Abstract

Controllable synthesis of single atom catalysts (SACs) with high loading remains challenging due to the aggregation tendency of metal atoms as the surface coverage increases. Here we report the synthesis of graphene supported cobalt SACs (Co1/G) with a tuneable high loading by atomic layer deposition. Ozone treatment of the graphene support not only eliminates the undesirable ligands of the pre-deposited metal precursors, but also regenerates active sites for the precise tuning of the density of Co atoms. The Co1/G SACs also demonstrate exceptional activity and high selectivity for the hydrogenation of nitroarenes to produce azoxy aromatic compounds, attributable to the formation of a coordinatively unsaturated and positively charged catalytically active center (Co–O–C) arising from the proximal-atom induced partial depletion of the 3d Co orbitals. Our findings pave the way for the precise engineering of the metal loading in a variety of SACs for superior catalytic activities.

Controllable synthesis of single atom catalysts with sufficiently high metal loading remains challenging due to the tendency of agglomeration. Here the authors synthesize a series of stable atomically dispersed cobalt atoms on graphene with high Co loadings via the regeneration of active sites by atomic layer deposition.

Introduction

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) have emerged as a new frontier in the field of heterogeneous catalysis due to their remarkable catalytic performances and maximized atom utilization1–21. For SACs to be practicably applicable, a sufficiently high loading of atomically-dispersed atoms on an appropriate support is required. Unfortunately, isolated metal atoms are thermodynamically unstable due to their high surface energy and thus prone to agglomeration at an increased loading during the synthetic process or the subsequent treatment. Common strategies to tackle this issue include reducing the metal loading to an extremely low level1,3,9,22 and enhancing metal-support interactions for a strong anchoring of the isolated metal atoms13,23–25. In respect of the former strategy, the loading of the majority of SACs synthesized by wet-chemistry methods has been kept below 1% to prevent the formation of metal nanoparticles1,4,11,22,26,27. For instance, aggregation of Pt atoms dispersed on α-MoC surface and mesoporous zeolite substrates occurred once the loading of precious metal catalyst was increased to 0.2 and 0.5%, respectively11,26. In the latter strategy which involves a judicious choice of supports, the loading of Pd single atoms can be increased up to 1.5% on modified TiO2 nanosheets28. In addition, a high loading of SACs has been achieved using a wet-impregnation25,29 or high temperature pyrolysis method30. In both methods however, it was challenging to control the loading of metal atoms on the support surface for optimizing the catalytic performance. Despite considerable progress in recent years, controllable synthesis of stable SACs with sufficiently high loading for high performance catalysis remains a major roadblock towards its practical applications.

On the one hand, a strong interaction between anchored metal atoms and neighboring support atoms is essential for achieving stable high-metal-loading SACs25,28. On the other hand, the metal-support interaction results in modification of the electronic properties of anchored metal atoms, which in turn alters the activity and selectivity of SACs25,31. It is therefore of importance to probe the local coordination environment of single metal atoms and their electronic coupling with support atoms in close proximity. Such a study offers a unique opportunity to further optimize the catalytic performance of SACs, which however, remains largely unexplored.

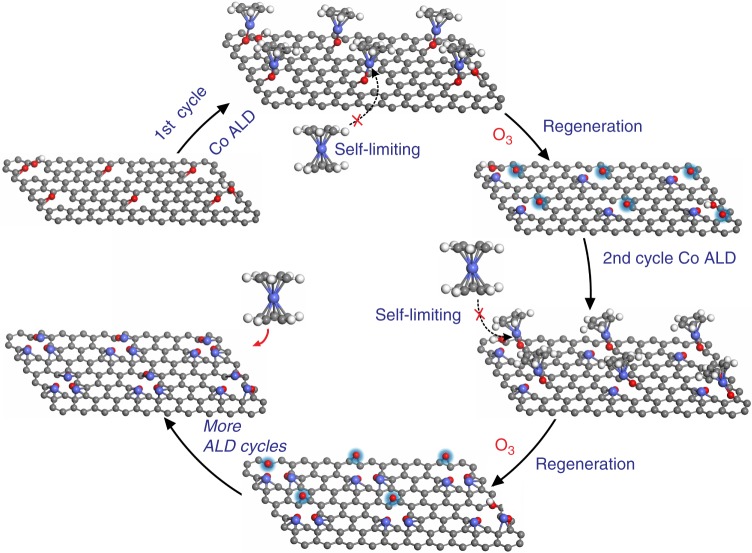

To this end, we have devised a reliable method via the atomic layer deposition (ALD) technique for the preparation of stable high loading Co1/G SACs, which also allows the precise tuning of the density of isolated Co atoms on the graphene support. In contrast to solution-phase deposition, self-limiting surface reactions (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figure 1) of ALD ensure that each Co precursor molecule is anchored on a single active site of the graphene support5,12,15,17. Interestingly, the active sites on graphene can be re-generated by ozone treatment in the second pulse of each ALD cycle, allowing for the loading of another batch of Co single atoms. As a result, the loading of Co1 single atoms can be precisely tuned by controlling the number of Co ALD cycles as illustrated in the Fig. 1. In the selective hydrogenation of nitrobenzene, all the Co1/G SACs prepared show outstanding activity and remarkable selectivity to azoxy compounds. The mechanistic studies show that the electronic coupling of Co atoms with adjacent oxygen atoms results in more positively charged Co1 catalytic center, which helps to reduce its binding strength to azoxy compounds. Such an electronic coupling between the Co atom and its neighboring oxygen atoms prevents the full hydrogenation of nitroarenes, leading to a remarkably high selectivity towards the partially hydrogenated product.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of Co1/G SACs with tuneable loadings. The first cycle of Co ALD by an alternative exposure of the support to CoCp2 vapor and O3 gas at 150 °C; the second cycle of Co ALD on Co1/G to deposit another batch of Co atoms on the active sites created by O3 treatment at 150 °C in the previous Co ALD cycle; more cycles of Co ALD results in a high loading of Co1 SACs. The balls in gray, white, red, and blue represent carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and cobalt, respectively

Results and discussion

Synthesis of Co1/G SACs

In our study, reduced graphene oxide was selected as the support for the preparation of Co1/G SACs due to the following figures of merit: (i) chemically derived graphene offers an ideal low-cost platform for the anchoring of individual Co ALD precursors to the oxygen-decorated carbon sites;32 (ii) the density of anchoring sites on graphene can be tuned by controlling the pretreatment conditions32–34. Under typical oxidation conditions, the basal plane of graphene can be decorated with diverse oxygen functional groups including hydroxyl, epoxy, phenolic, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups32. However, only specific oxygen-containing functional groups on the graphene surface are expected to act as nucleation sites to react with the metal precursors used in the ALD. Hence, it is desirable to achieve homogenous oxidation of graphene to create a high density of identical anchor sites in order to optimize the loading density of Co1 single atoms. The exposure of graphene to ozone (O3) at an elevated temperature is most likely to produce uniform epoxy functional groups34,35, which are anticipated to be active anchor sites for Co(C5H5)2 precursors (CoCp2). Furthermore, the remaining ligands of the deposited metal precursors are often removed through a combustion reaction using O3 in the second pulse of each ALD cycle36. Hence, we expect the ozonation of a graphene support at elevated temperature to achieve two outcomes, namely allowing us to burn off organic ligands and to recreate desirable anchor sites for the subsequent Co ALD cycles, which would offer an effective method for tuning the metal loading of SACs.

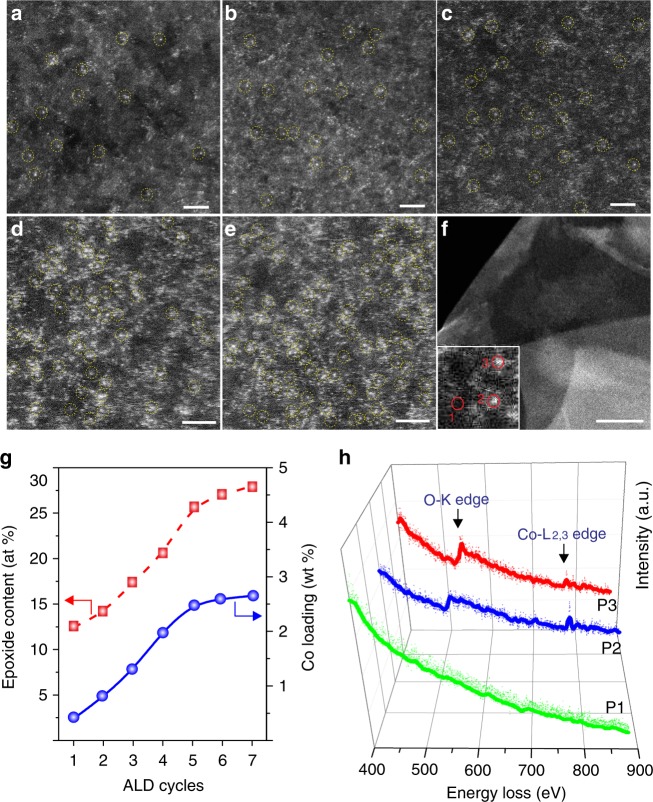

To test the above hypothesis, we performed X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) measurements to investigate the evolution of the amount of oxygen-containing groups on graphene exposed to O3 at 150 °C (Supplementary Figure 2). It was found that ozonation of graphene at 150 °C creates predominantly epoxy groups as confirmed by the observation of a strong O1s peak at 532.08 eV, consistent with a previous report33. The increase in the amount of epoxy groups on the graphene support is approximately linear in the first five cycles of ozone pretreatment but tends to plateau as the number of ozone pretreatment cycles further increases (Fig. 2g). After gaining a better understanding of the ozonation of graphene, we carried out the first cycle of Co ALD on thermally reduced graphene oxide by exposing the support to CoCp2 vapor as illustrated in Fig. 1. Subsequently, molecular O3 was injected into the chamber to remove the ligand and to simultaneously recreate new active sites for the loading of another batch of Co atoms in the subsequent cycle of ALD. By repeating this stepwise deposition, the loading density of Co1/G catalysts can be precisely tuned by controlling the number of Co ALD cycles. Through this method, we managed to synthesize a series of Co1/G catalysts with Co loadings of 0.4, 0.8, 1.3, 2.0, and 2.5 wt% (designated as Co1/G-0.4, Co1/G-0.8, Co1/G-1.3, Co1/G-2.0, and Co1/G-2.5) by performing 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 cycles of Co ALD respectively.

Fig. 2.

Structural characterization and identification of Co1/G SACs. Aberration-corrected STEM-ADF images of Co1/G-0.4 (a), Co1/G-0.8 (b), Co1/G-1.3 (c), Co1/G-2.0 (d), and Co1/G-2.5 (e). Scale bars, 2 nm (a–e), 50 nm (f). Co1 single atoms are highlighted by yellow dashed circles. f The STEM-ADF image of Co1/G-2.5 catalysts at low magnification. g The evolution of epoxy content in graphene and Co loadings of Co1/G SACs catalysts as a function of the number of ALD cycles. h EEL spectra of O K-edge and Co L2,3-edge acquired in the bare graphene region (position 1 as marked in the inset of f) and the isolated Co atom sites (Position 2, 3 as marked in the inset of f)

Characterization of Co1/G SACs

State-of-the-art aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy – annular dark field (STEM-ADF) measurements were initially conducted to gain a detailed understanding of the morphologies of the as-prepared Co1/G SACs. The employed acceleration voltage is 60 kV, where the lower voltage significantly reduces the cross section of Co atoms dissociation or clustering events. The large-field of view STEM-ADF images of the as-prepared Co1/G SACs revealed the absence of larger clusters for all the samples prepared within the five cycles of Co ALD as shown in Fig. 1f and Supplementary Figure 3. Compared to the bare graphene (Supplementary Figure 4), atomic resolution STEM-ADF images revealed that Co atoms in Co1/G-0.4 (Fig. 2a) and Co1/G-0.8 (Fig. 2b) prepared in the first and second cycle of Co ALD respectively are atomically dispersed and well-separated on graphene without aggregation into particles or other Co species (Supplementary Figure 5a-5d and Supplementary Figure 6). The presence of isolated Co atoms was further confirmed by EDS-mapping (Supplementary Figure 5e-g). Interestingly, an increase in the Co loading generated by performing more cycles of Co ALD continued to produce well-dispersed Co single atoms rather than large Co clusters and nanoparticles (Fig. 2c–e, Supplementary Figure 7–9). To our delight, the Co particles or clusters were barely present on graphene even at high loading densities of 2 wt% and 2.5 wt% (Fig. 2d, e, Supplementary Figure 8, 9). We also found that the density of Co single atoms loaded on graphene is closely correlated to the amount of epoxy groups present on the support (Fig. 2g), which further supports the idea that the epoxy groups act as anchor sites for the Co precursors as illustrated in Fig. 1. In order to probe the local chemical environment of Co atoms, we have conducted spatial-dependent electron energy loss spectra (EELS) measurements off (1) and on (2, 3) Co atom sites as marked in the inset of Fig. 2f. In contrast to the featureless curves (green) taken in the bare graphene region, the EELS acquired on single Co atom sites reveal the coexistence of Co L2,3 edge and O K edge related peaks, suggesting that the anchoring of isolated Co atoms in graphene involves oxygen atoms. Furthermore, examination of the Co L2,3 edge fine structure shows sharp white features with an L3/L2 ratio of ~5, suggesting an oxidation state which is lower than +2 valence state37. Such an atomic insight not only provides compelling evidence for the presence of Co–O bonds at the catalytically active sites but also rationalises the proposed atomic structures of Co1/G SACs as will be discussed in more details later.

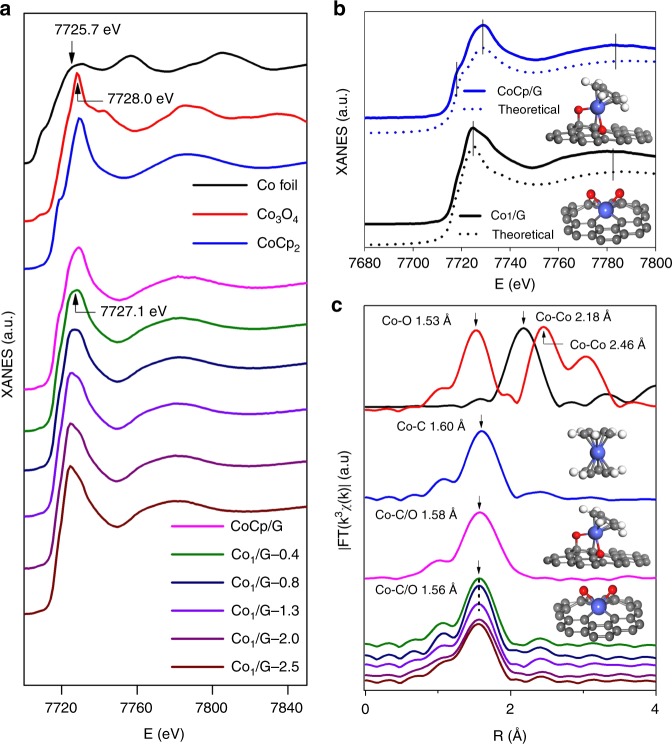

The XAFS is a state-of-the-art method to probe the local information of the adsorbing atoms. In our experiment, it was used to investigate the structural and electronic states of the Co1/G SACs with different loadings. As shown in Fig. 3a, the XANES white line peaks of the Co1/G SACs samples with different loadings are centered at 7727.1 eV, between that of the Co foil (7725.7 eV) and Co3O4 (7728.0 eV), consistent with the Co1/G SACs as-prepared being in the oxidized state rather than the metallic state. Additional structural information can also be explicitly inferred from the extended X-ray adsorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra at the Co K-edge (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Figure 1, 0). Further, the Fourier transform (FT) k3χ(k) spectrum of the CoCp2 molecule exhibits a dominant peak centered at 1.60 Å assignable to the Co–C bonds of the CoCp2 precursors. In contrast, the EXAFS spectrum (labeled as CoCp/G) acquired on the graphene support after exposure to CoCp2 vapor at 150 °C shows one main peak at 1.58 Å. This suggests the existence of a shorter bond which may result from the chemisorption of CoCp2 precursors to graphene. As illustrated in Fig. 1, it is naturally expected that CoCp2 precursors react with the epoxy groups on graphene by removing one of Cp ligands. Hence, the resultant Co atoms will be bonded to one remaining Cp ligand and oxygen atoms on graphene, giving rise to a shorter Co–C/O bond length as compared with that of Co–C bonds in CoCp2 molecules. In addition, the FT spectra for a series of Co1/G SACs show that the first shell peaks undergo a further downshift to 1.56 Å as compared to that of CoCp/G, indicating that the bonding of Co on the basal plane of graphene is further strengthened due to the Co atoms forming new chemical bonds with graphene after the complete removal of organic ligands via the O3 treatment. These observations are consistent with the bonding information extracted from the EXAFS fitting results (Supplementary Table 1). It is also worth noting that the major peaks at 2.18 Å and 2.48 Å of the FT spectra acquired on Co foil and Co3O4 respectively are absent in the corresponding spectra of all the Co1/G SACs, which further confirms that Co atoms remained well dispersed on the graphene support at the high loading of 2.5 wt%, in line with the STEM results.

Fig. 3.

Co K-edge XAFS and EXAFS spectra of CoCp/G, Co1/G SACs. a Co K-edge XAFS spectra. b The experimental XANES curves are compared with the calculated XANES data of optimized DFT-modeled structures of Co1/G and CoCp/G (inset shows the atomic structures of the models). c Fourier transform (FT) extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of these samples with the corresponding structures (insets). The balls in gray, white, red, and blue represent carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and cobalt, respectively. The Co K-edge XAFS and EXAFS spectra of Co foil, Co3O4 and CoCp2 samples are displayed for comparison. Note: the figure legend in a also applies to c

DFT calculations

In order to determine the atomic structures of the Co1/G SACs, we performed DFT calculations in combination with a standard XAFS fitting method (Supplementary Figure 1, 2-1, 7). Based on the plausible Co ALD reaction mechanism on the defect-rich graphene support (Supplementary Figure 1, 1), it is most likely that the isolated Co atoms are anchored in vacancy related structures through bonding to oxygen species as revealed in our EELS measurements. We hence propose several possible atomic configurations of the Co1/G SACs along this line (Supplementary Figure 1, 2-1, 3), which are further optimized via DFT calculations. Our calculations reveal a stable structure consisting of CoCp bonded to the graphene support via two interfacial O atoms and one C atom for the CoCp/G sample (Supplementary Figure 1, 2a). Such a structure is expected to be generated in the first step of ALD cycle (Fig. 1), in line with previous work38. After the removal of ligand (Cp), isolated Co atoms in the Co1/G SACs can be anchored to the divacancy of graphene through bonding with two interfacial O atoms and four C atoms, forming a new structure represented by Co1–O2C4 (Supplementary Figure 1, 2b). In order to verify these two structures, we calculated their XANES (Fig. 3b) and fitted their EXAFS (Supplementary Figure 1, 5-1, 7) spectra, which show a good agreement with our experimental data acquired on CoCp/G and Co1/G SACs respectively (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Figure 1, 3-1, 7 and Supplement Table 1). In contrast, the calculated XANES spectra of other DFT-modeled structures fail to reproduce the main features of experimental curves (Supplementary Figure 1, 4). Hence, it is most likely the Co1/G SACs prepared here contains a six-coordinated structure (Co1–O2C4), wherein individual Co atoms are bonded to two interfacial O atoms and four C atoms.

Catalytic activity

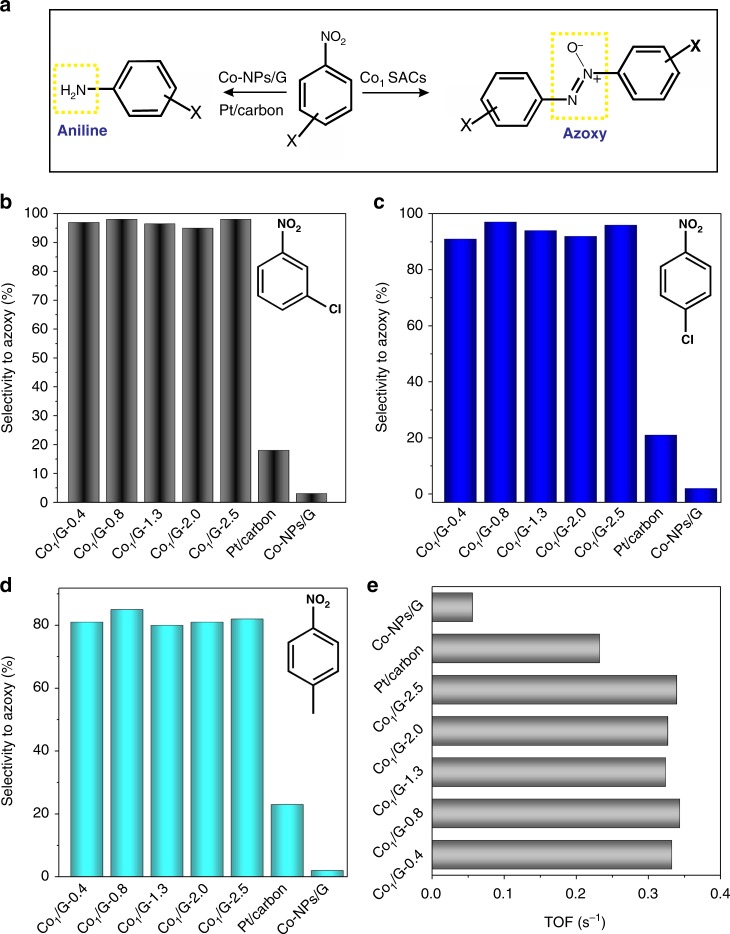

Azoxybenzene is one of the most important industrial media of the dye and pharmacy industries39,40. The catalytic selective hydrogenation of nitrobenzene has been a major method for the synthesis of azoxybenzene. Unfortunately, the catalysts employed for industrial-scale production of azoxybenzene are usually toxic41. Noble metal heterogeneous catalysts have recently emerged as promising catalysts for the synthesis of azoxybenzene42–44. However, these catalysts are not practical for the scalable synthesis of azoxybenzene due to their high cost. Here we employ the Co1/G SACs in the selective hydrogenation of a wide range of substituted nitrobenzene to produce azoxy products as illustrated in Fig. 4a. As shown in Fig. 4b, all the Co1/G SACs exhibit much higher selectivity to 3, 3’-dichlorideazoxybenzene (98%), compared to Pt/carbon (18%) and Co-NPs/G (4%) (Supplementary Figure 1, 8-1, 9). For different substituted nitrobenzene (compound 1–6) (Fig. 4c, d and Supplementary Figure 20), all the Co1/G SACs also exhibit significantly higher selectivity to azoxy compounds (~90%) compared to Pt/carbon (18~21%) and Co-NPs/G (2-3%). The major product over Pt/carbon and Co-NPs/G catalysts is aniline compound, giving rise to a low selectivity to azoxy compounds45–47. In addition, the Co nanoparticles (Supplementary Figure 2, 1) synthesized by ALD (designated as Co-NPs/G-ALD) show a low selectivity (~5%) to azoxy compounds (Supplementary Figure 22). All the azoxybenzene products were verified by their characteristic 1HNMR and 13CNMR spectra (Supplementary Figure 23-36)48. Importantly, the Co1/G SACs with different loadings show negligible variations in the selectivity towards all azoxy compounds (Fig. 4b–d), presumably due to a relatively uniform dispersion of isolated Co atoms for all the Co1/G SACs catalysts.

Fig. 4.

Catalytic selectivity to azoxy products of various Co1/G SACs catalysts. a Schematic illustration of the hydrogenation of nitroarenes using different catalysts. Histograms of the selectivity to azoxy products for the hydrogenation of 1-chloride-3-nitrobenzene (b), 1-chloride-4-nitrobenzene (c), and 1-methyl-4-nitrobenzene (d) at ~100% conversion of nitroarenes by using different Co1/G SACs including Co1/G-0.4, Co1/G-0.8, Co1/G-1.3, Co1/G-2.0, Co1/G-2.5, Co-NPs/G, and Pt/carbon. e Turnover frequency (TOF) of the different catalysts tested in the selective hydrogenation of nitrobenzene

The excellent atomic dispersion of all the Co1/G SACs with different loadings indeed results in a similar turnover frequency (TOF) of 0.33 s−1, which is 6 times higher than that of Co nanoparticles (0.05 s−1) as shown in Fig. 4e. In addition, Co1/G SACs synthesized exhibit higher catalytic activity and selectivity in the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene as compared to non-noble metal catalysts reported in the previous work (Supplementary Table 2). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4e, the TOF of Co1/G SACs is even higher than that of Pt/carbon (0.23 s−1), which proves their superior catalytic performance comparable to that of precious catalysts. To our delight, Co1/G SACs with a high loading of 2.5 wt% also exhibit a high durability in the selective hydrogenation of nitroarenes as revealed in the recyclability test (Supplementary Figure 37).

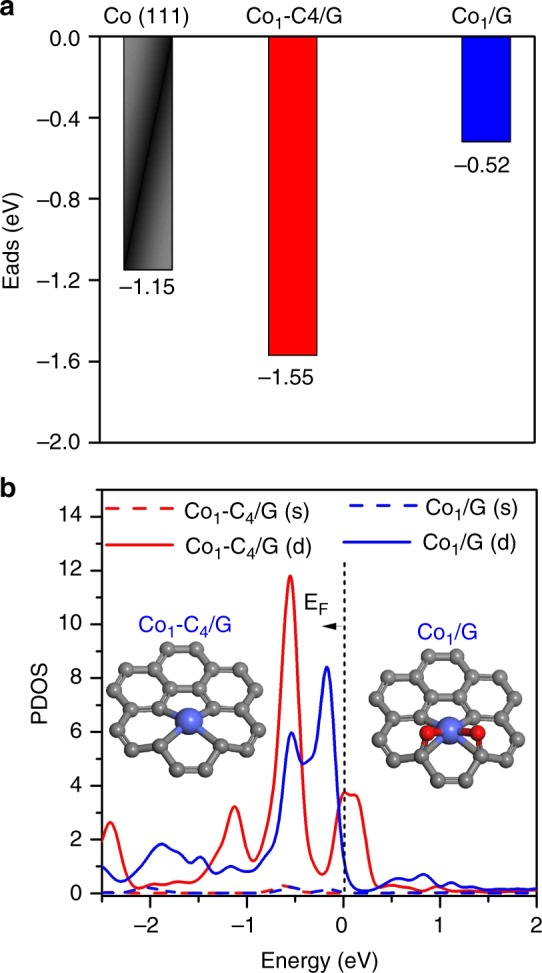

The hydrogenation of nitrobenzene is expected to occur through multiple steps, involving the generation of different reaction intermediates (Supplementary Figure 38)49,50. The adsorption energy of the intermediate compounds on catalytic surface is one of the key factors that determine the selectivity to certain target products51. In our system, we observed that azoxy compound is the major product when Co1/G SACs is applied. This indicates that the reaction stops at step 4 (Supplementary Figure 38) is prohibited, preventing the further hydrogenation of azoxy compound to aniline. Such a reasoning is also reported in the previous work52. Therefore, we performed DFT calculations of the adsorption energies of azoxybenzene molecules on Co (111), Co1/G SACs and catalytic centers consisting of isolated Co atoms coordinated to four carbon atoms in a graphene divacancy (labeled as Co1-C4/G). It’s worth mentioning here that the catalytic activity of graphene-based metal SACs has been predicted in previous theoretical studies53–55, but catalytic role of atoms proximal to single metal atom remains largely unexplored. Here, we found that holding Co and oxygen atoms in the close proximity is the key that allows the reaction to proceed with extremely high selectivity in the partial hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to azoxybenzene. Such an excellent catalytic performance can be attributed to the different binding nature of the reactants adsorbed at different catalytic sites. As shown in the Fig. 5a, the dispersion-corrected DFT (DFT-D2) calculations revealed that azoxybenzene shows a stand-up adsorption geometry on Co (111) with a large adsorption energy of −1.15 eV. In the case of the Co1–C4/G, the azoxybenzene exhibits a flat adsorption geometry over the Co1–C4 site with an even larger adsorption energy of −1.55 eV (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the azoxybenzene binds to the Co1−O2C4 site of Co1/G SACs weakly with a small adsorption energy of 0.52 eV. In addition, the separation between azoxybenzene and the Co catalytic center becomes larger for the weak adsorption case (Co1/G SACs) (Supplementary Figure 39). Furthermore, it is observed that the charge redistribution at the interface in the cases of Co (111) and Co1–C4/G is more significant than that of azoxybenzene adsorbed on the Co–O2C4 site of Co1/G SACs (Supplementary Figure 40a-c). The weak adsorption of azoxy compounds over Co1/G SACs might be insufficient to break the N–O bond of azoxybenzene for further hydrogenation, giving rise to a high selectivity to azoxybenzene (Supplementary Figure 40d)49,52.

Fig. 5.

Theoretical simulations of the catalytic origins. a Adsorption energies for the azoxybenzene on Co (111) facet, Co1–C4/G and Co1/G SACs. b The partial density of state (PDOS) projected on the Co 4 s and 3d orbitals of Co1-C4/G and Co1/G. The balls in gray, red, and blue represent carbon, oxygen, and cobalt, respectively

To gain more insights into the catalytic role of proximal atoms in the SACs, we also calculated the projected density of states (PDOS) of the Co atom to d and s orbitals for both Co1/G and Co1–C4/G (a hypothetic structure without proximal oxygen atom for a comparison). As shown in Fig. 5b, the PDOS of Co 3d orbitals around Fermi energy (EF) is dramatically different in the two examined structures while the difference for PDOS of Co 4 s orbitals is much less significant. The PDOS of Co 3d of Co1–C4/G exhibit a noticeable peak at EF contributed by the partially filled d orbitals. In contrast, the presence of oxygen atoms proximal to Co1 in Co1/G SACs pushes these partially filled d orbitals above EF, resulting in a lower PDOS at EF and thus a more positively charged Co atom. Consistently, Bader charge transfer analysis56 also reveals that each Co atom in Co1/G SACs loses more electrons (~0.8 electrons) to the surrounding O and C atoms compared to Co atoms in Co1–C4/G (lose 0.65 electrons to the surrounding atoms). A more positively charged Co1–O2C4 active center disfavors the adsorption of electron-deficient azoxybenzene on the Co1–O2C4 of Co1/G SACs for the further hydrogenation to azobenzene, which in turn leads to a higher selectivity towards azoxybenzene (Supplementary Figure 40d)51,57. The excellent catalytic performance of Co1/G SACs discovered in our study attests to their great potential in a wide range of selective hydrogenation reactions.

In conclusion, we have developed a stepwise approach to fabricate a series of Co1/G SACs with high and precisely tunable loadings. Our results reveal that the ozone treatment of a graphene support at mild ALD conditions not only burns off metal ligands, but also recreates active sites for the subsequent anchoring of another batch of Co atoms. This unique approach allows us to precisely tune the density of the supported Co atoms from 0.4% up to 2.5% without formation of any Co nanoparticle or clusters. As compared to conventional Co nanoparticles and precious Pt /carbon catalysts, all the Co1/G SACs exhibit remarkably high selectivity towards azoxy compounds in the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene aromatics. This can be attributed to the electronic coupling between Co atoms and adjacent oxygen atoms that results in a positively charged catalytic center. Consequently, the adsorption of electron deficient azoxy compounds is weaker and thus the full hydrogenation of nitroarenes is prevented. Our findings have opened up an unprecedented avenue to precisely control the loading of single metal atoms in a wide range of SACs for industrially important chemical transformations.

Methods

Materials

All the chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and were used as received without further purification. These includes Bis (cyclopentadienyl) cobalt (CoCp2, 98%), Co(NO3)2·6H2O (98%, trace metals basis), the Pt/carbon catalyst, sodium borohydride (99.99%, trace metals basis) and all the subsitituted nitrobenzenes . Few-layer graphene oxide and pristine graphene nanosheet (99.5%) were purchased from Nanjing XFNANO Materials Tech Co. Ltd. and Chengdu Organic Chemicals Co. Ltd., Chinese Academy of Sciences respectively.

Synthesis of Co1/G SACs

The synthesis of Co1 SACs was performed in a viscous ALD flow reactor (Plasma-assisted ALD system, Wuxi MNT Micro and Nanotech Co., Ltd, China) by alternatively exposing thermally-reduced graphene oxide to CoCp2 precursor and O3 at 150 °C. Ultrahigh purity N2 (99.99%) was used as carrier gas with a flow rate of 50 mL/min. The Co precursor was heated at 100 °C to generate a high enough vapor pressure. The reactor and reactor inlets were held at 150 °C and 120 °C respectively to avoid any precursor condensation. An in-situ thermal reduction of as-received graphene oxide support was conducted at 300 °C for 5 min before performing Co ALD. The timing sequence was 100, 120, 150, and 120 seconds for the CoCp2 exposure, N2 purge, O3 exposure and N2 purge, respectively. Conducting Co ALD with 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 cycles allows for the synthesis of Co1/G-0.4, Co1/G-0.8, Co1/G-1.3, Co1/G-2.0, and Co1/G-2.5, respectively.

Synthesis of Co-NPs/G

The Co-NPs/G was synthesized using the previous method58. In brief, 100 mg of the graphene oxide was dispersed in 15 mL of ethanol with sonication. Meanwhile, 10 mg of Co(NO3)2·6H2O (1 mmol) was added into 15 mL of ultrapure water. After that, NaOH solution (6 M) was added into as-prepared Co(NO3)2 solution. Co(OH)2 precipitated was filtrated and washed multiple times using ultrapure water and ethanol. The Co(OH)2 solid was then dispersed into ethanol with sonication, and gradually added into graphene oxide dispersion followed by a continuous stirring for 1 h. In order to keep the pH at 11, 6 M NaOH solution was used during the synthesis. Then, 1 ml of N2H4·H2O was added and stirred for another 30 min. The obtained mixture was put into Teflon-lined stainless autoclave at 180 °C for 12 h. The sample was dried at 60 °C after filtration and washing. Before used in the catalytic reaction, as-prepared samples were calcined at 150 °C in air, and reduced under a flow of 10% H2/Ar gas at 150 °C.

The characterization of as-prepared catalysts

The Co loadings in all the samples were measured by an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES); therein all samples were dissolved in hot fresh aqua regia. XPS measurements were carried out in a custom-designed ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) system with a base pressure better than 2 × 10–10 mbar. Al Ka (hν = 1486.7 eV) was used as the excitation sources for XPS. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV 300 (300 MHz) and Bruker AV500 (500 MHz) spectrometer. Chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm), and the residual solvent peak was used as an internal reference: 1H (chloroform δ 7.27), 13C (chloroform δ 77.0).

STEM-ADF characterization and image simulation: STEM-ADF imaging was carried out in an aberration-corrected JEOL ARM-200F system equipped with a cold field emission gun and an ASCOR probe corrector at 60 kV. The images were collected with a half-angle range from ~85 to 280 mrad, and the convergence semiangle was set at ~30 mrad. The imaging dose rate for single frame imaging is estimated as 8 × 105 e/nm2·s with a total dose of 1.6 × 107 e/nm2. The dwell time for STEM-ADF image is set as 20 us/pixel. The EELS 2D maps were taken by Gatan Quantum ER Spectrometer with a spectrum pixel time of 2 s.

The X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) measurements of Co K-edge were carried out at the XAFCA beamline of the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS)59. The storage ring of SSLS operated at 700 MeV with beam current of 250 mA. A Si (111) double-crystal monochromator was applied to filter the X-ray beam. Co foils were used for the energy calibration, and all samples were measured under transmission mode at room temperature. The EXAFS oscillations χ(k) were extracted and analyzed using the Demeter software package60.

DFT calculations

The first-principles calculations are performed with density functional theory (DFT) by utilizing the Vienna ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP)61. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerh (PBE) format62,63 and the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method64 are employed in all calculations. A plane wave basis with a cut-off energy of 450 eV along with spin polarization and 4 × 4 × 1 k-sampling in Brillouin zone are used for all calculations. The convergence criterion for structural relaxations is set to 0.01 eV/Å. Effects of Van der Waals force (through DFT + D2)65 are also considered. Defective graphene is defined with an 8 × 8 unit cell with a divacancy consisting of two missing adjacent C atoms (Figure S5). The Co (111) surface is described with a 4 × 4 unit cell with 5 atomic layers. The Co atoms of the bottom three layers are kept fixed in the relaxation process. 18 Å of a vacuum layer in perpendicular direction is included into supercells to avoid unphysical interactions between neighboring unit cells.

XANES simulations

The XANES spectra of Co K edges of all the structures predicted by DFT were modeled using a finite difference method implemented by FDMNES program66. For the FDMNES calculation, the Schrödinger equation is solved with a free shape of potential, which avoids using the muffin-tin approximation and thus better reproduce the theoretical XANES spectrum. For all the calculated XANESs, the final states are calculated inside a sphere with a size of 8 Å. The energy step at the Fermi level is 0.2 eV.

Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene and its derivatives

0.1 mmol of substrates, 1.4 × 10−3 mmol of catalyst, 2 mmol sodium borohydride, 8 mL of Tetrahydrofuran (THF) and 2 ml of ultrapure water were mixed in a round-bottom flask to carry out the reaction. Then the reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C for one hour. The as-obtained products were analyzed by GC-MS (7890 A GC system, 5975 C inert MSD with Triple-Axis Detector, Agilent Technologies).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

J. Lu acknowledges the support from NUS start-up grant (R-143-000-621-133) and Tier 1 (R-143-000-637-112) and MOE Tier 2 grant (R-143-000-A06-112). W. Chen acknowledges NSFC grant 91645102. C. Su acknowledges NNSFC (51502174) and Shenzhen Peacock Plan (Grant No. 827-000113, KQTD2016053112042971). C. Zhang acknowledges the support from Singapore National Research Foundation (NRF-CRP13-2014-03 and NRF-CRP16-2015-02). H. Yan appreciates the funding support from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M610541).

Author contributions

J.L. supervised the project. H.Y. and J.L. conceived and designed the experiment. H.Y. prepared the catalysts and performed the activity test with the supervision of C.S. and J.L.; X.Z. performed the STEM-ADF and EELS characterization with the supervision of S.J.P.; N.G. performed the theoretical calculation under the supervision of C.Z.; Y.D. and S.X. helped to perform the XAFS measurement. Z.L. helped to establish the ALD system under the supervision of W.C.; R.G. performed the XPS measurements under the supervision of W.C.; C.C. helped to perform the TEM characterization. Z.C., W.L., C.Y., and J.Li. assisted in the activity test. H.Y., C.S., C.Z., and J.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and contributed to the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Huan Yan, Xiaoxu Zhao, Na Guo.

Change history

9/5/2018

This Article was originally published without the accompanying Peer Review File. This file is now available in the HTML version of the Article; the PDF was correct from the time of publication.

Contributor Information

Chenliang Su, Email: chmsuc@szu.edu.cn.

Chun Zhang, Email: phyzc@nus.edu.sg.

Jiong Lu, Email: chmluj@nus.edu.sg.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-05754-9.

References

- 1.Qiao BT, et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt-1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:634–641. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyriakou G, et al. Isolated metal atom geometries as a strategy for selective heterogeneous hydrogenations. Science. 2012;335:1209–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.1215864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin J, et al. Remarkable performance of Ir-1/FeOx single-atom catalyst in water gas shift reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15314–15317. doi: 10.1021/ja408574m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moses-DeBusk M, et al. CO oxidation on supported single Pt atoms: experimental and ab initio density functional studies of CO interaction with Pt atom on theta-Al2O3(010) Surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12634–12645. doi: 10.1021/ja401847c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun SH, et al. Single-atom catalysis using Pt/graphene achieved through atomic layer deposition. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1775. doi: 10.1038/srep01775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang M, Allard LF, Flytzani-Stephanopoulos M. Atomically dispersed Au-(OH)(x) species bound on titania catalyze the low-temperature water-gas shift reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3768–3771. doi: 10.1021/ja312646d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang XF, et al. Single-atom catalysts: a new frontier in heterogeneous catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1740–1748. doi: 10.1021/ar300361m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo X, et al. Direct, nonoxidative conversion of methane to ethylene, aromatics, and hydrogen. Science. 2014;344:616–619. doi: 10.1126/science.1253150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei H, et al. FeOx-supported platinum single-atom and pseudo-single-atom catalysts for chemoselective hydrogenation of functionalized nitroarenes. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5634. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang M, et al. Catalytically active Au-O (OH) x-species stabilized by alkali ions on zeolites and mesoporous oxides. Science. 2014;346:1498–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1260526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding K, et al. Identification of active sites in CO oxidation and water-gas shift over supported Pt catalysts. Science. 2015;350:189–192. doi: 10.1126/science.aac6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan H, et al. Single-atom Pd1/graphene catalyst achieved by atomic layer deposition: remarkable performance in selective hydrogenation of 1, 3-butadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:10484–10487. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones J, et al. Thermally stable single-atom platinum-on-ceria catalysts via atom trapping. Science. 2016;353:150–154. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang R, et al. Hydroformylation of olefins by a rhodium single‐atom catalyst with activity comparable to RhCl (PPh3) 3. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;128:16288–16292. doi: 10.1002/ange.201607885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng N, et al. Platinum single-atom and cluster catalysis of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13638. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung HT, et al. Direct atomic-level insight into the active sites of a high-performance PGM-free ORR catalyst. Science. 2017;357:479–484. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan H, et al. Bottom-up precise synthesis of stable platinum dimers on graphene. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1070. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01259-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo J, et al. Ultrasmall tungsten carbide catalysts stabilized in graphitic layers for high-performance oxygen reduction reaction. Nano Energy. 2016;28:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.08.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, et al. Platinum-modulated cobalt nanocatalysts for low-temperature aqueous-phase Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4149–4158. doi: 10.1021/ja400771a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, et al. Catalytically active single-atom niobium in graphitic layers. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1924. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, et al. An oxygen reduction electrocatalyst based on carbon nanotube-graphene complexes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7:394–400. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vile G, et al. A stable single-site palladium catalyst for hydrogenations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:11265–11269. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang SR, et al. WGS catalysis and in situ studies of CoO1-x, PtCon/Co3O4, and PtmCom ‘/CoO1-x nanorod catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8283–8293. doi: 10.1021/ja401967y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S, et al. Catalysis on singly dispersed bimetallic sites. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7938. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi CH, et al. Tuning selectivity of electrochemical reactions by atomically dispersed platinum catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10922. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin L, et al. Low-temperature hydrogen production from water and methanol using Pt/α-MoC catalysts. Nature. 2017;544:80–83. doi: 10.1038/nature21672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang B, et al. Stabilizing a platinum1 single‐atom catalyst on supported phosphomolybdic acid without compromising hydrogenation activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:8319–8323. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu PX, et al. Photochemical route for synthesizing atomically dispersed palladium catalysts. Science. 2016;352:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu G, et al. MoS2 monolayer catalyst doped with isolated Co atoms for the hydrodeoxygenation reaction. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:810–816. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu W, et al. Single-atom dispersed Co–N–C catalyst: structure identification and performance for hydrogenative coupling of nitroarenes. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:5758–5764. doi: 10.1039/C6SC02105K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, et al. Uncoordinated amine groups of metal–organic frameworks to anchor single Ru sites as chemoselective catalysts toward the hydrogenation of quinoline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9419–9422. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dreyer DR, Park S, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:228–240. doi: 10.1039/B917103G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganguly A, Sharma S, Papakonstantinou P, Hamilton J. Probing the thermal deoxygenation of graphene oxide using high-resolution in situ X-ray-based spectroscopies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011;115:17009–17019. doi: 10.1021/jp203741y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mulyana Y, Uenuma M, Ishikawa Y, Uraoka Y. Reversible oxidation of graphene through ultraviolet/ozone treatment and its nonthermal reduction through ultraviolet irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:27372–27381. doi: 10.1021/jp508026g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao W, et al. Ozonated graphene oxide film as a proton‐exchange membrane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3588–3593. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chong YT, Yau EMY, Nielsch K, Bachmann J. Direct atomic layer deposition of ternary ferrites with various magnetic properties. Chem. Mater. 2010;22:6506–6508. doi: 10.1021/cm102600m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y, Feltes TE, Regalbuto JR, Meyer RJ, Klie RF. In situ electron energy loss spectroscopy study of metallic Co and Co oxides. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;108:063704. doi: 10.1063/1.3482013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao Y, et al. Atomic insight into optimizing hydrogen evolution pathway over a Co1‐N4 single‐site photocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:12191–12196. doi: 10.1002/anie.201706467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoult J. Pharmacological and biochemical actions of sulphasalazine. Drugs. 1986;32:18–26. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198600321-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waghmode SB, Sabne SM, Sivasanker S. Liquid phase oxidation of amines to azoxy compounds over ETS-10 molecular sieves. Green. Chem. 2001;3:285–288. doi: 10.1039/b105316g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nokubi T, Kindt S, Clark T, Kamimura A, Heinrich MR. Synthesis of dibenzo [c, e][1, 2] diazocines—a new group of eight-membered cyclic azo compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:316–320. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.11.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corma A, Serna P. Chemoselective hydrogenation of nitro compounds with supported gold catalysts. Science. 2006;313:332–334. doi: 10.1126/science.1128383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, et al. Gold‐catalyzed direct hydrogenative coupling of nitroarenes to synthesize aromatic azo compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:7624–7628. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li HQ, et al. Deoxygenative coupling of nitroarenes for the synthesis of aromatic azo compounds with CO using supported gold catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:11217–11220. doi: 10.1039/C5CC03134F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao F, Ikushima Y, Arai M. Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene with supported platinum catalysts in supercritical carbon dioxide: effects of pressure, solvent, and metal particle size. J. Catal. 2004;224:479–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2004.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun Z, et al. The solvent-free selective hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline: an unexpected catalytic activity of ultrafine Pt nanoparticles deposited on carbon nanotubes. Green. Chem. 2010;12:1007–1011. doi: 10.1039/c002391d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu R, Xie T, Zhao Y, Li Y. Quasi-homogeneous catalytic hydrogenation over monodisperse nickel and cobalt nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:055602. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/5/055602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwu JR, Das AR, Yang CW, Huang JJ, Hsu MH. 1, 2-Eliminations in a novel reductive coupling of nitroarenes to give azoxy arenes by sodium bis (trimethylsilyl) amide. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3211–3214. doi: 10.1021/ol050924x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu H, Ke X, Yang X, Sarina S, Liu H. Reduction of nitroaromatic compounds on supported gold nanoparticles by visible and ultraviolet light. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:9851–9855. doi: 10.1002/ange.201003908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu L, et al. Highly efficient synthesis of aromatic azos catalyzed by unsupported ultra-thin Pt nanowires. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:3445–3447. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30281k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen G, et al. Interfacial electronic effects control the reaction selectivity of platinum catalysts. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:564. doi: 10.1038/nmat4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao Q, Liu Z, Wang F, Sarina S, Zhu H. Tuning the reduction power of visible-light photocatalysts of gold nanoparticles for selective reduction of nitroaromatics to azoxy-compounds—Tailoring the catalyst support. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017;209:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu YH, Zhou M, Zhang C, Feng YP. Metal-embedded graphene: a possible catalyst with high activity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:20156–20160. doi: 10.1021/jp908829m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou M, Lu YH, Cai YQ, Zhang C, Feng YP. Adsorption of gas molecules on transition metal embedded graphene: a search forhigh-performance graphene-based catalysts and gas sensors. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:385502. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/38/385502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo N, Xi Y, Liu S, Zhang C. Greatly enhancing catalytic activity of graphene by doping the underlying metal substrate. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:srep12058. doi: 10.1038/srep12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanville E, Kenny SD, Smith R, Henkelman G. Improved grid‐based algorithm for Bader charge allocation. J. Comput. Chem. 2007;28:899–908. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ke X, et al. Tuning the reduction power of supported gold nanoparticle photocatalysts for selective reductions by manipulating the wavelength of visible light irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:3509–3511. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17977f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu T, Xue J, Zhang X, He G, Chen H. Ultrafine cobalt nanoparticles supported on reduced graphene oxide: efficient catalyst for fast reduction of hexavalent chromium at room temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;402:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.01.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Du Y, et al. XAFCA: a new XAFS beamline for catalysis research. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2015;22:839–843. doi: 10.1107/S1600577515002854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ravel B, Newville M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2005;12:537–541. doi: 10.1107/S0909049505012719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kresse G, Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:558. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54:11169. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perdew JP, et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B. 1992;46:6671. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.46.6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blöchl PE. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;50:17953. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA‐type density functional constructed with a long‐range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;27:1787–1799. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bunău, O., & Joly, Y. Self-consistent aspects of x-ray absorption calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 345501 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.