Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) / acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a highly complex process which can be triggered by both non-infectious (sterile) and infectious stimuli. Inflammatory lung responses are one of the key features in the pathogenesis of this devastating syndrome. How ALI/ARDS associated inflammation develops remains incompletely understood, particularly after exposure to sterile stimuli. Emerging evidence suggests that extracellular vesicles (EVs) regulate intercellular communication and inflammatory responses in various diseases. In this study, we characterized the generation and function of pulmonary EVs in the setting of ALI/ARDS, induced by sterile stimuli (oxidative stress or acid aspiration) and infection (LPS/Gram negative bacteria) in mice. EVs detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were markedly increased after exposure of animals to both types of stimuli. After sterile stimuli, alveolar type-І epithelial (ATI) cells were the main source of the BALF EVs. In contrast, infectious stimuli-induced BALF EVs were mainly derived from alveolar macrophages (AMs). Functionally, BALF EVs generated in both the non-infectious and infectious ALI models promoted the recruitment of macrophages in vivo mouse models. Furthermore, BALF EVs differentially regulated AM production of cytokines and inflammatory mediators, as well as TLR expression in AMs in vivo. Regardless of their origin, BALF EVs contributed significantly to the development of lung inflammation in both the “sterile” and “infectious” ALI. Collectively, our results provide novel insights into the mechanisms by which EVs regulate the development of lung inflammation in response to diverse stimuli, potentially providing novel therapeutic and diagnostic targets for ALI/ARDS.

Keywords: extracellular vesicle (EV), acute lung injury (ALI), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), alveolar macrophage, lung epithelial cell

Introduction

Accumulating data have demonstrated that extracellular vesicles (EV)s regulate diverse cellular and biological processes related to human diseases, via facilitating intercellular cross-talk (1). EV-like molecules were initially described by Chargaff and West in 1946, as platelet-derived particles found in plasma (2). Subsequently, EVs have been isolated from most cell types and biological fluids including bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (3, 4). The discovery of EVs in BALF offers a novel insight into lung physiology and the pathogenesis of human lung diseases.

EVs are highly heterogeneous, varying in size and composition and amounts generated; this is largely based on their origin and the environmental stimuli that induce their production. Accumulation of EVs in tissues is a dynamic process, constantly changing, depending on the activation state of cells producing them, and the tissue microenvironment, after exposure to noxious stimuli. The International Society of Extracellular Vesicles has defined three main subgroups of EVs based on size, composition and mechanisms of formation (5, 6); these are exosomes (Exos), microvesicles (MV)s, and apoptotic bodies (AB)s. Exos are the smallest subgroup of EVs measuring approximately 30 – 100 nm in diameter. Exos generation is closely related and dynamically associated with endosomes/lysosomes, the trans-Golgi network (TGN), and multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (7, 8). Exos are released from cells after MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane (8). The second group of EVs are MVs which protrude from plasma membranes (9). Their biogenesis involves the outward budding and expulsion of plasma membrane from the cell surface resulting in the formation of small vesicles with sizes ranging from 100 nm to 1 μm (9). MVs are generated via the dynamic interplay between phospholipid redistribution and cytoskeletal protein contraction. This process, which is energy dependent and requires ATP, is triggered by translocation of phosphatidylserine to the outer-membrane leaflet through amino-phospholipid translocase activity (10, 11). In contrast to Exos and MVs, which are released from healthy cells and play an important role in cell communication, the third group of EVs, ABs, are formed during the process of apoptosis;. ABs are the largest of the EVs, roughly at 1000 – 2000 nm in diameter, comparable in size to platelets (12).

MVs and Exos carry a variety of components, including RNAs and proteins. Some of the proteins have been used as markers for EVs. Since these proteins are also expressed on cells generating EVs, they provide information about their origin (13). Common marker proteins include: tetraspanins such as CD9, CD63, CD81 and CD82; 14-3-3 proteins, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, and cytosolic proteins such as heat shock proteins; HSPs, Tsg101 and the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT-3) binding protein Alix (7). However, these protein are not specific to either MVs or Exos. Moreover, no single marker can uniquely identify a subgroup of EVs.

In humans acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS) can develop as a consequence of exposure to infectious pathogens or to non-infectious noxious stimuli. Whereas non-infectious or “sterile” pathology is modeled experimentally by hypoxia, acid-inhalation, and ventilator-induced baro-trauma (14), infection-induced ALI/ARDS is induced by bacteria or viruses, or various components of these agents, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or lipoteichoic acid (LTA). Earlier studies suggested an association between ALI and the generation of “microparticles” (MPs) derived from platelets, neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, red blood cells, endothelial and epithelial cells (15). Although initially termed “MPs”, it is now recognized that these are, in fact, MVs. However, the function of these MVs remains undetermined. Numerous cell types reside within the lung, including macrophages and epithelial cells, which play an important role in host defense against inhaled environmental toxins and microorganisms. How these cells communicate is unknown. We speculate that MVs play a key role in this activity, and the present studies are designed to test this hypothesis using different models of ALI. We found that EVs are released into BALF in both sterile and infectious mouse models of ALI; however, there were significant differences in the function of the EVs generated in the different ALI models. These studies provide novel insights on the role of EVs in lung disease pathogenesis in vivo. This may lead to the development of novel therapeutics for the treatment of ALI-induced by sterile or infectious stimuli.

Material and Methods

Materials.

PE-conjugated anti-pan cytokeratin antibody (ab52460) and anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa OMP antibody [B11] (ab35835) were purchased from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). PE-conjugated anti-Ly-6G antibody was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Anti-CD31, anti-CD68, anti-CD9 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Animals.

Wild type C57BL/6 mice (6 to 8 weeks of age) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All animal protocols were approved by the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). All experimental protocols and methods were approved by Boston University, and were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Bacteria culture.

Pseudomonas pneumoniae (P. pneumoniae) PA103 were cultured overnight in Luria-Bertani medium at 37 °C in a rotator at 250 RPM. For Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) (ATCC® 6303™) culture, after overnight incubation on 5% sheep blood agar plates (BD Biosciences), freshly grown colonies were suspended in Brain Heart Infusion Broth medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Bacterial concentrations were assessed by serial dilutions using OD600 and were diluted to final colony forming unit (CFU) concentrations as needed for each experiment.

Cell culture.

Lung epithelial E10 cells (16), and alveolar MH-S macrophages (ATCC® CRL-2019™) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) or RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air. For hyperoxia exposure, cells were exposed to 95% oxygen/5% CO2 in modular exposure chambers, as previously described (17). For bacterial infections, cells were infected with P. pneumonia or S. pneumonia, as described previously (18, 19). Briefly, cells were incubated with bacteria (106 colony forming units (CFU)) for 4 h, followed by extensive washing with PBS containing 2 % penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were then incubated with DMEM-containing 2 % penicillin-streptomycin for 24 h. The culture media was collected, centrifuged and EVs isolated from the supernatants. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford assay; residual bacteria in supernatants were analyzed by measuring OD600 after overnight incubation of the samples at 37 ˚C; none were detected.

Acute lung injury models.

For hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury (ALI), mice were exposed to 100 % oxygen in modular exposure chambers, as previously described (20). For generating acid-, lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-, and bacteria-induced ALI, hydrochloric acid (0.1 N, pH 1.5), LPS (1 μg per mouse), or live bacteria (106 colony forming units (CFU)) (21) were instilled intra-tracheally into the mouse lung, respectively. At the designated time points after administration, mice were euthanized and BALF collected. The methods are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Techniques for generation of various ALI models

| ALI models | Technique | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperoxia | 100 % oxygen exposure in modular chambers | 3 days |

| Acid | 0.1 N HCl aspiration (50 μl/mouse) | 1 day |

| LPS | 50 μl saline containing 1 μg LPS | 1 day |

| Live bacteria | 50 μl saline containing

106 CFU (Pseudomonas pneumoniae or Streptococcus pneumoniae) |

1 day |

EV isolation from BALF and cell-cultured medium.

Previously reported protocols were utilized to isolate MVs, Exos, and ABs (3, 12, 22). Briefly, BALF or cell-cultured medium were centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min to eliminate inflammatory or dead cells. The supernatant was then collected and centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min to pellet ABs (12). To isolate MVs, the AB-depleted supernatant was passed through a 0.45 μm-pore-size filter to completely remove the instilled bacteria from the samples. The filter was then washed two-times with cold PBS to completely recover the MVs, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 40 min (23, 24). The MVs obtained fell into the size range of 100–400 nm. We found that the filtration step had no effect on the amount of recovered MVs or on their size distribution (data not shown). The resulting supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h to pellet Exos (25). The same EV isolation procedure was used for all ALI models. Isolated vesicles were re-suspended in cold PBS and analyzed using dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument (Brookhaven 90plus Nano-particle Sizer), NanoSight (Malvern), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The purity of the isolated EVs were confirmed by western blotting with antibodies against EV markers (CD63 and TSG101) and DAMP proteins (HMGB1 and S100A4), which were not detectable in the purified EVs (suppl. Fig. 1A).

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA).

To determine the size and concentration of EVs NTA was performed at the Nanomedicines Characterization Core Facility (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC). Briefly, Isolated EV samples were water-bath sonicated to help dispel aggregates and diluted to a concentration between 1×108 − 5×108 particles/mL in filtered PBS, in a final volume of 1 ml. The samples were then analyzed using NanoSight NS500 (NanoSight, Malvern Instruments, UK) to capture particles in Brownian motion. The hydrodynamic diameters were calculated using the Stokes-Einstein equation. The 100 nm standard particles and the diluent PBS alone were used for reference. Three independent experiments were conducted, and each sample was analyzed 3–4 times to obtain average value. Camera level and threshold are set as high and low respectively as needed to see all particles in a sample without creating noise. We used the same NTA settings for all the samples (camera type: SCMOS, camera level: 16 and detection threshold: 5).

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis of BALF-EVs was performed as described previously with minor modifications (25). Isolated EVs were coupled to equal amounts (10 μl) of aldehyde/sulfate latex beads (Thermo Scientific) for 2 h, and the EV-coated beads were blocked with 4% BSA for 1 h. The bead-bound EVs were then permeabilized and fixed for 5 min with 0.2% Triton X-100 and 2% formaldehyde, followed by incubation with designated antibodies. For detection of lung epithelial EVs, anti-pan cytokeratin, anti-PDPN, and anti-SPC antibodies (26) were used. For detection of alveolar macrophage EVs, anti-CD68 antibody (27) was used. For detection of endothelial and PMN-derived EVs, anti-CD31 and anti-Ly-6G antibody were used, respectively. Based on the negative control (non-coated beads), positive EV-beads particles were counted in each sample. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences), and the data analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc., San Carlos, CA).

Differential inflammatory cell counts in BALF.

Cell counting for alveolar macrophages and neutrophils in mouse BALF was conducted as described previously (28). For cytospin preparations, cell suspension was cytocentrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min using a Shandon Cytospin 4 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Slides were air-dried and stained with Hema 3™ Fixative and Solutions (PROTOCOL™). Differential cell counts were evaluated under a light microscope.

ELISA.

Mouse BALF was collected 24 h after EV instillation and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min to get rid of inflammatory cells. TNF, IL1β, IL6, IL10, IL21 and MIP2 levels in the BALFs were then analyzed using DuoSet® ELISA Development Systems (R&D system), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

Mouse mTOR Signaling PCR Array.

BALF inflammatory cells were isolated from the EV-instilled mice (n = 4 per group) and incubated on cell culture plates for 20 min to allow adhesion of alveolar macrophages (29). Total RNA was then isolated from the adhered alveolar macrophages using MiRNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen), and cDNAs generated using Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mouse mTOR signaling profiles were then analyzed using the RT² Profiler PCR Array System (Qiagen).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNAs were purified from the isolated BALF macrophages using MiRNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen). Purified RNA concentration was measured using the NanoDrop Lite Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), followed by reverse transcription to generate cDNAs. SYBR green-based real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed to detect specific mRNAs. For relative expression levels of mRNAs, beta-actin level was used as reference housekeeping gene. The sequences of primers were shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sequence of primers used in real-time quantitative PCR

| Name | Forward primer (5’ to 3’) | Reverse primer (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|---|

| TLR2 | GCAAACGCTGTTCTGCTCAG | AGGCGTCTCCCTCTATTGTATT |

| TLR4 | ATGGCATGGCTTACACCACC | GAGGCCAATTTTGTCTCCACA |

| TLR6 | TGAGCCAAGACAGAAAACCCA | GGGACATGAGTAAGGTTCCTGTT |

| TLR8 | GGCACA ACTCCCTTGTGA | TTCATTTGGGTGCTGTTGTTTG |

| TLR9 | CCGCAAGACTCTATTTGTGCTGG | TGTCCCTAGTCAGGGCTGTACTCAG |

| TNFα | GACGTGGAACTGGCAGAAGAG | TTGGTGGTTTGTGAGTGTGAG |

| IL1β | GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT | ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT |

| IL6 | GTGACAACCACGGCCTTCCCTACT | GGTAGCTATGGTACTCCA |

| IL10 | GCTCTTACTGACTGGCATGAG | CGCAGCTCTAGGAGCATGTG |

| Myd88 | TCATGTTCTCCATACCCTTGGT | AAACTGCGAGTGGGGTCAG |

| CD80 | CTGGGAAAAACCCCCAGAAG | TGACAACGATGACGACGACTG |

Statistical analysis.

For all experiments, the exact n values and statistical significances were shown in the corresponding figure and figure legends. Representative data from identical results are shown. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired two-tailed Student’s T-test and one-way ANOVA. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and ### P < 0.001).

Results

EVs are differentially induced and detected in BALF, in response to sterile or infectious stimuli.

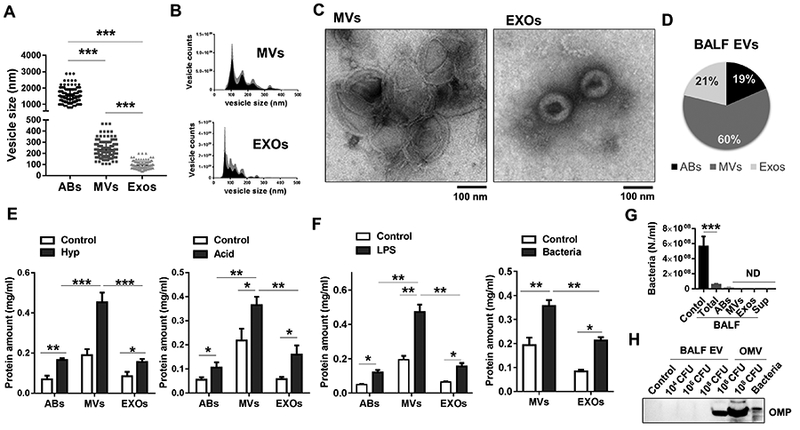

Both sterile and infectious stimuli-induced ALI models have been established in the past decades (14). We selected four well-established ALI mouse models to investigate EV generation as detailed in Table 1. Hyperoxia (oxidative stress) and acid exposure represent “sterile” or “non-infectious” stimuli-induced lung injury, while LPS and live-P. pneumoniae instillation reflect the “infectious” lung injury model (Table 1). We first isolated the three types of EVs (AB, MV, and Exos) from mouse BALF using sequential centrifugation and size-filtration, as described previously (3, 30, 31). Sizes and morphology of the EVs were initially analyzed using dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Fig 1A), Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) (Fig. 1B) and TEM (Fig 1C). The size ranges of the isolated ABs, MVs and Exos were 1000 – 3000 nm, 150 – 500 nm, and 50 – 200 nm respectively (Fig. 1A-C). EV amount was also determined using EV proteins as shown in Figure 1D. Approximately 60% of BALF EVs fell into the range of MVs, 21% were Exos and approximate 19% were ABs. Interestingly, the generation of BALF EVs was significantly upregulated in both non-infectious (Fig. 1E) and infectious ALI models (Fig. 1F). Moreover, MVs were the most robustly induced type of EVs in BALF obtained from both the sterile stimuli (hyperoxia or acid) and infectious stimuli (LPS or live Gram negative (G-) bacteria, P. pneumoniae) models (Fig. 1E-F). Given that bacteria also release outer membrane vesicles (OMV) which are in the same size range with Exos (32), we next determined whether the BALF EVs isolated after P. pneumoniae contain any bacterial OMVs. Previous reports showed a rapid clearance of bacteria from the lung (33, 34). For example, live bacteria remaining in the lung at 4 h after bacterial instillation is about 7.3 % (S. pneumoniae) and 13 % (P. pneumoniae) (33). Therefore, to prevent mixing with OMVs, we isolated the EVs at 24 h after bacterial instillation from the BALF. To further determine whether the isolated BALF EVs were originated from host cells, we first confirmed a significant reduction of the live-bacteria in the BALF (Fig. 1G). Additionally, neither bacteria nor bacterial outer membrane protein (OMP) was detected in the purified EVs (MVs + Exos) (Fig. 1G-H).

Figure 1. Generation of BALF-EVs from non-infectious and infectious stimuli-induced ALI models.

(A-D) Three subpopulations of EVs, including apoptotic bodies (ABs), microvesicles (MVs), and exosomes (Exos) were isolated from mouse BALF. The vesicle size and morphology were analyzed using DLS (A), NTA (B), and TEM (C). Pie graphs indicates the average percentages of each type of EV proteins (D) (n = 3 mice per group). (E-F) Three types of EVs were isolated from mouse BALF after sterile stimuli exposure (3 days hyperoxia and 1 day acid) (E) or infectious stimuli (1 day, LPS and P. pneumoniae) (F), followed by measuring protein concentrations of the isolated EVs. (G-F) BALFs were collected from P. pneumoniae-exposed mice, followed by sequential isolation of the indicated EVs. The bacteria growth was measured using OD600 nm (G). Bacteria outer membrane protein (OMP) were determined using western blotting (H). The same number of live-bacteria were used as positive controls. (mean ± SD, n = 3–4 mice per group). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001 between the groups indicated.

Determine the cellular origin of BALF EVs after sterile or infectious stimuli.

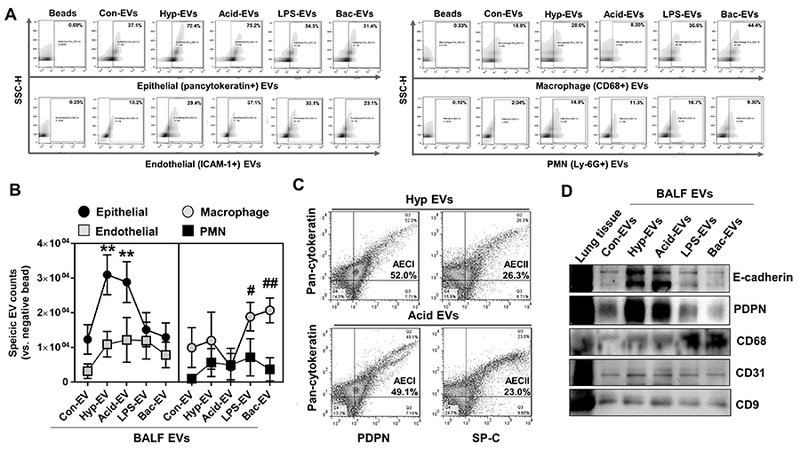

EVs often carry the same markers as their “mother” cells (13). Therefore, we used the specific cell type markers to determine the origin of BALF EVs. Since we were not focused on Abs, in all subsequent studies, BALF “EVs” refer to MVs and/or Exos. We found that the epithelial marker-positive BALF EVs dramatically increased after non-infectious stimuli (hyperoxia and acid exposure) (Fig. 2A and B). One the other hand, EVs carrying macrophage markers were highly upregulated after LPS or P. pneumoniae exposure (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, EVs carrying endothelial cell markers and PMN markers were mildly induced after stimuli (Fig. 2A and B). PDPN and SP-C are specific markers for type I alveolar epithelial cell (AECI) and type II alveolar epithelial cell (AECII), respectively (26). As shown in Figure 2C, the majority of epithelial EVs were derived from the PDPN-positive AECI cells. We confirmed these observations using western blot analysis (Fig. 2D). Both common epithelial markers (E-cadherin) and AECI (PDPN) markers were highly expressed in the EVs induced by hyperoxia and acid exposure. In contrast, the macrophage marker, CD68, was strongly increased in EVs induced by LPS or P. pneumoniae (Fig. 2D). As expected, endothelial markers (CD31) in BALF EVs were unchanged by either sterile (hyperoxia or acid) or infectious (LPS or bacteria) stimuli.

Figure 2. Determination of the origin of BALF EVs derived from non-infectious or infectious ALI models.

(A-C) BALF-EVs (containing MVs and Exos) were isolated from mice which were exposed to hyperoxia, acid, LPS, or P. pneumoniae, followed by FACS analysis of the EVs, as described in materials and methods. The populations of cell type-specific EVs in response to different stimuli are shown (A-B). PDPN (AECI marker) and SP-C (AECII marker) positive EVs were detected in the total BALF EVs derived from non-infectious ALIs (C) (mean ± SD, n = 3–4 mice per group). (D) Western blot analysis of the BALF-EVs from the ALI models using the indicated antibodies (representative data, n = 3).

BALF EVs induced by sterile or infectious stimuli promote inflammatory lung responses.

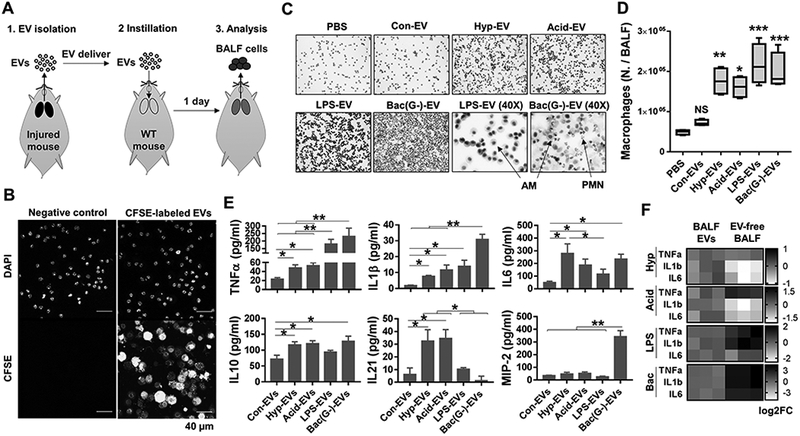

To investigate the functional significance of BALF EVs in the development of ALI, we performed the following experiments: First, we isolated BALF EVs (MVs + Exos) from mice treated with non-infectious or infectious stimuli. The BALF EVs were then instilled intra-tracheally into the lungs of healthy mice, as illustrated in Figure 3A. Efficient uptake of the exogenously delivered BALF EVs by alveolar macrophages (AMs) were confirmed (Fig. 3B). Here, we refer to BALF EVs which were obtained from the mice exposed to control, hyperoxia, acid inhalation, LPS or bacteria as Con-EV, Hyp-EV, Acid-EV, LPS-EV and Bac (G-)-EV, respectively. BALF EVs obtained from the mice exposed to either sterile or infectious stimuli strikingly triggered the recruitment of macrophages to the lung. In contrast, we did not observe macrophage recruitment in mice receiving Con-EVs from control mice (Fig. 3C and D). Furthermore, in mice treated with the Hyp-EVs, Acid-EVs, LPS-EVs or Bac (G-)-EVs, a variety of inflammatory cytokines were significantly increased in BALF (Fig. 3E). We also found that EV-containing cytokines were negligible, when compared to EV-induced cytokines in vivo, indicating that the EV-induced cytokines did not come from the instilled EVs (suppl. Fig. 1B). Notably, neutrophil infiltration and MIP2 chemokine induction, two key factors for PMN recruitment (35), were only observed after instillation of Bac (G-)-EVs, suggesting an LPS-independent pathway (Fig. 3C and E).

Figure 3. Effects of the BALF EVs derived from various ALI models on macrophage recruitment and lung inflammation.

(A-E) BALF-EVs were isolated from various ALI (hyperoxia, acid, LPS, or gram-negative P. pneumoniae) models. CFSE-labeled BALF EVs were intratracheally delivered into WT mouse lung (20 μg EVs per mouse), as illustrated in (A). One day after instillation of the EVs, the BALF cells were isolated from the recipient mouse, followed by tracking of CFSE-EVs using confocal microscopy (B) or H&E staining of isolated inflammatory cells (C). Alveolar macrophage (AM) count is shown in (D) (box and whisker plot, n = 4 mice per group). Levels of inflammatory cytokines and MIP2 chemokine in the BALFs were measured using ELISA (E) (mean ± SD, n = 3 mice per group). (F) Isolated BALF EVs or EV-free BALFs were instratracheally instilled into mouse lung. One day later, AMs were collected and inflammatory genes analyzed using qPCR (heat map, n = 3 mice per group). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001 versus control EVs or between the groups indicated.

In further studies, we compared the effects of EV-free BALF with BALF containing EVs on the development inflammatory lung responses in vivo. As shown in Figure 3F, EV-free BALF obtained from the infectious ALI models highly augmented pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression, indicating a significant contribution of BALF soluble factors (non-EV-cargo) to the development of “infectious” lung inflammation. Conversely, cytokine gene expression after treatment of mice with EV-free BALF from “sterile” ALI models were less effective in inducing gene expression than “sterile ALI”-associated BALF EVs. These data indicate that both BALF EVs and BALF soluble factors contribute to the development of lung inflammation in ALI/ARDS. However, EVs play a dominant role in the development of “sterile” inflammation while soluble factors are more predominant in the “infectious” inflammatory responses.

Non-infectious and infectious stimuli-induced BALF EVs differentially alter gene expression of inflammatory signaling molecules in AMs.

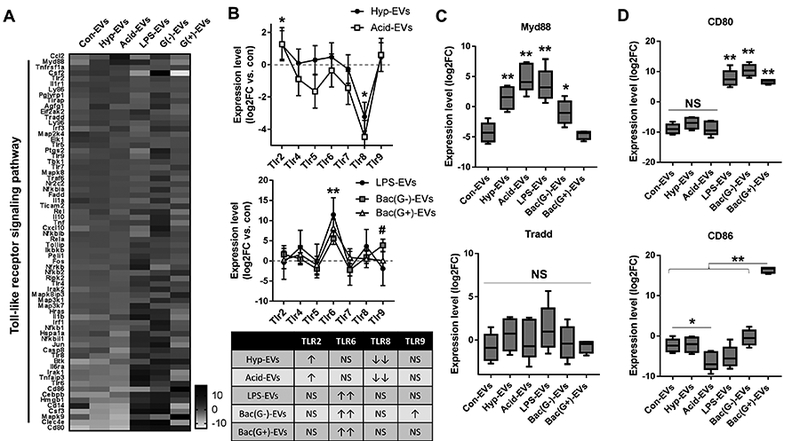

AMs are the first defense against noxious stimuli and the main immune cell type in the lung (36). We next explored inflammatory gene expression in mouse AMs after exposure to the Con-EV, Hyp-EV, Acid-EV, LPS-EV or Bac (G-)-EV. As described above, WT mice were first treated with BALF EVs isolated from non-infectious or infectious stimuli-treated mice. In these studies, each recipient mouse received BALF EVs obtained from one donor mouse, via intratracheal instillation. After 24 h, AMs were collected from recipient mice. Initially, we analyzed toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway-related genes in AMs. As shown in Figure 4A, various TLR-related genes were robustly altered in AMs after exposure to the stimulated BALF EVs in vivo. Interestingly, the patterns of gene expression were significantly different from mice which were exposed to non-infectious EVs and to infectious EVs (Fig. 4A). More importantly, the patterns of TLR expression in AMs were significantly different between the non-infectious EV (hyperoxia and acid)-treated groups and the infectious EV (LPS, P. pneumonia, and S. pneumonia)-stimulated groups (Fig 4B). Significant induction of TLR2 and reduction of TLR8 were observed in macrophages exposed to the EVs obtained after non-infectious stimuli. In contrast, all the infectious stimuli-derived EVs dramatically upregulated TLR6 in AMs in vivo (Fig 4B). We also found that EV-containing TLR2 and TLR6 were negligible and not inducible in response to noxious stimuli (suppl. Fig. 1C); they were also not detectable using qPCR in the purified EVs (suppl. Fig. 1D), indicating that the ALI EV-induced TLRs do not come directly from instilled EVs. Myd88 and Tradd are key mediators for TLR-mediated and TNFR-mediated inflammatory signaling pathways, respectively (37, 38). We found that Myd88 was highly upregulated by EVs derived from mice exposed to hyperoxia, acid, LPS, or G-negative bacteria (P. pneumonia) (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, EVs obtained from G-positive bacteria (S. pneumonia)-treated mice failed to upregulate Myd88 (Fig. 4C). Tradd expression was relatively stable after exposure to stimulated BALF EVs (Fig 4C). CD80/86 are essential for macrophage activation and communication with other adaptive immune cells (39–41). We found that CD80 was dramatically upregulated by the EVs derived after infectious stimuli (Fig. 4D), while G-positive bacteria-induced EVs only triggered CD86 gene expression in AMs in vivo (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. BALF-EVs derived from non-infectious and infectious ALIs differentially regulate inflammatory signaling pathways in recipient alveolar macrophages.

BALF-EVs, isolated from mice treated with hyperoxia, acid, LPS, P. pneumoniae (G-) or S. pneumoniae (G+) were administrated intratracheally to WT mouse lung (20 μg EVs per mouse). After 1 day, alveolar macrophages were collected and analyzed by mTOR Signaling PCR Array. Heatmap for the gene expression (A), TLR expression patterns and the summarized table (B), and expression levels of key inflammatory mediators (C-D) are shown (mean ± SD or box and whisker plot, n = 4 mice per group). * P < 0.05, and ** P < 0.01. # P < 0.05 between Bac (G-)-EVs and control.

Lung epithelial EVs or AM-EVs are responsible for the development of lung inflammation after sterile and infectious stimuli, respectively.

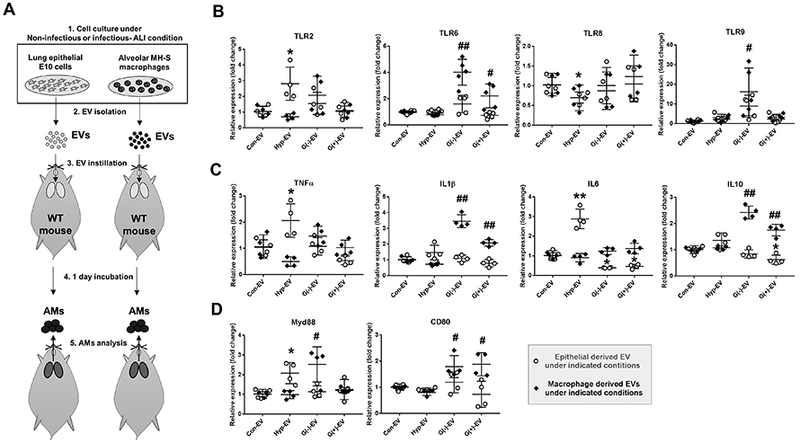

EVs were isolated from AECI and AMs after exposure of mice to non-infectious (hyperoxia) and infectious (P. pneumonia and S. pneumonia) stimuli, respectively. No bacteria were detected in the purified EVs. As shown in Figure 5A, Con-EVs, Hyp-EVs or Bac-EVs were intra-tracheally instilled into the recipient mouse lung. One day after instillation, BALF AMs were collected and analyzed for inflammatory gene expressions. Hyperoxia-induced epithelial EVs up-regulated TLR2, Myd88, TNFα, and IL6 expression in recipient AMs (Fig. 5B-D), but suppressed TLR8 (Fig. 5B) in recipient AMs. Notably, the macrophage-EVs derived after hyperoxia failed to alter inflammatory gene expression (Fig. 5B-D). TLR6, TLR9, CD80, IL1β, and IL10 were significantly upregulated in recipient AMs after exposure to AM-EVs collected after exposure of mice to infectious stimuli (Fig. 5B-D). In contrast, when treated with epithelial EVs collected after exposure to infectious stimuli, IL6 and IL10 expression was suppressed in recipient AMs (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, TLR9 and Myd88 were only up-regulated by P. pneumonia (G-) infection-induced EVs, but not by EVs induced following S. pneumonia (G+) infection (Fig. 4B, 4D, 5B and 5D).

Figure 5. Epithelial EVs and macrophage EVs differently contribute to lung inflammation in non-infectious and infectious ALI conditions.

EVs were isolated from lung alveolar epithelial type I (E10) cells and alveolar macrophages (MH-S) under non-infectious (hyperoxia exposure) and infectious (P. pneumonia or S. pneumonia administration) stimuli. The isolated EVs were intratracheally delivered into WT mouse lung (20 μg EVs per mouse). One day later, alveolar macrophages were isolated from the mouse BALF as illustrated in (A). Gene expression levels of TLRs (B), cytokines (C), and inflammatory mediators (D) were evaluated from the isolated alveolar macrophages. (mean ± SD, n = 4–5 per group). * P < 0.05, and ** P < 0.01. # P < 0.05, and ## P < 0.01.

Discussion

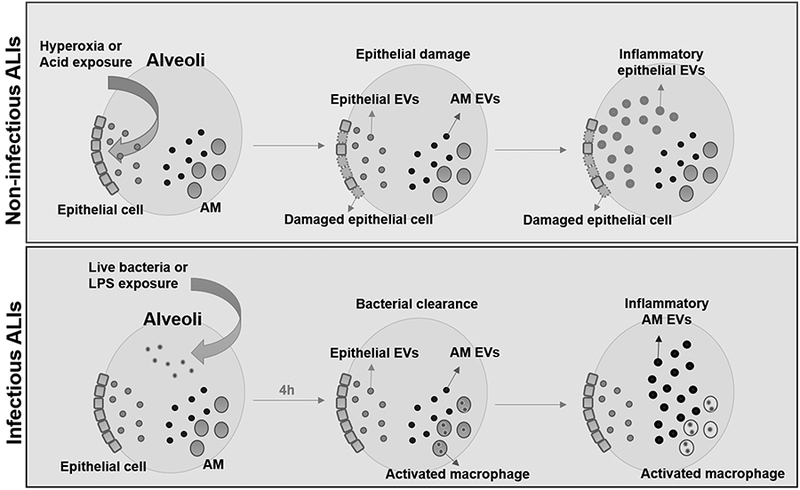

Inflammation is a key response shared by sterile and infectious stimuli-induced ARDS/ALI (14). However, the mechanisms by which lung inflammation develops remain incompletely explored, particularly in the setting of “sterile” ALI. The first significant aspect of studies described in this manuscript is that we identified two distinct pathways of intercellular communication which promote the development of lung inflammation. Thus, whereas sterile stimuli-induced EVs are mainly derived from lung epithelial cells, and uptake of epithelial EVs facilitates AM classical activation (M1), infectious stimuli mainly act on AMs stimulating the release EVs into BALF, propagating AM classical activation. This observation is consistent with previous reports showing that non-infectious stimuli first target lung epithelium (42). AMs, as the first arm of host defense in the respiratory track, play crucial roles in the elimination of inhaled bacteria, as well as the transmission and amplification of inflammatory signals (43). Following bacterial infection, AMs are activated towards a proinflammatory phenotype (classical or M1 activation) and acquire an enhanced capacity to engulf bacteria, and release inflammatory cytokines / chemokines, as well as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (44). AM-released EVs facilitate the communication between activated AMs and resting AMs, subsequently propagating the inflammatory cascade. Our observations regarding BALF EV release in the infectious models confirm that AMs indeed are the initial responders upon encountering inhaled microbes.

In our studies, we mainly focused on the transportation of EVs from lung epithelial cells to AMs (sterile model) or from AMs to adjacent AMs (infectious model). The reverse direction of EV transfer, i.e., from AMs to epithelial cells, certainly exists (45). However, in the presence of sterile stimuli, AECI cells are the first responders and the EVs released from AECI cells are increased the most robustly. Therefore, we did not address the reverse transportation of AM-derived EVs to lung epithelial cells in the presence of sterile stimuli. In the setting of infectious models, AM-derived EVs not only were transferred to adjacent AMs, but also transferred to lung epithelial cells as we previously reported (45). The adjacent AMs engulf much more AM-derived EVs, via phagocytosis or lipid raft-mediated endocytosis (46, 47). Epithelial cells may only take AM-derived EVs via the lipid raft-mediated endocytosis (47) or alternatively, receive the EV-transmitted information via surface antigen-associated signaling transduction (48).

Another important finding in this study is that in both the sterile and infectious models, the vast majority of BALF EVs fell into the range of MVs, rather than Exos or ABs. As described above, ABs, MVs and Exos have distinct mechanisms of generation (5, 6). The different routes of EV generation contributs to the different compositions of each type of EVs, subsequently leading to differential biological functions (3, 5). For example, unlike the MVs, Exos have been reported to carry minimal amounts of microRNAs (miRNAs). Less than 1 copy of miRNA / per Exo has been reported (49). In contrast to Exos, MV-containing RNA molecules, rather than MV-proteins, are the main compositions which are altered the most significantly (3). Therefore, in each disease model, identification of the precise type of EVs (i.e., MVs or Exos) is important for the development of potential therapeutic strategies targeting functional EV compositions. Our current report, for the first time, delineated the three different categories of EVs in each ALI models.

Probably the most significant observation in this study is that BALF EVs generated in either the non-infectious or infectious ALI models regulated AM-mediated inflammatory lung responses. Despite the fact that the stimuli-induced BALF EVs originated from different cells, AECI cells vs. AMs, in sterile or infectious models, the recipient cells of the stimuli-induced EVs were AMs in both types of models. This observation indicates that EVs, particularly MVs, serve as a vehicle to transport the “stress” signals from the first encounters to AMs in order to initiate or propagate inflammatory responses. Cytokines, chemokines and other well-known molecules have been shown to facilitate pro-inflammatory signal transduction (50) in the setting of ALI/ARDS (51, 52). However, many details remain unclear. For instance, how are cytokines / chemokines guided to the correct recipient cells (such as AMs)? How do AMs maintain concentrations of cytokines/chemokines during their journey from the first cells they encounter to recipient cells? Our studies provide novel insights into these questions. EVs potentially serve as a carrier or vehicle to transport signaling molecules; they also maintain the necessary concentration and structure of the signaling molecules, as well as protect EV cargo from enzymatic degradation. In previous studies showed that EV-containing miRNAs are essential in promoting lung inflammation in various models of ALI (3, 30). miRNAs are small, non-coding RNA molecules (21–23nt) involved in transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression (53). We demonstrated that EV-containing miR-17, 221, and 320a are upregulated in ALI, and stimulate the macrophage recruitment, inflammatory signaling, cytokine production and MMP-9 secretion in recipient macrophages (3, 30). The present studies demonstrate that soluble factors (non-EV-shuttling molecules) likewise contribute to inflammatory lung responses during the development of ALI. Therefore, both BALF EVs and BALF soluble factors are most likely key to the pathogenesis of dysregulated lung inflammation in ALI/ARDS.

The present studies also delineated differences of EV-mediated signal transduction in the process of classic macrophage activation. In recipient AMs, we found that TLR2, IL6, TNFα, and Myd88 are significantly upregulated by sterile stimuli-induced BALF EVs. Similar results were obtained in macrophages after treatment with stimuli-induced lung epithelial EVs. On the other hand, infectious stimuli-induced BALF EVs and AM-EVs are responsible for the induction of TLR6, IL1β, IL10, and CD80 in the recipient AMs. Interestingly, TLR9 and Myd88 are only upregulated by EVs obtained after G-bacterial infection, but not by EVs induced by G+ bacteria. These results confirmed the involvement of TLR pathways in EV-mediated macrophage activation, however, this occurs by different TLR receptors and signaling cascades. Both TLR2 and TLR6 are important receptors for NF-κB-mediated inflammation in various lung diseases (54). Whereas expression of TLR2 is important for activation of AMs in non-infectious models (55), TLR6 expression is essential for recognition and discrimination of various bacterial lipoproteins (56, 57). Taken together, our observations suggest that lung epithelial EV-mediated TLR2 upregulation and macrophage EV-mediated TLR6 induction play central roles in the pathogenesis of lung inflammation in the setting of “sterile” and “infectious” ALI, respectively. Additionally, TLR9 is only induced by G-bacteria-induced EVs and is LPS-independent (fig 4B). CD80 and CD86 belong to the B7 family and act as macrophage activators (40, 41). In our studies, CD80 and CD86 were differentially regulated by G-bacteria-induced EVs and G+ bacteria-induced EVs, supporting the complexity of EV-mediated signaling pathways.

One of the potential concerns in this report is that in the setting of bacterial infections, BALF EVs contain, not only EVs derived from host cells, but also bacteria-generated outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). The size of OMVs is approximately the same as the Exos (32). In our studies, we used ultra-centrifugation and filtration (0.45 μm pore size) to isolate MVs and Exos. We confirmed the sizes of EVs using DLS and NTA, as well as EM. To further analyze the purity of BALF EVs, we evaluated the expression of bacterial OMV marker (bacterial OMP) in the BALF EVs. Bacterial OMP was not detectable in the purified BALF EVs after bacteria instillation (up to 108 CFU), suggesting that OMVs do not exist or are undetectable in our purified BALF EVs.

A second concern is that the functional effects of BALF EVs may result from non-physiological and excess amount of EVs used in functional studies. To limit this potential problem, we first isolated BALF MVs from one mouse. Next, we instilled the single mouse-derived MVs into the recipient mouse in a 1:1 ratio.

During the processes of EV isolation using sequential centrifugation, several critical steps required attention. First, it is best if EV isolation is performed immediately, immediately after BALF is collected. We observed significant EV aggregation and size alteration when EVs are isolated using the frozen BALF. It is presumably difficult to recover the original character of EVs after freezing. Second, we recommend a soft sonication of the isolated EVs using water-bath sonicator, before the EV NTA or functional assays are performed. The soft sonication effectively disperses the EV aggregates which are possibly generated during the sequential centrifugation or freeze/thaw step. This step significantly contributes to consistency of the obtained results. Third, we do not recommend a long-term storage of the isolated EVs. We noted a remarkable destruction of EV components, such as proteins and RNAs, after the long-term storage of the EVs.

Collectively, the present study provide the first evidence that sterile and infectious stimuli-induced MVs were differentially generated in vivo. Despite the diverse sources of EVs, both sterile stimuli-induced EVs and infection-induced EVs facilitated classic AM activation, and subsequently promoted inflammatory lung responses via different signaling pathways. Based on our observation, non-infectious ALI models would be suitable for EV research focusing on lung epithelial cells, while the infectious ALI models are probably better to study BALF EVs derived from AMs or other immunomodulatory cells, as proposed in Figure 6. Our results potentially provide novel insights into the role of EVs research in ALI and experimental strategies using various ALI models.

Figure 6. Proposed mechanisms of EV function in ALIs.

Under non-infectious conditions, such as hyperoxia and acid exposure, lung epithelial cells are the first cells to actively produce EVs. These epithelial EVs contribute to the development of inflammatory lung responses by activating AMs. Conversely, after bacterial infections, alveolar macrophages are the first defender and main immune cells in the lung. Alveolar macrophages generate pro-inflammatory EVs and propagate lung inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Bruce Levy and his laboratory for the information and education on the acid inhalation-induced lung injury model.

This work was supported by NIH grants: R01HL102076, R21AI121644, R33 AI121644, R01GM111313, R01GM127596, Wing Tat Lee award (to Y.J.) and ES004738, AR055073 and ES005022 (to D.L.)

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tkach M, and Thery C. 2016. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell 164: 1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chargaff E, and West R. 1946. The biological significance of the thromboplastic protein of blood. J Biol Chem 166: 189–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H, Zhang D, Zhu Z, Dela Cruz CS, and Jin Y. 2016. Epithelial cell-derived microvesicles activate macrophages and promote inflammation via microvesicle-containing microRNAs. Sci Rep 6: 35250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moldovan L, Batte K, Wang Y, Wisler J, and Piper M. 2013. Analyzing the circulating microRNAs in exosomes/extracellular vesicles from serum or plasma by qRT-PCR. Methods Mol Biol 1024: 129–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crescitelli R, Lasser C, Szabo TG, Kittel A, Eldh M, Dianzani I, Buzas EI, and Lotvall J. 2013. Distinct RNA profiles in subpopulations of extracellular vesicles: apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and exosomes. J Extracell Vesicles 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turturici G, Tinnirello R, Sconzo G, and Geraci F. 2014. Extracellular membrane vesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication: advantages and disadvantages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 306: C621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campanella C, Bucchieri F, Merendino AM, Fucarino A, Burgio G, Corona DF, Barbieri G, David S, Farina F, Zummo G, de Macario EC, Macario AJ, and Cappello F. 2012. The odyssey of Hsp60 from tumor cells to other destinations includes plasma membrane-associated stages and Golgi and exosomal protein-trafficking modalities. PLoS One 7: e42008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, Orr L, and Turbide C. 1987. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J Biol Chem 262: 9412–9420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng YH, Rome S, Jalabert A, Forterre A, Singh H, Hincks CL, and Salamonsen LA. 2013. Endometrial exosomes/microvesicles in the uterine microenvironment: a new paradigm for embryo-endometrial cross talk at implantation. PLoS One 8: e58502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalli J, Norling LV, Renshaw D, Cooper D, Leung KY, and Perretti M. 2008. Annexin 1 mediates the rapid anti-inflammatory effects of neutrophil-derived microparticles. Blood 112: 2512–2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulinelli S, Salaro E, Vuerich M, Bozzato D, Pizzirani C, Bolognesi G, Idzko M, Di Virgilio F, and Ferrari D. 2012. IL-18 associates to microvesicles shed from human macrophages by a LPS/TLR-4 independent mechanism in response to P2X receptor stimulation. Eur J Immunol 42: 3334–3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkin-Smith GK, Paone S, Zanker DJ, Duan M, Phan TK, Chen W, Hulett MD, and Poon IK. 2017. Isolation of cell type-specific apoptotic bodies by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Sci Rep 7: 39846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suchorska WM, and Lach MS. 2016. The role of exosomes in tumor progression and metastasis (Review). Oncol Rep 35: 1237–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, and Martin TR. 2008. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L379–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McVey M, Tabuchi A, and Kuebler WM. 2012. Microparticles and acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L364–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto K, Ferrari JD, Cao Y, Ramirez MI, Jones MR, Quinton LJ, and Mizgerd JP. 2012. Type I alveolar epithelial cells mount innate immune responses during pneumococcal pneumonia. J Immunol 189: 2450–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y, Kim HP, Cao J, Zhang M, Ifedigbo E, and Choi AM. 2009. Caveolin-1 regulates the secretion and cytoprotection of Cyr61 in hyperoxic cell death. FASEB J 23: 341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatnagar S, Shinagawa K, Castellino FJ, and Schorey JS. 2007. Exosomes released from macrophages infected with intracellular pathogens stimulate a proinflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Blood 110: 3234–3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman SL, and Seed P. 2012. Intracellular Macrophage Infections with E. coli under Nitrosative Stress. Bio Protoc 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon HG, Cao Y, Yang J, Lee JH, Choi HS, and Jin Y. 2015. Lung epithelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles activate macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses via ROCK1 pathway. Cell Death Dis 6: e2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traber KE, Hilliard KL, Allen E, Wasserman GA, Yamamoto K, Jones MR, Mizgerd JP, and Quinton LJ. 2015. Induction of STAT3-Dependent CXCL5 Expression and Neutrophil Recruitment by Oncostatin-M during Pneumonia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 53: 479–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkin-Smith GK, Tixeira R, Paone S, Mathivanan S, Collins C, Liem M, Goodall KJ, Ravichandran KS, Hulett MD, and Poon IK. 2015. A novel mechanism of generating extracellular vesicles during apoptosis via a beads-on-a-string membrane structure. Nat Commun 6: 7439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clancy JW, Sedgwick A, Rosse C, Muralidharan-Chari V, Raposo G, Method M, Chavrier P, and D’Souza-Schorey C. 2015. Regulated delivery of molecular cargo to invasive tumour-derived microvesicles. Nat Commun 6: 6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang HM, Li Q, Zhu X, Liu W, Hu H, Liu T, Cheng F, You Y, Zhong Z, Zou P, Li Q, Chen Z, and Guo AY. 2016. miR-146b-5p within BCR-ABL1-Positive Microvesicles Promotes Leukemic Transformation of Hematopoietic Cells. Cancer Res 76: 2901–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HD, Kim YH, and Kim DS. 2014. Exosomes derived from human macrophages suppress endothelial cell migration by controlling integrin trafficking. Eur J Immunol 44: 1156–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dye BR, Hill DR, Ferguson MA, Tsai YH, Nagy MS, Dyal R, Wells JM, Mayhew CN, Nattiv R, Klein OD, White ES, Deutsch GH, and Spence JR. 2015. In vitro generation of human pluripotent stem cell derived lung organoids. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fehrenbach H, Zissel G, Goldmann T, Tschernig T, Vollmer E, Pabst R, and Muller-Quernheim J. 2003. Alveolar macrophages are the main source for tumour necrosis factor-alpha in patients with sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 21: 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gauna AE, and Cha S. 2014. Akt2 deficiency as a therapeutic strategy protects against acute lung injury. Immunotherapy 6: 377–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Goncalves R, and Mosser DM. 2008. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter 14: Unit 14 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee H, Zhang D, Wu J, Otterbein LE, and Jin Y. 2017. Lung Epithelial Cell-Derived Microvesicles Regulate Macrophage Migration via MicroRNA-17/221-Induced Integrin beta1 Recycling. J Immunol 199: 1453–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu R, Greening DW, Rai A, Ji H, and Simpson RJ. 2015. Highly-purified exosomes and shed microvesicles isolated from the human colon cancer cell line LIM1863 by sequential centrifugal ultrafiltration are biochemically and functionally distinct. Methods 87: 11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klimentova J, and Stulik J. 2015. Methods of isolation and purification of outer membrane vesicles from gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Res 170: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jay SJ, Johanson WG Jr., Pierce AK, and Reisch JS. 1976. Determinants of lung bacterial clearance in normal mice. J Clin Invest 57: 811–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain-Vora S, LeVine AM, Chroneos Z, Ross GF, Hull WM, and Whitsett JA. 1998. Interleukin-4 enhances pulmonary clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 66: 4229–4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matzer SP, Baumann T, Lukacs NW, Rollinghoff M, and Beuscher HU. 2001. Constitutive expression of macrophage-inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) mRNA in bone marrow gives rise to peripheral neutrophils with preformed MIP-2 protein. J Immunol 167: 4635–4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein E, Lippert W, and Warshauer D. 1974. Pulmonary alveolar macrophage. Defender against bacterial infection of the lung. J Clin Invest 54: 519–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warner N, and Nunez G. 2013. MyD88: a critical adaptor protein in innate immunity signal transduction. J Immunol 190: 3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ermolaeva MA, Michallet MC, Papadopoulou N, Utermohlen O, Kranidioti K, Kollias G, Tschopp J, and Pasparakis M. 2008. Function of TRADD in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling and in TRIF-dependent inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol 9: 1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nolan A, Kobayashi H, Naveed B, Kelly A, Hoshino Y, Hoshino S, Karulf MR, Rom WN, Weiden MD, and Gold JA. 2009. Differential role for CD80 and CD86 in the regulation of the innate immune response in murine polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS One 4: e6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu MF, Li JS, Weng TH, and Lei HY. 1999. Differential expression and modulation of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on monocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Immunol 49: 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creery WD, Diaz-Mitoma F, Filion L, and Kumar A. 1996. Differential modulation of B7–1 and B7–2 isoform expression on human monocytes by cytokines which influence the development of T helper cell phenotype. Eur J Immunol 26: 1273–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Modelska K, Pittet JF, Folkesson HG, Courtney Broaddus V, and Matthay MA. 1999. Acid-induced lung injury. Protective effect of anti-interleukin-8 pretreatment on alveolar epithelial barrier function in rabbits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160: 1450–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kopf M, Schneider C, and Nobs SP. 2015. The development and function of lung-resident macrophages and dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 16: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arango Duque G, and Descoteaux A. 2014. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol 5: 491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Z, Zhang D, Lee H, Menon AA, Wu J, Hu K, and Jin Y. 2017. Macrophage-derived apoptotic bodies promote the proliferation of the recipient cells via shuttling microRNA-221/222. J Leukoc Biol 101: 1349–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng D, Zhao WL, Ye YY, Bai XC, Liu RQ, Chang LF, Zhou Q, and Sui SF. 2010. Cellular internalization of exosomes occurs through phagocytosis. Traffic 11: 675–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, and Carter DR. 2014. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J Extracell Vesicles 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Urbanelli L, Magini A, Buratta S, Brozzi A, Sagini K, Polchi A, Tancini B, and Emiliani C. 2013. Signaling pathways in exosomes biogenesis, secretion and fate. Genes (Basel) 4: 152–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chevillet JR, Kang Q, Ruf IK, Briggs HA, Vojtech LN, Hughes SM, Cheng HH, Arroyo JD, Meredith EK, Gallichotte EN, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Morrissey C, Stirewalt DL, Hladik F, Yu EY, Higano CS, and Tewari M. 2014. Quantitative and stoichiometric analysis of the microRNA content of exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 14888–14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner MD, Nedjai B, Hurst T, and Pennington DJ. 2014. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843: 2563–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Puneet P, Moochhala S, and Bhatia M. 2005. Chemokines in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goodman RB, Pugin J, Lee JS, and Matthay MA. 2003. Cytokine-mediated inflammation in acute lung injury. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 14: 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ha M, and Kim VN. 2014. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 509–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lafferty EI, Qureshi ST, and Schnare M. 2010. The role of toll-like receptors in acute and chronic lung inflammation. J Inflamm (Lond) 7: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang D, Liang J, Li Y, and Noble PW. 2006. The role of Toll-like receptors in non-infectious lung injury. Cell Res 16: 693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang JY, Nan X, Jin MS, Youn SJ, Ryu YH, Mah S, Han SH, Lee H, Paik SG, and Lee JO. 2009. Recognition of lipopeptide patterns by Toll-like receptor 2-Toll-like receptor 6 heterodimer. Immunity 31: 873–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Muhlradt PF, Morr M, Radolf JD, Zychlinsky A, Takeda K, and Akira S. 2001. Discrimination of bacterial lipoproteins by Toll-like receptor 6. Int Immunol 13: 933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.