Abstract

Background:

In oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) expression has been noted in the cell membrane throughout the epithelium of the lesion, suggesting its increased expression.

Objectives:

The present study was conducted to evaluate and compare the expression of EMMPRIN in the normal oral mucosa (NOM), different histological grades of oral epithelial dysplasia (OED) and OSCC.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 100 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of NOM (n = 10), 20 cases each of mild, moderate and severe (OED) (n = 60), and 10 cases each of well differentiated, moderately differentiated and poorly differentiated carcinomas (n = 30) were included in the study. The tissues sections were immunohistochemically stained and were evaluated for intensity and area of expression in different groups.

Results:

Out of 60 cases of OED, 29 (48%) cases showed intense dark brown staining in the epithelium. The stroma in 38 (63%) cases showed positive immunoexpression. The expression of EMMPRIN in OSCC revealed intense dark brown staining in 9 (90%) cases of well differentiated, and a decent thereon in 8 (80%) cases of moderately differentiated and 4 (40%) cases of poorly differentiated carcinomas.

Conclusion:

The role of EMMPRIN in precarcinogenesis and early carcinogenesis needs to be studied on considerable sample size. This can enable oncologists to detect cancer at an early stage before it progresses to malignancy.

Keywords: Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, oral epithelial dysplasia, oral squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a global health problem with an incidence rate of 500,000 new cases annually. The malignancy is caused by multifactorial etiology such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, immunodeficiency and viral infections.[1] The premalignant lesions and conditions are common and precede most of the OSCC cases. The variable degrees of epithelial dysplasia present in these lesions are considered as the histopathological marker of premalignancy.[2] Importance has been given to biological markers to predict the malignant potential, as there are controversies on the grading of epithelial dysplasia.[3] Matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) regulate cancer cell migration and are considered critical for malignancy.[4] According to recent studies, a pericellular environment is created by the tumor cell in which the MMPs and other proteases get concentrated. For the progression and metastasis of the tumor, the ability of the tumor cells to invade extracellular matrices are enhanced by MMPs.[5]

The extracellular MMP inducer (EMMPRIN) is the main inducer of MMPs and thus stimulates the MMPs production in the stromal fibroblast. Several MMPs including MMP1, 2, 3, 9, 14 and 15 have been reported to be induced by EMMPRIN.[2] EMMPRIN stimulates the production of hyaluronan by elevating hyaluronan synthases, which is closely associated with the anchorage-independent growth of cancer cells.[2,4] EMMPRIN, in carcinomas, enhances the tumor cell motility with its ability to facilitate the production of MMP and tenascin-C matrix deposition.[6] It is also reported to increase the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in stromal fibroblasts and stimulate tumor angiogenesis.[7]

According to various studies, EMMPRIN is suggested to be an important factor in promoting oral carcinogenesis at its early stage.[6,7] The process involves remodeling of the extracellular matrix and basement membrane of the premalignant lesion.

Although the role of EMMPRIN has been reported in carcinomas, sparse literature is available on its level of expression in different histological grades of oral epithelial dysplasias (OEDs). Therefore, the aim of this research is to assess and compare the immuno-expression of EMMPRIN in oral epithelial dysplasia (OED), oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and normal oral mucosa (NOM). This study, employing EMMPRIN protein, is the first of its kind on Indian subcontinent where the authors attempt to decipher its potential role in early carcinogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample and data collection

A total of 100 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of histologically diagnosed cases of NOM (n = 10) (control group), 20 cases each of mild, moderate and severe OED (n = 60) (study Group I) and 10 cases each of well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (WDSCC), moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (MDSCC) and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (PDSCC; n = 30) (study Group II) were included in the study.

The demographic data such as age, sex, site, habit history, duration and frequency of habit, clinical diagnosis and histopathology were obtained from the Departmental Archives of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, KLE VK Institute of Dental Sciences. Ethical clearance from the institution and a waiver of informed consent was obtained for this retrospective study.

All the tissues were thoroughly evaluated for pathological changes and considered as normal mucosa only with minimal inflammation. Broder's histological grading criteria (Grade 1: Well differentiated, Grade 2: Moderately differentiated and Grade 3: Poorly differentiated) was used to reevaluate all the cases of OSCC and the World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) grading criteria (Grade 1: Mild, Grade 2: Moderate and Grade 3: Severe) was used to reevaluate all the cases of OED. The formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were made into two sections of 4μm thickness each. One of the sections was placed on egg albumin coated slide for the routine hematoxylin and eosin stain. Another section was placed on aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APES)-coated slide for immunohistochemical staining with EMMPRIN antibody (Monoclonal Purified Anti-Human CD-147, 1:200, Clone HIM6, Isotype-Mouse IgG1,κ, Biolegend Lab, San Diego, California). A detection system consisting of super sensitive polymer-horseradish peroxidase (poly-HRP) (Biogenex San Ramon, U.S.A, QD400-60KE) was used.

Immunohistochemistry

The 4μm tissue sections were mounted on APES-coated slides to evaluate the immunoexpression of EMMPRIN. The slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated in xylene, dehydrated in ethanol series and rinsed in distilled water. The sections were incubated in the peroxide block at room temperature for 10 min to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. The slides were incubated with poly-HRP for 30 min followed by rinsing of sections with 300 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To retrieve the heat induced epitope, a staining trough was filled with citrate buffer at pH 6 and then was placed in an EZ retrieval system. Two cycles of 12 min at 96°C were set. When the cycles were complete, the staining trough was cooled at room temperature followed by washing with PBS.

For immunohistochemical staining, the sections were incubated with power block for 15 min. The slides were then incubated with the primary monoclonal antibody (1 μL in 200 μL of PBS) against EMMPRIN for 1 h in a humidifying chamber followed by washing the slides with wash buffer. A super enhancer was added and incubated for 20 min to promote Ag-Ab reaction followed by washing with PBS. The slides were incubated with poly-HRP for 30 min followed by washing with PBS. The slides were incubated with a freshly prepared substrate/chromogen solution of 3,3 diaminobenzidine in the provided buffer for 10 min to reveal the color of antibody staining. Harris hematoxylin stain was used to counterstain the slides followed by bluing of the slides in tap water for 2 min. The slides were then dehydrated and mounted with distyrene plasticizer xylene.

Evaluation of immunohistochemical expression

The immunohistochemically stained sections with EMMPRIN were evaluated for intensity and area of expression. The intensity of expression was graded as light brown(+), golden brown (++), dark brown(+++) and no expression(-). This expression was noted in the stratum basale, stratum spinosum and stratum corneum of the epithelium and also, in the lamina propria, muscularis mucosa and submucosa of the connective tissue stroma. Each OSCC case was divided into superficial front and invasive front based on the varied pattern of immunoexpression of EMMPRIN was noted at the superficial and invasive front of OSCC.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS v.15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). Chi-squared test and Fischer's exact test were used to analyze the association between the clinical parameters and immunohistochemical results. P <0.05 was considered as statistically significant at 95% of confidence interval.

RESULTS

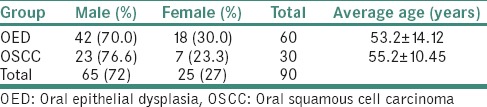

A male predominance was observed in both OED 42 (70%) and OSCC 23 (76.6%) cases. The average age of patients with OED and OSCC were 53.2 ± 14.12 and 55.2 ± 10.45 years, respectively [Table 1]. In OED cases, the buccal mucosa (62%) was most commonly involved followed by the tongue (15%) and lip (10%). In OSCC cases, the buccal mucosa (30%) was the most common site followed by the alveolus (23%) and gingivobuccal sulcus (20%).

Table 1.

Demographic data

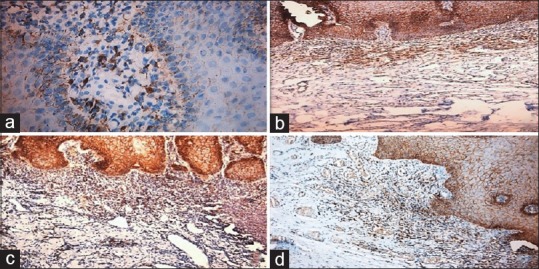

In NOM, a weak light brown immunoexpression of EMMPRIN was observed to be localized in the basal layer of the epithelium in all the cases of NOM (n = 10).

Immunoexpression in oral epithelial dysplasia

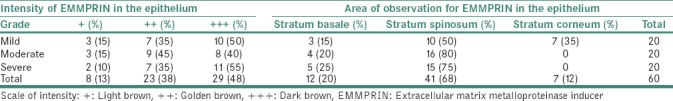

Out of 60 OED cases, 29 (48%) cases showed dark brown staining, 23 (38%) cases showed golden brown staining, and only 8 (13%) cases showed weak brown staining [Table 2]. However, there was no significant association between intensity of immunoexpression of EMMPRIN and different grades of the OED (P = 0.785).

Table 2.

Immunoexpression in epithelium of oral epithelial dysplasia

Immunoexpression in the epithelium

Maximum immunoexpression of EMMPRIN 41 (68%) was observed in the stratum spinosum of the epithelium, whereas the least expression 7 (12%) was observed in the stratum corneum with no negative expressions. A statistically significant association was observed between different grades of OED and the area of immunoexpression of EMMPRIN [P = 0.003; Table 2 and Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Photomicrograph of normal oral mucosa showing weak intensity in basal cells of stratum epithelium (b) mild dysplasia with dark brown intensity in stratum spinosum (c) moderate dysplasia showing intense staining in stratum spinosum and (d) severe dysplasia showing intense staining in stratum spinosum

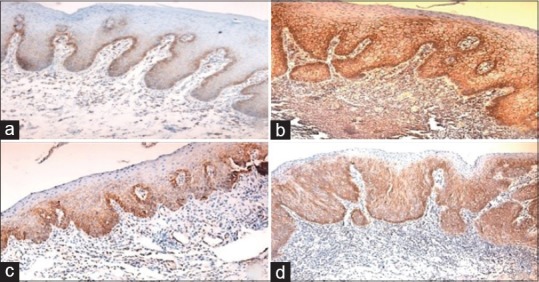

Immunoexpression in the stroma

Out of 60 OED cases, 22 (37%) cases showed no expression. However, (32%) cases showed golden brown staining, followed by 13 (22%) cases with light brown staining, and only 6 (10%) depicting dark brown staining. In contrast, mild dysplasia showed no intense brown staining at all [Table 3]. A statistically significant association was obtained in the connective tissue of the stroma in OED cases (P = 0.02). A predominant expression 25 (42%) was observed in the lamina propria with low expression in 8 (13%) cases in muscularis mucosa, followed by 6 (10%) cases in the submucosa [Table 3 and Figure 2].

Table 3.

Immunoexpression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer in the stroma of oral epithelial dysplasia group

Figure 2.

(a) Photomicrograph of normal oral mucosa showing weak expression in the lamina propria of the stroma (b) mild dysplasia showing golden brown staining in the lamina propria (c) moderate dysplasia showing golden brown staining in the lamina propria and (d) severe dysplasia showing golden brown staining in the lamina propria

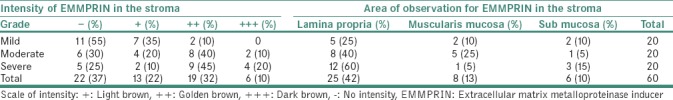

Immunoexpression in oral squamous cell carcinoma

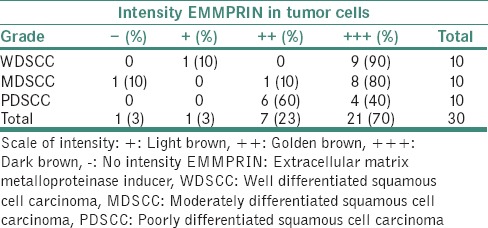

Out of 30 OSCC cases, the majority of the cases showed intense dark brown staining (+++) in the tumor cells. Maximum expression of EMMPRIN with intense dark brown staining was observed in 9 (90%) cases of WDSCC followed by 8 (80%) cases of MDSCC, and 4 (40%) cases of PDSCC. A weak staining was observed only in 1 (10%) case of WDSCC, whereas 1 (10%) case of MDSCC showed no staining at all. A statistically significant association was observed between the intensity of immunoexpression of EMMPRIN and different grades of OSCC [P = 0.02; Table 4].

Table 4.

Intensity of immunoexpression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer in different grades of oral squamous cell carcinoma

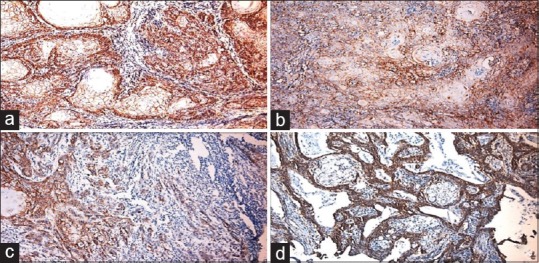

The superficial and invasive fronts were studied in peripheral and central tumor cells based upon the immunoexpression of EMMPRIN. In peripheral tumor, the superficial front exhibited immunoexpression in 11 (37%) cases and invasive front exhibited immunoexpression in 2 (7%) cases. However, in the central placed tumor, superficial front exhibited immunoexpression of EMMPRIN in 2 (7%) cases and invasive front in 3 (10%) cases. When the immunoexpression of the EMMPRIN between NOM, OED, and OSCC was compared, all the cases of NOM showed immunoexpression of EMMPRIN, but with a light brown intensity (+), whereas 28 (47%) cases of OED, and 21 (70%) cases of OSCC showed dark brown staining (+++). The association was found to be statistically significant [P = 0.001; Figure 3].

Figure 3.

(a) Photomicrograph of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma showing intense expression (b) moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma showing intense expression (×10) (c) Poorly differentiate squamous cell carcinoma showing intense expression (d) photomicrograph of intense peripheral staining of cells in superficial front of tumor

DISCUSSION

The study revealed a male predominance in both OED and OSCC cases. A study conducted by Sankaranarayanan obtained similar results in which the female-to-male ratio was 1:2.[8] The occurrence of OED and OSCC in older age-groups suggests a course of the disease when the lesion gets apparent over a period after a long duration of habit. The gender disparity observed in the present study can be explained by the cultural trends followed in the country where men practice the habit of chewing tobacco, whereas most of the women refrain from such habits due to social and traditional stigma.

The buccal mucosa (62%) was predominantly involved in the OED cases, which was similar to the study conducted by Al-Rawi and Talabani who stated that oral cancer affects the tongue, buccal mucosa, alveolus, lower lip and floor of the mouth. However, in the Asian subcontinent, it is commonly observed in the buccal mucosa.[9] The reason for this can be attributed to the prevalent habit of tobacco and quid chewing.[10]

All the cases of NOM revealed weak light brown immunoexpression of EMMPRIN localized in the basal layer of the epithelium in all the cases of NOM (n = 10). This was similar to the study conducted by Gabison et al. who reported an increased immunoexpression of EMMPRIN in the basal cells of the central corneal epithelium of adults.[11]

A statistically significant association was observed between different grades of OED and the area of immunoexpression of EMMPRIN (P = 0.003). This was in concordance to the study conducted by Vigneswaran et al. who determined a minimal immunoexpression in the basal and parabasal layers of the NOM and an increased immunoexpression in OED epithelium with increasing grades of dysplasia. This intense EMMPRIN staining in the present study can be attributed to the early carcinogenic changes in the dysplastic epithelium, which leads to rapid metamorphosis toward carcinoma. The presence of intense staining pattern in all the grades of OED suggests that dysplasia of mild grade with increased immunoexpression of EMMPRIN can induce carcinogenesis.

A significant association was obtained in the connective tissue of the stroma in OED cases (P = 0.02). On the basis of the available literature, this can be the indication of tumor-stroma interactions, which take place between the dysplastic epithelium and adjacent stroma. The primary function of EMMPRIN is the synthesis of multiple MMPs by stimulating host stromal fibroblasts.[12] The other studies have also showed the role of EMMPRIN in the induction of various MMPs released from the tumor surface cells and surrounding stroma, which significantly contribute to the multistep pathogenesis of the tumor.[13]

In the present study, a significant association was observed between the intensity of immunoexpression of EMMPRIN and different grades of OSCC (P = 0.02). The increased immunoexpression in differentiated cells may be due to the modulation of the stroma in the early stages of carcinoma by EMMPRIN leading to the increased production of MMPs in the peritumoral cells. This increased immunoexpression of EMMPRIN in the present study was similar to the study conducted by Huang et al. who related this expression with the proliferative activity of the tumor.[4] However, this was contradictory to the study conducted by Monteiro et al. who observed the overexpression of EMMPRIN in the cases of MDSCC and PDSCC when compared to WDSCC.[14] Majority of the immunoexpression of EMMPRIN in the present study was observed both in the cytoplasm and cell membrane of the cells, which was similar to the observations made by Monteiro et al.[14]

Varied pattern of immunoexpression of EMMPRIN in peripheral and central cells of the tumor was observed when evaluating its expression in superficial and invasive front of the tumor cells. The enhanced immunoexpression localized in the peripheral cells is indicative of a more proliferative potential of the tumor cells.[4,15] However, in the present study, the superficial and invasive front of the tumor did not influence the immunoexpression of the EMMPRIN as the similar immunoexpression was observed in both superficial and invasive front of tumor islands. This was contradictory to the observation made by Vigneswaran et al. who showed the elevated immunoexpression of EMMPRIN in the progressive and metastatic OSCC tumors in their invasive fronts while it was suppressed in the differentiated areas of the tumors.[7]

When the immunoexpression of EMMPRIN was compared between the study groups, a statistically significant association was obtained (P = 0.001). This was in concordance with the literature in which similar intensity was observed in both OED and OSCC cases suggesting the role of EMMPRIN in the progression of malignancy.[7,14,16]

CONCLUSION

The overexpression of EMMPRIN was not only seen in the cases of carcinoma but also in various grades of dysplasia. The role of EMMPRIN in precarcinogenesis and early carcinogenesis needs to be studied on considerable sample size. This can enable oncologists to detect cancer at an early stage, before it progresses to malignancy. Furthermore, the immunoexpression of EMMPRIN in peritumoral fibroblasts and endothelial cells can help in designing targeted drugs to counter-invasion of oral carcinoma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jerjes W, Upile T, Petrie A, Riskalla A, Hamdoon Z, Vourvachis M, et al. Clinicopathological parameters, recurrence, locoregional and distant metastasis in 115 T1-T2 oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumerman H, Freedman P, Kerpel S. Oral epithelial dysplasia and the development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:321–9. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt AN, Mathur R, Farooque A, Verma A, Dwarakanath BS. Cancer biomarkers-current perspectives. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:129–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo H, Li R, Zucker S, Toole BP. EMMPRIN (CD147), an inducer of matrix metalloproteinase synthesis, also binds interstitial collagenase to the tumor cell surface. Cancer Res. 2000;60:888–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Z, Huang H, Li H, Chen W, Pan C. EMMPRIN expression in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:518–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lescaille G, Menashi S, Cavelier-Balloy B, Khayati F, Quemener C, Podgorniak MP, et al. EMMPRIN/CD147 up-regulates urokinase-type plasminogen activator: Implications in oral tumor progression. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vigneswaran N, Beckers S, Waigel S, Mensah J, Wu J, Mo J, et al. Increased EMMPRIN (CD 147) expression during oral carcinogenesis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006;80:147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankaranarayanan R. Oral cancer in India: An epidemiologic and clinical review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:325–30. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Rawi NH, Talabani NG. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: A case series analysis of clinical presentation and histological grading of 1,425 cases from Iraq. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12:15–8. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0184-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathur PT, Dayal P, Pai KM. Correlation of clinical patterns of oral squamous cell carcinoma with age, site, sex and habits. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2011;23:81. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabison EE, Mourah S, Steinfels E, Yan L, Hoang-Xuan T, Watsky MA, et al. Differential expression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (CD147) in normal and ulcerated corneas: Role in epithelio-stromal interactions and matrix metalloproteinase induction. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:209–19. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62245-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan L, Zucker S, Toole BP. Roles of the multifunctional glycoprotein, emmprin (basigin; CD147), in tumour progression. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:199–204. doi: 10.1160/TH04-08-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng HC, Takahashi H, Murai Y, Cui ZG, Nomoto K, Miwa S, et al. Upregulated EMMPRIN/CD147 might contribute to growth and angiogenesis of gastric carcinoma: A good marker for local invasion and prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1371–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteiro LS, Delgado ML, Ricardo S, Garcez F, do Amaral B, Pacheco JJ, et al. EMMPRIN expression in oral squamous cell carcinomas: Correlation with tumor proliferation and patient survival. Biomed Res Int 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/905680. 905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bordador LC, Li X, Toole B, Chen B, Regezi J, Zardi L, et al. Expression of emmprin by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iacono KT, Brown AL, Greene MI, Saouaf SJ. CD147 immunoglobulin superfamily receptor function and role in pathology. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83:283–95. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]