Abstract

Introduction

Xylitol (or ‘birch sugar’) is a naturally occurring sugar with antibacterial properties that has been used as a natural non-sugar sweetener in chewing gums, confectionery, toothpaste and medicines. In this preventative randomised trial, xylitol will be tested for the prevention of acute otitis media (AOM), a common and costly condition in young children. The primary outcome will be the incidence of AOM. Secondary outcomes will include upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and dental caries.

Methods and analysis

This study will be a pragmatic, blinded (participant and parents, practitioners and analyst), two-armed superiority, placebo-controlled randomised trial with 1:1 allocation, stratified by clinical site. The trial will be conducted in the 11 primary care group practices participating in the TARGet Kids! research network in Canada. Eligible participants between the ages of 2–4 years will be randomly assigned to the intervention arm of regular xylitol syrup use or the control arm of regular sorbitol use for 6 months. We expect to recruit 236 participants, per treatment arm, to detect a 20% relative risk reduction in AOM episodes. AOM will be identified through chart review. The secondary outcomes of URTIs and dental caries will be identified through monthly phone calls with specified questions.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval from the Research Ethics Boards at the Hospital for Sick Children and St. Michael’s Hospital has been obtained for this study and also for the TARGet Kids! research network. Results will be submitted for publication to a peer-reviewed journal and will be discussed with decision makers.

Trial registration number

NCT03055091; Pre-results.

Keywords: otitis media, upper respiratory tract infection, dental caries, xylitol, sorbitol

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first pragmatic trial in Canada determining whether regular xylitol syrup use is effective in preventing acute otitis media (AOM) in children under the age of 4 years (who are most likely to have AOM).

The trial will be conducted through the TARGet Kids! primary care research network allowing for a multicentre study performed through routine primary care visits.

The 6 months of treatment and outcome assessment will allow the evaluation of the long-term effects of xylitol.

A challenge for trials with AOM as an outcome is that parents may not distinguish AOM from other upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) with similar symptoms and may not seek care; we will include both clinician-diagnosed AOM and parent-reported URTIs as separate outcomes.

Introduction

Acute otitis media (AOM) is a common and costly condition in young children.1 The annual global incidence of AOM is 700 million per year and 50% of those affected are children under the age of 5 years.2 By age 3 years, 84% of children have had at least one episode of AOM and 46% have had three or more episodes.3 Antibiotic treatment has only a modest effect on AOM duration4 and does not prevent serious complications such as mastoiditis or meningitis which can rarely be fatal.5 6 Most (>80%) children with AOM presenting for care have spontaneous symptom resolution within 3 days and the number needed to treat for antibiotic treatment to reduce symptom duration is 20 days, which must be balanced by a number needed to harm (with adverse effects of antibiotics such as diarrhoea) of 14 days.4 The incidence of mastoiditis has not changed over time despite changes in antibiotic prescribing.5–7 Rare sequelae of AOM include delayed cognitive development, impaired communication skills and permanent hearing loss.3 Parents of children with otitis media report missing 2–3 days of work per episode.1

Another common and costly infectious disease among North American preschool aged children is upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs).8–12 URTIs are the most common reason for emergency department visits and unscheduled outpatient visits in Canada, accounting for 10% of emergency department visits for children under 10 years of age.13–15 URTIs are also the most common reason for unscheduled visits to a care provider and Canadian children experience 3–8 URTIs per year at a cost to the healthcare system of several hundred million dollars per year.16–18

Nearly 30% of children aged 2–5 years have dental caries.19 Dental caries may lead to pain, difficulty eating and speaking and can harm a child’s self-esteem.20 Treating dental caries in young children is challenging for practitioners, painful for the children and caries cost thousands of dollars to treat, with complicated caries requiring hospitalisation costing several times more (and rarely resulting in death).21–26

In vitro studies have shown that xylitol can reduce the attachment of bacteria that cause AOM, URTIs and dental caries such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae to nasopharyngeal cells. AOM occurs when the upper airway is colonised with bacteria, viruses or a combination of both that travel from the nasopharynx to the middle ear by way of the Eustachian tube.27 A Cochrane systematic review of the safety and efficacy of xylitol in preventing AOM in children up to 12 years of age found that there is fair evidence supporting the use of xylitol for the prevention of AOM (risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI 0.65 to 0.88 based on 3 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from the same research group, studying 1826 children in total), but concluded that an adequately powered, well-designed trial is necessary.28 Previous trials have not established whether regular xylitol syrup use is effective at preventing AOM in young children (<4 years) who are most likely to have AOM. Several RCTs of xylitol for the prevention of dental caries indicate that the antimicrobial effect of xylitol (which is posited to account for its efficacy in preventing AOM) increases with duration of use.29–31 Therefore, the effect of the same dose of xylitol may be more effective at preventing AOM over the 6-month study period in the proposed study than it was in the previous trials that lasted 2 or 3 months.32 The longer trials of xylitol for the prevention of dental caries also demonstrate that daily xylitol administration is safe, feasible and well tolerated for the 6-month study period in the proposed trial.29–31 A pilot study of higher concentrations of xylitol syrup in young children found good compliance and tolerability.33 In summary, regular xylitol syrup used for the 6-month study period is safe and feasible, and there is clinical equipoise over its effectiveness at preventing AOM in young children. There is no recommendation for or against the use of xylitol in the USA or in Canada. The paucity of high-quality RCTs has been cited as a reason for the lack of consistent recommendations regarding the use of xylitol in young children.34

The primary purpose of this study is to determine if regular use of xylitol syrup effectively prevents AOM in unselected children aged 2–4 years. Such an intervention could increase the productivity of parents and caregivers, reduce serious complications and reduce the suffering of young children—each episode of AOM involves several excess hours of crying for 2–7 days.35 This trial could change clinical practice if the results are positive. In several other countries, xylitol is recommended for the prevention of dental caries. For example, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentists recommends regular xylitol use for the prevention of dental caries based on the results of eight clinical trials.36 However, a survey of American paediatricians found that few physicians (12%) recommend xylitol to patients and that most would either definitely (68%) or possibly (29%) recommend xylitol if there was additional evidence that it prevented AOM.37

Aims and objectives

Primary question

Does regular xylitol syrup use for 6 months reduce the number of physician-diagnosed AOM episodes in children aged 2–4 years?

Secondary questions

Does regular xylitol syrup use reduce the number of parent-reported URTI episodes in children aged 2–4 years?

Does regular xylitol syrup use reduce parent-reported dental caries in children aged 2–4 years?

Methods and analysis

Study design

This will be a pragmatic, blinded (participant and parents, practitioners and analyst), two-armed superiority, placebo-controlled randomised trial with 1:1 allocation, stratified by clinical site.

Setting

The trial will be conducted in the 11 primary care group practices currently participating in the TARGet Kids! research network (www.targetkids.ca) in Canada. There are no sites outside of Canada.

Eligibility criteria

The patients in this study are healthy children aged 2–4 years who are participants of The Applied Research Group for Kids (TARGet Kids!), the largest paediatric primary care practice-based research network in Canada focused on child health (www.targetkids.ca).

Inclusion criteria

Children aged 24–48 months at start of intervention, and parent or care provider able to give consent for participation including being able to understand the information provided in English. All children recruited to this study will also be participants in the TARGet Kids! research network.

Exclusion criteria

Craniofacial malformations, structural middle ear abnormalities, sibling or any other child living at the same address already enrolled in the trial (in order to prevent contamination), insertion of ventilation tubes prior to study period, current use of a xylitol product or reported xylitol sensitivity.

Consent

Consent will be obtained by one of two methods:

For participants with an upcoming scheduled health visit: an invitation to participate will be mailed to participants along with the consent form 2 weeks prior to their scheduled health visit. At the visit, a trained TARGet Kids! Research Assistant will review the eligibility criteria and the consent form with the parents/caregivers. Research Assistants will answer any questions in person.

For eligible TARGet Kids! participants without a scheduled visit: an invitation to participate will be mailed to participants along with the consent form. Parents/caregivers will have the opportunity to contact the Study Coordinator at any time (by email/phone) to answer questions. The consent form will be mailed back to the site.

Any participant that no longer wishes to participate in TARGet Kids! will not be approached.

Intervention arm

Xylitol (or ‘birch sugar’) is a naturally occurring sugar with antibacterial properties that has been used as a natural non-sugar sweetener in chewing gums, confectionery, toothpaste and medicines.27 38 39

The investigational agents will be provided by XLEAR, a producer of commercial xylitol products that are sold in Canada. The product specifications used for this agent is that of their syrup or ‘tooth gel’ products sold in 60 mL tubes. The product is approved by Health Canada as a food additive. The product has a shelf life of 2 years based on stability studies. Each tube is labelled with a best before date and a lot number on the tube crimp.

The experimental intervention is the provision of xylitol syrup (35% xylitol concentration per weight) and instructions to ingest is 3–5 times per day. Each dose will be 5 mL of 350 g/L, therefore the maximum possible daily dose will be 9 g of xylitol per day. This is the daily dose that may be effective from previous trials.32

Control arm

The control intervention is the provision of sorbitol syrup (looks, smells and tastes like the xylitol syrup but is not an antimicrobial). Sorbitol is unlikely to have an effect on our primary outcome of AOM or the secondary outcomes of URTIs and dental caries; therefore, it can be used as a placebo. The sorbitol syrup formulation is the same as the xylitol syrup except the concentration of sorbitol will be 30% by weight. The instructions for use are 3–5 times per day. Each dose will be 5 mL of 300 g/L of sorbitol; therefore, the maximum daily dose will be 7.5 g of sorbitol.

XLEAR will produce the investigational agents through a dedicated production run and ship the products to the research pharmacy in a timely manner. This will allow preparation and shipment of the kits for each participant prior to the intervention period.

The data coordinating centre will create master randomisation tables and send these to the research pharmacy for dispensing. The study statistician will create the master randomisation table using a computer-generated, site-stratified, block randomisation design. The research pharmacy will use the randomisation table for the dispensation of the investigational agents to each participant.

Intervention period

The treatment period will be 6 months for all participants. The intervention will be given during the winter season.

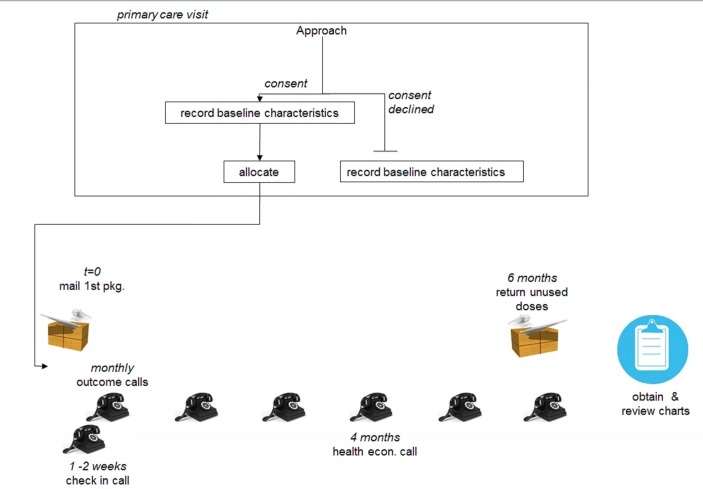

The follow-up period is identical to the treatment period, and so will also be 6 months for all participants (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline for intervention and follow-up.

Conducting the trial during winter months will maximise the efficiency of the trial because AOM and URTI incidences are highest during that time.40 Since xylitol is not a treatment for infections, care will be provided as normal for any suspected infections.

Premature withdrawal/discontinuation criteria

Xylitol is sweet and children generally enjoy consuming it.33 The number of missed doses in previous trials with frequent daily dosing was around 10%.

Parents will be called 2 weeks after they have been given the package to discuss any challenges with compliance, as well as during monthly follow-up calls.

Based on data from previous trials conducted in the TARGet Kids! research network and the fact that the primary outcome will be determined using a chart review, we anticipate a low (<5%) rate of being lost to follow-up in this trial where follow-up does not require any special visits for research purposes only. If a participant leaves the primary care practice, we will attempt to obtain the name of the current care provider and obtain the chart for review. If a participant has left the primary care practice and we are unable to contact the parents or caregivers, we will treat the data as missing. Despite this, the sample size calculation assumes 10% of participants will not complete follow-up.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of the total number of physician-diagnosed AOM episodes will be assessed by reviewing charts of the primary care provider and any other care providers reported by parents or caregiver at monthly phone calls.

Three methods for determining the diagnosis of AOM have been used in trials: clinical signs (bulging and red tympanic membrane), clinical signs with tympanometry and clinical signs with tympanocentesis.41 In this trial, the number of AOM episodes will be assessed using both objective clinical signs of AOM recorded in the chart and a physician’s diagnosis of AOM. In order to make a diagnosis of AOM for this trial, the chart must contain both the documentation of signs of AOM (eg, erythematous tympanic membrane) plus the practitioners’ diagnosis that the patient had AOM. The addition of tympanometry to clinical signs does not necessarily improve the accuracy of AOM diagnosis.42 Although tympanometry is recommended by some guidelines, it is not employed in routine clinical practice at any of the TARGet Kids! sites. Tympanocentesis is therapeutic and can prevent subsequent AOM episodes41 so it cannot be used in this trial of AOM prevention (and it requires instruments not present in primary care sites). Four of the five previous trials of xylitol for the prevention of AOM employed clinical signs with tympanometry, and one used clinical signs to determine the number of AOM episodes.32

Previous RCTs of AOM management in young children have relied on the diagnoses made by primary care providers (who are generally the clinicians who diagnose AOM for clinical purposes).43 44 The studies, involving longer study periods, used chart reviews to determine the number of AOM episodes just as we will in this trial (see online supplementary appendix 1).44

bmjopen-2017-020941supp001.pdf (220.2KB, pdf)

We have conducted a chart review of 1637 patients in the TARGet Kids! research network using a method similar to those in completed RCTs of AOM that involves reviewing charts for physical examination findings consistent with AOM and a diagnosis or assessment of AOM.43–45 In all of the episodes, the physical examination findings and the diagnosis were clearly documented in the chart (the term ‘AOM’ was usually recorded in the assessment portion of the note), and there was perfect agreement between independent reviewers.

In addition to reviews of the patient’s primary care provider medical record, the primary outcome will also include AOM episodes diagnosed by other care providers (eg, at walk-in clinics or emergency rooms). Parental consent for release of this information will be obtained, and charts will be reviewed on the end of follow-up period.

The primary analysis will be the total number of AOM episodes during the study period. We will also summarise the time to first AOM using survival curves.

A limitation of employing physician-diagnosed episodes of AOM is that parents may not seek care when their child has AOM symptoms. This limitation is addressed with the secondary outcome of parent-reported URTIs (see secondary outcomes below). Another limitation of physician-diagnosed AOM is that there is variability in the diagnosis of AOM by clinicians, with one study of administrative data indicating that some clinicians diagnose AOM twice as often as others.41 46 47 Since the clinicians will be blinded to the allocated group, differences in clinical assessment will not bias the results. If there is a substantial number of incorrect physician diagnosed episodes of AOM (false positives), there results will be biased against the efficacy of xylitol.

Note that our sample size calculation incorporates the incidence of AOM in the TARGet Kids! study population and so it takes into consideration the rate of AOM diagnosis by the same clinicians who will diagnose AOM in these study participants.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome parent-reported URTI episodes will be assessed during monthly phone calls. A challenge in all trials that employ AOM as an outcome is the combined effect of two factors: (1) parents often decide not to seek care when a child has symptoms that may indicate AOM and (2) parents cannot distinguish between AOM and other URTIs because the symptoms are similar. We will address this challenge with our secondary outcome: parent-reported URTIs, a very common and costly (in aggregate) condition in early childhood.17 48 The previous shorter (2–3 months) trials of xylitol found a non-significant trend towards fewer URTI episodes in children receiving xylitol.32

A cohort study of children aged 2 months to 12 years receiving care at Toronto primary care sites found that medical consultation was sought in only 56% of episodes of URTI symptoms.49 This is not surprising given that guidelines recommend against antibiotics for AOM and other URTIs in many cases. As many parents are aware of this recommendation from previous clinic visits, they may decide to treat children with analgesics and antipyretics without seeking care even if they believe the child has an AOM.50 Thus, information about the total number of URTI episodes must be obtained directly from parents and caregivers as it will not be found in a patient’s medical record even if it includes records from all institutions and clinics.

Parents may not diagnose AOM accurately based on symptoms because they overlap substantially with symptoms of URTIs.51 Irritability and crying are the most common symptoms in AOM and URTI episodes.52 Forty per cent of children with AOM do not have an ear ache and 31% do not have a fever,51 while 72% of children without AOM exhibit symptoms of AOM (crying, fever or ear ache).52

Like previous studies, we will employ structured telephone interviews to assess the number of URTI episodes.53–55 Parents or caregivers will be contacted every month and asked to report the number of URTIs the child has experienced since the last call (or since the beginning of the trial for the first call) using validated questions (see online supplementary appendix 1).55 We will employ the symptoms in the Canadian Acute Respiratory Illness and Influenza scale that has been validated in this population.56

The secondary outcome, parent-reported dental caries, will also be assessed during the monthly phone calls. Parents or caregivers will be asked if they have been informed by a dentist or a physician that their child has or has had at least one or more dental caries (see online supplementary appendix 1). This question has been used and validated in several epidemiological studies.57–60 The dental caries secondary outcome will be binary (at least one vs none). Those with caries at baseline will be excluded from this analysis but included in all other analyses.

Other measures

Health economics measures will be collected for an economic evaluation. We will compare the cost-effectiveness of the xylitol syrup against the control group using the net benefit regression framework from the perspective of the parents (who will be the payer for the syrup).61 Costs will include costs incurred to the parents or caregivers such as their usual mode of transportation for attending medical appointments (collected during an extended phone call at the 4-month call).61 The parent or caregiver hours of productivity (including employment) lost due to the child’s AOM episodes (including, eg, the days the child could not attend daycare) will also be assessed during the monthly calls. The use of net benefit regression allows the economic evaluation to be conducted using regression methods (adjusting for potential confounders). The main outcome of the economic evaluation will be an incremental net benefit of xylitol syrup (in terms of cost and number of physician-diagnosed AOM episodes) compared with control. In addition, we will estimate incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (eg, an incremental cost per one physician-diagnosed AOM episode avoided and an incremental cost per one URTI episode avoided). Statistical uncertainty will be characterised using a 95% CI and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.62

Compliance (reported number of doses given per week) will be assessed during the monthly calls and by tallying the number of returned doses at the end of the study.

Sample size rationale

We used the results of three previous RCTs of xylitol for the prevention of AOM and data from participants in the TARGet Kids! research network to estimate the sample size.

In a chart review of TARGet Kids! research network participants, we found a comparable event rate as the control groups in the trials above: 670 episodes of AOM in 1637 patients (41%) over a 3-month period (0.14 AOM episodes per patient-month).

Since the data currently available suggest that the AOM rate is about 1.6 episodes per patient-year, we will somewhat conservatively assume a control event rate of 1.5. We will aim to detect a relative risk of 0.8 (ie, relative risk reduction (RRR) of 20%) with 80% power and alpha=0.05 (two-sided). A 20% RRR was chosen based on previous surveys of reasons physicians do not currently recommend xylitol and the RRR used in previous trials.32 37 The sample size calculations assumed a Poisson distribution for the number of AOM episodes and were based on the asymptotic distribution of the likelihood ratio test statistic. Calculations were performed in R (V.2.15.3) using the asypow package and power was confirmed via 10 000 simulations. The required sample size is 236 per group. (Note that while the number of participants is less than one of the previous trials,63 the mean treatment and follow-up period in our study will be longer.) The above calculations take into consideration non-compliance and a loss to follow-up of 10% of participants only completing 50% of the follow-up period. These calculations assume there will be no substantial contamination. While xylitol preparations are commercially available, the dose of xylitol is less than one-tenth the dose found in trials to be effective at preventing AOM. A survey of TARGet Kids! participants showed that xylitol use is rare (<5%). Siblings of those already enrolled in the trial will be excluded since contamination would be likely if two members of the family are enrolled and allocated to different arms.

We expect to recruit 40 participants per month. Thus, sufficient patients will be recruited during two calendar years for the intervention to take place over two winter seasons. A previous RCT in the TARGet Kids! research network with similar inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria and recruitment strategy successfully recruited >66 children each month for 2 years when the network was smaller.64 Parents of children who are participating in the TARGet Kids! research network’s longitudinal study will be approached by research assistants regarding this RCT during routine primary care visits throughout the year. Randomisation will take place just before the intervention begins so the small number of patients who are recruited but leave the practice before the intervention period will not be randomised.

We will determine if xylitol is more effective in younger children (aged 24–36 months vs >36 months at time of recruitment).

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis will be performed based on the intention-to-treat population. The primary outcome will be analysed with a Poisson regression model. To account for participants who do not complete the entire planned follow-up and slight variations in the observation time for completers, the logarithm of follow-up time will be added as an offset term to the model. The treatment effect, expressed as a rate ratio (relative risk), and 95% CI will be obtained from the model. A secondary analysis will adjust for characteristics with an imbalance between groups at baseline. Patient demographics will be summarised descriptively (eg, means and SD or median and IQR for continuous variables and frequency and percentages for categorical). Although randomisation guarantees balance in the long-run, there is a chance of imbalances in any sample. The demographics will be reviewed for clinically important imbalances that may be adjusted for in a secondary analysis. The secondary outcomes, number of URTI episodes and dental caries, will be analysed similarly to the primary outcome.

Safety analysis

A data safety monitoring board is not necessary because xylitol has been demonstrated to be safe in previous trials for the prevention of AOM and dental caries, and the maximum possible efficacy can be estimated from previous trials. We therefore do not anticipate any reason to stop the trial early.

Xylitol can rarely cause osmotic diarrhoea and abdominal discomfort. In previous trials, approximately 1% of children exposed to xylitol experienced diarrhoea and slightly <1% of children exposed to control substances (eg, sorbitol) experienced diarrhoea (difference not statistically significant).45 The vast majority of children, including those aged 2–4 years, are able to tolerate total daily doses of 45 g of xylitol without significant gastrointestinal side effects.32 35 The maximum total daily dose of xylitol in this trial will be 10 g/day.

In previous trials, a total of >1000 children were exposed to various formulations of xylitol or control substances and there were no reported episodes of choking or aspiration. The control intervention is the provision of sorbitol syrup which can cause diarrhoea but at similar rates as xylitol.65 Despite this, the consent form will alert parents to the potential of diarrhoea.

Adverse events

All adverse events will be reported to the Hospital for Sick Children or St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board according to their adverse event reporting requirements. All adverse drug reactions to the study medication will be reported to Health Canada within 15 calendar days or for death or life-threatening events, within 7 calendar days. In the latter case, a follow-up report must be filed within 8 calendar days. Serious adverse events and serious unexpected adverse events will be reported to the Natural and Non-prescription Health Products Directorate in an expedited manner.

To maintain the overall quality of the trial, unblinding will only be performed in exceptional circumstances when knowledge of the actual treatment is essential for management of the patient. If unblinding is deemed to be necessary by the investigator, the investigator will contact the coordinating centre by telephone to ascertain the allocation group and communicate this to the participant’s clinician and caregiver. The research staff will not be informed of the allocation group. Unblinding will not necessarily be a reason for discontinuation or exclusion from the analysis.

Management

The Applied Health Research Centre will be responsible for trial data coordination, database development, data management and statistical analysis. Study data and patient surveys will be entered and maintained on a secure password protected database developed using REDCap (www.project-redcap.org) and will be accessible via the internet for data entry purposes. Quality and completeness of data entry will be reviewed as soon as possible after data entry, within 5 business days of data entry for the first 5 participants randomised at each site, and within 15 days of data entry thereafter. Corrections or changes in REDCap are tracked with the retention of the original data and the corrected data with the date of data entry and submitting personnel.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the development of the research question or the design of the study. A written summary of the study results will be sent to participants by email or by mail. The burden of the intervention on patients was not assessed prior to the start of the trial.

Ethics and dissemination

The results of the study will be submitted for publication to a peer-reviewed journal and will be discussed by policy and decision makers.

Summary

In summary, AOM, URTIs and dental caries are common and costly conditions in young children that might be prevented by regular xylitol use. Existing evidence indicates clinical equipoise on the efficacy of xylitol syrup in preventing AOM, URTIs and dental caries in preschool aged children. Evidence from previous long-term trials of xylitol for the prevention of dental caries has demonstrated that the intervention is well tolerated and feasible in this age group. The TARGet Kids! research network has a demonstrated record of conducting RCTs in young children and its existing research infrastructure will be mobilised to ensure that this trial will be completed efficiently and on schedule.

AOM and URTIs are commonly viewed as unavoidable during early childhood. This trial has the potential to transform the approach to these three common conditions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributor: Co-Leads : Catherine S. Birken, Jonathon L. Maguire; Advisory Committee : RonaldCohn, Eddy Lau, Andreas Laupacis, Patricia C. Parkin, Michael Salter, PeterSzatmari, Shannon Weir; Science Review and Management Committees: Laura N. Anderson, Cornelia M. Borkhoff, Charles Keown-Stoneman, Christine Kowal, Dalah Mason; Site Investigators : Murtala Abdurrahman, Barbara Anderson, Kelly Anderson, Gordon Arbess, Jillian Baker, Tony Barozzino, Sylvie Bergeron, Dimple Bhagat, Nicholas Blanchette, Gary Bloch, JoeyBonifacio, Ashna Bowry, Anne Brown, Jennifer Bugera, Caroline Calpin, DouglasCampbell, Sohail Cheema, Elaine Cheng, Brian Chisamore, Evelyn Constantin, Ellen Culbert, Karoon Danayan, Paul Das, Mary Beth Derocher, Anh Do, MichaelDorey, Kathleen Doukas, Anne Egger, Allison Farber, Amy Freedman, SloaneFreeman, Sharon Gazeley, Charlie Guiang, Dan Ha, Curtis Handford, LauraHanson, Leah Harrington, Hailey Hatch, Teresa Hughes, Sheila Jacobson, Lukasz Jagiello, Gwen Jansz, Mona Jasuja, Paul Kadar, Tara Kiran, HollyKnowles, Bruce Kwok, Sheila Lakhoo, MargaritaLam-Antoniades, EddyLau, Denis Leduc, Fok-Han Leung, Alan Li, Patricia Li, Jennifer Loo, JoanneLouis, Sarah Mahmoud, Jessica Malach, Roy Male, Vashti Mascoll, Aleks Meret, EliseMok, Rosemary Moodie, Julia Morinis, Maya Nader, Katherine Nash, SharonNaymark, James Owen, Jane Parry, Michael Peer, Kifi Pena, Marty Perlmutar, Navindra Persaud, Andrew Pinto, Michelle Porepa, Vikky Qi, Nasreen Ramji, NoorRamji, Jesleen Rana, Danyaal Raza, Alana Rosenthal, Katherine Rouleau, JanetSaunderson, Rahul Saxena, Vanna Schiralli, Michael Sgro, Hafiz Shuja, SusanShepherd, Barbara Smiltnieks, Cinntha Srikanthan, Carolyn Taylor, StephenTreherne, Suzanne Turner, Fatima Uddin, Meta van denHeuvel, JoanneVaughan, Thea Weisdorf, Sheila Wijayasinghe, Peter Wong, Anne Wormsbecker, JohnYaremko, Ethel Ying, Elizabeth Young, Michael Zajdman; Research Team : Farnaz Bazeghi, VincentBouchard, Marivic Bustos, Charmaine Camacho, Dharma Dalwadi, ChristineKoroshegyi, Tarandeep Malhi, Sharon Thadani, Julia Thompson, Laurie Thompson; Project Team : Mary Aglipay, ImaanBayoumi, Sarah Carsley, Katherine Cost, Karen Eny, Theresa Kim, Laura Kinlin, Jessica Omand, ShelleyVanderhout, Leigh Vanderloo; Applied Health Research Centre : Christopher Allen, Bryan Boodhoo, Olivia Chan, David W.H. Dai, JudithHall, Peter Juni, Gerald Lebovic, Karen Pope, Kevin Thorpe; Mount Sinai Services Laboratory : Rita Kandel, Michelle Rodrigues, Hilde Vandenberghe.

Contributors: The following authors contributed substantially to conception and the design of the protocol: NP, AL, AA, CB, JSH, WI, JLM, MMM, KT, CA, DM, CK, FB and PP. The following authors drafted the manuscript: NP and FB. The following authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: NP, AL, AA, CB, JSH, WI, JLM, MMM, KT, CA, DM, CK, FB and PP. The following authors approved the final manuscript: NP, AL, AA, CB, JSH, WI, JLM, MMM, KT, CA, DM, CK, FB and PP. The following authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: NP, AL, AA, CB, JSH, WI, JLM, MMM, KT, CA, DM, CK, FB and PP. Members of the TARGet Kids! contribute to data collection and provide general input on research directions.

Funding: The study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). NP received salary support from a CIHR RCT training grant and from a PSI Graham Farquharson Knowledge Translation Fellowship. There was no role of the manufacturer in the concept, design, implementation, data collection and analysis and permission to publish. The products were purchased from the manufacturer using public research funding.

Disclaimer: The agencies had no role in the design, collection, analyses or interpretation of the results of this study or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: There are no competing interests. PP reports receiving the following grants unrelated to this study: a grant from Hospital for Sick Children Foundation during the conduct of the study; a grant from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN # 115059) for an ongoing investigator initiated trial of iron deficiency in young children, for which Mead Johnson Nutrition provides non-financial support (Fer-In-Sol liquid iron supplement).

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The TARGet Kids! research platform has been approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Hospital for Sick Children and St Michael’s Hospital, as well as the other affiliated sites. Ethics approval for this study has been obtained for all participating sites.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: The TARGet Kids! Collaboration.

References

- 1. Dubé E, De Wals P, Gilca V, et al. Burden of acute otitis media on Canadian families. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:60–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One 2012;7:e36226 10.1371/journal.pone.0036226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Teele DW, Klein JO, Rosner B. Epidemiology of otitis media during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study. J Infect Dis 1989;160:83–94. 10.1093/infdis/160.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Venekamp RP, Sanders S, Glasziou PP, et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:CD000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anthonsen K, Høstmark K, Hansen S, et al. Acute mastoiditis in children: a 10-year retrospective and validated multicenter study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013;32:436–40. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828abd13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palma S, Bovo R, Benatti A, et al. Mastoiditis in adults: a 19-year retrospective study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2014;271:925–31. 10.1007/s00405-013-2454-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kvaerner KJ, Austeng ME, Abdelnoor M. Hospitalization for acute otitis media as a useful marker for disease severity. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013;32:946–9. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318297c436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heikkinen T, Järvinen A. The common cold. Lancet 2003;361:51–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lambert SB, Allen KM, Druce JD, et al. Community epidemiology of human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus NL63, and other respiratory viruses in healthy preschool-aged children using parent-collected specimens. Pediatrics 2007;120:e929–e937. 10.1542/peds.2006-3703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lambert SB, Allen KM, Carter RC, et al. The cost of community-managed viral respiratory illnesses in a cohort of healthy preschool-aged children. Respir Res 2008;9:11 10.1186/1465-9921-9-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kvaerner KJ, Nafstad P, Jaakkola JJ. Upper respiratory morbidity in preschool children: a cross-sectional study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;126:1201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epidemiology HJO. pathogenesis, and treatment of the common cold. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases 1998;9:50–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burt CW, McCaig LF, Rechtsteiner EA. Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2005. Adv Data 2007;388:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TW. Hospitalization attributable to influenza and other viral respiratory illnesses in Canadian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25:795–800. 10.1097/01.inf.0000232632.86800.8c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Canadian Institute of Health Information. National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Public Health Agency of Canada. Economic Burden of Illness in Cananda, 2005-2008, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas EM. Recent trends in upper respiratory infections, ear infections and asthma among young Canadian children. Health Rep 2010;21:47-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TW. Role of influenza and other respiratory viruses in admissions of adults to Canadian hospitals. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2008;2:1–8. 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2008.00035.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Center for Caries Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Oral Health Resources - Children’s Oral Health Overview 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nunn ME, Dietrich T, Singh HK, et al. Prevalence of early childhood caries among very young urban Boston children compared with US children. J Public Health Dent 2009;69:156–62. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2008.00116.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Griffin SO, Gooch BF, Beltrán E, et al. Dental services, costs, and factors associated with hospitalization for Medicaid-eligible children, Louisiana 1996-97. J Public Health Dent 2000;60:21–7. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb03287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Casamassimo PS, Thikkurissy S, Edelstein BL, et al. Beyond the dmft: the human and economic cost of early childhood caries. J Am Dent Assoc 2009;140:650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ettelbrick KL, Webb MD, Seale NS. Hospital charges for dental caries related emergency admissions. Pediatr Dent 2000;22:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Colak H, Dülgergil CT, Dalli M, et al. Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2013;4:29–38. 10.4103/0976-9668.107257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Association of Dental Surgeons of British Columbia. Children’s dentistry task force report, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bertness JH, Promoting awareness K. preventing pain: Facts on early childhood caries (ECC). 2nd ed: National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kontiokari T, Uhari M, Koskela M. Antiadhesive effects of xylitol on otopathogenic bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998;41:563–5. 10.1093/jac/41.5.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Azarpazhooh A, Lawrence HP, Shah PS. Xylitol for preventing acute otitis media in children up to 12 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;8:CD007095 10.1002/14651858.CD007095.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kandelman D, Gagnon G. A 24-month clinical study of the incidence and progression of dental caries in relation to consumption of chewing gum containing xylitol in school preventive programs. J Dent Res 1990;69:1771–5. 10.1177/00220345900690111201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mickenautsch S, Leal SC, Yengopal V, et al. Sugar-free chewing gum and dental caries: a systematic review. J Appl Oral Sci 2007;15:83–8. 10.1590/S1678-77572007000200002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mäkinen KK, Järvinen KL, Anttila CH, et al. Topical xylitol administration by parents for the promotion of oral health in infants: a caries prevention experiment at a Finnish Public Health Centre. Int Dent J 2013;63:210–24. 10.1111/idj.12038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Azarpazhooh A, Limeback H, Lawrence HP, et al. Xylitol for preventing acute otitis media in children up to 12 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;11:CD007095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vernacchio L, Vezina RM, Mitchell AA. Tolerability of oral xylitol solution in young children: implications for otitis media prophylaxis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71:89–94. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Söderling E. Controversies around Xylitol. Eur J Dent 2009;3:81–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tähtinen PA, Laine MK, Ruuskanen O, et al. Delayed versus immediate antimicrobial treatment for acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:1227–32. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318266af2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Xylitol Use in Caries Prevention, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Danhauer JL, Johnson CE, Rotan SN, et al. National survey of pediatricians' opinions about and practices for acute otitis media and xylitol use. J Am Acad Audiol 2010;21:329–46. 10.3766/jaaa.21.5.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ly KA, Milgrom P, Rothen M. The potential of dental-protective chewing gum in oral health interventions. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139:553–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maguire A, Rugg-Gunn AJ. Xylitol and caries prevention-is it a magic bullet? Br Dent J 2003;194:429–36. 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stockmann C, Ampofo K, Hersh AL, et al. Seasonality of acute otitis media and the role of respiratory viral activity in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013;32:314–9. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827d104e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pichichero ME, Casey JR. Comparison of study designs for acute otitis media trials. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2008;72:737–50. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Spiro DM, King WD, Arnold DH, et al. A randomized clinical trial to assess the effects of tympanometry on the diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2004;114:177–81. 10.1542/peds.114.1.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Spurling GK, Del Mar CB DL, et al. Delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD004417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, et al. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two prescribing strategies for childhood acute otitis media. BMJ 2001;322:336–42. 10.1136/bmj.322.7282.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uhari M, Kontiokari T, Koskela M, et al. Xylitol chewing gum in prevention of acute otitis media: double blind randomised trial. BMJ 1996;313:1180–3. 10.1136/bmj.313.7066.1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lyon JL, Ashton A, Turner B, et al. Variation in the diagnosis of upper respiratory tract infections and otitis media in an urgent medical care practice. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:249–54. 10.1001/archfami.7.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pichichero ME. Acute otitis media: Part I. Improving diagnostic accuracy. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:2051–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Canadian Institute for Health Information. The cost of acute care hospital stays by medical condition in Canada: 2004-2005. Canada 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Saunders NR, Tennis O, Jacobson S, et al. Parents' responses to symptoms of respiratory tract infection in their children. CMAJ 2003;168:25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McWilliams CJ, Goldman RD. Update on acute otitis media in children younger than 2 years of age. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:1283–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Heikkinen T, Ruuskanen O. Signs and symptoms predicting acute otitis media. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:26–9. 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170130028006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Niemelä M, Uhari M, Möttönen M, et al. Costs arising from otitis media. Acta Paediatr 1999;88:553–6. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb00174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dales RE, Cakmak S, Brand K, et al. Respiratory illness in children attending daycare. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004;38:64–9. 10.1002/ppul.20034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Quach C, Moore D, Ducharme F, et al. Do pediatric emergency departments pose a risk of infection? BMC Pediatr 2011;11:2 10.1186/1471-2431-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vissing NH, Jensen SM, Bisgaard H. Validity of information on atopic disease and other illness in young children reported by parents in a prospective birth cohort study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:160 10.1186/1471-2288-12-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jacobs B, Young NL, Dick PT, et al. Canadian Acute Respiratory Illness and Flu Scale (CARIFS): development of a valid measure for childhood respiratory infections. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roberts CR, Warren JJ, Weber-Gasparoni K. Relationships between caregivers' responses to oral health screening questions and early childhood caries. J Public Health Dent 2009;69:290–3. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00126.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sealy PA, Farrell N, Hoogenboom A. Caregiver self-report of children’s use of the sippy cup among children 1 to 4 years of age. J Pediatr Nurs 2011;26:200–5. 10.1016/j.pedn.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, et al. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Soz Praventivmed 2001;46 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S3–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Toronto Public Health. Toronto Perinatal and Child Health Survey 2003, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hoch JS, Briggs AH, Willan AR. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue: a framework for the marriage of health econometrics and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ 2002;11:415–30. 10.1002/hec.678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hoch JS, Rockx MA, Krahn AD. Using the net benefit regression framework to construct cost-effectiveness acceptability curves: an example using data from a trial of external loop recorders versus Holter monitoring for ambulatory monitoring of "community acquired" syncope. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:68 10.1186/1472-6963-6-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hautalahti O, Renko M, Tapiainen T, et al. Failure of xylitol given three times a day for preventing acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26:423–7. 10.1097/01.inf.0000259956.21859.dd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Maguire JL, Birken CS, Loeb MB, et al. DO IT Trial: vitamin D Outcomes and Interventions in Toddlers - a TARGet Kids! randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:37 10.1186/1471-2431-14-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vernacchio L, Corwin MJ, Vezina RM, et al. Xylitol syrup for the prevention of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2014;133:289–95. 10.1542/peds.2013-2373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020941supp001.pdf (220.2KB, pdf)