Abstract

Background

Pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFDs) affect the female population, and the postpartum period can be related to the onset or aggravation of the disease. Early identification of the symptoms and the impact on quality of life can be achieved through assessment instruments.

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate questionnaires used to assess PFD in the postpartum period.

Methods

A systematic review study was conducted, following Preferred Reporting Items for the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria, using the databases: PubMed, Biblioteca Virtual de Saúde (BVS), Web of Science, and Scopus, and the keywords PFD or pelvic floor disorders, postpartum or puerperium, and questionnaire. Articles published up till May 2018 were included, searching for articles using validated questionnaires for the evaluation of PFDs in postpartum women. The articles included were evaluated according to a checklist, and the validation studies and translated versions of the questionnaires were identified.

Results

The search of the databases resulted in 359 papers, and 33 were selected to compose this systematic review, using nine validated questionnaires to assess PFDs in the postpartum period: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS), Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory 20 (PFDI-20), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7), PFDI-46, Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-31), Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire (PFBQ), Female Pelvic Floor Questionnaire, electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire – Pelvic Floor, and PFD questionnaire specific for pregnancy and postpartum. The most frequently reported questionnaires included PFDI-20, PFIQ-7, and ICIQ-VS and are recommended by ICI. In addition, the review identified a specific questionnaire, recently developed, to access PFD during pregnancy and postpartum.

Conclusion

The questionnaires used to evaluate PFD during postpartum period are developed for general population or urology/gynecology patients with incontinence and reinforce the paucity of highly recommended questionnaires designed for postpartum, in order to improve early and specific approach for this period of life.

Keywords: pelvic floor disorders, puerperium, women’s health, primary health care, surveys and questionnaires, patient reported outcome measure

Background

Pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFDs) comprise a wide variety of interrelated clinical conditions, such as urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence (FI), pelvic organ prolapse (POP), sexual dysfunction, and other urogenital symptoms They affect 23%–49% of women in general,1,2 with an increasing incidence estimate to 43.8 million cases in 2050 in developed and developing countries,3,4 resulting in negative repercussions (emotional and physical) on women’s quality of life (QoL).

The development of PFDs is a complex process secondary to multifactorial etiology. The pregnancy–puerperal cycle is one of the periods correlated with the onset or aggravation of the disorders.5 The postpartum period provides a window of opportunity for early identification of symptoms to provide health promotion actions, thus reducing the development of PFDs and their consequences.

The precocious perception of these symptoms in puerperium depends on factors such as access and quality of care from the health team, as urogenital symptoms are accepted by women as a natural consequence of childbirth and/or aging, which may delay the diagnosis and treatment of PFDs.6

The questionnaires are health instruments that aid in fleshing out the proper analysis of the patient.7 They are used to assess PFDs that identify urogenital symptoms, quantify the intensity and severity of symptoms, assess the impact on women’s QoL, and are used as a clinical parameter in the treatment and evolution of PFDs. Moreover, in medical research, they are not invasive features and are low in cost, facilitating the reproducibility of the method.8,9

Thus, the objective of this systematic review is to evaluate questionnaires used to assess PFD in the postpartum period.

Methods

A systematic review of articles was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.10

Search strategy

Articles published until May 2018 were included, and the search was limited to articles published in peer-reviewed journals, using questionnaires for the evaluation of PFDs in postpartum women.

A systematic literature search of studies without limits on the publication date was conducted in the PubMed databases (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Virtual Health Library (http://bvsalud.org), Web of Science (https://isiknowledge.com), and Scopus (https://www.scopus.com). The terms used for the search were pelvic floor dysfunction OR pelvic floor disorders; AND postpartum OR puerperium; AND questionnaire. These keywords were selected according to the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in the National Library of Medicine and also by their synonyms.

Selection of the keywords for searching the databases followed the PICOS model. The Population (P) was defined as women in the postpartum period with no time limit; the Intervention (I) must be the use of questionnaire to evaluate PFD; the Outcome (O) was the results of PFD’s questionnaires; the Comparison group (C) was not applicable; the Study (S) design excluded were data-based articles (eg, review articles, guidelines, books).

Selection strategy

Initially, the duplicated articles were excluded, and then we undertook a screening of titles and abstracts according to the following exclusion criteria: 1) were not published in English, Portuguese, or Spanish languages; 2) were not related to the issue; 3) were not available for free access.

After this step, the remaining articles were read in full text and evaluated according to the following inclusion criteria: 1) in the method section the use of a validated questionnaire, in any female population, to evaluate the PFD must be described. 2) There was no restriction on sample size or study design (eg, cohort study, case–control, randomized clinical trial, cross-sectional studies), except to data-based articles (eg, reviews, guidelines, books).

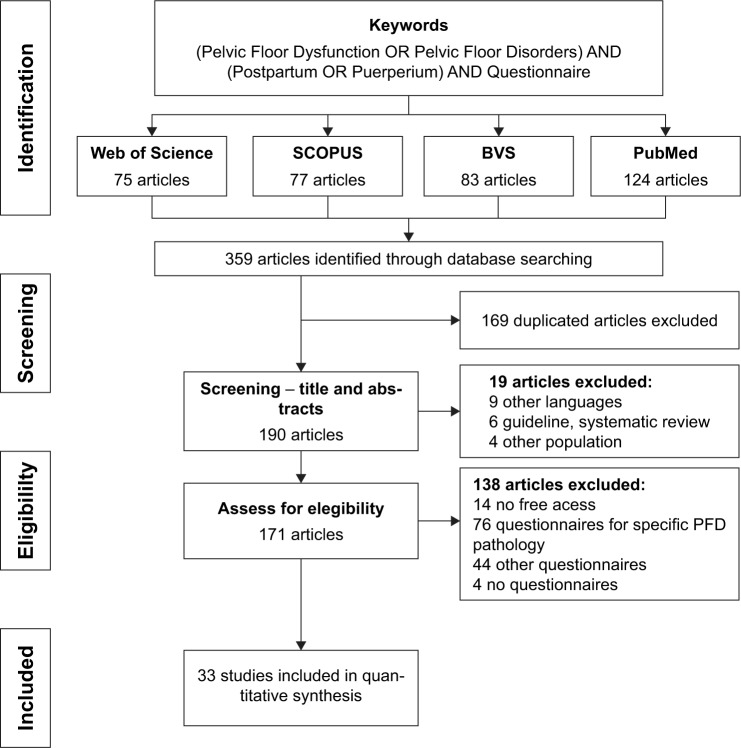

The articles were excluded if they 1) used only specific questionnaires for urinary incontinence, FI, sexual dysfunctions, QoL in general or pain; 2) used adaptations or modifications of validated questionnaires (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Systematic presentation of methodology use and selection criteria.

To improve confidence in the selection of articles, the abstracts and full-text evaluation was conducted by two researchers in an independent and blinded way, strictly following the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In cases where there was disagreement over the selection of studies among the investigators, a third reviewer was consulted.

Strategy for analyzing selected articles

By the criteria described above, the articles were selected to compose this systematic review. The articles included in the review were evaluated according to a checklist to identify the following information: the PFD questionnaires used in each article, subjects, postpartum period of the assessment, other evaluation techniques used in data collection, article goal, and conclusion.

The validation studies of the questionnaires were found in the references, and the translated versions were searched in all databases of the research (PubMed databases, Virtual Health Library, Web of Science, and Scopus) without limitation of languages or date.

Results

The search of the databases resulted in 359 papers. Screening by title and abstract, 169 were excluded as duplicated titles and 19 as irrelevant to study purposes. The remaining articles were read in their entirety, and 138 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria; thus, 33 articles were selected to compose this systematic review (Figure 1).

The 33 articles were published between 2007 and 2018, and the following information were included in Table 1: authors and year of publication, study design, population studied (n), questionnaires used, other techniques used in data collection, objective, and conclusion of the studies.

Table 1.

Summary of articles selected by systematic review questionnaires used to evaluate PFDs in the postpartum period

| Author, year/study design | Population studied (n) | Questionnaire used | Other assessment methods | Article goal | Article conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Araujo et al, 201811/cross-sectional study | Primiparous women 12 and 24 months postpartum | ICIQ-VS | ICIQ-SF PFMS POP-Q US transperineal tomographic US imaging |

To evaluate PFM after different delivery modes | VD was associated with PFM avulsion. There was no difference among VD and nonelective or elective cesarean in symptomatology or other anatomic alterations evaluated through 3D/4D transperineal US |

| Lockhart et al, 201812/cohort study | Nulligravida women before pregnancy and 6 months postpartum (n=10) | PFDI-20 PFIQ-7 |

POP-Q dp3T MRI PFMS |

To prospectively characterize dp3T MRI findings in nulligravida women and characterize changes 6 months after delivery in the same woman | Dynamic pelvic 3 T MRI detected levator tears and increased pelvic organ descent, which can be directly attributed to pregnancy and delivery |

| Keshwani et al, 201813/cross-sectional study | Primíparas with DrA (n=32) | PFDI-20, PFIQ-7 |

Measure of IRD US transabdominal MBSR questionnaire – multidimensional body self-relations questionnaire VAS Oswestry Disability Index |

To investigate the relationship between IRD and symptom severity in women with DrA in the early postpartum period | This preliminary work suggests that, in the early postpartum period, IRD as a measure of DrA severity is meaningful for body image |

| Halperin et al, 201714/cohort study | Women sustained an OASIS 6 and 12 months postpartum (n=80) | PFBQ | Numerical scoring system to evaluate striae | To examine the association between the severities of SG and OASIS and to measure the symptoms regarding UI, fecal/flatus incontinence, and dyspareunia, at 6 and 12 months postpartum | The innovation of this research is the association between SG severity and OASIS severity (3A, 3B), added information regarding OASIS risk factors |

| Kruger et al, 201715/pilot study | Nulliparous women at third trimester of pregnancy and 5 months postpartum (n=167) | ICIQ-VS | ICIQ-SF ICIQ-BS Digital palpation by Dietz PFMS by Oxford US transperineal elastometry |

To quantify levator ani muscle stiffness during the third trimester of pregnancy and postpartum in European and Polynesian women. Associations between stiffness, obstetric variables, and the risk of intrapartum levator ani injury (avulsion) were investigated | Quantification of levator ani muscle stiffness is feasible. Muscle stiffness is significantly different before and after birth |

| Metz et al, 201716/cross-sectional study | Nulliparous women at third trimester of pregnancy, 6 months, and 1 year postpartum (n=233) | PFD questionnaire specific for pregnancy and postpartum | None | The aim of this study was to develop and validate a questionnaire for the assessment of pelvic floor disorders, their symptoms, and risk factors in pregnancy and after birth including symptom course, severity, and impact on QoL | This pelvic floor questionnaire proved to be valid, reliable, and reactive for the assessment of pelvic floor disorders, their risk factors, incidence, and impact on QoL during pregnancy and postpartum. The questionnaire can be utilized to assess the course of symptoms and treatment effects using a scoring system |

| Abdool et al, 201717/cohort study | Black South African primiparae women at third trimester, 3, and 6 months postpartum (n=84) | ICIQ-VS | POP-Q US transperineal |

To study delivery-related changes in pelvic floor morphology in Black South African primiparae. We also intended to determine the impact of anatomical changes on symptoms in the postpartum period | There is significant alteration in pelvic organ support and levator hiatal distensibility postpartum, with more marked effects in women after VD of black primiparous women, 15% sustained levator trauma after their first VD |

| Durnea et al, 201718/cohort study | Nullíparous at first trimester and 1 year postpartum (n=872) | FPFQ | None | To investigate the impact of the mode of delivery on postnatal PFD in primiparas, when PFD existing before the first pregnancy is taken into consideration | Prepregnancy PFD was common and was mainly associated with modifiable risk factors such as smoking and exercising. The main risk factor for postpartum PFD was the presence of similar symptoms prior to pregnancy, followed by anthropometric and intrapartum factors. Hip circumference seems to be a better predictor of PFD compared to BMI |

| Ng et al, 201719/cohort study | Women 3–5 years after delivery (n=506) | PFDI-46 PFIQ-31 |

POP-Q | To determine the prevalence of UI, FI, and POP 3–5 years after delivery | VD increases the risk for UI. Higher body weight and weight gain from first trimester are risk factors for SUI and UUI, respectively. More women reported symptoms of POP following an instrumental delivery than those who had a normal VD |

| Desseauve et al, 201620/cohort study | Women sustained an OASIS (n=159) | PFBQ | EuroQoL Pecatori grading system VAS |

To assess long-term pelvic floor symptoms after an OASI | Pelvic floor symptoms 4 years after OASI were highly prevalent |

| Yohay et al, 201621/cohort study | Israeli women at third trimester and 3 months postpartum (n=117) | PFDI-20 | None | To investigate the prevalence of PFD in women at late pregnancy and 3 months postpartum, to define changes in PFD rates, and to evaluate various obstetrical factors that may correlate with these changes | PFD is prevalent in both late pregnancy and the postpartum period. A significant association between perineal tears and SUI 3 months after delivery was noted |

| Kolberg Tennfjord et al, 201622/randomized clinical trial | Women 6 weeks after delivery (control) and 6 months after delivery (postintervention) (n=175) | ICIQ-VS | ICIQ FLUTSsex PFMS US transperineal (to evaluate LAM injury) |

Evaluate effect of PFMT on vaginal symptoms and sexual matters, dyspareunia, and coital incontinence in primiparous women stratified by major or no defects of the LAM | Women with a major defect of the LAM had the symptom “vagina feels loose or lax” compared to the control group. No difference was found between groups for symptoms related to sexual dysfunction |

| Gagnon et al, 201623/cohort study | Women 3 and 6 months postpartum (n=54) | PFDI-20 PFIQ-7 |

PFMS PISQ-12 |

Evaluate and measure changes in pelvic floor function in women who self-selected to attend a standardized one-on-one PFMT program with a physiotherapist following a group workshop | Results suggest that a two-tiered, self-selection approach to administering PFMT in the postpartum period contributes to significant improvements in pelvic floor function, QoL, and PFMS, and to high satisfaction rates |

| Cyr et al, 201624/cross-sectional study | Women 3 months postpartum (n=58) | ICIQ-VS PFIQ-7 | PF clinical examination US transperineal (PF morphometry) PFMS ICIQ-SF ICIQ-B |

Compare PFM morphometry and function in primiparous women with and without puborectalis avulsion in the early postpartum period and then compare the two groups for pelvic floor disorders and impact on QoL | PFM morphometry and function are impaired in primiparous women with puborectalis avulsion in the early postpartum period. Moreover, it highlights specific muscle parameters that are altered, such as passive properties, strength, speed of contraction, and endurance |

| Leeman et al, 201625/cohort study | Nulliparous in the beginning of pregnancy and 6 months postpartum (n=448) | PFIQ-7 | POP-Q PFMS Paper towel test Visual inspection of the perineum Assessment of the rectal sphincter strength |

To determine the effect of perineal laceration on pelvic floor outcomes, including UI, FI, perineal pain, and sexual function in a nulliparous cohort of women with a low incidence of episiotomy | Women having second-degree lacerations are not at increased risk for PFD other than increased pain, and slightly lower sexual function scores at 6 months postpartum |

| Tennfjord et al, 201526/cross-sectional study | Women 12 months after delivery (n=177) | ICIQ-VS | ICIQ FLUTSsex PFMS |

Investigate primiparous women 12 months postpartum and study (i) prevalence and bother of coital incontinence, vaginal symptoms, and sexual matters and (ii) whether coital incontinence and vaginal symptoms were associated with VRP, PFM strength, and endurance | Twelve-month postpartum coital incontinence was rare, whereas the prevalence of vaginal symptoms interfering with sexual life was more common. The large majority of primiparous women in the study had sexual intercourse at 12 months postpartum, and the reported overall bother on sexual life was low. Women reporting “vagina feels loose or lax” had lower VRP, PFM strength, and endurance when compared to women without the symptom |

| van Delft et al, 201527/cohort study | Primiparae women at 36 weeks gestation, 3 months, and 1 year postpartum (n=269) | ICIQ-VS | PFMS assessed by Oxford modified scale POP-Q US (to evaluate LAM injury) ICIQ-SF St Mark’s Incontinence Score |

To explore the natural history of levator avulsion in primipara 1 year postpartum and correlate this to PFD | Sixty-two percent of levator avulsions were no longer evident 1 year postpartum. Partial avulsion has a tendency to improve over time, which seems to be less common for complete levator avulsions. Women with no longer evident and persistent levator avulsion had PFD, with worse patterns in the presence of persistent avulsion |

| Fritel et al, 201528/randomized clinical trial | Nulliparous women at late pregnancy, 2 months, and 1 year postpartum (n=282) | FPFQ | POP-Q PAD-test 24 hours PFMS assessed by Laycock scale ICIQ-SF EuroQoL-5D |

To compare, in an unselected population of nulliparous pregnant women, the postnatal effect of prenatal supervised PFM training with written instructions on postpartum UI | Prenatal supervised pelvic floor training was not superior to written instructions in reducing postnatal UI |

| Lipschuetz et al, 201529/cross-sectional study | Women 12 months after delivery (n=198) | PFBQ | None | To investigate rates and range of PFD complaints, including anterior and posterior compartments and sexual function, in an unselected population of primiparous women 1 year from delivery, and to examine the degree of bother they cause | Two-thirds of women had symptoms of PFD 1 year after childbirth that caused some degree of discomfort. Women are willing to talk about PFD. Health professionals should take the initiative |

| Laterza et al, 201530/case–control study | Women immediately postpartum (up to 3 days) and 1 year after delivery (n=40) | FPFQ | US transperineal (to evaluate LAM injury) PFMS assessed by Oxford scale POP-Q |

Evaluate PFD and anatomical signs of POP in patients with levator LAM trauma compared with patients with an intact LAM 1 year postpartum | Except for urinary symptoms, LAM trauma was asymptomatic in nearly all patients 1 year postpartum. However, POP stage I involving multiple compartments occurred more frequently in LAM trauma patients than in controls |

| Rikard-Bell et al, 201431/cohort study | Women 6 months postpartum (n=766) | PFDI-20 | PISQ-12 | To investigate the relationship between perineal outcomes and postpartum PFD | This study shows a relationship between perineal outcome and PFD and suggests that an episiotomy is associated with the least morbidity because of symptoms of UI |

| van Delft et al, 201432/cohort study | Women at 36 weeks gestation and 3 months postpartum (n=269) | ICIQ-VS | PFMS POP-Q US (to evaluate LAM injury) ICIQ-SF St Mark’s Incontinence Score |

To establish the relationship between postpartum LAM avulsion and signs and/or symptoms of PFD | Twenty-one percent of women sustain LAM avulsion during their first VD, with significant impact on signs and symptoms of PFD |

| Rogers et al, 201433/cohort study | Women before 37 weeks gestation, immediately, and 6 months postpartum (n=782) | PFIQ-7 | POP-Q Paper towel test ISI QUID Wexner Fecal Incontinence Scale Present Pain Intensity Scale FSFI |

To compare pelvic floor function and anatomy between women who delivered vaginally vs those with cesarean delivery prior to the second stage of labor | VD resulted in prolapse changes and objective UI but not in increased self-report PFD at 6 months postpartum compared to women who delivered by cesarean delivery prior to the second stage of labor. The second stage of labor had a modest effect on postpartum pelvic floor function |

| Adaji et al, 201434/cross-sectional study | Women 9 weeks postpartum (n=90) | PFDI-20 | None | To investigate the occurrence and severity of pelvic floor symptoms during the postnatal period among Nigerian women | Pelvic floor symptoms are prevalent in the study population and could be a pointer to the quality of obstetric care available. Efforts need to be intensified to create awareness and build capacity to prevent and manage these symptoms, which could impact the QoL of affected women |

| Chan et al, 201435/cohort study | Primiparous women 8 weeks and 1 year postpartum (n=442) | PFDI-46 PFIQ-31 |

POP-Q US transperineal (to evaluate LAM injury) |

To evaluate the effect of LAM injury on pelvic floor disorders and health-related QoL in Chinese primiparous women during the first year after delivery | Seventy-nine percent of women who had LAM injury at 8 weeks after VD had persistent LAM injury at 12 months. LAM injury was associated with prolapse symptoms at 8 weeks after delivery and a higher POPDI general and Urogenital Distress Inventory obstructive subscale scoring. However, we are not able to confirm the association between LAM injury and SUI, UUI, mixed UI, and FI at 8 weeks or 12 months after delivery, or prolapse symptoms and PFDI or PFIQ scores at 12 months after delivery |

| Geller et al, 201436/cohort study | Women at 35–37 weeks gestation and 6 weeks postpartum (n=73) | PFDI-20 PFIQ-7 |

POP-Q US endoanal | To determine if shortened perineal body length (<3 cm) is a risk factor for ultrasound-detected anal sphincter tear at first delivery | A shortened perineal body length in primiparous women is associated with an increased risk of anal sphincter tear at the time of first delivery |

| Durnea et al, 201437/cohort study | Women at 15 weeks gestation and 1 year postpartum (n=872) | FPFQ | None | To investigate the association between prepregnancy and postnatal PFD in premenopausal primiparous women and the associated effect of mode of delivery | The main damage to the pelvic floor seems to occur in the majority of patients before first pregnancy, where first childbearing does not worsen prepregnancy PFD in the majority of cases. Pregnancy appears to affect more preexisting symptoms of urgency and urge incontinence comparing to stress incontinence. Cesarean section seems to be more protective against postnatal worsening of prepregnancy PFD compared to de novo onset pathology |

| Elenskaia et al, 201338/cohort study | Women at second quarter pregnancy, 14 weeks, 1 year, and 5 years postpartum (n=182) | ePAQ PF | POP-Q | To evaluate the changes of pelvic organ support, symptoms, and QoL after childbirth | Five years after childbirth the stage of prolapse worsened after VD but not after cesarean. However, there was no impact on prolapse symptoms or QoL. After VD, women were more likely to experience a worsening in general sex score, but no other difference in QoL measures |

| Crane et al, 201339/cohort study | Women 1 year after delivery (n=109) | PFDI-20 | FSFI questionnaire | To compare the prevalence and severity of pelvic floor symptoms and sexual function at 1 year postpartum in women who underwent either operative VD or cesarean delivery for second-stage arrest | In this sample of primiparous women with second-stage arrest, mode of delivery did not significantly impact pelvic floor function 1 year after delivery, except for bulge symptoms in the operative VD group and sexual satisfaction in the planned cesarean delivery group |

| Chan et al, 201240/cohort study | Primiparous women from first to third trimester of pregnancy, 8 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year postpartum (n=328) | PFDI-46 | None | To evaluate factors and their prevalence associated with UI and FI incontinence during and after a woman’s first pregnancy | The prevalence of SUI, UUI, and FI was 25.9%, 8.2%, and 4.0%, respectively, 12 months after delivery. VD, antenatal SUI, and UUI were associated with SUI; antenatal UUI and increasing maternal body mass index at the first trimester were associated with UUI Antenatal FI was associated with FI pregnancy, regardless of route of delivery and obstetric practice, had an effect on UI and FI |

| Tin et al, 201041/cross-sectional study | It does not specify the postpartum period (n=325) | PFDI-20 PFIQ-7 |

None | To determine the prevalence of anal incontinence in postpartum women following obstetrical anal sphincter injury and to assess QoL and prevalence of other pelvic floor symptoms | The prevalence of anal incontinence was 7.7% (formed stool), 19.7% (loose stool), and 38.2% (flatus). Average PFDI and PFIQ scores were significantly higher in the fourth-degree tear group |

| Geller et al, 200742/cross-sectional study | Women 6 and 8 weeks postpartum (n=44) | PFDI-20 PFIQ-7 |

MRI (to evaluate LAM injury) POP-Q |

To validate telephone-administered versions of two condition-specific QoL questionnaires: PFDI and PFIQ | Telephone application of these instruments is a reliable and accurate measurement of the impact of PFD and can facilitate clinical and epidemiologic research, reducing cost and improving access to research participants |

| Branham et al, 200743/cohort study | Women 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum (n=89) | PFIQ-31 | MRI (to evaluate LAM injury) POP-Q |

To assess postpartum changes in the LAM using MRI and relate these changes to obstetrical events and risk factors associated with PFD | Nulliparity did not guarantee a normal assessment of levator ani anatomy by our blinded reader, and frequency of injury in this series is somewhat greater than that previously reported for primiparas. Younger Caucasian primiparas had a better recovery at 6 months than older Caucasians. Subjects experiencing more global injury, in particular to the ileococcygeous, tended not to recover muscle bulk |

Abbreviations: 3D, three-dimensional; dp3T MRI, dynamic pelvic 3 T magnetic resonance imaging; DrA, diastasis recti abdominis; ePAQ-PF, electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire – Pelvic Floor; FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index; FI, fecal incontinence; FPFQ, Female Pelvic Floor Questionnaire; ICIQ-B, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Bowel; ICIQ-FLUTSsex, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Female Sexual Matters Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms; ICIQ-SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Short Form; Tract Symptoms; ICIQ-VS, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Vaginal Symptoms; IRD, interrectus distance; ISI, Incontinence Symptom Index; LAM, levator ani muscle; OASIS, obstetric anal sphincter injuries; PFBQ, Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire; PFD, Pelvic floor dysfunction; PFDI, Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory; PFIQ, Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire; PFDs, pelvic floor dysfunctions; PFM, pelvic floor muscle; PFMT, pelvic floor muscle training; PFMS, pelvic floor muscle strength; PISQ-12, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire; POP, pelvic organ prolapse; POPDI, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory; POP-Q, Pelvic Organ Prolapse – Quantification; QoL, quality of life; QUID, Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis; SG, striae gravidarum; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; UI, urinary incontinence; US, ultrasound; UUI, urgency urinary incontinence; VD, vaginal delivery; VRP, vaginal resting pressure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The instruments were applied in different periods of pregnancy and postpartum. One study initiated the follow-up before the pregnancy,12 and the postpartum period varied from 3 days30,33 up to 5 years.19,38

The questionnaires were used in different types of studies, including cohort,12,14,17–21,23,25,27,31–33,35–40,43 cross-sectional,11,13,16,24,26,29,34,41,42 pilot study,15 case–control,30 and randomized clinical trials.22,28

In total, we identified nine questionnaires used to assess PFDs in the postpartum period. The description of these questionnaires, frequency of use in the articles, and translated and validated versions for different languages are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characterization, frequency, and translated and validated versions of questionnaires identified for evaluation of PFD in the postpartum period

| Questionnaire/validation article/country | Domains – questions | Identified categories | Translation | Freq (%) | Articles in which the questionnaire was used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFDI-20/Barber et al, 200444 USA | Urinary – 6 POP – 6 Colorectal-anal – 8 |

Symptom Bother |

English,44,a Spanish,45 Greek,46 Swedish,47 Turkish,48 Brazilian Portuguese,49 Korean,50 French,51 Danish,52 Norwegian,53 Japanese,54 Afrikaans,55 Sesotho,55 Dutch,56 Tigrigna,57 Hebrew,58 Finnish59 | 10 (30.3%) | Lockhart et al, 201812 Keshwani et al, 201813 Yohay et al, 201621 Gagnon et al, 201623 Rikard-Bell et al, 201431 Adaji and Olajide, 201434 Geller et al, 201436 Crane et al, 201339 Tin et al, 201041 Geller et al, 200742 |

| PFIQ-7/Barber et al, 200444 USA | Urinary – 7 POP – 7 Colorectal-anal – 7 |

QoL | English,44,a Spanish,45 Greek,46 Swedish,47 Turkish,48 Brazilian Portuguese,49 Korean,50 French,51 Danish,52 Norwegian,53 Afrikaans,55 Sesotho,55 Dutch,56 Tigrigna,57 Hebrew,58 Finnish,59 Chinese60 | 9 (27.3%) | Gagnon et al, 201623 Cyr et al, 201624 Leeman et al, 201625 Rogers et al, 201433 Geller et al, 201436 Tin et al, 201041 Geller et al, 200742 Lockhart et al, 201812 Keshwani et al, 201813 |

| ICIQ-VS/Price et al, 200661 UK | Vaginal – 9 Sexual – 5 |

Symptom QoL Bother |

English,61,a German,62 Portuguese,63 Greek,64 Danish,65 Sinhala and Tamil (Sri Lanka)66 | 8 (24.2%) | Araujo et al, 201811 Kruger et al, 201715 Abdool et al, 201717 Kolberg Tennfjord et al, 201622 Cyr et al, 201624 Tennfjord et al, 201526 van Delft et al, 201527 van Delft et al, 201432 |

| FPFQ/Baessler et al, 201067 Baessler et al, 200968 Australia |

Bladder – 15 Bowel – 12 POP – 5 Sexual – 10 |

Symptom QoL Bother |

English,67,68,a German,69 French,70 Serbian71 | 4 (12.1%) | Durnea et al, 201718 Fritel et al, 201528 Laterza et al, 201530 Durnea et al, 201437 |

| PFDI-46/Barber et al, 200172 USA | Urinary – 28 POP – 16 Colorectal-anal – 17b |

Symptom Bother |

English,72,a Chinese,73 Spanish74 | 3 (9.1%) | Ng et al, 201719 Chan et al, 201435 Chan et al, 201240 |

| PFIQ-31/Barber et al, 200172 USA | Urinary – 31 POP – 31 Colorectal-anal – 31 |

QoL | English,72,a Chinese,73 Spanish74 | 3 (9.1%) | Ng et al, 201719 Chan et al, 201435 Branham et al, 200743 |

| PFBQ/Peterson et al, 201075 USA | Urinary – 5 POP – 1 Bowel – 2 Sexual – 1 |

Bother | English,75,a Turkish,76 Arabic,77 Portuguese78 | 3 (9.1%) | Halperin et al, 201714 Desseauve et al, 201720 Lipschuetz et al, 201529 |

| ePAQ-PF/Radley et al, 200579 UK | Urinary – 35 Bowel – 33 Vaginal – 22 Sexual – 28 |

Symptom QoL Bother |

English79,a | 1 (3%) | Elenskaia et al, 201338 |

| PFD in pregnancy and postpartum Metz et al, 201716 Germany | Bladder – 16 Bowel – 11 POP – 5 Sexual – 9 Postpartum – 9 |

Symptom QoL Bother |

German16,a | 1 (3%) | Metz et al, 201716 |

Notes:

Original version of the questionnaire.

In the PFDI-46 questionnaire, some questions are used in more than one domain.

Abbreviations: ePAQ-PF, electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire – Pelvic Floor; FPFQ, Female Pelvic Floor Questionnaire; ICIQ-VS, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Vaginal Symptoms; PFBQ, Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire; PFDI, Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory; PFIQ, Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire; POP, pelvic organ prolapse; QoL, quality of life.

The Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 (PFDI-20) and the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 (PFIQ-7)44 are the two most frequent questionnaires in the articles included in this review, being used in 30.3% and 27.3% of studies, respectively. They assess urinary symptoms, POP, and colorectal symptoms and have versions translated into 17 and 16 different languages, respectively.44–60

The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS)61 is the third most frequent questionnaire in this review, being used in 24.2% of the studies. It assesses vaginal symptoms, including POPs and sexual matters, and has versions translated into seven different languages.61–66 The Female Pelvic Floor Questionnaire (FPFQ)67,68 or Australian Questionnaire is the fourth most frequent in this review, being used in 12.1% of the studies. It assesses bladder, bowel, POP, and sexual domains, and has versions translated in three different languages.67–71

The other questionnaires (PFDI-46, PFIQ-31,72 Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire [PFBQ],75 electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire – Pelvic Floor [ePAQ-PF],79 and PFD in pregnancy and postpartum16) were used in less than 10% of the studies.

Discussion

Systematic review of the literature found 33 published articles using nine validated questionnaires for assessing PFDs in the postpartum period: PFDI-20, PFIQ-7, PFDI-46, PFIQ-31, ICIQ-VS, FPFQ (or Australian PFQ), PFBQ, ePAQ-PF, and PFD questionnaire specific for pregnancy and postpartum.

The most frequent questionnaires in our revision were PFDI-20, PFIQ-7, and ICIQ-VS, and probably this is due to ICIQ-VS being part of modular questionnaires of the International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI),80 and PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 were highly recommended (grade A) for the evaluation of symptoms and health-related QoL impact of POP by ICI. There is no questionnaire that is highly recommended to assess the PFD in a complete and integrated way by ICI.

The ICI is one of the consultations that are held under the auspices of the International Consultation on Urological Diseases and has a long-standing relationship with International Continence Society. The ICI aims to create an international consensus for evaluation of pelvic symptoms, recommending high-quality instruments, standardizing the evaluation of PFD and the impact on QoL, to guide professionals and researchers in the choice of instruments with universal application.80 The use of the same instrument for data collection by several researchers favors comparison between studies, allowing meta-analysis of the published results.9,80

Regarding the PFDI and PFIQ questionnaires, they were first created in longer versions with 46 and 31 questions, respectively, but because they were too long they became burdensome and time consuming, so the simplified version showed good correlation with the expanded versions, discouraging the use of PFDI-46 and PFIQ-31 versions.81

The PFDs include various symptoms, such as UI, FI, POP, sexual dysfunction, and vaginal symptoms, and could be investigated in an integrated model, because often the cause is the same.82

Voorham-van der Zalm et al83 said that PFDI-20, PFIQ-7, and ICIQ-VS are useful tools in research, but each one only assesses certain aspects of PFD and/or QoL. PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 have some questions that address vaginal symptoms, but without emphasis on sexual factors, and ICIQ-VS is not able to assess bladder and bowel functions. The literature provides several standardized questionnaires, but each one assesses certain domains of PFD, and they are specific to evaluate symptoms, QoL, and/or bothersome.80,82,83

Among the questionnaires included in this review, ePAQ-PF, FPFQ, and PFBQ can evaluate all these domains, but there are some limiting factors for wide use in literature.

The ePAQ-PF79 is an interactive, self-administered, computer-based questionnaire, developed for clinical practice and validated in primary and secondary care assessing four dimensions (urinary, intestinal, vaginal, and sexual) with symptoms identification, as well as quantifying degree of bother and impact on QoL. Indeed, the ePAQ-PF is not used extensively for reasons that include cost implications involved in purchasing an ePAQ license, and has no translated versions, limiting widespread use in researches.84

The PFBQ75 questionnaire was validated in 2010 with the proposal to create a concise questionnaire that could verify the presence and degree of discomfort of the PFD, allowing its use in both clinical practice and research. But the questions were not well distributed among the domains, because it contains only nine questions, with an emphasis on urinary symptoms (five questions) and only one question for POPs and one question for sexual functions. Another limiting factor is the existence of translated versions in only four languages (English, Turkish, Arabic, and Portuguese), with the Portuguese version just being published.

The FPFQ is a complete questionnaire that can assess all domains, besides addressing the perception of symptoms, the impact on QoL, and the degree of bother, validated in community-dwelling women for application by interview67 and for self-application.68 Both versions are composed of 42 questions distributed in four domains: bladder function (15 questions), bowel function (12 questions), POP symptoms (five questions), and sexual function (10 questions).

However, its use is still scarce, as it was introduced only recently in the scientific literature, originally developed and validated in the English language, with versions translated and adapted for application in German,69 French,70 and Serbian.71

The ICI recommendation also encourages researchers to the translation and validation of these instruments in different languages. The existence of translated and validated versions in several languages also corroborates the widespread use of these evaluation tools in research conducted around the world.80,85 This method makes it possible to compare results across studies, despite different languages and cultures because the data come from the same instrument. It also allows the study to be carried out on a larger scale with international participation.

None of these questionnaires described till now were developed to be specifically applied to postpartum women, and most questionnaires have been developed for use with general population or urology/gynecology patients with incontinence.

The PFD has been described during late reproductive period and the occurrence of worsening of symptoms among nonreproductive life. Risk factors such as overweight, obesity, life habits (smoking, sedentarism), age, parity, and mode of delivery have been shown as a health-related multifactorial risk that can be modified and interfered by the health care professionals.82,86 Indeed, the postpartum period is favorable and has been studied as an important period to early detection and early intervention.

Despite the generally high prevalence of postpartum PFD, the pelvic floor function is not routinely evaluated in health system.1,2,87 Therefore, the evaluation of an instrument capable of identifying the presence of these symptoms is useful for health promotion and prevention of comorbidities. Health instruments, such as PFD questionnaires, are developed to quantify the often-qualitative symptoms that are underreported and normally coexist and affect the QoL and productivity of many women.88 The questionnaires are used to identify and amplify early diagnosis and to assist the professionals in monitoring these symptoms, even when they are poorly perceived or not explained by the patients.89

Uniformity in obtaining symptoms and clinical complaints by professionals directs and enables evidence-based decision, allowing specialized societies to conduct behaviors and guide the management for PFD. It should be stressed that the health instruments established and recommended by societies, as well as the guidelines are fundamental in developing countries and in countries that adopt primary health care as the main access of patients.89

Furthermore, postpartum evaluation requires validated and preferred questionnaires that were designed for women during this period of life. Luthander et al90 believe that the greatest symptoms of PFD are related to the need of reviewing obstetric care. Thus, it serves as a tool for evaluating obstetric practices, allowing the identification of possible failures and the improvement in obstetric care.

Recently, Metz et al16 (2017) developed a questionnaire to assess PFDs in pregnancy and postpartum, and it is based on the German version of the FPFQ, with some modifications to access younger women. However, because this questionnaire is a recent addition to the field and only in German version, its usefulness has not yet been thoroughly analyzed in clinical practice and further research is necessary to evaluate its feasibility and accessibility.

Still, the ICI advises that researchers should use existing highly recommended or recommended questionnaires if possible as this aids comparison, and to reduce the increasing proliferation of questionnaires.80,85

This review assists health care professionals and researchers in choosing an assessment tool for postpartum PFDs and proposes standardization in the method of research and scientific work. For the choice of questionnaire, it is suggested to use those validated and recommended by the academic society for population surveys and clinical practice of primary health care.80,85

The assessment of postpartum PDF is necessary to identify these symptoms, avoiding the evolution of these disorders. The international literature reveals that PFD tools developed specifically for women in postpartum period still need to be better explored and developed, allowing early treatment and comprehensive approach by the gynecologist and health care providers.16,90 There is still no questionnaire that is highly recommended for this purpose by ICI.80,85 They encourage researchers to raise the standard of outcome assessment and trial methodology in these fields in the forthcoming years.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this systematic review was the choice of appropriate keywords for the evaluation of PFDs. The term used in the literature is Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, but it is registered in the MeSH as Pelvic Floor Disorders. The two descriptors were used according to the citations in the literature. In addition, different types of reporting biases may hinder the interpretation of systematic reviews. Other limitation was the exclusion of articles published in journals with restricted access being 14 titles excluded. Besides that, the research was focused on articles published in peer-reviewed journals, excluding reports and books.

Conclusion

The most frequently reported questionnaires in this review included PFDI-20, PFIQ-7, and ICIQ-VS and are recommended by ICI. In addition, the review identified a specific questionnaire, recently developed, to access PFD during pregnancy and postpartum.16

This review reveals that the questionnaires used to evaluate PFD during postpartum period are developed for the general population or urology/gynecology patients with incontinence and reinforce the paucity of highly recommended questionnaires designed for postpartum, in order to improve early and specific approach for this period of life.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Nygaard I. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dieter AA, Wilkins MF, Wu JM. Epidemiological trends and future care needs for pelvic floor disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(5):380–384. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker GJA, Gunasekera P. Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in developing countries: review of prevalence and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(2):127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1278–1283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groutz A, Rimon E, Peled S, et al. Cesarean section: Does it really prevent the development of postpartum stress urinary incontinence? a prospective study of 363 women one year after their first delivery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(1):2–6. doi: 10.1002/nau.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swift S, Woodman P, O’Boyle A, O’Boyle A, et al. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguilar VC, White AB, Rogers RG. Updates on the diagnostic tools for evaluation of pelvic floor disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29(6):1–464. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barber MD. Questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18(4):461–465. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Araujo CC, Coelho SS, Martinho N, Tanaka M, Jales RM, Juliato CR. Clinical and ultrasonographic evaluation of the pelvic floor in primiparous women: a cross-sectional study. Int Urogynecol J. 2018:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3581-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockhart ME, Bates GW, Morgan DE, Beasley TM, Richter HE. Dynamic 3T pelvic floor magnetic resonance imaging in women progressing from the nulligravid to the primiparous state. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(5):735–744. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3462-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keshwani N, Mathur S, Mclean L. Relationship between interrectus distance and symptom severity in women with diastasis recti abdominis in the early postpartum period. Phys Ther. 2018;98(3):182–190. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halperin O, Noble A, Balachsan S, Klug E, Liebergall-Wischnitzer M. Association between severities of striae gravidarum and Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injuries (OASIS) Midwifery. 2017;54:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruger JA, Budgett SC, Wong V, et al. Characterizing levatorani muscle stiffness pre- and post-childbirth in European and Polynesian women in New Zealand: a pilot study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(10):1234–1242. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metz M, Junginger B, Henrich W, Baeßler K. Development and validation of a questionnaire for the assessment of pelvic floor disorders and their risk factors during pregnancy and post partum. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(4):358–365. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdool Z, Lindeque BG, Dietz HP. The impact of childbirth on pelvic floor morphology in primiparous Black South African women: a prospective longitudinal observational study. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;29(3):369–375. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durnea CM, Khashan AS, Kenny LC, et al. What is to blame for postnatal pelvic floor dysfunction in primiparous women-Pre-pregnancy or intrapartum risk factors? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;214:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng K, Cheung RYK, Lee LL, Chung TKH, Chan SSC. An observational follow-up study on pelvic floor disorders to 3–5 years after delivery. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(9):1393–1399. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3281-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desseauve D, Proust S, Carlier-Guerin C, Rutten C, Pierre F, Fritel X. Evaluation of long-term pelvic floor symptoms after an obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) at least one year after delivery: a retrospective cohort study of 159 cases. Gynécologie Obstétrique & Fertilité. 2016;44(7–8):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yohay D, Weintraub AY, Mauer-Perry N, et al. Prevalence and trends of pelvic floor disorders in late pregnancy and after delivery in a cohort of Israeli women using the PFDI-20. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolberg Tennfjord M, Hilde G, Staer-Jensen J, Siafarikas F, Engh ME, Bø K. Effect of postpartum pelvic floor muscle training on vaginal symptoms and sexual dysfunction-secondary analysis of a randomised trial. BJOG. 2016;123(4):634–642. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gagnon LH, Boucher J, Robert M. Impact of pelvic floor muscle training in the postpartum period. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(2):255–260. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cyr M-P, Kruger J, Wong V, Dumoulin C, Girard I, Morin M. Pelvic floor morphometry and function in women with and without puborectalis avulsion in the early postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;216(3):274e1274.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leeman L, Rogers R, Borders N, Teaf D, Qualls C. The effect of perineal lacerations on pelvic floor function and anatomy at 6 months postpartum in a prospective cohort of nulliparous women. Birth. 2016;43(4):293–302. doi: 10.1111/birt.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tennfjord MK, Hilde G, Stær-Jensen J, Siafarikas F, Engh ME, Bø K. Coital incontinence and vaginal symptoms and the relationship to pelvic floor muscle function in primiparous women at 12 months postpartum: a cross-sectional study. J Sex Med. 2015;1212(4):994–1003. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Delft KW, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Inthout J, Kluivers KB. The natural history of levator avulsion one year following childbirth: a prospective study. BJOG. 2015;122(9):1266–1273. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fritel X, de Tayrac R, Bader G, et al. Preventing urinary incontinence with supervised prenatal pelvic floor exercises: a randomized controlled trial. Obs Gynecol. 2015;126(2):370–377. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipschuetz M, Cohen SM, Liebergall-Wischnitzer M, et al. Degree of bother from pelvic floor dysfunction in women one year after first delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;191:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laterza RM, Schrutka L, Umek W, Albrich S, Koelbl H. Pelvic floor dysfunction after levator trauma 1-year postpartum: a prospective case-control study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(1):41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rikard-Bell J, Iyer J, Rane A. Perineal outcome and the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction: a cohort study of primiparous women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54(4):371–376. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Delft K, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Schwertner-Tiepelmann N, Kluivers K. The relationship between postpartum levator ani muscle avulsion and signs and symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction. BJOG. 2014;121(9):1164–1172. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers RG, Leeman LM, Borders N, et al. Contribution of the second stage of labour to pelvic floor dysfunction: a prospective cohort comparison of nulliparous women. BJOG. 2014;121(9):1145–1154. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adaji SE, Olajide FM. Pelvic floor distress symptoms within 9 weeks of childbirth among Nigerian women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;174(1):54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan SSC, Cheung RYK, Yiu KW, Lee LL, Chung TKH. Effect of levator ani muscle injury on primiparous women during the first year after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(10):1381–1388. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2340-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geller EJ, Robinson BL, Matthews CA, et al. Perineal body length as a risk factor for ultrasound-diagnosed anal sphincter tear at first delivery. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(5):631–636. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durnea CM, Khashan AS, Kenny LC, Tabirca SS, O’Reilly BA. The role of prepregnancy pelvic floor dysfunction in postnatal pelvic morbidity in primiparous women. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(10):1363–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elenskaia K, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Scheer I, Onwude J. Effect of childbirth on pelvic organ support and quality of life: a longitudinal cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(6):927–937. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1932-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crane AK, Geller EJ, Bane H, Ju R, Myers E, Matthews CA. Evaluation of pelvic floor symptoms and sexual function in primiparous women who underwent operative vaginal delivery versus cesarean delivery for second-stage arrest. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(1):13–16. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827bfd7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan SSC, Cheung RYK, Yiu KW, Lee LL, Chung TKH. Prevalence of urinary and fecal incontinence in Chinese women during and after their first pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;24(9):1473–1479. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tin RY, Schulz J, Gunn B, Flood C, Rosychuk RJ. The prevalence of anal incontinence in post-partum women following obstetrical anal sphincter injury. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(8):927–932. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geller EJ, Barbee ER, Wu JM, Loomis MJ, Visco AG. Validation of telephone administration of 2 condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(6):632.e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Branham VG, Thomas J, Jaffe TA, et al. Levator ani abnormality six weeks after delivery persists at six months. Am J Obs Gynecol. 2007;197(1):65.e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Treszezamsky AD, Karp D, Dick-Biascoechea M, et al. Spanish translation and validation of four short pelvic floor disorders questionnaires. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(4):655–670. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1894-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grigoriadis T, Athanasiou S, Giannoulis G, Mylona S-C, Lourantou D, Antsaklis A. Translation and psychometric evaluation of the Greek short forms of two condition-specific quality of life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders: PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(12):2131–2144. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teleman PIA, Stenzelius K, Iorizzo L, Jakobsson ULF. Validation of the Swedish short forms of the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7), Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(5):483–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan PB, Sut N, Sut HK. Validation, cultural adaptation and responsiveness of two pelvic-floor-specific quality-of-life questionnaires, PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7, in a Turkish population. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;162(2):229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arouca MAF, Duarte TB, Lott DAM, et al. Validation and cultural translation for Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) and Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(7):1097–1106. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2938-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoo E-H, Jeon MJ, Ahn K-H, Bai SW. Translation and linguistic validation of Korean version of short form of pelvic floor distress inventory-20, pelvic floor impact questionnaire-7. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56(5):330–332. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2013.56.5.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Tayrac R, Deval B, Fernandez H, Marès P, Mapi Research Institute Development of a linguistically validated French version of two short-form, condition-specific quality of life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20) and (PFIQ-7) J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 2007;36(8):738–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Due U, Brostrøm S, Lose G. Validation of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 and the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 in Danish women with pelvic organ prolapse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(9):1041–1048. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teig CJ, Grotle M, Bond MJ, et al. Norwegian translation, and validation, of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) and the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(7):1005–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshida M, Murayama R, Ota E, Nakata M, Kozuma S, Homma Y. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the pelvic floor distress inventory-short form 20. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(6):1039–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1962-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henn EW, Richter BW, Marokane MMP. Validation of the PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 quality of life questionnaires in two African languages. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(12):1883–1890. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Utomo E, Blok BF, Steensma AB, Korfage IJ. Validation of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) in a Dutch population. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(4):531–544. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2263-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goba GK, Legesse AY, Zelelow YB, et al. Reliability and validity of the Tigrigna version of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory–Short Form 20 (PFDI-20) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 (PFIQ-7) Int Urogynecol J. 2018:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lowenstein L, Levy G, Chen KO, Ginath S, Condrea A, Padoa A. Validation of hebrew versions of the pelvic floor distress inventory, pelvic organ prolapse/urinary incontinence sexual function questionnaire, and the urgency, severity and impact questionnaire. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18(6):329–331. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827268fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mattsson NK, Nieminen K, Heikkinen AM, et al. Validation of the short forms of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7), and Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) in Finnish. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu L, Yu S, Xu T, et al. Chinese validation of the pelvic floor impact questionnaire short form. Menopause. 2011;18(9):1030–1033. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31820fbcbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Price N, Jackson SR, Avery K, Brookes ST, Abrams P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the ICIQ Vaginal Symptoms Questionnaire: the ICIQ-VS. BJOG. 2006;113(6):700–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Banerjee C, Banerjee M, Hatzmann W, et al. The German Version of the ‘ICIQ Vaginal Symptoms Questionnaire’ (German ICIQ-VS): An Instrument Validation Study. Urol Int. 2010;85(1):70–79. doi: 10.1159/000316337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tamanini JTN, Almeida FG, Girotti ME, Riccetto CLZ, Palma PCR, Rios LAS. The Portuguese validation of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS) for Brazilian women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19(10):1385–1391. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stavros A, Themistoklis G, Niki K, George G, Aristidis A. The validation of international consultation on incontinence questionnaires in the Greek language. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(7):1141–1144. doi: 10.1002/nau.22197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arenholt LTS, Glavind-Kristensen M, Bøggild H, Glavind K. Translation and validation of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS): the Danish version. Int Urogynecol J. 2018:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3541-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ekanayake CD, Pathmeswaran A, Herath RP, Perera HSS, Patabendige M, Wijesinghe PS. Validation of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS) in two south-Asian languages. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(12):1849–1855. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baessler K, O’Neill SM, Maher CF, Battistutta D. A validated self-administered female pelvic floor questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(2):163–172. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baessler K, O’Neill SM, Maher CF, Battistutta D. Australian pelvic floor questionnaire: a validated interviewer-administered pelvic floor questionnaire for routine clinic and research. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20(2):149–158. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0742-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baessler K, Kempkensteffen C. Validierung eines umfassenden Beckenboden-Fragebogens für Klinik, Praxis und Forschung. Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau. 2009;49(4):299–307. doi: 10.1159/000301098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deparis J, Bonniaud V, Desseauve D, et al. Cultural adaptation of the female pelvic floor questionnaire (FPFQ) into French. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(2):253–258. doi: 10.1002/nau.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Argirović A, Tulić C, Kadija S, Soldatović I, Babić U, Nale D. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Serbian version of the Australian pelvic floor questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(1):131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barber MD, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC. Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(6):1388–1395. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.118659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan SSC, Cheung RYK, Yiu AKW, Akw Y, et al. Chinese validation of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(10):1305–1312. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1450-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Omotosho TB, Hardart A, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, Kobak WH, Romero AA. Validation of Spanish versions of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ): a multicenter validation randomized study. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20(6):623–639. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peterson TV, Karp DR, Aguilar VC, Davila GW. Validation of a global pelvic floor symptom bother questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(9):1129–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doğan H, Özengin N, Bakar Y, Duran B. Reliability and validity of a Turkish version of the Global Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(10):1577–1581. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bazi T, Kabakian-Khasholian T, Ezzeddine D, Ayoub H. Validation of an Arabic version of the global Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121(2):166–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peterson TV, Pinto RA, Davila GW, Nahas SC, Baracat EC, Haddad JM. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the pelvic floor bother questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Radley SC, Jones GL, Tanguy EA, Stevens VG, Nelson C, Mathers NJ. Computer interviewing in urogynaecology: concept, development and psychometric testing of an electronic pelvic floor assessment questionnaire in primary and secondary care. BJOG. 2006;113(2):231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A. Incontinence. 5th. Paris: Plymouth: Health Publication; 2013. p. 428. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barber MD, Chen Z, Lukacz E, et al. Further validation of the short form versions of the pelvic floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and pelvic floor impact questionnaire (PFIQ) Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(4):541–546. doi: 10.1002/nau.20934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wall LL, Delancey JOL. The politics of prolapse: a revisionist approach to disorders of the pelvic floor in women. Perspect Biol Med. 1991;34(4):486–496. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1991.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Voorham-van der Zalm PJ, Berzuk K, Shelly B, et al. Validation of the pelvic floor inventories Leiden (PelFIs) in English. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(4):536–540. doi: 10.1002/nau.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mccooty S, Latthe P. Electronic pelvic floor assessment questionnaire: a systematic review. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(Sup18):S32–S37. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.Sup18.S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Avery KNL, Bosch JLHR, Gotoh M, et al. Questionnaires to assess urinary and anal incontinence: review and recommendations. J Urol. 2007;177(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Galhardo CL, Soares JM, Jr, Simões RS, Haidar MA, Rodrigues de Lima G, Baracat EC. Estrogen effects on the vaginal pH, flora and cytology in late postmenopause after a long period without hormone therapy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2006;33(2):85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.da Silva ATM, Menezes CL, de Sousa Santos EF, et al. Referral gynecological ambulatory clinic: principal diagnosis and distribution in health services. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0498-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bezerra IMP, Sorpreso ICE. Concepts and movements in health promotion to guide educational practices. Journal of Human Growth and Development. 2016;26(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buurman MBR, Lagro-Janssen ALM. Women’s perception of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction and their help-seeking behaviour: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(2):406–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luthander C, Emilsson T, Ljunggren G, Hammarström M. A questionnaire on pelvic floor dysfunction postpartum. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(1):105–113. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]