Abstract

Objective

To systematically compare midlife mortality patterns in the United States across racial and ethnic groups during 1999-2016, documenting causes of death and their relative contribution to excess deaths.

Design

Trend analysis of US vital statistics among racial and ethnic groups.

Setting

United States, 1999-2016.

Population

US adults aged 25-64 years (midlife).

Main outcome measures

Absolute changes in mortality measured as average year-to-year change during 1999-2016 and 2012-16; excess deaths attributable to increasing mortality; and relative changes in mortality measured as relative difference between mortality in 1999 versus 2016 and the nadir year versus 2016, and the slope of modeled mortality trends for 1999-2016 and for intervals between joinpoints.

Results

During 1999-2016, all cause mortality in midlife increased not only among non-Hispanic (NH) whites but also among NH American Indians and Alaskan Natives. Although all cause mortality initially decreased among NH blacks, Hispanics, and NH Asians and Pacific Islanders, this trend ended in 2009-11. Drug overdoses were the leading cause of increased mortality in midlife in each population, but mortality also increased for alcohol related conditions, suicides, and organ diseases involving multiple body systems. Although midlife mortality among NH whites increased across a multitude of conditions, a similar trend affected non-white populations. Absolute (year-to-year) increases in midlife mortality among non-white populationsoften matched or exceeded those of NH whites, especially in 2012-16, when the rate of increase intensified for many causes of death. During 1999-2016, NH American Indians and Alaskan Natives experienced large increases in midlife mortality from 12 causes, not only drug overdoses (411.4%) but also hypertensive diseases (269.3%), liver cancer (115.1%), viral hepatitis (112.1%), and diseases of the nervous system (99.8%). NH blacks experienced increased midlife mortality from 17 causes, including drug overdoses (149.6%), homicides (21.4%), hypertensive diseases (15.5%), obesity (120.7%), and liver cancer (49.5%). NH blacks also experienced retrogression: after a period of stable or declining midlife mortality early in 1999-2016, death rates increased for alcohol related liver disease, chronic lower respiratory tract disease, suicides, diabetes, and pancreatic cancer. Among Hispanics, midlife mortality increased across 12 causes, including drug overdoses (80.0%), hypertensive diseases (40.6%), liver cancer (41.8%), suicides (21.9%), obesity (106.6%), and metabolic disorders (60.0%). Retrogression also occurred in this population; after a period of declining mortality, death rates increased for alcohol related liver disease, mental and behavioral disorders involving psychoactive substances, and homicides. NH Asians and Pacific Islanders were least affected by this trend but also experienced increases in midlife mortality from drug overdoses (300.6%), alcohol related liver disease (62.9%), hypertensive diseases (28.3%), and brain cancer (56.6%). The suicide rate in this group increased by 29.7% after 2001. The relative increase in US midlife mortality differed by sex and geography. For example, the relative increase in fatal drug overdoses was greater among women than among men. Although the relative increase in midlife mortality was generally greater in non-metropolitan (ie, rural) areas, the relative increase in drug overdoses among NH whites and Hispanics was greatest in suburban fringe areas of large cities, and among NH blacks was greatest in small cities.

Conclusions

Mortality in midlife in the US has increased across racial-ethnic populations for a variety of conditions, especially in recent years, offsetting years of progress in lowering mortality rates. This reversal carries added consequences for racial groups with high baseline mortality rates, such as for NH blacks and NH American Indians and Alaskan Natives. That death rates are increasing throughout the US population for dozens of conditions signals a systemic cause and warrants prompt action by policy makers to tackle the factors responsible for declining health in the US.

Introduction

Life expectancy in the United States has been decreasing since 2014.1 2 This development, after years of lengthening life expectancy, has been attributed to increasing mortality rates among whites—mainly those aged 25-64 years (midlife).3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Explanations for this trend, which began in the 1990s, typically cite fatal drug overdoses, alcohol related liver disease, and suicides6 7 8—referred to by some as “deaths of despair.”9 12 13 Reports have identified other contributors to increasing midlife mortality (eg, heart and lung disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes), but findings have been inconsistent.4 5 6 11 Few investigators have used a systematic approach to examine causes of death comprehensively.

Mortality patterns in non-white populations are even less clear. Investigators report profound increases in mortality among American Indians and Alaskan Natives of all ages, but they claim the reverse—that mortality rates are decreasing—among blacks, Hispanics, and Asians and Pacific Islanders.4 5 8 11 14 Data across multiple reports suggest, however, that cause specific mortality rates have indeed been increasing among black and Hispanic populations.4 5 8 14 15 16 17 18 Except for recent coverage of the spread of the opioid epidemic to minority populations,19 20 the possibility that midlife mortality might be increasing across racial and ethnic groups, reversing years of progress, has received little public attention.

Previous studies may have missed these reversals in mortality because of the methods used to measure changes in rates, which typically center on comparing current mortality rates with those of a reference year; authors report rates as unchanged if the difference between the two values is not statistically significant. These two point comparisons easily overlook important fluctuations in mortality that occur during intervening years. Trend lines in publications14 17 show mortality rates for some conditions decreasing after 1999, reaching a nadir, and then reversing direction and increasing.

The only way to expose these patterns is to study year-to-year mortality trends. The most current data should be included, given recent surges in mortality rates, but we are aware of no studies on this topic that have examined vital statistics comprehensively beyond 2015. Mortality trends should also be compared by sex, given the evidence that women and men are differentially impacted,5 15 21 22 23 and by geographic settings. Scientific11 21 and lay24 25 26 publications in the US often portray increasing mortality rates in midlife, particularly among the white population, as a rural phenomenon. Whether this is true for populations of color is unclear.

We examined diverse racial groups (non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, Asians and Pacific Islanders, blacks, and whites) and the Hispanic population and compared results by sex and geographic setting; used a systematic, comprehensive approach to detail causes of death; included year-to-year trend analyses over 17 years rather than only relying on two fixed point comparisons; and extended the analysis through 2016.

Methods

We examined age adjusted mortality rates based on the 2000 US standard population for 1999-2016 using the Underlying Cause of Death Detailed Mortality database in the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) platform.27 The agency’s methods for age adjustment are described elsewhere.28 In our analysis we focused on mortality in midlife, defined as deaths at ages 25-64 years (most reports of increasing mortality have studied age groups within these bounds3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11). Per federal regulations,28 we considered mortality rates for any cell (ie, specific cause of death, racial-ethnic group, and year) to be unreliable and therefore did not report them here if they were based on 10-20 deaths (those based on fewer than 10 deaths are suppressed and not publicly available). Causes of death were coded using ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision).29 To avoid inconsistencies in coding with the ninth revision, we excluded deaths before 1999. We obtained mortality rates for all cause mortality, the 113 ICD-10 selected causes of death, and other causes of death with statistically significant increases in mortality during 1999-2016.

Causes of death were divided into 20 broad categories: infectious and parasitic diseases (ICD-10 codes A00-B99); neoplasms (C00-D48); diseases of the blood and immune mechanism (D50-D89); endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (E00-E88); mental and behavioral disorders (F01-F99); diseases of the nervous system (G00-G98), eye and adnexa (H00-H57), ear and mastoid process (H60-H93), circulatory system (I00-I99), respiratory system (J00-J98), digestive system (K00-K92), skin and subcutaneous tissue (L00-L98), musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99), and genitourinary system (N00-N98); pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium (O00-O99); conditions originating in the perinatal period (P00-P96); congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities (Q00-Q99); symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00-R99); codes for special purposes (U00-U99); and external causes (V01-Y89). We broadly classified these as external causes—a category that includes drug overdoses, suicides, and other unintentional and intentional injuries—and as organ diseases. Deaths due to alcohol related causes, as calculated by the National Center for Health Statistics, were also examined.

During 1999-2016 many causes of death exhibited retrogression—a period of stable or declining mortality rates followed by a statistically significant increase in rates. We therefore studied relative increases in mortality rates as two point comparisons, between 1999 and 2016 and between the nadir year and 2016. Non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals determined statistically significant differences in rates. The 95% confidence intervals were provided by CDC WONDER and were calculated using methods outlined in the agency’s technical appendix.28

To assess absolute changes in mortality, we calculated the average year-to-year changes in mortality to account for fluctuating trends between 1999 and 2016. This average provided a measure of absolute rate increases that was comparable across racial-ethnic groups and would not be influenced by differences in baseline mortality rates or population size. We took the average for the 17 years during 1999-2016 and, to capture recent trends, the last five years (2012-16).

To account for random year-to-year variation in mortality data, we used the Joinpoint Regression Program,30 based on the Monte Carlo permutation method, to model the trend lines that best fit the 17 annual mortality rates for each cause of death.31 The model identified points of inflection, or joinpoints—the years during 1999-2016 when changes in mortality trends (slopes) were statistically significant—and calculated the annual percentage rate change (APC, the slope for the interval between the joinpoints) and the average annual percentage change (AAPC, the slope for the entire period (1999-2016) based on the weighted average32 of the APCs). The program generated 95% confidence intervals for the APC and AAPC estimates and conducted tests of significance to determine whether the slope for either differed significantly from zero (ie, whether mortality increased or decreased during the period) and whether the slope (APC) for any interval differed significantly from that of the preceding interval (ie, whether mortality trends changed significantly after the joinpoint year). We considered changes in mortality trends with a P value ≤0.05 to be statistically significant. Joinpoint analysis was not conducted when mortality rates were unavailable for any of the 17 years.

In summary, we examined absolute changes in mortality rates with three measures: the average year-to-year change during 1999-2016 and 2012-16 and excess deaths attributable to increasing mortality rates. We estimated attributable deaths by applying the age adjusted mortality rate of the previous year to the population denominator and comparing with observed deaths for each year between 2000 and 2016. Relative changes (percentage increases) in mortality were examined with four measures: the relative difference (two point comparisons) between mortality rates in 1999 versus 2016 and in the nadir year versus 2016, as well as the relative change in modeled mortality trends for the 1999-2016 period (AAPC) and intervals between joinpoints (APC).

Although the international literature and statistical offices in many countries have moved away from categorizing data by race, US vital statistics continue to be classified by four racial groups established in 1997 by the Office of Management and Budget: American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, black or African American, and white. Ethnicity is classified based on Hispanic origin: Hispanic or Latino, not Hispanic or Latino, or not stated.33 Race and Hispanic origin are treated as distinct concepts: Hispanic and Latino Americans may be of any race.

In our study of US vital statistics we therefore stratified results by sex and for five racial-ethnic groups: Hispanics of all races, non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders, non-Hispanic blacks, and non-Hispanic whitess. As defined by the Office of Management and Budget,33 American Indians or Alaskan Natives include people with origins in (descended from the original peoples of) North and South America (including Central America) and who maintain tribal affiliation or community attachment. Asians include people with origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent (eg, Cambodia), China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, or Vietnam. Pacific Islanders include people with origins in Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands. Whites include people with origins in Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. Blacks include people with origins in the black racial groups of Africa.

These broad categories encompass diverse populations with different backgrounds, but further disaggregation was not feasible owing to small death counts. In 1999, the population (ages 25-64 years) and death counts (all causes), respectively, were 1 113 901 and 4526 for non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, 6 105 344 and 9436 for non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders, 16 999 288 and 101 202 for non-Hispanic blacks, 105 547 575 and 369 217 for non-Hispanic whites, and 15 844 820 and 35 390 for Hispanics. In 2016, the corresponding values were 1 382 239 and 8160 for non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, 11 115 806 and 16 578 for non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders, 21 753 829 and 121 166 for non-Hispanic blacks, 106 675 849 and 462 495 for non-Hispanic whites, and 28 469 499 and 63 807 for Hispanics. Data were lacking to stratify mortality by educational attainment or other socioeconomic variables.

We examined geographic patterns using the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural classification scheme,34 which recognizes four metropolitan categories (large central metro, metropolitan statistical areas of ≥1 million population containing the largest principal city; large fringe metro, metropolitan statistical areas of ≥1 million population that do not qualify as large central metro counties; medium metro, metropolitan statistical areas with populations of 250 000-999 999; and small metro, metropolitan statistical areas with populations of <250 000) and two non-metropolitan categories (micropolitan statistical areas34 and non-core counties that do not qualify as micropolitan).

Public involvement

Engagement with community groups with large representation by African Americans raised awareness about potential inattention—within the scientific community and the news media—to increasing mortality rates among populations of color. Stakeholders with interests in minority health will help disseminate the results of this study.

Results

Among the 20 broad categories that contributed to all cause mortality, mortality rates in midlife (ages 25-64 years) increased in 13 categories during the 1999-2016 study period. Four categories had unreliable data (owing to small death counts): diseases of the eye and adnexa, diseases of the ear and mastoid process, perinatal conditions, and codes for special purposes. Midlife mortality rates decreased in the remaining three categories—infectious and parasitic diseases, neoplasms, and diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue.

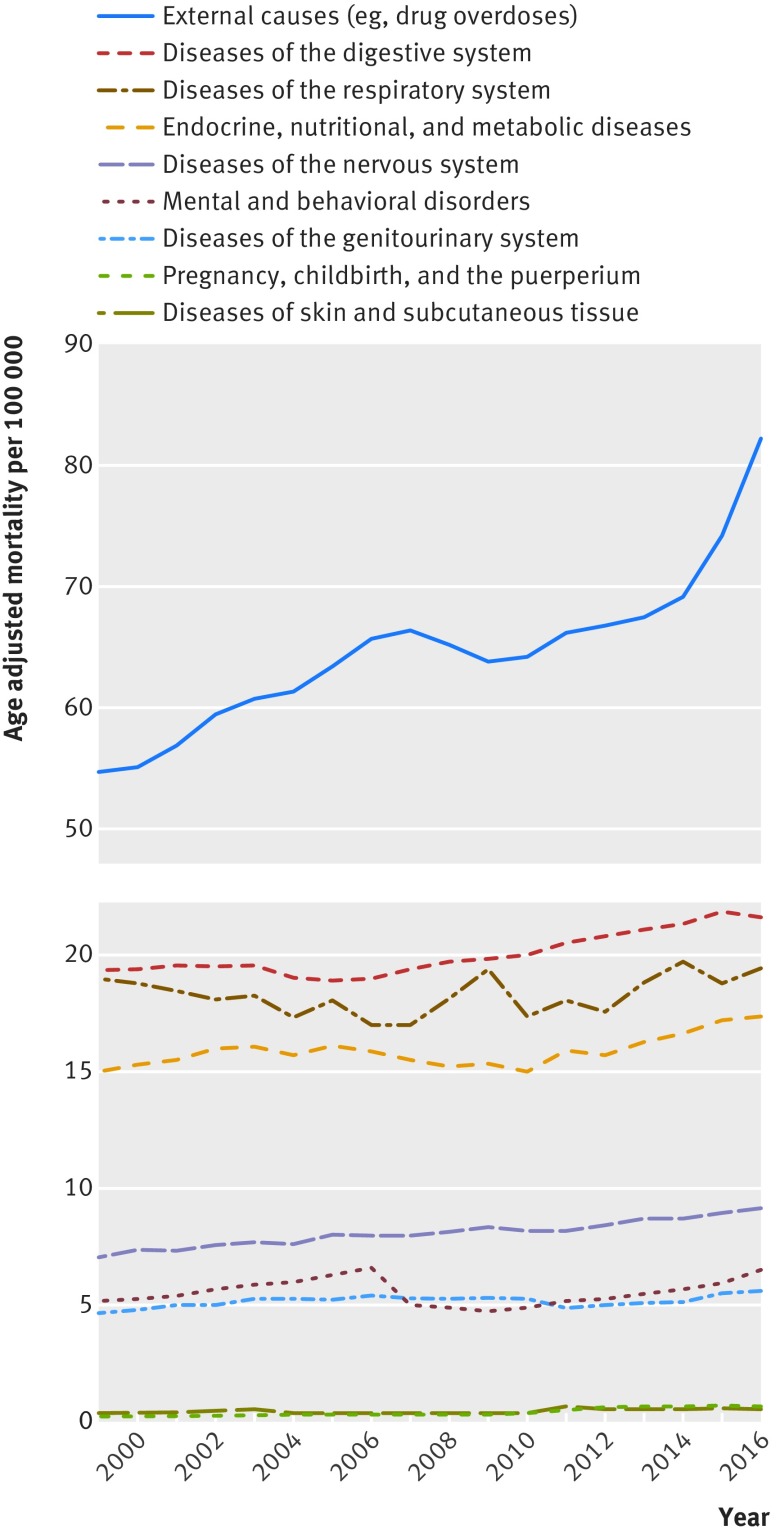

Of the 13 broad categories with increased midlife mortality rates, the largest proportional increases involved deaths from external causes, such as overdoses and transport incidents (fig 1). However, midlife mortality rates also increased for digestive diseases, such as alcohol related liver disease; respiratory diseases, such as chronic lower respiratory tract disease; endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases, such as diabetes and obesity; diseases of the nervous system, such as dementia; mental and behavioral disorders; genitourinary diseases, such as renal failure; diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue; and pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium. Mortality rates in three additional categories were stable or decreased over a period of years, reached a nadir, and then experienced a statistically significant increase: these included circulatory diseases, such as hypertensive disease; congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities; and symptoms, signs, and abnormal findings. Mortality from diseases of the blood and immune mechanism increased among non-Hispanic whites only.

Fig 1.

Cause specific mortality rates among US adults aged 25-64 years (midlife), 1999-2016, for 9/13 categories with increased midlife mortality rates. All cause mortality was classified into 20 broad categories (see text). 13 categories experienced an increase in midlife (25-64 years) mortality rates between 1999 and 2016, nine of which are shown here. Mortality rates for three additional categories were stable, or decreased over a period of years, but then increased significantly after reaching a nadir: these included circulatory diseases; congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities; and symptoms, signs, and abnormal findings, not elsewhere classified. Mortality from diseases of the blood and immune mechanism increased among non-Hispanic whites only

Midlife mortality trends by race and ethnicity

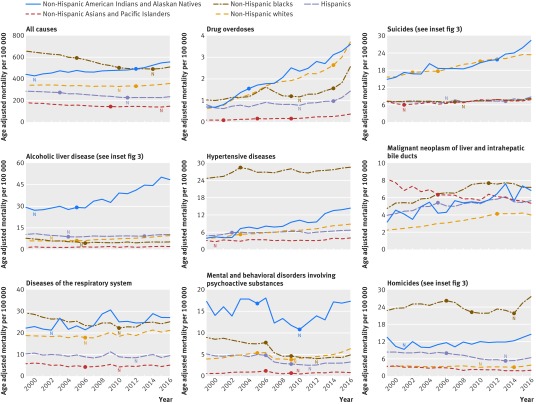

Between 1999 and 2016, midlife all cause mortality increased by 5.2% (AAPC 0.2%, 95% confidence interval 0.1% to 0.4%) among non-Hispanic whites, but the relative increase was much greater (26.6%; AAPC 1.5%, 1.0% to 1.9%) among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives (fig 2). All cause mortality rates exhibited retrogression, declining until 2009 among non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders, 2010 among non-Hispanic blacks, 2011 among Hispanics, and 2012 among non-Hispanic whites, but then plateauing or increasing. The progress these populations had achieved by reducing midlife mortality from certain diseases (eg, ischemic heart disease, cancer, HIV infection) was offset by statistically significant increases in mortality from external causes—notably drug overdoses, alcohol poisoning, and suicides—but also from a variety of organ diseases.

Fig 2.

Age adjusted all cause and cause specific mortality rates in US adults aged 25-64 years (midlife), 1999-2016, by race-ethnicity. Nadir (N) represents mortality rate that was statistically significantly below that of 2016. Solid circles denote joinpoints—points of inflection when mortality trend lines (not shown) changed significantly (P<0.05). See supplemental file for trend lines and larger renditions of each graph

Tables 1-4 show mortality rates stratified by race and ethnicity. Table 1 presents mortality rates for broad categories of causes of death, such as diseases of the digestive system (see supplemental figures S1-S16 for trends in 16/20 broad categories). Tables 2 and 3 provide data for specific conditions within the broad categories that were leading contributors to increasing midlife mortality among non-Hispanic whites (table 2) and populations of color (table 3); figure 2 shows the trends over time. The online supplement provides more details, including full size renditions of each panel in figure 2 (figs S17-S25), color coded versions of tables 1-3 that help visualize trends (tables S1-S3), tables that present mortality trends across racial-ethnic groups (tables S4-S7), joinpoint regression results for determining the statistical significance of changing trends (table S8), and a joinpoint chartbook with 241 graphs that plot trend lines, calculated by the regression model, for each cause of death and racial-ethnic group.

Table 1.

Mortality rates from all causes, external causes, and organ diseases in US adults aged 25-64 years (midlife), 1999-2016, by race-ethnicity (see supplemental file for detailed table, including ICD-10 codes for causes of death, data for intervening years 2000-15, nadirs, and fitted models)

| Racial-ethnic groups | Age adjusted mortality rates (deaths/100 000), by year | Changes in mortality rates | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average absolute year-to-year changes (per 100 000)† | Proportional (%) changes | ||||||||||

| 1999 | 2016 | 1999-2016 | 2012-16 | 2016 v 1999 | 2016 v nadir¶ | Fitted model‡ | |||||

| AAPC (1999-2016) | Final APC (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| All cause mortality | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 439.8 | 556.8 | 6.88 | 14.82 | 26.6* | 30.8* | 1.5* | 3.4 (1.5 to 5.4)§ | |||

| NH API | 177.6 | 145.6 | −1.88 | 0.56 | −18.0* | 4.5* | −1.3* | 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.8)§ | |||

| NH blacks | 656.1 | 509.8 | −8.61 | 2.74 | −22.3* | 4.0* | −1.5* | 2.1 (−0.6 to 4.9) | |||

| NH whites | 338.9 | 356.6 | 1.04 | 4.78 | 5.2* | 8.7* | 0.2* | 1.9 (1.2 to 2.6)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 284.3 | 234.8 | −2.91 | 2.05 | −17.4* | 4.6* | −1.2* | 0.6 (−0.2 to 1.3)§ | |||

| External causes | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 99.8 | 157.2 | 3.38 | 6.32 | 57.5* | 66.5* | 2.5* | 2.5 (2.1 to 3.0)(NJP) | |||

| NH API | 23.6 | 22.0 | −0.09 | 0.30 | −6.8 | 13.4* | −0.5 | 0.7 (−0.5 to 1.9)§ | |||

| NH blacks | 76.6 | 94.1 | 1.03 | 4.84 | 22.8* | 38.4* | 1.3* | 12.5 (7.4 to 17.8)§ | |||

| NH whites | 52.8 | 93.6 | 2.40 | 3.82 | 77.3* | NA | 3.5* | 9.6 (4.9 to 14.6)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 47.6 | 51.4 | 0.22 | 2.03 | 7.9* | 26.5* | 0.4 | 10.0 (4.7 to 15.6)§ | |||

| Organ diseases | |||||||||||

| Diseases of the circulatory system | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 91.7 | 97.7 | 0.35 | 1.51 | 6.5 | 12.0* | 0.4 | 3.3 (−0.3 to 7.0)§ | |||

| NH API | 52.3 | 35.7 | −0.97 | −0.03 | −31.7* | NA | −2.1* | −0.2 (−1.1 to 0.6)§ | |||

| NH blacks | 202.1 | 147.3 | −3.22 | 0.40 | −27.1* | NA | −1.9* | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.6)§ | |||

| NH whites | 91.0 | 75.6 | −0.91 | 0.41 | −17.0* | 3.2* | −1.1* | 0.6 (0.2 to 0.9)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 70.6 | 49.3 | −1.25 | −0.01 | −30.1* | NA | −2.1* | 0.4 (−1.1 to 1.8)§ | |||

| Diseases of the digestive system | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 55.6 | 79.0 | 1.38 | 2.54 | 42.1* | 49.1* | 2.3* | 3.4 (2.5 to 4.2)§ | |||

| NH API | 5.5 | 5.7 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 2.9 | NA | −0.3 | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.1)(NJP) | |||

| NH blacks | 28.6 | 19.6 | −0.53 | −0.24 | −31.4* | NA | −2.4* | −1.1 (−1.8 to −0.3)§ | |||

| NH whites | 17.6 | 22.6 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 28.8* | NA | 1.6* | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.3) | |||

| Hispanics | 24.9 | 21.6 | −0.20 | −0.06 | −13.5* | NA | −0.8* | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.3)§ | |||

| Diseases of the respiratory system | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 22.2 | 27.1 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 22.0 | 27.8* | 1.4* | 1.4 (0.5 to 2.3)(NJP) | |||

| NH API | 5.8 | 5.1 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −11.7 | 21.5* | −1.1 | 1.1 (−0.8 to 2.9)§ | |||

| NH blacks | 29.1 | 25.2 | −0.23 | 0.47 | −13.5 | 13.1* | −0.7* | 1.8 (0.0 to 3.7)§ | |||

| NH whites | 18.7 | 21.1 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 12.9* | 19.3* | 0.7* | 1.6 (0.8 to 2.5)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 10.4 | 9.5 | −0.05 | 0.17 | −8.5 | 10.9* | −0.7 | −0.7 (−1.4 to 0.1)(NJP) | |||

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 31.9 | 39.4 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 23.5* | 46.3* | 1.5* | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.3)(NJP) | |||

| NH API | 6.0 | 6.8 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 15.1 | NA | 0.4 | 0.4 (0.0 to 0.7)(NJP) | |||

| NH blacks | 33.3 | 32.2 | −0.07 | 0.50 | −3.5 | 12.9 | −0.2 | 2.0 (1.1 to 2.9) | |||

| NH whites | 12.7 | 16.1 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 26.4* | NA | 1.4* | 2.5 (1.8 to 3.3)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 16.2 | 14.4 | −0.11 | 0.23 | −11.3* | 8.9* | −1.0* | 1.5 (−0.7 to 3.8)§ | |||

| Diseases of the nervous system | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 5.5 | 10.9 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 99.8* | 19.5* | 3.7* | 3.7 (2.7 to 4.8)(NJP) | |||

| NH API | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 27.6 | 47.5 | 1.7* | 1.7 (0.9 to 2.6)(NJP) | |||

| NH blacks | 10.2 | 12.2 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 20.4* | NA | 1.0* | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.2)(NJP) | |||

| NH whites | 7.1 | 9.8 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 38.9* | NA | 1.6* | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8)(NJP) | |||

| Hispanics | 3.7 | 5.2 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 40.4* | NA | 1.4* | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.8)(NJP) | |||

| Mental and behavioral disorders | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 17.7 | 17.7 | 0.00 | 0.92 | -0.1 | 51.8* | 0.9 | 7.2 (3.2 to 11.2) | |||

| NH API | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 68.8 | NA | 2.3 | -0.6 (-2.8 to 1.7) | |||

| NH blacks | 9.8 | 6.5 | −0.19 | 0.15 | −33.6* | 14.5* | −2.6* | 1.7 (0.5 to 3.0)§ | |||

| NH whites | 4.6 | 7.4 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 61.1* | 51.0* | 2.7* | 5.7 (4.2 to 7.3)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 5.5 | 3.9 | −0.09 | 0.14 | −29.1* | 22.0* | −1.8 | 3.2 (0.9 to 5.4)§ | |||

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 8.1 | 10.4 | 0.14 | 0.62 | 29.0* | 42.5* | 0.4 | 0.4 (−0.7 to 1.5)(NJP) | |||

| NH API | 2.4 | 2.3 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −7.9 | NA | −0.7 | −0.7 (−1.4 to 0.0)(NJP) | |||

| NH blacks | 14.7 | 13.8 | −0.05 | 0.18 | −6.1 | 8.1 | −0.4 | 5.3 (−1.5 to 12.5)§ | |||

| NH whites | 3.4 | 4.6 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 35.7* | 18.9* | 1.8* | 5.6 (2.0 to 9.3)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 4.7 | 4.7 | 0.00 | 0.10 | −0.8 | NA | 0.2 | 4.5 (−1.3 to 10.7)§ | |||

| Pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | |||||||||||

| NH AIAN | UR | UR | NA | NA | NA | NA | Insufficient data | ||||

| NH API | UR | 0.4 | NA | 0.06 | NA | NA | Insufficient data | ||||

| NH blacks | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 167.9* | NA | 6.4* | 6.4 (5.6 to 7.3)(NJP) | |||

| NH whites | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 411.0* | NA | 12.2* | 7.5 (4.2 to 10.9)§ | |||

| Hispanics | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 101.5* | 106.3* | 3.3* | 3.3 (2.1 to 4.6)(NJP) | |||

APC=annual percentage change (slope for intervals between joinpoints); AAPC=average annual percentage change (slope for entire (1999-2016) period based on weighted average of APCs); NH=non-Hispanic; AIAN=American Indians and Alaskan Natives; API=Asians and Pacific Islanders; NA=not applicable (data inadequate for calculation); NJP=no joinpoint (fitted slope had no significant inflection during 1999-2016, values represent AAPC for 1999-2016); UR=unreliable data (<20 deaths from specified cause of death in given year and racial-ethnic group).

P <0.05.

Average year-to-year changes (from 1999 to 2016) in absolute mortality rates (deaths/100 000).

Percent increase in mortality rate relative to intervening year between 1999 and 2016 when the mortality rate reached its lowest value, which was statistically significantly below the 2016 mortality rate. Nadir years and year-by-year mortality rates are provided in table S1 of the supplemental file.

Slopes from fitted model, in which joinpoint analysis30 was used to plot trend lines that best fit the 17 annual mortality rates between 1999 and 2016. Joinpoints (see full table in the supplemental file) are points of inflection when mortality trend lines experienced a statistically significant change. For brevity, table presents APC values only for final interval ending in 2016 (or for 1999-2016 when no joinpoints were identified). (Supplemental file S1 provides the joinpoint years for each cause of death. See table S8 for all AAPC values, APC values for every segment, related 95% confidence intervals and P values, and joinpoint chartbook showing fitted model for each cause of death and racial-ethnic group.)

APC (slope) for interval ending in 2016 differed significantly (P<0.05) from slope of preceding period.

Table 2.

Mortality rates by leading causes of death in non-Hispanic whites aged 25-64 years (midlife), 1999-2016 (see supplemental file for detailed table, including ICD-10 codes for causes of death, data for intervening years 2000-15, nadirs, and fitted models)

| Causes of death | Age adjusted mortality rates (deaths/100 000), by year | Changes in mortality rates | Excess deaths (1999-2016) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average absolute year-to-year changes (per 100 000)† | Proportional (%) changes | |||||||||||

| 1999 | 2016 | 1999-2016 | 2012-16 | 2016 v 1999 | 2016 v nadir¶ | Fitted model‡ | ||||||

| AAPC (1999-2016) | Final APC (95% CI) | |||||||||||

| External causes | ||||||||||||

| Drug overdoses | 6.2 | 37.0 | 1.81 | 2.91 | 494.3* | NA | 11.1* | 20.0 (6.2 to 35.7)§ | 33 003 | |||

| Alcohol poisoning | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 674.5* | NA | 12.3* | 2.1 (−0.5 to 4.9)§ | 1146 | |||

| Pedestrian/cyclist/motorcycle injury | 3.4 | 5.1 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 50.1* | NA | 2.4* | 9.4 (−1.4 to 21.5) | 1404 | |||

| Miscellaneous land/other transport accidentsa | 6.7 | 7.2 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 7.8* | 23.5* | 0.2 | 2.8 (1.5 to 4.0) | 561 | |||

| Other forms of accidental poisoningb | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 139.1* | NA | 5.1* | 5.1 (4.2 to 6.0)(NJP) | 410 | |||

| Falls, drowning, firec | 3.7 | 4.4 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 19.4* | NA | 1.0* | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.6)§ | 768 | |||

| Suicide | 15.6 | 23.3 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 49.4* | NA | 2.5* | 1.8 (1.0 to 2.5)§ | 8300 | |||

| Diseases of the circulatory system | ||||||||||||

| Hypertensive diseases | 3.8 | 8.8 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 129.8* | NA | 5.1* | 4.2 (3.9 to 4.6)§ | 5318 | |||

| Other heart diseased | 14.2 | 15.0 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 6.0* | 15.6* | 0.4* | 2.9 (2.1 to 3.8)§ | 916 | |||

| Venous/lymphatic diseases | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 51.5* | NA | 1.3* | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.0)(NJP) | 376 | |||

| Pulmonary heart disease | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 3.6 | 19.7* | 0.0 | 1.7 (0.8 to 2.5)§ | 93 | |||

| Diseases of the digestive system | ||||||||||||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 5.8 | 9.4 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 62.4* | 63.0* | 2.9* | 4.1 (3.7 to 4.5)§ | 3901 | |||

| Mental and behavioral disorders | ||||||||||||

| Mental/behavioral disorders involving psychoactive substances | 4.0 | 6.3 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 58.9* | 66.7* | 2.6* | 7.4 (5.3 to 9.5)§ | 2493 | |||

| Organic mental disorders | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 185.9* | NA | 6.1* | −8.9 (−17.3 to 0.4)§ | 442 | |||

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | ||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous infectious diseasese | 3.7 | 5.7 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 53.9* | NA | 2.4* | 2.4 (2.2 to 2.7)(NJP) | 2149 | |||

| Neoplasms | ||||||||||||

| Liver cancer | 2.2 | 4.0 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 80.0* | NA | 3.7* | 0.0 (−1.3 to 1.3)§ | 1931 | |||

| Cancer of lip/oral cavity/pharynx | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 10.5* | 23.5* | 0.4 | 1.8 (0.6 to 3.0)§ | 215 | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | 5.3 | 5.5 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 3.3 | 7.6* | 0.3* | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5)(NJP) | 188 | |||

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | ||||||||||||

| Obesity | 1.2 | 2.7 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 124.6* | NA | 4.9* | 3.3 (2.9 to 3.7)§ | 1616 | |||

| Diabetes | 9.3 | 10.1 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 8.9* | 14.2* | 0.5* | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.0)§ | 879 | |||

| Metabolic disorders | 1.7 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 46.2* | NA | 2.0* | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.3)(NJP) | 858 | |||

| Miscellaneous endocrine disordersf | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 31.1* | 38.9* | 1.7* | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.2)(NJP) | 154 | |||

| Diseases of the respiratory system | ||||||||||||

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 11.5 | 12.3 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 6.6* | 17.1* | 0.5* | 1.4 (0.9 to 1.9)§ | 835 | |||

| Lung diseases due to external agents | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 60.3* | NA | 2.4* | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.8)(NJP) | 542 | |||

| Miscellaneous respiratory system disordersg | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 206.5* | 252.1* | 6.3* | 37.4 (20.1 to 57.1)§ | 1709 | |||

| Diseases of the nervous system | ||||||||||||

| Alzheimer’s/degenerative disorders | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 76.8* | 84.5* | 2.8* | 2.8 (2.1 to 3.4)(NJP) | 498 | |||

| Epilepsy/episodic, paroxysmal disorders | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 60.6* | NA | 2.4* | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.9)(NJP) | 401 | |||

| Inflammatory diseasesh | 1.9 | 2.3 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 17.1* | NA | 0.8* | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1)(NJP) | 353 | |||

| Cerebral palsy | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 59.1* | 15.3* | 3.2* | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.1)§ | 346 | |||

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 65.6* | NA | 2.0* | 2.0 (1.3 to 2.7)(NJP) | 189 | |||

| Miscellaneous peripheral diseasesi | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 29.9* | 34.0* | 1.0* | 1.0 (0.4 to 1.6)(NJP) | 177 | |||

| Miscellaneous disordersj | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 78.5* | NA | 3.5* | 3.3 (2.5 to 4.1) | 1084 | |||

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | ||||||||||||

| Renal failure | 2.4 | 3.2 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 33.7* | 13.5* | 1.6* | 5.3 (−2.9 to 14.2) | 865 | |||

| Other urinary system diseasesk | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 43.3* | 31.6* | 1.8* | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.4)(NJP) | 385 | |||

APC=annual percentage change (slope for intervals between joinpoints); AAPC=average annual percentage change (slope for entire (1999-2016) period based on weighted average of APCs); NA=not applicable (data inadequate for calculation); NJP=no joinpoint (fitted slope had no significant inflection during 1999-2016, values represent AAPC for 1999-2016). a=Accidents involving other land, water transport, air/space, and other/unspecified transport; b=accidental poisoning by organic solvents, halogenated hydrocarbons, other gases and vapors, pesticides, and unspecified chemicals and noxious substances; c=includes deaths from submersion, smoke, and flames; d=arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, cardiac arrest, myocarditis, and valvular and pericardial disease; e=intestinal infections, tuberculosis, and zoonotic and other bacterial, sexually transmitted, spirochetal, chlamydial, rickettsial, central nervous system, arthropod-borne, and viral hemorrhagic infections; f=disorders of thyroid and other endocrine glands, malnutrition, and disorders of glucose regulation and pancreatic internal secretion; g=respiratory failure, not elsewhere classified, and other respiratory disorders; h=inflammatory diseases (eg, meningitis, encephalitis) and systemic atrophies (eg, Huntington’s disease) affecting the central nervous system; i=nerve/nerve root/plexus disorders, polyneuropathies, and other disorders of the peripheral nervous system, diseases of myoneural junction and muscle; j=disorders of autonomic nervous system, hydrocephalus, toxic encephalopathy, and other disorders of nervous system, not elsewhere classified; k=glomerular and renotubular interstitial diseases, urolithiasis, and other diseases of urinary system. See supplemental file for ICD-10 codes for each cause of death.

P <0.05.

Average year-to-year changes (1999-2016) in absolute mortality rates (deaths/100 000).

Percent increase in mortality rate relative to intervening year between 1999 and 2016 when the mortality rate reached its lowest value, which was statistically significantly below the 2016 mortality rate. Nadir years and year-by-year mortality rates are provided in table S2 of the supplemental file.

Slopes from fitted model, in which joinpoint analysis30 was used to plot trend lines that best fit the 17 annual mortality rates between 1999 and 2016. Joinpoints (JP) are points of inflection when mortality trend lines experienced a statistically significant change. For brevity, table presents APC values only for final interval ending in 2016 (or for 1999-2016 when no joinpoints were identified). (Supplemental file S2 provides the joinpoint years for each cause of death. See table S8 for all AAPC values, APC values for every segment, related 95% confidence intervals and P values, and joinpoint chartbook showing fitted model for each cause of death and racial-ethnic group.)

APC (slope) for interval ending in 2016 differed significantly (P<0.05) from slope of preceding period.

Table 3.

Mortality rates among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, blacks, Hispanics, and Asians and Pacific Islanders, aged 25-64 years (midlife), 1999-2016, by leading causes of death (see supplemental file for detailed table, including ICD-10 codes for causes of death, data for intervening years 2000-15, nadirs, and fitted models)

| Causes of death | Age adjusted mortality rates (deaths/100 000), by year | Average absolute year-to-year changes (per 100 000)† | Proportional (%) changes | Excess deaths (1999-2016) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2016 | 1999-2016 | 2012-16 | 2016 v 1999 | 2016 v nadir¶ | Fitted model‡ | ||||||

| AAPC (1999-2016) | Final APC (95% CI) | |||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives | ||||||||||||

| Drug overdoses | 7.0 | 35.9 | 1.70 | 2.22 | 411.4* | NA | 10.9* | 7.1 (5.7 to 8.5)§ | 370 | |||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 29.3 | 48.6 | 1.14 | 1.96 | 65.9* | 78.0* | 3.5* | 5.3 (4.3 to 6.3)§ | 254 | |||

| Suicide | 14.9 | 28.4 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 91.2* | NA | 3.5* | 6.6 (1.4 to 12.1) | 176 | |||

| Hypertensive diseases | 3.9 | 14.3 | 0.61 | 1.01 | 269.3* | NA | 7.8* | 7.8 (6.4 to 9.3)(NJP) | 134 | |||

| Other heart diseasea | 15.7 | 20.1 | 0.26 | 0.79 | 27.7 | 34.9* | 0.9* | 0.9 (0.2 to 1.6)(NJP) | 57 | |||

| Colorectal cancer | 6.7 | 10.8 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 60.6* | NA | 2.0* | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.0)(NJP) | 52 | |||

| Liver cancer | 3.2 | 6.8 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 115.1* | NA | 4.0* | 4.0 (2.7 to 5.2)(NJP) | 45 | |||

| Falls, drowning, fireb | 8.3 | 11.6 | 0.19 | 0.59 | 39.3 | 49.0* | 1.3 | 4.1 (1.3 to 6.9)§ | 43 | |||

| Viral hepatitis | 2.3 | 4.8 | 0.15 | −0.12 | 112.1* | NA | 3.7* | 3.7 (1.5 to 5.9)(NJP) | 29 | |||

| Diabetes | 28.6 | 30.9 | 0.13 | 0.66 | 7.9 | 37.7* | 0.9 | 3.7 (0.7 to 6.7)§ | 38 | |||

| Homicide | 13.5 | 14.5 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 7.6* | 55.3* | 1.2* | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.2)(NJP) | 19 | |||

| Mental/behavioral disorders involving psychoactive substances | 17.3 | 17.3 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.2 | 61.8* | 1.1 | 9.0 (2.6 to 15.8)§ | 6 | |||

| Miscellaneous nervous system disordersc | UR | 3.5 | NA | 0.05 | NA | 108.9* | Insufficient data | 24 | ||||

| Alcohol poisoning | 2.2 | 10.2 | NA | 0.21 | 366.6* | NA | Insufficient data | 104 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic blacks | ||||||||||||

| Drug overdoses | 10.2 | 25.5 | 0.90 | 2.51 | 149.6* | 119.1* | 5.8* | 28.7 (11.4 to 48.7)§ | 3187 | |||

| Homicide | 22.8 | 27.6 | 0.29 | 1.15 | 21.4* | 27.2* | 1.1 | 11.3 (3.8 to 19.3)§ | 1005 | |||

| Hypertensive diseases | 24.7 | 28.5 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 15.5* | NA | 0.7* | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.5)§ | 725 | |||

| Obesity | 2.3 | 5.1 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 120.7* | NA | 4.8* | 9.6 (1.4 to 18.4) | 545 | |||

| Liver cancer | 4.8 | 7.2 | 0.14 | −0.10 | 49.5* | NA | 2.2* | −1.8 (−3.6 to 0.0)§ | 430 | |||

| Miscellaneous nervous system disordersc | 3.7 | 5.1 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 35.8* | NA | 2.2* | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.5)(NJP) | 268 | |||

| Pedestrian/cyclist/motorcycle injury | 5.4 | 6.6 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 23.7* | 36.5* | 1.2 | 5.1 (3.4 to 6.8)§ | 265 | |||

| Miscellaneous land/other transport accidentsd | 6.4 | 7.5 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 17.7* | 42.8* | 1.1 | 6.5 (2.6 to 10.5)§ | 264 | |||

| Metabolic disorders | 2.4 | 3.5 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 43.2* | 47.2* | 2.0* | 4.6 (2.8 to 6.5)§ | 216 | |||

| Miscellaneous respiratory system disorderse | 1.3 | 2.4 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 75.8* | 87.3* | 3.5* | 8.7 (2.8 to 14.9)§ | 212 | |||

| Suicide | 7.2 | 8.2 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 13.7* | 17.7* | 0.6* | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.0)§ | 213 | |||

| Organic mental disorders | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 215.3* | NA | 6.2* | −10.5 (−31.5 to 17.1) | 119 | |||

| Cerebral palsy | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 93.4* | NA | 3.5* | 1.3 (0.4 to 2.1) | 109 | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease/degenerative disorders | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 54.1 | 64.9* | 2.5* | 2.5 (1.2 to 3.8)(NJP) | 42 | |||

| Lung diseases due to external agents | 1.6 | 1.6 | −0.00 | 0.05 | −1.1 | 30.1* | 0.1 | 3.1 (0.8 to 5.4)§ | 4 | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | 8.1 | 7.8 | −0.01 | 0.15 | −3.1 | 10.6* | −0.2 | 1.6 (0.3 to 2.9)§ | (29) | |||

| Miscellaneous infectious diseasesf | 12.2 | 11.5 | −0.04 | 0.12 | −5.8 | 8.9* | −0.6 | 2.1 (0.0 to 4.3)§ | (134) | |||

| Pulmonary heart disease | 6.3 | 5.5 | −0.05 | 0.09 | −12.3 | 17.9* | −0.8* | 1.5 (0.2 to 2.7)§ | (126) | |||

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 13.7 | 11.7 | −0.12 | 0.17 | −14.66* | 9.5* | −1.0* | 0.7 (0.0 to 1.3)§ | (339) | |||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 7.7 | 5.2 | −0.14 | 0.04 | −31.59* | 20.4* | −2.3* | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.1)§ | (418) | |||

| Car accidents | 6.2 | 3.2 | −0.18 | −0.03 | −48.52* | 25.5* | −4.2* | 6.9 (−4.0 to 19.0)§ | (574) | |||

| Mental/behavioral disorders involving psychoactive substances | 9.0 | 4.9 | −0.24 | 0.13 | −45.13* | 23.3* | −3.9* | 1.4 (−0.3 to 3.2)§ | (749) | |||

| Diabetes | 27.1 | 22.4 | −0.28 | 0.10 | −17.29* | 7.0* | −1.1 | 1.0 (0.0 to 2.0) | (852) | |||

| Other heart disease | 37.7 | 32.2 | −0.32 | 0.78 | −14.53* | 13.8* | −0.9* | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.2)§ | (948) | |||

| Hispanics | ||||||||||||

| Drug overdoses | 7.9 | 14.3 | 0.37 | 1.11 | 80.0* | 83.3* | 4.3* | 22.4 (−4.8 to 57.3) | 1,777 | |||

| Hypertensive diseases | 4.7 | 6.6 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 40.6* | NA | 1.9* | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.3)§ | 410 | |||

| Liver cancer | 4.0 | 5.6 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 41.8* | NA | 2.2* | 0.9 (0.1 to 1.8)§ | 333 | |||

| Suicide | 7.1 | 8.6 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 21.9* | 28.9* | 1.2* | 5.3 (−0.3 to 11.2) | 426 | |||

| Alcohol poisoning | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 354.0* | 657.7* | 10.5* | 0.8 (−4.7 to 6.6)§ | 224 | |||

| Obesity | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 106.6* | NA | 3.8* | 3.8 (3.1 to 4.6)(NJP) | 193 | |||

| Metabolic disorders | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 60.0* | NA | 2.2* | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.0)(NJP) | 110 | |||

| Miscellaneous nervous system disordersc | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 42.0* | 47.6* | 2.5* | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.0)(NJP) | 99 | |||

| Pedestrian/cyclist/motorcycle injury | 4.6 | 4.9 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 7.5 | 30.7* | 0.1 | 2.7 (0.8 to 4.6) | 114 | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease/degenerative disorders | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 108.7* | NA | 3.2* | 3.2 (1.7 to 4.7)(NJP) | 62 | |||

| Epilepsy/episodic, paroxysmal disorders | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 78.4* | 46.5* | 1.5* | 1.5 (0.1 to 2.9)(NJP) | 56 | |||

| Organic mental disorders | 0.2 | 0.4 | NA | 0.01 | 113.9* | NA | Insufficient data | 42 | ||||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 10.4 | 10.4 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.6 | 20.3* | -0.2 | 4.0 (0.6 to 7.5) | 131 | |||

| Miscellaneous respiratory system disorderse | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 41.8 | 79.0* | 3.2* | 3.2 (1.7 to 4.8)(NJP) | 40 | |||

| Miscellaneous peripheral nervous system diseasesg | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 83.7* | NA | 2.0* | 2.0 (0.3 to 3.7)(NJP) | 39 | |||

| Miscellaneous land/other transport accidentsd | 5.4 | 5.1 | −0.02 | 0.34 | −5.5 | 49.1* | −0.4 | 8.8 (3.0 to 15.0)§ | 32 | |||

| Mental/behavioral disorders involving psychoactive substances | 5.1 | 3.3 | −0.11 | 0.15 | −35.4* | 28.8* | −2.5 | 3.4 (1.4 to 5.6)§ | (355) | |||

| Homicide | 8.4 | 6.4 | −0.12 | 0.16 | −23.5* | 22.0* | −1.6* | 7.0 (2.6 to 11.5)§ | (408) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders | ||||||||||||

| Drug overdoses | 0.9 | 3.6 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 300.6* | NA | 8.2* | 11.4 (8.9 to 14.0)§ | 258 | |||

| Hypertensive diseases | 3.1 | 4.0 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 28.3* | 51.9* | 1.2* | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.0)(NJP) | 93 | |||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 62.9* | NA | 2.0* | 2.0 (1.0 to 3.1)(NJP) | 68 | |||

| Brain/central nervous system cancers | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 56.6* | 36.5* | 1.4* | 1.4 (0.5 to 2.4)(NJP) | 61 | |||

| Mental/behavioral disorders involving psychoactive substances | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 39.2 | 73.1* | 2.7 | 8.2 (3.0 to 13.7) | 16 | |||

| Suicide | 7.2 | 7.8 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 7.4 | 29.7* | 0.7 | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.3) | 73 | |||

APC=annual percentage change (slope for intervals between joinpoints); AAPC=average annual percentage change (slope for entire (1999-2016) period based on weighted average of APCs); NA=not applicable (data inadequate for calculation); NJP=no joinpoint (fitted slope had no significant inflection during 1999-2016, values represent AAPC for 1999-2016): UR=unreliable data (<20 deaths from specified cause of death in given year and racial-ethnic group). a=Arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, cardiac arrest, myocarditis, and valvular and pericardial disease; b=includes deaths from submersion, smoke, and flames; c=disorders of autonomic nervous system, hydrocephalus, toxic encephalopathy, and other disorders of nervous system, not elsewhere classified; d=accidents involving other land, water transport, air/space, and other/unspecified transport; e=respiratory failure, not elsewhere classified, and other respiratory disorders; f=intestinal infections, tuberculosis, and zoonotic and other bacterial, sexually transmitted, spirochetal, chlamydial, rickettsial, central nervous system, arthropod borne, and viral hemorrhagic infections; g=nerve/nerve root/plexus disorders, polyneuropathies, and other disorders of the peripheral nervous system, diseases of myoneural junction and muscle.

P <0.05.

Average year-to-year changes (1999-2016) in absolute mortality rates (deaths/100 000).

Percent increase in mortality rate relative to intervening year between 1999 and 2016 when the mortality rate reached its lowest value, which was statistically significantly below the 2016 mortality rate. Nadir years and year-by-year mortality rates are provided in table S3 of the supplemental file.

Slopes from fitted model, in which joinpoint analysis30 was used to plot trend lines that best fit the 17 annual mortality rates between 1999 and 2016. Joinpoints (see full table in supplemental file) are points of inflection when mortality trend lines experienced a statistically significant change. For brevity, table presents APC values only for final interval ending in 2016 (or for 1999-2016 when no joinpoints were identified). (Supplemental file S3 provides the joinpoint years for each cause of death. See table S8 for all AAPC values, APC values for every segment, related 95% confidence intervals and P values, and joinpoint chartbook showing fitted model for each cause of death and racial-ethnic group.)

APC (slope) for interval ending in 2016 differed significantly (P<0.05) from slope of preceding period.

Table 4.

Changes in age adjusted mortality rates in US adults aged 25-64 years (midlife), by sex

| Variables | Age adjusted mortality rate (per 100 000) | Proportional (%) increase in mortality | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | 2016 v 1999 | 2016 v nadir | ||||||||||

| 1999 | Nadir rate (year) | 2016 | 1999 | Nadir rate (year) | 2016 | Women | Men | Women | Men | ||||

| All cause mortality | |||||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 340.0 | 321.6 (2000) | 418.3 | 546.2 | 536.6 (2000) | 705.1 | 23.0* | 29.1* | 30.0* | 31.4* | |||

| NH API | 138.0 | 102.0 (2014) | 108.1 | 222.1 | NA | 189.0 | −21.7* | −14.9* | 5.9* | NA | |||

| NH blacks | 487.6 | 375.9 (2012) | 386.4 | 856.3 | 617.3 (2004) | 650.0 | −20.7* | −24.1* | 2.8* | 5.3* | |||

| NH whites | 251.5 | 244.7 (2010) | 267.6 | 428.8 | 413.0 (2010) | 447.1 | 6.4* | 4.3* | 9.4* | 8.2* | |||

| Hispanics | 193.6 | 154.6 (2011) | 161.2 | 377.3 | 294.2 (2014) | 308.3 | −16.7* | −18.3* | 4.3* | 4.8* | |||

| External causes | |||||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 57.8 | 49.5 (2001) | 90.8 | 144.1 | 138.5 (2000) | 226.8 | 57.2* | 57.4* | 83.4* | 63.7* | |||

| NH API | 15.4 | 11.2 (2009) | 12.1 | 32.7 | 28.8 (2009) | 35.0 | −21.0* | 7.0 | 8.2 | 21.4* | |||

| NH blacks | 33.7 | 30.7 (2008) | 41.1 | 125.9 | 109.6 (2010) | 152.5 | 22.1* | 21.1* | 33.7* | 39.2* | |||

| NH whites | 27.7 | NA | 54.8 | 78.2 | NA | 132.2 | 98.3* | 69.1* | NA | NA | |||

| Hispanics | 18.5 | 17.1 (2008) | 21.8 | 75.6 | 62.8 (2010) | 79.9 | 17.9* | 5.6* | 27.8* | 27.3* | |||

| Drug overdoses | |||||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 5.1 | 4.6 (2000) | 28.3 | 9.0 | 8.9 (2000) | 43.9 | 457.0* | 386.8* | 509.5* | 395.8* | |||

| NH API | UR | 0.5 (2004) | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.3 (2000) | 5.8 | NA | 308.2* | 192.5* | 353.1* | |||

| NH blacks | 5.1 | NA | 15.5 | 16.1 | 15.2 (2010) | 36.7 | 201.7* | 127.8* | NA | 141.5* | |||

| NH whites | 3.4 | NA | 24.5 | 9.0 | NA | 49.3 | 611.5* | 445.9* | NA | NA | |||

| Hispanics | 2.6 | 2.3 (2000) | 6.7 | 13.2 | 9.9 (2001) | 21.6 | 158.9* | 64.2* | 194.0* | 118.8* | |||

| Alcohol induced causes | |||||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 31.2 | 27.8 (2000) | 53.7 | 65.7 | 57.6 (2000) | 99.4 | 72.0* | 51.3* | 93.2* | 72.7* | |||

| NH API | UR | 0.5 (2004) | 1.2 | 3.3 | NA | 5.1 | NA | 52.6* | 125.1* | NA | |||

| NH blacks | 7.1 | 4.4 (2007) | 5.8 | 23.6 | 12.8 (2012) | 14.3 | −18.8* | −39.3* | 31.7* | 11.6* | |||

| NH whites | 4.4 | NA | 9.7 | 14.6 | 14.5 (2000) | 21.4 | 120.3* | 46.5* | NA | 46.8* | |||

| Hispanics | 4.0 | 3.4 (2004) | 5.6 | 25.1 | 20.7 (2012) | 22.7 | 38.5* | −9.6* | 66.2* | 10.0* | |||

| Suicide | |||||||||||||

| NH AIAN | 7.0 | 5.0 (2003) | 12.5 | 23.1 | NA | 44.9 | 77.6* | 94.8* | 147.5* | NA | |||

| NH API | 3.8 | 3.2 (2000) | 4.1 | 11.1 | 8.9 (2001) | 11.9 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 27.3 | 33.9* | |||

| NH blacks | 2.2 | 2.0 (2006) | 3.1 | 13.0 | 12.1 (2007) | 13.7 | 40.5* | 5.7 | 56.0* | 13.5* | |||

| NH whites | 6.9 | NA | 11.7 | 24.4 | NA | 35.0 | 69.6* | 43.4* | NA | NA | |||

| Hispanics | 2.4 | 2.1 (2001) | 3.4 | 11.6 | 11.0 (2006) | 13.7 | 41.9* | 17.5* | 63.6* | 24.6* | |||

P<0.05.

NH=non-Hispanic; AIAN=American Indians and Alaskan Natives; API=Asians and Pacific Islanders; NA=not applicable (data unavailable), no nadir occurred; UR=unreliable data (<20 deaths from specified cause of death in given year and racial-ethnic group).

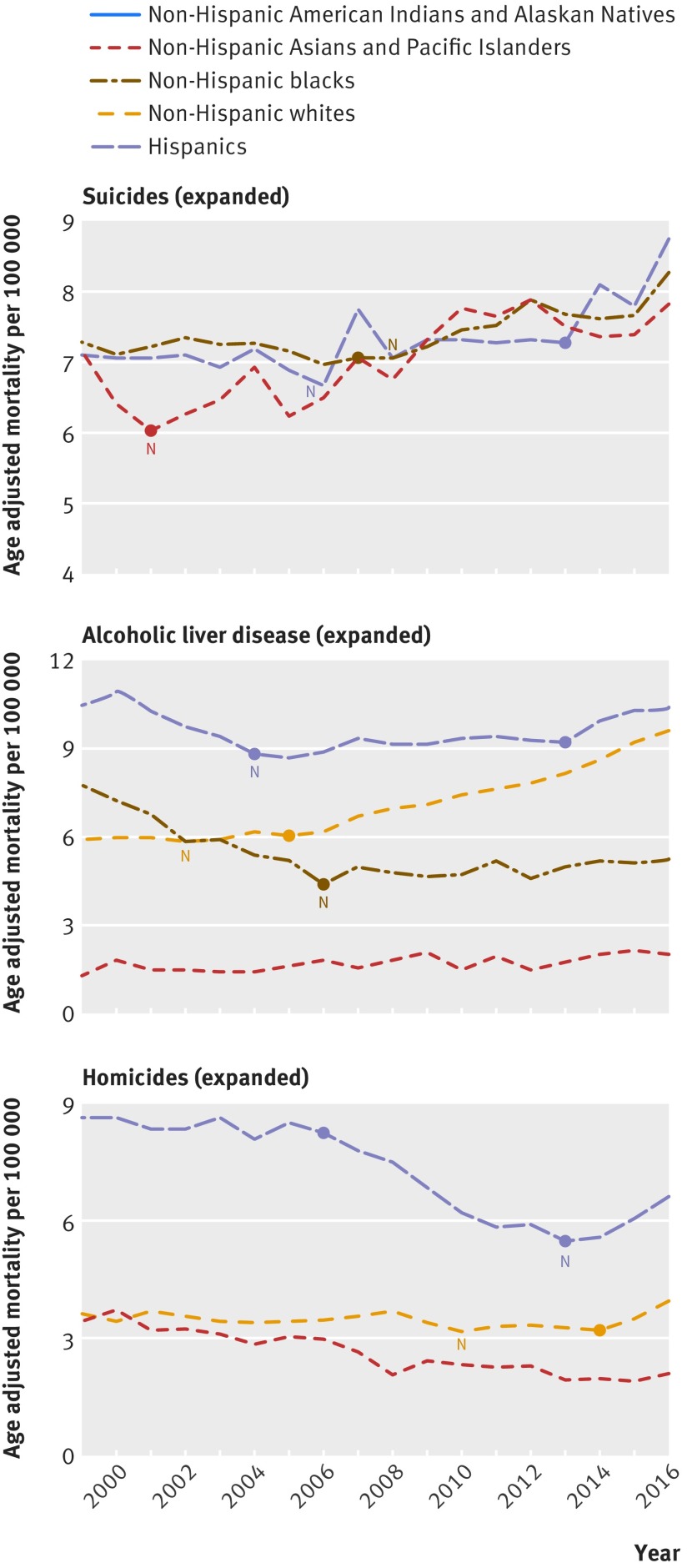

These data show that cause specific mortality rates increased across multiple racial and ethnic groups during 1999-2016. In many cases, such as deaths from external causes, non-Hispanic whites experienced the largest relative increases in midlife mortality rates, and, because of their population size, the largest absolute number of deaths. Mortality rates among non-Hispanic whites increased for many conditions (table 2), but the phenomenon was not restricted to non-Hispanic whites. Substantial increases in cause specific mortality rates occurred among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders (table 3). These mortality rates often exhibited retrogression—that is, declined for a period of years but then stabilized or experienced a statistically significant increase after reaching a nadir (fig 2 and insets in fig 3). In many cases, the absolute increase in cause specific mortality rates among people of color and Hispanics rivaled that of non-Hispanic whites, becoming more pronounced in recent years.

Fig 3.

Age adjusted mortality rates in US adults aged 25-64 years (midlife), 1999-2016, for suicide, alcohol related liver disease, and homicides by race-ethnicity. The figure replots selected data from figure 2 against a modified y axis to help visualize mortality trends among groups with lower baseline mortality rates. Nadir (N) represents mortality rate that was statistically significantly below that of 2016. Solid circles denote joinpoints—points of inflection when mortality trend lines (not shown) changed significantly (P<0.05). See supplemental file for trend lines and larger renditions of each graph

Non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives

Although the non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaskan Native population was much smaller than that of non-Hispanic whites, members of that population faced greater absolute risks of death and a larger relative increase in mortality from certain conditions. Table 3 presents the data for the leading contributors to increasing mortality, sequenced by the number of attributable deaths. The surge in mortality during 1999-2016 was driven by a 411.4% increase (AAPC 10.9%, 95% confidence interval 9.2% to 12.6%) in drug overdose deaths, which included large year-to-year increases during 2012-16, matched only by that of non-Hispanic whites. Non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives also experienced the largest proportional and year-to-year increases in mortality from alcohol related liver disease of any racial-ethnic group studied, with statistically significant increases after the last joinpoint. Proportional and year-to-year increases in suicides also exceeded those of other groups.

Between 1999 and 2016, non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives experienced large increases in death rates from hypertensive diseases (269.3%; AAPC 7.8%, 6.4% to 9.3%), liver cancer (115.1%; AAPC 4.0%, 2.7% to 5.2%), viral hepatitis (112.1%; AAPC 3.7%, 1.5% to 5.9%), and diseases of the nervous system (99.8%; AAPC 3.7%, 2.7% to 4.8%); the proportional and year-to-year increases during 2012-16 exceeded those of other groups. This was the only population in which cancer mortality increased (colorectal cancer mortality in particular). Mortality rates also increased for diabetes, a category of circulatory disorders that includes arrhythmias and heart failure, respiratory and genitourinary disorders, mental and behavioral disorders (notably those involving psychoactive substances), homicides, transport accidents, and a category of accidents that includes falls and drownings. The latter increased by 49.0% after 2008, at a faster year-to-year pace than occurred in other groups. In 2012-16, non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives averaged the largest relative increase in midlife mortality from diabetes.

Non-Hispanic blacks

Historically high mortality rates among non-Hispanic blacks decreased substantially between 1999 and 2016, but this two point comparison obscured a statistically significant change in slope that began in 2014, when the decline in all cause mortality ended (table 1). The rate of fatal drug overdoses, the leading cause of excess deaths, increased by 149.6% (AAPC 5.8%, 95% confidence interval 2.9% to 8.9%) between 1999 and 2016. Mortality from homicides increased by 27.2% after 2014 (post-2014 APC 11.3%, 95% confidence interval, 3.8% to 19.3%), producing a greater proportional and year-to-year increase than occurred in any other racial-ethnic group. Retrogression occurred with mortality from alcohol related liver disease, which increased by 20.4% after 2006 (post-2006 APC 1.2%, 0.3% to 2.1%); suicides, which increased by 17.7% after 2008 (post-2007 APC 1.5%, 0.9% to 2.0%); and deaths from mental and behavioral disorders, notably those involving psychoactive substances, the latter increasing by 23.3% after 2012. During 2012-16, midlife mortality from transport (eg, car, pedestrian, and motorcycle) accidents also increased among non-Hispanic blacks.

Additionally, non-Hispanic blacks experienced retrogression with a variety of organ diseases. After years of declining mortality, death rates increased for endocrine and metabolic disorders (eg, diabetes), certain circulatory disorders (eg, arrhythmias, heart failure) and infectious diseases, respiratory diseases (eg, chronic lower respiratory tract disease, lung diseases involving external agents (eg, pneumoconiosis)), and pancreatic cancer (table 3). Midlife mortality increased for hypertensive diseases, liver cancer, neurologic conditions (eg, cerebral palsy), and organic mental disorders (eg, vascular dementia). Obesity related mortality more than doubled (120.7% increase; AAPC 4.8%, 2.9% to 6.7%), producing higher year-to-year increases than in any other group, and the death rate from metabolic disorders also increased (AAPC 2.0%, 1.3% to 2.7%). The increase in mortality for certain conditions escalated during 2012-16; non-Hispanic blacks averaged the highest year-to-year increases in homicides, transport accidents, hypertensive diseases, and other circulatory, respiratory, endocrine, and nervous system diseases.

Hispanics

Although the Hispanic population generally exhibited lower absolute mortality rates than non-Hispanic whites—the so-called Hispanic paradox35 36—this population also experienced retrogression: all cause mortality decreased until 2011, after which the APC increased (table 1). The rate of fatal drug overdoses increased by 80.0% (AAPC 4.3%, 1.4% to 7.3%). Alcohol related deaths showed retrogression: statistically significant increases occurred in the rate of fatal alcohol poisoning (AAPC 10.5%, 1.2% to 20.6%), increasing by 657.7% after 2003, and midlife mortality from alcohol related liver disease increased by 20.3% after 2004 (post-2013 APC 4.0%, 0.6% to 7.5%). The midlife suicide rate increased during 1999-2016 (AAPC 1.2%, 0.2% to 2.1%), increasing by 28.9% after 2006. Mortality rates from mental and behavioral disorders involving psychoactive substances increased by 28.8% after 2011 (post-2009 APC 3.4%, 1.4% to 5.6%).

Hispanics also experienced an increase in midlife mortality from organ diseases, including hypertensive diseases (AAPC 1.9%, 0.9% to 2.9%), liver cancer (2.2%, 1.3% to 3.0%), obesity (3.8%, 3.1% to 4.6%), metabolic disorders (2.2%, 1.5% to 3.0%), and various neurologic and mental disorders (table 3). Homicide rates increased after 2013, and fatal pedestrian, motorcycle, and other transport accidents increased after 2011, by 2012-16 outpacing the year-to-year increases in mortality experienced by non-Hispanic whites.

Non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders

Non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders were least impacted by increasing mortality rates. Although this population had the lowest absolute mortality rates, they experienced statistically significant cause specific increases in midlife mortality during 1999-2016, notably from drug overdoses (300.6%; AAPC 8.2%, 5.1% to 11.5%) and alcohol related liver disease (62.9%; AAPC 2.0%, 1.0% to 3.1%). Suicide rates increased by 29.7% after 2001 (post-2001 APC 1.7%, 1.1% to 2.3%), and mortality from mental and behavioral disorders involving use of psychoactive substances increased by 73.1% after 2010 (post-2009 APC 8.2%, 3.0% to 13.7%).

Although non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders exhibited few statistically significant increases in mortality from organ diseases during 1999-2016, they did experience a significant increase in midlife mortality from brain and other central nervous system cancers (56.6%; AAPC 1.4%, 0.5% to 2.4%). The average increase in midlife mortality from neurologic diseases was also significant (AAPC 1.7%, 0.9% to 2.6%). Mortality from hypertensive diseases increased by 28.3%, and retrogression occurred with diseases of the respiratory system.

Midlife mortality trends by sex

Among non-Hispanic whites, the relative increase in midlife all cause mortality was greater among women than among men (6.4% v 4.3%), whereas the reverse occurred among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives (23.0% v 29.1%) (table 4). Post-nadir increases in all cause mortality among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were also higher among men than among women (5.3% v 2.8%, 4.8% v 4.3%, respectively). However, although men had higher absolute mortality rates for drug overdoses and suicides, the relative increase was higher among women. The relative increase in fatal drug overdoses was higher for women than for men among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives (457.0% v 386.8%), non-Hispanic blacks (201.7% v 127.8%), non-Hispanic whites (611.5% v 445.9%), and Hispanics (158.9% v 64.2%); data were lacking for non-Hispanic Asians and Pacific Islanders. The same pattern occurred with suicides among non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics; men experienced the larger relative increase among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives.

Midlife mortality trends by geography

Across all racial-ethnic groups, midlife all cause mortality rates were higher in non-metropolitan areas (eg, rural) than metropolitan areas. Among non-Hispanic whites, the relative increase in all cause mortality during 1999-2016 was greater in non-metropolitan areas, whereas the reverse occurred among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives (ie, larger relative increases in metropolitan areas). The same pattern was seen for suicides (table 5). With drug overdoses, the largest relative increases among non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics occurred in suburban areas of large cities (populations ≥1 million) designated as fringe areas,34 whereas the largest relative increases among non-Hispanic blacks occurred in small cities (populations <250 000).

Table 5.

Changes in age adjusted mortality rates in US adults aged 25-64 years (midlife), by geographic location.

| Variables | Proportional increase in mortality (%, deaths/100 000 (1999, 2016)) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro | Non-metro | |||||||

| Large central | Large fringe | Medium | Small | Micro | Non-core | |||

| All causes | ||||||||

| NH AIAN | 30.5 (361.4, 471.7)* | 22.4 (570.5, 698.5)* | ||||||

| 27,6 (346.4, 442.1)* | 17.2 (288.9, 338.7) | 25.4 (389.5, 488.6)* | 33.7 (416.2, 627.6)* | 31.2 (497.1, 652.2)* | 15.3 (649.0, 748.4)* | |||

| NH API | −17.6 (174.0, 143.3)* | −26.1 (301.4, 222.8)* | ||||||

| −17.2 (172.6, 143.0)* | −17.2 (141.6, 117.2)* | −15.7 (222.5, 187.5)* | −9.3 (175.7, 160.7) | −24.7 (307.7, 231.7)* | −27.5 (266.3, 193.0) | |||

| NH blacks | −22.9 (649.0, 500.7)* | −16.5 (715.4, 597.6)* | ||||||

| −24.5 (701.6, 535.5)* | −24.5 (528.6, 399.2)* | −17.0 (647.0, 536.8)* | −15.6 (647.4, 560.2)* | −15.6 (710.5, 599.3)* | −17.5 (721.3, 595.4)* | |||

| NH whites | 2.6 (331.3, 339.9)* | 16.9 (371.3, 434.2)* | ||||||

| 3.1 (345.5, 315.0)* | 3.1 (304.7, 314.1)* | 10.6 (340.0, 376.2)* | 10.8 (349.7, 391.9)* | 15.5 (366.3, 423.1)* | 18.9 (378.4, 449.9)* | |||

| Hispanics | −17.3 (280.2, 231.7)* | −17.5 (341.3, 281.7)* | ||||||

| −13.7 (289.4, 230.2)* | −13.7 (224.6, 193.7)* | −10.0 (295.9, 266.4)* | −13.2 (294.9, 260.5)* | −13.6 (328.3, 283.8)* | −24.6 (368.3, 27.6)* | |||

| Drug overdoses | ||||||||

| NH AIAN | 306.3 (8.9, 36.1)* | NA (UR, 35.6) | ||||||

| NH API | 337.5 (0.8, 3.5)* | NA (NA, 7.5) | ||||||

| NH blacks | 145.2 (10.9, 26.8)* | 198.2 (4.1, 12.2)* | ||||||

| 118.1 (15.7, 34.2)* | 240.5 (5.5, 18.9)* | 243.3 (6.6, 22.8)* | 312.5 (4.8, 19.8)* | |||||

| 217.6 (4.3, 13.8)* | 170.6 (3.7, 10.1)* | |||||||

| NH whites | 467.0 (6.7, 38.2)* | 683.0 (4.0, 31.2)* | ||||||

| 262.9 (10.3, 37.3)* | 754.2 (4.7, 40.3)* | 541.7 (6.3, 40.6)* | 643.9 (4.3, 31.6)* | 666.1 (4.2, 32.5)* | 685.0 (3.7, 29.2)* | |||

| Hispanics | 78.1 (8.1, 14.4)* | 104.7 (6.3, 12.9)* | ||||||

| 58.7 (9.0, 14.2)* | 361.3 (2.9, 13.5)* | 58.1 (10.2, 16.0)* | 89.9 (6.9, 13.1)* | 63.4 (8.2, 13.4)* | NA (UR, 12.0) | |||

| Suicide | ||||||||

| NH AIAN | 105.6 (12.1, 24.8)* | 75.9 (19.5, 34.4)* | ||||||

| NH API | 5.8 (7.1, 7.6) | NA (UR, 14.9) | ||||||

| NH blacks | 12.7 (7.3, 8.3)* | 18.4 (6.4, 7.6) | ||||||

| 3.5 (7.9, 8.2) | 25.2 (6.1, 7.7) | 29.6 (7.0, 9.0)* | 9.0 (8.4, 9.2) | 49.4 (6.0, 8.9) | −14.5 (7.0, 6.0) | |||

| NH whites | 46.3 (15.4, 22.5)* | 62.7 (16.8, 27.3)* | ||||||

| 29.4 (15.9, 20.5)* | 53.2 (13.6, 20.8)* | 57.0 (16.3, 25.6)* | 49.7 (17.1, 25.6)* | 61.8 (16.5, 26.7)* | 64.3 (17.2, 28.2)* | |||

| Hispanics | 23.7 (6.8, 8.3)* | 6.7 (11.8, 12.6) | ||||||

| 20.5 (6.5, 7.8)* | 41.6 (5.4, 7.6)* | 24.5 (7.5, 9.4) | 9.9 (11.2, 12.4) | 20.3 (10.2, 12.3) | −12.7 (15.1, 13.2) | |||

.*P<0.05.

NH=non-Hispanic; AIAN=American Indians and Alaskan Natives; API=Asians and Pacific Islanders; NA=not applicable (data unavailable), no nadir occurred; UR=unreliable data (<20 deaths from specified cause of death in given year, racial-ethnic group, and geographic setting);large central=metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) of ≥1 million population containing largest principal city; large fringe=MSAs of ≥1 million population that do not qualify as large central metro counties; medium=MSAs with populations of 250 000-999 999; small metro=MSAs with populations <250 000; micro=micropolitan statistical areas; non-core=counties that do not qualify as micropolitan.

Discussion

Life expectancy in the United States has not kept pace with progress in other industrialized nations and is now decreasing.37 This study, like others, reports that mortality rates have increased since the 1990s, but the problem has older roots. According to a 2013 report by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, the “US health disadvantage” began decades ago and has grown more pervasive with time.38 That report documented poor health in nine domains: birth outcomes, injuries and homicides, adolescent pregnancy, HIV/AIDS, drug related mortality, obesity and diabetes, heart disease, chronic lung disease, and disability. The report identified deep, systemic causes for the US health disadvantage involving not only deficiencies in healthcare and the prevalence of risky behaviors but also socioeconomic inequalities, unhealthy environmental conditions, and detrimental public policies.39

This study reaffirms the pervasiveness of the problem. Although drug overdoses accounted overwhelmingly for the excess deaths caused by increasing mortality rates, alcohol related diseases, suicides, unintentional injuries, and organ diseases involving multiple body systems together accounted for even more excess deaths. No single factor, such as opioids, explains this phenonemon.40 A more likely explanation is the systemic problems identified by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine,38 which require upstream solutions. The prediction issued in 2013—that conditions would worsen without bold policy action to tackle these root causes39—was followed by higher premature mortality. Tables 2 and 3 document many instances in which mortality rates in recent years experienced statistically significant increases, often eclipsing the slope (AAPC) for 1999-2016, suggesting that mortality in midlife is now increasing faster.

The work of Case and Deaton3 9 stimulated extensive media coverage. Stories typically featured white families—often in rust belt, Appalachian, or rural communities—struggling with opioid addiction.24 25 26 41 42 43 This study suggests that the problem also affects non-white populations and has broader health implications (beyond addiction) than media coverage would suggest. While mortality rates among non-Hispanic whites experienced large increases during 1999-2016, they also rose simultaneously (and sometimes more substantively) among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives. Moreover, our study refutes prior assertions that mortality rates have improved for non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics. This was once true, but current data now reveal a reversal in progress for many conditions: mortality rates that had been decreasing among populations of color reached a nadir, giving way to increasing death rates, often accelerating faster among non-white Americans than among whites. This is especially troubling given the historically high baseline mortality rates that exist among populations of color, notably non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives.2

Although mortality rates were higher among men than among women, the relative increase in fatal drug overdoses and suicides was greater among women, consistent with other reports of the worsening health disadvantage among women in the US.21 22 38 44 45 Others have studied geographic patterns in US mortality trends.4 9 21 46 47 48 49 Our study confirms reports11 of higher mortality rates and larger relative increases in mortality in rural areas, but it also documents statistically significant increases within metropolitan areas. Non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics experienced the largest proportional increases in drug overdose deaths in suburban fringe areas, whereas the largest increases among non-Hispanic blacks occurred in small cities. Non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives living in metropolitan areas experienced a larger relative increase in suicides than those in rural areas.

Limitations of this study

This study’s limitations deserve consideration. For example, comparisons of mortality rates for some racial groups are vulnerable to biases introduced by misclassification of race and undercounting.50 Funeral directors record race and Hispanic ethnicity based on descriptions from informants (eg, family members) or direct observation.51 Census data on race and ethnicity are based on self report. The data provided by CDC WONDER are unlinked and can therefore be influenced by numerator-denominator mismatching. For example, death rates can be biased by inconsistencies between vital statistics and census data in classifying race and Hispanic origin.52 Some of the large relative increases in mortality rates reported here involved uncommon causes of death. For example, the 242.0% increase in mortality from alcohol poisoning in non-Hispanic blacks reflected an absolute rate increase from 0.2 to 0.8 deaths per 100 000.

Although we tried to limit coding bias by restricting the analysis to the years (1999 and later) during which only ICD-10 coding was in effect, subtle changes in coding practices may still have influenced reported mortality rates. These influences could include new coding directives, changes in coding algorithms or software, and trends among professionals (eg, greater propensity to code Alzheimer’s disease as a cause of death). Changes in the proportion of decedents undergoing autopsy, the propensity of medical examiners to assign socially stigmatized causes of death (eg, suicide, substance misuse), and disparities in these trends by geography or decedent race-ethnicity could also influence results.

In addition, the analysis omitted data before 1999, information that could help contextualize trends; excluded people younger and older than 25-64 years; did not disaggregate results for age groups between ages 25 and 64 years or aggregate deaths over multiple years to enhance statistical power; and stratified mortality rates only by race-ethnicity and not by education, income, or other factors that influence mortality.53 54 55 It is therefore unclear, for example, whether mortality rate increases differ as substantially by race-ethnicity among adults with a college education.

Policy and research implications

This report does not investigate why mortality is increasing, a major research challenge begun by others56 but beyond the scope of this study. Our goal was to raise public awareness, in particular to present the evidence that the problem of increasing mortality rates is much larger than the opioid epidemic and affects more than one race. Death rates are increasing across the US population for dozens of conditions. Of particular urgency is recognizing that the unfavorable mortality pattern that began for some groups in the 1990s is now unfolding among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks, a development made more consequential by their high baseline mortality rates. That these increases are just becoming apparent provides a window of opportunity for early intervention. A chance exists to prevent expansion of this public health crisis through action by policy makers to deal with the social determinants of health, and by researchers to intensify investigation of the causes and solutions.

What is already known on this topic

Mortality rates among whites aged 25-64 years (midlife) have increased since the 1990s, a trend attributed primarily to drug overdoses, alcohol related liver disease, and suicides

Prior studies suggested that this trend was not occurring among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, the largest minority populations in the US

What this study adds

Midlife mortality rates in the US are increasing not only among non-Hispanic whites but also among Hispanics and non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, blacks, and Asians and Pacific Islanders

Although drug overdoses, alcohol related liver disease, and suicides played a major role, mortality rates also increased across a broad spectrum of diseases involving multiple body systems

The wide range of affected conditions points to the need to examine systemic causes of declining health in the US

Acknowledgments

We thank Lauren Snellings for her assistance in error checking the text, tables, and figures.

Web extra.

Extra material as supplied by authors

Supplemental material: additional information

Contributors: SHW led the preparation of the manuscript. He is the guarantor. JMB and KJB obtained the source data. DAC oversaw quantitative methods. Along with the other contributors, EBZ and SMB reviewed drafts and recommended editorial modifications. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was unfunded. The methods used for this study were developed in prior research to examine mortality rates in the US white population. The prior studies were funded by the California Endowment, the Missouri Foundation for Health, and the Kansas Health Institute, but these funders protected the independence of the investigators and had no role in this study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The manuscript’s guarantor (SHW) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, Arias E. Deaths: Final Data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2017;66:1-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kochanek KD, Murphy S, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief 2017;(293):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:15078-83. 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Squires D, Blumenthal D. Mortality Trends Among Working-Age Whites: The Untold Story. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2016;3:1-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2016;65:1-122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kochanek KD, Arias E, Bastian BA. The effect of changes in selected age-specific causes of death on non-Hispanic white life expectancy between 2000 and 2014. NCHS Data Brief 2016;(250):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2015. NCHS Data Brief 2016;(267):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shiels MS, Chernyavskiy P, Anderson WF, et al. Trends in premature mortality in the USA by sex, race, and ethnicity from 1999 to 2014: an analysis of death certificate data. Lancet 2017;389:1043-54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30187-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Case A, Deaton A. Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century. Brookings Pap Econ Act 2017;2017:397-476. 10.1353/eca.2017.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Masters RK, Tilstra AM, Simon DH. Explaining recent mortality trends among younger and middle-aged White Americans. Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:81-8. 10.1093/ije/dyx127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stein EM, Gennuso KP, Ugboaja DC, Remington PL. The epidemic of despair among white Americans: trends in the leading causes of premature death, 1999-2015. Am J Public Health 2017;107:1541-7. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khazan O. Middle-aged white Americans are dying of despair. Atlantic 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/11/boomers-deaths-pnas/413971/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krugman P. Despair, American style. New York Times. November 9, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/09/opinion/despair-american-style.html Accessed March 20, 2018.

- 14. Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital signs: racial disparities in age-specific mortality among blacks or African Americans—United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:444-56. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Astone NM, Martin S, Aron L. Death Rates for US Women Ages 15 to 54: Some Unexpected Trends. Urban Institute, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1445-52. 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]