Abstract

The brain, which governs most, if not all, physiological functions in the body, from the complexities of cognition, learning and memory, to the regulation of basal body temperature, heart rate and breathing, has long been known to affect skeletal health. In particular, the hypothalamus – located at the base of the brain in close proximity to the medial eminence, where the blood-brain-barrier is not as tight as in other regions of the brain but rather “leaky”, due to fenestrated capillaries – is exposed to a variety of circulating body cues, such as nutrients (glucose, fatty acids, amino acids), and hormones (insulin, glucagon, leptin, adiponectin) [1]–[3]. Information collected from the body via these peripheral cues is integrated by hypothalamic sensing neurons and glial cells [4]–[7], which express receptors for these nutrients and hormones, transforming these cues into physiological outputs. Interestingly, many of the same molecules, including leptin, adiponectin and insulin, regulate both energy and skeletal homeostasis. Moreover, they act on a common set of hypothalamic nuclei and their residing neurons, activating endocrine and neuronal systems, which ultimately fine-tune the body to new physiological states. This review will focus exclusively on the brain-to-bone pathway, highlighting the most important anatomical sites within the brain, which are known to affect bone, but not covering the input pathways and molecules informing the brain of the energy and bone metabolic status, covered elsewhere [8]–[10]. The discussion in each section will present side by side the metabolic and bone-related functions of hypothalamic nuclei, in an attempt to answer some of the long-standing questions of whether energy is affected by bone remodeling and homeostasis and vice versa.

Keywords: hypothalamus, pituitary, bone, energy metabolism

Introduction

What do we know about the effects of brain on bone?

Classically, the hypothalamus has been recognized mainly for its neuroendocrine functions. Every hormone either produced directly by hypothalamic nuclei (principally, the paraventricular nucleus, PVN) or secreted to further stimulate de novo hormone secretion from the anterior pituitary gland and subsequently from the target organs, is linked to either bone formation, bone resorption, or both [11]–[17]. As documented in several research publications, very often, the hormones and their downstream molecular pathways which regulate energy metabolism, also regulate bone. At first glance, it appears that the whole body metabolic status is intrinsically connected to the bone status and vice versa. Just to name a few examples, estrogen deficiency due to ovarian failure is known to lead to osteoporosis in postmenopausal women since the 1940’s [18]. Estrogen is however a component of the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPG) which starts from the synthesis of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) by the GnRH neurons present in the preoptic area (POA) in response to signals originating from the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus [19]. Here, we would like to draw a special attention to ARC, as our later discussion of neuronal circuits controlling bone formation and resorption will focus extensively on this anatomical site. GnRH released from the medial eminence, then travels via hypophyseal capillary portal blood stream to the anterior pituitary, where it triggers the production of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which are released into the systemic bloodstream, reach gonads, ultimately causing a release of estrogen, progesterone and androgens [20], [21] Numerous clinical data showed that estrogen and androgen deficiency leads to profound bone loss due to increased osteoclast (OC) numbers and activity [22]–[30]. In fact, ovariectomy is considered to be a gold standard animal model of osteoporosis [31], [32]. In addition, early osteoporosis was also discovered in men and women during times of sex steroid sufficiency [27], [28], paving the way to findings that FSH, which is elevated in post-menopausal women, and directly stimulates bone resorption by osteoclasts [33], may be responsible for an estrogen-independent loss of bone [33]–[35]. This topic, – however, still remains controversial [36]–[39]. Of interest, a deep correlation exists between the fertility system and neuronal ARC circuits involved in the regulation of feeding and energy metabolism [40]. Estrogen controls the expression of several feeding-related ARC neuropeptides, including Agouty-related protein (AgRP), neuropeptide-Y (NPY), proopiomelanocortin (POMC), and cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) [41]–[43], which we will elaborate upon is subsequent discussion, while these neuropeptides regulate the expression and GnRH neuron activity [19], [44], [45] in feedback manner. This close interplay between estrogen, hypothalamic neuropeptides and pituitary hormones shows the multifactorial regulation of bone homeostasis, involving more than one physiological system.

Another example, where brain derived hormones regulate skeletal health includes the hypothalamo-pituitary-thyroid axis (HPT). Low circulating levels of thyroid hormones T3 and T4 are sensed by the hypothalamus, and trigger the production of thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and its release at the medial eminence (similar to the route traveled by GnRH), followed by the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) release from the anterior pituitary, which then acts on the thyroid gland [46]. Hyperthyroidism has an anabolic effect during skeletal growth, and TSH Receptor-null mice, were shown to be osteoporotic [15] but TSH also has catabolic effects in adults, increasing bone turnover and bone loss [13], [14], [47], [48]. Moreover, a large collection of clinical trials demonstrated that, independently of thyroid hormone levels, TSH exerts anti-resorptive, bone-promoting effects, favoring net bone gain [15], [36], [46], [49]–[51]. The role of the HPT axis in the regulation of appetite and body weight are well known [52], [53]. PVN-residing TRH neurons were shown to send strong excitatory projections to the ARC-residing AgRP neurons [54]. Of note, mutation in leptin, which binds to AgRP and POMC neurons in mice and humans results in hypothyroidism [55], [56], while leptin reverses the fall in T3+T4 observed during fasting [57], further illustrating the close interplay between ARC and systems regulating energy metabolism and bone. The role of other pituitary hormones was recently discussed in greater details elsewhere (for reviews, see [16], [21]).

While the endocrine mechanisms continue to be explored, the last two decades opened the gate for a boisterous stream of research into the identity of the particular neuronal circuits regulating bone remotely, at the level of the brain. This attention shift coincided with the better understanding of general neuronal functions and the specific features of hypothalamic circuits involved in body homeostasis. The discovery of glucose-, leptin- and insulin-sensing by the ARC neurons [8], [58]–[62] offered plausible mechanisms by which the brain could monitor skeletal state and thus, formed the basis for the initiation of brain-bone research. Indeed, all the aforementioned nutrients and hormones were shown act on the hypothalamus and profoundly alter bone mass. In this review we will highlight some of the main anatomical sites in the brain – nuclei and their residing neurons – implicated in skeletal and energy metabolism regulation and the mechanisms by which they respond to peripheral cues. Particular attention will be given to ARC, Ventromedial nucleus (VMN), and PVN. We will cover some of the intrinsic neuronal traits, including the synaptic plasticity in response to changes in diet [63]–[66], the ability to dynamically alter neuropeptide expression levels, and mitochondrial composition [67]–[70], as well as changes in neuronal firing, which ultimately lead to new energy/bone state. – It is however important to keep in mind that the central neuronal circuitry is tightly interconnected with both the pituitary endocrine arm and the peripheral nervous system, including the sympathetic (SNS), the parasympathetic (PNS) and the sensory (SeNS) nervous systems, and should therefore not be viewed as an isolated entity. Rather, central neurons rely on endocrine and neuronal mediators to deliver their signal to target sites. This review will attempt to describe the known neuronal inputs and outputs, utilized by the brain to control bone. Finally, we will cover the hormonal mediators, such osteocalcin and lipocalin-2 potentially used by bone to communicate back to the brain.

Which hypothalamic regions regulate energy metabolism and bone?

Arcuate Nucleus

AgRP/NPY neurons drive hunger

The hypothalamus has long been known as an orchestrator of feeding and energy metabolism. Physical, chemical or tumor-induced (often craniopharyngioma) damage to the hypothalamus results in excessive feeding, or “hypothalamic obesity”. This term was first defined by Babinsky and Frohlich, at the turn of 20th century [71]. Later, in 1942 Hetherington and Ranson showed that lesions to the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) or ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) in rats, lead to hypophagia and hyperphagia, respectively, giving rise to the prevailing “dual center” theory, according to which, one hypothalamic site is responsible for hunger and the other for satiety [72]. Soon enough, it became clear that this is not the case, as rats do not overeat or starve indefinitely, but instead reach a new weight “set point”, suggesting the existence of more complex regulatory mechanisms. An arc-shaped hypothalamic region, located at the bottom of 3rd ventricle, above the medial eminence – the ARC – harbors two populations of neurons, identified on the basis of the dominant neuromediator they synthesize and secrete upon activation: the “anabolic” Agouti Related Peptide (AgRP)/Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and the “catabolic” Proopiomelanocortin (POMC)/Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) neurons, which counterbalance body weight (Fig. 1). AgRP neuropeptide expression is restricted to the ARC, while POMC is also expressed in a brainstem area, called Nucleus Tractus Solitarius (NTS) [56], [73], [74]. CART and NPY are concentrated in the hypothalamus, but show a broad distribution pattern in both the central and peripheral nervous systems [56], [73]. Earlier work with genetically engineered mice showed that, surprisingly, knockout of either AgRP or NPY peptides had minimal effect on energy balance [75], yet genetic ablation of AgRP or POMC neurons in their entirety, (not just peptides), using the diphtheria toxin approach, produced marked anorexia and obesity, respectively, suggesting that global neuronal activity, rather than a specific neuropeptide, is required to modulate feeding [76], [77]. Furthermore, AgRP neurons send inhibitory GABAergic projections to POMC neurons, inhibiting their activity [78], [79], although some POMC neurons were recently shown to also express GABA [80]. Activation of neuronal firing of AgRP/NPY neurons by optogenetic means [81] or by designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADS) [54], induces voracious feeding within minutes. AgRP-mediated hunger drive may occur independently of melanocortin suppression [81], [82], [83], [84], although a requirement for melanocortin receptors, MC4Rs has also been reported [54], [78], [85], [86]. Beyond actual feeding, AgRP neuronal activation also triggers an intense food seeking behavior [54], [86]–[88]. Interestingly, AgRP neurons appear to be dispensable for palatable foods [89], indicating that other neuronal circuits are likely to be involved in the regulation of feeding.

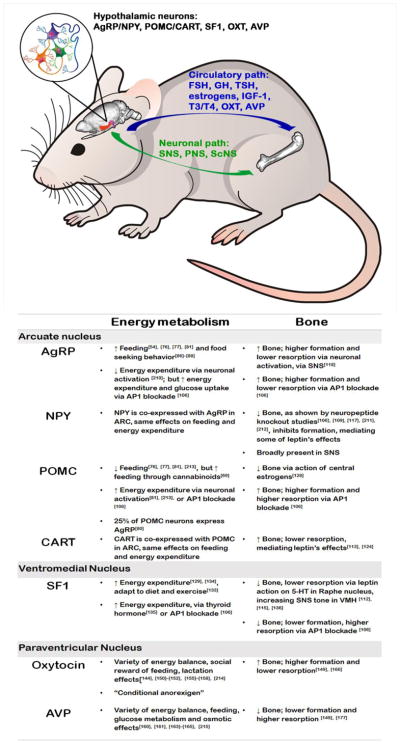

Figure 1. Arcuate nucleus and ventromedial hypothalamus regulate whole body energy metabolism and bone.

Hypothalamus (an area located at the ventral part of the brain, denoted in red) receives peripheral input in the form of body cues – circulating nutrients (glucose, fatty acids, amino acids) and humoral hormones (insulin, glucagon, leptin, adiponectin, ghrelin) which bind to their respective receptors on hypothalamic cells and trigger a metabolic response. This response includes initiation or cessation of appetite, changes in energy expenditure, glucose balance, alterations in fat depots, as well as long-term changes and skeletal homeostasis. Within the hypothalamus, ARC is known to harbor a population of orexigenic AgRP/NPY/GABA expressing neurons co-residing with a population of anorexigenic POMC/CART neurons, although recent studies highlight significant level of heterogeneity within the two. Galanin is also known to be expressed in ARC and is colocolized with AgRP/NPY and POMC/CART neurons. Anterior to ARC lays the VMH marked by the presence of SF-1 neurons. Specific activation of ARC and VMH neurons was shown to trigger endocrine pituitary and/or neuronal (SNS, PNS) downstream response which is ultimately directed at maintaining metabolic and skeletal homeostasis. (Figure constructed using Allen mouse brain volumetric atlas).

Physical proximity to the medial eminence and presence of receptors to circulating hormones, such as insulin (pancreatic hormone stimulating blood glucose uptake), leptin (fat secreted adiposity “thermostat”, counteracting the effects of ghrelin), ghrelin (GI secreted appetite inducer), and PYY (GI secreted appetite suppressor) endows AgRP/NPY and POMC/CART neurons with intrinsic ability to swiftly respond to acute and chronic changes in body energy status. After a meal, ghrelin levels are low, while insulin levels rise, directly inhibiting the activity of orexigenic AgRP/NPY neurons and activating anorexigenic POMC/CART neurons. Conversely, during prolonged fasting, when ghrelin secretion is increased, while leptin, insulin and PYY are low, the orexigenic AgRP/NPY neurons take over, “switching gears” toward energy repletion [66], [71], [90]. Differential effects of adipokines and GI hormones on ARC neurons was demonstrated by multiple studies, where targeted ablation of receptors from AgRP or POMC neurons leads to body weight alterations [8], [58], [59], [91]. The signal originating from the ARC “1st order neurons” is transduced to “2nd order neurons” residing in other hypothalamic nuclei (such as PVN), as well as in more remote sites of the brain. Indeed, cell type-specific neuronal circuit manipulations revealed tight reciprocal connections between ARC and PVN, the parabrachial nucleus (PBN), NTS, Raphe Pallidus (RaP), and Ventral Tigmental Area (VTA) [82], [92]. Optogenetic activation of the ARC > LHA and ARC > PVN projections is sufficient to stimulate feeding comparable to activation of AgRP/NPY neurons themselves [93]. Inhibitory AgRP input to PVN was shown to target oxytocin (OXT) neurons [94], which play a role in glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as bone homeostasis (discussed below). OXT neurons are selectively lost in Prader-Willi syndrome, a condition involving insatiable hunger [94]. The same study found that ARC > PBN input is not required for feeding, whereas others showed that the AgRP/NPY > PBN pathway stimulates food intake [84], [95]. Adding to the list of extra-hypothalamic sites to which ARC communicates, AgRP/NPY neurons were recently shown to project to the bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST), reprogramming brown fat (responsible for adaptive thermogenesis) towards insulin resistance and reduced energy expenditure [96]. For in depth reviews of the intra-hypothalamic and extra-hypothalamic networks, please see [92], [97].

While the role of ARC in energy metabolism remains undisputed, the dominant paradigm that AgRP/NPY and POMC/CART neurons co-exist in strictly “dual” control of energy metabolism has recently been challenged by emerging literature. A recent study showed that activation of POMC neurons promotes – as opposed to suppresses – feeding and energy conservation, through the involvement of cannabinoids [69]. Moreover, recent transcriptomic analysis of isolated single cell POMC neurons reported that over 25% co-express AgRP mRNA [80], supporting another set of data showing that some AgRP neurons express low levels of POMC [98]. These observations may stem from the fact that AgRP/NPY and POMC/CART neurons differentiate from a common progenitor [99], and thus are not entirely discrete, i.e. that although expressing a dominant neuropeptide, these neurons also express, at lower levels, some of the other neuropeptides, making interpretation of data more difficult (see below).

ARC neurons also regulate bone homeostasis, possibly independently of energy

Recent studies from our lab demonstrated that despite classically opposed roles in feeding, both AgRP-expressing and POMC-expressing neurons can be triggered to orchestrate an energy burning state when AP1 signaling is impaired by expression of ΔFosB, a natural isoform of the AP1 transcription factor FosB that lacks the C-terminal transactivation domain and acts as an AP1 antagonist [100]. ΔFosB acts as a central regulator of both energy metabolism and bone [101]–[105]. Mice overexpressing ΔFosB driven by the enolase2 (ENO2) promoter exhibit a striking phenotype of elevated energy expenditure, increased insulin sensitivity, reduced adiposity, and high bone mass due to increased bone formation [102], [104], [105]. Moreover, mice in which ΔFosB or the artificial AP1 antagonist dominant-negative JunD (DNJunD) are stereotactically targeted to the ventral hypothalamus (VHT) phenocopy the ENO2-ΔFosB mice phenotypes [103]. We then used AP1 antagonism as a tool to identity the precise hypothalamic circuits involved in the regulation of energy metabolism and bone. By combining genetically- and stereotactically-restricted delivery of several AP1 antagonists, including ΔFosB, Δ2ΔFosB (a further truncated form of FosB) and DNJunD, or the AP1 agonist FosB, to AgRP-, POMC-, or steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1)-producing neurons, engineered to express the Cre-recombinase, we showed the ability of blockade of the AP1 machinery to consistently induce whole body energy metabolism in either neuron type. AP1 antagonism in either AgRP/NPY- or POMC/CART-expressing neurons drives utilization of energy, with a calorimetric increase in heat production, glucose utilization and a corresponding reduction in adiposity [106]. Importantly, two results suggest that the link between energy expenditure and bone remodeling is not as clear as previously suggested. First, we found that if neurons predominantly present in the ARC are responsible for the increase in bone formation and bone mass, they exert different and neuron-specific effects on bone resorption. Second, and even more compelling, VMH SF1 neurons exert the same increase in energy expenditure and glucose metabolism but have the opposite effect on bone, decreasing bone mass via a decrease in bone formation and an increase in bone resorption, indicating that the changes in body metabolism and bone may not be causally linked [106].

While energy-conserving AgRP/NPY and energy-expending POMC/CART neurons generally conform to the metabolic polarity, their effects on the skeleton appear less uniform. Studies from Baldock’s lab established NPY as a negative regulator of bone. Germline NPY−/− mice exhibit high bone mass, in both the axial and appendicular skeleton, with increased osteoblast activity [107]. Similarly, virus-mediated NPY targeting to the ARC, but not hippocampus, of NPY−/− mice, partially restored the original phenotype [107], [108]. NPY is known to function via 5 receptors (Y1-Y6) with differential tissue expression. Global and conditional deletion of Y2R, highly expressed in the hypothalamus, replicated the high cancellous bone phenotype seen in germline NPY−/− mice [109], [110]. Inactivation of hypothalamic Y1R failed to affect bone, and further research suggested that Y1R on osteoblasts mediated paracrine, rather than central anabolic effects of NPY on bone [111], [112]. ARC-residing AgRP/NPY neurons are known to express leptin receptors, and given the leptin’s anti-osteogenic effect on bone [113]–[117], it was suggested that leptin and NPY may share regulatory pathways. Hypothalamic Y2R deletion, however, did not alter systemic leptin levels, suggesting that the brain-NPY-bone pathway may function independently from the brain-leptin-bone pathway. This notion is further supported by studies showing that leptin and Y2R double deletion (Y2R−/− ob/ob mice) had no additive effect on bone [108]. Subsequent work suggested that NPY mediates some of leptin central effects on cortical, but not trabecular bone [118]. Thus, it appears that the neuropeptide NPY is one of the neurotransmitters involved in hypothalamic regulation of bone mass. It should however be noted that NPY and its receptors are also present in peripheral tissues and cells, including bone, and some of the effects of global deletions may actually be the results of NPY actions in bone and not only in the CNS

A first study documenting directly the role of AgRP neurons in skeletal biology was published in 2015. Horvath’s group used two genetic models to suppress AgRP neuronal firing, through targeted expression of Ucp2 or Sirt1; and a model of targeted neonatal AgRP neuronal ablation, through targeted expression of diphtheria toxin receptors [119]. Weakening of AgRP activity or complete neuronal loss produced an osteopenic phenotype, sensitive to treatment with the β-adrenergic receptor blocker, propranolol. These data suggest that AgRP neurons function as positive regulators of bone, increasing formation and suppressing resorption when activated, in part via the SNS [119]. Interestingly, leptin receptor deletion from AgRP/NPY neurons, previously shown to increase body weight and adiposity [59], did not affect bone [119], suggesting that AgRP may affect bone in a leptin-independent manner.

Intuitively, at first glance, the anti- and pro-osteogenic effects of NPY and AgRP, respectively, might appear discrepant. However, it should be noted that the effect of neuropeptides often differs from the effect of entire neurons. Global deletion of either AgRP or NPY neuropeptides has negligible effects on feeding and weight [75], whereas full ablation of AgRP or NPY neurons leads to starvation [76], indicating that neuronal activity, rather than neuropeptide expression is important for feeding regulation. While the study linking AgRP and bone measured neuronal firing [119], most studies linking NPY and bone manipulated only the level of the neuropeptide [120]. Our study differs, in that we targeted ΔFosB to AgRP- or NPY-expressing neurons, and found high bone mass phenotype without changes in the level of AgRP itself [106]. It is plausible to suggest AP1 antagonism in AgRP/NPY neurons, inhibited neuronal firing, since the AP1 agonist c-fos is a marker of neuronal activation [121].

The research efforts to explore the link between brain and bone are in large part the consequence of the discovery by Karsenty’s lab that the fat-derived hormone leptin, the deletion of which is responsible for the obesity of ob/ob mice, acts as a negative regulator of bone. Indeed, according to this group, the genetic deletion of leptin (ob/ob) or of leptin receptor (db/db) results in a phenotype of high bone mass [10], [115], [122]. Furthermore, intracerebroventricular (icv) injection of leptin in wild type mice reduces bone formation [122]. Leptin was shown to promote a 2-fold increase in hypothalamic expression of CART in mice deficient of MC4R, which binds a product of POMC cleavage, α-melanocortin stimulating hormone (α-MSH). MC4R null mice display obesity and high bone mass phenotype [114] and mutation of this receptor in humans also contributes to the development of obesity [123]. On the other hand, mice devoid of CART have a normal appetite and are fertile, but display an osteoporosis phenotype due to an isolated increase in bone resorption parameters [114]. Therefore, Karsenty’s group hypothesized that CART may function downstream of leptin. Indeed, deletion of CART alleles in MC4R−/− mice corrected their bone phenotype, although the metabolic phenotype remained unchanged [124], supporting the hypothesis that these two phenotypes are not directly linked. Overall, leptin was suggested to act via two antagonistic mechanisms: negatively affecting bone mass via central activation of the sympathetic tone [116] and of the serotonergic system [113], and positively affecting bone mass via CART (by suppressing osteoclastogenesis). These authors suggested that the skeletal effects of leptin are mediated centrally, whereas CART was reported to have the strongest influence as a circulating hormone [125]. It should be noted however that others have shown direct effects of leptin within the bone environment, where it is produced by bone marrow adipocytes [126], [127]

There are only few reports documenting the involvement of brain POMC neurons (either peptide signaling or neuronal firing) in the regulation of bone. Scarce data supports the binding of POMC cleavage fragments to MC4Rs located on osteoblasts [17], [128]. More recently, one report showed that female mice lacking estrogen receptors in POMC neurons display an increase in cortical bone mass and mechanical strength [129], suggesting that estrogens have a negative effect on bone mass when binding to their receptors in POMC neurons in the ARC, contrary to their direct positive effects on bone. Our studies showed that similarly to AgRP/NPY neurons, targeting of AP1 antagonists to either POMC or CART neurons increases bone formation and bone mass. Importantly, this effect required the presence of central galanin [106].

Overall, literature points toward the involvement of at least 2 distinct neuronal populations within ARC in the control of bone mass, namely the AgRP/NPY- and POMC/CART-expressing neurons. It appears that neuropeptide release per se has a different effect from neuronal activation/firing action potential, as evident from the NPY and AgRP neuron studies, showing one as negative and the other as positive regulator of bone, respectively. Future work is needed to clarify the relationship between neuropeptide level and neuronal electrochemical behavior. Moreover, effort should be directed at understanding how distinct AgRP/NPY and POMC/CART neurons can be orchestrated to trigger a unidirectional increase in bone formation, such as seen following AP1 blockade and elevation in galanin release.

Ventromedial Nucleus

SF-1 neurons adapt to metabolic stimuli, such as diet and exercise, and negatively regulate bone

VMH, an elliptical shape nucleus, located right above the ARC, harbors MC4Rs-expressing, “2nd order” neurons, with which AgRP/NPY and POMC/CART communicate (Fig. 1). It is also the site of SF-1 producing neurons, implicated in the control of adiposity, energy expenditure and thermogenesis [130]. Although, these neuronal population are heterogeneous, SF-1 is expressed exclusively in the VMH and considered to be its marker [131]. The generation of SF-1-CRE mice allowed targeted manipulations of various molecules. Intriguingly, deletion of leptin receptors from SF-1 neurons [130] resulted in virtually comparable phenotype to the one observed with leptin receptor removal from POMC or both AgRP and POMC neurons, manifested by mild obesity and reduced energy expenditure [8], [59], [132]. The bone phenotype of these mice has not however been reported. Loss of insulin receptor in SF-1 neurons also triggered obesity and impaired glucose tolerance [133]. Of note, while these neurons are generally considered to be the “hunger and satiety” neurons, leptin or insulin receptor deletion either from AgRP, POMC, or SF-1 does not affect feeding [59], [61], [130], [132]. Moreover, a common characteristic among mice bearing genetic ablations in SF-1 neurons is a metabolic dysfunction, but only following exposure to high fat diet, not the normal chow, which was characterized as an “inability to adapt to thermogenic environment” [131]. However, even on a normal chow diet, mice with VMH SF-1 deletion show impaired endurance during exercise [134]. Deletion of FOXO1 (a transcription factor involved in the mediation of insulin signaling) in SF-1 neurons produces a lean phenotype due to high energy expenditure [135]. Mice lacking FOXO1 in SF-1 also fail to appropriately suppress energy expenditure in response to fasting. Thyroid hormones - which according to classical view, in a state of hyperthyroidism act peripherally and locally, to induce hyperphagia and weight loss [52], [53], concurrently with high bone turnover and bone loss [13], [14], [47], [48] – were recently shown to increase thermogenesis, energy expenditure, and lipogenesis via activation of AMPK-ER stress axis involving SNS and PNS in the VMH SF-1 neurons [136]. Likewise, mice lacking estrogen receptors in SF-1 neurons, display hypophagia and infertility, yet normal energy expenditure [41]. Collectively these studies indicate that SF-1 in the VMH is required for adaptations to metabolic stimuli, such as high fat diet or exercise.

Originally, studies from Karsenty’s lab, showed that leptin requires an intact VMH to exert its negative effect on bone mass. Mice with chemically destroyed VMH (by gold-thioglucose), showed unchanged bone volume, in response to infused leptin [116]. Surprisingly, selective deletion of leptin receptors in the VMH failed to elicit a bone phenotype, suggesting that leptin signaling in the VMH does not affect bone, raising the possibility that it might be acting elsewhere in the brain [130] and affect the VMH secondarily. Indeed, subsequent research by the Karsenty’s group proposed a pathway, where leptin does not act directly on the hypothalamus, but instead on the brainstem, where it inhibits serotonin production and release by the raphe nuclei. These serotonergic neurons then project to VMH, where via action on Htr2c receptors, increase SNS tone and inhibit bone accrual, and ARC, where via of Htr1a and Htr2b receptors, regulate appetite [113], [137]. Another study, however, showed that leptin does not directly affect brain serotonin neurons [138]. They observed that while leptin hyperpolarizes some non-serotonin producing raphe neurons, it does not alter the activity of serotonergic ones. Likewise, serotonin depletion did not impair the anorectic effects of leptin [138]. Moreover, within the ARC, leptin and serotonin in fact bind to a different types of POMC neurons [139], suggesting that further research is needed to resolve the controversial leptin - serotonin link in the control of metabolism and bone. Of interest, the brainstem raphe nucleus, via which leptin pathway was suggested to take its course, was recently shown by Friedman’s lab to contain GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons which exert reciprocal and bidirectional regulation of feeding and body weight, independently of leptin [140]. Transcriptional analysis of these neurons revealed that glutamatergic, but not GABAergic Raphe nucleus terminals also express markers of serotonin synthesis. These findings raise the possibility that these excitatory and inhibitory brainstem neurons may also be involved in the regulation of bone biology independently of leptin.

The neuropeptide galanin, which may act as a central regulator of bone formation, is abundantly expressed within the ARC, PVN and MPA [141], is virtually absent from the VMH [142]. Targeting of AP1 blockers specifically to ARC neurons, AgRP/NPY or POMC/CART, increased bone mass (in galanin dependent manner), while targeting of AP1 blockers to VMH neurons, SF-1, produced a contrastingly opposite phenotype of reduced bone mass (in galanin independent manner).

Overall, VMH and its residing SF1 neurons participate in the regulation of skeletal mass, via the involvement of Raphe nucleus, SNS activation and possibly leptin. Manipulation with AP1 blockade suggest that there is an anatomical dissociation in the regulation of bone, at the level of hypothalamic ARC and VMH nuclei.

Paraventricular Nucleus

Oxytocin and Vasopressin – two similar molecules sharing a range of metabolic functions

Oxytocin and arginine vasopressin (AVP) are two ancient peptides, differing only by two amino acids, apparently evolved from the same cell type with neurosensory properties linking energy metabolism, reproduction, and bone. Oxytocin and AVP are produced by hypothalamic PVN and supraoptic nucleus (SON), located rostrally to (anterior) to the ARC, within large, magnocellular neurons (20–30 μm in diameter) (Fig. 2). Classically, oxytocin is associated with labor and lactation, mediating uterine contractions and milk-ejection reflex, while AVP is linked to the regulation of osmotic balance, promoting antidiuresis, following change in the serum osmolality. Structural homology suggests that AVP arose from oxytocin by gene duplication [143], [144]. Unlike the GnRH or TRH, which trigger further hormone production by the anterior pituitary, oxytocin and AVP neurons (from PVN and SON) directly pass their long tracts to the Herring bodies of the posterior pituitary, where peptide containing vesicles are stored until their ultimate discharge into the circulation. In rodents, a functionally separate process mediates the distribution of these peptides centrally, via parvocellular neurons (7–10 μm in diameter), and it is presumed that a similar mechanism is at play in humans [145]. Thus, oxytocin and AVP function both as hormones (circulating) and neuropeptides (released into the synaptic space), binding peripheral and central targets, in particular the VMH, ARC, nucleus accumbens (NAc), NTS and dorsal nucleus of vagus (mainly serving the PNS) [144], [146], [147]. Oxytocin is binding a single OXTR receptor, while AVP is known to bind at least three receptor types, AVPR1a, AVPR1b/V3 and AVPR1b/V2. Both peptides cross-react with each other’s receptors; for example, oxytocin binds to OXTR with only 10x greater affinity than AVP [145], [148]. These receptors are also capable of forming hetero-, homo-, or oligo-dimers and display broad distribution pattern peripherally and centrally. It has been shown that oxytocin and AVP concentrations can be up to 1000X higher in the brain [145], [149], peaking later and lasting longer than in the peripheral blood. Both peptides are closely associated with a variety of classical neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, and exist in a close relationship with the components of the hypothalamic pituitary axis. For example, AVP has been shown to enhance corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH)-mediated production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary, which in turn facilitates stress response [145], [147].

Figure 2. Paraventricular nucleus and supraoptic nucleus regulate whole body energy metabolism and bone.

Also located in the hypothalamus (an area denoted in red), but anterior to ARC and VMH are PVN and SON areas, which are the principal sites of oxytocin and AVP production. PVN is tightly connected with ARC, as well as other areas in the brain, including the amygdala, brainstem (Raphe nuclei, NTS, VTA.) spinal cord, mesolimbic dopaminergic system (nucleus accumbens) and cortex. Oxytocin and AVP peptides which are produced in the hypothalamus are delivered to the posterior pituitary from which they are discharged into the circulation to control energy balance and skeletal homeostasis. Oxytocin is considered to be anabolic, while AVP is considered to be catabolic to bone. Both hormones are also known to function as neuropeptides binding to their receptors within the brain to affect various aspects of social behavior. (Figure constructed using Allen mouse brain volumetric atlas).

Recent years highlighted additional properties for both oxytocin and AVP in a variety of physiological and psychological systems. The “extramural” actions of oxytocin include – social (pair bonding, parental) behavior, energy balance and skeletal homeostasis; while AVP is also involved in – pain, hypertension, inflammation, cognition, aging, obesity and bone [145], [146], [148], [150]. Early experiments showed that oxytocin promotes natriuresis in rats – stimulating sodium excretion, while inhibiting sodium ingestion [151]. The last two decades positioned oxytocin also as a molecule linked to food cessation [144]. Oxytocin neurons are preferentially activated by ingestion of sweet-tasting carbohydrates (c-Fos immunolabeling is used to measure neuronal activation) [152], [153], while oxytocin preferentially inhibits their ingestion. Plasma oxytocin levels are higher in fed animals [146], [151]–[155], compared to animals anticipating meal. – Oxytocin, however, is not essential for the control of feeding, as knockout mice consume similar amount of food [156], and so do mice with genetically targeted neuronal ablation [157], although both models develop late-onset obesity due to lower SNS tone, rather than hypophagia. The actions of oxytocin were linked to NAc (located rostral to SON, comprising part of the mesolimbic pathway implicated in motivation, reward, and substance addiction). Human studies examining the effect of intranasal oxytocin application (albeit, at supraphysiological doses) showed a reduction in energy uptake [158], [159]. While, generally, oxytocin is viewed as “anorexigenic”, there are certain instances where it triggers an opposite induction in feeding, such as in the case of anxiety [152], [153]. It has been accordingly suggested that oxytocin suppresses reward-driven food intake, while enhancing social reward, acting as a “conditional anorexigen” whose effects depend on physiological and social context [144]. Oxytocin, by the virtue of being a social hormone, plays a prominent role in balancing feeding and sexual behavior. These behaviors are not mutually compatible, animals are unlikely to eat while mating and vice versa. Delayed and long-lasting dendritic release of oxytocin from magnocellular neurons was suggested to contribute to post-prandial satiety, while promoting post-prandial sexual appetite [144], [160]. AVP neurons are also activated after feeding in rats and mice [161], [162], yet the activation of magnocellular AVP neurons received less attention, probably because it is assumed that this reflects antidiuretic reflex in anticipation of the solute load that accompanies food intake. Several studies suggest the involvement of AVP in the etiology of diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Human studies found that a mutation in AVPR1a leads to higher fasting blood glucose level and obesity [163]. Another study showed that people drinking less water have a higher chance of developing diabetes [164]. Experiments in diabetic rats showed that AVP is capable of acting directly on the pancreatic alpha- and beta- cells increasing glucagon and insulin secretion, affecting blood glucose level [165]. Finally, infusion of AVP in obese male subjects exaggerated pituitary response, ACTH and cortisol release, resulting in hyperglycemia [166].

Oxytocin is anabolic, while vasopressin is catabolic for bone

Both hormones of the neurohypophyseal system, oxytocin and AVP, were also shown to affect skeletal homeostasis and bone marrow adiposity [47], [146], [150]. Oxytocin is anabolic to bone [167]. Osteoblasts produce oxytocin and express OXTRs, and there is evidence that it serves as a paracrine/autocrine regulator of bone formation, modulated by estrogens. In addition, OXT may exert indirect effects on bone as it affects the adipokines leptin and adiponectin, influencing bone [168], [169]. Oxytocin stimulates osteoblastogenesis (favoring osteoblast over adipocyte differentiation) and inhibits osteoclast activity [47], [150]. OXTR signaling increases intracellular calcium levels [170], which triggers the Ca2+-ERK1/2 pathway, known to activate the key osteogenic runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and blocks the key adipogenic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) [171]. Accordingly, oxytocin knockout mice are osteopenic – they display lower trabecular bone mass in femurs and vertebrae, lower mineral apposition rate and downregulated genes for osteoblast differentiation [47], [150], [167], [172]. Interestingly, haploinsufficient oxytocin or OXTR null mice develop osteopenia, while milk let-down remains normal, indicating that the bone is even more sensitive to fluctuation in OXT levels, then lactation [167]. In rabbits, oxytocin was shown to reverse glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis [173] and in mice, to prevent the ovariectomy-induced bone loss [174], [175]. Daily, subcutaneous injections of oxytocin for 8 weeks improved bone microarchitecture and biomechanical strength, while reducing bone marrow adiposity in female, ovariectomized mice. Interestingly, in male mice which underwent orchidectomy (male model of hypogonadism), oxytocin normalized only the metabolic, but not bone, defects, suggesting that skeletal and fat masses are differentially regulated [175]. Large human cohort studies found a direct correlation between oxytocin levels and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women, but not in men [176], [177]. Physiologically, the anabolic effect of oxytocin may explain the rapid bone loss recovery following weaning, when the plasma oxytocin levels are still high [150]

AVP, which is mainly involved in the regulation of osmotic balance and structurally similar to oxytocin, is also involved in skeletal health. In contrast to oxytocin, AVP appear to be catabolic to bone, as AVP receptor null mice have high bone mass [150], [178]. AVP can affect bone directly, as both AVPR1A and AVPR2 were found to be expressed in osteoblast and osteoclasts, or via modulation of other hypothalamic pituitary hormones, including CRH and ACTH [145], [147], as well by affecting the release of classical neurotransmitters such as serotonin, known to regulate bone. The increased bone formation and suppressed resorption, observed in AVPR1A deficient mice is also seen following treatment with AVPR1A antagonist, SR49059 [178]. This effect appears to be receptor specific, as AVPR2 showed not role in bone remodeling [150] and deletion of OXTR in double knockout mice (OXTR−/−; AVPR1A−/−), reversed the high bone mass seen with AVPR1A deletion alone [150]. Intriguingly, as mentioned above, oxytocin and AVP are closely related peptides, capable of binding each other’s receptors, which in turn implies that some of their functions are shared. Yet, the opposing effects of oxytocin and AVP on bone suggest an existence of complex regulatory mechanism, capable of discriminating between two peptides.

Regulation of skeletal mass is not the only instance where the roles of oxytocin and AVP diverge. For example, in rats, systemic injections of cholecystokinin (CCK), a peptide hormone released from duodenum in response to food ingestion, inhibit AVP neurons, but activate the oxytocin neurons, and stimulate oxytocin secretion into the blood [179]. Likewise, oxytocin is thought to attenuate stress response by inhibiting ACTH and cortisol secretion, while AVP facilitates it, by increasing ACTH and cortisol release. Social studies data, especially those obtained using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) technology also show difference between the response to oxytocin or AVP administration, while performing a task, such as emotion recognition (looking at fearful images, sound of infant crying), prisoner’s dilemma, etc. Having said that, it is important to highlight the variable and often conflicting literature describing the social effects of oxytocin and AVP, granting further investigation [145].

How do signals from hypothalamic nuclei reach bone?

As described in the introduction, one way by which hypothalamus influences energy metabolism and bone is by regulating the secretion of pituitary hormones. Another means by which hypothalamus communicates back to the periphery, to regulate fat storage, glucose levels and skeletal mass, involves all three arms of the autonomic nervous system – SNS, PNS, and SeNS. Importantly, neuronal and endocrine systems are closely interlinked and function in accord to maintain whole body homeostasis [9], [130], [180].

SNS and PNS interact with pituitary hormones to induce short-term regulation of appetite and glucose levels, and long-term regulation of energy expenditure

The autonomic nervous system sends signals both ways, communicating from the brain to the periphery and back. Dysregulation in the activity of the autonomic nervous system is often associated with metabolic pathologies, such as chronic sympathetic overflow present in obesity, although the cause is not entirely clear. Conversely, obesity might also affect functional aspects of the autonomic nervous system, favoring the development of cardiovascular complications. The role of the autonomic nervous system in the regulation of energy homeostasis can generally be categorized as short-term and long-term effects. The short-term afferent signals involve gastric distension (mediated by vagal afferents) and the release of several gut hormones, including cholecystokinin (CCK), peptide YY (PYY), pancreatic polypeptide (PP), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), as well as ghrelin, which is released by the stomach. These peripheral hormones are thought to reach the brain NTS area via vagal afferent nerves. These projections then proceed to hypothalamus and trigger an endocrine pituitary response and/or modulate the efferent activity of SNS and PNS. Hypothalamic PVN is heavily innervated by both SNS and PNS terminals [9], [130], [180], and projects further to brainstem sites, including the locus coeruleus (LC) – principal site for noradrenaline synthesis, controlling SNS; and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) – controlling the vagus nerve, the chief output of the PNS [5], [181]–[184]. In simplified terms, during energy replete status, peripheral cues coming in the form of insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and PYY are sensed by the hypothalamic neurons (AgRP and POMC), causing activation of SNS and glucocorticoid production by HPA, triggering a counter-response to promote pancreatic glucagon release over insulin production and directing the return to normoglycemia [5], [181], [182]. The long-term signals are involved mainly in the regulation of energy expenditure and brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis. BAT, previously thought to be present only in newborn babies, is now known to play a key role in mediating non-shivering thermogenesis and in diet-induced thermogenesis in adults. Central signal triggers norepinephrine release from BAT SNS terminals, stimulating β3-adrenoceptors that turns on a cascade of intracellular events ending in activation of uncoupling proteins (UCP 1,2,3). These are mitochondrial transporters which favor energy dissipation in the form of heat, over ATP synthesis [185], [186]. Patients with surgical unilateral sympathectomy show a detectable uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose in BAT by positron emission tomography only on the unaffected side, but not on the side lacking SNS terminals [187]. Moreover, studies found that healthy obese men have lower BAT volume and activity in response to cold, compared to lean men [188] and expose to cold increases insulin sensitivity in diabetic patients [189]. Of note, leptin, which acts on the ARC to regulate feeding, appears to play a crucial role in the upregulation of SNS-mediated BAT thermogenesis in rodents [190]. In general, the activity of PNS counteracts SNS, yet there are many instances where both systems are activated, such as for the induction of glucagon release, or where only one of the systems was shown to be directly involved, such as SNS in BAT thermogenesis. The precise molecular mechanisms employed by the autonomic nervous system in the regulation of whole body energy metabolism are complex, involving activation of α– and β-adrenergic receptors, on heart, liver, pancreas, sweat glands, and other target tissues [191], and are beyond the scope of this review.

SNS is a negative regulator of bone, PNS is a positive regulator of bone

Another example where SNS and PNS converge with the neuroendocrine system is bone homeostasis. On one hand, bone is subjected to intense hormonal regulation by estrogen, growth hormone and parathyroid and thyroid hormones [47], and on another hand, bone is negatively regulated by SNS, via a mechanism involving leptin, CART, serotonin [114], [116], [192] and NPY [120], stimulating βARs signaling in OB; and is positively regulated by PNS, via stimulation of nAchRs in osteoclasts [193]. The efferent sympathetic pathway reaching bone was first demonstrated with chemical sympathectomy [194] and then using transgenic mice models. Parabiosis studies between leptin deficient ob/ob showed that only in a mouse receiving icv leptin infusion is the bone phenotype rescued, suggesting that a neuronal, rather than circulating mechanism is used [116]. Then, icv leptin infusion in Dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH)-deficient mice, lacking the enzyme synthesizing epinephrine and norepinephrine, the two mediators of the SNS, failed to affect bone mass. Finally, the involvement of the SNS in transmitting brain-bone signals was shown through failure to rectify the high bone mass phenotype in mice lacking the β2AR, following icv leptin infusion [114], suggesting that functional adrenergic receptor signaling is necessary to mediate the central effect of leptin on bone. Subsequent studies showed that SNS activation works via induction of the osteoblast-derived soluble factor receptor activator NF-κB ligand (RANKL), which in turn augments osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption [195]. While NPY is a known neurotransmitter of the SNS, so far studies indicate that central NPY-mediated pathway functions to affect cortical bone, independently from the leptin-SNS-mediated pathway, responsible for the trabecular bone increase in ob/ob mice [118], [195].

Cholinergic activity has been shown to favor bone mass via suppression of SNS and promoting the apoptosis of osteoclasts. Mice lacking nicotinic AchR in bone display lower bone mass due to higher osteoclast activity [193]. Despite these intriguing observations, the exact pathways by which the cholinergic system affects bone mass remain to be elucidated. Recent reviews summarize in greater details the effects of SNS and PNS on bone [9], [195], [196]. Recently, the ScNS was also shown to play a role in skeletal biology, as conditional deletion of Sema3A, a factor necessary for sensory neuronal development (regulating axon guidance and growth), from neurons, rather than from bone, resulted in lower bone mass, suggesting that osteoblasts are affected indirectly, via sensory nerves [197], [198]. Another study in squamous cell carcinomas, showed that IGF-I-driven production of Sema4D promotes osteoclastogenesis and bone invasion [199].

How does bone affect the brain?

The skeleton, X-rayed by a beam of brain cues is not a passive target, but rather an active participant, sending information back to the brain and other organs. Over a decade ago, Karsenty’s group showed that osteocalcin, the second most plentifully expressed protein in the bone, after collagen type I, behaves as hormone, stimulating the release of insulin from pancreatic β-cell, and the release of fat-derived adiponectin, which boosts insulin sensitivity [200]. Osteocalcin exists in two biochemical forms – the carboxylated “Gla”, bound to hydroxyapatite mineral, and the undercarboxylated “Glu”, released into circulation [10]. Osteocalcin participates in a “feed-forward” loop, where insulin, acting on bone-residing insulin receptors, stimulates the biochemical conversion of osteocalcin from inactive “Gla” form to an active “Glu” form (a process which involves ATF4 and FoxO1 and transcription factors, as well as osteotesticular protein tyrosine phosphatase, Esp) in an acidic osteoclastic milieu, which subsequently facilitates further insulin secretion [201]. Osteocalcin was also shown to affect cell glucose metabolism directly, via stabilization of hypoxia-inducible-factor 1, HIF1α [202], [203], a factor which plays a major role in skeletal development [204]. Beyond its role in controlling glucose and energy metabolism, osteocalcin was reported to regulate reproductive organs [205], muscle [206], and in particular, the brain, where it affects hippocampal development and cognitive functions [207]. The metabolic and muscle functions of osteocalcin are mediated by the G-protein coupled receptor GPRC6A, and the brain functions via yet known receptor. Very recently, another bone-derived hormone was discovered, lipocalin-2, shown to suppress appetite by activation of hypothalamic MC4Rs [208]. For recent, comprehensive reviews on osteocalcin and lipocalin-2 see [10], [209], [210]. Collectively, these findings imply that brain and bone co-exist in close reciprocal relationship, where both partners are involved in the regulation of whole organism energy and skeletal homeostasis.

Concluding remarks

In this review we presented the currently known mechanisms by which the brain regulates skeletal homeostasis, focusing on the most prominent brain centers, in particular, the hypothalamic nucsorlei - ARC, VMH, PVN, and SON, as well as extra-hypothalamic areas including the brainstem Raphe nucleus, and their residing neurons. We also covered endocrine (OXT, AVP) and neuronal (SNS, PNS and ScNS) output relays transmitting information from the high centers to the remote skeletal sites, (Fig. 3). Our discussion was structured in such a way, that metabolic influences were juxtaposed with the skeletal influences. Although our understanding of the precise mechanisms governing these processes is far from complete, it becomes apparent that most of the studied circuits, have the capacity to shape both energy metabolism and skeletal homeostasis. Yet, as suggested by the cumulative experimental evidence, this regulation does not always follow a unidirectional track. There are instances where the effects of feeding and changes in body weight do not trigger changes in bone mass, or where discrete neurons cause an increase in energy expenditure and an increase in bone formation, while others cause an equal increase in energy expenditure with an opposite reduction in bone formation. Overall, this suggests that whole body energy homeostasis and skeleton can be dissociated, at least at the level of hypothalamic neurons. Future studies are required to delineate this split-up. Furthermore, additional work is required to understand how central neurons communicate with the peripheral target sites. Specifically, how is the firing activity of primary and secondary neurons affected? Are signaling molecules, such as AgRP, NPY, galanin, and others released into brain neuronal milieu? Do they function as neurotransmitters in peripheral terminals? Are they also secreted into the general circulation? Answers to these questions will expand our understanding of the complex skeletal physiology and will help develop novel therapeutics against bone related diseases, such as osteoporosis.

Figure 3. Central output regulating skeletal homeostasis.

Hypothalamus utilizes endocrine and neuronal mechanisms to communicate back to the bone. Endocrine route involves all hormones produced by the anterior pituitary gland, including the adrenal, thyroid, gonadal, and somatotropic axis; as well as the posterior pituitary gland, producing oxytocin and AVP. These factors either directly or indirectly, via the release of target tissue hormones, affect both the arms of energy metabolism and bone. – Another route, involves modulation of the activity of the autonomic nervous system, comprising SNS, PNS, (and recently implicated ScNS), which activate adrenergic and/or cholinergic receptors located on bone cells, changing bone formation and resorption to maintain skeletal homeostasis.

Highlights.

Neurons originating in the hypothalamus regulate bone homeostasis

The same neurons are involved in the regulation of energy expenditure and feeding

Pathways linking hypothalamus to bone involve SNS, PNS, and pituitary hormones

List of abbreviations

- ACTH

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AgRP

Agouty-related protein

- ARC

Arcuate nucleus

- AVP

Vasopressin

- BNST

Bed nucleus of stria terminalis

- CART

Cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CRH

Corticotropin releasing hormone

- DMV

Dorsal motor nucleus of vagus

- FSH

Follicle stimulating hormone

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- GnRH

Gonadotropin releasing hormone

- HPG

Hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis

- HPT

Hypothalamo-pituitary axis

- LC

Locus coeruleus

- LH

Luteinizing hormone

- LHA

Lateral hypothalamic area

- MPA

Medial preoptic area

- Nac

Nucleus accumbens

- NPY

Neuropeptide-Y

- NTS

Nucleus tractus solitarius

- OXT

Oxytocin

- PBN

Parabrachial nucleus

- PNS

Parasympathetic nervous system

- POA

Preoptic area

- POMC

Proopiomelanocortin

- PP

Pancreatic polypeptide

- PVN

Paraventricular nucleus

- PYY

Peptide YY

- RaP

Raphe pallidus

- SeNS

Sensory nervous system

- SF-1

Steroidogenic factor-1

- SNS

Sympathetic nervous system

- SON

Supraoptic nucleus

- TRH

Thyrotropin releasing hormone

- TSH

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- VHT

Ventral hypothalamus

- VMH

Ventromedial hypothalamus

- VTA

Ventral tegmental area

- α-MSH

α–Melanocortin stimulating hormone

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haddad-Tóvolli R, Dragano NRV, Ramalho AFS, Velloso LA. Development and Function of the Blood-Brain Barrier in the Context of Metabolic Control. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:224. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magnan C, Levin BE, Luquet S. Brain lipid sensing and the neural control of energy balance. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015 Dec;418:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam TKT, Schwartz GJ, Rossetti L. Hypothalamic sensing of fatty acids. Nat Neurosci. 2005 May;8(5):579–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leloup C, Allard C, Carneiro L, Fioramonti X, Collins S, Pénicaud L. Glucose and hypothalamic astrocytes: More than a fueling role? Neuroscience. 2015 Jun;323:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinbusch L, Labouèbe G, Thorens B. Brain glucose sensing in homeostatic and hedonic regulation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Sep;26(9):455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorens B. Brain glucose sensing and neural regulation of insulin and glucagon secretion. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011 Oct;13(Suppl 1):82–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Routh VH, Hao L, Santiago AM, Sheng Z, Zhou C. Hypothalamic glucose sensing: making ends meet. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:236. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varela L, Horvath TL. Leptin and insulin pathways in POMC and AgRP neurons that modulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis. EMBO Rep. 2012 Dec;13(12):1079–86. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitri P, Rosen C. The Central Nervous System and Bone Metabolism: An Evolving Story. Calcif Tissue Int. 2017 May;100(5):476–485. doi: 10.1007/s00223-016-0179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karsenty G, Ferron M. The contribution of bone to whole-organism physiology. Nature. 2012 Jan;481(7381):314–20. doi: 10.1038/nature10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khosla S, Oursler MJ, Monroe DG. Estrogen and the skeleton. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Nov;23(11):576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen A, Pike CJ. Menopause, obesity and inflammation: interactive risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015 Jan;7:130. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey CB, et al. Molecular mechanisms of thyroid hormone effects on bone growth and function. Mol Genet Metab. 2002 Jan;75(1):17–30. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H-Y, Mohan S. Role and Mechanisms of Actions of Thyroid Hormone on the Skeletal Development. Bone Res. 2013 Jun;1(2):146–161. doi: 10.4248/BR201302004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novack DV. TSH, the bone suppressing hormone. Cell. 2003 Oct;115(2):129–30. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00812-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaidi M, et al. Pituitary-bone connection in skeletal regulation. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2016 Jan;28(2):85–94. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2016-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaidi M, et al. ACTH protects against glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis of bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 May;107(19):8782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ALBRIGHT F. Osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 1947 Dec;27(6):861–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-27-6-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padilla SL, et al. AgRP to Kiss1 neuron signaling links nutritional state and fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017 Feb;114(9):2413–2418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621065114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riggs BL. The mechanisms of estrogen regulation of bone resorption. J Clin Invest. 2000 Nov;106(10):1203–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI11468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quiros-Gonzalez I, Yadav VK. Central genes, pathways and modules that regulate bone mass. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014 Nov;561:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almeida M, et al. Estrogens and Androgens in Skeletal Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. Jan;97(1):135–187. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boonen S, et al. Osteoporosis management: a perspective based on bisphosphonate data from randomised clinical trials and observational databases. Int J Clin Pract. 2009 Dec;63(12):1792–1804. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin T, et al. Comparison of clinical efficacy and safety between denosumab and alendronate in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2012 Apr;66(4):399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nayak S, Edwards DL, Saleh AA, Greenspan SL. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the performance of clinical risk assessment instruments for screening for osteoporosis or low bone density. Osteoporos Int. 2015 May;26(5):1543–1554. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3025-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moradi S, Shab-bidar S, Alizadeh S, Djafarian K. Association between sleep duration and osteoporosis risk in middle-aged and elderly women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Metabolism. 2017 Apr;69:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riggs BL, et al. Population-Based Study of Age and Sex Differences in Bone Volumetric Density, Size, Geometry, and Structure at Different Skeletal Sites. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Sep;19(12):1945–1954. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riggs BL, et al. A population-based assessment of rates of bone loss at multiple skeletal sites: evidence for substantial trabecular bone loss in young adult women and men. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 Feb;23(2):205–14. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.071020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eastell R, Szulc P. Use of bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Jul; doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis treatment: recent developments and ongoing challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Jul; doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komori T. Animal models for osteoporosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015 Jul;759:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oheim R, Schinke T, Amling M, Pogoda P. Can we induce osteoporosis in animals comparable to the human situation? Injury. 2016 Jan;47:S3–S9. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(16)30002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun L, et al. FSH directly regulates bone mass. Cell. 2006 Apr;125(2):247–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cannon JG, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone, interleukin-1, and bone density in adult women. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010 Mar;298(3):R790–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00728.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devleta B, Adem B, Senada S. Hypergonadotropic amenorrhea and bone density: new approach to an old problem. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004 Jul;22(4):360–4. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colaianni G, Cuscito C, Colucci S. FSH and TSH in the regulation of bone mass: the pituitary/immune/bone axis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013 May;2013:382698. doi: 10.1155/2013/382698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gourlay ML, Specker BL, Li C, Hammett-Stabler CA, Renner JB, Rubin JE. Follicle-stimulating hormone is independently associated with lean mass but not BMD in younger postmenopausal women. Bone. 2012 Jan;50(1):311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gourlay ML, Preisser JS, Hammett-Stabler CA, Renner JB, Rubin J. Follicle-stimulating hormone and bioavailable estradiol are less important than weight and race in determining bone density in younger postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2011 Oct;22(10):2699–708. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1505-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baron R. FSH versus estrogen: who’s guilty of breaking bones? Cell Metab. 2006 May;3(5):302–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.López M, Tena-Sempere M. Estrogens and the control of energy homeostasis: a brain perspective. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Aug;26(8):411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Y, et al. Distinct hypothalamic neurons mediate estrogenic effects on energy homeostasis and reproduction. Cell Metab. 2011 Oct;14(4):453–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y, et al. Role of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript in estradiol-mediated neuroprotection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Sep;103(39):14489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602932103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olofsson LE, Pierce AA, Xu AW. Functional requirement of AgRP and NPY neurons in ovarian cycle-dependent regulation of food intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Sep;106(37):15932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904747106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amiya N, Amano M, Tabuchi A, Oka Y. Anatomical relations between neuropeptide Y, galanin, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the brain of chondrostean, the Siberian sturgeon Acipenser baeri. Neurosci Lett. 2011 Oct;503(2):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roa J, Herbison AE. Direct Regulation of GnRH Neuron Excitability by Arcuate Nucleus POMC and NPY Neuron Neuropeptides in Female Mice. Endocrinology. 2012 Nov;153(11):5587–5599. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nikrodhanond AA, et al. Dominant Role of Thyrotropin-releasing Hormone in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis. J Biol Chem. 2006 Feb;281(8):5000–5007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imam A, et al. Role of the pituitary-bone axis in skeletal pathophysiology. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009 Dec;16(6):423–9. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283328aee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bassett JHD, Williams GR. Role of Thyroid Hormones in Skeletal Development and Bone Maintenance. Endocr Rev. 2016 Apr;37(2):135–187. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mazziotti G, Porcelli T, Patelli I, Vescovi PP, Giustina A. Serum TSH values and risk of vertebral fractures in euthyroid post-menopausal women with low bone mineral density. Bone. 2010 Mar;46(3):747–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tournis S, et al. Volumetric bone mineral density and bone geometry assessed by peripheral quantitative computed tomography in women with differentiated thyroid cancer under TSH suppression. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2015 Feb;82(2):197–204. doi: 10.1111/cen.12560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim DJ, Khang YH, Koh JM, Shong YK, Kim GS. Low normal TSH levels are associated with low bone mineral density in healthy postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006 Jan;64(1):86–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garasto S, et al. Thyroid hormones in extreme longevity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017 Mar; doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amin A, Dhillo WS, Murphy KG. The central effects of thyroid hormones on appetite. J Thyroid Res. 2011 May;2011:306510. doi: 10.4061/2011/306510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krashes MJ, et al. An excitatory paraventricular nucleus to AgRP neuron circuit that drives hunger. Nature. 2014 Feb;507(7491):238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature12956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Froguel P, et al. A mutation in the human leptin receptor gene causes obesity and pituitary dysfunction. Nature. 1998 Mar;392(6674):398–401. doi: 10.1038/32911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beck B. Neuropeptides and obesity. Nutrition. 2000 Oct;16(10):916–23. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahima RS, et al. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996 Jul;382(6588):250–2. doi: 10.1038/382250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cone RD, Cowley MA, Butler AA, Fan W, Marks DL, Low MJ. The arcuate nucleus as a conduit for diverse signals relevant to energy homeostasis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Dec;25(Suppl 5):S63–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van de Wall E, et al. Collective and individual functions of leptin receptor modulated neurons controlling metabolism and ingestion. Endocrinology. 2008 Apr;149(4):1773–85. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parton LE, et al. Glucose sensing by POMC neurons regulates glucose homeostasis and is impaired in obesity. Nature. 2007 Sep;449(7159):228–32. doi: 10.1038/nature06098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berglund ED, et al. Direct leptin action on POMC neurons regulates glucose homeostasis and hepatic insulin sensitivity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012 Mar;122(3):1000–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI59816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown LM, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC, Woods SC. Intraventricular insulin and leptin reduce food intake and body weight in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol Behav. 2006 Dec;89(5):687–91. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nuzzaci D, et al. Plasticity of the Melanocortin System: Determinants and Possible Consequences on Food Intake. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015 Sep;6 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeltser LM, Seeley RJ, Tschöp MH. Synaptic plasticity in neuronal circuits regulating energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 2012 Oct;15(10):1336–42. doi: 10.1038/nn.3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dietrich MO, Horvath TL. Hypothalamic control of energy balance: insights into the role of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2013 Feb;36(2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dietrich MO, Horvath TL. Feeding signals and brain circuitry. Eur J Neurosci. 2009 Nov;30(9):1688–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nasrallah CM, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial dynamics in the central regulation of metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 Sep;10(11):650–658. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dietrich MO, Liu ZW, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial Dynamics Controlled by Mitofusins Regulate Agrp Neuronal Activity and Diet-Induced Obesity. Cell. 2013 Sep;155(1):188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koch M, et al. Hypothalamic POMC neurons promote cannabinoid-induced feeding. Nature. 2015 Feb;519(7541):45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature14260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith KL, et al. Overexpression of CART in the PVN increases food intake and weight gain in rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Oct;16(10):2239–44. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lustig RH. Hypothalamic obesity after craniopharyngioma: mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2011;2:60. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hetherington AW, Ranson SW. THE SPONTANEOUS ACTIVITY AND FOOD INTAKE OF RATS WITH HYPOTHALAMIC LESIONS. Am J Physiol -- Leg Content. 1942 Jun;136(4):609–617. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wellhauser L, Gojska NM, Belsham DD. Delineating the regulation of energy homeostasis using hypothalamic cell models. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2015 Jan;36:130–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anderson EJP, et al. 60 YEARS OF POMC: Regulation of feeding and energy homeostasis by α-MSH. J Mol Endocrinol. 2016 May;56(4):T157–T174. doi: 10.1530/JME-16-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qian S, et al. Neither agouti-related protein nor neuropeptide Y is critically required for the regulation of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002 Jul;22(14):5027–35. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5027-5035.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005 Oct;310(5748):683–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gropp E, et al. Agouti-related peptide-expressing neurons are mandatory for feeding. Nat Neurosci. 2005 Oct;8(10):1289–91. doi: 10.1038/nn1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tong Q, Ye CP, Jones JE, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Synaptic release of GABA by AgRP neurons is required for normal regulation of energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 2008 Sep;11(9):998–1000. doi: 10.1038/nn.2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ollmann MM, et al. Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science. 1997 Oct;278(5335):135–8. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lam BYH, et al. Heterogeneity of hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin-expressing neurons revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Mol Metab. 2017 May;6(5):383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aponte Y, Atasoy D, Sternson SM. AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci. 2011 Mar;14(3):351–5. doi: 10.1038/nn.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Atasoy D, et al. A genetically specified connectomics approach applied to long-range feeding regulatory circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2014 Dec;17(12):1830–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu Q, Howell MP, Cowley MA, Palmiter RD. Starvation after AgRP neuron ablation is independent of melanocortin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008 Feb;105(7):2687–2692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712062105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu Q, Boyle MP, Palmiter RD. Loss of GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons to the parabrachial nucleus leads to starvation. Cell. 2009 Jun;137(7):1225–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sohn JW, et al. Melanocortin 4 receptors reciprocally regulate sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons. Cell. 2013 Jan;152(3):612–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krashes MJ, et al. Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011 Apr;121(4):1424–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI46229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Betley JN, et al. Neurons for hunger and thirst transmit a negative-valence teaching signal. Nature. 2015 Apr;521(7551):180–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen Y, Lin Y-C, Kuo T-W, Knight ZA. Sensory detection of food rapidly modulates arcuate feeding circuits. Cell. 2015 Feb;160(5):829–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Denis RGP, et al. Palatability Can Drive Feeding Independent of AgRP Neurons. Cell Metab. 2015 Oct;22(4):646–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lustig RH. Hypothalamic obesity: causes, consequences, treatment. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008 Dec;6(2):220–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Könner AC, et al. Insulin action in AgRP-expressing neurons is required for suppression of hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab. 2007 Jun;5(6):438–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]