Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are found not only in mammals but also in other organisms, including viruses. Recent findings suggest that lncRNAs play various regulatory roles in multiple major biological and pathological processes. During viral life cycles, lncRNAs are involved in a series of steps, including enhancing viral gene expression, promoting viral replication and genome packaging, boosting virion release, maintaining viral latency and assisting viral transformation; additionally, lncRNAs antagonize host antiviral innate immune responses. In contrast to proteins that function in viral infection, lncRNAs are expected to be novel targets for the modulation of all types of biochemical processes due to their broad characteristics and profound influence. This review highlights our current understanding of the regulatory roles of lncRNAs during viral infection processes with an emphasis on the potential usefulness of lncRNAs as a target for viral intervention strategies, which could have therapeutic implications for the application of a clinical approach for the treatment of viral diseases.

Keywords: lncRNA, Viral life cycle, Gene regulation, Viral replication, Virus intervention

1. Introduction

Viruses are important infectious agents that interfere with the molecular process of gene expression in the host cell. Therefore, an understanding of the mechanisms by which viruses adapt to the host cellular environment and enhance the expression of specific viral genes that control pathogenicity will provide basic information concerning cellular processes during viral infection. Although the majority of factors that are known to regulate the viral life cycle are proteins, a growing number of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been verified to function in these processes [1]. Historically, genes of non-coding RNAs have been regarded as “junk DNA”. However, this type of long non-coding transcript has recently risen to prominence as a surprisingly versatile regulator of gene expression. The functional diversity of the mere handful of validated lncRNAs indicates the vast regulatory potential of these silent biomolecules.

During viral infection, viruses generate lncRNAs to facilitate virus-induced cytopathicity and pathogenicity [2]. Additionally, host lncRNA expression is profoundly influenced by viral infections. For example, 4729 lncRNAs are upregulated and 6588 are downregulated during human foamy virus (HFV) infection of H293 cells [3]. Additionally, researchers discovered 504 differentially regulated lncRNAs in a whole transcriptome analysis of SARS-CoV-infected mouse lung tissue [4], and more than 4800 lncRNAs were differentially expressed in rhabdomyosarcoma cells infected with enterovirus 71 [5]. These findings suggest that widespread differential expression of lncRNAs occurs in response to viral infection and the potential roles of these dysregulated lncRNAs in the viral life cycle.

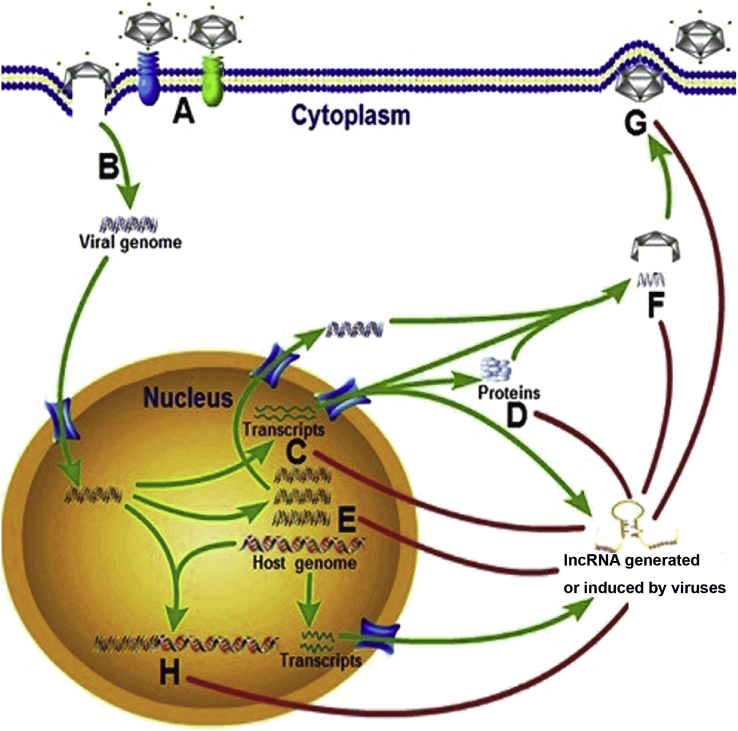

In this review, we describe the biological roles of lncRNAs generated by viruses and induced during the viral life cycle (Fig. 1) and discuss the potential usefulness of lncRNAs as therapeutic targets. This review shows that viruses have evolved a unique strategy to facilitate their life cycle via generating or inducing lncRNA production, which may have important consequences for the application of clinical approaches for the treatment of viral diseases.

Fig. 1.

A diagram highlighting the regulatory roles of lncRNAs in viral life cycles. Once virus enters the host cell by binding to receptors of the cell surface (A and B), lncRNAs generated or induced by viruses facilitate its life cycles through enhancing viral gene transcription (C) and translation (D), promoting viral replication (E) and genome packaging (F), boosting virion release (G) and maintaining viral latency (H).

2. Enhancing viral gene expression

Once a virus reaches the appropriate cell compartment, the viral genome must direct the expression of “early” proteins, which will enable genome replication, and “late” proteins, which are used to package the viral genome and assemble the capsid. In cells infected with the dengue or kunjin viruses, subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA), which is a lncRNA that is incompletely degraded from the viral genomic RNA presumably by the cellular 5’ - 3′ exoribonuclease XRN1, inhibits XRN1 activity and alters host mRNA stability. This effect may assist the stabilization of viral transcripts and disrupt the regulation of host cell gene expression [6].

For DNA viruses, polyadenylated nuclear (PAN) RNA, which is a lncRNA encoded by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) genome, can transcriptionally activate KSHV gene expression by physically interacting with the KSHV genome [7]. Alternatively, PAN RNA can relieve gene suppression by acting as a molecular scaffold for chromatin modifying enzymes to remove the H3K27me3 mark [8], which is required for the production of late viral proteins, by binding to the host poly(A)-binding protein C1 (PABPC1) to regulate mRNA stability and translation efficiency [9]. Moreover, adenovirus virus-associated RNA (VARNA) I is involved in the selective translation of viral mRNA and the shut-off of host cell protein synthesis by inhibiting the cleavage of double-stranded RNA and the inactivation of DAI, which is an eIF-2 kinase known to be a suppressor of protein translation initiation [10], [11]. In addition to lncRNAs encoded by viral genomes, NEAT1 (nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1) is a cellular lncRNA that functions as a scaffold for paraspeckle formation [12], [13], [14] and is induced by viral infection [15], [16], [17]. Recently, we found that NEAT1 binds to viral genes and increases viral gene expression and viral replication [18].

3. Promoting viral replication

Many viruses must continually replicate to maintain themselves. Generally, DNA viruses replicate their genomes directly to DNA, whereas RNA viruses replicate their genomes directly to RNA. However, some DNA viruses copy their genomes via an RNA intermediate, and some RNA viruses copy their genomes via a DNA intermediate. sfRNA has been shown to regulate viral gene expression and is required for efficient viral replication and cytopathicity in cells infected with West Nile virus Kunjin (WNV KUN) [19] and yellow fever virus [20]. In contrast, sfRNA plays a negative role in viral replication and translation in cells infected with Japanese encephalitis virus [21]. Furthermore, KSHV PAN RNA associates with the demethylases UTX and JMJD3 to activate lytic replication through a physical interaction with the viral genome [22].

4. Promoting viral assembly and boosting virion release

As part of the viral life cycle, the genome packaging and virion release processes are initiated by tethering of viral proteins by the viral genome into new infective progeny viruses within the infected cell. In moloney murine leukemia virus (MLV)-infected cells, the mY1 and mY3 RNAs, which are non-coding RNA polymerase III transcripts that are normally complexed with the Ro60 and La proteins in host cells, are selected for encapsidation and assist with viral RNA biogenesis and quality control [23]. Additionally, sfRNA has been shown to be essential for ensuring specific genome packaging in many flaviviruses. For instance, in WNV KUN-infected cells, the plaque size and virus growth in mammalian and mosquito cells correlated with the generation and amount of full-length sfRNA, showing that the production of abundant amounts of full-length sfRNA was essential for efficient viral packaging and virion release [2]. Furthermore, in Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-infected cells, sfRNA promote the packaging and release of virions for the next infectious cycle by shutting down both antigenome synthesis and JEV translation [21]. In our study, we found that the herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) glycoprotein density and intensity were much lower in NEAT1-knockdown HeLa cells than in the control cells, suggesting that NEAT1 influenced HSV-1 virion release [18].

5. Maintaining viral latency

Some viruses undergo a lysogenic cycle where the viral genome is incorporated into a specific location in the host's chromosome by genetic recombination. Thus, the viral genome is replicated whenever the host divides. In most situations, the concerted effort of the innate and adaptive responses is effective in eliminating the pathogen. However, in some cases, the acute resolution of infection is incomplete and viral persistence results. Herpes simplex virus, Heliothis zea nudivirus 1 (HzNV-1), adenovirus virus and Theiler's virus are hallmark examples of infections that develop lifelong viral persistence by “hiding” from the immune response. In contrast to the many viral translated and induced proteins involved in maintaining persistent infections by direct inhibition of T cell responses and/or by down-regulating antigen recognition molecules [24], [25], some lncRNAs have been shown to be responsible for derailing the immune response to permit viral persistence. Tmevpg1, which is a long intergenic non-coding RNA, controls persistent infection with Theiler's virus by positively regulating IFN-gamma expression; this process is dependent on Stat4 and T-bet, which are the two transcription factors that drive the Th1 differentiation program [26], [27], [28].

Additionally, some non-coding genes can act as bi-functional factors to promote viral entry or the maintenance of a latent state. The non-coding gene Pag1 blocks the HzNV-1 gene hhi to establish viral latency by encoding two miRNAs that target and degrade the hhi1 transcript, which is a stimulator of apoptosis [29], [30]. PAT1, which is another non-coding transcript encoded by pag1, has also been verified to be involved in persistent infection in cells. However, whether PAT1 is directly responsible for the establishment of persistent infection or only enhances this process is unknown [31]. For HSV-1, the latency-associated non-coding transcript (LAT) is the only viral gene that is expressed during latent infection in neurons. In these cells, LAT exerts its anti-apoptotic effect [32] and blocks the function of early genes to maintain latency by proceeding into and functioning as a microRNA (miR-LAT) that down-regulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 and SMAD3 expression [33]. Moreover, adenovirus virus-associated RNAs (VA RNAs) are processed into small RNAs that are expressed at high levels and may be associated with the ability of this virus to efficiently establish a persistent infection [34]. One VA RNA-derived small RNAs (mivaRNA), mivaRNAI-138 can inhibit cell apoptosis by targeting and binding TIA-1, which is a well-characterized factor that activates apoptosis [35], [36]. Importantly, mRNAs associated with viral replication are essentially unaffected by these small non-coding RNAs [37].

6. Assisting viral-induced cellular transformation

Viral transformation most commonly refers to the virus-induced malignant transformation of an animal cell in a body or cell culture and can impose characteristically determinable features upon a cell. Typical phenotypic changes include a high saturation density, anchorage-independent growth, loss of contact inhibition, loss of orientated growth, immortalization, and disruption of the cell's cytoskeleton, which are favorable for the viral life cycle. Currently, viruses drive cellular transformation through their ability to alter cellular gene expression, signaling pathways, and the cell cycle [38].

A study on the regulatory roles of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes-virus PAN RNA on viral and cellular gene expression showed that PAN RNA could maintain cellular transformation by affecting cellular gene expression, resulting in an enhanced growth phenotype, higher cell densities, and increased survival [7]. In Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated carcinogenesis, EBV-miR-BART6-3p inhibited EBV-associated cancer cell migration and invasion by targeting and downregulating the lncRNA LOC553103 [39]. The Epstein-Barr early RNAs (EBERs) are two abundantly expressed and virally encoded lncRNAs in latently EBV-infected cells. A recent study of the in vivo effects of EBERs in cellular gene expression demonstrated that the EBERs regulated a variety of host cell genes, including deaminase, protein kinase, cell adhesion, regulation of apoptosis, and receptor signaling [40]. Moreover, EBER-1 enhanced host cell protein synthesis by blocking the activation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent eukaryotic initiation factor 2a (eIF-2a) protein kinase DAI (p68) [41]. EBERs have also been shown to impact the growth potential of Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cells by mediating the stable relocalization of L22 from the nucleoli to the nucleoplasm [42] and inducing interleukin-10, which is a growth factor for virally infected cells [43]. These findings contribute to the potential ability of EBERs to establish or maintain a transformed phenotype in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma [44] and in EBV-infected NIH 3T3 cells [45]. However, EBER-2 but not EBER-1 plays a critical role in viral-induced growth transformation in EBV-infected B cells [46].

7. Imparting resistance to the antiviral immune responses

The intracellular antiviral immune response in host cells provides essential protection against virus infection. The innate immune response can be triggered by the interaction between host cell pathogen recognition receptors and viral surface proteins and the presence of viral products, such as nucleic acids, in the host cell. However, some lncRNA generated by viruses have shown their roles in imparting resistance to the antiviral immune responses (Table 1). As the predominant antiviral response against invading viruses, RNA interference (RNAi) is an intracellular process that is induced by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) that results in the cleavage of both cellular and viral mRNAs into small interfering dsRNA (siRNA) [47]. In the presence of dsRNA, protein kinase RNA-activated (PKR) is autophosphorylated; in turn, PKR phosphorylates its substrate (eukaryotic initiation factor 2α), leading to translation cessation [48]. Recently, some virally encoded lncRNAs have been shown to be involved in the RNAi pathway via the modulation of PKR activity for viral survival. EBERs contribute to the maintenance of malignant phenotypes by binding PKR and abrogating its activity [49]. Additionally, the adenovirus-associated RNAs VAI RNA and VAII RNA can attenuate the RNAi pathway by directly inhibiting PKR activation [50], [51] and functioning as competitive substrates to squelch Dicer and interfere with its activity [52]. Another RNA encoded by the West Nile and dengue viruses (sfRNA) not only efficiently suppressed siRNA- and miRNA-induced RNAi pathways in both mammalian and insect cells partially by disturbing dsRNA cleavage [53] but also interfered with the RNAi pathway by inhibiting the RNase Dicer [54].

Table 1.

LncRNAs that impart resistance to the antiviral immune responses.

| Name | Source (Name, Family name, Classification) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| EBER1and EBER2 | Epstein-Barr virus, Herpesviridae, dsDNA | Binding PKR and abrogating its activity |

| VAI RNA and VAII RNA | Human adenovirus, Adenoviridae, dsDNA | InhibitingPKR activation; Interfering with the activity of Dicer |

| sfRNA | West Nile, Flaviviridae, ssRNA | Disturbing dsRNA cleavage; Inhibiting the RNase Dicer; Repressing IFN expression |

| sfRNA | Dengue viruses, Flaviviridae, ssRNA | Disturbing dsRNA cleavage; Inhibiting the RNase Dicer |

| sfRNA | Japanese encephalitis virus, Flaviviridae, ssRNA | Preventing host cells from apoptosis; Obstructing interferon production, nuclear translocation and IRF-3 activation |

| Beta 2.7 | Human cytomegalovirus, Herpesviridae, dsDNA | Preventing the host cell stress response, apoptosis and metabolic dysfunction |

DsDNA: double-stranded DNA; ssRNA: single-stranded RNA.

In addition to the RNAi pathway, antiviral substances, such as interferons (IFNs), can be triggered by the presence of certain viruses. The roles of these antiviral substances are to protect adjacent cells from infection and activate T cell-mediated immunity by initiating apoptosis and autophagy [55], [56]. To dissect the mechanism by which viruses perturb the IFN signaling pathway, Schuessler A et al. showed that sfRNA derived from West Nile virus contributed to viral evasion of the type I interferon-mediated antiviral response by blunting the increase in IFN expression provoked by viral infection [57]. Furthermore, another study showed that sfRNA played a role against host cell antiviral responses by preventing the cells from undergoing apoptosis and thus contributed to viral persistence by obstructing interferon production, nuclear translocation and IRF-3 activation, which is a key factor in the induction of early antiviral responses [58]. These effects of sfRNA may protect latently infected host cells from the anti-viral action of IFNs.

Moreover, virus-infected cells may initiate apoptosis to prevent the spread of infection to other cells. As a countermeasure, human cytomegalovirus encodes Beta 2.7, which is the most abundantly transcribed early gene, to prevent the host cell stress response and apoptosis by binding to components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex; (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-ubiquinone oxido-reductase). This interaction is also important for the stabilization of the mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial ATP production and the prevention of metabolic dysfunction, which are essential for the completion of the viral life cycle [59]. The psoriasis susceptibility-related RNA gene induced by stress (PRINS) is a lncRNA overexpressed by herpes simplex viral infection [60]; upregulated PRINS can decrease cell apoptosis by regulating the anti-apoptotic G1P3 protein [61].

In addition to the innate antiviral response, an important outcome of viral infection is the development of a virus-specific immune response triggered by viral antigens. Accumulating evidence suggests that lncRNAs are important regulators of the differentiation and functions of T cells, which orchestrate the adaptive immune responses [62], [63] and have been implicated in antigen receptor diversification [64]. Thus, lncRNAs are likely to play a role in regulating antiviral adaptive immunity.

8. Discussion

It is becoming apparent that lncRNAs can perform vital roles in the control of a variety of processes by regulating gene expression. Recently, more than 20% of lncRNAs were found to contain one or more Alu elements, which are critical players in gene regulation and molecular pathways [65], [66]. A study showed that Alu sequences embedded in both lncRNAs and mRNAs played crucial roles in targeted mRNA decay via short imperfect base pairing. This imperfect base pairing may extend the potential ability of lncRNAs to regulate protein synthesis [67], although tens of thousands of human lncRNAs have not been shown to direct protein synthesis. Moreover, the NEAT1 lncRNA, which is up-regulated in virus-infected cells, has been demonstrated to mediate the nuclear retention process [68], which may help explain the essential roles played by lncRNAs in viral life cycles following accumulation in the nucleus [69]. Furthermore, thousands of lncRNAs have been found to regulate gene expression by binding PRC2, and additional lncRNAs are bound by other chromatin-modifying complexes [70].

As a mediator of gene expression, lncRNAs can generate small ncRNAs less than 200 nts in length, such as tRNAs and miRNAs, to enlarge their regulatory power. MALAT1 (metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1) is a lncRNA that is specifically retained in the nucleus [71] and has been found to be involved in not only the assembly, modification and/or storage of the pre-mRNA processing machinery [72] but also the generation of a short tRNA-like ncRNA [MALAT1-associated small cytoplasmic RNA (mascRNA)] through cleavage by RNase P and RNase Z. After processing, the long MALAT1 transcript remains in the nucleus, whereas mascRNA is exported to the cytoplasm [73]. This regulatory mechanism may allow cytoplasmic components to sense the differential MALAT1 expression in the nucleus and may be involved in translational regulation by serving as a tRNA mimic. As another example, H19 appears to be a bi-functional RNA acting as both an lncRNA and a miRNA precursor that is subsequently processed into miR-675 by cleavage by the RNase III enzymes Drosha and Dicer [74]. Although H19 and miR-675 are regarded as a tumor suppressor and an oncogene, respectively [75], the mechanism by which H19 exerts its functions through the generation of miRNAs raises the possibility that some other lncRNAs might also perform their biological roles by giving rise to miRNAs.

In addition to functioning as a small ncRNA precursor, growing evidence has demonstrated that lncRNAs may function as “miRNA sponges” with diverse and far-reaching effects. HULC, which is a highly up-regulated lncRNA in liver cancer, contains a motif with a sequence targeted by miR-372. HULC has been reported to initiate a cascade of molecular events to increase chromatin accessibility for general transcription by recruiting miR-372 and attenuating its chromatin modification activity [76]. Recently, Wang et al. illustrated that the lncRNA linc-RoR functioned as a key competing endogenous RNA by preventing core transcription factors (TFs) from functioning in miRNA-mediated suppression and maintaining embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation by targeting and antagonizing miR-145, which is a repressor of the translation of the core TF mRNAs [77]. To investigate the regulatory interactions between RNA classes, the interaction network between lncRNAs, miRNAs and mRNAs has been well-characterized computationally and experimentally [78], [79]. Systematic transcriptome-wide analysis of the multiple classes of RNAs suggests widespread regulatory roles for lncRNAs and indicates the potential ability of lncRNAs to act as important mediators of various biological processes.

Through deep-sequencing technology, lncRNAs have been reported to play crucial roles in viral infection processes. Moreover, lncRNAs may act as a “bridge” that interlinks two types of viruses. For instance, in human parvovirus B19 (B19V)-infected cells, the adenoviral VA I RNA stimulates B19V capsid protein expression most likely by inhibiting the dsRNA-induced activation of PKR through competition for the PKR RNA-binding domain [80]. In HIV subtype E-infected pediatric patients, EBERs are co-expressed with the HIV core protein p24, which plays an important role in the interaction with host proteins during HIV-1 adsorption, membrane fusion, and entry, in surgical lung biopsies [81]. Therefore, lncRNAs may be a better target for viral intervention strategies due to their active regulatory roles in facilitating the host environment for viruses. A study reported that the ribosomal protein L22 might be able to buffer cells against the ability of EBER-1 to induce cellular transformation and impart resistance to the antiviral immune response by competitively binding EBER-1 [82]. High-level expression of viral EBER-1 can lead to the resistance of cells to physiological stresses and pro-apoptotic stimuli and can confer aspects of the transformed phenotype, resulting in outright tumorigenicity in some cases [46], [83] Moreover, the COX-2 inhibitor etodolac induced apoptosis via a Bcl-2-regulated pathway through inhibition of EBER expression [84]. These findings indicated the potential usefulness of lncRNAs as targets for viral intervention strategies, which could have therapeutic implications for the application of clinical approaches for the treatment of viral diseases. Currently, many gene therapeutic approaches in clinical trials are promising, such as small interfering RNAs, antisense oligonucleotides, ribozymes, etc. However, the major drawback of these approaches is that their function lacks persistence. Recently, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system have the advantage of affecting interested gene permanently [85] and many viruses has been proven to be sensitive to this system [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91]. Therefore, targeting lncRNA involved in viral life cycle with (CRISPR)-Cas9 technology may have better therapeutic utility for control of virus infection.

In this review, we have thoroughly described the biological roles of lncRNAs in enhancing viral gene expression, promoting viral replication and genome packaging, boosting virion release, maintaining viral latency, assisting viral transformation, and antagonizing the host antiviral innate immune response. More importantly, in view of their regulatory roles, lncRNAs have been regarded as targets to block the facilitation of viral infection. Since the viral life cycle and the mechanism of the host antiviral response are clearer, targeting lncRNAs for prophylactic or therapeutic ends is an attractive alternative. With further advances in our understanding of the molecular details that govern the viral life cycle and immune response, this review hopefully revealed information that will help expand viral intervention strategies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [31371315], Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China [2012ZX09102301-019] and Basic Research Fund of Shenzhen [JCYJ20150724173156330].

References

- 1.Conrad N.K., Fok V., Cazalla D., Borah S., Steitz J.A. The challenge of viral snRNPs. Cold Spring Harb. Symposia Quantitative Biol. 2006;71:377–384. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pijlman G.P., Funk A., Kondratieva N., Leung J., Torres S., van der Aa L. A highly structured, nuclease-resistant, noncoding RNA produced by flaviviruses is required for pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu S., Dong L., Shi Y., Chen L., Yuan P., Wang S., Li Z., Sun Y., Han S., Yin J., Peng B., He X., Liu W. The novel landscape of long non-coding RNAs in response to human foamy virus infection characterized by RNA-seq. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2016 Oct 18 doi: 10.1089/AID.2016.0156. [PMID:27750433] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng X., Gralinski L., Armour C.D., Ferris M.T., Thomas M.J., Proll S. Unique signatures of long noncoding RNA expression in response to virus infection and altered innate immune signaling. mBio. 2010;5:1. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00206-10. e00206–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin Z., Guan D., Fan Q., Su J., Zheng W., Ma W. lncRNA expression signatures in response to enterovirus 71 infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;430:629–633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon S.L., Anderson J.R., Kumagai Y., Wilusz C.J., Akira S., Khromykh A.A. A noncoding RNA produced by arthropod-borne flaviviruses inhibits the cellular exoribonuclease XRN1 and alters host mRNA stability. Rna. 2012;18:2029–2040. doi: 10.1261/rna.034330.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossetto C.C., Tarrant-Elorza M., Verma S., Purushothaman P., Pari G.S. Regulation of viral and cellular gene expression by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus polyadenylated nuclear RNA. J. Virol. 2013;87:5540–5553. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03111-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juranic Lisnic V., Babic Cac M., Lisnic B., Trsan T., Mefferd A., Das Mukhopadhyay C., Trgovcich J. Dual analysis of the murine cytomegalovirus and host cell transcriptomes reveal new aspects of the virus-host cell interface. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(9):e1003611. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borah S., Darricarrere N., Darnell A., Myoung J., Steitz J.A. A viral nuclear noncoding RNA binds re-localized poly, A. binding protein and is required for late KSHV gene expression. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002300. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Malley R.P., Duncan R.F., Hershey J.W., Mathews M.B. Modification of protein synthesis initiation factors and the shut-off of host protein synthesis in adenovirus-infected cells. Virology. 1989;168:112–118. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thimmappaya B., Weinberger C., Schneider R.J., Shenk T. Adenovirus VAI RNA is required for efficient translation of viral mRNAs at late times after infection. Cell. 1982;31:543–551. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clemson C.M., Hutchinson J.N., Sara S.A., Ensminger A.W., Fox A.H., Chess A. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao Y.S., Sunwoo H., Zhang B., Spector D.L. Direct visualization of the co-transcriptional assembly of a nuclear body by noncoding RNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:95–101. doi: 10.1038/ncb2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawa S., Naganuma T., Shioi G., Hirose T. Paraspeckles are subpopulation-specific nuclear bodies that are not essential in mice. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:31–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201011110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imamura K., Imamachi N., Akizuki G., Kumakura M., Kawaguchi A., Nagata K., Kato A., Kawaguchi Y., Sato H., Yoneda M., Kai C., Yada T., Suzuki Y., Yamada T., Ozawa T., Kaneki K., Inoue T., Kobayashi M., Kodama T., Wada Y., Sekimizu K., Akimitsu N. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1-dependent SFPQ relocation from promoter region to paraspeckle mediates IL8 expression upon immune stimuli. Mol. Cell. 2014 Feb 6;53(3):393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saha S., Murthy S., Rangarajan P.N. Identification and characterization of a virus-inducible non-coding RNA in mouse brain. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:1991–1995. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81768-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q., Chen C.Y., Yedavalli V.S., Jeang K.T. NEAT1 long noncoding RNA and paraspeckle bodies modulate HIV-1 posttranscriptional expression. MBio. 2013;4 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00596-12. e00596–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Ziqiang, Fan Ping, Zhao Yiwan, Zhang Shikuan, Lu Jinhua, Xie Weidong, Jiang Yuyang, Lei Fan, Xu Naihan, Zhang Yaou. NEAT1 modulates herpes simplex Virus-1 replication by regulating viral gene transcription. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2398-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funk A., Truong K., Nagasaki T., Torres S., Floden N., Balmori Melian E. RNA structures required for production of subgenomic flavivirus RNA. J. Virol. 2010;84:11407–11417. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01159-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva P.A., Pereira C.F., Dalebout T.J., Spaan W.J., Bredenbeek P.J. An RNA pseudoknot is required for production of yellow fever virus subgenomic RNA by the host nuclease XRN1. J. Virol. 2010;84:11395–11406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan Y.H., Nadar M., Chen C.C., Weng C.C., Lin Y.T., Chang R.Y. Small noncoding RNA modulates Japanese encephalitis virus replication and translation in trans. Virol. J. 2011;8:492. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossetto C.C., Pari G. KSHV PAN RNA associates with demethylases UTX and JMJD3 to activate lytic replication through a physical interaction with the virus genome. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002680. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia E.L., Onafuwa-Nuga A., Sim S., King S.R., Wolin S.L. Telesnitsky A. Telesnitsky, Packaging of host mY RNAs by murine leukemia virus may occur early in Y RNA biogenesis. J. Virol. 2009;83:12526–12534. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01219-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klenerman P., Hill A. T cells and viral persistence: lessons from diverse infections. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:873–879. doi: 10.1038/ni1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slobedman B., Barry P.A., Spencer J.V., Avdic S., Abendroth A. Virus-encoded homologs of cellular interleukin-10 and their control of host immune function. J. Virol. 2009;83:9618–9629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vigneau S., Levillayer F., Crespeau H., Cattolico L., Caudron B., Bihl F. Homology between a 173-kb region from mouse chromosome 10, telomeric to the Ifng locus, and human chromosome 12q15. Genomics. 2001;78:206–213. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collier S.P., Collins P.L., Williams C.L., Boothby M.R., Aune T.M. Cutting edge: influence of Tmevpg1, a long intergenic noncoding RNA, on the expression of Ifng by Th1 cells. J. Immunol. 2012;189:2084–2088. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vigneau S., Rohrlich P.S., Brahic M., Bureau J.F. Tmevpg1, a candidate gene for the control of Theiler's virus persistence, could be implicated in the regulation of gamma interferon. J. Virol. 2003;77:5632–5638. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5632-5638.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Y.L., Wu C.P., Liu C.Y., Lee S.T., Lee H.P., Chao Y.C. Heliothis zea nudivirus 1 gene hhi1 induces apoptosis which is blocked by the Hz-iap2 gene and a noncoding gene, pag1. J. Virol. 2011;85:6856–6866. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01843-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y.L., Wu C.P., Liu C.Y., Hsu P.W., Wu E.C., Chao Y.C. A non-coding RNA of insect HzNV-1 virus establishes latent viral infection through microRNA. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:60. doi: 10.1038/srep00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao Y.C., Lee S.T., Chang M.C., Chen H.H., Chen S.S., Wu T.Y. A 2.9-kilobase noncoding nuclear RNA functions in the establishment of persistent Hz-1 viral infection. J. Virol. 1998;72:2233–2245. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2233-2245.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta A., Gartner J.J., Sethupathy P., Hatzigeorgiou A.G., Fraser N.W. Anti-apoptotic function of a microRNA encoded by the HSV-1 latency-associated transcript. Nature. 2006;442:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature04836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Umbach J.L., Kramer M.F., Jurak I., Karnowski H.W., Coen D.M., Cullen B.R. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008;454:780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu N., Segerman B., Zhou X., Akusjarvi G. Adenovirus virus-associated RNAII-derived small RNAs are efficiently incorporated into the rna-induced silencing complex and associate with polyribosomes. J. Virol. 2007;81:10540–10549. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00885-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aparicio O., Carnero E., Abad X., Razquin N., Guruceaga E., Segura V. Adenovirus VA RNA-derived miRNAs target cellular genes involved in cell growth, gene expression and DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:750–763. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forch P., Valcarcel J. Molecular mechanisms of gene expression regulation by the apoptosis-promoting protein TIA-1. Apoptosis An Int. J. Program. Cell Death. 2001;6:463–468. doi: 10.1023/a:1012441824719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamel W., Segerman B., Oberg D., Punga T., Akusjarvi G. The adenovirus VA RNA-derived miRNAs are not essential for lytic virus growth in tissue culture cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4802–4812. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raab-Traub N. Novel mechanisms of EBV-induced oncogenesis. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He Baoyu, Li Weiming, Wu Yingfen, Wei Fang, Gong Zhaojian, Bo Hao, Wang Yumin, Li Xiayu, Xiang Bo, Guo1 Can, Liao Qianjin, Chen Pan, Zu Xuyu, Zhou Ming, Ma Jian, Li Xiaoling, Li Yong, Li Guiyuan, Xiong Wei, Zeng Zhaoyang. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded miR-BART6-3p inhibits cancer cell metastasis and invasion by targeting long non-coding RNA LOC553103. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2353. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gregorovic G., Bosshard R., Karstegl C.E., White R.E., Pattle S., Chiang A.K. Cellular gene expression that correlates with EBER expression in Epstein-Barr Virus-infected lymphoblastoid cell lines. J. Virol. 2011;85:3535–3545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02086-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke P.A., Sharp N.A., Clemens M.J. Translational control by the Epstein-Barr virus small RNA EBER-1. Reversal of the double-stranded RNA-induced inhibition of protein synthesis in reticulocyte lysates. Eur. J. Biochem./FEBS. 1990;193:635–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houmani J.L., Davis C.I., Ruf I.K. Growth-promoting properties of Epstein-Barr virus EBER-1 RNA correlate with ribosomal protein L22 binding. J. Virol. 2009;83:9844–9853. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01014-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitagawa N., Goto M., Kurozumi K., Maruo S., Fukayama M., Naoe T. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded poly, A.,-. RNA supports Burkitt's lymphoma growth through interleukin-10 induction. EMBO J. 2000;19:6742–6750. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao Y., Minter H.A., Chen X., Reynolds G.M., Bromley M., Arrand J.R. Heterogeneity of HLA and EBER expression in Epstein-Barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. International journal of cancer. J. Int. Du Cancer. 2000;88:949–955. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001215)88:6<949::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laing K.G., Elia A., Jeffrey I., Matys V., Tilleray V.J., Souberbielle B. In vivo effects of the Epstein-Barr virus small RNA EBER-1 on protein synthesis and cell growth regulation. Virology. 2002;297:253–269. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Y., Maruo S., Yajima M., Kanda T., Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus, EBV.-encoded RNA 2, EBER2. but not EBER1 plays a critical role in EBV-induced B-cell growth transformation. J. Virol. 2007;81:11236–11245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00579-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ketzinel-Gilad M., Shaul Y., Galun E. RNA interference for antiviral therapy. J. Gene Med. 2006;8:933–950. doi: 10.1002/jgm.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia M.A., Gil J., Ventoso I., Guerra S., Domingo E., Rivas C. Impact of protein kinase PKR in cell biology: from antiviral to antiproliferative action. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR. 2006;70:1032–1060. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00027-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nanbo A., Yoshiyama H., Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded poly, A.- RNA confers resistance to apoptosis mediated through Fas by blocking the PKR pathway in human epithelial intestine 407 cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:12280–12285. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12280-12285.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharp T.V., Schwemmle M., Jeffrey I., Laing K., Mellor H., Proud C.G. Comparative analysis of the regulation of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR by Epstein-Barr virus RNAs EBER-1 and EBER-2 and adenovirus VAI RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4483–4490. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.19.4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKenna S.A., Kim I., Liu C.W., Puglisi J.D. Uncoupling of RNA binding and PKR kinase activation by viral inhibitor RNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:1270–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersson M.G., Haasnoot P.C., Xu N., Berenjian S., Berkhout B., Akusjarvi G. Suppression of RNA interference by adenovirus virus-associated RNA. J. Virol. 2005;79:9556–9565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9556-9565.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnettler E., Sterken M.G., Leung J.Y., Metz S.W., Geertsema C., Goldbach R.W. Noncoding flavivirus RNA displays RNA interference suppressor activity in insect and Mammalian cells. J. Virol. 2012;86:13486–13500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01104-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green A.M., Beatty P.R., Hadjilaou A., Harris E. Innate immunity to dengue virus infection and subversion of antiviral responses. J. Mol. Biol. 2014;426:1148–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yordy B., Iwasaki A. Cell type-dependent requirement of autophagy in HSV-1 antiviral defense. Autophagy. 2013;9:236–238. doi: 10.4161/auto.22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yordy B., Iijima N., Huttner A., Leib D., Iwasaki A. A neuron-specific role for autophagy in antiviral defense against herpes simplex virus. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:334–345. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schuessler A., Funk A., Lazear H.M., Cooper D.A., Torres S., Daffis S. West Nile virus noncoding subgenomic RNA contributes to viral evasion of the type I interferon-mediated antiviral response. J. Virol. 2012;86:5708–5718. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00207-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang R.Y., Hsu T.W., Chen Y.L., Liu S.F., Tsai Y.J., Lin Y.T. Japanese encephalitis virus non-coding RNA inhibits activation of interferon by blocking nuclear translocation of interferon regulatory factor 3. Veterinary Microbiol. 2013;166:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reeves M.B., Davies A.A., McSharry B.P., Wilkinson G.W., Sinclair J.H. Complex I binding by a virally encoded RNA regulates mitochondria-induced cell death. Science. 2007;316:1345–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1142984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sonkoly E., Bata-Csorgo Z., Pivarcsi A., Polyanka H., Kenderessy-Szabo A., Molnar G. Identification and characterization of a novel, psoriasis susceptibility-related noncoding RNA gene. PRINS. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24159–24167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szegedi K., Sonkoly E., Nagy N., Nemeth I.B., Bata-Csorgo Z., Kemeny L. The anti-apoptotic protein G1P3 is overexpressed in psoriasis and regulated by the non-coding RNA, PRINS. Exp. Dermatol. 2010;19:269–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pagani M., Rossetti G., Panzeri I., de Candia P., Bonnal R.J., Rossi R.L. Role of microRNAs and long-non-coding RNAs in CD4+ T-cell differentiation. Immunol. Rev. 2013;253:82–96. doi: 10.1111/imr.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pang K.C., Dinger M.E., Mercer T.R., Malquori L., Grimmond S.M., Chen W. Genome-wide identification of long noncoding RNAs in CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2009;182:7738–7748. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teng G., Papavasiliou F.N. Long noncoding RNAs: implications for antigen receptor diversification. Adv. Immunol. 2009;104:25–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)04002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen L.L., DeCerbo J.N., Carmichael G.G. Alu element-mediated gene silencing. EMBO J. 2008;27:1694–1705. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mariner P.D., Walters R.D., Espinoza C.A., Drullinger L.F., Wagner S.D., Kugel J.F. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gong C., Maquat L.E. lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3' UTRs via Alu elements. Nature. 2011;470:284–288. doi: 10.1038/nature09701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen L.L., Carmichael G.G. Altered nuclear retention of mRNAs containing inverted repeats in human embryonic stem cells: functional role of a nuclear noncoding RNA. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhong W., Wang H., Herndier B., Ganem D. Restricted expression of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, human herpesvirus 8 genes in Kaposi sarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:6641–6646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khalil A.M., Guttman M., Huarte M., Garber M., Raj A., Rivea Morales D. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:11667–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hutchinson J.N., Ensminger A.W., Clemson C.M., Lynch C.R., Lawrence J.B., Chess A. A screen for nuclear transcripts identifies two linked noncoding RNAs associated with SC35 splicing domains. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamond A.I., Spector D.L. Nuclear speckles: a model for nuclear organelles. Nature reviews. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:605–612. doi: 10.1038/nrm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilusz J.E., Freier S.M. D.L. Spector.3' end processing of a long nuclear-retained noncoding RNA yields a tRNA-like cytoplasmic RNA. Cell. 2008;135:919–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cai X., Cullen B.R. The imprinted H19 noncoding RNA is a primary microRNA precursor. Rna. 2007;13:313–316. doi: 10.1261/rna.351707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smits G., Mungall A.J., Griffiths-Jones S., Smith P., Beury D., Matthews L. Conservation of the H19 noncoding RNA and H19-IGF2 imprinting mechanism in therians. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:971–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang J., Liu X., Wu H., Ni P., Gu Z., Qiao Y. CREB up-regulates long non-coding RNA, HULC expression through interaction with microRNA-372 in liver cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5366–5383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y., Xu Z., Jiang J., Xu C., Kang J., Xiao L. Endogenous miRNA sponge lincRNA-RoR regulates Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 in human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Dev. Cell. 2013;25:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jalali S., Bhartiya D., Lalwani M.K., Sivasubbu S., Scaria V. Systematic transcriptome wide analysis of lncRNA-miRNA interactions. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li J.H., Liu S., Zhou H., Qu L.H., Yang J.H. starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D92–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Winter K., von Kietzell K., Heilbronn R., Pozzuto T., Fechner H., Weger S. Roles of E4orf6 and VA I RNA in adenovirus-mediated stimulation of human parvovirus B19 DNA replication and structural gene expression. J. Virol. 2012;86:5099–5109. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06991-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bhoopat L., Rangkakulnuwat S., Ya-In C., Bhoopat T. Relationship of cell bearing EBER and p24 antigens in biopsy-proven lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia in HIV-1 subtype E infected children. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. AIMM/Official Publ. Soc. Appl. Immunohistochem. 2011;19:547–551. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31821bfc34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Elia A., Vyas J., Laing K.G. M.J. Clemens Ribosomal protein L22 inhibits regulation of cellular activities by the Epstein-Barr virus small RNA EBER-1. Eur. J. Biochem./FEBS. 2004;271:1895–1905. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nanbo A., Inoue K., Adachi-Takasawa K., Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus RNA confers resistance to interferon-alpha-induced apoptosis in Burkitt's lymphoma. EMBO J. 2002;21:954–965. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kobayashi M., Nakamura S., Shibata K., Sahara N., Shigeno K., Shinjo K. Etodolac inhibits EBER expression and induces Bcl-2-regulated apoptosis in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Eur. J. Haematol. 2005;75:212–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Swiech L., Heidenreich M., Banerjee A. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33(1):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yuen K.S. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of Epstein-Barr virus in human cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2015;96(Pt 3):626–636. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang J., Quake S.R. RNA-guided endonuclease provides a therapeutic strategy to cure latent herpesviridae infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:13157–13162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410785111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhen S. In vitro and in vivo growth suppression of human papillomavirus 16-positive cervical cancer cells by CRISPR/Cas9. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;450:1422–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Russell T.A., Stefanovic T., Tscharke D.C. Engineering herpes simplex viruses by infection-transfection methods including recombination site targeting by CRISPR/Cas9 nucleases. J. Virol. Methods. 2015;213:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van Diemen F.R., Kruse E.M., Hooykaas M.J.G. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated genome editing of herpesviruses limits productive and latent infections. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(6):e1005701. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005701. Nelson JA, ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaminski R., Chen Y., Fischer T. Elimination of HIV-1 genomes from human T-lymphoid cells by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22555. doi: 10.1038/srep22555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]