ABSTRACT

The activation of phospholipase C (PLC) is a conserved mechanism of receptor-activated cell signaling at the plasma membrane. PLC hydrolyzes the minor membrane lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2], and continued signaling requires the resynthesis and availability of PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane. PI(4,5)P2 is synthesized by the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P). Thus, a continuous supply of PI4P is essential to support ongoing PLC signaling. While the enzyme PI4KA has been identified as performing this function in cultured mammalian cells, its function in the context of an in vivo physiological model has not been established. In this study, we show that, in Drosophila photoreceptors, PI4KIIIα activity is required to support signaling during G-protein-coupled PLC activation. Depletion of PI4KIIIα results in impaired electrical responses to light, and reduced plasma membrane levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2. Depletion of the conserved proteins Efr3 and TTC7 [also known as StmA and L(2)k14710, respectively, in flies], which assemble PI4KIIIα at the plasma membrane, also results in an impaired light response and reduced plasma membrane PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 levels. Thus, PI4KIIIα activity at the plasma membrane generates PI4P and supports PI(4,5)P2 levels during receptor activated PLC signaling.

KEY WORDS: PI4P, PI4KIIIα, PLC, Drosophila

Highlighted Article: The enzyme PI4KIIIα works with two other proteins to produce PI4P, which feeds into the PIP2 pool at the plasma membrane. This is required for PLC signaling during Drosophila phototransduction.

INTRODUCTION

The hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] by PLC is a conserved mechanism of signaling used by several G-protein-coupled and receptor tyrosine kinases at the plasma membrane (Rhee, 2001). PI(4,5)P2 is primarily enriched at the plasma membrane; in addition to PLC signaling, PI(4,5)P2 supports multiple other functions, including endocytosis and cytoskeletal regulation (Kolay et al., 2016), and is considered to be a determinant of plasma membrane identity. PI(4,5)P2 is generated when PI4P is phosphorylated by the phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIP5K) class of enzymes (reviewed in Kolay et al., 2016). Thus, PI4P availability is essential to support the production and function of PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane. A principal mechanism of PI4P generation is the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol (PI) by phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI4K). Multiple classes of PI4K enzymes that perform this reaction at distinct cellular locations have been described (Balla et al., 2005; Hammond et al., 2014). Evidence in yeast (Audhya and Emr, 2002) and mammalian cells (Balla et al., 2008; Bojjireddy et al., 2015; Nakatsu et al., 2012) implicates PI4KIIIα (known as PI4KA in mammals) in producing a plasma membrane pool of PI4P. Given that PI(4,5)P2 is the substrate for PLC, the activity of PI4KIIIα in generating PI4P is likely important for supporting PLC signaling at the plasma membrane. Previous pharmacological evidence, coupled with RNAi studies, have implicated PI4KIIIα in regulating PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 production at the plasma membrane during PLC signaling (Balla et al., 2008). However, the role of PI4KIIIα in regulating physiology during PLC-mediated PI(4,5)P2 turnover in the physiological context of an in vivo model remains to be established.

In both yeast (Baird et al., 2008) and mammalian cells (Nakatsu et al., 2012), compelling evidence has been presented showing that PI4KIIIα functions as part of a multiprotein complex that includes three conserved core proteins – PI4KIIIα, Efr3 and TTC7 (YPP1 in yeast). Loss of either Efr3B or TTC7B results in a loss of PI4KIIIα recruitment to the plasma membrane and impacts PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 homeostasis. The Efr3-encoding gene is conserved in evolution and a single ortholog is found in metazoan model organisms such as Drosophila. Surprisingly, a previous study (Huang et al., 2004) has reported that Drosophila Efr3 [encoded by stambhA (stmA); also known as rolling blackout (rbo)] encodes a DAG lipase; loss of stmA results in embryonic lethality and viable alleles show temperature-sensitive paralysis (Chandrashekaran and Sarla, 1993) and phototransduction defects (Huang et al., 2004) as adults. Thus, in Drosophila, an alternative function is proposed for Efr3, a core protein component of the PI4KIIIα complex, and its role in regulating PI4P production is not known.

The enzymes that regulate phosphoinositide metabolism are conserved in the Drosophila genome (Balakrishnan et al., 2015). The fly genome has three genes that encode orthologs of PI4K enzymes. Of these, PI4KIIIβ (fwd) has been implicated in regulating Rab11 function and cytokinesis during spermatogenesis (Brill et al., 2000; Polevoy et al., 2009) and PI4KIIβ in secretory granule biogenesis in salivary gland cells (Burgess et al., 2012). PI4KIIIα has been implicated in controlling plasma membrane PI4P and PI(4,5)P2, and appears to function in regulating membrane trafficking and actin dynamics at the plasma membrane (Wei et al., 2008). However, in flies, the requirement for PI4KIIIα in producing PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane to support PLC signaling remains unknown.

Drosophila photoreceptors are a well-established model for the analysis of phosphoinositide signaling (Raghu et al., 2012). In adult photoreceptors, photon absorption triggers high rates of G-protein-activated PLCβ signaling leading to the hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2. The biochemical reactions so triggered lead to the opening of the Ca2+-permeable channels TRP and TRPL, thus generating an electrical response to light. PLCβ activity is essential, since mutants in norpA, which encodes PLCβ, fail to generate an electrical response to light (Bloomquist et al., 1988). Mutants in a number of other genes that encode proteins required for PI(4,5)P2 synthesis have also been isolated, and loss of their activity leads to defective responses to light (reviewed in Raghu et al., 2012). Pertinent to this study, mutations in rdgB, which encodes a phosphatidylinositol transfer protein (reviewed in Trivedi and Padinjat, 2007; Yadav et al., 2015), and dPIP5K (also known as PIP5K59B) an eye-enriched kinase that generates PI(4,5)P2 from PI4P (Chakrabarti et al., 2015), both result in defective electrical responses to light and altered PI(4,5)P2 dynamics at the plasma membrane. However, the enzyme that generates the PI4P from which PI(4,5)P2 is synthesized in photoreceptors remains unknown. In this study, we identify PI4KIIIα as the enzyme that synthesizes PI4P to generate PI(4,5)P2 and support the electrical response to light in Drosophila photoreceptors.

RESULTS

Identification of a PI4K that regulates the light response in Drosophila

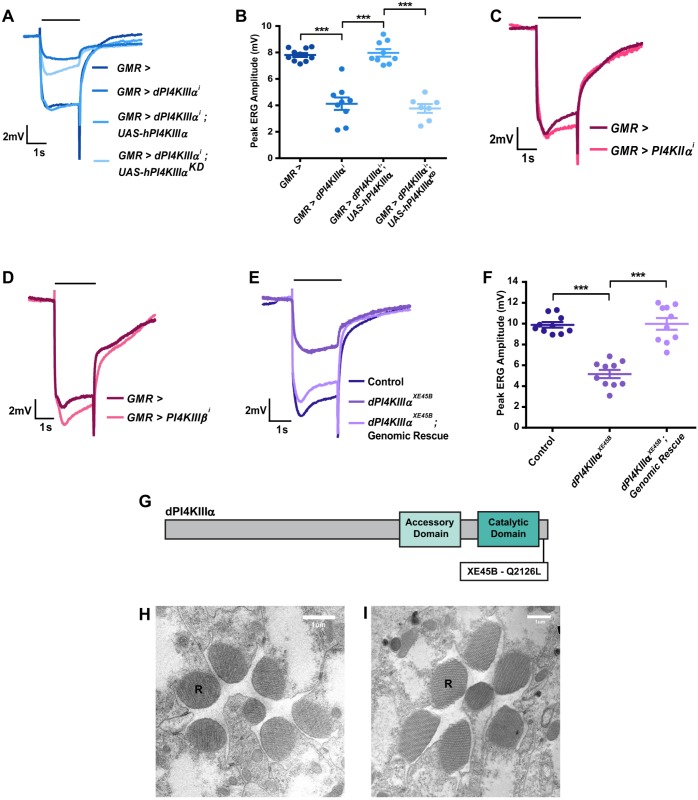

The Drosophila genome has three genes encoding orthologs of mammalian PI4K isoforms (Balakrishnan et al., 2015) – CG2929 (PI4KIIα), CG10260 (PI4KIIIα, also denoted dPI4KIIIα when necessary) and CG7004 (fwd, PI4KIIIβ). To test the effect of depleting these genes on phototransduction, UAS-RNAi lines against each gene were used and expressed using the eye-specific driver GMR-Gal4. The efficiency of each of the RNAi lines used to deplete transcripts for the respective gene was tested by performing quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) of retinal tissue (Fig. S1A–C). To test the effect of depleting each PI4K isoform on the electrical response to light, we recorded electroretinograms (ERG). In response to stimulation with a flash of light, wild-type photoreceptors undergo a large depolarization coupled with on and off transients that are dependent on synaptic transmission (Fig. 1A). When PI4KIIα and PI4KIIIβ were knocked down, the ERG amplitude in response to a single flash of light was comparable to that in controls (Fig. 1C,D), and synaptic transients were also not affected. However, when PI4KIIIα was knocked down (GMR>dPI4KIIIαi), the response amplitude was reduced to approximately half of that seen in controls (Fig. 1A,B); as expected of low-amplitude light responses, transients were also not detected (Fig. 1A). Q-PCR analysis of retinal tissue from GMR>dPI4KIIIαi showed that transcripts for the two other PI4K isoforms, PI4KIIα and PI4KIIIβ were not depleted (Fig. S1D,E). The waveform and reduced ERG amplitude in GMR>dPI4KIIIαi could be fully rescued by reconstituting retinae with a human PI4KIIIα transgene (GMR>dPI4KIIIαi; UAS-hPI4KIIIα) but not by a kinase dead transgene (GMR>dPI4KIIIαi; UAS-hPI4KIIIαKD) (Fig. 1A,B). These findings demonstrate that PI4KIIIα activity is required to support a normal electrical response to light in Drosophila photoreceptors.

Fig. 1.

PI4KIIIα is required for normal PLC signaling in photoreceptors. (A) Representative ERG trace of 1-day-old flies of the indicated genotype. The x-axis presents time (s); the y-axis is amplitude in mV. The black bar above traces indicates the duration of the light stimulus. The experiment was repeated three times, and one of the trials is shown here. (B) Quantification of the ERG response, where peak ERG amplitude was measured from 1-day-old flies. The x-axis indicates genotype; the y-axis indicates peak amplitude in mV. The mean±s.e.m. is indicated, n=10 flies per genotype. ***P<0.001 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). (C–E) Representative ERG trace of 1-day-old flies with genotypes as indicated. The x-axis presents time (s); the y-axis is amplitude in mV. The black bar above traces indicates the duration of the light stimulus. The experiment has been repeated three times, and one of the trials is shown here. (F) Quantification of the ERG response, where peak ERG amplitude was measured from 1-day-old flies. The x-axis indicates genotype; the y-axis indicates peak amplitude in mV. The mean±s.e.m. is indicated, n=10 flies per genotype. ***P<0.001 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). (G) Schematic representation of the dPI4KIIIαXE45B point mutation. The location of the Q2126L mutation is indicated. (H,I) Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) showing sections of photoreceptors from 1-day-old control and dPI4KIIIαXE45B mutant flies, respectively. R, rhabdomere.

Mutants in PI4KIIIα recapitulate the effect of RNAi knockdown

Loss-of-function mutants for PI4KIIIα are homozygous cell lethal (Yan et al., 2011); this is also the case in the eye, precluding an analysis of complete loss of PI4KIIIα function on the light response. To further validate the ERG phenotype observed in GMR>dPI4KIIIαi, a hypomorphic point mutant allele of PI4KIIIα, dPI4KIIIαXE45B (Fig. 1G) was analyzed. dPI4KIIIαXE45B was isolated in a forward genetic screen for ERG defects (Yamamoto et al., 2014); we mapped a point mutation to Q2126L in this allele (Fig. 1G). Since mutants of dPI4KIIIαXE45B are homozygous lethal as adults, whole-eye mosaics (Stowers and Schwarz, 1999) in which only retinal tissue is homozygous mutant but the rest of the animal is heterozygous were generated and studied. In ERG recordings, the amplitude of the light response in newly eclosed dPI4KIIIαXE45B flies was reduced as compared to controls (Fig. 1E,F). Importantly, this reduced ERG amplitude was seen although the ultrastructure of the photoreceptors was unaffected (Fig. 1H,I). The effect of dPI4KIIIαXE45B on the ERG response was rescued by reconstitution of gene function using a genomic PI4KIIIα construct (Fig. 1E,F). This clearly indicates that the reduced ERG response was a direct effect of the mutation, reiterating a requirement for PI4KIIIα in supporting a normal ERG response in Drosophila.

Depletion of PI4KIIIα reduces PIP and PIP2 levels in photoreceptors

One of the functions of PI4P is to act as substrate for the synthesis of PI(4,5)P2 by PIP5K enzymes. To test whether the reduced ERG amplitude seen upon PI4KIIIα depletion is due to the reduced levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2, we used mass spectrometric methods to measure the levels of these lipids in the retina. To do this, we adapted a recently developed method that allows the chemical derivatization and subsequent measurement of phosphoinositides (Clark et al., 2011). This method allows the identification of molecules on the basis of their mass; thus phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylinositol monophosphates (PIP) and phosphatidylinositol bisphosphates (PIP2) can be identified on the basis of their characteristic m/z. Positional isomers of PIP [PI4P, PI3P and PI5P] and PIP2 [PI(4,5)P2, PI(3,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2], all of which have an identical m/z cannot be distinguished by the mass spectrometer and methods to separate them by liquid chromatography remain to be established. However, it is well established that PI4P represents ∼90% of the PIP pool and PI(4,5)P2 that of the PIP2 pool (Lemmon, 2008). Thus, any measurement of PIP and PIP2 will be dominated by PI4P and PI(4,5)P2, respectively. The full details and validation of the methods are given in Fig. S2 and Materials and Methods.

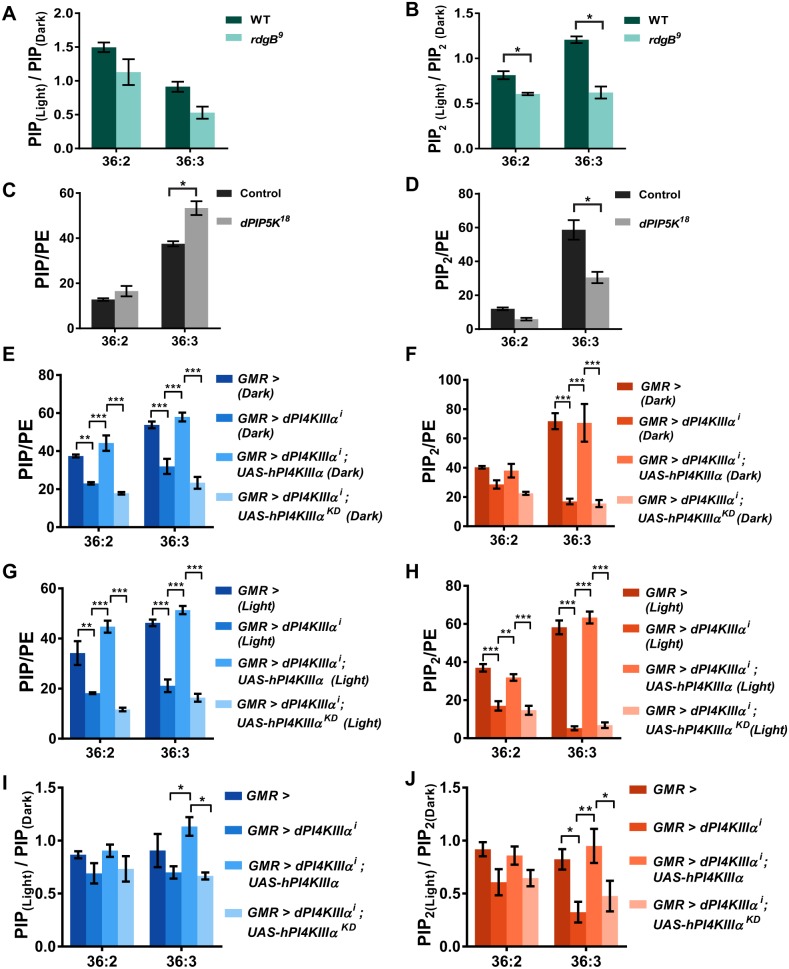

Through this method, we determined the levels of PIP and PIP2 in retinal samples. As a positive control, we studied the levels of PI, PIP and PIP2 in retinae from rdgB mutants; rdgB encodes an eye-enriched phosphatidylinositol transfer protein (Trivedi and Padinjat, 2007) that is required to support PI(4,5)P2 resynthesis during phototransduction (Hardie et al., 2001, 2015; Yadav et al., 2015, 2018). Using our assay, we found that the levels of 36:2 and 36:3 species of PIP and PIP2, which were the most abundant species in retinal tissue (Fig. S2F), were lower in rdgB9 than in controls (Fig. S3A–D). Importantly, the levels of these two species of PIP and PIP2 were further reduced following a bright flash of light such that the ratio of the levels of PIP [PIP(light):PIP(dark)] and PIP2 [PIP2(light):PIP2(dark)] were reduced to a greater extent in rdgB9 mutants than in wild-type (Fig. 2A,B). We also measured the levels of PIP and PIP2 from retinae of a loss-of-function mutant for PIP5K (dPIP5K18), which we have previously shown to be essential to support a normal electrical response and light-induced PI(4,5)P2 dynamics in photoreceptors (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). In dPIP5K18 retinae from dark-reared flies, as might be expected from loss of PIP5K activity, we found that the levels of PIP were elevated (Fig. 2C) and the levels of PIP2 (Fig. 2D) were lower than those in controls.

Fig. 2.

PI4KIIIα supports PIP and PIP2 levels during phototransduction. (A,B) Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) measurement of total PIP and PIP2 levels, respectively, from retinae of 1-day-old rdgB9 mutant flies. To highlight the effect of illumination on lipid levels, flies were reared in dark and subjected to two treatments – one processed completely in dark (dark) and the other exposed to 1 min of bright illumination before processing (light). The y-axis represents a ratio of lipid levels PIP(light):PIP(dark) and PIP2(light):PIP2(dark),under these two conditions from wild-type (WT) and rdgB9 retinae. Ratios for the two most abundant molecular species of PIP and PIP2 (36:2 and 36:3) are shown. A reduction in the ratio indicates a drop in the levels of PIP and PIP2 during illumination. Values are mean±s.e.m., n=25 retinae per sample *P<0.05 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). The experiment was repeated three times, and one of the trials is shown here. (C,D) LC-MS measurement of total PIP and PIP2 levels, respectively, from retinae of 1-day-old dPIP5K18 mutant flies. Flies were reared and processed completely in the dark. Levels for the two most abundant molecular species of PIP and PIP2 (36:2 and 36:3) are shown. The y-axis represents PIP and PIP2 levels normalized to those of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Values are mean±s.e.m., n=25 retinae per sample. *P<0.05 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). The experiment has been repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. (E,F) LC-MS measurement of total PIP and PIP2 levels, respectively, from retinae of 1-day-old flies with genotypes as indicated. Flies were reared and processed completely in the dark. Levels for the two most abundant molecular species of PIP and PIP2 (36:2 and 36:3) are shown. The y-axis represents PIP and PIP2 levels normalized to PE. Values are mean±s.e.m., n=25 retinae per sample. ***P<0.001 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). The experiment has been repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. (G,H) LC-MS measurement of total PIP and PIP2 levels, respectively, from retinae of 1-day-old flies with genotypes as indicated. Flies were reared in dark and exposed to one minute of bright illumination before processing. The y-axis represents PIP and PIP2 levels normalized to PE. Levels for the two most abundant molecular species of PIP and PIP2 (36:2 and 36:3) are shown. Values are mean±s.e.m., n=25 retinae per sample. ***P<0.001 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). The experiment has been repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. (I,J) LC-MS measurement of total PIP and PIP2 levels, respectively, from retinae of 1-day-old flies with genotypes as indicated. The y-axis represents a ratio of lipid levels PIP(light):PIP(dark) and PIP2(light):PIP2(dark). Ratios for the two most abundant molecular species of PIP and PIP2 (36:2 and 36:3) are shown. A reduction in the ratio indicates a drop in the levels of PIP and PIP2. Values are mean±s.e.m., n=25 retinae per sample. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test).

We then studied the levels of PIP and PIP2 in retinae depleted of PI4KIIIα. We found that under basal conditions (minimal light exposure) the levels of both PIP (Fig. 2E) and PIP2 (Fig. 2F) were lower in GMR>dPI4KIIIαi than in controls and were further reduced in retinae subjected to bright light illumination (Fig. 2G,H). PIP and PIP2 levels could be rescued by reconstitution with a wild-type hPI4KIIIα transgene, but not by a kinase-dead version of the same (Fig. 2E–H). Importantly, the levels of PIP and PIP2 were further reduced following a bright flash of light such that the ratio of the levels of PIP [PIP(light):PIP(dark)] and PIP2 [PIP2(light):PIP2(dark)] were lowered to a greater extent in GMR>dPI4KIIIαi than in wild-type (Fig. 2I,J). This phenotype could be rescued by a wild-type hPI4KIIIα transgene, but not by the kinase-dead version of the enzyme. These findings strongly suggest that dPI4KIIIα activity is required to support PIP and PIP2 levels during phototransduction.

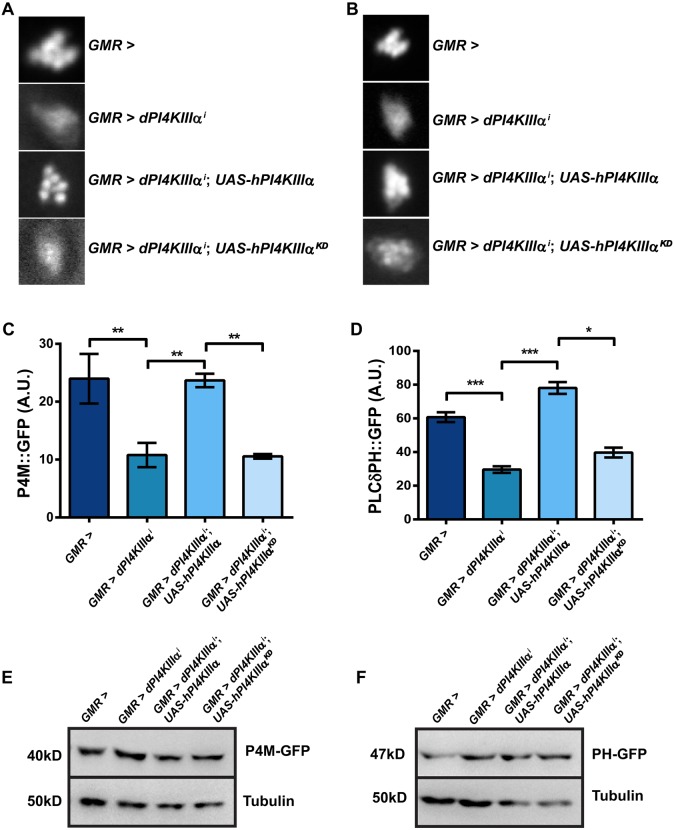

Depletion of PI4KIIIα reduces PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 levels at the plasma membrane

Eukaryotic cells contain multiple organellar pools of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2, including a plasma membrane fraction which in yeast is supported by the PI4KIIIα ortholog, stt4 (Audhya and Emr, 2002). We tested whether depletion of PI4KIIIα supports the plasma membrane pool of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 in photoreceptors. In photoreceptors, the apical plasma membrane is expanded as a folded microvillar structure packed together to form the rhabdomere, which acts as a light guide. The rhabdomere can be visualized in intact eyes as the deep pseudopupil; fluorescent proteins fused to specific lipid-binding domains can be visualized in intact flies, thus reporting plasma membrane levels of the lipids that they bind (Chakrabarti et al., 2015; Várnai and Balla, 1998). We generated transgenic flies that allow the expression of fluorescent reporters specific for PI4P and PI(4,5)P2. For PI4P, we used the bacterial derived P4M domain (Hammond et al., 2014), and for PI(4,5)P2 we used the PH domain of PLCδ. These reporters were expressed in control and GMR>dPI4KIIIαi photoreceptors, and the fluorescence in the deep pseudopupil was visualized and quantified to estimate levels of the respective lipid at the rhabdomeral plasma membrane. In GMR>dPI4KIIIαi, the levels of rhabdomeral PI4P (Fig. 3A,C) and PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 3B,D) were reduced, although the total level of reporter protein was not altered (Fig. 3E,F). These findings strongly suggest that PI4KIIIα activity is required to support plasma membrane levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 in photoreceptors.

Fig. 3.

PI4KIIIα is required for normal levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane. (A) Representative images of the fluorescent deep pseudopupil from 1-day-old flies expressing the P4M::GFP probe with genotype as indicated. (B) Representative images of the fluorescent deep pseudopupil from flies expressing the PLCδPH::GFP probe with genotype as indicated. The experiments in A and B were repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. (C,D) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of the deep pseudopupil. Fluorescence intensity per unit area is shown on the y-axis (A.U., arbitrary units); the x-axis indicates the genotype. Values are mean±s.e.m. n=10 flies per genotype. *P<0.05 (two-tailed unpaired t-test). (E,F) Western blot of head extracts made from flies expressing the P4M::GFP and PLCδPH::GFP probes, respectively. The levels of tubulin are used as a loading control; genotypes are indicated above.

Downregulation of Efr3 and TTC7 phenocopies depletion of PI4KIIIα

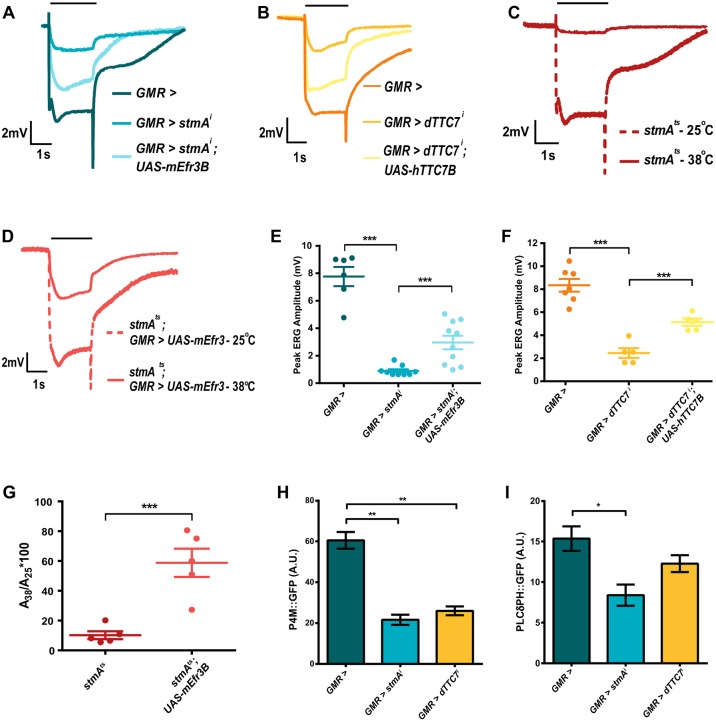

In both yeast (Baird et al., 2008) and mammalian cells (Baskin et al., 2016; Nakatsu et al., 2012), PI4KIIIα is known to localize at the plasma membrane in conjunction with two additional proteins – Efr3 and Ypp1/TTC7. It has also been shown in yeast that when Efr3 was prevented from residing in the plasma membrane, there was a slight but significant drop in total cellular PI4P levels (Wu et al., 2014). We tested the requirement for these two proteins in regulating phototransduction and PI4P levels in Drosophila. The Drosophila genome encodes a single ortholog of each protein – denoted as CG8739, known as rbo or stmA (Efr3), and CG8325 or l(2)k14710 (TTC7); rbo has previously been reported to be a DAG lipase (Huang et al., 2004). If stmA is indeed vital for PI4KIIIα activity at the plasma membrane, then reducing its levels ought to have a similar effect to reducing PI4KIIIα levels. Since complete loss-of-function mutations for stmA are cell lethal (Chandrashekaran and Sarla, 1993; Huang et al., 2004), transgenic RNAi was used to reduce gene function (GMR>stmAi) and Q-PCR analysis showed a substantial reduction in stmA transcripts (Fig. S4A). We found that GMR>stmAi flies showed a low ERG amplitude, similar to that of dPI4KIIIαi flies (Fig. 4A,E). This reduction in ERG amplitude could be partially rescued by reconstitution of GMR>stmAi with mouse Efr3B (mEfr3B) (Fig. 4A,E).

Fig. 4.

Depletion of EFR3 and TTC7 phenocopy the effect of PI4KIIIα depletion in photoreceptors. (A–D) Representative ERG trace of 1-day-old flies with genotype as indicated. The x-axis shows time (s); the y-axis is amplitude in mV. The black bar above traces indicates the duration of the light stimulus. The experiment has been repeated three times, and one of the trials is shown here. (E,F) Quantification of the ERG response, where peak ERG amplitude was measured from 1-day-old flies. The x-axis indicates the genotype; the y-axis indicates peak amplitude in mV. The mean±s.e.m. is indicated, n=10 flies (E) and 5 flies (F) per genotype. ***P<0.001 (two-tailed unpaired t-test). (G) Quantification of the ERG response, where ratio of peak amplitudes at restrictive (38°C) and permissive (25°C) temperatures were taken. The x-axis indicates the genotype; the y-axis indicates ratio of peak amplitudes. The mean±s.e.m. is indicated, n=5 flies per genotype. ***P<0.001 (two-tailed unpaired t-test). (H,I) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of the deep pseudopupil. The fluorescence intensity per unit area is shown on the y-axis; the x-axis indicates genotype. Values are mean±s.e.m., n=10 flies per genotype. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (two-tailed unpaired t-test). The experiment has been repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here.

Since the GMR-Gal4 that was used to express stmAi is expressed throughout eye development, it is formally possible that the reduced ERG amplitude we observed was a consequence of a developmental defect. To resolve this, we used temperature-sensitive mutant alleles where the protein is inactivated post-development by raising the temperature of the animal to the restrictive temperature. We studied the ERG phenotype of stmAts at the permissive temperature of 25°C in comparison with the phenotype at the restrictive temperature of 38°C (Chandrashekaran and Sarla, 1993). As a positive control, a well-characterized temperature-sensitive allele of PLC (norpAH52) was used (Wilson and Ostroy, 1987). Like wild-type flies, norpAH52 flies showed a normal ERG response at 25°C but showed no response at 38°C, whereas control flies were largely unaffected by the change in temperature (Fig. S4E–G). At 25°C, stmAts flies showed normal ERG amplitudes but were almost nonresponsive at 38°C (Fig. 4C). When reconstituted with the mammalian Efr3 construct, the reduced ERG amplitude of stmAts at 38°C was partially rescued (Fig. 4D,G). Likewise, when TTC7 was depleted by RNAi, the reduction in ERG amplitude mirrored that seen when PI4KIIIα was depleted (Fig. 4B,F; Fig. S4B) and this could be partially rescued by reconstituting with the human TTC7B protein (hTTC7B) (Fig. 4B,F). Finally, when either stmA or TTC7 were depleted by RNAi, we found that the levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane as measured by assessing fluorescence of the deep pseudopupil were reduced (Fig. 4H,I; Fig. S4C,D); this recapitulates the reduction in PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 levels at the rhabdomere seen when PI4KIIIα is depleted. Mass spectrometry analysis of retinae where stmA was depleted showed that the levels of PIP and PIP2 were reduced and this reduction was further enhanced during illumination (Fig. S4H–M).

Normal levels of key phototransduction proteins in PI4KIIIα-depleted retinae

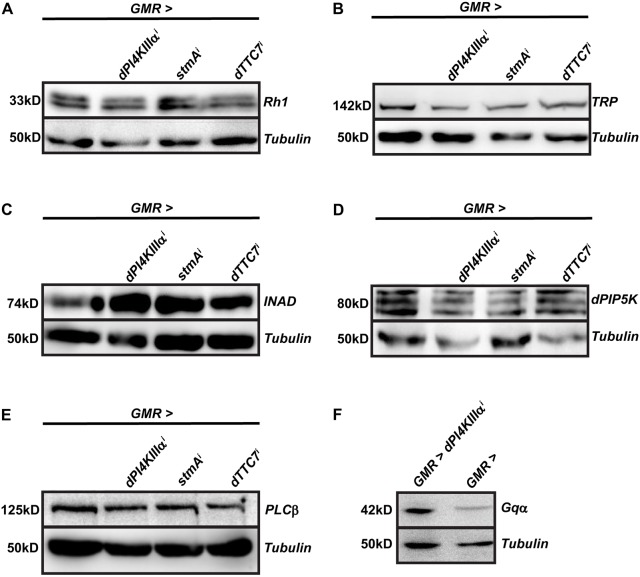

The molecular basis for the reduced ERG response in PI4KIIIα-depleted flies could be due to multiple factors. Phototransduction is an event that involves a number of key proteins, each with its own specific function. Loss of function mutants for rhodopsin, PLC and Gqα are known to have a reduced ERG amplitude, whereas mutants for proteins like TRP have other ERG waveform defects (Hardie et al., 2001; Raghu et al., 2012). In order to ascertain whether any of these proteins were affected by the knockdown of PI4KIIIα, Efr3 or TTC7, we performed western blots to check the levels of some key phototransduction proteins.

The levels of Rh1, TRP, NORPA (PLCβ), INAD and PIP5K in all of the GMR>dPI4KIIIαi, stmAi and dTTC7i flies were found to be comparable to those in controls (Fig. 5A–E). Intriguingly, the levels of Gqα were reduced in GMR>stmAi flies, whereas Gqα levels in GMR>dPI4KIIIαi and GMR>TTC7i flies were no different from controls (Fig. 5F; Fig. S3E,F). To check whether the reduction in Gqα levels was due to reduced protein synthesis, we measured the mRNA levels of Gqα in GMR>dPI4KIIIαi, stmAi and dTTC7i fly retinae using Q-PCR. The transcript levels of Gqα were comparable to controls in all three knockdown flies (Fig. S3G), indicating that the reduction in protein levels was not due to reduced transcription.

Fig. 5.

Normal levels of key phototransduction proteins in PI4KIIIα-depleted flies. (A–F) Western blot of head extracts made from flies of the indicated genotypes. For D, protein extracts were made from retinal tissue. Tubulin is used as a loading control with genotypes indicated above. The experiment was repeated three times, and one of the trials is shown here.

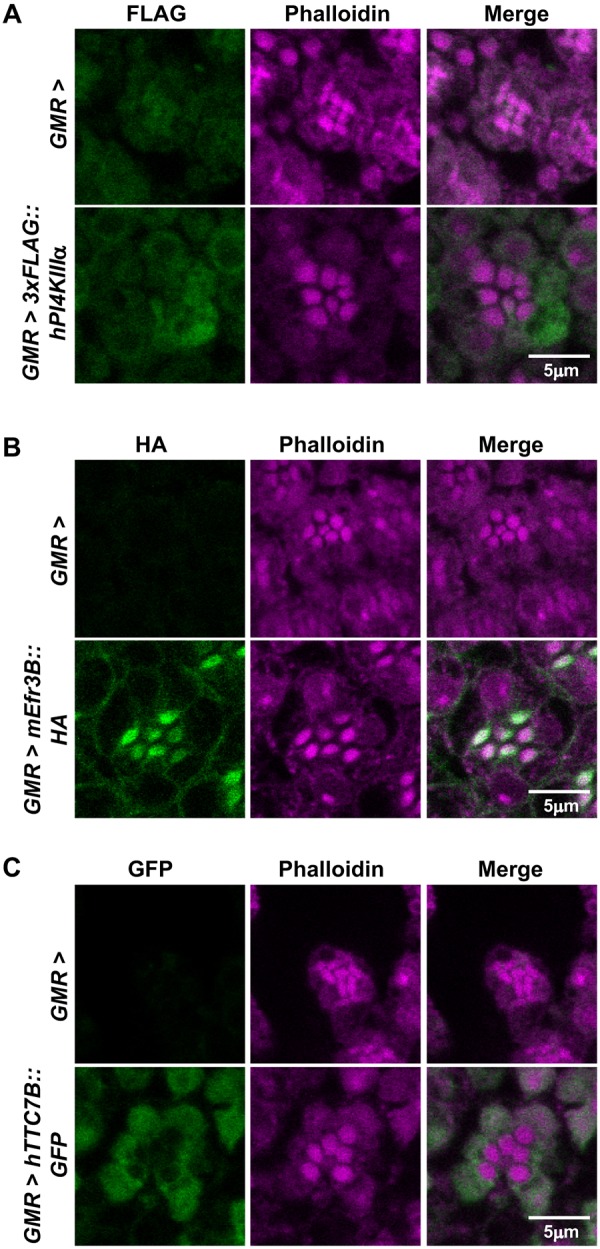

Localization of mammalian PI4KIIIα, Efr3 and TTC7 in Drosophila photoreceptors

In mammalian systems, the architecture of the PI4KIIIα complex is such that the Efr3 protein resides at the plasma membrane, whereas PI4KIIIα and TTC7 translocate to the plasma membrane from the cytosol upon stimulation. Since the mammalian proteins can partially (mEfr3B and hTTC7B) or completely (hPI4KIIIα) rescue the reduced ERG (Nakatsu et al., 2012), phenotypes of GMR>dPI4KIIIαi, stmAi and dTTC7i flies, we tested the subcellular localization of these tagged proteins in Drosophila photoreceptors. We expressed FLAG-tagged hPI4KIIIα in otherwise wild-type flies, which were reared in dark and dissected under a low level of red light to prevent any light stimulation. Antibody staining for FLAG revealed that hPI4KIIIα is excluded from the rhabdomere and present in the cell body of photoreceptors (Fig. 6A). This correlates well with reported data from mammalian cells, where overexpressed PI4KIIIα in the absence of Efr3 and TTC7 remains in the cytosol and does not go to the plasma membrane (Nakatsu et al., 2012).

Fig. 6.

Localization of mammalian PI4KIIIα, Efr3 and TTC7 in photoreceptors. (A) Confocal images of retinae stained with phalloidin and anti-FLAG antibody from GMR> and GMR>3xFLAG::hPI4KIIIα flies. Magenta represents phalloidin, which marks the rhabdomere, and green represents FLAG. The experiment has been repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. (B) Confocal images of retinae stained with phalloidin and anti-HA antibody from GMR> and GMR>mEfr3B::HA flies. Magenta represents phalloidin, which marks the rhabdomere, and green represents HA. The experiment has been repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. (C) Confocal images of retinae stained with phalloidin and anti-GFP antibody from GMR> and GMR>hTTC7B::GFP flies. Magenta represents phalloidin, which marks the rhabdomere, and green represents GFP. The experiment was repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. Scale bars: 5 µm.

Similar experiments were conducted using the mouse Efr3B transgene, where the HA-tagged protein was expressed in Drosophila photoreceptors. Antibody staining for HA revealed that mEfr3B localizes to both the apical rhabdomeral and basolateral plasma membrane of photoreceptors (Fig. 6B). This is consistent with existing data from mammalian systems, where mEfr3B is a plasma membrane-resident protein. When GFP-tagged hTTC7B was expressed in wild-type photoreceptors, it was not observed at the rhabdomere but was diffusely distributed in the cell body, once again in keeping with observations in mammalian cells (Fig. 6C).

We also performed experiments in Drosophila S2R+ cells in culture. These cells were individually transfected with plasmids expressing the tagged mammalian proteins. Western blot analysis using antibodies to the tag used revealed a band of the expected size (Fig. S5A–C). Antibody staining showed that in S2R+ cells, the subcellular localization of these proteins was similar to that seen in photoreceptors, that is, mEfr3B was present at the plasma membrane, whereas hPI4KIIIα and hTTC7B were present in the cell body (Fig. S5).

Interaction of PI4KIIIα with other components of the photoreceptor PI(4,5)P2 cycle

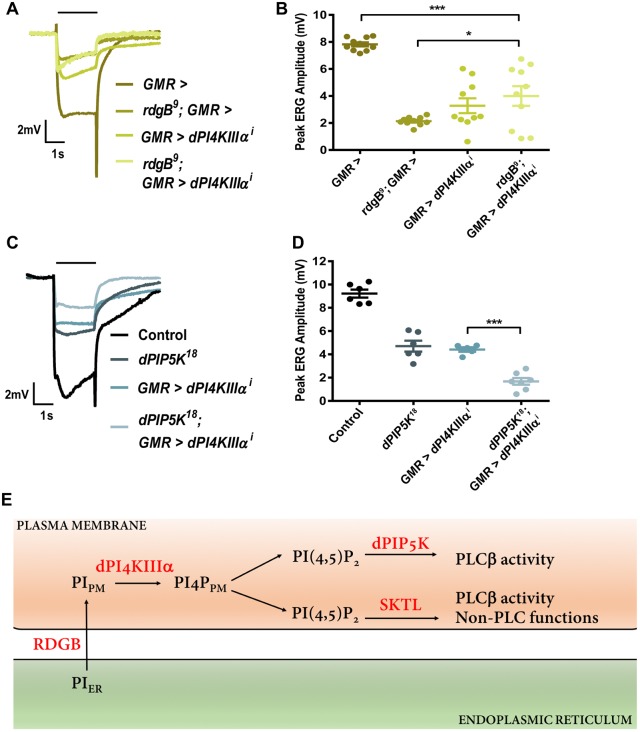

To test the function of PI4KIIIα in the photoreceptor PI(4,5)P2 cycle, we depleted this gene in cells wherein other components of the PI(4,5)P2 resynthesis pathway were also depleted. The lipid transfer protein encoded by rdgB is thought to transfer PI from the SMC to the plasma membrane (Cockcroft et al., 2016; Yadav et al., 2015), where it serves as substrate for PI4KIIIα to generate PI4P. We depleted PI4KIIIα (GMR>dPI4KIIIαi) in the background of the rdgB9 mutant, a hypomorphic allele of rdgB. As previously reported, rdgB9 has a reduced ERG amplitude in response to a flash of light; depletion of dPI4KIIIα in this background results in a marginal change of the reduced ERG amplitude of rdgB9 (Fig. 7A,B); surprisingly this was a partial rescue of the reduced ERG amplitude of rdgB9.

Fig. 7.

Interaction of PI4KIIIα with other components of the PI(4,5)P2 resynthesis pathway. (A) Representative ERG trace of 1-day-old flies with genotype as indicated. The x-axis is time (s); the y-axis is amplitude in mV. The black bar above traces indicates the duration of the light stimulus. The experiment was repeated two times, and one of the trials is shown here. (B) Quantification of the ERG response, where peak ERG amplitude was measured from 1-day-old flies. The x-axis is time (s); the y-axis is amplitude in mV. The mean±s.e.m. is indicated, n=10 flies per genotype. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). (C) Representative ERG trace of 1-day-old flies with genotype as indicated. The x-axis is time (s); the y-axis is amplitude in mV. The black bar above traces indicates the duration of the light stimulus. (D) Quantification of the ERG response, where peak ERG amplitude was measured from 1-day-old flies. The x-axis is time (s); the y-axis is amplitude in mV. The mean±s.e.m. is indicated, n=5 flies per genotype. ***P<0.001 (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test). (E) Model of the biochemical reactions involved in the resynthesis of PI(4,5)P2 in Drosophila photoreceptors. Protein and lipid components are depicted according to the compartment in which they are distributed; the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum are shown. PIER indicates PI in the endoplasmic reticulum, and PIPM indicates PI at the plasma membrane. PI4PPM indicates the plasma membrane pool of PI4P generated by PI4KIIIα. The reactions catalyzed by PI4KIIIα, SKTL and PIP5K at the plasma membrane are indicated. PLCβ activity and non-PLC functions are indicated against the pools of PI(4,5)P2 that support these functions.

We have previously reported a loss-of-function mutant in a PIP5K that converts PI4P into PI(4,5)P2 (dPIP5K18), which results in a reduced ERG amplitude and adversely impacts PI(4,5)P2 levels during phototransduction (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). Partial depletion of PI4KIIIα (GMR>dPI4KIIIαi) or PIP5K loss-of-function (dPIP5K18) both result in an equivalent reduction in ERG amplitude (Fig. 7C,D). However, depletion of PI4KIIIα in dPIP5K18 flies resulted in a further reduction in the ERG amplitude compared to either genotype alone (Fig. 7C,D).

DISCUSSION

During receptor-activated PLC signaling at the plasma membrane, PI(4,5)P2 which is a low-abundance lipid is consumed at high rates. For example, in Drosophila photoreceptors, where photon absorption by rhodopsin activates G-protein-coupled PLC activity, ∼106 PLC molecules are activated every second. In this scenario, plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 would be depleted in the absence of effective mechanisms to enhance its synthesis to match consumption by ongoing PLC signaling. Since plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 in photoreceptors is mainly generated by the phosphorylation of PI4P by PIP5K enzymes, maintenance of PI(4,5)P2 levels during PLC signaling will require the activity of a PI4K to supply PI4P, the substrate for this reaction. In this study, we identify PI4KIIIα as the PI4K isoform required to support a normal electrical response to light in Drosophila photoreceptors. We found that depletion of PI4KIIIα (but not PI4KIIIβ and PI4KIIα) in photoreceptors results in a reduced ERG amplitude during light-activated PLC signaling. This reduced ERG amplitude could be rescued by reconstitution with the human ortholog of PI4KIIIα but not its kinase dead transgene. We also found, by performing mass spectrometry, that in retinae depleted of PI4KIIIα, the levels of PIP were lower than in controls and these were further reduced upon bright light illumination. By undertaking in vivo imaging of the photoreceptor plasma membrane at which PLC is activated, we found that the levels of PI4P were lower, but not completely absent from, this membrane in PI4KIIIα-depleted retinae. What is the source of the residual PI4P in PI4KIIIα-depleted retinae? Importantly, we found that depletion of PI4KIIIα did not result in the upregulation of the other two isoforms of PI4K expressed in Drosophila photoreceptors (PI4KIIIβ and PI4KIIα). The residual PI4P detected at the plasma membrane of PI4KIIIα-depleted retinae likely results from the incomplete removal of this protein in our experiments. Although we could not demonstrate the localization of dPI4KIIIα to the rhabdomere plasma membrane, we found that mEfr3B when expressed in photoreceptors, did localize to the plasma membrane. This observation recapitulates that reported in mammalian cells (Nakatsu et al., 2012) where PI4KIIIα is reported to localize to the plasma membrane only transiently while Efr3 is present constitutively at the plasma membrane. Finally, we found that the reduced ERG amplitude of rdgB9, thought to supply PI for the resynthesis of PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane was marginally but consistently rescued by depletion of PI4KIIIα. Interestingly, it has been previously reported that loss of PIP5K, an enzyme that consumes PI4P to generate PI (4,5)P2 results in an enhancement of rdgB9 (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). While reductions in the function of both PI4KIIIα and PIP5K result in reduced levels of plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2, they have opposite effects on the levels of PI4P; depletion of PI4KIIIα results in reduced PI4P levels while depletion of PIP5K results in elevated PI4P. Thus, the contrasting effect of depleting PI4KIIIα and PIP5K in rdgB9 photoreceptors may be a consequence of their effects on PI4P levels rather than alterations in PI(4,5)P2 levels that occur when either of these enzymes is depleted. Collectively, these findings support the conclusion that PI4KIIIα activity is required to support PI4P levels at the plasma membrane during G-protein-coupled PLC signaling in Drosophila photoreceptors.

In addition to PI4P, depletion of PI4KIIIα also reduced the levels of plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 levels in photoreceptors. In Drosophila photoreceptors, we have previously reported that PIP5K is required for a normal response to light and contributes to PI(4,5)P2 resynthesis during light activated PLC signaling (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). During this study, we found, through a mass spectrometry analysis, that the levels of PIP were elevated in a protein-null mutant of PIP5K (see Fig. 2C). This finding supports the role of PIP5K in regulating the conversion of PI4P into PI(4,5)P2 in these cells. Together with our observations on the requirement of PI4KIIIα in regulating plasma membrane PI4P levels, these results suggest a model where the single enzymatic isoform PI4KIIIα generates a pool of PI4P that is utilized by PIP5K to generate PI(4,5)P2 during PLC signaling.

Although dPIP5K18 is a protein null mutant, it retains a residual response to light and its photoreceptors are not completely depleted of PI(4,5)P2 (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). The synthesis of this remaining PI(4,5)P2 and the substrate for PLC signaling that mediates the residual light response likely comes from the only other PIP5K, which is encoded by sktl and is also expressed in adult photoreceptors. To date, it has not been possible to fully deplete sktl function in photoreceptors without also causing a block in eye development and cell lethality. Thus, the role of sktl in utilizing PI4P generated by PI4KIIIα to generate PI(4,5)P2 for phototransduction remains to be tested. However, it is likely that, in photoreceptors, the single PI4KIIIα produces a plasma membrane pool of PI4P that is used by both PIP5K and SKTL to generate PI(4,5)P2. While the pool generated by PIP5K seems to be used selectively to support PLC signaling, as previously proposed, the pool generated by SKTL likely contributes to both PLC signaling as well as other non-PLC dependent functions in photoreceptors (Fig. 7E; Chakrabarti et al., 2015; Kolay et al., 2016).

During this study, we found that depletion of either Efr3 or TTC7 phenocopied both the reduced ERG amplitude as well as the reduced PI(4,5)P2 levels seen on depletion of PI4KIIIα. Our observation likely reflects the existence, in Drosophila, of the protein complex reported in yeast and mammalian cells (between PI4KIIIα, EFR3 and TTC7), which is necessary for the recruitment and activity of PI4KIIIα at the plasma membrane. Although reductions of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 levels have been reported in mutants of yeast Efr3 (Baird et al., 2008), this has not been well studied in metazoan cells. We found that depletion of Efr3 reduced levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 in Drosophila photoreceptors. Surprisingly, Drosophila EFR3 (rbo/stmA) has been previously reported as a DAG lipase that regulates phototransduction (Huang et al., 2004). It is unclear whether there is any link between the reported DAG lipase activity of stmA and the regulation of the PI(4,5)P2 cycle. While our study cannot rule out a DAG lipase function for stmA, our data clearly indicates that, in Drosophila, this gene, like its yeast and mammalian orthologs, is required to support PI4KIIIα activity. Moreover, the mouse Efr3B, when expressed in Drosophila photoreceptors, localizes to both the rhabdomeric and basolateral membranes. Thus, the core complex of PI4KIIIα, EFR3 and TTC7 is likely to be an evolutionarily conserved regulator of PI4KIIIα function. In addition, mammalian cells contain other regulators such as TMEM150A (Chung et al., 2015) and FAM126A (Baskin et al., 2016) that have been proposed as alternative adaptors to TTC7; these have not been identified in yeast or invertebrate systems. In summary, our work defines the function of PI4KIIIα in the regulation of plasma membrane PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 synthesis during receptor-activated PLC signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly culture

Flies (Drosophila melanogaster) were reared on medium containing corn flour, sugar, yeast powder and agar, along with antibacterial and antifungal agents. Flies were maintained at 25°C and 50% relative humidity. There was no internal illumination within the incubator and the flies were subjected to light pulses of short duration only when the incubator door was opened.

Fly stocks

The wild-type strain was Red Oregon-R. The following fly lines were obtained from Bloomington stock center (Indiana, USA): UAS-PI4KIIα RNAi (BL# 35278), UAS-PI4KIIIα RNAi (BL# 38242), UAS-PI4KIIIβ RNAi (BL# 29396), UAS-stmA RNAi (BL# 39062), UAS-dTTC7 RNAi (BL# 44482), stmA18-2/CyO (BL# 34519) and norpAH52(BL# 27334). rdgB9was obtained from David Hyde (University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN). trp::PLCδ-PH-GFP flies and dPIP5K18 mutant were generated in our laboratory and have been previously described (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). The PI4KIIIaXE45B mutant and genomic rescue flies were obtained from Hugo Bellen (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). The Gal4-UAS binary expression system was used to drive expression of transgenic constructs. To drive expression in eyes, GMR-Gal4 was used (Ellis et al., 1993).

Molecular biology

The human PI4KIIIα along with the FLAG epitope tag was amplified from the p3XFLAG::hPI4KIIIα-CMV10 construct, obtained from Pietro De Camilli (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT), and cloned through EcoRI and XhoI sites. The kinase-dead mutant of human PI4KIIIα with the HA epitope tag was amplified from the pcDNA3.1-HA::hPI4KIIIαKD construct from Tamas Balla (NIH, USA) and cloned through EcoRI and XhoI sites. The mouse Efr3B along with the HA epitope tag was amplified from the pcDNA3.0-HA::mEfr3B construct, obtained from Pietro De Camilli, and cloned through EcoRI and NotI sites. The human TTC7B was amplified from the iRFP::TTC7B construct, obtained from Addgene (plasmid #51615, deposited by Tamas Balla; Hammond et al., 2014), and cloned through NotI and XhoI sites. The P4M domain was amplified from the GFP::P4M-SidM construct, also from Addgene (plasmid #51469, deposited by Tamas Balla; Hammond et al., 2014), and cloned through NotI and XbaI sites. All transgenes were cloned into either pUAST-attB or pUAST-attB-GFP vectors using suitable restriction enzyme-based methods. Site-specific integration (Fly Facility, NCBS, Bangalore) at an attP2 landing site on the third chromosome was used to generate transgenic flies.

Western immunoblotting

Heads from 1-day-old flies were homogenized in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer followed by boiling at 95°C for 5 min. Samples were separated using SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane [Hybond-C Extra (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK)] using semidry transfer assembly (Bio-Rad, CA). Following blocking with 5% Blotto (sc-2325, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX), membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in appropriate dilutions of primary antibodies [anti-α-tubulin, 1:4000 (E7, DSHB, IA); anti-Gαq, 1:1000 (generated in-house); anti-TRP, 1:5000 (generated in-house); anti-Rh1, 1:200 (4C5, DSHB); anti-INAD, 1:1000 (a gift from Susan Tsunoda); anti-NORPA, 1:1000 (a gift from Armin Huber); anti-dPIP5K, 1:1000 [generated in-house (Chakrabarti et al., 2015)] mouse anti-GFP, 1:2000 (sc-9996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-HA, 1:1000 (2367S, Cell Signaling Technology, MA) and mouse anti-FLAG, 1:1000 (F1804, Sigma-Aldrich, MO)]. Protein immunoreacted with the primary antibody was visualized after incubation in 1:10,000 dilution of appropriate secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, PA) for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were developed with ECL (GE Healthcare) and imaged using a LAS 4000 instrument (GE Healthcare).

RNA extraction and Q-PCR analysis

RNA was extracted from Drosophila retinae using TRIzol reagent (15596018, Life Technologies, CA). To obtain the retina, flies were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for 1 min, following which they were transferred to glass vials containing acetone and stored for 2 days at −80°C. Purified RNA was treated with amplification grade DNase I (18068015, Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA). cDNA conversion was performed with SuperScript II RNase H– Reverse Transcriptase (18064014, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and random hexamers (N8080127, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) was performed using Power SybrGreen PCR mastermix (4367659, Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) in an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast real-time PCR instrument. Primers were designed at the exon–exon junctions following the parameters recommended for Q-PCR. Transcript levels of the ribosomal protein 49 (RP49) were used for normalization across samples. Three separate samples were collected from each genotype, and duplicate measures of each sample were conducted to ensure the consistency of the data. The primers used were as follows:

RP49 fwd, 5′-CGGATCGATATGCTAAGCTGT-3′; RP49 rev, 5′-GCGCTTGTTCGATCCGTA-3′; CG10260 (PI4KIIIα) fwd, 5′-GAGGAACAGATCACGGAATGGCG-3′; CG10260 (PI4KIIIα) rev, 5′-CCTCCTCATCAATGATCTCCGCG-3′; CG2929 (PI4KIIα) fwd, 5′-TATGCACGGAGTTGTGACCCCC-3′; CG2929 (PI4KIIα) rev, 5′-ACTTGTGGCTGCTCCACCCG-3′; CG7004 (PI4KIIIβ) fwd, 5′-TTCGGGTGAGATGGATGCGG-3′; CG7004 (PI4KIIIβ) rev, 5′-GTCCAATTCGGTGGAAGCGG-3′; CG8739 (stmA) fwd, 5′-GTGGAAATGTCCTGCAACGA-3′; CG8739 (stmA) rev, 5′-GTGGGGGAAGGAAATGGC-3′; CG8325 (TTC7) fwd, 5′-GGAGACGGTAAAGCAAGGTCTG-3′; CG8325 (TTC7) rev, 5′-CGTTCCCATCAAACTGCACA-3′; Gqα fwd, 5′-GAGAATCGAATGGAGGAATC-3′; Gqα rev, 5′-GCTGAGGACCATCGTATTC-3′.

Electroretinogram

Flies were anesthetized and immobilized at the end of a disposable pipette tip using a drop of colorless nail varnish. Recordings were performed using glass microelectrodes (640786, Harvard Apparatus, MA) filled with 0.8% w/v NaCl solution. Voltage changes were recorded between the surface of the eye and an electrode placed on the thorax. At 1 day, flies, both male and female, were used for recording. Following fixing and positioning, flies were dark adapted for 5 min. ERGs were recorded with 2 s flashes of green light stimulus, with 10 stimuli (flashes) per recording and 15 s of recovery time between two flashes of light. Stimulating light was delivered from an LED light source to within 5 mm of the fly's eye through a fiber optic guide. Calibrated neutral density filters were used to vary the intensity of the light source. Voltage changes were amplified using a DAM50 amplifier (SYS-DAM50, WPI, FL) and recorded using pCLAMP 10.4. Analysis of traces was performed using Clampfit 10.4 (Molecular Devices, CA).

For the temperature-dependent ERGs, a custom temperature controller was made by the in-house NCBS electronics workshop. The fly was immobilized, ventral side down, on paraffin wax, leaving the head free. The tip of a fine soldering iron was inserted into the wax just under the fly and used to maintain the fly at the required temperature. Once the set temperature was achieved, ERGs were recorded as described above. A known temperature-sensitive mutant fly was used (norpAH52) to characterize the system. As previously reported, this fly did not show an ERG response when the temperature was raised to 33°C but had a normal ERG response at 25°C, indicating that the temperature controller was working as expected.

Pseudopupil imaging

To monitor PI(4,5)P2 at the rhabdomere membrane in live flies, transgenic flies expressing PH-PLCδ::GFP [a PI(4,5)P2 biosensor; Chakrabarti et al., (2015)] were anesthetized and immobilized at the end of a pipette tip using a drop of colorless nail varnish and fixed in the light path of an Olympus IX71 microscope. The fluorescent deep pseudopupil (DPP, a virtual image that sums rhabdomere fluorescence from ∼20–40 adjacent ommatidia) was focused and imaged using a 10× objective. After dark adaptation for 6 min, images were taken by exciting GFP using a 90 ms flash of blue light and collecting emitted fluorescence. Similarly, flies expressing P4M::GFP (a PI4P biosensor; Hammond et al., 2014) were subjected to the same protocol in order to monitor PI4P levels. The DPP intensity was measured using ImageJ. The area of the pseudopupil was measured and the mean intensity values per unit area were calculated. Values are presented as mean±s.e.m.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunofluorescence studies, retinae from flies were dissected under a low level of red light in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Retinae were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS with 1 mg/ml saponin at room temperature for 30 min. Fixed eyes were washed three times in PBST (1× PBS+0.3% Triton X-100) for 10 min each. The sample was then blocked in a blocking solution (5% fetal bovine serum in PBST) for 2 h at room temperature, after which the sample was incubated with primary antibody in blocking solution overnight at 4°C on a shaker. The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-HA (1:50; 2367S, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-FLAG (1:100; F1804, Sigma) and chicken anti-GFP [1:5000; ab13970, Abcam (Cambridge, UK)]. Appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with a fluorophore were used at 1:300 dilutions [Alexa Fluor 488, 568 or 633 conjugated against IgG, Molecular Probes (Oregon, USA)] and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. Wherever required, during the incubation with secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 568–phalloidin [1:200; A12380 (Thermo Fisher Scientific)] was also added to the tissues to stain the F-actin. After three washes in PBST, sample was mounted in 70% glycerol in 1× PBS. Whole mounted preparations were imaged on Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope using Plan-Apochromat 60×, NA 1.4 objective (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell culture

S2R+ cells stably expressing Actin-GAL4 and under puromycin selection (obtained from Satyajit Mayor's laboratory, NCBS, Bangalore) were split every 4–5 days and grown at 25°C. They were maintained in Schneider's Drosophila insect medium (SDM; 21720024, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; 1600044, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine solution (10 ml/l; G1146, Sigma-Aldrich). They were transfected using Effectene as a transfection agent [301425, Qiagen (Hilden, Germany)]. The cells were plated in 12-well plates and 0.5 µg of desired DNA construct was used for transfections. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were allowed to adhere on glass coverslips in dishes for 1 h and fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1× M1 buffer (10× M1 buffer; 8.76 g sodium chloride, 0.373 g potassium chloride, 0.147 g calcium chloride, 0.203 g magnesium chloride, 4.76 g HEPES, 100 ml MilliQ water, pH 6.8–7) for 20 min. They were washed and permeabilized with 0.37% Igepal (I3021, Sigma) in 1× M1 buffer for 13 min. Blocking was performed in 1× M1 buffer containing 5% FBS and 1 mg/ml BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature, washed with 1× M1 several times, and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1–2 h at room temperature. Following this, they were stained with DAPI (1:3000; D1306, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and washed with 1× M1 buffer. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-HA (1:200; 2367S, Cell Signaling Technology) and mouse anti-FLAG (1:400; F1804, Sigma). Appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to a fluorophore were used at 1:300 dilution (A11001, Alexa Fluor 488 IgG, Molecular Probes). The cells were imaged on Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope using a Plan-Apochromat 60×, NA 1.4 objective (Olympus).

Lipid mass spectrometry

Lipid extraction

Drosophila retinae were dissected under red light or white light (as indicated by dark or light treatment) and stored in 1× PBS on dry ice until ready for extraction. The retinae were homogenized in 950 µl phosphoinositide elution buffer (PEB; 250 ml CHCl3, 500 ml methanol and 200 ml 2.4 M HCl), at which point the internal standards (see below) were added [mixture containing 50 ng PI, 25 ng PI4P, 50 ng PIP2, 0.2 ng phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) per sample]. Phase separation was achieved by adding 250 µl each of chloroform and 2.4 M HCl, followed by centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 min (4°C). The organic phase was extracted and washed with 900 µl lower-phase wash solution (LPWS; 235 ml methanol, 245 ml 1 M HCl and 15 ml CHCl3) and centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min (4°C). Lipids from the remaining aqueous phase were extracted by phase separation once again. The organic phases were collected and dried in a vacuum centrifuge. The dried lipid extracts were derivatized using 2 M TMS-diazomethane. 50 µl TMS-diazomethane was added to each tube and vortexed gently for 10 min. The reaction was neutralized using 10 µl glacial acetic acid.

Internal standards (IS) used were from Avanti (AL): phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) 17:0/14:1 (LM-1104); phosphatidylinositol (PI) 17:0/14:1 (LM-1504); phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P) 17:0/20:4 (LM-1901); and d5-phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate [PI(3,5)P2] 16:0/16:0 (850172).

Mass spectrometry

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to estimate phosphoinositide levels in Drosophila retinal extracts. The experiment was performed on an ABSciex 6500 Q-Trap machine connected to a Waters Acquity LC system. A 45% to 100% acetonitrile in water (with 0.1% formic acid) gradient over 20 min was used for separation on a 1 mm×100 mm UPLC C4 1.7 µM from Acquity. Gradient details are provided in Table S1. Analysis was performed on an ABSciex (Singapore) 6500 Q-Trap machine connected to the Waters Acquity LC system. The Q-Trap 6500 parameters were: curtain gas, 40; ion spray voltage, 4000; temperature, 400; GS1, 15; GS2, 15; declustering potential, 65; entrance potential, 11.4; collision energy, 30; collision exit potential, 12. Details of multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions used to identify lipid species and quantification are provided in Table S2.

Transmission electron micrscopy

Heads of 1-day-old flies were dissected and fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.2). They were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) for 1 h, dehydrated in ethanol and propylene oxide, and then embedded in Embed-812 resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Thin sections (∼50 nm) were stained in 4% uranyl acetate and 2.5% lead nitrate, and TEM images were captured using a transmission electron microscope (model 1010, JEOL). Images were processed with ImageJ. The detailed method is described in Yao et al. (2009).

Statistical analysis

An unpaired two-tailed t-test or ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test, were carried out where applicable. Effect size was calculated using standard statistical methods. Sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 (available at http://www.gpower.hhu.de/en.html).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the NCBS Mass Spectrometry Facility, Fly Facility and Imaging Facility at NCBS for support. The anti-NORPA antibody was a generous gift from Prof. Armin Huber (University of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany) and anti-INAD antibody was a kind gift from Prof. Susan Tsunoda (Colorado State University, CO). We are thankful to Prof. Hugo Bellen for the mutant PI4KIIIα alleles; the experiments performed by M. J. were done in Prof. Hugo Bellen's lab.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: R.P.; Methodology: S.S.B., U.B., D.S., R.T., R.P.; Validation: S.S.B., D.S., R.T.; Formal analysis: S.S.B., D.S., R.T., M.J., R.P.; Investigation: S.S.B., U.B., D.S., R.T., M.J.; Resources: S.S.B., U.B., M.J.; Writing - original draft: R.P.; Supervision: R.P.; Project administration: R.P.; Funding acquisition: R.P.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Centre for Biological Sciences - TIFR. R.P. is supported by a Wellcome Trust-DBT India Alliance Senior Fellowship (IA/S/14/2/501540). U.B. was supported by a fellowship from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, India. M.J. is supported by Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and Ramaligaswami Re-Entry Fellowship DBT India (BT/RLF/Re-Entry/06/2016). Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.217257.supplemental

References

- Audhya A. and Emr S. D. (2002). Stt4 PI 4-kinase localizes to the plasma membrane and functions in the Pkc1-mediated MAP kinase cascade. Dev. Cell 2, 593-605. 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00168-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird D., Stefan C., Audhya A., Weys S. and Emr S. D. (2008). Assembly of the PtdIns 4-kinase Stt4 complex at the plasma membrane requires Ypp1 and Efr3. J. Cell Biol. 183, 1061-1074. 10.1083/jcb.200804003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan S. S., Basu U. and Raghu P. (2015). Phosphoinositide signalling in Drosophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1851, 770-784. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla A., Tuymetova G., Tsiomenko A., Várnai P. and Balla T. (2005). A plasma membrane pool of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate is generated by phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type-III alpha: studies with the PH domains of the oxysterol binding protein and FAPP1. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1282-1295. 10.1091/mbc.e04-07-0578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla A., Kim Y. J., Varnai P., Szentpetery Z., Knight Z., Shokat K. M. and Balla T. (2008). Maintenance of hormone-sensitive phosphoinositide pools in the plasma membrane requires phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 711-721. 10.1091/mbc.e07-07-0713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin J. M., Wu X., Christiano R., Oh M. S., Schauder C. M., Gazzerro E., Messa M., Baldassari S., Assereto S., Biancheri R. et al. (2016). The leukodystrophy protein FAM126A (hyccin) regulates PtdIns(4)P synthesis at the plasma membrane. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 132-138. 10.1038/ncb3271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist B. T., Shortridge R. D., Schneuwly S., Perdew M., Montell C., Steller H., Rubin G. and Pak W. L. (1988). Isolation of a putative phospholipase C gene of Drosophila, norpA, and its role in phototransduction. Cell 54, 723-733. 10.1016/S0092-8674(88)80017-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojjireddy N., Guzman-Hernandez M. L., Reinhard N. R., Jovic M. and Balla T. (2015). EFR3s are palmitoylated plasma membrane proteins that control responsiveness to G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Cell Sci. 128, 118-128. 10.1242/jcs.157495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill J. A., Hime G. R., Scharer-Schuksz M. and Fuller M. T. (2000). A phospholipid kinase regulates actin organization and intercellular bridge formation during germline cytokinesis. Development 127, 3855-3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess J., Del Bel L. M., Ma C.-I. J., Barylko B., Polevoy G., Rollins J., Albanesi J. P., Krämer H. and Brill J. A. (2012). Type II phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase regulates trafficking of secretory granule proteins in Drosophila. Development 139, 3040-3050. 10.1242/dev.077644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti P., Kolay S., Yadav S., Kumari K., Nair A., Trivedi D. and Raghu P. (2015). A dPIP5K dependent pool of phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2) is required for G-protein coupled signal transduction in Drosophila photoreceptors. PLoS Genet. 11, e1004948 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekaran S. and Sarla N. (1993). Phenotypes of lethal alleles of the recessive temperature sensitive paralytic mutant stambh A of Drosophila melanogaster suggest its neurogenic function. Genetica 90, 61-71. 10.1007/BF01435179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J., Nakatsu F., Baskin J. M. and De Camilli P. (2015). Plasticity of PI4KIIIα interactions at the plasma membrane. EMBO Rep. 16, 312-320. 10.15252/embr.201439151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J., Anderson K. E., Juvin V., Smith T. S., Karpe F., Wakelam M. J. O., Stephens L. R. and Hawkins P. T. (2011). Quantification of PtdInsP3 molecular species in cells and tissues by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 8, 267 10.1038/nmeth.1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft S., Garner K., Yadav S., Gomez-Espinoza E. and Raghu P. (2016). RdgBα reciprocally transfers PA and PI at ER-PM contact sites to maintain PI(4,5)P2 homoeostasis during phospholipase C signalling in Drosophila photoreceptors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 44, 286-292. 10.1042/BST20150228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M. C., O'Neill E. M. and Rubin G. M. (1993). Expression of Drosophila glass protein and evidence for negative regulation of its activity in non-neuronal cells by another DNA-binding protein. Development 119, 855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond G. R. V., Machner M. P. and Balla T. (2014). A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J. Cell Biol. 205, 113-126. 10.1083/jcb.201312072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R. C., Raghu P., Moore S., Juusola M., Baines R. A. and Sweeney S. T. (2001). Calcium influx via TRP channels is required to maintain PIP2 levels in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron 30, 149-159. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00269-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R. C., Liu C.-H., Randall A. S. and Sengupta S. (2015). In vivo tracking of phosphoinositides in Drosophila photoreceptors. J. Cell Sci. 128, 4328-4340. 10.1242/jcs.180364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F.-D. D., Matthies H. J. G., Speese S. D., Smith M. A. and Broadie K. (2004). Rolling blackout, a newly identified PIP2-DAG pathway lipase required for Drosophila phototransduction. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1070-1078. 10.1038/nn1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolay S., Basu U. and Raghu P. (2016). Control of diverse subcellular processes by a single multi-functional lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2]. Biochem. J. 473, 1681-1692. 10.1042/BCJ20160069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M. A. (2008). Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 99-111. 10.1038/nrm2328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu F., Baskin J. M., Chung J., Tanner L. B., Shui G., Lee S. Y., Pirruccello M., Hao M., Ingolia N. T., Wenk M. R. et al. (2012). PtdIns4P synthesis by PI4KIIIα at the plasma membrane and its impact on plasma membrane identity. J. Cell Biol. 199, 1003-1016. 10.1083/jcb.201206095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevoy G., Wei H.-C., Wong R., Szentpetery Z., Kim Y. J., Goldbach P., Steinbach S. K., Balla T. and Brill J. A. (2009). Dual roles for the Drosophila PI 4-kinase four wheel drive in localizing Rab11 during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 187, 847-858. 10.1083/jcb.200908107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghu P., Yadav S. and Mallampati N. B. N. (2012). Lipid signaling in Drosophila photoreceptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 1154-1165. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. G. (2001). Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 281-312. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers R. S. and Schwarz T. L. (1999). A genetic method for generating Drosophila eyes composed exclusively of mitotic clones of a single genotype. Genetics 152, 1631-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi D. and Padinjat R. (2007). RdgB proteins: Functions in lipid homeostasis and signal transduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 692-699. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Várnai P. and Balla T. (1998). Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J. Cell Biol. 143, 501-510. 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H.-C., Rollins J., Fabian L., Hayes M., Polevoy G., Bazinet C. and Brill J. A. (2008). Depletion of plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 reveals essential roles for phosphoinositides in flagellar biogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1076-1084. 10.1242/jcs.024927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. J. and Ostroy S. E. (1987). Studies of theDrosophila norpA phototransduction mutant. J. Comp. Physiol. A 161, 785-791. 10.1007/BF00610220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Chi R. J., Baskin J. M., Lucast L., Burd C. G., De Camilli P. and Reinisch K. M. (2014). Structural insights into assembly and regulation of the plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase complex. Dev. Cell 28, 19-29. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S., Garner K., Georgiev P., Li M., Gomez-Espinosa E., Panda A., Mathre S., Okkenhaug H., Cockcroft S. and Raghu P. (2015). RDGBα, a PtdIns-PtdOH transfer protein, regulates G-protein-coupled PtdIns(4,5)P2 signalling during Drosophila phototransduction. J. Cell Sci. 128, 3330-3344. 10.1242/jcs.173476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S., Thakur R., Georgiev P., Deivasigamani S., K H., Ratnaparkhi G. and Raghu P. (2018). RDGBα localization and function at a membrane contact site is regulated by FFAT/VAP interactions. J. Cell Sci. 131, jcs207985 10.1242/jcs.207985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Jaiswal M., Charng W.-L., Gambin T., Karaca E., Mirzaa G., Wiszniewski W., Sandoval H., Haelterman N. A., Xiong B. et al. (2014). A drosophila genetic resource of mutants to study mechanisms underlying human genetic diseases. Cell 159, 200-214. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Denef N., Tang C. and Schüpbach T. (2011). Drosophila PI4KIIIalpha is required in follicle cells for oocyte polarization and Hippo signaling. Development 138, 1697-1703. 10.1242/dev.059279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C. K., Lin Y. Q., Ly C. V., Ohyama T., Haueter C. M., Moiseenkova-Bell V. Y., Wensel T. G. and Bellen H. J. (2009). A synaptic vesicle-associated Ca 2+ channel promotes endocytosis and couples exocytosis to endocytosis. Cell 138, 947-960. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.