Abstract

Objectives

Anxiety and/or depression during pregnancy or year after childbirth is the most common complication of childbearing. Economic evaluations of interventions for the prevention or treatment of perinatal anxiety and/or depression (PAD) were systematically reviewed with the aim of guiding researchers and commissioners of perinatal mental health services towards potentially cost-effective strategies.

Methods

Electronic searches were conducted on the MEDLINE, PsycINFO and NHS Economic Evaluation and Health Technology Assessment databases in September 2017 to identify relevant economic evaluations published since January 2000. Two stages of screening were used with prespecified inclusion/exclusion criteria. A data extraction form was designed prior to the literature search to capture key data. A published checklist was used to assess the quality of publications identified.

Results

Of the 168 non-duplicate citations identified, 8 studies met the inclusion criteria for the review; all but one focussing solely on postnatal depression in mothers. Interventions included prevention (3/8), treatment (3/8) or identification plus treatment (2/8). Two interventions were likely to be cost-effective, both incorporated identification plus treatment. Where the cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained was reported, interventions ranged from being dominant (cheaper and more effective than usual care) to costing £39 875/QALY.

Conclusions

Uncertainty and heterogeneity across studies in terms of setting and design make it difficult to make direct comparisons or draw strong conclusions. However, the two interventions incorporating identification plus treatment of perinatal depression were both likely to be cost-effective. Many gaps were identified in the economic evidence, such as the cost-effectiveness of interventions for perinatal anxiety, antenatal depression or interventions for fathers.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016051133.

Keywords: health economics, mental healths, psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A prespecified protocol was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews.

The current evidence base was summarised and critically appraised using two approaches to minimise subjectivity.

The review was limited to English language studies, which may introduce bias and it is possible that some studies were not identified despite the comprehensive search strategy.

Background

Improving mental health is a priority for UK and international health policy; the Department of Health supports the notion that there can be ‘no health without mental health’.1–4 In the UK, policy specifically aims to improve the mental health of mothers5; this reflects the growing recognition of the potential intergenerational effects of mental illness.6

Anxiety and/or depression during pregnancy or in the first year after having a baby (perinatal anxiety and/or depression (PAD)) is experienced by around 20% of mothers in high-income countries.7 8 The gold standard for clinical diagnosis of PAD is a structured interview,9 typically conducted by a psychiatrist. The current recommendation in the UK is that at first contact with maternity services and in the weeks following childbirth healthcare professionals consider asking women the Whooley and two-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale case-finding questions.7 However, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)10 is the most frequently used instrument used to detect PAD in research settings,11 which has validated cut-off scores to identify antenatal and postnatal women likely to be experiencing PAD.12

PAD can have important implications for the life-course of mothers and children13; depression during pregnancy is strongly associated with both depression and anxiety following childbirth.14 15 Other important potential long-term considerations include developmental delays and behavioural problems for children and family instability.4 16 The lifetime societal burden of PAD and other perinatal mental health conditions is massive, estimated at £8.1 billion for all the babies born in a single year in the UK (almost 700 000 in 2016).13 17 This includes costs related to time off work, marriage breakdown and social support. Evidence suggests that the costs of improving perinatal mental health outcomes are likely to be outweighed by the benefits7 18; high-quality economic evidence is needed to identify the most efficient ways of doing so.

Systematic reviews of the evidence19–21 suggest that psychological therapy and/or antidepressant medication are effective at treating the symptoms of PAD for many women, which is reflected in current clinical guidance.7 However, less is known about the cost-effectiveness of treatments for PAD. A systematic review of literature published before July 2013 and relating to preventative interventions for perinatal depression concluded that midwifery redesigned postnatal care, a person-centred approach-based intervention and an interpersonal therapy-based intervention showed some evidence of cost-effectiveness but with considerable uncertainty.22 A recent report on the long-term cost-effectiveness of perinatal mental health interventions included a selective review of interventions, which had previously been found to be cost-effective and concluded that all of the interventions led to a long-term net monetary benefit from a societal perspective.18

Different perinatal mental health conditions often co-occur14 23 and in the UK there has been a move towards commissioning the healthcare services for conditions under this umbrella together. Furthermore, widely used screening instruments such as the EPDS10 were not designed to differentiate between different perinatal mental health conditions, which may mean that people with different (although related) conditions are treated with the same interventions. As such it is likely to be more relevant and useful to commissioners and researchers to present synthesised evidence from a broad range of interventions for PAD. There has not been a recent review which aimed to bring all of the economic evidence on preventative and treatment interventions for PAD into a single narrative.

This review sought to produce an up-to-date synthesis of current knowledge about the cost-effectiveness of interventions for the prevention or treatment of PAD. Particular objectives were to identify characteristics of potentially cost-effective interventions, gaps in current knowledge and important avenues for future research. In the UK, there has been a pledge to increase healthcare spending to improve maternal mental health and therefore decision makers need to know which interventions are likely to be cost-effective so that these vital funds are allocated efficiently.22 The aim of this review is to provide an evidence base that could potentially inform these decisions by bringing information from different sources together into a comprehensive and critically appraised summary with recommendations for commissioners and researchers.

Methods

A systematic literature search and narrative review was conducted to identify economic evaluations of interventions for PAD. The research questions addressed by this review were:

What are the characteristics of existing interventions for PAD that are likely to be cost-effective?

Where do the evidence and knowledge gaps indicate future research should be focused?

The review protocol was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews register of systematic reviews (CRD42016051133).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Explicit inclusion criteria were: (a) studies focusing on mothers and/or fathers experiencing or at risk of developing perinatal depression and/or anxiety, (b) any psychological, psychosocial and/or pharmacological intervention, (c) alternative interventions and usual care or placebo as comparators, (d) incremental assessment of cost-effectiveness. Previous systematic reviews were excluded but screened for additional references.

Literature search

Electronic searches were performed on the PsycINFO, MEDLINE, NHS economic evaluation database (EED) and NHS Health Technology Assessment database. An initial search was run in September 2016 which was updated in September 2017. The searches were restricted to English language publications from January 2000 onwards; changes in practice and resource use/costs over time mean that older references are less useful for decision making. Common search terms included words related to perinatal depression and/or anxiety and economic evaluation terms. Terms varied slightly according to database designs. The search strategies are reported in online supplementary table S1. The bibliographies of previously published systematic reviews18 22 were hand-screened for additional references to ensure all relevant papers were captured.

bmjopen-2018-022022supp001.pdf (467.5KB, pdf)

Study selection

Abstracts of studies were examined independently by two reviewers (EMC and GES) to determine whether each publication met the inclusion criteria. Both reviewers independently considered the full-text of identified publications to ensure that inclusion criteria were met. At each stage, any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and a consensus reached on which publications should progress to the data extraction stage.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Structured data extraction and quality assessment was undertaken, guided by the NHS EED handbook.24 A dual-purpose (data extraction and quality assessment) form was designed a priori (see online supplementary table S2) and used to extract information on study methodology, results, limitations, evidence gaps and quality. The quality of the studies was also assessed using a modified version of the Consensus Health Economic Criteria (CHEC)-list.25 The checklist and assessment results are included in online supplementary table S3. One reviewer (EMC) completed the data extraction process with half reviewed by the second reviewer (GES). No issues were identified which suggested that the second reviewer needed to review all data extracted.

Currency conversion and inflation

Costs were converted to Great British Pounds (£) at the average exchange rate for the cost year reported in the source study.26 All costs were inflated to 2015/2016 based on the Hospital and Community Health Services index.27 Exchange and inflation rates are reported in online supplementary table S4.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in this research.

Results

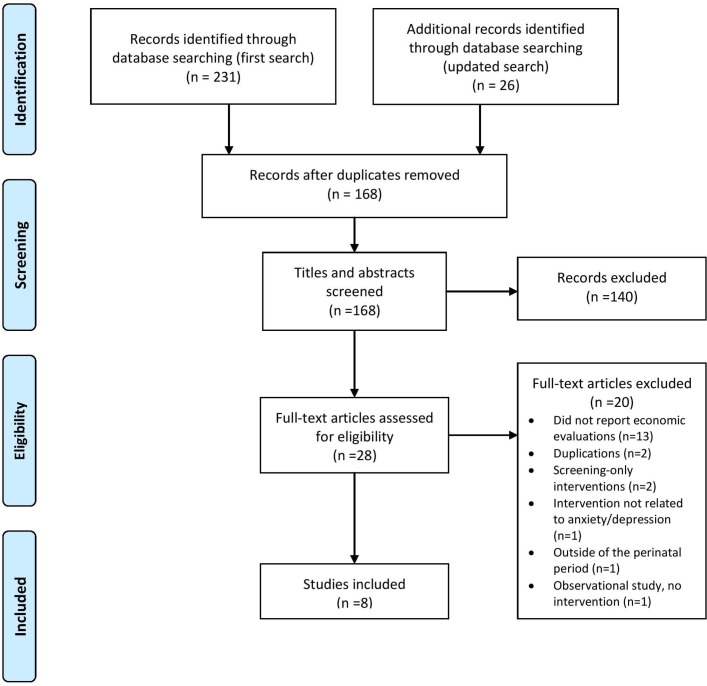

Initial searches identified 257 citations; following the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 168 citations were screened for eligibility (figure 1). Twenty-eight papers were included for full-text review, with eight papers were identified as relevant to the review (see online supplementary table S5 for details of excluded studies). The two systematic reviews that were hand-searched resulted in no additional references.18 22 Key characteristics of the eight included studies are described in table 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of studies identified.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies

| Study | Population | Country | Intervention (all studies reported usual or routine care as the comparator) |

| Boath et al 28 | Women being treated for postnatal depression n=60. | UK |

Treatment

Access to psychiatric day hospital, Monday–Friday 08:30–16:30, over 6 months. Day hospital was staffed by a multidisciplinary team of four psychiatric nurses, an occupational therapist, a nursery nurse, a lead psychiatric consultant, two clinical assistants and a senior registrar. |

| Petrou et al 29 | Women who were at high risk of developing postnatal depression at 26–28 weeks of gestation n=151. | UK |

Prevention

Counselling and support delivered by trained health visitors during home visits at 3, 7 and 17 days postdelivery, then weekly up to 8 weeks postnatally. |

| Morrell et al 30 | Women registered with participating general practitioner practices who became 36 weeks pregnant during the recruitment phase of the trial, had a live baby and were on a collaborating health visitor’s (HV) caseload for 4 months postnatally n=4084. | UK |

Screening and treatment

HV training in the assessment of postnatal women, combined with either cognitive behavioural approach or person-centred approach sessions (once per week for up to 8 weeks) for eligible women, plus the option of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor—commencing around 8 weeks postnatally. |

| Stevenson et al 31 | Women with postnatal depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale>12) n=not reported (model). | UK |

Treatment

Hypothetical group cognitive behavioural therapy (gCBT) intervention, one 2-hour session per week for 8 weeks, 4–6 women per group. |

| Dukhovny et al 35 | Any postpartum women in seven health regions across Ontario n=610. | Canada |

Prevention

Telephone-based volunteer lay/peer support—at least four phone calls starting 48–72 hours after randomisation and continuing through the first 12 weeks after birth. |

| Ride et al 34 | First-time mothers who had recently given birth and attended one of 48 participating Maternal and Child Health Centres n=359. | Australia |

Prevention

Psychoeducational programme targeted at the partner relationship, management of infant behaviour and parental fatigue, delivered as a one-off 6-hour session by nurses based at Maternal and Child Health Centres. |

| Grote et al 32 | Women at 12–32 weeks gestation, scoring 10 or higher on the PHQ-9 or with a diagnosis of probable dysthymia n=270. | USA |

Treatment

Collaborative care for depression including a choice of brief interpersonal psychotherapy (eight initial sessions plus maintenance sessions through baby’s first year), pharmacotherapy, or both, coordinated by Depression Care Specialists (master’s-level social workers) in collaboration with obstetric care providers. |

| Wilkinson et al 33 | Hypothetical cohort of pregnant women experiencing one live birth over 2 years n=1000. | USA |

Screening and treatment

Over first year post partum, general physicians screening for and treating postpartum depression and psychosis in partnership with a psychiatrist. |

Characteristics of studies

As shown in table 1, the earliest and largest number of included studies were from the UK (n=4),28–31 the most recent two studies were from the USA32 33 and there was one study from each of Australia34 and Canada.35

The interventions evaluated across the eight studies were diverse and no two studies evaluated comparable interventions. Three studies included a preventative intervention,29 34 35 three focused on treatment28 31 32 and two included complex interventions incorporating both identification and treatment.30 33 All studies focused on postnatal depression in mothers, although the study by Ride et al did also consider anxiety in mothers and the mental health of fathers in the perinatal period.34 Two of the preventative interventions were targeted at distinct groups: high risk women29; first time mothers.34 One intervention involved lay or peer support,35 two were delivered by health visitors29 30 and the remainder were delivered across a range of settings/healthcare professionals/structures including collaborative care32 33 and group cognitive behavioural therapy (gCBT).31 The comparator intervention for all studies was described as usual or routine care. Usual care is likely to vary by setting which affects the external validity of the study.

The majority (n=6) of studies reported cost-effectiveness analyses with different measures of health benefits, which makes it difficult to compare between studies.28 29 32–35 The most widely used (primary or secondary) measure of health benefit was the EPDS, which was reported in two of the six trial-based studies.30 35 Cost-utility analyses were reported in four studies, making results across these studies easier to compare30 31 33 34 (two of which had also reported cost-effectiveness33 34). Utility was derived from the Short Form-Six Dimension (SF-6D) in two studies30 31 and from the EuroQoL-Five Dimension (EQ-5D) in two studies.33 34 Only two studies reported the results of an economic models31 33 with the remainder reporting trial-based results.

Critical appraisal

A copy of the CHEC quality appraisal checklist and assessment results are included in online supplementary table S3.25 The median score was 15.5 (out of 18). The majority of the studies were of high quality (n=6)29–31 33–35 and two were average.28 32 The studies published prior to 2006 did not report results of incremental analysis but there is a trend towards more robust methods and reporting over time. Overall, the studies reported the population, setting, intervention and comparator well. Two studies had relatively short time horizons (12 weeks35 and 20 weeks34), which may not reflect the potentially long-lasting course of PAD. Six of the studies reported sensitivity or subgroup analyses,29–31 33–35 demonstrating varying levels of uncertainty around their primary cost-effectiveness estimate. Not reporting uncertainty is an important limitation in economic evaluations because it indicates confidence in the results, analogous to not reporting a CI for a statistical analysis. Four of the studies did not report whether there were any conflicts of interest.29 31 33 35

Factors which increased the potential for bias in the reported results include non-randomised treatment allocation28 and an imbalance in data completeness between treatment groups/subgroups.32 The study by Dukhovny et al was particularly robust owing to a high level of data completeness.35

The model by Stevenson et al evaluating group CBT to treat postnatal depression in the UK was informed by expert opinion alongside published data available from randomised controlled trials for EPDS and SF-6D scores31 (table 2). The model structure was not explicitly reported. The model by Wilkinson et al evaluating collaboration between general practitioners (GPs) and psychiatrists to identify and treat postnatal depression included estimates for the EPDS and EQ-5D from published literature.33 Some of the model parameters were from studies of anxiety/depression outside of the perinatal period and the model structure, although pragmatic potentially oversimplified suicide risk (table 2). Both model-based evaluations reported probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Table 2.

Design of included studies

| Study | Evaluation type | Measure of health benefit | Evaluation details | Data source | Quality/bias considerations |

| Boath et al 28 | CEA | Recovery from PND (no longer fulfilling Research Diagnostic Criteria) |

|

Observational study—healthcare utilisation self-reported and obtained from medical records | Treatment allocation was non-randomised. Reported that no significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics or outcome measures between groups at baseline. No loss to follow-up reported. |

| Petrou et al 29 | CEA | Months of postnatal depression avoided (SCID-II) |

|

RCT—health and social care utilisation was self-reported by participants | Structured clinical interviews were used to identify depression in both treatment groups. The numbers/characteristics of those declining to participate were not reported. |

| Morrell et al 30 | CUA |

|

|

RCT—health and social care utilisation obtained from medical records (up to 6 months) and participant self-report (at 12 and 18 months) | Data were collected on women declining to take part but differences with sample were not discussed. Sample was broadly representative of general population. Missing economic data were significant at 12 and 18 months, 6 months was used as the primary time horizon. |

| Stevenson et al 31 | CUA | QALYs (derived from EPDS mapped onto SF-6D) |

|

Published data sources and expert opinion informed the model. EPDS, SF-36 and costs from published RCTs | As the model was mathematical, no structure was reported in the paper. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted. |

| Dukhovny et al 35 | CEA | Cases of PND averted at 12 weeks post partum |

|

Multiregion RCT—resource utilisation was self-reported by participants | Only two people did not complete healthcare utilisation questionnaires and fewer than 0.01% of individual resource utilisation items were missing at random. |

| Ride et al 34 | CEA; CUA |

|

|

Cluster RCT—health and social care utilisation self-reported by participants | Differences between the treatment groups were adjusted for in the analysis. The intracluster coefficients were small but non-negligible for QALYs, which may have reduced the ability to detect an effect of the intervention. |

| Grote et al 32 | CEA |

|

|

RCT—health and social care utilisation self-reported by participants | The costs included only related to mental healthcare. The perspective was ’public health' and so could have also included primary and community healthcare services. Those with partial cost data (n=12/164) were more likely to have probable PTSD and to have been randomly assigned to the intervention. |

| Wilkinson et al 33 | CEA; CUA |

|

|

Systematic review of existing literature to inform the model. Some cost parameters estimated from Medicaid data | Some parameters were from studies of anxiety/depression outside of the perinatal period. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted. The model structure is pragmatic, but perhaps over simple in terms of suicide risk—only women who discontinue treatment are at risk of suicide, women who do not seek help or those who screen negative are not deemed to be at risk of suicide. |

CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CEA, cost-effectiveness analysis; CUA, cost-utility analysis; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SCID-II, Structured Clinical Interview for Depression, second edition; SCL-20, 20-item Symptom Checklist Depression Scale.

Cost-effectiveness

Six studies reported incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), half of which were in terms of clinical outcomes28 29 35 and half in terms of QALY gains associated with the intervention compared with usual care.31 33 34 Two interventions were either likely or highly likely to be cost-effective, both incorporating identification plus treatment of postnatal depression: health visitor screening and counselling30; GP/psychiatrist collaborative screening and treatment.33 The intervention involving health visitors was associated with lower costs and better outcomes than usual care, therefore the authors did not report an ICER because the intervention dominated usual care. However, when multiple imputation was used to resolve missing data (rather than a complete case analysis), the intervention was associated with more QALYs and a net cost resulting in an ICER of £15 666/QALY.

Three interventions (psychiatric day hospital (treatment),28 health visitor counsellors (prevention) and29 telephone-delivered peer support (prevention)35) were classified as possibly cost-effective because although they reported improved health outcomes with increased costs, there is no accepted threshold by which to judge ICERs when health benefits are quantified as anything other than QALYs. The ICER reported for psychiatric day hospital care was sensitive to the inclusion of primary care and medication costs, increasing from £3843 to £56 865 per additional recovery.28 Psychoeducation (prevention)34 was classified as possibly cost-effective because although following currency conversion the QALY-based ICER was below the UK threshold for cost-effectiveness, the authors reported a 55% chance (ie, not much higher than chance) that it was below the Australian threshold. Furthermore, the ICER value increased by £5055 following multiple imputation. Collaborative care (treatment)32 was classified as possibly cost-effective because of conflicting results for subgroup analyses (table 3). The cost-benefit analysis valued a depression-free day at US$20 (approximately £13),32 which translated to a net benefit among mothers with PTSD and a net cost for mothers without PTSD. Group CBT was evaluated as unlikely to be a cost-effective treatment for post-natal depression.31

Table 3.

Cost-effectiveness results

| Study | Interventions | Net benefit | Net cost | ICER, key conclusions and uncertainty |

| Boath et al 28 | Psychiatric day hospital vs routine primary care | 14 more women recovered in the intervention group. | The intervention was £53 824 (p<0.001) more expensive than routine care. | £3843 per each additional recovery. The net cost is sensitive to inclusion primary care and medication costs, increasing to £56 865. Possibly cost-effective |

| Petrou et al 29 | Counselling and support from health visitors vs usual care | The intervention group depressed for 2.14 weeks fewer (over 18 months) than the control group—this was not statistically significant (p=0.41). | The intervention group costs were £189 higher, although this was not significant (95% CI −£843 to £1237). |

£68 per month of depression avoided. Possibly, a small improvement in outcomes for a small cost. Possibly cost-effective |

| Morrell et al 30 |

Screening and talking therapy (CBA or PCA) delivered by health visitor vs usual care | EPDS score at 6 months was 0.9 lower (p<0.001) for those randomised to an intervention group. QALY gain of 0.002 (95% CI −0.001 to 0.005) associated with the intervention. | There was a non-significant net-saving of £26 (95% CI −£100 to £47) for women in the intervention groups. | Improved outcomes with comparable costs. No ICER reported because of negative net cost. CBA appears to be more cost-effective than PCA. Subgroup analysis of ’at-risk' women: 6-month EPDS score 2.1 lower (p=0.002). Analysis of imputed data: QALY gain increased to 0.003 (95% CI 0.001 to 0.006) and net cost saving increased to £47 (95% CI −£68 to −£4), both reaching statistical significance (£15 666/QALY). Highly likely to be cost-effective |

| Stevenson et al 31 |

Group CBT vs usual care | Intervention associated with a QALY gain of 0.039 (PSA results). | £1568 net cost of providing gCBT (PSA results). | £39 875 per QALY gained. Intervention is not likely to be cost-effective at accepted thresholds. More research is needed to address the level of uncertainty. Not likely to be cost-effective |

| Dukhovny et al 35 |

Telephone-based peer support vs usual care | 0.1116 more cases of postnatal depression avoided at 12 weeks in the intervention group. | £755 net cost associated with intervention (p<0.001). | £6768 per case of postnatal depression avoided. The ICER is within the range of other postnatal depression interventions. Possibly cost-effective |

| Ride et al 34 |

Psychoeducational programme vs usual care | Comparable outcomes both in terms of prevalence of mental health conditions (p=0.883) and QALYs (p=0.967). | £167 net cost associated with the intervention, although this was not statistically significant (p=0.333). | £21 987/QALY; £92 per %-point reduction in 30-day prevalence of postnatal mental health disorders. The probability the intervention if cost-effective is 0.55 at a willingness to pay threshold of A$ 55 000 (approximately £30 000–£35 000)—more research is needed to reduce uncertainty. Multiple imputation of missing data increased ICER to £27 042/QALY. Possibly cost-effective |

| Grote et al 32 |

Collaborative care for depression vs usual care | More depression-free days over 18 months for the intervention group:

|

Significant net cost associated with the intervention:

|

If a depression-free day is valued at US$20 (approximately £13):

|

| Wilkinson et al 33 |

Psychiatrist-supported general practitioner screening and treating postpartum depression and psychosis | 29 more healthy women in the intervention group, equating to a total of 21.43 additional QALYs over 2 years. | Total additional cost associated with the intervention £185 173. | £8642 per QALY gained, £6350 per remission achieved, £588 per additional healthy woman. Likely to be cost-effective |

Currency conversion and inflation rates used are reported in online supplementary table S4.

CBA, cognitive behavioural approach; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PCA, person-centred approach; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Discussion

Eight studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of interventions for PAD were included in this review. All were published between 2006 and 2017. Six studies were high quality and two average quality. Each study focused on depression occurring in postnatal mothers (although Ride et al also considered anxiety and fathers34), but evaluated a different type of intervention, some of which focused on prevention and others focused on treatment (or identification plus treatment). Two studies identified interventions that were likely to be cost-effective, both of which incorporated identification plus treatment of postnatal depression.

The quality of the studies included in the review was mixed and generally increased over time, which is likely to reflect the agreement of standards for the reporting of economic evaluations. The use of a standardised checklist, such as the commonly used Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards checklist for the reporting of economic evaluations,36 would facilitate the synthesis of data in future reviews. In order to meaningfully compare studies, the most critical information required is: a full description of the intervention and comparator, inclusion/exclusion criteria, time horizon and perspective of the evaluation, the net outcome, the net cost, ICER and cost-effectiveness acceptability (reported as the likelihood an intervention is cost-effective at appropriate willingness to pay thresholds) and summary of uncertainty.

QALYs are the most widely used measure of health benefit in economic evaluations, as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).37 Interventions costing <£20 000–£30 000 per QALY gained (vs the comparator intervention) are considered to be cost-effective. Only four of the included studies reported results in terms of QALYs. Standardised methods for economic evaluations are important so that results can be directly compared, for example, it may not always be appropriate to compare QALYs derived using different approaches.38 NICE recommends that the EQ-5D is used to derive QALYs; two of the studies included derived QALYs from the SF-6D39 and the other two studies derived QALYs from the EQ-5D.40

There was great heterogeneity between the studies included in terms of the interventions, measure of benefit and time horizon. However, the interventions could be grouped by some characteristics such as their aim (eg, prevention or treatment) or key actors (eg, healthcare professional or peer support). There were inconsistent findings within the intervention subgroups with one exception. The two studies which incorporated identification plus treatment were both likely to be cost-effective.30 33 However, the two interventions were very different. The intervention evaluated by Morrell et al involved training health visitors to identify women experiencing postnatal depression and deliver talking therapy (using either a cognitive behavioural approach or a person-centred approach), whereas the intervention evaluated by Wilkinson et al was based around collaboration between GPs and psychiatrists. Due to a large amount of missing data, the health visitor intervention was only evaluated at 6 months, whereas the collaborative intervention was evaluated at 2 years. This also makes it difficult to compare results between studies because it is possible that over a longer follow-up more benefits are accrued.

Strengths and limitations

There are a number of strengths and limitations of this review. Multiple major literature databases relevant to health and economic research were searched, therefore it is likely that key studies incorporating the search terms have been identified. In the instance where a full text was not available online, the authors were contacted and provided a copy. The search was however restricted to English language studies, introducing some bias. Searches were also restricted to published journal articles, which are less likely to include inconclusive or negative cost-effectiveness results when compared with the grey literature.41 The exclusion of studies published prior to the year 2000 may also have introduced bias; however, a post hoc search of the NHS EED database returned no relevant studies from before this time.

Despite a robust search strategy, there may be relevant studies that were not identified by this review. For example, the definition of the perinatal period adopted by researchers (from conception up to 4 weeks,42 6 weeks43 or 12 months post partum7) will influence whether interventions for PAD are described as ’perinatal' or ’early childhood'. After this review was completed, a paper was brought to the authors' attention that involved an intervention for depression in mothers in the first year post partum. However, as it was described as an ’early childhood programme' and was not explicitly referred to as an intervention for postnatal or postpartum depression, it was not identified in this search.44 The intervention (in-home CBT) was nested within a complex home-visiting support programme, which aimed to improve the health and well-being of low-income parents and babies, which was the ’standard care' comparator in the economic evaluation. The study reported the results of an economic model that extrapolated the results from an RCT and concluded that in-home CBT was likely to be cost-effective compared with this standard care as a treatment for depression.

Two separate tools were used to critically appraise the studies which included more criteria and gave a broader perspective than a single approach, although one was developed specifically for this review and not formally validated. The CHEC-list45 was used to assign a score to each study and the data extraction tool was used to identify potential sources of bias. Both approaches involve an element of subjectivity, the CHEC-list attempts to handle this by not classing a criteria as having been met if it is only partially met, however this may result in some loss of sensitivity.

Future research

One study which was excluded from this review because it focused only on screening for postnatal depression concluded that it was not cost-effective to screen because of increased treatment costs.46 However, identification and treatment are inextricably linked and evaluating them separately may not tell the whole story, which should be borne in mind for future research. It is also necessary to address the lack of economic evidence for interventions for antenatal depression, perinatal anxiety and PAD in fathers as these conditions are also prevalent and may be associated with negative outcomes for individuals and families.47–49 Future economic evaluations should be conducted and reported according to good practice guidelines so that future reviews can make clear recommendations to inform health policy.

Conclusion

Heterogeneity in the evaluations to date means that it is not possible to make any conclusions about their relative cost-effectiveness, with no clear implications for health policy. However, the two interventions that were likely to be cost-effective (compared with usual care) both incorporated identification and treatment together; this appears to be the most fruitful direction for future research and could inform perinatal mental health service strategy. As recognition of the incidence of perinatal anxiety in mothers, and all PAD conditions in fathers, grows so does the need for relevant and robust economic evidence, therefore this is also a recommended area for future research. The quality of the methods and reporting of economic evaluations for interventions related to PAD has improved over time, but it is important that new studies adhere to reporting guidelines that will facilitate future evidence synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EMC and GES conducted the literature search and data extraction. EMC wrote the first draft of the manuscript with contribution from GES to the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Search strategies and data extraction templates are available in the supplementary material. No other unpublished data from the study are available.

References

- 1. Department of Health, HM Government. No health without mental health: a cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. London: Stationery Office, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organisation. Draft Mental Health Action Plan: An Overview. 2012. http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/2_11_2012_Saxena.pdf.

- 3. Committee AHDMP. Fourth National Mental Health Plan: an agenda for collaborative government action in mental health 2009-2014. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mental Health Taskforce to the NHS. The five year forward view for mental health. London: Mental Health Taskforce to the NHS, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Department of Health. Prime Minister pledges a revolution in mental health treatment. 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-pledges-a-revolution-in-mental-health-treatment.

- 6. Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev 1999;106:458–90. 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance (CG 192). 2014. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG192. [PubMed]

- 8. Goodman JH, Tyer-Viola L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Womens Health 2010;19:477–90. 10.1089/jwh.2008.1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:624–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. development of the 10-item edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hewitt C, Gilbody S, Brealey S, et al. Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: an integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:1-145, 147-230 10.3310/hta13360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matthey S, Henshaw C, Elliott S, et al. Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: implications for clinical and research practice. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9:309–15. 10.1007/s00737-006-0152-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bauer A, Knapp M, Parsonage M. Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord 2016;192:83–90. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roomruangwong C, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, et al. Antenatal depression and hematocrit levels as predictors of postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms. Psychiatry Res 2016;238:211–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stewart DE, Robertson E, Dennis CL, et al. Postpartum depression: Literature review of risk factors and interventions. Toronto Univ Heal Netw Women’s Heal Progr Toronto Public Heal 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tammentie T, Tarkka MT, Astedt-Kurki P, et al. Family dynamics and postnatal depression. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2004;11:141–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2003.00684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Office for National Statistics. Births in England and Wales: 2016. London: Office for National Statistics, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bauer A, Knapp M, Adelaja B. Best practice for perinatal mental health care: the economic case. London: Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Molyneaux E, Howard LM, McGeown HR, et al. Antidepressant treatment for postnatal depression. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2014;20:368 10.1192/apt.20.6.368 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dennis CL, Ross LE, Herxheimer A. Oestrogens and progestins for preventing and treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;4:CD001690 10.1002/14651858.CD001690.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dennis CL, Hodnett E. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;4:2007–9. 10.1002/14651858.CD006116.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morrell CJ, Sutcliffe P, Booth A, et al. A systematic review, evidence synthesis and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness, the cost-effectiveness, safety and acceptability of interventions to prevent postnatal depression. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–414. 10.3310/hta20370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Letourneau NL, Dennis CL, Benzies K, et al. Postpartum depression is a family affair: addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and children. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2012;33:445–57. 10.3109/01612840.2012.673054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) Handbook. 2007. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst//%0Acrd/pdf/nhseed-handbook2007.pdf.

- 25. Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, et al. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria The authors thank the following persons for their participation in the Delphi panel. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:240–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. OFX. Historical Currency Exchange Rates. 2017. https://www.ofx.com/en-gb/forex-news/historical-exchange-rates/yearly-average-rates/ (accessed 21 Sep2017).

- 27. Curtis L, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care. 2015.

- 28. Boath E, Major K, Cox J. When the cradle falls II: The cost-effectiveness of treating postnatal depression in a psychiatric day hospital compared with routine primary care. J Affect Disord 2003;74:159–66. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petrou S, Cooper P, Murray L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a preventive counseling and support package for postnatal depression. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2006;22:443–53. 10.1017/S0266462306051361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morrell C, Warner R, Slade P, et al. Psychological interventions for postnatal depression: cluster randomised trial and economic evaluation. The PoNDER trial. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:1–153. 10.3310/hta13300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stevenson MD, Scope A, Sutcliffe PA. The cost-effectiveness of group cognitive behavioral therapy compared with routine primary care for women with postnatal depression in the UK. Value Health 2010;13:580–4. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grote NK, Simon GE, Russo J, et al. Incremental Benefit-Cost of MOMCare: Collaborative Care for Perinatal Depression Among Economically Disadvantaged Women. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68:1164–71. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilkinson A, Anderson S, Wheeler SB. Screening for and Treating Postpartum Depression and Psychosis: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Matern Child Health J 2017;21:903–14. 10.1007/s10995-016-2192-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ride J, Lorgelly P, Tran T, et al. Preventing postnatal maternal mental health problems using a psychoeducational intervention: the cost-effectiveness of What Were We Thinking. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012086 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dukhovny D, Dennis CL, Hodnett E, et al. Prospective economic evaluation of a peer support intervention for prevention of postpartum depression among high-risk women in Ontario, Canada. Am J Perinatol 2013;30:631–42. 10.1055/s-0032-1331029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Eur J Health Econ 2013;14:367–72. 10.1007/s10198-013-0471-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brazier J, Roberts J, Tsuchiya A, et al. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Econ 2004;13:873–84. 10.1002/hec.866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 2002;21:271–92. 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The EuroQoL Group. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bell CM, Urbach DR, Ray JG, et al. Bias in published cost effectiveness studies: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:699–703. 10.1136/bmj.38737.607558.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Virginia: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Int Classif 1992;10:1–267. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ammerman RT, Mallow PJ, Rizzo JA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of In-Home Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for low-income depressed mothers participating in early childhood prevention programs. J Affect Disord 2017;208:475–82. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grochtdreis T, Brettschneider C, Wegener A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of depressive disorders in primary care: a systematic review. PLoS One 201517;10:e0123078 10.1371/journal.pone.0123078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Paulden M, Palmer S, Hewitt C, et al. Screening for postnatal depression in primary care: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2009;339:b5203 10.1136/bmj.b5203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Biebel K, Alikhan S. Paternal postpartum depression. J Parent Fam Ment Hea 2016;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs 2004;45:26–35. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leach LS, Poyser C, Fairweather-Schmidt K. Maternal perinatal anxiety: a review of prevalence and correlates. Clin Psychol 2015;1:16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022022supp001.pdf (467.5KB, pdf)