Summary

During development, wound repair and disease-related processes, such as cancer, normal, or neoplastic cell types traffic through the extracellular matrix (ECM), the complex composite of collagens, elastin, glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans that dictate tissue architecture. Current evidence suggests that tissue-invasive processes may proceed by protease-dependent or protease-independent strategies whose selection is not only governed by the characteristics of the motile cell population, but also by the structural properties of the intervening ECM. Herein, we review the mechanisms by which ECM dimensionality, elasticity, crosslinking, and pore size impact patterns of cell invasion. This summary should prove useful when designing new experimental approaches for interrogating invasion programs as well as identifying potential cellular targets for next-generation therapeutics.

Keywords: Extracellular matrix (ECM), invasion, MT1-MMP

Introduction

In cancer, neoplastic cells inappropriately co-opt normal cell function and escape from their primary locale by engaging invasive machinery that had been ostensibly engineered to control the regulated motility programs operative during growth and development (Rowe & Weiss, 2009; Kessenbrock et al., 2010; Wolf & Friedl, 2011). Tumour progression and invasion are often linked to the up-regulated expression of proteolytic enzymes—generated by both cancer cells and the surrounding tumour microenvironment—that are capable of degrading the major extracellular matrix (ECM) macromolecules that comprise all connective tissues (Rowe & Weiss, 2009; Kessenbrock et al., 2010; Wolf & Friedl, 2011; Lu et al., 2012). To date, multiple proteases have been implicated in the ECM remodelling events associated with cancer, but conflicting results have been reported which question the issue of whether proteolysis is an obligate step in tissue-invasive processes (Rowe & Weiss, 2009; Sabeh et al., 2009; Sabeh et al., 2009b; Kessenbrock et al., 2010; Wolf & Friedl, 2011). Whereas many groups have reported that cancer cells can only traverse the ECM via the proteolytic dissolution of intervening structural barriers, others have proposed that neoplastic cells can push or squeeze their way through matrix barriers without mobilizing proteases (Wolf et al., 2003, 2007; Sabeh et al., 2004; Sabeh et al., 2009; Madsen & Sahai, 2010; Wolf & Friedl, 2011; Friedl et al., 2012). As such, emerging models of invasion will be reviewed in an effort to help resolve apparent inconsistencies in the field and to outline new experimental approaches that may be applied to outstanding questions.

ECM-based models for proteolytic and nonproteolytic cell invasion and migration

To define the mechanisms that allow cancer cells to infiltrate ECM barriers by protease-dependent or protease-independent processes, a number of in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo models have been developed (Rowe & Weiss, 2008, 2009; Ehrbar et al., 2011; Wolf & Friedl, 2011; Friedl et al., 2012; Petrie et al., 2012). In overview, these models have been developed to analyze the mechanisms by which neoplastic cells invade the two major ECM subtypes, that is the basement membrane (BM) and the interstitium (Rowe & Weiss, 2008, 2009; Ehrbar et al., 2011; Wolf & Friedl, 2011; Friedl et al. 2012; Petrie et al., 2012). As each construct displays its own unique mix of experimental strengths and weaknesses, insights may only be gleaned from such studies with an appreciation of the limitations inherent in these systems.

Basement membrane

All epithelial layers are subtended by a several hundred nanometer-thick, sheet-like BM, largely comprised of two interlocking networks of heterotrimeric type IV collagen and laminin isoforms which are further interwoven with 25 or more distinct glycoproteins and proteoglycans (Candiello et al., 2007; Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Balasubramani et al., 2010; Yurchenco, 2011). BM constituents are distributed in a tissue-specific fashion that varies with developmental stage (Kabosova et al., 2007; Bai et al., 2009; Candiello et al., 2010). Despite their heterogeneity, the structural and mechanical integrity of BMs is determined primarily by type IV collagen intra-and inter-molecular covalent crosslinks that include disulfide, aldimine and newly characterized, peroxidasin-catalyzed sulfilimine bonds (Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Vanacore et al., 2009; Bhave et al., 2012; Weiss, 2012). Given an effective BM pore diameter ranging from 10 to 90 nm (as assessed by a battery of electron and atomic force microscopic techniques) (Yurchenco & Ruben, 1987; Yurchenco et al., 1992; Abrams et al., 2000) whose size is considerably smaller than the 1–2 μm pores that migrating cells can negotiate, it is difficult to envision a molecular mechanism that enables protease-independent cancer cell invasion across native BMs (Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Wolf et al., 2013). Moreover, cell trafficking through the BM during growth and development—in animal systems ranging from primitive model organisms to higher vertebrates—is tightly associated with proteolytic remodelling (Hotary et al., 2006; Srivastava et al., 2007; Page-McCaw, 2008; Ota et al., 2009; Rebustini et al., 2009; Matus et al., 2010; Yasunaga et al., 2010). From where then has the proposition emerged that proteases need not play a required role in allowing normal or neoplastic cells (of either epithelial or mesenchymal origin) to traverse intact BMs? In large part, the conclusion that cancer cells adopt a protease-independent, amoeboid-like phenotype during BM invasion can be linked to the use of in vitro constructs designed to recapitulate native BM structure (Rowe & Weiss, 2008). Despite the fact that surface nanotopography, rigidity, and BM macromolecular composition all impact cell function, BM ‘mimics’ have, until recently, been limited to the use of Matrigel, a self-assembling hydrogel derived from tumour cell extracts (Gadea et al., 2007; Sahai et al., 2007; Fackler & Grosse, 2008; Poincloux et al., 2011; Rao et al., 2012; Tilghman et al., 2012). Matrigel, like native BMs, contains type IV collagen and laminin, but the polymeric complex is dominated by laminin (rather than type IV collagen) and is largely devoid of the type IV collagen crosslinks that define the structural properties of native BMs (Rowe & Weiss, 2008). Indeed, unlike native BMs that remain insoluble under harsh extraction conditions, Matrigel hydrogels are readily solubilized by mild chaotropes (Rowe & Weiss, 2008). Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate that the elastic modulus (i.e. rigidity) of Matrigel hydrogels is orders of magnitude less than that of BMs assembled in vivo (Candiello et al., 2007; Soofi et al., 2009). Difficulties in interpreting Matrigel-centric experimental designs—at least with regard to invasion—are further compounded by the frequent decision to embed tumour cells within thick, 3-D hydrogels (Gadea et al., 2007; Sahai et al., 2007; Poincloux et al., 2011). Whereas well appreciated that cell behaviour is affected in distinct fashions when cultured under 2-D versus 3-D conditions (Hotary et al., 2003; Yamada & Cukierman, 2007; Grinnell & Petroll, 2010), normal epithelial cells as well as their transformed counterparts only interface a planar, 100–400 nm-thick BM layer in the in vivo setting (Candiello et al., 2007; Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Balasubramani et al., 2010). As such, the (patho)physiologic relevance of monitoring cell invasion through a highly elastic hydrogel defined by low concentrations of noncrosslinked type IV collagen remains questionable (Rowe & Weiss, 2008).

To circumvent the limitations associated with BM mimetics, recent studies have begun analyzing the invasion systems mobilized by normal or neoplastic cells as they transmigrate native BMs either under in vitro or in vivo conditions (Hotary et al., 2006; Srivastava et al., 2007; Page-McCaw, 2008; Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Ota et al., 2009; Rebustini et al., 2009; Rottiers et al., 2009; Matus et al., 2010; Schoumacher et al., 2010; Yasunaga et al., 2010; Hagedorn & Sherwood, 2011). Remarkably, model organisms as well as mammalian cells appear to share complementary BM invasion programs that couple transmigration with ECM proteolysis (Hotary et al., 2006; Srivastava et al., 2007; Page-McCaw, 2008; Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Ota et al., 2009; Rebustini et al., 2009; Rottiers et al., 2009; Matus et al., 2010; Schoumacher et al., 2010; Yasunaga et al., 2010; Hagedorn & Sherwood, 2011; Stevens & Page-McCaw, 2012). In many of these systems, experimental results highlight key roles for membrane-tethered metalloenzymes belonging to the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family, that is the so-called the membrane-type MMPs (MT-MMPs) (Hotary et al., 2006; Srivastava et al., 2007; Page-McCaw, 2008; Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Ota et al., 2009; Rebustini et al., 2009; Yasunaga et al., 2010). As this proteinase class has been the subject of recent reviews (Barbolina & Stack, 2008; Poincloux et al., 2009; Rowe & Weiss, 2009; Strongin, 2010), our discussion of these enzymes will be confined to a short summary of their pertinent features. In mammals, six MT-MMPs have been characterized. At least three of the MT-MMPs (i.e. MT1-MMP, MT2-MMP and MT3-MMP) are able to confer recipient cells with the ability to proteolytically remodel native BM structures and trigger transmigration (Hotary et al., 2006; Ota et al., 2009; Rebustini et al., 2009; Riggins et al., 2010). Like all proteolytic enzymes, the MT-MMPs are synthesized as proenzymes, and undergo intercellular activation when their propeptide domains are proteolytically removed during their transit through the trans-Golgi network to the cell surface (Barbolina & Stack, 2008; Poincloux et al., 2009; Rowe & Weiss, 2009; Golubkov et al., 2011). In most cases, MT-MMPs appear to be directed to invadopodia-like structures which allow cells to ‘focus’ their degradative potential to discrete, subjacent zones that support ECM tunnelling programs while maintaining the structural integrity of the surrounding matrix so as to support propulsive movement (Hotary et al., 2006; Ota et al., 2009; Poincloux et al., 2009; Wang & McNiven, 2012; Yu et al., 2012). Whereas recent studies have emphasized the role of the 20-amino acid long MT1-MMP cytosolic tail in regulating proteolytic and invasive activity (Wu et al., 2005; Wang & McNiven, 2012; Yu et al., 2012), native BM barriers can be transmigrated—in vitro as well as in vivo—in the absence of this domain (Hotary et al., 2006; Ota et al., 2009). Importantly, MT-MMPs trigger BM remodelling and transmigration programs that function independently of the larger family of secreted MMPs, including the often-cited type IV collagenases, MMP-2 and MMP-9, whose BM-degrading activities remain unproven to date (Rowe & Weiss, 2008).

As Matrigel hydrogels do not recapitulate the structure of native BMs, how is it that many reports have documented the ability of inhibitors directed against secreted or membrane-tethered MMPs to block cell invasion through these constructs [e.g., (Ueda et al., 2003; Zaman et al., 2006; Rizki et al., 2008)]? Importantly, even MMPs devoid of BM-degrading activity can indirectly influence invasion programs by (i) processing ECM-tethered growth factors to active intermediates, (ii) hydrolyzing membrane-anchored ligands, (iii) activating/inactivating secreted chemokines, or (iv) triggering motility independently of proteolytic activity (Barbolina & Stack, 2008; Kessenbrock et al., 2010; Strongin, 2010; Dufour et al., 2011; auf dem Keller et al., 2013). In this regard, it should be stressed that neither secreted MMPs nor members of any other protease class have been shown to confer expressing cells with the ability to traverse intact BMs (Hotary et al., 2006; Ota et al., 2009). Consistent with an accessory, rather than required role for MMPs in Matrigel invasion, several groups have independently confirmed the ability of multiple cell types to infiltrate these hydrogels in the presence of MMP inhibitors (Even-Ram & Yamada, 2005; Hotary et al., 2006; Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Sodek et al., 2008; Poincloux et al., 2011). As the pore sizes of these hydrogels are estimated to fall within the range of 1–2 μm in diameter (assessed by quick-freeze transmission electron microscopy), MMP-independent invasion mechanisms are most consistent with a model wherein the noncrosslinked components of Matrigel can be mechanically displaced by the migrating cancer cells (Poincloux et al., 2011).

Interstitium

The ECM of connective tissues is dominated by the interstitial collagens (most commonly, type I collagen) that serve as the single-most abundant extracellular proteins found in mammals (Rowe & Weiss, 2009; Grinnell & Petroll, 2010). Coincident with their secretion from fibroblasts, the collagen propeptide domains are proteolytically removed, and a complex auto-polymerization process is initiated (Kadler et al., 2008). Upon lysyl oxidase-mediated crosslinking within the N- and C-terminal nonhelical ends of the secreted and processed collagen molecules (i.e. the telopeptide domains), the fibrils mature into a mechanically reinforced network of fibres and fibre bundles (Eyre et al., 1984; Christiansen et al., 2000). Given the tremendous tissue-to-tissue heterogeneity in interstitial collagen content and crosslink structure (Eyre et al., 1984; Christiansen et al., 2000; Kadler et al., 2008; Wolf et al., 2009), trafficking cancer cells—as well as recruited stromal cells—would be expected to encounter structurally distinct barriers.

In considering the stratagems that might be deployed at cell-ECM interfaces, a consensus of opinion is building to support a two-body model of invasion. In this model, the size and elasticity of the infiltrating cell’s most mechanically rigid sub-cellular compartment, that is the nucleus, dictates the manner in which cells negotiate the fibrillar network of the interstitial matrix (Nakayama et al., 2005; Wolf et al., 2007; Beadle et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2009; Friedl et al., 2011; Khatau et al., 2012). If the dimensions of a rigid matrix pore are too small to accommodate the nuclear dimensions of the trafficking cell, the barrier will prove impassable unless the matrix is proteolytically remodelled. On the other hand, if the pore size of the matrix is larger than the cell’s nuclear dimensions, a physical barrier to cell traffic no longer exists, and invasion proceeds independently of protease-dependent remodelling (Wolf et al., 2013). A more complex invasion scheme is envisioned under those circumstances where the pore size is too small to support passive cell movement, but the barrier might yet be negotiated by either (i) ECM-degrading proteases (i.e. akin to cutting through the bars of a ‘cage’), (ii) actomyosin motors and cell adhesion molecules working in concert to mechanically distort the surrounding matrix—in this case, ‘bending’ the cage bars (Friedrichs et al., 2007) or (iii) intracellular contractile machinery that alters nuclear dimensions, thus permitting invasion to proceed by cell ‘squeezing’ through a nondeformable matrix cage (Nakayama et al., 2005; Beadle et al., 2008; Friedl et al., 2011; Balzer et al., 2012; Khatau et al., 2012). Whereas portions of these schemes remain somewhat conjectural in nature, recent evidence culled from in vitro and in vivo systems lends support to these models.

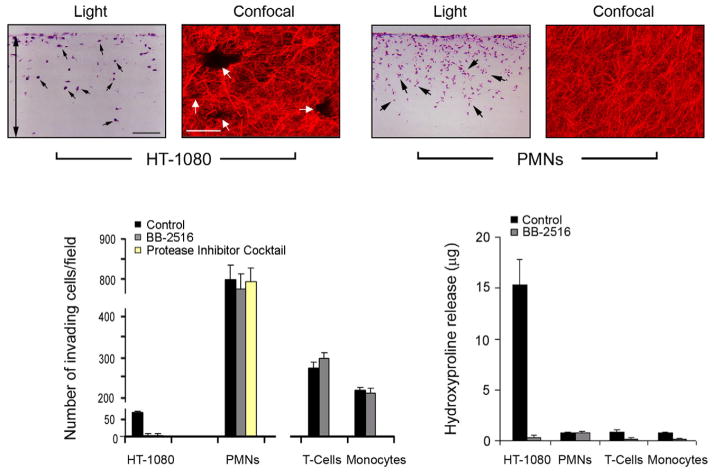

Protease-dependent migration in vitro: covalently crosslinked collagen hydrogels

In vitro studies of cell behaviour in 3-D models of the interstitial matrix have long relied on the use of acid extracts of rat tail tendons – both because of their ability to yield relatively pure solutions of type I collagen as well as the ability to recover full-length type I collagen molecules with intact telopeptide domains (Sabeh et al., 2009). Using these extracts, collagen fibrillogenesis is initiated by manipulating pH, ionic strength and temperature (Raub et al., 2007, 2008). Under standard conditions (i.e. pH ≃7.4, iso-osmotic buffers and 37°C), 2–4 mg/mL solutions of rat tail tendon collagen yield an aldimine-crosslinked network of fibrils with an effective pore diameter in the range of 1–3 μm (Raub et al., 2007, 2008; Mickel et al., 2008). Using these matrices, a number of groups have consistently reported that cancer cells—as well as normal endothelial, fibroblast, bone marrow stromal/stem cells and smooth muscle cells—display tissue-invasive behaviour that is solely dependent on the mobilization of collagenolytic MMPs (primarily MT1-MMP or MT2-MMP, and perhaps, MT3-MMP) (Sabehet al., 2004; Sodeket al., 2007,2008; Fisheret al., 2009; Rowe & Weiss, 2009; Sabeh et al., 2009; Sabeh et al., 2009b; Stratman et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2010; Sabeh et al., 2010; Rowe et al., 2011). Given our previously described rules of invasion, one presumes that the pores generated in these collagen matrices are sufficiently small and rigid to preclude a protease-independent motile response – a recently confirmed prediction (Wolf et al., 2013). Two exceptions exist, however, to the ‘protease required’ rule. First, after tissue-invasive cells have ‘tunnelled’ through the collagen matrix, patent passageways can be created that allow trailing cells to follow the proteolytic leader by distinct, protease-independent schemes (though some reports have used type I collagen-Matrigel mixtures that may distort the fibrous structure of the network) (Gaggioli et al., 2007; Dewitt et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2009; Carey et al., 2013). Hence, normal or neoplastic cells can traverse crosslinked collagen matrices without mobilizing proteases, but only if a passageway has already been cleared. Second, unlike all other cancer cell types, myeloid cells (i.e. leukocytes) freely traverse crosslinked hydrogels without proteolyzing the collagen network (Lammermann et al., 2008; Sabeh et al., 2009). Apparently, leukocytes negotiate collagenous barriers by applying two principles unavailable to other cell types; (i) they do not rely heavily on integrins to establish cell-matrix adhesive interactions and (ii) their nuclei are deficient in lamin A/C, a key component of the nuclear scaffold that impacts the rigidity of the organelle (Lammermann et al., 2008; Olins et al., 2009; Friedl et al., 2011; Rowat et al., 2013; Wolf et al., 2013). The unusual ability of leukocytes to rapidly infiltrate tissues is likely a required component of an effective host defense system where microbes must be intercepted quickly. While it is tempting to speculate that cancer cells might adopt a similar phenotype, no neoplastic cell type (save for those of myeloid origin) has yet been shown to display a similar capability. Indeed, though it has been opined that leukocyte-centric schemes for traversing ECM barriers may be relevant to cancer cell invasion schemes (Madsen & Sahai, 2010), side-by-side comparisons—at least in vitro—suggest otherwise (Sabeh et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2013). That is, whereas cancer cell invasion through type I collagen gels in tightly linked to MT1-MMP-dependent collagenolytic activity and the formation of collagen “tunnels” whose generation can be inhibited completely by synthetic MMP inhibitors, human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), T-cells or monocytes traverse the same collagen gels without degrading the collagen matrix or leaving discernible tunnels (Fig. 1). Further, whereas aggressive cancer cells require several days to mount an invasion program through dense collagen barriers, human leukocytes, particularly PMNs, complete the bulk of their invasive activity within 4 h via a process that is unaffected by MMP inhibitors or protease inhibitors cocktails (Fig. 1) (Huber & Weiss, 1989; Sabeh et al., 2009). Similarly, though MT1-MMP has been posited to play a direct role in macrophage invasion (Sakamoto & Seiki, 2009), MT1-MMP-null monocytes/macrophages display no major defects in transmigrating tissue barriers in vitro or in vivo following transfer of MT1-MMP knockout bone marrow into wild-type recipients (Xiong et al., 2009; Shimizu-Hirota et al., 2012). In a more recent study, the conditional knockout of MT1-MMP in mouse monocyte/macrophages resulted in subtle defects in cellular infiltration whose mechanistic underpinnings remain to be determined (Klose et al., 2013). Indeed, highlighting the complexity of assigning specific functions to proteinases in intact cell systems, MT1-MMP unexpectedly regulates macrophage gene expression and immune responses via a novel proteinase-independent mechanism requiring MT1-MMP intracellular trafficking to the nuclear compartment (Shimizu-Hirota et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

Collagen-invasive and degradative activities of cancer cells versus leukocytes. Light micrographs of cross-sections of type I collagen gels (2.2 mg/mL) traversed by HT-1080 or human PMNs prepared as described (Sabeh et al., 2009) for 3 d or 1 d, respectively. Collagen-invasive cells are H&E stained and marked with black arrows. Double-headed arrow marks the boundaries of the underlying collagen gel. Black bar = 100 μm. Laser confocal micrographs of HT-1080 cells cultured atop 3D gels of rhodamine-labeled type I collagen for 3 d demonstrate that invasion is associated with the formation of well-demarcated tunnels (white arrows; white bar = 50 μm). On the other hand, PMNs stimulated with zymosan-activated plasma (Huber and Weiss, 1989) invade rhodamine-labeled collagen gels without perturbing matrix architecture (far right-hand panel). Invasion and collagen-degradative activities of HT-1080, PMNs, T cells, and monocytes were quantified in the absence or presence of BB-2516 (1.5 μM) as described previously (bar graphs, bottom panel) (Sabeh et al., 2004). PMN invasion was also assessed in the presence of the protease inhibitor cocktail prepared as described (Wolf et al., 2003). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4). Images and data are reproduced from the original work (Sabeh et al., 2009).

Protease-independent migration in vitro: pepsin-extracted collagen hydrogels and beyond

As animals age, the intramolecular crosslinks found in type I collagen undergo a complex maturation process that renders the molecules acid-insoluble (Sabeh et al., 2009). For commercial purposes, large quantities of type I collagen can nevertheless be recovered from animal dermis (primarily bovine in origin) by employing a pepsin-extraction process that hydrolyzes the crosslink-rich telopeptide domains, leaving the tripe-helical domains intact (Sabeh et al., 2009; Kreger et al., 2010; Bailey et al., 2011). Like acid-extracted native collagen, telopeptide domain-free collagen undergoes fibrillogenesis in a pH-, ionic strength- and temperature-dependent fashion. The polymerization process is, however, delayed relative to intact type I collagen, and can yield hydrogels with larger diameter fibrils and consequently, larger pore sizes (Kuznetsova & Leikin, 1999; Olins et al., 2009). The degree to which fibril diameter and pore size are altered remains the subject of some debate as techniques used to judge fibril dimensions, that is primarily confocal reflection microscopy and second harmonic generation, can underestimate fiber density or size while distorting pore size estimates (Sato et al., 2000; Demou et al., 2005; Jawerth et al., 2010; Kreger et al., 2010; Conklin et al., 2011). Nevertheless, reports using pepsin-extracted bovine dermal collagen (previously sold under the name, Vitrogen) or pepsin-treated rat tail collagen, all concur that cancer cells can rapidly infiltrate telopeptide-depleted collagen hydrogels in a protease-independent fashion (Wolf et al., 2003; Sabeh et al., 2004; Sodek et al., 2008; Packard et al., 2009; Sabeh et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2013). As new studies demonstrate that the pore size of pepsin-extracted collagen hydrogels is sufficiently large to accommodate the nuclear dimensions of invading cancer cells (Wolf et al., 2013), these matrices may well recapitulate the structural characteristics of loosely organized tissues in vivo (see further). In pepsinized collagen hydrogels, however, the absence of intramolecular crosslinks may also alter (i) matrix rigidity—and hence, cell behavior, (ii) the ability of collagen fibers to bend and slide past one another with the application of mechanical force, (iii) the ability of cells to transmit mechanical information across large distances via tractional forces, and (iv) the sensitivity of the telopeptide-free fibrils to collagenolytic attack (Woodley et al., 1991; Discher et al., 2005; Perumal et al., 2008; Sander et al., 2009; Winer et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2013). Even so, pepsinized collagen gels can provide a useful model for interrogating the means by which cells invade less-structured matrices though the physiologic relevance of matrix constructs assembled from telopeptide- and crosslink-depleted collagen remains unclear. More ideally, perhaps, native collagen gels may be constructed under conditions where pore size is purposefully varied (Sabeh et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2013). In fact, collagen fiber diameter and pore size can be tuned by altering the temperature or pH of gelation, though matrix rigidity is also altered under these conditions (Mickel et al., 2008; Raub et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010). Indeed, native collagen gels can be traversed by neoplastic cells via protease-independent mechanisms if the pore size is sufficiently large (Wolf et al., 2013). Nevertheless, due appreciation of even ‘simple’ polymerization processes is required when formulating type I collagen hydrogels. “Minor” changes in the preparation of collagen gels (e.g. the source of acid-extracted type I collagen, the length of time that neutralized collagen solutions are held at 4°C prior to gelation or the thickness of the cast gel) can all affect the physical properties of the hydrogels as well as the behaviour of embedded cell populations (Jiang et al., 2000; Bailey et al., 2011; Carey et al., 2012; Nguyen-Ngoc & Ewald, 2013). Likewise, as migrating cells move closer to the edges of hydrogels constructed within rigid supports (i.e. glass or plastic containers), abrupt increases in matrix rigidity occur at the gel-support interface via edge effects that can also impact cell phenotype (Rao et al., 2012).

Independent of these cautionary notes, hydrogel pore size is an important determinant of protease-dependent versus proteinase-independent migration schemes (Wolf et al., 2013). Interestingly, even in the absence of ECM barriers that require proteolytic remodelling, marked changes are observed in the motile strategies used by cancer cells to traverse variably sized channel diameters in micro-engineered migration chambers (Rolli et al., 2010; Balzer et al., 2012; Pathak & Kumar, 2012; Tong et al., 2012). Most remarkably, confining carcinoma cells to increasingly smaller channel diameters, Balzer and colleagues demonstrated that motility switches from an integrin-and actomyosin-dependent mechanism to one that relies on microtubule dynamics alone (Balzer et al., 2012).

Devil in the details: Amoeboid-type invasion patterns in vivo

Until recently, many groups concluded that cancer cells readily traverse type I collagen barriers by adopting an amoeboid phenotype characterized by its insensitivity to broad-spectrum proteinase inhibitors (for review, see Sabeh et al., 2009). We now know, however, that a wide variety of cancer cell types are absolutely dependent on MT1-MMP when confronting crosslinked type I collagen barriers whose mean pore diameter requires changes in nuclear shape that exceed the maximal deformability of the nuclear envelope (Sabeh et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2013). Nevertheless, cancer cells can potentially adopt a protease-independent stance when negotiating structural barriers that can either accommodate the semi-deformable nuclear envelope or prove sensitive to mechanical displacement. Presently, however, little is known with regard to the size or structural characteristics of ECM pore sites encountered within the interstitial compartment in vivo (Sabeh et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2009). Keeping in mind the limitations associated with documenting pore size by confocal reflection microscopy or second harmonic generation alone (Conklin et al., 2011), in vivo tissue estimates have ranged from 4 to 10 μm2 “micropores” to 40 to 1000 μm2 ‘macropores’ (Wolf et al., 2009). These results raise the possibility that collagen constructs assembled in vitro may not recapitulate fully the more complex networks assembled in vivo. However, it should be noted that defects in vascular smooth muscle cell migration, adipocyte differentiation and stem cell lineage commitment observed in MT1-MMP-targeted mice have been duplicated in vitro using dense, acid-extracted type I collagen hydrogels (Filippov et al., 2005; Chun et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2013). Even so, given the more simple composition of type I collagen hydrogels relative to the interstitial matrix in vivo, cancer cell migration into tissue explants has also been used as an alternative, albeit, empirical means for assessing the obligate versus disposable roles of proteases during trafficking through ‘authentic’ matrix pores (Sabeh et al., 2004; Nurmenniemi et al., 2009; Sabeh et al., 2009; Booth et al., 2012). When cultured atop acellular human dermal explants, cancer cell invasion has been reported to proceed only in the presence of MT1-MMP-dependent activity (Sabeh et al., 2004). Whereas the preparation of acellular explants potentially distorts the pore architecture of native tissues, live explants have also been used as a platform for assessing the protease-dependent versus protease-independent invasive activity of cancer cells (Sabeh et al., 2009). Under these more in vivo-like conditions, cancer cell organoids were inoculated into intact human mammary gland tissues. Though monitoring of invasive activity was limited to a short-term, 3-day culture period, cancer cells failed to infiltrate the surrounding tissues in the absence of MT1-MMP activity (Sabeh et al., 2009). Likewise, MT1-MMP has been shown to support metastatic behaviour of breast cancer cells in mouse models in vivo (Perentes et al., 2011). As little evidence of protease-independent invasive activity has been observed in these scenarios, these results support—at least under these specific conditions—the presence of an interstitial matrix pore size that cancer cells are unable to negotiate without mobilizing proteolytic activity.

Of course, ex vivo efforts to directly track patterns of cell invasion fall short of recapitulating the daunting complexities of the in vivo environment. Nevertheless, several groups have launched efforts to characterize cancer cell motility in vivo and the results have, to varying degrees, been illuminating (Provenzano et al., 2009; Friedl et al., 2012; Weigelin, 2012). Estimates of matrix pore size in normal tissues provide insight into the potential trafficking constraints encountered by invading cells under baseline conditions (Wolf et al., 2009). However, primary tumour sites are frequently associated with the deposition of dense bands of interstitial collagen that increase matrix density and rigidity (Levental et al., 2009; Provenzano et al., 2009). Indeed, in syngeneic mouse models of breast cancer, neoplastic cells interface directly with collagen fibrils that appear to present invading cells with a physical barrier to passive movement (Provenzano et al., 2009). Further, in mouse models of breast cancer, neoplastic cells at the invading front have been observed to contain large quantities of ingested type I collagen, a finding consistent with the proposition that active collagenolysis is integral to the invasion process as cells confront tissue barriers in vivo (Curino et al., 2005). Interestingly, the diameter of collagen fibers deposited at neoplastic sites in vivo also matches that of self-polymerizing collagen hydrogels prepared from acid-extracted type I collagen under standard conditions (Oldberg et al., 2007). Nevertheless, despite indications that neoplastic cells encounter collagenous barriers in vivo that necessitate proteolytic remodelling, other studies have documented the appearance of rapidly migrating cancer cell populations that move with a rapid, amoeboid-like morphology (Madsen & Sahai, 2010). Furthermore, the invasive potential of these cells appears to be insensitive to MMP inhibitors in the in vivo setting (Wolf et al., 2003; Madsen & Sahai, 2010). Whereas the observed migration patterns are certainly consistent with cancer cell movement through larger, non-constraining matrix pores, these results alternatively reflect the ability of cancer cells to rapidly migrate through proteolytically precleared tunnels via proteinase-independent processes similar to those observed in vitro (Sabeh et al., 2004; Gaggioli et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2009; Carey et al., 2013). Interestingly, more recent work supports, however, a lower speed of invasion in tumour in the in vivo setting, perhaps reflecting requirements for a proteinase-dependent invasion schemes (Weigelin, 2012). Distinguishing between these two possibilities remains difficult and will require determined efforts to track the movement of syngeneic tumours from their primary site of origin.

What more is to be done? A proposition and way forward

In vitro studies allow for the formulation of specific questions and the design of rigorous experimental approaches. However, the testing of even “simple” models will require the melding of expertise in ECM biochemistry, bioengineering, cell biology, enzymology and sophisticated imaging technologies, a mix of skill sets seldom if ever found within a single laboratory group (Morell et al., 2013). Furthermore, by venturing into the in vivo setting, additional expertise will be needed in cancer biology and animal modelling as well as the application of specific interventions for silencing proteolytic systems. Attempts to target MMPs in vivo—and this assumes that MMPs play a preeminent role in invasion as opposed to other proteolytic systems—have been confined largely to nonspecific small molecule inhibitors whose efficacy remains the subject of debate (though humanized anticatalytic monoclonal antibodies directed against MT1-MMP have been characterized recently) (Devy et al., 2009). Whereas tissue-specific knockouts are seldom employed for these studies, cooperative interactions between cancer cells and stromal cell populations further complicate efforts to identify a single, monolithic player (Gaggioli et al., 2007; Kessenbrock et al., 2010). Indeed, unpublished efforts ongoing in the Weiss laboratory are focusing on the use of MT1-MMP and MT2-MMP floxed mice to clarify the role of the epithelial-and stromal-derived proteinases in regulating the invasion programs associated with normal mammary gland branching morphogenesis and mammary gland tumorigenesis. Even with all the necessary tools in hand, we cannot overstress the complexities of an ECM comprised of self-polymerizing molecules that can be crosslinked into novel structures by only recently defined processes (Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Vanacore et al., 2009; Bhave et al., 2012; Ilani et al., 2013). Moreover, in terms of understanding mechanisms underlying cancer cell intravasation and extravasation, epithelial BMs likely display characteristics distinct from vascular and lymphatic BMs (Rowe & Weiss, 2008; Pflicke & Sixt, 2009; Rowe & Weiss, 2009), and it is not clear that invasion through the abluminal side of a BM into a vascular/lymphatic network (i.e. intravasation) is equivalent to transmigration from the luminal face of a BM into surrounding stromal tissues (i.e. extravasation). Popular, but perhaps, overly simplistic, cartoon-like depictions of the complex cancer cell-stromal-ECM interface are unlikely to shed new insights into these dynamic environments. Without expending effort to separate dogma from fact, progress in the field will likely be stifled or misguided. New insights into the regulation of the dynamic cancer cell-ECM interface will no doubt require ‘team efforts’ that couple state-of-the-art technologies with scientific rigor. Dividends from these enterprises will accelerate the development of the necessary tools to permit the simultaneous analysis of changes in ECM structure and function as tumour cells infiltrate the 3-D ECM in vitro and in vivo. The identification and specific targeting of the key proteolytic—or nonproteolytic—systems that drive cancer cell invasion in validated model systems should then allow for the resolution of outstanding questions in the field and pave the way for the intelligent design of new interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (CA88308 and CA71699 to SJ Weiss). We thank K. Wolf (Radboud University) for helpful discussions and comments.

References

- Abrams GA, Goodman SL, Nealey PF, Franco M, Murphy CJ. Nanoscale topography of the basement membrane underlying the corneal epithelium of the rhesus macaque. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;299:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s004419900074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- auf dem Keller U, Prudova A, Eckhard U, Fingleton B, Overall CM. Systems-level analysis of proteolytic events in increased vascular permeability and complement activation in skin inflammation. Sci Signal. 2013;6:rs2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Dilworth DJ, Weng YC, Gould DB. Developmental distribution of collagen IV isoforms and relevance to ocular diseases. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JL, Critser PJ, Whittington C, Kuske JL, Yoder MC, Voytik-Harbin SL. Collagen oligomers modulate physical and biological properties of three-dimensional self-assembled matrices. Biopolymers. 2011;95:77–93. doi: 10.1002/bip.21537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramani M, Schreiber EM, Candiello J, Balasubramani GK, Kurtz J, Halfter W. Molecular interactions in the retinal basement membrane system: a proteomic approach. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer EM, Tong Z, Paul CD, Hung WC, Stroka KM, Boggs AE, Martin SS, Konstantopoulos K. Physical confinement alters tumor cell adhesion and migration phenotypes. FASEB J. 2012;26:4045–4056. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-211441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbolina MV, Stack MS. Membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase: substrate diversity in pericellular proteolysis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadle C, Assanah MC, Monzo P, Vallee R, Rosenfeld SS, Canoll P. The role of myosin II in glioma invasion of the brain. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3357–3368. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Cummings CF, Vanacore RM, et al. Peroxidasin forms sulfilimine chemical bonds using hypohalous acids in tissue genesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:784–790. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AJ, Hadley R, Cornett AM, et al. Acellular normal and fibrotic human lung matrices as a culture system for in vitro investigation. Am J Respiratory and Critical Care Med. 2012;186:866–876. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candiello J, Balasubramani M, Schreiber EM, Cole GJ, Mayer U, Halfter W, Lin H. Biomechanical properties of native basement membranes. FEBS J. 2007;274:2897–2908. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candiello J, Cole GJ, Halfter W. Age-dependent changes in the structure, composition and biophysical properties of a human basement membrane. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey SP, Kraning-Rush CM, Williams RM, Reinhart-King CA. Biophysical control of invasive tumor cell behavior by extracellular matrix microarchitecture. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4157–4165. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey SP, Starchenko A, McGregor AL, Reinhart-King CA. Leading malignant cells initiate collective epithelial cell invasion in a three-dimensional heterotypic tumor spheroid model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30:615–630. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9565-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen DL, Huang EK, Silver FH. Assembly of type I collagen: fusion of fibril subunits and the influence of fibril diameter on mechanical properties. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:409–420. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun TH, Hotary KB, Sabeh F, Saltiel AR, Allen ED, Weiss SJ. A pericellular collagenase directs the 3-dimensional development of white adipose tissue. Cell. 2006;125:577–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin MW, Eickhoff JC, Riching KM, Pehlke CA, Eliceiri KW, Provenzano PP, Friedl A, Keely PJ. Aligned collagen is a prognostic signature for survival in human breast carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curino AC, Engelholm LH, Yamada SS, et al. Intracellular collagen degradation mediated by uPARAP/Endo180 is a major pathway of extracellular matrix turnover during malignancy. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:977–985. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demou ZN, Awad M, McKee T, Perentes JY, Wang X, Munn LL, Jain RK, Boucher Y. Lack of telopeptides in fibrillar collagen I promotes the invasion of a metastatic breast tumor cell line. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5674–5682. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devy L, Huang L, Naa L, et al. Selective inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-14 blocks tumor growth, invasion, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1517–1526. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitt DD, Kaszuba SN, Thompson DM, Stegemann JP. Collagen I-matrigel scaffolds for enhanced Schwann cell survival and control of three-dimensional cell morphology. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2785–2793. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2008.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A, Sampson NS, Li J, et al. Small-molecule anti-cancer compounds selectively target the hemopexin domain of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4977–4988. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrbar M, Sala A, Lienemann P, et al. Elucidating the role of matrix stiffness in 3D cell migration and remodeling. Biophys J. 2011;100:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Even-Ram S, Yamada KM. Cell migration in 3D matrix. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre DR, Paz MA, Gallop PM. Cross-linking in collagen and elastin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:717–748. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fackler OT, Grosse R. Cell motility through plasma membrane blebbing. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:879–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippov S, Koenig GC, Chun TH, et al. MT1-matrix metalloproteinase directs arterial wall invasion and neointima formation by vascular smooth muscle cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:663–671. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KE, Sacharidou A, Stratman AN, Mayo AM, Fisher SB, Mahan RD, Davis MJ, Davis GE. MT1-MMP- and Cdc42-dependent signaling co-regulate cell invasion and tunnel formation in 3D collagen matrices. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4558–4569. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Sahai E, Weiss S, Yamada KM. New dimensions in cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:743–747. doi: 10.1038/nrm3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Wolf K, Lammerding J. Nuclear mechanics during cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs J, Taubenberger A, Franz CM, Muller DJ. Cellular remodelling of individual collagen fibrils visualized by time-lapse AFM. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:594–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadea G, de Toledo M, Anguille C, Roux P. Loss of p53 promotes RhoA-ROCK-dependent cell migration and invasion in 3D matrices. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:23–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaggioli C, Hooper S, Hidalgo-Carcedo C, Grosse R, Marshall JF, Harrington K, Sahai E. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1392–1400. doi: 10.1038/ncb1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubkov VS, Chernov AV, Strongin AY. Intradomain cleavage of inhibitory prodomain is essential to protumorigenic function of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34215–34223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F, Petroll WM. Cell motility and mechanics in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:335–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn EJ, Sherwood DR. Cell invasion through basement membrane: the anchor cell breaches the barrier. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotary K, Li XY, Allen E, Stevens SL, Weiss SJ. A cancer cell metalloprotease triad regulates the basement membrane transmigration program. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2673–2686. doi: 10.1101/gad.1451806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotary KB, Allen ED, Brooks PC, Datta NS, Long MW, Weiss SJ. Membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase usurps tumor growth control imposed by the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell. 2003;114:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber AR, Weiss SJ. Disruption of the subendothelial basement membrane during neutrophil diapedesis in an in vitro construct of a blood vessel wall. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1122–1136. doi: 10.1172/JCI113992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilani T, Alon A, Grossman I, Horowitz B, Kartvelishvily E, Cohen SR, Fass D. A secreted disulfide catalyst controls extracellular matrix composition and function. Science. 2013;341:74–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1238279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawerth LM, Munster S, Vader DA, Fabry B, Weitz DA. A blind spot in confocal reflection microscopy: the dependence of fiber brightness on fiber orientation in imaging biopolymer networks. Biophys J. 2010;98:L1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ST, Liao KK, Liao MC, Tang MJ. Age effect of type I collagen on morphogenesis of Mardin-Darby canine kidney cells. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1539–1548. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabosova A, Azar DT, Bannikov GA, et al. Compositional differences between infant and adult human corneal basement membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4989–4999. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadler KE, Hill A, Canty-Laird EG. Collagen fibrillogenesis: fibronectin, integrins, and minor collagens as organizers and nucleators. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatau SB, Bloom RJ, Bajpai S, et al. The distinct roles of the nucleus and nucleus-cytoskeleton connections in three-dimensional cell migration. Sci Rep. 2012;2:488. doi: 10.1038/srep00488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose A, Zigrino P, Mauch C. Monocyte/macrophage MMP-14 modulates cell infiltration and T-cell attraction in contact dermatitis but not in murine wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:755–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreger ST, Bell BJ, Bailey J, Stites E, Kuske J, Waisner B, Voytik-Harbin SL. Polymerization and matrix physical properties as important design considerations for soluble collagen formulations. Biopolymers. 2010;93:690–707. doi: 10.1002/bip.21431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova N, Leikin S. Does the triple helical domain of type I collagen encode molecular recognition and fiber assembly while telopeptides serve as catalytic domains? Effect of proteolytic cleavage on fibrillogenesis and on collagen-collagen interaction in fibers. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36083–36088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammermann T, Bader BL, Monkley SJ, et al. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature. 2008;453:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Li XY, Hu Y, Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. MT1-MMP controls human mesenchymal stem cell trafficking and differentiation. Blood. 2010;115:221–229. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-228494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Schickel ME, Stevenson MD, Sarang-Sieminski AL, Gooch KJ, Ghadiali SN, Hart RT. Fibers in the extracellular matrix enable long-range stress transmission between cells. Biophys J. 2013;104:1410–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen CD, Sahai E. Cancer dissemination–lessons from leukocytes. Dev Cell. 2010;19:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus DQ, Li XY, Durbin S, Agarwal D, Chi Q, Weiss SJ, Sherwood DR. In vivo identification of regulators of cell invasion across basement membranes. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra35. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickel W, Munster S, Jawerth LM, et al. Robust pore size analysis of filamentous networks from three-dimensional confocal microscopy. Biophys J. 2008;95:6072–6080. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.135939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell M, Nguyen Duc T, Willis A, et al. Coupling Protein Engineering with Probe Design To Inhibit and Image Matrix Metalloproteinases with Controlled Specificity. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9139–9148. doi: 10.1021/ja403523p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M, Amano M, Katsumi A, Kaneko T, Kawabata S, Takefuji M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase and myosin II activities are required for cell type and environment specific migration. Genes Cells. 2005;10:107–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Ngoc KV, Ewald AJ. Mammary ductal elongation and myoepithelial migration are regulated by the composition of the extracellular matrix. J Microsc. 2013;251:212–223. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurmenniemi S, Sinikumpu T, Alahuhta I, et al. A novel organotypic model mimics the tumor microenvironment. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1281–1291. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldberg A, Kalamajski S, Salnikov AV, Stuhr L, Morgelin M, Reed RK, Heldin NE, Rubin K. Collagen-binding proteoglycan fibromodulin can determine stroma matrix structure and fluid balance in experimental carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13966–13971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olins AL, Hoang TV, Zwerger M, et al. The LINC-less granulocyte nucleus. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota I, Li XY, Hu Y, Weiss SJ. Induction of a MT1-MMP and MT2-MMP-dependent basement membrane transmigration program in cancer cells by Snail1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20318–20323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910962106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard BZ, Artym VV, Komoriya A, Yamada KM. Direct visualization of protease activity on cells migrating in three-dimensions. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-McCaw A. Remodeling the model organism: matrix metalloproteinase functions in invertebrates. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak A, Kumar S. Independent regulation of tumor cell migration by matrix stiffness and confinement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:10334–10339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118073109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perentes JY, Kirkpatrick ND, Nagano S, et al. Cancer cell-associated MT1-MMP promotes blood vessel invasion and distant metastasis in triple-negative mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4527–4538. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perumal S, Antipova O, Orgel JP. Collagen fibril architecture, domain organization, and triple-helical conformation govern its proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2824–2829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710588105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie RJ, Gavara N, Chadwick RS, Yamada KM. Nonpolarized signaling reveals two distinct modes of 3D cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:439–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflicke H, Sixt M. Preformed portals facilitate dendritic cell entry into afferent lymphatic vessels. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2925–2935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poincloux R, Collin O, Lizarraga F, Romao M, Debray M, Piel M, Chavrier P. Contractility of the cell rear drives invasion of breast tumor cells in 3D Matrigel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1943–1948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010396108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poincloux R, Lizarraga F, Chavrier P. Matrix invasion by tumour cells: a focus on MT1-MMP trafficking to invadopodia. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3015–3024. doi: 10.1242/jcs.034561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ. Shining new light on 3D cell motility and the metastatic process. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:638–648. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SS, Bentil S, DeJesus J, Larison J, Hissong A, Dupaix R, Sarkar A, Winter JO. Inherent interfacial mechanical gradients in 3D hydrogels influence tumor cell behaviors. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raub CB, Suresh V, Krasieva T, Lyubovitsky J, Mih JD, Putnam AJ, Tromberg BJ, George SC. Noninvasive assessment of collagen gel microstructure and mechanics using multiphoton microscopy. Biophys J. 2007;92:2212–2222. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raub CB, Unruh J, Suresh V, Krasieva T, Lindmo T, Gratton E, Tromberg BJ, George SC. Image correlation spectroscopy of multiphoton images correlates with collagen mechanical properties. Biophys J. 2008;94:2361–2373. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebustini IT, Myers C, Lassiter KS, et al. MT2-MMP-dependent release of collagen IV NC1 domains regulates submandibular gland branching morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2009;17:482–493. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggins KS, Mernaugh G, Su Y, Quaranta V, Koshikawa N, Seiki M, Pozzi A, Zent R. MT1-MMP-mediated basement membrane remodeling modulates renal development. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2993–3005. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizki A, Weaver VM, Lee SY, et al. A human breast cell model of preinvasive to invasive transition. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1378–1387. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolli CG, Seufferlein T, Kemkemer R, Spatz JP. Impact of tumor cell cytoskeleton organization on invasiveness and migration: a microchannel-based approach. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottiers P, Saltel F, Daubon T, Chaigne-Delalande B, Tridon V, Billottet C, Reuzeau E, Genot E. TGFbeta-induced endothelial podosomes mediate basement membrane collagen degradation in arterial vessels. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4311–4318. doi: 10.1242/jcs.057448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowat AC, Jaalouk DE, Zwerger M, et al. Nuclear envelope composition determines the ability of neutrophil-type cells to passage through micron-scale constrictions. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8610–8618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RG, Keena D, Sabeh F, Willis AL, Weiss SJ. Pulmonary fibroblasts mobilize the membrane-tethered matrix metalloprotease, MT1-MMP, to destructively remodel and invade interstitial type I collagen barriers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L683–692. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00187.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Breaching the basement membrane: who, when and how? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:560–574. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Navigating ECM barriers at the invasive front: the cancer cell-stroma interface. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:567–595. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeh F, Fox D, Weiss SJ. Membrane-type I matrix metalloproteinase-dependent regulation of rheumatoid arthritis synoviocyte function. J Immunol. 2010;184:6396–6406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeh F, Ota I, Holmbeck K, et al. Tumor cell traffic through the extracellular matrix is controlled by the membrane-anchored collagenase MT1-MMP. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:769–781. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeh F, Li XY, Saunders TL, Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Secreted versus membrane-anchored collagenases: relative roles in fibroblast-dependent collagenolysis and invasion. J Biol Chem. 2009b;284:23001–23011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeh F, Shimizu-Hirota R, Weiss SJ. Protease-dependent versus -independent cancer cell invasion programs: three-dimensional amoeboid movement revisited. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:11–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahai E, Garcia-Medina R, Pouyssegur J, Vial E. Smurf1 regulates tumor cell plasticity and motility through degradation of RhoA leading to localized inhibition of contractility. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:35–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T, Seiki M. Cytoplasmic tail of MT1-MMP regulates macrophage motility independently from its protease activity. Genes Cells. 2009;14:617–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander EA, Stylianopoulos T, Tranquillo RT, Barocas VH. Image-based multiscale modeling predicts tissue-level and network-level fiber reorganization in stretched cell-compacted collagen gels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17675–17680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903716106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Ebihara T, Adachi E, Kawashima S, Hattori S, Irie S. Possible involvement of aminotelopeptide in self-assembly and thermal stability of collagen I as revealed by its removal with proteases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25870–25875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoumacher M, Goldman RD, Louvard D, Vignjevic DM. Actin, microtubules, and vimentin intermediate filaments cooperate for elongation of invadopodia. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:541–556. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu-Hirota R, Xiong W, Baxter BT, Kunkel SL, Maillard I, Chen XW, Sabeh F, Liu R, Li XY, Weiss SJ. MT1-MMP regulates the PI3Kdelta.Mi-2/NuRD-dependent control of macrophage immune function. Genes Dev. 2012;26:395–413. doi: 10.1101/gad.178749.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodek KL, Brown TJ, Ringuette MJ. Collagen I but not Matrigel matrices provide an MMP-dependent barrier to ovarian cancer cell penetration. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:223. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodek KL, Ringuette MJ, Brown TJ. MT1-MMP is the critical determinant of matrix degradation and invasion by ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:358–367. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soofi SS, Last JA, Liliensiek SJ, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. The elastic modulus of Matrigel as determined by atomic force microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2009;167:216–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Pastor-Pareja JC, Igaki T, Pagliarini R, Xu T. Basement membrane remodeling is essential for drosophila disc eversion and tumor invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2721–2726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611666104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens LJ, Page-McCaw A. A secreted MMP is required for reepithelialization during wound healing. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1068–1079. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratman AN, Saunders WB, Sacharidou A, Koh W, Fisher KE, Zawieja DC, Davis MJ, Davis GE. Endothelial cell lumen and vascular guidance tunnel formation requires MT1-MMP-dependent proteolysis in 3-dimensional collagen matrices. Blood. 2009;114:237–247. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strongin AY. Proteolytic and non-proteolytic roles of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase in malignancy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Rowe RG, Botvinick EL, et al. MT1-MMP-dependent control of skeletal stem cell commitment via a beta1-Integrin/YAP/TAZ signaling axis. Dev Cell. 2013;25:402–416. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilghman RW, Blais EM, Cowan CR, et al. Matrix rigidity regulates cancer cell growth by modulating cellular metabolism and protein synthesis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Balzer EM, Dallas MR, Hung WC, Stebe KJ, Konstantopoulos K. Chemotaxis of cell populations through confined spaces at single-cell resolution. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda J, Kajita M, Suenaga N, Fujii K, Seiki M. Sequence-specific silencing of MT1-MMP expression suppresses tumor cell migration and invasion: importance of MT1-MMP as a therapeutic target for invasive tumors. Oncogene. 2003;22:8716–8722. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacore R, Ham AJ, Voehler M, et al. A sulfilimine bond identified in collagen IV. Science. 2009;325:1230–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.1176811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, McNiven MA. Invasive matrix degradation at focal adhesions occurs via protease recruitment by a FAK-p130Cas complex. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:375–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201105153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelin B, Bakker G-J, Friedl P. Intravital third harmonic generation microscopy of collective melanoma cell invasion: principles of interface guidance and microvesicle dynamics. Intra Vital. 2012;1:32–43. doi: 10.4161/intv.21223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SJ. Peroxidasin: tying the collagen-sulfilimine knot. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:740–741. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JP, Oake S, Janmey PA. Non-linear elasticity of extra-cellular matrices enables contractile cells to communicate local position and orientation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K, Alexander S, Schacht V, Coussens LM, von Andrian UH, van Rheenen J, Deryugina E, Friedl P. Collagen-based cell migration models in vitro and in vivo. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K, Friedl P. Extracellular matrix determinants of proteolytic and non-proteolytic cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K, Mazo I, Leung H, et al. Compensation mechanism in tumor cell migration: mesenchymal-amoeboid transition after blocking of pericellular proteolysis. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:267–277. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K, te Lindert M, Krause M, et al. Physical limits of cell migration: control by ECM space and nuclear deformation and tuning by proteolysis and traction force. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:1069–1084. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K, Wu YI, Liu Y, Geiger J, Tam E, Overall C, Stack MS, Friedl P. Multi-step pericellular proteolysis controls the transition from individual to collective cancer cell invasion. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:893–904. doi: 10.1038/ncb1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley DT, Yamauchi M, Wynn KC, Mechanic G, Briggaman RA. Collagen telopeptides (cross-linking sites) play a role in collagen gel lattice contraction. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:580–585. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12481920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Gan B, Yoo Y, Guan JL. FAK-mediated src phosphorylation of endophilin A2 inhibits endocytosis of MT1-MMP and promotes ECM degradation. Dev Cell. 2005;9:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Knispel R, MacTaggart J, Greiner TC, Weiss SJ, Baxter BT. Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase regulates macrophage-dependent elastolytic activity and aneurysm formation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1765–1771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806239200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada KM, Cukierman E. Modeling tissue morphogenesis and cancer in 3D. Cell. 2007;130:601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YL, Motte S, Kaufman LJ. Pore size variable type I collagen gels and their interaction with glioma cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5678–5688. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga K, Kanamori T, Morikawa R, Suzuki E, Emoto K. Dendrite reshaping of adult Drosophila sensory neurons requires matrix metalloproteinase-mediated modification of the basement membranes. Dev Cell. 2010;18:621–632. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Zech T, McDonald L, et al. N-WASP coordinates the delivery and F-actin-mediated capture of MT1-MMP at invasive pseudopods. J Cell Biol. 2012;199:527–544. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco PD. Basement membranes: cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004911. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco PD, Cheng YS, Colognato H. Laminin forms an independent network in basement membranes. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:1119–1133. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.5.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco PD, Ruben GC. Basement membrane structure in situ: evidence for lateral associations in the type IV collagen network. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2559–2568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman MH, Trapani LM, Sieminski AL, et al. Migration of tumor cells in 3D matrices is governed by matrix stiffness along with cell-matrix adhesion and proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10889–10894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604460103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]