV-044). Cages were placed in a light-tight chamber equipped with green LED light (100 lux at the bottom of the cage). The rotation numbers of wheels were obtained with 1-min bin using Wheel manager software (Med Associate). Mice were entrained to LD12:12 cycle for 7 days, and then released into constant darkness for 3 weeks. The free running period was calculated with linear regression analysis of activity onset using MatLab-based custom software. Circadian activity amplitude was calculated by fast Fourier transform of activity data which were processed with Bartlett window using MatLab-based custom software. Relative amplitude was normalized to the mean amplitude of the wild type group.

Western blot

A rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal 171 amino acids of mouse SIK3 was generated using custom antibody production service (Pacific Immunology, Ramona, CA USA). Tissues were homogenized using a rotor-stator homogenizer (Polytron) in ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 1.5% Triton-X100,15 mM NaF, 1X PhosSTOP (Roche), 5 mM EDTA, 1X Protease Inhibitor (Roche)), and then centrifuged at 13,000g at 4 °C. The supernatants were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred on PVDF membrane. Western blotting was performed according to standard protocols.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described previously36. In brief, a 0.7-0.8 kb fragment of Nalcn cDNA was inserted into pGEM-T easy (Promega) and used for DIG-labeled probe synthesis. Mice were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Forty μm-thick brain sections were treated with 0.3% Triton X-100, digested with 1 μg/ml proteinase K, treated with 0.75% glycine, and then treated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamine. After overnight incubation with DIG-labeled probe at 60 °C, the sections were washed and then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG Fab fragments (Roche, 11175041910). The reactions were visualized with a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/4-nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/ NBT) substrate solution (Roche).

Cell lines

HEK293 cells (RCB1637) and HEK293T cells (RCB2202) were obtained from the RIKEN BRC Cell Bank. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Wako) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell lines were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination using MycoAlert (Lonza). Cell lines were regularly renewed by obtaining cell stocks from the Cell Bank for authentication. We used HEK293 and HEK293T cells because of their reliable growth, high efficiency in transfection and morphology suitable for electrophysiological experiments.

Production of Sik3 gene-modified mice by conventional gene targeting

For generating Sik3Slp knock-in mice, a genomic fragment containing exon 13 of the Sik3 gene was isolated from C57BL/6 mouse genomic BAC clone from a RP23 mouse genomic BAC library (Advanced GenoTEchs Co). A 1.7-kb fragment of FRT-PGK-gb2-neo-FRT-loxP cassette (Gene Bridges) flanked by two flippase recognition target (FRT) sites was inserted before exon 12. The targeting vector also contains a G-to-A substitution at the 5th nucleotide from the beginning of intron 13. The targeting vector was linearized and electroporated into the C57BL/6N ES cell line RENKA. Correctly targeted clones were injected into eight-cell stage ICR mouse embryos, which were cultured to produce blastocysts and then transferred to pseudopregnant ICR females. Resulting male chimeric mice were crossed with female C57BL/6N mice to establish the Sik3Slp-neo/+ line. To remove the neomycin resistance gene with the FLP-FRT system, Sik3Slp-neo/+ mice were crossed with Actb-FLP knock-in mice.

Production of Sik3 gene-modified mice using ZFN

The custom designed ZFN mRNAs targeting the exon 13-intron 13 boundary region of the Sik3 gene were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich’s Composers® Custom ZFN service. Before the final assembly of the ZFN products, Sigma-Aldrich validated the designed ZFN binding sequences in silico using their bioinformatics tools and in vitro using Nero2A cell-lines, ensuring high cutting efficiency and specificity using mismatch-specific endonuclease CelI according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ZFN mRNAs were injected into single-cell stage C57BL/6J mouse zygotes at UT Southwestern Transgenic Core facility. The injected eggs were then transferred to pseudopregnant females to generate F0 founders. In total, 45 out of 96 F0 mice were found to be modified at the exon 13-intron 13 boundary region of the Sik3 gene. We crossed one F0 male mouse which had a 2 bp deletion from the last nucleotide of exon 13 with female C57BL/6N mice to obtain F1 mice of Sik3Slp/+ ZFN. The F1 mice were used to confirm the skipping of exon13 in Sik3 mRNA which was purified from the brains and livers. The F2 male mice were used for sleep/wakefulness behavior analysis.

Production of Flag-Sik3 mice and NalcnDRL mice by CRISPR/Cas9 technology

To produce a Cas9/single guide RNA (sgRNA) expression vector, oligo DNAs (5’-caccGCGAGCGGCCATCGACCCGC-3’ and 5’-aaacGCGGGTCGATGGCCGCTCGC-3’) were annealed and then inserted into pX330 vector (Addgene). The cleavage activity of the pX330-Sik3Ex1 vector was evaluated by the EGxxFP system37. Genomic DNA containing exon 1 of the Sik3 gene was amplified and inserted into pCAG-EGxxFP to produce pCAG-EGxxFP-Sik3Ex1. The pX330-Sik3Ex1 and pCAG-EGxxFP-Sik3Ex1 were transfected into HEK293 cells. As a donor oligonucleotide, a single-stranded 200nt DNA was synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies), which contained a FLAG-HA-coding sequence in the center and 70nt arms at the 5’ and 3’ ends. Female C57BL/6J mice or Sik3Slp knock-in mice were injected with pregnant mare serum gonadotropin and human chorionic gonadotropin at a 48-h interval, and mated with male C57BL/6J mice. The fertilized one-cell embryos were collected from the oviducts. Then, 5 ng/μl of pX330-Sik3Ex1 vector and 10 ng/μl of the donor oligo were injected into the pronuclei of these one-cell-stage embryos. The injected one-cell embryos were then transferred into pseudopregnant ICR mice. F0 mice were genotyped for the presence of FLAG-coding sequence in exon1 of the Sik3 gene and for the presence of the Sik3Slp mutation. F0 mice containing FLAG-SIK3 were further examined for the presence of the Cas9 transgene and off-target effects. Candidate off-target sites were identified based on a complete match of 16 bp at the 3’ end, including the PAM sequence. F0 mice were mated with C57BL/6N mice to obtain F1 offspring.

NalcnDrl mice were produced as described above. To produce the sgRNA expression vector, pX330-NalcnEx9, oligo DNAs (5’-caccAGCAATAAACACATTCTGAA-3’ and 5’-aaacTTCAGAATGTGTTTATTGCT-3’) were used. Genomic DNA containing exon 9 of the Nalcn gene was amplified and inserted into pCAG-EGxxFP to produce pCAG-EGxxFP-NalcnEx9. As a donor oligo, a single-stranded 199nt DNA containing a T-to-A substitution at the center was synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies). Nalcn mutant mice of N2-N3 generation were used for sleep/wakefulness analysis.

Phosphoproteomic analysis

To evaluate FLAG-tagged SIK3 protein in brains, we performed peptide mapping of the purified FLAG-SIK3 protein. The brains of Flag-Sik3 knock-in mice and Flag-Sik3Slp knock-in were quickly dissected after cervical dislocation. Brains were homogenized in detergent-free buffer and then centrifuged (100,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C ). The supernatant was immunoprecipitated with anti-DDDDK antibody beads (MBL #3325). The eluate was run on a polyacrylamide ge1 and stained with SilverQuest Silver staining kit (Life technologies). FLAG-SIK3 band (150kD) was dissected with a fresh blade. The proteins in the bands were reduced with lOmM dithiothreitol and alkylated with 40 mM iodoacetamide. Each sample was digested with trypsin (4 μg/ml; Trypsin Gold, Promega) at 37 °C overnight. The extracted peptides were then separated via nano flow LC (Advance LC, Michrom Bioresources) using a C18 column. The LC eluate was coupled to a nano-ionspray source attached to a Orbitrap Velos Pro mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All MS/MS spectra were searched using Proteome Discoverer 1.3 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were mapped through mouse SIK3 (NP_081774) with 56% coverage.

To examine the effect of sleep deprivation on the phosphorylation status of SIK3 protein, Five Flag-Sik3 knock-in mice or five Flag-Sik3Slp knock-in mice were ad lib slept (S) or sleep deprived (SD) for four hours by gentle handling immediately after light onset (ZT0-ZT4). Five wildtype (WT) mice were used as a negative control. At ZT4, mouse brains were quickly dissected after cervical dislocation, rinsed with cold PBS, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Each half of the brains was lysed in 2 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2, 15 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7) freshly supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche), and homogenized in a glass tissue homogenizer. After brain homogenate was incubated for 30 min and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was pre-cleared by IgG and Protein G beads for 30 min before immunoprecipitation. Each pre-cleared lysate was added to 50 μl of anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated Sepharose beads (Sigma, A2220) and rotated overnight at 4 °C. After washing the beads 5 times with cold wash buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2, 15 mM NaF, 10 mMNa4P207), 50μl of elution buffer (2%SDS, 60 mM Tris/HCl (pH6.8), 50 mM DTT, 10% glycerol) was added and rotated for 10 min at 4 °C. Elution was repeated twice and combined into one eluate and analyzed by western blotting. For each group of five mice, the five eluates of were mixed and equally split into two samples for mass spectrometric analysis. Thus, a total of six samples were reduced, alkylated, and trypsin digested overnight. After each sample was labeled with a different TMT-6 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), six samples were combined into one mixture for HPLC fractionation using a Cl8 column. A total of 12 fractions were collected, and analyzed separately on the Orbitrap-Fusion mass spectrometry platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a reverse-phase LC-MS/MS method. We performed data analysis to identify peptides and quantified reporter ion relative abundance using Proteome Discoverer 2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The relative abundance of quantified SIK3 phosphorylation sites was normalized with wildtype negative control and total SIK3 protein abundance.

Patch-clamp recordings from HEK cells

To express wildtype NALCN, we used pTracer-CMV2-ratNALCN-EF1α-EGFP (a gift from Dr. Ren)38. A single nucleotide substitution was induced to make pTracer-CMV2-ratNALCN(DRL)-EF1α-EGFP using a KOD plus Mutagenesis kit (Toyobo). HEK293T cells were grown to −50% confluency in 12-well plates. Using Lipofectamine LTX (2 μl) and PLUS (1 μl) reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), the cells were cotransfected with 0.3 μg of each plasmid DNA encoding rat NALCN-EGFP (WT or DRL), mouse UNC-80, and mouse SRC (Y529F) (constitutively active Src) in 12-well plates. UNC-80 and SRC kinase activate NALCN27,28. In some experiments, the cells were incubated with 10 μM Gd3+ to inhibit NALCN. The cells were dissociated and plated on 18-mm coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine in fresh culture medium prior to patch-clamp recordings.

All patch-clamp recordings from HEK293T cells were performed > 72 h after transfection. Recording patch pipettes were pulled from glass capillaries (1B150F-4, World Precision Instruments) using a micropipette puller (P-97, Sutter Instrument) to give a resistance of ~9 MΩ. The series resistance of whole-cell recordings was ~40 MΩ, which was not compensated. Patch pipettes were fdled with solution containing 150 mM CsOH, 120 mM methanesulfonic acid, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM Mg2ATP and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with methanesulfonic acid; osmolarity, 290–299 mOsm/L adjusted with CsC1). The cells on coverslips were transferred to a recording chamber under a fluorescence upright microscope (Axio Examiner D1, Zeiss) and continuously perfused with the bath solutions containing 150 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 20 mM glucose, 5 mM NaOH, 2 mM MgCl2 and 1.2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4 adjusted; osmolarity, 300–310 mOsm/L). The transfected cells were identified by EGFP fluorescence. Patch-clamp recordings were performed at room temperature (24 °C) using a computer-controlled amplifier (MultiClamp 700B, Molecular Devices). The signals were digitized with A/D converter (Digidata 1440A, Molecular Devices), and acquired with Clampex (Molecular Devices) at a sampling rate of 50 kHz, and low-pass filtered at 5 kHz. At the end of recording, Gd3+ (10 μM) was used to confirm that the whole-cell currents were mediated through NALCN38. Data were analyzed using Clampfit (Molecular Devices). The equilibrium potentials were calculated from I-V curves. Mean membrane conductance was estimated from the regression lines fitted to I-V curves from individual cells. Current, membrane conductance and charge transfer were normalized to membrane capacitance.

Patch-clamp recordings from neurons

Patch pipettes and recording system were the same as those used in recordings from HEK293 cells. Acute brain slices containing the DpMe were prepared from postnatal day 12-23 Nalcn+/+ or NalcnDrl/+ mice. After the induction of deep anesthesia with isoflurane, mice were decapitated and the brains were rapidly removed into an ice-cold cutting solution containing 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose, 185 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4, when bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). The brains were cut coronally into 200-250 μm-thick slices with a vibratome (VT-1200S, Leica). The slices were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4, when bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2) prior to recordings. Slices were transferred to a recording chamber perfused with aCSF under an upright microscope (Axio Examiner D1, Zeiss). For current-clamp recordings, patch pipettes were filled with solution containing 125 mM K-gluconate, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM EGTA, 8 mM Phosphocreatine-Na2, 4 ATP-Mg and 0.3 GTP-Na (pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH; osmolality, 290 mOsm/L). The DpMe was identified with axon bundles. Recordings were made from cells located in the medial part of the DpMe. Cells showing no action potentials following current injection (> 1 nA, > 5 ms) were discarded from analysis. Membrane potentials were recorded for 1–10 min.

Fruit fly stocks and behavioral assay

Sik3 hypomorph and UAS-Sik3, UAS-Sik3(S563A) transgenic flies were gifts from Drs. Marc Montminy and John B. Thomas39. elav-GS (GeneSwitch) stocks were from the Bloomington stock center. Flies were reared at 25°C under 12 hr light : 12 hr dark cycle (LD) in 50–60% relative humidity on a standard fly food consisting of corn meal, yeast, glucose, wheat germ and agar.

Sleep analysis was performed as described previously40. Briefly, male flies (2 to 5 days old) were individually housed in glass tubes (length, 65 mm; inside diameter, 3 mm) containing standard fly food at one end and a cotton plug on the other end. Sucrose-agar (1% agar supplemented with 5% sucrose) food was used for the GeneSwitch system assay, instead of standard food. The glass tubes were placed in the Drosophila activity monitor (DAM) (Trikinetics, MA, USA) and the locomotor activity of each fly was recorded as the number of infrared beam crossings in 1-min bin. Sleep was defined as periods of inactivity lasting 5 min or longer. Sleep assay were performed for 3 d under LD cycle condition and then constant darkness (DD) conditions. For LD, zeitgeber time (ZT) was used, and for DD, circadian time (CT), with CT 0 as 12 h after lights-off of the last LD conditions, was used to indicate the daily time.

For conditional expression analysis, we used the GeneSwitch system41 where expression is induced by a steroid hormone antagonist RU486. Flies are monitored for 3 days in tubes without drug in DD and then transferred to new tubes either with vehicle (0.5% DMSO) alone or with 0.5 mM RU486 and then further monitored under DD condition. The expression of endogenous or transgenic Sik3 genes were confirmed by RT-PCR using RNA from fly heads.

Nematode strains and quiescence assay

The wildtype strain N2 and the mutant strain PY1479 kin-29(oy38) X were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC)42. All worms were maintained at 20°C on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with E. coli HB101. For construction of PH20::kin-29, kin-29 cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR and inserted into the plasmid pPD-DEST (a gift from Y. Iino, the University of Tokyo) to generate pDEST-KIN-29. Next, we carried out the LR-recombinase reaction (Gateway System, Life Technologies) between pENTR-PH20 (a gift from Y. Iino, the University of Tokyo) and pDEST-KIN-29 to generate PH20::kin-29. PH20::kin-29 was injected at 30 ng/μl together with the injection marker Pmyo-3::mcherry (10 ng/μl) and the empty vector pPD49_26 (60 ng/μl) into the kin-29(oy38) mutant worms.

Quiescence during the L4 to adult lethargus was measured using the microfluidic-chamber based assay43. Briefly, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-made microfluidic chambers containing liquid NGM and the E. coli HB101 were loaded with early L4 larvae and sealed with a cover glass plus 2% agarose, and set under the microscope. Images were taken every 2 seconds for 12 to 20 hours at 20 ± 0.5°C using the microscope M205FA (Leica) equipped with the camera MC120HD (Leica) (pixel size: 1024 μm × 768 μm) controlled by Leica Application Suite V4.3 or the microscope SZX16 (Olympus) equipped with the camera GR500BCM2 (Shodensha) (pixel size: 1024 μm × 768 μm) controlled by μManager (UCSF). Subtraction between serial images was carried out using Image J, and worms were regarded as quiescent at a specific time point if the difference from the preceding time point was less than 1% of the total body size. The fraction of quiescence was defined as the number of quiescent time points divided by the total number of time points during a period of 10 min.

The onset of lethargus quiescence was defined as the time point after which the fraction of quiescence was higher than 0.05 for at least 20 min, whereas the end point was defined as the time point after which the fraction of quiescence was lower than 0.05 for at least 20 min. Occasionally, brief episodes of quiescence were observed outside of lethargus both in wildtype and mutant worms; these episodes were excluded by setting a threshold of 60 min for the minimum duration of lethargus quiescence.

Statistics

Sample sizes were determined using R software based on averages and standard deviations that were obtained from small scale experiments. No method of randomization was used in any of the experiments. The experimenters were blinded to genotypes and treatment assignment. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM) and R software. All data were tested for Gaussian distribution and variance. Homogeneity of variances was tested with Levene’s test. We used Student’s t-test for pairwise comparisons, one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons, one-way repeated measure ANOVA for multiple comparisons with multiple data points, and two-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons involving two independent variables.

ANOVA analyses were subjected to Tukey’s post hoc test. When deviation from normality and lack of homogeneity of variances occurred (P < 0.05), Mann-Whitney U test was used for group comparison. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1 |. Sleep/wakefulness screening of randomly mutagenized mice.

a, ENU-treated G0 mice were mated with B6N females to obtain the offspring. The F1 mice were used for sleep/wakefulness analysis. A mouse showing any sleep abnormalities was crossed with B6N female mice. The N2 progeny was examined for heritability of sleep abnormality and for chromosomal mapping, b, B6J (n = 20) and B6N (n = 21) showed similar the total wake time (left, P = 0.67, two-tailed Student’s t-test). NREMS time (center, P = 0.66) and REMS time (right, P = 0.84). Values are means ± sem. c, The histogram shows total daily wake time of all mice screened. Total wake time of screened mice was 735 ± 66.9 min (mean ± SD). Arrows indicate the founders of Sleepy mutant pedigree.

Extended Data Figure 2 |. QTL analysis of Sleepy mutant pedigrees and characterization of Sik3 transcript.

a, QTL analysis of B021 (n = 119), B022 (n = 95), B024 (n = 59) and B025 (n = 112) pedigrees for total wake time produced a single LOD score peak on chromosome 9. b, Direct sequencing of the exon 12/13 boundary and exon 13/14 boundary of Sik3 mRNA of Sik13+/+ mouse. Direct sequencing of the short RT-PCR product specific to Sik3 mutant mice shows the direct transition from exon 12 to exon 14. c-d, Sik3 mRNA is expressed broadly in forebrain neurons (c). Sik3 mRNA is expressed throughout the cerebral cortex in the primary motor area(d). DG, dentate gyrus; LV, lateral ventricle; MHb, medial habenula. Scale bars; 1 mm (c), 250 μm (d). e, RT-PCR of Sik3 mRNA from cerebral cortex and liver of Sik3+/+, Sik3Slp/+ and Sik3Slp/Slp mice. Normal Sik3 variant lacking exon 15 expressed in the cerebral cortex.

Extended Data Figure 3 |. Sleep/wakefulness of Sik3Slp knock-in mice.

a, The structure of the Sik3 genome and targeting vector for Sik3Slp. Neomycin resistance gene under the mouse phosphoglycerol kinase promoter (neo) was sandwiched with the Flippase Recognition Target (FRT) sequences. The guanine at the fifth nucleotide from the beginning of the intron 13 was substituted with adenine. The neo cassette was deleted by crossing with beta-actinCAG-FLP knock-in mice, b, RT-PCR of Sik3 mRNA of Sik3Slp/+ knock-in mice, c, Total wake time of Sik3Slp/+ knock-in mice (n = 10) and Sik3+/+ littermates (n = 6). Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *** P < 0.001. Values are means ± sem.

Extended Data Figure 4 |. Sleep/wakefulness behaviors of Sik3 mutant mice.

a, Representative 8s-EEG and EMG for wake, NREMS and REMS of Sik3 mutant mice, b, Representative hypnogram of Sik3 mutant mice. Wake (blue), NREMS (green) and REMS (red) are indicated from ZT0 to ZT24. c-g, Total wake time (c), NREMS time (d), REMS time (e), NREMS/total sleep ratio (f) and REMS/total sleep ratio (g) and circadian variation of REMS (h) of Sik3+/+ (n = 22), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 32) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 31) mice. For c-g, Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. For h, One-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Black asterisk, P < 0.05; Red asterisk, P < 0.001. i, Total wake time of female Sik3+/+ (n = 10), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 11) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 9) mice. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *** P < 0.001. Values are means ± sem.

Extended Data Figure 5 |. Characterization of Sleep/wakefulness behaviors of Sik3 mutant mice.

a, Wake time after cage change at ZT15 in Sik3+/+ (n = 5), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 10) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 5) mice. The graph shows time spent in wakefulness from ZT15 to ZT16 under a basal condition and after cage change from the home cage to a new cage at ZT15. One-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001; vs. Sik3+/+, #P < 0.05, ### P < 0.001. b, Wake time increase for 3 h after modafinil injection at ZT0 to Sik3+/+ (n = 6), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 6) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 6) mice. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05; vs modafinil 10 mg/kg in the same genotype # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01. c, The circadian period under constant darkness in Sik3 (n = 8), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 8) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 6) mice. One-way ANOVA. P = 0.97. d, Total wake time of Sik3+/+ (n = 9) and Sik3Slp/+ (n = 12) mice under constant darkness. Two-tailed Student’s /-test. *** P < 0.001. e, EEG power spectra of Sik3+/+ (n = 22), Sik3Slp/+ (n = 32) and Sik3Slp/Slp (n = 31) mice. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001. f, Increase in NREMS delta power after 2 h-, 4 h- and 6 h-sleep deprivation of Sik3+/+ (n = 11) and Sik3Slp/+ (n = 11) mice relative to mean NREM delta power during basal sleep. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. ** P < 0.01. g, Phosphorylation of FLAG-SIK3 of Flag-Sik3+/+ brains and of FLAG-SIK3(SLP) of Flag-Sik3Slp/+ brains with or without 4-h sleep deprivation. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05. *** P < 0.001. Values are means ± sem.

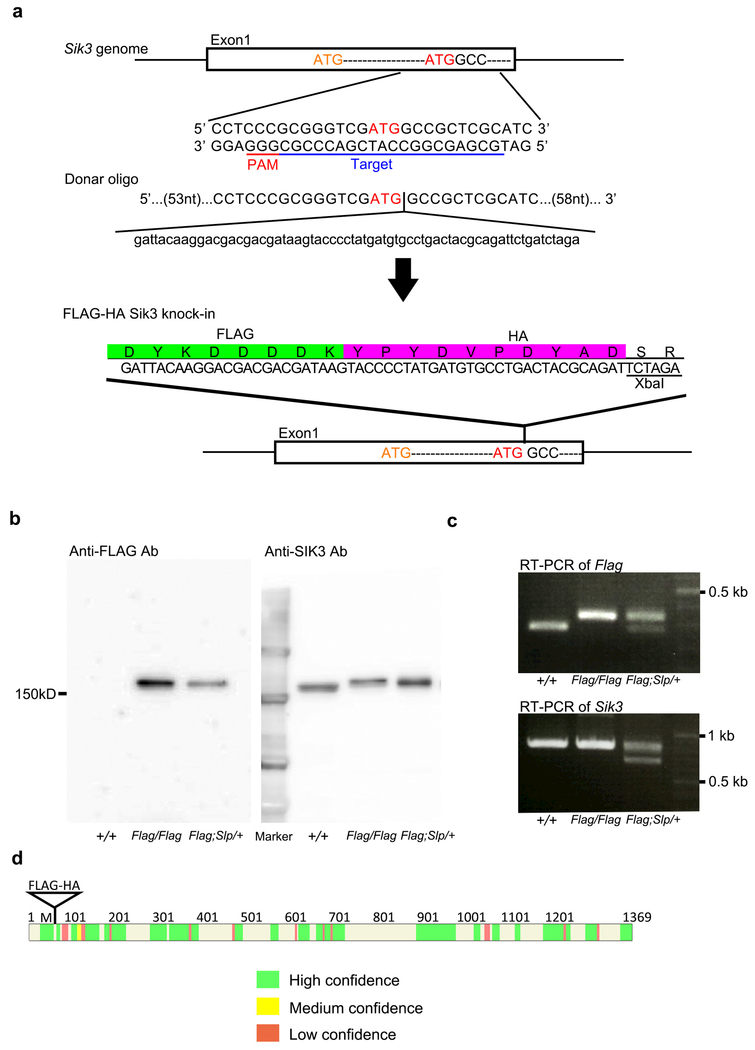

Extended Data Figure 6 |. Characterization of Flag-Sik3 mice made by CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

a, Exon 1 of the Sik3 gene contains the first and second methionine residues. The single guide RNA was designed to target the second methionine-coding region. The donor oligo has a FLAG-HA-coding sequence immediately after the second methionine and 70-nucleotide long arms at both 5’ and 3’ ends. The FLAG-HA-coding region is followed by an XbaI site. b, Immunoblotting of brain homogenates of Sik3+/+, Sik3Flag/Flag Sik3Flag,Slp/+ mice showed that anti-FLAG antibody detected FLAG-SIK3 protein of Sik3Flag/Flag brains and FLAG-SIK3(SLP) protein of Sik3Flag,Slp/+ brains, whereas anti-Sik3 antibody detected SIK3 proteins of all genotype. c, RT-PCR of brain Sik3 mRNA of Sik3+/+, Sik3Flag/Flag, Sik3Flag,Slp/+ mice. d, Tryptic peptides of immunoprecipitated and gel-purified FLAG-SIK3 protein were analyzed by LC-MS and mapped on the reference SIK3 protein. The peptide fragments were mapped on almost entire SIK3 protein with high confidence.

Extended Data Figure 7 |.

Phylogenetic conservation of SIK3 protein.

Extended Data Figure 8 |. Identification of Nalcn mutation of the Dreamless mutant pedigree.

a, Histogram of REMS episode duration in N2 littermates of Dreamless mutant pedigree (bars) and all F1 mice examined (curve). b, Haplotype analysis of chromosome 14 of Dreamless mutant pedigree with or without short REMS episode duration. c, Whole exome sequencing of Dreamless mutant N2 mice. All mice with short REMS episode duration had the single nucleotide substitution in exon 9 of the Nalcn gene.

Extended Data Figure 9 |. Sleep/wakefulness behavior of Nalcn mutant mice.

a, Representative 8s-EEG and EMG for wake, NREMS and REMS of Nalcn mutant mice b, Representative hypnogram of Nalcn+/+ mice (upper) and NalcnDrl/+ mice (lower). Wake (blue), NREMS (green) and REMS (red) are indicated from ZT0 to ZT12. c, Enlarged hypnogram of around ZT7 showed the frequent transitions between NREMS and REMS of NalcnDrl/+ mice, d, Total wake time and NREMS time of NalcnDrl/+ mice (n = 29) and Nalcn+/+ mice (n = 25). Wake, P = 0.58; NREMS, P = 0.17, One-way ANOVA. e-f, Circadian period length (e) and amplitude of circadian behavior (f) in constant darkness of NalcnDrl/+ mice (n = 6) and Nalcn+/+ mice (n = 7). Two-tailed Student’s t-test, (e) P = 0.76. (f) *** P < 0.001. g, Total REMS time of NalcnDrl/+ mice (n = 9) and Nalcn+/+ mice in constant darkness (n = 8). Two-tailed Student’s t-test. *** P < 0.001. h, EEG power spectra of NalcnDrl/+ mice (n = 29) and Nalcn+/+ mice (n = 25). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *** P < 0.001. Values are means ± sem.

Extended Data Figure 10 |. Increased conductance of NALCN(DRL).

a-c, Nalcn mRNA is expressed in the ventrolateral periaqueductal grey mater (vlPAG) and deep mesencephalic nucleus (DpMe) of the upper pons (a), the lateral dorsal tegmental nucleus (LDT) and sublateral dorsal nucleus (SLD) of the lower pons (b), and the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus (LPGi) of the medulla (c). AQ, aqueduct; dscp, decussation of superior cerebellar peduncle; IO, inferior olive; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle. Scale bars, 500 μm. d, Representative traces of membrane currents in response to ramp pulses (Vh = 0 mV, from −100 mV to +100 mV in 1 s; lower) recorded from HEK293T cells cotransfected with mUNC80, SRC(Y529F), and NALCN-GFP (upper) or NALCN(DRL)-GFP (middle). The traces are averaged from 3 trials. The transient capacitance currents are also recorded. e, Mean current density in response to ramp pulses (NALCN, n = 5, black line; NALCN(DRL), n = 7, purple line). The data from NALCN are also shown on an expanded scale (lower right). f, The charge transfer of NALCN(DRL)-transfected cells was larger than that of NALCN-transfected cells. Mann-Whitney U test.** P < 0.01. The recording data are same as in e. Values are means ± sem.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all Y/F lab and IIIS members, especially Drs. Michael Lazarus, Robert W. Greene and Kaspar E. Vogt for discussion and comments on this manuscript. J.S.T. is an Investigator and M.Y. is a former Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported by the World Premier International Research Center Initiative from MEXT to M.Y., JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 26220207 to M.Y., H.F., T.K.; 16K15187 to H.F.; 26507003 to C.M., H.F.; 15K18966, 00635089 to T.F.; 15J06369 to T.H.; 16K18583 to M.S.), MEXT KAKENHI (Grant Number; 15H05935 to M.Y., H.F.), Welch Foundation (Grant Number; I-1608 to Q.L.), NIH (Grant Number; GM111367 to Q.L.), Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST program) from JSPS to M.Y., Research grant from Uehara Memorial Foundation research grant to M.Y. and Research grant from Takeda Science Foundation research grant to M.Y.. Nematode strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). We thank A. Hart and H. Huang (Brown University) for technical advices on nematode quiescence measurement, Y. Iino (University of Tokyo) for providing plasmids, M. Ikawa for providing EGxxFP plasmid, and M. Montminy and J.B. Thomas (Salk Institute) for fly stocks.

Footnotes

Author information

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Cirelli C et al. Reduced sleep in Drosophila Shaker mutants. Nature 434, 1087–1092 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koh K et al. Identification of SLEEPLESS, a sleep-promoting factor. Science 321, 372–6 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raizen DM et al. Lethargus is a Caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like state. Nature 451, 569–572 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daan S, Beersma DG & Borbely, a a. Timing of human sleep: recovery process gated by a circadian pacemaker. Am. J. Physiol. 246, R161–83 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franken P, Chollet D & Tafti M The homeostatic regulation of sleep need is under genetic control. J. Neurosci. 21, 2610–21 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki A, Sinton CM, Greene RW & Yanagisawa M Behavioral and biochemical dissociation of arousal and homeostatic sleep need influenced by prior wakeful experience in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 10288–93 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu J, Sherman D, Devor M & Saper CB A putative flip-flop switch for control of REM sleep. Nature 441, 589–94 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saper CB, Scammell TE & Lu J Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature 437, 1257–63 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luppi PH et al. The neuronal network responsible for paradoxical sleep and its dysfunctions causing narcolepsy and rapid eye movement (REM) behavior disorder. Sleep Medicine Reviews 15, 153–163 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu M et al. Basal forebrain circuit for sleep-wake control. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1641–1647 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adamantidis AR, Zhang F, Aravanis AM, Deisseroth K & de Lecea L Neural substrates of awakening probed with optogenetic control of hypocretin neurons. Nature 450, 420–4 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrera CG et al. Hypothalamic feedforward inhibition of thalamocortical network controls arousal and consciousness. Nat. Neurosci. 1–12 (2015). doi: 10.1038/nn.4209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter ME et al. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1526–33 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber F et al. Control of REM sleep by ventral medulla GABAergic neurons. Nature (2015). doi: 10.1038/nature14979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi Y et al. Cells of a common developmental origin regulate REM/non-REM sleep and wakefulness in mice. Science 350, 957–61 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi JS, Shimomura K & Kumar V Searching for genes underlying behavior: lessons from circadian rhythms. Science 322, 909–12 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Citri Y et al. A family of unusually spliced biologically active transcripts encoded by a Drosophila clock gene. Nature 326, 42–47 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King DP et al. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian clock gene. Cell 89, 641–653 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allada R, Emery P, Takahashi JS & Rosbash M Stopping time: the genetics of fly and mouse circadian clocks. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1091–119 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar V et al. C57BL/6N mutation in Cytoplasmic FMRP interacting protein 2 regulates cocaine response. Science 342, 1508–12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takemori H & Okamoto M Regulation of CREB-mediated gene expression by salt inducible kinase. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 108, 287–291 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vyazovskiy VV et al. Local sleep in awake rats. Nature 472, 443–447 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katoh Y et al. Silencing the constitutive active transcription factor CREB by the LKB1-SIK signaling cascade. FEBSJ. 273,2730–48 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berggreen C, Henriksson E, Jones H. a., Morrice N & Goransson O cAMP-elevation mediated by β-adrenergic stimulation inhibits salt-inducible kinase (SIK) 3 activity in adipocytes. Cell. Signal. 24,1863–71 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flourakis M et al. A Conserved Bicycle Model for Circadian Clock Control of Membrane Excitability. Cell 162, 836–848 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren D Sodium leak channels in neuronal excitability and rhythmic behaviors. Neuron 72, 899–911 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu B et al. Peptide neurotransmitters activate a cation channel complex of NALCN and UNC-80. Nature 457, 741–4 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu B et al. Extracellular calcium controls background current and neuronal excitability via an UNC79-UNC80-NALCN cation channel complex. Neuron 68, 488–99 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crochet S, Onoe H & Sakai K A potent non-monoaminergic paradoxical sleep inhibitory system: A reverse microdialysis and single-unit recording study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24,1404–1412 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sapin E et al. Localization of the brainstem GABAergic neurons controlling paradoxical (REM) sleep. PLoS One 4, e4272 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan KS & Nash H a. A genetic study of the anesthetic response: mutants of Drosophila melanogaster altered in sensitivity to halothane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87, 8632–6 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lear BC et al. The ion channel narrow abdomen is critical for neural output of the Drosophila circadian pacemaker. Neuron 48, 965–976 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joiner WJ et al. Genetic and Anatomical Basis of the Barrier Separating Wakefulness and Anesthetic-Induced Unresponsiveness. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003605 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funato H et al. Loss of Goosecoid-like and DiGeorge syndrome critical region 14 in interpeduncular nucleus results in altered regulation of rapid eye movement sleep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 18155–18160 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franken P, Malafosse A & Tafti M Genetic variation in EEG activity during sleep in inbred mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275, R1127–R1137 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Funato H, Saito-Nakazato Y & Takahashi H Axonal growth from the habenular nucleus along the neuromere boundary region of the diencephalon is regulated by semaphorin 3F and netrin-1. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 16, 206–20 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mashiko D et al. Generation of mutant mice by pronuclear injection of circular plasmid expressing Cas9 and single guided RNA. Sci. Rep. 3, 3355 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu B et al. The neuronal channel NALCN contributes resting sodium permeability and is required for normal respiratory rhythm. Cell 129, 371–83 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang B et al. A hormone-dependent module regulating energy balance. Cell 145, 596–606 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kume K, Kume S, Park SK, Hirsh J & Jackson FR Dopamine is a regulator of arousal in the fruit fly. J. Neurosci. 25, 7377–84 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osterwalder T, Yoon KS, White BH & Keshishian H A conditional tissue-specific transgene expression system using inducible GAL4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 12596–12601 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanjuin A & Sengupta P Regulation of chemosensory receptor expression and sensory signaling by the KIN-29 Ser/Thr kinase. Neuron 33, 369–381 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh K et al. C. elegans Notch signaling regulates adult chemosensory response and larval molting quiescence. Curr. Biol. 21, 825–34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.