Highlights

-

•

Acute adrenal insufficiency, although rare, is the most frequently reported endocrine manifestation of the APS.

-

•

Major surgery has been identified as a precipitating factor for this potentially fatal condition.

-

•

Effective treatment requires timely diagnosis and intervention at the acute phase. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is crucial. The APLS patients who overcome the acute phase bear a favorable prognosis regarding restoration of their adrenal function.

Abbreviations: APS, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; AI, adrenal insufficiency; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; CT, computerized tomography; LA, lupus anticoagulant; aCL, anticardiolipin antibody; anti-(2)GPI, anti-β(2)-glycoprotein I antibodies

Keywords: Colorectal surgery, Acute adrenal insufficiency, Antiphospholipid syndrome, Adrenal haemorrhage

Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous bilateral adrenal hemorrhage or hemorrhagic necrosis due to adrenal vein thrombosis is an uncommon condition that may lead to acute adrenal insufficiency and death. The objective of this report is to enhance recognition of this potentially fatal disorder in surgical patients.

Presentation of cases

We present two cases of acute adrenal insufficiency due to bilateral adrenal hemorrhage associated with primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS). Both cases occurred in the early postoperative period after major colorectal surgery. Major vein thrombosis, abdominal pain, anorexia, asthenia, lethargy and an unexplained drop in patient’s hemoglobin without evidence of sepsis were the principal symptoms and signs that, with a high index of suspicion, led to the correct diagnosis.

Discussion

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an acquired thrombophilia caused by circulating antibodies against a heterologous group of phospholipids. Recent literature has identified a causative relation between APS and primary adrenal insufficiency (AI), identifying it as its most common endocrine manifestation. Surgeries along with inflammation or hormones have been identified as precipitating factors. Spontaneous haemorrhagic infarction of the adrenal glands has been observed in patients with APS in the postoperative period during anticoagulant treatment. Signs and symptoms are non-specific and are easily confused with those of the underlying condition.

Conclusions

Early recognition and prompt treatment of adrenal insufficiency due to APS in surgical patient is of vital importance. Patients correctly diagnosed and treated that survive the critical phase have a better prognosis regarding restoration of adrenal function.

1. Introduction

We present two surgical cases complicated with acute adrenal insufficiency, due to bilateral adrenal hemorrhage associated with primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS). Cases are reported in line with the SCARE criteria [1]. The objective of our report is to enhance prompt diagnosis of this potentially fatal disorder by analyzing its clinical course, diagnostic algorithm and causative factors.

2. Case report

2.1. Case 1

A 65 year old female with unremarkable past medical history was admitted to our clinic as an emergency with large bowel obstruction. CT scan of the abdomen showed distended loops of small and large bowel with a transition point at the level of the sigmoid colon. After an enema administration per rectum to clean the distal bowel, the patient underwent a flexible sigmoidoscopy which confirmed the presence of an obstructing carcinoma 25 cm above the dentate line. Blood results revealed anemia (Ht = 29%) and an elevated white cell count (12500/mm3). Electrolytes were normal and no clotting abnormalities were identified preoperatively (Fig. 1).

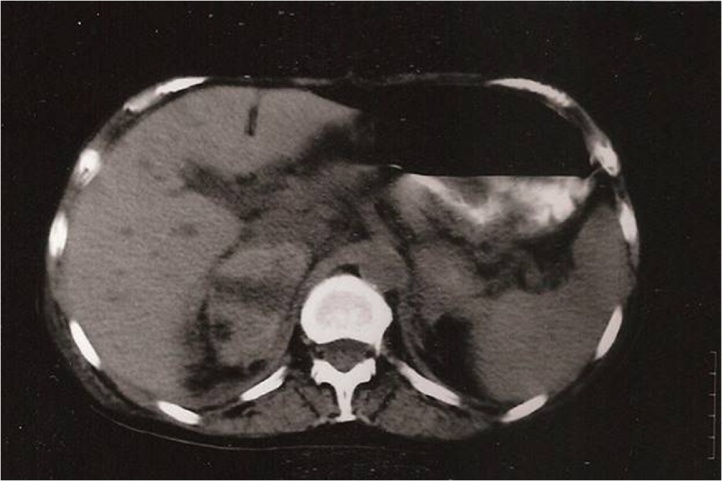

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT scan of case1 demonstrating a mixed attenuation mass in both adrenal glands. There is some preservation of normal adrenal enhancement in the periphery.

Colonic stenting is not commonly performed in our Institution for resectable colonic neoplasms. Therefore, the patient proceeded to an exploratory laparotomy. Findings were of a sigmoid tumor with no evidence of metastatic disease. In the view of an obstructed bowel, an abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis was performed. Postoperative course was uneventful until the fourth postoperative day when the patient developed a fever (37.8 C) with fatigue, lethargy and hypotension combined with hyponatriaemia (120mEq/lt) and relative hyperkalemia (4.7mEq/lt). There was clinical evidence of an acute deep venous thrombosis of the left subclavian, left jugularis internal and external, confirmed on ultrasound, even though the patient received DVT prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin from postoperative day one. A CT scan of the abdomen was performed at that point to exclude abdominal pathology. It showed bilateral enlargement of the adrenal glands (6 cm on the right and 4 cm on the left) with evidence of recent hemorrhage. Plasma cortisol was calculated and found to be very low (5 μg/dl) with an ACTH of 290 pg/ml. Further laboratory investigation with ELISA showed elevated levels of anticardiolipin antibodies – IgG 22.6 GPL (ref. 0–20 GPL) and IgM 35.5 MP L (ref 0–20 MPL).

The patient rapidly improved with the administration of a pulse dose of steroids. She also received anticoagulation treatment, initially with heparin and then with coumarin derivatives. Six months later, a follow-up CT scan showed normal adrenal glands. Steroids were successfully tapered, but anticoagulation treatment was continued for life (Fig. 2).

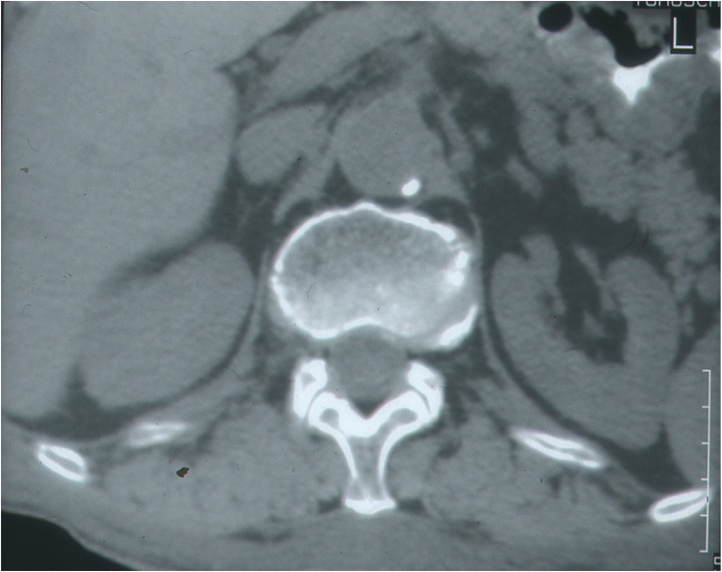

Fig. 2.

CT scan of patient in case 2 demonstrating evidence of recent haemorrhage.

2.2. Case 2

A male 72 year old patient was referred to our Colorectal Clinic with a diagnosis of intractable ulcerative colitis without extra- colonic manifestations. The patient received 40 mg prednisolone per day at home and continued to be severely symptomatic. He proceeded to have a total colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, J pouch and prophylactic loop ileostomy. The operation was uneventful and the patient received appropriate DVT prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin. Stress dose steroids were administered on induction of anaesthesia and were continued accordingly, as the patient was previously on long term steroid treatment for his ulcerative colitis.

He had a good recovery and resumed oral intake on the fourth postoperative day. On the fifth postoperative day, he developed acute deep venous thrombosis of the left lower limb, confirmed on Doppler ultrasound, and pulmonary embolism on CT Pulmonary Angiography. He was initially treated with heparin (30,000 IU i.v.) and continued with coumarin derivatives (Acenocumarol 2 mg/ day p.o.).

When steroid tapering was attempted postoperatively, the patient presented with clinical manifestations of adrenal insufficiency. He developed anorexia, lethargy, hypotension, hyponatriaemia; fever (T 39 C). A drop in the patient’s haemoglobin was noted (from 12 g/dL to 9.7 g/dL) without evidence of blood loss, haemolysis or sepsis. A CT scan of the abdomen showed enlargement of both adrenal glands with evidence of recent haemorrhage. Further laboratory investigations identified positive anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG 23.6 GPL, IgM 67.2 MPL).

His condition improved with hydrocortisone treatment (40 mg/day p.o.). Two months postoperatively, another attempt of hydrocortisone tapering led to a relapse of adrenal insufficiency. The patient resumed his previous hydrocortisone regime, until six months later when, after a successful tapering, hydrocortisone was stopped. The adrenal glands appeared normal on follow up imaging. Anticoagulation treatment with coumarin anticoagulants was continued for life (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Follow up abdominal CT scan of patient 2 post steroid treatment.

3. Discussion

Bilateral adrenal haemorrhage is a rare but potentially fatal condition, leading to the development of acute adrenal insufficiency, when at least 90% of the glands are injured. The adrenal gland has a distinct vascular anatomy; a high flow arterial network with an abrupt transition to a single vein which renders the gland vulnerable to haemorrhagic events.

The majority of post mortem studies indicate that the sequence of events is a thrombosis-mediated adrenal venous occlusion causing edema of the gland and secondary obstruction of the arterial supply resulting in a hemorrhagic infarction [2]. Espinosa et al retrospectively reviewed 86 cases of APS related adrenal haemorrhage. In 6 out of the 22 cases (27%) where histopathology report was available, it demonstrated spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage without vessel thrombosis. This alternative mechanism is usually seen in patients who have undergone surgery or are receiving anticoagulation [3]. The involvement of both glands may develop simultaneously or over a short period of time [4].

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an acquired thrombophilia characterized by multiple and recurrent venous and arterial thrombosis caused by circulating antibodies against a heterologous group of phospholipids [5]. The term antiphospholipid antibody is a generic term used for antibodies that specifically target _2GPI and prothrombin [6]. These include the anticardiolipin antibodies, the anti-β2-GPI, the lupus anticoagulant and an antibody implicated in false-positive VDRL testing [7]. The diagnosis of APS is based on both clinical and laboratory criteria (Updated Sapporo or Sydney Criteria) [8]. Clinical criteria include symptomatic venous arterial or small vessel thrombosis and laboratory criteria require positive detection of lupus anticoagulant (LA), anticardiolipin (aCL) antibody (IgG or IgM), or anti- 2GPI antibody (IgG or IgM).

Recent literature has demonstrated a causative relation between APS and primary adrenal insufficiency (AI), identifying it as its most common endocrine manifestation [9]. Spontaneous haemorrhagic infarction of the adrenal glands has been observed in patients with APS in the postoperative period. Signs and symptoms are non-specific and are easily confused with those of the underlying condition. Pain localized at the torso, flank, and lower chest or back, increased temperature and abdominal signs are the most consistent features. Neurological manifestations and hypotension are documented in a small fraction of patients. The two main laboratory features of adrenal haemorrhage are sudden drops in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and subsequent electrolyte changes suggestive of adrenal insufficiency; hyponatriaemia and hypokalemia.

How anticardiolipin and other antiphospholipid antibodies lead to thrombosis has not been unequivocally established. Monocytes and endothelial cells are activated by APL antibodies with anti-β2-glycoprotein-1 activity, inducing a hypercoagulant state. Recent studies indicate that complement activation plays a critical role [10], inducing thrombosis.

In several cases, surgery, inflammation or hormones have been identified as precipitating factors [11]. No large studies have yet been published on the risk of postoperative thrombosis in APL-positive individuals. Cancer associated APS has been sporadically described [12]. Recently, several case reports have correlated the circulating antiphospholipid antibodies with the well-established thrombotic predisposition of cancer patients [13].

The incidence of APS in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is not well defined. Vecchi et al. [14] found slightly increased levels of aCL antibodies in 6 out of 20 patients with inflammatory bowel disease associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic complications.

In our cases, after reviewing the patient’s past medical history, there was no evidence of previous APS associated clinical manifestations. It should be noted that antiphospholipid antibodies have been detected in asymptomatic healthy subjects [15]. The incidence ranges from 4.5% to 9.4% in the young population in various studies [16]. However, these numbers increase significantly with age. A study of 64 asymptomatic patients with a mean age of 81 years reported that 51.6% were positive for anticardiolipin antibodies of the IgG and IgM isotopes [17].

Early symptoms were vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli, while both patients were receiving appropriate prophylactic anticoagulation with fragmented heparin. Pain localized in the abdomen was present in both cases, a symptom particularly difficult to evaluate in the early postoperative period. Anorexia, asthenia, lethargy and hemoglobin drop without evidence of sepsis or clotting factors abnormalities completed the clinical picture of an Addisonian crisis.

Imaging is crucial for the differential diagnosis of this rare condition and computerised tomography is the examination of choice. Adrenal haematomas are usually described as round masses involving the glands or diffuse thickening of the adrenals with fat stranding [18]. Once diagnosis has been established, computerized tomography is also used to assess the state of the adrenal glands post treatment.

In both cases presented, CT scan of the abdomen showed evidence bilateral adrenal haemorrhage. Association of the clinical manifestations, identification of co-existing thromboembolic complications and a high index of suspicion led us to further laboratory investigations which confirmed the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency; low cortisol levels and the presence of APS; high IgG, aCL antibodies. Steroid replacement therapy resulted in progressive restoration of adrenal function. The optimal duration of anticoagulation is controversial, but it has been observed that patients with aPLs have a high risk of recurrence if anticoagulants are discontinued [19]. We opted for life-time anticoagulation in both cases.

Postoperative AI due to APS in a surgical patient is an uncommon diagnosis. Although AI is potentially fatal, prompt treatment with hydrocortisone and anticoagulants could result in a full recovery of adrenal function [20]. Therefore, we should highlight this potential diagnosis in a patient presenting with thrombosis and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency in the early post-operative period. Screening for lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies is warranted.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

There was no source of funding.

Ethical approval

According to the policy of Evaggelismos General hospital, no ethical approval was deemed necessary for publication of the submitted case report.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from both patients for publication of this case report.

Authors contribution

Miss Kolinioti and Mr Tsimaras were responsible for data collection, literature review and writing the paper. Mr Komporozos was responsible for the study concept and data interpretation. Mr Stravodimos was a co-writer and assisted the final editing of the paper.

Registration of research studies

researchregistry3888.

Guarantor

Miss Kolinioti and Mr Komporozos accept full responsibility for the work and controlled the decision to publish.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asherson R.A. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and other unusual manifestations of the catastrophic antiphospholipid (Asherson’s) syndrome. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2004;6(6):360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espinosa G., Santos E., Cervera R. Adrenal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic characteristics of 86 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82(2):106–118. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berneis K., Buitrago-Téllez C., Müller B., Keller U., Tsakiris D.A. Antiphospholipid syndrome and endocrine damage: why bilateral adrenal thrombosis? Eur. J. Haematol. 2003;71:299–302. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asherson R.A., Hughes G.R. Recurrent deep vein thrombosis and Addison’s disease in “primary” antiphospholipid syndrome. J. Reumetol. 1989;16(3):378–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannakopoulos Bill, Passam Freda, Ioannou Yiannis, Krilis Steven A. How we diagnose the antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood. 2009;113(January (5)):985–994. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGee G.S., Pearce W.H., Sharma L., Green D., Yao J.S. Antiphospholipid antibodies and arterial thrombosis. Case reports and a review of the literature. Arch. Surg. 1992;127(3):342–346. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420030116022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyakis S., Lockshin M.D., Atsumi T. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4(2):295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehdi A.A., Salti I., Uthman I. Antiphospholipid syndrome: endocrinologic manifestations and organ involvement. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2011;37(February (1)):49–57. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierangeli S.S., Girardi G., Vega-Ostertag M. Requirement of activation of complement C3 and C5 for antiphospholipid antibody mediated thrombophilia. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2120–2124. doi: 10.1002/art.21157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Groot P.G., Derksen R.H. Pathophysiology of the antiphospholipid syndrome. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:1854–1856. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tincani A., Taraborelli M., Cattaneo R. Antiphospholipid antibodies and malignancies. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010;9(4):200–202. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuckerman E., Toubi E., Golan T.D. Increased thromboembolic incidence in anticardiolipin-positive patients with malignancy. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;72(2):447–451. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vecchi M., Cattaneo M., De Francis R., Mannucci P.M. Risk of thromboembolic complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Study of haemostasis measurements. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 1991;21(2):165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02591637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vila P., Hernandez M.C., Lopez-Fernandez M.F. Prevalence, follow-up, and clinical significance of the anticardiolipin antibodies in normal subjects. Thromb. Haemost. 1994;72(2):209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi W., Krilis S.A., Chong B.H. Prevalence of lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies in a healthy population. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1990;20(3):231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1990.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manoussakis M.N., Tzioufas A.G., Silis M.P. High prevalence of anticardiolipin and other autoantibodies in a healthy elderly population. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1987;69(3):557–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacerdote M.G., Johnson P.T., Fishman E.K. CT of the adrenal gland: the many faces of adrenal hemorrhage. Emerg. Radiol. 2012;19(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s10140-011-0989-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulman S., Svenungsson E., Granqvist S. Anticardiolipin antibodies predict early recurrence of thromboembolism and death among patients with venous thromboembolism following anticoagulant therapy. Duration of Anticoagulation Study Group. Am. J. Med. 1998;104(4):332–338. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venrove M.A., Amoroso A. Reversible adrenal insufficiency after adrenal haemorrhage. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993;119(5):439. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]