Abstract

Transposable elements are emerging as an important source of cis-acting regulatory sequences and epigenetic marks that could influence gene expression. However, few studies have dissected the role of specific transposable element insertions on epigenetic gene regulation. Bari-Jheh is a natural transposon that mediates resistance to oxidative stress by adding cis-regulatory sequences that affect expression of nearby genes. In this work, we integrated publicly available ChIP-seq and piRNA data with chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments to get a more comprehensive picture of Bari-Jheh molecular effects. We showed that Bari-Jheh was enriched for H3K9me3 in nonstress conditions, and for H3K9me3, H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 in oxidative stress conditions, which is consistent with expression changes in adjacent genes. We further showed that under oxidative stress conditions, H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 spread to the promoter region of Jheh1 gene. Finally, another insertion of the Bari1 family was associated with increased H3K27me3 in oxidative stress conditions suggesting that Bari1 histone marks are copy-specific. We concluded that besides adding cis-regulatory sequences, Bari-Jheh influences gene expression by affecting the local chromatin state.

Introduction

Gene regulation is a complex process that involves mechanisms at the DNA sequence level and at the epigenetic level. Although genes can acquire novel regulatory mechanisms through different types of mutations, transposable elements (TEs) are emerging as an important source of regulatory variation1,2. TEs can contain cis-regulatory sequences that affect the expression of nearby genes. Some of the recent examples on the global impact of TEs on gene expression levels include: providing enhancer sequences that contribute to the stress-induced gene activation in maize, adding transcription factor binding sites in the mouse and the human genomes, and providing alternative transcription start sites in Drosophila3–5. The epigenetic status of TEs can also affect gene regulation. In Arabidopsis thaliana, gene transcription is affected by the methylation status of intragenic TEs6 and correlates with siRNA-targeting of TEs7. In Drosophila, local spreading of repressive heterochromatin marks from TEs has been associated with gene down-regulation8,9. Although all these studies strongly suggest that TEs may play a role in gene regulation through different molecular mechanisms, detailed analyses that link changes in expression with fitness effects are needed to conclude that TEs have a functional impact on gene expression.

There are a few examples in which TE-induced changes in gene expression have been shown to be functionally relevant10–12. One of these cases is Bari-Jheh, a Drosophila melanogaster full-length transposon providing a cis-regulatory sequence that affects the expression of its nearby genes13,14. Bari-Jheh is associated with downregulation of Juvenile hormone epoxy hydrolase 2 (Jheh2) and Jheh3 in nonstress conditions, and with upregulation of Jheh1 and Jheh2 and downregulation of Jheh3 under oxidative stress conditions12. We have previously shown that Bari-Jheh adds Antioxidant Response Elements to the upstream region of Jheh2 leading to Jheh2 and Jheh1 upregulation under oxidative stress conditions12,15. However, how Bari-Jheh affects gene expression under nonstress conditions, and how Bari-Jheh affects Jheh3 expression under oxidative stress conditions remains unexplored. In this work, we hypothesized that Bari-Jheh could also be affecting the expression of nearby genes by remodeling the local chromatin state. Thus, we tested whether Bari-Jheh is associated with H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and/or H3K27me3 histone marks, and whether stress affects this association. While histone modifications were at first thought to be stable modifications, it is now emerging that changes in histone modifications are a key regulation in response to various stresses16–18. Finally, we also investigated whether stress affects the association of another transposon, which also belongs to the Bari1 family, with the same histone marks.

Methods

Prediction of Polycomb Response Elements (PREs) and Trithorax Response Elements (TREs)

We used the database JASPAR19 with 95% threshold to predict the presence of PREs/TREs in the genomic region containing Bari-Jheh insertion and the three Jheh genes20. To identify PREs and TREs we used JASPAR matrix MA0255.1 and MA0205.1, respectively.

Detection of piRNA reads

To search for piRNA homology sites in Bari-Jheh, we used the method described in Sentmanat and Elgin8 and Ullastres et al.21. Briefly, reads were obtained from available piRNA libraries22,23. Direct-sequence mapping was carried out using BWA-MEM package version 0.7.5 a-r405 with default parameters to the 5.2 kb sequence including the Bari-Jheh element (chromosome 2R: 18,856,800–18,861,999)24. Then, we indexed and filtered sense/antisense reads by using samtools and bamtools25. The total density of the reads was obtained using R (Rstudio v0.98.507).

Detection of HP1a binding sites

To analyze the binding sites for HP1a in the Bari-Jheh region, we used HP1a modENCODE ChIP-Seq data26, and we followed the methodology described above for mapping the reads to the Bari-Jheh region. Note that the reads used to identify the HP1a binding sites were normalized by the input.

Fly stocks

We used the pair of outbred populations described in Guio et al.12 (DGRP #1), and a new pair of outbred populations created for this work (DGRP #2, Supplementary Table S1). Briefly, 10 virgin females and 10 males of seven strains homozygous for the presence of Bari-Jheh were placed in a large embryo collection chamber. The progeny was randomly mated during 10 generations before performing experiments. The same procedure was repeated for flies homozygous for the absence of Bari-Jheh. All the strains used to construct the outbred populations came from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel project27,28. Flies were kept in large embryo collection chambers with regular fly food (yeast, glucose and wheat flour). Briefly, ~200 mated females laid eggs during 24 hours. After that, the plates with eggs were placed in a new collection chamber and stored at 21–24 °C until adult emergence. We selected adults emerged in a 24 hour interval and we placed them in a new chamber. After 48 hours, we split groups of 50 females with CO2 pads and stored flies in tubes with fly food at 21–24 °C until experiments were performed.

Oxidative stress exposure

To induce oxidative stress, we added paraquat to the fly food up to a final concentration of 10 mM. For nonstress conditions, we used regular fly food. We transferred the flies to new tubes with or without paraquat and exposed them during 12 hours at 21–24 °C before dissection. We did three to four biological replicas, of 50 females each, for each condition and genotype.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP assays were performed with flies from two different genetic backgrounds. Three to four biological replicas of 50 flies each per background were analyzed. We performed ChIP assays in guts because the gut is the first barrier against oxidative stress29. Guts of 5-day-old females were dissected in 1× PBS with protease inhibitor cocktail. After dissection, we homogenized the samples in Buffer A1 (HEPES 15 mM, Sodium Butyrate 10 mM, KCl 60 mM, Triton ×100 0,5%, NaCl 15 mM) with a dounce tissue grinder (30 times). We crosslinked the guts with 1.8% formaldehyde during 10 minutes at room temperature. We stopped the crosslink adding glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM. We incubated the samples 3 minutes and kept the samples on ice. We washed the samples 3 times with Buffer A1 and then we add 0.2 ml of lysis buffer (HEPES 15 mM, EDTA 1 mM, EGTA 0.5 mM, Sodium Butyrate 10 mM, SDS 0.5%, Sodium deoxycholate 0.1%, N-Lauroylsarcosine 0.5%, Triton x100 1%, and NaCl 140 mM) and incubate 3 hours at 4 °C. After lysis, we sonicated the samples using Biorruptor® pico sonication device from Diagenode: 15 cycles of 30 seconds ON, 30 seconds OFF. We used the Magna ChIP G chromatin immunoprecipation Kit (Millipore). All the buffers and reagents used were provided by the Kit. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibodies against H3K4me3 (Catalog # ab8580), H3K9me3 (#ab8898), and H3K27me3 (#ab6002). All the antibodies were ChIP grade and antibody quality was tested before performing the experiments (Supplementary Figure 1). We separated 20 µl for input and store it at −20 °C. The remaining 180 µl were divided in three aliquots and we added 1 µl of each antibody plus 20 µl of magnetic beads and dilution buffer up to 530 µl. We incubated the samples overnight at 4 °C in an agitation wheel. After incubation we washed the beads with Low salt buffer, High salt buffer, LiCl complex buffer, and TE buffer. We separated the chromatin from the beads using 0.5 ml of elution buffer, including input samples. We added 1 µl of Proteinase K to each sample and incubated the samples at 65 °C overnight in a shaker at 300 rpm. After incubation, we purified the samples using the columns provided by the kit. We stored the samples at −20 °C until the q-PCR analyses were performed.

q-PCR analysis

We quantified the IP enrichment by q-PCR normalizing the data using the “input” of each IP as the reference value, using the ΔCt method. As we mentioned above, we performed three to four biological replicates. For each biological replicate, three technical replicates were performed. Primers used for this study are described in Table S2. We first confirmed the quality of the antibodies and the specificity of the immunoprecipitation. We analyzed the enrichment of each histone mark in a well-known genomic region enriched for the different histone marks studied: RpL32 (also known as rp49), 18SrRNA (also known as 18S), and Ubx enriched for H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K27me3 respectively. We also tested whether the stress affects the histone marks enrichment in these three genes. We note that in a previous version of this work, we did not test whether stress affected the enrichment of histone marks in a well-known genomic region enriched for these marks30. When we did this analysis, we found that stress did affect the enrichment on these genes suggesting that there were technical problems in the immunoprecipitation. We thus discarded these previous results.

Statistical analysis

We used R software with the dunn.test package for the analyses. Results were not normally distributed. Different data transformation failed to normalize the data. Thus, we used a non-parametric test Kruskal-Wallis. Since we performed several tests we corrected the p-value for each set of tests using Bonferroni correction. We also tested whether results obtained with the two genetic backgrounds analyzed were significantly different before pooling them.

Results

Bari-Jheh could be affecting the local chromatin state

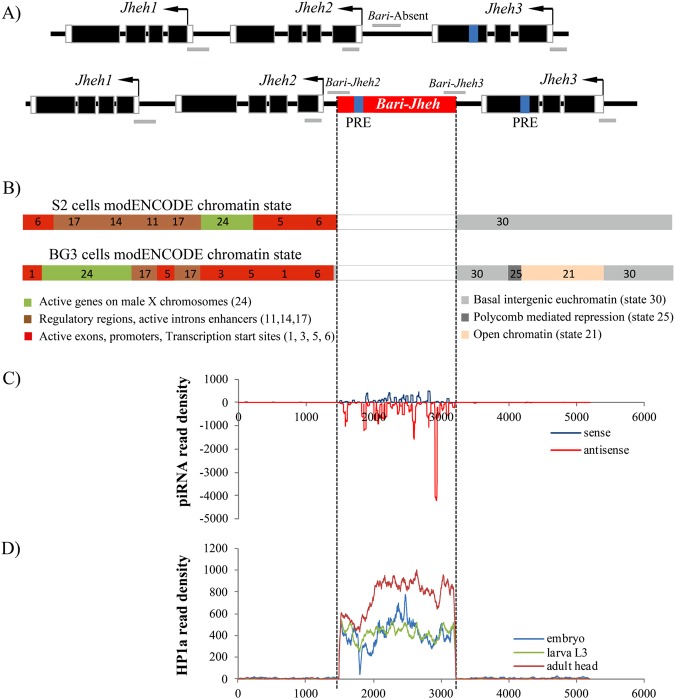

To test whether Bari-Jheh could be affecting the local chromatin state, we analyzed the sequence of the transposon and its flanking regions including the three Jheh genes (Fig. 1). We first looked for Trithorax group Response Elements (TREs) that recruit H3K4 methyltransferases, and Polycomb group Response Elements (PREs) that recruit H3K27 methyltransferases (see Methods31,32). While H3K4me3 is associated with active promoters, H3K27me3 is associated with silenced or repressed promoters and enhancers33. We found no TREs in the sequence analyzed, but we found one PRE in the Bari-Jheh sequence, and one PRE in the coding region of Jheh3. Note that modENCODE reports a Polycomb mediated repressive chromatin state in the same Jheh3 exon in BG3 cells (Fig. 1A,B)34.

Figure 1.

Bari-Jheh could be adding heterochromatin marks to the Jheh intergenic region. (A) Schematic representation of Jheh genes in flies without Bari-Jheh and flies with Bari-Jheh. Black boxes represent exons, black arrows represent the direction of transcription, white boxes the 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR regions, the black line indicates intergenic or intronic regions and the red box represents Bari-Jheh. Grey lines represent the amplicons of the five regions analyzed using ChIP-qPCR experiments. The blue bars indicate the approximated position of the predicted PREs. (B) modENCODE chromatin states in S2 cells and BG3 cells in the region analyzed. S2 cells and BG3 cells are derived from late male embryonic tissues and the central nervous system of male third instar larvae, respectively (The modENCODE consortium et al. 2010). Colors and numbers represent different chromatin states. The vertical discontinuous lines indicate the location of Bari-Jheh insertion, which was not analyzed by modENCODE. (C) Mapping of piRNA reads in the Bari-Jheh and flanking regions. Reads mapping in sense orientation are represented in blue, and reads mapping in antisense orientation in red. (D) Mapping of HP1a reads in the Bari-Jheh and flanking regions. Reads from embryo stage are represented in blue, reads from larva L3 stage in green, and reads from adult head in red.

To further test whether Bari-Jheh affects the local heterochromatin state, we also investigated whether Bari-Jheh has piRNA binding sites and/or recruits HP1a (see Methods). Sites with homology to piRNAs behave as cis-acting targets for heterochromatin assembly, which is associated with HP1a and H3K9me2/38. H3K9me2/3 typically labels transcriptionally silent heterochromatic regions8. We found that Bari-Jheh has sites with homology to piRNAs (Fig. 1C). Accordingly, we also found that HP1a specifically binds to the Bari-Jheh sequence (Fig. 1D).

Thus, Bari-Jheh could be introducing PREs that would be involved in the recruitment of H3K27me3 methyltransferase enzymes. Additionally, Bari-Jheh could also be inducing piRNA mediated heterochromatin assembly, and thus could be adding H3K9me2/3. These results provide suggestive but not conclusive evidence that Bari-Jheh could be introducing heterochromatin histone marks.

Bari-Jheh is associated with an enrichment of H3K9me3 histone mark in nonstress conditions

To experimentally test whether Bari-Jheh affects histone marks enrichment, we performed ChIP-q-PCR experiments in guts of adult flies with antibodies anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K9me3, and anti-H3K27me3. We first tested the quality of the immunoprecipitation using genes previously reported to be enriched for the three histone marks analyzed (Figure S1, Table S3). We performed these analyses in flies with and without Bari-Jheh from two different genetic backgrounds, in nonstress and in stress conditions. As expected, we found significant enrichment of H3K9me3 for 18SrRNA35, significant enrichment of H3K4me3 for RpL3236, and significant enrichment of H3K27me3 for Ubx37 (Figure S1, Table S3). Note that 18SrRNA is also enriched for H3K27me3. We did not find significant differences between strains with and without Bari-Jheh, or between nonstress and stress conditions (Figure S1, Table S3). Thus, we conclude that the immunoprecipitations were specific.

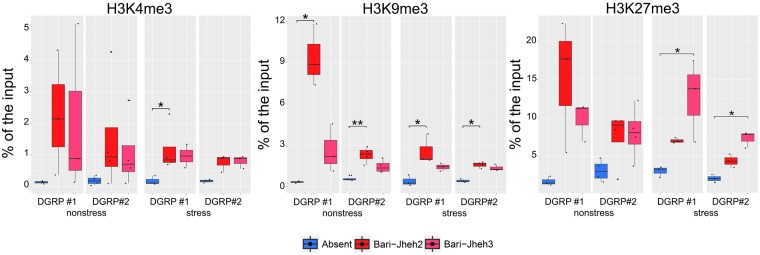

We compared the histone mark enrichment on both sides of Bari-Jheh insertion, Bari-Jheh2 and Bari-Jheh3 regions, with the corresponding region in flies without Bari-Jheh, Bari-Absent region (Fig. 1). In nonstress conditions, we found significant differences in H3K9me3 in the Bari-Jheh2 region compared with the Bari-Absent region in the two backgrounds analyzed (Fig. 2, Table 1). Thus, Bari-Jheh is associated with H3K9me3 enrichemnt in the Jheh intergenic region in nonstress conditions (Fig. 2, Table 1). Although we did not find an enrichment of H3K27me3 as expected from the presence of PRE elements in Bari-Jheh, our results are consistent with the presence of piRNA homology sites and HP1a in Bari-Jheh sequence (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Histone mark enrichment in Bari-absent, Bari-Jheh2 and Bari-Jheh3 regions. Histone mark enrichment relative to the input of each strain for each background under nonstress and stress conditions. Each panel represents a different histone mark, H3K4me3, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 in the Bari-absent (blue), Bari-Jheh2 (light red) and Bari-Jheh3 (red) analyzed regions. Significant differences between regions are mark with one (p-value < 0.05) or two (p-value < 0,01) asterisks.

Table 1.

Statistical analyses of histone mark enrichment in the Bari-Jheh region.

| Histone | Treatment | Genetic Background | Comparison | K-W test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.1105 |

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.2696 | |||

| DGRP #2 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.175 | ||

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.2547 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.0256 | |

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.1516 | |||

| DGRP #2 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.0553 | ||

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.0789 | |||

| H3K9me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.0109 |

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.2696 | |||

| DGRP #2 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.0049 | ||

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.116 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.0109 | |

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.2696 | |||

| DGRP #2 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.0169 | ||

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.2041 | |||

| H3K27me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.038 |

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.115 | |||

| DGRP #2 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.143 | ||

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.0937 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.2696 | |

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.0109 | |||

| DGRP #2 | Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh2 | 0.2696 | ||

| Bari-Abs – Bari-Jheh3 | 0.0109 |

Significant values after Bonferroni correction are highlighted in bold.

Bari-Jheh is also associated with an enrichment for H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 chromatin marks in oxidative stress conditions

To further test whether oxidative stress affects the chromatin marks added by Bari-Jheh, we performed ChIP-qPCR experiments in guts of adult flies exposed to paraquat. We found significant differences for H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 between flies with and without Bari-Jheh, in the Bari-Jheh2 region in at least one of the backgrounds analyzed (Fig. 2, Table 1). We also found differences for H3K27me3 in the Bari-Jheh3 region in the two backgrounds analyzed. Overall these results showed that in oxidative stress conditions, Bari-Jheh is associated with an enrichment of H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K27me3 histone marks.

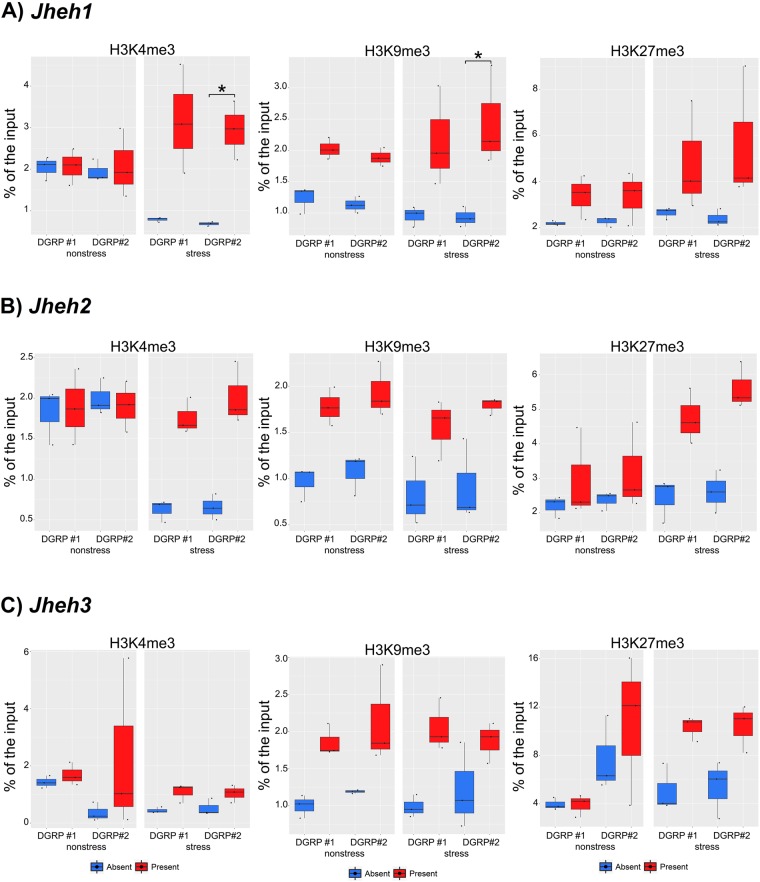

Bari-Jheh did not affect histone marks enrichment on the nearby genes in nonstress conditions

Previous studies showed that spread of H3K9me3 histone mark to nearby DNA occurs at ≥50% of euchromatic TEs and can extend up to 20 kb (average of 4.5 kb)38. Because we found that Bari-Jheh adds H3K9me3 in nonstress conditions, we tested whether there was also an enrichment of H3K9me3 in the promoter regions of the three genes nearby Bari-Jheh (Fig. 1). In nonstress conditions, we found no significant enrichment for H3K9me3 in any of the three nearby genes Jheh1, Jheh2 nor Jheh3 (Fig. 3, Table 2). There were no differences either in the enrichment of H3K4me3 or H3K27me3 in the promoter regions of these three genes (Fig. 3, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Histone mark enrichment in Jheh1, Jheh2 and Jheh3 gene up-stream regions. Enrichment of the histone marks relative to the input of each strain for each background under nonstress and stress conditions. Each panel represent a different histone mark, H3K4me3, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 for (A) Jheh1, (B) Jheh2 and (C) Jheh3 in the Bari-absent (blue) and Bari-present (light red) analyzed strains. Significant differences between regions are mark with an asterisk (p-value < 0.05).

Table 2.

Statistical analyses of histone mark enrichment in the Jheh genes. Significant values after Bonferroni correction are highlighted in bold.

| Histone | Treatment | Genetic Background | Gene region | Comparison | K-W test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh1 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh1 | Abs – Pres | 0.0276 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.019 | |||

| H3K9me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh1 | Abs – Pres | 0.2101 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.5227 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh1 | Abs – Pres | 0.0706 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.0197 | |||

| H3K27me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh1 | Abs – Pres | 0.0944 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.9245 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh1 | Abs – Pres | 0.4231 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.1627 | |||

| H3K4me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh2 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh2 | Abs – Pres | 0.1627 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.1246 | |||

| H3K9me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh2 | Abs – Pres | 0.1246 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.1246 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh2 | Abs – Pres | 0.0706 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.1246 | |||

| H3K27me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh2 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh2 | Abs – Pres | 0.2101 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.1246 | |||

| H3K4me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh3 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.5277 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh3 | Abs – Pres | 0.638 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.7726 | |||

| H3K9me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh3 | Abs – Pres | 0.2101 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.2683 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh3 | Abs – Pres | 0.0706 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.2683 | |||

| H3K27me3 | Nonstress | DGRP #1 | Jheh3 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 1.00 | |||

| Stress | DGRP #1 | Jheh3 | Abs – Pres | 0.2683 | |

| DGRP #2 | Abs – Pres | 0.3388 |

Bari-Jheh is associated with H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 enrichment in Jheh1 in oxidative stress conditions

We also tested whether we could detect a spread of H3K4me3, H3K9me3, or H3K27me3 to nearby DNA regions under oxidative stress conditions. We found that the promoter region of Jheh1 showed enrichment for histone marks H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 in one of the backgrounds analyzed in strains with Bari-Jheh compared with strains without Bari-Jheh (Fig. 3, Table 2). On the other hand, no enrichment of H3K27me3 was detected in the regions nearby Bari-Jheh in any of the three genes analyzed (Fig. 3, Table 2). Thus, under oxidative stress conditions, we found enrichment of H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 in the promoter region of Jheh1.

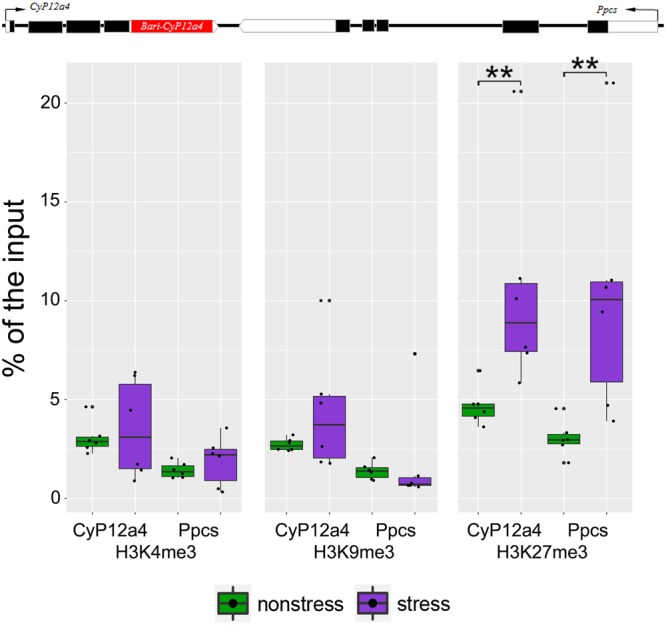

Bari1-Cyp12a4 is enriched for H3K27me3 under oxidative stress conditions

We wanted to test whether other full-length insertions belonging to the Bari1 family were associated with enrichment of histone marks. Besides Bari-Jheh, there are four full-length insertions located in the euchromatic region of the D. melanogaster genome. However, FBti0019099 and FBti0019419 were not present in the DGRP strains, and FBti0019499 is flanked by other TE insertions, which precludes analyzing its presence/absence status. Only FBti0019400 is fixed in the DGRP strains and thus we could study whether this copy was enriched for histone marks. FBti0019400 is inserted in the 3′ UTR region of the cytochrome P450 gene Cyp12a4 (Fig. 4). The presence of Bari1-Cyp12a4 (FBti0019400) insertion is associated with a shorter transcript and increased Cyp12a4 expression39. Because all the strains in our two pairs of outbred populations contain the Bari1-Cyp12a4 insertion, we tested whether Bari1-Cyp12a4 insertion showed different histone mark enrichment in nonstress vs stress conditions (Fig. 4, Table 3). We did not find differences in the enrichment levels between the two backgrounds analyzed. Thus, we pooled the data from the two backgrounds. We found an enrichment of H3K27me3 when comparing nonstress vs oxidative stress conditions (Fig. 4, Table 3). Thus, we showed that Bari1-Cyp12a4, which also belongs to the Bari1 TE family, showed an enrichment of H3K27me3 under oxidative stress conditions.

Figure 4.

Histone mark enrichment in Bari1-Cyp12a4 and Bari1-Ppcs regions. FBti0019400 (Bari1-Cyp12a4) is inserted in the 3′ UTR region of the cytochrome P450 gene Cyp12a4 and downstream of Ppcs. Enrichment of the histone marks relative to the input of each Bari1 region for each histone mark under nonstress (green) and stress (purple) conditions. Significant differences between regions are mark with an asterisk (p-value < 0.05) or two (p-value < 0,01).

Table 3.

Statistical analyses of histone mark enrichment in the Bari-CyP region.

| Histone | Gene region | Comparison | K-W test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | CyP12a4 | Stress - nonstress | 0.8728 |

| Ppcs | Stress - nonstress | 0.3367 | |

| H3K9me3 | CyP12a4 | Stress - nonstress | 0.6310 |

| Ppcs | Stress - nonstress | 0.1093 | |

| H3K27me3 | CyP12a4 | Stress - nonstress | 0.0065 |

| Ppcs | Stress - nonstress | 0.0065 |

Significant values are highlighted in bold.

Discussion

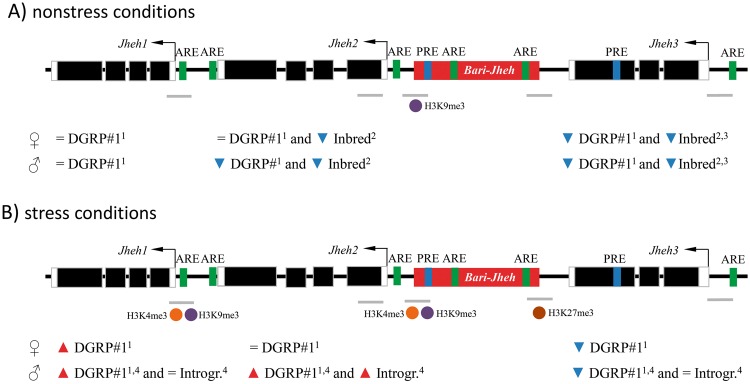

In nonstress conditions, Bari-Jheh adds H3K9me3 to the intergenic region between Jheh2 and Jheh3 genes (Figs 2 and 5). H3K9me3 histone mark is associated with transcriptionally silent regions, and several TE insertions are enriched for this histone mark36,40,41. The presence of this histone mark is consistent with changes in expression of Bari-Jheh nearby genes12–14. Flies with Bari-Jheh showed lower levels of expression of Jheh2 and Jheh3 compared with flies without this insertion in nonstress conditions in DGRP#1 outbred population and in inbred strains, while no changes in expression were reported for Jheh1 in the outbred population12–14.

Figure 5.

Summary of the histone enrichments found in the Bari-Jheh genomic region. Representation of the histone mark enrichement in each position for strains with Bari-Jheh compared with strains without Bari-Jheh. H3K4me3 is represented with an orange ball, H3K9me3 with a purple ball and H3K27me3 with a brown ball. Blue small triangles represent gene down-regulation, and red small triangles represent gene up-regulation. The upper scheme represents the enrichment under nonstress conditions and the lower scheme represents the enrichment under oxidative stress conditions.

We did not find evidence for the spreading of H3K9me3 found in the Bari-Jheh insertion to nearby genes as has been previously reported for ≥50% of euchromatic TEs38. Consistently, no changes in expression in Jheh1 have been found when comparing flies with and without Bari-Jheh insertion (Fig. 5). Why some TEs are associated with the spreading of epigenetic marks while others are not is still an open question.

In oxidative stress conditions, the presence of Bari-Jheh is associated with enrichment of H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 both in the Bari-Jheh2 intergenic region and in the promoter region of Jheh1 (Fig. 5). H3K4me3 and H3K9m3 have both been associated with active promoters33,42. Although H3K9me3 is generally considered as a silencing chromatin mark, it has also been associated with promoters of active genes42. Indeed, both Jheh2 and Jheh1 genes have repeatedly been found to be up-regulated in flies with Bari-Jheh insertion under oxidative stress conditions12,15. We also found that the Bari-Jheh3 intergenic region is enriched for H3K27me3 in flies carrying the Bari-Jheh insertion. This result is consistent with the presence of a PRE in Bari-Jheh and in Jheh3 gene. Consistently, we have previously found that Jheh3 is downregulated in oxidative stress conditions in flies that carry Bari-Jheh insertion12,15. In addition, we also found that Bari1-Cyp12a4, another TE insertion that belongs to the Bari1 family, showed an enrichment of H3K27me3 under oxidative stress conditions. Our results are thus consistent with previous findings in human cell culture that found an increase in the methylation marks in histone H3 in lysines K4, K27, and K9 in oxidative stress conditions43.

Overall, our results suggest that besides adding cis-regulatory regions, Bari-Jheh also adds histone marks to the intergenic region between Jheh2 and Jheh3 genes, and it is associated with histone marks enrichment in the promoter of Jheh1 gene. The presence of these histone marks was consistent with changes in expression previously reported for these three genes by analyzing flies with different genetic backgrounds differing in the presence/absence of Bari-Jheh insertion (Fig. 5). How often the effect of TEs on gene expression is due to the presence of transcription factor binding sites in the TE sequence and/or to the enrichment of histone marks remains to be determined. Genome-wide analysis in which changes in gene expression are investigated together with binding of transcription factors and presence of histone marks in TE insertions in several genetic backgrounds are needed to solve this question.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Equipe Eléments transposables, Evolution, Populations for their support to L.G. We thank Elena Casacuberta for sharing antibodies and technical advice; Jon Frias for helping to create the new outbred populations, and Anna Ullastres for help with the piRNA and HP1a binding site analyses. We also thank the CNRS and the Molecular Biology facility DTAMB from the FRbioEnvis. This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (BFU2014-57779-P and RYC-2010-07306 to J.G.); Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2014SGR201 to J.G. and 2012FI-B-00676 to L.G.); European Commission (PEOPLE-2011-CIG-293860 and H2020-ERC-2014-CoG-647900 to J.G.) and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (DEP20131128536) and ANR Exhyb (ANR-14-CE19-0016) to C.V.

Author Contributions

L.G. designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript draft, C.V. designed the experiments and analyzed the data and edited the manuscript, and J.G. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30491-w.

References

- 1.Slotkin RK, Martienssen R. Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:272–285. doi: 10.1038/nrg2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowley M, Oakey RJ. Transposable Elements Re-Wire and Fine-Tune the Transcriptome. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(1):e1003234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makarevitch, I. et al. Transposable Elements Contribute to Activation of Maize Genes in Response to Abiotic Stress. PLoS Genet11 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Sundaram V, et al. Widespread contribution of transposable elements to the innovation of gene regulatory networks. Genome Res. 2014;24:1963–1976. doi: 10.1101/gr.168872.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batut P, Dobin A, Plessy C, Carninci P, Gingeras TR. High-fidelity promoter profiling reveals widespread alternative promoter usage and transposon-driven developmental gene expression. Genome Res. 2013;23:169–180. doi: 10.1101/gr.139618.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le TN, Miyazaki Y, Takuno S, Saze H. Epigenetic regulation of intragenic transposable elements impacts gene transcription in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3911–3921. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Weigel D, Smith LM. Transposon variants and their effects on gene expression in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sentmanat M, Elgin SC. Ectopic assembly of heterochromatin in Drosophila melanogaster triggered by transposable elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14104–14109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207036109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YC. The Role of piRNA-Mediated Epigenetic Silencing in the Population Dynamics of Transposable Elements in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCue AD, Nuthikattu S, Reeder SH, Slotkin RK. Gene expression and stress response mediated by the epigenetic regulation of a transposable element small RNA. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mateo L, Ullastres A, Gonzalez J. A transposable element insertion confers xenobiotic resistance in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guio L, Barron MG, Gonzalez J. The transposable element Bari-Jheh mediates oxidative stress response in Drosophila. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:2020–2030. doi: 10.1111/mec.12711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez J, Lenkov K, Lipatov M, Macpherson JM, Petrov DA. High rate of recent transposable element-induced adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez J, Macpherson JM, Petrov DA. A recent adaptive transposable element insertion near highly conserved developmental loci in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1949–1961. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guio L, Gonzalez J. The dominance effect of the adaptive transposable element insertion Bari-Jheh depends on the genetic background. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:1260–1266. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slade JD, Staveley BE. Extended longevity and survivorship during amino-acid starvation in a Drosophila Sir2 mutant heterozygote. Genome. 2016;59:311–318. doi: 10.1139/gen-2015-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joos JP, et al. Ectopic expression of S28A-mutated Histone H3 modulates longevity, stress resistance and cardiac function in Drosophila. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2940. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21372-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An PNT, et al. Epigenetic regulation of starvation-induced autophagy in Drosophila by histone methyltransferase G9a. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7343. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07566-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathelier, A. et al. JASPAR2016: a major expansion and update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.dos Santos G, et al. FlyBase: introduction of the Drosophila melanogaster Release 6 reference genome assembly and large-scale migration of genome annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D690–697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ullastres A, Petit N, Gonzalez J. Exploring the Phenotypic Space and the Evolutionary History of a Natural Mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:1800–1814. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, et al. Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell. 2009;137:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satyaki PR, et al. The Hmr and Lhr hybrid incompatibility genes suppress a broad range of heterochromatic repeats. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM (2013).

- 25.Barnett DW, Garrison EK, Quinlan AR, Stromberg MP, Marth GT. BamTools: a C++ API and toolkit for analyzing and managing BAM files. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1691–1692. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kharchenko PV, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:480–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackay TF, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature. 2012;482:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang W, et al. Natural variation in genome architecture among 205 Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel lines. Genome Res. 2014;24:1193–1208. doi: 10.1101/gr.171546.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sykiotis GP, Bohmann D. Keap1/Nrf2 signaling regulates oxidative stress tolerance and lifespan in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2008;14:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guio, L., Gonzalez, J. & Vieira, C. Stress affects the epigenetic marks added by Bari-Jheh: a natural insertion associated with two adaptive phenotypes in Drosophila. bioRxive037598 (2016).

- 31.Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:343–357. doi: 10.1038/nrg3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V. A new world of Polycombs: unexpected partnerships and emerging functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:853–864. doi: 10.1038/nrg3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shlyueva D, Stampfel G, Stark A. Transcriptional enhancers: from properties to genome-wide predictions. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:272–286. doi: 10.1038/nrg3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ringrose L, Rehmsmeier M, Dura JM, Paro R. Genome-wide prediction of Polycomb/Trithorax response elements in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Cell. 2003;5:759–771. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00337-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herz HM, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase dUTX is a suppressor of Notch- and Rb-dependent tumors in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2485–2497. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01633-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rebollo R, et al. A snapshot of histone modifications within transposable elements in Drosophila wild type strains. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddington JP, et al. Redistribution of H3K27me3 upon DNA hypomethylation results in de-repression of Polycomb target genes. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, Y. C. G. & Karpen, G. H. Pervasive epigenetic effects of Drosophila euchromatic transposable elements impact their evolution. Elife6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Marsano RM, Caizzi R, Moschetti R, Junakovic N. Evidence for a functional interaction between the Bari1 transposable element and the cytochrome P450 cyp12a4 gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Gene. 2005;357:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasuhara JC, Wakimoto BT. Molecular landscape of modified histones in Drosophila heterochromatic genes and euchromatin-heterochromatin transition zones. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fablet M, et al. Genomic environment influences the dynamics of the tirant LTR retrotransposon in Drosophila. FASEB J. 2009;23:1482–1489. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-123513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin H, Sweeney S, Raha D, Snyder M, Lin H. A high-resolution whole-genome map of key chromatin modifications in the adult Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niu Y, DesMarais TL, Tong Z, Yao Y, Costa M. Oxidative stress alters global histone modification and DNA methylation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;82:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.