Abstract

PURPOSE: Here we demonstrate the potential of multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT), a new non-invasive structural and functional imaging modality, to track the growth and changes in blood oxygen saturation (sO2) in orthotopic glioblastoma (GBMs) and the surrounding brain tissues upon administration of a vascular disruptive agent (VDA). METHODS: Nude mice injected with U87MG tumor cells were longitudinally monitored for the development of orthotopic GBMs up to 15 days and observed for changes in sO2 upon administration of combretastatin A4 phosphate (CA4P, 30 mg/kg), an FDA approved VDA for treating solid tumors. We employed a newly-developed non-negative constrained approach for combined MSOT image reconstruction and unmixing in order to quantitatively map sO2 in whole mouse brains. RESULTS: Upon longitudinal monitoring, tumors could be detected in mouse brains using single-wavelength data as early as 6 days post tumor cell inoculation. Fifteen days post-inoculation, tumors had higher sO2 of 63 ± 11% (n = 5, P < .05) against 48 ± 7% in the corresponding contralateral brain, indicating their hyperoxic status. In a different set of animals, 42 days post-inoculation, tumors had lower sO2 of 42 ± 5% against 49 ± 4% (n = 3, P < .05) in the contralateral side, indicating their hypoxic status. Upon CA4P administration, sO2 in 15 days post-inoculation tumors dropped from 61 ± 9% to 36 ± 1% (n = 4, P < .01) within one hour, then reverted to pre CA4P treatment values (63 ± 6%) and remained constant until the last observation time point of 6 hours. CONCLUSION: With the help of advanced post processing algorithms, MSOT was capable of monitoring the tumor growth and assessing hemodynamic changes upon administration of VDAs in orthotopic GBMs.

Introduction

Optoacoustic tomography (OT) is emerging as an indispensable tool, both preclinically and clinically, to non-invasively visualize hemoglobin concentration and oxygenation. Its capacity to visualize anatomical structures and distinguish between different endogenous chromophores, including oxy and deoxy-hemoglobin, based on their distinct absorption spectra, with both high spatial and temporal resolution at centimeter-scale depths in living tissues [1], [2], opens new avenues for studying many oxygenation-related pathologies [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. In preclinical studies, OT has been chiefly employed for visualization of morphology and oxygenation status of tumor xenografts in order to unveil the link between poor oxygenation and therapeutic outcomes. Static OT readouts from subcutaneous tumors offered insights into the vessel developments in tumor [12], [13], visualize the hemodynamic changes in response to vascular disrupting therapeutic agents [8], [14] and predict therapeutic response [15] and recurrence [16]. In addition, dynamic OT readouts facilitated the acquisition of vascular information to understand spatial heterogeneity and evolution, which could ultimately serve for cancer diagnosis and staging [7]. However, subcutaneous tumor models are often not capable of simulating the cancer environment as good as their orthotopic counterparts [17], [18], [19], thus questioning their utility as essential systems in studying tumor biology or identifying therapeutic agents. Anatomical and functional OT imaging of orthotopic tumors may therefore help with better simulating human malignancies and understanding their microenvironment.

Previously, we have demonstrated the utility of Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography (MSOT) to investigate orthotopic brain tumors using exogenous contrast agent [20]. Burton et al. [2] and Ni et al. [21] have investigated the utility MSOT for identifying hypoxic areas in mouse brain. In the current study, we investigated the performance of MSOT method in identifying tumors from the midst of brain tissues and understand their vascular dynamics upon administration of combretastatin A4 phosphate (CA4P), an FDA approved vascular disruptive agent for treating solid tumors. For this, an orthotopic U87MG glioma model was employed, which has been extensively used in preclinical studies to identify therapeutic agents [22], [23] and whose molecular profile is known to simulate a subclass of human glioblastoma [24]. Additionally, in order to quantitatively map sO2 in whole mouse brains, we employed a newly-developed non-negative constrained approach for combined MSOT image reconstruction and unmixing [25], the advantage of which compared to state-of-the-art back projection methods being reduced critical image artifacts, thus maximizing the available information. Specifically, the objectives of this study have been to investigate the MSOT performance in identifying orthotopic gliomas based on single wavelength information, evaluate their growth over time, visualize sO2 in the tumor versus the rest of the brain and investigate hemodynamic changes upon administration of a vascular disruptive agent.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model and Procedures

All animals were housed in Biological Resource Centre, which is an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited facility. All procedures performed on animal models were carried out under guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) as approved in the protocol #140898 and #151085. The orthotopic tumor model was created by stereotaxic injection of U87MG cells into the brains of female NCr nude mice (age: 6–7 weeks old). In brief, 5–6 × 106 cells/mL were prepared in sterile 1× PBS. The animal was anesthetized under 2–3% isoflurane. The head was fixed to a digital stereotaxic system (Stoelting Co.) and a burr hole was made on the skull using a 23G sterile needle at 2 mm behind bregma, 1.5 mm to the right from the midline. A 10 μl NANOFIL syringe (World Precision Instruments, Inc.) pre-filled with cells was prepared and the needle was inserted 3 mm into the brain parenchyma through the burr whole. Five μl volume of cells was injected at a rate of 1 μl/min using an infusion pump (KD Scientific Inc.). After injection, the needle was removed, the burr hole was covered with bone wax, and the incision sutured with poly-lysine thread. The animals were given analgesics (Buprenorphine) and antibiotics (Enrofloxacin) over 5 days post-surgery. Tumor growth was monitored up to 15 days using MSOT. Vascular perturbation study was done by injecting 30 mg/kg of Fosbretabulin (CA4P, SelleckChem) intravenously.

Animal Preparation for Imaging

All animals were imaged under 2–3% isoflurane using medical air. For MSOT imaging of the brain, the animal was placed in supine position in a holder. Coupling gel was applied to the region of interest. The animal was wrapped in a thin polyethylene membrane and introduced into the water chamber (maintained at 34°C) for imaging. Throughout the imaging session, all animals were maintained at a respiration rate of 70 to 90 breaths per minute by manually adjusting the isoflurane.

MSOT Imaging

MSOT imaging was performed using the inVision 512 small-animal MSOT system (iThera Medical GmbH, Munich, Germany). The system consists of a 512-element concave transducer array with a central frequency of 5 MHz spanning a circular arc of 270° to detect optoacoustic signals. Light excitation was provided with a tunable (700–900 nm) optical parametric oscillator (OPO) laser guided via a fiber bundle to the sample. The transducer array and fiber bundle output arms were submerged in a water bath maintained at 34°C. The animal was moved through the transducer array along its axis to acquire information as transverse image slices across the desired volume of interest (VOI). For data acquisition, a VOI of multiple transverse slices was set up with a step size of 0.5 mm and the acquired optoacoustic signals were averaged over 10 consecutive laser pulses for each recorded wavelength (715, 730, 760, 800, and 850 nm).

Image Processing and Data Analysis

In order to facilitate quantitative data analysis and avoid negative value artifacts commonly present in optoacoustic images reconstructed with back projection algorithms [26], we employed a combined model-based reconstruction and unmixing framework incorporating non-negative constrained inversion [25]. Basically, the method is based on the discretization of the optoacoustic forward model to build a linear set of equations, associated to a model-matrix, that represent the recorded pressure values at different locations and different wavelengths. The reconstruction-unmixing process is based on the least square minimization of the measured signals and those predicted by the model, where a non-negative constrain is imposed to avoid the appearance of negative values in the chromophore(s) of interest. Total hemoglobin (HbT) distribution was then calculated by adding the unmixed oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin values and the sO2 fraction was calculated by dividing the unmixed oxy-hemoglobin values with HbT. For comparison, the images were also reconstructed using the default back projection based algorithm followed by spectral unmixing using linear regression algorithm [27], [28], both available as a part of the data analysis software of the scanner.

In order to demonstrate the ability of MSOT to identify the anatomical location of tumors from the midst of normal brain tissue, difference in the reconstructed single wavelength images at 850 and 800 nm (Diff850–800nm) was computed using Image J. Tumors appeared as hyperintense signals on the right cortex, the dimensions of which were measured manually on Image J at the largest cross section of the tumor. Tumor volume was estimated as 1/2(Length × Width2).

MR Imaging and Data Analysis

Magnetic resonance imaging was carried out on a 7 Tesla MRI (ClinScan, Bruker Bio Spin GmbH) with a 72 mm volume transmit/receive coil along with a mouse brain array coil (Rx). After localizing the brain at the isocentre of the magnet, anatomy of the growing tumor was observed using a T2 weighted turbo-spin echo sequence. The MRI imaging was performed with TR/TE = 4050/33 ms. Refocusing pulse FA = 180o; in-plane resolution of 70×70 μm, 0.5 mm transverse slice thickness, 32 slices, 2 averages per slice. The tumor volume was manually segmented and measured from the hyper-intense lesion using ImageJ.

Histology

Brain tissues were harvested after euthanizing mice by cervical dislocation and fixed using 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma). Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks and sectioned into slices of 5 μm thickness. Consecutive sections of the brain were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for evaluation of tumor morphology and cellularity, and to bright field immunohistochemistry for markers of vascularity – CD34 (EP373Y, Abcam) and hypoxia - Carbonic anhydase IX (CAIX) enzyme (NB100–417, Novus Biologicals). After deparrafinizing and dehydrating, heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed using Bond™ Epitope Retrieval Solution (pH 9.6) for 40 min at 100°C. Slides were then incubated with the primary antibody followed by secondary antibody (goat anti-rat HRP, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; 1:50) for 30 min. Bond™ Mixed DAB Refine was applied for 5 min, and rinsed with deionized water to stop the DAB reaction and counter stained with hematoxylin. Slides were finally dehydrated and mounted in synthetic mounting media. Bright field images of slides were taken using Nikon NiE: Ri2 microscope with DS-Ri2 camera using NIS elements 4.5 software. Tissue sections stained for H&E and CD34 were analyzed by board-certified pathologist. % areas of sections positively stained for CAIX were analyzed using Image J.

Statistical Analysis

Region of interest (ROI)-was drawn manually using ImageJ around the tumors versus healthy brain tissue from the contralateral side on the sO2 fraction maps to derive the sO2 fraction values. All data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Graphs were plotted using Graph Pad PRISM® 7.01. Paired t-test was used to assess the significance of difference in sO2 fraction values obtained using MSOT between tumor and contralateral side across the animals. One way ANOVA test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to assess the significance of sO2 changes upon CA4P administration across different time points for tumor and contralateral side. Unpaired t-test was used for assessing the significance of difference in CAIX (hypoxia marker) stained areas across different time points post CA4P administration. Data was considered significant with P < 0.05.

Results

Anatomical Imaging of Orthotopic Glioblastoma Using MSOT

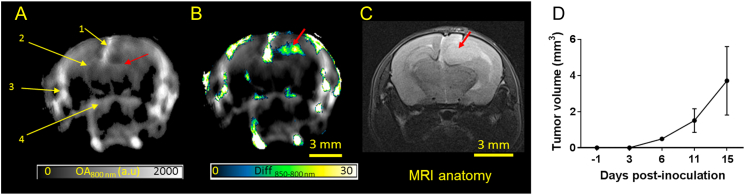

Three nCr nude mice with orthotopic U87 glioblastoma on the right cortex were used to examine the performance of MSOT to track the tumor growth and development. Strong optoacoustic signals were seen clearly in major blood vessels, such as superior sagittal sinus (SSS, 1), middle cerebral artery (MCA, 2), superficial temporal arteries (TA, 3) and posterior communicating artery (PCA, 4) in the brain cross-sectional image at bregma +2 mm recorded at a wavelength of 800 nm (Figure 1A), the isosbestic point of hemoglobin absorption in the NIR region. Apart from the major blood vessels, strong optoacoustic signals could be seen from the cortex, in particular the right cortex and altered symmetry in right MCA (red arrow) suggesting the presence of tumor. The difference between the single-wavelength optoacoustic images acquired at 850 and 800 nm ((Diff850–800 nm) clearly revealed the tumor location (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the shape of the hyperintense signals was similar to shape of the tumor observed on MRI anatomy scan (Figure 1C). Moreover, the tumor dimensions measured by MSOT across the largest cross section were similar to those measured by the T2-weighted MRI anatomical images (Figure S1). The same strategy was applied to images acquired pre and 3, 6 and 11 days post tumor cell inoculation (Figure S2) to track the tumor growth and calculate the increase in the tumor volume (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Anatomical imaging of orthotopic glioblastoma in mice using MSOT. (A) In vivo single wavelength (800 nm) optoacoustic image depicting the anatomy of an intact mouse brain with U87MG glioblastoma. The slice is at bregma +2 mm. Brain structures such as superior sagittal sinus (SSS, 1), middle cerebral artery (MCA, 2), superficial temporal arteries (TA, 3) and posterior communicating artery (PCA, 4) and altered symmetry at the right MCA (red arrow) are visible. (B) Difference of the optoacoustic images acquired at 850 and 800 nm, highlighting the tumor location and shape (red arrow). (C) T2 weighted MRI anatomy image of the corresponding brain slice with the hyperintense lesion (red arrow) representing the tumor. (D) Graph showing increase in tumor volume across different days post tumor inoculation calculated using the difference in OA signals at 850 and 800 nm (n = 3).

Functional Imaging of Orthotopic Glioblastoma Using MSOT

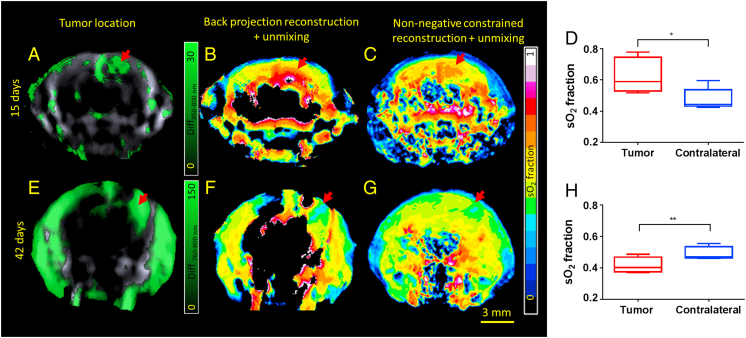

As oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin are characterized by unique absorption spectra in the NIR region, MSOT can distinguish between the different oxygenation states in blood, allowing for reconstructing the maps of sO2 in the brain. However, it could be readily recognized that large areas of the brain are missing information when estimating the sO2 values with the standard back-projection reconstruction method and setting negative image values to zero (Figure 2B). In contrary, the non-negative constrained reconstruction and unmixing method was able to render reasonable sO2 values in the entire brain (Figure 2C). Maps of single wavelength optoacoustic image at 800 nm, oxy-, deoxy-hemoglobin and sO2 obtained by non-negative constrained reconstruction and unmixing method for a representative animal are provided in Figure S3. The tumor mass (15 days post-inoculation, n = 5), was observed to have higher sO2 of 63 ± 11% as compared with 48 ± 7% (P < 0.05, paired t-test) in the corresponding contralateral side (Figure 2D) indicating their hyperoxic status. In older tumors (42 days post-inoculation, n = 3), the sO2 was 42 ± 5% against 49 ± 4% (P < 0.05, paired t-test) in the contralateral side, indicating their hypoxic status (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Functional Imaging of Orthotopic Glioblastoma. Panels A & E show the location of the tumor in a representative animal 15 and 42 days post inoculation respectively. Panels B & F show the sO2 fraction map after reconstruction using back-projection and unmixing using linear regression of the corresponding animals. Panels C and G denote the sO2 fraction map after combined non-negative constrained reconstruction and unmixing in the corresponding animals. Panels D and H show the sO2 values in the tumor and the contralateral side of the brain in animals 15 (n = 5) and 42 (n = 3) day post inoculation. sO2 values between the tumor and contralateral side were found to be statistically significantly different using paired t-test. * - P < 0.05; ** - P < 0.01.

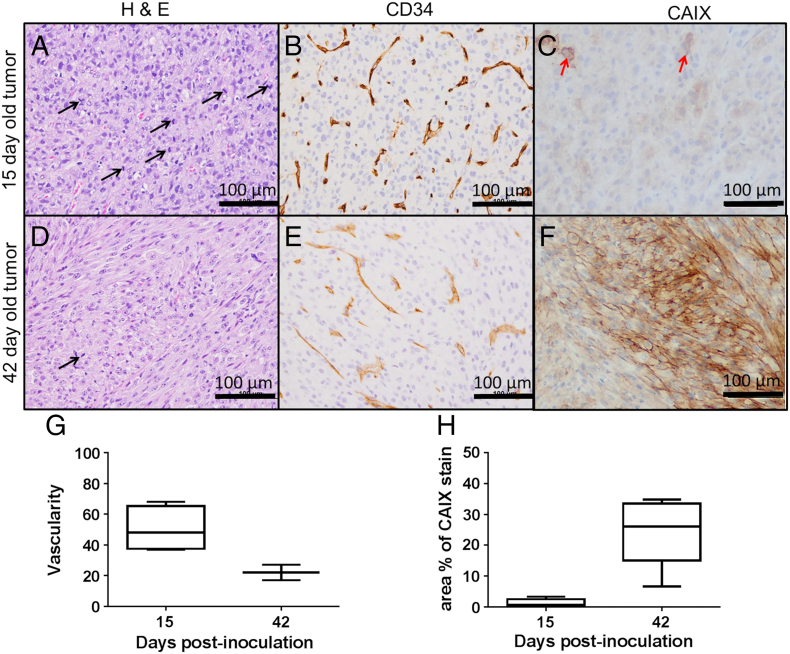

In order to validate the sO2 values of the tumors observed with MSOT, histological analysis was performed on tumors at two time points. The higher sO2 in tumors 15 days post-inoculation could be attributed to the presence of rapidly dividing (indicated by increased number of mitotic cells, Figure 3A) poorly differentiated neoplastic cells forming neovasculature to draw sufficient nutrients and oxygen to support their growth. This is further corroborated by the higher degree of vascularity (measured by the number of blood vessels per unit field of view), as indicated by CD34 stain (Figure 3, B and G), and smaller fraction of the tumor positively stained for CAIX (Figure 3, C and H). The lower sO2 in tumors 42 days post inoculation could be attributed to well differentiated neoplastic cells with fewer mitotic cells indicating a slack in their growth and spread (Figure 3D). Lesser degree of vascularity as indicated by CD34 staining (Figure 3, E and G) compared to tumors that were 15 day post inoculation and increased fraction of CAIX stained tumor areas (Figure 3, F and H) corroborate the values observed using MSOT.

Figure 3.

Histological validation of sO2 values observed on MSOT. Panels A & D show mitotic cells (black arrow) in the histological sections of H&E stained tumors 15 and 42 days post inoculation. Panels B & E show corresponding tissue sections of tumors stained for CD34, a marker for neovasculature and panels C and F, areas stained for CAIX (a marker for hypoxia). Panels G and H shows the quantification of CD34 and CAIX stains respectively in tumors 15 and 42 days post inoculation. Red arrow indicates hypoxic cells.

MSOT Tracks Hemodynamic Changes in Tumor Upon Administration of Therapeutic Agent

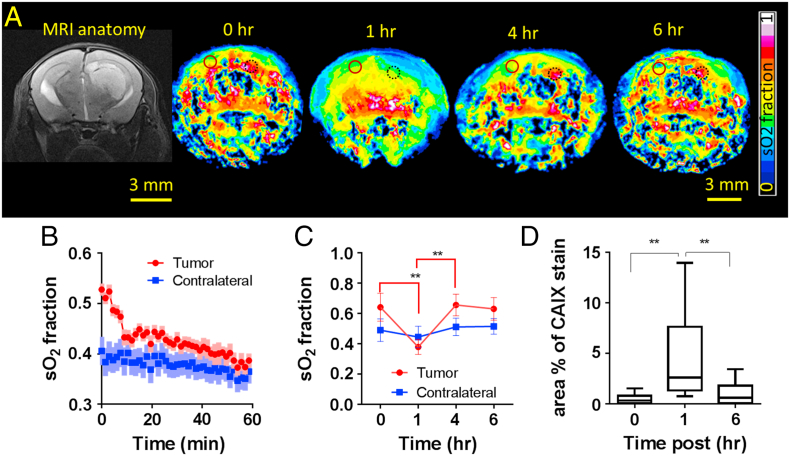

To investigate the utility of MSOT for tracking hemodynamic changes as a part of treatment monitoring, we administered 30 mg/kg of combretastatin A4 phosphate (CA4P), a vascular disruptive agent into 4 animals with tumors that were 15 days post-inoculation. CA4P binds to tubulin and affects the cytoskeleton and morphology of endothelial cells resulting in increased vascular permeability to macromolecules resulting in increased interstitial pressure and thus, shutdown of blood flow [29], [30]. Dynamic changes in sO2 post CA4P administration is demonstrated in Figure 4A. Immediately after CA4P administration, the sO2 dropped sharply from 61 ± 9% within the first ten minutes and gradually after that to reach 36 ± 1% (P < .01) at the end of 1 hour (4B and 4C). This drop was attributed by rapid decrease in oxy-hemoglobin levels and increase in deoxy-hemoglobin levels in the tumor (Figure S4), indicative of a disruption to the blood flow leading to fast depletion of the available oxygen and onset of transient hypoxia. Also, a sharp decrease in total hemoglobin was observed within 10 minutes and a 20% decrease over 1 hour (Figure S4). As CA4P is known to have a disruptive effect mainly on the irregularly formed neovasculatures, no significant changes in total hemoglobin or sO2 were observed on the contralateral side (Figure 4B). Four hours post CA4P administration, sO2 in the tumors reverted to pre CA4P treatment values (63 ± 6%) and remained the same until the last observation time of 6 hours (Figure 4C). This suggested the recovery of blood vessels post treatment. In order to validate the changes in sO2 of the tumors observed using MSOT, histological analysis were performed on tumors at 0, 1 and 6 hours. There was a significant increase in CAIX stained areas at 1 hour compared to 0 and 6 hours post CA4P administration (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Real-time hemodynamic changes in the tumor upon administration of CA4P. Panel A shows the MRI anatomical reference of the tumor, followed by sO2 maps of a slice of brain showing the largest cross section of the tumor at time points 0, 1, 4 and 6 h. post CA4P administration. Panel B shows the real-time sO2 changes in the tumor and contralateral brain occurring immediately post CA4P administration over 1 hour in a representative animal. SD is represented by lighter shades on the graph. Panel C shows the real-time sO2 changes in the tumor and contralateral brain occurring immediately post CA4P administration (n = 4). Panel D shows the quantification of hypoxia in tumors using CAIX as a marker at times 0 (n = 3), 1 (n = 4) and 6 h. (n = 3) post CA4P administration. Unpaired t-test showed statistically significant difference in CAIX staining at 1 hour post CA4P administration compared to 0 and 6 hours. ** ‐ P > 0.01. Black dotted circle and Red full circle denote the ROIs drawn at the tumor and contralateral brain respectively to compute the sO2.

Discussion

Optoacoustic imaging has been emerging as a powerful tool in revealing sO2 with high spatial resolution and sensitivity. While previously published works have shown sO2 measurement in the superficial cortical vasculature of brain [31], imaging sO2 in deeper regions is severely hampered by the strong light attenuation in brain tissue and its wavelength dependent nature, resulting in the so-called spectral coloring effects that can significantly affect the unmixing results. Advanced reconstruction and unmixing approaches that can accurately account for the complex underlying physical phenomena behind optoacoustic signal generation are therefore essential for accurate estimation of sO2 values. Herein, we experimentally showed that a combined model-based reconstruction and unmixing method incorporating non-negative constrains can render reasonable sO2 values across the entire mouse brain. Furthermore, upon analyzing the images showing difference in single wavelength images acquired at 715, 730, 760, 800 and 850 nm, hyperintense signals found on Diff850–800 nm images were useful in locating the tumors while the others were not very useful for identifying hyperoxic tumors. The higher absorption of oxygenated hemoglobin at 850 nm as compared to other wavelengths and its abundance in hyperoxic tumors could have resulted in hyperintense signal in Diff850–800 nm images at the tumor region. Similarly, the higher absorption of deoxyhemoglobin at 760 nm as compared to other wavelengths and its abundance in the hyperoxic tumors could have resulted in hyperintense signal in Diff760–800 nm images at the tumor region.

For the first time to our knowledge, we were able to provide a direct comparison of the sO2 in orthotopic glioblastoma against the healthy contralateral side in whole-brain cross sections. The brain area covered with MSOT is thus comparable to that of small animal CT or MR imaging, but it can additionally provide enhanced functional information. The spatial resolution of MSOT in the range of 150 μm only allows for distinguishing major blood vessels, yet sO2 could still be estimated reliably across the entire brain by relying on spatially averaged signals. This is evinced by the ability of MSOT to pick up sO2 in hyperoxic (15 days post tumor inoculation) and hypoxic tumors (42 days post tumor inoculation) against the normoxic contralateral brain and the validation by histological studies.

The real-time imaging capabilities of MSOT represent yet another significant advantage of the technique to evaluate the kinetics and course of action of vascular targeting drugs on orthotopic glioblastoma. Upon CA4P administration, as expected, tumors showed a significant decrease in sO2 up to 1 hour due to the shutdown of tumor vasculature and recovered almost completely after 4 hours. This is not surprising as a low dose (30 mg/kg) of CA4P is known to result in partial or complete recovery sooner or later after instantaneous reduction in blood flow as demonstrated by us [32] and others [33], [34]. While different techniques like MRI, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and fluorescence imaging (FLI) have been used previously to understand the mechanism of action or to evaluate the performance of vascular targeting drugs on tumors [12], [35], they have only offered an indirect estimation of the vasculature damage by evaluating the consequences of vascular shutdown. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound does offer a direct estimation of the damage to the vasculature resulting from the treatment [36], however with the help of exogenous contrast agents. On the other hand, high resolution intravital microscopy [37] and photoacoustic microscopy [12], which can provide a direct measure of the vascular growth and shut down upon administration of vascular disruptive agents (VDA), are not capable of deep tissue penetration attained by MSOT. Rich et al. [8] and Bar-Zion et al. [9] have used optoacoustic imaging to investigate the hemodynamics following administration of vascular disruptive agents in superficial xenograft tumors. In the current study, we were able to measure directly the drug-evoked rapid hemodynamic changes in the entire tumor as well as the normal contralateral brain at a reasonable (mesoscopic-scale) spatial resolution of 150 μm. This performance makes MSOT highly appealing for preclinical evaluation of the drug where it is important to understand the effects of the drug on the normal tissue as well in order to evaluate its toxicity on healthy tissues.

There were several limitations to our study. Firstly, the concept of using differences in single wavelength optoacoustic images to perform anatomical imaging of orthotopic glioblastoma was tested on fewer animals (n = 3 each for hyperoxic and hypoxic tumors) with cortical tumors. The sample size should be increased to further validate the hypothesis in tumors located in different regions of the brain and thus to be eventually useful in tumor volume calculation. Moreover, in tumors with mixed hyperoxic and hypoxic areas, this strategy may indicate only parts of the tumor and not the entire tumor, thus restricting the method to tracking of early tumor growth. Secondly, though the combined non-negative constrained reconstruction and unmixing method helped in extracting sO2 values from most parts of the brain, it could not be of much help in regions below thalamus consistently across all animals. This can be attributed to the strong light attenuation in the brain. A number of efforts are being made to minimize these limitations, including improving the instrumentation, data acquisition and post-processing [7], [38], [39], [40]. Thirdly, we have used CA4P as a vascular perturbation agent looking at its short term effect rather than its long term effect as a therapeutic agent. Investigating long term treatment outcomes may help to establish the potential of MSOT imaging to predict the therapeutic responses. Finally, as no gold standard exists for validating the in vivo deep-tissue sO2 measurements, the closest validation we provided was histological evidences at cellular scale to support the hemodynamic changes.

Conclusion

In summary, for the first time, we have demonstrated the capacity of MSOT to visualize the location and anatomy of the early tumors and sO2 in the whole mouse brain in the presence of a glioblastoma. The study emphasizes the importance of post processing algorithms to improve the image quality as well as maximize the information available from this novel imaging modality. The study also establishes MSOT as a treatment monitoring modality by being able to image the hemodynamic changes occurring upon administration of vascular disruptive agent.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Advanced Molecular Pathology Lab (AMPL), Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB), A*STAR, Singapore for their help with the tissue preparation and IHC staining.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the European Research Council Consolidator grant ERC-2015-CoG-682379 (D.R.) and A*STAR (Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore) Biomedical Research Council intramural funds and research collaborative agreement (RCA) with iThera Medical GmbH (M.O.).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2018.07.001.

Contributor Information

Daniel Razansky, Email: dr@tum.de.

Malini Olivo, Email: malini_olivo@sbic.a-star.edu.sg.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

Supplementary material

Video of Dynamic changes in saturated oxygen in tumor and contralateral brain upon VDA treatment over 1 hour

References

- 1.Deán-Ben XL, López-Schier H, Razansky D. Optoacoustic micro-tomography at 100 volumes per second. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6850. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06554-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton NC, Patel M, Morscher S, Driessen WH, Claussen J, Beziere N, Jetzfellner T, Taruttis A, Razansky D, Bednar B. Multispectral opto-acoustic tomography (MSOT) of the brain and glioblastoma characterization. Neuroimage. 2013;65:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNally LR, Mezera M, Morgan DE, Frederick PJ, Yang ES, Eltoum I-E, Grizzle WE. Current and Emerging Clinical Applications of Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography (MSOT) in Oncology. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(14):3432–3439. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reber J, Willershäuser M, Karlas A, Paul-Yuan K, Diot G, Franz D, Fromme T, Ovsepian SV, Bézière N, Dubikovskaya E. Non-invasive measurement of brown fat metabolism based on optoacoustic imaging of hemoglobin gradients. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):689–701.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esenaliev RO. Optoacoustic Monitoring of Physiologic Variables. Front Physiol. 2017;8:1030. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attia ABE, Chuah SY, Razansky D, Ho CJH, Malempati P, Dinish U, Bi R, Fu CY, Ford SJ, Lee JS-S. Noninvasive real-time characterization of non-melanoma skin cancers with handheld optoacoustic probes. Photoacoustics. 2017;7:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomaszewski MR, Gonzalez IQ, O'Connor JP, Abeyakoon O, Parker GJ, Williams KJ, Gilbert FJ, Bohndiek SE. Oxygen enhanced optoacoustic tomography (OE-OT) reveals vascular dynamics in murine models of prostate cancer. Theranostics. 2017;7(11):2900–2913. doi: 10.7150/thno.19841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich LJ, Seshadri M. Photoacoustic Imaging of Vascular Hemodynamics: Validation with Blood Oxygenation Level–Dependent MR Imaging. Radiology. 2015;275(1):110–118. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bar-Zion A, Yin M, Adam D, Foster FS. Functional Flow Patterns and Static Blood Pooling in Tumors Revealed by Combined Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Photoacoustic Imaging. Cancer Res. 2016;76(15):4320–4331. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menezes GLG, Pijnappel RM, Meeuwis C, Bisschops R, Veltman J, Lavin PT, Vijver MJvd, Mann RM. Downgrading of breast masses suspicious for cancer by using optoacoustic breast imaging. Radiology. 2018;0(0):170500. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018170500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aguirre J, Schwarz M, Garzorz N, Omar M, Buehler A, Eyerich K, Ntziachristos V. Precision assessment of label-free psoriasis biomarkers with ultra-broadband optoacoustic mesoscopy. Nat Biomed Eng. 2017;1 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laufer J, Johnson P, Zhang E, Treeby B, Cox B, Pedley B, Beard P. In vivo preclinical photoacoustic imaging of tumor vasculature development and therapy. J Biomed Opt. 2012;17(5):0560161–0560168. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.056016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerling M, Zhao Y, Nania S, Norberg KJ, Verbeke CS, Englert B, Kuiper RV, Bergstrom A, Hassan M, Neesse A. Real-time assessment of tissue hypoxia in vivo with combined photoacoustics and high-frequency ultrasound. Theranostics. 2014;4(6):604–613. doi: 10.7150/thno.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dey S, Kumari S, Kalainayakan SP, Campbell J, Ghosh P, Zhou H, FitzGerald KE, Li M, Mason RP, Zhang L. The vascular disrupting agent combretastatin A-4 phosphate causes prolonged elevation of proteins involved in heme flux and function in resistant tumor cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9(3):4090–4101. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rich LJ, Seshadri M. Photoacoustic monitoring of tumor and normal tissue response to radiation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21237. doi: 10.1038/srep21237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallidi S, Watanabe K, Timerman D, Schoenfeld D, Hasan T. Prediction of tumor recurrence and therapy monitoring using ultrasound-guided photoacoustic imaging. Theranostics. 2015;5(3):289–301. doi: 10.7150/thno.10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du Q, Jiang L, Wang XQ, Pan W, She FF, Chen YL. Establishment of and comparison between orthotopic xenograft and subcutaneous xenograft models of gallbladder carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(8):3747–3752. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.8.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao X, Li L, Starr TK, Subramanian S. Tumor location impacts immune response in mouse models of colon cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(33):54775–54787. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Toneri M, Ma H, Yang Z, Bouvet M, Goto Y, Seki N, Hoffman RM. Real-Time GFP Intravital Imaging of the Differences in Cellular and Angiogenic Behavior of Subcutaneous and Orthotopic Nude-Mouse Models of Human PC-3 Prostate Cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117(11):2546–2551. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attia AB, Ho CJ, Chandrasekharan P, Balasundaram G, Tay HC, Burton NC, Chuang KH, Ntziachristos V, Olivo M. Multispectral optoacoustic and MRI coregistration for molecular imaging of orthotopic model of human glioblastoma. J Biophotonics. 2016;9(7):701–708. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201500321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ni R, Vaas M, Ren W, Klohs J. Noninvasive detection of acute cerebral hypoxia and subsequent matrix-metalloproteinase activity in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia using multispectral-optoacoustic-tomography. Neurophotonics. 2018;5(1):015005. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.5.1.015005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanihara M, Kawataki T, Oh-Oka K, Mitsuka K, Nakao A, Kinouchi H. Synergistic antitumor effect with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibition and temozolomide in a murine glioma model. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(6):1594–1601. doi: 10.3171/2015.5.JNS141901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szabo E, Phillips DJ, Droste M, Marti A, Kretzschmar T, Shamshiev A, Weller M. Anti-tumor activity of DLX1008, an anti-VEGFA antibody fragment with low picomolar affinity, in human glioma models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;365:422–429. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.246249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shankavaram UT, Bredel M, Burgan WE, Carter D, Tofilon P, Camphausen K. Molecular profiling indicates orthotopic xenograft of glioma cell lines simulate a subclass of human glioblastoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(3):545–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding L, Ben XLD, Burton NC, Sobol RW, Ntziachristos V, Razansky D. Constrained Inversion and Spectral Unmixing in Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2017;36:1676–1685. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2017.2686006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding L, Deán-Ben XL, Lutzweiler C, Razansky D, Ntziachristos V. Efficient non-negative constrained model-based inversion in optoacoustic tomography. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60(17):6733–6750. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/17/6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu M, Wang LV. Universal back-projection algorithm for photoacoustic computed tomography. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005;71(1 Pt 2):016706. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.016706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Razansky D. Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography - Volumetric Color Hearing in Real Time. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2012;18(3):1234–1243. [Google Scholar]

- 29.West CM, Price P. Combretastatin A4 phosphate. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15(3):179–187. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tozer GM, Kanthou C, Parkins CS, Hill SA. The biology of the combretastatins as tumour vascular targeting agents. Int J Exp Pathol. 2002;83(1):21–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2002.00211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao J, Wang L, Yang J-M, Maslov KI, Wong TT, Li L, Huang C-H, Zou J, Wang LV. High-speed label-free functional photoacoustic microscopy of mouse brain in action. Nat Methods. 2015;12(5):407–410. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bi R, Balasundaram G, Jeon S, Tay HC, Pu Y, Li X, Moothanchery M, Kim C, Olivo M. Photoacoustic microscopy for evaluating combretastatin A4 phosphate induced vascular disruption in orthotopic glioma. J Biophotonics. 2018 doi: 10.1002/jbio.201700327. p. [e201700327-n/a] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murata R, Overgaard J, Horsman MR. Comparative effects of combretastatin A-4 disodium phosphate and 5, 6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid on blood perfusion in a murine tumour and normal tissues. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77(2):195–204. doi: 10.1080/09553000010007695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rustin G, Price P, Stratford M, Galbraith S, Anderson H, Folkes L, Robbins A, Senna L. Phase I study of weekly intravenous combretastatin A4 phosphate (CA4P): pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.185. 20012099a (abstract 392) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, Mason RP, Gimi B. Dynamic bioluminescence and fluorescence imaging of the effects of the antivascular agent Combretastatin-A4P (CA4P) on brain tumor xenografts. Cancer Lett. 2015;356(2):462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorace AG, Saini R, Mahoney M, Hoyt K. Molecular Ultrasound Imaging Using a Targeted Contrast Agent for Assessing Early Tumor Response to Antiangiogenic Therapy. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(10):1543–1550. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tozer GM, Prise VE, Wilson J, Cemazar M, Shan S, Dewhirst MW, Barber PR, Vojnovic B, Chaplin DJ. Mechanisms associated with tumor vascular shut-down induced by combretastatin A-4 phosphate: intravital microscopy and measurement of vascular permeability. Cancer Res. 2001;61(17):6413–6422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nie L, Cai X, Maslov K, Garcia-Uribe A, Anastasio MA, Wang LV. Photoacoustic tomography through a whole adult human skull with a photon recycler. J Biomed Opt. 2012;17(11):110506. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.11.110506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang C, Nie L, Schoonover RW, Guo Z, Schirra CO, Anastasio MA, Wang LV. Aberration correction for transcranial photoacoustic tomography of primates employing adjunct image data. J Biomed Opt. 2012;17(6):0660161–0660168. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.066016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Estrada H, Rebling J, Turner J, Razansky D. Broadband acoustic properties of a murine skull. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61(5):1932–1946. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/5/1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Video of Dynamic changes in saturated oxygen in tumor and contralateral brain upon VDA treatment over 1 hour