Abstract

Iron overload cardiomyopathy (IOC) is a major cause of death in patients with diseases associated with chronic anemia such as thalassemia or sickle cell disease after chronic blood transfusions. Associated with iron overload conditions, there is excess free iron that enters cardiomyocytes through both L- and T-type calcium channels thereby resulting in increased reactive oxygen species being generated via Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions. It is thought that an increase in reactive oxygen species contributes to high morbidity and mortality rates. Recent studies have, however, suggested that that it is iron overload in mitochondria that contributes to cellular oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, cardiac arrhythmias as well as the development of cardiomyopathy. Iron chelators, antioxidants and/or calcium channel blockers has been demonstrated to prevent and ameliorate cardiac dysfunction in animal models as well as in patients suffering from cardiac iron overload. Hence, either a mono-therapy or combination therapies with any of the aforementioned agents may serve as a novel treatment in iron-overload patients in the near future. In the present article, we review the mechanisms of cytosolic and/or mitochondrial iron load in the heart which may contribute synergistically or independently to the development of iron associated cardiomyopathy. We also review available as well as potential future novel treatments.

Keywords: Iron overload cardiomyopathy, cytosol, mitochondria, animal models, treatment

Iron is a transition element which forms essential complexes for oxygen transport, participates in cellular respiration and acts as a catalyst for oxidation and reduction reactions. In living organisms with closed biological systems, a fine balance must be achieved in order to maintain a physiologic concentration of the metal so as to avoid too low a level of iron (e.g. anemic states) or overloaded cellular concentrations (iron toxicities), either of which can result in high levels of patient morbidity and mortality.

1. Clinical Conditions with Iron Overload

There are “primary” and “secondary” causes for iron overload conditions. Primary iron overload, i.e. hereditary hemochromatosis is a genetic disorder whose pathophysiology generally involves the absorption of a high level of iron via dietary sources. There are four common causes of genetic hemochromatosis [57]. Type 1, or “classical” hemochromatosis often results from mutations of the human hemochromatosis protein gene (HFE) (i.e. C282Y) which disrupts its interactions with transferrin receptor protein 1 (TfR), and ultimately manifests as a dysregulation of iron import/storage [2]. Type 2A and 2B or “juvenile” hemochromatosis often results from mutations in the juvenile hemochromatosis gene (HJV), which results in deficient hemojuvelin production [1], or in more limited cases, mutations in the hepcidin antimicrobial peptide gene (HAMP) that results in a deficiency of hepcidin [111]. Type 3 hemochromatosis results from mutations in the transferrin receptor 2 gene (TfR2) that result in a deficiency in the production of transferrin receptor 2 [112]. Type 4 hemochromatosis, sometimes referred to as “African iron overload” or “Ferroportin disease”, is caused by mutations of the solute carrier family 40 member 1 (SLC40A1) gene that encodes for ferroportin 1 (FPN 1) [75, 89, 134].

Secondary or “transfusional” iron overload is seen in conditions that require frequent blood transfusions [40, 105, 139] such as beta-thalassemia major [40, 74, 118] and sickle cell anemia [40, 81]. Moreover, non-regular-blood-transfusions can also result in iron overload in patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia, hemoglobin (Hb) E/beta-thalassemia, as well as Hb H and Hb H/Constant Spring diseases [125, 135].

2. In-vitro or In-vivo Models of Iron Overload and Iron Overload Cardiomyopathy

In vitro delivery of Fe2+ into the cytosol of cells remains challenging. At high concentrations, Fe2+ is typically oxidized to its ferric form (Fe3+) and often precipitates in physiological solutions. Addition of vitamin C (ascorbate) prevents such precipitation and may thereby allow Fe2+ to enter the cell via the LTCC [128]. Meanwhile, vitamin C may also enter the cell though the facilitative glucose transporter 1 [51] and the Na+ -dependent L-ascorbic acid transporter [127]. However, since one of the proposed mechanisms involved in iron toxicity is an increase in oxidative stress levels, adding vitamin C which itself is an antioxidant agent complicates the interpretation of the pure pathological effects of iron itself. In fact, some studies have shown that due to its antioxidant properties vitamin C can provide a measure of cardioprotection during treatment with doxorubicin [71]. On the other hand, vitamin C has been demonstrated to paradoxically behave also as a pro-oxidant and to contribute to the formation of H2O2 in the presence of Fe2+ [17]. It has been reported that large doses of vitamin C mobilize iron from iron-binding proteins and in turn catalyze lipid peroxidation in guinea pigs, which further complicates data interpretation and human clinical relevance [50]. Therefore in future studies, special attention is needed when studying the effects and drawing conclusions regarding the role played by antioxidants in the treatment of iron overload.

Recently, an alternative method for in-vitro cellular iron loading has been reported. Fe overload can be achieved in mouse cardiomyocytes or cardiofibroblasts by utilizing ferric ammonium citrate (FAC, at 145.6 μg/ml, which equals 20 μg Fe/ml) [22], or in rat cardiac myocyte H9c2 cells (FAC at 200 or 300 μM) [30].

To get Fe3+ or Fe2+ into the cytosol, some studies use a soluble complex of Fe3+ and a membrane permeable iron chelator 8-hydroxyquinoline (8-HQ). 8-HQ is typically given in similar concentrations or at or twice the concentration of the desired amount of Fe3+ loading (e.g. 15–100 uM) [109]. Upon complexing with the 8-HQ, Fe3+ can then pass through the cellular lipid bilayer and enter the cytosol. After this lipophilic Fe3+/8-HQ complex enters into the cell, Fe3+ ions undergo rapid intracellular reduction to Fe2+ [97]. Cytosol Fe3+ and Fe2+ can then become part of the pool of labile iron (i.e. chelatable and redox-active iron) [109]. While 8-HQ can bind to Fe3+ effectively, it cannot effectively remove Fe3+ from the cell [51, 71, 107, 127, 128].

In in-vivo animal models, the most common methods for establishing iron overload are iron dextran injections and dietary iron supplement as summarized in Table 1. Time duration and dose of iron dextran injection or amounts of iron supplemented in the diet can vary depending not only on the species being studied but based on gender as well. Among the species of animals most often studied (e.g. mice, rats, gerbils, and guinea pigs) mice and gerbils receiving intraperitoneal injection of iron dextran are recommended as being preferred models that best mimick transfusion related iron overload that is clinically seen in patients [45]. Many studies have also demonstrated that mice receiving iron dextran injections develop increased cardiac iron concentrations, have increased cardiac oxidative stress and reduced cardiac antioxidant(s), demonstrate altered intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, and have increased mitochondrial damage that result in cardiac arrhythmias and contractile dysfunction [5, 21, 22, 45, 113]. In addition, iron overloaded Mongolian gerbils show similar pathophysiological changes as reported in patients with iron overload who develop cardiomyopathy [80, 83, 133, 140, 145]. However, it has been reported that cardiac and hepatic iron concentrations in the gerbil model are much higher than levels reported in humans with iron overload [49] suggesting that iron overloaded gerbils may not reliably mimic IOC in patients [49]. We have, however found that rats chronically fed a high iron diet may also serve as a potential IOC model that mimics clinical observations of patients with IOC [137, 138, 141].

Table 1.

Currently available animal models for studying iron overload cardiomyopathy

| Animal models | Strain (sex), dose, route and duration of iron administration | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse -Iron dextran injection |

A) C57/BL6 (M & F): 0.2 mg/g body weight (i.p. same below), 5 days/wk for 4 wks, followed by 0.05 mg/g for 8 more wks [21, 22]. B) CD1 mice (M): 0.6 mg/g, 3 days/wk for 4 wks [113]. C) B6D2F1 and FVB with LTCC overexpression (M): 0.4 mg/g, 5 days/wk for 2.5 weeks, followed by 0.05 mg/g for 12 more wks [86, 87]. D) B6D2F1 (M): 5, 10 or 20 mg/mouse/day for 20 days [23, 24], or 5 days/wk for up to 4 wks [4, 5, 20]. E) C57/BL6 (F): 10 mg/mouse/day, 5 days/wk for 2, 4, or 6 wks [77]. F) Beta-thalassemic: 10 mg/mouse/day, 5 days/wk for 4 wks [47]. |

Cardiac function: ↓ LV diastolic function [22, 86, 87], or only in males [21], ↓ LV systolic function [86, 87], or ↔ LV systolic function [21, 77] ECG, heart rate: PR-interval prolongation, heart block, and atrial fibrillation [113], ↓ heart rate [4, 86, 87, 113], or ↓ heart rate in only males [21] Iron overload: ↑plasma iron [77], ↑ cardiac iron [4, 5, 20–22, 24, 47, 77, 86, 87], ↓ cardiac MRI T1, T2 and T2* [47] Cardiac oxidative stress: ↑ DHE [22], ↑ MDA [4, 5, 22–24, 86, 87], ↑ 4-HNE [4, 5, 23, 24, 86, 87], ↑ hexanal [4, 5, 24, 86, 87], ↑ 3-hydroxydecan-2-one [23], ↑ 4-HNE, MDA, DCF, and DHE only in males [21] Cardiac antioxidant(s): ↓ GSH [22, 87], ↓ GPx [4, 5, 24], ↓ GSH only in males [21] Ca2+ handling and ion channel: ↑ diastolic Ca2+ levels and prolonged Ca2+ decay [22], ↓ LTCC [113], ↓ SERCA2a [22], ↑ NCX [22], or ↔ SERCA2a and NCX [21] Cardiac mitochondria: ↑ mitochondrial damage [5] Cardiac apoptosis: ↑ apoptosis [86, 87], or ↔ apoptosis [21] Cardiac fibrosis: ↑ collagen and fibrosis [22, 86, 87], or ↑ only in males [21] Cardiac hypertrophy: ↑ ventricle wall thickness and diastolic volume [77] |

| Mouse - Iron chow diet |

A) Hemojuvelin knockout and WT (M & F) [21, 22, 41]: Fed with Prolab®RHM 3000 diet containing iron 380 pm [21, 22], or chow diet containing iron 1400 ppm [85] for 24 weeks. B) Thalassemic muβth-3/+ (BKO) and WT muβ+/+ (M): Fed with chow diet containing ferrocene (0.2% w/w) for 16 weeks [54, 59, 63, 126]. |

Cardiac function: ↓ LV diastolic function [22], or only in males [21], ↓ LV systolic function [54], ↓ LVESP, ↓ dP/dtmax, ↓ stroke volume, ↓ cardiac output [59, 63] ECG, heart rate: ↔ heart rate [59, 63, 126], ↓ heart rate variability [54, 59, 63, 126] Iron overload: ↑ plasma NTBI [54, 59, 63, 126], ↑ cardiac iron [21, 22, 54, 59, 63, 85, 126] Oxidative stress: ↑ plasma MDA [59, 63, 126], ↑ cardiac DHE [22], ↑ MDA [22, 54, 59, 63], ↑ 4-HNE [22], as well as ↑ cardiac 4-HNE, ↑ MDA, ↑ DCF, and ↑ DHE only in males [21] Cardiac antioxidant(s): ↓ GSH [22], ↓ GSH only in males [21] Ca2+ handling or ion channel: ↔ SERCA2a and NCX in both M and F [21],↑ TTCC mRNA in BKO mice [59], ↔ LTCC [63] Iron transporter and regulatory proteins: ↔ DMT1[63], ↔ ZIP14 [63], ↔ Hepcidin [63], ↔ Ferroportin 1 [63] Cardiac mitochondria: ↑ ROS, ↑ depolarization, ↑ swelling [54, 63]; ↓ complex IV, ↓ complex V in BKO mice, ↑ biogenesis in BKO mice [54] Cardiac Apoptosis: ↔ Apoptosis [21], ↑ cleaved-caspase3 [54], ↑ pro-caspase3 in BKO mice [63] Cardiac fibrosis: ↑ collagen and fibrosis [22] |

| 3. Rat -Iron chow diet |

A) Wistar (M): Fed with chow diet containing ferrocene (0.2% w/w) for 16 weeks [137, 138]. B) Sprague-Dawley (M and F): Fed with 10,000 ppm carbonyl iron diet for 30 days [141]. |

Cardiac function: ↓ LV systolic function [137, 138], ↓ LVESP [138, 141], ↑ LVEDP [141], ↓ Pmax, ↓ stroke volume, ↓ cardiac output [138] ECG, heart rate, heart rate variability: ↔ heart rate [138], or ↓ heart rate variability [138] Iron overload: ↑ plasma NTBI, ↑ cardiac iron [137, 138] Oxidative stress: ↑ plasma MDA, ↑ cardiac MDA [137, 138] Ca2+ handling or ion channel: ↑ diastolic Ca2+ levels, ↓ Ca2+ decay rate, ↓ Ca2+ transient amplitude, ↓ Ca2+ rising rate, ↔ LTCC, ↑ TTCC, ↓ SERCA, ↔ NCX [137] Iron transporter and regulatory proteins: ↔ DMT1, ZIP14, Hepcidin, Ferroportin 1 [137] Cardiac mitochondria: ↑ ROS, ↑ depolarization, ↑ swelling [138] |

| 4. Gerbil -Iron dextran injection |

Mongolian Gerbil (F): 200 mg/kg/wk (s.c.) for a duration staring from 10 and up to 75 weeks [80, 83, 84, 140, 145], or i.p. for 14, 16 or 18 weeks [133]. 800 mg/kg/wk (s.c.) for a duration staring from 5 and up to 20 weeks [69, 80, 144, 145]. |

Cardiac function: ↔ LV systolic function [145], ↓ dP/dtmax, ↑ dP/dtmin [144, 145] ECG, heart rate: ↓ heart rate, ↑ QT interval, ↑ST elevation, T- wave inversion, and PVCs [80], ↑PR interval and QRS interval, atrioventricular block [69, 80] Iron overload: serum iron [83, 144], ↑serum ferritin [133], ↑ cardiac iron [80, 83, 84, 133, 140, 144, 145], ↑cardiac MRI 1/T2*, 1/T2, and 1/T1 [140] Heart failure markers: ↑cardiac troponin I [133], ↑ cardiac NT- proBNP [133] Oxidative stress: ↑ Cardiac MDA [83, 133] Cardiac antioxidant(s): ↓ glutathione peroxidase [83, 133] Cardiac mitochondria: ↑ mitochondrial swelling [133] Cardiac fibrosis: ↑ collagen and fibrosis [133] Cardiac hypertrophy: ↑ LV mass [145], ↑ LV wall thickness [144] |

Note: A recent study has demonstrated that differences are often based on gender differences. i.p. = intraperitoneal; s.c.=subcutaneous; ECG= electrocardiogram; MRI= magnetic resonance imaging; NTBI= non-transferrin bound iron; ROS= reactive oxygen species; DCF=dichlorodihydrofluorescein; DHE= dihydroethidium; MDA= malondialdehyde; 4-HNE= 4-hydroxynonenal; GSH=Glutathione; GPx= Glutathione peroxidase; LTCC= L-type calcium channel; TTCC= T-type calcium channel; SERCA2a= sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2a; NCX= sodium-calcium exchanger; DMT1= divalent metal transporter 1; ZIP14= Zrt- and Irt-like protein 14; LVESP = left ventricular end-systolic pressure; LVEDP= left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; Pmax= maximum pressure; dP/dtmax = maximum value of the first derivative of left ventricular pressure; dP/dtmin = minimum value of the first derivative of left ventricular pressure; NT-proBNP= amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

As for iron overload models using genetically modified animals, hemojuvelin knockout mice when fed a high iron diet [21, 22, 85] and beta-thalassemic mice given either iron dextran injections [47] or feed an iron enriched diet [64] have been used to mimic cardiac iron overload in patients with juvenile hemochromatosis and transfusion dependent beta-thalassemia, respectively. These genetically altered mouse models are thought to be more suitable for investigating the pathophysiology and treatment of IOC in hereditary hemochromatosis and β-thalassemia conditions. It has been found that both FPN 1 and hepcidin are expressed in cardiomyocytes. Recent studies have demonstrated that mice with cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of FPN 1 have severely impaired cardiac function due to high levels of iron accumulation in cardiomyocytes [67], despite unaltered systemic iron status. On the other hand, mice with cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of hepcidin develop fatal contractile and metabolic dysfunction as a consequence of cardiomyocyte iron deficiency while maintaining normal systemic iron homeostasis [68].

Friedreich ataxia (FA) is an example showing that mitochondrial Fe overload mediates a disease condition in the heart and brain. Most cases of FAs are caused by loss of function mutations, e.g. an expanded trinucleotide (GAA) repeat in the frataxin (FXN) gene located on chromosome 9q13 and is characterized by progressive gait and limb ataxia as well as cardiomyopathy. Frataxin is a mitochondrial protein that can bind to Fe and is involved in iron–sulfur cluster (ISC) biogenesis and heme synthesis within mitochondria. It has been suggested that in FA patients the defect expression or function of frataxin results in deleterious alterations in iron metabolism. The pathology of FA is mediated by an excess of “free” iron in mitochondria that may lead to oxidative stress and subsequently cause damage/degeneration of mitochondria and cells. Please see recent review articles for details on FA [19] and animal models of FA [91].

Notably, several recent studies have indicated that induction of cardiac iron overload can differ in female vs. male mice [10, 11, 21]. Male mice appear to be more susceptible than female mice to iron-mediated cardiac toxicity and the development of IOC. Cardiac iron overload appears to occur more slowly in female mice [11], whereas IOC is more easily induced in males [21]. There have been several hypotheses put forth to explain why female mice are more resistant to IOC than males. It has been demonstrated that the iron exporter FPN 1 mRNA is upregulated to a larger extent in females compared to males in response to cardiac iron accumulation thereby potentially resulting in reduced cardiac iron concentrations in females [11]. Furthermore, the level of intracellular anti-oxidative glutathione is higher in females than males leading to females being more protected against iron-mediated cardiotoxicity via oxidative stress [21]. 17β-Estradiol or estrogen which is the primary female sex hormone may play an important role in protecting female mice from IOC [21]. Deficient estrogen levels in ovariectomized female mice has been linked to cardiac dysfunction as well as cardiac iron overload similar to what has been reported in male mice [21]. Similarly, estrogen treatment has been shown to ameliorate IOC in male mice [21]. However, an earlier study reported that estrogen therapy increased cardiac iron accumulation in castrated male mice [10]. Therefore, the idea that estrogen therapy can be used to prevent or treat iron overload associated cardiomyopathy requires further investigation [10, 21]. No similar studies or analyzes have been reported to our knowledge on male or female (pre-menopausal or post-menopausal) patients suffering from chronic iron overload cardiomyopathy. The standard of care for both male and female patients with iron overload cardiomyopathy as a result of, for example beta thalassemia, is the same (e.g. Deferoxamine, DFO, 20–40 mg/kg/day over 8–24 hours, 5 days/week) [101].

There are also sparse reports using other animal species as models of iron overload, such as guinea pigs [48]. In a report, it was demonstrated that iron per se may not be sufficient to induce cardiac arrhythmias in iron-loaded guinea pigs, suggesting arrhythmic events observed in patients with iron overload may also be the result of a complex interplay of multiple factors.

3. Proposed Mechanisms Involved in the Pathogenesis of Iron Overload Cardiomyopathy

3.1. Iron uptake, metabolism, and export in the cell and mitochondrion

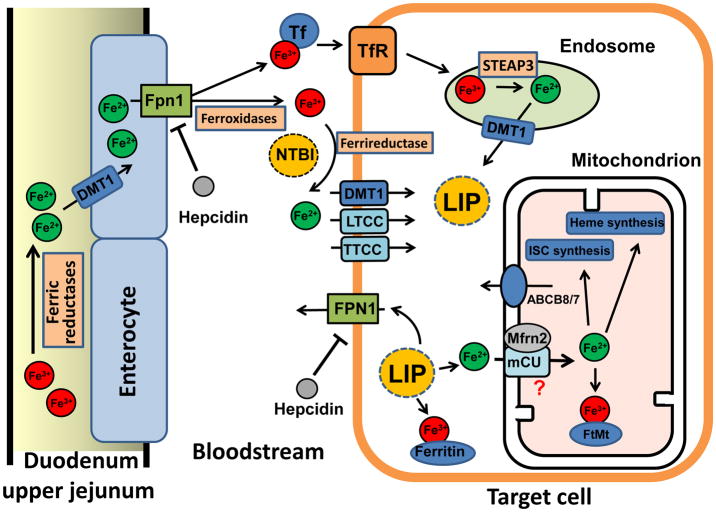

The pathogenesis of iron overload associated cardiac toxicity is attributed to the dysregulation of iron homeostasis. Iron metabolism pathways are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Dietary uptake, membrane import, export, and metabolism of iron in the cell and mitochondrion.

See details in section 3.1.

ABCB8/7: ATP-binding cassette protein B8 or 7; DMT1: divalent metal transporter1; Fe3+: ferric iron; Fe2+: ferrous iron; FPN1: Ferroportin 1; FtMt: mitochondrial ferritin; ISC: iron sulfur cluster; LIP: labile iron pool; LTCC: L-type calcium channel; Mfrn2: mitoferrin 2; mCU: mitochondrial calcium uniporter; NTBI: Non-Tf bound iron; STEAP3: Six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3, an endosomal reductase; Tf: Transferrin. TfR: Transferrin receptor; TTCC: T-type calcium channel

Ferric iron (Fe3 +) from the diet is imported into enterocytes by the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT) after being converted to ferrous iron (Fe2+) in the duodenum by ferric reductases (Fig. 1, left). Fe2+ is then exported into the bloodstream by ferroportin 1 (FPN 1). The export of Fe2+ is coupled to its conversion back to Fe3 +, which is catalyzed by ferroxidases. After being absorbed by enterocytes of the duodenal and upper jejuna epithelia, iron then enters the blood in the Fe3+ state, which is bound to the iron transport protein transferrin (Tf). Each molecule of Tf can bind two molecules of Fe3+ with high-affinity and transport them to organs of the body. Under certain pathological conditions when iron release is increased into the circulation, the carrying capacity of Tf becomes saturated and non-Tf bound iron (NTBI) will appear in the serum [10].

Iron can be taken up by cells in both the Tf-bound form and the NTBI form (Fig. 1, target cell). In the former case, the Fe3+-Tf complex binds with the transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) and enters the cytosol via a receptor-mediated endocytosis (i.e. endosome). Fe3+ is released from Tf in the acidified endosome and is then reduced to Fe2+ by an endosomal reductase (e.g. STEAP3). Fe2+ is then transported into the cytosol via DMT1 and becomes part of the intracellular labile iron pool (LIP). This Tf bound Fe3+ and TfR1-mediated uptake pathway has been thought to play a crucial role in the metabolism of erythroid precursors (hemoglobin production) and in the metabolism of hepatocytes. However, recent studies in mice lacking cardiac TfR1 have demonstrated that TfR1 may also mediate iron uptake in the heart, which is important for cardiac iron metabolism and function [142].

In conditions of iron overload, NTBI exists not only in the blood but can also be taken up by cells in various organs. The first step of NTBI uptake involves the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ by a membrane-associated ferrireductase [108] such as duodenal cytochrome b (DCYTB) or ascorbate. It has also been proposed that the newly formed Fe2+ can possibly enter the cell via the sarcolemma divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) [52]. In addition, some Ca channels such as L- [128] or T-type Ca channels [62] may also be routes for cellular Fe2+ import. In the cytosol, free iron or NTBI is taken up in increasing amounts and is incorporated into the cellular labile iron pool (LIP). NTBI is taken up preferentially by the liver, kidney, pancreas, and heart under iron overload conditions. Since Fe toxicity is related to free Fe that is redoxactive, increases of NTBI uptake can lead to cell damage including in the heart. Therefore, NTBI may serve as a unique marker and may be clinically useful in iron overloaded patients [46].

After entering into the cytosol (Fig. 1, Target cell), iron can follow three metabolic pathways, i.e. 1) be stored in the ferric form with the storage protein ferritin, which also shows ferroxidase activity, 2) be taken up in the ferrous form into the mitochondrion, or 3) be exported in the ferrous form from the cell by Fpn1. When hepatic iron levels are high, hepcidin is secreted by the liver into the circulation. Hepcidin binds to Fpn1 and causes its internalization and degradation by enterocytes on the basolateral membrane, as well as degradation by hepatocytes and macrophages. This process prevents further dietary Fe uptake and iron export from the liver, respectively, therefore reducing serum Fe availability to other tissues. As a result of these pathways either hepcidin deficiency or alterations in its target, Fpn1, may result in Fe overload.

As mentioned above, a portion of cytosolic iron in the ferrous form is taken up into mitochondria (Fig. 1, Mitochondrion). Some studies have demonstrated that two important iron importer proteins, mitoferrin-1 and 2 (Mfrn1 and 2) are localized on the inner membrane of mitochondria and may play an important role in iron uptake into the mitochondrial matrix [90, 110, 117]. A study has demonstrated that mitoferrin1 and 2 are reduced by RNA interference and can lead to a decrease in mitochondria iron concentrations [90]. Hence, it has been suggested that Mfrn1 and 2 are mitochondrial iron importers and might account for iron uptake into mitochondria. While Mfrn1expression is restricted to erythroid-lineage cells, Mfrn2 is expressed ubiquitously including in the heart. In addition, a very recent report has proposed that the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (mCU) may also transport iron into mitochondria, while Mfrn2 serves to regulate mCU transport [78]. Iron in the mitochondrion can then be utilized for 1) storage in mitochondrial ferritin (FtMt); 2) synthesis of iron-sulfur clusters (ISC); and 3) heme synthesis which is necessary for erythropoiesis and mitochondrial metabolism under normal physiological conditions [110].

The molecular identity of the mitochondrial iron exporter remains unknown. However, a member of the ABC protein family ABCB8 has been found to facilitate the export of iron from mitochondria [42], while ABCB7 is involved in the maturation of cytosolic ISC proteins [7]. Mitochondrial iron overload has been found in HeLa cells after RNA silencing of the mitochondrial ABCB7 gene [13]. Genetic deletion of ABCB8 results in accumulation of mitochondrial iron and the development of a cardiomyopathy phenotype [16, 42]. Conversely, overexpression of ABCB8 reverses DOX-induced toxicity [43] and ischemic cardiac injury [16] via reduction of mitochondrial iron load.

3.2. Iron overload catalyzed reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation

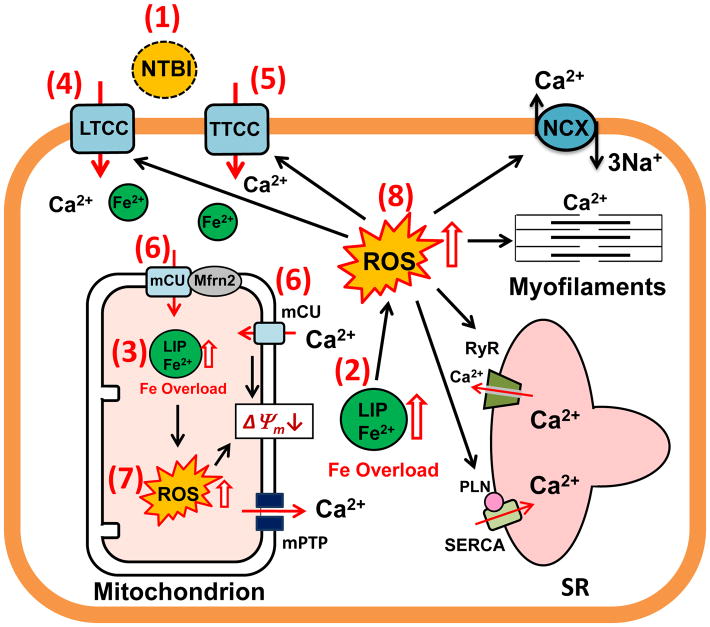

Iron overload-mediated oxidative stress and the proposed effects on mitochondrial and cellular function are illustrated in Fig. 2. One of the most damaging effects of iron overload is the generation of free radicals via Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions [9, 38, 58]. Initially, during the first portion of the Haber-Weiss reaction, Fe3+ is reduced by superoxide to generate Fe2+ and oxygen [56, 58]. The next step, known as the Fenton reaction, results in the Fe2+ being oxidized by hydrogen peroxide to form Fe3+, hydroxide ions (OH−) and hydroxyl radicals (HO•) which are very reactive and toxic free radicals [56, 58]. Please note that iron acts as a catalyst in these reactions and the generation of the hydroxyl radical requires the cycling between Fe2+ and Fe3+ and concurrent presence of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Ultimately, these free radical byproducts can engage in secondary oxidation reactions in the mitochondria and to some degree in the cytosol as well [58, 136]. It is not known to which extent the detrimental effect of iron results from circulating “free” iron v.s. intracellular LPI.

Figure 2. Iron overload-mediated oxidative stress and effects on mitochondrial and cellular function.

Potential targets for treatment are indicated by the numbers 1–8 in the parentheses.

LIP: labile iron pool; LTCC: L-type calcium channel; mCU: mitochondrial calcium uniporter; mPTP: mitochondrial permeability transition pore; Mfrn2: mitoferrin-2; NCX: Na-Ca Exchanger; NTBI: Non-Tf bound iron; PLN: Phospholamban; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; RyR: Ryanodine Receptor; SR: Sarcoplasmic Reticulum; SERCA: SR Ca2+ ATPase; TTCC: T-type calcium channel

Under iron overload conditions, the transferrin protein can become saturated and therefore cannot bind all of the free iron in the plasma leading to increased levels of iron free of transferrin or NTBI [9, 38, 39, 98]. Furthermore, labile plasma iron (LPI) levels are also increased when NTBI levels are elevated [9]. LPI represents the redox active and chelatable fraction of NTBI and is capable of permeating into cells and organs. LPI is directly associated with iron overload-induced cellular and tissue damage that can result in organ dysfunction [102]. Therefore, high levels of NTBI can lead to an increase in plasma and cellular LPI levels and enhance the formation of ROS which eventually can affect multiple organ systems resulting in a multitude of pathological effects e.g. arthritis [114], cirrhosis of the liver [70], depletion of beta cells in the pancreas contributing to diabetes [100], and cardiomyopathy [22, 34, 54, 59, 63, 137, 138]. Recent studies have also suggested that the generation of reactive oxygen species may also affect the vasculature. For example, Marques et al has shown that iron overloaded rats show a reduction in nitric oxide production and an overall loss of vascular tone [73].

Enhanced ROS generation has been shown to result in depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential and to lead to the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore [61, 120]. In addition, iron overload-mediated ROS accumulation has been demonstrated to cause cardiomyopathy in thalassemic mice [54, 61, 63]. Furthermore, increased ROS levels have been shown to induce not only cardiac dysfunction, but also brain damage in iron overload rats [121, 123, 137, 138]. Moreover, iron overload-provoked ROS production can disturb cardiac intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis leading to diastolic and systolic dysfunction in mice and rats [22, 137].

3.3. The effect of iron overload on ion channels and contractility

Although there are several portals for iron entry into cardiomyocytes, several studies have demonstrated that Fe2+ enters the cell via the LTCC [86, 88, 128] or TTCC [59, 62]. At low concentrations of Fe2+, this effect results in a slowing of Ca2+ current inactivation and results in an increase in basal intracellular Ca2+ levels that eventually lead to contractile dysfunction [128]. The slow channel inactivation may be caused by Fe2+ competing with Ca2+ for the C-terminal cytoplasmic Ca2+ binding site involved in Ca2+-mediated inactivation of LTCC, or possibly by an increase in channel oxidation as a result of free radical production [18, 33, 128]. A recent study has demonstrated that during the early stages of IOC, there is an increase in diastolic Ca2+ levels and a prolonged Ca2+ decay in ventricular cardiomyocytes [22]. Additionally, due to a sustained current component, a slowing of LTCC inactivation may also allow an increase in Fe2+ influx into cardiomyocytes leading to increased ROS and impaired sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) function that results in diastolic dysfunction in the early stages of iron overload [22, 137].

Animal models of iron overload have demonstrated changes in expression levels of calcium handling proteins such as SERCA2a and the sodium-calcium exchanger [22]. Indeed, in heart failure due to iron overload, SERCA2a levels have been reported to be reduced, leading to disturbed cytosol Ca2+ re-uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum and resulting in impaired myocardial relaxation [22, 137]. Meanwhile, sarcolemmal sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) levels have been shown to be increased [22] in some, but not all animal models of iron overload. Overexpression of NCX with higher protein levels may be a protective effect as a result of a Ca2+ overload state and an attempt to maintain a normal diastolic [Ca2+] in early IOC. On the other hand, at high concentrations of Fe2+, peak Ca2+ current has been reported to be decreased [128]. The reported decrease in Ca2+ current amplitude may result from Fe2+ competing with Ca2+ to enter cardiomyocytes leading to decreased intracellular Ca2+ levels and thereby reducing SR calcium release during the late stages of iron overload [128]. At high concentrations Fe2+ competes with Ca2+ to interact with SR ryanodine receptors (RyRs) which can lead to a reduction in Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the SR, heart contractility, and function [55]. Wongjaikam et al have demonstrated that intracellular Ca2+ transient amplitude is decreased, contributing to decreased left ventricular systolic function in chronic iron overloaded rats [137]. Therefore, chronic iron overload leads to impaired cardiac intracellular Ca2+ transients and results in impaired cardiac contractility [137].

Interestingly, a study by Kumfu et al found that Fe3+ can also enter cardiomyocytes and cause cardiac iron overload [60]. However, Tsushima et al indicated that Fe3+ did not alter Ca2+ current amplitude or decay via LTCC in ventricular myocytes [128]. In addition, Fe3+ entry into cardiomyocytes was not prevented by using blockers of TfR1, DMT1, LTCC, or TTCC indicating that Fe3+ influx into cardiomyocytes did not enter through these metal entry portals [60]. These studies possibly indicate that there is/are other pathway(s) for Fe3+ to enter cardiomyocytes of the heart and warrant further investigation.

3.4 The effect of iron overload on mitochondrial function

Mitochondrial iron is necessary for heme biosynthesis and iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis, which are important for erythropoiesis and mitochondrial metabolism under normal physiological conditions [110]. However, excess iron in mitochondria can lead to dysfunction of these important homeostatic activities supported by normal mitochondrial function. Studies by Sripetchwandee et al. and Kumfu et al. have shown that mCUs are involved in brain and heart mitochondrial dysfunction under iron overload conditions [61, 120, 122]. These studies have demonstrated that both Fe2+ and Fe3+ are capable of entering mitochondria. However, they proposed that Fe2+ might be more harmful to the mitochondria. Fe3+ causes mitochondrial ROS generation and mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization to a lesser extent and, it does not appear to induce mitochondrial swelling in isolated cardiac mitochondria [120]. It is conceivable that once inside the mitochondria and participating in the generation of free radicals by the Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions, free iron is capable of generating mitochondrial ROS that then can depolarize the mitochondrial membrane potential and in turn open the mitochondrial permeability transition pore resulting in mitochondrial swelling [61, 120]. Therefore, it is most likely that iron-induced mitochondrial damage and dysfunction can cause cardiomyopathy and heart failure, but warrants further investigation.

3.5. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity mediated by iron

Doxorubicin (DOX), an anthracycline that is sold under the brand names Adriamycin® or Doxil®, is one of the most effective and commonly used chemotherapeutic agents used to treat neoplastic tumors [129]. While this drug is effective at inhibiting the topoisomerase enzyme and thereby preventing DNA replication and cell division, it has severe cardiotoxic side effects [129]. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity limits its clinical use to a cumulative lifetime dose of 500 mg/m2 [29]. Exposure exceeding this amount can eventually lead to cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure [11, 76]. The mechanism behind this relationship is similar to the “ROS and iron hypothesis”. Iron is necessary for the formation of an oxidized semiquinone in the B ring of doxorubicin. When the oxidized doxorubicin semiquinone-iron complex reacts with oxygen, a fully oxidized form of doxorubicin together with superoxide is then generated [53]. Superoxide dismutase then converts the superoxide to hydrogen peroxide, which in the presence of iron (or other Fenton reagents), is further converted to extremely volatile hydroxyl radicals. Additionally, DOX is thought to form complexes directly with iron causing iron to cycle between Fe2+ and Fe3+ generating additional ROS [143].

Previous attempts to reverse the cardiotoxic effects of DOX have relied upon the use of iron chelators, such as deferiprone [103] or deferasirox [35]. Unfortunately, neither of these chelators were found to be very effective prompting studies that challenged the role of iron in DOX associated cardiac toxicity [119]. As a result of these studies, it has now been suggested that the cardiotoxicity caused by anthracyclines such as DOX and daunorubicin (DAU) may involve other pathways which provoke ROS production and accumulation [119]. Convincingly, recent studies by Ardehali’s group have demonstrated that mitochondrial iron accumulation mediates both doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and cardiac ischemic damage. The selective mitochondrial iron chelator dexrazoxane (DXZ) or overexpression of ABCB8 was demonstrated to reduce the cardiotoxic effects of DOX treatment [43].

4. Iron Overload May Lead to Cardiac Arrhythmias

Iron overload has a well-accepted role in promoting general cardiomyopathy, however, its role in the spontaneous generation of cardiac arrhythmias remains controversial. Studies by Kaiser et al have claimed that guinea pigs [48] do not display arrhythmias, despite showing hallmark symptoms of iron overload such as significant increases in cardiac and hepatic iron deposition and cardiac and liver fibrosis. While these results may suggest that there is no direct link between iron overload and arrhythmogenesis, the authors did not attempt to examine the relationship between iron overload and arrhythmogensis under stressed conditions, such as arrhythmia induction testing, simulated hypercalcemia, or sympathetic hyperactivity (isoproterenol). Nevertheless, several other studies report that chronic iron overload results in arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy in several other animal models [69, 80, 113]. For example, chronic iron overload has been demonstrated to result in prolonged PR-intervals, heart block, and atrial fibrillation in a mouse model [113]. In addition, abnormal ECGs were present in iron overloaded gerbils i.e. they had a prolongation of QRS and PR intervals, premature ventricular contractions, atrioventricular block, ST segment elevation, and T-wave inversion [69, 80].

There is ample human clinical evidence that has demonstrated a link between cardiac arrhythmias and iron overload [6, 14, 36, 44, 72, 79]. In a study comparing a population of thalassemic and healthy children (aged 4 to 19 years old), the thalassemic group showed significant increases in P wave dispersion (as calculated by the difference between the maximum and minimum P wave durations), maximum P wave duration, and peak early mitral inflow velocity. The study conductors concluded that thalassemic patients may have depressed intra-atrial conduction due largely to atrial dilation with increased sympathetic activity as a contributing factor [79]. Another study has examined the link between increased QRS interval, the occurrence of ventricular late potentials, and iron-overload in patients with thalassemia over a 7 year follow up period by using the signal averaged ECG method. The study revealed an increase in mean late amplitude signal duration. There is a significant correlation between increased serum ferritin levels and increases in the QRS interval and decreases in the root mean square voltage of ventricular late potentials [44]. A study by Mancuso et al found that of 28 thalassemic patients suffering from heart failure, 79% had T wave inversions, 46% had supraventricular arrhythmias, 43% had low voltages, and 18% had right QRS interval axis deviations, while their age and sex matched controls had no ECG abnormalities [72]. Case studies of sustained ventricular tachycardias in iron overloaded thalassemic patients have also been reported [6]. Ultimately, a longitudinal study has shown that heart failure can be responsible for more than 71% of deaths in patients suffering from thalassemic hemosiderosis [66]. Therefore, it has been shown that iron overload is associated with cardiac arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy in both animal models as well as in human patients.

5. Treatment for Iron Overload Cardiomyopathy

Efforts have been made to treat iron overload and IOC in both animal models and human patients. Potential targets for treating iron overload and its deleterious influences on cardiac myocytes and mitochondria are indicated in Figure 2 by the numbers 1–8 in the parentheses.

5.1. Iron chelators: targeting iron in plasma, cells, or mitochondria

Currently, there are three common iron chelators that can be used to treat patients with cardiac iron overload, i.e. deferoxamine (DFO), deferiprone (DFP) and deferasirox (DFX) [8, 31, 32, 37, 92, 93, 95, 99, 104]. The gold standard for iron overload chelation therapy is treatment with the iron chelator DFO (Target # 1 in Fig. 2). Indeed, this drug is so popular for the treatment of iron overload that it is included on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. However, it is not without its drawbacks, specifically that it is generally administered via parenteral routes (given that an oral formulation is usually cost prohibitive and not widely available). It has only been demonstrated to be effective in clearing iron from the blood, as it is not very membrane permeable, and cannot effectively chelate intracellular iron particularly in heart tissue. [37, 106]. DFO binds effectively to free iron in the blood, allowing iron to then be excreted in the urine [37]. However, it is less effective at reversing damage done by iron which has already entered the cell or mitochondria [31, 32]. Although treatment with DFO has been considered the gold standard, part of the difficulty with current DFO therapy is the hardship involved with its delivery system, which requires using a pump delivering 20–40 mg/kg/day over 8–24 hours, 5 days/week [101]. Non-compliance leads to significant health complications and dramatic increases in treatment costs [25]. As such, there is a need for the development of membrane permeable iron chelators (preferably in oral formulations).

Recent studies have tested several orally dosed membrane permeable compounds. The drugs deferiprone (DFP or L1) and deferasirox (DFR or DFX) are comparatively small, and are less charged than DFO, and are able to cross the lipid bilayer while still retaining their ability to chelate iron which has not yet entered the cell [31, 32] (Target # 2 in Fig. 2). However, several studies have indicated that DFP nor DFX can remove cardiac iron accumulation or improve cardiac function in transfusion dependent thalassemia (TDT) patients [93, 99, 104]. These drugs have also been shown to bind to labile iron within the cytosol and are claimed to enter the mitochondria as well, as measured by reductions of mitochondrial ROS [31, 32]. Importantly, DFP has been shown to be more effective than DFO or DFX in reducing cardiac iron overload in patients [8, 92, 95]. Wongjaikam et al found that chronic treatment with either DFO or DFX for 2 months improved left ventricular fractional shortening and ejection fraction in iron overloaded rats [137, 138]. Chronic treatment with DFX for 5 years in TDT patients has been reported to diminish cardiac iron concentration and improve end-diastolic and end-systolic left ventricular volumes whereas the percent of left ventricular ejection fraction was not altered [12]. It should also be noted that some studies have reported that DFO or DFX do not improve left ventricular ejection fraction in TDT patients [92, 94].

The membrane permeable chelator dexrazoxane (DXZ), despite lacking a high iron binding affinity as DFO, has been shown to be a more effective cellular and especially mitochondrial iron chelator (Target # 3 in Fig. 2) due to its ability to pass through lipid bilayers. As a result of animal studies, it has been suggested that the mitochondria selective iron chelator DXZ may be more effective in ameliorating the cardiac toxicity associated with DOX [43]. Finally, the membrane permeable heavy metal chelator 2,2-bipyridyl (BPD) has been shown to readily enter into the cytosol and mitochondria and quickly and effectively chelate labile iron in vitro [26, 96]. It has been recently demonstrated that mitochondrial iron may mediate cardiac ischemic damage in mice [16]. Application of BPD (50 and 100 μM) reduces mitochondrial iron levels, consequently protecting cardiomyocytes against H2O2-induced cell death in vitro, as well as provide protection of the heart from ischemia/reperfusion damage in animal models in vivo. In addition, BPD has been demonstrated to protect against the development of cardiomyopathy in cardiac-specific ABCB8 KO mice [16]. As a result of this study, it was suggested mitochondrial iron load plays a critical role in the development of not only cardiomyopathy, but ischemic heart disease as well [15]. Mitochondrion-permeable iron chelators resembling BPD may represent novel therapeutic tools for treating ischemic heart disease.

However, oral formulations such as DFP and DFX are cost prohibitive and less available and also suffer from compliance issues. Therefore, efforts have been made to search for other options, among which one is to develop an organ-targeted liposome entrapped DFO (L-DFO) formulation. We have explored the feasibility of using L-DFO delivery system in rats and have demonstrated that the L-DFO formulation targeted to the liver or the heart requires significantly lower dosages by 50%–75% [141]. This delivery approach may eliminate the need for a pump and the standard week-long administration of DFO, and can be administered at the time of the obligate blood transfusion thereby assuring compliance.

5.2 Calcium channel/transporter blockers: cytosolic vs. mitochondrial targets

It has been suggested that free iron is transported into cardiomyocytes by LTCC [86, 88] or TTCC [59, 62]. Hence, several researchers have hypothesized that calcium channel blockers can decrease cardiac iron concentration, reduce oxidative stress, and attenuate heart disease caused by cardiac iron overload. As expected, many studies have demonstrated that calcium channel blockers provide beneficial effects in treating IOC in both patients and animal models [20, 85, 86, 116, 146]. LTCC blockers (Target # 4 in Fig. 2) including amlodipine and verapamil were effective in treating IOC both in animals [20, 85, 86, 116, 146] and in patients [28, 124]. In an animal model, Oudit et al demonstrated that both amlodipine and verapamil reduced cardiac iron concentration, diminished cardiac oxidative stress, attenuated cardiac damage and inflammation as well as cardiac apoptosis leading to improved hemodynamic and echocardiographic parameters in chronically iron overloaded mice [86]. However, the levels of iron in the liver were not decreased by either amlodipine or verapamil treatment when compared with the iron-loaded group in this study because functional LTCCs are not expressed on liver cells [86]. Therefore, other pathways, such as DMT1, may account for iron uptake into the cytosol in hepatocytes [132].

In another study by Crowe and Bartfay, amlodipine was found to be effective in diminishing heart iron concentration as well as reduced ROS in chronic iron overloaded mice [20]. Verapamil significantly decreased liver and cardiac iron concentrations by approximately 28% and 34% (respectively) in iron-loaded hemojuvelin knockout mice [85] and was effective in reducing myocardial iron levels in diabetic cardiomyocytes of rats [116]. However, the route of iron loading and mouse models used differed in these two studies [85, 86] which may explain why verapamil affected liver iron concentrations differently. Furthermore, verapamil has been demonstrated to exert beneficial effects similar to DFO in reducing cardiac iron deposition and oxidative stress resulting in diminished myocardial collagen and fibrosis in chronically iron overloaded mice [146]. Similarly, LTCC blockers have been shown to be effective in treating thalassemia major patients [28, 124]. After amlodipine treatment, the levels of ferritin were decreased (at 12 months) and cardiac T2* (which is used to evaluate the level of cardiac iron accumulation) [3] was increased at 6 months and 12 months, indicating that cardiac iron concentrations were reduced in thalassemia major patients [28]. Interestingly, the combination therapy of DFO and the calcium channel blocker verapamil was effective in treating left ventricular dysfunction in patients with IOC [124]. Although either calcium channel blocker alone or in combination with an iron chelator has been shown to be effective in treating patients with cardiac iron overload, large clinical trials are needed to validate their cardioprotective effects on IOC.

Additionally, Kumfu et al has demonstrated that the dual TTCC and LTCC blocker efonidipine, (sometimes referred as “TTCC blocker” since it is more efficient in blocking TTCC) [62, 82, 130]; Target # 5 in Fig. 2) exerts beneficial effects in treating IOC. Investigators found that TTCC, LTCC, or DMT1 blockers, or the use of DFO were equally effective in reducing plasma NTBI, cardiac iron concentration, and cardiac oxidative stress as well as improving heart rate variability and left ventricular function in both iron overloaded-wide type and thalassemic mice [59]. In addition, by comparing the effects of the LTCC blocker amlodipine, the TTCC blocker efonidipine, and more commonly used iron chelators including DFO, DFP or DFX, Kumfu et al found that all pharmacological interventions reduced plasma NTBI, decreased cardiac iron concentration as well as improved mitochondrial and left ventricular function in wild type and thalassemic mice [63]. In iron overloaded liver, the TTCC blocker efonidipine, DFO, DFP and DFX provided beneficial effects in diminishing plasma and liver malondialdehyde and liver iron concentration in wild type and thalassemic mice. This was not seen with the LTCC blocker amlodipine [63]. These studies indicate that the TTCC blocker efonidipine was more effective than the LTCC blocker, i.e. verapamil or amlodipine, in treating iron-overloaded liver. They found that this positive effect correlated with a higher survival rate in both wide type and thalassemic mice with iron overload [59, 63]. Nevertheless, the effects of either efonidipine alone or combined with an iron chelator(s) on IOC in patients has not yet been investigated.

Lastly, it has been proposed that free iron is transported into cardiac mitochondria by mCU under iron overload conditions leading to increased mitochondrial ROS, membrane depolarization and swelling as well as mitochondrial dysfunction [61, 78, 120]. Therefore, mCU blockers (i.e. RU360) may provide beneficial effects in reducing mitochondrial iron concentrations and oxidative stress as well as attenuate mitochondrial dysfunction mediated by iron overload (Target # 6 in Fig. 2). As expected, it has been demonstrated that a mCU blocker can effectively prevent mitochondrial ROS, mitochondrial depolarization, and mitochondrial swelling leading to improved cardiac mitochondrial function in isolated cardiac mitochondria after iron loading in both rats and in β-thalassemic mice [61, 120]. Since mitochondrial Ca homeostasis dysfunction can also lead to cellular damage, it remains elusive as to how much of the mCU blockade benefits can be attributed to improved iron load vs Ca homeostasis. Again, upregulation of ABCB8 (a potential iron exporter) has been shown to offer some measure of cardioprotection during doxorubicin induced cardiomyopathy by reducing overall mitochondrial iron loading and ROS generation [43]. Consequently, decreased iron influx by mitochondrial portal blockers and/or increased iron efflux by mitochondrial iron exporters may be a new strategy for treating mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction resulting from iron overload.

5.3 Antioxidants: concomitant iron-chelation therapy on iron overload cardiomyopathy

Although studied extensively, antioxidants’ therapeutic benefits in the treatment/prevention of cardiovascular diseases in general remains controversial. Since oxidative stress (ROS) is thought to be a central player that mediates iron overload-induced toxicity, antioxidant therapy on IOC has also been evaluated. Das et al. have investigated the therapeutic effects of resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic flavonoid, in acquired and genetic models of IOC [22]. It has been shown that the dietary supplementation with resveratrol rescues heart dysfunction by reducing myocardial oxidative stress and myocardial fibrosis in murine models of secondary iron-overload and genetic hemochromatosis. Both its unique ability to activate the SIRT1-FOXO1 axis and key anti-oxidant properties likely contribute to this observed protective effect in IOC. Thus, the authors suggest that “resveratrol represents a clinically and economically feasible therapeutic intervention to reduce the global burden from iron-overload cardiomyopathy at early and chronic stages of iron-overload.” [22]

In addition, studies from the co-author Dr. Chattipakorn’s group have demonstrated the impact of concomitant iron chelation therapy on IOC in murine animal models, while a clinical trial is still ongoing. Animal studies were carried out in iron overloaded rats [137, 138] and iron overloaded thalassemic mice [65]. The results showed that although iron chelators (DFO, DFP, DFX) or antioxidants (N-acetyl cysteine, NAC) alone provide cardioprotection, the combined DFP plus NAC treatment exhibited greater efficacy than monotherapy as a result of a greater reduction in cardiac iron deposition and improved cardiac mitochondrial function.

Clinical studies have also been conducted to evaluate the effects of the combined therapy of idebenone (a synthetic analogue of the vital cell antioxidant Coenzyme Q10) and low oral doses of deferiprone (20 mg/kg/day) on Friedreich ataxia (FA). The results suggest that combined therapy of a low dose of deferiprone with idebenone is relatively safe and seems to improve both neurological function and heart hypertrophy parameters [27, 131].

It should be pointed out that many of the clinical trials testing the efficacy of antioxidants failed to show improved cardiovascular outcomes. One explanation could be that the antioxidants diminish ROS at baseline to levels below what’s needed for normal intracellular signaling purposes and response to injury, since the basal production of ROS is important for intracellular signaling [115]. As previously mentioned, vitamin C, a commonly studied antioxidant, may paradoxically promote ROS generation in the presence of metal ions. Therefore, caution should be taken when utilizing specific antioxidants to treat IOC.

Conclusions

Despite the reporting of the oxidative stress, Ca mishandling, and mitochondrial dysfunction as contributing to the pathogenesis of iron overload-mediated cardiomyopathy further in depth studies are needed. Future studies are required to 1) define the exact location of the oxidative stress (plasma vs. cytosolic vs. mitochondria) and to determine which is most critical for iron associated cardiac toxicity; 2) assess how mitochondrial Ca handling proteins (such as mPTP, mCU) are involved in cardiac toxicity caused by iron; 3) demonstrate the impact of calcium microdomains in the cytosol and mitochondria on cardiac toxicity induced by iron overload; 4) determine how other signaling systems (such as sympathetic nervous system stress) interact with iron overload in the development of arrhythmias; 5) conduct large clinical trials to validate the cardioprotective effect of Ca channel blockers combined with iron chelators. Future investigation on the molecular/cellular mechanism(s) including subcellular targets of iron toxicity in the heart will help develop a more targeted therapy for iron overload associated cardiac toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (R01s HL97979 and HL133294 to LHX), and American Heart Association (Grant-in-Aid to LHX), the National Science and Technology Development Agency Thailand (NSTDA Research Chair grant to NC), and the Thailand Research Fund (RTA6080003 to SCC and RGJ to SCC and SW).

References

- 1.Aguilar-Martinez P, Lok CY, Cunat S, Cadet E, Robson K, Rochette J. Juvenile hemochromatosis caused by a novel combination of hemojuvelin G320V/R176C mutations in a 5-year old girl. Haematologica. 2007;92:421–422. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen KJ, Gurrin LC, Constantine CC, Osborne NJ, Delatycki MB, Nicoll AJ, McLaren CE, Bahlo M, Nisselle AE, Vulpe CD, Anderson GJ, Southey MC, Giles GG, English DR, Hopper JL, Olynyk JK, Powell LW, Gertig DM. Iron-overload-related disease in HFE hereditary hemochromatosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:221–230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson LJ, Holden S, Davis B, Prescott E, Charrier CC, Bunce NH, Firmin DN, Wonke B, Porter J, Walker JM, Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. European heart journal. 2001;22:2171–2179. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartfay WJ, Bartfay E. Iron-overload cardiomyopathy: evidence for a free radical--mediated mechanism of injury and dysfunction in a murine model. Biological research for nursing. 2000;2:49–59. doi: 10.1177/109980040000200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartfay WJ, Butany J, Lehotay DC, Sole MJ, Hou D, Bartfay E, Liu PP. A biochemical, histochemical, and electron microscopic study on the effects of iron-loading on the hearts of mice. Cardiovascular pathology: the official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology. 1999;8:305–314. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(99)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayar N, Arslan S, Erkal Z, Kucukseymen S. Sustained ventricular tachycardia in a patient with thalassemia major. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology: the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2014;19:193–197. doi: 10.1111/anec.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekri S, Kispal G, Lange H, Fitzsimons E, Tolmie J, Lill R, Bishop DF. Human ABC7 transporter: gene structure and mutation causing X-linked sideroblastic anemia with ataxia with disruption of cytosolic iron-sulfur protein maturation. Blood. 2000;96:3256–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berdoukas V, Chouliaras G, Moraitis P, Zannikos K, Berdoussi E, Ladis V. The efficacy of iron chelator regimes in reducing cardiac and hepatic iron in patients with thalassaemia major: a clinical observational study. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance: official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2009;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1532-429x-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berdoukas V, Coates TD, Cabantchik ZI. Iron and oxidative stress in cardiomyopathy in thalassemia. Free radical biology & medicine. 2015;88:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brissot P, Ropert M, Le Lan C, Loreal O. Non-transferrin bound iron: a key role in iron overload and iron toxicity. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1820:403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho FS, Burgeiro A, Garcia R, Moreno AJ, Carvalho RA, Oliveira PJ. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: from bioenergetic failure and cell death to cardiomyopathy. Medicinal research reviews. 2014;34:106–135. doi: 10.1002/med.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassinerio E, Roghi A, Orofino N, Pedrotti P, Zanaboni L, Poggiali E, Giuditta M, Consonni D, Cappellini MD. A 5-year follow-up in deferasirox treatment: improvement of cardiac and hepatic iron overload and amelioration in cardiac function in thalassemia major patients. Annals of hematology. 2015;94:939–945. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavadini P, Biasiotto G, Poli M, Levi S, Verardi R, Zanella I, Derosas M, Ingrassia R, Corrado M, Arosio P. RNA silencing of the mitochondrial ABCB7 transporter in HeLa cells causes an iron-deficient phenotype with mitochondrial iron overload. Blood. 2007;109:3552–3559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavallaro L, Meo A, Busa G, Coglitore A, Sergi G, Satullo G, Donato A, Calabro MP, Miceli M. Arrhythmia in thalassemia major: evaluation of iron chelating therapy by dynamic ECG. Minerva cardioangiologica. 1993;41:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang HC, Shapiro JS, Ardehali H. Getting to the “Heart” of Cardiac Disease by Decreasing Mitochondrial Iron. Circulation research. 2016;119:1164–1166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang HC, Wu R, Shang M, Sato T, Chen C, Shapiro JS, Liu T, Thakur A, Sawicki KT, Prasad SV, Ardehali H. Reduction in mitochondrial iron alleviates cardiac damage during injury. EMBO molecular medicine. 2016;8:247–267. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Q, Espey MG, Sun AY, Lee JH, Krishna MC, Shacter E, Choyke PL, Pooput C, Kirk KL, Buettner GR, Levine M. Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:8749–8754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiamvimonvat N, O’Rourke B, Kamp TJ, Kallen RG, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Marban E. Functional consequences of sulfhydryl modification in the pore-forming subunits of cardiovascular Ca2+ and Na+ channels. Circulation research. 1995;76:325–334. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang S, Kovacevic Z, Sahni S, Lane DJ, Merlot AM, Kalinowski DS, Huang ML, Richardson DR. Frataxin and the molecular mechanism of mitochondrial iron-loading in Friedreich’s ataxia. Clinical science. 2016;130:853–870. doi: 10.1042/CS20160072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowe S, Bartfay WJ. Amlodipine decreases iron uptake and oxygen free radical production in the heart of chronically iron overloaded mice. Biological research for nursing. 2002;3:189–197. doi: 10.1177/109980040200300404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das SK, Patel VB, Basu R, Wang W, DesAulniers J, Kassiri Z, Oudit GY. Females Are Protected From Iron-Overload Cardiomyopathy Independent of Iron Metabolism: Key Role of Oxidative Stress. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017:6. doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.003456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das SK, Wang W, Zhabyeyev P, Basu R, McLean B, Fan D, Parajuli N, DesAulniers J, Patel VB, Hajjar RJ, Dyck JR, Kassiri Z, Oudit GY. Iron-overload injury and cardiomyopathy in acquired and genetic models is attenuated by resveratrol therapy. Scientific reports. 2015;5:18132. doi: 10.1038/srep18132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis MT, Bartfay WJ. Dose-dependent effects of chronic iron burden on heart aldehyde and acyloin production in mice. Biological trace element research. 2004;99:255–268. doi: 10.1385/bter:99:1-3:255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis MT, Bartfay WJ. Ebselen decreases oxygen free radical production and iron concentrations in the hearts of chronically iron-overloaded mice. Biological research for nursing. 2004;6:37–45. doi: 10.1177/1099800403261350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delea TE, Edelsberg J, Sofrygin O, Thomas SK, Baladi JF, Phatak PD, Coates TD. Consequences and costs of noncompliance with iron chelation therapy in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia: a literature review. Transfusion. 2007;47:1919–1929. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demougeot C, Van Hoecke M, Bertrand N, Prigent-Tessier A, Mossiat C, Beley A, Marie C. Cytoprotective efficacy and mechanisms of the liposoluble iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl in the rat photothrombotic ischemic stroke model. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2004;311:1080–1087. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.072744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elincx-Benizri S, Glik A, Merkel D, Arad M, Freimark D, Kozlova E, Cabantchik I, Hassin-Baer S. Clinical Experience With Deferiprone Treatment for Friedreich Ataxia. Journal of child neurology. 2016;31:1036–1040. doi: 10.1177/0883073816636087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandes JL, Sampaio EF, Fertrin K, Coelho OR, Loggetto S, Piga A, Verissimo M, Saad ST. Amlodipine reduces cardiac iron overload in patients with thalassemia major: a pilot trial. The American journal of medicine. 2013;126:834–837. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gammella E, Maccarinelli F, Buratti P, Recalcati S, Cairo G. The role of iron in anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2014;5:25. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao X, Campian JL, Qian M, Sun XF, Eaton JW. Mitochondrial DNA damage in iron overload. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:4767–4775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806235200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glickstein H, El RB, Link G, Breuer W, Konijn AM, Hershko C, Nick H, Cabantchik ZI. Action of chelators in iron-loaded cardiac cells: Accessibility to intracellular labile iron and functional consequences. Blood. 2006;108:3195–3203. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glickstein H, El RB, Shvartsman M, Cabantchik ZI. Intracellular labile iron pools as direct targets of iron chelators: a fluorescence study of chelator action in living cells. Blood. 2005;106:3242–3250. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerra L, Cerbai E, Gessi S, Borea PA, Mugelli A. The effect of oxygen free radicals on calcium current and dihydropyridine binding sites in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. British journal of pharmacology. 1996;118:1278–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamed AA, Elguindy W, Elhenawy YI, Ibrahim RH. Early Cardiac Involvement and Risk Factors for the Development of Arrhythmia in Patients With beta-Thalassemia Major. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2016;38:5–11. doi: 10.1097/mph.0000000000000467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasinoff BB, Patel D, Wu X. The oral iron chelator ICL670A (deferasirox) does not protect myocytes against doxorubicin. Free radical biology & medicine. 2003;35:1469–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heper G, Ozensoy U, Korkmaz ME. Persistent atrial standstill and idioventricular rhythm in a patient with thalassemia intermedia. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi arsivi: Turk Kardiyoloji Derneginin yayin organidir. 2009;37:256–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hershko C. Oral iron chelators: new opportunities and new dilemmas. Haematologica. 2006;91:1307–1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershko C. Pathogenesis and management of iron toxicity in thalassemia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1202:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hider RC, Silva AM, Podinovskaia M, Ma Y. Monitoring the efficiency of iron chelation therapy: the potential of nontransferrin-bound iron. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1202:94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffbrand AV, Taher A, Cappellini MD. How I treat transfusional iron overload. Blood. 2012;120:3657–3669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-370098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang FW, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Fleming MD, Andrews NC. A mouse model of juvenile hemochromatosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:2187–2191. doi: 10.1172/jci25049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichikawa Y, Bayeva M, Ghanefar M, Potini V, Sun L, Mutharasan RK, Wu R, Khechaduri A, Jairaj Naik T, Ardehali H. Disruption of ATP-binding cassette B8 in mice leads to cardiomyopathy through a decrease in mitochondrial iron export. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:4152–4157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119338109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ichikawa Y, Ghanefar M, Bayeva M, Wu R, Khechaduri A, Naga Prasad SV, Mutharasan RK, Naik TJ, Ardehali H. Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is mediated through mitochondrial iron accumulation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:617–630. doi: 10.1172/jci72931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Isma’eel H, Shamseddeen W, Taher A, Gharzuddine W, Dimassi A, Alam S, Masri L, Khoury M. Ventricular late potentials among thalassemia patients. International journal of cardiology. 2009;132:453–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Italia K, Colah R, Ghosh K. Experimental animal model to study iron overload and iron chelation and review of other such models. Blood cells, molecules & diseases. 2015;55:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito S, Ikuta K, Kato D, Lynda A, Shibusa K, Niizeki N, Toki Y, Hatayama M, Yamamoto M, Shindo M, Iizuka N, Kohgo Y, Fujiya M. In vivo behavior of NTBI revealed by automated quantification system. International journal of hematology. 2016;104:175–181. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-2002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackson LH, Vlachodimitropoulou E, Shangaris P, Roberts TA, Ryan TM, Campbell-Washburn AE, David AL, Porter JB, Lythgoe MF, Stuckey DJ. Non-invasive MRI biomarkers for the early assessment of iron overload in a humanized mouse model of beta-thalassemia. Scientific reports. 2017;7:43439. doi: 10.1038/srep43439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaiser L, Davis J, Patterson J, Boyd RF, Olivier NB, Bohart G, Schwartz KA. Iron does not cause arrhythmias in the guinea pig model of transfusional iron overload. Comparative medicine. 2007;57:383–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaiser L, Davis JM, Schwartz KA. Does the gerbil model mimic human iron overload? The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2003;141:419–420. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(03)00038-6. author reply 420–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapsokefalou M, Miller DD. Iron loading and large doses of intravenous ascorbic acid promote lipid peroxidation in whole serum in guinea pigs. The British journal of nutrition. 2001;85:681–687. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kc S, Carcamo JM, Golde DW. Vitamin C enters mitochondria via facilitative glucose transporter 1 (Glut1) and confers mitochondrial protection against oxidative injury. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2005;19:1657–1667. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4107com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ke Y, Chen YY, Chang YZ, Duan XL, Ho KP, Jiang DH, Wang K, Qian ZM. Post-transcriptional expression of DMT1 in the heart of rat. Journal of cellular physiology. 2003;196:124–130. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keizer HG, Pinedo HM, Schuurhuis GJ, Joenje H. Doxorubicin (adriamycin): a critical review of free radical-dependent mechanisms of cytotoxicity. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 1990;47:219–231. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90088-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khamseekaew J, Kumfu S, Wongjaikam S, Kerdphoo S, Jaiwongkam T, Srichairatanakool S, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Effects of iron overload, an iron chelator and a T-Type calcium channel blocker on cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial dynamics in thalassemic mice. European journal of pharmacology. 2017;799:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim E, Giri SN, Pessah IN. Iron(II) is a modulator of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels of cardiac muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 1995;130:57–66. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koppenol WH. The Haber-Weiss cycle--70 years later. Redox report: communications in free radical research. 2001;6:229–234. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kremastinos DT, Farmakis D. Iron overload cardiomyopathy in clinical practice. Circulation. 2011;124:2253–2263. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.111.050773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kruszewski M. Labile iron pool: the main determinant of cellular response to oxidative stress. Mutation research. 2003;531:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumfu S, Chattipakorn S, Chinda K, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn N. T-type calcium channel blockade improves survival and cardiovascular function in thalassemic mice. European journal of haematology. 2012;88:535–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumfu S, Chattipakorn S, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn N. Ferric iron uptake into cardiomyocytes of beta-thalassemic mice is not through calcium channels. Drug and chemical toxicology. 2013;36:329–334. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2012.726625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumfu S, Chattipakorn S, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn N. Mitochondrial calcium uniporter blocker prevents cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction induced by iron overload in thalassemic mice. Biometals: an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine. 2012;25:1167–1175. doi: 10.1007/s10534-012-9579-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumfu S, Chattipakorn S, Srichairatanakool S, Settakorn J, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn N. T-type calcium channel as a portal of iron uptake into cardiomyocytes of beta-thalassemic mice. European journal of haematology. 2011;86:156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumfu S, Chattipakorn SC, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn N. Dual T-type and L-type calcium channel blocker exerts beneficial effects in attenuating cardiovascular dysfunction in iron-overloaded thalassaemic mice. Experimental physiology. 2016;101:521–539. doi: 10.1113/ep085517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumfu S, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Cardiac complications in beta-thalassemia: From mice to men. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, NJ) 2017;242:1126–1135. doi: 10.1177/1535370217708977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumfu S, Khamseekaew J, Palee S, Srichairatanakool S, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. A combination of an iron chelator with an antioxidant exerts greater efficacy on cardioprotection than monotherapy in iron-overload thalassemic mice. Free radical research. 2018;52:70–79. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2017.1414208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ladis V, Chouliaras G, Berdousi H, Kanavakis E, Kattamis C. Longitudinal study of survival and causes of death in patients with thalassemia major in Greece. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1054:445–450. doi: 10.1196/annals.1345.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lakhal-Littleton S, Wolna M, Carr CA, Miller JJ, Christian HC, Ball V, Santos A, Diaz R, Biggs D, Stillion R, Holdship P, Larner F, Tyler DJ, Clarke K, Davies B, Robbins PA. Cardiac ferroportin regulates cellular iron homeostasis and is important for cardiac function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:3164–3169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422373112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lakhal-Littleton S, Wolna M, Chung YJ, Christian HC, Heather LC, Brescia M, Ball V, Diaz R, Santos A, Biggs D, Clarke K, Davies B, Robbins PA. An essential cell-autonomous role for hepcidin in cardiac iron homeostasis. eLife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laurita KR, Chuck ET, Yang T, Dong WQ, Kuryshev YA, Brittenham GM, Rosenbaum DS, Brown AM. Optical mapping reveals conduction slowing and impulse block in iron-overload cardiomyopathy. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2003;142:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(03)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu JP, Hayashi K. Transferrin receptor distribution and iron deposition in the hepatic lobule of iron-overloaded rats. Pathology international. 1995;45:202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ludke AR, Sharma AK, Akolkar G, Bajpai G, Singal PK. Downregulation of vitamin C transporter SVCT-2 in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte injury. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2012;303:C645–653. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00186.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mancuso L, Mancuso A, Bevacqua E, Rigano P. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in thalassemia patients with heart failure. Cardiovascular & hematological disorders drug targets. 2009;9:29–35. doi: 10.2174/187152909787581345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marques VB, Nascimento TB, Ribeiro RF, Jr, Broseghini-Filho GB, Rossi EM, Graceli JB, dos Santos L. Chronic iron overload in rats increases vascular reactivity by increasing oxidative stress and reducing nitric oxide bioavailability. Life sciences. 2015;143:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marx JJ. Pathophysiology and treatment of iron overload in thalassemia patients in tropical countries. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2003;531:57–68. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0059-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McNamara L, Gordeuk VR, MacPhail AP. Ferroportin (Q248H) mutations in African families with dietary iron overload. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2005;20:1855–1858. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Minotti G, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Cairo G, Gianni L. Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacological reviews. 2004;56:185–229. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moon SN, Han JW, Hwang HS, Kim MJ, Lee SJ, Lee JY, Oh CK, Jeong DC. Establishment of secondary iron overloaded mouse model: evaluation of cardiac function and analysis according to iron concentration. Pediatric cardiology. 2011;32:947–952. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-0019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nieminen AL, Schwartz J, Hung HI, Blocker ER, Gooz M, Lemasters JJ. Mitoferrin-2 (MFRN2) Regulates the Electrogenic Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter and Interacts Physically with MCU. Biophys J. 2014;106:581a. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nisli K, Taner Y, Naci O, Zafer S, Zeynep K, Aygun D, Umrah A, Rukiye E, Turkan E. Electrocardiographic markers for the early detection of cardiac disease in patients with beta-thalassemia major. Jornal de pediatria. 2010;86:159–162. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Obejero-Paz CA, Yang T, Dong WQ, Levy MN, Brittenham GM, Kuryshev YA, Brown AM. Deferoxamine promotes survival and prevents electrocardiographic abnormalities in the gerbil model of iron-overload cardiomyopathy. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2003;141:121–130. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2003.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oduor H, Minniti CP, Brofferio A, Gharib AM, Abd-Elmoniem KZ, Hsieh MM, Tisdale JF, Fitzhugh CD. Severe cardiac iron toxicity in two adults with sickle cell disease. Transfusion. 2017;57:700–704. doi: 10.1111/trf.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]