Abstract

Background:

The goal of the Aging, Community and Health Research Unit (ACHRU) is to promote optimal aging at home for older adults with multimorbidity (≥2 chronic conditions) and to support their family/friend caregivers. This protocol paper reports the rationale and plan for this patient-oriented, cross-jurisdictional research program.

Objectives:

The objectives of the ACHRU research program are (i) to codesign integrated and person-centered interventions with older adults, family/friend caregivers, and providers; (ii) to examine the feasibility of newly designed interventions; (iii) to determine the intervention effectiveness on Triple Aim outcomes: health, patient/caregiver experience, and cost; (iv) to examine intervention context and implementation barriers and facilitators; (v) to use diverse integrated knowledge translation (IKT) strategies to engage knowledge users to support scalability and sustainability of effective interventions; and (vi) to build patient-oriented research capacity.

Design:

The research program was informed by the Knowledge-to-Action Framework and the Complexity Model. Six individual studies were conceptualized as integrated pieces of work. The results of the three initial descriptive studies will inform and be followed by three pragmatic randomized controlled trials. IKT and capacity building activities will be embedded in all six studies and tailored to the unique focus of each study.

Conclusions:

This research program will inform the development of effective and scalable person-centered interventions that are sustainable through interagency and intersectoral partnerships with community-based agencies, policy makers, and other health and social service agencies. Implementation of these interventions has the potential to transform health-care services and systems and improve the quality of life for older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers.

Trial registration:

NCT02428387 (study 4), NCT02158741 (study 5), and NCT02209285 (study 6).

Keywords: Older adults, multimorbidity, health interventions, pragmatic randomized controlled trial, home and community care

Background

As the population ages and life expectancy increases, our health-care system is increasingly challenged to address the complex care needs of older adults with multimorbidity (≥2 chronic conditions).1 By 2030, older adults will comprise 23% of the Canadian population. One in three (33%) Canadian older adults have multimorbidity, and account for 40% of health-care use.2 Older adults with multimorbidity report poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL), higher use of health services and costs, and are at higher risk for adverse events (e.g. hospitalization and falls) and depression compared to those with a single condition. These older adults use a patchwork of costly services and programs that fail to meet their unique needs.3

Health service use in this population is largely driven by the number of chronic conditions they have, not their age.2 But, the number of chronic conditions alone does not reflect the complex care needs of older adults with multimorbidity. Instead, it is the context of people’s lives that determines their health. Thus, a person-centered approach is required for this population. Person-centered care, or “the right care for the right person at the right time,”4 must be informed not only by the collection of diseases, but also by the complex interaction between individuals’ social, cultural, ethnic, economic, geographical, gender and sex needs, health goals, and priorities. The challenge in achieving person-centered care is, in part, due to the persistent focus on the delivery of acute and episodic care for single diseases, making it difficult to be person-centered for the growing number of older adults with multimorbidity.5 It is well established that chronic illness is not just about the disease but intersects with the broader social determinants of health. An estimated 75% of the factors that influence health and health outcomes lie outside the health-care system,6 but a reactive approach focused on management of chronic diseases using a biomedical lens continues to have a strong foothold in health care.5

For the past decade, transformation of the health-care system across Canada has focused on strategies to provide a wider range of services to the growing population of older adults with multimorbidity within the context of cost containment.7 Most (92%) Canadian older adults live at home in the community; aging at home optimizes older adults’ health, independence, sense of well-being, and social connectedness.8 Home and community-based services have emerged as a viable and cost-effective solution to delivering a broad range of acute, chronic, rehabilitative, long-term, and palliative care services.9 Technological advances have enabled the delivery of increasingly complex, specialized care in the home, with most Canadians preferring to receive care in the comfort and familiarity of this setting compared to institutional settings. The result is increasing pressure on home and community-based services to provide accessible, person-centered interventions that support quality of life goals of older adults with multimorbidity, so they may continue to age at home.

While home and community-based services are promising, they are predicated on the availability of a family or friend caregiver(s) (hereafter referred to as caregivers). Caregivers are like the “backbone” of these services but we really don’t know enough about supporting them and preventing their burnout/poor outcomes. Caregivers, particularly women, provide 80% of the care Canadians receive in their homes. In 2012, approximately 8.1 million Canadians provided care to a family member or friend with a long-term health condition or age-related need.10 In Canada, the indirect cost of caregiving for people with chronic conditions is estimated at CAN$25 billion (e.g. the cost of replacing informal caregiving with paid professionals).11 Although caregiving can be rewarding, it often results in poor caregiver health and increased use of health services.3,12,13 Caregiver support is a key area to be addressed in meeting the needs of patients receiving home and community-based services. Caregivers need ongoing supportive respite, information, and access to services and community resources, as well as caregiving education and training.3 Yet, little is known about the specific needs of caregivers of older adults with multimorbidity and the best ways to support them.

There is tremendous potential for person-centered interventions to improve care delivery and health outcomes for community-living older adults with multimorbidity. However, the system is poorly equipped to address complex care needs of older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers.14,15 Most health-care systems are organized within a single-condition framework creating silos across settings and sectors where older adults receive care. The result is care delivery that is often fragmented, involving primary care, secondary care specialists, and other health and social service providers who may not be communicating effectively.16 There is a clear need for integrated care for this population. Realignment of these services from silos to coordinated collaborations across providers, settings, and sectors is pivotal to providing person-centered care that supports older adults to age in place and reduces system costs. However, providers have limited guidance or evidence as to how to approach care decisions for such patients.17 Interventions for older adults with multimorbidity based on a single-condition paradigm may be impractical or harmful.18,19 Moreover, there is limited follow-up care and a lack of attention to broader social determinants of health (e.g. income and social connectedness) and the unique needs of diverse populations which impact access to care. Although many chronic diseases have a common basis that is preventable or manageable by lifestyle changes, most interventions happen at a tertiary prevention level, focusing on illness, and largely ignore health promotion and secondary prevention.20

New and innovative models of care, incorporating solutions to these barriers, are urgently needed to support older adults with multimorbidity to age at home, support caregivers, and reduce system costs. However, we have limited evidence on how to best deliver home and community-based services to improve quality of life and health outcomes in older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers.21 The evidence base for managing chronic conditions is based largely on trials that have (i) excluded older adults with multimorbidity, (ii) tested interventions for single conditions that have not addressed mental health, and/or (iii) used designs that neglect the presence of contextual factors. To whom, then, are the results generalizable? Meaningful research on multimorbidity requires a shift from a reductionist single-condition paradigm to a model that embraces complexity and considers the complex interaction of multimorbidity with the broader determinants of health (e.g. social, economic, and environmental) and health-care system factors.22

Studies are needed to identify and confirm contextual factors that impact health outcomes and health service use in older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers.23 Identifying contextual factors that mediate poor outcomes will inform the development of targeted interventions for this complex and heterogeneous population. There is also a need to develop new approaches that (i) evaluate the effectiveness of interventions from the patient’s perspective, (ii) consider interactions between contextual factors and impact of interventions tailored to unique patient needs, and (iii) examine implementation of interventions across a range of community-based settings to ensure that the “basket of services” offered can be tailored to address patient/caregiver goals and priorities. Implementation and scale-up of these interventions will require a longer term vision, shifting from a provider-centered to a person-centered system, and an understanding of how to move this agenda forward within the context of heath-care systems’ constraints.5 This also includes selecting patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), patient-reported experience measures (PREMs), caregiver-reported outcome measures (CROMs), and caregiver-reported experience measures (CREMs) to evaluate the interventions.

The Aging, Community and Health Research Unit

The Aging, Community and Health Research Unit (ACHRU; https://achru.mcmaster.ca) was established to address these gaps in research and service delivery. ACHRU is a patient-oriented, pan-Canadian research program. It is predominantly an Ontario–Alberta partnership with coinvestigators from three additional Canadian provinces (Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, and Nova Scotia). Initial funding for the establishment of ACHRU was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Signature Initiative in Community-Based Primary Health Care and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC), Health System Research Fund, Canada. The goal of the ACHRU research program is to codesign, implement, and evaluate innovative community-based interventions, and to assess the potential for scale-up of these interventions to improve Triple Aim outcomes (health outcomes, patient/caregiver experience, and cost)24 for older adults with multimorbidity and their family caregivers. The ACHRU research program is providing the evidence base to transform the health-care system from single disease-centered care to holistic or coordinated care. The research unit combines the research and clinical expertise of over 50 interprofessional researchers from seven universities across Canada. The unit also consists of over 100 stakeholders (patients, caregivers, providers, decision-makers, and policy makers) from over 40 communities across Canada, who are helping to codesign, locally adapt, implement, and scale-up effective interventions across a variety of health settings and communities.

This program of research is focused on older adults (>65 years) with a constellation of chronic conditions focusing specifically on three vascular or vascular-related diseases: stroke, dementia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Vascular diseases are conditions affecting the circulatory system and include many of the most prevalent chronic conditions and causes of mortality worldwide. Cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease, stroke, and other cardiovascular conditions, is one of the leading causes of hospitalization in Canada and is ranked second next to cancer in terms of Canadian deaths.25 Globally, cardiovascular diseases accounted for over 17 million deaths in 2015 representing 31% of deaths worldwide.26 Two of the top three conditions in Canadian older adults are vascular conditions (high blood pressure, 47%; heart disease, 19%) and the third is a major risk factor for vascular disease (diabetes, 7%).27 Vascular disease has been recognized as a priority health concern by international organizations and many countries. Within Canada, efforts are underway to develop integrated, patient-centered services to reduce the incidence and consequences of vascular disease. These initiatives are aimed at enhancing primary and secondary prevention, disease management in primary care, and empowering patients for self-management.27 Multimorbidity is common among older adults with vascular disease, such as stroke, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. There is tremendous potential to improve the care experience and health outcomes for older adults experiencing these conditions in the context of multimorbidity.

Objectives

This protocol paper provides the rationale and plan for the ACHRU program of research, including a brief description of its initial six studies. Unlike traditional protocols focused on single studies, this protocol paper describes six interlinked studies and the underlying models and frameworks from which those studies arose. While 13 ACHRU studies comprise the repertoire of ACHRU’s current program of research, only the initial six studies are reported here. The overall objectives of the research program are (i) to codesign innovative person-centered interventions with older adults, caregivers, and providers, (ii) to examine the feasibility of the newly designed interventions, as perceived by older adults, caregivers, and providers, (iii) to determine the effectiveness of these new interventions, compared to usual care, on Triple Aim outcomes: health outcomes, patient/caregiver experience, and cost,24 (iv) to examine intervention context and identify implementation barriers and facilitators, (v) to use diverse integrated knowledge translation (IKT) strategies to engage knowledge users (KUs) and support scalability and sustainability of effective interventions, and (vi) to build patient-oriented research capacity among patients, decision-makers, policy makers, and researchers.

Methods

This protocol paper will first provide a summary of ACHRU’s approach in terms of frameworks, models, and study designs. The Complexity Model and the Knowledge-to-Action Framework will provide the overarching frameworks for the program of research. Next, we will provide a brief description of the initial six interlinked studies which established ACHRU’s program of research. The description of the three trials (studies 4, 5, and 6) follows the SPIRIT guidelines,28 which were customized for publishing a program of research. Additional details of the methods are shown in the Online Supplemental File 1.

Ethics

Ethics approval has been obtained from the following Research Ethics Boards: study 1: Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#13-411), University of Alberta (#39559); study 2: McMaster University and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (#13-394-C); study 3: McMaster University (#2013 104), University of Alberta (#Pro00039895); study 4: Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#15-309), University of Alberta (#Pro00048721); study 5: Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#14-486); study 6: Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#14-542).

Complexity framework

While published after the inception of the ACHRU research program, the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Complexity Model is currently the overarching framework that guides the ACHRU research program. In this model, complexity is defined as “the misalignment or gap between individual needs and the health care system’s capacity to meet those needs.”22 The size of the “needs-services gap” is related to individual needs, system capacity, and the interaction between them, which is influenced by multiple interacting contextual factors (e.g. social determinants of health, health-care systems and policies, economic, and physical factors). It emphasizes the interconnectedness of medical and nonmedical factors (e.g. social determinants of health), and health-care policies that create economic incentives or disincentives. The model depicts a complex adaptive system—a collection of factors that influence patient needs and service delivery that act in ways that are not always predictable, and are interconnected so that presence of one factor changes the context for another.29

The consideration of contextual factors in the Complexity Model offers a systematic and holistic perspective with which to understand the problem of multimorbidity in older adults while at the same time placing the nature of the “needs-services” gap at the forefront of possible solutions.22 This, in turn, informs the design, implementation, and evaluation of interventions in our research program. Defining multimorbidity in the context of complexity implies that for older adults with multimorbidity, the prevention and management of multimorbidity is not just about the disease, but intersects with the broader social/economic/physical and health-care systems and policy context.30 For example, poverty and social isolation are key risk factors for chronic conditions, and health inequities are closely related to health status and well-being. This approach addresses the gap in current conceptualizations of multimorbidity in older adults in the literature which focus predominantly on the biomedical dimensions of multimorbidity, with limited consideration for the broader social determinants of health.31 Social determinants of health are responsible for most health inequalities. A well-established evidence base supports the substantial effect of nonmedical factors (e.g. education, social support, and income) on overall physical and mental health.32

ACHRU research studies

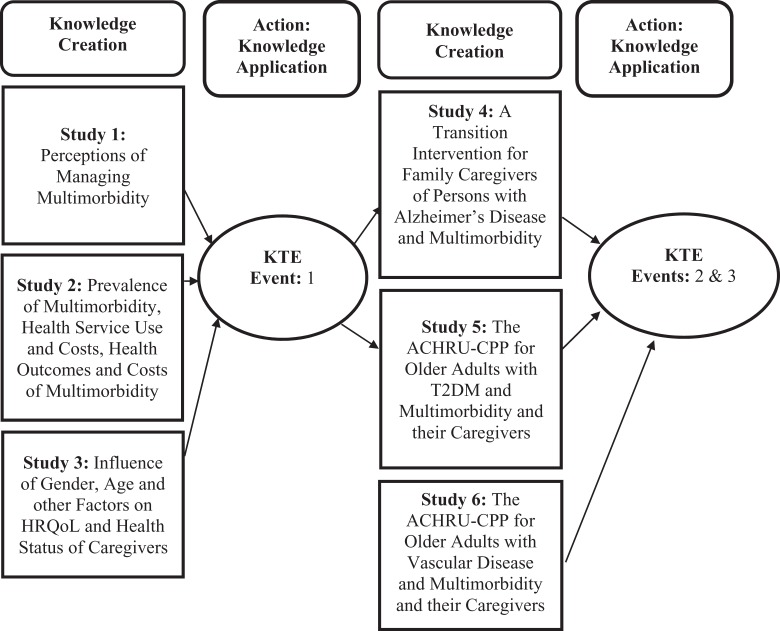

The Knowledge-to-Action Framework33 will provide the framework for the program of research, where six individual studies will be conceptualized as integrated pieces of work that will inform the overall research program. The three initial descriptive studies will be designed to inform ACHRU’s program of research in terms of describing and explaining multimorbidity, caregivers of persons with multimorbidity, and person-centered interventions in the context of multimorbidity. Taken together, the results of these three initial studies will be integrated to achieve “knowledge creation.” The synthesis of these initial three studies will inform and be followed by three pragmatic randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Once again, the results of the RCT studies will be integrated and synthesized to achieve another phase of “knowledge creation.” Numerous IKT strategies, including three IKT events, will be employed to broadly disseminate the findings from the six interlinked studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ACHRU research program of six interlinked studies. ACHRU: Aging, Community and Health Research Unit.

ACHRU initial descriptive studies

The following is a description of the objectives, study design, populations, and evaluation/outcomes of the initial three studies (non-trials) as part of the ACHRU research program.

Study 1: Perceptions of managing multimorbidity

Objectives

To better understand the experiences of older adults with multimorbidity, in terms of (i) how they manage their multimorbidity and goals, (ii) care preferences, and (iii) the challenges and experiences of the caregivers and providers who support older adults with multimorbidity.

Study design and populations

Two-province (Ontario and Alberta) qualitative interpretive descriptive study.34 Individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews will be conducted with three groups of study participants (40 per group) in each province: older adults, caregivers, and community health-care providers. Criterion and maximum variation sampling will be used to ensure that there will be diversity among older adults in relation to age, sex, gender, and chronic conditions. Sampling will end at data saturation. Interview transcripts will be analyzed and coded using Thorne et al.’s (2016) interpretive descriptive approach.34 Transcripts will be coded by two researchers with the goal of identifying recurring, converging, and opposing themes.

Evaluation/outcomes

Cross-jurisdictional comparisons will be performed across the two participating provinces to examine similarities and differences in identified themes.

Study 2: Prevalence of multimorbidity, health service use, and associated costs

Objectives

To describe comorbidity, health services utilization, and associated costs among older adults with multimorbidity. This study will provide the context for the condition-specific interventions that will be tested in the program of research, as well as will provide insights into the patterns and costs of health service use among older adults with multimorbidity.

Study design and populations

A population-based retrospective cohort study using administrative databases from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Ontario, Canada. Study participants will be community-living older adults (≥65 years), living in Ontario, with a diagnosis of either dementia, diabetes, or chronic stroke.

Evaluation/outcomes

Descriptive analysis, including the 5-year health service use of physician visits, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and home care services. Unit costs for each service will be applied to service use data costs.35

Study 3: Influence of gender, age, and other factors on quality of life and health status of caregivers of older adults with multimorbidity

Objectives

To describe the association between social factors (e.g. sex, gender, age, education, income, employment status, culture, gender, geography, and social connectedness), burden, and quality of life of caregivers of older adults with multimorbidity.

Study design and populations

A repeated-measures embedded mixed-methods intersectionality study. Intersectionality is a theoretical framework informed by critical feminist philosophy to understand the complexities of individual health needs and outcomes.36 The study sample will consist of 194 caregivers of older adults with multimorbidity. Quantitative data will be collected via telephone or face-to-face interviews. Data on caregivers’ use of different types of formal health and social services will be assessed at baseline and again at 6 months.

Evaluation/outcomes

Outcome measures include HRQoL (Short Form-12v2 (SF-12v2)),37 self-efficacy (General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)),38 caregiver burden (12-item short-form Zarit Burden Inventory),39 and the Bem Sex Role Inventory, a work interferences scale.40 The primary analysis will examine the association between age, sex, gender, employment status, and social intrusion with caregiver burden.

ACHRU pragmatic RCTs and their interventions

The trials will be designed as two-arm, pragmatic, mixed-method RCTs. All trials will use a type 2 hybrid design, which allows researchers to study clinical effectiveness (e.g. Does the intervention work?) and implementation (e.g. Is the intervention delivery feasible and acceptable?) simultaneously.41 Hybrid designs help facilitate the transition from research to practice, thereby resulting in more rapid uptake of effective interventions.41 The trials will address the following common research objectives, which will facilitate comparisons across studies and generate lessons learned:

To study the effects of the intervention compared with usual care on community-living older adults’ health outcomes.

To determine the subgroups of older adults that benefit most from the interventions.

To study the effects of the intervention compared with usual care on family caregivers’ health outcomes.

To explore the implementation of the intervention.

To determine the costs of use of health and social services associated with the interventions compared with usual care, from a societal perspective.

The trials will address common research objectives that collectively capture the five RE-AIM framework domains (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance).42 This framework enhances the translation of research into practice and improves sustainable adoption of effective, evidence-based interventions,42 making it an excellent structural guide for these RCTs.

The description of the three trials below (studies 4, 5, and 6) follows the SPIRIT guidelines for reporting protocols of intervention trials.28

Study 4: A Web-based psychoeducational intervention (My Tools 4 Care) for caregivers of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia and multimorbidity

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness and implementation of a Web-based intervention, “My Tools 4 Care” on the quality of life of caregivers.

Trial design

Multisite, pragmatic, mixed-methods RCT, with participants randomized to either treatment (My Tools 4 Care (MT4C)) or an educational control group.

Study setting

Two Canadian provinces (Ontario and Alberta).

Eligibility criteria

Family and friend caregivers (≥18 years) of community-living older adults (≥65 years) with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementia and two or more chronic conditions. Caregivers are English-speaking and have an e-mail address and access to a computer with Internet.

Interventions

MT4C is an interactive, self-administered, Web-based, and portable tool kit containing six main sections to educate and support caregivers with their transitions in care, and based on theoretical transitions theory.43 The trial’s intervention is based on a pilot study, where its feasibility and preliminary effectiveness was demonstrated in one region in Alberta.44 The intervention group will receive instructions and 3 months access to the tool kit. The educational control group will receive a copy of the Alzheimer’s Society’s The Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease—Overview Booklet.

Outcomes

The primary measure of effectiveness will be the change in mental health functioning (Short Form-12, Mental Component Summary (SF-12v2 MCS))37 from baseline to 1, 3, and 6 months. Secondary outcomes will include changes in (i) hope (Herth Hope Index),44 (ii) physical functioning (Short Form-12, Physical Component Summary (SF-12v2 PCS)),37 (iii) self-efficacy (GSES),38 and (iv) costs of use of health services, from a societal perspective (Health and Social Services Inventory (HSSUI))45 from baseline to 1, 3, and 6 months. Implementation will be examined at 3 months using semi-structured telephone interviews. Implementation outcomes will include (i) perceptions of the impact of MT4C, (ii) experiences using the intervention, for example, barriers and facilitators to the use of MT4C, and (iii) recommendations regarding adaptations required to enhance the reach, adoption, and sustainability of the MT4C intervention.

Sample size

Two hundred participants.

Recruitment

Caregivers will be recruited through Alzheimer Societies in Alberta and Ontario and through other venues such as newspaper advertisements and support groups.

Assignment of interventions

Participants will be randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to either the intervention or control group using a centralized Web-based randomization service (REDCap).

Blinding

Participants and data analysts will be blinded to group allocation.

Data collection

Survey data will be collected by trained research assistants by telephone at baseline, 1, 3, and 6 months. Data will be recorded electronically using e-fillable surveys accessible through REDCap.

Data analysis

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) will be used to identify group differences at 3 months and generalized estimating equations will be used to identify group differences over time. Subgroup analyses will be performed to determine whether there are differences in the effectiveness of the intervention for the primary outcome. The following subgroups will be examined: age, sex, caregiver employment status, number of caregiver chronic conditions, number of care recipient chronic conditions, and income.

Study 5: The ACHRU-Community Partnership Program for older adults with T2DM and multimorbidity and their caregivers

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness and implementation of the ACHRU-Community Partnership Program (ACHRU-CPP) on self-management and quality of life of older adults with T2DM and multimorbidity and their caregivers.

Trial design

Multisite, pragmatic, mixed-methods RCT with participants randomized to either treatment (ACHRU-CPP) or usual care.

Study setting

Two Canadian provinces (Ontario and Alberta).

Eligibility criteria

Community-living older adults (≥65 years) with T2DM and two or more chronic conditions, English-speaking or have an interpreter, and mentally competent or have a family or friend caregiver who can provide consent on their behalf.

Interventions

The ACHRU-CPP is a 6-month multifaceted, evidence-informed intervention, codeveloped with patients, caregivers, and providers, and based on social cognitive theory.46 It was designed to integrate care across settings to promote self-management in older adults (≥65 years) with T2DM and multimorbidity and improve the quality of care and health outcomes in this population. Core components of the program will include (i) nurse-led care coordination and system navigation, (ii) home visits by certified diabetes educators from Diabetes Education Centers (DECs)/Diabetes Education Programs (DEPs) involving Registered Nurses and Registered Dietitians in Ontario and through the Primary Care Networks (PCNs) in Alberta, (iii) monthly community-based group sessions, jointly hosted by a community partner (e.g. YMCA) and a DEC/DEP or PCN, (iv) monthly case conferences for the intervention team, and (v) trained peer support. The fundamental principles underlying the components of this patient-driven intervention are motivational interviewing47 to encourage self-management and self-efficacy, collaboration, holistic care, and caregiver engagement and support. The patient will be a key member of the care team and is fully engaged in the development of the care plan that is tailored to their individual needs and preferences. The trial’s intervention is based on a pilot study, where its feasibility and preliminary effects were demonstrated in one region in Ontario.48

Outcomes

The primary measure of effectiveness will be the change in physical functioning (SF-12v2 PCS),37 from baseline to 6 months. Secondary measures of effectiveness include changes in (i) patient outcomes: mental health functioning (SF-12v2 MCS),37 summary of diabetes self-care activities,49 depressive symptoms (Centre for Epidemiological Studies in Depression Scale (CES-D-10)),50 anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7))51 and self-efficacy (GSES)38; (ii) family caregiver outcomes: depressive symptoms (CES-D-10),50 physical and mental health functioning (SF-12v2 PCS and MCS),37 burden associated with caregiving (Modified Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI)),52 and (iii) the costs of use of health services, from a societal perspective from baseline to 6 months (HSSUI).45

Implementation outcomes will be examined and include acceptability, appropriateness, adoption, feasibility, fidelity, reach (coverage), maintenance (sustainability), and cost.53 Acceptability and adoption will be assessed using the enrollment, attrition, engagement rates (percentage of study participants receiving at least one home visit and attending at least one group session), and dose of the intervention. Targets have been set for each of these measures based on the literature and/or our pilot study results. Results from this study will be compared with our prior RCT. Similar measures will be used to examine maintenance (sustainability). Reach (coverage) will be assessed by reviewing baseline demographic characteristics of the total sample and comparing these data to the broader population of older adults with T2DM and multimorbidity in the study regions. Appropriateness and feasibility will be evaluated based on the qualitative data collected at monthly outreach meetings and focus group sessions with interventionists. Data collected from focus group sessions will be guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)54 framework. The CFIR tool facilitates the systematic exploration and summary of the barriers and facilitators to implementing health programs and interventions. Specifically, data collected will inform the following key domains: (i) intervention characteristics (e.g. complexity of intervention, perceptions of benefits, and relative advantage compared to usual practice), (ii) outer setting (e.g. credibility of the intervention by provider and senior administrative agents), (iii) inner setting (e.g. team characteristics and engagement, level of coordination and collaboration, involvement of patients and caregivers, and compatibility with existing systems and resources), and (iv) individuals (e.g. enthusiasm and support for intervention, consistent tracking of activities, reporting and resolving challenges, and robust referrals). Fidelity will be assessed through conducting regular audits of the study-related documentation.

Sample size

Three hundred and twenty participants.

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited through DECs in Ontario and Alberta.

Assignment of interventions

Participants will be randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to either the intervention or control group using a centralized Web-based randomization service (REDCap).

Blinding

Outcome assessors and data analysts will be blinded to group allocation.

Data collection

Survey data will be collected by trained research assistants through in-home interviews at baseline and 6 months (post-intervention). Data will be recorded electronically using LimeSurvey Version 2.73.1+171220.

Data analysis

ANCOVA will be used to identify group differences at 6 months and generalized estimating equations will be used to identify group differences over time. Subgroup analysis will be performed to determine whether there will be a difference in the effectiveness of the intervention for the primary outcome. The following subgroups will be examined: age, sex, gender, duration of diabetes, depressive symptoms, number of comorbidities, self-efficacy, and caregiver support.

Study 6: The ACHRU-CPP for older adults with vascular disease and multimorbidity and their caregivers

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness and implementation of the ACHRU on quality of life of older adults with vascular disease and multimorbidity using home care services and their caregivers.

Trial design

Single-site, pragmatic, mixed-methods RCT, with participants randomized to either treatment (ACHRU-CPP) or usual home care.

Study setting

Two Canadian provinces (Ontario and Alberta).

Eligibility criteria

Older adults (≥65 years) with vascular conditions and two or more chronic conditions, English-speaking or have an interpreter, and mentally competent or have a family or friend caregiver who can provide consent on their behalf.

Interventions

The ACHRU-CPP is a 6-month multifaceted, evidence-informed intervention, codeveloped with patients, caregivers, and providers, and based on social cognitive theory.46 The intervention was designed to integrate home care services to promote self-management in older adults (≥65 years) with vascular conditions and multimorbidity and their caregivers and improve the quality of care and health outcomes in this population. Core components of the program will include (i) nurse-led care coordination and system navigation, (ii) home visits by an interprofessional home care team (Care Coordinators, Registered Nurses, Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, and Personal Support Workers), and (iii) monthly case conferences for the intervention team. The fundamental principles underlying the components of this patient-driven intervention are strengths-based practice55 to encourage self-management and self-efficacy, collaboration, holistic care, and caregiver engagement and support. The patient is a key member of the care team and is fully engaged in the development of a care plan that is tailored to their individual needs and preferences. The trial’s intervention is based on a pilot study, where its feasibility and preliminary effects were demonstrated in one region in Ontario.56

Outcomes

The primary measure of effectiveness will be the change in physical functioning (SF-12v2 PCS)37 from baseline to 6 months. Secondary outcomes will include (i) patient outcomes: mental health functioning (SF-12v2 MCS),37 depressive symptoms (CES-D-10),50 anxiety (GAD-7),51 (ii) family caregiver outcomes: depressive symptoms (CES-D-10),50 physical and mental health functioning (SF-12v2 PCS and MCS),37 caregiver burden (MCSI),52 and (iii) the costs of use of health services, from a societal perspective (HSSUI).35 Secondary outcomes will be examined as 6-month change from baseline. Implementation outcomes will be assessed using the same approach as in study 5.

Sample size

Sixty participants.

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited through a single home care program in Ontario.

Assignment of interventions

Participants will be randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to either the intervention or control group using a centralized Web-based randomization service (REDCap).

Blinding

Outcome assessors and data analysts will be blinded to group allocation.

Data collection

Survey data will be collected by trained research assistants through in-home interviews at baseline and 6 months (post-intervention). Data will be recorded electronically using LimeSurvey.

Data analysis

ANCOVA will be used to identify group differences at 6 months and generalized estimating equations will be used to identify group differences over time. Subgroup analysis will be performed to determine whether there will be differences in the effectiveness of the intervention for the primary outcome. The following subgroups will be examined: age, sex, gender, depressive symptoms, number of comorbidities, self-efficacy, and caregiver support.

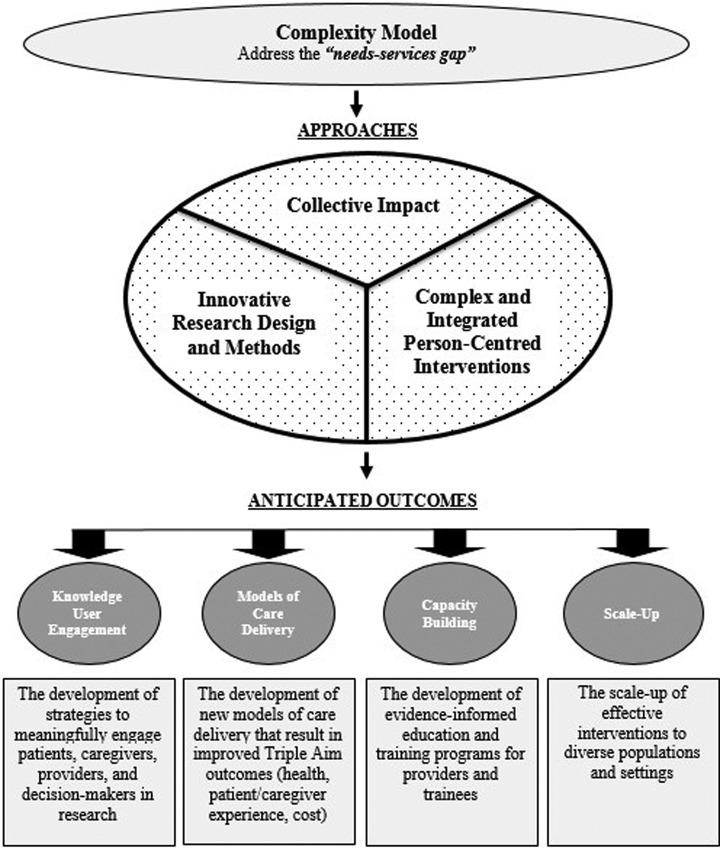

Key principles guiding the ACHRU research program

The guiding framework for the ACHRU program of research is consistent with the Complexity Model and consists of the following key principles: (i) the need for a collective impact approach,57 (ii) the need for complex and person-centered interventions, and (iii) the need for innovative research designs and methods (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Guiding framework for ACHRU program of research. ACHRU: Aging, Community and Health Research Unit.

Collective impact approach

The first key principle that underpins the ACHRU research program is the need for a collective impact approach.57 Consistent with the Complexity Model, interprofessional and intersectoral collaboration and partnerships are needed to narrow the “needs-services gap” to improve the health of patients with multimorbidity. This includes a shift in focus from studies that focus on single settings, sectors, and providers to studies that involve collaborations among community and other health-care agencies that are involved in providing care to older adults with multimorbidity. This approach enhances and creates opportunities across many already existing, but perhaps underutilized health-based and community services/sectors and fosters sustainability and scale-up. This approach is premised on the belief that no single sector, organization, or provider alone can address the complexity associated with the needs of older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers.

To address patients with complex needs due to having more than one chronic condition, the collective impact approach purports that what is essential is a shared responsibility between patients, caregivers, and community-based health and social service organizations to ultimately improve the health of older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers. To this end, a requirement is to partner with many cross-sectorial organizations, institutions, and associations and reach beyond the traditional acute health-care system to address the spectrum of medical and nonmedical needs affecting the health of this complex patient population and their caregivers. The collective impact approach includes five key elements: (i) a shared vision of the problem and intervention, (ii) agreement on evaluation measures, (iii) open, ongoing communication, (iv) clear roles and responsibilities coordinated through a mutually reinforcing plan, and (v) “backbone support.”57 Unlike simple collaboration or partnership, a collective impact approach has centralized infrastructures or “backbone organizations” with the aim to coordinate a concerted effort57 to improve health. In our research program, project funds will provide the initial “backbone support.” Sustaining “backbone support” beyond the initial research trials will need to be established with selected partners to facilitate scaling-up of effective interventions.

Complex and integrated person-centered interventions

To address the complex health and social needs of older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers, the second key principle guiding our research program is the need for health-care interventions that are complex, integrated, and person-centered. The consideration of individual preferences and expectations is central to the concept of “complexity.”19 Accordingly, the design and evaluation of interventions needs to be person-centered.5 Person-centered care involves considering older adults’ needs, desires, and goals within the broader context in which they live, and seeing the person as an individual and working in partnership to develop an appropriate plan of care.5 Person-centered approaches are particularly critical for older adults with multimorbidity given the high level of disease burden, the uncertainty regarding their care trajectory, and the need for goal-based care to address the multiple treatment decisions that they face.5 Making sure that people are involved in and central to their care is now recognized as a key component of developing high-quality health care. There is accumulating evidence for the effectiveness of person-centered care in improving people’s health and reducing the burden on health services.5

ACHRU interventions are aimed at reducing adverse health outcomes and increasing beneficial health outcomes by testing intervention effectiveness in sound methodological pragmatic clinical trials. Additionally, ACHRU interventions contribute to (i) primary prevention and the reduction of new chronic diseases, through improved self-management of lifestyle behaviors predictive of chronic diseases, such as diet and physical activity; and (ii) secondary prevention and the reduction of chronic disease progression, through improved disease management and control of established risk factors. Interventions are developed using the guidelines for developing complex interventions by the Medical Research Council in the United Kingdom.58

Innovative research designs and methods

Consistent with the Complexity Model, the third key principle in our research program is the need for innovative research designs and methods to better study the effectiveness and implementation of complex, community-based interventions and complex patients and their caregivers. Existing research does not always capture the complexity and context of community-living older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers. Addressing complex research questions necessitates the use of innovative research approaches, such as pragmatic trials and mixed-methods research designs, and requires the ability to decipher interactions among the many contextual factors that influence both the needs of older adults with multimorbidity (e.g. differing values/preferences) and the ability of the system to meet those needs (e.g. health-care systems and policies and social/economic/physical factors).

The three intervention studies (studies 4, 5, and 6) are designed to be pragmatic RCTs. ACHRU trials are pragmatic in that they will be undertaken in a “real world” practice setting where participants may be receiving other health and social services. The aim of a pragmatic trial will be to determine if the intervention works when used in normal practice,59 and to inform implementation feasibility as it relates to potential policy and sustainable practice change. ACHRU uses the Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary-2 tool60 in designing pragmatic trials, which is a tool to help researchers align trial design features with pragmatic aims. The goal is (i) to maximize the applicability of the intervention to current health-care practices, (ii) to recruit trial participants with minimal selection criteria so that are highly representative of the “general” population for which the intervention is intended, and (iii) to deliver the intervention under real-world circumstances and limitations, including the use of existing providers.60

Some of the key pragmatic features used in ACHRU trials include (i) identifying eligible participants identified from existing site registries and electronic medical records of patients receiving usual care, and applying minimal exclusion criteria to ensure that participants mirror the heterogeneous patient mix seen in practice; (ii) selecting study sites from multiple settings across Ontario and Alberta, thereby ensuring that study participants have a diverse range of sociodemographic characteristics and enhancing the generalizability of trial results; (iii) delivering interventions at community-based sites or through community organizations identical to those for which the intervention is intended; (iv) delivery of interventions by existing health-care and community-based providers; (v) tailoring interventions to individual patient needs with details left up to the patient, working in collaboration with providers; (vi) allowing patient preference to dictate intervention engagement; (vii) employing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), such as HRQoL because of its patient-relevance, and other outcomes such as service cost required for policy-relevance; and (viii) employing intention-to-treat analyses with multiple imputation for missing data to analyze participants in the groups in which they were randomized despite loss to follow-up.

The pragmatic trials conducted at ACHRU are effectiveness–implementation type 2 hybrid designs,41 where equal emphasis is placed on testing the effectiveness of the intervention and studying its implementation. The effectiveness research component is comparative effectiveness research (CER), which emphasizes pragmatic features that directly inform clinical and/or policy decisions, comparing the intervention to usual care, employing patient-relevant outcome measures, and conducting the trial in similar settings to those for which the intervention is intended.61 Despite agreement on the goals of CER, CER trials vary considerably in the degree to which they are integrated into normal practice.62 We aim to minimize the intrusion of research in practice by designing highly pragmatic RCTs, which is a key method used to achieve CER goals.61

Common effectiveness outcomes are used in all intervention studies to allow cross-study comparisons and generate lessons learned. Key outcomes in the effectiveness evaluation align with Triple Aim outcomes—achievement of better health outcomes, improving patient and caregiver experience, and reducing costs.24 Simultaneous pursuit of these outcomes is widely accepted as a compass to optimize health system performance.63 Patient- and caregiver-reported outcome measures (i.e. PROMs, PREMs, CROMs, and CREMs) are included in all studies. PROMS are measured using reliable and valid surveys administered by trained research assistants during in-home interviews or telephone interviews. Subgroup analyses to determine which groups of older adults benefit most from the interventions are conducted; informed by the AHRQ multimorbidity framework applied to the specific intervention and population that it targets, for example, sex and gender, cross-jurisdictional. In ACHRU pragmatic RCTs, the control group represents usual care (i.e. existing health services for which older adult participants would already be eligible). Because usual care differs by site, we will carefully document what constitutes usual care at each site to appropriately implement/integrate the interventions and ensure a meaningful comparison of usual care with the interventions.

The implementation research component is an action-oriented formative evaluation to allow the trial to adapt in real time to new information arising during implementation. This involves two components: (i) exploring what influences implementation and (ii) evaluating implementation outcomes.64 We are using a variety of implementation theories and frameworks to evaluate the context for implementation of the interventions.64 The process (determinants) of implementation is explored using the CFIR.54 Implementation of the interventions is also explored using normalization process theory65 which examines the process of making practices routine elements of everyday life (embedding) and of sustaining embedded practices in social contexts (integration). Patient/caregiver interviews, researcher-implementation team meeting minutes, and provider focus groups are used to capture this information. These data will enhance understanding of “real-world” implementation of the intervention and identify effective, context-specific implementation strategies to enhance the integration of interventions into usual care practice.

Common implementation outcomes are also used in all intervention studies to allow cross-study comparisons and generate lessons learned. Consistent with the RE-AIM framework,42 the success of the interventions is determined by an assessment of the following implementation outcomes: acceptability (satisfaction with various aspects of the innovation), adoption (uptake, utilization), appropriateness (perceived fit, relevance), feasibility (suitability for everyday use from the perspective of patients and providers and/or managers), fidelity (core components of intervention and implementation delivered as intended), cost (comparative cost analysis), effectiveness, coverage (reach), and sustainability (maintenance).53 Quantitative (e.g. surveys, administrative data, and checklists) and qualitative (e.g. focus groups and semi-structured interviews) methods are used to capture this information.

ACHRU capacity building strategies

The overarching and supporting goal of ACHRU is to develop a cadre of researchers, patients, caregivers, and decision-makers who will be leaders and mentors in patient-oriented research and innovative research methods. ACHRU’s capacity building initiative is designed to support training and career development in these areas for trainees, including postdoctoral fellows, undergraduate and graduate students, new investigators, research staff, home and community care providers, and the broader research team; they, together with new investigators, are integrated into all aspects of the research program. A capacity building initiative was developed that is led by cross-provincial trainees, and involves regular training opportunities, educational resources, bimonthly seminars, and research support and mentoring. Trainees acquire hands-on experience in protocol development, intervention design and implementation, training of intervention personnel, data collection and analyses, and report writing. Trainees also receive training and mentorship in health interventions; health services research; research with older adults with multimorbidity and their family caregivers; quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods; pragmatic RCTs; analysis of secondary databases; sex- and gender-based analysis; working within a multidisciplinary research team; policy perspectives on community-based health services research; and IKT. They have opportunities to collect and analyze data, write reports, present results at conferences, and publish papers.

Trainees will be provided with opportunities to participate in conferences, coauthor publications in peer-reviewed journals, and attend research team and community stakeholder meetings. PhD and master’s students’ thesis work are embedded within ongoing research projects to highlight pragmatic issues and narrow the research-to-practice gap. New investigators will have active roles in studies (study leads and coinvestigators) and receive research training and mentorship by more senior investigators. Service providers receive initial and ongoing training and mentorship to deliver the interventions in the RCTs. Trainees will also collaborate with stakeholders, which will increase the visibility of the trainees and allow them to build broad professional networks with senior researchers, policy makers, and home and community care senior managers/directors. This training will enable trainees to secure excellent postdoctoral and faculty positions in universities, government, hospital, and community settings in Canada and abroad. The IKT events provide capacity-building opportunities for all attendees (trainees, researchers, KUs, and service providers). These IKT events provide research training on topics such as pragmatic RCTs, developing theory-informed interventions and health intervention research with older adults.

ACHRU engagement and knowledge translation strategies

Our plan for engagement with KUs is guided by the Knowledge-to-Action Framework.33 A key strength of this program is in its IKT strategies that, from its inception, involve the engagement of KUs (patients, caregivers, providers, researchers, and trainees) in all stages of the research.66 These stakeholder groups have been engaged since the beginning with identifying research priorities, through to developing projects to address these priorities. The partners in this research program continue to work collaboratively throughout the IKT process to design, implement, and evaluate the interventions (i.e. knowledge creation),33 and plan IKT strategies to ensure uptake of effective interventions into community-based care (i.e. action).

It is crucial that ACHRU research results are properly translated and understood by KUs (e.g. practitioners and decision-makers). This entails not only giving results visibility but also rendering them digestible and comprehensible. IKT occurs using a combination of effective methods of dissemination throughout the research program tailored to different intended KUs including the media and the public. The methods of dissemination will include executive summaries, research briefs, videos, interactive small group meetings or teleconferences, policy forums, citizen panels, invited presentations at relevant networking groups, educational outreach, open-access publications and scientific conferences. Within our KUs and partner networks, we will use existing communication channels (e.g. newsletters and websites) to disseminate the findings. A website was developed for the research program (https://achru.mcmaster.ca/) to post brief video overviews of the studies, as well as background information, research activities, and research findings to promote broad dissemination across Canada.

As part of our work to date in the ACHRU research program, three IKT events will be held which included interactive small groups and interprofessional collaboration focusing on three areas: (i) sharing evidence generated by the research program, (ii) gaining policy perspectives on the evidence and current context of community health care, and (iii) providing capacity building opportunities. These events will target key stakeholders, including KUs and policy makers, health system decision-makers and collaborators, patient and caregiver research partners, researchers, and trainees. KUs will play key roles in the IKT events, sharing their perspectives on study findings, implications for policy and practice, and identifying strategies for scaling-up effective interventions. Final reports of each IKT event will be prepared and disseminated widely to key stakeholders to impact clinical practice and policy and support future action.

As part of the ACHRU program of research, each individual study team will engage in the development of an IKT plan, which will be rolled up into an overall IKT plan for the research unit. A logic model will be used to develop this plan and address each stakeholder group to understand the performance and impact of the IKT activities.67 We will track key IKT activities, such as numbers of presentations, publications, media interviews, stakeholder meeting attendance, Web analytics, and statistics for other social media (i.e. Facebook and Twitter). Using an exploratory mixed-methods concurrent design,68 we will evaluate the IKT process and perceived impacts and outcomes of IKT approaches with the diverse stakeholder groups.

Discussion

This program of research is timely, as Canada and countries across the globe struggle to address multimorbidity, target research and interventions at areas offering the most benefit, and redesign health-care systems. Using the Knowledge-to-Action Framework33 and the Complexity Model22 as the overarching frameworks, ACHRU is undertaking several research studies. This article reports on the initial six studies to be undertaken by ACHRU. The following broad principles will guide our research program: (i) the need for a collective impact approach57; (ii) the need for complex interventions that are integrated and target all of the factors that affect patient/family needs; holistic, coordinated, and person-centered rather than single, disease-focused; and feasible, acceptable, and tailored adapted to different populations and settings; and (iii) the need for innovative research designs and methods to capture the complexity of the intervention and context. These principles are consistent with the Complexity Model.22

This research program will make several important contributions to the existing knowledge base. First, it investigates the effectiveness of different integrated and person-centered interventions in a complex population that is understudied and underserved. This population is particularly at risk of adverse outcomes, yet they are often excluded from RCTs.69 As a result, their needs are poorly understood and evidence of the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving care and quality of life in this vulnerable group is lacking.69

Second, a comprehensive approach is used to examine costs, which is rare in intervention studies. The intervention studies will include a cost analysis, conducted from a societal perspective. This will provide policy makers with critical information on the resource implications of the interventions to facilitate decision-making.

Third, this research program supports the development and testing of innovative research designs (methods and analysis) to evaluate interventions to better reflect “real-world” conditions and to further implement science methodology. The trials will use a pragmatic mixed-methods RCT that employ a type 2 hybrid design, which simultaneously evaluates both clinical effectiveness (e.g. Does the intervention work?) and implementation (e.g. Is the intervention delivery feasible and acceptable?).41 Our RCTs are pragmatic, capturing patient’s representative of those seen in practice, and delivering the intervention in a real-world setting using existing providers. Multiple approaches enhance intervention fidelity, including provider training, a standardized training manual, and regular meetings between the researchers and providers.

Fourth, the research will result in new knowledge about how to meaningfully engage stakeholders, including patients/caregivers in research (including codesign of interventions, selection of outcomes, interpretation and dissemination of results).

Fifth, the research will adapt and evaluate the Complexity Model to inform the design, implementation, evaluation, and scale-up of interventions for older adults with multimorbidity. Current care models for multimorbidity and best practice guidelines for chronic disease management are largely based on medical interventions provided in health systems. To improve care for this population, these care models must integrate the social and medical components to address the spectrum of factors driving complexity. Tackling this issue through the development of complex, integrated, and person-centered interventions will help to reduce health disparities and promote health equity.

Potential outcomes and impact

Multimorbidity is common in older adults, and evidence supporting specific interventions is limited.69 The ACHRU research program was designed to address gaps in clinical care for this population, and to provide evidence for effective interventions for this population. Based on the results of our earlier feasibility studies44,48,56 and previous trials56,70–73, it is expected that the interventions in this research program will result in improved Triple Aim outcomes for older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers.24 The importance of achieving such outcomes is fueled by the aging population, growing complexity in patient care needs, concerns about growing health-care system costs and sustainability, and the recognition that our current system is not meeting the needs of older adults with multimorbidity.15 The research will result in knowledge about the critical components for achieving all three of the Triple Aim outcomes, such as strong leadership and governance, engaged interprofessional teams, and partnering within and beyond the health-care sector across jurisdictions, and with diverse groups.

Evidence of effectiveness of the interventions in diverse home and community care settings, across jurisdictions, and with diverse groups will provide a foundation for planning for scale-up. This includes providing information on how to tailor and adapt the interventions across jurisdictions and diverse populations and settings. This knowledge can be used to guide health services policy decisions and the allocation of health-care resources for older adults with multimorbidity and their family caregivers.

The strong patient, caregiver, and decision-maker engagement plan and the IKT plan highlight our broad and in-depth stakeholder engagement plan for all aspects of the research and ensure that these important perspectives are influential in guiding the program. The research program was developed and will be implemented through our robust partnerships with provincial health system decision-makers and multiple home and community care partners. This will create a dynamic and responsive learning system to evaluate and scale-up new approaches to the delivery of community-based care within and across sectors (primary, home, and community care) and outside the health sector (social services), as well as across jurisdictions. Patients, caregivers, providers, researchers, trainees, and decision-makers will develop knowledge and skills in patient-oriented research and innovative research methods. In addition to the formal IKT events, we plan to transfer knowledge through the creation of KTE products, such as executive summaries, policy briefs, presentations to stakeholder groups, open-access publications and scientific conferences. We will disseminate findings through our KU and partner networks. Implementation tool kits will also be developed, outlining how to plan and implement the interventions to facilitate scale-up of effective interventions.

Conclusions

This protocol paper reports the rationale and plan for a pan-Canadian program of research designed to promote optimal aging at home for older adults with multimorbidity and to support their caregivers. To this end, the research program aims to design and test interventions that will transform health-care systems and services for older adults with multimorbidity and their caregivers by supporting this population to age at home through achieving Triple Aim outcomes: improving health outcomes and patient experience and reducing system costs. In this protocol paper, we described the initial six studies in our research program, and the models and frameworks that underlie the program. The backbone of the research program is the use of a collective impact approach to promote interprofessional and intersectoral collaboration to develop and test interventions that target multiple determinants of health, many of which fall outside of the boundaries of traditional health care.

Supplemental material

Supplemental_File_1_Production_(June_26_2018) for Protocol for a program of research from the Aging, Community and Health Research Unit by Maureen Markle-Reid, Jenny Ploeg, Ruta Valaitis, Wendy Duggleby, Kathryn Fisher, Kimberly Fraser, Rebecca Ganann, Lauren E Griffith, Andrea Gruneir, Carrie McAiney, and Allison Williams for the Aging, Community and Health Research Unit team in Journal of Comorbidity

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution: All authors contributed to the design of this program of research. MMR wrote the first draft of this manuscript, and all authors contributed to the discussion and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was part of a program of research (Aging, Community and Health Research Unit) supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Signature Initiative in Community-Based Primary Health Care (http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/43626.html) (funding reference number: TTF 128261) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health System Research Fund Program (grant no. 06669). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program for Dr Markle-Reid.

ORCID iD: Jenny Ploeg  http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8168-8449

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8168-8449

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Boyd C, Fortin M. Future of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 2010; 32: 451–474. DOI: 10.1007/BF03391611. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Seniors and the health care system: what is the impact of multiple chronic conditions? https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/air-chronic_disease_aib_en.pdf (2011, accessed May 28, 2018).

- 3. Donner G. Bringing care home: the expert group on home and community care, http://health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/lhin/docs/hcc_report.pdf (2015, accessed May 28, 2018).

- 4. Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Strategy for patient-oriented research-patient engagement framework, http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/spor_framework-en.pdf (2014, accessed May 28, 2018).

- 5. Kuluski K, Peckham A, Williams P, et al. What gets in the way of person-centred care for people with multimorbidity? Lessons from Ontario, Canada. Heathc Q 2016; 19: 17–23. DOI: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keon WJ, Pepin L. Population health policy. Ontario, Canada: The Senate of Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tourangeau Outcomes Research. The impact of home care nurse staffing, work environments and collaboration on patient outcomes: phase ii policy implications for Ontario. Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Markle-Reid M, Keller H, Browne G. Health promotion for the community-living older adult In: Fillit H, Rockwood K, Young J. (eds) Brocklehurst’s textbook of geriatric medicine and gerontology. 8th ed Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier, 2010, pp. 835–847. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Home is where the health is: dramatic results show shifting chronic disease care closer to home reduces hospital use, http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/SearchResultsNews/2018/01/23/home-is-where-the-health-is (2018, accessed May 28, 2018).

- 10. Turcotte M. Family caregiving: what are the consequences? Ontario, Canada: Statistics Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hollander MJ, Liu G, Chappell NL. Who cares and how much? The imputed economic contribution to the Canadian healthcare system of middle-aged and older unpaid caregivers providing care to the elderly. Heathc Q 2009; 12: 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, et al. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA 2014; 311: 1052–1060. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: a reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist 2015; 55: 309–319. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnu177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leroy L, Bayliss E, Domino M, et al. The agency for healthcare research and quality multiple chronic conditions research network: overview of research contributions and future priorities. Med Care 2014; 52 Suppl 3: S15–22. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kuluski K, Nelson MLA, Tracy CS, et al. Experience of care as a critical component of health system performance measurement: recommendations for moving forward. Healthc Pap 2017; 17: 8–20. DOI: 10.12927/hcpap.2017.25415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bayliss EA. Simplifying care for complex patients. Ann Fam Med 2012; 10: 3–5. DOI: 10.1370/afm.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dumbreck S, Flynn A, Nairn M, et al. Drug-disease and drug-drug interactions: systematic examination of recommendations in 12 UK national clinical guidelines. BMJ 2015; 350: h949 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.h949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition—multimorbidity. Jama—J Am Med Assoc 2012; 307: 2493–2494. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zullig LL, Whitson HE, Hastings SN, et al. A systematic review of conceptual frameworks of medical complexity and new model development. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31: 329–337. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-015-3512-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen L, Davis R, Cantor J, et al. Reducing health care costs through prevention: working document. California, USA: Prevention Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 3: CD006560 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grembowski D, Schaefer J, Johnson KE, et al. A conceptual model of the role of complexity in the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care 2014; 52 Suppl 3: S7–S14. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bayliss EA, Bonds DE, Boyd CM, et al. Understanding the context of health for persons with multiple chronic conditions: moving from what is the matter to what matters. Ann Fam Med 2014; 12: 260–269. DOI: 10.1370/afm.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008; 27: 759–769. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Public Health Agency of Canada. Heart disease in Canada: highlights from the Canadian chronic disease surveillance system, https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/diseases-conditions/heart-disease-fact-sheet/heart-disease-factsheet-eng.pdf (2017, accessed May 28, 2018).

- 26.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases: key facts, http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (2017, accessed May 28, 2018).

- 27. An integrated vascular health blueprint for Ontario. Toronto: Cardiac Care Network of Ontario, Heart and Stroke Foundation and Ontario Stroke Network, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158: 200–207. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson T, Holt T, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: complexity and clinical care. BMJ 2001; 323: 685–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schaink AK, Kuluski K, Lyons RF, et al. A scoping review and thematic classification of patient complexity: offering a unifying framework. J Comorb 2012; 2: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Northwood M, Ploeg J, Markle-Reid M, et al. Integrative review of the social determinants of health in older adults with multimorbidity. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74: 45–60. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Daniel H, Bornstein SS, Kane GC, et al. Addressing social determinants to improve patient care and promote health equity: an American college of physicians position paper. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168: 577–578. DOI: 10.7326/M17-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006; 26: 13–24. DOI: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thorne S, Stephens J, Truant T. Building qualitative study design using nursing’s disciplinary epistemology. J Adv Nurs 2016; 72: 451–460. DOI: 10.1111/jan.12822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Markle-Reid MGA, Ploeg J, Fisher K, et al. Health and social service utilization costing manual. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University, School of Nursing, Aging, Community and Health Research Unit, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hankivsky O, Cormier R. Intersectionality: moving women’s health research and policy forward. Vancouver: Women’s Health Research Network, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. Sf-12: how to score the sf-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Lincoln, USA: QualityMetric Inc., 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Self-Management Resource Center. Self-efficacy for managing chronic disease 6-item scale, https://www.selfmanagementresource.com/docs/pdfs/English_-_self-efficacy_for_managing_chronic_disease_6-item.pdf (accessed May 28, 2018).

- 39. Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit burden interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001; 41: 652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Colin Reid R, Stajduhar KI, Chappell NL. The impact of work interferences on family caregiver outcomes. J Appl Gerontol 2010; 29: 267–289. DOI: 10.1177/0733464809339591. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012; 50: 217–226. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. RE-AIM. Re-aim: reach effectiveness adoption implementation maintenance, www.re-aim.org (2017, accessed November 10, 2017).

- 43. Meleis A. Transitions theory: middle-range and situation specific theories in nursing research and practice. 1st ed New York, USA: Springer Publishing Company, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Duggleby W, Swindle J, Peacock S. Self-administered intervention for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Nurs Res 2014; 23: 20–35. DOI: 10.1177/1054773812474299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Browne G, Gafni A, Roberts J. Approach to the measurement of resource use and costs (working paper S06-01). Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: McMaster University, System-Linked Research Unit on Health and Social Service Utilization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977; 84: 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed New York, USA: The Guilford Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Markle-Reid M, Ploeg J, Fisher K, et al. The Aging, Community and Health Research Unit—Community Partnership Program for older adults with type 2 diabetes and multiple chronic conditions: a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016; 2: 24 DOI: 10.1186/s40814-016-0063-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oregon Research Institute. Summary of diabetes self-care activities (SDSCA): FAQs, http://www.ori.org/sdsca/faqs (2016, accessed March 3 2017).

- 50. Irwin M, Artin KHH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 1701–1704. DOI: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 2008; 46: 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]