Abstract

The regulation of interdigital tissue regression requires the interplay of multiple spatiotemporally-controlled morphogen gradients to ensure proper limb formation and release of individual digits. Disruption to this process can lead to a number of limb abnormalities, including syndactyly. Akirins are highly conserved nuclear proteins that are known to interact with chromatin remodelling machinery at gene enhancers. In mammals, the analogue Akirin2 is essential for embryonic development and critical for a wide variety of roles in immune function, meiosis, myogenesis and brain development. Here we report a critical role for Akirin2 in the regulation of interdigital tissue regression in the mouse limb. Knockout of Akirin2 in limb epithelium leads to a loss of interdigital cell death and an increase in cell proliferation, resulting in retention of the interdigital web and soft-tissue syndactyly. This is associated with perdurance of Fgf8 expression in the ectoderm overlying the interdigital space. Our study supports a mechanism whereby Akirin2 is required for the downregulation of Fgf8 from the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) during limb development, and implies its requirement in signalling between interdigital mesenchymal cells and the AER.

Introduction

Limb development is a complex process involving the action of specialised signalling regions that coordinate both spatially and temporally to sculpt a limb of particular shape and structure suited to a given organism. Digit formation requires the combined coordination of morphogen gradients and feedback loops that dictate responses by cells of the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), zone of polarising activity (ZPA), non-AER ectoderm, and mesenchymal cells within the limb bud1–3. During this process, proper gene expression changes are critical to ensure that cell proliferation and cell death are correctly balanced and confined spatially to the appropriate region of the developing limb bud. Such mechanisms lead to restriction in interdigital tissue growth and promote interdigital regression in order to produce defined and separated digits in both the forelimb and hindlimb. Disruption in morphogen release, receptor-mediated responses, or changes in cell proliferation and cell death can lead to many limb abnormalities, including soft-tissue syndactyly (fused/webbed digits)4–7.

Akirins are highly conserved, small nuclear proteins that have been shown to localise to promoter and enhancer regions of genes, despite a lack of apparent DNA-binding domains8,9. Current evidence suggests that Akirins function as “bridge” proteins that interact with transcription factors and chromatin remodelling machinery to coordinate a vast array of gene expression patterns. Drosophila and C. elegans have a single Akirin gene, whereas mammals have two homologues, Akirin1 and Akirin210. Complete null mutants for Akirin1 are viable and outwardly normal; however, Akirin2 null embryos were not found on embryonic (E) day 9.5, indicating that it is essential for early embryonic development11. Because of this, transgenic mouse models produced by crossing a conditional floxed allele of Akirin211 to Cre transgenics are required to selectively restrict Akirin2 deletion to discrete populations of cells in a given tissue of interest.

Recently, we identified an essential role for Akirin2 in the formation of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, utilising Emx1-Cre to excise the Akirin2 gene from the developing telencephalon12. Mutant embryos displayed near-agenesis of the cortex due to early cell-cycle exit and subsequent apoptosis of telencephalic progenitor cell and nascent neuron populations. To date, important roles have also been reported for Akirins in myogenesis, meiosis, immune function, and gene regulation in Drosophila, C. elegans, Xenopus and mammals9,13–16. Akirin2 has been shown to have an important functional role in the nucleus, acting as a bridge protein that binds to Brg1-associated factor 60 (BAF60a/b/c) and IκB-ζ to allow binding and activation of the IL-6 promoter8. Akirin2 is also important for the recruitment of the BAF complex core helicase Brg1 to Myc and Cyclin D2 promoters17. Akirin- (Drosophila) or Akirin2- (mouse) dependent genes include those whose promoters have a low number of CpG islands, consistent with an association of Akirins with chromatin remodelling machinery8,18. Additionally, Drosophila Akirin localisation corresponds with the active transcriptional mark, acetylated H3K9, further demonstrating a role in gene transcription18. Akirin has been shown to be important for muscle development in Drosophila, with mutants displaying diverse phenotypes including absent, misattached, or duplicate muscles9, and recent in vitro studies also suggest a role for Akirin2 in porcine muscle cell proliferation19. In the course of our studies12 on Akirin2 in the developing brain using Emx1-Cre, which is also active in limb epithelium20, we have uncovered in vivo evidence that Akirin2 critically regulates the regression of interdigital tissues in the developing limb bud.

Following a period of limb outgrowth that initiates with the formation of a limb bud from lateral plate mesoderm, individual digits are formed using a tightly regulated process of programmed cell death (PCD). At around embryonic day (E) 12.5 in mice, BMP2 and BMP4 released from the interdigital mesenchyme underlying the limb ectoderm activate BMP receptor/Smad signalling in the AER, a pseudostratified epithelium that rims the dorsal-ventral border of the distal limb bud21,22. The AER is an FGF-rich signalling center essential to support limb bud outgrowth; FGF8 is the only FGF continually expressed during this time, although FGF4, FGF9 and FGF17 are also expressed at various times in the AER21. Proper BMP signalling and subsequent downregulation of FGF expression initiates PCD in the interdigital mesenchyme cells, which allows for separation of individual digits between E13-E14.523.

Developmental disruption of interdigital tissue regression leads to soft tissue syndactyly (i.e., tissue fusion without bone fusion), a human congenital defect that occurs in ~1 in 2000 live births24. Syndactyly typically occurs concurrent with reduced apoptotic markers and continued proliferation of cells in the interdigital space5,7,25,26. Mechanistically, soft-tissue syndactyly appears to be caused primarily by prolonged FGF signalling, providing a cell-survival signal that allows interdigital cells to escape PCD: FGF4 overexpression in limb ectoderm leads to persistent interdigital tissue27, FGF8-soaked beads reduce the number of dying interdigital cells28, and enduring Fgf4 and Fgf8 expression is seen concurrent with soft-tissue syndactyly5,7. Prolonged FGF expression is consistently seen during experiments designed to impair BMP2/BMP4 function in the mesenchyme. For example, interdigital tissue regression is impaired when Bmp2/4 knockout is restricted to the limb bud29, when dominant-negative BMP receptors are expressed in the limb bud30, or when knockout of both Bmpr1a5 and Smad1/5 are restricted to the AER7. Overall, these results suggest that experimental loss of Smad signalling likely prevents BMP from downregulating FGFs, resulting in the continued cell proliferation and cell survival of interdigital tissue5,7.

Here, we show that Akirin2 is essential for interdigital tissue regression in the limb in vivo. Loss of Akirin2 in the limb ectoderm (using Emx1-Cre) results in a persistent soft-tissue syndactyly due to a lack of PCD and continued cell proliferation in interdigital tissues. This appears to be caused by aberrantly persistent Fgf8 expression in the AER cells adjacent to the fused digits. Our data demonstrate a previously-unsuspected role for Akirin2 in interdigital tissue regression and imply its requirement for BMP signalling and/or subsequent downregulation of Fgf8.

Results

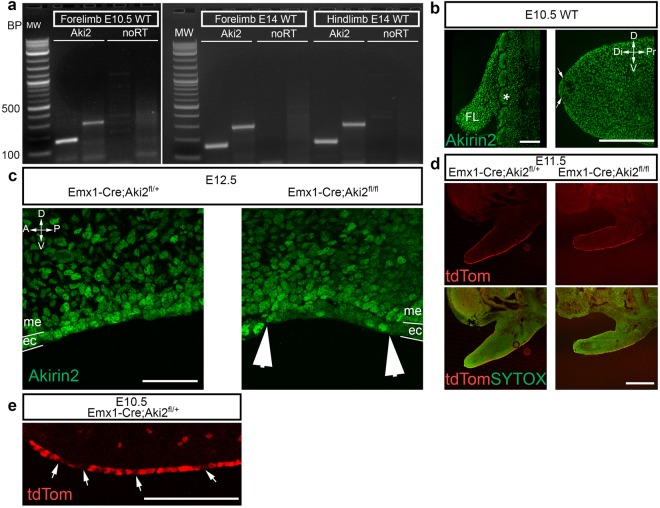

Akirin2 is expressed in the developing limb

Akirin2 expression has been reported in multiple rodent and human tissues, including heart, lung, testis, spleen, liver, intestine, placenta, ovary, thymus, kidney, muscle, blood leukocytes, and brain11,12,15. Reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR demonstrated the presence of Akirin2 transcripts in limb buds at E10.5 and E14 (Fig. 1a) and immunostaining using an Akirin2-specific antibody confirmed protein expression in the forelimb bud and somites at E10.5 (Fig. 1b), as well as robust expression in the AER (Fig. 1b, between arrows). Further staining confirmed Akirin2 protein expression in both ectodermal and mesenchymal limb bud cells at E12.5 (Fig. 1c). Emx1 is expressed in the developing limb epithelial AER20, and in the course of our studies on Akirin2 functions in cerebral cortex development12, we noted widespread, Emx1-Cre-mediated activity via a tdTomato (tdTom) reporter allele (Ai14-tdTomato) in the embryonic limb epithelium (Fig. 1d). Close examination of tdTom signal in the epithelium revealed that Cre activity was somewhat patchy, with interspersed negative cells (Fig. 1e; see also below). Demonstrating antibody specificity, in Emx1-Cre;Akirin2fl/fl (hereafter referred to as Emx-KO) limb buds, Akirin2 staining was eliminated from many cells of the epithelium, but remained unaffected in the Cre-negative interdigital mesenchyme (Fig. 1c, between arrowheads). As we reported previously12, most Emx-KO mice died shortly after birth due, presumably, to a near-complete absence of the cerebral cortex, with a small minority surviving into late adolescence.

Figure 1.

Akirin2 expression in the developing limb bud epithelium. (a) RT-PCR using two different primer sets that generate amplicons across multiple exons. Akirin2 is expressed in the limb at E10.5 and E14. (b) In wild type E10.5 cryosections, strong Akirin2 immunoreactivity is seen in the somites (denoted by *) and in the forelimb bud (FL), including expression in the AER (arrows). (c) At E12.5, Akirin2 immunostaining is lost in most cells of the ectoderm overlying the interdigital tissue of the knockout forelimb compared with control; as expected, mesodermal expression is unaffected as Cre is limited to the ectoderm. (d) Expression of a tdTom Cre reporter allele in the developing limb at E11.5 in both control and mutants, counterstained with the nuclear marker Sytox Green, shows epithelium-restricted Cre activity. (e) High magnification image of the tdTom reporter showing widespread, but patchy, expression in the ventral ectoderm of E10.5 control forelimb (arrows indicate tdTom-negative cells). Key: A, anterior; Di, distal; D, dorsal; ec, ectoderm; FL, forelimb; me, mesoderm; P, posterior; Pr, proximal; V, ventral. Scale bar: 100 μm in b; 50 μm in c; 200 μm in d; 50 μm in e.

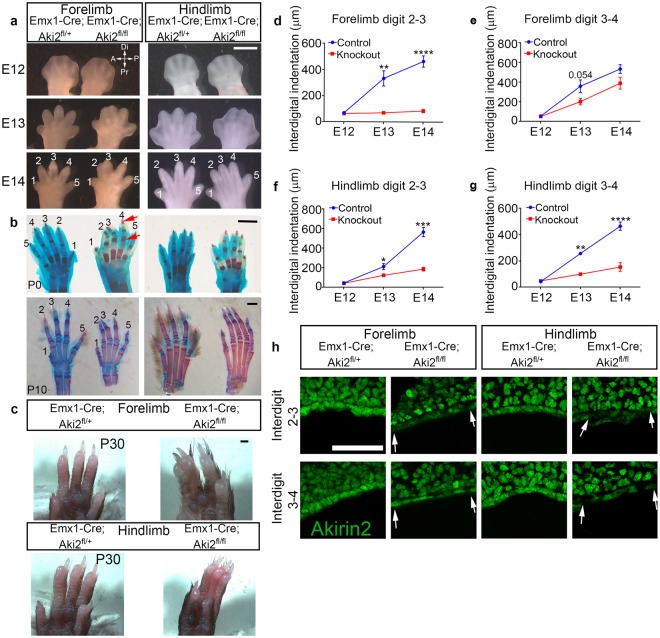

Loss of Akirin2 in limb bud epithelium leads to soft-tissue syndactyly

With complete penetrance, Emx1-Cre-restricted loss of Akirin2 from limb bud epithelia led to a syndactyly phenotype that differed between fore- and hind-limbs (Fig. 2). In the forelimb, digits 2 and 3 remained fused, while in the hindlimb, digits 2, 3 and 4 remained fused (Fig. 2a–c). To determine whether this was a soft-tissue syndactyly or bone fusion was involved, we stained limbs with Alcian Blue (cartilage) and Alizarin Red (bone) at P0 and P10 (Fig. 2b). There was no clear fusion of bone or cartilage elements; however, it was clear that interdigital tissue was retained between the adjacent digits. There also appeared to be an increased area of Alizarin Red staining in the phalanges of Emx-KO mice (red arrows, Fig. 2b), similar to that observed following Bmpr1a knockout in the AER5. Soft-tissue syndactyly was maintained into postnatal development, as the few surviving Emx-KO mice still exhibited fused digits at P10 (Fig. 2b) and P30 (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Loss of Akirin2 in the limb epithelium leads to soft-tissue syndactyly. (a) Interdigital tissue regression is impaired in Akirin2 Emx-KO forelimb (digits 2/3) and hindlimb (digits 2/3/4). (b) Alcian Blue/Alizarin Red staining at P0 and in one of the few surviving mutants at P10 shows that the Akirin2 Emx-KO limb does not have fused bone or cartilage elements, though broader Alizarin Red (bone) staining is observed in the phalanges (red arrows). (c) A very rare Akirin2 Emx-KO that survived until P30 contains clear syndactyly of the mature forelimb and hindlimb. (d–g) Quantification of interdigital tissue regression shows impaired tissue regression between digits 2–3 of the forelimb (d) and 2–4 of the hindlimb (f,g) in Akirin2 Emx-KO mice. The difference in forelimb interdigital regression between digits 3–4 approaches statistical significance (e; p = 0.054). n = 3 animals/genotype for E12 & E13; 4 animals/genotype for E14, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, t-test. (h) Immunostaining of Akirin2 Emx-KO distal limb buds at E12.5 shows that Akirin2 expression is extensively lost in the interdigital space between digits 2–3 in both fore- and hindlimb. In the forelimb, most cells between digits 3–4 remain Akirin2-positive, while in the hindlimb more Akirin2-negative cells are observed (interdigital regions indicated between arrowheads). Scale bar: 1 mm in a-c; 50 μm in h.

To track the development of this syndactyly, we quantified interdigital tissue regression in control and Emx-KO mice (Fig. 2d–g). Whereas in control forelimbs interdigital tissue steadily regressed between E12 and E14, in the forelimb of Emx-KO mutants interdigital tissue remained unchanged between digits 2–3 and was somewhat slower to regress between digits 3–4 (Fig. 2d,e). In the mutant hindlimb, interdigital tissue regression was minimal between digits 2–3 and 3–4 between E12 to E14 (Fig. 2f,g). These embryonic measurements are fully consistent with the syndactyly phenotypes observed at embryonic, perinatal, and postnatal ages (Fig. 2a–c). Previous work31 and our own observations (Fig. 1c–e) indicate that Emx1-Cre activity is widespread but patchy in the limb bud epithelium. Because Akirin2 expression is uniform in the limb epithelium (Fig. 1b,c), we thus asked whether patchy Cre activity underlies the observed differences in interdigital regression between forelimbs and hindlimbs. We immunostained cryosections from E12.5 forelimbs and hindlimbs with an Akirin2 antibody. Indeed, careful inspection of the distal limb bud tips revealed that in Emx-KO forelimbs, Akirin2 immunoreactivity is nearly completely absent from ectodermal cells between digits 2–3, but most cells retain Akirin2 between digits 3–4. In contrast, in the hindlimb, extensive Akirin2 loss was identified in the interdigital tissue between both digits 2–3 and 3–4 (Fig. 2h). This indicates that the expression of Emx1-Cre differs between forelimb and hindlimb ectoderm, and that localized loss of Akirin2 can account for the pattern of resulting syndactyly that we observe.

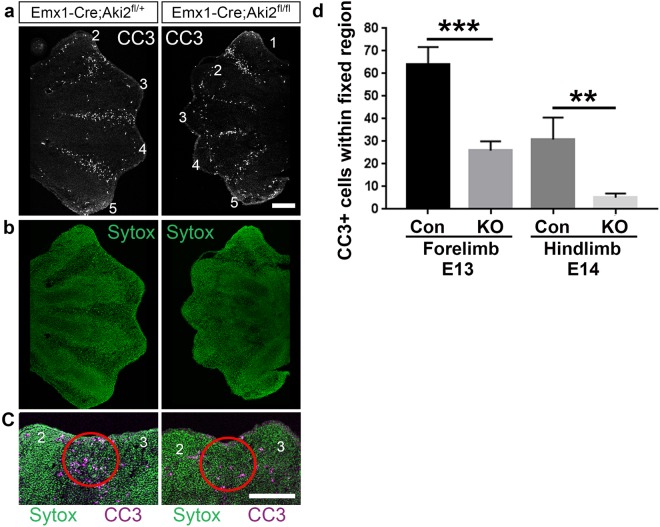

Akirin2 knockout leads to reduced PCD and continued proliferation of interdigital tissue

During normal murine limb development, cells in the interdigital tissue begin to undergo PCD around E13.5 (forelimb) and E14 (hindlimb), allowing tissue regression and the release of individual digits23. Reduced or absent cell death in the interdigital space has been shown by multiple studies to result in syndactyly5–7,25,27. We thus asked whether the disrupted regression of interdigital tissue and resultant syndactyly in Emx-KO mutants were due to impaired PCD. We stained E13 forelimb and E14 hindlimb cryostat sections with antibodies against the apoptotic marker, cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) and quantified CC3-positive cells. Indeed, reduced CC3 staining corresponded with the location of digits that displayed syndactyly (Fig. 3a,b), and this was especially apparent at the distal tip of the interdigital tissue (Fig. 3c). Quantification of CC3-positive cells in a fixed region at the distal tip of the interdigital tissue showed that it was significantly reduced in Emx-KO mice compared to controls at E13 in the forelimb and E14 in the hindlimb (hindlimb development normally lags somewhat behind forelimb3,23) (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, given the massive PCD observed in Akirin2-null neural progenitors12, no increase in CC3 staining, was observed in Akirin2-null epithelium itself (Fig. 3c). As mesenchymal limb tissue retains Akirin2 expression in Emx-KO mutants (Fig. 1c), the disruption of interdigital tissue PCD thus represented a cell-non-autonomous phenotype.

Figure 3.

Akirin2 loss in limb epithelium leads to decreased programmed cell death between digits that display syndactyly. (a) Cleaved caspase-3 staining is nearly absent between digits 2–3 in Akirin2 Emx-KO forelimb and reduced between the other digits. (b) Sytox Green cellular stain of the limb sections in (a). (c) High magnification views of the distal limb bud region between digits 2 and 3 demonstrates reduced cleaved caspase-3 staining in the Emx-KO interdigital tissue (red circle). (d) Quantification of the number of cleaved caspase-3 cells within the fixed region outlined in (c; Con = Control). Key: CC3, cleaved caspase-3; n = forelimb E13: Con 21 sections, 5 animals; KO 19 sections, 5 animals; hindlimb E14: Con 14 sections, 3 animals; KO 18 sections, 3 animals. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, t-test. Scale bar: 200 μm.

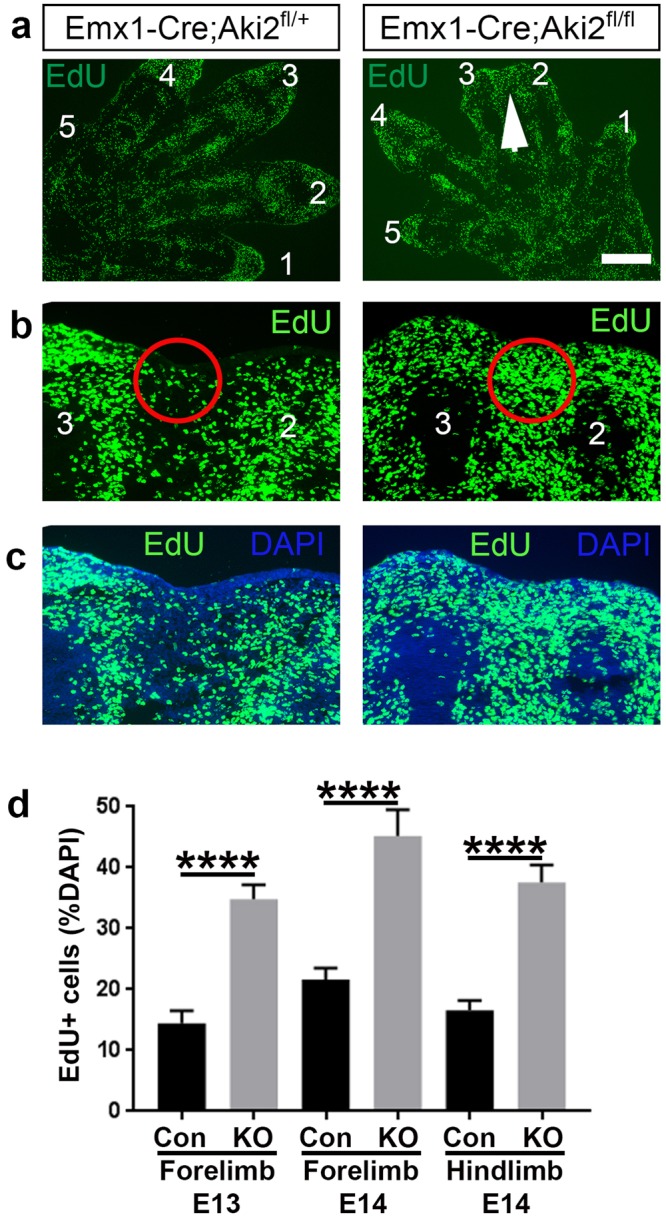

Reduced PCD suggested that there may be continued cell proliferation in the interdigital tissue of Emx-KO embryos. To investigate this, we injected the nucleotide analogue EdU into pregnant dams at E13 and E14, collected embryos 2 hours later, and stained cryostat sections for EdU uptake, indicative of cell proliferation. In the Emx-KO mutant limb, we found an increase in EdU-positive proliferating cells within the interdigital tissue; again, this was especially apparent at the distal tip (Fig. 4a–c). The region of the limb with increased numbers of proliferative cells coincided well with the observation of syndactyly (Fig. 4a). At E13 in the forelimb, and at E14 in both the forelimb and hindlimb (Fig. 4d), interdigital tissue contained significantly higher densities of EdU-positive cells (normalised to total cell numbers). Together, these data indicate that the syndactyly phenotype in Emx-KO mice is caused by aberrant continued survival and proliferation of interdigital tissues.

Figure 4.

Akirin2 loss in limb epithelium leads to increased cell proliferation between digits that display syndactyly. (a–c) Immunohistochemistry of EdU with DAPI counterstain shows increased EdU-positive cell density at the distal end of the limb at E13 and E14 (a, low magnification, white arrowhead; and b,c, high magnification, red circles; digits are numbered). (d) Quantification of percent DAPI-positive cells that are also EdU-positive in control and Akirin2 Emx-KO in the E13 forelimb and E14 forelimb and hindlimb. Cell counts were made in the distal interdigital areas, shown outlined by the red circles. n = forelimb E13: Con 21 sections, 3 animals; KO 25 sections, 4 animals; forelimb E14: Con 17 sections, 3 animals; KO 18 sections from 3 animals; hindlimb E14: Con 18 sections, 3 animals; KO 18 sections, 3 animals. ****p < 0.0001, t-test. Scale bar (in a): 300 μm in a; 100 μm in b,c.

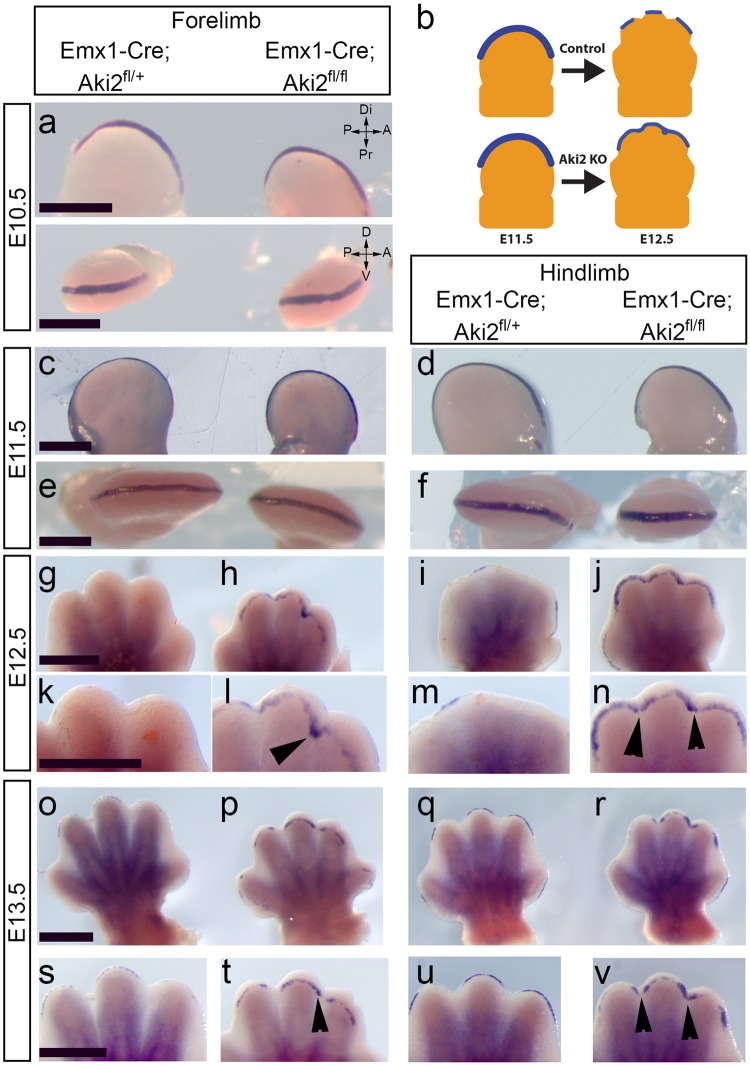

Aberrantly retained Fgf8 signal in Akirin2 knockout interdigital ectoderm

The initiation of interdigital tissue regression is thought to involve BMP ligand release from the mesenchyme underlying the AER, and subsequent attenuation of FGF8 signalling within the AER5. Because Emx-KO embryos lack Akirin2 in the limb epithelium (including the AER), but not the mesenchyme, we reasoned that FGF8 loss in the AER might be disrupted. Whole mount in situ hybridisation for Fgf8 showed clear differences in expression between control and mutant forelimbs and hindlimbs (Fig. 5). Between E10.5 and E11.5, we found no apparent difference in the extent or intensity of Fgf8 signal between controls and mutants (Fig. 5a–f). From E12.5 on, however, it became clear that Fgf8 signal aberrantly perdured in the AER overlying the interdigital mesenchyme in Emx-KO forelimb and hindlimb (Fig. 5g–j and o-r, low magnification images; Fig. 5k–n and s-v, higher magnification images). The regions of the AER in which Fgf8 signal was aberrantly retained corresponds exactly with where reduced PCD and increased cell proliferation were observed in the underlying mesenchyme (Figs 3, 4). We also performed quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) analysis of E12.5 forelimbs, investigating the expression of an array of genes that are known to influence interdigital development (Supplementary Fig. S1). We found no significant difference in the expression levels of any genes examined, which suggests that Akirin2 may act directly on the expression of Fgf8 at a chromatin level, rather than by affecting BMP receptor expression or by affecting (cell non-autonomously) mesenchymal release of BMPs. We conclude that Akirin2 is required in the developing limb bud epithelium for the downregulation of Fgf8 that triggers interdigital tissue regression and the separation of digits.

Figure 5.

Fgf8 expression is aberrantly retained in Akirin2 knockout limb epithelium. Whole mount in situ hybridisation using Fgf8 riboprobes comparing control and Akirin2 Emx-KO limb at E10.5 (a), E11.5 (c–f), E12.5 (g–n) and E13 (o–v). Fgf8 signal is retained in the Akirin2 Emx-KO limb distal epithelia in the regions that display syndactyly from E12.5 onwards (g–v): digits 2–3 in forelimb and digits 2–4 in hindlimb (black arrowheads). Insets at E12.5 (k–n) and E13 (s–v) show higher magnification images of the distal limb. Panel (b) is a schematic showing the KO phenotype of perduring Fgf8 expression (blue). Key: A, anterior; D, dorsal; Di, distal; P, posterior; Pr, proximal; V, ventral. Scale bar: 500 μm in each row.

Discussion

In this study we restricted Akirin2 gene knockout to the limb ectoderm using Emx1-Cre, and demonstrated a role for Akirin2 in interdigital tissue regression for the first time, identifying a novel nuclear effector within the ectoderm that is critical for this process. Akirin2 is expressed throughout the developing limb bud, in both ectoderm and mesoderm, and loss of Akirin2 from the ectoderm leads to soft-tissue syndactyly. This is due to reduced PCD and enduring cell proliferation in the relevant digits, and continued Fgf8 expression in these digits beyond its normal physiological timeframe.

Recent studies propose a model of interdigital web regression whereby BMP2/4 release from the interdigital region of the limb activates BMPR1a in the AER, which signals through Smads, resulting in downregulation of FGF8. The importance of BMPs is shown by studies in which high levels of the BMP-inhibitor, Gremlin, were reported in the interdigital tissue of naturally-occurring webbed limbs such as the bat wing32 and duck hindlimb33 during development. BMP signalling thus contributes to removal of the cell survival signal (i.e., FGF8) for interdigital mesenchymal cells and leads to PCD5. In this study, we showed reduced PCD and increased proliferation in the interdigital tissue of Emx-KO limbs, similar to previous reports of syndactyly phenotypes7,34, implying the survival of interdigital cells that are normally fated to die. Alterations in the balance of PCD and cell proliferation in the interdigital tissue have been linked to syndactyly, and interdigital mesenchyme cell survival has been repeatedly linked to retention of FGF expression in the AER. More specifically, when FGF8 is not appropriately downregulated at the onset of interdigital web regression, syndactylies occur5,7,25. Impaired BMP signalling in syndactyly models is observed concurrent with enduring FGF8 expression within a persistent AER, which in normal limbs is progressively lost via PCD starting at E12.5, initially at the interdigit and then at the tips of the digits35. We demonstrated that Fgf8 remains high specifically in the ectoderm overlying the interdigital spaces of fused digits in Emx-KO mutant mice.

Interestingly, at E11.5 there was no large expansion of the AER in the dorsal-ventral axis, unlike that found in previous work that impaired BMP or Smad signalling5,6,25, suggesting that AER maturation occurred normally in the absence of Akirin2. Furthermore, using qPCR of forelimbs at E12.5, we did not detect any change in multiple Bmps, Fgf4, their receptors, or other genes known to influence web regression. It should be recalled that these qPCR results are from whole limb buds, and thus provide an overview of gene expression in the (wild-type) mesenchyme and (Akirin2-null) ectoderm combined. However, we also appreciate the limitations of such an approach. Specifically, any localized changes that may have occurred within the ectoderm of Emx-KO mutants are unlikely to have been detected. Nevertheless, as Bmps are expressed highly in the mesenchymal limb tissue, which made up the majority of the cDNA samples analyzed in our assay, we would likely have been able to detect changes in Bmp gene expression in Emx-KO, had any occurred. A number of observations in this study suggest that the role of Akirin2 in the ectoderm is to aid in the downregulation of Fgf8 at the onset of interdigital regression: 1) we detected no changes in Bmp or Shh gene expression in E12.5 mutant limbs; 2) the Fgf8 expression field is only different between control and mutants at the timepoint when it normally diminishes (i.e. E12.5); and 3) in this model Akirin2 is knocked out only in the ectoderm, so cannot have a cell-autonomous effect on interdigital mesenchymal cells. Our results also further strengthen the hypothesis that FGF8 loss is the primary signal that induces interdigital web regression4,5,28. We have, however, not yet provided evidence that Akirin2 directly regulates FGF8 expression, either by binding to the Fgf8 promoter/enhancer, or by altering upstream effectors. Future studies, for example utilising chromatin immunoprecipitation with an appropriate Akirin2 antibody, will be important for elucidating the role of Akirin2 in the nucleus of ectoderm cells during interdigital regression.

The most well-established mechanism leading to syndactyly proposes that the activation of BMPR1a and Smad signalling in the AER are likely to initiate interdigital tissue regression5,7,36. To support this, a dominant negative form of BMPR1a expressed in the limb bud inhibited PCD in the interdigital tissue30 and BMPR1a conditional knockout in the AER caused retained Fgf8 signal, reduced PCD and syndactyly5. In addition, the overexpression of BMP inhibitors Noggin36 and Gremlin33 severely reduce PCD in the interdigital tissue of limbs, and ectopic expression of Noggin in the AER to inhibit AER-BMPs leads to syndactyly and expansion of the Fgf8 expression domain6. Furthermore, the double-inactivation of Smad1/Smad5 from the AER during limb development caused impaired web regression and resulted in syndactyly, likely due to the inability to transmit BMP2/4 signals to the nucleus7. Despite this progress, the precise nuclear events that surround this proposed role at the chromatin level are currently unclear.

Smads are DNA-binding molecules that can activate or inhibit gene expression and have roles throughout embryonic development. Canonical BMP signalling functions through the activation of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8, which subsequently interacts with Smad4, and this complex alters gene expression in the nucleus (for detailed review, see37). Due to the relatively weak affinity that Smads have for DNA, additional proteins such as DNA-binding factors, coactivators and corepressors are required and recruited to promoter sites to strengthen interactions and thus change gene expression37. Thus, a possible role for Akirin2 during interdigital regression is via the organisation and dynamic remodelling of chromatin during Smad signalling in the ectoderm.

Analysis of the Fgf8 gene has found that the promoter region contains both NFκB and retinoic acid receptor (RAR) binding elements (RAREs)38,39. The interaction of Akirin2 with NFκB signalling systems is currently its most well-documented8,11,18; however, to date there is limited information about the role of NFκB in syndactyly. Interestingly, a comparative proteomics study that assessed expression profiles of E12.5 and E13.5 hindlimb interdigital tissue found upregulation of protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and downregulation of peroxiredoxin-1 (Prdx1) at a stage where interdigital cells are irreversibly committed to PCD40. Subsequent transfection of siRNA against Prdx1 into interdigital cells in culture found upregulation of NFκB, and the authors suggest that this is a response to high levels of reactive oxygen species in the interdigital cells at that stage of development. However, here we removed Akirin2 from the ectoderm and not the interdigital mesenchyme cells, which retain Akirin2 protein expression (Fig. 1c); thus our results do not support an interaction between Akirin2 and NFκB signalling as the cause of the syndactyly that we observe.

RARs have been shown to suppress Fgf8 expression in various tissues, including ectoderm39,41. In addition, retinoic acid-soaked beads transplanted into the anterior heart field of chick embryos strongly downregulated the expression of Fgf842. Our results indicate that Akirin2 is important for the repression of the Fgf8 gene. Given the presence of RAREs in the Fgf8 promoter39, one possible mechanism of Akirin2 function in the ectoderm would be interaction with RARs. Retinoic acid may act to limit the spread of Fgf8 to a restricted zone during limb bud initiation (~E9.5)43, though loss of retinoic acid in the limb bud does not alter the Fgf8 expression field at E10.544. Nevertheless, limbs lacking retinoic acid later exhibit interdigital webbing44, and compound mutants of RARα/RARγ exhibit syndactyly45. Together, these phenotypes are consistent with what we observe in Akirin2 mutants: normal limb patterning; lack of change in Bmp2/4; and no dorsal-ventral expansion of the Fgf8 expression field at E10.5 and E11.5. It is important to note; however, that retinoic acid-soaked mouse limb buds were shown to have unaltered Fgf8 expression28 and mouse hindlimbs that were examined following retinoic acid loss via Raldh2 knockout also display no change in Fgf8 at E13.546. These last two results are inconsistent with what we observe with our Akirin2 Emx-KO mice, and thus make the interaction between Akirin2 and RARs an unlikely mechanism for Akirin2-mediated interdigital tissue regression.

This study is the first to identify a role for Akirin2 in mammalian limb development. In limbs lacking Akirin2 in the ectoderm, we show that interdigital PCD fails and mesenchymal cells continue to proliferate, causing soft-tissue syndactyly due to retained FGF8 expression. Future work will address the protein-protein interactions of Akirin2 in limb epithelium and the specific chromatin remodelling mechanisms that are important for the downregulation of FGF8 during limb development.

Methods

Antibodies

Antibodies used in this manuscript are as follows: Abcam: Akirin2 (ab221475) 1:200. Cell Signaling Technology: Cleaved caspase-3 (#9661) 1:100. Clontech: DsRed (632496) 1:500. Roche: anti-digoxigenin-AP Fab fragments (11093274910) 1:2000.

Generation of knockout mice

Details of the Emx1-Cre mice used for this manuscript are available in our previous study using floxed Akirin2 knockouts12. Briefly, floxed Akirin2 conditional mutant mice11 were crossed with a line expressing Cre from the Emx-1 locus47 to excise the floxed Akirin2 allele. We also crossed a tdTomato reporter, Ai14-tdTomato into this line, which contains a floxed stop cassette preceding the tdTomato gene in the ROSA26 locus. All lines were congenic to C57BL/6 and animal experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the University of Iowa’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and NIH guidelines. These mice are designated as Emx-KO in the manuscript and Emx1-Cre;Aki2fl/fl in the figures, compared with Emx1-Cre;Aki2fl/+ designated as heterozygote controls. Heterozygotes showed no obvious abnormalities and appear to develop as wild-type animals do.

RT-PCR and qPCR

Limb buds were dissected from mice at E10.5 or E14 and placed into TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA was extracted following manufacturer’s protocol and RNA cleanup was performed using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini kit. RNA was converted to cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) and PCR was performed using primers designed across multiple exons and exon-exon boundaries for mouse Akirin 2 (reported previously in12). Akirin 2 - Exon 1- Exon 2 F 5′-CGC CTC GCC GCA GAA GTA TC-3′, R 5′-CAA CCT GGA TCT GCC TGC TGA AA-3′; Exon2/3 junction-Exon 5 F 5′-GCA TCA CCA GGG ACT TCA TCT-3′, R 5′-ACA AAG AAC AAG GCA GCC CA-3′. PCR cycling parameters for 30 cycles were: 95 °C 1 minute, 55 °C 15 seconds, 72 °C 1 minute.

For qPCR experiments, forelimbs were dissected from embryos collected at E12.5 and placed into RNAlater® (Ambion). RNA was extracted using the miRVANA RNA extraction kit (Invitrogen) and cDNA was prepared using the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Control and Akirin2 Emx-KO RNA was assessed for quantity using SYBR green chemistry (Roche) in a Roche LightCycler® 480 Real-Time PCR system and normalised to β-actin levels. BMP2, BMP4 and sonic hedgehog (Shh) primers were published previously48. Connexin-43 primers: F 5′-CTTTCATTGGGGGAAAGGCG-3′, R 5′-CTGGGCACCTCTCTTTCACTT-3′. Twist1 primers were previously reported in49. All other primers used for qPCR were found using the PrimerBank database50–52 with the following PrimerBank IDs: Runx2, 6063419a1; Bmpr1a, 538363a1; Grem1, 215490119c1; Fgf4, 158508679c3; Fgfr2, 198594a1; En1, 7106305a1; Gli3, 120953172c1.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were collected between embryonic days E10.5–E14. Embryos were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours and forelimbs and hindlimbs were dissected. Samples were washed with PBS and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose, frozen in OCT and 12–18 μm cryosections were cut. Sections were blocked (2.5% BSA, 0.1% Triton-X100) for 1 hour and incubated with primary antibody diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. Sections were washed with PBS and incubated in the relevant secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa-Fluor 488 nm, 568 nm or 647 nm (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) for 2 hours at RT, washed with PBS and counter-stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and/or SYTOX® green nucleic acid stain (Molecular probes/Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific), prior to mounting with Fluoro-Gel mounting media (Electron Microscopy Services #17985-11).

Interdigital indentation

Side-by-side images of control and Emx-KO paws were made (16x, Zeiss SteREO Discovery.V12 microscope and captured using AxioVision Rel4.8) and interdigital indentation analysis was performed according to previously published methods53. Briefly, a circle was drawn around each paw to best fit around digits 2–5 and a radius line drawn from the center to the outside of the circle through the interdigital web. The distance from the edge of the circle to the interdigital web (in μm) was recorded as the distance regressed. Data were collected from interdigital spaces between digits 2–3 and 3–4, with a minimum of 3 animals per genotype for each age recorded.

Alcian Blue/Alizarin Red staining

Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red staining for gross skeletal analysis was performed on P0 and P10 Emx-KO mice (plus littermate controls) according to previously reported detailed methodology54,55. Briefly, mice were euthanised according to institutional IACUC protocols, skin and organs were removed, and remaining tissue fixed in several changes of 95% ethanol for up to one week. Specimens were then treated in several changes of 100% acetone for up to one week followed by staining with Alcian Blue up to 8 hours. Samples were subjected to a second round of fixation in 95% ethanol and soft tissue digestion and specimen clearing was done in 1% potassium hydroxide, up to 4 hours while monitoring for signs of disarticulation. Specimens were then exposed to freshly prepared Alizarin Red S. for up to 16 hours and stored in 100% glycerol.

EdU injections

Pregnant dams were injected intraperitoneally at E13 or E14 with EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine, Invitrogen) at a concentration of 100 μg/g, 2 hours prior to embryo collection. EdU labelling was detected using the Click-iT® EdU Alexa Fluor® 488 imaging kit (Molecular probes, Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific), following manufacturer’s instructions.

Whole mount in situ hybridisation

Standard whole mount in situ hybridisation was performed using methods modified from56. Fixed limb tissue was dehydrated using increasing methanol concentrations (25%, 50%, 75%, 100%) and rehydrated using the same descending methanol concentrations. Samples were washed using PBS + 0.1% Triton-x100 (Tx100), digested at RT using Proteinase K, washed in PBS + 0.1% Tx100, fixed using 4% PFA, washed in PBS + 0.1% Tx100 and placed in hybridisation solution (50% formamide, 50% 2x SSC, 6% dextran sulfate) overnight at 70 °C. Probes were diluted with salmon sperm DNA, heated to 85 °C and placed in fresh hybridisation solution with the samples overnight at 70 °C. Stringency washes were performed using 2x SSC at 65 °C, and samples were washed using PBS + 0.1% Tx100 with RNase A for 60 min at 37 °C. Further washes, blocking and primary antibody incubation was performed using the Roche DIG wash and block buffer set and anti-digoxigenin-AP antibody incubation overnight. Following antibody incubation, the tissue was extensively washed, incubated at RT in alkaline buffer (100 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.5), 50 mM MgCl2, 1% Tween20) for 10 min and the colour reaction observed using NBT (nitro blue tetrazolium) and BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate) until sufficient colour had developed. The Fgf8 antisense probe was a kind gift from Dr. Bernd Fritzsch, Dept. of Biology, University of Iowa, previously described53,57.

Imaging

Confocal and epifluorescence imaging was conducted using a Leica SPE DM2500 Confocal Microscope and Leica Application Suite software. In situ hybridisation and whole mount imaging was conducted using a Zeiss SteREO Discovery.V12 microscope and captured using AxioVision Rel4.8. Images were adjusted for brightness and contrast using FIJI58,59 or Adobe Photoshop. Alcian Blue/Alizarin Red stained skeleton preparations were photographed in 100% glycerol using a Leica M205 FA stereoscope equipped with a Leica DFC340 FX camera.

Analysis

For EdU and CC3 quantification, a region of interest was drawn in the distal interdigital space, corresponding to the area of increased EdU-positive cells in Emx-KO mutants or CC3 in controls. Images were thresholded using Image/J-FIJI58,59 and cells counted in each section. EdU and DAPI cells were counted individually from 4–6 sections per animal for each genotype, for both forelimbs and hindlimbs. At least 3 animals per genotype per age were analysed. For all quantification, unpaired t-tests (Prism software, GraphPad) were used to compare between control and knockout, with significance level p < 0.05.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank: Drs Osamu Takeuchi and Sarang Tartey for the Akirin2 floxed mouse line; Dr. Diane Slusarski and Trudi Westfall for the use of equipment; and Dr. Bernd Fritzsch and Jennifer Kersigo for providing plasmids and protocols used in this work. This study was supported by grants from the University of Iowa Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development and from the Iowa Neuroscience Institute.

Author Contributions

P.J.B. and J.A.W. designed the study; P.J.B. and L.C.F. performed the experiments; P.J.B. and L.C.F. collected tissues; P.J.B. and J.A.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30801-2.

References

- 1.Capdevila J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Patterning mechanisms controlling vertebrate limb development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:87–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verheyden JM, Sun X. An Fgf/Gremlin inhibitory feedback loop triggers termination of limb bud outgrowth. Nature. 2008;454:638–641. doi: 10.1038/nature07085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeller R, Lopez-Rios J, Zuniga A. Vertebrate limb bud development: moving towards integrative analysis of organogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nrg2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Martinez R, Covarrubias L. Interdigital cell death function and regulation: new insights on an old programmed cell death model. Dev Growth Differ. 2011;53:245–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2010.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pajni-Underwood S, et al. BMP signals control limb bud interdigital programmed cell death by regulating FGF signaling. Development. 2007;134:2359–2368. doi: 10.1242/dev.001677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang CK, et al. Function of BMPs in the apical ectoderm of the developing mouse limb. Dev Biol. 2004;269:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong YL, Behringer RR, Kwan KM. Smad1/Smad5 signaling in limb ectoderm functions redundantly and is required for interdigital programmed cell death. Dev Biol. 2012;363:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tartey S, et al. Akirin2 is critical for inducing inflammatory genes by bridging IkappaB-zeta and the SWI/SNF complex. Embo j. 2014;33:2332–2348. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak SJ, et al. Akirin links twist-regulated transcription with the Brahma chromatin remodeling complex during embryogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macqueen DJ, Johnston IA. Evolution of the multifaceted eukaryotic akirin gene family. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goto A, et al. Akirins are highly conserved nuclear proteins required for NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression in drosophila and mice. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:97–104. doi: 10.1038/ni1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosch PJ, Fuller LC, Sleeth CM, Weiner JA. Akirin2 is essential for the formation of the cerebral cortex. Neural Dev. 2016;11:21. doi: 10.1186/s13064-016-0076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemons AM, et al. akirin is required for diakinesis bivalent structure and synaptonemal complex disassembly at meiotic prophase I. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1053–1067. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e12-11-0841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tartey S, Takeuchi O. Chromatin Remodeling and Transcriptional Control in Innate Immunity: Emergence of Akirin2 as a Novel Player. Biomolecules. 2015;5:1618–1633. doi: 10.3390/biom5031618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komiya Y, et al. A novel binding factor of 14-3-3beta functions as a transcriptional repressor and promotes anchorage-independent growth, tumorigenicity, and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18753–18764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, et al. Dual roles of Akirin2 protein during Xenopus neural development. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:5676–5684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.777110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tartey S, et al. Essential Function for the Nuclear Protein Akirin2 in B Cell Activation and Humoral Immune Responses. J Immunol. 2015;195:519–527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnay F, et al. Akirin specifies NF-kappaB selectivity of Drosophila innate immune response via chromatin remodeling. Embo j. 2014;33:2349–2362. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, et al. Akirin2 regulates proliferation and differentiation of porcine skeletal muscle satellite cells via ERK1/2 and NFATc1 signaling pathways. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45156. doi: 10.1038/srep45156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briata P, et al. EMX1 homeoprotein is expressed in cell nuclei of the developing cerebral cortex and in the axons of the olfactory sensory neurons. Mech Dev. 1996;57:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewandoski M, Sun X, Martin GR. Fgf8 signalling from the AER is essential for normal limb development. Nat Genet. 2000;26:460–463. doi: 10.1038/82609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun X, Mariani FV, Martin GR. Functions of FGF signalling from the apical ectodermal ridge in limb development. Nature. 2002;418:501–508. doi: 10.1038/nature00902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez-Teran MA, Hinchliffe JR, Ros MA. Birth and death of cells in limb development: a mapping study. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2521–2537. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flatt AE. Webbed fingers. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005;18:26–37. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maatouk DM, Choi KS, Bouldin CM, Harfe BD. In the limb AER Bmp2 and Bmp4 are required for dorsal-ventral patterning and interdigital cell death but not limb outgrowth. Dev Biol. 2009;327:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dubail J, et al. A new Adamts9 conditional mouse allele identifies its non-redundant role in interdigital web regression. Genesis. 2014;52:702–712. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu P, Minowada G, Martin GR. Increasing Fgf4 expression in the mouse limb bud causes polysyndactyly and rescues the skeletal defects that result from loss of Fgf8 function. Development. 2006;133:33–42. doi: 10.1242/dev.02172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez-Martinez R, Castro-Obregon S, Covarrubias L. Progressive interdigital cell death: regulation by the antagonistic interaction between fibroblast growth factor 8 and retinoic acid. Development. 2009;136:3669–3678. doi: 10.1242/dev.041954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandyopadhyay A, et al. Genetic analysis of the roles of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 in limb patterning and skeletogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokouchi Y, et al. BMP-2/-4 mediate programmed cell death in chicken limb buds. Development. 1996;122:3725–3734. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin XL, et al. Emx1-specific expression of foreign genes using “knock-in” approach. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:978–982. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weatherbee SD, Behringer RR, Rasweiler JJ. t. & Niswander, L. A. Interdigital webbing retention in bat wings illustrates genetic changes underlying amniote limb diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15103–15107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604934103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merino R, et al. The BMP antagonist Gremlin regulates outgrowth, chondrogenesis and programmed cell death in the developing limb. Development. 1999;126:5515–5522. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCulloch DR, et al. ADAMTS metalloproteases generate active versican fragments that regulate interdigital web regression. Dev Cell. 2009;17:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Q, Loomis C, Joyner AL. Fate map of mouse ventral limb ectoderm and the apical ectodermal ridge. Dev Biol. 2003;264:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guha U, et al. In vivo evidence that BMP signaling is necessary for apoptosis in the mouse limb. Dev Biol. 2002;249:108–120. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaarenstroom T, Hill CS. TGF-beta signaling to chromatin: how Smads regulate transcription during self-renewal and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;32:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong K, Robson CN, Leung HY. NF-kappaB activation upregulates fibroblast growth factor 8 expression in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2006;66:1223–1234. doi: 10.1002/pros.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S, Duester G. Retinoic acid controls body axis extension by directly repressing Fgf8 transcription. Development. 2014;141:2972–2977. doi: 10.1242/dev.112367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shan SW, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis identifies protein disulfide isomerase and peroxiredoxin 1 as new players involved in embryonic interdigital cell death. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:266–281. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janesick A, Shiotsugu J, Taketani M, Blumberg B. RIPPLY3 is a retinoic acid-inducible repressor required for setting the borders of the pre-placodal ectoderm. Development. 2012;139:1213–1224. doi: 10.1242/dev.071456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narematsu, M. et al. Impaired development of left anterior heart field by ectopic retinoic acid causes transposition of the great arteries. J Am Heart Assoc4, 10.1161/jaha.115.001889 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Lewandoski M, Mackem S. Limb development: the rise and fall of retinoic acid. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R558–561. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham TJ, et al. Rdh10 mutants deficient in limb field retinoic acid signaling exhibit normal limb patterning but display interdigital webbing. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1142–1150. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kastner P, et al. Genetic evidence that the retinoid signal is transduced by heterodimeric RXR/RAR functional units during mouse development. Development. 1997;124:313–326. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao X, Brade T, Cunningham TJ, Duester G. Retinoic acid controls expression of tissue remodeling genes Hmgn1 and Fgf18 at the digit-interdigit junction. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:665–671. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorski, J. A. et al. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1-expressing lineage. J Neurosci22, 6309–6314, 20026564 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Norrie JL, et al. Dynamics of BMP signaling in limb bud mesenchyme and polydactyly. Dev Biol. 2014;393:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang ZH, et al. Ovol2 gene inhibits the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in lung adenocarcinoma by transcriptionally repressing Twist1. Gene. 2017;600:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spandidos A, et al. A comprehensive collection of experimentally validated primers for Polymerase Chain Reaction quantitation of murine transcript abundance. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:633. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spandidos A, Wang X, Wang H, Seed B. PrimerBank: a resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D792–799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, Seed B. A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang T, Bassuk AG, Fritzsch B. Prickle1 stunts limb growth through alteration of cell polarity and gene expression. Dev Dyn. 2013;242:1293–1306. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rigueur D, Lyons KM. Whole-mount skeletal staining. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1130:113–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-989-5_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McLeod MJ. Differential staining of cartilage and bone in whole mouse fetuses by alcian blue and alizarin red S. Teratology. 1980;22:299–301. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420220306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hargrave M, Bowles J, Koopman P. In situ hybridization of whole-mount embryos. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;326:103–113. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-007-3:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heikinheimo M, et al. Fgf-8 expression in the post-gastrulation mouse suggests roles in the development of the face, limbs and central nervous system. Mech Dev. 1994;48:129–138. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.