Abstract

Objectives

Studies exploring work-related risk factors of common mental disorders (CMDs), such as major depressive disorder (MDD), generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) or alcohol abuse, have generally focused on a limited set of work characteristics. For the first time in a primary care setting, we examine simultaneously multiple work-related risk factors in relation to CMDs.

Method

We use data from a study of working individuals recruited among 2027 patients of 121 general practitioners (GPs) representative of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region in the North of France (April–August 2014). CMDs (MDD; GAD; alcohol abuse) were assessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Six worked-related factors were examined (work intensity, emotional demands, autonomy, social relations at work, conflict in values and job insecurity). Several covariates were considered (patient, GP and contextual characteristics). To study the association between workplace risk factors and CMDs, we used multilevel Poisson regression models adjusted for covariates.

Results

Among study participants, 389 (19.1%) met criteria for MDD, 522 (25.8%) for GAD and 196 (9.7%) for alcohol abuse. In multivariable analyses adjusted for covariates, MDD/GAD was significantly associated with work intensity (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.27) (absolute risk=52.8%), emotional demands (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.35) (absolute risk=54.9%) and social relations at work (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.87) (absolute risk=15.0%); alcohol abuse was associated with social relations at work (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.53) (absolute risk=7.6%) and autonomy (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.99) (absolute risk=8.9%).

Conclusions

Several workplace factors are associated with CMDs among working individuals seen by a GP. These findings confirm the role of organisational characteristics of work as a correlate of psychological difficulties above and beyond other sources of risk.

Keywords: primary care, psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cross-sectional study design.

Study of occupational factors in relation to common mental disorders among working adults in primary care evaluated with a standardised diagnostic tool in a large sample.

The inclusion of participants living in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region—one of the poorest in France—and the selective participation of general practitioners who took part in the study, may have led to an over-representation of patients with psychological disorders.

Introduction

Individuals who are part of the labour force are generally in better health than the unemployed,1 however, work can also have negative effects on somatic and psychosocial health.2 A study conducted among general practitioners (GPs) trained in occupational medicine found that mental health issues are frequently attributed to work.3 They are responsible for most of sickness absence and long-term work incapacity.4 In France, data from the national health insurance show that 20% of sickness absences are caused by mental disorders, and this proportion is even higher for long-term sickness absences (on average 111 days).5 The most frequent mental health difficulties among working individuals include mood, anxiety and substance use disorders (particularly alcohol-related problems), which can be grouped as ‘common mental disorders’ (CMDs).6 A systematic review of the literature in European countries shows that there is great diversity in the ascertainment of mental disorders and thus the prevalence estimates vary between countries. The authors suggest that the study of a larger range of diagnoses and the standardisation of methods can help the comparability across countries.7

The association between work and CMDs is bidirectional: work has been shown to be a risk factor of poor mental health,8 but the presence of a CMD can also influence job performance and well-being.9 10 Other risk factors of CMDs include individuals’ sociodemographic characteristics including being divorced or widowed, having a low educational level, older age, female gender,11–13 certain genetic factors14 and a history of chronic somatic or psychiatric disorders.15 Environmental factors (eg, social and material deprivation, etc) were described and show that low socioeconomic status was associated with higher rates of depression.11 12

Psychosocial factors related to the work environment are of particular interest because they may be more easily prevented than those which result from life events and are often unavoidable. Three main theoretical models have been proposed to explain relations between work characteristics and mental health. First, Karasek and Theorell16 argued that psychological demands, decision latitude and social support are especially important. Second, Siegrist17 proposed that what matters most is the subjectively ascertained effort–reward balance. A third model, developed by Elovainio et al, put an emphasis on the role of organisational justice including interpersonal comparison, that is, to say comparison of the response of the company in the same situation for different employees.18

Several studies evaluate the impact of work on mental health using these theoretical models.8 19 20 Overall, the risk of mental disorders is higher when individuals experience high job demands, low job control, high effort–reward imbalance or low organisational justice. As work organisation is evolving, other psychosocial factors described as ‘emergent’ have appeared in recent studies (eg, job insecurity, conflicts in values)21–24: Workers experiencing high job insecurity or role conflicts also seem to have a higher levels of CMDs.21 22 A recent systematic meta-review identified three overlapping categories of work-related risk factors that may contribute to the development of common mental health problems: imbalanced job design, occupational uncertainty and a lack of values and respect in the workplace.8 This review did not precisely describe different CMDs (major depressive disorder (MDD) was the most frequent outcome, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and alcohol abuse being less explored8 25 26). Additionally, most studies were based on self-reported questionnaires and not validated diagnostic interviews.

Work-related risk factors are also influenced by changes in society and work environments (globalisation, demographic change, job specialisation, communication load, new forms of work organisation, industry 4.0,27 etc). A French study assessed changes in psychosocial work factors between 2006 and 2011 and reported that some worsened (decision latitude, social support, reward, role conflict and work–life imbalance) over that period. These changes have been shown to vary with age, occupation, sector activity and type of contract.28

The objective of this study is to assess the association between GAD, MDD and alcohol abuse in a primary care setting, testing different psychosocial work-related risk factors. Combining emergent and classical factors is important in order to identify which are most strongly related to workers’ mental health, as outlined in the meta-review conducted by Harvey et al.8 Since GPs usually are the first contact point for employees in the healthcare process, the evaluation of primary care patients is of paramount importance.29 30 In primary care, the prevalence of CMDs is high, ranging from 3%22 to 25% for anxiety disorders,13 29–32 6%13 to 25% for depression11 29–32 and 2%30 to 11% for alcohol abuse.29 30 Two studies conducted in the UK show that one-third of patients seeing a GP for work-related reasons have a mental health issue.3 33 Yet GPs often have difficulties managing their patients’ work-related mental health problems, as they often lack negotiation strategies regarding sick leave, communication skills and cooperation with occupational physicians.34 GPs encounter a variety of workers with systematic, unsystematic or non-existing occupational health services at their workplace. A better understanding of work-related factors associated with individuals’ mental health is important to help GPs consider specific actions.

Methods

Design and study population

Héraclès is a cross-sectional exploratory study conducted between April and August 2014 among working individuals consulting a primary care physician in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region in the North of France.

Patient and public involvement

The number of subjects needed and the set-up of the study have previously been described.35 Briefly, with an estimated prevalence of 20%, to have a precision of 10%, we aimed to include 2000 patients via their GP. Participating GPs gave an oral consent to participate and were asked to randomly include a maximum of 24 patients who met the following criteria: being (1) actively employed and (2) aged 18–65 years, regardless of the reason of their medical appointment. GPs were asked to include the first two patients who met study inclusion criteria in each randomly selected time slot which had previously been defined with the GP. Approximately, one-fourth of the GPs in the region, selected to be representative of those practising in 15 areas of Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, were contacted to participate in the study. Participating GPs gave written information to their patients regarding the study and asked them to sign an informed consent.

This study was conducted by the Sentinelles network,36 part of the INSERM-Paris Sorbonne University research unit UMR-S 1136. This research group has a standing authorisation from the French independent administrative authority protecting privacy and personal data to conduct research among GPs and their patients (CNIL no 471 393).

Data collection

Participating GPs received a 15 min phone training regarding the study protocol and questionnaire. After their regular appointment, GPs interviewed participating patients for the purposes of the study. Study questionnaires included information on:

Measurement of CMDs

CMDs were measured using a standardised diagnostic interview: the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) that was used as a screening tool. The MINI is, a structured clinical interview that enables the diagnosis of mental disorders based on the Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.37 Specifically, three different diagnoses were ascertained: MDD (in the preceding 2 weeks), GAD (in the preceding 6 months) and alcohol abuse (in the preceding 12 months).

The sensibility of the MINI varied between 83% and 94% (MDD: 94%; GAD: 88%; Alcohol: 83%), the specificity between 72% and 97% (MDD: 79%; GAD: 72%; Alcohol: 97%) and the Kappa concordance coefficient between 0.36 and 0.82 (MDD: 0.73; GAD: 0.36; Alcohol: 0.82). The inter-rater and test–retest reliability measured by Kappa coefficient were good, respectively, 0.88–1 and 0.76–0.93.38

Work characteristics

Work characteristics were self-reported by the patient to their GP. We used a national French questionnaire proposed by experts in the field based on the international scientific literature and after auditioning Karasek and Siegrist.23 It combines (1) questions measuring psychological demands—work control—social support developed in Karasek’s model16 (two questions about decision latitude, four questions about psychological demands and two questions about social support); (2) questions measuring effort/reward balance based on Siegrist’s model17 (three questions about rewards and one question about overinvestment); (3) questions about organisational justice from Moorman’s questionnaire39; (4) questions from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire40 and from the General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychological and Social Factors at Work41 or from WOrking Conditions and Control Questionnaire.42 Overall, the questionnaire included 20 work-related items exploring 6 different areas (online supplementary appendix 1): (1) five related to work intensity and duration (contradictory orders, excessive amount of work, too much to think about at work, difficulties in balancing work and family life, time needed for work), (2) six concerning emotional demands (contacts with customers/beneficiaries, contact with people in distress, conflicts with customers/beneficiaries, the need to hide emotions, fear, exposure to aggressions), (3) two regarding autonomy (limited decision-making possibility, full use of skills), (4) three on the quality of social work relations (full recognition of the work performed, support from colleagues, support from superiors), (5) two concerning conflicts in values (possibility to perform quality work, doing disapproved things), (6) two about job insecurity (ability to work until retirement, fear of job loss). For four of these items (contacts with the public at work, contacts with people in distress, contradictory orders, ability to work until retirement) the response was either ‘yes’ or ‘no’, and for other factors the responses were ‘always’/‘often’/‘sometimes’/‘never’ numbered from 1 to 4. The reliability of questions pertaining to work characteristics was assessed by computing an omega coefficient.43 This coefficient varied between 0.35 and 0.79. The reliability was higher for social relations at work (ω=0.72), emotional demands (ω=0.75) and work intensity (ω=0.79) than for autonomy (ω=0.66), job insecurity (ω=0.50)or conflicts in values (ω=0.35).

bmjopen-2017-020770supp001.pdf (24.5KB, pdf)

Covariates

Patient’s characteristics

We considered already described previously risk factors of CMD11:

Past somatic problems.

Previous mental health problems/disorders.

Sociodemographic (age, gender, family status, family income, level of education).

Occupational grade44: blue-collar (farmer/manual worker), pink-collar (technician/associate professional/clerk/service worker) or white-collar (manager/professional).45

Company size.

Job instability assessed based on the type of contract (temporary vs permanent).

Healthcare characteristics46:

Reason for medical appointment (somatic, psychological, chronic disease management).

GP’s sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender).

Practice characteristics (size; comfort with psychological distress issues; opportunity to collaborate with mental health specialists).

Contextual characteristics (by the 15 proximity area of the region)

Contextual characteristics shown to be associated with CMDs in primary care11 12:

Density of psychiatrists, psychologists and GPs.

Social deprivation (loneliness, single parenthood, widowhood/divorce) and material deprivation (unemployment, income, level of not graduated).47 48

Geographical area: 15 proximity areas defined by the regional health agency of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region.

Statistical analyses

Some of the covariates were recoded to use fewer categories. For family status, participants living alone or living with parents were grouped into one category. For family income, participants were grouped in two categories: (€0–€3000) (which corresponds to approximately two times the minimum wage in France) and >€3000. For educational level, we created two categories: less than a high school degree (no degree, degree below high school) or a degree higher or equivalent to a high school degree. For age, our continuous variable was studied in three categories based on the distribution 18–35, 36–50, 51–65.

Associations between sociodemographic characteristics and GAD, MDD and alcohol abuse were studied using the χ2 test. Covariates associated with the outcomes with p<0.2 were included in the multivariate analysis.

Work-related factors were regrouped according to six previously suggested dimensions transformed each into a Z-score to be comparable to each other.23 A correlation matrix of different work characteristics was computed and presented in a supplementary file (online supplementary appendix 2). Each dimension was dichotomised based on the third quartile or studied as continuous variable in the multivariable models. At first, statistical analyses were conducted separately for each outcome, but factors associated with MDD and GAD were very similar, therefore, to gain statistical power we merged these two disorders into one outcome. To study the association between occupational factors and GAD/MDD and alcohol, we used multilevel Poisson regression models using a robust error variance procedure (sandwich estimation)49 with patient as level 1 and geographical area as level 2. Given the high prevalence of these problems, Poisson regression was preferred to logistic regression to avoid the overestimation of risk ratios.50 GAD/MDD or alcohol abuse were the dependent variables and the six dimensions of work-related factors were the exposure variables. Statistical models were adjusted for each exposure variable and for other covariates that were associated with GAD/MDD (previous mental health problems/disorders, alcohol abuse, material deprivation and GP’s gender) or alcohol abuse (family status, company size, previous mental health problems/disorders, job instability, education level, past unemployment, GAD and MDD) (p<0.05) in a multivariable Poisson regression model excluding occupational factors. Age, gender and occupational grade were included directly in the adjustment variable. Absolute risks among persons who were exposed were computed for each of the studied work dimensions.

bmjopen-2017-020770supp002.pdf (47.5KB, pdf)

All analyses were performed using GNU R software V.3.1.1. (lme4 package).51 52

Results

Participation and description of the population

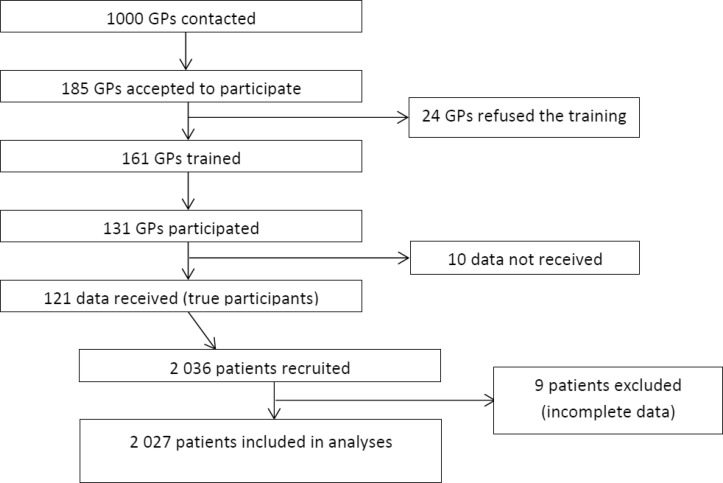

Of the 1000 GPs contacted by mail, 185 accepted to participate (response rate=18.5%) and 121 completed the study (figure 1). Participating GPs were more likely to be male (sex ratio=1.82), and to be 50 years or older; they were disseminated throughout the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region (table 1). Participating GPs were representative of those practising in the region in terms of geography, age, type and years of practice.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participation in the Héraclès study, France, 2014. GPs, general practitioners.

Table 1.

Description of the study population, Héraclès study, France, 2014

| N | % | |

| Work characteristics | ||

| Work intensity | ||

| High | 437 | 21.6 |

| Low | 1588 | 78.3 |

| Emotional demands | ||

| High | 476 | 23.5 |

| Low | 1549 | 76.4 |

| Autonomy | ||

| High | 598 | 29.5 |

| Low | 1427 | 70.4 |

| Conflict in values | ||

| High | 685 | 33.8 |

| Low | 1340 | 66.1 |

| Social relations at work | ||

| High | 688 | 33.9 |

| Low | 1337 | 66 |

| Job insecurity | ||

| High | 565 | 27.9 |

| Low | 1460 | 72 |

| Covariates | ||

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 46.4 | |

| Female | 53.6 | |

| Age group | ||

| (18–35) | 597 | 29.5 |

| (36–50) | 872 | 43.1 |

| (51–65) | 552 | 27.3 |

| Occupational grade | ||

| Blue collar | 273 | 13.9 |

| Pink collar | 1185 | 60.1 |

| White collar | 513 | 26 |

| Educational level | ||

| <High school degree | 780 | 38.7 |

| ≥High school degree | 1238 | 61.3 |

| Family status | ||

| Lives alone | 481 | 23.8 |

| Lives with a partner or parents | 1543 | 76.2 |

| Household income (in €) | ||

| (0–3000) | 491 | 30.6 |

| 3000+ | 1112 | 69.4 |

| Company size | ||

| 1–10 | 361 | 18.4 |

| 11–50 | 490 | 25 |

| 51–250 | 420 | 21.5 |

| 250+ | 687 | 35.1 |

| Previous mental health problems /disorders | ||

| Yes | 189 | 9.8 |

| No | 1735 | 90.2 |

| Past somatic problems | ||

| Yes | 559 | 28.9 |

| No | 1373 | 71.1 |

| Purpose of consultation with GP | ||

| Somatic | ||

| Yes | 1331 | 65.7 |

| No | 696 | 34.3 |

| Psychological | ||

| Yes | 425 | 21 |

| No | 1602 | 79 |

| Chronic disease management | ||

| Yes | 313 | 15.4 |

| No | 1714 | 84.6 |

| Past unemployment | ||

| Yes | 613 | 30.2 |

| No | 1414 | 69.8 |

| Job instability | ||

| Yes | 522 | 33 |

| No | 1061 | 67 |

| GPs characteristics | ||

| GP’s gender | ||

| Male | 1364 | 67.3 |

| Female | 663 | 32.7 |

| GP’s age | ||

| (18–39) | 194 | 9.6 |

| (40–49) | 626 | 30.9 |

| (50–59) | 832 | 41 |

| 60+ | 375 | 18.5 |

| Size of practice population | ||

| 0–500 | 211 | 11.2 |

| 5000–1000 | 993 | 52.5 |

| 1000–1500 | 433 | 22.9 |

| 1500+ | 253 | 13.4 |

| Comfort with mental health problems | ||

| High | 1600 | 82.6 |

| Low | 338 | 17.4 |

| High opportunity to work with mental health specialists | ||

| High | 1036 | 52.4 |

| Low | 941 | 47.6 |

| Contextual characteristics | ||

| Social deprivation | ||

| High | 552 | 27.2 |

| Low | 1475 | 72.8 |

| Material deprivation | ||

| High | 850 | 41.9 |

| Low | 1177 | 58.1 |

| Density of psychiatrist | ||

| High | 1569 | 77.4 |

| Low | 458 | 22.6 |

| Density of psychologist | ||

| High | 1554 | 76.7 |

| Low | 473 | 23.3 |

| Density of GP | ||

| High | 1525 | 75.2 |

| Low | 502 | 24.8 |

| Geographical area | ||

| Métropole Flandre Intérieure | 1035 | 51.1 |

| Hainault-Cambrésis | 333 | 16.4 |

| Artois-Douaisis | 337 | 16.6 |

| Littoral | 322 | 15.9 |

GPs, general practitioners.

Participating GPs recruited 2027 patients among which 389 (19.1%) had MDD, 522 (25.8%) GAD and 196 (9.7%) alcohol abuse. Participating patients were mostly female (53.6%), aged 42.3 years (SD 10.6) on average, mainly living with a partner (76.2%), working in pink-collar occupations (60.1%). 61.3% had graduated from high school and 30.2% had been unemployed in the past. Among study participants, 21.0% came to see their GP for psychological reasons (table 1). Characteristics of participants with MDD, GAD or alcohol abuse are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Association between CMD, MDD, GAD and alcohol abuse and covariates, Héraclès study, France, 2014 (χ2 test)

| MDD and GAD (n=648) | Alcohol (n=196) | |||

| N (%) | P values (χ2-df) | N (%) | P values (χ2-df) | |

| Work characteristics | ||||

| Work intensity | <0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| High | 232 (52.8) | (111.1–1) | 58 (13.3) | (7.5–1) |

| Low | 416 (26.2) | 138 (8.7) | ||

| Emotional demands | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| High | 262 (54.9) | (149.8–1) | 73 (15.3) | (21.8–1) |

| Low | 386 (24.9) | 123 (7.9) | ||

| Autonomy | <0.01 | 0.48 | ||

| High | 158 (26.4) | (11.6–1) | 53 (8.9) | (0.6–1) |

| Low | 490 (34.3) | 143 (10.0) | ||

| Conflict in values | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| High | 335 (48.8) | (134.4–1) | 90 (13.1) | (13.5–1) |

| Low | 313 (23.3) | 106 (7.9) | ||

| Social relations at work | <0.01 | 0,03 | ||

| High | 103 (15.0) | (137.2–1) | 52 (7.6) | (4.9–1) |

| Low | 545 (40.7) | 144 (10.8) | ||

| Job insecurity | <0.01 | 014 | ||

| High | 242 (42.8) | (41.8–1) | 64 (11.3) | (2.2–1) |

| Low | 406 (27.8) | 132 (9.0) | ||

| Covariates | ||||

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age group | 0.03 | 0,24 | ||

| (18–35) | 172 (28.8) | (7.1–2) | 48 (8.0) | (2.8–2) |

| (36–50) | 306 (35.1) | 87 (10.0) | ||

| (51–65) | 169 (30.6) | 60 (10.9) | ||

| Gender | <0.01 | <0,01 | ||

| Male | 266 (28.3) | (10.5–1) | 140 (14.9) | (53.7–1) |

| Female | 382 (35.2) | 56 (5.2) | ||

| Occupational grade | 0.32 | <0.01 | ||

| Blue collar | 79 (28.9) | (2.3–2) | 53 (19.4) | (37.8–2) |

| Pink collar | 386 (32.6) | 86 (7.3) | ||

| White collar | 152 (29.6) | 50 (9.7) | ||

| Educational level | 0.13 | <0.01 | ||

| <High school degree | 266 (34.1) | (2.3–1) | 98 (12.6) | (11.7–1) |

| ≥High school degree | 381 (30.8) | 97 (7.8) | ||

| Family status | 0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Lives alone | 471 (30.5) | (6.3–1) | 63 (13.1) | (7.9–1) |

| Lives with a partner or parents | 177 (36.8) | 133 (8.6) | ||

| Household income (in €) | 0.03 | 0.3 | ||

| (0–3000) | 184 (37.5) | (4.8–1) | 53 (10.8) | (1.1–1) |

| 3000+ | 353 (31.7) | 100 (9.0) | ||

| Company size | 0.03 | <0.01 | ||

| 1–5 | 108 (29.9) | (9.1–3) | 51 (14.1) | (16.5–3) |

| 6–25 | 183 (37.3) | 53 (10.8) | ||

| 26–250 | 138 (32.9) | 43 (10.2) | ||

| 250+ | 203 (29.5) | 45 (6.6) | ||

| Previous mental health problems/disorders | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 108 (57.1) | (57.1–1) | 30 (15.9) | (16.5–1) |

| No | 516 (29.8) | 150 (8.6) | ||

| Past somatic problems | 0.82 | 0.84 | ||

| Yes | 185 (33.1) | (0.05–1) | 53 (9.5) | (0.04–1) |

| No | 445 (32.4) | 136 (9.9) | ||

| Purpose of consultation with GP | ||||

| Somatic | <0.01 | 0.04 | ||

| Yes | 335 (25.2) | (81.5–1) | 115 (8.6) | (4.4–1) |

| No | 313 (45) | 81 (11,6) | ||

| Psychological | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 312 (73.4) | (422.3–1) | 61 (14.4) | (12.8–1) |

| No | 336 (21) | 135 (8.4) | ||

| Chronic disease management | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 75 (24) | (10.5–1) | 46 (14.7) | (10.0–1) |

| No | 573 (33.4) | 150 (8.8) | ||

| Past unemployment | 0.57 | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 202 (33) | (0.33–1) | 80 (13,1) | (11.0–1) |

| No | 446 (31.5) | 116 (8.2) | ||

| Job instability | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 229 (43.9) | (47.0–1) | 70 (13.4) | (12.0–1) |

| No | 400 (27.5) | 118 (11.1) | ||

| GPs characteristics | ||||

| GP’s gender | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Male | 375 (27.5) | (37.8–1) | 152 (11.1) | (9.9–1) |

| Female | 273 (41.2) | 44 (6.6) | ||

| GP’s age | 0.13 | 0.14 | ||

| (18–39) | 72 (37.1) | (5.7–3) | 18 (9.3) | (5.5–3) |

| (40–49) | 190 (30.4) | 49 (7.8) | ||

| (50–59) | 254 (30.5) | 95 (11.4) | ||

| 60+ | 132 (35.2) | 34 (9.1) | ||

| Size of practice population | <0.01 | 0.06 | ||

| 0–500 | 79 (37.4) | (14.7–3) | 18 (8.5) | (7.4–3) |

| 5000–1000 | 295 (29.7) | 82 (8.3) | ||

| 1000–1500 | 136 (31.4) | 47 (10,9) | ||

| 1500+ | 104 (41.1) | 34 (13.4) | ||

| Comfort with mental health problems | 0.21 | 0.48 | ||

| High | 500 (31.3) | (1.6–1) | 155 (9.7) | (0.5–1) |

| Low | 118 (34.9) | 28 (8.3) | ||

| High opportunity to work with mental health specialists | <0,01 | 0.05 | ||

| High | 345 (36.7) | (18.2–1) | 103 (9.9) | (3.7–1) |

| Low | 286 (27.6) | 86 (9.1) | ||

| Contextual characteristics | ||||

| Social deprivation | 0.32 | 0.87 | ||

| High | 167 (30.2) | (1.0–1) | 52 (9.4) | (0.03–1) |

| Low | 481 (32.6) | 144 (9.8) | ||

| Material deprivation | <0.01 | 0,74 | ||

| High | 306 (36) | (10.4–1) | 85 (10) | (0.1–1) |

| Low | 342 (29.1) | 111 (9.4) | ||

| Density of psychiatrist | 0.02 | 0.97 | ||

| High | 522 (33.3) | (5.1–1) | 45 (9.8) | (0.01–1) |

| Low | 126 (27.5) | 151 (9.6) | ||

| Density of psychologist | 0.05 | 0.10 | ||

| High | 515 (33.1) | (4.0–1) | 36 (7.6) | (2.7–1) |

| Low | 133 (28.1) | 160 (10.3) | ||

| Density of GP | 0.06 | 0.88 | ||

| High | 505 (33.1) | (3.6–1) | 50 (10) | (0.02–1) |

| Low | 143 (28.4) | 146 (9.6) | ||

CMD, common mental disorder; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; GPS, general practitioners; MDD, major depressive disorder.

The study response rate was 80%: 41 GPs filled a non-respondent form for 495 patients who refused to participate. Non-respondents did not differ from participants in term of age (p=0.47) and gender (p=0.23). Compared with working age patients consulting a GP in the study region, study participants were older (p<0.01) but had a similar gender distribution (p=0.08).

MDD, GAD and alcohol abuse related work factors

Bivariate analysis

In bivariate analyses, female gender was significantly associated with GAD/MDD and male gender with alcohol abuse. Family status, company size, previous mental health problems/disorders, consultation for psychiatric, somatic or chronic diseases and job insecurity were also significantly associated with the two outcomes. Occupational grade, education level and past unemployment were significantly associated (p<0.01) only with alcohol abuse, with elevated rates in blue-collar workers, patients who experienced unemployment and individuals with an education level lower than a high school degree. Age and household income were only associated with MDD/GAD.

Regarding GP characteristics, GP gender and opportunity to work with mental health specialist was associated with the two outcomes. Size of practice population was associated only with MDD/GAD.

Most of the contextual variables studied were not associated with our study outcomes, except for material deprivation and the density of psychiatrists and psychologists which were significantly associated with MDD/GAD. To the contrary, work characteristics were almost all significantly associated with the two study outcomes, except job insecurity and autonomy which were not associated with alcohol abuse (table 2).

Multivariable analysis

All occupational factors were associated with our two study outcomes in unadjusted analyses. In adjusted analyses, patients reporting high levels of work intensity (RR=1.16, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.27; p<0.01) (absolute risk=52.8%) and emotional demands (RR=1.24, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.35; p<0.01) (absolute risk=54.9%) had a higher risk of MDD/GAD, whereas patients with high social relations at work had a lower risk to have MDD/GAD (RR=0.78, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.87; p<0.01) (absolute risk=15.0%).

Regarding alcohol abuse, social relations at work were associated with a higher risk (RR=1.25, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.53; p=0.03) (absolute risk=7.6%) and higher autonomy was protective (RR=0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.99; p=0.05) (absolute risk=8.9%) (table 3). A sensitivity analyses by occupational group showed a higher risk of alcohol abuse for white-collar workers in case of high social relations at work (RR=1.89, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.9).

Table 3.

Work-related factors and MDD, GAD and alcohol abuse, Héraclès study, France, 2014

| MDD/GAD (n=1782) | Alcohol (n=1776) | |||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||

| RR* | 95% CI | P values | RR† | 95% CI | P values | RR* | 95% CI | P values | RR‡ | 95% CI | P values | |

| Work intensity | 1.46 | (1.35 to 1.57) | <0.01 | 1.16 | (1.06 to 1.27) | <0.01 | 1.31 | (1.14 to 1.50) | <0.01 | 1.16 | (0.97 to 1.38) | 0.10 |

| Emotional demands | 1.53 | (1.43 to 1.64) | <0.01 | 1.24 | (1.13 to 1.35) | <0.01 | 1.40 | (1.23 to 1.59) | <0.01 | 1.16 | (0.97 to 1.38) | 0.10 |

| Autonomy | 0.68 | (0.63 to 0.73) | <0.01 | 0.94 | (0.85 to 1.04) | 0.26 | 0.72 | (0.63 to 0.83) | <0.01 | 0.82 | (0.67 to 0.99) | 0.05 |

| Conflict in values | 1.45 | (1.35 to 1.56) | <0.01 | 1.06 | (0.96 to 1.17) | 0.26 | 1.30 | (1.14 to 1.49) | <0.01 | 1.16 | (0.96 to 1.40) | 0.13 |

| Social relations at work | 0.61 | (0.56 to 0.66) | <0.01 | 0.78 | (0.70 to 0.87) | <0.01 | 0.83 | (0.72 to 0.96) | 0.01 | 1.25 | (1.01 to 1.53) | 0.03 |

| Job insecurity | 1.13 | (1.05 to 1.22) | <0.01 | 1.03 | (0.95 to 1.11) | 0.49 | 1.14 | (1.00 to 1.30) | 0.05 | 0.95 | (0.82 to 1.11) | 0.52 |

For MDD/GAD model explained variance was 0.21 and 0.11 for alcohol model.

Multilevel Poisson regression models.

*No adjustment: each occupational factor is studied one at the time.

†Adjusted on: each occupational factors, age, gender, occupational grade, previous mental health problems/disorders, alcohol abuse, material deprivation and GP’s gender.

‡Adjusted on: each occupational factors, age, gender, occupational grade, family status, company size, previous mental health problems/disorders, job instability, education level, past unemployment, GAD and MDD.

GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; GP, general practitioner; MDD, major depressive disorder; RR, relative risk.

Bold values correspond to significant results.

Associations between covariates and the study outcomes are presented in supplementary material (online supplementary appendix 3).

bmjopen-2017-020770supp003.pdf (86.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

Main results

In our study conducted among a large sample of persons consulting a GP, we found that several work characteristics are associated with mental health. Unfavourable social relations at work are associated with a higher risk of MDD/GAD, but a lower risk of alcohol abuse. High work intensity and high emotional demands at work are associated with a higher risk of MDD/GAD. Finally, low autonomy at work is associated with a higher risk of alcohol abuse.

Comparison with literature

We confirm, for the first time in primary care, the association between CMDs and social relations at work which was reported in other studies. A cross-sectional study conducted in Japan (using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale to assess depression) reported a higher risk of depressive symptoms among workers who receive low social support at work (OR=3.8).53 A meta-analysis of 17 studies investigating depressive disorders54 found that low social support at work is also associated with anxiety disorders, as had already been observed in a study conducted by Wang et al.55 However, the causal direction of this association cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional design of our study. It is possible that low social relations at work increases the risk of depression or anxiety, as has been shown in different longitudinal studies.56 Moreover, social relations and support (outside or at work) affect psychological health,57 but it is also possible that individuals who are not depressed or experiencing anxiety disorders receive better social support.57 Finally, the association between GAD/MDD and social relations at work could also be related to negative visions of social relations among persons who are depressed or anxious.58 For alcohol abuse, an inverse association with social relations was observed: higher risk associated with high social relations at work, which is consistent with results of a cross-sectional study conducted among Canadian workers.25 It raises the possibility of festive alcohol consumption with colleagues in or outside work.59 We performed sensitivity analyses by occupational group to explore this result and found that white-collar workers were most likely to report alcohol abuse in case of high social relations at work (RR=1.89, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.9). Other studies have approached this issue by pointing out afterwork with colleagues.60

Work intensity or high work time and intensity is associated with depressive symptoms in the meta-analysis conducted by Theorell et al (10 studies).54 The meta-analysis of longitudinal studies by Netterstrøm et al highlights the adverse effects of high psychological demands on the occurrence of depressive disorders.56 However, this association could also be due to distorted views of psychological demands among persons with depressive disorders.58

High emotional demands at work have previously been shown to predict depressive disorders among women in a population-based nested case–control study of 14 166 psychiatric patients conducted in Denmark (Incidence rate ratio=1.39)26 or for GAD in a French prospective study (using the same diagnostic tool MINI) (RR=1.66 among workers with high emotional demand22). In our cross sectional study, the causal attribution is not possible, thus, it is also possible that people with depression and/or anxiety have a different view towards those demands.58

Work autonomy appears related to alcohol abuse, as reported in an English prospective study: low decision latitude, which is a part of the autonomy axis in our study, is associated to higher risk of alcohol dependence within women.61

We did not confirm the association found earlier between CMD and high job insecurity or conflict in value.21 22 24

Overall, our study shows that work intensity and emotional demands are associated with GAD/MDD and social relations at work have a positive effect. For alcohol abuse, autonomy and social relations at work are negative risk factors.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, our study was conducted in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, that is, one of the poorest in France with a total of four millions inhabitants. During the first half of the 20th century, this region was highly industrialised and since the 1950s it has suffered from industrial decline as mines, as well as the textile and steel industries gradually closed. Despite the growth of services and some specialised industries (car, rail and glass), levels of education, unemployment (15%), poverty and health indicators (eg, life expectancy) are unfavourable. The Nord-Pas-de-Calais region has a low density of GPs (−11% than in France overall) and other medical specialties (−24%).62 Moreover, the study was conducted after the 2008 recession, which has been associated with an increase in the prevalence of common mental health disorders worldwide.63 64 This could lead to a high level of mental disorders. The prevalence of MDD, GAD and alcohol abuse among patients consulting a GP is, respectively, 19.1%, 25.8% and 9.7%. This is consistent with studies in primary care where the prevalence of CMDs ranges from 6% to 25% for depression, 3% to 25% for anxiety and 2% to 11% for alcohol abuse.11 13 29–32 Results should be replicated in others areas. Second, a possible weakness is GPs’ selective participation. GPs who participated in the study could be especially interested in CMDs. This interest may be related to the personal interest of the GP, but it could also be related to the GP’s patients’ rate of CMDs. Therefore, it may cause a larger selection of patients with psychological disorders. However, the study response rate is similar to previous studies among GPs30 65 and physicians who participated were representative of the region, thereby limiting possible bias. In general practice, GPs’ response rate is generally low,66 and in order to favour an optimal response rate, we tested the questionnaire to make it parsimonious, GPs were paid for their participation, and GPs who were asked to participate were individually called. A random procedure to select patients included in the study limited bias. Indeed, GPs were asked to include patients following an inclusion schedule that was provided at the start of the study. This allowed us to include patients in different time slots of the week. Moreover a non-respondent form had to be filled by participating GPs, but we suppose that the filling rate was low because only 41 GPs filled this form and declare that 495 patient were not included. Characteristics of patients included and those not included did not differ in term of age and gender. However, it is important to note that compared with studies in work environment settings, it is possible that patients included in this primary care setting have a different level of health than other employees who do not consult their GP. The measurement of psychosocial work factors in our study was based on an unpublished expert report based on the international literature, and measurement of reliability in our sample was rather low for some axis (ω=0.35 for conflict in values, 0.50 for job insecurity and 0.66 for autonomy). These dimensions are only composed of two items, this can explain partly the rather low reliability. However, the use of a validated questionnaire could have allowed for a better comparison with the existing literature and better psychometric quality.

We were able to take into account many covariates (characterising individuals, GPs and patients’ context), but some relevant variables were not included, such as participants’ prior history of mental health problems, social support outside of work or life events.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study are of interest because it identifies occupational factors related to CMD (MDD/GAD and alcohol abuse) among working adults in primary care with a standardised diagnostic tool (MINI) in a large sample (n=2027).37 The primary care sample used allows the inclusion of a panel of workers in the labour force including independent workers, workers in small companies or workers who do not have an occupational physician which is not the case in most of studies in occupational setting. Indeed, an international study including 49 countries shows that the average occupational health services coverage of workers was 24.8% with a larger gap among workers in small-scale enterprises, the self-employed, agriculture and the informal sector.67 Moreover, the present study confirms the increased risk of anxiety and depression associated with work intensity, social relations at work and emotional demands as well as the association between reduced autonomy and alcohol abuse in a primary care setting. Furthermore, we could demonstrate a negative association between social relations at work and alcohol abuse.8 22 26 61

Conclusion

Our study is one of the first to investigate simultaneously well-known occupational risk factors such as job strain and effort–reward imbalance and new occupational factors described in recent literature. Our results emphasise the importance of social relations at work and different occupational factors that are associated with MDD, GAD and alcohol abuse. These results could be a starting point for the GPs to apprehend these factors with their patients and to communicate with occupational physicians in order to prevent the onset of CMD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participating GPs of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region and their patients who participated to the Héraclès study. The authors thank the department of general practice of Lille’s University and the regional union of health professional of GP’s (URPS-ML) of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region for their involvement in the GP recruitment phase. The authors also want to thank the Héraclès study scientific committee members who contributed to the brainstorming and the set-up of this survey.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design: MR, NY, MM, AL TB and LP. Data analysis and collection: MR, LFC, MM and LP. Drafting of the manuscript: MR. Critical revision of the manuscript: NY, MM and AL. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Nord-Pas-de-Calais regional health agency (ARS) and the Ile-de-France region—DIM Gestes (Mathieu Rivière’s PhD thesis).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Wagenaar AF, Kompier MA, Houtman IL, et al. Employment contracts and health selection: unhealthy employees out and healthy employees in? J Occup Environ Med 2012;54:1192–200. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182717633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McLellan RK, Work MRK. Work, Health, And Worker Well-Being: Roles And Opportunities For Employers. Health Aff 2017;36:206–13. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hussey L, Turner S, Thorley K, et al. Work-related ill health in general practice, as reported to a UK-wide surveillance scheme. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:637–40. 10.3399/bjgp08X330753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;382:1575–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. NHI. Description des populations du regime general en arret de travail de 2 a 4 mois. 2004. http://fulltext.bdsp.ehesp.fr/Cnamts/Etudes/2004/DESCRIPTION_ARRETS_TRAVAIL_2_4_MOIS_2004.pdf.

- 6. Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:476–93. 10.1093/ije/dyu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;21:655–79. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, et al. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:301–10. 10.1136/oemed-2016-104015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reme SE, Grasdal AL, Løvvik C, et al. Work-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy and individual job support to increase work participation in common mental disorders: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Occup Environ Med 2015;72:745–52. 10.1136/oemed-2014-102700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 2003;289:3135–44. 10.1001/jama.289.23.3135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Milanović SM, Erjavec K, Poljičanin T, et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms and associated socio-demographic factors in primary health care patients. Psychiatr Danub 2015;27:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freeman A, Tyrovolas S, Koyanagi A, et al. The role of socio-economic status in depression: results from the COURAGE (aging survey in Europe). BMC Public Health 2016;16:1098 10.1186/s12889-016-3638-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ibanez G, Son S, Chastang J, et al. Mental Health Disorders in General Practice in France: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Transl Biomed 2016;07:4 10.21767/2172-0479.100096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lacerda-Pinheiro SF, Pinheiro Junior RF, Pereira de Lima MA, et al. Are there depression and anxiety genetic markers and mutations? A systematic review. J Affect Disord 2014;168:387–98. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abbas RA, Hammam RA, El-Gohary SS, et al. Screening for common mental disorders and substance abuse among temporary hired cleaners in Egyptian Governmental Hospitals, Zagazig City, Sharqia Governorate. Int J Occup Environ Med 2013;4:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karasek RA. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:285–309. 10.2307/2392498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol 1996;1:27–41. 10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elovainio M, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J. Organizational justice: evidence of a new psychosocial predictor of health. Am J Public Health 2002;92:105–8. 10.2105/AJPH.92.1.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rugulies R, Aust B, Madsen IE. Effort-reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 2017;43:294–306. 10.5271/sjweh.3632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health--a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:443–62. 10.5271/sjweh.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murcia M, Chastang JF, Niedhammer I. Psychosocial work factors, major depressive and generalised anxiety disorders: results from the French national SIP study. J Affect Disord 2013;146:319–27. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niedhammer I, Malard L, Chastang JF. Occupational factors and subsequent major depressive and generalized anxiety disorders in the prospective French national SIP study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:200 10.1186/s12889-015-1559-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gollac M. Mesurer les facteurs psychosociaux de risque au travail pour les maîtriser. 2010. http://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_SRPST_definitif_rectifie_11_05_10.pdf.

- 24. Schütte S, Chastang JF, Parent-Thirion A, et al. Psychosocial work exposures among European employees: explanations for occupational inequalities in mental health. J Public Health 2015;37:373–88. 10.1093/pubmed/fdv044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marchand A, Parent-Lamarche A, Blanc MÈ. Work and high-risk alcohol consumption in the Canadian workforce. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:2692–705. 10.3390/ijerph8072692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wieclaw J, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, et al. Psychosocial working conditions and the risk of depression and anxiety disorders in the Danish workforce. BMC Public Health 2008;8:280 10.1186/1471-2458-8-280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gentner S. Industry 4.0: Reality, Future or just Science Fiction? How to Convince Today’s Management to Invest in Tomorrow’s Future! Successful Strategies for Industry 4.0 and Manufacturing IT. Chimia 2016;70:628–33. 10.2533/chimia.2016.628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malard L, Chastang JF, Niedhammer I. Changes in psychosocial work factors in the French working population between 2006 and 2010. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015;88:235–46. 10.1007/s00420-014-0953-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ansseau M, Dierick M, Buntinkx F, et al. High prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord 2004;78 49–55. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00219-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Toft T, Fink P, Oernboel E, et al. Mental disorders in primary care: prevalence and co-morbidity among disorders. results from the functional illness in primary care (FIP) study. Psychol Med 2005;35:1175–84. 10.1017/S0033291705004459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alkhadhari S, Alsabbrri AO, Mohammad IH, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in the primary health clinic attendees in Kuwait. J Affect Disord 2016;195:15–20. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Norton J, de Roquefeuil G, David M, et al. [Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in French general practice using the patient health questionnaire: comparison with GP case-recognition and psychotropic medication prescription]. Encephale 2009;35 560–9. 10.1016/j.encep.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beckley A, Lees B, Collington S, et al. Work-related health advice in primary care. Occup Med 2011. 61:498–502. 10.1093/occmed/kqr119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Kock CA, Lucassen PL, Spinnewijn L, et al. How do Dutch GPs address work-related problems? A focus group study. Eur J Gen Pract 2016;22:169–75. 10.1080/13814788.2016.1177507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rivière M, Plancke L, Leroyer A, et al. Prevalence of work-related common psychiatric disorders in primary care: The French Héraclès study. Psychiatry Res 2018;259 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Flahault A, Blanchon T, Dorléans Y, et al. Virtual surveillance of communicable diseases: a 20-year experience in France. Stat Methods Med Res 2006;15:413–21. 10.1177/0962280206071639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry 1997;12:224–31. 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moorman RH. Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? J Appl Psychol 1991;76:845–55. 10.1037/0021-9010.76.6.845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kristensen TS, Hannerz H, Høgh A, et al. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire--a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand J Work Environ Health 2005;31:438–49. 10.5271/sjweh.948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dallner M, Elo A-L, Gamberale F, et al. NCo M, Validation of the general Nordic questionnaire (QPSNordic) for psychological and social factors at work (No. Nord 2000:12): Copenhagen, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hansez I. The “Working conditions and control questionnaire” (WOCCQ): Towards a structural model of subjective stress. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée/European Review of Applied Psychology 2008;58:253–62. 10.1016/j.erap.2008.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol 2014;105:399–412. 10.1111/bjop.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. INSEE. Nomenclature des Professions et Catégories Socioprofessionnelles - PCS. 2003. https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/2400059.

- 45. Min KB, Park SG, Hwang SH, et al. Precarious employment and the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Prev Med 2015;71:72–6. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fleury MJ, Bamvita JM, Farand L, et al. Variables associated with general practitioners taking on patients with common mental disorders. Ment Health Fam Med 2008;5:149–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pampalon R, Hamel D, Gamache P, et al. Validation of a deprivation index for public health: a complex exercise illustrated by the Quebec index. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2014;34:12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moreno-Betancur M, Latouche A, Menvielle G, et al. Relative index of inequality and slope index of inequality: a structured regression framework for estimation. Epidemiology 2015;26:518–27. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Knol MJ, Le Cessie S, Algra A, et al. Overestimation of risk ratios by odds ratios in trials and cohort studies: alternatives to logistic regression. CMAJ 2012;184:895–9. 10.1503/cmaj.101715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna. Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2008. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4 . J Stat Softw 2015;67 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Honda A, Date Y, Abe Y, et al. Work-related Stress, Caregiver Role, and Depressive Symptoms among Japanese Workers. Saf Health Work 2014;5:7–12. 10.1016/j.shaw.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015;15:738 10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang JL, Lesage A, Schmitz N, et al. The relationship between work stress and mental disorders in men and women: findings from a population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:42–7. 10.1136/jech.2006.050591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Netterstrøm B, Conrad N, Bech P, et al. The relation between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol Rev 2008;30:118–32. 10.1093/epirev/mxn004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Melchior M, Berkman LF, Niedhammer I, et al. Social relations and self-reported health: a prospective analysis of the French Gazel cohort. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1817–30. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00181-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Beck Self-Esteem Scales. Behav Res Ther 2001;39:115–24. 10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00028-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nordaune K, Skarpaas LS, Sagvaag H, et al. Who initiates and organises situations for work-related alcohol use? The WIRUS culture study. Scand J Public Health 2017;45:749–56. 10.1177/1403494817704109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hagihara A, Tarumi K, Nobutomo K, stressors W. Work stressors, drinking with colleagues after work, and job satisfaction among white-collar workers in Japan. Subst Use Misuse 2000;35:737–56. 10.3109/10826080009148419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Head J, Stansfeld SA, Siegrist J. The psychosocial work environment and alcohol dependence: a prospective study. Occup Environ Med 2004;61:219–24. 10.1136/oem.2002.005256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Plancke L, Bavdek R. Les disparités régionales en santé mentale et en psychiatrie. La situation du Nord Pas-de-Calais en France métropolitaine. Lille: F2RSM, 2013. http://www.santementale5962.com/ressources-et-outils/les-editions-de-la-f2rsm/article/disparites-regionales-en-sante. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Katikireddi SV, Niedzwiedz CL, Popham F. Trends in population mental health before and after the 2008 recession: a repeat cross-sectional analysis of the 1991-2010 Health Surveys of England. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001790 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lee S, Guo WJ, Tsang A, et al. Evidence for the 2008 economic crisis exacerbating depression in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord 2010;126:125–33. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Goldenberg MG, Skeldon SC, Nayan M, et al. Prostate-specific antigen testing for prostate cancer screening: A national survey of Canadian primary care physicians' opinions and practices. Can Urol Assoc J 2017;11 10.5489/cuaj.4486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cottrell E, Roddy E, Rathod T, et al. Maximising response from GPs to questionnaire surveys: do length or incentives make a difference? BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:3 10.1186/1471-2288-15-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rantanen J, Lehtinen S, Valenti A, et al. A global survey on occupational health services in selected international commission on occupational health (ICOH) member countries. BMC Public Health 2017;17:787 10.1186/s12889-017-4800-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020770supp001.pdf (24.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020770supp002.pdf (47.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020770supp003.pdf (86.2KB, pdf)