Abstract

Background One common model utilized to understand clinical staff and patients' technology adoption is the technology acceptance model (TAM).

Objective This article reviews published research on TAM use in health information systems development and implementation with regard to application areas and model extensions after its initial introduction.

Method An electronic literature search supplemented by citation searching was conducted on February 2017 of the Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases, yielding a total of 492 references. Upon eliminating duplicates and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 134 articles were retained. These articles were appraised and divided into three categories according to research topic: studies using the original TAM, studies using an extended TAM, and acceptance model comparisons including the TAM.

Results The review identified three main information and communication technology (ICT) application areas for the TAM in health services: telemedicine, electronic health records, and mobile applications. The original TAM was found to have been extended to fit dynamic health service environments by integration of components from theoretical frameworks such as the theory of planned behavior and unified theory of acceptance and use of technology, as well as by adding variables in specific contextual settings. These variables frequently reflected the concepts subjective norm and self-efficacy, but also compatibility, experience, training, anxiety, habit, and facilitators were considered.

Conclusion Telemedicine applications were between 1999 and 2017, the ICT application area most frequently studied using the TAM, implying that acceptance of this technology was a major challenge when exploiting ICT to develop health service organizations during this period. A majority of the reviewed articles reported extensions of the original TAM, suggesting that no optimal TAM version for use in health services has been established. Although the review results indicate a continuous progress, there are still areas that can be expanded and improved to increase the predictive performance of the TAM.

Keywords: technology acceptance model, literature review, health information technology, technology acceptance, theoretical models, health informatics

Background and Significance

New technologies are continuously being adopted in health services. 1 2 Modern information and communication technology (ICT) has been understood to improve service quality in the health service sector in general and in clinical medicine and at hospitals in particular, enhancing patient safety, staff efficiency and effectiveness, and reducing organizational expenses. 3 4 5 6 Meanwhile, progress in the life sciences has led to higher medical specialization and needs to exchange health information across institutional borders. 7 8 Despite these needs, health information systems development methods and research have focused on the technical aspects of the system design. 9 10 11 12 13 If the latter efforts are insufficient to meet the needs of progressive health service organizations and individual users, ICT investments will be spent ineffectively, and, potentially, patients put at risk. 14 Therefore, the impact on ICT adoption of different nontechnical and individual-level factors need to be established. 15 In this regard, it is positive that technology acceptance studies at the present are considered to stand as a mature field in information systems research. 16

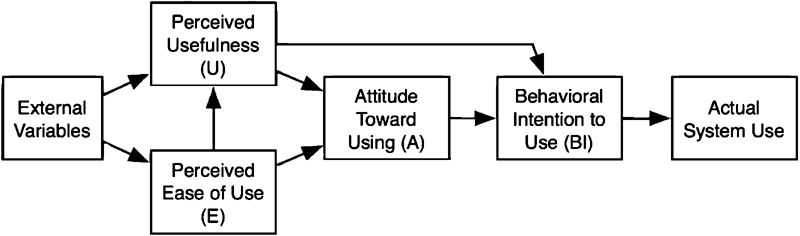

During the past 30 years, several theoretical models have been proposed to assess and explain acceptance and behaviors in association with ICT introduction. Robust measures have been developed of how well a technology “fits” with user tasks and have validated these task–technology fit instruments. 17 The best known of these is the technology acceptance model (TAM), which was presented in 1989, 18 and has during this period been applied and empirically tested in a wide spectrum of ICT application areas. 19 20 Also, the TAM is one of the most popular research models to predict use, person's intention to perform a particular behavior, and acceptance of information systems and technology by individual users. 21 22 Originally, the TAM was derived from the social psychological theories of reasonable action (TRA) and planned behavior (TPB), 23 these three models focus on a person's intention to perform the behavior, 24 but the constructs of these three models are different and not exactly the same. The TAM has become the dominant model for investigating factors affecting users' acceptance of novel technical systems. 25 The basic model presumes a mediating role of perceived ease of use and usefulness in association between system characteristics (external variables) and system usage (as shown in Fig. 1 ). 26 Several reviews of TAM use encompassing the ICT field in total have been issued. Accounts of the first decade of TAM-related research and suggestions of future directions were offered in 2003 by Lee et al 27 and Legris et al. 25 The directions included a need for incorporating more variables related to human and social change processes and exploring boundary conditions. At that time, the original TAM had already been modified in the TAM2 version 28 by removal of the “Attitudes” concept and differentiating the “External variables” concept into social influence (subjective norm, voluntariness, and image), cognitive instrumental processes (job relevance, output quality, and result demonstrability), and experience. A few years later, Sharp continued to discuss the relative strengths of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease and the role of attitudes in user acceptance, but also brought to the fore differences between volitional and mandatory use environments. 29 Venkatesh et al proposed a unified model—the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT)—based on studies of eight prominent models (in particular the TAM). The UTAUT is formulated with four core determinants of intentions and usage: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions, together with four moderators of key relationships: gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of use. 16 The same year, King and Jun conducted a statistical meta-analysis of TAM applications in various fields, reporting the TAM to be a valid and robust model that has been widely used. 30 In 2008, the TAM2 was extended with regard to determinants of perceived ease of use (PEOU) (TAM3). 31 The TAM3 is composed of four constructs: PEOU, PU, behavior intention, and use behavior.

Fig. 1.

The basic technology acceptance model. 18

Turning the attention from theory building to use environments, Turner et al concluded that care should be taken when using a particular version of the TAM outside the context in which the version originally was validated. 32 Proceeding with the analyses of model validity across use environments, Hsiao and Yang used cocitation analyses to identify three main application contexts for TAM use: (1) task-related systems, (2) e-commerce systems, and (3) “experiential” (or “hedonic”) systems. 33

Task-related systems are designed to improve task performance and efficiency. These systems can be categorized as automation software, office systems, software development, and communication systems such as electronic health record (EHR). Clinical practice guidelines, linked educational content, and patient handouts can be part of the EHR. This may permit finding the answer to a medical question while the patient is still in the examination room. 34 e-Commerce is the activity of buying or selling of products on online services or over the Internet. 35 The “hedonic” information systems are usually connected to home and leisure activities, focusing on the fun or novel aspect of information systems includes online gaming, online surfing, online shopping, and even online learning while perusing enjoyment at the same time. 33

In 2010, Gagnon et al conducted a systematic review to investigate factors influencing the adoption of ICT by health care professionals. In this review, including all ICT acceptance models in health services, it was concluded that PU of system and PEOU were the two most influential factors. 36 These two factors are the main components of the original TAM. 22 Regarding applications in specific health services areas, Strudwick concluded from a review of TAM applications among nursing practitioners that a modified TAM with variables detailing the health service context and user groups added could provide a better explanation of nurses' acceptance of health care technology. 37 Further, Ahlan and Isma'eel reported from an overview of patient acceptance of ICT that the TAM is one of the most useful models for studying patients' perceptions and behaviors. 38 Also, Garavand et al concluded from their general review of the most widely used acceptance models in health services that the TAM is the most important model used to identify the factors influencing the adoption of information technologies in the health system. 39

Objective

The objective of this systematic review was to compile published research on TAM use in health information systems development and implementation with regard to application areas and model modifications after its initial introduction, and also to gain understanding of the existing research and debates relevant to a particular topic or area of study. In the present setting, the development of health services requires parallel adjustments of ICT support, and accordingly, of TAMs.

Method

We used systematic search processes to identify all published original articles related to TAM applications in health services from 1989, the year when the TAM was introduced, to February 2017. The PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were searched and English-only publications selected. The broad keywords used for the initial search are displayed in Table 1 . The authors, title, journal, year of publication, and abstract for each article were collected in an Excel spreadsheet. First, the publication's titles, and abstracts, were assessed together by two of the four authors, after reviewing all abstracts and eliminating those categorized with exclusion criteria or lacking inclusion criteria; the full texts of the relevant articles were then reviewed by three authors together. The full texts of the remaining articles were read for eligibility, and the qualified publications were retained in a list. A search of the recent reviews and hand-searching references from articles were made to get related articles. The TAM has been used in many technological and geographical contexts. Several major technologies like mobile and telemedicine have variety of applications. 40 41 In a separate phase, the technologies and applications as a subset of major technological contexts and characteristics of each tested model for user groups were identified by three authors together. Finally, the publications in the list were classified into three categories according to their aim and content:

Table 1. Terms used in search.

| Keyword | Boolean | Additional keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Technology acceptance model (TAM) | AND | Healthcare |

| Technology acceptance model, TAM, hospital information system (HIS), extended technology acceptance model, TAM2, TAM3 | AND | Healthcare, medicine, health information system (HIS), telemedicine, telehealth, electronic health record (EHR), computerized physician medication order entry (CPOE), medication system, bar code medication administration (BCMA) |

Original TAM: Applications of the original TAM. In this category, the relationship between the main constructs of the original TAM is examined. These relationships include the relationship between PU and perceived ease to use with intention to use and also the relationship between perceived ease to use and PU.

Development and Extension of TAM: Reports of new insights related to the core elements of TAM and/or development of new TAM versions by integrating new factors and other acceptance theory variables with the original TAM. These factors incorporate into the constructs of the original TAM as predictive and moderating variables.

Comparisons of the TAM with other technology acceptance models: The TAM and other theoretical models are compared by examining factors associated with the adoption of a particular technology.

Results

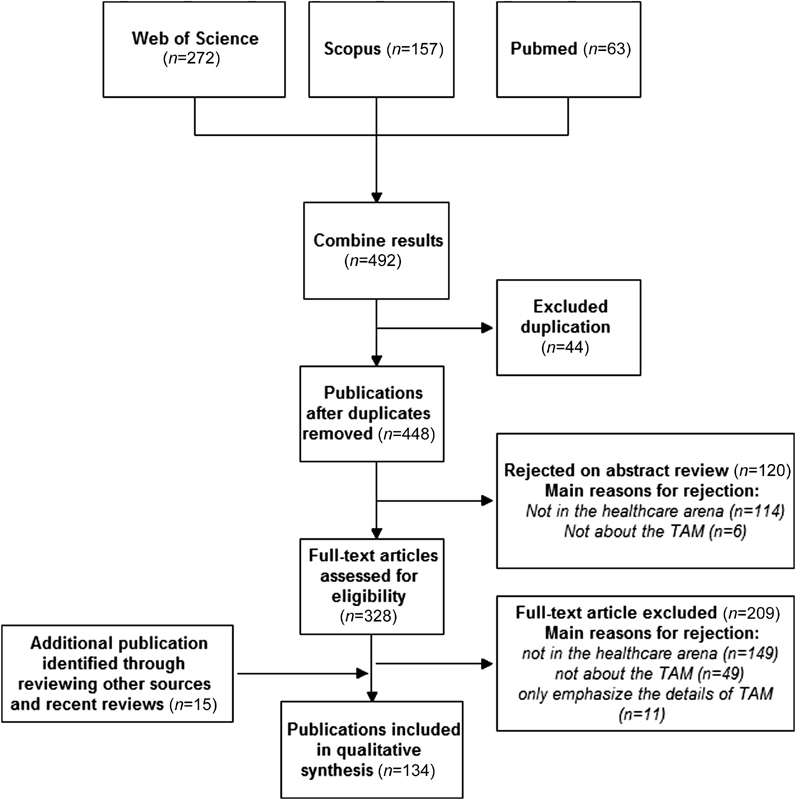

A total of 492 document references were retrieved from the database searches. After removal of 44 duplicates, 448 publications were entered into the selection process. Results of the screening process in the analysis are noted in the flow diagram in Fig. 2 . First, 448 publications' titles and abstracts were assessed together by two of the four authors. At this stage, 120 articles unrelated to the topic were excluded from the review. The full texts of the relevant articles were then reviewed by three authors together. The titles and abstracts of the relevant articles were then reviewed by three authors. When the title or abstract was deemed significant for inclusion in the review, the full text was scanned to ensure that the content was relevant. At this stage, 209 articles that were unrelated to acceptance of technology in health care, TAM constructs, or only addressed separate components of the TAM and other acceptance models were excluded. When there was disagreement, the authors evaluated their assessment until consensus was reached. A search of the recent reviews and hand-searching references from articles yielded an additional 15 papers. The systematic search of the literature identified 134 articles that reported original empirical research on the use of the TAM within health services.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of the study.

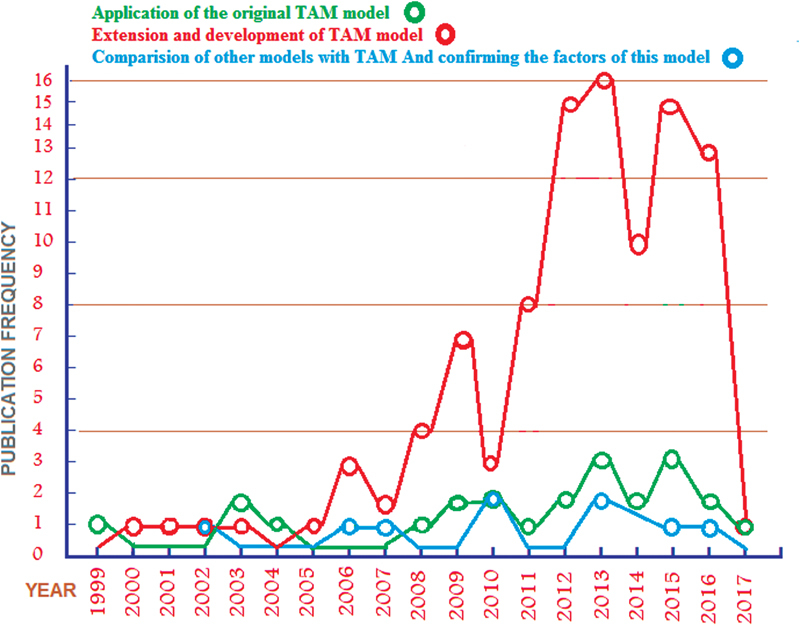

Publications dealing with the original TAM had peaked ( n = 3, 2.2% of all articles) in 2013 and 2015, publications on development and extension of TAM peaked ( n = 16, 11.9%) in 2013, while publications reporting comparisons of TAMs had peaked ( n = 2, 1.5%) in years 2010 and 2013 ( Fig. 3 ). A general increase in reports of TAM use suggests a persisting interest in understanding technology acceptance in health services. Also, there was a noteworthy leap in reports of TAM extensions in 2012 ( Fig. 3 ), which implies a recent highlighting of the influence from external factors on technology acceptance. The 134 articles reporting on TAM use had been published in 72 scientific journals, and originated from 30 countries; 29 (21.6%) studies from the United States, 28 (20.9%) from Taiwan, 14 (10.4%) from Spain, while the remaining articles originated from countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa. The journals with the highest numbers of articles were International Journal of Medical Informatics with 11 studies (8.14%), Telemedicine and e-Health with 10 studies (7.4%), and BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, with 8 studies (5.9%).

Fig. 3.

Frequency of articles reporting technology acceptance model use according to the three study categories displayed by year.

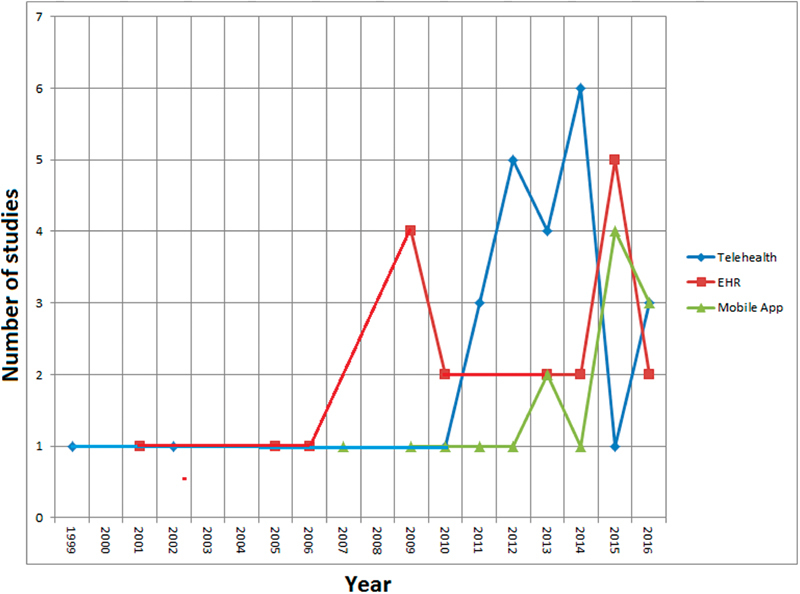

The first study of a TAM use in health services was reported in 1999, 42 analyzing physicians' intentions associated with the adoption of the telemedicine technology in a Hong Kong hospital setting. The ICT application area in which the TAM was first more frequently applied was EHR for which a peak in publications was observed in 2009. Publications reporting the TAM applications in telemedicine reached its peak in 2014, while the use of the TAM for analyses of mobile applications did peak in 2015. The first integration of several acceptance models with the TAM in health services was reported from Finland for examining acceptance of mobile systems among physicians. 43 In this study, the TAM was combined with the UTAUT and Personal Innovativeness in the Domain of Information Technology (PIIT) models.

Three main technological contexts were identified for applications of the TAM ( Table 2 ): (1) Telemedicine with 25 studies (18.6%), (2) EHR with 21 studies (15.7%), and (3) mobile applications with 15 studies (11.2%). Researchers in different countries have focused on different specific technologies: researchers in Taiwan on telemedicine (8 articles), mobile applications ( n = 5), and hospital information systems (HIS) ( n = 4); in the United States on EHRs ( n = 8), computers, handheld (personal digital assistants [PDAs]) ( n = 4), telemedicine, and personal health records ( n = 2); and in Spain on telemedicine ( n = 6), while researchers from Iran have focused on EHR ( n = 3) technology ( Fig. 4 ).

Table 2. Numbers of articles analyzing ICT adoption using TAM (main topics according to the MeSH thesaurus).

| Main topic (MeSH) | Number | Directions of country based on technology |

|---|---|---|

| Telehealth | 25 | Taiwan (8), Spain (6), United States (2) |

| Electronic health record | 21 | United States (8), Iran (3) |

| Mobile applications | 15 | Taiwan (5) |

| HIT systems in general | 8 | − |

| Computers, handheld | 7 | United States (4) |

| Hospital information systems | 6 | Taiwan (4) |

| Decision support systems, clinical | 5 | − |

| Electronic prescribing | 4 | − |

| Health records, personal | 4 | United States (2) |

| Automatic data processing (bar code) | 3 | − |

| Radiology information systems | 2 | − |

| Medical order entry systems | 2 | − |

| Management information systems | 2 | − |

| Clinical information system | 2 | − |

| Enterprise resources planning | 2 | − |

| The remaining of the studies dealt with one technology each | ||

Abbreviations: CPOE, computerized physician order entry; HIT, health information technology; ICT, information and communication technology; MeSH, Medical Subject Headings; PACS, picture archiving and communication system; PDA, personal digital assistant; TAM, technology acceptance model.

Note: The parenthesized value is number of studies.

Fig. 4.

Technological contexts in using the technology acceptance model between geographical contexts. The parenthesized value is number of studies.

Telemedicine, the area where the TAM has been most widely applied, is also the first technology that was studied using the TAM ( Fig. 5 ). TAM application on mobile technologies was initiated in 2006 43 and these studies peaked in 2015. As shown in Table 3 , most studies have emphasized the acceptance of physicians ( n = 43, 32%) and nurses ( n = 34, 25.3%). Other users of technology acceptance include patients and clients of health services, pharmacists, and other medical professionals.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of three main technological contexts in using the technology acceptance model by year.

Table 3. Study user group definitions and the number of studies for each user group.

| User groups | Number of studies, percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Physicians | 43 (31.8) |

| Nurses | 34 (25.1) |

| Patients | 17 (13) |

| Health care professionals | 15 (11.1) |

| Health service staff | 13 (9.6) |

| General population | 9 (6.6) |

| Technology users | 8 (5.9) |

| Managers and providers | 4 (2.9) |

| Students | 3 (2.2) |

| Pharmacists | 2 (1.4) |

| Physiotherapists and midwives each | 1 (0.7) |

Applications of the Original TAM

As shown in Table 4 , 23 (17.1%) of the identified articles reported application of the original TAM. In most studies using the original TAM to assess technology acceptance, the main constructs (i.e., PU and perceived ease to use) of TAM were supported. The most frequent ICT application areas were telemedicine, n = 6 (26%) and PDA, n = 2 (8.6%). The study participants ranged from 10 to 1,942, with an average of 184. The user category involved in the most studies was nurses ( n = 4, 17%) followed by physicians and patients (both n = 3, 13%).

Table 4. Publications addressing the original TAM.

| Author(s) | Technology studied/Platform | Objective | Year | Sample population and approved factors | Setting | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu et al 42 | Telemedicine | The applicability of the TAM in explaining physicians' decisions to accept telemedicine technology in the health care context | 1999 | Physicians N = 421/ perceived ease of use not approved |

Hospital | Hong Kong |

| Barker et al 61 | Spoken dialogue system (SDS) | The application of TAM, to use spoken dialogue technology for recording clinical observations during an endoscopic examination | 2003 | Clinicians ( N = 12) |

Endoscopy center | United Kingdom |

| Chang et al 62 | Triage-based emergency medical service (EMS) personal digital assistant (PDA) support systems | Developing triage-based EMS (PDA) support systems among nurses and physicians by TAM | 2004 | Physicians, nurses ( N = 29) |

Emergency medical center |

Taiwan |

| Chang et al 63 | Emergency medical service PDA support systems | Extending well-developed, triage-based, EMS (PDA) support systems to cover prehospital emergency medical services | 2004 | Physicians, nurses ( N = 29) |

Hospital | Taiwan |

| Chen et al 64 | Web-based learning system | Understanding PHNs' BI toward Web-based learning based on the technology acceptance model (TAM) | 2008 | Nurses ( N = 202) |

Health centers | Taiwan |

| Wilkins 65 | Electronic health records (EHR) | Examining factors that may influence the adoption of electronic health records by TAM | 2009 | Health information managers ( N = 94) |

Hospital | United States |

| Marini et al 66 | BCMA system | Using the TAM to determine the level of nurses' readiness to use IT for medication administration | 2009 | Nurses ( N = 276) |

Hospital | Lebanon |

| Van Schaik et al 67 | Portable system for postural assessment | Assessing the TAM for the new system | 2002 | Physiotherapists ( N = 49) |

Spinal unit | United Kingdom |

| Huser et al 68 | A prototype of a flowchart-based analytical framework (RetroGuide) | Exploring acceptance of query systems called RetroGuide for retrieval EHR data | 2010 | Human subjects ( N = 18) |

Laboratory | United States |

| Cranen et al 69 | Web-based telemedicine service | The patients' perceptions regarding a Web-based telemedicine service with TAM among patient | 2011 | Patients ( N = 30) |

Homecare | The Netherlands |

| Hung and Jen 70 | Mobile health management services (MHMS) | This study introduces MHMS and employs the TAM to explore the intention of students in Executive Master of Business Management programs to adopt mobile health management technology | 2012 | Students ( N = 170) |

University | Taiwan |

| Aldosari 71 | Picture archiving and communication system (PACS) | The TAM was used to assess the level of acceptance of the host PACS by staff in the radiology department | 2012 | Staffs ( N = 89) |

Radiology department | Saudi Arabia |

| Noblin et al 72 | Personal health record | The TAM was used to evaluate to adopt personal health record | 2013 | Patients ( N = 10) |

Hospital | United States |

| Martínez-García et al 73 | Social network component | Assessing acceptance and use of the social network component (web 2.0) to enable the adoption of shared decisions among health professionals (this is highly relevant for multimorbidity patients care) using TAM | 2013 | Health care professionals ( N = 10) |

Health care center | Spain |

| Monthuy-Blanc et al 74 | Telemental health (psychotherapy delivered via videoconferencing) | Understanding the role of mental health service providers' attitudes and perceptions of psychotherapy delivered via videoconferencing on their intention to use this technology with their patients | 2013 | Providers of health care ( N = 205) |

Center of Telemental | Canada |

| Abdekhoda et al 75 | Health information management system | The acceptance of information technology in the context of health information management (HIM) by utilizing TAM | 2014 | Worker of medical record ( N = 187) |

Hospital | Iran |

| Cilliers and Stephen 76 | Telemedicine | Using of the TAM to identify the factors that influence the user acceptance of telemedicine among health care workers | 2014 | Health care workers ( n = 75) |

Hospital and clinic | South Africa |

| Ologeanu-Taddei et al 77 | Hospital information system (HIS) | Examining key factors of a HIS acceptance for the care staff, based on the main concepts of TAM | 2015 | Staffs ( N = 1,942) |

Hospital | France |

| Money et al 78 | Computerized 3D interior design applications (CIDAs) | Exploring the perceptions of community dwelling older adults with regards to adopting and using CIDAs with TAM | 2015 | Older adult ( N = 10) |

Homecare | United Kingdom |

| Faruque et al 79 | Geoinformatics technology in disaster disease surveillance | Assessing the feasibility of using geoinformatics technology in disaster disease surveillance uses by self-administration based on the technology acceptance model (TAM) | 2015 | Personnel ( N = 50) |

Health centers | Iran |

| Kivekäs et al 80 | Electronic prescription (e-prescription) system | Assessing general practitioners' (GP) experience of an electronic prescription (e-prescription) system and the use of a national prescription center | 2016 | General practitioners ( N = 269) |

Hospital | Finland |

| Abdullah et al 81 | Telemonitoring of home blood pressure (BP) | Exploring patients' acceptance of a BP telemonitoring service delivered in primary care based on the technology acceptance model (TAM) | 2016 | Patients ( N = 17) |

Homecare | Malaysia |

| Hanauer et al 82 | Computer-based query recommendation algorithm | Assessing computer-based query recommendation algorithm as part of a search engine that facilitates retrieval of information from EHRs using TAM | 2017 | Clinicians, staffs ( N = 33) |

Hospital | United States |

Abbreviations: BCMA, bar code medication administration; BI, business intelligence; EHR, electronic health record; IT, information technology; PHN, public health nurse; TAM, technology acceptance model.

Development and Extension

Of all studies, 102 (76.1%) studies reported development or extension of the TAM. In these studies, different factors and theories were incorporated to the original TAM ( Table 5 ). The factors investigated in the most commonly used technological contexts such as health information technology systems in general, telemedicine, EHR, mobile apps, HIS, E-prescription, PDAs, and personal health record are briefly provided. According to the results in various technological contexts, it is possible to draw basic factors that incorporate with the original TAM for each technological context. The most common factors added to the TAM in almost all technological contexts were, in order of importance and frequency of repetition, compatibility, subjective norm, self-efficacy, experience, training, anxiety, habit, and facilitators. These factors can be a basic model for most technological contexts with the incorporation of the original TAM and separate variables regarding a context.

Table 5. Publications addressing extension and development of TAM.

| Author(s) | Technology studied | Main topic | Years | Sample | Setting/ Incorporated theories and variable with the TAM | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rawstorne et al 83 | Patient care information system | Identifying the relevant issues necessary for applying the technology acceptance model and the theory of planned behavior to the prediction and explanation of mandated IS usage |

2000 | Nurses ( N = 61) |

Hospital/theory of planned behavior (TPB) | Australia |

| Handy et al 84 | Electronic medical records (EMR) | Studying primary care practitioners' views of an electronic medical records (EMR) system for maternity patients | 2001 | Physicians and midwives ( N = 167) | Hospital/ System acceptability, system characteristics, organizational characteristics, individual characteristics | New Zealand |

| Chismar and Sonja 85 | Internet and Internet-based health applications | Testing the extension to a widely used model in the information systems especially Internet in pediatrics | 2002 | Pediatricians ( N = 89) |

Hospital/ the TAM2 theory | United States |

| Liang et al 86 | Personal digital assistants (PDAs) | Predicting TAM to actual PDA usage | 2003 | Health care professionals ( N = 173) | –/ compatibility, support, personal innovativeness, job relevance | United States |

| Liu and Ma 87 | Service-oriented medical records | Extending TAM by embedding perceived service level (PSL) as a causal antecedent for health care workers' willingness to use application service-oriented medical records | 2005 | Health care worker ( N = 79) |

Hospital/ Perceived service level | United States |

| Han et al 43 | Mobile system | Examining acceptance of mobile system among physicians with the aid from mainly TAM, UTAUT and Personal Innovativeness in the Domain of Information Technology (PIIT) models | 2006 | Physicians ( N = 151) |

Health care sector/ gender, experience, age, personal innovativeness, compatibility, social influence | Finland |

| Liu and Ma 88 | Electronic medical records (EMR) | Introducing the notion of perceived system performance (PSP) to extend the TAM |

2006 | Medical professionals ( N = 77) | Hospital/ Perceived system performance | United States |

| Palm et al 89 | Clinical information system (CIS) | Designing an electronic survey instrument from two theoretical models (Delone and McLean, and TAM) to assess the acceptability of an integrated CIS | 2006 | Physicians, nurses, and secretaries ( N = 324) |

Hospital/ Building on the TAM and the DeLone and McLean ISS models | France |

| Kim and Chang 90 | Health information Web sites | Identifying the core functional factors in designing and operating health information Web sites | 2007 | Users ( N = 228) |

Home/ Information search, usage support, customization, purchase, and security | South Korea |

| Wu et al 91 | Mobile health care systems | Examining determines mobile health care systems (MHS) acceptance by health care professionals based on revised TAM | 2007 | Physicians, nurses, and medical technicians ( N = 137) | Hospital/ MHS self-efficacy, technical support and training, compatibility | Taiwan |

| Tung et al 92 | Electronic logistics information system | Nurses' acceptance of the electronic logistics information system with new hybrid TAM | 2008 | Nurses ( N = 258) |

Hospital/ Perceived financial cost, compatibility, trust | Taiwan |

| Lai et al 93 | Tailored Interventions for management of DEpressive Symptoms (TIDES) | Designing Tailored Interventions for management of DEpressive Symptoms (TIDES) program based on an extension of the TAM | 2008 | Patients ( N = 32) |

Clinics/ framework based on TAM2 (subjective norm, job relevance, experience) and modified TAM (socio-demo, adjustment, job relevance) | United States |

| Wu et al 94 | Adverse event reporting system | Investigating determines acceptance of adverse event reporting systems by health care professionals with extending TAM that integrates variables connoting trust and management support into the model | 2008 | Health care professionals ( N = 290) |

Hospital/ trust, management support, subjective norm | Taiwan |

| Yu et al 95 | Health information technology applications | Applying a modified version of the TAM2 to examine the factors determining the acceptance of health IT applications | 2009 | Staff members from long-term care facilities ( N = 134) | Long-term care/ age, subjective norm, image, job level, work experience, computer skills, voluntariness | Australia |

| Dasgupta et al 96 | Personal digital assistants (PDAs) | Evaluating pharmacists' behavioral intention to use PDAs with TAM2 | 2009 | Pharmacists ( N = 295) |

Hospital and community pharmacies/ The TAM2 theory | United States |

| Ilie et al 97 | Electronic medical record (EMR) | Examining physicians' responses to uses of EMR bases on TAM | 2009 | Physicians ( N = 199) |

Hospital/ System accessibility | United States |

| Trimmer et al 98 | Electronic medical records (EMRs) | Application models TAM, UTAUT, and organizational culture in several different phase for acceptance EMR | 2009 | Physicians ( N = –) |

Residency in family medicine/ Derived from TAM, UTAUT, and organizational culture | United States |

| Lin and Yang 99 | Asthma care mobile service (ACMS) = mobile phone | Integrating TAM and “subjective norm” and “innovativeness” in acceptance ACMS | 2009 | Patients ( N = 229) |

Remote areas/ person-centered, communication | China |

| Aggelidis and Chatzoglou 100 | Hospital information system (HIS) | Examining HIS acceptance by hospital personnel bases on TAM | 2009 | Hospital personnel ( N = 283) |

Hospital/ Derived based on UTAUT and TAM (Compatibility, training, social influence, facilitating condition, self-efficiency, anxiety) | Greece |

| Hyun et al 101 | Structured narrative electronic health record (EHR) model (electronic nursing documentation system) | Applying theory-based (combined technology acceptance model and task-technology fit model) and user-centered methods to explore nurses' perceptions of functional requirements for an electronic nursing documentation system | 2009 | Nurses ( N = 17) |

Hospital/ Combined TAM and task-technology fit (TTF) model | United States |

| Vishwanath et al 102 | Personal digital assistant (PDA) | Exploring the determinants of personal digital assistant (PDA) adoption in health care with TAM | 2009 | Physicians ( N = 215) |

Hospital/ age , position in hospital , cluster ownership , specialty | United States |

| Morton and Susan 103 | Electronic health record (EHR) | Adopting of an interoperable EHR in ambulatory card uses innovation diffusion theory and the TAM | 2010 | Physicians ( N = 802) |

University/ Combining innovation diffusion theory (IDT) and the TAM | United States |

| Zhang et al 104 | Mobile homecare nursing | Applying TAM2 in mobile homecare nursing | 2010 | Nurses ( N = 91) |

Home/ The TAM2 theory | Canada |

| Stocker 105 | Electronic medical records (EMRs) | Evaluating the TAM relevance of the intention of nurses to use electronic medical records in acute health care settings | 2010 | Nurses ( N = 97) |

Hospital/ Environment or context, nurse characteristics, EHR characteristic | United States |

| Lim et al 106 | Mobile phones | Women's acceptance of using mobile phones to seek health information basis on TAM | 2011 | Women ( N = 175) |

Home care/ Self-efficacy , anxiety , prior experience | Singapore |

| Schnall and Bakken 107 | Continuity of care record (CCR) | Assessing the applicability of TAM constructs in explaining HIV case managers' behavioral intention to use a CCR | 2011 | Managers ( N = 94) |

Center of HIV care/ Perceived barriers to use | United States |

| Kowitlawakul 108 | Telemedicine/electronic or remote technology (eICU) | Determining factors and predictors that influence nurses' intention to use the eICU technology bases on TAM | 2011 | Nurses ( N = 117) |

Hospital/ Support from physicians, years working in the hospital, support from administrator | United States |

| Egea and González 109 | Electronic health care records (EHCR) | Explaining physicians' acceptance for electronic health care records (EHCR systems) | 2011 | Physicians ( N = 254) |

Hospital/ Perceptions of institutional trust, perceived risk, information integrity | Spain |

| Hsiao et al 110 | Hospital information systems (HIS) | The application of TAM for evaluate HIS in among nursing personnel | 2011 | Nurses ( N = 501) |

Hospital/ system quality, information quality, user self-efficacy, compatibility, top management support, and project team competency | Taiwan |

| Orruño et al 111 | Teledermatology | Examining intention of physicians to use teledermatology using a modified TAM | 2011 | Physicians ( N = 171) |

Home/ Subjective norm, facilitator, habit, compatibility | Spain |

| Melas et al 112 | Clinical information systems | Explaining intention to use clinical information systems based on TAM | 2011 | Medical staff (total [ N = 604], physicians= 534) | Hospital/ Physician specialty, ICT knowledge, ICT feature demand | Greece |

| Pai and Kai 113 | Health care information systems | Adopting the system and services based on Model proposed by DeLone and Mclean and TAM | 2011 | Nurses, head directors, and other related personnel ( N = 366) |

Hospital/Model proposed by DeLone and Mclean and TAM | Taiwan |

| Jimoh et al 114 | Information and communication technology (ICT) | Using modified TAM in among maternal and child health workers | 2012 | Health workers ( N = 200) |

Rural regions/knowledge, endemic barriers (knowledge a separate factor from attitude) | Nigeria |

| Lu et al 115 | Hospital information system (HIS) | Exploring factors influencing the acceptance of HISs by nurses with derived model from TAM | 2012 | Nurses ( N = 277) |

Hospital/ Information system success model | Taiwan |

| Lakshmi and Rajaram 116 | Information technology (IT) applications and innovativeness | Analyzing the influence of IT applications and innovativeness on the acceptance of rural health care services uses by TAM | 2012 | Health personnel ( N = 465) |

Rural centers/ Information technology exposure, innovativeness, online information dependence | India |

| Jian et al 117 | USB-based personal health records (PHRs) | Factors that influencing consumer adoption of USB-based personal health records by TAM | 2012 | Patients ( N = 1,465) |

Hospital/ Subjective norm | Taiwan |

| Escobar-Rodríguez et al 118 | e-Prescriptions and automated medication management systems | Investigating health care personnel to use e-prescriptions and automated medication management systems with extensive TAM | 2012 | Physicians, nurses ( N = 209) |

Hospital/ perceived compatibility , perceived usefulness to enhance control systems, training , perceived risks | Spain |

| Ketikidis et al 119 | HIT systems | Applying modified TAM in acceptance of HIT systems in health care personnel | 2012 | Health professionals (nurses and medical doctors) ( N = 133) |

Hospital/ Computer anxiety , relevance , self-efficacy , subjective and descriptive norms , familiarity / use of computers | Greece |

| Chen and Hsiao 120 | Hospital information system (HIS) | Examining acceptance of hospital information systems (HIS) by physicians | 2012 | Physicians ( N = 81) |

Hospital/ System quality , information quality , service quality | Taiwan |

| Kim and Park 121 | Health information technology (HIT) | Developing and verify the extended technology acceptance model (TAM) in health care | 2012 | Health consumers ( n = 728) |

Home/ Incorporating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and theory of planned behavior (TPB), along with the TAM | South Korea |

| Parra et al 122 | Care service for the treatment of acute stroke patients based on telemedicine (TeleStroke) | Development, implementation, and evaluation of a care service for the treatment of acute stroke patients based on telemedicine (TeleStroke) using a TAM | 2012 | Medical professionals ( N = 34) |

Hospital/ Subjective norm, facilitating conditions | Spain |

| Gagnon et al 123 | Telemonitoring system | Using a modified TAM to evaluate health care professionals' adoption of a new telemonitoring system | 2012 | Health care professionals ( N = 234) |

Hospital/ habit, compatibility, facilitators, subjective norm | Spain |

| Wangia 124 | Immunization registry | Extending with contextual factors (contextualized TAM) to test hypotheses about immunization registry usage | 2012 | Immunization registry end-users ( n = 100) |

Unit of immunization registry/ job-task change, commitment to change, system interface characteristic, subjective norm, computer self-efficacy | United States |

| Wong et al 125 | Intelligent Comprehensive Interactive Care (ICIC) system (Telemedical) | Evaluating the users' intention using a modified technological acceptance model (TAM) | 2012 | Elderly people ( N = 121) |

Elderly care/ The TAM2 theory and enjoyment factor | Taiwan |

| Holden et al 126 | Bar-coded medication administration (BCMA) | Identifying predictors of nurses' acceptance of bar-coded medication administration (BCMA) | 2012 | Nurses ( N = 83) |

Hospital/ Social influence, training, technical support, age, experience, satisfaction | United States |

| Dünnebeil et al 127 | Electronic health (e-health) in ambulatory care (Telemedicine) | Extending technology acceptance models (TAMs) for electronic health (e-health) in ambulatory care settings by physicians | 2012 | Physicians ( N = 117) |

Ambulatory care/ building based on TAM and UTAUT (process orientation, importance of standardization, e-health knowledge, importance of documentation, importance of data security, intensity of IT utilization ) | Germany |

| Asua et al 128 | Telemonitoring | Examining the psychosocial factors related to telemonitoring acceptance among health care based on TAM2 | 2012 | Nurses, general practitioners, and pediatricians ( N = 268) |

Homecare/ Habit , compatibility , facilitator , subjective norm | Spain |

| Kummer et al 129 | Sensor-based medication administration systems | Usage of professional ward nurses toward sensor-based medication systems based on an TAM2 | 2013 | Nurses ( N = 579) |

Health associations/ Qualitative overload , quantitative overload , personal innovativeness | Australia |

| Sedlmayr et al 130 | Clinical decision support systems for medication | Testing acceptance of system by ED physicians with TAM2 | 2013 | Physicians ( N = 9) |

Hospital/ Resistance to change(RTC),compatibility (COM) | Germany |

| Abu-Dalbouh 131 | Mobile health applications | Using TAM to evaluate the system mobile tracking model | 2013 | Health care professionals ( N = –) |

–/ User satisfaction, attribute of usability | Saudi Arabia |

| Tavakoli et al 132 | Electronic medical record (EMR) | Investigating the TAM using EMR | 2013 | Users of EMR ( n = census) |

Central Polyclinic Oil Industry/data quality, user interface | Iran |

| Buenestado et al 133 | Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) based on computerized clinical guidelines and protocols (CCGP) | Determining acceptance of initial disposition of physicians toward the use of CDSS based on (CCGP) | 2013 | Physicians ( N = 8) |

Hospital/ compatibility, habits, facilitators, subjective norm | Spain |

| Escobar-Rodriguez and Bartual-Sopena 134 | Enterprise resources planning (ERP) systems | Analyzing the attitude of health care personnel toward the use of an ERP system in public hospital | 2013 | Health care personnel ( n = 59) |

Hospital/ Experience with IT, training, support, age | Spain |

| Su et al 135 | Telecare systems | Integrating patient trust with the TAM to explore the usage intention model of Telecare systems | 2013 | Patients ( N = 365) |

Hospital/Patient trust (including Social Trust, Institutional Trust) | Taiwan |

| Alali and Juhana 136 | Virtual communities of practice (VCoPs) | Exploring VCoPs satisfaction based on the technology acceptance model (TAM) and DeLone and McLean IS success model | 2013 | Practitioners ( N = 112) |

Hospital/ Developing from TAM and DeLone and McLean IS success models (knowledge quality [KQ], system quality [SyQ], service quality [SeQ], satisfaction [SAT]) | Malaysia |

| Wang et al 137 | Telecare system | Using telecare system to construct medication safety mechanisms for remote area elderly uses TAM | 2013 | Elderly patients ( N = 271) |

Remote areas/ Person-centered caring , communication | Taiwan |

| Chen et al 138 | Hospital e-appointment system | Understanding the influence on continuance intention in the hospital e-appointment system based on extended TAM | 2013 | Citizens ( N = 334) |

Home/ Relationship quality (including trust, satisfaction), continuance intention | Taiwan |

| Sicotte et al 139 | Electronic prescribing | Identifying the factors that can predict physicians' use of electronic prescribing bases on expansion of the technology acceptance model (TAM) | 2013 | Physicians ( N = 61) |

City region/ Social influence, practice characteristics, physician characteristics | Canada |

| Liu et al 140 | Web-based personal health record system | Extending TAM that integrates the physician–patient relationship (PPR) construct into TAM's original constructs for acceptance of Web-based personal health record system | 2013 | Patients ( N = 50) |

Medical center/ Physician–patient relationship (PPR) | Taiwan |

| Ma et al 141 | Blended e-learning systems (BELS) | Integrating task-technology fit (TTF), computer self-efficacy, the technology acceptance model and user satisfaction to hypothesize a theoretical model, to explain and predict user's behavioral intention to use a BELS | 2013 | Nurses ( N = 650) |

Hospitals and medical centers/ Integrating the TAM and task-technology fit (TTF) | Taiwan |

| Escobar-Rodríguez and Romero-Alonso 142 | Automated unit-based medication storage and distribution systems | Identifying attitude of nurses toward the use of automated unit-based medication storage and distribution systems and influencing factors bases on TAM | 2013 | Nurses ( N = 118) |

Hospital/ Training, perceived risk, experience level | Spain |

| Huang 143 | Telecare | Exploring people's intention to use telecare with aid from structural equation modeling (SEM) technique that is a modification of TAM | 2013 | People ( N = 369) |

City region/ Innovativeness, subjective norm | Taiwan |

| Portela et al 144 | Pervasive Intelligent Decision Support System (PIDSS) | Adopting of INTCare system making use of TAM3 in the ICU | 2013 | Nurses ( N = 14) |

ICU/ The TAM3 theory | Portugal |

| Johnson et al 145 | Evidence-adaptive clinical decision support system | Acceptance of evidence-adaptive clinical decision support system associated with an electronic health record system using TAM | 2014 | Internal medicine residents ( N = 44) |

Hospital/User satisfaction, computer knowledge, general optimism, self-reported usage, usage trajectory group, institutionalized use | United States |

| Zhang et al 146 | Mobile health | Assessment and acceptance between privacy and using mobile health with aid from TAM | 2014 | Patients ( N = 489) |

Hospital/ Personalization, privacy | China |

| Andrews et al 147 | Personally controlled electronic health record (PCEHR) | Examining how individuals in the general population perceive the promoted idea of having a PCEHR | 2014 | Patients ( N = 750) |

Homecare/Social norm, privacy concern, trust, perceived risk, controllability, Web self-efficacy, compatibility, perceived value | Australia |

| Gagnon et al 148 | Electronic health record (EHR) | Identifying the main determinants of physician acceptance of EHR in a sample of general practitioners and specialists | 2014 | Physicians ( N = 157) |

Hospital/ Integrating original TAM, extended TAM, psychosocial model | Canada |

| Hwang et al 149 | Prehospital telemetry | Factors influencing the acceptance of telemetry by emergency medical technicians in ambulances uses by extended TAM | 2014 | Emergency medical technicians ( n = 136) |

Hospital/ Job fit, loyalty, organizational facilitation, subjective norm, expectation confirmation, clinical factors, nonclinical factors | South Korea |

| Tsai 150 | Telehealth system | Integrating extended TAM and health belief model (HBM) for to identify factors that influence patients' adoption to use telehealth | 2014 | Patients ( N = 365) |

Home/ Integrating extended technology acceptance model (extended TAM) and health belief model (HBM) | Taiwan |

| Rho et al 151 | Telemedicine | Developing telemedicine service acceptance model based on the TAM with the inclusion of three predictive constructs from the previously published telemedicine literature: (1) accessibility of medical records and of patients as clinical factors, (2) self-efficacy as an individual factor, and (3) perceived incentives as regulatory factors | 2014 | Physicians ( N = 183) |

Medical centers and hospitals/ Self-efficacy, accessibility, perceived incentives | South Korea |

| Tsai 152 | Telehealth | Developing a comprehensive behavioral model for analyzing the relationships among social capital factors (social capital theory), technological factors (TAM), and system self-efficacy (social cognitive theory) in telehealth | 2014 | End users of a telehealth system ( N = 365) |

City region/ Integrating social capital theory (social trust, institutional trust, social participation), social cognitive theory (system self-efficacy) and TAM | Taiwan |

| Horan et al 153 | Online disability evaluation system | Developing a conceptual model for physician acceptance based on the TAM | 2004 | Physicians ( N = 141) |

Hospital/ Organizational readiness, technical readiness, perceived readiness, work practice compatibility, social demographics | United States |

| Saigí-Rubió et al 154 | Telemedicine | Analyzing the determinants of telemedicine use in the three countries with TAM | 2014 | Physicians ( N = 510) |

Hospital, health care centers of the urban and rural/ Optimism , propensity to innovate , level of ICT use | Spain, Colombia, and Bolivia |

| Steininger and Barbara 155 | Electronic health record (EHR) | Examining and extending factors influence acceptance levels among physicians, uses a modified (TAM) | 2015 | Physicians ( N = 204) |

Hospital/ Social impact, HIT experience, privacy concerns | Austria |

| Basak et al 156 | Personal digital assistant (PDA) | Using an extended TAM for exploring intention to use personal digital assistant (PDA) technology among physicians | 2015 | Physicians ( N = 339) |

Hospital/ Integrating the TAM and DeLone and McLean IS success models (knowledge quality, system quality, service quality and user satisfaction) | Turkey |

| Al-Adwan and Hilary 157 | Electronic health record (EHR) | Applying a modified version of the revised TAM to examine EHR acceptance and utilization by physicians | 2015 | Physicians ( N = 227) |

Hospital/ Compatibility , habit , subjective norm , facilitators | Jordan |

| Kowitlawakul et al 158 | Electronic health record for nursing education (EHRNE) | Investigating the factors influencing nursing students' acceptance of the EHRs in nursing education using the extended TAM with self-efficacy as a conceptual framework | 2015 | Students ( N = 212) |

Clinics/ Self-efficacy | Singapore |

| Michel-Verkerke et al. 59 | Patient record development (EPR) | Developing a model derived from the DOI and TAM theory for predicting EPR | 2015 | Patients ( N = –) |

–/ Derived from DOI and TAM theory | The Netherlands |

| Lin 160 | Hospital information system (HIS) | Using the perspective of TAM; national cultural differences in terms of masculinity/femininity, individualism/collectivism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance are incorporated into the TAM as moderators | 2015 | Nurses ( N = 261) |

Hospital/ Power distance, uncertainly avoidance, masculinity or femininity, individualism or collectivism, time orientation | Taiwan |

| Abdekhoda et al 59 | Electronic medical records (EMRs) | Assessing physicians' attitudes toward EMRs' adoption by a conceptual path model of TAM and organizational context variables | 2015 | Physicians ( N = 330) |

Hospital/ Management support, training, physicians' involvement, physicians' autonomy, doctor–patient relationship | Iran |

| Gartrell et al 161 | Electronic personal health records (ePHRs) | Using a modified technology acceptance model on nurses' personal use of ePHRs | 2015 | Nurses ( N = 847) |

Hospital/ Perceived data privacy and security protection, perceived health-promoting role model | United States |

| Carrera and Lambooij 162 | Out-of-office blood pressure monitoring | Developing an analytical framework based on the TAM, the theory of planned behavior, and the model of personal computing utilization to guide the implementation of out-of-office BP monitoring methods | 2015 | Patients, physicians ( N = 6) |

–/Framework based on the TAM, the TPB (including self-efficiency, social norm), and the model of personal computing utilization (including enabling conditions) | The Netherlands |

| Sieverdes et al 163 | Mobile technology | Investigating kidney transplant patients attitudes and perceptions toward mobile technology with aid from the technology acceptance model and self-determination theory | 2015 | Patients ( N = 57) |

Medical center/ Frameworks from the TAM and self-determination theory (SDT) | United States |

| Song et al 164 | Bar code medication administration technology | Using bar code medication administration technology among nurses in hospitals with TAM | 2015 | Nurses ( N = 163) |

Hospital/ Feedback and communication about errors, age, teamwork within hospital units, hospital management support for patient safety, nursing shift, education, computer skills, technology length of use | United States |

| Jeon and Park 165 | Mobile obesity-management applications (apps) | The acceptance of mobile obesity-management applications (apps) by the public were analyzed using a mobile health care system (MHS) (TAM) | 2015 | Public (health consumer) ( N = 94) |

Homecare/ Compatibility, self-efficacy, technical support and training | South Korea |

| Alrawabdeh et al 166 | Electronic health record (EHR) | The revealing factors that affect the adoption of EHR | 2015 | Final users ( N = 6) |

Health sector of NHS/ Clinical safety, security, integration, and information sharing | United Kingdom |

| Escobar-Rodríguez and Lourdes 167 | Enterprise resources planning (ERP) | Impact of cultural factors on user attitudes toward ERP use in public hospitals and identifying influencing factors uses by TAM | 2015 | Users ( N = 59) |

Hospital/ Resistance to be controlled, perceived risks, resistance to change | Spain |

| Briz-Ponce and García-Peñalvo 168 | Mobile technology and “apps” | Measurement and explain the acceptance of mobile technology and “apps” in medical education | 2015 | Students, medical professionals ( N = 124) |

University/ Reliability, social influence, facilitating conditions, self-efficacy, anxiety, recommendation | Spain |

| Lai et al 169 | Mobile hospital registration system | The use of the mobile hospital registration system | 2015 | Patients ( N = 501) |

Hospital/ Information technology experience (ITE) | Taiwan |

| Al-Nassar et al 170 | Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) | Behavior of CPOE among physicians in hospitals based on the technology acceptance model (TAM) | 2016 | physicians ( N = –) |

Hospital/ Instability of new software providers, software quality | Jordan |

| Lin et al 171 | Devices for monitoring elderly people's postures and activities | Designing and development of a novel, textile-based, intelligent wearable vest for real-time posture monitoring and emergency warnings | 2016 | Elderly people ( N = 50) |

Homecare/ Technology anxiety | Taiwan |

| Suresh et al 172 | Health information technology (HIT) | Analyzing the application of the technology acceptance model (TAM) by outpatients | 2016 | Patients ( N = 200) |

Hospital/ Customized information, trustworthiness | India |

| Ifinedo 173 | Information systems (ISs) | The moderating effects of demographic and individual characteristics on nurses' acceptance of information systems (IS) | 2016 | Nurses ( N = 197) |

Hospital/ Education, computer knowledge | Canada |

| Goodarzi et al 174 | Picture archiving and communication system (PACS) | The TAM has been used to measure the acceptance level of PACS in the emergency department | 2016 | Users ( N = census) |

Hospital/ Change | Iran |

| Abdekhoda et al 175 | Electronic medical records (EMRs) | Integrating a model to explore physicians' attitudes toward using and accepting EMR in health care | 2016 | Physicians ( N = 330) |

Hospital/ Integrated TAM and diffusion of innovation theory (DOI) model | Iran |

| Strudwick et al 176 | Electronic health record (EHR) | Developing integrated TAM using theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the TAM to explain behavior among nurses | 2016 | Nurses ( N = –) |

–/ Combining three different models theory of reasoned action (TRA), theory of planned behavior (TPB), and TAM | Canada |

| Hsiao and Chen 177 | Computerized clinical practice guidelines | Investigating critical factors influencing physicians' intention through an integrative model of activity theory, and the technology acceptance model | 2016 | Physicians ( N = 238) |

Hospital/ incorporating activity theory (three dimensions of factors) with TAM concepts (intention as dependent variable) | Taiwan |

| Saigi-Rubió et al 178 | Telemedicine | Investigating determinants of telemedicine use in clinical practice among medical professionals using the TAM2 and microdata | 2016 | Physicians ( N = 96) |

Health care institution/Security and confidentiality, subjective norm, physician's relationship with ICTs | Spain |

| Lin et al 179 | Nursing information system (NIS) | Developing a conceptual framework that is based on the technology acceptance model 3 (TAM3) and behavior theory | 2016 | Nurses ( N = 245) |

Hospital/ Framework that is based on the TAM3 and behavior theory (prior experience) | Taiwan |

| Ducey and Coovert 180 | Tablet computer | Evaluating practicing pediatricians to use of tablet based on extended technology acceptance model | 2016 | Pediatricians (physicians) ( N = 261) |

Hospital/ Subjective norm, compatibility, reliability | United States |

| Holden et al 181 | Novel health IT, the large customizable interactive monitor | Examining pediatric intensive care unit nurses' perceptions, acceptance, and use of a novel health IT, the large customizable interactive monitor bases on TAM2 | 2016 | Nurses ( N = 167) |

Hospital/ Social influence, perceived training on system, satisfaction with system, complete use of system | United States |

| Omar et al 182 | Prescribing decision support systems (EPDSS) | Investigating perception and use of EPDSS at a tertiary care using TAM2 | 2017 | Physicians(pediatricians) ( N = –) |

Hospital/ The TAM2 theory | Sweden |

Abbreviations: DOI, diffusion of innovation; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICT, information and communication technology; ICU, intensive care unit; IS, information system; IT, information technology; NHS, National Health Service; USB, Universal Serial Bus; UTAUT, unified theory of acceptance and use of technology.

Adding separate variables to develop contextualized TAM versions allows optimizing specific dimensions of the TAM in particular settings and thereby improving predictions in these contexts. A full summary of the additions to the original TAM displayed by technology application area in health services, theories integrated, and new factors and variables inserted is shown in Table 6 . The most commonly integrated theories were classic acceptance models such as UTAUT, TRA, Diffusion of Innovation theory, and the TPB. In addition to the theories, the conditions and technologies forming the particular context in specific settings have been used to add further concepts and variables, i.e., some factors were not derived from any technology acceptance theory and were instead specific to a certain technology (such as technology features, environmental conditions, user types, etc.). Among the 102 articles, only two studies were conducted on the TAM3.

Table 6. The factors, variables, and theories used in common technological contexts in studies (respectively, repetition and importance).

| Technology area | Factors (variables) and intention-based theories incorporated to original TAM based on different user groups and technological contexts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| User groups | Factors and variables | Intention-based theories | Extended TAM version used | |

| HIT systems in general | Health care professionals |

Knowledge, endemic barriers, anxiety, relevance, self-efficacy, subjective and descriptive norms, age, image, job level, work experience, computer skills, voluntariness, information technology exposure, innovativeness, online information dependence | DeLone and McLean IS success model | – |

| Nurses | Social influence, perceived training on system, satisfaction with system, complete use of system | – | – | |

| Patients | Customized information, trustworthiness. | Health belief model (HBM), TPB | – | |

| Hospital information system (HIS) | Physicians | System quality, information quality, service quality | – | TAM3 |

| Health care professionals |

Compatibility, training, social influence, facilitating condition, self-efficiency, anxiety | UTAUT | – | |

| Nurses | Power distance, uncertainly avoidance, masculinity or femininity, individualism or collectivism, time orientation, prior experience, system quality, information quality, self-efficacy, compatibility, top management support, project team competency | Information system success model | TAM3 | |

| Electronic health record (EHR) | Physicians | System acceptability, system characteristics, organizational characteristics, individual characteristics, system accessibility, organizational cultural, perceptions of institutional trust, perceived risk, information integrity, social impact, HIT experience, privacy concerns, compatibility, habit, subjective norm, facilitators, management support, training, physicians' involvement, physicians' autonomy, doctor–patient relationship | DOI, IDT, UTAUT | TAM2 |

| Health care professionals |

Perceived service level, perceived system performance, data quality, user interface, self-efficacy, clinical safety, security, integration and information sharing | – | – | |

| Nurses | Environment or context, nurse characteristics, EHR characteristic | TRA, TPB, TTF | ||

| e-Prescription systems | Physicians | Social influence, practice characteristics, physician characteristics, perceived compatibility, perceived usefulness to enhance control systems, training, perceived risks | – | – |

| Nurses | Perceived compatibility, perceived usefulness to enhance control systems, training, perceived risks | – | – | |

| Computers, handheld (PDAs) | Physicians | Subjective norm, compatibility, reliability, knowledge quality, system quality, service quality, user satisfaction, age, position in hospital, cluster ownership, specialty | DeLone and McLean IS success model | – |

| Health care professionals |

Compatibility, support, personal innovativeness, job relevance | – | – | |

| Nurses | − | – | – | |

| Pharmacists | Subjective norm, image, output quality, result demonstrability, job relevance, experience, voluntariness | – | TAM2 | |

| Telemedicine | Physicians | Security and confidentiality, relationship with ICTs, subjective norm, facilitators, habit, compatibility, self-efficacy, accessibility, perceived incentives, process orientation, importance of standardization, e-health knowledge, importance of documentation, importance of data, propensity to innovate, organizational readiness, technical readiness, social demographics, optimism, propensity to innovate, enabling conditions | UTAUT, TPB, personal computing utilization | TAM2 |

| Health care professionals |

Subjective norm, job fit, loyalty, expectation confirmation, clinical factors, nonclinical factors, habit, compatibility, facilitators | – | – | |

| Patients | Patient trust, person-centered caring, communication, enjoyment factor, social and institutional trust, social participation, self-efficacy, innovativeness, subjective norm, social norm, enabling conditions, technology anxiety | HBM, social capital theory, social cognitive theory, TPB, personal computing utilization | TAM2 | |

| Nurses | Support from physicians, experience, support from administrator. | – | – | |

| Mobile applications | Physicians | Gender, experience, age, personal innovativeness, compatibility, social influence | – | – |

| Health care professionals |

Reliability, social Influence, facilitating conditions, self-efficacy, anxiety, recommendation, user satisfaction, attribute of usability, technical support and training, compatibility | – | – | |

| Nurses | Subjective norm, image, output quality, result demonstrability, job relevance, experience, voluntariness | – | TAM2 | |

| Patients | Information technology experience (ITE), compatibility, self-efficacy, technical support and training, personalization, privacy, anxiety, prior experience, person-centered, communication | Self-determination theory (SDT) | – | |

| Personal health record (PHR) | Patients | Subjective norm, physician–patient relationship (PPR), social norm, privacy concern, trust, perceived risk, controllability, self-efficacy, compatibility, perceived value | DOI | – |

Abbreviations: DOI, diffusion of innovation; HIT, health information technology; ICT, information and communication technology; IDT, innovation diffusion theory; IS, information system; PDA, personal digital assistant; TAM, technology acceptance model; TPB, theory of planned behavior; TRA, theories of reasonable action; TTF, task-technology fit; UTAUT, unified theory of acceptance and use of technology.

Comparison of Other Technology Acceptance Models with TAM

Nine (6.7%) studies compared TAM with other TAMs. The most common ICT application area for these comparisons was mobile technology, n = 3 (33.3%). Typically, Hsiao and Tang 44 used different variables to investigate the introduction of mobile technologies from the perspective of the elderly people in Taiwan. Their results supported the validity of the TAM variables, and also the inclusion of novel factors such as perceived ubiquity, personal health knowledge, and perceived need for health care. Day et al 45 conducted a study to evaluate hospice providers' attitudes and perceptions regarding videophone technology in settings where the technology was introduced but underutilized. Findings indicate that the TAM provides a good framework for an understanding of telehealth underutilization.

In two studies on telemedicine acceptance among physicians in China and the United States, respectively, the TAM and the TPB model were compared. Interestingly, the findings from China suggested that the TAM was more valid than the TPB, while the TPB was more valid than the TAM in the United States. 46 47 Another study comparing the TAM and the UTAUT among physicians concluded that the usage intentions were strongly associated with the performance expectancy on attitude and attitude concepts. 48 Manimaran and Lakshmi 49 formulated an integrated TAM for Health Management Information System and concluded that health workers' innovativeness and voluntariness had a direct and positive influence on these intentions. Similarly, Smith and Motley 50 found that e-prescribing acceptance was predicted by the technological sophistication, operational factors, and maturity factors constructs, i.e., ease-of-use variables derived from the TAM. Liang et al 51 examined whether TAM can be applied to explain physician acceptance of computerized physician order entry (CPOE), and found that data analysis provided support for all relationships predicted by TAM but failed to support the relationship between ease of use and attitude. A follow-up analysis showed that this relationship is moderated by CPOE experience (more details of the nine studies are shown in Table 7 ).

Table 7. Other models' comparison with TAM and confirmation of suitability of the TAM factors.

| Author(s) | Technology studied | Main topic | Years | Sample | Setting | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chau and Jen-Hwa 46 | Telemedicine | Comparing different models, including TAM, the theory of planned behavior (TPB), and an integrated model for acceptance telmedicine | 2002 | Physicians ( N > 400) |

Hospital | China |

| Liang et al 51 | Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) | Examining whether the TAM can be applied to explain physician acceptance of CPOE | 2006 | Physicians ( N = 200) |

Hospital | China |

| Day et al 45 | Videophone technology | Evaluating hospice providers∍ attitudes and perceptions regarding videophone technology in the hospice setting in the context of the TAM | 2007 | Providers ( N = 17) |

Hospice | Colombia |

| Smith and Motley 50 | Electronic prescribing | The degree of e-prescribing acceptance is highly predictable by factors that are very stable ease-of-use variables derived from the TAM | 2010 | Pharmacists ( N = 50) |

Pharmaceutical company's supply | United States |

| Kim et al 47 | Telehomecare (telemedicine) | Comparing two theories of technology adoption, the technology acceptance model and the theory of planned behavior, to explain and predict physicians' acceptance and use of the telehomecare technology | 2010 | Physicians ( N = 40) |

Homecare | United States |

| Kuo et al 183 | Mobile electronic medical record (MEMR) systems | Confirming relationships between the TAM components, and behavioral intention in the technology acceptance model toward MEMR usage | 2013 | Nurses ( N = 665) |

Hospital | Taiwan |

| Manimaran and Lakshmi 49 | Health management information system (HMIS) | Formulating a model of technology acceptance of health management information system (HMIS) that features the TAM was confirmed | 2013 | Health workers ( N = 960) |

Rural health care | India |

| Hsiao and Tang 44 | Mobile health care devices | The use intention of mobile health care devices from the perspectives of elderly people | 2015 | Elderly people ( N = 338) |

– | Taiwan |

| Kim et al 48 | Mobile electronic health records (EMR) system | Confirming the factors that influence users' intentions to utilize a mobile electronic health records (EMR) system with TAM | 2016 | Health care professionals ( N = 942) |

Hospital | South Korea |

Abbreviation: TAM, technology acceptance model.

Discussion

The review showed that the TAM initially was applied to task-related ICT systems such as EHRs. These were often connected to educational processes leading to that system's impacts on learning and competence were natural critical influences on use intentions. Since the purpose of task-related systems is to enhance the users' task performance and improve efficiency, educational concepts can be expected to continue to play a dominant role within TAM in this domain. In other words, for the task-related systems such as EHRs, PU and self-efficacy related to learning can be expected to have stronger effects on usage than PEOU, 33 i.e., clinical users are likely to accept a new technology mainly if they recognize that it can help them to improve their work performance and build efficacy. 52 In addition to PU and self-efficacy, system quality, information quality, physicians' autonomy, security and privacy concerns, and cultural and organizational characteristics were found to be important for adoption of task-related technologies, such as EHRs and HISs.

The second aggregation of TAM research was focused on communication systems and telemedicine. The rapid development of worldwide Internet infrastructures has facilitated development of systems in this domain. Telemedicine applications have in particular allowed to introduce new organizational structures in health services 40 and consequently led to an interest in the use of the TAM to facilitate the organizational adaptation. Health care policy makers are still debating why institutionalizing telemedicine applications on a large scale has been so difficult, 53 and why health care professionals are often averse or indifferent to telemedicine applications. 40 54 We believe that user rejection is one of the important factors in institutionalizing various types of telemedicine applications. Therefore, it is important to examine the effective factors in accepting telemedicine applications by health care professionals. Consequently, when using the TAM on this category of systems, the validity of analyses with regard to the organizational fit of the novel ICT application is central. 55 56 Other factors commonly associated with technology adoption in this context include subjective norm, security and confidentiality, facilitators, accessibility, and self-efficacy.

Finally, the most recent trend in TAM use—on mobile technologies—is characterized by involving also patients as users. In this setting, the notion of “hedonic” system aspects, denoting factors associated with pleasure or happiness is of importance. 57 Different from the task-related systems, the concept of hedonic systems focuses on the enjoyable aspect of ICT use and consequently requires other types of factors and variables for analyses of use intentions. Intrinsic motivational factors such as usability and perceived liveliness are in this setting as influential as the PU. The progress from EHRs to mobile technologies in ICT applications has required also the TAM to be dynamically adapted. Based on this, progress of technology introduction in health services cannot be seen to decrease, and a need to modify the TAM to keep up with the new application areas can be also foreseen in the future. Common factors for hedonic such as mobile apps include usability, user satisfaction, reliability, privacy, compatibility, innovativeness, subjective norm, self-efficacy, technical support and training, anxiety, and communication. Also, a theory that integrates with the original TAM to examine the hedonic systems is the self-determination theory (SDT). SDT is a theory of motivation that is concerned with supporting our natural or intrinsic tendencies to behave in effective and healthy ways. 58

In the extensions of the TAM observed in the review, a wide range of technological context factors and circumstances were introduced. Examples of such factors include physicians' autonomy, doctor–patient relationship, project team competency, clinical safely, job fit, and optimism, as well as patient user group, 59 voluntariness of the ICT use, and whether the ICT systems were prototypes, trial systems, to-be-implemented systems, or implemented systems. Other revisions had more to do with explicitly stating contextual circumstances, rather than extensions per se. For instance, over the life course of an ICT application, the relationships in the TAM may change, e.g., usability may initially be critical but less important later on. Two methods to add novel concepts and variables to the TAM were highlighted in this review. The first, theory-based additions can be expected to allow comparisons between ICT application areas and harmonization between ICT applications and different organizational processes.

However, it has been suggested that a main reason for inconsistent predictive performance of the TAM in health services is the poor match between construct operationalization and the context in which the construct is measured, 29 The second method to expand the TAM is to add contextualized TAM concepts that increase predictive power. One method to derive such contextualized concepts is belief elicitation 60 which was also the process used to fit general behavioral theory to the ICT context when developing the TAM. 20 However, this step-wise method is less suitable for comparisons between application areas and analyses of the organizational fit of new ICT applications from a general health service perspective. The results of this review suggest that consensus is needed upon how the TAM extension processes should be designed for uses in health services.

The primary threats to the validity of this review are concerned with the search strategy employed. First, it may be possible that we have not identified all relevant publications. The completeness of the search is dependent upon the search criteria used and the scope of the search, and is also influenced by the limitations of the search engines used. Publication bias is possibly a further threat to validity, in that we were primarily searching for literature available in the major computing digital libraries. It is possible that, as a result, we included more studies reporting positive results of the TAM as those publications reporting negative results are less likely to be published. Since we have been unable to undertake a formal meta-analysis, we are equally unable to undertake a funnel analysis—using a series of events that lead toward a defined goal—to investigate the possible extent of publication bias. Finally, it must be remembered that the TAM does not measure the benefit of ICT use, 57 implying that measures of technology acceptance and use intentions should not be mistaken for measures of technology value. Separate studies using measures of effectiveness or productivity are needed to assess the organizational value of the new technology.

The review was limited to those articles describing only the TAM and its application in health care service. By restricting our review to a narrow segment of this literature, we may have inadvertently eliminated meaningful details from other acceptance models and factors in health technologies acceptance. Also, there are books and book chapters that deal with the TAM in health care. These types of publications are not included in our review, but may contain information relevant to this review. Finally, our review includes only articles in English language and languages other than English might have information about the TAM in health care.

Conclusion