Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia in the elderly affecting more than 5 million people in the U.S. AD is characterized by the accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) and Tau in the brain, and is manifested by severe impairments in memory and cognition. Therefore, removing tau pathology has become one of the main therapeutic goals for the treatment of AD. Tau (tubulin-associated unit) is a major neuronal cytoskeletal protein found in the CNS encoded by the gene MAPT. Alternative splicing generates two major isoforms of tau containing either 3 or 4 repeat (R) segments. These 3R or 4RTau species are differentially expressed in neurodegenerative diseases. Previous studies have been focused on reducing Tau accumulation with antibodies against total Tau, 4RTau or phosphorylated isoforms. Here, we developed a brain penetrating, single chain antibody that specifically recognizes a pathogenic 3RTau. This single chain antibody was modified by the addition of a fragment of the apoB protein to facilitate trafficking into the brain, once in the CNS these antibody fragments reduced the accumulation of 3RTau and related deficits in a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy. NMR studies showed that the single chain antibody recognized an epitope at aa 40-62 of 3RTau. This single chain antibody reduced 3RTau transmission and facilitated the clearance of Tau via the endosomal-lysosomal pathway. Together, these results suggest that targeting 3RTau with highly specific, brain penetrating, single chain antibodies might be of potential value for the treatment of tauopathies such as Pick’s Disease.

Keywords: Tauopathy, Pick’s Disease, Immunotherapy, Alzheimer’s Disease

INTRODUCTION

Neurodegenerative disorders with Tau accumulation are a common cause of dementia in the aging population. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Pick’s Disease (PiD), Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD) and Fronto-temporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) are examples of neurodegenerative disorders with Tau accumulation and are jointly referred to as “tauopathies” [7, 51, 98]. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia of the aging population and involves the accumulation of Aß and Tau [18, 27, 31]. There are currently more than 5 million AD patients in the United States and over 35 million patients worldwide [78]. This number is expected to double every 20 years due to the increased aging population. AD is the 6th leading cause of death in this country and the only cause of death among the top ten in the United States that cannot be prevented, cured or even slowed [78]. Based on mortality data from 2000-2008, death rates have declined for most major diseases while deaths from AD have risen 66% during the same period [3].

Alzheimer’s disease is associated with the progressive accumulation of Aß into oligomers and fibrils leading to synaptic loss, neuronal dysfunction and death [74]. In addition, intra-neuronal Tau aggregates form characteristic neurofibrillary tangles that contribute to neuronal death [58, 63, 74, 94]. Tau (tubulin-associated unit) is a major neuronal cytoskeletal protein found in the CNS encoded by the gene MAPT [19]. Alternative splicing can generate six different isoforms that can be distinguished based on the presence of 0, 1 or 2 N-terminal inserts and the presence or absence of repeat domain 2 (3R or 4R) [4, 12, 30]. These 3 repeat (3R) or 4 repeat (4R) Tau species are differentially expressed in neurodegenerative diseases with CBD and Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) primarily expressing the 4RTau isoform while PiD primarily expresses the 3RTau isoform [5, 7, 61, 91]. Interestingly, both 3R and 4RTau isoforms can be found accumulating in Alzheimer’s disease and Fronto-temporal Dementia (FTLD-tau, FTDP-17T) [21, 25, 48]. Pick’s disease is a less common cause of dementia and is characterized by cortical atrophy associated with neuronal loss, gliosis and the formation characteristic Pick bodies consisting of Tau-positive, globular, intra-neuronal inclusions in the neocortex and limbic system [21]. The clinical presentation with behavioral variant fronto-temporal dementia (bvFTD) is seen in PiD with fronto-temporal degeneration while fronto-parietal atrophy presents with apraxia. Mutations in the microtubule associated protein, (Tau, MAPT) account for the majority of familial PiD cases [48, 92]. Therefore, a number of strategies for targeting Tau for AD and other tauopathies has been proposed including small molecules preventing aggregation, anti-sense nucleotides to reduce tau expression and more recently immunotherapy [52].

Both active and passive immunotherapy approaches for the reduction of Tau in AD are under development [46, 101]; however, to date no immunization therapy has been specifically considered for PiD. Active immunization protocols utilize a peptide of Tau which then elicits a generalized immune response against all Tau species [67, 96]. Similarly, passive immunization strategies have been developed targeting either 4R Tau protein [46, 101] [38], or phosphorylated (p) Tau [9, 14, 41, 60, 62, 77]. Additional antibodies targeting p-Tau [62, 77] or acetylated Tau [57] have also been developed; however, none of these strategies differentiate among the splice variants of Tau that accumulate differentially in neurodegenerative disease. Furthermore, some studies with Tau knock-out mice have shown some potential deleterious effects from the total loss of Tau protein [16, 17, 33, 37]. Furthermore, down-regulation of t-Tau in oligodendrocytes by siRNA has been shown to reduce the expression of myelin basic protein (MBP) leading to reduced myelination [73]. Thus, targeting t-Tau for reduction may require additional consideration and more detailed studies to determine the safety threshold for t-Tau reduction. In this context, other antibodies have been developed targeting post-translationally modified Tau [6, 26, 42, 66]. However, since these antibodies mostly target 4RTau conformers or truncations they may not be suitable for the treatment of other tauopathies such as PiD which primarily involves the accumulation of 3R Tau. To date, there has been little or no effort to develop treatments specifically targeting the 3RTau.

To address this gap in the field, for this study, we developed a single chain (scFv) antibody directed against 3RTau with little to no cross-reactivity for 4RTau. This scFv antibody was further modified by the addition of the LDL receptor-binding domain of apolipoprotein B (apoB), which enhances brain penetration [81, 82, 84, 87, 89]. By NMR this scFv recognized an epitope consisting of aa 40-62 of 3RTau. We found that this scFv reduced 3RTau accumulation in a 3RTau transgenic (tg) mouse model of tauopathy and PiD [69] mice while also ameliorating the neuropathology and improving memory behavioral deficits. The development of a scFv directed specifically against the 3RTau species of Tau may be a useful immunotherapeutic option for PiD or other tauopathies that include the differential accumulation of the 3RTau splice variant of the aging population.

METHODS

Generation of 3RTau single chain antibody

Identification and isolation of the 3RTau scFv (hereafter referred as 3RT antibody) was performed by Viva Biotech (Shanghai, China). Briefly, His and avidin-tagged 3RTau(0N3R,352) and 4RTau(1N4R,412) were twice purified over a Ni-column and concentrated with an ultracentrifugation column to a concentration to 6.3 mg/ml and 11.2 mg/ml respectively. A phage display library was positively panned over 3RTau coated beads and negatively panned over 4RTau coated beads to generate several clones. These clones were sequenced and cloned into mammalian scFv expression cassettes for further analysis. Further analysis was performed with immunoblot and ELISA using the recombinant 3RTau and 4RTau proteins to identify the clone (5F10) that uniquely bound to 3RTau without cross-reacting to 4RTau. A control scFV was used that has no known binding to human or mouse tissue.

Large scale expression and purification of anti-3RT scFv

Human 3RTau scFv antibody was produced in HEK293 suspension cells using FreeStyle media following standard protocols. Briefly, 400ml HEK293 cells in FreeStyle 293 media (Gibco) were transfected with 40μg of pCAGG_3RTau_scFv expression construct, supplemented with 0.4mg of pSV40-T helper plasmid to facilitate replication of the expression construct in the cells, and with 0.4mg of a plasmid expressing a red fluorescent protein to monitor expression. 24 hours after transfection, cells were fed with 100ml EX-CELL media (SIAL). Remaining media was harvested 120 hours post-transfection at 500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the conditioned media was processed for purification.

A protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermofisher Halt™) and DTT (1mM) were added to 1L of media, followed by the filtration of the media using a 0.45 μm filter. The filtered media was then concentrated to 200mL using a Amicon® Ultra centrifugal filter from EMD Millipore. The concentrated media was dialyzed against 30mM HEPES, 100mM NaCl, pH 6.8 before passing it through a 6ml Resource Q column (GE Healthcare). In the next step, to remove the remaining impurities from the scFv, the flow through of the ResQ column was dialyzed against 30mM MES, 100mM NaCl, pH 5.5 and loaded onto a 6ml Resource S column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 30mM MES, 100mM NaCl, pH 5.5 and the scFv was eluted with a 100 - 1000mM NaCl linear gradient. Fractions containing pure scFv were pooled and dialyzed against 20mM sodium phosphate buffer, 100mM NaCl, pH 6.5 for subsequent NMR measurements.

3RTau expression and purification

A pETM-11 plasmid containing the human 3RTau(0N3R,352) sequence was transformed into E. coli (DE3) bacterial strain. The cells were grown at 37°C in 15N isotopically labeled M9 minimal media to an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.7. After induction with 0.8 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, 3RTau was expressed for 5h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in 20mM TrisHCl, 150mM NaCl, pH 7.6. The cells were lysed by sonication, after centrifugation at 18,000 rpm for 30 min, the 3RTau containing supernatant was heated to 95°C for 30 min. The solution was centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 30 min to remove precipitated protein. Subsequently, the supernatant was loaded onto a 5ml HisTrap column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20mM TrisHCl, pH 7.6, 300mM NaCl and 10mM imidazole. 3RTau was eluted with a 10 - 500mM imidazole linear gradient. The fractions containing 3RTau were pooled and dialyzed against 30mM TrisHCl, pH 7.6, 100mM NaCl, 0.5mM EDTA and 1mM DTT overnight. The His Tag was removed by TEV cleavage, and the cleavage reaction mixture was then dialyzed against a buffer containing 30mM MES, pH 6.5, 100mM NaCl and 1mM DTT and afterwards loaded onto a 6ml Resource S column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 30mM MES, 100mM NaCl, pH 6.5 and the protein was eluted with a 100 - 1000mM NaCl linear gradient. Fractions containing pure 3RTau were concentrated to 2 ml in a Amicon® Ultra centrifugal filter and finally passed through a Superdex 75 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with a buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 100mM NaCl, pH 6.5. The homogenous 3RTau fractions were pooled and used for NMR measurements.

NMR studies of Tau(0N3R,352) and scFv binding

NMR experiments were recorded on a Bruker Avance 800 MHz spectrometer with 5% D2O as lock solvent at 25 °C. The 2D 1H- 15N HSQC experiments were recorded on a 15 mM 15N labeled 3RTau(0N3R,352) sample, for the interaction measurement an approximate 1:1 molar ratio between 3RTau and scFv was used [70]. For the 2D 15N HSQC, 512 data points were recorded in the indirect dimension with 128 scans per point for free 3RTau and scFv-bound 3RTau.

NMR spectra were processed with NMRPipe [20] and analyzed with ccpNMR [97]. The relative peak intensities were obtained by dividing the peak volumes through the peak volume of residue 352 of 3RTau.

Construction of lentivirus vectors

The anti-3RTau scFv (3RT) cDNA was PCR amplified and cloned into the third-generation self-inactivating lentivirus vector plasmid [83] with the CMV promoter driving expression and the secretory signal from the human CD5 gene [43] producing the vector LV-s3RT. Addition of the ApoB 38 amino acid LDL-R binding domain was performed as previously described to generate LV-s3RT-ApoB. The lentivirus vector expressing the human wild-type α-syn and the control, LV-control have been previously described [85]. Lentiviruses were prepared by transient transfection in 293T cells [83].

Animal care

All experiments described were carried out in strict accordance with good animal practice according to NIH recommendations, and all procedures for animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) under protocol #S07221.

Transgenic mouse lines and injections of lentiviral vectors

For this study, mice over-expressing 3RTau(0N3R,352) [L266V,G272V] from the mThy1 promoter (Line 13) were utilized [69]. This model was selected because mice from this line develop intraneuronal 3RTau aggregates distributed throughout the neocortex and hippocampus similar to what has been described in Alzheimer’s disease and Pick’s disease.

To determine the effects of systemic injections of the lentivirus expressing 3RT, briefly as previously described [82] a total of 36 3RTau tg mice (n=12 LV-control, n=12 LV-3RT and n=12 LV-3RT-apoB) from 4 months old and n=6 non-tg mice (LV-control) were injected intra-peritoneal (IP) with 100μl of the lentiviral preparations (7.5×108 TU). Mice survived for 4 months after the lentiviral injection (8 months of age). Following NIH guidelines for the humane treatment of animals, mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate and flush-perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline.

Brains were removed and divided sagitally. The right hemibrain was post-fixed in phosphate-buffered 4% PFA (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 48 hours for neuropathological analysis, while the left hemibrain was snap-frozen and stored at −70°C for subsequent protein analysis.

Establishment of a neuronal cell line expressing 3RTau and scFv

For these experiments, we used the mouse cholinergic neuronal cell line Neuro2A (N2A) [80]. For all experiments, cells were infected with Lentivirus expressing 3RTau at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20. Cells were co-infected with LV-s3RT, LV-s3RT-ApoB or empty vector (LV-control). After infection, cells were incubated in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

To verify expression levels of 3RTau and the scFv in cells infected with the different LV vectors, N2A neurons were seeded onto poly L-lysine-coated glass coverslips, grown to 60% confluence and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 minutes. Coverslips were pre-treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 20 min and then incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against 3RTau (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) or V5 epitope (scFv) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) followed by biotinylated secondary antibody and reacted with diaminobenzidine. All sections were processed under the same standardized conditions. Control samples included: empty vector (referred hereafter as LV-control), and immunolabeling in the absence of primary antibodies. Cells were analyzed with a digital microscope Zeiss Imager.A2 (Zeiss, Cambridge, MA).

For co-culture analysis, 5 × 104 N2A cells were plated onto poly L-lysine coated glass coverslips or onto 12 well cell culture inserts containing a 0.4μm PET membrane (Fisher Scientific). Cultures were incubated separately for 6 hours to allow cells to attach and then co-cultured until analysis.

To verify the co-expression in neuronal cells co-infected with the different LV vectors, coverslips were double labeled with antibodies against 3RTau (Chemicon) and MAP2 (Millipore) as previously described [85]. Coverslips were air-dried, mounted on slides with anti-fading media (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and imaged with confocal microscope. An average of 50 cells were imaged per condition and the individual channel images were merged and analyzed with the Image J program to estimate the extent of co-localization between Tau and MAP2.

Immunocytochemical and neuropathological analyses

Analysis of Tau accumulation was performed in serially sectioned, free-floating, blind-coded vibratome sections from tg and non-tg mice treated with LV-3RT, LV-3RT-apoB and LV-control vectors [85]. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-V5 (Sigma) (scFv epitope), 3RTau (Chemicon), PHF1 (ThermoFisher) and t-Tau (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) antibodies [55], followed by biotinylated secondary antibody and reacted with diaminobenzidine. For each mouse, three sections were imaged with a digital Zeiss light microscope and the results were averaged and expressed as corrected optical density.

To determine the co-localization between 3RT scFv and cells in the CNS, 40 μm-thick vibratome sections were immunolabeled with the rabbit polyclonal antibody against the 3RT scFv (V5 epitope) and Map2 (neuronal dendritic marker, Chemicon), NeuN (neuronal nuclear marker, Millipore), GFAP (astrocyte marker, Chemicon) or Iba1 (microglia marker, Wako). The scFv immunoreactive structures were detected with the Tyramide Signal Amplification™-Direct (Red) system (NEN Life Sciences, Boston, MA) while the cellular specific markers were detected with the horse anti-mouse IgG fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) antibody (Vector, Burlingame, CA).

To determine the co-localization between the anti-3R Tau scFv (V5), LC3, 3RTau, and Rab5 markers double-labeling experiments were performed as previously described [54]. For this purpose, vibratome sections were immunolabeled with the rabbit polyclonal antibodies against 3R Tau, LC3 (Abcam, autophagy marker, San Francisco, CA), anti-V5, Rab5 (BD Transduction Laboratories, endosomal marker, San Jose, CA). All sections were processed simultaneously under the same conditions and experiments were performed twice in order to assess the reproducibility of results. Sections were imaged with a Zeiss 63X (N.A. 1.4) objective on a LSM800 digital confocal microscope (Zeiss, Cambridge, MA).

To determine if the scFv gene transfer ameliorated the neurodegenerative alterations associated with the expression of 3RTau, briefly as previously described [85], blind-coded, 40-μm thick vibratome sections from mouse brains fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were immunolabeled with the mouse monoclonal antibody against microtubule-associated protein-2, (MAP2, dendritic marker, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) [85]. After overnight incubation with the primary antibody, sections were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), transferred to SuperFrost slides (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and mounted under glass coverslips with anti-fading media (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Other sets of sections immunostained with antibodies for NeuN and GFAP were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody and reacted with diaminobenzidine. All sections were processed under the same standardized conditions. The immunolabeled blind-coded sections were serially imaged with the LSCM and analyzed with the Image 1.43 program (NIH, Bethesda, MD), as previously described [85]. For each mouse, a total of three sections from the hippocampus and three from the cortex were analyzed and for each section, four fields in the frontal cortex and hippocampus were examined. For MAP2, results were expressed as percent area of the neuropil occupied by immunoreactive dendrites. For NeuN, sections were analyzed by the dissector method using Stereo-Investigator System (MBF Bioscience) and the results were expressed as numbers per mm3. For GFAP, sections were analyzed by light microscopy with a digital Zeiss microscope and expressed as corrected optical density. All sections were processed simultaneously under the same conditions and experiments were performed twice in order to assess the reproducibility of results [55].

Behavioral Testing

The open field locomotor test was used to determine basal activity levels of study subjects (total move time) during a 15 min session as previously described [80]. Briefly, spontaneous activity in an open field (25.5 × 25.5 cm) was monitored for 15 min using an automated system (Truscan system for mice; Coulbourn Instruments). Animals were tested within the first 2– 4 h of the dark cycle after being habituated to the testing room for 15 min. The open field was illuminated with a lamp equipped with a 25 W red bulb. Time spent in motion was automatically collected 3 times for 5 min each using TruScan software. Data were analyzed for both the entire 15 min session and for each of the 5 min time blocks.

For PPI the protocol was adapted from Papaleo et al. [64]. Briefly, mice treated with LV-control, LV-3RT and LV-3RT-apoB were placed in the startle chambers for a 5-min acclimation period with a 65 dB(A) background noise. Animals were then exposed to a series of trial types. The inter trial interval (ITI) was 5–60 s. One trial type measured the response to no stimulus (baseline movement), and another one measured the startle stimulus alone (acoustic amplitude), which was a 40 ms 120 dB sound burst. Other five trial types were acoustic prepulse plus acoustic startle stimulus trials. Prepulse tones were 20 ms at 70, 75, 80, 85, and 90 presented 100 ms before the startle stimulus. PPI was calculated and expressed as % inhibition.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed blind coded and in triplicate. Values in the figures are expressed as means ± SEM. To determine the statistical significance, values were compared by using the one-way ANOVA with posthoc Dunnet when comparing the scFv treated samples to LV-control treated samples. The Tukey-Krammer test was used when comparing the 3RTau tg treated with LV-control vs LV-3RT or LV-3RT-apoB and denoted by #. The Dunnet’s test was used when comparing the non-tg control vs any of the 3RTau tg groups. The differences were considered to be significant if p values were less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Development of single chain antibody that selectively recognize 3RTau in vitro and in tissues from patients with AD and PiD

We recently developed FaB antibody fragments that specifically targeted the 3RTau and do not recognize the 4RTau protein. Full length 3RTau(0N3R,352) and 4RTau(1N4R,412) proteins were expressed and purified for screening of a large phage display scFv antibody expression library. The phage display scFv library was positively screened over immobilized 3RTau protein while negatively screened over immobilized 4RTau protein multiple times until 5 clones were isolated that bound selectively to the 3RTau protein. These 5 clones were further characterized by ELISA binding efficiency and narrowed down to a single clone that showed selective binding to the 3RTau protein with little to no cross-reactivity to the 4RTau protein.

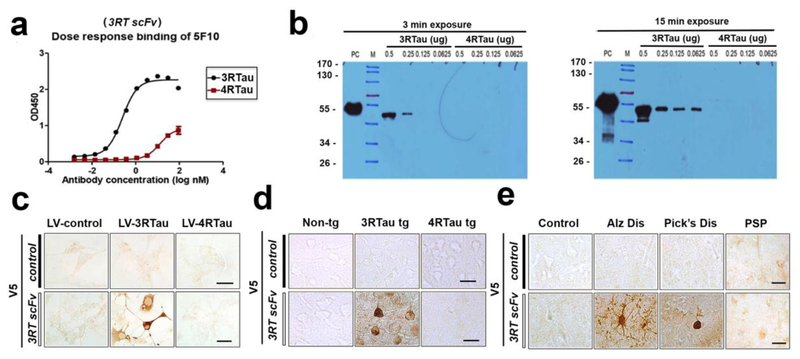

To confirm that the scFv antibody selectively binds to 3RTau, ELISA and immunoblot were performed (Figure 1a,b). ELISA with bound 3RTau or 4RTau protein and increasing concentrations of the 3RTau scFv (here after referred as 3RT) antibody showed significant selectivity for the 3RTau protein at femtomolar concentrations of antibody (Figure 1a). Immunoblot analysis (Figure 1b) confirmed the specificity and sensitivity of the 3RT for 3RTau protein over the 4RTau protein. 2-fold dilutions of 3RTau and 4RTau recombinant protein were loaded onto a gel and probed with the 3RT. The 3RT antibody detected nanogram quantity of 3RTau protein with no detectable cross-reactivity of the 4RTau protein. Thus, the 3RT antibody is specific and sensitive for the 3RTau protein with little to no detectable cross-reactivity for the very similar 4RTau protein.

Figure 1.

Characterization of a novel 3RTau specific single chain antibody. Phage display libraries were positively and negatively panned across recombinant 3RTau and 4RTau protein until a single clone was identified that bound only to 3RTau and did not bind 4RTau. (a) ELISA assay with increasing concentrations of the 3RT antibody against immobilized 3R or 4RTau protein (2 μg/ml) EC50 = 0.064nM. (b) Immunoblot confirmed the specificity and sensitivity of the 3RT antibody (0.1 μg/ml) for 3RTau protein. Further confirmation of specificity was performed by immunohistochemistry analysis with an antibody against the V5 epitope tag on the scFv with (c) N2A neuronal cells infected lentivirus expressing 3RTau or 4RTau, (d) 3RTau tg, 4RTau tg (PS19) or non-tg mouse brain sections, and (e) sections from control, Alzheimer’s, Pick’s, and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy disease patients. The control scFV has no known binding to human or mouse tissues.

Next, the 3RT antibody was used for immunohistochemistry on in vitro mouse N2A neuronal cells infected with lentivirus overexpressing either 3RTau or 4RTau. Immunostaining with the 3RT antibody was restricted to the neurons overexpressing the 3RTau protein (Figure 1c), while control mouse adult neurons that only express 4RTau were not labeled. The immunostaining specificity was further confirmed with sections from non-tg, 3rTau tg and 4RTau-tg (PS19) mice where immunoreactivity with the 3RT was observed only in 3rTau tg mice whereas the control scFv antibody showed no immunoreactivity in any of the sections (Figure 1d). Finally, the 3RT antibody was tested with sections from the frontal cortex of PSP, AD, PiD and control patients. Compared to the control scFv, the 3RT antibody immunoreacted with neurofibrillary tangles in the AD and the Pick bodies in PiD cases, but no immunoreactivity was detected in control human brain or PSP brain which is composed primarily of 4RTau (Figure 1e) suggesting a selectivity for 3RTau present in both human Pick’s disease and AD.

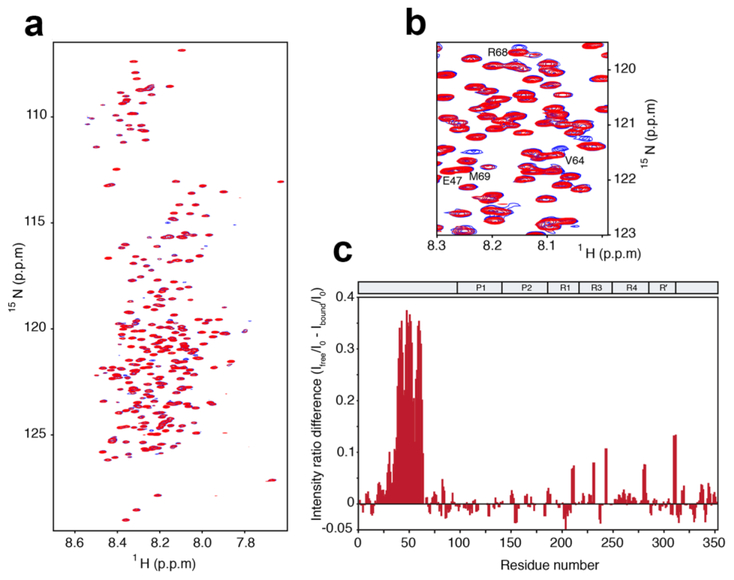

NMR investigation of scFv binding to tau352

The interaction between scFv and 3RTau(0N3R,352) was further studied by NMR spectroscopy. For this purpose, 3RTau and 3RT antibody were recombinantly expressed in E. coli and HEK293 cells, respectively. 2D 1H- 15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra were recorded on 3RTau in the absence and presence of 3RT antibody (Figure 2a). The HSQC of 3RTau has a narrow chemical shift dispersion indicative of an intrinsically disordered protein (Figure 2a). The addition of 3RT single chain antibody at an approximately equimolar ratio lead to the appearance of several new peaks with no changes in chemical shifts of the remaining signals in the 3RTau spectrum (Figure 2a,b), suggesting strong antibody binding. These additional signals in the 1H- 15N HSQC spectrum of the 3RTau scFv complex appear due to changes in the chemical environment upon 3RT binding and are located near the signals of Val64, Arg68 and Met69 (Figure 2b). Furthermore, the presence of 3RT scFv resulted in the attenuation of signal intensity for resonances of residues 40-62 (Figure 2c), caused by the increase in molecular weight upon scFv binding.

Figure 2.

3RTau interacts with 3RT antibody through a short amino acid sequence in the N-terminal domain. (a) 1H- 15N HSQC spectra of 3RTau in absence (red) and presence of 3RT (blue) at an approximate equimolar ratio. (b) A region of the 1H- 15N HSQC spectra showing several additional peaks upon 3RT binding. (c) Relative signal intensity difference profile of 3RTau in the free and 3RT bound state. Signal intensities were determined from the two HSQC spectra shown in (a). The decrease in signal intensity in N-terminal part of 3RTau in the presence of 3RT is due to the increase in molecular weight upon 3RT binding.

The 3RT-apoB retains activity and reduces the accumulation of 3RTau in an in vitro neuronal model

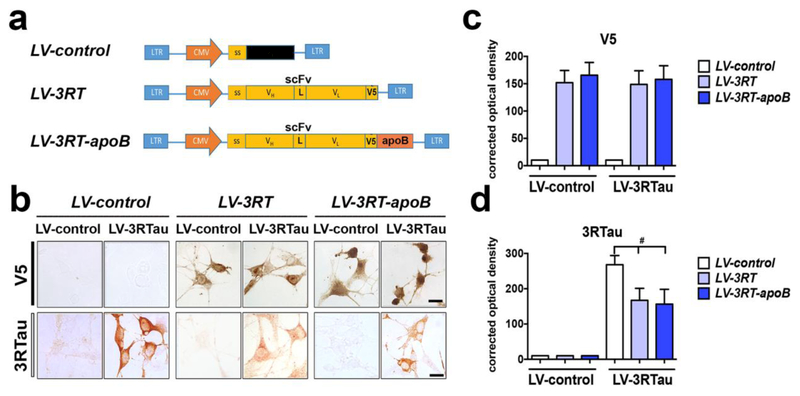

For cell-based proof-of concept studies, we first constructed a viral vector expressing the recombinant 3RT antibody with the brain penetrating sequence (apoB). For this purpose, the scFv cDNA, designated 3RT, was cloned and expressed in a lentiviral vector (LV) system as previously described [80, 81]. Three LVs were prepared, namely- LV-control (empty vector), LV-3RT (expressing the single chain antibody alone) and LV-3RT-apoB (expressing the single chain antibody with ApoB) (Figure 3a). The use of the scFv antibody allows for increased brain penetration over full size monoclonal antibodies; however, to further increase the BBB trafficking, permanence and cell penetration of the 3RT antibody in the CNS, we have added a peptide designated apoB. We previously showed the 38 amino acid LDL-receptor binding domain from apoB (apoB38), when fused to a cargo protein, is sufficient to transport proteins across the blood-brain barrier to penetrate into the neuronal side [81, 82, 86, 87, 89]. We fused the apoB38 peptide to the C-terminus along with a V5 epitope tag for easier detection. Finally, a secretory signal sequence was added to the 5’ end of each scFv construct to allow for secretion of the protein from expressing cells (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

A lentiviral vector expressing the 3RT antibody reduces the accumulation of 3RTau in neurons in vitro. (a) The 3RT antibody was cloned into the 3rd generation lentivirus vector with the addition of the CD5 secretory signal (ss) and the V5 epitope tag (V5) to generate LV-s3RT. This vector was further modified by the addition of the apoB brain transport peptide to generate LV-s3RT-apoB. (b) N2A neuronal cells co-infected with the 3RT antibody expressing vectors and a 3RTau expressing vector were stained for the 3RT antibody (V5) and for the 3RTau protein. Coverslips were analyzed for (c) V5 and (d) 3RTau staining pixel intensity and quantified by corrected optical density. # indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to cells expressed co-infected with LV-3RTau and LV-control. One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey-Kramer. Scale bar represents 10μm.

To examine the ability of the 3RT antibody to reduce the accumulation of 3RTau in an in vitro neuronal model, we co-infected N2A neuronal cells with a LV over-expressing 3RTau along with either LV-control, LV-3RT or LV-3RT-apoB. As demonstrated by the detection of the V5 tag, both scFv coding vectors expressed equivalent amounts of the 3RT antibody (Figure 3b,c) and were able to reduce the accumulation of 3RTau in the neuronal cells (Figure 3b,d) to a comparable extent, indicating that the addition of the apoB fragment did not interfere with the antibody activity. In contrast, control vector (LV-control) did not appear to have an effect on the neuronal accumulation of 3RTau (Figure 3b,d).

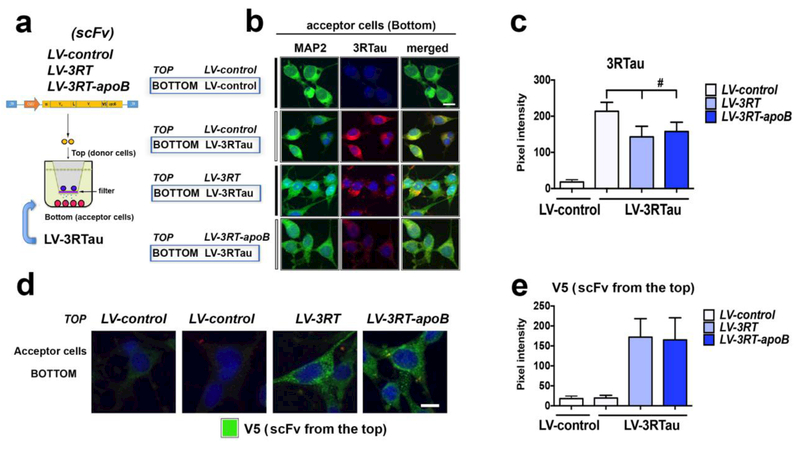

Passive immunization of the scFv involves delivery of the antibody to neuronal cells that are already accumulating 3RTau protein. To model this in vitro, 3RTau expressing neuronal cells were separated from 3RT scFv producer cells by a 0.4μm membrane that allows only the passage of proteins but prevents the contact of the cells (Figure 4a). The 3RT scFV is expressed and secreted from the producer cells following infection with the lentivirus vector. The LV-3RT, LV-3RT-apoB and LV-control expressing cells were cultured in the top chamber (donor cells) and the LV-3RTau expressing cells were cultured in the bottom chamber (acceptor cells) (Figure 4a). Compared to the LV-control, both the 3RT and 3RT-apoB antibodies produced by cells in the top of the chamber, reduced the accumulation of 3RTau in neuronal cells in the bottom of the chamber (Figure 4b,c). Analysis of the cells in the lower chamber showed similar levels of uptake of the 3RT and 3RT-apoB antibodies (Figure 4d,e). Taken together, these two studies show that addition of the apoB BBB transport tag does not affect the activity or binding of the 3RT antibody for 3RTau and the virus vector expressed 3RT is able to reduce the accumulation of 3RTau in neuronal cells both in an autocrine and exocrine manner.

Figure 4.

A lentiviral vector expressing the 3RT antibody reduces the accumulation of 3RTau in neurons in vitro. (a) Diagram of the two-chamber co-culture system of N2A neuronal cells with the lower chamber of cells infected with the LV-3RTau and the upper chamber infected with the 3RT antibody expressing vectors. (b) Lower chamber coverslips were fixed and double immunostained with antibodies against 3RTau (red) and the neuronal MAP2 protein (green). (c) Relative fluorescence was analyzed to determine the level of 3RTau. (d) Lower chamber coverslips were immunostained for against V5 (3RT antibody) (green). (e) Relative fluorescence was analyzed to determine the level of V5. # indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to LV-control by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey-Kramer. Scale bar represents 10μm.

The 3RT-apoB single chain antibody penetrates into the CNS and reduces the accumulation of 3RTau in a transgenic mouse model of Tauopathy

Given that we have shown that addition of the apoB increases BBB trafficking and cellular penetration of the scFv [81, 82, 86, 87, 89] without affecting activity, next we wanted to ascertain the efficacy of the 3RT antibody in vivo. For this purpose, we utilized a 3rTau tg mouse model developed in our laboratory. This mouse model of PiD and tauopathies over-expresses 3RTau under the pan-neuronal promoter mThy1 [69]. The 3rTau tg mice show abnormal accumulation of 3RTau in the neocortex and limbic system with neurodegeneration, formation of PiD and tangle-like inclusions, and behavioral deficits [69]. Non-tg and 3rTau tg mice received a single IP injection of the LV-3RT-apoB, LV-3RT or LV-control and after 4 months were evaluated behaviorally, biochemically and neuropathologically. Intraperitoneal delivery of the lentivector primarily transduces cells of the liver and the spleen where the transgene can be expressed and secreted into the bloodstream [89] thus the liver and spleen become the depot organs expressing the recombinant protein. Four months after the IP injections, mice were sacrificed and the levels of scFv and Tau in the brain were determined by immunoblot and immunohistochemistry.

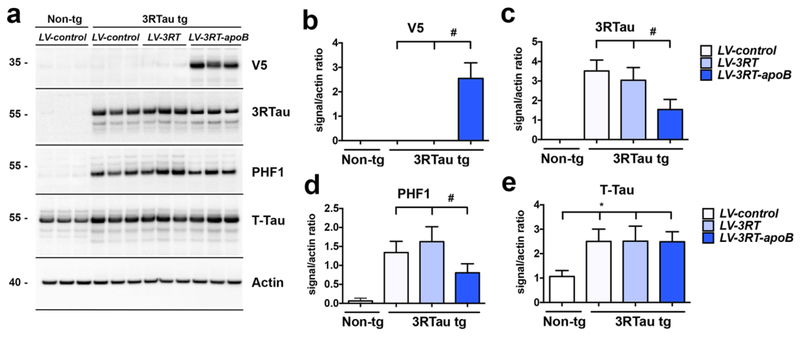

Immunoblot analysis with an antibody against V5 (to detect the epitope tag added to the scFv lentiviral constructs), showed the presence of the 3RT antibody as a band at approximately 35 kDa only in the brain homogenates from the 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB but not in those treated with LV-control or LV-3RT (Figure 5a,b). 3RTau, PHF1 and T-Tau were detected as bands at approximately 55 kDa. 3RTau was detected only in the brain homogenates of the 3RTau tg mice; no band was observed in the non-tg mice (Figure 5a). Moreover, compared to non-tg, the 3RTau tg mice displayed increased levels of PHF1 and t-Tau immunoreactive bands (Figure 5a). When comparing to 3RTau tg mice that received LV-control or LV-3RT injections, only treatment with LV-3RT-apoB resulted in a reduction in the levels of 3RTau (Figure 5a,c) and PHF1 (Figure 5a,d) but did not alter levels of t-Tau (Figure 5a,e).

Figure 5.

The 3RT-apoB antibody reduces Tau accumulation in the brain. (a) Representative, immunoblot analysis of brain homogenates from non-tg and 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT, LV-3RT-apoB or LV-control showing levels of Tau proteins: 3RTau, p-Tau (PHF1), and total Tau (T-Tau) as well as the level of the 3RT scFv protein (V5) with ß-actin as a loading control. Image analysis of pixels of (b) V5, (c) 3RTau, (d) PHF1, and (e) T-Tau immunoreactivity analyzed as ratio to ß-actin signal. * indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to non-tg mice by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnet’s test. # indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to 3R Tau tg mice with or without treatment by LV-3RT by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey-Kramer. For analysis, 3RTau tg LV-control (n=12); LV-3RT (n=12); LV-3RT-apoB (n=12) and non-tg mice LV-control (n=6).

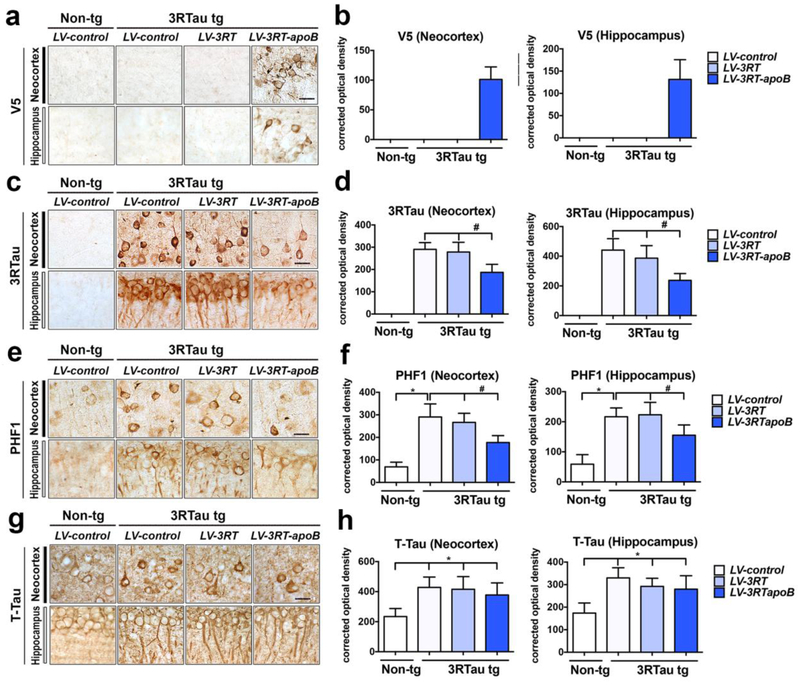

Consistent with the Western blot, immunocytochemical analysis with the anti-V5 antibody demonstrated the presence of positive cells in the neocortex and hippocampus in the 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB but not in those treated with LV-control or LV-3RT alone (Figure 6a,b). Levels of 3RTau were reduced by approximately 37% in the neocortex (deeper layers) and 47% in the hippocampus (CA1) of 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB when comparing to tg mice treated with LV-control or LV-3RT (Figure 6c,d). The 3RTau tg mice also accumulate p-Tau that is detectable with the PHF1 antibody in neurons in the neocortex and hippocampus (Figure 6e,f). We observed a 41% reduction in the levels of p-Tau immunoreactivity in the neocortex and 36% in the hippocampus of 3RTau tg mice treated with the LV-3RT-apoB when compared to tg mice treated with either LV-3RT or LV-control (Figure 6e,f). In contrast, we did not observe a reduction in t-Tau protein in the 3R Tau tg mice with treatment of either LV-3RT or LV-3RT-apoB vectors (Figure 6g,h), suggesting that the 3RT-apoB was selectively reducing the abnormal accumulation of 3RTau and p-Tau without significantly affecting the overall levels of Tau.

Figure 6.

Systemic delivery of the 3RT antibody with a lentiviral vector reduces the accumulation of 3RTau in the brain of transgenic mice. 4-month-old 3RTau tg and non-tg mice received a single i.p. injection of LV-3RT, LV-3RT-apoB or LV-control and were sacrificed 4 months later for analysis. (a,b) Immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies against the V5 tag to detect the 3RT scFv in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of non-tg and 3RTau tg mice. (c,d) Immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies against 3RTau in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of non-tg and 3RTau tg mice. (e,f) Immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies against phosphor-Tau (PHF-1) in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of non-tg and 3RTau tg mice. (g,h) Immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies against total Tau (T-Tau) in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of non-tg and 3RTau tg mice. (b,d,f,h) Immunoreactivity semi-quantified and expressed as corrected optical density of sections. * indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to non-tg mice by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnet’s test. # indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to 3R Tau-tg mice treated with LV-control by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey-Kramer. Scale bar represents 25μm. For analysis, 3RTau tg LV-control (n=12); LV-3RT (n=12); LV-3RT-apoB (n=12) and non-tg mice LV-control (n=6).

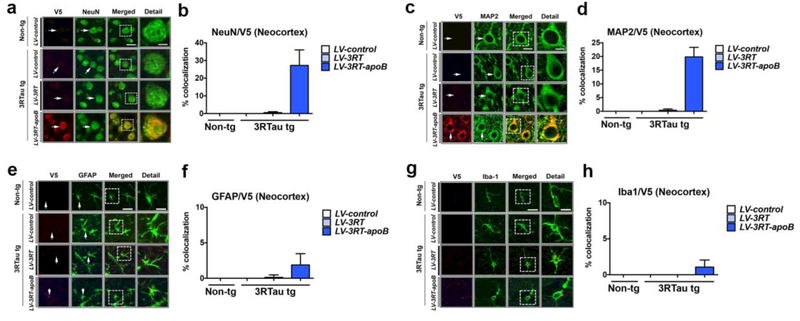

In order to characterize the type of cells capturing the 3RT antibody, double labeling studies were performed with neuronal (NeuN and MAP2) and glial cell markers (GFAP and Iba1). These studies showed that the V5 tagged 3RT antibody co-localized to about 27% of NeuN (Figure 7a,b) and 20% of MAP2 (Figure 7c,d) positive pyramidal neurons in the deeper layers of the neocortex in the 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB, with no co-localization detected in those mice treated with LV-control or LV-3RT (Figure 7a,b for NeuN and 7c,d for MAP2). Similar double labeling studies with glial markers revealed that the V5 tagged antibody co-localized to approximately 2% of GFAP positive astroglial cells (Figure 7e,f) and 1% of the Iba1 positive microglial cells (Figure 7g,h) in the deeper layers of the neocortex in the 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB, with no co-localization detected in those mice treated with LV-control or LV-3RT (Figure 7e,f for GFAP and 7g,h for Iba1).

Figure 7.

The 3RT-apoB antibody co-localizes with neurons in the brain of 3RTau tg mice. Representative images of double immunocytochemical labeling in the neocortex of non-tg and 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT, LV-3RT-apoB and LV-control with antibodies to V5 (red, 3RT epitope tag) and the neuronal markers (a) NeuN or (c) MAP2, astrocyte marker (e) GFAP, and microglia marker (g) Iba1 imaged analyzed with the laser scanning confocal microscope. Analysis of % cells showing co-localization between V5 (3RT) and (b) NeuN, (d) MAP2, (f) GFAP, and (h) Iba1. Scale bar represents 10μm, and 5μm in detail figure. For analysis, 3RTau tg LV-control (n=12); LV-3RT (n=12); LV-3RT-apoB (n=12) and non-tg mice LV-control (n=6).

Addition of the apoB sequence to the 3RT scFv facilitates cellular uptake and degradation of 3RTau via an endosomal-lysosomal pathway

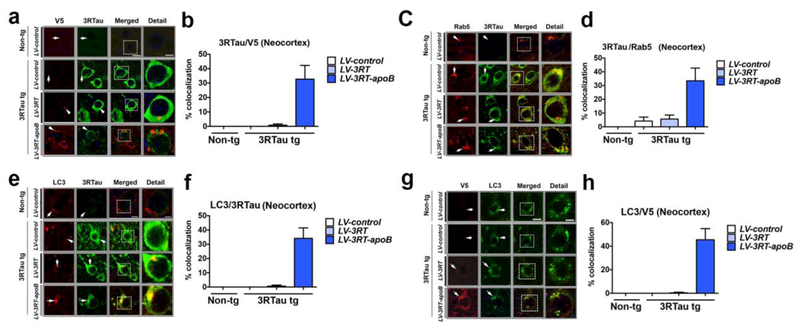

So far, our results indicate that the 3RT-apoB penetrated the CNS and neuronal cells reducing the accumulation of 3RTau and p-Tau in the neocortex and hippocampus of the 3RTau tg mice. However, it is unclear if the 3RT-apoB antibody engaged its target, namely 3RTau. For this purpose, additional double labeling experiments were performed with antibodies against 3RTau protein and V5 (3RT scFv). Confocal microscopy showed that compared to LV-control or LV-3RT, in 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB, the antibody (V5, red channel) co-localized with 33% of the neurons displaying 3RTau immunoreactivity (FITC channel) (Figure 8a,b). Little to no signal above background level was detected in mice treated with LV-control or LV-3RT (Figure 8a,b). Interestingly, in mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB, the antibody (V5) co-localized intra-neuronally with 3RTau in granular structures in cell bodies, and the overall levels of 3RTau in these neurons appeared reduced compared to cells that did not display the co-localization with the 3RT antibody (Figure 8a) (see detail to the right of dotted box).

Figure 8.

The 3RT-apoB antibody co-localizes with 3RTau and targets 3RTau to the early endosome. (a) Representative double immunoflourescent images in the neocortex of non-tg and 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT, LV-3RT-apoB and LV-control with antibodies to V5 (red, 3RT epitope tag) and 3RTau (green) analyzed with the laser scanning confocal microscope. (c) Double immunoflourescent analysis with 3RTau (green) and Rab5 (red). (e) Representative double immunoflourescent images in the neocortex with LC3 (red) and 3RTau (green) and analyzed with the laser scanning confocal microscope. (g) Representative double immunoflourescent images of sections labeled with antibodies against V5 (red, 3RT epitope tag) and LC3 (green). (b,d,f,h) Analysis of % cells showing co-localization. Scale bar represents 10μm, and 5μm in detail figure. For analysis, 3RTau tg LV-control (n=12); LV-3RT (n=12); LV-3RT-apoB (n=12) and non-tg mice LV-control (n=6).

We have previously shown that the apoB fragment enables the intra-cellular trafficking of the scFv antibodies via the LDL-R at the surface of neurons which in turn facilitates trafficking via the ESCRT pathway [81]. Given that we found the antibody co-localizing with punctate structures in the neuronal cytoplasm, this suggests that the 3RTau and antibody might be taken up in endosomes for clearance and degradation. To further investigate this possibility, sections were double labeled with antibodies against 3RTau and the early endosomal marker Rab5. Confocal microscopy studies showed that in 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB, Rab5 (red channel) co-localized with approximately 36% of the neurons displaying 3RTau immunoreactivity (FITC channel) (Figure 8c,d). Only minimal co-localization (less than 5% of the cells) between Rab5 and 3RTau was detected in the 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-control or LV-3RT (Figure 8c,d).

These findings suggest that the 3RT antibody/3RTau complex might be endocytosed for degradation. To this end, sections were double labeled with antibodies against the autophagosomal marker LC3 and 3RTau. Confocal microscopy analysis showed that in 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB, LC3 (red channel) co-localized with approximately 32% of the neurons showing 3RTau immunostaining (FITC channel) (Figure 8e,f). Only minimal (less than 1% of the cells) co-localization between LC3 and 3RTau was observed in tg mice treated with LV-control or LV-3RT (Figure 8e,f). Similarly, LC3 (FITC channel) and V5 (red channel) co-localized in granular intra-cellular elements in about 45% of the neuronal cells in 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB, but not in mice treated with LV-3RT or LV-control (Figure 8g,h). Together, these results suggest that facilitated by the apoB fragment, the 3RT antibody and 3RTau were transported in the endosomal compartment for lysosomal degradation.

The 3RT-apoB antibody reduces neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits in the 3RTau transgenic mouse model of tauopathy

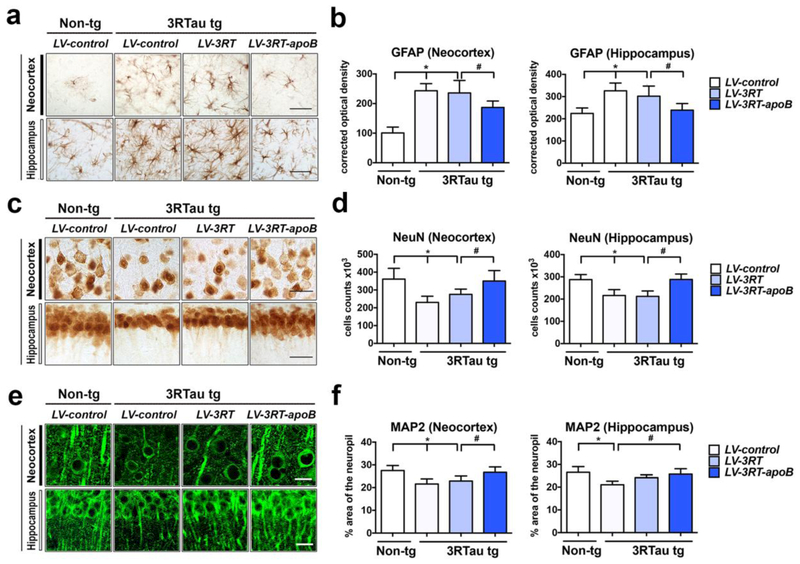

To determine if the reduction in 3RTau was accompanied by amelioration of the neurodegenerative phenotype, sections from non-tg and 3RTau tg mice were immunolabeled with antibodies against the astroglial marker- GFAP and the neuronal markers- NeuN and MAP2. As previously reported [69], immunostaining with the antibody against GFAP showed that compared to the LV-control treated non-tg mice, LV-control treated 3RTau tg mice displayed increased astrogliosis in the neocortex and hippocampus (Figure 9a,b). In contrast, treatment with LV-3RT-apoB but not LV-3RT reduced astrogliosis in the 3RTau tg mice (Figure 9a,b). Likewise, compared to the LV-control non-tg mice, LV-control treated 3RTau tg mice displayed decreased NeuN-positive neuronal cells in the neocortex and CA1 of the hippocampus (Figure 9c,d). In contrast, treatment with LV-3RT-apoB but not LV-3RT ameliorated the loss of NeuN positive neurons in the neocortex and hippocampus of the 3RTau tg mice (Figure 9a,d). We have previously shown that MAP2- a dendritic protein is a sensitive marker of neuronal damage [85]. Compared to LV-control treated non-tg mice the LV-control or LV-3RT treated 3RTau tg mice displayed a 29% reduction in the area of neuropil covered by MAP2 immunreactive dendrites (Figure 9e,f). However, treatment with the LV-3RT-apoB prevented the loss of the MAP2 immunoreactive dendrites in the neocortex and hippocampus (Figure 9e,f). This data supports the possibility that reduction of 3RTau protein by delivery of the 3RT antibody ameliorates the neurodegenerative damage and neuro-inflammation in the 3R Tau tg mice.

Figure 9.

Delivery of the 3RT-apoB antibody reduces neurodegeneration in the 3RTau tg model. 4-month-old 3RTau tg and non-tg mice received a single i.p. injection of LV-3RT, LV-3RT-apoB or LV-control and were sacrificed 4 months later for analysis. The neocortex and hippocampus were immunostained with antibodies against the (a) astrocyte glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), (c) neuronal marker NeuN, (e) and dendritic marker MAP2 (green). (b) GFAP immunoreactivity expressed as corrected optical density of sections. (d) Stereological estimates (dissector method) of total NeuN-positive neuronal counts in the frontal cortex. (f) Image analysis of % area of the neuropil covered by MAP2 post-synaptic processes. * indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to non-tg mice by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnet’s test. # indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey-Kramer. Scale bar represents 20μm. For analysis, 3RTau tg LV-control (n=12); LV-3RT (n=12); LV-3RT-apoB (n=12) and non-tg mice LV-control (n=6).

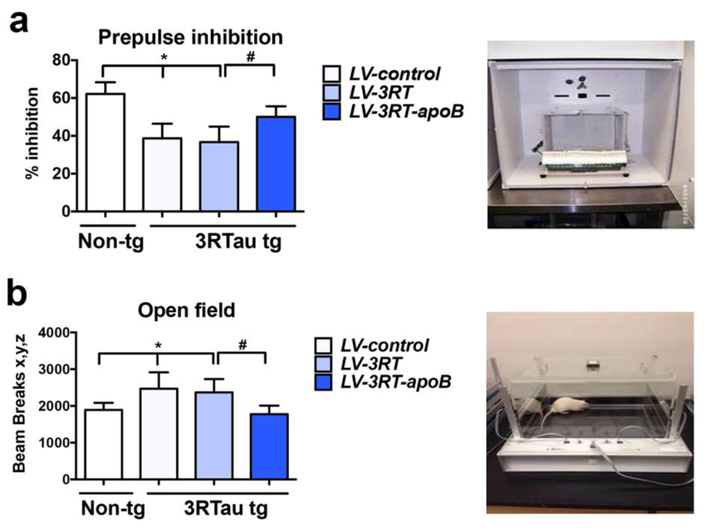

Finally, we wanted to determine if the reduced neurodegenerative pathology was associated with improvements in behavioral deficits. We performed some preliminary water maze testing on these mice, but we found that at the age tested (7-9 mos) mice begin losing vision acuity so the Morris Water maze is no longer suitable for memory testing. We have previously shown the 3RTau tg mice have deficits in the pre-pulse inhibition assay and decreased habituation in a novel environment [69]. Mice were tested in a pre-pulse inhibition paradigm which evaluates the pre-attentive processes that operates outside of awareness and is used in animal models of neurodegeneration marked by an inability to block irrelevant information in cognitive domains. In this assay, compared to the LV–control, 3RTau tg mice showed an up to 45% reduction in percent inhibition compared to LV-control treated non-tg mice. In contrast, 3RTau tg mice treated with the LV-3RT-apoB mice behaved similarly to the non-tg mice; whereas tg mice treated with the LV-3RT did not show any improvement (Figure 10a). To determine if treatment of the 3RTau tg mice with the LV-3RT or LV-s3RT-apoB could ameliorate the learning deficits of the 3RTau tg mice, we examined the mice in the open field for number of beam breaks. As expected the LV-control treated 3RTau tg mice failed to habituate to the novel environment compared to LV-control treated non-tg mice. In contrast, 3RTau tg mice treated with the LV-3RT-apoB mice behaved similarly to the non-tg mice; whereas tg mice treated with the LV-3RT did not show any improvement (Figure 10b). Thus, treatment of 3RTau tg mice with the 3RT-apoB antibody is able to ameliorate the behavioral deficits present in this model of tauopathy.

Figure 10.

Systemic delivery of the 3RT-apoB with a lentiviral vector ameliorated behavioral deficits in the 3RTau tg mouse. Mice were assessed in the (a) Prepulse inhibition (PPI) test, compared to non-tg mice treated with LV-control, the 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-control displayed reduced % of inhibition, in contrast mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB displayed normal levels of % inhibition and (b) in the open field test, 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-control or 3LV-RTau alone, displayed hyperactivity while 3RTau tg mice treated with LV-3RT-apoB displayed levels of activity similar to non-tg controls. * indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to non-tg mice by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnet’s test. # indicates statistical significance p < 0.05 compared to 3R Tau-tg mice treated with LV-3RT by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey-Kramer.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we generated a single chain antibody targeted specifically to the 3-repeat tau isoform for the intent of reducing the accumulation of 3RTau specifically without affecting the total or 4RTau levels. While other investigators have developed svFvs against the 2N Tau splice variant [60], p-Tau [49] or the GSK3ß phosphorylation region at the N-terminus of Tau [38], we specifically targeted the 3-repeat Tau. NMR studies confirmed the specificity of the single chain and showed that it binds to an epitope between aa 40-62 of 3RTau(0N3R, 352). Delivery of this specific antibody to a mouse model overexpressing 3RTau showed significant reduction in 3RTau accumulation accompanied by improvements in behavioral deficits and markers of neurodegeneration including neuronal loss and astrogliosis. Further evidence suggests that the antibody may have been able to promote clearance of 3RTau via the endosomal system and target 3RTau for degradation in lysosomes thus reducing the cell-to-cell propagation of tau aggregates in the brain. Taken together, brain targeted delivery of the single chain antibody specific for 3RTau may prove beneficial in restoring the physiological balance of neuronal tau isoforms during pathological conditions when 3RTau is in excess.

Analysis of the 3RT antibody binding to the 3RTau(0N3R) protein by NMR showed specific targeting for the antibody to amino acids 40-62 located at the N-terminus of the Tau protein while the repeat regions differentiating the 3RTau and 4RTau are located in the C-terminus of the protein. In contrast, the N-terminal repeat regions are located at the 3RT scFv binding domain. Immunohistochemistry with the antibody on human brain samples from AD and PiD patients showed specific binding to plaques and Pick bodies suggesting the scFv is binding to 3RTau protein (Pick’s disease) [5, 7, 61]. The 0N form of 3R Tau is only expressed in the fetal brain [5] and since the 3RT scFv did not detect any protein in the control brain or PSP brain, this suggests that the 3RT scFv is binding specifically to a pathological conformational form of 3RTau. However, the specific binding characteristics of the scFv as a conformational specific antibody will have to be further explored.

In studies in the 3RTau tg mouse, we observed reduced accumulation of 3RTau and p-Tau in the CNS; however, we did not detect an overall reduction in t-Tau. It is not entirely clear why we observe a reduction in only the p-Tau; however, this same phenomenon of reduction in p-Tau (and not t-Tau) coupled with improved NeuN staining and behavioral outcomes has been observed for another antibody targeted to C-terminus of Tau [15]. Our 3RT antibody is targeted to the N-terminus region of Tau. Although the human and mouse 3RTau are nearly identical in the C-terminus where the repeat regions are located, the N-terminus, with the projection domain, is divergent with a stretch of 11 additional amino acids present in the human form and various amino acid changes located directly in the epitope binding domain. Thus, the lack of overall t-Tau protein may reflect a lack of binding to the endogenous murine Tau protein. Further characterization of the 3RT antibody will determine this.

Tau truncation products found independent of phosphorylation events are also detected in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and oligomers. These Tau cleavage events can occur by several proteases throughout the protein, but the majority occur by only two proteases at three locations. An N-terminal (Leu43) cleavage by Calpain in the projection domain and another cleavage at the C-terminal domain (Val229) generates a 17kDa fragment [65]. This fragment has been shown to induce neuronal apoptosis in vitro [13]. A C-terminal cleavage by Caspase 3 at the Asp421 also generates a pathogenic fragment [26]. This product has been reported to initiate the generation of oligomers and NFT and even neuronal apoptosis [26, 68]. Of these two truncation products, the calpain cleavage product (17kDa Tau) would theoretically not be recognized by the 3RT scFv due to the proteolytic cleavage event in the antibody recognition domain. However, future studies will have to be performed to determine if this is in fact true.

Our approach is different to others in that instead of targeting total Tau, 4RTau or phosphorylated Tau species we are targeting specifically 3RTau which is relevant to the pathogenesis of AD, PiD and other unusual tauopathies. While others have used active vaccination with peptides that elicit antibodies against various Tau species [45, 95] or with monoclonal antibodies against t-Tau [46, 101] or p-tau species [11, 14, 96] [9, 41, 60, 62, 77] that display low or variable degrees of CNS trafficking we chose to develop single chain antibodies selectively targeting 3RTau fused with a fragment of LDL-R binding protein (apoB) that enhances brain penetration. Antibody therapy directed at CNS targets has shown promise in animal models and in early clinical trials, however most studies show that of the injected dose, only approximately 1% reaches the CNS with the rest of the protein probably degraded by proteases in the blood-stream or taken up by other clearance organs such as the liver, kidney or resident [8, 87]. Antibodies targeted to Tau have been shown to cross the blood-brain barrier and co-localize with Tau in the CNS [6, 9]. Uptake of these IgG antibodies into the CNS occurs by the low expressing FcRn [39, 40, 72, 75, 102]. In contrast, targeting the LDL-R receptor with a peptide that docks at the receptor binding site can be accomplished with a 38-amino acid sequence from Apolipoprotein B [56, 89]. Recently, we showed that insertion of the 38 amino acid ApoB LDL-R into a single chain Fc region antibody could significantly enhance delivery of antibodies across the BBB by almost 10-fold more than an antibody without receptor mediated transcytosis [81]. In addition to enhanced CNS delivery, the addition of the ApoB LDL-R domain provides a unique cellular uptake mechanism [81]. The advantage of using single chain antibodies is the use of large phage or yeast display libraries to select for unique epitopes of interest [2], and since they lack Fc they are less prone to elicit inflammatory or undesired immunological reactions.

The ratio between 3R and 4RTau in the neuron is regulated by alternative splicing of the MAPT gene such that exon 10 with 4RTau containing exon 10. The normal adult human brain contains approximately equal molar amounts of 3R:4RTau [28, 29, 47]. Disruption of this ratio can be pathogenic [35, 36, 90] resulting in alterations in normal filament assembly and favoring aggregation [1]. Therefore, a normal 50:50 balance of 3R:4RTau in the healthy brain is necessary, and targeting the 3R tau in a disease that is caused by an accumulation of 3R tau will ideally restore the balance of the normal ratio of 3R:4RTau without reducing only total Tau.

Among the many functions attributed to Tau protein in axons, directing axonal transport has been the subject of recent interest with respect to tau pathology. Anterograde and retrograde transport of cargos in the axon are mediated by the kinesin and dynein motors interacting with microtubules [23, 93]. Tau regulates axon transport polarity by interacting with microtubules and competing for binding of these cargo transport motors [22, 44]. Recently it was reported that the ratio of 3RTau and 4RTau in the axon can alter the direction of transport of APP-containing cargos, with higher levels of 3RTau favoring anterograde transport of APP toward the cell body and inhibiting the retrograde transport of those same cargos [50]. Thus, reducing 3RTau protein could potentially decrease the accumulation of APP and/or Aß in synaptic termini and increase degradation in the cell body.

Although Tau is primarily a neuronal cytoskeletal protein, expression occurs a low level in oligodendrocytes [53, 59] and it has been shown to accumulate in astrocytes and microglia in tauopathies including Alzheimer’s disease, PSP and Pick’s disease where it is found predominately in the 3RTau isoform [24, 34]. Interestingly we observed little to no accumulation of the 3RT scFv in GFAP astrocytes or Iba-1 microglia. This is consistent with previous findings with ApoB tagged proteins targeted for CNS therapies where we also observed primarily neuronal accumulation with little to no astrocyte or microglia accumulation [87] and probably is due to the low level of LDL-R expression on these cells [86].

Tau protein is subjected to numerous post-translational modifications in the CNS, including phosphorylation, O-glycosylation and acetylation [79]. Abnormal post-translational modifications have been linked to increased aggregations and Tau tangles. Pharmacologic approaches to block the phosphorylation of Tau through the Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 have been attempted in the clinic; however, side effects from well-known inhibitors such as lithium including small therapeutic windows and peripheral organ toxicity have slowed progress [32]. Tau pathology occurs intra-neuronally; however, recent evidence suggests that the protein can also propagate from cell-to-cell [79]. Tau oligomers or aggregates injected into wild-type or Tau transgenic mice show propagation and Tau aggregates from the site of injection and in vitro cultures show spread of Tau from cell-to-cell [79]. Thus, Tau protein can exist outside of the cell and is a viable target for therapeutics. In fact, Tau has been observed in exosomes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies suggesting this might be a mechanism for cell-to-cell propagation [71, 76, 99, 100]. Therefore, several strategies for targeting Tau in AD and other tauopathies have been proposed, including small molecules preventing aggregation; anti-sense nucleotides to reduce tau expression; and more recently immunotherapy. The mechanisms through which the single chain antibodies against 3RTau might work are not completely understood, however some possibilities that they might block Tau cell to cell propagation, reduce aggregation and increase Tau aggregate clearance via microglia [10]. In this regard, we found that the single chain antibody reduced the cell-to-cell propagation of 3RTau in an in vitro model system and double labeling studies in the tg mice suggests that the apoB fragment facilitated the 3RT antibody and 3RTau transport in the endosomal compartment for lysosomal degradation via autophagy. We have shown a similar mechanism of action for single chain antibodies targeting α-synuclein in models of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's Disease [81, 88].

In summary, the approach of utilizing the phage display library to develop antibodies specific for very slight differences in proteins may be a method worth investigating for tauopathies as well as other neurodegenerative diseases. Many pathological conditions occur from single point mutations or post-translational modification [98] that could be recognized and differentiated from wild-type or normal proteins through the use of positive and negative panning of phage display libraries. This approach allows for specific tailoring of targeting the antibody to the pathological splice variants without affecting the normal physiological protein. We show here proof-of-principle that this approach can work for tauopathies and may be applied to other diseases as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by NIH grants AG5131, AG018440, AG051839. HEK293 antibody production was performed by the VBCF Protein Technologies Facility (www.vbcf.ac.at).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams SJ, DeTure MA, McBride M, Dickson DW, Petrucelli L (2010) Three repeat isoforms of tau inhibit assembly of four repeat tau filaments. PLoS One 5: e10810 Doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0010810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad ZA, Yeap SK, Ali AM, Ho WY, Alitheen NB, Hamid M (2012) scFv antibody: principles and clinical application. Clinical & developmental immunology 2012: 980250 Doi 10.1155/2012/980250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer's Association (2015) Latest Facts and Figures Report.

- 4.Andreadis A, Brown WM, Kosik KS (1992) Structure and novel exons of the human tau gene. Biochemistry 31: 10626–10633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arendt T, Stieler JT, Holzer M (2016) Tau and tauopathies. Brain Res Bull 126: 238–292 Doi 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asuni AA, Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM (2007) Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau conformers in a tangle mouse model reduces brain pathology with associated functional improvements. J Neurosci 27: 9115–9129 Doi 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2361-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballatore C, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2007) Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 663–672 Doi 10.1038/nrn2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boado RJ, Lu JZ, Hui EK, Sumbria RK, Pardridge WM (2013) Pharmacokinetics and brain uptake in the rhesus monkey of a fusion protein of arylsulfatase a and a monoclonal antibody against the human insulin receptor. Biotechnology and bioengineering 110: 1456–1465 Doi 10.1002/bit.24795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boutajangout A, Ingadottir J, Davies P, Sigurdsson EM (2011) Passive immunization targeting pathological phospho-tau protein in a mouse model reduces functional decline and clears tau aggregates from the brain. J Neurochem 118: 658–667 Doi 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07337.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braczynski AK, Schulz JB, Bach JP (2017) Vaccination strategies in tauopathies and synucleinopathies. J Neurochem 143: 467–488 Doi 10.1111/jnc.14207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bright J, Hussain S, Dang V, Wright S, Cooper B, Byun T, Ramos C, Singh A, Parry G, Stagliano N et al. (2015) Human secreted tau increases amyloid-beta production. Neurobiol Aging 36: 693–709 Doi 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caillet-Boudin ML, Buee L, Sergeant N, Lefebvre B (2015) Regulation of human MAPT gene expression. Molecular neurodegeneration 10: 28 Doi 10.1186/s13024-015-0025-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canu N, Dus L, Barbato C, Ciotti MT, Brancolini C, Rinaldi AM, Novak M, Cattaneo A, Bradbury A, Calissano P (1998) Tau cleavage and dephosphorylation in cerebellar granule neurons undergoing apoptosis. J Neurosci 18: 7061–7074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collin L, Bohrmann B, Gopfert U, Oroszlan-Szovik K, Ozmen L, Gruninger F (2014) Neuronal uptake of tau/pS422 antibody and reduced progression of tau pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain 137: 2834–2846 Doi 10.1093/brain/awu213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Congdon EE, Lin Y, Rajamohamedsait HB, Shamir DB, Krishnaswamy S, Rajamohamedsait WJ, Rasool S, Gonzalez V, Levenga J, Gu J et al. (2016) Affinity of Tau antibodies for solubilized pathological Tau species but not their immunogen or insoluble Tau aggregates predicts in vivo and ex vivo efficacy. Molecular neurodegeneration 11: 62 Doi 10.1186/s13024-016-0126-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson HN, Cantillana V, Jansen M, Wang H, Vitek MP, Wilcock DM, Lynch JR, Laskowitz DT (2010) Loss of tau elicits axonal degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 169: 516–531 Doi 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson HN, Ferreira A, Eyster MV, Ghoshal N, Binder LI, Vitek MP (2001) Inhibition of neuronal maturation in primary hippocampal neurons from tau deficient mice. Journal of cell science 114: 1179–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Strooper B, Karran E (2016) The Cellular Phase of Alzheimer's Disease. Cell 164: 603–615 Doi 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.del CAA, Iqbal K (2005) Tau-induced neurodegeneration: a clue to its mechanism. J Alzheimers Dis 8: 223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. Journal of biomolecular NMR 6: 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickson DW, Kouri N, Murray ME, Josephs KA (2011) Neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration-tau (FTLD-tau). J Mol Neurosci 45: 384–389 Doi 10.1007/s12031-011-9589-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixit R, Ross JL, Goldman YE, Holzbaur EL (2008) Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science 319: 1086–1089 Doi 10.1126/science.1152993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Encalada SE, Goldstein LS (2014) Biophysical challenges to axonal transport: motor-cargo deficiencies and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Biophys 43: 141–169 Doi 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrer I, Lopez-Gonzalez I, Carmona M, Arregui L, Dalfo E, Torrejon-Escribano B, Diehl R, Kovacs GG (2014) Glial and neuronal tau pathology in tauopathies: characterization of disease-specific phenotypes and tau pathology progression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73: 81–97 Doi 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forrest SL, Kril JJ, Stevens CH, Kwok JB, Hallupp M, Kim WS, Huang Y, McGinley CV, Werka H, Kiernan MC et al. (2018) Retiring the term FTDP-17 as MAPT mutations are genetic forms of sporadic frontotemporal tauopathies. Brain 141: 521–534 Doi 10.1093/brain/awx328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gamblin TC, Chen F, Zambrano A, Abraha A, Lagalwar S, Guillozet AL, Lu M, Fu Y, Garcia-Sierra F, LaPointe N et al. (2003) Caspase cleavage of tau: linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 10032–10037 Doi 10.1073/pnas.1630428100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Y, Tan L, Yu JT, Tan L (2017) Tau in Alzheimer's disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Curr Alzheimer Res: Doi 10.2174/1567205014666170417111859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goedert M, Jakes R (1990) Expression of separate isoforms of human tau protein: correlation with the tau pattern in brain and effects on tubulin polymerization. EMBO J 9: 4225–4230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA (1989) Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 3: 519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo T, Noble W, Hanger DP (2017) Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol 133: 665–704 Doi 10.1007/s00401-017-1707-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haass C, Selkoe DJ (2007) Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 8: 101–112 Doi 10.1038/nrm2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Habib A, Sawmiller D, Li S, Xiang Y, Rongo D, Tian J, Hou H, Zeng J, Smith A, Fan S et al. (2017) LISPRO mitigates beta-amyloid and associated pathologies in Alzheimer's mice. Cell Death Dis 8: e2880 Doi 10.1038/cddis.2017.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Harada A, Oguchi K, Okabe S, Kuno J, Terada S, Ohshima T, Sato-Yoshitake R, Takei Y, Noda T, Hirokawa N (1994) Altered microtubule organization in small-calibre axons of mice lacking tau protein. Nature 369: 488–491 Doi 10.1038/369488a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higuchi M, Ishihara T, Zhang B, Hong M, Andreadis A, Trojanowski J, Lee VM (2002) Transgenic mouse model of tauopathies with glial pathology and nervous system degeneration. Neuron 35: 433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong M, Zhukareva V, Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, Wszolek Z, Reed L, Miller BI, Geschwind DH, Bird TD, McKeel D, Goate A et al. (1998) Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science 282: 1914–1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A et al. (1998) Association of missense and 5'-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393: 702–705 Doi 10.1038/31508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikegami S, Harada A, Hirokawa N (2000) Muscle weakness, hyperactivity, and impairment in fear conditioning in tau-deficient mice. Neurosci Lett 279: 129–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ising C, Gallardo G, Leyns CEG, Wong CH, Stewart F, Koscal LJ, Roh J, Robinson GO, Remolina Serrano J, Holtzman DM (2017) AAV-mediated expression of anti-tau scFvs decreases tau accumulation in a mouse model of tauopathy. The Journal of experimental medicine 214: 1227–1238 Doi 10.1084/jem.20162125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Israel EJ, Patel VK, Taylor SF, Marshak-Rothstein A, Simister NE (1995) Requirement for a beta 2-microglobulin-associated Fc receptor for acquisition of maternal IgG by fetal and neonatal mice. J Immunol 154: 6246–6251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Israel EJ, Taylor S, Wu Z, Mizoguchi E, Blumberg RS, Bhan A, Simister NE (1997) Expression of the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, on human intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology 92: 69–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ittner A, Bertz J, Suh LS, Stevens CH, Gotz J, Ittner LM (2015) Tau-targeting passive immunization modulates aspects of pathology in tau transgenic mice. J Neurochem 132: 135–145 Doi 10.1111/jnc.12821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jicha GA, Bowser R, Kazam IG, Davies P (1997) Alz-50 and MC-1, a new monoclonal antibody raised to paired helical filaments, recognize conformational epitopes on recombinant tau. J Neurosci Res 48: 128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones NH, Clabby ML, Dialynas DP, Huang HJ, Herzenberg LA, Strominger JL (1986) Isolation of complementary DNA clones encoding the human lymphocyte glycoprotein T1/Leu-1. Nature 323: 346–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanaan NM, Morfini G, Pigino G, LaPointe NE, Andreadis A, Song Y, Leitman E, Binder LI, Brady ST (2012) Phosphorylation in the amino terminus of tau prevents inhibition of anterograde axonal transport. Neurobiol Aging 33: 826 e815–830 Doi 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kontsekova E, Zilka N, Kovacech B, Novak P, Novak M (2014) First-in-man tau vaccine targeting structural determinants essential for pathological tau-tau interaction reduces tau oligomerisation and neurofibrillary degeneration in an Alzheimer's disease model. Alzheimers Res Ther 6: 44 Doi 10.1186/alzrt278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kontsekova E, Zilka N, Kovacech B, Skrabana R, Novak M (2014) Identification of structural determinants on tau protein essential for its pathological function: novel therapeutic target for tau immunotherapy in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 6: 45 Doi 10.1186/alzrt277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kosik KS, Orecchio LD, Bakalis S, Neve RL (1989) Developmentally regulated expression of specific tau sequences. Neuron 2: 1389–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kovacs GG (2015) Invited review: Neuropathology of tauopathies: principles and practice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41: 3–23 Doi 10.1111/nan.12208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krishnaswamy S, Lin Y, Rajamohamedsait WJ, Rajamohamedsait HB, Krishnamurthy P, Sigurdsson EM (2014) Antibody-derived in vivo imaging of tau pathology. J Neurosci 34: 16835–16850 Doi 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2755-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lacovich V, Espindola SL, Alloatti M, Pozo Devoto V, Cromberg LE, Carna ME, Forte G, Gallo JM, Bruno L, Stokin GB et al. (2017) Tau Isoforms Imbalance Impairs the Axonal Transport of the Amyloid Precursor Protein in Human Neurons. J Neurosci 37: 58–69 Doi 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2305-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ (2001) Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 1121–1159 Doi 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li C, Gotz J (2017) Tau-based therapies in neurodegeneration: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16: 863–883 Doi 10.1038/nrd.2017.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.LoPresti P, Szuchet S, Papasozomenos SC, Zinkowski RP, Binder LI (1995) Functional implications for the microtubule-associated protein tau: localization in oligodendrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92: 10369–10373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Crews L, Spencer B, Adame A, Patrick C, Trejo M, Ubhi K, Rohn TT et al. (2011) Passive immunization reduces behavioral and neuropathological deficits in an alpha-synuclein transgenic model of Lewy body disease. PLoS One 6: e19338 Doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0019338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 55.Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Sagara Y, Sisk A, Mucke L (2000) Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science 287: 1265–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Masliah E, Spencer B (2015) Applications of ApoB LDLR-Binding Domain Approach for the Development of CNS-Penetrating Peptides for Alzheimer's Disease. Methods in molecular biology 1324: 331–337 Doi 10.1007/978-1-4939-2806-4_21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Min SW, Chen X, Tracy TE, Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang C, Shirakawa K, Minami SS, Defensor E, Mok SA et al. (2015) Critical role of acetylation in tau-mediated neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits. Nat Med 21: 1154–1162 Doi 10.1038/nm.3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mucke L, Selkoe DJ (2012) Neurotoxicity of amyloid beta-protein: synaptic and network dysfunction. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2: a006338 Doi 10.1101/cshperspect.a006338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muller R, Heinrich M, Heck S, Blohm D, Richter-Landsberg C (1997) Expression of microtubule-associated proteins MAP2 and tau in cultured rat brain oligodendrocytes. Cell and tissue research 288: 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nisbet RM, Van der Jeugd A, Leinenga G, Evans HT, Janowicz PW, Gotz J (2017) Combined effects of scanning ultrasound and a tau-specific single chain antibody in a tau transgenic mouse model. Brain 140: 1220–1230 Doi 10.1093/brain/awx052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olney NT, Spina S, Miller BL (2017) Frontotemporal Dementia. Neurol Clin 35: 339–374 Doi 10.1016/j.ncl.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Otvos L Jr., Feiner L, Lang E, Szendrei GI, Goedert M, Lee VM (1994) Monoclonal antibody PHF-1 recognizes tau protein phosphorylated at serine residues 396 and 404. J Neurosci Res 39: 669–673 Doi 10.1002/jnr.490390607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Overk CR, Masliah E (2014) Pathogenesis of synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body disease. Biochemical pharmacology 88: 508–516 Doi 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Papaleo F, Lipska BK, Weinberger DR (2012) Mouse models of genetic effects on cognition: relevance to schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology 62: 1204–1220 Doi 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park SY, Ferreira A (2005) The generation of a 17 kDa neurotoxic fragment: an alternative mechanism by which tau mediates beta-amyloid-induced neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 25: 5365–5375 Doi 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1125-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patterson KR, Remmers C, Fu Y, Brooker S, Kanaan NM, Vana L, Ward S, Reyes JF, Philibert K, Glucksman MJ et al. (2011) Characterization of prefibrillar Tau oligomers in vitro and in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 286: 23063–23076 Doi 10.1074/jbc.M111.237974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pedersen JT, Sigurdsson EM (2015) Tau immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease. Trends Mol Med 21: 394–402 Doi 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rissman RA, Poon WW, Blurton-Jones M, Oddo S, Torp R, Vitek MP, LaFerla FM, Rohn TT, Cotman CW (2004) Caspase-cleavage of tau is an early event in Alzheimer disease tangle pathology. J Clin Invest 114: 121–130 Doi 10.1172/JCI20640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]