Abstract

Purpose

Germline mutations within the MEIS-interaction domain of HOXB13 have implicated a critical function for MEIS-HOX interactions in prostate cancer etiology and progression. The functional and predictive role of changes in MEIS expression within prostate tumor progression, however, remain largely unexplored.

Experimental Design

Here we utilize RNA expression datasets, annotated tissue microarrays, and cell-based functional assays to investigate the role of MEIS1 and MEIS2 in prostate cancer and metastatic progression.

Results

These analyses demonstrate a stepwise decrease in the expression of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 from benign epithelia, to primary tumor, to metastatic tissues. Positive expression of MEIS proteins in primary tumors, however, is associated with a lower hazard of clinical metastasis (HR = 0.28) after multivariable analysis. Pathway and gene set enrichment analyses identified MEIS-associated networks involved in cMYC signaling, cellular proliferation, motility, and local tumor environment. Depletion of MEIS1 and MEIS2 resulted in increased tumor growth over time in vivo, and decreased MEIS expression in both patient-derived tumors and MEIS-depleted cell lines was associated with increased expression of the pro-tumorigenic genes cMYC and CD142, and decreased expression of AXIN2, FN1, ROCK1, SERPINE2, SNAI2, and TGFβ2.

Conclusions

These data implicate a functional role for MEIS proteins in regulating cancer progression, and support a hypothesis whereby tumor expression of MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression confers a more indolent prostate cancer phenotype, with a decreased propensity for metastatic progression.

Keywords: Androgen Receptor, HOXB13, HOXB13(G84E), MEIS1, MEIS2, Biochemical Recurrence, Metastasis, Prostate Cancer, TALE

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and remains the second leading cause of cancer related death among American men (1). While localized prostate cancer is treated with either surgery or radiation with curative intent, 20 – 40% of patients will develop recurrent disease within ten years (2). Importantly, not all patients with biochemical recurrence have the same prognosis. Physicians face a difficult set of management decisions in balancing prevention of metastatic disease with appropriate therapy and avoidance of over-treatment in patients who may be at low risk for progression to metastatic disease (2). While currently established predictors of prostate cancer recurrence rely on commonly used pathologic criteria, including Gleason grade, there remains a need to both identify improved molecular markers of metastatic progression in prostate cancer. Furthermore, there is a critical need for a more thorough understanding of the biologic processes that alter prostate cancer behavior in order to more successfully risk-stratify and effectively treat patients (3).

MEIS1 and MEIS2 (Myeloid Ecotropic viral Insertion Site) are transcription factors that regulate important functions in cell fate determination during development and cell proliferation. A major function of MEIS proteins is to bind and direct HOX protein transcriptional specificity (4,5). Importantly, many identified germline HOXB13 mutations, which confer increased incidence of prostate cancer, occur within the MEIS-interaction domains of HOXB13 (4,6). Abnormalities in MEIS protein expression and function are implicated in a variety of cancers (4). However, both tumor suppressive and oncogenic functions of MEIS1 and MEIS2 are reported, but their tumor-regulatory function clearly depends upon the organ site under investigation (4). For example, increasing MEIS1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer cells results in limited cancer cell proliferation, thus implying a tumor suppressor function. In ovarian cancer, however, MEIS2 expression is negatively associated with patient survival in ovarian cancer, implying an oncogenic function (7,8). There is limited data on the function of MEIS in the normal and diseased prostate, and given the tissue-specific function of MEIS, an investigation of MEIS proteins in the prostate has the high potential to significantly enhance our understanding of the etiology of Prostate cancer progression. Such studies would represent a critical step in improving therapy decisions for patients, especially after treatment of localized cancer.

We originally identified a role for MEIS proteins in prostate cancer via a screen to identify cancer-associated differences between human prostate and seminal vesicle epithelial cells (9). This was based upon the rationale that there existed critical genes involved in prostate development and tissue homeostasis that strongly pre-disposed the prostate to carcinogenesis, yet also led to a significant lack of cancer initiation in the seminal vesicle (10,11). This approach identified both MEIS1 and MEIS2 as robustly expressed in prostate, but not seminal vesicle, epithelial cells (9). Differential mRNA expression of MEIS1 and MEIS2 within the Swedish Watchful Waiting cohort was sufficient to discern an 18-month vs. 40-month survival difference in patients with Gleason 6 and 7 tumors, respectively (9). These data suggested that retention of MEIS expression conferred a more favorable patient prognosis, indicating a tumor-suppressive role for MEIS expression in prostate cancer (9). More recently, Jeong et. al reported that MEIS2 expression was decreased in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) cells, and implicated MEIS2 as part of an intrinsic constitutively activated feed-forward signaling circuit formed during the emergence of CRPC (12). While these data implicate MEIS proteins as important in both prostate cancer initiation and progression to castration-resistant metastatic disease, studies to date have yet to define: 1) the prognostic utility of MEIS protein expression in progression to metastatic prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy; 2) whether decreased expression of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 occurs in prostate tumors; and 3) the functional necessity of MEIS expression to suppress tumor growth.

Here, we report that both MEIS1 and MEIS2 exhibit a step-wise decrease in expression during progression of prostate cancer from normal prostatic tissue, to localized prostate tumors, and finally to metastatic disease. We determine that MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression are significantly correlated in clinical data sets, demonstrating that expression of both MEIS genes is suppressed during prostate cancer progression. Using annotated tissue microarrays (TMA), we demonstrate that retention of MEIS expression is significantly associated with a lack of biochemical recurrence and clinically metastatic prostate cancer. We additionally show that MEIS-associated progression to metastatic prostate cancer is independent of known prognostic criteria, including Gleason grade. Analyses of RNA sequencing data from localized tumor and metastatic prostate cancer identified genes associated with both loss of MEIS and metastatic prostate cancer progression, thereby elucidating potentially novel cancer progression pathways associated with MEIS loss. Pathways associated with MEIS expression in the primary tumor include targets of cMYC, proliferation, differentiation, and cell adhesion. In addition, we demonstrate that loss of MEIS expression in prostate cancer cells increases tumor growth in vivo. Together these data support a significant functional role for MEIS proteins in prostate cancer, identify novel pathways associated with MEIS expression, and support the potential clinical utility of MEIS protein expression as a predictive biomarker of metastatic progression after radical prostatectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and Materials

R1881 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and was stored at −20°C in ethanol. Human prostate cancer cell lines were grown as previously described (13,14). All cultures were routinely screened for the absence of mycoplasma contamination using the ATCC Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Manassas, VA). Dr. John Issacs at The Johns Hopkins University generously provided the LAPC-4 cell line, which has been previously characterized and cultured in IMEM, 10% FCS, Pen-Strep, and 1nM R1881 (13). Cell authentication of LAPC-4 cells was confirmed via DDC Medical services (Fairfield, OH). RNA knockdown of MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression, both individual and dual knockdowns, was achieved using the pGIPZ lentiviral shRNA system (Dharmacon; Lafayette, CO). Lines were experimentally analyzed within ten passages of lentiviral gene delivery. Briefly, HEK293T packaging cells were plated in duplicate at 6E6 in 10-cm dishes. pGIPZ shRNA MEIS1 and MEIS2 plasmids were separately transfected using envelope and packaging vectors (Addgene; Cambridge, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Media containing the lentivirus was collected using a 0.45-µM filter and viral aliquots were added to 8.0 ml complete media and used to infect target LAPC-4 cells with 5 µg/ml Polybrene for 24 hours. Complete media was then replaced followed by selection with puromycin (1 µg/ml, Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Confirmation of knockdown of MEIS1 and MEIS2 was confirmed using both Q-RT-PCR and Western Blotting.

Western Blotting

Whole-cell lysates of 100,000 or more cells were used per lane. Western blotting was performed as previously reported (15). Briefly, cells were rinsed with cold PBS and scraped into RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, sonicated twice and re-suspended in 4× sample buffer (BioRad; Hercules, CA) supplemented with 10% Beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis MO). The Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Grand Island, NY) was used to determine protein concentration. 60 ug of protein was loaded on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed, and transferred to nitrocellulose (LI COR, Odyssey; Lincoln, NE) overnight at 4°C. The membrane was blocked overnight in 5% non-fat milk in TBS at 4°C. Primary antibodies used were: anti-MEIS1 (Ab19867, Abcam; Cambridge, MA), anti-MEIS2 (ARP34683_P050, Aviva Systems Biology; San Diego, CA), anti-Beta Actin, (Clone AC-15, Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). The secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse IRDye 800 CW or donkey anti-rabbit IRDye 680 from LI-COR Biosciences were used, and images captured using an infrared Odyssey scanner (LI-COR).

Quantitative Real Time PCR (Q-RT-PCR) Analyses

RNA was purified using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit with the optional DNAse digestion kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) and quality tested using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA). For standard Q-RT-PCR, extracted RNA was converted to cDNA by reverse transcription using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Expression levels of MEIS1, MEIS2, and RPL13A transcript were quantified using Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Invitrogen) using custom primers that captured all isoforms for MEIS1 and MEIS2 (primer sequences in Supplemental Table 1). Expression levels of MEIS associated targets were quantified using Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Invitrogen) using custom primers capturing the following genes: AXIN2, cMYC, CD142 (F3), FN1, ROCK1, SERPINE2, SNAI2, and TGF-β2, (Supplemental Table 1). Standard curves were used to assess primer efficiency and average change in threshold cycle (ΔCT) values was determined for each of the samples relative to endogenous RPL13A levels and compared to vehicle control (ΔΔCT). Experiments were performed in triplicate to determine mean standard error, and student’s t-tests performed with normalization to control to obtain p-values.

In vivo Tumor Formation

All animal studies were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, protocol number 72231). Ketamine/Xylazine anesthesia was used for all surgical procedures, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering. In vivo tumor formation of derived lines of LAPC-4 was performed via a sub-cutaneous inoculation of 750,000 cells in 4–6 week old male athymic nude mice (Harlan; Indianapolis, IN) using a 75% Matrigel (Corning; Bedford, MA) and 25% HBSS solution (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA). Host mice were surgically castrated at least one week prior to cell inoculation and implanted with a subcutaneous 1.4cm testosterone pellet in order to measure tumor take in a uniform androgen environment (16). Mice were allowed to recover and testosterone levels to equilibrate for 7 days before tumor injections.

Bioinformatics Analysis of GEO Arrays and RNA Sequencing Data

Microarray Data Set

For human clinical cases, MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression was queried from publically available Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data sets (GDS) of studies comparing benign prostate epithelia, benign prostate epithelia adjacent to Prostate cancer, primary and metastatic tumors. We used one microarray data set from the GEO database: GDS2545 containing 171 samples. Correlation in MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression was determined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, while Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and Kruskall-Wallis tests by ranks were used to determine differences in MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression between the above groups.

RNA-Seq Data Set

We obtained raw RNA-Seq FASTQ files of 25 prostate tumors, 3 benign glands, and 51 annotated metastases via dbGAP (phs000310.v1.p1 for tumors and benign glands; phs000915.v1.p1 for metastases) (17,18). These datasets were chosen based upon the quality of mRNA, sequencing depth, and annotation. The tumor datasets are from patients who had undergone prostate surgery without prior therapy, and the metastases are from patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer, some of which had received taxane, enzalutamide, or abiraterone treatment (17,18). The quality of raw reads was accessed by FastQC (v0.11.4). All reads were mapped to the human genome assembly (NCBI build 19) using STAR (v2.5.1b). Alignment metrics were collected by Picard tools (v2.8.1) and RSeQC (v2.6.4) (19). Transcripts were assembled from the aligned reads using Cufflinks and combined with known gene annotation. The expression level of transcripts was quantified using FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads)-based and read count-based methods. Transcript expression was normalized across samples. Primary tumor (PT) samples with MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression levels on the first tertile were classified as 'Low MEIS Expression' group. Samples that belong to this group are SRR341197, SRR341199, SRR341202, SRR341203 and SRR341204 (DBGap phs000310.v1.p1) (17). Samples with MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression levels on the third tertile were classified as 'High MEIS Expression' group. It includes SRR341196, SRR341201, SRR341213, and SRR341217 (DBGap phs000310.v1.p1) (17). Samples with FPKM <1.0 across all three categories (MEIS-High, MEIS-Low, and Metastasis) were not included in our analyses. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and isoforms were detected using Cuffquant-Cuffnorm-Cuffdiff suite (FPKM-based method, v2.2.1) (20) and featureCounts (21), DESeq2 (v1.14.1) (22), edgeR (v3.16.5) (23), or limma (v3.30.8) (24) (read count-based method). Transcripts were further filtered by fold change ≥ 1.5. Genes detected by at least more than one method were collected to create a list of high-confidence DEGs. Biological insights from candidate gene lists were gained by performing gene set enrichment analysis (GESA) and Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity® Systems) to identify functional categories or pathways that were significantly different.

GSEA Leading Edge Analysis

Three leading edge analysis categories were user-defined a priori as gene sets involved in the cancer related categories of “Cell Cycle & Proliferation”; “Adhesion & Motility”; and “Development, Differentiation, & Morphogenesis.” Patient RNAseq data defined in Figure 1 was loaded and run in GSEA 3.0 from the Broad institute (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea) to look for enrichment of gene sets in MEISHigh tumors compared to MEISLow tumors. Gene set groups from MSigDB that were included in initial GSEA analysis were GO (biological processes), Hallmark, Reactome and KEGG. Once analysis was complete, enriched gene sets were ordered smallest to largest by FDR q-value for significance. Leading edge analysis categories were then populated with any gene set in which the title fit that category of interest and the FDR q-value was <0.1. Reactome pathways were excluded to prevent confounding results due to nearly identical gene sets being used under two different Reactome titles (Jacquard >0.5). A leading edge analysis was then performed on each category separately using GSEA 3.0 to identify genes driving the enrichment of each category. For genes with at least 2 occurrences in an individual category, the overlap between categories was determined using the intersect() command in R software (v3.4.0) to identify the most likely MEIS associated genes with roles in Prostate cancer progression and metastasis. A heatmap of log(2) FPKM values of the 47 overlapping genes from all three categories was then generated using the MORPHEUS online tool from Broad Institute (http://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was run on the 47 candidate genes, and results were limited to only those titles that had adj-p <0.05 and referenced a clear and specific pathway, rather than a broader category or process.

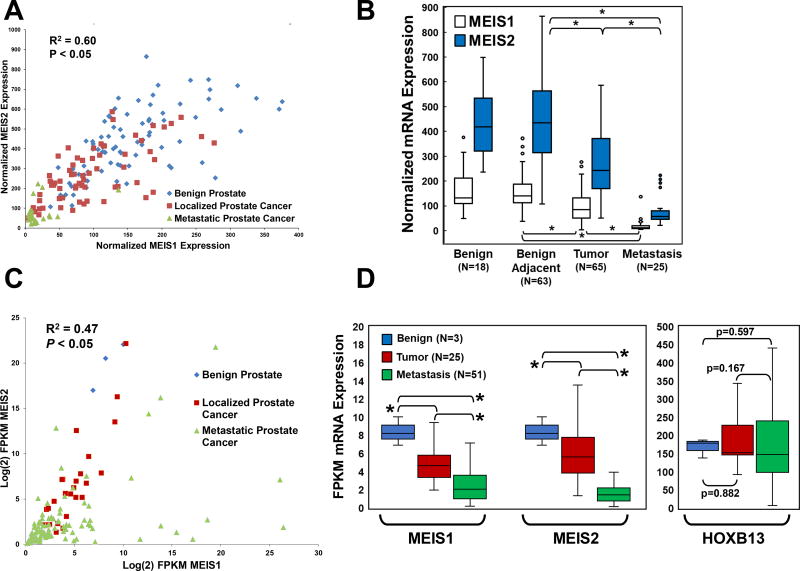

Figure 1. Correlation of MEIS1 and MEIS2 Expression and Changes through Prostate Cancer Progression.

(A) Scatter plot comparing MEIS1 expression vs. MEIS2 expression from gene expression array data obtained from GDS2545. Benign prostate epithelia are in blue, localized prostate tumor are red, and metastatic prostate cancer are green. These data document co-incident decrease expression of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 within prostate tumors and metastasis.

(B) Box and whisker plots of normalized mRNA expression of MEIS1 (white) and MEIS2 (blue) across benign prostate epithelia, benign prostate epithelia adjacent to tumor, localized prostate cancer, and metastatic prostate cancer (* p-value <0.05). Gene array data obtained from GDS2545.

(C) Scatter plot comparing Log(2) FPKM expression between MEIS1 (x-axis) and MEIS2 (y-axis) using publically-available RNA-Seq tumor and metastasis datasets. Benign prostate epithelia are in blue, localized prostate tumor are red, and metastatic prostate cancer are green. These data again document a co-incident decrease expression of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 within prostate tumors and metastasis.

(D) Box and whisker plots of log(2) FPKM of both MEIS1, MEIS2, and HOXB13 in RNA-Seq datasets. Changes in mRNA expression of MEIS1, MEIS2, and HOXB13 between benign prostate epithelia (blue), localized prostate tumors (red), and prostate cancer metastases (green) (* p-value <0.05). These data document significant step-wise decreases in MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression from benign to tumor to metastasis; no significant differences in HOXB13 expression were observed between benign, tumor, and metastasis.

Human Tissue Procurement and Generation of Tissue Microarray (TMA) for Immunohistochemistry

Two TMAs were procured for analysis of MEIS expression in prostate cancer. The University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC) TMA was constructed by the Human Tissue Research Center at the UCMC with Institutional Review Board approval and has been described previously (25). TMA samples were not used for any nucleotide-based analyses, but only for IHC. Briefly, the TMA contains 138 treatment-naive prostate cancer samples from radical prostatectomies performed at the University of Chicago between 1995 and 2002. Areas involved by prostate cancer and adjacent non-neoplastic prostatic tissue were punched (2 mm cores) from the formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded samples and arrayed with 72–108 cores per slide. Pre-operative characteristics including age, race, PSA, clinical tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) stage, and pathological extension was collected. The second TMA was obtained from the Prostate Cancer Biorepository Network (PCBN). The PCBN TMA was constructed from 235 patients undergoing radical prostatectomy from 1982 to 2002 who were part of the “Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy” study (26). The TMA contains four cores each of normal and cancerous tissue per patient. Pre-operative characteristics include age, race, BMI, PSA, primary and secondary Gleason grades, and clinical stage. Postoperative characteristics include pathologic Gleason grades, and pathological state (organ-confinement, extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle involvement or lymph node invasion). Of the 138 potential cases in the UCMC TMA, 39 cases were excluded because of lack of tissue on the slide or no prostate cancer was identified in the core. Of the 235 potential cases for analysis on the PCBN TMAs, 13 cases were excluded because no prostate cancer was identified on the core or tissue was missing from the slide. For both UCMC and PCBN TMAs, follow-up and outcomes data was obtained. Post-operative outcomes of interest included surgical margin status, adjuvant or salvage external radiation therapy (XRT), and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Survival outcomes of interest included biochemical recurrence (BCR), defined as first detectable PSA after radical prostatectomy, and time to clinical metastasis, defined as radiographic or pathologic evidence of distant metastatic disease.

Immunohistochemistry Staining and Evaluation

Immunohistochemistry staining (IHC) for MEIS (sc-81986 from Santa Cruz; Dallas, TX) was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) sections managed by the University of Chicago Human Tissue Resource Core facility. It should be noted that the sc-81986 antibody recognizes epitopes present on both MEIS1 and MEIS2 proteins, as demonstrated in Supplemental Figure 1A–D. After deparaffinization and rehydration, tissues were treated with antigen retrieval buffer (S1699 from DAKO; Glostrup, Denmark) in a steamer for 20 minutes. Anti-MEIS antibody at 1:300 was applied for 16 hours at 4° C in a humidity chamber. Following TBS wash, the antigen-antibody binding was detected with Envision+system (DAKO, K4001 for mouse primary antibodies) and DAB+Chromogen (DAKO, K3468). Tissue sections were briefly immersed in hematoxylin for counterstaining and were cover-slipped.

Tissues were analyzed by a trained genitourinary pathologist and scored on percentage of cells with positive nuclear staining (0 = no staining; 1 = 1–5% positive cells; 2 = 5–50% positive cells; and 3 = 50–100% positive cells). Patients were then divided into two groups for analysis: Patients with a composite score of 0–1 were considered MEIS negative, whereas patients with a score ≥2 were considered MEIS positive. For images, slides were digitized using a Pannoramic Scan Whole Slide Scanner (Cambridge Research and Instrumentation, Hopkinton, MA) and images captured using the Pannoramic Viewer software version 1.14.50 (3DHistech, Budapest, Hungary).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata®, version 13.0 (College Station, TX). Wilcoxon-rank sum, Kruskall-Wallis test by ranks, one-way ANOVA, Fisher exact tests, and χ2 tests were used to compare baseline pre- and post-operative characteristics between MEIS positive and MEIS negative patients. Univariable analysis to determine whether MEIS score predicted time to BCR, and clinical metastasis, was conducted using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, as well as Kaplan Meier curves with log rank tests. A multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression model was constructed to evaluate whether MEIS score predicted BCR and clinical metastasis.

For bioinformatics analysis, a Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine linear correlation between MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression in both GEO and RNA-Seq datasets. Kruskall-Wallis test by ranks and Wilcoxon-rank sum tests was used to compare MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression between benign prostate epithelia, normal prostate epithelia adjacent to Prostate cancer, localized Prostate cancer, and metastatic Prostate cancer in both datasets.

RESULTS

Expression Analyses Reveal Correlated Expression of MEIS1 and MEIS2 and Progressive Loss of Total MEIS Expression During Prostate Cancer Progression

To better understand the landscape of MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression, both in relation to each other and in relation to progression from benign to metastatic disease, expression analyses was conducted on two distinct publically-available gene expression datasets. The first dataset was the GEO GDS2545 microarray dataset derived from 170 prostate patient specimens; 10% of which were normal prostate epithelia (n = 17), 37% were benign prostate epithelia adjacent to prostate cancer (n = 63), 38% were localized prostate cancer (n = 65), and 15% were distant metastases (n = 25) (27). The second dataset was comprised of two RNA-Seq datasets consisting of 79 patients, 4% of which were normal prostate epithelia (n = 3), 31% were localized prostate cancer (n = 25), and 65% were of metastatic prostate cancer (n = 51) (17,28).

We initially sought to determine whether one or both MEIS genes demonstrated correlative changes in expression among patient-derived data sets. Comparison of MEIS1 to MEIS2 expression in gene array datasets showed a significant positive correlation between MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression across the benign, localized, and metastatic prostate cancer (Figure 1A; R2 = 0.60; P <0.05). After determining that MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression are indeed positively correlated, we sought to identify the pattern of MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression changes across different biological states of the prostate, from benign prostate, localized prostate cancer, and metastatic prostate cancer. Comparative analyses demonstrate significant step-wise decreases in both MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression across normal prostate, localized prostate cancer and metastatic prostate cancer in the GEO data set (Figure 1B). Median MEIS1 expression was nearly equivalent between benign prostate epithelia samples and normal prostate epithelia adjacent to tumor (131.2 vs. 140.3, P >0.05). However, median MEIS1 expression was significantly lower between normal prostate epithelia and localized prostate cancer (140.3 vs. 84.4, P <0.05), and significantly lower still between localized and metastatic prostate cancer (84.4 vs. 11.1 P <0.05). MEIS2 expression followed a similar stepwise decrease, with median normalized expression decreasing from 434.7 in normal prostate epithelia adjacent to tumor, to 242.0 in localized and 57.6 in metastatic prostate cancer (Figure 1B, P <0.05).

Similarly, comparison of MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression in an independent RNA-Seq dataset confirmed a significant positive correlation between MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression (Figure 1C; R2 = 0.47; P <0.05) (17,28). Analyses of mRNA transcript quantitation likewise demonstrated a significant stepwise decrease in both MEIS1 and MEIS2 from benign epithelium to tumor (MEIS1: 8.37 to 4.95; MEIS2: 19.87 to 6.83; P<0.05), and from tumor to metastasis (MEIS1: 4.95 to 3.52; MEIS2: 6.83 to 2.56; P<0.05) (Figure 1D). Interestingly, there was no significant difference in HOXB13 mRNA expression different between benign, tumor, and metastatic tissues (Benign: 167.68 FPKM, Tumor: 197.39 FPKM, Metastases: 168.34 FPKM, P =0.356) (Figure 1D). These data imply that, while mutations in HOXB13 are clearly important in prostate tumor imitation, changes in HOXB13 mRNA expression do not appear to be associated with cancer progression. However, the range of tumor MEIS expression does suggest the presence of a subset of tumors with high MEIS expression (Figure 1C and 1D). Collectively, these data imply an important role for MEIS proteins in prostate cancer progression, and support a model whereby low MEIS tumor expression correlates with metastatic progression, or conversely that high MEIS tumor expression is associated with a lack of metastatic progression.

Tumor MEIS Expression is Associated with a Lack of Biochemical Recurrence and Progression to Clinically Metastatic Disease

Given the positive correlation of MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression and the identification of a decrease in both MEIS1 and MEIS2 through prostate cancer progression, we developed a robust and reliable immunohistochemical detection of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 to simultaneously detect both forms (Supplementary Figure 1A–D). Furthermore, we validated a correlation between MEIS mRNA and protein expression by analyzing a series of primary prostate epithelial and stromal cultures (Supplemental Figure 1E–F). We stained two different sets of prostate tissue micro-arrays, both of which included extensive patient annotation and follow-up. An a priori decision was made to identify tumors as “MEIS-positive” if their respective tissue samples contained greater than 5% of prostate cancer cells positive for MEIS expression (Figure 2A). A total of 321 cases were stained for MEIS expression, with 11% (n = 36) positive for MEIS expression. Analyses of pre-operative and peri-operative characteristics documented that there was no difference in age, race, pre-operative PSA, Gleason grade, clinical T stage, pathological extension, or surgical margin status between the MEIS-positive and MEIS-negative tumors (Supplementary Table 2).

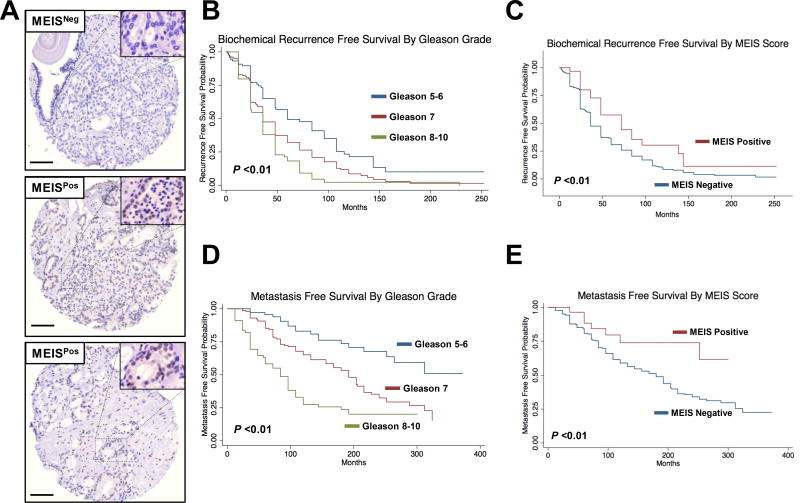

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical Staining of Prostate Tissue and MEIS-Associated Biochemical Recurrence and Metastasis.

(A) Representative staining of prostate tissue showing heterogeneity of total MEIS expression (10× magnification). Tumors with greater than 5% of cancer cells positive were considered MEIS-positive.

(B–E) Kaplan-Meier log-rank survival estimates of PSA free survival for (B) All patients stratified by Gleason grade low (5–6), intermediate (7), and high (8–10). (C) Stratified by MEIS-negative tumors versus MEIS-positive tumors. Kaplan-Meier log-rank survival estimates of metastasis free survival for (D) All patients stratified by Gleason grade low (5–6), intermediate (7), and high (8–10). (E) Stratified by MEIS-negative tumors versus MEIS-positive tumors.

To determine whether MEIS expression was associated with prostate cancer progression, we analyzed post-operative outcomes between patients bearing either MEIS-positive or MEIS-negative tumors (Table 1). This analyses demonstrated that MEIS-negative patients are significantly more likely to have biochemical recurrence (84% vs. 56% P <0.01) and clinically metastatic disease (51% vs. 19%, P <0.01) compared to MEIS-positive patients. It is not surprising, then, that MEIS-negative patients are more likely to receive androgen deprivation therapy for metastatic disease compared to MEIS-positive patients (36% vs. 14%, P = 0.02). Similarly, MEIS-negative patients were nearly significantly more likely to receive some form of external radiation therapy (either for salvage therapy or metastatic disease) compared to MEIS-positive patients (29.2% vs 25%, P = 0.078). However, despite a higher proportion of patients receiving additional treatment for Prostate cancer progression in the MEIS-negative group, there was a higher proportion of cancer specific death in the MEIS-negative group compared to the MEIS-positive group (37% vs. 19%, P = 0.036).

Table 1.

Post-Operative Outcomes Between MEIS-Positive and MEIS-Negative Tumors

| <5% Cell MEIS Positive (%) | >5% Cell MEIS Positive (%) | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Biochemical Recurrence, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 46 | (16.1) | 16 | (44.4) | |

| Yes | 239 | (83.9) | 20 | (55.6) | |

|

| |||||

| ADT, n (%) | 0.02 | ||||

| None / Unknown | 135 | (47.4) | 24 | (66.7) | |

| Salvage | 47 | (16.5) | 7 | (19.4) | |

| For Metastatic Disease | 103 | (36.1) | 5 | (13.9) | |

|

| |||||

| XRT, n (%) | 0.078 | ||||

| None / Unknown | 202 | (70.9) | 27 | (75) | |

| Salvage | 80 | (28.1) | 7 | (19.4) | |

| For Metastatic Disease | 3 | (1.1) | 2 | (5.6) | |

|

| |||||

| Metastasis, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| No Metastasis | 137 | (48.9) | 29 | (80.6) | |

| Clinical Metastasis | 143 | (51.1) | 7 | (19.4) | |

|

| |||||

| Cancer-Specific Survival, n (%) | 0.036 | ||||

| Alive | 179 | (62.8) | 29 | (80.6) | |

| Dead from PCa | 106 | (37.2) | 7 | (19.4) | |

|

| |||||

| Overall Survival, n (%) | 0.075 | ||||

| Alive | 126 | (44.2) | 22 | (61.1) | |

| Dead | 159 | (55.8) | 14 | (38.9) | |

In our cohort, time to biochemical recurrence (BCR) was determined as months between radical prostatectomy and first positive post-operative PSA. Of the 321 patients available for survival analysis, one patient was excluded due to lack of follow-up. Post-radical prostatectomy BCR occurred in 81% (n = 259) patients. The median recurrence-free survival (RFS) time was 36 months for the entire cohort. Figure 2B shows BCR of all patients stratified by Gleason grade into low (GG 5–6), intermediate (GG 7), and high (GG 8–10) risk groups. As expected, patients with higher Gleason grade had worse RFS compared to the lower Gleason grade group (log rank, P <0.01). Figure 2C shows BCR stratified by MEIS score. Median follow up time was 36 months in MEIS-negative and 48 months in MEIS-positive tumor-bearing patients. A positive MEIS score was significantly associated with improved BCR free survival compared to a negative MEIS score, with 5 and 10-year recurrence free survival of 57% and 30% in MEIS positive patients, compared to 5 and 10 year recurrence free survival of 31% and 9% in MEIS negative patients, respectively (log rank, P <0.01). Using a univariable Cox analysis, a positive MEIS score is associated with a lower risk of BCR (HR = 0.57). These data support that a positive MEIS score in primary prostate tumors is associated with lower risk of BCR, and that tumor MEIS expression may exhibit a more indolent clinical course of prostate cancer progression.

While biochemical recurrence is frequently utilized as a surrogate marker to assess prostate cancer progression, it is known that not all patients with biochemical recurrence will progress to clinically metastatic disease (2). Therefore, we analyzed our TMA datasets to determine whether positive MEIS expression was associated with a lack of progression to clinically metastatic disease, defined as radiographic or pathologic evidence of distant cancer metastasis. Of the 321 patients available for analysis, 8 patients were excluded for lack of follow-up. Progression to clinically metastatic disease occurred in 47% (n = 150) of patients in our cohort. The median metastasis free survival (MFS) time was 96 months for the entire cohort. Figure 2D shows MFS of all patients stratified by Gleason grade into low (GG 5–6), intermediate (GG 7), and high (GG 8–10) risk groups. Similar to the BCR data in Figure 2B, patients with higher Gleason grade had worse MFS compared to the lower Gleason grade group (log rank, P <0.01). Figure 2E illustrates MFS stratified by MEIS score. Median follow up time was 96 months in MEIS-negative patients and 91 months in MEIS-positive patients. A positive MEIS score was significantly associated with improved MFS compared to a negative MEIS score, with a 10 year MFS of 74% in MEIS-positive patients, compared to only 59% in MEIS-negative patients, respectively (log rank, P = 0.0133). A univariable Cox analysis demonstrated that a positive MEIS score is associated with a lower risk of progression to clinically metastatic disease (HR = 0.40). Given the critical importance and treatment ramifications in identifying patients likely to progress to true clinically metastatic prostate cancer, we performed a multivariable Cox regression analysis to determine if positive MEIS score was predictive of a lower risk of clinically metastatic disease independent of known prognostic factors (Table 2). Adjusting for age, race, pre-operative PSA, clinical T stage, Gleason grade, pathologic extension, and surgical margin status, a positive MEIS score was still predictive of a lower risk of clinically metastatic disease compared to MEIS negative patients (Table 2; multivariate HR = 0.28, P = 0.033). Taken together, these data demonstrate that a positive MEIS score in primary prostate tumors is independently associated with a lower risk of progression to metastatic disease, implying that MEIS proteins play a significant clinical role in stratifying patients at risk for prostate cancer progression.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analyses of MEIS-Positive vs. MEIS-Negative Tumors

| Risk of Biochemical Recurrence | Risk of Clinical Metastasis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P-Value | HR | 95% CI | P-Value | |

|

| ||||||

| MEIS Percent | ||||||

| <5% | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| >5% | 0.76 | (0.43 – 1.37) | 0.37 | 0.28 | (0.08 – 0.90) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| Age | 1.02 | (0.99 – 1.05) | 0.18 | 0.98 | (0.95 – 1.02) | 0.39 |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Other | 0.68 | (0.25 –1.81) | 0.44 | 0.29 | (0.07 – 1.27) | 0.10 |

|

| ||||||

| PSA | 1.00 | (0.99 – 1.02) | 0.66 | 0.99 | (0.97 – 1.01) | 0.43 |

|

| ||||||

| Gleason Grade | ||||||

| 5–6 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 3+4 or 4+3 | 1.28 | (0.76 – 2.17) | 0.35 | 1.51 | (0.66 – 3.46) | 0.33 |

| 8–10 | 1.57 | (0.89 – 2.74) | 0.12 | 2.58 | (1.09 – 6.12) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical T Stage | ||||||

| T1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| T2 | 1.17 | (0.70 – 1.95) | 0.56 | 2.42 | (0.96 – 6.09) | 0.06 |

| T3–4 | 1.08 | (0.50 – 2.34) | 0.85 | 2.95 | (0.94 – 9.22) | 0.06 |

|

| ||||||

| Pathological Extension | ||||||

| Organ Confined | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Extra-Prostatic Extension | 1.21 | (0.62 – 2.39) | 0.58 | 0.99 | (0.37 – 2.70) | 0.99 |

| Seminal Vesicle Invasion | 1.45 | (0.65 – 3.25) | 0.37 | 2.20 | (0.76 – 6.38) | 0.15 |

| Lymph Node Positive | 1.84 | (0.87 – 3.90) | 0.11 | 2.62 | (0.95 – 7.20) | 0.06 |

|

| ||||||

| Surgical Margins | ||||||

| T1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| T2 | 1.18 | (0.81 – 1.71) | 0.40 | 0.75 | (0.45 – 1.25) | 0.26 |

Identification of MEIS Associated Networks and Gene Sets Involved in Prostate Cancer Progression

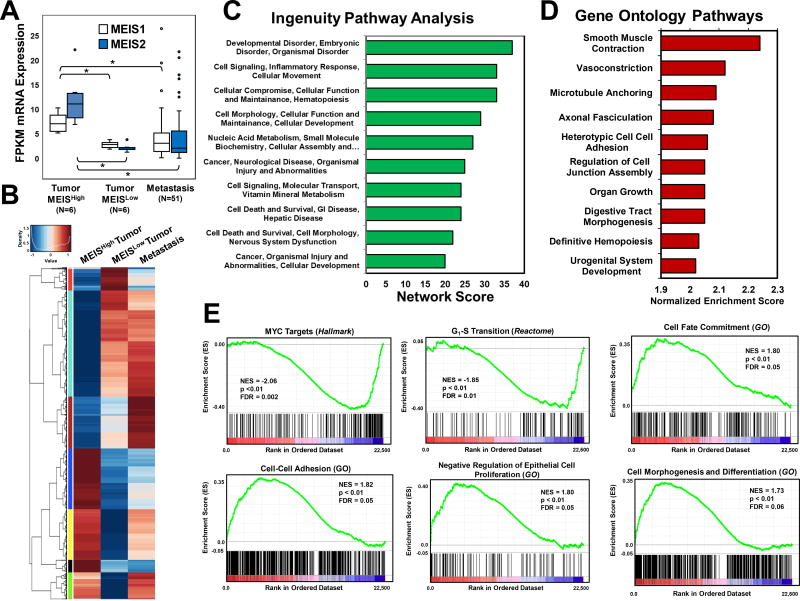

Given that protein expression of MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression was significantly associated with a lack of biochemical recurrence and progression to clinically metastatic disease, we hypothesized that comparing MEISHigh to MEISLow tumors would identify differentially expressed gene sets and networks associated with prostate cancer progression. Moreover, differentially-expressed genes between MEISHigh to MEISLow tumors would identify genes associated with MEIS expression and function. Using the RNA-seq datasets described in Figure 1, we stratified our primary prostate tumors into tertiles, and compared differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between MEISHigh vs. MEISLow tumors, as well as all metastatic specimens in order to identify potential MEIS-associated genes involved in Prostate cancer progression (Figure 3A). As expected based upon our subgrouping, both MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression is significantly greater in the MEISHigh group compared to either the MEISLow tumor group as well as the metastatic group (Figure 3A). Furthermore, MEIS expression is not significantly different between the MEISLow tumors and metastatic prostate cancer (Figure 3A). Pair-wise analyses identified 1804 differentially expressed genes (DEG) between the MEISHigh and MEISLow prostate primary tumor groups which also demonstrated similar and non-significant expression between the MEISlow and metastatic samples (Figure 3B and Supplemental Table 3). These genes thus have similar expression between more aggressive MEISLow tumors and metastasis, yet significantly distinct expression in the more indolent MEISHigh tumors. These DEG’s were analyzed using both Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) and Gene Ontology (GO) in order to identify candidate gene sets and networks associated with both MEIS expression and prostate cancer progression (Figure 3C and 3D). IPA identified several networks involved in cellular proliferation and survival, as well as inflammatory response and cellular movement (Figure 3C). Gene Ontology (GO) analyses identified pathways that are significantly associated with smooth muscle contraction, vasoconstriction, microtubule anchoring, cell to cell adhesion, and regulation of cell junction assembly (Figure 3D). Further analyses utilizing Gene Set Enrichment Analyses (GSEA), which incorporates directionality of gene changes between groups, documented that more indolent MEISHigh tumors have decreased expression of MYC targets and genes involved in G1-S transition, and increased expression of genes involved in cell fate commitment, cell-cell adhesion, negative regulation of proliferation, and cell morphogenesis and differentiation (Figure 3E). Indeed, previous data from Zebrafish have demonstrated regulation of Myc by Meis proteins (29). Collectively, these analyses support a model whereby MEIS-positive prostate tumors are less proliferative, more differentiated, and have increased cell-cell adhesion, thereby promoting a more indolent tumor phenotype.

Figure 3. Identification Gene Sets and Networks Associated with MEIS and Prostate Cancer Progression.

(A) Box and whisker plots of MEIS1 and MEIS2 mRNA expression in MEISHigh tumors (n=6), MEISLow tumors (n=6), and metastasis (n=51) form RNA-Seq datasets. FPKM values for all genes were used to identify genes that were similar between MEISLow tumors and metastasis, and significantly different (1.5-fold, FDR<0.05) in the MEISHigh tumors.

(B) Heat map of differentially expressed genes between MEISHigh (left), MEISLow (center), and metastatic prostate cancer (right). Scores range from low expression (blue) to high expression (red). Gene lists and FPKM values are listed in Supplemental Table 3.

(C) Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) of the top ten networks derived from differentially expressed gene set between MEISHigh, MEISLow, and metastatic prostate cancer datasets.

(D) Top ten Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Processes derived arranged by normalized enrichment score of differentially expressed gene set between MEISHigh, MEISLow, and metastatic prostate cancer datasets.

(E) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of significantly altered pathways between MEISHigh and MEISLow tumors. Normalize enrichment scores (NES) demonstrate that MEISHigh tumors have decreased expression of cMYC targets and genes regulating G1-S transition, and increased expression of genes involved in in cell fate commitment, cell-cell adhesion, negative regulators of cell proliferation, and cell morphogenesis and differentiation. Gene sets were obtained and analyzed against the Hallmark, Gene Ontology (GO), and Reactome datasets.

Loss of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 is Associated with Increased Tumor Growth in vivo

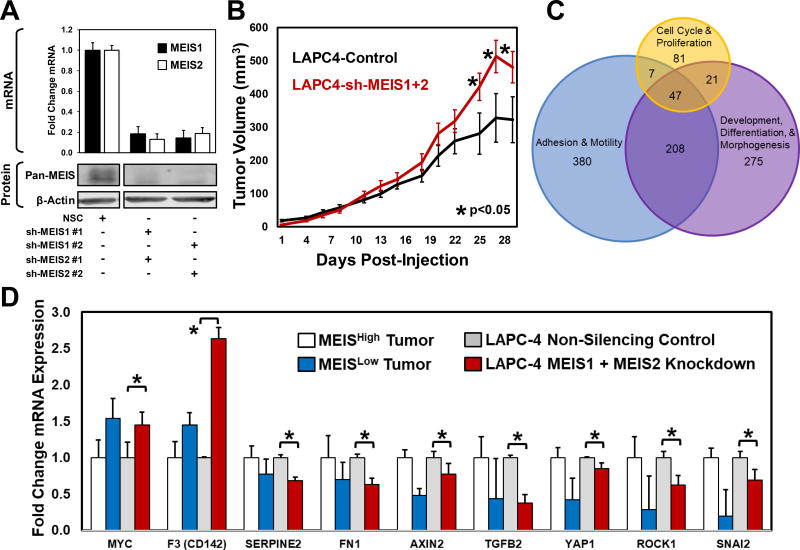

Given our clinical and bioinformatic data support the hypothesis that tumor MEIS expression confers a more favorable clinical prognosis, we hypothesized that depletion of MEIS expression in prostate cancer cells would result in a more aggressive tumor phenotype. To begin elucidating how MEIS expression is decreased in prostate tumors, we analyzed TCGA datasets for promoter methylation, as well as utilized pharmacologic approaches to increased MEIS expression in cell lines. These data demonstrated significant promoter methylation of MEIS1, and our ability to increase MEIS2 expression utilizing three distinct HDAC-inhibitors (Supplemental Figure 2). To test the phenotypic and function impact of depleting MEIS expression, we created LAPC-4 prostate cancer cells harboring knockdowns of MEIS1, MEIS2, and both MEIS1 and MEIS2 (Figure 4). Figure 4A illustrates knockdown of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 mRNA and protein. In vivo sub-cutaneous xenografts of LAPC-4 cells depleted of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 demonstrate a significant increase in tumor size within 25 days post-injection, with an 185mm3 and 159mm3 increase in mean tumor volume compared to controls at day 27 and 29, respectively (Figure 4B; P <0.05). Interestingly, single knockdown of either MEIS1 or MEIS2 demonstrates that decreased expression of either individual MEIS protein alone is not sufficient to enable increased tumor volume, as there was no difference in mean tumor volume between either MEIS1 or MEIS2 knockdown and controls (Supplemental Figure 3A). These data support a role for MEIS proteins in negatively regulating tumor growth, as their depletion led to increased tumor volume over time in vivo.

Figure 4. Functional Characterization of Total MEIS Knockdown LAPC-4 Cells.

(A) Assessment of MEIS1 and MEIS2 knockdown in LAPC-4 cell using RT-PCR (top) and Western blot analysis (bottom). Two shRNA constructs against MEIS1 and two shRNA constructs against MEIS2 were utilized to control for off-target effects. To determine MEIS1 and MEIS2 protein levels after shRNA depletion, western blot analyses was conducted using a mouse monoclonal targeting both MEIS1 and MEIS2 (Pan-MEIS).

(B) Xenograft growth of MEIS1 and MEIS2 double knockdown LAPC-4 cells injected subcutaneously on the flanks of hormonally-intact male nude mice compared to non-silencing controls. Differences in tumor volumes at days 25, 27 and 29 post-injection were statistically significant (Control N=8; double knockdown N=8; * p-value <0.05).

(C) Venn Diagram of MEIS-associated genes prioritized using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) leading edge analyses. The GSEA leading edge analyses identifies genes that potentially drive a phenotype, and are consistently at the “leading edge” of multiple pathway categories. This analysis was performed on pathways associated with Cell Cycle and Proliferation; Adhesion and Motility; and Development, Differentiation and Morphogenesis, and leading edge genes common to all three were identified (n=47). A heatmap demonstrating differential expression of these 47 genes is shown in Supplemental Figure 3B.

(D) Quantitative real-time PCR mRNA analyses analysis of candidates using cDNA of MEIS1 and MEIS2 double knockdown LAPC-4 cells compared to non-silencing controls. Data represents mean and SEM of experiments conducted in triplicate (* p-value <0.05). The fold change in mRNA expression within LAPC-4 cells with MEIS depletion is graphed next to the fold change in expression between MEISHigh vs. MEISLow tumors, which was statistically tested using RNA-seq analyses platforms to identify differentially-expressed genes.

Based upon our analyses of clinical RNA-seq specimens, we sought to identify and validate the expression of several key genes associated with differences in tumor MEIS expression. Initial GSEA analyses of patient-derived RNA-seq specimens determined that prostate tumors with higher MEIS expression appear to be less proliferative, more differentiated, and have increased cell-cell adhesion, thus encouraging a less aggressive tumor phenotype (Figure 3). In an attempt to identify specific molecular targets associated with MEIS expression in prostate cancer, we used those three phenotypic categories to develop a GSEA leading edge analysis. This analysis first identified genes driving the enrichment of gene sets involved in cell cycle and proliferation; development, differentiation, and morphogenesis; or adhesion and motility (Figure 4C and Supplemental Figure 3B). The intersection of leading edge genes occurring in all three phenotypic categories identified 47 candidates associated with MEIS expression in prostate cancer (Figure 4C and Supplemental Figure 3B).

In order to validate the association between MEIS expression and the expression of candidate factors that have established roles in prostate cancer progression, we conducted qRT-PCR on a series of candidate genes identified by our GSEA analyses, leading edge analyses, and genes with established roles in tumor progression using our LAPC-4 MEIS-knockdown cells. The fold change in mRNA expression within the MEIS-depleted cells was then compared to the fold change expression between MEISHigh vs. MEISLow tumors (Figure 4D). Importantly, we observed significantly increased expression of cMYC mRNA in LAPC-4 cells that had depleted MEIS expression. Deviant expression of the cell surface glycoprotein CD142 (also known as coagulation factor 3, or F3), the serine protease SerpinE2 (Serpin Family E Member 2), and the matrix protein FN1 (Fibronectin 1) have been implicated in several cancers for its tumor promoting effects as well as their roles in remodeling the tumor micro-environment (30–32). In LAPC-4 cells with depleted MEIS expression, we observe a significant increase in CD142 expression, and decreased expression of SERPINE3 and FN1 (Figure 4D). In all instances, the directional change in expression matches that of MEISLow vs. MEISHigh tumors, whereby when MEIS is depleted in LACP-4 cells the change in expression correlates similarly with MEISLow tumor expression (Figure 4D). Changes in these genes upon MEIS knockdown suggest that changes in local tumor environment may play a role in MEIS-associated increases in tumor volume in vivo.

Decreased expression of AXIN2 is associated with cellular invasion and proliferation as well poor prognosis in prostate cancer and regulation of cMYC pathway members (33,34). Changes in the expression of TGF-β2 (Transforming growth factor beta 2) are also implicated in prostate cancer progression (35,36). ROCK1 (Rho Associated Coiled-Coil Containing Protein Kinase 1) is a protein serine/threonine kinase that is activated when bound to the GTP-bound form of RHO; expression and genetic variation of ROCK1 has an established role in prostate cancer progression and has been reported to function via cMYC (37,38). SNAI2 (Snail Family Transcriptional Repressor 2, also referred to as SLUG) is a member of the Snail family of C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factors and is critically involved in regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT). Downregulation of SNAI2 is associated with increased EMT and regulation of E-cadherin (39–41). In both prostate tumor RNA-seq datasets, and via qRT-PCR in LAPC-4 cells with depleted MEIS1 and MEIS2, we observe decreased expression of AXIN2, TFGβ2, ROCK1, and SNAI2 (Figure 4D, P <0.05 for LAPC-4 analyses). Collectively, these data implicate a causal function for MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression in regulating genes involved in cancer progression and metastasis, including cMYC, cMYC targets, and critical mediators of cell adhesion and differentiation.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that expression of MEIS1 and MEIS2 have a significant role in blocking prostate cancer progression and metastasis. We observe a stepwise decreased in the expression of both genes from benign prostate epithelia to localized prostate cancer and further still with progression to metastatic prostate cancer. Furthermore, we have shown that subsequent retention of total MEIS expression in localized prostate cancer is significantly associated with a lack of biochemical recurrence and progression to clinically metastatic disease. Finally, we have demonstrated that loss of both MEIS proteins is necessary to increase tumor growth in vivo, and that this phenotype is associated with changes in pathways that regulate cell proliferation, cell adhesion and motility, and cellular differentiation and morphogenesis. Together, this data supports the hypothesis that retention of MEIS expression in prostate cancer confers a more indolent prostate cancer phenotype, with a decreased propensity for metastatic progression.

Germ line mutations of HOXB13, particularly the G84E mutation, have been identified in men with early onset familial prostate cancer and validated in several cohorts (6,42). Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that the G84E mutation confers a more aggressive phenotype of prostate cancer, with G84E patients having a significantly higher diagnosis PSA, higher Gleason score, and a higher likelihood of positive surgical margins at time of radical prostatectomy (43). Based upon data presented here, one potential mechanism of HOXB13(G84E)-associated tumor aggressiveness could result from a disruption or modulation of MEIS interaction by the G84E mutation, leading to defective MEIS-HOX signaling and a loss of MEIS-mediated tumor suppression. We document that HOXB13 mRNA expression is not significantly different between normal prostate epithelia, prostate tumors, and metastasis; this observation implies that expression changes in HOX co-factors such as MEIS1 and MEIS2, but perhaps not HOX proteins themselves, have a more significant role in prostate cancer progression.

While our study suggests that retention of MEIS proteins leads to a clinically more indolent form of prostate cancer using a combination of bioinformatic, histological, and in vivo approaches, it is not without limitations. First, while our bioinformatics data strongly suggest a step-wise loss of both MEIS proteins through prostate cancer across multiple data sets, we lack the granularity necessary to observe changes in MEIS through cancer progression within individual patients or through our model systems. Second, while our TMA datasets included a relatively large sample size of patients, only 11% of patients were positive for MEIS expression, and so our results would likely need to be subsequently validated using larger data sets. Finally, while our data strongly supports previous studies that implicate MEIS as prognostic in prostate cancer, and that loss of MEIS results in increased tumor growth, we have yet to identify the exact mechanism by which loss of MEIS confers a more aggressive prostate cancer phenotype. One potential mechanism, purported by Cui et al., suggests that MEIS1 negatively regulates AR function, and thus retention of tumor MEIS expression could confer a more active and pro-differentiation function for AR (44,45). However, our data does suggest a number of candidate MEIS-associated genes that regulate cell proliferation and the local tumor microenvironment. Ultimately, these limitations also present obvious future directions for research, which include mouse models that develop metastatic prostate cancer, analyses of metastatic prostate cancer samples from patients, and ChIP-Seq based approaches to mechanistically decipher MEIS function.

Clinically, the identification of HOX cofactors such as MEIS serves two primary purposes. First, the ability to develop new biomarkers to better risk stratify patients is greatly needed. Indeed, in this study, we demonstrate that MEIS expression can be prognostic for biochemical recurrence and metastasis in the post-prostatectomy setting, which has implications for the length and aggressiveness of surveillance patterns and for the use of adjuvant or salvage therapies. Several large randomized trials have shown that use of adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with greater BCR free survival compared to observation for patients undergoing radical prostatectomy with high-risk features, but this was at the cost of increased short and long-term side effects (46,47). Given that MEIS expression was associated with a lower hazard of biochemical recurrence and clinical metastasis independent of known prognostic risk factors, utilizing biomarkers such as MEIS may enable better risk stratification of patients leading to appropriate aggressive response for those at highest risk of disease progression, while avoiding harmful side effects in those with more indolent disease. Second, while survival for prostate cancer has continued to improve, it remains the second leading cause of cancer related death among American men. As such, there needs to be continued efforts to identify novel gene networks and pathways that confer more aggressive prostate cancer behavior, as these genes may represent potentially novel targets for future therapies. Our data suggests that MEIS proteins may represent a previously largely unexplored target for the identification of efficacious targets and the development of future cancer therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

(A) Western blotting of lentivirally-infected HEK293T cells expressing expression constructs for either human MEIS1 (LV-MEIS1) or MEIS2 (LV-MEIS2). This data demonstrates that the Santa Cruz 63-T antibody, specified to react only with MEIS2, in fact recognizes both MEIS1 and MEIS2.

(B–D) Immunhistochemical staining of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 using the 63-T antibody in human prostate (B), human liver and bile duct (B, positive control), and a xenograft tumor of CWR22rV1 prostate cancer cells (C, negative control). CWR22Rv1 cells have low to undetectable MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression.

(E–F) Correlation between MEIS mRNA and protein expression using primary prostate epithelial (PrEC) and stromal cultures (PrSC). Lines were derived using protocols described in Chen et al (9).

(A) Visualization of MEIS1 (top) or MEIS2 (bottom) methylation profiles from TGCA Research Network (48), Illumina 450K array (49). Targeted gene queries were obtained via Wanderer software (50). Profile plot displays average gene-specific methylation between normal (blue marks) versus tumor (red marks) human prostate tissue. CpG islands noted in green. Methylation marks displayed artificially evenly from the TSS. Vertical axis indicates beta values for each probe. CpGs showing statistical difference between normal and tumor are indicated with an asterisk (Wilcoxon adjusted p-value < adj. pval threshold 0.001).

(B) FPKM values from publically available RNA-sequencing of LNCaP cells treated with one of three epigenetic modifying drugs (Panobinostat, SAHA or TSA) at a high or low dose for each (51). MEIS1 (purple) and MEIS2 (blue) FPKM expression shown.

(C) Western blot analysis of PrCa cell line CWR22Rv1 when treated with HDACi’s. Densitometry relative to vehicle treatment indicated above each panel.

(A) Growth curves of MEIS1 or MEIS2 single knockdown LAPC-4 cells injected subcutaneously on the flanks of castrated and testosterone implanted male nude mice compared to non-silencing controls at day 25,27 and 29 respectively, showing no difference in growth with single knockdown compared to controls.

(B) Heatmap illustrating the expression of the 47 genes identified from our GSEA Leading Edge analyses. MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression is also included.

Acknowledgments

Funding: DOD PCRP PC130587 (PI: Vander Griend); NWU/UC/NSUHS Prostate SPORE (P50 CA180995; PI: Catalona); the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center (UCCCC), especially the Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA014599); H. Brechka and C. VanOpstall were supported by the Cancer Biology Training Grant (T32 CA009594); E. McAuley is supported by and F31 from the NIDDK (DK111131). R. Bhanvadia is supported by a University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Fellowship and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant #2T35DK062719-27. JM Vasquez is funded by The University of Chicago PREP Program (NIH R25GM066522). The Center for Research Informatics is funded by the Biological Sciences Division at the University of Chicago with additional funding provided by the Institute for Translational Medicine NIH CTSA grant number UL1 TR000430. This work was also supported by the Department of Defense Prostate cancer Research Program, DOD Award NoW81XWH-10-2-0056 and W81XWH-10-2-0046 PCRP Prostate cancer Biorepository Network (PCBN) and the NIH/NCI prostate SPORE pathology core (Award No 5P50CA058236).

We wish to acknowledge the support of the University of Chicago Section of Urology led by Dr. Arieh Shalhav, the Department of Surgery led by Dr. Jeff Matthews, and the Ben May Institute for Cancer Research led by Dr. Geoffrey Greene. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center (UCCCC) led by Dr. Michelle Le Beau. We would also like to thank Dr. William Isaacs from the Johns Hopkins Brady Urologic Institute for his mentorship, encouragement, and guidance on the project. We also with to thank expert technical assistance of the Human Tissue Resource Center core facility led by Dr. Mark Lingen, and the assistance of Mary Jo Fekete. We also thank the Immunohistochemistry Core Facility run by Terri Li. We also thank the Center for Research Informatics analysis group led by Dr. Jorge Andrade.

Abbreviations

- ADT

Androgen Deprivation Therapy

- AR

Androgen Receptor

- BCR

Biochemical Recurrence

- CRPC

Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

- GG

Gleason Grade

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- MEIS

Myeloid Ectopic Integration Site

- PIN

Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia

- Prostate cancer

Prostate Cancer

- PSA

Prostate-Specific Antigen

- TALE

Three Amino Acid Loop Extension

- XRT

external radiation therapy

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES CITED

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paller CJ, Antonarakis ES. Management of biochemically recurrent prostate cancer after local therapy: evolving standards of care and new directions. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2013;11(1):14–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eifler JB, Feng Z, Lin BM, Partin MT, Humphreys EB, Han M, et al. An updated prostate cancer staging nomogram (Partin tables) based on cases from 2006 to 2011. BJU Int. 2013;111(1):22–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brechka H, Bhanvadia RR, VanOpstall C, Vander Griend DJ. HOXB13 mutations and binding partners in prostate development and cancer: Function, clinical significance, and future directions. Genes & Diseases. 2017;4(2):75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longobardi E, Penkov D, Mateos D, De Florian G, Torres M, Blasi F. Biochemistry of the tale transcription factors PREP, MEIS, and PBX in vertebrates. Dev Dyn. 2014;243(1):59–75. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewing CM, Ray AM, Lange EM, Zuhlke KA, Robbins CM, Tembe WD, et al. Germline mutations in HOXB13 and prostate-cancer risk. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):141–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Huang K, Guo H, Cui G. Meis1 regulates proliferation of non-small-cell lung cancer cells. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(6):850–5. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.06.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crijns AP, de Graeff P, Geerts D, Ten Hoor KA, Hollema H, van der Sluis T, et al. MEIS and PBX homeobox proteins in ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(17):2495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JL, Li J, Kiriluk KJ, Rosen AM, Paner GP, Antic T, et al. Deregulation of a Hox protein regulatory network spanning prostate cancer initiation and progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(16):4291–302. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Gronberg H, Drake CG, et al. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):256–69. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curry PT, Atherton RW. Seminal vesicles: development, secretory products, and fertility. Arch Androl. 1990;25(2):107–13. doi: 10.3109/01485019008987601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong JH, Park SJ, Dickinson SI, Luo JL. A Constitutive Intrinsic Inflammatory Signaling Circuit Composed of miR-196b, Meis2, PPP3CC, and p65 Drives Prostate Cancer Castration Resistance. Mol Cell. 2017;65(1):154–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litvinov IV, Vander Griend DJ, Xu Y, Antony L, Dalrymple SL, Isaacs JT. Low-calcium serum-free defined medium selects for growth of normal prostatic epithelial stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(17):8598–607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Antonio JM, Vander Griend DJ, Antony L, Ndikuyeze G, Dalrymple SL, Koochekpour S, et al. Loss of androgen receptor-dependent growth suppression by prostate cancer cells can occur independently from acquiring oncogenic addiction to androgen receptor signaling. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kregel S, Kiriluk KJ, Rosen AM, Cai Y, Reyes EE, Otto KB, et al. Sox2 is an androgen receptor-repressed gene that promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedelaar JP, Dalrymple SS, Isaacs JT. Of mice and men-warning: Intact versus castrated adult male mice as xenograft hosts are equivalent to hypogonadal versus abiraterone treated aging human males, respectively. Prostate. 2013;73(12):1316–25. doi: 10.1002/pros.22677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pflueger D, Terry S, Sboner A, Habegger L, Esgueva R, Lin PC, et al. Discovery of non-ETS gene fusions in human prostate cancer using next-generation RNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;21(1):56–67. doi: 10.1101/gr.110684.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161(5):1215–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Wang S, Li W. RSeQC: quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(16):2184–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(5):511–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(7):923–30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szmulewitz RZ, Chung E, Al-Ahmadie H, Daniel S, Kocherginsky M, Razmaria A, et al. Serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 expression in primary human prostate cancers. Prostate. 2012;72(2):157–64. doi: 10.1002/pros.21416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1999;281(17):1591–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandran UR, Ma C, Dhir R, Bisceglia M, Lyons-Weiler M, Liang W, et al. Gene expression profiles of prostate cancer reveal involvement of multiple molecular pathways in the metastatic process. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, et al. Integrative Clinical Genomics of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cell. 2015;162(2):454. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bessa J, Tavares MJ, Santos J, Kikuta H, Laplante M, Becker TS, et al. meis1 regulates cyclin D1 and c-myc expression, and controls the proliferation of the multipotent cells in the early developing zebrafish eye. Development. 2008;135(5):799–803. doi: 10.1242/dev.011932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han X, Guo B, Li Y, Zhu B. Tissue factor in tumor microenvironment: a systematic review. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:54. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0054-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smirnova T, Bonapace L, MacDonald G, Kondo S, Wyckoff J, Ebersbach H, et al. Serpin E2 promotes breast cancer metastasis by remodeling the tumor matrix and polarizing tumor associated macrophages. Oncotarget. 2016;7(50):82289–304. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ifon ET, Pang AL, Johnson W, Cashman K, Zimmerman S, Muralidhar S, et al. U94 alters FN1 and ANGPTL4 gene expression and inhibits tumorigenesis of prostate cancer cell line PC3. Cancer Cell Int. 2005;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shojima K, Sato A, Hanaki H, Tsujimoto I, Nakamura M, Hattori K, et al. Wnt5a promotes cancer cell invasion and proliferation by receptor-mediated endocytosis-dependent and -independent mechanisms, respectively. Scientific reports. 2015;5:8042. doi: 10.1038/srep08042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu BR, Fairey AS, Madhav A, Yang D, Li M, Groshen S, et al. AXIN2 expression predicts prostate cancer recurrence and regulates invasion and tumor growth. Prostate. 2016;76(6):597–608. doi: 10.1002/pros.23151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu T, Burdelya LG, Swiatkowski SM, Boiko AD, Howe PH, Stark GR, et al. Secreted transforming growth factor beta2 activates NF-kappaB, blocks apoptosis, and is essential for the survival of some tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(18):7112–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402048101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng L, Kyprianou N. Apoptotic regulators in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN): value in prostate cancer detection and prevention. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8(1):7–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu K, Li X, Wang J, Wang Y, Dong H, Li J. Genetic variants in RhoA and ROCK1 genes are associated with the development, progression and prognosis of prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(12):19298–309. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang C, Zhang S, Zhang Z, He J, Xu Y, Liu S. ROCK has a crucial role in regulating prostate tumor growth through interaction with c-Myc. Oncogene. 2014;33(49):5582–91. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esposito S, Russo MV, Airoldi I, Tupone MG, Sorrentino C, Barbarito G, et al. SNAI2/Slug gene is silenced in prostate cancer and regulates neuroendocrine differentiation, metastasis-suppressor and pluripotency gene expression. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):17121–34. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie Y, Liu S, Lu W, Yang Q, Williams KD, Binhazim AA, et al. Slug regulates E-cadherin repression via p19Arf in prostate tumorigenesis. Mol Oncol. 2014;8(7):1355–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Little GH, Baniwal SK, Adisetiyo H, Groshen S, Chimge NO, Kim SY, et al. Differential effects of RUNX2 on the androgen receptor in prostate cancer: synergistic stimulation of a gene set exemplified by SNAI2 and subsequent invasiveness. Cancer Res. 2014;74(10):2857–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beebe-Dimmer JL, Hathcock M, Yee C, Okoth LA, Ewing CM, Isaacs WB, et al. The HOXB13 G84E Mutation Is Associated with an Increased Risk for Prostate Cancer and Other Malignancies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(9):1366–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Storebjerg TM, Hoyer S, Kirkegaard P, Bro F, LuCamp Study G. Orntoft TF, et al. Prevalence of the HOXB13 G84E mutation in Danish men undergoing radical prostatectomy and its correlations with prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness. BJU Int. 2016;118(4):646–53. doi: 10.1111/bju.13416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui L, Li M, Feng F, Yang Y, Hang X, Cui J, et al. MEIS1 functions as a potential AR negative regulator. Exp Cell Res. 2014;328(1):58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vander Griend DJ, Litvinov IV, Isaacs JT. Conversion of androgen receptor signaling from a growth suppressor in normal prostate epithelial cells to an oncogene in prostate cancer cells involves a gain of function in c-Myc regulation. International journal of biological sciences. 2014;10(6):627–42. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Paradelo J, Lucia MS, Miller G, Troyer D, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathological T3N0M0 prostate cancer significantly reduces risk of metastases and improves survival: long-term followup of a randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2009;181(3):956–62. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolla M, van Poppel H, Tombal B, Vekemans K, Da Pozzo L, de Reijke TM, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for high-risk prostate cancer: long-term results of a randomised controlled trial (EORTC trial 22911) Lancet. 2012;380(9858):2018–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo Y, Sheng Q, Li J, Ye F, Samuels DC, Shyr Y. Large scale comparison of gene expression levels by microarrays and RNAseq using TCGA data. PloS one. 2013;8(8):e71462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Price ME, Cotton AM, Lam LL, Farre P, Emberly E, Brown CJ, et al. Additional annotation enhances potential for biologically-relevant analysis of the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2013;6(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diez-Villanueva A, Mallona I, Peinado MA. Wanderer, an interactive viewer to explore DNA methylation and gene expression data in human cancer. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2015;8:22. doi: 10.1186/s13072-015-0014-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Welsbie DS, Xu J, Chen Y, Borsu L, Scher HI, Rosen N, et al. Histone deacetylases are required for androgen receptor function in hormone-sensitive and castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):958–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Western blotting of lentivirally-infected HEK293T cells expressing expression constructs for either human MEIS1 (LV-MEIS1) or MEIS2 (LV-MEIS2). This data demonstrates that the Santa Cruz 63-T antibody, specified to react only with MEIS2, in fact recognizes both MEIS1 and MEIS2.

(B–D) Immunhistochemical staining of both MEIS1 and MEIS2 using the 63-T antibody in human prostate (B), human liver and bile duct (B, positive control), and a xenograft tumor of CWR22rV1 prostate cancer cells (C, negative control). CWR22Rv1 cells have low to undetectable MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression.

(E–F) Correlation between MEIS mRNA and protein expression using primary prostate epithelial (PrEC) and stromal cultures (PrSC). Lines were derived using protocols described in Chen et al (9).

(A) Visualization of MEIS1 (top) or MEIS2 (bottom) methylation profiles from TGCA Research Network (48), Illumina 450K array (49). Targeted gene queries were obtained via Wanderer software (50). Profile plot displays average gene-specific methylation between normal (blue marks) versus tumor (red marks) human prostate tissue. CpG islands noted in green. Methylation marks displayed artificially evenly from the TSS. Vertical axis indicates beta values for each probe. CpGs showing statistical difference between normal and tumor are indicated with an asterisk (Wilcoxon adjusted p-value < adj. pval threshold 0.001).

(B) FPKM values from publically available RNA-sequencing of LNCaP cells treated with one of three epigenetic modifying drugs (Panobinostat, SAHA or TSA) at a high or low dose for each (51). MEIS1 (purple) and MEIS2 (blue) FPKM expression shown.

(C) Western blot analysis of PrCa cell line CWR22Rv1 when treated with HDACi’s. Densitometry relative to vehicle treatment indicated above each panel.

(A) Growth curves of MEIS1 or MEIS2 single knockdown LAPC-4 cells injected subcutaneously on the flanks of castrated and testosterone implanted male nude mice compared to non-silencing controls at day 25,27 and 29 respectively, showing no difference in growth with single knockdown compared to controls.

(B) Heatmap illustrating the expression of the 47 genes identified from our GSEA Leading Edge analyses. MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression is also included.