Abstract

Rationale: It has been reported that peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPARγ) level decreases significantly in the brains of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and mice models, while the mechanism is unclear. This study aims to unravel the mechanism that amyloid β (Aβ) decreases PPARγ and attempted to discover lead compound that preserves PPARγ.

Methods: In APP/PS1 transgenic mice and Aβ treated microglia, the interaction between HSP90 and PPARγ were analyzed by western blot. Using a PPRE (PPARγ responsive element) containing reporter cell line, compounds that activate PPARγ activity were identified. After genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition of potential target pathways, the target of jujuboside A (JuA) was discovered through Axl/HSP90β. After oral administration or intrathecal injection, the anti-AD activity of JuA was evaluated by Morris water maze (MWM) test and object recognition test. Soluble Aβ42 levels and plaque numbers after JuA treatment were detected by thioflavin S staining, and the activation of microglia was assayed by immunofluorescence staining against Iba-1.

Results: We found that Aβ stress decreased heat shock protein 90 β (HSP90β), subsequently reduced the abundance of PPARγ, and down-regulated Aβ clearance-related genes in BV2 cells and primary microglia. We identified that JuA stimulated the expression of HSP90β, strengthened the interaction between HSP90β and PPARγ, preserved PPARγ levels, and thus effectively promoted the clearance of Aβ42. We demonstrated that JuA increased HSP90β expression through Axl/ERK pathway. JuA significantly ameliorated cognitive deficiency in APP/PS1 transgenic mice, meanwhile, JuA significantly reduced the soluble Aβ42 levels and plaque numbers in the brain. Notably, the therapeutic effects of JuA were dampened by R428, an Axl inhibitor.

Conclusions: This study suggests that the up-regulation of HSP90β by JuA through Axl is a potential therapeutic strategy to facilitate Aβ42 clearance and ameliorate cognitive deficiency in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid β, Jujuboside A, PPARγ, HSP90β, Axl

Introduction

Accumulation of senile plaques in brain tissue is one of the main pathological features of AD 1. Aβ42 is the primary component of the senile plaques 2, which induces a series of pathological changes including chronic inflammatory reaction, oxidative injury, tangles formation and progressive synaptic injury 3, 4. Despite significant efforts to develop treatments, the field has seen little success, partially due to an incomplete understanding of the mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis 5. Aβ deposition could start years or even decades before the appearance of dementia symptoms 6. Notably, late onsets AD patients exhibit compromised Aβ clearance rather than over production of Aβ 7, and thus promoting Aβ clearance becomes an attractive strategy in AD treatment.

Microglia are the only type of resident macrophages in the central nervous system (CNS) 8, 9. Activated microglia uptake soluble or fibrillar Aβ and degrade these peptides through proteasome pathways 10, 11. The abnormal increase of soluble Aβ level could be attributed to either increased Aβ production or decreased Aβ clearance, in many cases, both 4, 12. Microglia lose their phagocytic activity gradually during the progression of AD 13, 14, and this process is also highly sensitive to inflammatory stimuli 15, 16. Emerging evidences suggest that PPARγ effectively regulates the activation of microglia under physiological and pathological conditions, and is recognized as a therapeutic target for AD 17, 18. Firstly, PPARγ activation enhances microglia phagocytosis of soluble Aβ and insoluble deposits 9, 19. Secondly, PPARγ induces the expression of ApoE, ABCA1 and ABCG1; hence, it increases lipidated ApoE levels and facilitates the degradation of soluble Aβ peptides by microglia 9, 12, 19. It is worth noting that in the brains of APPV717I transgenic mice and AD patients, the PPARγ level decreases significantly 20. As a consequence, Aβ clearance capacity decreases and the progression of AD is subsequently exacerbated. However, the mechanism of how PPARγ is decreased in AD patients remains largely elusive.

HSP90 is an evolutionarily conserved molecular chaperone that is essential for the folding, maturation and stability of several hundreds of client proteins, including thermodynamically unstable proteins, kinases and nuclear receptors. In aged individuals, the damaged proteins accumulate, which leads to an increase in chaperone occupancy. The function and content of HSP90 were found to be greatly impaired in old animals 21, as well as in patients with early or late onset AD or mild cognitive impairment 22. In AD animal models, overexpression of molecular chaperones, including HSP90, suppresses the early stages of self-assembly 23, 24, and thus pharmacological activation of chaperones might have a favorable therapeutic effect on AD. It has been reported that, under stressed conditions, or when HSP90 function is blocked, PPARγ is depleted in the detergent-soluble fraction and sediments in the detergent-insoluble pellets, which leads to loss of its proper structure and function in 3T3-L1 cells 25, 26. However, the relationship between AD progression and HSP90/PPARγ has not been completely elucidated in neurodegenerative diseases.

Given the facts above, we hypothesized that chronic Aβ exposure leads to HSP90 function impairment, which inactivates PPARγ and decreases Aβ clearance capacity in microglia. Compounds that promote the expression of HSP90 in microglia revive PPARγ activity, as well as Aβ clearance capacity, and thus delay the progression of AD.

Jujuboside A (JuA) is a triterpene saponin isolated from Semen Ziziphi Spinosae. JuA has been reported to have several biological activities including anti-oxidant, anti-inflammation, anti-apoptosis and neuro-protection 27-29. In the present study, we demonstrated that JuA significantly restored the content and function of PPARγ in BV2 cells and primary microglia through enhancing the expression of HSP90β. JuA treatment effectively promoted Aβ42 clearance by microglia and ameliorated cognitive deficiency in AD mice models. In addition, we identified that JuA upregulated the expression of HSP90β, at least in part, due to activating ERK through Axl receptor tyrosine kinase.

Methods

Reagents

Human Aβ42 peptides were purchased from ChinaPeptides (Suzhou, China). Mouse non-target control siRNA (sc-37007), HSP90β siRNA (sc-35607), HSP90α siRNA (sc-35609), Axl siRNA (sc-29770) were purchased from Santa Cruz (Dallas, USA). Jujuboside A (A0274) was purchased from Must Biological Technology Co. Ltd. (Chengdu, China). GW9662 (S2915), Rosiglitazone (S2556) was purchased from Selleck (Houston, USA). SCH772984 (HY-50846), Dovitinib (HY-50905), Gefitinib (HY-50895), Sunitinib (HY-10255A), LDC1267 (HY-12494), UNC2250 (HY-15797), R428 (HY-15150), CHIR-99021(HY-10182) were purchased from MedChem Express (Shanghai, China). Stock solution of all drugs were made with DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and diluted in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) to final concentrations in cell experiments, or diluted in saline for animal treatment. The final concentration of DMSO is no more than 0.1%. Thioflavin S (T1892), DL-homocysteine (H4628) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). The purity of each compound was determined to be higher than 98% by HPLC. DMEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Leibovitz's L-15 medium and penicillin/streptomycin were purchased from Gibco (New York, USA). Human Aβ42 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was purchase from Cusabio (Wuhan, China).

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-PPARγ (A0270), HSP90α (A0365), HSP90β (A1087), and mouse anti-GAPDH (AC002) antibodies were purchased from Abclonal (Wuhan, China). Rabbit anti-p-ERK 1/2 (4377S, Thr202/Tyr204) and ERK 1/2 (4695S) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, USA). Rabbit anti-HSP90 (ab13495), Axl (ab32828), tau (ab64193) and p-tau (ab151559, Thr231) antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Rabbit anti-Iba-1 (019-19741) antibody was purchased from Wako (Wako, Japan). Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-rabbit or mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China).

Cell culture

BV2 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 6% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at isobaric oxygen in 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Primary microglia were prepared from P2 rats as previously described 30. Briefly, P2 neonatal rats were ice-anaesthetized and decapitated. The whole brain was removed in chilled saline and then placed into Leibovitz's L-15 conditioned media (Leibovitz's L-15, 0.1% BSA, 1% penicillin/ streptomycin) on ice. After removing the meninges from the brain, the isolated cortex tissue was placed into a new Petri dish with L-15 conditioned media on ice. Tissues were dissociated through pipetting up and down with a sterile pipette and the material were dispensed through a cell strainer (100 μm pore), centrifuged (2500 ×g, 5 min, 4 °C) and resuspended with 6 mL culture media (DEME, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/ streptomycin), then plated into T75 flasks containing 12 mL culture media. Flasks were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until mixed glial cultures were completely confluent. Flasks were shaking at 100 rpm for 1 h at 37 °C. Microglia in the medium were collected and seeded into new dishes or plates with culture media.

Preparation of Aβ42 peptides

The Aβ42 peptides preparation was performed as described before 31. Lyophilized human Aβ42 peptides were dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Then, HFIP was removed in a speed vacuum and the peptide film was stored at -80 °C until use. For soluble oligomeric conditions, peptides were dissolved in Ham's F-12 (phenol red-free) to a final concentration of 100 μM and incubated at 4 °C for 24 h.

Animal study

All experiments and animal care in this study were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978), and the Provision and General Recommendation of Chinese Experimental Animals Administration Legislation and approved by the Science and Technology Department of Jiangsu Province (SYXK (SU) 2016-0011). Male APPswe/PS1Δ9 (APP/PS1) transgenic mice [B6C3-Tg (APPswe, PSEN1dE9)85Bdo/J] at 8 months of age with body weights ranging from 35 to 40 g and their wild type litter mates were obtained from Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. The animals were kept under a consistent temperature (24 °C) with 12 h light/dark cycle and fed with standard food pellets with access to sterile water ad libitum (n=10 per group). Saline (0.1% DMSO), Rosiglitazone (Rog) (0.5 mg/kg/d), JuA (0.5, 1.5 or 5 mg/kg/d) or R428 (3.5 mg/kg, 30 min before the JuA administration) + JuA (5 mg/kg/d) were administrated to the mice through intrathecal injection (i.t.) or by oral gavage once daily for 7 days.

Drug delivery

To enhance the delivery of compounds to the CNS, we chose intrathecal injection, which is widely used in the clinic 32, 33, intrathecal injection was performed as described before 34. The drugs were injected intrathecally (each in 10 μL) by means of lumbar puncture at the intervertebral space of L4-5 or L5-6 for multiple injections using a stainless steel needle (30 gauge) attached to a 25 μL Hamilton syringe.

Morris water maze test

MWM test was performed to detect spatial memory as previously described 35. The escape latencies, swimming speed, time spent in target quadrant and platform-crossing times, were recorded and analyzed by the analysis-management system (Viewer 2 Tracking Software, Ji Liang Instruments, China).

Object recognition test

The object recognition test was performed as described before 36. In short, the test proceeded in a square open field apparatus with a side length of 50 cm. A white cube with side length 8 cm and a blue cylinder with diameter and height of 10 cm were used as the objects to be recognized. In the habituation session, each mouse was individually placed into the empty open field, facing the wall that is near the operator, and the animal was allowed to explore the open field for 5 min, then returned to its home cage. The open field apparatus was cleaned with 70% (v/v) ethanol to minimize olfactory cues before the next mouse entered the open field. The familiarization session was performed 24 h after the habituation step. Two identical objects, either cubes or cylinders, were placed in the open field and 5 cm away from the walls. The mouse was placed in the open field with its head positioned opposite the objects. The mouse was allowed to freely explore for 10 min and then return to its home cage. The open field and objects were cleaned with 70% (v/v) ethanol and air-dried before next use. After all of the animals completed the familiarization session, the two familiar objects were replaced, one with a triplicate copy and the other with a novel object. In the present experiments, one white cube and one blue cylinder were used in the test session. Twenty-four hours after the familiarization session, the test session was performed. The two objects were placed at the same location as before and the animals were allowed to explore freely for 2 min. The exploration time of familiar object and novel object were recorded for analysis. The discrimination index was calculated as follows: Discrimination index = (% time with novel object - % time with familiar object)/(% time with novel object + % time with familiar object) 37

Brian tissue preparation

After the behavior test, mice were anaesthetized by intra-peritoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg) and then perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Brain tissues were immediately removed from the skull. For biochemical analysis, the frontal cortex and hippocampus were separated from brain tissue and stored at -80 °C until use. For thioflavine S staining and immunofluorescence assay, the whole brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C.

Thioflavine S staining

The Aβ plaques in brain tissue were detected by thioflavine S stain. The thioflavine S staining was performed as described before 38. In brief, after overnight fixation in paraformaldehyde, brain tissues were dehydrated by 30% sucrose solution, and then cut into 20 μm paraffin sections. 1% thioflavine S solution was prepared in distilled water and filtered. Brain tissue sections were defatted in xylene and then hydrated through a series of ethanol solutions (100%, 95%, 80%, 70%; 1 min in each solution), placed in water for a few seconds and then stained with 1% thioflavin S for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the sections were dehydrated through a series of ethanol solutions (70%, 80%, 95%, 100%; 1 min in each solution) and xylene for 5 min. Then, the sections were coverslipped with neutral balsam. Thioflavin S staining sections were viewed under ultraviolet light and captured with a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Ti-S, Tokyo, Japan).

Intracellular Aβ clearance assay

The intracellular Aβ clearance assay was performed as previously described 19. Briefly, BV2 cells were pretreated with drugs for 18 h and then administrated with 2 μg/mL soluble Aβ42 in serum-free medium for 24 h in the presence of drugs. At the end of the treatment, cells were washed with PBS to remove remaining Aβ42 that attached on the cell surface. Then, cells were lysed by 1% SDS and the intracellular Aβ42 levels were measured by ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Brain Aβ42 measurement

The cortex and hippocampus samples were lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor (Roche, Germany). The Aβ42 levels were detected by ELISA kit and normalized by total protein concentration.

Western blot assay

BV2 cells and primary microglia were pretreated with 1, 5 or 25 μM JuA followed by the treatment with 5 μM Aβ42 for 12 h. Cells were lysed on ice with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.4)), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mM EDTA) with protease inhibitor phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Germany). Protein samples were separated by electrophoresis using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Then, the membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then washed and incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature and developed using ECL detection. Signals were detected with Tanon-5200 Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon, Shanghai, China). The protein levels were analyzed by Image J (NIH, Bethesda, USA) and normalized to the corresponding GAPDH level.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from BV2 cells and primary microglia using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentrations were equalized and converted to cDNA using Hiscript Ⅱ reverse transcriptase kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Gene expression was measured by quantitative PCR system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using SYBR-green (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH. The sequences of primers used in the experiments are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of gene-specific primers used for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Gene name | Sequences of forward and reverse primers (5' to 3') |

|---|---|

| ABCA1 | AAAACCGCAGACATCCTTCAG |

| CATACCGAAACTCGTTCACCC | |

| CD36 | AGATGACGTGGCAAAGAACAG |

| CCTTGGCTAGATAACGAACTCTG | |

| ApoE | CTGACAGGATGCCTAGCCG |

| CGCAGGTAATCCCAGAAGC | |

| SRA | TGAAGACGAGGACATGCCATC |

| GAGGTACAAAATCCGCACTGA | |

| LXRa | CCTTCCTCAAGGACTTCAGTTACAA |

| CATGGCTCTGGAGAACTCAAAGAT | |

| LXRb | AAGGACTTCACCTACAGCAAGGA |

| GAACTCGAAGATGGGATTGATGA | |

| ABCG1 | AAGGCCTACTACCTGGCAAAGA |

| GCAGTAGGCCACAGGGAACA | |

| GAPDH | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

Plasmid transfection and small interfering RNA knockdown

The coding sequence of mouse HSP90β was cloned into pCMV3-untagged vector to construct pHSP90β. All electroporation experiments were performed using a Neon system and a Neon transfection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, California, USA).

Generation of pPPRE-Luc reporter plasmid and luciferase assay

Three peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) binding sites (5'-AGGGGACCAGGACAAAGGTCACGTTCGGGA-3') were inserted into pGL4.26 by primer annealing to generate PPARγ reporter plasmids, pPPRE-Luc (Figure S1A). HEK293T cells were transfected with pPPRE-Luc. After 24 h, cells were incubated with DMSO or compounds at different concentrations for 24 h. The luciferase activity was measured with luciferase assay system reagent following the manufacturer's protocol (Promega, Madison, USA).

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

Formaldehyde-fixed cells or frozen sections of brain tissue were blocked with 5% normal donkey serum and incubated with indicated primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, and then incubated with FITC-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. DAPI (Thermo, USA) was added and incubated with cells or tissue sections for 15 min and mounted with Fluromount (KeyGen, Nanjing, China). Immunofluorescence was visualized and captured on a confocal microscope (LSM 710, Zeiss, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were assessed using Student's t-test, and comparisons between three or more sets of data were made using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's pos hoc test. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Aβ induces the depletion of HSP90 and PPARγ

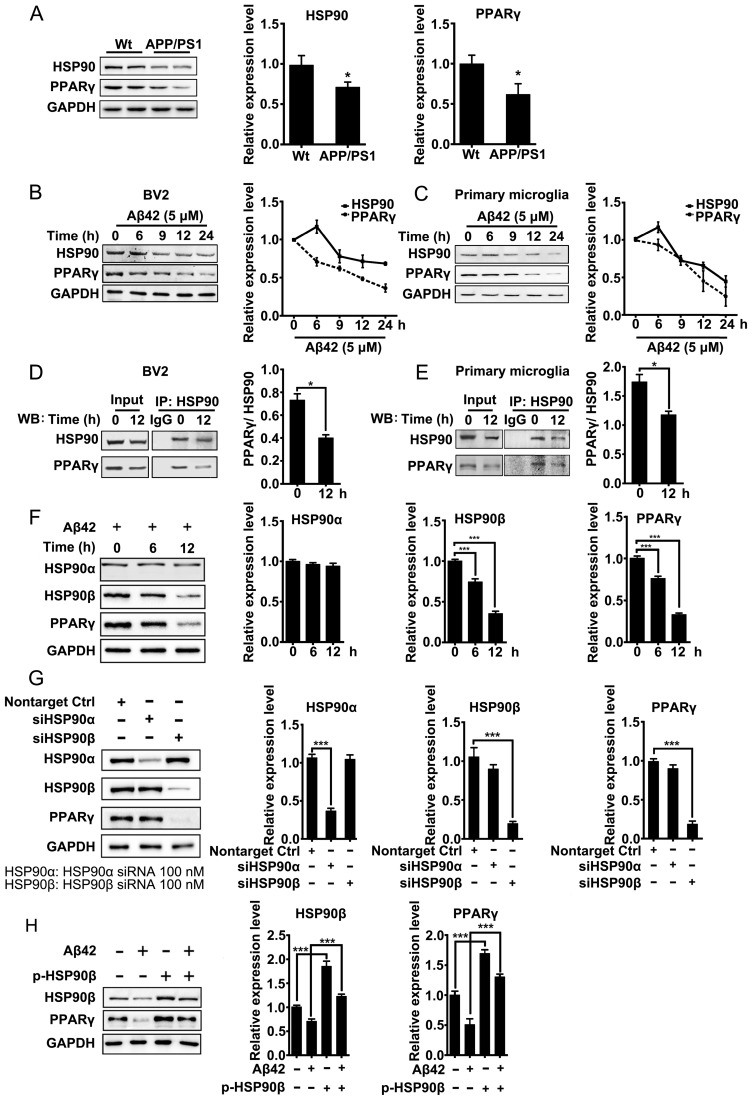

Excess misfolded and damaged proteins overwhelm cellular chaperones, and thus cause functional impairment 39, 40. We first investigated whether the accumulation of Aβ affects HSP90 and PPARγ. Brain tissues from 8-month-old APP/PS1 mice were collected and subjected to western blot analyses. Results showed that protein levels of HSP90 and PPARγ were reduced (Figure 1A). We then checked whether Aβ affects HSP90 and PPARγ in microglia. BV2 cells or primary microglia were treated with Aβ42 (5 μM). After exposure to Aβ42, the levels of HSP90 in BV2 cells (Figure 1B) or primary microglia (Figure 1C) were slightly increased at 6 h, and then decreased over time. PPARγ levels exhibited a time-dependent decrease. We then used co-IP to investigate the interaction between PPARγ and HSP90. We observed that there was a loss of interaction between PPARγ and HSP90 after Aβ42 administration in both BV2 (Figure 1D) and primary microglia (Figure 1E). Altogether, these results demonstrated that Aβ42 not only decreased HSP90 and PPARγ protein levels, but also disrupted the binding between HSP90 and PPARγ.

Figure 1.

Aβ induces depletion of HSP90 and PPARγ. (A) Brain tissue from 8-month-old Wt or APP/PS1 transgenic mice was collected and subjected to Western blot analyses. BV2 cells (B) or primary microglia (C) were administrated Aβ42 (5 μM) for the indicated times. The detergent-soluble lysates from cells were extracted for Western blot assay. BV2 cells (D) or primary microglia (E) were administrated Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. Total protein was extracted and subjected to IP study with indicated antibodies. (F) BV2 cells were incubated with Aβ42 (5 μM) for the indicated times and protein levels of HSP90α, HSP90β and PPARγ were detected. (G) BV2 cells were transfected with indicated siRNA for 48 h. (H) BV2 cells were transfected with p-HSP90β and administrated Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. Whole cell proteins were collected for western blot assay. All Experiments were repeated three times. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. indicated control.

HSP90 has three family members: the constitutive and ubiquitous isoform HSP90β, the stress-inducible and tissue-specific isoform HSP90α, and the mitochondrial form of TRAP. Human HSP90α shows 85.8% amino acid sequence identity to HSP90β 41. Interestingly, in BV2 cells, Aβ42 (5 μM) incubation for 6 h and 12 h led to a decrease of HSP90β and PPARγ, but did not change the levels of HSP90α (Figure 1F). To further identify which paralog of HSP90 is involved in the Aβ42-induced decrease of PPARγ, we separately knocked down HSP90α or HSP90β in BV2 cells using siRNA. Transfection of BV2 cells with siRNA effectively decreased HSP90α or HSP90β expression, respectively (Figure 1G). It was noted that knockdown of HSP90β, instead of HSP90α, significantly decreased PPARγ (Figure 1G). Moreover, overexpression of HSP90β in BV2 cells not only increased the basal levels of PPARγ, but also rescued Aβ42-induced PPARγ decrease (Figure 1H). Taken together, the above findings suggest that HSP90β, rather than HSP90α, is essential for PPARγ stability in microglia.

JuA activates PPARγ and facilitates Aβ42 degradation in microglia

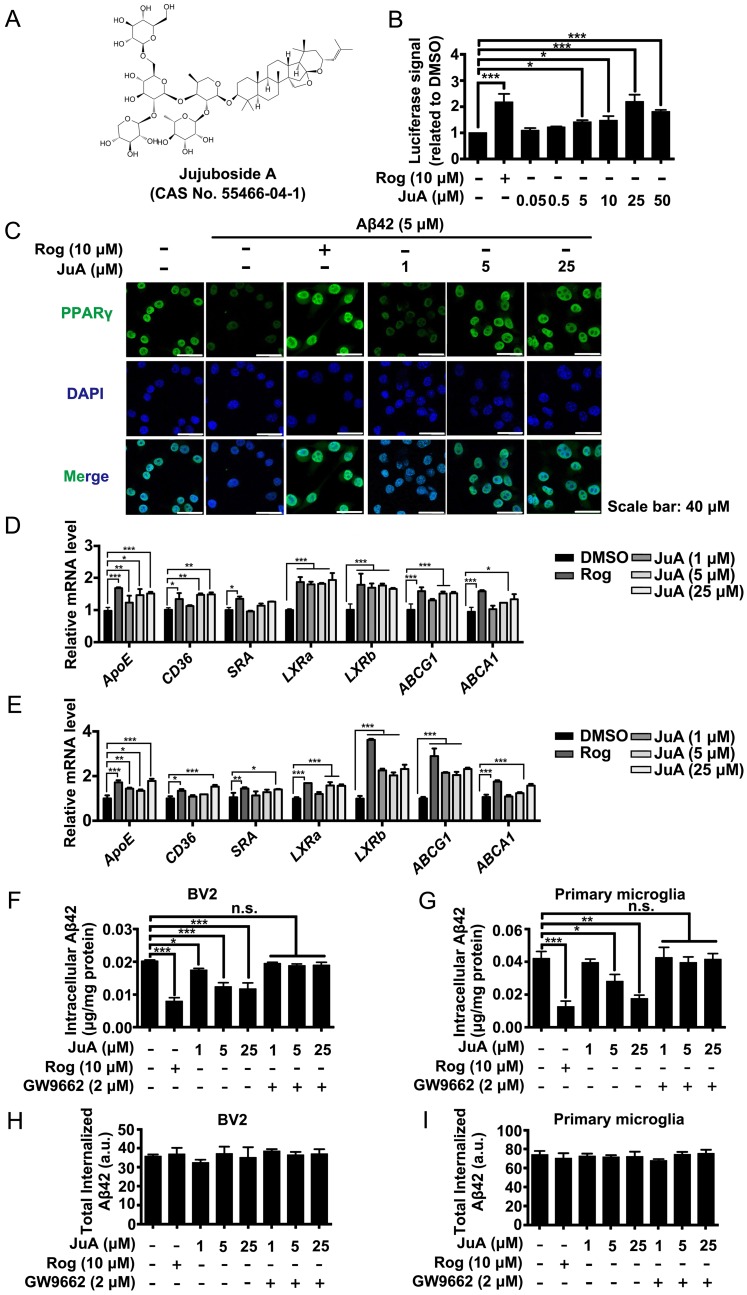

Using a stable cell line carrying a luciferase reporter driven by a PPRE-containing promoter (Figure S1A), we screened an in-house small compound pool containing about 350 natural products 42. JuA (Figure 2A) was found to significantly increase the PPRE-luciferase activity (Figure 2B) and showed negligible cytotoxicity in BV2 cells (Figure S1B) or primary microglia (Figure S1C). The protein level and subcellular localization of PPARγ in BV2 cells were determined by immunofluorescence staining. As shown in Figure 2C, PPARγ was mainly localized in the nuclei. PPARγ was down-regulated after Aβ42 treatment, while JuA dose-dependently reversed the Aβ42 effects on PPARγ. We then examined the expression of PPARγ target genes in BV2 or primary microglia. The expression levels of CD36, SRA3, LXRa and LXRb were up-regulated after treatment with JuA in a dose-dependent manner. JuA treatment also increased the expression levels of ApoE, ABCG1 and ABCA1 in BV2 or primary microglia partially via the induction of LXR expression 9, 43, 44 (Figure 2D-E).

Figure 2.

Aβ induces impaired PPARγ activity in microglia. (A) The structure and CAS number of JuA. (B) HEK293/PPRE-Luc cells were treated with Rog (10 μM) or indicated concentrations of JuA for 24 h, then cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured. (C) BV2 cells were pretreated with JuA for 30 min, followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. Cells were fixed and immunostained with PPARγ antibody. The representative images demonstrate the amount and localization of PPARγ (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 40 μm. BV2 cells (D) and primary microglia (E) were pretreated with JuA for 30 min, followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 6 h. The expression of various genes was analyzed by Q-PCR. DMSO at 0.1% was used as control. BV2 cells (F) and primary microglia (G) were pretreated with JuA at indicated concentrations with or without GW9662 (2 μM) for 18 h, and then incubated with 2 mg/mL Aβ42 in the presence of vehicle (DMSO) or drug for an additional 24 h. The intracellular Aβ42 levels were measured using ELISA. Uptake of Aβ42 by BV2 (H) and primary microglia (I) was assessed by applying FITC-labeled Aβ42 to microglia after pretreatment with indicated compounds. The accumulation of the fluorophore was analyzed by flow cytometry. The results were normalized to total cellular protein. DMSO at 0.1% was used as control. All experiments were repeated three times. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. indicated control.

We then investigated whether JuA could promote Aβ degradation in microglia. The intracellular Aβ42 levels were significantly reduced by JuA treatment both in BV2 (Figure 2F) and primary microglia (Figure 2G). The Aβ42 clearance ability of JuA was blocked by GW9662, a specific PPARγ antagonist (Figure 2F-G). To exclude the possibility that the reduced Aβ42 was due to reduced uptake, the cumulative internalization of Aβ42 was monitored using flow cytometry with FITC-labeled Aβ42. FITC-labeled Aβ42 is taken up by microglia and degraded. After Aβ42 is degraded by microglia, the fluorophore is still retained within the cells, thus the total cellular fluorescence is an independent indicator of total Aβ42 uptake 45. As shown in Figure 2H-I, the total internalized Aβ42 levels in BV2 or primary microglia were not affected by drug treatment. Taken together, these data suggest that JuA facilitates the degradation of Aβ42 in microglia through enhancing PPARγ activity.

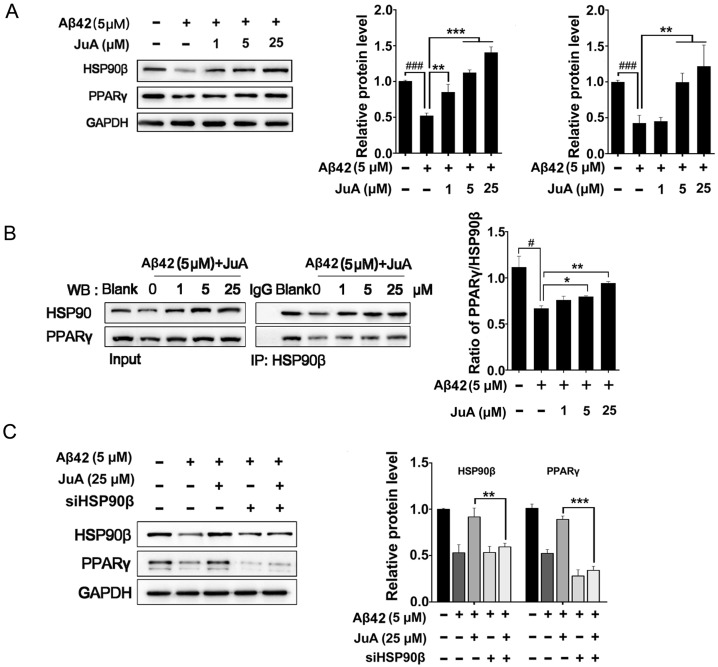

JuA up-regulates PPARγ levels through HSP90β

We then checked whether JuA preserved PPARγ in an HSP90β-dependent manner. BV2 cells were incubated with Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h with or without pretreatment with JuA. JuA pretreatment reversed Aβ42-induced HSP90β and PPARγ decrease in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A). After BV2 cells were incubated with Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h, the interaction between HSP90β and PPARγ was significantly disrupted (Figure 3B). JuA (25 μM) treatment clearly protected the interaction between HSP90β and PPARγ in a dose-dependent manner. When HSP90β was knocked down in BV2 cells, the activity of JuA was completely reversed (Figure 3C). Together, these results indicate that JuA restores protein levels of PPARγ under Aβ42 stress through increasing HSP90β.

Figure 3.

HSP90β is essential for maintaining PPARγ function in microglia. BV2 cells were pretreated with JuA at 1 μM, 5 μM or 25 μM for 30 min, followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. Total protein was extracted and subjected to western blot (A) and IP study (B) with indicated antibodies. (C) BV2 cells were transfect with HSP90β siRNA for 48 h, and then pretreated with JuA for 30 min followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. DSMO at 0.1% was used as Ctrl. Whole cell proteins were collected for western blot assay. All experiments were repeated three times. ###p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

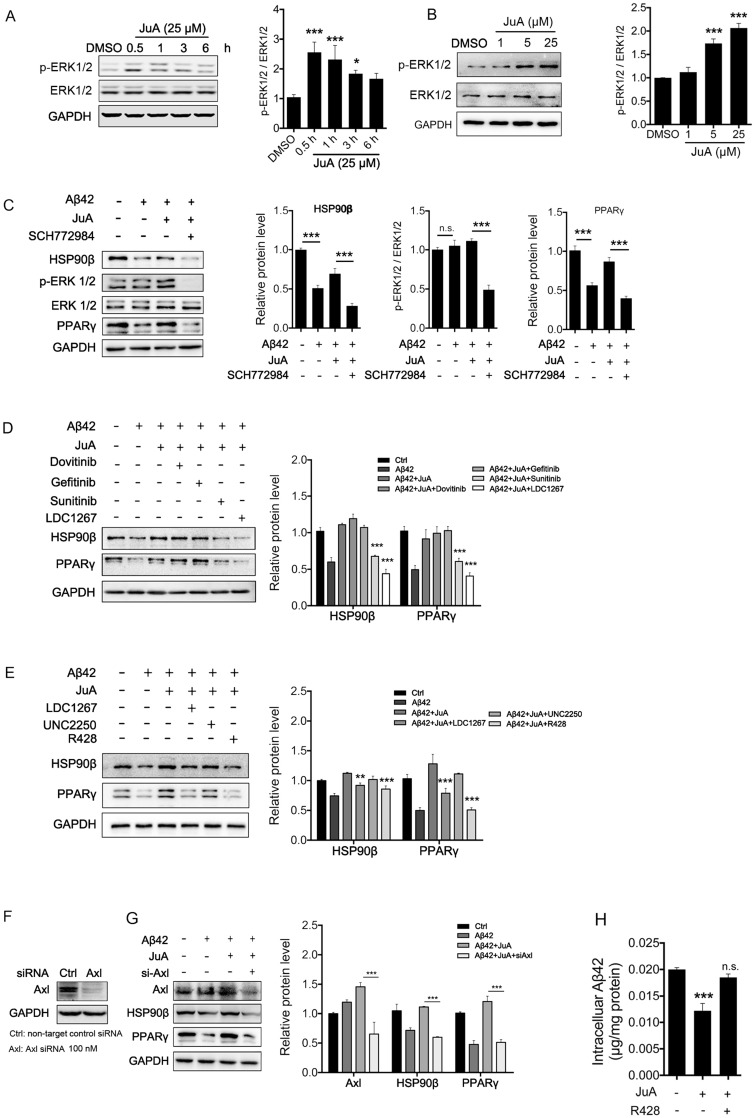

JuA up-regulates HSP90β in an Axl-dependent manner

It has been reported that the expression of HSP90β could be regulated by ERK 46, 47. We then tested whether JuA could affect ERK activity. As was shown, JuA increased phosphorylation of ERK in time-dependent (Figure 4A) and dose-dependent (Figure 4B) manners in BV2 cells. Effects of JuA on HSP90β, as well as PPARγ, were blocked by SCH772984, an ERK-specific inhibitor (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

JuA up-regulates HSP90β in an Axl/ERK-dependent manner. BV2 cells were treated with JuA (25 μM) for indicated periods of time (A), or treated with JuA at indicated concentrations for 0.5 h (B). (C) BV2 cells were pretreated with 0.1% DMSO (Ctrl), JuA (25 μM) or JuA (25 μM) + SCH772984 (10 μM) for 30 min, followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 6 h. (D) BV2 cells were pretreated with 0.1% DMSO (Ctrl), JuA (25 μM) or JuA (25 μM) with the indicated antagonist of RTKs (Dovitinib at 1 μM, Gefinitib at 2.5 μM, Sunitinib at 2.5 μM and LDC1267 at 1 μM) for 30 min, followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. (E) BV2 cells were pretreated with 0.1% DMSO (Ctrl), JuA (25 μM) or JuA (25 μM) with the indicated antagonist of TAM receptor (LDC1267 at 1 μM, UNC2250 at 5 μM, R428 at 5 μM) for 30 min, followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. (F) BV2 cells were transiently transfected with non-target control siRNA or siAxl for 48 h. (G) BV2 cells were transfected with siAxl for 48 h, then pretreated with JuA (25 μM) followed by administration of Aβ42 (5 μM) for 12 h. The whole-cell proteins were subjected to western blot with the antibodies indicated. All experiments were repeated three times. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

As RTK is one of the most important upstream regulators of ERK 48-50, we next investigated whether RTK is involved in the activation of JuA. We applied a non-specific RTK antagonist (Sunitinib), and specific antagonists targeting the key membrane receptors of microglia, including EGFR (Dovitinib), VEGFR (Gefitinib) and TAM receptor (LDC1267), to identify which subtype of RTKs is essential for JuA activity. As shown in Figure 4D, pretreatment with Sunitinib and LDC1267 completely reversed JuA-induced up-regulation of HSP90β, strongly indicating that TAM receptors are involved in the JuA activity. Axl and Mer are the main types of TAM receptors that are expressed in microglia 51; we further treated BV2 cells with JuA in the presence of specific inhibitors targeting Axl (R428) or Mer (UNC2250). It was shown that R428 strongly suppressed JuA-induced HSP90β expression (Figure 4E), while UNC2250 did not affect JuA activity. To further confirm the results, we knocked down Axl using siRNAs in BV2 cells (Figure 4F), and observed that Axl knockdown completely reversed the effect of JuA on HSP90β and PPARγ (Figure 4G). Moreover, R428 could also inhibit JuA-induced Aβ42 clearance in BV2 cells (Figure 4H). Taken together, these results suggest that JuA increases HSP90β expression and preserves PPARγ activity through the Axl/ERK pathway.

JuA ameliorates cognitive deficiency in APP/PS1 transgenic mice models and decreases Aβ accumulation in the brain

To further test the in vivo effects of JuA, 8-month-old APP/PS1 transgenic mice were applied, which simulate the late-onset pathological process of AD in humans 52. At the age of 8 months, APP/PS1 transgenic mice develop abundant plaques in the hippocampus and cortex 53, and show deficits in learning and memory 54.

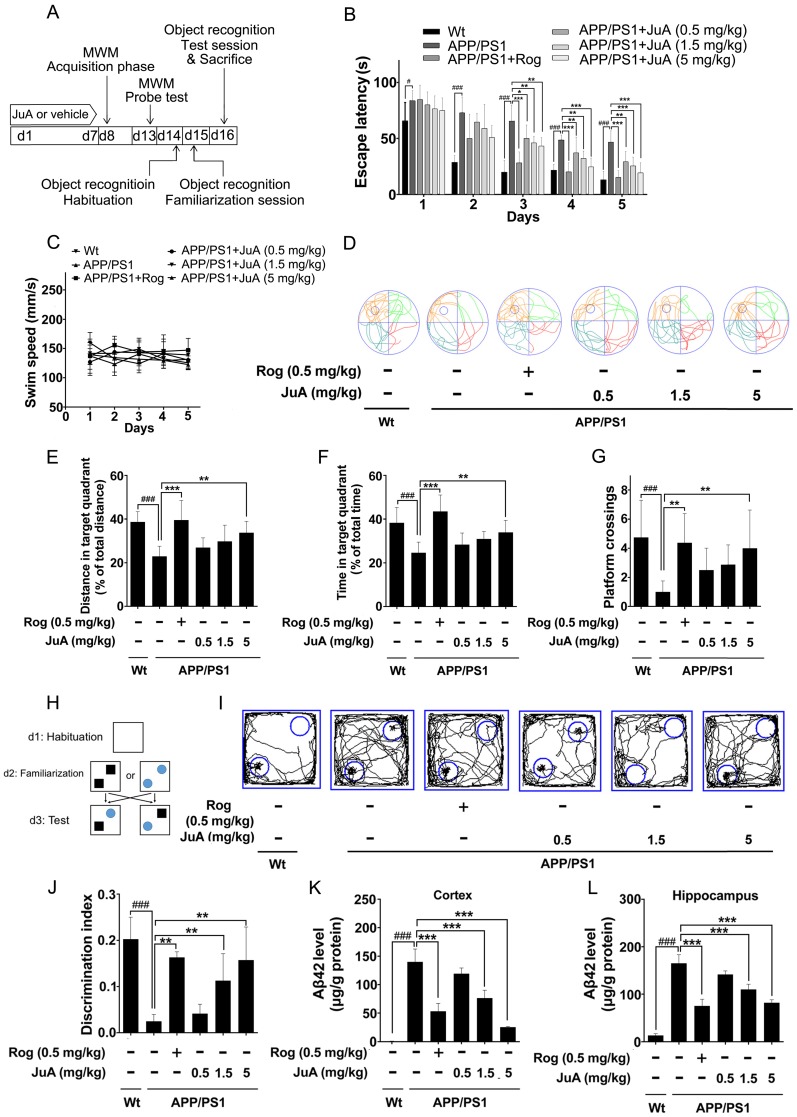

The animal experimental design is depicted in Figure 5A. Mice were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO-saline, i.t.), Rog (0.5 mg/kg, i.t.) or JuA (0.5 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg, i.t.) once daily for 7 days. The MWM test and object recognition test were performed to evaluate the effect of JuA on APP/PS1 transgenic mice.

Figure 5.

JuA ameliorates the cognitive deficiency in APP/PS1 mice. (A) Experimental design for the animal study. 8-mon-old APP/PS1 mice were treated with saline (i.t.), Rog (0.5 mg/kg, i.t.) or JuA (0.5 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, i.t.) once daily for 7 days. (B) Escape latency and (C) swim speed during spatial acquisition training. (D) Representative motion track, (E) distance in the target quadrant, (F) time spent in the target quadrant and (G) the platform crossing number in the spatial probe test. (H) The procedure for the object recognition test. (I) Representative motion track and (J) the discrimination index in the object recognition test. After the MWM test and the object recognition test, animals were sacrificed and the brain tissues were collected. Aβ42 levels in the cortex (K) and hippocampus (L) were detected by ELISA. # p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 vs. Wt group. * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. APP/PS1 group.

In the MWM test, the APP/PS1 group displayed significantly longer escape latency compared to the wild-type littermate control mice (Wt) group during spatial acquisition training, which can be improved by JuA treatment (Figure 5B). The swim speed was not altered after treatment (Figure 5C). In the spatial probe test, the distance and time in the target quadrant and the platform crossing numbers of the APP/PS1 group were significantly lower than those of the Wt group, indicating the impairment of spatial memory capacity, which can be reversed by JuA treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5D-G).

The procedure used for the object recognition test is shown in Figure 5H. In the object recognition test, the discrimination index was used to evaluate learning and memory ability in mice, where a higher index value indicates greater preference for the new object. The Wt mice group preferred the novel objects while the APP/PS1 group showed no significant preference. Administration of JuA at doses of 1.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg effectively cured the impaired learning and memory ability of APP/PS1 transgenic mice and the discrimination values were significantly higher than those of the APP/PS1 group (Figure 5I-J). Moreover, the Aβ42 levels in the cortex (Figure 5K) and hippocampus (Figure 5L) were down-regulated by JuA treatment. Similar results were observed when JuA was administrated orally (Figure S2). These results demonstrate that JuA ameliorates cognitive deficiency and reduces Aβ42 accumulation in the brains of APP/PS1 transgenic mice.

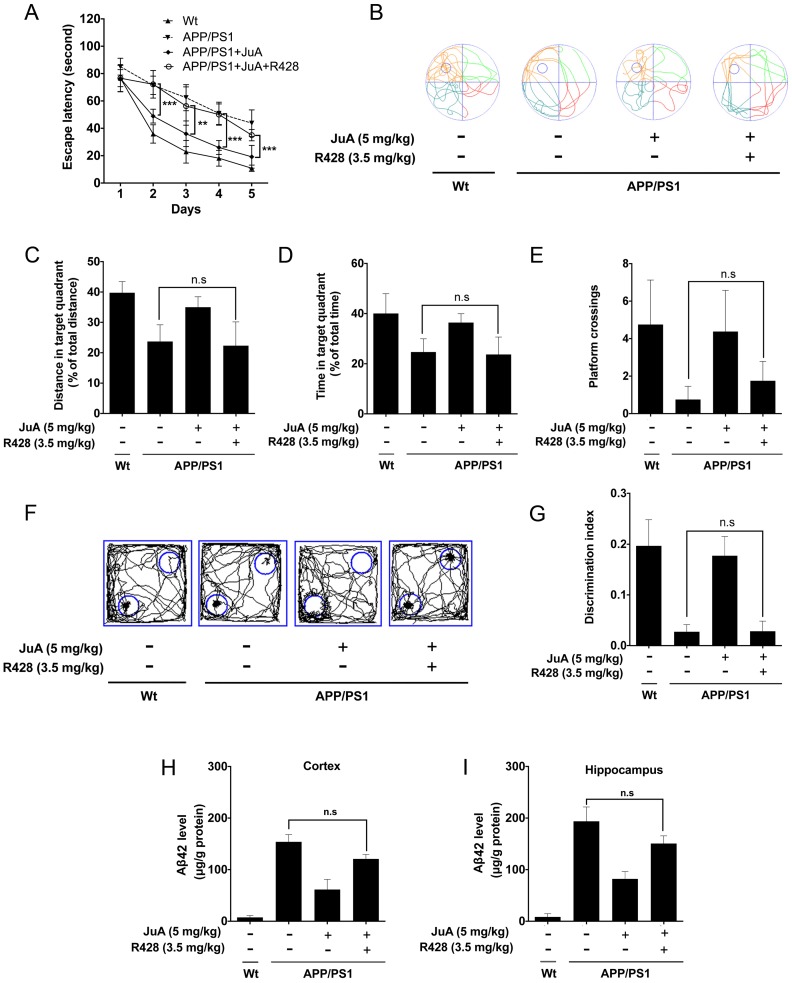

JuA ameliorates the cognitive deficiency in APP/PS1 mice through Axl

The effect of JuA in APP/PS1 mice could be blocked by the PPARγ-specific inhibitor GW9662 (Figure S3); these results agree with the in vitro study. We then validated whether JuA promotes Aβ42 clearance via Axl in vivo. The APP/PS1 transgenic mice were administrated JuA (5 mg/kg, i.t.) alone or treated with JuA and R428 (3.5 mg/kg, i.t., 30 min before the JuA administration), once daily for 7 days. In the MWM test, the JuA-treated group showed significantly shorter escape latency in spatial acquisition training compared to the APP/PS1 group. However, pretreatment with Axl inhibitor R428 abolished the effect of JuA (Figure 6A). In the spatial probe test, the distance and time spent in the target quadrant, and platform crossing numbers were increased by JuA treatment, while R428 reversed the effect of JuA (Figure 6B-E). Similarly, in the object recognition test, the discrimination index cured by JuA was also reversed by R428 (Figure 6F-G). These results suggest that Axl is essential for the memory recovery effects of JuA in APP/PS1 mice.

Figure 6.

JuA ameliorates the cognitive deficiency in APP/PS1 mice through Axl. 8-month-old APP/PS1 mice were treated with JuA (5 mg/kg, i.t.) or treated with JuA and R428 (3.5 mg/kg, i.t.) once daily for 7 days. (A) Escape latency during spatial acquisition training. (B) Representative motion track, (C) distance in the target quadrant, (D) time spent in the target quadrant, and (E) the platform crossing number in the spatial probe test. (F) Representative motion track and (G) discrimination index in the object recognition test. (H) After the MWM test and the object recognition test, animals were sacrificed and the brain tissues were collected. Aβ42 levels in the cortex and hippocampus were detected by ELISA. ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In addition, Aβ42 levels in the cortex and hippocampus were both down-regulated by JuA, which was completely blocked by R428 (Figure 6H-I). Taken together, these results indicate that JuA ameliorates cognitive deficiency and decreases the accumulation of Aβ42 in an Axl-dependent manner.

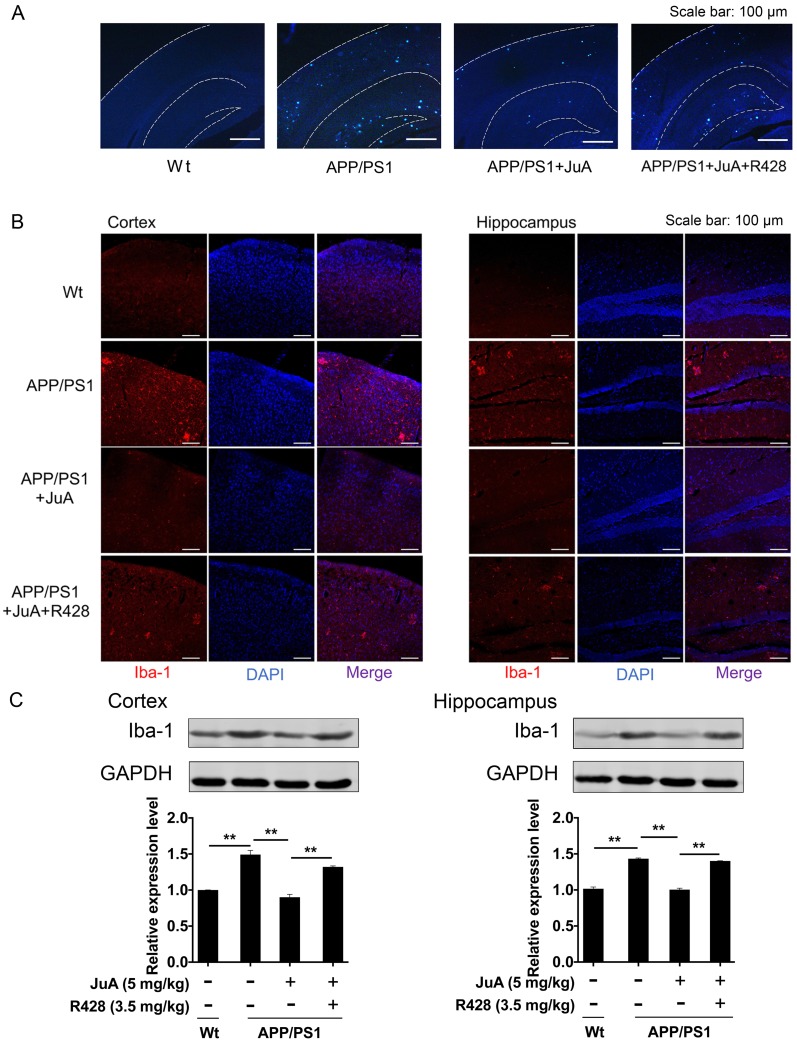

JuA reduces plaques and relieves over-activation of microglia in the brain

The above results showed that JuA treatment decreased the levels of soluble Aβ. We then validated whether JuA promotes the clearance of insoluble plaques. Wide distribution of thioflavin-S+ plaques (indicative of insoluble plaques) in the cortex and hippocampus were observed in the brains of APP/PS1 transgenic mice. JuA treatment significantly reduced the insoluble plaques number both in the cortex and hippocampus. R428 blocked the effect of JuA (Figure 7A), indicating Axl plays a pivotal role in the function of JuA for the clearance of Aβ42.

Figure 7.

JuA reduces plaques and relieves over-activation of microglia in the brain. 8-month-old APP/PS1 mice were treated with JuA (5 mg/kg, i.t.) or treated with JuA and R428 (3.5 mg/kg, i.t., 30 min before the JuA administration) once daily for 7 days. (A) Representative cortex and hippocampus sections stained with thioflavin S. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Brain tissues were fixed and stained with Iba-1 primary antibody, then imaged by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Representative image demonstrating the morphology of microglia in the cortex and hippocampus. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Iba-1 levels in the cortex and hippocampus detected by Western blot. ** p < 0.01

The abnormal accumulation of Aβ induces excessive activation of microglia in the brain, which is associated with neuron injury in AD 55. Iba-1 is a calcium-binding protein that is specifically expressed in brain microglia and up-regulated upon microglia activation 56. We then detected Iba-1-positive cells in the brain by immunofluorescence staining, and quantified Iba-1 level in the cortex and hippocampus by western blot. As shown in Figure 7B, cells with precise Iba-1-positive staining of the cytoplasm were identified as microglia in the brain tissues. Strong activation of microglia was found in the brains of APP/PS1 mice. JuA treatment significantly inhibited the activation of microglia, while the effects of JuA on microglia were greatly inhibited by R428. Western blot results showed that Iba-1 levels were elevated in the cortex and hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice (Figure 7C). JuA treatment significantly decreased Iba-1 expression in brain tissues of APP/PS1 mice, which was reversed by R428 (Figure 7C). The above data suggest that JuA promotes the clearance of both soluble and insoluble Aβ plaques, and inhibits abnormal activation of microglia in vivo in an Axl-dependent manner.

Discussion

The integrity of the proteome is challenged with age and progression of AD pathology. Chaperones have an important role in the repair of proteotoxic damage 39. The content of chaperones, such as HSP90, decreases during ageing due to the increased amount of damaged proteins 21, 57. In recent years, especially heat shock proteins (HSPs) chaperones have been considered as critical regulators of proteins-associated neurodegenerative diseases 58. Cytosolic HSP70 and HSP90 inhibit early stages of amyloid aggregation 59. Carboxy-terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) has also been found to be critical for tau degradation and this association is facilitated by HSP70 60. HSP90 was found to enhance the phagocytosis and degradation of Aβ42 by microglia both in vitro and in vivo 61, 62. Since the accumulation of Aβ in the brain is considered the primary factor in driving AD pathogenesis, we wondered whether Aβ accumulation could also affect the ability of chaperones in microglia, which are responsible for Aβ homeostasis. Our results showed that protein levels of HSP90 were decreased in microglia incubated with Aβ42 peptides (Figure 1). Further study indicated that the levels of HSP90α did not alter in the presence of Aβ42, suggesting that, although highly conserved, these different family members play different roles in stressed conditions. Therefore, a HSP90β-specific activator might provide satisfactory therapeutic effects for AD.

It has been reported that HSP90β plays a critical role in PPARγ stability and cellular differentiation in adipocytes 26, human hepatoma cells and mouse livers 63. Similarly, here we demonstrated that the stability and functions of PPARγ in microglia could be regulated by HSP90β. Aβ stress or knockdown of HSP90β dampened PPARγ in microglia (Figure 1). In this study, we found that JuA increased the expression of HSP90β, and enhanced the interaction between HSP90β and PPARγ (Figure 2). As knockdown of HSP90β reversed the effects of JuA, we conclude that HSP90β is a major downstream effector of JuA (Figure 3).

It has been showed that the MEK/ERK pathway regulates the expression of HSP90β 47. Axl, one of the upstream regulators of ERK, was found to regulate ERK pathway in different cells including chondrocytes 64, cardiac fibroblasts 65 and several tumor cells 66. Axl is a member of TAM receptors, which belong to RTKs 67. In the CNS, Tyro3 is abundant in neurons 68, whereas Mer and Axl are present in microglia 69-71. Axl functions as controller of microglial physiology 51. Up-regulation of Axl in microglia licenses their phagocytic activity and promotes plaque clearance 72. Our results suggested that the mechanism of HSP90β up-regulation by JuA in BV2 cells is, at least partially, through an Axl/ERK-dependent manner, since the effect of JuA on HSP90β can be blocked by ERK inhibitor SCH772984, Axl antagonist R428, as well as Axl siRNA (Figure 4). Moreover, the in vivo effects of JuA were also inhibited by R428. It is interesting that the expression of Axl is also regulated by the nuclear receptors (NRs) pathway. Retinoid X receptor (RXR) forms obligate heterodimers with PPARγ and comprise the functional transcription factor 73. Savage et al. has reported that bexarotene, an agonist of RXR, increases Mer and Axl expression in plaque-associated immune cells, consequently licensing their phagocytic activity and promoting plaque clearance 72. Combined with our findings, the above results suggest a positive feedback between Axl and PPARγ signaling pathway, which may explain the notable high-efficiency clearing of both soluble Aβ and insoluble plaques in the brain after treatment with JuA (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

In the present study, we mainly focused on the process of microglia since they function as phagocytes in the brain and are responsible for Aβ clearance 11. Astrocytes mediate the degradation of extracellular Aβ through secrete proteases 74. Several reports have shown that astrocytes also have the ability to take up Aβ 75, 76. A recent study found that activated PPARγ in astrocytes increases the expression of lipidated ApoE and might participate in clearance of insoluble Aβ 9. Therefore, the clearance of deposited plaques in APP/PS1 mice by JuA could also be partially attributed to astrocytes activation.

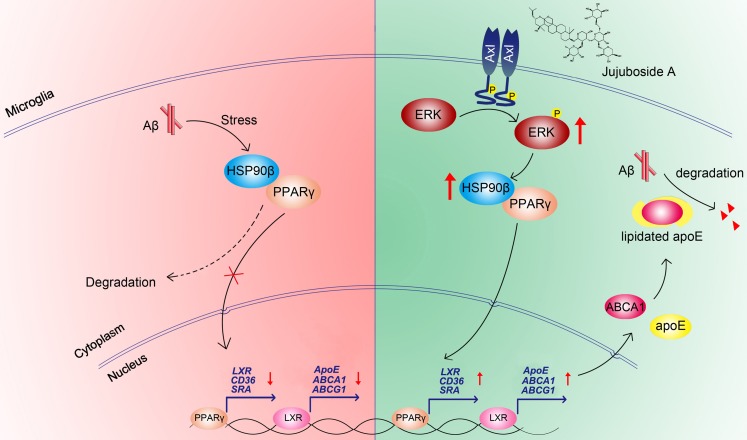

In conclusion, the present study showed that the levels and functions of PPARγ were impaired under Aβ stress due to the decrease of HSP90β in microglia. The small molecule JuA increased the expression of HSP90β and maintained the stability of PPARγ in an Axl/ERK-dependent manner, and enhanced Aβ clearance in microglia (Figure 8). Interestingly, our study also showed that JuA inhibited Aβ or DL-homocysteine-induced tau protein phosphorylation (Figure S4). JuA treatment effectively ameliorated learning and memory deficiencies in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Our study sheds some light on the key role of HSP90β in microglia function, and indicates that JuA can serve as a leading compound for the pharmacological control of AD.

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism of JuA-mediated Aβ clearance.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81573637, 81421005), “Twelfth-Five Years” Supporting Programs from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2015ZX09101043), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) and 111 Project (no. B16046).

The authors acknowledge technical support from Ms. Ping Zhou, and Dr. Wenling Dai for animal studies. We thank Mr. David Anderson from Southeast University for English proof reading.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid β

- CNS

central nervous system

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- Hcy

DL-homocysteine

- HSP90

heat shock protein 90

- i.t.

intrathecal

- JuA

jujuboside A

- MWM

morris water maze

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ

- PPRE

peroxisome proliferator response element

- Rog

rosiglitazone

- RXR

retinoid X receptor.

References

- 1.Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4245–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer's disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:77sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polanco JC, Li C, Bodea LG, Martinez-Marmol R, Meunier FA, Gotz J. Amyloid-beta and tau complexity - towards improved biomarkers and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:22–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM. et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC. et al. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2010;330:1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norden DM, Godbout JP. Microglia of the Aged Brain: Primed to be Activated and Resistant to Regulation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2012.01306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandrekar-Colucci S, Karlo JC, Landreth GE. Mechanisms underlying the rapid peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-mediated amyloid clearance and reversal of cognitive deficits in a murine model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32:10117–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5268-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandrekar S, Jiang Q, Lee CY, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Landreth GE. Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Abeta through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4252–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers J, Strohmeyer R, Kovelowski CJ, Li R. Microglia and inflammatory mechanisms in the clearance of amyloid beta peptide. Glia. 2002;40:260–9. doi: 10.1002/glia.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer PE, Cirrito JR, Wesson DW, Lee CY, Karlo JC, Zinn AE. et al. ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models. Science. 2012;335:1503–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1217697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry VH, Holmes C. Microglial priming in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:217. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer's disease mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8354–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston H, Boutin H, Allan SM. Assessing the contribution of inflammation in models of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:886–90. doi: 10.1042/BST0390886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen CH, Zhou W, Liu S, Deng Y, Cai F, Tone M. et al. Increased NF-kappaB signalling up-regulates BACE1 expression and its therapeutic potential in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:77–90. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landreth G. PPARgamma agonists as new therapeutic agents for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:245–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mrak RE, Landreth GE. PPARgamma, neuroinflammation, and disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1:209–215. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Q, Lee CY, Mandrekar S, Wilkinson B, Cramer P, Zelcer N. et al. ApoE promotes the proteolytic degradation of Abeta. Neuron. 2008;58:681–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sastre M, Dewachter I, Rossner S, Bogdanovic N, Rosen E, Borghgraef P. et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs repress beta-secretase gene promoter activity by the activation of PPARgamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:443–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503839103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nardai G, Csermely P, Soti C. Chaperone function and chaperone overload in the aged. A preliminary analysis. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:1257–62. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gezen-Ak D, Dursun E, Hanağası H, Bilgiç B, Lohman E, Araz ÖS. et al. BDNF, TNFα, HSP90, CFH, and IL-10 serum levels in patients with early or late onset Alzheimer's disease or mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37:185–95. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans CG, Wisén S, Gestwicki JE. Heat shock proteins 70 and 90 inhibit early stages of amyloid β-(1-42) aggregation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33182–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schirmer C, Lepvrier E, Duchesne L, Decaux O, Thomas D, Delamarche C. et al. Hsp90 directly interacts, in vitro, with amyloid structures and modulates their assembly and disassembly. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1860:2598–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:243–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen MT, Csermely P, Soti C. Hsp90 chaperones PPARgamma and regulates differentiation and survival of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1654–63. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han D, Wan C, Liu F, Xu X, Jiang L, Xu J. Jujuboside A Protects H9C2 Cells from Isoproterenol-Induced Injury via Activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:9593716. doi: 10.1155/2016/9593716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Zhao X, Liu B, Liu AJ, Li H, Mao X. et al. Jujuboside A, a neuroprotective agent from semen Ziziphi Spinosae ameliorates behavioral disorders of the dementia mouse model induced by Abeta 1-42. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;738:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang XX, Ma GI, Xie JB, Pang GC. Influence of JuA in evoking communication changes between the small intestines and brain tissues of rats and the GABAA and GABAB receptor transcription levels of hippocampal neurons. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;159:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamashiro TT, Dalgard CL, Byrnes KR. Primary microglia isolation from mixed glial cell cultures of neonatal rat brain tissue. J Vis Exp; 2012. e3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stine WB Jr, Dahlgren KN, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-beta peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11612–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tobinick EL. Perispinal Delivery of CNS Drugs. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:469–80. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0339-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi JQ, Wang BR, Jiang WW, Chen J, Zhu YW, Zhong LL. et al. Cognitive improvement with intrathecal administration of infliximab in a woman with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1142–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai WL, Xiong F, Yan B, Cao ZY, Liu WT, Liu JH. et al. Blockade of neuronal dopamine D2 receptor attenuates morphine tolerance in mice spinal cord. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38746. doi: 10.1038/srep38746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leger M, Quiedeville A, Bouet V, Haelewyn B, Boulouard M, Schumann-Bard P. et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2531–7. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erica Korb MH, Ilana Zucker-Scharff, Robert B Darnell, C David Allis. BET protein Brd4 activates transcription in neurons and BET inhibitor Jq1 blocks memory in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:13. doi: 10.1038/nn.4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajamohamedsait HB, Sigurdsson EM. Histological staining of amyloid and pre-amyloid peptides and proteins in mouse tissue. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;849:411–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-551-0_28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vilchez D, Saez I, Dillin A. The role of protein clearance mechanisms in organismal ageing and age-related diseases. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5659. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisenberg D, Jucker M. The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases. Cell. 2012;148:1188–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen B, Piel WH, Gui L, Bruford E, Monteiro A. The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: insights into their divergence and evolution. Genomics. 2005;86:627–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Shi ZQ, Zhang M, Xin GZ, Pang T, Zhou P. et al. Camptothecin and its analogs reduce amyloid-beta production and amyloid-beta42-induced IL-1beta production. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:465–77. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li AC, Binder CJ, Gutierrez A, Brown KK, Plotkin CR, Pattison JW. et al. Differential inhibition of macrophage foam-cell formation and atherosclerosis in mice by PPARalpha, beta/delta, and gamma. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1564–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI18730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chawla A, Boisvert WA, Lee CH, Laffitte BA, Barak Y, Joseph SB. et al. A PPAR gamma-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:161–71. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandrekar S, Jiang Q, Lee CD, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Landreth GE. Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Aβ through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4252–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romanello M, Bivi N, Pines A, Deganuto M, Quadrifoglio F, Moro L. et al. Bisphosphonates activate nucleotide receptors signaling and induce the expression of Hsp90 in osteoblast-like cell lines. Bone. 2006;39:739–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chatterjee M, Jain S, Stuhmer T, Andrulis M, Ungethum U, Kuban RJ. et al. STAT3 and MAPK signaling maintain overexpression of heat shock proteins 90alpha and beta in multiple myeloma cells, which critically contribute to tumor-cell survival. Blood. 2007;109:720–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy LO, Blenis J. MAPK signal specificity: the right place at the right time. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramos JW. The regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in mammalian cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKay MM, Morrison DK. Integrating signals from RTKs to ERK/MAPK. Oncogene. 2007;26:3113–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fourgeaud L, Traves PG, Tufail Y, Leal-Bailey H, Lew ED, Burrola PG. et al. TAM receptors regulate multiple features of microglial physiology. Nature. 2016;532:240–4. doi: 10.1038/nature17630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reiserer RS, Harrison FE, Syverud DC, McDonald MP. Impaired spatial learning in the APPSwe + PSEN1DeltaE9 bigenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, Xu GM, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA. et al. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:159–70. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lalonde R, Kim HD, Maxwell JA, Fukuchi K. Exploratory activity and spatial learning in 12-month-old APP(695)SWE/co+PS1/DeltaE9 mice with amyloid plaques. Neurosci Lett. 2005;390:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, Khoury JE, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL. et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:515–28. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Csermely P. Chaperone overload is a possible contributor to 'civilization diseases'. Trends Genet. 2001;17:701–4. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koren J 3rd, Jinwal UK, Lee DC, Jones JR, Shults CL, Johnson AG. et al. Chaperone signalling complexes in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:619–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans CG, Wisen S, Gestwicki JE. Heat shock proteins 70 and 90 inhibit early stages of amyloid beta-(1-42) aggregation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33182–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jinwal UK, Akoury E, Abisambra JF, O'Leary JC 3rd, Thompson AD, Blair LJ. et al. Imbalance of Hsp70 family variants fosters tau accumulation. FASEB J. 2013;27:1450–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-220889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kakimura J, Kitamura Y, Takata K, Umeki M, Suzuki S, Shibagaki K. et al. Microglial activation and amyloid-beta clearance induced by exogenous heat-shock proteins. FASEB J. 2002;16:601–3. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0530fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Tsuchiya D, Kawasaki T, Taniguchi T, Shimohama S. Heat shock protein-90-induced microglial clearance of exogenous amyloid-beta1-42 in rat hippocampus in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 2003;344:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wheeler MC, Gekakis N. Hsp90 modulates PPARgamma activity in a mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:1702–10. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M048918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hutchison MR, Bassett MH, White PC. SCF, BDNF, and Gas6 are regulators of growth plate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:193–203. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Batlle M, Recarte-Pelz P, Roig E, Castel MA, Cardona M, Farrero M. et al. AXL receptor tyrosine kinase is increased in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173:402–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Axelrod H, Pienta KJ. Axl as a mediator of cellular growth and survival. Oncotarget. 2014;5:8818–52. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lemke G. Biology of the TAM receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a009076. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lai C, Lemke G. An extended family of protein-tyrosine kinase genes differentially expressed in the vertebrate nervous system. Neuron. 1991;6:691–704. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S. et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1118–28. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grommes C, Lee CY, Wilkinson BL, Jiang Q, Koenigsknecht-Talboo JL, Varnum B. et al. Regulation of microglial phagocytosis and inflammatory gene expression by Gas6 acting on the Axl/Mer family of tyrosine kinases. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008;3:130–40. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ji R, Tian S, Lu HJ, Lu Q, Zheng Y, Wang X. et al. TAM receptors affect adult brain neurogenesis by negative regulation of microglial cell activation. J Immunol. 2013;191:6165–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Savage JC, Jay T, Goduni E, Quigley C, Mariani MM, Malm T. et al. Nuclear receptors license phagocytosis by trem2+ myeloid cells in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6532–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4586-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Skerrett R, Malm T, Landreth G. Nuclear receptors in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis; 2014. p. 72. PA: 104-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qiu WQ, Folstein MF. Insulin, insulin-degrading enzyme and amyloid-beta peptide in Alzheimer's disease: review and hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:190–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagele RG, D'Andrea MR, Lee H, Venkataraman V, Wang HY. Astrocytes accumulate A beta 42 and give rise to astrocytic amyloid plaques in Alzheimer disease brains. Brain Res. 2003;971:197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lasagna-Reeves CA, Kayed R. Astrocytes contain amyloid-beta annular protofibrils in Alzheimer's disease brains. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3052–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.