Individuals in treatment for alcohol use disorder, who were prescribed to take an effective medication for the disorder on a daily basis, tended to not take their medication on the weekend and following days of heaving drinking or strong urges to drink.

Keywords: Naltrexone, Alcohol use disorder, Medication adherence, Mobile health, Medication Event Monitoring System

Abstract

Background

Adherence to medications for treating alcohol use disorder (AUD) is poor. To identify predictors of daily naltrexone adherence over time, a secondary data analysis was conducted of a trial evaluating a mobile health intervention to improve adherence.

Methods

Participants seeking treatment for AUD (n = 58; Mage = 38 years; 71% male) were prescribed naltrexone for 8 weeks. Adherence was tracked using the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS). In response to daily text messages, participants reported the previous day’s alcohol use, craving, and naltrexone side effects. Using multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM), we examined baseline dispositional factors and within-person, time-varying factors as predictors of daily adherence.

Results

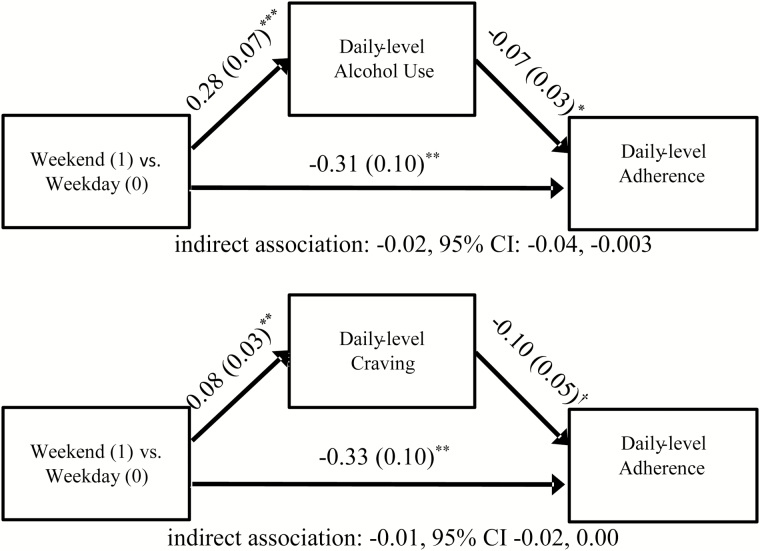

Naltrexone adherence decreased over time. Adherence was higher on days when individuals completed daily mobile assessments relative to days when they did not (odds ratio [OR] = 2.53, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.61 to 3.98), irrespective of intervention condition. Days when individuals drank more than their typical amount were related to lower next-day adherence (OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99). A similar pattern was supported for craving (OR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.98). Weekend days were associated with lower adherence than weekdays (OR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.86); this effect was partly mediated by heavier daily drinking (indirect effect = −0.02, 95% CI −0.04 to −0.003) and stronger-than-usual craving (indirect effect = −0.01, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.00) on weekend days.

Conclusions

The results further demonstrate the need to improve adherence to AUD pharmacotherapy. The present findings also support developing interventions that target daily-level risk factors for nonadherence. Mobile health interventions may be one means of developing tailored and adaptive adherence interventions.

Introduction

Naltrexone, a competitive opioid receptor antagonist, is one of the few FDA-approved medications for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have evaluated the effectiveness of naltrexone in treating AUD. Results suggest that 4–12 weeks of oral naltrexone treatment (taken once daily) reduces drinking quantity and relapse to heavy drinking, but the effects versus placebo are generally modest [1–3].

One factor that may account for modest effects of naltrexone is low medication adherence. A systematic review by Swift et al. [4] found that only 29% of naltrexone randomized controlled trials (RCTs) monitored adherence using methods rated as medium assurance (electronic monitoring of pill bottle opening via Medication Event Monitoring System [MEMS], and the use of riboflavin as a biochemical marker that is consumed with the medication) or high assurance (supervised medication administration and extended-release formulation). When assessed objectively using MEMS, prior naltrexone trials have reported that study participants took naltrexone 70%–80% of the days [5–7]. In many trials, naltrexone did not significantly affect drinking outcomes relative to placebo when using intent-to-treat analyses but significantly reduced drinking-related outcomes when limiting analyses to adherent participants [5, 8, 9]. Furthermore, adherent individuals, typically defined as taking the medication as directed ≥80% of the time, showed significantly better response to naltrexone relative to placebo than did nonadherent individuals [6, 7, 10, 11]. Thus, overall adherence level appears to affect the efficacy of naltrexone.

In spite of the accepted clinical importance of adherence, data concerning the factors that affect adherence to naltrexone are limited. The few extant studies to investigate predictors of naltrexone adherence have focused primarily on baseline participant characteristics. Compared with nonadherent individuals, adherent individuals tended to be older [5], have lower obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors toward drinking, have higher familial support, and take other medications [6]. Lower baseline drinking has predicted better adherence [6] or had no effect [5]. Other factors such as gender and alcohol dependence severity have been unrelated to adherence [5].

While person-level predictors of adherence can inform decisions to intervene with subgroups at risk for nonadherence, targeting daily adherence to naltrexone may be particularly important because acute or subacute naltrexone administration reduces event-level craving and alcohol consumption [12]. Mobile health (mHealth) interventions have gained momentum as a tool to support clients and can improve daily medication adherence. mHealth interventions have traditionally targeted unintentional nonadherence (e.g., forgetting to take one’s medication) by providing text message medication reminders [13, 14]. Importantly, mHealth interventions designed to prompt individuals to remind them to take their medication have improved adherence in RCTs for a variety of chronic medical diseases [15]. Prior work has also found that daily self-monitoring of health outcomes, like blood pressure, similarly improve adherence to associated medications even though the self-monitoring did not ask about adherence [16].

In the context of naltrexone adherence, however, a RCT by Stoner et al. [17] evaluating an mHealth intervention that involved text messages (SMS) to self-monitor adherence and to provide medication reminders did not alter adherence rates relative to a control condition that received no adherence-related SMS. Thus, it is critical to identify and address proximal factors that relate to daily adherence that can inform targeted or adaptive adherence mHealth interventions. Few studies have described daily processes that influence naltrexone adherence. One investigation of adolescents taking naltrexone for 8 to 10 days found that alcohol use did not predict same-day adherence [18]. Additional predictors and prospective predictors have not been investigated; accordingly, identifying such predictors is the focus of this investigation.

Changes in one’s routine that could increase the likelihood of forgetting or being unable to take medication could predict nonadherence and could be used to tailor mHealth interventions to improve their effectiveness. For instance, unintentional nonadherence could occur on days after heavy alcohol use as a result of hangover symptoms, such as fatigue and memory impairments [19, 20]. Furthermore, deliberate nonadherence could occur following heavy drinking days if one believes that medication is unhelpful or if the treatment goal is abandoned due to the abstinence violation effect [21]. A similar process may implicate strong craving in next-day nonadherence if one suspects that the treatment is ineffective. While prior research has found that heavier alcohol use has been associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) [22–24], the roles of alcohol use and craving in subsequent naltrexone nonadherence have not been clarified.

In addition, contextual factors associated with day of the week may influence adherence to naltrexone. Adherence to other medications, such as ART [25–27] and antidiabetic medication [28], tends to be lower on weekends than weekdays. This could be partly attributable to unintentional nonadherence (e.g., forgetfulness due to change in routine) or planned nonadherence (e.g., choosing not to take medication in anticipation of drinking episodes). In one study, ART adherence was lower on weekends (defined as Friday, Saturday, and Sunday) than weekdays, and the difference between weekend and weekday adherence was largest for heavy drinkers [26]. As heavy drinkers tend to have their heaviest drinking episodes on weekends [29], weekend effects would also be expected to be observed with regard to medication adherence for the treatment of AUD, particularly to the extent that alcohol use and craving account for nonadherence. In other words, heavier drinking and/or stronger craving on weekends may account for, or mediate, the effect of weekends versus weekdays on nonadherence. Any such effect would have important treatment implications because it would suggest that heavy drinking patients might not be taking naltrexone on days when the medication effects are particularly needed.

Finally, nonadherence may occur to avoid medication side effects. For instance, individuals who report more side effects show increased nonadherence to ART [30] and psychiatric medications [31, 32]. While naltrexone is generally well tolerated, compared with control or no treatment conditions, several common side effects have been identified in AUD treatment, including nausea, dizziness, weakness, sleep difficulties, and anxiety [33, 34]. In a review of 11 studies, individuals were more likely to discontinue naltrexone treatment (10%) versus control treatment (4%) due to side effects [33]. Thus, experiencing more side effects could similarly reduce adherence to naltrexone.

Understanding the extent to which person-level predictors and daily-level predictors such as self-monitoring, drinking and craving level, weekend/weekday variation, and side effects influence adherence to naltrexone would inform the development of mHealth interventions to promote adherence. To this end, the primary aim of this study is to evaluate predictors of daily adherence to naltrexone among treatment-seeking, outpatient adults diagnosed with AUDs. The present study addressed this aim through a secondary data analysis of the aforementioned open-label, 8-week RCT conducted by Stoner et al. [17] that evaluated the effects of an mHealth intervention on naltrexone adherence monitored daily using MEMS. First, using this sample, we tested effects of person-level characteristics (e.g., gender, age, and baseline alcohol use) on change in adherence over time. Second, we evaluated the effect of completing daily mobile assessments of drinking, craving, and side effects on adherence. As daily self-monitoring in prior research has had generalizable effects on medication adherence, we hypothesized that adherence would be higher on days when individuals completed the daily assessments versus did not complete the assessments. Third, we considered additional daily-level predictors of adherence, including daily drinking, craving, and side effects. It was hypothesized that each of these factors would reduce naltrexone adherence. Finally, we compared adherence on weekends to weekdays and conducted mediation analysis to evaluate the extent to which these effects were accounted for by variations in drinking and craving on weekends. It was anticipated that adherence would be lower on weekends than weekdays, and that the association would be explained by higher drinking and stronger craving that occur on weekend days.

Method

Participants

The original study included 76 participants with AUD who were 21–55 years old, desired assistance to reduce or stop drinking alcohol, and were willing to take naltrexone [17]. Individuals were excluded for likelihood of pregnancy; opioid use or drug use other than alcohol, nicotine, or cannabis in the prior 30 days; history of opioid dependence or psychotic disorder; use of psychiatric medication other than antidepressants; concurrent treatment for alcohol use other than Alcoholics Anonymous; or a requirement to attend treatment. The present investigation focuses on the subsample of participants (n = 58) from whom MEMS data were obtained.

Procedures

The full study protocol was previously published [35]; relevant details are summarized here. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All randomized participants were provided with an initial 1-month supply of naltrexone (50 mg/day) and an Android smartphone with 8 weeks of unlimited service and instructed on using the phone to respond to question prompts. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n = 37) or control (n = 39) condition. The intervention condition, called Adaptive, Goal-directed Adherence Tracking and Enhancement (AGATE-Rx), reminded participants to take the study medication via SMS. A hyperlink in the message launched the smartphone web browser to assess adherence on the previous day. Over time, the frequency of medication reminders changed according to self-reported adherence performance. Intervention participants also received a Smartphone Alcohol and Side Effects Diary (SASED), which included a daily SMS prompt with a hyperlink to assess side effects and alcohol use and craving. The control condition received SASED prompts but did not receive adherence prompts. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee and Quorum Review (Seattle, WA), ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01349985.

Measures

Alcohol dependence scale (Baseline)

The alcohol dependence scale (ADS) is a 25-item scale assessing alcohol dependence symptoms and intensity during the past 12 months [36], and has high test–retest reliability and validity [37, 38]. Items were summed to yield a quantitative index (ranging 0–40), with higher scores indicating greater dependence.

Obsessive-compulsive drinking scale (Baseline)

The 14-item obsessive-compulsive drinking scale (OCDS) assesses obsessive and compulsive characteristics of drinking [39] with high levels of test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and content and criterion validity [39, 40].

Alcohol use

The Timeline Follow-back (TLFB) calendar method [41] was used to quantify alcohol use during the 90 days preceding Baseline, including average standard drinks per drinking day. The method has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity in a number of studies [41, 42]. As part of the SASED assessment, drinking was queried daily via smartphone. Participants were asked how many standard drinks they consumed on the prior day, with 14 response options ranging from 0 to 13+.

Craving

As part of the SASED assessment, a craving intensity item (“At its most severe point, how strong was your craving to drink alcohol?”) was administered daily, referring to the preceding day. Single-item measures of craving have been shown to work well to capture alcohol craving and are well suited to repeated assessments using mobile electronic devices [43, 44]

Side effects

As part of the SASED assessment, side effects were queried daily with the question “Are you having any of the following (please check all that apply)?”. Participants rated each side effect (anxiety, light-headedness, increased thirst, nausea, sleep problems, fatigue, or weakness) as present/absent on the previous day. Daily responses were summed to compute an aggregate side effects variable. The average daily internal consistency was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74), which supported aggregating the responses into a daily side effect sum score.

MEMS (MWV Healthcare)

Participants received medication in a standard pill bottle with an electronic, chip-embedded cap that logged all openings. We attempted to retrieve caps from all randomized participants; however, some caps could not be retrieved. Raw MEMS adherence data were downloaded from 60 returned caps; however, two participants disclosed information invalidating their MEMS data (discarding pills, taking half- or double doses), which resulted in the final sample of 58 participants.

Statistical Analysis

All models were conducted in a multilevel framework using Mplus v7.4 [45]. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used to estimate all models, which produces valid standard error estimates with nonnormal variables [46] and handles missing data using full information maximum likelihood (FIML). Using FIML, rather than imputing worst-case scenario outcomes (e.g., in this case, nonadherence to naltrexone), has been shown to produce less-biased estimates in the context of alcohol clinical trials [47].

The first set of analyses tested associations between baseline participant-level factors and adherence over time. Change in adherence over time was modeled using multilevel modeling. To accomplish this, adherence on each day (coded as 0 = nonadherent, 1 = adherent) was specified as a dichotomous outcome at Level 1 of the model, with daily adherence observations nested within participants (Level 2). We first specified trends in adherence by entering successive polynomial effects of time (linear then quadratic) at Level 1, along with corresponding random intercepts and slopes for these time effects. To facilitate model estimation, time was scaled such that each day was coded as a proportion of the total study period (i.e., Day 1 = 0.000, Day 2 = 0.036, Day 3 = 0.054, …, Day 56 = 1.000). Nested model testing was used to determine which fixed and random effects for time should be included in the model by retaining those that significantly improved model fit. Nested models were compared using chi-square difference tests based on log-likelihood values (reported in the Results section as Delta −2LL) and scaling correction factors obtained with MLR estimation [48]. In a single model, adherence patterns were then predicted by examining associations of between-person predictors (including age, gender, baseline drinking amount from TLFB, baseline ADS score, and baseline OCDS score) as well as intervention condition (0 = “control”; 1 = “intervention”) with the random intercept (representing adherence on Day 1) and any supported random slope term(s).

The second set of analyses focused on relations between daily-level (within-person) predictors and adherence in the total sample using multilevel structural equation models (MSEM). The advantage of MSEM is that it is possible to disaggregate within-person and between-person associations, thereby allowing for an examination of individual differences in overall adherence patterns as well as day-to-day fluctuations in adherence. Past-day drinking and craving, and same-day side effects and completion (vs. noncompletion) of SASED assessments (all person-centered) were each separately examined as Level 1 predictors of adherence. Analyses controlled for between-person associations between each variable and adherence. Random effects for the Level 1 predictor on adherence were evaluated. Models examining daily-level predictors controlled for intervention condition, time effects, and between-subjects factors that predicted adherence.

The third set of analyses investigated weekend/weekday variability in adherence and the explanatory role of daily alcohol use and craving. Consistent with prior work on day-of-the-week patterns in medication adherence, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday were defined as weekend days (coded 1), and the remaining days were considered nonweekend days (coded 0) [26, 27]. The daily-level (within-person) weekend/weekday variable was examined as a Level 1 predictor of same-day adherence, adjusting for intervention condition, time effects, and between-subjects factors related to adherence. Then, multilevel mediation analysis was conducted to estimate the indirect effect of weekend/weekday on adherence mediated via daily alcohol use and craving. Specifically, within-person changes in alcohol use were added to the model by specifying weekend/weekday as a predictor of within-person changes in alcohol use and, in turn, within-person changes in alcohol use were specified as a predictor of next-day adherence. The same model was investigated with craving as the mediator. Multilevel mediation analysis was conducted to disaggregate within- and between-person sources of variance [49]. A 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect was computed using the Asymmetric Confidence Interval Method (ACI), using Prodclin software, taking into account the nonnormally distributed indirect effect [50]. This method has been shown in simulation studies to have adequate Type 1 error rates in MSEM models with the size and number of clusters in our sample [51].

Results

Sample Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of all randomized participants (N = 76) and changes in self-reported drinks per day and craving have been previously described [17]. Table 1 includes descriptive characteristics of the subsample with valid MEMS data (n = 58), who are the focus of this investigation; they did not significantly differ from those without valid MEMS data (n = 18) with respect to variables summarized in Table 1 (ps > .05). The percentage of daily assessments completed was reported in the original publication by Stoner et al. [17]. Over Days 1–56, control participants averaged 39.2 [SD = 15.6] responses and intervention participants averaged 43 [SD = 12.50] responses, which did not differ between groups (p = .40). Participants reported, using daily mobile assessments, drinking alcohol on 42% of the days (SD = 35%) averaging 4.96 (SD = 1.76) drinks per drinking day, and reported an average craving of 2.16 (SD = 1.22) on a scale of 0 (“none at all”) to 6 (“strong urge and would have drunk alcohol if it were available”). Most participants (n = 48, 82.8%) reported at least one side effect during the trial. On average, participants reported at least one side effect on 25% of the days (SD = 31%). The most commonly reported side effect was sleep effects (mean = 12% of days; SD = 21%), then nausea (11%, SD = 25%), anxiety (9%, SD = 20%), weakness (8%, SD = 20%), dizziness (7%, SD = 17), and thirst (7%, SD = 14%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

| Control (n = 30) | Intervention (n = 28) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | t-test | ||

| Age (years) | 37.17 (8.82) | 39.75 (9.33) | −1.08 |

| Drinks per drinking day | 11.16 (6.16) | 8.66 (4.53) | 1.75 |

| Alcohol Dependence Scale | 16.77 (8.73) | 13.82 (7.01) | 1.41 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking Scale | 1.73 (0.67) | 1.66 (0.72) | 0.36 |

| N (%) | χ2 | ||

| Sex (female) | 5 (16.7) | 12 (42.9) | 4.80* |

| Income (above $20,000) | 13 (43.3) | 20 (74.1) | 5.51* |

| Race (White, non-Hispanic) | 9 (30.0) | 12 (42.9) | 1.04 |

| Education (Bachelor’s degree or higher) | 4 (13.3) | 8 (28.6) | 2.05 |

| DSM-IV-TR alcohol dependent | 20 (69.0) | 20 (74.1) | 0.18 |

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) are reported for continuous variables along with corresponding t-test comparing values between the control and intervention conditions. Similarly, sample size (N) and percentages are provided for dichotomous variables alongside chi-square (χ2) test statistics for differences between control and intervention conditions.

† p

< .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Baseline Predictors of Adherence

We first fit linear and quadratic time trends to model changes in adherence. Inclusion of the quadratic effect of time (along with a random slope factor) did not improve model fit relative to a linear time effect only (Delta −2LL = 3.31, df = 3, p > .05). Thus, a linear effect of time was supported and retained. The final model for the effects of time indicated that the log of the odds of adherence versus nonadherence declined significantly over time on average according to a linear trend (b = −2.50, SE = 0.43, p < .001), with significant variability across participants in the linear slope (b = 5.95, SE = 2.74, p = .03).

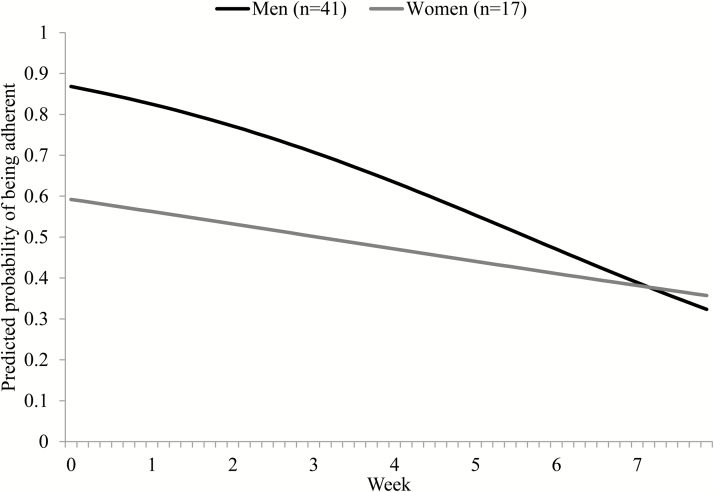

Next, we entered into the model the between-person predictors of individual differences in change in adherence over time (i.e., the random quadratic slope; Table 2). Between-person variance in decline in adherence was not significantly predicted by age, income, baseline drinking, ADS, or OCDS. Being a woman was associated with a slower decline in adherence over time relative to being a man. Figure 1 shows the model-implied predicted probability of adherence over time separately for men and women. There was no intervention effect on change in adherence. There was also no significant relationship between these between-person predictors and individual differences in the adherence intercept (i.e., adherence on Day 1 of the trial; Table 2).

Table 2.

Multilevel Model of Associations Between Dispositional Factors and Adherence to Naltrexone Over Time

| Dependent variables | Independent variables | B | SE | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in adherence (random linear slope) | Age | 0.00 | 0.04 | .99 | [−0.07 to 0.07] |

| Gender (Female = 1) | 1.70* | 0.85 | .045 | [0.04 to 3.36] | |

| Income | −1.23 | 0.96 | .20 | [−3.1 to −0.65] | |

| Condition (Intervention = 1) | −1.11 | 1.15 | .33 | [−3.36 to 1.13] | |

| Baseline drinks | 0.01 | 0.01 | .31 | [−0.09 to 0.29] | |

| Baseline ADS | 0.01 | 0.10 | .92 | [−0.10 to 0.11] | |

| Baseline OCDS | −0.26 | 0.87 | .77 | [−-1.97 to 1.46] | |

| Day 1 adherence (random intercept) | Age | 0.01 | 0.04 | .71 | [−0.06 to 0.09] |

| Gender (Female = 1) | −1.53 | 1.03 | .14 | [−-3.55 to 0.50] | |

| Income | −0.40 | 0.89 | .66 | [−2.13 to 1.34] | |

| Condition (Intervention = 1) | 1.55† | 0.89 | .08 | [−0.10 to 2.74] | |

| Baseline drinks | −0.05 | 0.10 | .62 | [−0.11 to 0.16] | |

| Baseline ADS | 0.03 | 0.07 | .69 | [−0.11 to 0.16] | |

| Baseline OCDS | −0.44 | 0.79 | .58 | [−1.98 to 1.10] |

Unstandardized parameter estimates shown. Time was modeled as a random linear slope (not shown). Coefficients represent relationships between the dispositional factors and individual differences in the change in adherence over time (random linear slope) as well as individual differences in adherence on Day 1 (random intercept). The covariance between the random intercept and random linear slope was estimated in the model but was not statistically significant and is not depicted in the table. Time was coded with each day represented as proportion of the total trial length (i.e., by dividing each day by 56).

ADS alcohol dependence scale; OCDS obsessive-compulsive drinking scale; SE standard error.

† p

< .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Fig. 1.

The linear trajectory model estimated daily probability of participants being adherent to naltrexone is depicted over the course of an 8-week trial separately for men and women. Additional covariates in the model (i.e., baseline ADS, OCDS, drinking level, income, and age) were grand-mean centered to produce gender-specific trajectories at the weighted average of these covariates. Adjusting for the covariates, there was a nonsignificant trend (p = .14) for women having lower adherence at Day 1 (i.e., intercept). Women had a significantly slower rate of decline in adherence during the trial (p = .045) than men. Twenty participants (34%) were lost to follow-up and thus did not have adherence data for the second half of the study, which was addressed using FIML. ADS alcohol dependence scale; OCDS obsessive-compulsive drinking scale; FIML full information maximum likelihood.

Daily Predictors of Adherence During Treatment

We next examined the daily-level predictors of adherence in separate models. All models controlled for the effects of time as well as the effect of intervention condition and gender on the random intercept and linear time trend. For each model, we first determined whether a random slope for the within-person association between the daily-level predictor and adherence should be included in the model. A random effect of SASED assessment completion on adherence was included in the model because it improved fit (Delta −2LL = 12.09, df = 2, p < .05). However, including a random effect for the within-person association for alcohol use, craving, side effects, or weekend effect did not improve the fit of the model (all ps > .05); consequently, these daily-level predictors were modeled as fixed effects only.

Table 3 shows the results of the daily-level predictor models. There was a significant daily-level association between SASED assessment completion and adherence, such that days on which participants completed SASED assessments corresponded with significantly improved adherence. At the between-person level, completion rate of SASED assessments was not associated with adherence on Day 1 (i.e., the intercept term) or subsequent change in adherence over time (i.e., the slope term). The effect of SASED assessments on adherence did not differ between the intervention and control conditions (b = .386, SE = 0.50, p = .14). Numbers of side effects per day were not significantly associated with same-day adherence, nor was the average number of side effects related to initial adherence or change in adherence at the between-person level (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of MSEM Models Examining Daily-Level Predictors of Adherence

| Estimatea | SE | p | 95% CI | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: SASED assessments | |||||

| Mean within-person daily-level associationb | 0.93*** | 0.23 | <.001 | [0.48 to 1.38] | 2.53*** |

| Random variance in within-person, daily-level associationb | 0.81† | 0.46 | .08 | [−0.10 to 1.72] | |

| Between-person association with interceptc | 1.28 | 0.77 | .10 | [−0.23 to 2.79] | |

| Between-person association with linear slopec | 1.37 | 1.10 | .21 | [−0.78 to 3.53] | |

| Model 2: Side effects | |||||

| Within-person, daily-level associationd | 0.05 | 0.10 | .64 | [−0.15 to 0.25] | 1.05 |

| Between-person association with interceptc | −0.42 | 0.65 | .52 | [−1.68 to 0.85] | |

| Between-person association with linear slopec | 0.69 | 0.69 | .32 | [−0.66 to 2.04] | |

| Model 3: Number of drinks | |||||

| Within-person, daily-level associationd | −0.07* | 0.03 | .02 | [−0.13 to −0.02] | 0.93* |

| Between-person association with interceptc | −0.06 | 1.54 | .97 | [-−3.07 to 2.96] | |

| Between-person association with linear slopec | 0.29 | 1.12 | .80 | [−1.91 to 2.49] | |

| Model 4: Craving | |||||

| Within-person, daily-level associationd | −0.13** | 0.06 | .02 | [−0.24 to −0.02] | 0.88* |

| Between-person association with interceptc | 0.09 | 0.24 | .69 | [−0.37 to 0.56] | |

| Between-person association with linear slopec | 0.33 | 0.28 | .23 | [−0.21 to 0.88] | |

| Model 5: Weekend effectse | |||||

| Within-person, daily-level associationd | −0.35*** | 0.10 | <.001 | [−0.54 to −0.15] | 0.71*** |

SASED Smartphone Alcohol and Side Effects Diary.

aUnstandardized parameter estimates shown.

bRandom slope for within-person association was estimated, so mean and variance of slope reported. Level 2 covariates were grand-mean centered; thus, the random slope can be interpreted as a weighted-average effect for a typical participant in the trial.

cBetween-person refers to person-level mean of the daily-level predictor averaged across the entire trial.

dWithin-person association modeled as fixed effect only.

eWeekend/Weekday effect varies only within-person, so it was not modeled at the between person level.

† p

< .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

For alcohol use at the daily level, days on which individuals drank more than their typical amount of alcohol corresponded with reduced likelihood of adherence to naltrexone the next day when also controlling for weekend/weekday (Table 3). Similarly, days on which craving was stronger than usual were associated with decreased next-day adherence. Between-persons, overall drinking or craving was unrelated to initial adherence and its rate of decline.

Finally, adherence was significantly less likely on weekends relative to the other days of the week (Table 3).

Mediation of Weekend Effects on Adherence

Mediation models showed that alcohol use and craving were significant mediators of the weekend effect on adherence (Fig. 2). Individuals generally drank more alcohol on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday relative to other days of the week. In turn, when they drank more alcohol, they were less likely to adhere the following day. Similarly, craving levels were generally higher on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, relative to other days of the week, which in turn predicted reduced likelihood of adherence the following day. The indirect pathway was statistically significant for alcohol (i.e., 95% confidence interval [CI] did not include 0) and marginally significant for craving (i.e., upper limit of 95% CI was equal to 0; Fig. 2). Yet, the weekend effect remained significant in both models, indicating that weekend/weekday differences in adherence were only partially mediated by within-person increases in alcohol use and craving on weekends.

Fig. 2.

Mediation models of weekend/weekday differences in daily adherence to naltrexone mediated by daily-level alcohol use and craving. Unstandardized coefficients are shown with standard errors in parentheses. The figure depicts the relationships at the within-person level of each multilevel structural equation model; analyses also controlled for between-person associations of alcohol use and craving with overall adherence levels, as well as the effects of intervention condition, gender, and change in adherence during the trial. Asymmetric confidence intervals were obtained using Prodclin. †p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine predictors of daily adherence to naltrexone assessed by MEMS among adults seeking treatment for AUDs. Adherence decreased rapidly over the course of the trial. Consistent with prior research, there were no differences in adherence levels due to alcohol dependence severity or baseline drinking [5]. Unlike prior work, there were no effects of age [5] or obsessive-compulsive drinking tendencies [6]. Women had a slower decline in adherence over time; however, adherence levels were not significantly different between men and women at the end of the study. Inconsistencies between studies in the existing literature and our own in terms of which participant characteristics predict naltrexone adherence suggest that additional research is needed to clarify which dispositional factors matter and when.

Several within-person predictors of daily adherence were identified in this study. Participants had increased medication adherence on days on which they completed their daily mobile self-assessments of alcohol use, craving, and side effects relative to days on which they did not. This suggests that the act of completing the assessments may have served as a medication reminder, even though the assessments did not concern adherence per se. This association could also be explained by instances where someone who did not want to take the medications on a given day also made the decision to not complete the daily assessment. If completing the assessments served as a medication reminder, the effect of the self-assessments could have contributed to minimal efficacy of the adherence reminders in the intervention condition, above and beyond the assessment-only condition, as originally described [17]. Data were not collected to determine how well the intervention would have performed compared with treatment as usual (i.e., no daily assessments of alcohol, craving, or side effects). This should be considered when developing future investigations of mHealth interventions on health behavior.

A novel contribution of this study was the finding that days on which individuals drank more than their typical amount of alcohol were associated with lower odds of next-day adherence to naltrexone. This effect is consistent with prior work linking alcohol use to poorer overall adherence to ART [22–24]. This investigation also adds to the literature by demonstrating a role of alcohol use in daily naltrexone adherence, and more specifically that within-person daily variation in alcohol use (rather than mere characterization as a heavier drinker) was proximally predictive of nonadherence. A similar relation was supported for alcohol craving, with stronger craving days predicting reduced next-day adherence.

Associations between alcohol use, craving, and naltrexone adherence pose an important challenge to treatment providers given that the targeted health outcomes are the very factors undermining the treatment uptake. As a result, it is critical to integrate interventions to promote adherence following heavy drinking or strong craving episodes. Further work is needed to establish what interventions would improve adherence in this context. In light of the results from the present investigation, mHealth interventions warrant further investigation and could be tailored to prompt individuals to take naltrexone specifically on days after they have reported heavier drinking or strong craving episodes. The present findings also suggest that it may be difficult to reach individuals with mobile interventions when they need it most. Thus, alternatively, these findings argue for greater uptake of extended-release formulations of naltrexone, which is an once-a-month injectable formulation, to bypass the factors driving low adherence among problem drinkers.

Consistent with prior research concerning adherence to ART [25–27] and antidiabetic medication [28], adherence was significantly lower on weekends (i.e., Friday, Saturday, and Sunday combined) relative to other days of the week. As daily alcohol use and craving partly mediated the weekend effect on adherence, reduced weekend adherence could be partially addressed by implementing interventions that promote adherence following heavy drinking and strong craving days. Nonetheless, additional intervention methods to improve weekend adherence are warranted as the weekend effect on daily adherence remained significant after accounting for the mediating roles of alcohol use and craving.

Further research to elucidate factors contributing to reduced weekend adherence could benefit intervention developers. For instance, determining the extent to which weekend nonadherence is nonintentional (e.g., schedule-related challenges) or intentional (e.g., taking a break from medication) could inform intervention targets. Intentional weekend nonadherence could occur in anticipation of weekend drinking to prevent naltrexone from mitigating the rewarding effects of alcohol (e.g., wanting to “catch a buzz” or “get drunk”). To our knowledge, this concept has not been systematically investigated in the naltrexone adherence literature. Intentionally skipping doses of medication in anticipation of drinking has been identified among patients taking ART [52, 53] and has been referred to as “weekending” [53]. The extent to which this occurs in the context of naltrexone treatment would certainly undermine the effectiveness of naltrexone in reducing alcohol use.

The current investigation has several strengths and weaknesses. MEMS provided an objective measure of adherence; however, having a biomarker of adherence would increase confidence that medication was actually consumed. Furthermore, an important methodological strength is the daily assessment of many of the constructs of interest, including craving, drinking, and side effects. It is possible that there are other unmeasured explanatory variables at the daily level, such as motivation to abstain from drinking, which could account for some of the supported associations. Furthermore, information about the timing of drinking episodes and peak craving was not collected. It is impossible to interpret same-day relations between adherence and drinking because it is unknown precisely when drinking occurred in relation to medication taking. As a result, we focused specifically on prospective predictors of adherence. To reduce participant burden, we simplified daily assessments of side effects to reflect presence/absence. Contrary to our expectations, daily reporting of medication side effects was not associated with daily adherence. Individuals who experienced more side effects than usual on a given day did not change their adherence, and individuals who averaged more side effects over time relative to others did not exhibit differential adherence rates. It is possible that by not evaluating severity of each side effect, our measure was not sensitive enough to detect more granular associations between side effects and adherence.

This investigation provides preliminary evidence of the importance of addressing daily processes to improve medication adherence in addiction treatment and adds to a growing literature on the effects of alcohol use and weekends on medication adherence more broadly. Nonadherence tended to occur following days of heavy drinking and strong craving, and on the weekend (Friday, Saturday, and Sunday). These associations suggest several points in the treatment process that would be critical to assist patients in taking naltrexone. Findings suggest that it is important to develop strategies to help patients continue or resume taking medications after heavier drinking episodes so as to prevent further regression from treatment goals. mHealth interventions warrant additional research as a means to address these daily processes as a means of improving medication adherence.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Small Business Innovation Research contract no. HHSN275201000011C from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) to Talaria, Inc. (Principal Investigator, S.A.S.). This research was also supported by postdoctoral fellowships awarded to S.S.D. and J.D.W. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canada Research Chairs Program (C.S.H.). NIAAA had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study. Talaria, Inc., has closed and donated its technology to the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington. The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests. Neither the funders nor the owners of Talaria, Inc., had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Authors Sarah S. Dermody, Jeffery D. Wardell, Susan A. Stoner, and Christian S. Hendershot declare that they have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval Research involved Human Participants, and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee and Quorum Review. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was collected from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014; 311(18): 1889–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: When are these medications most helpful?Addiction. 2013; 108(2): 275–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rösner S, Hackl‐Herrwerth A, Leucht S, et al. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. The Cochrane Library. 2010; Art. No.: CD001867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swift R, Oslin DW, Alexander M, Forman R. Adherence monitoring in naltrexone pharmacotherapy trials: A systematic review. j Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011; 72(6): 1012–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baros AM, Latham PK, Moak DH, Voronin K, Anton RF. What role does measuring medication compliance play in evaluating the efficacy of naltrexone?Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007; 31(4): 596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cramer J, Rosenheck R, Kirk G, Krol W, Krystal J; VA Naltrexone Study Group 425 Medication compliance feedback and monitoring in a clinical trial: Predictors and outcomes. Value Health. 2003; 6(5): 566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA; Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. n Engl j Med. 2001; 345(24): 1734–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chick J, Anton R, Checinski K, et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000; 35(6): 587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: An intervention for medical practitioners to enhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. j Addict Dis. 2000; 19(1): 71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of naltrexone in the context of different levels of psychosocial intervention. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008; 32(7): 1299–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zweben A, Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, et al. Relationship between medication adherence and treatment outcomes: The COMBINE study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008; 32(9): 1661–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hendershot CS, Wardell JD, Samokhvalov AV, Rehm J. Effects of naltrexone on alcohol self-administration and craving: Meta-analysis of human laboratory studies. Addict Biol. 2017; 22(6): 1515–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Johnson A, Holoyda BJ, Garofalo R. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. j Med Internet Res. 2012; 14(2): e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): A randomised trial. Lancet. 2010; 376(9755): 1838–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, Green BB, Ginsburg AS. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: A systematic review. j Med Internet Res. 2015; 17(2): e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fletcher BR, Hartmann-Boyce J, Hinton L, McManus RJ. The effect of self-monitoring of blood pressure on medication adherence and lifestyle factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am j Hypertens. 2015; 28(10): 1209–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stoner SA, Arenella PB, Hendershot CS. Randomized controlled trial of a mobile phone intervention for improving adherence to naltrexone for alcohol use disorders. PLoS One. 2015; 10(4): e0124613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miranda R, Ray L, Blanchard A, et al. Effects of naltrexone on adolescent alcohol cue reactivity and sensitivity: An initial randomized trial. Addict Biol. 2014; 19(5): 941–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Penning R, McKinney A, Verster JC. Alcohol hangover symptoms and their contribution to the overall hangover severity. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012; 47(3): 248–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stephens R, Ling J, Heffernan TM, Heather N, Jones K. A review of the literature on the cognitive effects of alcohol hangover. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008; 43(2): 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marlatt GA, Gordon JR.. Determinants of Relapse: Implications for the Maintenance of Behavior Change. New York, NY: Alcoholism & Drug Abuse Institute; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010; 112(3): 178–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chibanda D, Benjamin L, Weiss HA, Abas M. Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in people living with HIV/AIDS in low- and middle-income countries. j Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014; 67 (suppl 1): S54–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: Review and meta-analysis. j Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009; 52(2): 180–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bachhuber M, Bilker WB, Wang H, Chapman J, Gross R. Is antiretroviral therapy adherence substantially worse on weekends than weekdays?j Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010; 54(1): 109–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Boni RB, Zheng L, Rosenkranz SL, et al. Binge drinking is associated with differences in weekday and weekend adherence in HIV-infected individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016; 159: 174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levine AJ, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, et al. Variations in patterns of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence. aids Behav. 2005; 9(3): 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vervloet M, Spreeuwenberg P, Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, de Bakker DH, van Dijk L. Lazy sunday afternoons: The negative impact of interruptions in patients’ daily routine on adherence to oral antidiabetic medication. A multilevel analysis of electronic monitoring data. Eur j Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 69(8): 1599–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lau-Barraco C, Braitman AL, Stamates AL, Linden-Carmichael AN. A latent profile analysis of drinking patterns among nonstudent emerging adults. Addict Behav. 2016; 62: 14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ammassari A, Murri R, Pezzotti P, et al. ; AdICONA Study Group Self-reported symptoms and medication side effects influence adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with HIV infection. j Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001; 28(5): 445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002; 105(3): 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Magura S, Mateu PF, Rosenblum A, Matusow H, Fong C. Risk factors for medication non-adherence among psychiatric patients with substance misuse histories. Ment Health Subst Use. 2014; 7(4): 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bouza C, Angeles M, Magro A, Muñoz A, Amate JM. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: A systematic review. Addiction. 2004; 99(7): 811–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Croop RS, Faulkner EB, Labriola DF. The safety profile of naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism. Results from a multicenter usage study. The Naltrexone Usage Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997; 54(12): 1130–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stoner SA, Hendershot CS. A randomized trial evaluating an mHealth system to monitor and enhance adherence to pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012; 7: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome: Measurement and validation. j Abnorm Psychol. 1982; 91(3): 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, et al. Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between internet-based assessment and traditional methods?Psychol Addict Behav. 2002; 16(1): 56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kahler CW, Strong DR, Hayaki J, Ramsey SE, Brown RA. An item response analysis of the Alcohol Dependence Scale in treatment-seeking alcoholics. j Stud Alcohol. 2003; 64(1): 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P. The Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale: A self-rated instrument for the quantification of thoughts about alcohol and drinking behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995; 19(1): 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roberts JS, Anton RF, Latham PK, Moak DH. Factor structure and predictive validity of the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999; 23(9): 1484–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sobell LC, Sobell MB.. Timeline Follow-Back. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. New York, NY: Springer; 1992: 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Columbus M, eds. Assessing Alcohol Problems. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuseand Alcoholism; 1995: 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kavanagh DJ, Statham DJ, Feeney GF, et al. Measurement of alcohol craving. Addict Behav. 2013; 38(2): 1572–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lukasiewicz M, Benyamina A, Reynaud M, Falissard B. An in vivo study of the relationship between craving and reaction time during alcohol detoxification using the ecological momentary assessment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005; 29(12): 2135–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Muthén LK, Muthén BO.. Mplus User’s Guide.7th ed Lost Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Asparouhov T, Muthen B. Constructing covariates in multilevel regression. Mplus Web Notes. 2006; 11: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hallgren KA, Witkiewitz K. Missing data in alcohol clinical trials: a comparison of methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013; 37(12): 2152–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Satorra A, Bentler PM. Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika. 2010; 75(2): 243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol Methods. 2010; 15(3): 209–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: program PRODCLIN. Behav Res Methods. 2007; 39(3): 384–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McNeish D. Multilevel mediation with small samples: A cautionary note on the multilevel structural equation modeling framework. Struct Eqn Modeling. 2017; 24: 609–625. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sankar A, Wunderlich T, Neufeld S, Luborsky M. Sero-positive African Americans’ beliefs about alcohol and their impact on anti-retroviral adherence. aids Behav. 2007; 11(2): 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kenya S, Chida N, Jones J, Alvarez G, Symes S, Kobetz E. Weekending in PLWH: Alcohol use and ART adherence, a pilot study. aids Behav. 2013; 17(1): 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]