Abstract

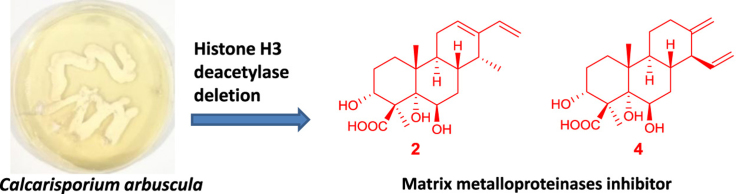

Epigenetic modifications have been proved to be a powerful way to activate silent gene clusters and lead to diverse secondary metabolites in fungi. Previously, inactivation of a histone H3 deacetylase in Calcarisporium arbuscula had led to pleiotropic activation and overexpression of more than 75% of the biosynthetic genes and isolation of ten compounds. Further investigation of the crude extract of C. arbuscula ΔhdaA strain resulted in the isolation of twelve new diterpenoids including three cassanes (1−3), one cleistanthane (4), six pimaranes (5−10), and two isopimaranes (11 and 12) along with two know cleistanthane analogues. Their structures were elucidated by extensive NMR spectroscopic data analysis. Compounds 2 and 4 showed potent inhibitory effects on the expression of MMP1 and MMP2 (matrix metalloproteinases family) in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells.

KEY WORDS: Calcarisporium arbuscula, Calcarisporic acids, Pimarane, Diterpenoid, Matrix metalloproteinases inhibitor, Epigenetic genome mining

Graphical abstract

Epigenetic modifications have been proved to be a powerful technique to activate silent gene clusters and had led to diverse secondary metabolites in fungi. Investigation of the crude extract of Calcarisporium arbuscula ΔhdaA strain, in which a histone H3 deacetylase was deleted, resulted in the isolation of twelve new diterpenoids including three cassanes (1−3), one cleistanthane (4), six pimaranes (5−10), and two isopimaranes (11−12). Compounds 2 and 4 showed potent inhibitory effects on the expression of MMP1 and MMP2 (matrix metalloproteinases family) in human breast cancer cells.

1. Introduction

Calcarisporium arbuscula, an endophytic fungus lives in the flesh of healthy fruit-bodies of mushrooms1, mainly produces the adenosine triphosphate synthase inhibitors aurovertins B and D, which structurally contain a 2,6-dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]-octane ring2, 3, 4. In our prior genome mining investigation5, genome sequencing of C. arbuscula revealed a large number of potential secondary metabolite gene clusters (68, of which 9 contain terpene synthases), which are significantly more than the two predominant metabolites aurovertins B and D, suggesting that most gene clusters are silent or lowly expressed in axenic cultures. Epigenetic modifications have been proved to be a powerful way to activate silent gene clusters in fungi6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Deletion of hdaA, which encodes a histone deacetylase (HDAC), has led to the globally pleiotropic activation and overexpression of more than 75% of the biosynthetic genes and the isolation of diverse ten compounds of which four possess new structures, including three tricyclic diterpenes and a novel meroterpenoid derived from the esterification between an anthraquinone and a cassane diterpene5. So far, diterpenoids have exhibited diverse structural features and a wide range of interesting biological activities11, 12, such as cytotoxic13, 14, antimicrobial15, 16, anti-inflammatory17, and antiviral18, 19, 20 properties, attracting more and more attention.

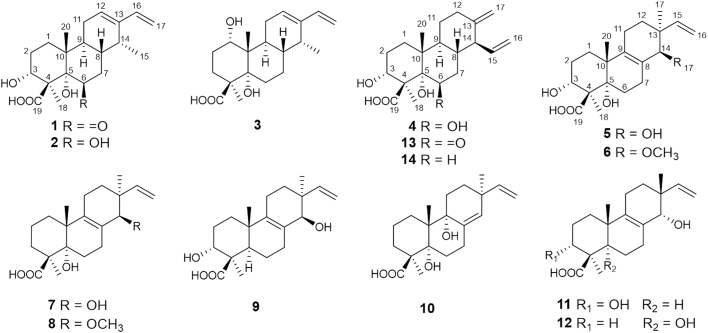

Careful analysis of the crude extract from the C. arbuscula ΔhdaA strain by UPLC—MS showed the presence of numerous minor ingredients that could not be identified due to sample limitations. To further explore the potential of the mutant strain ΔhdaA and ongoing search for diverse new bioactive natural products, we fermented in a larger scale using potato dextrose agar (PDA) culture. Subsequently, investigation of the PDA fermentation extract resulted in the isolation of twelve new diterpenoids including three cassanes (1--3), one cleistanthane (4), six pimaranes (5--10), and two isopimaranes (11 and 12), together with two known cleistanthanes analogues (13 and 14, Fig. 1). Herein, details of the isolation, structure characterization, and bioactivities of 1--14 are reported.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1—14.

2. Results and discussion

Compound 1 was isolated as a colorless amorphous solid with [α]20D +30.0 (c 0.10, MeOH). The IR spectrum of 1 showed absorption bands for hydroxyl (3490 cm—1), carbonyl (1724 cm—1), and carbon-carbon double bonds moieties (1649 cm—1). Its molecular formula was determined as C20H28O5 by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 347.1864 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H27O5, 347.1864) combined with NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1, Table 2). The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 showed signals attributable to a vinyl group [δH 6.25 (dd, J = 17.7 and 10.9 Hz, H-16), 5.09 (d, J = 17.7 Hz, H-17a), and 4.92 (d, J = 10.9 Hz, H-17b)], an olefinic proton [δH 5.66 (br s, H-12)], an oxygen-bearing methine [δH 4.34 (m, H-3)], a secondary methyl [δH 1.08 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-15)] and two tertiary methyl [δH 1.50 (s, H-18) and 0.89 (s, H-20)]. The 13C NMR and HSQC data revealed the presence of 20 carbons, including three methyls, four methylenes, four methines (including one O-methine), three sp3 quaternary carbons with one oxygenated, four olefinic carbons accounting for an olefin and a vinyl group, a carboxylic carbon (δC 175.1), and a ketone carbon (δC 211.7). These data accounted for all the NMR resonances of 1 and four of the seven unsaturation degrees, indicating 1 as a tricyclic compound.

Table 1.

13C NMR spectroscopic data (δ) for compounds 1−12a (δ in ppm).

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28.2 | 29.21 | 71.1 | 28.6 | 25.9 | 25.6 | 31.1 | 30.8 | 31.6 | 28.4 | 31.3 | 30.0 |

| 2 | 24.3 | 26.3 | 26.45 | 26.0 | 27.7 | 27.8 | 20.1 | 20.1 | 27.7 | 19.7 | 27.7 | 20.0 |

| 3 | 79.4 | 73.2 | 26.43 | 72.9 | 73.7 | 73.8 | 32.8 | 32.9 | 71.3 | 33.5 | 71.4 | 32.9 |

| 4 | 59.3 | 49.1 | 48.6 | 51.0 | 51.1 | 51.2 | 49.7 | 49.8 | 48.7 | 50.4 | 49.0 | 49.9 |

| 5 | 82.2 | 78.9 | 77.7 | 78.0 | 80.5 | 80.1 | 77.1 | 76.9 | 46.5 | 81.2 | 46.7 | 76.9 |

| 6 | 211.7 | 69.8 | 27.8 | 69.2 | 26.4 | 26.4 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 21.3 | 30.0 | 21.7 | 26.8 |

| 7 | 42.0 | 32.7 | 24.2 | 35.0 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 27.2 | 27.1 | 31.4 | 27.8 | 32.0 | 26.7 |

| 8 | 39.1 | 29.17 | 33.5 | 35.4 | 128.8 | 128.1 | 129.0 | 128.2 | 129.8 | 137.5 | 128.7 | 128.0 |

| 9 | 35.8 | 35.8 | 29.3 | 45.8 | 138.8 | 138.5 | 139.2 | 139.2 | 140.5 | 78.5 | 140.3 | 137.9 |

| 10 | 45.2 | 41.6 | 42.8 | 41.1 | 44.6 | 44.6 | 44.4 | 44.6 | 39.4 | 43.4 | 39.2 | 44.4 |

| 11 | 26.9 | 24.9 | 24.4 | 26.6 | 22.1 | 22.2 | 22.1 | 22.1 | 21.7 | 27.6 | 22.0 | 22.6 |

| 12 | 128.8 | 129.3 | 128.7 | 35.7 | 30.1 | 31.6 | 30.2 | 31.5 | 32.3 | 32.9 | 27.6 | 28.4 |

| 13 | 142.6 | 141.5 | 141.1 | 151.0 | 40.6 | 41.1 | 40.6 | 41.1 | 40.7 | 40.0 | 40.4 | 40.4 |

| 14 | 33.2 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 53.6 | 77.2 | 88.5 | 77.2 | 88.6 | 77.9 | 132.8 | 76.0 | 76.3 |

| 15 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 14.6 | 139.8 | 145.8 | 146.4 | 145.8 | 146.3 | 147.7 | 146.6 | 147.9 | 147.5 |

| 16 | 139.6 | 139.0 | 138.7 | 116.7 | 112.3 | 112.3 | 112.3 | 112.4 | 111.8 | 113.7 | 111.8 | 112.0 |

| 17 | 110.5 | 110.1 | 109.6 | 106.2 | 23.0 | 21.8 | 22.9 | 21.9 | 19.6 | 29.7 | 21.1 | 21.5 |

| 18 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 24.0 | 19.9 | 20.4 | 20.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.6 | 24.2 | 24.6 | 24.6 |

| 19 | 175.1 | 178.4 | 179.0 | 177.5 | 178.7 | 178.9 | 181.0 | 181.1 | 181.3 | 180.2 | 181.4 | 181.2 |

| 20 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 14.5 | 15.0 | 22.9 | 22.9 | 22.6 | 22.6 | 17.9 | 19.2 | 17.9 | 22.5 |

| OMe | 62.0 | 62.1 |

NMR data (δ) were measured at 125 MHz in CD3OD for 1, 5, 6, 8−12; at 150 MHz in CD3OD for 7; and at 150 MHz in DMSO-d6 for 2−4.

Table 2.

1H NMR spectroscopic data (δ) for compounds 1−4a (δ in ppm, J in Hz).

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.94, overlap | 1.70, td (13.8, 3.5) | 3.57, d (3.0) | 1.66, overlap |

| 1.59, m | 1.14, d (12.5) | 1.26, br d (12.8) | ||

| 2 | 2.31, m | 1.98, overlap | 2.10, overlap | 1.98, overlap |

| 2.03, overlap | 1.56, d (11.6) | 1.64, overlap | 1.57, m | |

| 3 | 4.34, br d (5.5) | 4.22, br s | 1.72, td (13.7, 4.0) | 5.21, br s |

| 1.50, overlap | ||||

| 6 | 4.04, br s | 2.03, td (13.8, 2.4) | 3.92, br s | |

| 1.62, overlap | ||||

| 7 | 3.14, t (12.9) | 2.11, m | 1.87, overlap | 1.62, overlap |

| 2.09, dd (13.0, 4.9) | 1.35, overlap | 1.24, br d (12.1) | ||

| 8 | 1.94, overlap | 1.77, m | 1.52, overlap | 1.41, m |

| 9 | 2.71, m | 2.09, m | 2.56, m | 1.72, overlap |

| 11 | 2.22, m | 2.01, overlap | 2.12, overlap | 1.70, overlap |

| 2.02, overlap | 1.95, overlap | 1.84, overlap | 1.00, qd (13.0, 3.6) | |

| 12 | 5.66, br s | 5.63, t (3.5) | 5.63, t (3.8) | 2.35, d (12.9) |

| 1.98, overlap | ||||

| 14 | 2.47, m | 2.32, m | 2.38, m | 2.25, t (9.8) |

| 15 | 1.08, d (7.0) | 0.87, d (6.8) | 0.92, d (6.9) | 5.62, ddd (17.2, 9.8, 9.8) |

| 16 | 6.25, dd (17.7, 10.9) | 6.20, dd (17.6, 10.9) | 6.20, dd (17.6, 10.9) | 5.13, dd (10.2, 2.0) |

| 4.98, dd (17.2, 2.0) | ||||

| 17 | 5.09,d (17.7) | 5.08,d (17.6) | 5.07,d (17.6) | 4.64, d (1.1) |

| 4.92, d (10.9) | 4.90, d (10.9) | 4.89, d (10.9) | 4.48, br s | |

| 18 | 1.50, s | 1.36, s | 1.12, s | 1.32, s |

| 20 | 0.89, s | 0.96, s | 0.70, s | 0.91, s |

| 1-OH | 5.50, d (4.0) | |||

| 3-OH | 6.23, br s | 6.23, d (2.5) | ||

| 5-OH | 6.10, br s | 5.15, s | 6.20, br s | |

| 6-OH | 7.21, br s | |||

| 19-OH | 12.11, s | 14.32, br s |

NMR data (δ) were measured at 500 MHz in CD3OD for 1 and at 600 MHz in DMSO-d6 for 2−4.

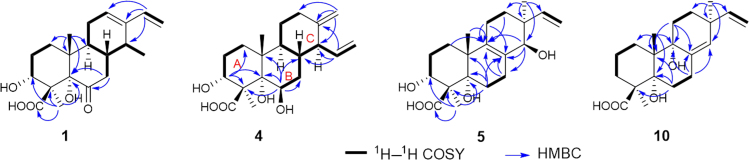

Analysis of the 1H–1H COSY NMR data (Fig. 2) of 1 identified the C-1–C-3 moiety, the C-16–C-17 vinyl group, and the C-7/8/9/11/12 unit with the C-14–C-15 fragment attached to C-8. In the HMBC spectrum (Fig. 2) of 1, correlations from the olefinic proton H-16 to C-12, C-13, and C-14 indicated that C-13 was connected to C-12, C-14, and C-16, respectively, establishing a cyclohexene ring with a vinyl and a methyl groups located at C-13 and C-14, respectively. HMBC correlations from the methyl H3-20 to C-1, C-5, C-9, and C-10 led to the connections of C-1, C-5, C-9, and C-20 to C-10. The HMBC correlations of H3-18/C-3, C-4, C-5, and C-19 and H2-7/C-5 and C-6 located two hydroxy groups at C-3 and C-5, respectively, a carboxyl group at C-19, and a ketone group at C-6, establishing the tricyclic cassane type diterpene skeleton. Based on these data, the planar structure of 1 was established as shown in Fig. 1 which is closely resemble to sonomolide B15 and hawaiinolide F14.

Figure 2.

1H—1H COSY and key HMBC correlations of compounds 1, 4, 5 and 10.

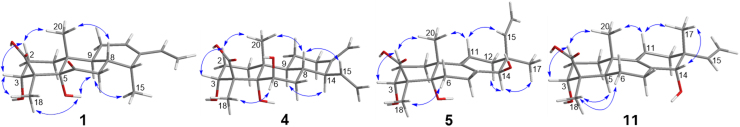

The relative configuration of 1 was deduced by analysis of NOESY spectrum. NOESY correlations (Fig. 3) of H3-20 with H-8 and H-2β (δH 2.03) and of H-3 with H-2β indicated that these protons were in the β-orientation, whereas those of H3-15 with H-9 suggested the α-axial orientation of the methyl at C-14. NOESY cross peaks of OH-5 with H-9 and H3-18, indicating the α-orientation for OH-5 and Me-18. Thus, the relative configuration of 1, which was very similar as those of hawaiinolides F and G14, was established.

Figure 3.

Key NOESY correlations of compounds 1, 4, 5 and 11.

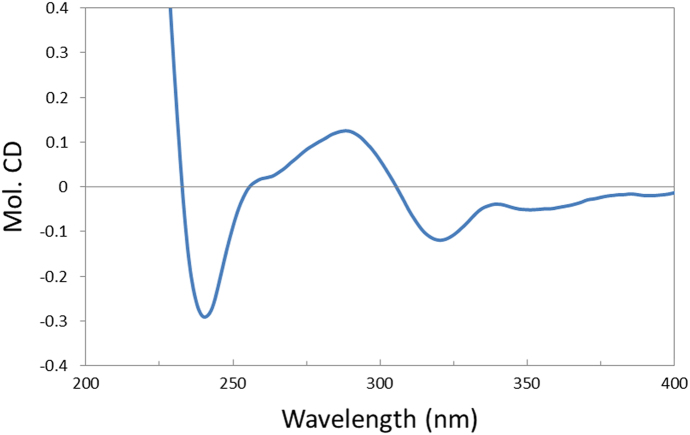

The absolute configuration of 1 was determined by analysis of its CD spectrum. The negative Cotton effect observed at 320 nm in the CD spectrum (Fig. 4) is associated with the n→π* transition of the cyclohexanone chromophore13, 21, 22. On the basis of the octant rule for cyclohexanones, the 5 S absolute configuration was determined. Combining the established relative configuration, the absolute configuration of 1 was deduced to be 3 R, 4 S, 5 S, 8 S, 9 S, 10 R, 14 R. Therefore, 1 was determined as 3R, 5S-dihydroxy-6-oxo-14R-cassane-12, 16-dien-19-oic acid and named calcarisporic acid A.

Figure 4.

CD spectrum of 1 in MeOH.

Compound 2 possesses the molecular formula C20H30O5 as determined by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 349.2030 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O5, 349.2020) and NMR spectroscopic data. Comparing the 1D NMR spectra (Table 1, Table 2) of 2 with those of 1, signals due to an oxygenated methine were observed at δH 4.04 (br s, H-6) and δC 69.8 in the NMR spectra of 2, with the disappearance of the ketone carbon at δC 211.7 (C-6) in 1. The HMBC correlations from the oxygenated methine proton at δH 4.04 (br s, H-6) to C-4, C-5, C-7, C-8, and C-10, indicated the location of the hydroxyl group at C-6. According to NOESY correlations, the relative configuration of 2 was same as that of 1, except for the presence of correlation of H-6 with H3-18, which suggested the β-configuration of OH-6. Therefore, 2 was established as 3α, 5α, 6β-trihydroxy-15α-cassane-12, 16-dien-19-oic acid and named calcarisporic acid B.

The molecular formula of compound 3 was determine as C20H30O4 on the basis of negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 333.2083 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071). The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1, Table 2) of 3 were similar to those of 2. The major difference was that signals for a methylene at δC 27.8 (C-6), δH 2.03 (td, J = 13.8, 2.4 Hz, H-6a), and δH 1.62 (m, H-6b) in 3 replaced resonances for an oxygenated methine at δC 69.8 (C-6) and δH 4.04 (br s, H-6) in 2, which were verified by HMBC correlations from H2-6 to C-5, C-7, C-8, and C-10. HMBC correlations from H-1 (δH 3.57) to C-3, C-5, C-10, and C-20, suggested that C-1 was substituted by a hydroxy group. In addition, the relative configuration of 3 was deduced from NOESY correlations and by comparison to that of 2. NOESY correlations of H3-20 with H-1 and H-8 indicated the β-configuration of H-1, whereas those of OH-5 with H3-18, OH-1, and H-9, and of H3-15 with H-9 revealed that they were in the α-orientation. Thus, 3 was elucidated as 1α, 5α-dihydroxy-15α-cassane-12, 16-dien-19-oic acid and designated as calcarisporic acid C.

Compound 4, colorless needles with [α]20D +10.2 (c 0.17, MeOH), was determined to have the molecular formula of C20H30O5 by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 349.2031 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O5, 349.2020). The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1, Table 2) showed the presence of two tertiary methyl, five methylenes, five methines (including two O-methines), three sp3 quaternary carbons with one oxygenated, four olefinic carbons accounting for an exocyclic olefin [δH 4.64 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, H-17a), and 4.48 (br s, H-17b); δC 106.2 (C-17) and 151.0 (C-13)] and a vinyl group [δH 5.62 (ddd, J = 17.2, 9.8 and 9.8 Hz, H-15), 5.13 (dd, J = 10.2 and 2.0 Hz, H-16a), and 4.98 (dd, J = 17.2 and 2.0 Hz, H-16b); δC 139.8 (C-15) and 116.7 (C-16)], and one carboxylic carbon [δC 177.5 (C-19)]. Comparison of the NMR spectroscopic data of 4 with those of 2 suggested that 4 possessed the same A and B ring units as those in 2. Analysis of the 1H—1H COSY NMR data (Fig. 2) of 4 revealed the C-6/7/8/9/11/12 unit with the C-14–C-16 fragment attached to C-8. HMBC correlations (Fig. 2) of H2-17/C-12, C-13, and C-14, and H-15/C-13, C-14, and C-8 confirmed that the olefinic methylene and vinyl group connected to C-13 and C-14, respectively, establishing a cyclohexane of C ring moiety with an exocyclic olefin at C-13/C-17 and a vinyl group attached to C-13 fused to the B ring unit at C-8/C9. Thus, the planar structure of 4 was established (Fig. 1), a tricyclic cleistanthane diterpene, which closely resembled that of zythiostromic acid A isolated from Zythiostroma sp. with [α]20D −31.7 (c 0.35, MeOH)23. This suggested that the two compounds are diastereomers. Comparison of the chemical shifts and coupling constants in the 1H NMR spectra of 4 and zythiostromic acid A indicated difference only in the signals attribute to H-14 and H-15. This suggested that 4 was the C-14 epimer of zythiostromic acid A, which were confirmed by NOESY correlations (Fig. 3) of H-14 with H-9, and of H-8 with H-15 and H3-20, while other NOESY correlations of 4 were the same as those of zythiostromic acid A. Therefore, 4 was established as 3α, 5α, 6β-trihydroxy-15β-cleistanthane-13(17), 15-dien-19-oic acid and named calcarisporic acid D.

Compound 5 was obtained as colorless needles. Its molecular formula was C20H30O5, as determined by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 349.2036 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O5, 349.2020). Analysis of its 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1, Table 3) revealed the presence of three tertiary methyls, six methylenes, two oxygenated methines, four sp3 quaternary carbons with one oxygenated, four olefinic carbons accounting for a tetra-substituted olefin and a vinyl group, and a carboxylic carbon (δC 178.7). Comparison of the NMR spectroscopic data of 5 with those of 2 suggested that 5 possessed the same A ring moiety as 2. Interpretation of the 1H—1H COSY NMR data (Fig. 2) of 5 identified the C-6–C-7 moiety, the C-11–C-12 unit, and the C-15–C-16 vinyl group. HMBC correlations (Fig. 2) from H-6 to C-4, C-5, and C-10 suggested that the C-6–C-7 moiety was attached to C-5. HMBC correlations from H-1, H3-20, and H-7 to C-9, and from H-6 and H-7 to C-8 suggested that the tetra-substituted olefin C-8 and C-9 were connected to C-7 and C-9, respectively, establishing a cyclohexene of B ring moiety fused to the A ring unit at C-5/C10. HMBC correlations from H-14 to C-7, C-8, and C-9, and from H-11 to C-8, C-9, and C-10 indicated that the oxygenated C-14 and C-11 were attached to C-8 and C-9, respectively. HMBC cross peaks from H3-17 to C-12, C-13, C-14, and C-15 led to the connections of C-12, C-14, C-15, and C-17 to C-13, establishing the C-8/C-9 fused cyclohexene of C ring unit with a methyl and a vinyl group both attached to C-13. Thus, the planar structure of 5 was established as shown in Fig. 1, a tricyclic pimarane diterpene. The relative configuration of 5 was confirmed by NOESY spectrum. NOESY correlations (Fig. 3) of H-11β (δH 1.96) with H3-20 and H-15, and of H-2β (δH 2.31) with H-3 and H3-20 suggested that these protons were in the β-configuration, whereas those of H-14 with H3-17 and H-12α (δH 1.44) indicated the α-axial configuration of H-14. NOESY correlation of Me-18 with H-3 and H-6α (δH 1.92) and the absence of NOESY correlation between Me-18 and the axial Me-20 revealed that the carboxylic group at C-4 was in the β-axial orientation. Thus, 5 was elucidated as 3α, 5α, 14β-trihydroxy-pimarane-8(9), 15-dien-19-oic acid and designated as calcarisporic acid E.

Table 3.

1H NMR spectroscopic data (δ) for compounds 5−8a (δ in ppm, J in Hz).

| No. | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.97, overlap | 1.96, overlap | 1.78, dd (12.9, 4.1) | 1.77, overlap |

| 1.41, br d (12.5) | 1.38, overlap | 1.42, overlap | 1.41, overlap | |

| 2 | 2.31, m | 2.30, m | 1.97, overlap | 1.96, overlap |

| 1.73, dd (14.4, 3.0) | 1.71, m | 1.46, overlap | 1.45, overlap | |

| 3 | 4.10, br s | 4.07, br s | 1.83, d (12.7) | 1.83, d (12.8) |

| 1.74, overlap | 1.72, overlap | |||

| 6 | 2.48, m | 2.47, m | 2.49, m | 2.50, m |

| 1.92, overlap | 1.94, overlap | 1.93, overlap | 1.94, overlap | |

| 7 | 2.55, m | 2.51, m | 2.57, m | 2.51, m |

| 1.93, overlap | 1.93, overlap | 1.95, overlap | 1.96, overlap | |

| 11 | 2.02, overlap | 1.99, overlap | 1.94, overlap | 1.92, overlap |

| 1.96, overlap | 1.94, overlap | |||

| 12 | 1.67, m | 1.59, m | 1.66, m | 1.58, m |

| 1.44, overlap | 1.47, overlap | 1.43, overlap | 1.46, overlap | |

| 14 | 3.47, br s | 3.24, br s | 3.48, br s | 3.24, br s |

| 15 | 5.76, dd (17.7, 11.0) | 5.80, dd (17.7, 11.0) | 5.77, dd (17.7, 11.0) | 5.80, dd (17.7, 11.0) |

| 16 | 4.96, br d (17.7) | 4.99, dd (17.7, 1.4) | 4.96, dd (17.7, 1.4) | 4.99, dd (17.7, 1.0) |

| 4.93, br d (11.0) | 4.95, dd (11.0, 1.4) | 4.94, dd (10.9, 1.4) | 4.95, dd (11.0, 1.0) | |

| 17 | 1.01, s | 1.05, s | 1.01, s | 1.05, s |

| 18 | 1.46, s | 1.45, s | 1.23, s | 1.24, s |

| 20 | 1.01, s | 1.01, s | 1.00, s | 1.00, s |

| OMe | 3.51, s | 3.52, s |

NMR data (δ) were measured at 500 MHz in CD3OD for 5, 6, and 8, and at 600 MHz in CD3OD for 7.

The molecular formula of compound 6 was established as C21H32O5 by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 363.2182 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C21H31O5, 363.2177). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra (Table 1, Table 3) of 6 showed close resemblance to those of 5, except for the presence of an additional methoxy group [δH 3.51 (3 H, s), δC 62.0] relative to 5. It was observed that the resonance for C-14 was downfield-shifted from δC 77.2 in 5 to δC 88.5 in 6, and the protons of methoxy group showed HMBC correlation with C-14, which suggested that 6 was the 14-methoxy derivative of 5. The relative configuration of 6 was the same as that of 5 according to NOESY correlations. Therefore, 6 was elucidated as 3α,5α-dihydroxy-14β-methoxy-pimarane-8(9), 15-dien-19-oic acid and designated as calcarisporic acid F.

Compound 7 was assigned the molecular formula C20H30O4 by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 333.2077 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071), one less oxygen than that of 5. Comparison of the NMR data of 7 with those of 5 indicated that an O-methine [δH 4.10, δC 73.7] at C-3 in 5 was replayed by a methylene [δH 1.83 and 1.74, δC 32.8] in 7. This suggested that 7 was the 3-dehydroxy analog of 5, which was confirmed by HMBC correlations from H2-3 to C-1, C-2, C-4, and C-5. NOESY correlations of H-11β (δH 1.94) with H3-20 and H-15, of H-14 with H3-17 and H-12α (δH 1.43), and of H3-18 with H-3α (δH 1.83), H-3β (δH 1.74), and H-6α (δH 1.93) indicated that the relative configuration of 7 was similar as that of 5. Thus, 7 was established as 5α,14β-dihydroxy-pimarane-8(9), 15-dien-19-oic acid and named calcarisporic acid G.

Compound 8 was determined to have the molecular formula of C21H32O4 by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 347.2239 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C21H31O4, 347.2228). The NMR data (Table 1, Table 3) of 8 were closely similar to those of 7. The major differences were that an additional methoxy group was presented in 8, and the resonance for C-14 was downfield-shifted by 11.4 ppm in comparison with 7. This indicated that 8 was the 14-methoxy derivative of 7, which was verified by HMBC correlations from H-14 to the additional methoxy group (δC 62.1), C-8, C-9, C-13, and C-15. The relative configuration of 8 was identical with that of 7 according to NOESY spectrum. Consequently, 8 was elucidated as 5α-hydroxy-14β-methoxy-pimarane-8(9), 15-dien-19-oic acid and designated as calcarisporic acid H.

The molecular formula of compound 9 was deduced to be C20H30O4 by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 333.2077 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra (Table 1, Table 4) of 9 showed close resemblance to those of 5, with the exception of the signals assigned to C-5, where the oxygenated quaternary carbon (δC 80.5) in 5 was replayed by a methine [δH 1.79 (d, J = 12.2 Hz), and δC 46.5] in 9. This suggested that 9 was the 5-dehydroxy analog of 5, which was confirmed by HMBC correlations from H-5 (δH 1.79) to C-1, C-4, C-6, C-10, C-18, C-19, and C-20. NOESY correlations of H3-18 with H-5 (δH 1.79) and H-3, of H-11β (δH 1.92) with H3-20 and H-15, and of H-14 with H3-17 and H-12α (δH 1.43) indicated that the relative configuration of 9 was in accordance with that of 5. Therefore, 9 was elucidated as 3α,14β-dihydroxy-pimarane-8(9), 15-dien-19-oic acid and designated as calcarisporic acid I.

Table 4.

1H NMR spectroscopic data (δ) for compounds 9−12a (δ in ppm, J in Hz).

| No. | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.56, overlap | 1.61, dd (13.6, 3.7) | 1.54, overlap | 1.76, overlap |

| 1.52, overlap | 1.31, br d (13.6) | 1.45, overlap | ||

| 2 | 2.17, m | 1.99, dd (13.5, 3.8) | 2.19, m | 1.98, overlap |

| 1.63, m | 1.48, overlap | 1.63, dd (14.4, 3.0) | 1.45, overlap | |

| 3 | 4.00, t (2.50) | 1.88, d (14.0) | 4.01, br s | 1.85, d (13.2) |

| 1.52, overlap | 1.69, m | |||

| 5 | 1.79, d (12.2) | 1.79, dd (9.3, 3.9) | ||

| 6 | 1.90, overlap | 2.54, td (13.9, 6.0) | 2.02, overlap | 2.45, overlap |

| 1.84, td (12.1, 5.3) | 1.92, dd (14.7, 5.2) | 1.90, overlap | 1.95, overlap | |

| 7 | 2.34, m | 2.32, tdd (13.5, 5.8, 2.2) | 2.47, br d (13.5) | 2.43, overlap |

| 1.95, dd (18.0, 4.5) | 2.22, dd (15.5, 4.9) | 1.86, overlap | 2.08, overlap | |

| 11 | 2.07, m | 1.71, m | 2.03, overlap | 2.02, overlap |

| 1.92, overlap | 1.50, overlap | 1.91, overlap | 1.93, overlap | |

| 12 | 1.57, overlap | 1.59, overlap | 1.73, m | 1.74, m |

| 1.43, m | 1.49, overlap | 1.36, br d (12.3) | 1.38, dd (12.9, 5.0) | |

| 14 | 3.63, br s | 5.37, br s | 3.22, br s | 3.30, br s |

| 15 | 5.86, dd (17.7, 10.9) | 5.70, dd (17.4, 10.5) | 6.00, dd (18.0, 10.5) | 6.01, dd (17.4, 10.4) |

| 16 | 4.98, dd (17.7, 1.1) | 4.96, dd (10.5, 1.7) | 5.00, dd (18.0, 1.0) | 5.01, dd (17.4, 1.5) |

| 4.94, dd (10.9, 1.1) | 4.91, dd (17.4, 1.7) | 4.99, dd (10.5, 1.0) | 5.00, dd (10.4, 1.5) | |

| 17 | 0.98, s | 1.03, s | 0.89, s | 0.92, s |

| 18 | 1.27, s | 1.28, s | 1.28, s | 1.23, s |

| 20 | 0.92, s | 0.95, s | 0.96, s | 1.06, s |

NMR data (δ) were measured at 500 MHz in CD3OD for 9−12.

Compound 10 was assigned the molecular formula C20H30O4 by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 333.2069 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071). The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1, Table 4) showed the presence of three tertiary methyls, seven methylenes, five sp3 quaternary carbons with two oxygenated, four olefinic carbons accounting for a trisubstituted olefin and a vinyl group, and a carboxylic carbon (δC 180.2). Comparison of the NMR spectroscopic data of 10 with those of 7 suggested that 10 possessed the same A ring unit as 7. Analysis of the 1H—1H COSY spectrum (Fig. 2) of 10 revealed the C-6–C-7 moiety, the C-11–C-12 unit, and the C-16–C-17 vinyl group. HMBC correlations (Fig. 2) from H3-20 to C-1, C-5, C-10, and an oxygenated quaternary carbon at C-9 (δC 78.5) indicated that C-9 was connected to C-10. HMBC cross peaks from H2-6 to C-4, C-5, and C-10, and from H2-7 to C-8 (δC 137.5), C-14 (δC 132.8), and C-9 suggested that C-6 was attached to C-5, and the olefinic C-8 was connected to both C-7 and C-9, establishing a cyclohexane of B ring moiety with an exocyclic olefin at C-8/C-14 fused to the A ring unit at C-5/C10. Further HMBC correlations from H2-11 to C-8, C-9, and C-10 indicated that C-11 was connected to C-9. HMBC correlations from H3-17 to C-12, C-13, C-14, and C-15 (δC 146.6) led to the connections of C-12, C-14, C-15, and C-17 to C-13, establishing the C-8/C-9 fused cyclohexene of C ring unit with a methyl and a vinyl group both attached to C-13. The relative configuration of 10 was similar as that of 7 according to NOESY correlations of H-11β (δH 1.71) with H3-20 and H-15 and of H3-18 with H-3α (δH 1.88), H-3β (δH 1.52), and H-6α (δH 1.92). Thus, 10 was established as 5α, 9α-dihydroxy-pimarane-8(14), 15-dien-19-oic acid and named calcarisporic acid J.

Compound 11 possessed the same molecular formula as 9, C20H30O4, deduced from negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 333.2077 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071). The NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1, Table 4) of 11 closely resembled those of 9 except for minor differences in signals due to C-12, C-14, and C-17, suggesting that 11 was the C-13 and C-14 diastereomer of 9. This speculation was supported by NOESY experiment. NOESY cross peaks (Fig. 3) of H-11β (δH 2.03) with H3-20 and H3-17 implied that the methyl at C-13 had a β-configuration. Correlations of H-14 (δH 3.22) with H3-17 indicated that H-14 was in the β-equatorial configuration. Therefore, 11 was established as 3α,14α-dihydroxy-isopimarane-8(9), 15-dien-19-oic acid and designated as calcarisporic acid K.

Compound 12 possessed the same molecular formula of C20H30O4 as 7, which were determined by negative HR-ESI-MS at m/z 333.2084 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071). A detailed comparison of the NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1, Table 4) of 12 with those of 7 revealed that they possessed the identical planar structure, while weak differences were attributed to C-12, C-14, C-15, and C-17, suggesting that the two compounds were diastereomers. This was further verified by NOESY correlations of H-11β (δH 2.02) with H3-20 and H3-17, and of H-14 (δH 3.30) with H3-17. Thus, 12 was elucidated as 5α,14α-dihydroxy-isopimarane-8(9), 15-dien-19-oic acid and designated as calcarisporic acid L.

The known compounds were identified as hawaiinolide G14 (13) and 14-epi-zythiostromic acid B16 (14), respectively, by comparing their NMR spectroscopic data with those reported in literatures.

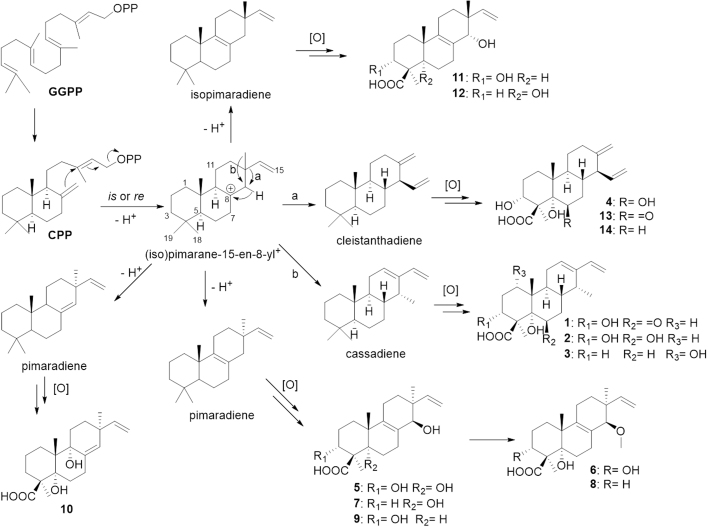

It was worth mentioning that the pimarane and isopimarane type diterpenes (5−12) were isolated from the genus Calcarisporium for the first time. This discovery further supported the proposed pathway for the biosynthesis of these diterpenes (Scheme 1), where they could be synthesized from the same diterpene biosynthetic gene cluster, and the cassane and cleistanthane type diterpenoids both derived from the (iso)pimaranes, in which migration of either the C-13 methyl or vinyl group to C-14 led to the cassane or cleistanthane type diterpenoids5, 24, 25. Subsequently, three types of diterpenoids skeleton were heavily oxidized to form the characteristic diterpenoids above, encouraging us to search more diverse structures in this mutant strain.

Scheme 1.

Proposed biosynthetic pathways for compounds 1−14.

Cytotoxic activities of compounds 1—14 were evaluated against two human cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and HepG-2) in the MTT assay, with taxol as a positive control (IC50 5.0±0.6, 3.5±0.4 nmol/L, respectively). None of them exhibited significant activities in the concentration range of 10—5–10—7 mol/L.

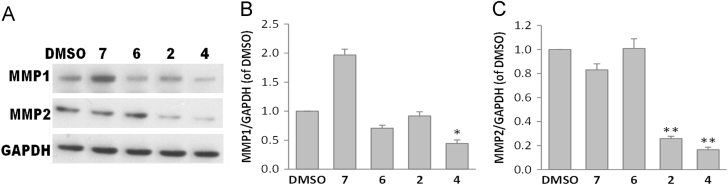

The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) family can degrade various protein components in the extracellular matrix and plays a key role in tumor invasion and metastasis26, 27. Therefore, we tested the inhibitory effects of the isolated compounds on the expression of MMP1 and MMP2 in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells by Western blot assay. Due to the sample limitation, compounds 2, 4, 6, and 7 were evaluated for this inhibitory activity firstly. Experimental results (Fig. 5) indicated that the four tested compounds had no significant inhibitory effects on the viability of MCF-7 cells, but the expression level of MMP1 and MMP2 could be affected obviously. Western blot showed that both 2 and 4 could reduce MMP2 expression significantly at 200 μmol/L for 24 h with significant difference from that in DMSO control group. Meanwhile, 4 could also reduce MMP1 expression significantly. This indicated that the activities of 2 and 4 may be associated with expression inhibition of MMP proteinases family, and although 2 and 4 exhibited no cytotoxicities against tested tumor cell lines, they could function in suppressing tumor invasion and metastasis and possesses potential antitumor value. Comparing the structure of 4 with that of 2, the major difference was that a vinyl group at C-14 in 4 and a methyl group at C-14 in 2 were observed. Both 4 and 2 possessed an unsaturated unit connected to C-13. These suggested that the vinyl group attached to C-14 contributed as a functional group and the substituted group at C-14 may play an important role in the inhibitory effect on the expression level of MMP1 and MMP2.

Figure 5.

Effects of compounds 2, 4, 6, and 7 on the expressions of MMP1 and MMP2 in MCF-7 cells. (A) Cells were treated with different test compounds at 200 μmol/L or DMSO as control for 24 h. The expressions of MMP1 and MMP2 were determined by Western blot. Representative immunoblots are shown and GAPDH is the loading control. (B) Relative expression level of MMP1 is calibrated by GAPDH. (C) Relative expression level of MMP2 is calibrated by GAPDH. Each value represents the mean±SD of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus DMSO control.

In addition, compounds 1—14 were assessed for their anti-inflammatory inhibitory activities against the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced NO production in murine microglial BV2 cells as well as their antioxidant activities against rat liver microsomal lipid peroxidation induced by Fe2+-cystine in vitro. All compounds were inactive for anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities at the concentrations of 10—5 and 10—4 mol/L, respectively.

3. Conclusions

Twelve new diterpenoids, calcarisporic acids A--L, including three cassanes (1−3), one cleistanthane (4), six pimaranes (5--10), and two isopimaranes (11 and 12) along with two know cleistanthanes analogues (13 and 14), were isolated from the mutant strain ΔhdaA of Calcarisporium arbuscula, in which an encoding histone deacetylase gene (and hdaA) was deleted. Compounds 5--12 are the first examples of pimarane and isopimarane type diterpenes isolated from the genus Calcarisporium. In addition, the inhibitory effects of four compounds (2, 4, 6 and 7) on the expression of MMP1 and MMP2 in MCF-7 cells were evaluated. Compounds 2 and 4 significantly inhibited the expression level of MMP1 and MMP2, and are promising as a potential anti-metastatic agent for the treatment of human breast cancer. Our results further present the potential of genome mining-guided discovery of bioactive natural products in fungi.

4. Experimental

4.1. General experimental procedures

Optical rotations were measured on an Autopol IV automatic polarimeter (Rudolph Research Co.). UV spectra were measured on a JASCO V650 spectrophotometer. CD spectra were measured on a JASCO J-815 spectrometer. IR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet 5700 FT-IR spectrometer using a FT-IR microscope transmission method. NMR spectra were recorded at 600 or 500 MHz for 1H NMR and 150 or 125 MHz for 13C NMR, respectively, on a Bruker AVIIIHD 600 (Bruker Corp., Karlsruhe, Germany) or a VNS-600 or an Inova 500 instrument (Varian Associates Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) in CD3OD or DMSO-d6 with solvent peaks used as references at 25 °C. ESI-MS and analytical HPLC were performed on a Waters ACQUITY H-Class UPLC—MS with QDA mass detector (ACQUITY UPLC® BEH, 1.7 μm, 50 mm × 2.1 mm, C18 column) using positive and negative mode electrospray ionization. HR-ESI-MS data were taken on an Agilent 6520 Accurate-Mass Q-TOF LC/MS spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Ltd., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Semi-preparative HPLC was performed on a LabAlliance Series III pump equipped with a LabAlliance model 201 UV detector, using YMC-Pack ODS-A column (250 mm × 10 mm, 5μm). Column chromatography (CC) was carried out on silica gel (200–300 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Inc., Qingdao, China), Sephadex LH-20 (Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden), or reversed phase C18 silica gel (50 µm, YMC, Kyoto, Japan). TLC was carried out on glass precoated silica gel GF254 plates (Qingdao Marine Chemical Co., Ltd., China). Spots were visualized under UV light or by spraying with 10% H2SO4 in 95% EtOH followed by heating.

4.2. Fungal material

Fungus Calcarisporium arbuscula NRRL 3705 (ATCC® 46034TM) is the wild type strain. The ΔhdaA mutants were constructed by replacement of hdaA by hph (Hygromycin resistance gene)5. The mutant strains were grown on 20 L of solid PDA media (BD) divided into 200 large 150 × 15 mm2 Petri dishes at room temperature for 40 days.

4.3. Extraction and isolation

The fermented material was extracted repeatedly with EtOAc (3 × 5.0 L), and the organic solvent was evaporated to dryness under vacuum to afford the crude extract (14.2 g), which was partitioned between MeOH and hexane. The MeOH fraction (13.5 g) was evaporated to dryness under vacuum, and separated by reversed phase C18 silica gel vacuum liquid chromatography with a gradient of MeOH (20%–100%) in H2O to give eleven fractions (F1−F11).

Fractions F3−F5 were combined (4.1 g) and subjected to reversed phase C18 silica gel vacuum liquid chromatography with a gradient of MeOH (5–80%) in H2O to afford twenty fractions (F3-1−F3-20). Fraction F3-15 (307 mg) was separated by reverse-phase HPLC (YMC-ODS-A, 5 µm, 250 mm × 20 mm), eluted by 42% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.02% formic acid) at a flow rate of 5.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to give six fractions (F3-15-1−F3-15-6). Fraction F3-15-2 (30.2 mg) was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 72% MeOH−H2O (v/v, 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to yield 5 (16.1 mg, tR = 22 min). Fraction F3-15-3 (18.2 mg) was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 75% MeOH−H2O (v/v, 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to yield 11 (1.9 mg, tR = 14 min) and 9 (8.9 mg, tR = 19 min). Fraction F3-18 (472 mg) was subjected to CC over Sephadex LH-20 eluted by MeOH to afford nine fractions (F3-18-1−F3-18-9). Fraction F3-18-5 (90 mg) was purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 63% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.02% formic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to yield 7 (21.8 mg, tR = 17 min), 6 (12.6 mg, tR = 19 min), 8 (8.3 mg, tR = 34 min), and 13 (2.3 mg, tR = 42 min). Fraction F3-18-7 (65 mg) was purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 57% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.02% formic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to yield 1 (1.5 mg, tR = 36 min).

Fraction F6 (1.6 g) was subjected to CC over Sephadex LH-20 eluted by MeOH to afford seven fractions (F6-1−F6-7). Fraction F6-6 (1.1 g) was recrystallized with MeOH to give a white solid, which was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 50% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to give 4 (49.8 mg, tR = 34 min). Fraction F6-7 (88 mg) was purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 50% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to give 2 (13.7 mg, tR = 32 min) and subfraction F6-73 (13.4 mg), which was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 80% MeOH−H2O (v/v, 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to give 3 (3.8 mg, tR = 29 min).

Fraction F8 (1.1 g) was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC (YMC-ODS-A, 5 µm, 250 × 20 mm), eluted by 47% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.02% formic acid) at a flow rate of 5.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to give six fractions (F8-1−F8-6). Fraction F8-4 (7.0 mg) was purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 47% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.02% formic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to give 10 (3.6 mg, tR = 53 min). Fraction F8-5 (270 mg) was further purified by Sephadex LH-20 eluted by MeOH to give 14 (8.0 mg). Fraction F8-6 (89 mg) was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC, eluted by 50% MeCN−H2O (v/v, 0.02% formic acid) at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min detected at 210 nm, to give 12 (5.2 mg, tR = 24 min).

4.3.1. Calcarisporic acid A (1)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D +30.0 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 229 (4.68) nm; CD (c 1.4 × 10—3 mol/L, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 240 (−0.29), 288 (+0.13), 320 (−0.12) nm; IR νmax 3490, 3086, 2930, 1809, 1724, 1649, 1603, 1457, 1391, 1223, 1099, 994, 897, 852, 760 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 2, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 347 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 347.1864 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H27O5, 347.1864).

4.3.2. Calcarisporic acid B (2)

Colorless granules (MeOH); [α]20D +51.7 (c 0.19, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 231 (4.96) nm; IR νmax 3307, 3198, 2938, 2612, 1694, 1652, 1602, 1516, 1468, 1436, 1276, 1081, 1004, 955, 893, 769, 732, 592 cm—1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) data see Table 2, 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 349 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 349.2030 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O5, 349.2020).

4.3.3. Calcarisporic acid C (3)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D +83.3 (c 0.19, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 231 (4.81) nm; IR νmax 3309, 3183, 2974, 2930, 1688, 1652, 1606, 1462, 1271, 1117, 962, 949, 929, 893, 798, 711, 647, 535 cm—1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) data see Table 2, 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 333 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 333.2083 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071).

4.3.4. Calcarisporic acid D (4)

Colorless needles (MeOH); [α]20D +10.2 (c 0.17, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 204 (4.50) nm; IR νmax 3456, 3367, 3073, 2965, 2320, 1694, 1645, 1509, 1465, 1421, 1297, 1166, 1003, 965, 918, 771, 725, 608, 568 cm—1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) data see Table 2, 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 349 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 349.2031 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O5, 349.2020).

4.3.5. Calcarisporic acid E (5)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D −12.0 (c 0.20, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 206 (4.37) nm; IR νmax 3339, 3080, 2935, 1701, 1638, 1460, 1380, 1267, 1009, 948, 912, 855, 706, 672 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 3, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 349 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 349.2036 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O5, 349.2020).

4.3.6. Calcarisporic acid F (6)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D −21.0 (c 0.13, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 204 (4.58) nm; IR νmax 3495, 3274, 3079, 2934, 1701, 1635, 1461, 1383, 1238, 1089, 1005, 939, 907, 864, 690, 665 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 3, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 363 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 363.2182 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C21H31O5, 363.2177).

4.3.7. Calcarisporic acid G (7)

Colorless needles (MeOH); [α]20D +16.0 (c 0.20, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 204 (4.47) nm; IR νmax 3544, 3353, 2934, 1686, 1621, 1467, 1433, 1377, 1280, 1255, 1065, 941, 914, 800, 675 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) data see Table 3, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 333 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 333.2077 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071).

4.3.8. Calcarisporic acid H (8)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D +12.0 (c 0.15, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 205 (4.51) nm; IR νmax 3570, 3147, 2937, 1724, 1638, 1606, 1458, 1383, 1274, 1200, 1073, 973, 937, 854, 796, 675 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 3, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 347 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 347.2239 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C21H31O4, 347.2228).

4.3.9. Calcarisporic acid I (9)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D +56.9 (c 0.19, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 206 (4.50) nm; IR νmax 3427, 3082, 2933, 1694, 1456, 1379, 1250, 1197, 1046, 966, 915, 858, 698 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 4, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 333 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 333.2077 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071).

4.3.10. Calcarisporic acid J (10)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D +103.9 (c 0.22, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 205 (4.41) nm; IR νmax 3382, 2950, 2875, 1700, 1637, 1553, 1453, 1377, 1254, 1143, 1090, 999, 917, 882, 802, 656 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 4, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 333 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 333.2069 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071).

4.3.11. Calcarisporic acid K (11)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D +85.9 (c 0.16, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 204 (4.52) nm; IR νmax 3430, 3082, 2928, 2871, 1693, 1455, 1413, 1378, 1357, 1199, 1146, 1005, 980, 913, 802, 698, 621 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 4, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 333 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 333.2077 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071).

4.3.12. Calcarisporic acid L (12)

Colorless amorphous solid; [α]20D +126.9 (c 0.12, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 204 (4.59) nm; IR νmax 3498, 2930, 2865, 1707, 1639, 1458, 1391, 1308, 1278, 1002, 981, 917, 798, 685 cm—1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) data see Table 4, 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) data see Table 1; ESI-MS m/z 333 [M–H]−; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 333.2084 [M–H]− (Calcd. for C20H29O4, 333.2071).

4.4. Cytotoxicity assay

Compounds 1–14 were tested for cytotoxic activities against MCF-7 (human breast cancer) and HepG-2 (human liver cancer) cell lines by the MTT method, as described in the literature28.

4.5. Inhibitory effects on the expression of MMP1 and MMP2 in MCF-7 cells

Compounds 2, 4, 6, and 7 were tested for the inhibitory effects on the expression of MMP1 and MMP2 in human breast carcinoma cell line MCF-7 by Western blot. MCF-7 cells was purchased from Cell Bank of Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Science, and was cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL benzyl penicillin G, and 100 mg/L streptomycin under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. MCF-7 cells were treated with different test compounds at 200 μmol/L or DMSO as control for 24 h. Then, cells were collected and lysed. The lysates were clarified by 12,000 × g centrifugation at 4 °C for 30 min. Total proteins were quantified with a microplate spectrophotometer using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA assay). Then equal amount of proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The blots were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by second antibodies at the room temperature for 0.5 h. Immunoreactive protein bands were detected by the ECL detection system (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

4.6. Anti-inflammatory activity assay

Compounds 1–14 were assessed for their anti-inflammatory inhibitory activities against the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced NO production in murine microglial BV2 cell line using the Griess method, as described in the literature29. Curcumin was used as the positive control (inhibitory rate 66.0±2.5% at 10—5 mol/L).

4.7. Antioxidant assay

Compounds 1–14 were assessed for their antioxidant activities against rat liver microsomal lipid peroxidation induced by Fe2+--cystine in vitro, as described in the literature30. Curcumin was used as the positive control (inhibitory rate 95.0±3.5% at 10—4 mol/L).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21502233 and 81522043), CAMS Initiative for Innovative Medicine (CAMS-I2M-1-010), the PUMC Youth Fund (33320140175), and the State Key Laboratory Fund for Excellent Young Scientists to Youcai Hu (GTZB201401). We are grateful to the Department of Instrumental Analysis, Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College for the spectroscopic measurements and Prof. Xiaoguang Chen and Prof. Dan Zhang for the cytotoxicity, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant assays.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Watson P. Calcarisporium arbuscula living as an endophyte in apparently healthy sporophores of Russula and Lactarius. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1955;38:409–414. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osselton M.D., Baum H., Beechey R.B. Isolation, purification and characterization of aurovertin B. Biochem Soc Trans. 1974;2:200–202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Raaij M.J., Abrahams J.P., Leslie A.G., Walker J.E. The structure of bovine F1-ATPase complexed with the antibiotic inhibitor aurovertin B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6913–6917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulheirn L.J., Beechey R.B., Leworthy D.P., Osselton M.D. Aurovertin B, a metabolite of Calcarisporium arbuscula. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1974;21:874–876. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao X.M., Xu W., Li D., Yin W.B., Chooi Y.H., Li Y.Q. Epigenetic genome mining of an endophytic fungus leads to the pleiotropic biosynthesis of natural products. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:7592–7596. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cichewicz R.H. Epigenome manipulation as a pathway to new natural product scaffolds and their congeners. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:11–22. doi: 10.1039/b920860g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albright J.C., Henke M.T., Soukup A.A., McClure R.A., Thomson R.J., Keller N.P. Large-scale metabolomics reveals a complex response of Aspergillus nidulans to epigenetic perturbation. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:1535–1541. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu G., Zhou H., Zhang P., Wang X., Li W., Zhang W. Polyketide production of pestaloficiols and macrodiolide ficiolides revealed by manipulations of epigenetic regulators in an endophytic fungus. Org Lett. 2016;18:1832–1835. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan A., Mi W., Liu Z., Zeng G., Zhang P., Hu Y. Deletion of a histone acetyltransferase leads to the pleiotropic activation of natural products in Metarhizium robertsii. Org Lett. 2017;19:1686–1689. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y., Ma K., Lyu H., Huang Y., Liu H., Liu L. Genetic manipulation of the COP9 signalosome subunit PfCsnE leads to the discovery of pestaloficins in Pestalotiopsis fici. Org Lett. 2017;19:4700–4703. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M.H., Li Q.Q., Zhang C.H., Zhang N., Cui Z.H., Huang L.Q. An ethnopharmacological investigation of medicinal Salvia plants (Lamiaceae) in China. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2013;4:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu N., Wang S., Lou H.X. A new pimarane-type diterpenoid from moss Pseudoleskeella papillosa (Lindb.) Kindb. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2012;3:256–259. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen S., Zhang Y., Niu S., Liu X., Che Y. Cytotoxic cleistanthane and cassane diterpenoids from the entomogenous fungus Paraconiothyrium hawaiiense. J Nat Prod. 2014;77:1513–1518. doi: 10.1021/np500302e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen S., Zhang Y., Zhao C., Ren F., Liu X., Che Y. Hawaiinolides E--G, cytotoxic cassane and cleistanthane diterpenoids from the entomogenous fungus Paraconiothyrium hawaiiense. Fitoterapia. 2014;99:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris S.A., Curotto J.E., Zink D.L., Dreikorn S., Jenkins R., bills G.F. Sonomolides A and B, new broad spectrum antifungal agents isolated from a coprophilous fungus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:9101–9104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiono Yoshihito, Ogata Kota, Koseki Takuya, Murayama Tetsuya, Funakoshi T. A cleistanthane diterpene from a marine-derived Fusarium species under submerged fermentation. Z Naturforsch. 2010;65b:753–756. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F., Ma J., Li C.J., Yang J.Z., Zhang D., Chen X.G. Bioactive isopimarane diterpenoids from the stems of Euonymus oblongifolius. Phytochemistry. 2017;135:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allard P.M., Martin M.T., Dau M.E., Leyssen P., Gueritte F., Litaudon M. Trigocherrin A, the first natural chlorinated daphnane diterpene orthoester from Trigonostemon cherrieri. Org Lett. 2012;14:342–345. doi: 10.1021/ol2030907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L., Luo R.H., Wang F., Jiang M.Y., Dong Z.J., Yang L.M. Highly functionalized daphnane diterpenoids from Trigonostemon thyrsoideum. Org Lett. 2010;12:152–155. doi: 10.1021/ol9025638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L., Luo R.H., Wang F., Dong Z.J., Yang L.M., Zheng Y.T. Daphnane diterpenoids isolated from Trigonostemon thyrsoideum as HIV-1 antivirals. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1879–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirk D.N. The chiroptical properties of carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:777–818. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai J., Chen H., Fang Z.F., Yu S.S., Wang W.J., Liu Y. Sesquiterpenes from the roots of Illicium dunnianum. Phytochemistry. 2012;80:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayer W.A., Khan A.Q. Zythiostromic acids, diterpenoids from an antifungal Zythiostroma species associated with aspen. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:1647–1652. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters R.J. Two rings in them all: the labdane-related diterpenoids. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1521–1530. doi: 10.1039/c0np00019a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Y., Honzatko R.B., Peters R.J. Terpenoid synthase structures: a so far incomplete view of complex catalysis. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:1153–1175. doi: 10.1039/c2np20059g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khasigov P.Z., Podobed O.V., Gracheva T.S., Salbiev K.D., Grachev S.V., Berezov T.T. Role of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in tumor invasion and metastasis. Biochemistry. 2003;68:711–717. doi: 10.1023/a:1025051214001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park M., Han J., Lee C.S., Soo B.H., Lim K.M., Ha H. Carnosic acid, a phenolic diterpene from rosemary, prevents UV-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinases in human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:336–341. doi: 10.1111/exd.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma S.-G., Tang W.-Z., Liu Y.-X., Hu Y.-C., Yu S.-S., Zhang Y. Prenylated C6–C3 compounds with molecular diversity from the roots of Illicium oligandrum. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu J., Fang L., Ren X.-D., Liu Y., Yu S.-S., Li L. Bisindole alkaloids with neural anti-inflammatory activity from Gelsemium elegans. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:2203–2209. doi: 10.1021/np4005536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu Y., Ma S., Li J., Yu S., Qu J., Liu J. Targeted isolation and structure elucidation of stilbene glycosides from the bark of Lysidice brevicalyx Wei guided by biological and chemical screening. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1800–1805. doi: 10.1021/np800083x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material