Abstract

Neurons are highly dependent on mitochondrial function, and mitochondrial damage has been implicated in many neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. Here we show that axonal mitochondria are necessary for neuropeptide secretion in Caenorhabditis elegans and that oxidative phosphorylation, but not mitochondrial calcium uptake, is required for secretion. Oxidative phosphorylation produces cellular ATP, reactive oxygen species, and consumes oxygen. Disrupting any of these functions could inhibit neuropeptide secretion. We show that blocking mitochondria transport into axons or decreasing mitochondrial function inhibits neuropeptide secretion through activation of the hypoxia inducible factor HIF-1. Our results suggest that axonal mitochondria modulate neuropeptide secretion by regulating transcriptional responses induced by metabolic stress.

Keywords: mitochondria, neuropeptide secretion, hypoxia, reactive oxygen species, Caenorhabditis elegans

MUTATIONS that perturb mitochondrial function are linked to several neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders (Johri and Beal 2012; Pease and Segal 2014; Pickrell and Youle 2015; Kerr et al. 2017; Krench and Littleton 2017). For these reasons, there is significant interest in defining the cell biological mechanisms through which mitochondria regulate neuronal function and development. Mutations (or drug treatments) that impair mitochondrial function cause widespread cellular and developmental defects. Given these pleiotropic effects, identifying the precise molecular pathways through which mitochondria regulate neural development and behavior has proved challenging. One strategy to circumvent this problem has been to analyze mutants in which mitochondria transport or localization in axons is blocked (Guo et al. 2005; Verstreken et al. 2005; Kang et al. 2008; Ma et al. 2009; Russo et al. 2009). In these transport mutants, mitochondrial defects are restricted to axons, whereas other cellular functions of mitochondria remain intact.

Analysis of mitochondria transport mutants suggests mitochondria can act through multiple pathways to influence neuronal function and development. Several aspects of neuronal function are especially dependent upon cellular energy stores (e.g., maintenance of membrane potential, intracellular transport to axons and dendrites, and membrane-fusion and endocytosis reactions). In addition to producing ATP, mitochondria also act as an intracellular calcium store; consequently, axonal mitochondria alter the duration of presynaptic calcium transients, thereby regulating neurotransmitter release at synapses (Werth and Thayer 1994; Tang and Zucker 1997; Billups and Forsythe 2002; Medler and Gleason 2002). Finally, mitochondria promote axon regeneration following injury (Rawson et al. 2014; Han et al. 2016). Given the widespread effects of mitochondria on cellular physiology, it is likely that additional mechanisms will be discovered that link mitochondria to neuronal function and development.

To further investigate how they affect neuronal function, we asked if axonal mitochondria regulate secretion of neuropeptides. Neuropeptides are a chemically diverse set of neuromodulators that are recognized by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). GPCRs typically bind their cognate ligands with extremely high affinity and stimulate production of second messengers through G-protein activation of enzymatic targets. Consequently, neuropeptides (and other metabotropic agonists) often produce relatively long-lasting signals over very large spatial domains. Thus, we hypothesized that axonal mitochondria could alter global behavioral states by regulating neuropeptide secretion. Here we show that axonal mitochondria promote neuropeptide secretion and that they do so by regulating a cell-autonomous stress response to hypoxia.

Materials and Methods

Caenorhabditis elegans strains and drug assays

Strains were maintained at 20° as described (Brenner 1974). The wild-type reference strain was N2 Bristol. Full descriptions of all alleles can be found at http://www.wormbase.org. Strains used in this study are as follows:

KP8730 ric-7(nu447) V; nuEx1853[psnb-1::UNC-116-GFP- TOMM-7].

KP8714 nuIs183[punc129::NLP-21-YFP] III KP8717 nuIs183 III; nuEx1851[punc-129::UNC-116-tagRFP-TOMM-7].

KP8724 nuIs183 III; ric-7(nu447) V KP8725 nuIs183 III; ric-7(nu447) V; nuEx1851[punc-129::UNC-116-tagRFP-TOMM-7].

KP9044 nuSi187[punc-129::NLP-21-mNeonGreen] IV.

KP9082 nuSi187 IV; nuEx1851[punc-129::UNC-116- tagRFP-TOMM-7].

KP9083 nuSi187 IV; ric-7(nu447) V; nuEx1851[punc- 129::UNC-116-tagRFP-TOMM-7].

KP8777 nuo-6(qm200) I; nuIs183 III; nuEx1863[punc- 129::NUO-6].

KP8874 sod-2(ok1030) I; nuIs183 III; nuEx1887[punc- 129::SOD-2].

KP8778 vhl-1(ok161) X; nuIs183 III; nuEx1864[punc- 129::VHL-1].

Constructs and transgenes

Transgenic strains were isolated by microinjection of various plasmids using either Pmyo-2::NLS-GFP or Pmyo-2::NLS-mCherry as co-injection markers. The kin-Tom7 construct was adapted from the original version (Rawson et al. 2014) to contain the following elements (listed 5′ to 3′): the snb-1 promoter (for locomotion and aldicarb assays) or the unc-129 promoter (for imaging), the complementary DNA (cDNA) for unc-116, linker sequence, GFP (for locomotion and aldicarb) or TagRFP (for imaging) with syntrons, attachment recombination site + second linker, the genomic sequence of tomm-7, and the let-858 3′-UTR.

The TOMM-20-mCherry construct contains the unc-129 promoter, the sequence encoding the first 53 amino acids of TOMM-20 carrying the mitochondrial localization signal, attachment recombination site, mCherry with syntrons, and the unc-54 3′-UTR. The Punc-129::SNB-1-GFP construct was previously described (Sieburth et al. 2005).

For the Punc-129::NLP-21-mNeonGreen construct, the unc-129 promoter, the nlp-21-minigene (coding region plus two syntrons), mNeonGreen with syntrons, and the let-858 3′-UTR were inserted into the miniMOS vector pCFJ910. Single copy insertion (nuSi187) of this transgene was obtained as described (Frokjaer-Jensen et al. 2014). The Punc-129::NLP-21-YFP (nuIs183) transgenic line was previously described (Sieburth et al. 2007).

The cell-specific rescue constructs contain the unc-129 promoter, the open reading frame including introns (nuo-6, vhl-1) or the cDNA (sod-2) of the rescuing gene, and the unc-54 3′-UTR.

Drug, hypoxia, and RNA-interference assays

Acute aldicarb assays were performed blind in five replicates on young adult worms as described (Nurrish et al. 1999). Locomotion was measured by transferring adults to unseeded plates and recording their movement at 2 Hz for 30 sec on a Zeiss Discovery Stereomicroscope using AxioVision software. The centroid velocity of each animal was analyzed at each frame using object-tracking software in AxioVision. The speed of each animal was calculated by averaging the velocity value at each frame.

For treatment of worms with varying oxygen levels, worms were picked onto a fresh plate at the L4 stage and the plate was put into a Hypoxia Incubator Chamber (STEMCELL Technologies). Using a MINIOS 1 Oxygen Analyzer (MEDIQUIP), the chamber was then filled with oxygen (for hyperoxia) or nitrogen until the oxygen test concentration was reached. Worms were left to grow at control and test oxygen levels for 24 hr and coelomocytes were imaged subsequently.

RNA interference (RNAi) was performed in the neuronal RNAi hypersensitive mutant background (nre-1lin-15b) (Schmitz et al. 2007). One-day-old hermaphrodites were dropped into bleach on RNAi plates. When the progeny reached L4 stage, worms were transferred onto a fresh RNAi plate and scored for coelomocyte fluorescence 24 hr later.

Fluorescence microscopy and quantitative analysis

Worms were immobilized on 10% agarose pads with 0.1-μm diameter polystyrene 501 microspheres (Polysciences 00876-15, 2.5% w/v suspension). For axonal fluorescence measurements, the dorsal nerve cord (midway between the vulva and the tail) was captured using a 60× objective (NA 1.45) on an Olympus FV-1000 confocal microscope at 5× digital zoom. Maximum intensity projections of z-series stacks were made using Metamorph 7.1 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Line scans of dorsal cord fluorescence were analyzed in Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) using custom-written software (Burbea et al. 2002; Dittman and Kaplan 2006). The intensity of NLP-21 axonal puncta was measured as peak punctal fluorescence normalized to the baseline of diffuse axonal fluorescence [ΔF/F = (Fpuncta − Faxon)/Faxon].

For coelomocyte fluorescence measurements, worms were imaged 24 hr after the L4 stage. Image stacks of the second-most-posterior coelomocyte were captured using a Zeiss Axioskop I, Olympus PlanAPO 100× 1.4 NA objective, and a CoolSnap HQ CCD camera (Roper Scientific, Tuscon, AZ). Maximum intensity projections were obtained using Metamorph 7.1 software (Molecular Devices). For quantification, the five brightest vesicles were analyzed for each coelomocyte and the mean fluorescence for each vesicle was logged. For each worm, coelomocyte fluorescence was calculated as the mean of the vesicle values in that animal subtracted by the background fluorescence (measured at an empty region on the slide). All fluorescence values are normalized to wild-type controls to facilitate comparison.

Data availability

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. Supplemental Material, Figure S1 and Figure S2 contain measurements of NLP-21 secretion in additional genotypes. Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.6849056.

Results

Axonal mitochondria promote neuropeptide secretion

In a prior study, we showed that mutations inactivating the C. elegans ric-7 gene significantly reduced neuropeptide secretion [which is mediated by exocytosis of dense core vesicles (DCVs)] but had little effect on acetylcholine release [which is mediated by exocytosis of synaptic vesicles (SVs)] (Hao et al. 2012). These results imply that RIC-7 plays a specific role in promoting exocytosis of DCVs but not SVs. Decreased neuropeptide secretion in ric-7 mutants was accompanied by decreased locomotion rate and increased resistance to the paralytic effects of aldicarb (an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor) (Hao et al. 2012). Homologs of ric-7 are found in other nematodes but not in other metazoans. The ric-7 gene encodes an unfamiliar protein that lacks any previously described structural domain. Thus, the sequence of the RIC-7 protein failed to provide any clues as to the cell biological mechanism underlying RIC-7’s function in neuropeptide secretion.

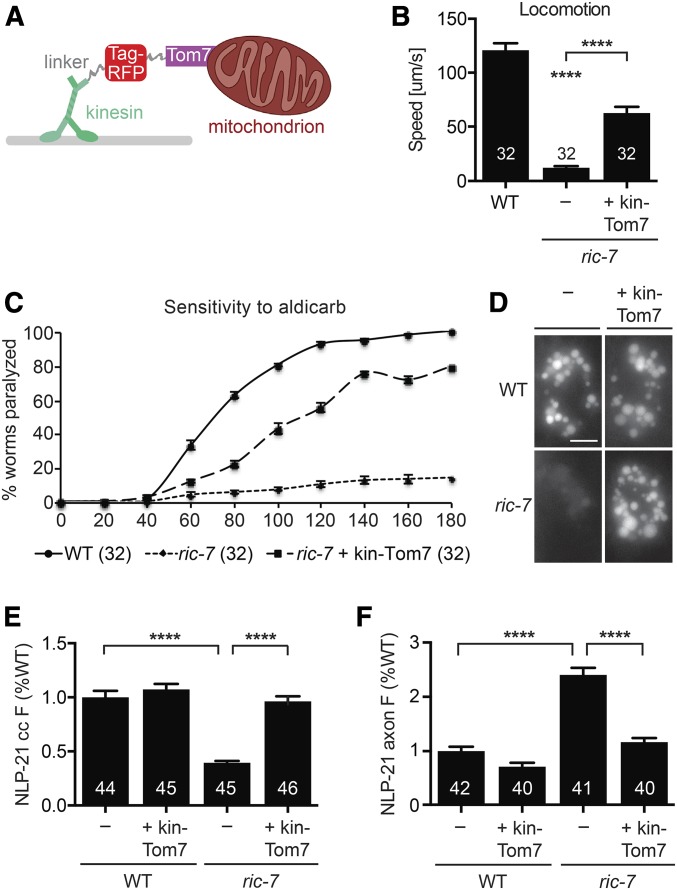

A subsequent study showed that RIC-7 is required for kinesin-1-mediated transport of mitochondria into axons (Rawson et al. 2014). These results suggest that the behavioral and neuropeptide secretion defects observed in ric-7 mutants could be caused by the absence of axonal mitochondria. To test this idea, we expressed a chimeric kinesin construct (kin-Tom7) in which UNC-116/KIF5 is fused to the outer mitochondrial membrane protein TOMM-7 (Figure 1A, Rawson et al. 2014). Expression of this construct restores the mitochondrial distribution in ric-7 mutant axons (Rawson et al. 2014). Neuronal expression of kin-Tom7 significantly improved locomotion and decreased the aldicarb resistance of ric-7 mutants (Figure 1, B and C), suggesting that ric-7 behavioral defects are caused by the lack of axonal mitochondria.

Figure 1.

Axonal mitochondria are required for locomotion and neuropeptide release. (A) Schematic of the kin-Tom7 construct in which UNC-116/KIF5 was fused to TagRFP and the outer mitochondrial protein TOMM-7. This illustration was modified from that shown in the original article describing kin-Tom7 (Rawson et al. 2014). (B and C) Locomotion rate (B) and aldicarb-induced paralysis (C) of wild-type, ric-7 mutant, and ric-7 mutant worms that express kin-Tom7 in neurons. (D and E) Representative images (D) and quantification (E) of NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence in wild-type and ric-7 mutant worms with and without the DA/DB-specific expression of kin-Tom7. (F) Dorsal cord axonal NLP-21 fluorescence in cholinergic motor neurons of wild-type and ric-7 mutant worms with and without the DA/DB-specific expression of kin-Tom7. Number of animals analyzed is indicated for each genotype. Error bars indicate SEM. Values that differ significantly are indicated. **** P < 0.0001, ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Scale bar, 5 μm. WT, wild type.

To assay neuropeptide secretion, we expressed the proneuropeptide NLP-21 tagged with YFP in the cholinergic DA/DB motor neurons (using the unc-129 promoter). We quantified NLP-21::YFP secretion by analyzing YFP fluorescence in the endolysosomal compartment of coelomocytes, which are scavenger cells that endocytose proteins secreted into the body cavity (Fares and Greenwald 2001). In parallel, we assayed the abundance of NLP-21-containing vesicles in DA/DB axons by quantifying the fluorescence intensity of YFP puncta in dorsal cord axons (Sieburth et al. 2007). As previously reported, NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence was significantly decreased in ric-7 mutants while axonal puncta fluorescence was significantly increased (Figure 1, D–F; Hao et al. 2012), both indicating decreased NLP-21 secretion in ric-7 mutants. Both the coelomocyte and axonal NLP-21 fluorescence defects exhibited by ric-7 mutants were rescued by expressing kin-Tom7 in the DA/DB neurons (Figure 1, D–F). Thus, the ric-7 behavioral and neuropeptide secretion defects are both caused by the absence of axonal mitochondria.

Neuropeptide secretion requires oxidative phosphorylation but not mitochondrial calcium uptake

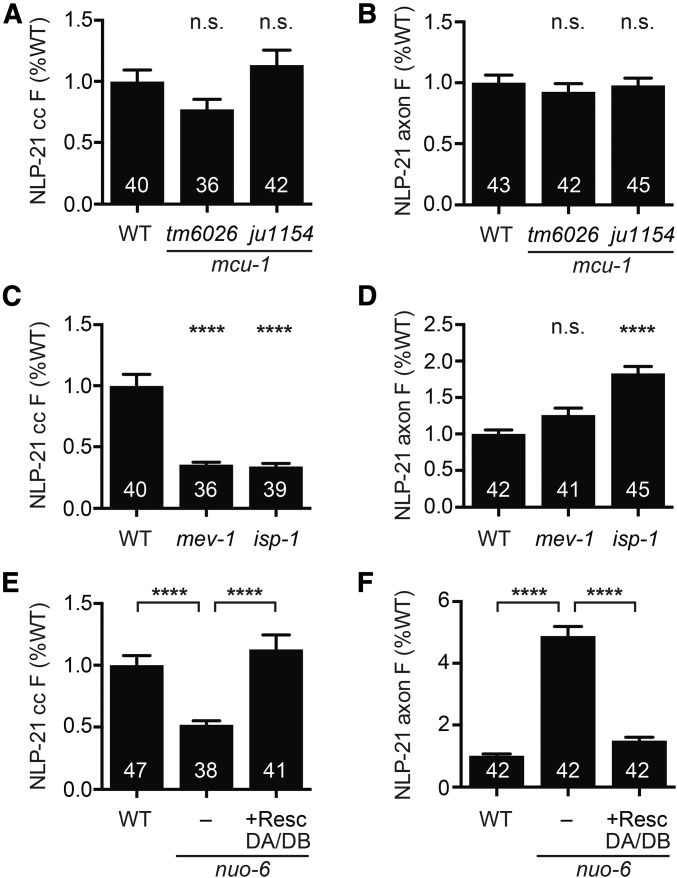

Loss of axonal mitochondria is predicted to result in multiple defects. For example, mitochondria regulate cytoplasmic calcium levels by taking up calcium through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) (Kirichok et al. 2004; Baughman et al. 2011; De Stefani et al. 2011), which could contribute to the ric-7 neuropeptide secretion defect. To test this idea, we analyzed two independent mcu-1 null mutants, finding no significant changes in NLP-21 coelomocyte and axonal puncta fluorescence (Figure 2, A and B). These results suggest that changes in mitochondrial calcium uptake are unlikely to account for the ric-7 mutant neuropeptide secretion defects.

Figure 2.

Neuropeptide release requires oxidative phosphorylation but not mitochondrial calcium uptake. (A and B) Mutation of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter mcu-1 did not alter NLP-21 (A) coelomocyte or (B) axonal fluorescence. (C–F) Oxidative phosphorylation is required for neuropeptide secretion cell autonomously. (C) Mutation of the complex-II component mev-1 or the complex-III component isp-1 reduced NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence. (D) Mutation of isp-1 increased NLP-21 axonal fluorescence. Mutation of the complex-I component nuo-6 (E) decreased NLP-21 coelomocyte and (F) increased NLP-21 axonal fluorescence, both of which were rescued by expression of a wild-type nuo-6 transgene in cholinergic DA/DB motor neurons only. Number of animals analyzed is indicated for each genotype. Error bars indicate SEM. Values that differ significantly are indicated. **** P < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn test for multiple comparisons. n.s., not significant; resc, rescue; WT, wild type.

Next, we asked if neuropeptide secretion requires mitochondrial respiration. Mutations in the nuo-6, mev-1, and isp-1 genes (which encode components of complex I, II, and III, respectively) reduce respiration rate (Ishii et al. 1998; Yang and Hekimi 2010b; Pfeiffer et al. 2011; Yee et al. 2014). These oxidative phosphorylation mutants also had decreased NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence and increased axonal fluorescence, indicating decreased neuropeptide secretion (Figure 2, C–F). The nuo-6 NLP-21 secretion defect was rescued by a transgene restoring NUO-6 expression specifically in the DA/DB neurons (Figure 2, E and F). These results support the idea that mitochondrial respiration acts in a cell-autonomous manner to promote neuropeptide secretion from DA/DB neurons.

Increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species inhibits neuropeptide secretion

Disrupting oxidative phosphorylation can lead to reduced ATP levels and altered production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Senoo-Matsuda et al. 2001; Yang and Hekimi 2010a; Yee et al. 2014), both of which could affect neuropeptide secretion. Several steps in neurotransmission, such as establishment and maintenance of membrane potential and membrane fusion, are known to require ATP. Accordingly, we found that mutants of glycolytic enzymes also had decreased neuropeptide secretion (Figure S1A).

Conflicting results have been reported for the effects of mev-1, isp-1, and nuo-6 mutations on ATP levels (Senoo-Matsuda et al. 2001; Yang and Hekimi 2010a,b; Yee et al. 2014). In addition, several findings suggest that glycolysis plays a more important role than oxidative phosphorylation in supplying the metabolic requirements for neurotransmission (Rangaraju et al. 2014; Jang et al. 2016; Ashrafi and Ryan 2017; Ashrafi et al. 2017). Prompted by these results, we investigated other potential mechanisms for neuropeptide secretion defects in the oxidative phosphorylation deficient mutants. Since mev-1, isp-1, and nuo-6 mutants have all been shown to increase ROS levels (Ishii et al. 1998; Senoo-Matsuda et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2010; Yang and Hekimi 2010a,b; Yee et al. 2014), we hypothesized that altered ROS production might contribute to decreased secretion in these mutants.

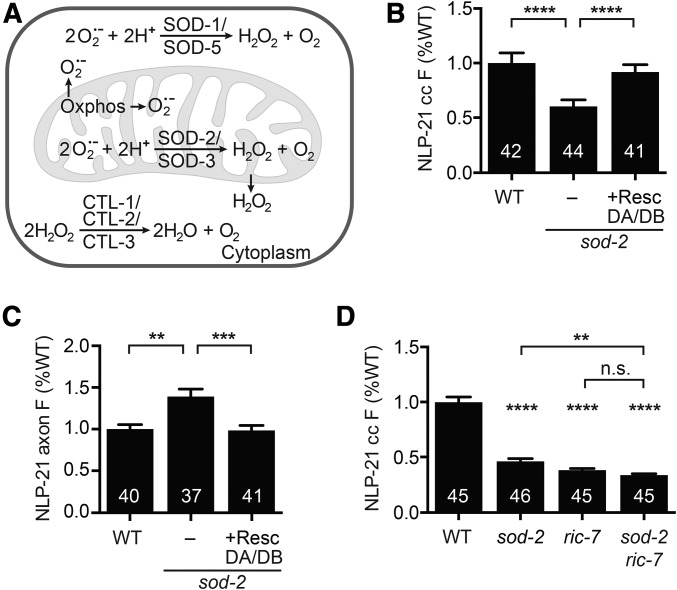

To test this idea, we measured NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence in mutants lacking ROS detoxification enzymes. Superoxide dismutases (SODs) convert superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which can then be broken down to water by catalase (Figure 3A). In C. elegans, the genes sod-1 and sod-5 encode cytoplasmic Cu/ZnSODs (Larsen 1993; Jensen and Culotta 2005), sod-2 and sod-3 encode mitochondrial MnSODs (Giglio et al. 1994; Suzuki et al. 1996; Hunter et al. 1997), and sod-4 encodes an extracellular Cu/ZnSOD (Fujii et al. 1998). We analyzed NLP-21 secretion in all five SOD mutants (Figure S1, B and C). NLP-21 secretion was significantly reduced in sod-2 mutants (which lack a mitochondrial MnSOD), as indicated by decreased NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence and increased NLP-21 axonal puncta fluorescence, both of which were rescued by a transgene restoring sod-2 expression in DA/DB neurons (Figure 3, B and C). Thus, ric-7 and sod-2 mutants exhibited very similar defects in NLP-21 secretion, suggesting that SOD-2 and RIC-7 may function together to promote NLP-21 secretion. Consistent with this idea, we found that the NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence defect observed in sod-2; ric-7 double mutants was not significantly different from that observed in ric-7 single mutants (Figure 3D). Unlike sod-2 mutants, NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence was not significantly reduced in sod-3 mutants, which lack a second mitochondrial MnSOD (Figure S1B), perhaps because sod-3 is primarily expressed in dauer larvae (Doonan et al. 2008; Van Raamsdonk and Hekimi 2012). Collectively, these results suggest that perturbing mitochondrial ROS detoxification in axons inhibits NLP-21 secretion.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial superoxide detoxification is required for neuropeptide secretion. (A) Oxidative phosphorylation generates superoxide as by-products, which is converted to H2O2 by superoxide dismutases SOD-1 and SOD-5 in the cytoplasm and SOD-2 and SOD-3 in mitochondria. H2O2 is membrane diffusible and is subsequently detoxified by catalases. (B and C) Mutation of sod-2 decreased NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence (B) and increased NLP-21 axonal fluorescence (C), both of which were rescued by expressing a wild-type sod-2 construct in cholinergic DA/DB motor neurons only. (D) The sod-2 and ric-7 mutations did not have additive effects on NLP-21 secretion. NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence was compared in wild type, sod-2 and ric-7 single mutants, and sod-2; ric-7 double mutants. Number of animals analyzed is indicated for each genotype. Error bars indicate SEM. Values that differ significantly are indicated. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn test for multiple comparisons. n.s., not significant; oxphos, oxidative phosphorylation; resc, rescue; WT, wild type.

To determine if increased cytoplasmic ROS levels regulate NLP-21 secretion, we analyzed sod-1 and sod-5 mutants, which lack the cytoplasmic SODs. NLP-21 secretion was significantly increased in sod-1 mutants whereas decreased secretion was observed in sod-5 mutants (Figure S1, B and C). These results suggest that increased cytoplasmic ROS does indeed regulate NLP-21 secretion but opposite effects are observed depending on which cytoplasmic SOD is impaired. Taken together, these results support the idea that neuropeptide secretion is strongly inhibited by a variety of mitochondrial defects, including mutations disrupting axonal transport of mitochondria, mutations disrupting mitochondrial respiration, and mutations increasing mitochondrial ROS levels. Furthermore, in each case, mitochondria act cell autonomously to promote neuropeptide secretion.

Hypoxia inhibits neuropeptide secretion

The neuropeptide secretion defects observed in mitochondrial mutants could result from decreased levels of ATP or other metabolites. Alternatively, decreased neuropeptide secretion could result from activation of stress response pathways. Several stress response pathways are induced in mitochondrial mutants, including those mediated by the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF-1), SKN-1/Nrf2, the mitochondrial unfolded protein response, and the AMP-activated protein kinase (Sena and Chandel 2012; Hwang et al. 2014; Blackwell et al. 2015; Chang et al. 2017; Dues et al. 2017; Shpilka and Haynes 2018).

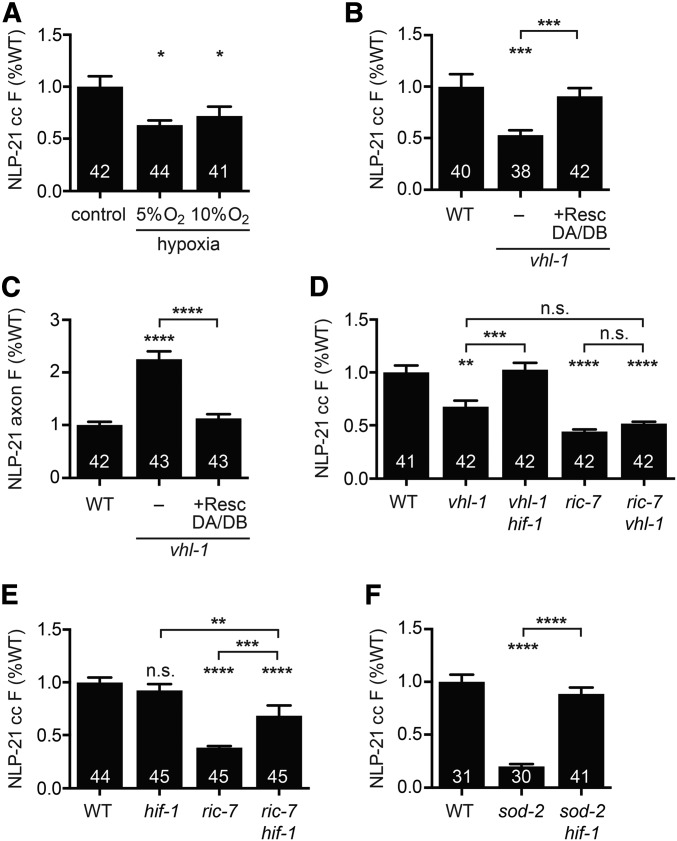

We focused on HIF-1 because ric-7 mutants display hypoxic phenotypes (Jang et al. 2016) and mutations decreasing mitochondrial respiration stabilize HIF-1 (Lee et al. 2010; Hwang et al. 2014). Prompted by these results, we hypothesized that ric-7 mutants might undergo a hypoxic response that inhibits neuropeptide release. We did several experiments to test this idea. First, we asked if growth in reduced oxygen tension inhibits neuropeptide secretion. Consistent with this idea, growing wild-type animals in a hypoxic chamber (5 or 10% oxygen) for 24 hr significantly reduced NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence (Figure 4A). By contrast, growth in hyperoxic conditions (100% oxygen) for the same duration had no effect (Figure S2A). Thus, hypoxia was sufficient to inhibit NLP-21 secretion.

Figure 4.

ric-7 and sod-2 mutations inhibit neuropeptide secretion through activation of the hypoxic response. (A) NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence in worms that were either grown at atmospheric oxygen levels, at 5% oxygen, or at 10% oxygen for 24 hr. Worms grown under hypoxic conditions exhibited reduced NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence. (B and C) Mutation of vhl-1 decreased NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence (B) and increased NLP-21 axonal fluorescence (C), both of which were rescued by expressing wild-type vhl-1 in cholinergic DA/DB motor neurons. (D–F) Comparison of NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence for the indicated genotypes. (D) Mutation of hif-1 suppressed the decreased NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence exhibited by vhl-1 mutants. vhl-1 and ric-7 mutations did not have additive effects on NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence. (E) Mutation of hif-1 partially restored NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence in ric-7 mutants. (F) Mutation of hif-1 fully restored NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence in sod-2 mutants. Number of animals analyzed is indicated for each genotype. Error bars indicate SEM. Values that differ significantly are indicated. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn test for multiple comparisons. n.s., not significant; resc, rescue; WT, wild type.

Next, we asked if activation of HIF-1 was sufficient to inhibit NLP-21 secretion. To test this idea, we analyzed vhl-1 mutants. VHL-1 is the C. elegans ortholog of the von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor protein, which promotes HIF-1 ubiquitination under normoxic conditions. In vhl-1 mutants, HIF-1 is stabilized and constitutively activates the hypoxic transcriptional response (Kaelin 2007). As expected, NLP-21 secretion was significantly decreased in vhl-1 mutants and this defect was rescued by a transgene that restores VHL-1 expression specifically in the DA/DB neurons (Figure 4, B and C). The NLP-21 secretion defect in vhl-1 mutants was abolished in hif-1; vhl-1 double mutants, confirming that the vhl-1 secretion defect was a consequence of stabilized HIF-1 (Figure 4D). Taken together, these results suggest that activation of the HIF-1 hypoxia response in DA/DB neurons is sufficient to inhibit NLP-21 secretion.

Does activation of HIF-1 account for the ric-7 neuropeptide secretion defect? We did two experiments to test this idea. First, if ric-7 mutations inhibit neuropeptide secretion by stabilizing HIF-1, then ric-7 and vhl-1 mutations should not have additive effects on NLP-21 secretion in double mutants. Consistent with this idea, NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence in vhl-1; ric-7 double mutants was not significantly different from that in either single mutant (Figure 4D). By contrast, vhl-1 and unc-31/CAPS mutations did have additive effects on NLP-21 secretion in double mutants (Figure S2B). Second, if ric-7 mutations inhibit neuropeptide secretion by activating the hypoxic response, then hif-1 mutations should restore secretion in these mutants. As predicted, ric-7hif-1 double mutants had significantly higher NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence than ric-7 single mutants (Figure 4E). Similarly, the NLP-21 secretion defect of sod-2 mutants was fully suppressed in sod-2; hif-1 double mutants (Figure 4F). HIF-1’s effect was specific because inactivating two other stress-activated transcription factors (DAF-16/FOXO and SKN-1/Nrf) did not increase NLP-21 coelomocyte fluorescence in ric-7 mutants (Figure S2, C and D). Collectively, these results support the idea that disrupting mitochondrial transport into axons (in ric-7 mutants) or disrupting mitochondrial function (in sod-2 mutants) elicits a cell-autonomous hypoxic response that stabilizes HIF-1 and inhibits neuropeptide secretion.

Discussion

Here we show that axonal transport of mitochondria is critical for neuropeptide release and locomotion in C. elegans. Impaired mitochondrial transport, reduced oxidative phosphorylation rates, and increased mitochondrial ROS levels all inhibited neuropeptide secretion cell autonomously; whereas interfering with mitochondrial calcium uptake had no effect. The effects of axonal mitochondria on neuropeptide release are mediated (at least in part) by changes in HIF-1 activity. Activating HIF-1 inhibited neuropeptide secretion while hif-1 null mutations restored secretion in mutants with impaired mitochondrial transport or function. These results demonstrate that modifications of mitochondrial transport or function lead to cell-autonomous changes in neuropeptide secretion, thus providing a mechanism whereby the metabolic or redox state of a neuron could alter the global behavioral state of the animal.

Mitochondrial transport mutants as a model to identify mitochondrial function in neurotransmission

Blocking mitochondrial transport into axons can result in a variety of synaptic defects by a number of different mechanisms. For example, mouse syntabulin knockouts are defective for mitochondrial transport in cultured superior cervical ganglion neurons, which is accompanied by accelerated synaptic depression, slowed recovery after SV depletion, and impaired short-term plasticity (Ma et al. 2009). In contrast, decreased axonal mitochondria in rat syntaphilin mutant hippocampal neurons slow presynaptic calcium clearance and enhance short-term facilitation (Kang et al. 2008). Here we find that the absence of axonal mitochondria induces a hypoxic response that inhibits neuropeptide secretion, thus identifying a new mechanism by which mitochondrial transport defects alter neurotransmission. Although ric-7 is not conserved beyond nematodes and has no recognizable structural domains, it is conceivable that RIC-7 functions analogously to syntabulin (which is a KIF5B cargo adaptor for mitochondrial transport) (Ma et al. 2009). While it is likely that RIC-7 promotes transport of other unidentified cargoes, restoring axonal mitochondria in ric-7 mutants (by expressing kin-Tom7) rescued the NLP-21 secretion defects. Thus, mitochondrial transport defects alone account for the impaired neuropeptide secretion of ric-7 mutants.

Neuropeptide secretion does not require the mitochondrial calcium uniporter MCU-1

Mitochondrial calcium uptake regulates synaptic strength in a variety of systems (Werth and Thayer 1994; Tang and Zucker 1997; Billups and Forsythe 2002; Medler and Gleason 2002; David and Barrett 2003; Talbot et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2005; Chouhan et al. 2010; Shutov et al. 2013; Kwon et al. 2016). However, other studies reported limited or undetectable effects of mitochondrial calcium uptake on neurotransmitter release (Guo et al. 2005; Verstreken et al. 2005; Ma et al. 2009), indicating that mitochondrial effects on local calcium may vary between cell types and systems. Using two independent mcu-1 null alleles, we show that neuropeptide secretion from C. elegans motor neurons is independent of the mitochondrial uniporter. This suggests that other calcium clearance mechanisms (such as the endoplasmic reticulum, Na+/Ca2+ pumps, or membrane Ca2+ ATPases) may have the dominating effect in DA/DB neurons (Rizzuto et al. 1998; Emptage et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2002; Bouchard et al. 2003; de Juan-Sanz et al. 2017).

Three matrix dehydrogenases are activated by calcium ions, thus coupling mitochondrial calcium levels to bioenergetics and metabolic flux (Denton and McCormack 1980). Accordingly, knockout of MCU attenuates metabolic rate in a variety of cell types (Kamer and Mootha 2015). One might therefore expect that mcu-1 mutant animals should inhibit neuropeptide secretion indirectly due to changes in mitochondrial metabolism. However, previous studies reported that mcu knockouts in C. elegans are viable and fertile, while mcu knockout mice have reduced exercise capacity but have unaltered basal metabolic rates (Pan et al. 2013; Xu and Chisholm 2014). Mitochondrial calcium levels are strongly reduced (25% of wild-type levels) but not eliminated in mcu knockouts, implying that alternate mechanisms for calcium entry into mitochondria must exist (Feng et al. 2013; Murphy et al. 2014). The residual mitochondrial calcium levels may be sufficient to allow mcu-1 mutant worms to sustain normal levels of neuropeptide secretion.

Increased mitochondrial ROS inhibits neuropeptide secretion

Two findings in this study suggest that increased mitochondrial ROS inhibits neuropeptide secretion cell autonomously. First, neuropeptide secretion is reduced in mutants lacking the major mitochondrial superoxide dismutase, sod-2. Inactivating the second mitochondrial SOD (SOD-3) had no effect on secretion, most likely because sod-3 is predominantly expressed in dauer larvae and not in adult worms (Doonan et al. 2008; Van Raamsdonk and Hekimi 2012; Suthammarak et al. 2013). Second, mutations in the genes nuo-6, mev-1, and isp-1 all lead to elevated mitochondrial ROS levels (Senoo-Matsuda et al. 2001; Yang and Hekimi 2010a,b; Yee et al. 2014) and decreased neuropeptide secretion. Because of their chemical reactivity, ROS can damage lipids, proteins, and DNA (Cross et al. 1987), and oxidative stress has been associated with many neurodegenerative diseases. ROS can also function as a second messenger in signal transduction pathways by oxidizing critical thiols within proteins, thereby regulating numerous biological processes, including metabolic adaptation, differentiation, and proliferation (Schieber and Chandel 2014; Reczek and Chandel 2015).

Intracellular ROS can activate stress response pathways in distant tissues. For example, ROS-induced activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response in multiple classes of C. elegans neurons elicits a stress response in the intestine (Berendzen et al. 2016; Shao et al. 2016). In this case, the nonautonomous effect of ROS is mediated by increased neuronal secretion of serotonin and FLP-2. By contrast, we observed decreased NLP-21 secretion in motor neurons when mitochondrial function was impaired. Taken together, these results suggest that mitochondrial stress can either promote (FLP-2) or inhibit (NLP-21) neuropeptide secretion, depending on the activating stimulus and cell type.

One surprising observation was that mutations in sod-1 and sod-5 (the two cytoplasmic SODs) had opposite effects on neuropeptide secretion. Different phenotypes have previously been reported for these mutations: while sod-1 mutant worms are hypersensitive to drug-induced oxidative stress, sod-5 mutant worms are unaffected, presumably because sod-5 is predominantly expressed in the dauer larva (Doonan et al. 2008; Van Raamsdonk and Hekimi 2009, 2012). Notably, sod-1 mutants have increased ROS in both cytoplasm and mitochondria (Yanase et al. 2009). Recent findings suggest that the location of ROS production can influence downstream events (Van Raamsdonk 2015). For example, in a ROS-sensitized clk-1 mutant background of C. elegans, further increase of cytoplasmic ROS by mutation of sod-1 shortens life span, whereas increase of mitochondrial ROS by sod-2 mutation increases life span (Schaar et al. 2015). How different subcellular localizations of ROS produce distinct phenotypes is poorly understood. The opposite effects of sod-1 and sod-5 mutations could indicate that accumulation of cytoplasmic ROS in different tissues or at different times during development can either promote or inhibit NLP-21 secretion. Further experiments will be required to determine how SOD-1 and SOD-5 regulate neuropeptide secretion.

Activation of the hypoxic response

Acute neural activity relies on an increase in oxidative phosphorylation for ATP supply, which results in decreased oxygen levels (Hall et al. 2012; Rangaraju et al. 2014). Therefore, oxygen depletion and HIF-1 activation provide a way to sense and adapt to metabolic stress. At normal oxygen levels, HIF-1 is continually hydroxylated by oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylases. Hydroxylated HIF-1 is ubiquitinated by an E3 ligase containing VHL-1, which results in HIF-1 degradation. During hypoxia, the prolyl hydroxylases are inactive and HIF-1 becomes stabilized, initiating transcription of a variety of genes to adapt to the hypoxic condition. Prior studies suggest that mutations altering mitochondrial respiration can also stabilize HIF-1 (Lee et al. 2010; Hwang et al. 2014). Mitochondria have been proposed to regulate HIF-1 stability through a variety of mechanisms. Mitochondrially produced ROS are proposed to directly activate HIF-1 (Chandel et al. 2000; Brunelle et al. 2005; Guzy et al. 2005; Mansfield et al. 2005). Other studies suggest that altered abundance of mitochondrial metabolites stabilize HIF-1 (Lu et al. 2005; Hewitson et al. 2007; Koivunen et al. 2007; Mishur et al. 2016). Therefore, HIF-1 could become activated in ric-7 and sod-2 mutants due to elevated ROS production or altered abundance of mitochondrial metabolites. NLP-21 secretion was inhibited when HIF-1 was activated by vhl-1 mutations, by hypoxic growth conditions, or by mutations altering mitochondrial respiration and ROS levels. Thus, our results are compatible with either mechanism.

Activating HIF-1 initiates a comprehensive transcriptional program that, among others, reduces oxidative phosphorylation and promotes glycolysis (Wang et al. 1995; Rankin and Giaccia 2016). Activated HIF-1 also promotes axon regeneration following injury (Nix et al. 2014; Cho et al. 2015; Alam et al. 2016), suggesting a neuroprotective role in certain conditions. This study identifies a new role for HIF-1 in inhibiting neuropeptide secretion, indicating that in addition to cell-autonomous metabolic rewiring, activation of HIF-1 might (directly or indirectly) alter intercellular signaling, thus facilitating the communication of cell-specific stresses to different cells and tissues to induce broad physiological changes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for strains, advice, reagents, and comments on the manuscript: the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, S. Mitani, A. Chisholm, and Y. Jin for strains; E. Jorgensen for the kin-Tom7 and tomm-20 constructs; J. Meisel for assistance with hypoxia assays; and members of the Kaplan laboratory for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a Human Frontiers postdoctoral fellowship to T.Z. (LT000234/2013) and by a National Institutes of Health research grant to J.M.K. (DK80215).

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.6849056.

Communicating editor: D. Greenstein

Literature Cited

- Alam T., Maruyama H., Li C., Pastuhov S. I., Nix P., et al. , 2016. Axotomy-induced HIF-serotonin signalling axis promotes axon regeneration in C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 7: 10388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi G., Ryan T. A., 2017. Glucose metabolism in nerve terminals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 45: 156–161. 10.1016/j.conb.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi G., Wu Z., Farrell R. J., Ryan T. A., 2017. GLUT4 mobilization supports energetic demands of active synapses. Neuron 93: 606–615.e3. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman J. M., Perocchi F., Girgis H. S., Plovanich M., Belcher-Timme C. A., et al. , 2011. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476: 341–345. 10.1038/nature10234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendzen K. M., Durieux J., Shao L. W., Tian Y., Kim H. E., et al. , 2016. Neuroendocrine coordination of mitochondrial stress signaling and proteostasis. Cell 166: 1553–1563.e10. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billups B., Forsythe I. D., 2002. Presynaptic mitochondrial calcium sequestration influences transmission at mammalian central synapses. J. Neurosci. 22: 5840–5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell T. K., Steinbaugh M. J., Hourihan J. M., Ewald C. Y., Isik M., 2015. SKN-1/Nrf, stress responses, and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88: 290–301. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard R., Pattarini R., Geiger J. D., 2003. Presence and functional significance of presynaptic ryanodine receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 69: 391–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle J. K., Bell E. L., Quesada N. M., Vercauteren K., Tiranti V., et al. , 2005. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 1: 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbea M., Dreier L., Dittman J. S., Grunwald M. E., Kaplan J. M., 2002. Ubiquitin and AP180 regulate the abundance of GLR-1 glutamate receptors at postsynaptic elements in C. elegans. Neuron 35: 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel N. S., McClintock D. S., Feliciano C. E., Wood T. M., Melendez J. A., et al. , 2000. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 25130–25138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. W., Pisano S., Chaturbedi A., Chen J., Gordon S., et al. , 2017. Transcription factors CEP-1/p53 and CEH-23 collaborate with AAK-2/AMPK to modulate longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 16: 814–824. 10.1111/acel.12619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y., Shin J. E., Ewan E. E., Oh Y. M., Pita-Thomas W., et al. , 2015. Activating injury-responsive genes with hypoxia enhances axon regeneration through neuronal HIF-1alpha. Neuron 88: 720–734. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouhan A. K., Zhang J., Zinsmaier K. E., Macleod G. T., 2010. Presynaptic mitochondria in functionally different motor neurons exhibit similar affinities for Ca2+ but exert little influence as Ca2+ buffers at nerve firing rates in situ. J. Neurosci. 30: 1869–1881. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4701-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross C. E., Halliwell B., Borish E. T., Pryor W. A., Ames B. N., et al. , 1987. Oxygen radicals and human disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 107: 526–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David G., Barrett E. F., 2003. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake prevents desynchronization of quantal release and minimizes depletion during repetitive stimulation of mouse motor nerve terminals. J. Physiol. 548: 425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Juan-Sanz J., Holt G. T., Schreiter E. R., de Juan F., Kim D. S., et al. , 2017. Axonal endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content controls release probability in CNS nerve terminals. Neuron 93: 867–881.e6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton R. M., McCormack J. G., 1980. The role of calcium in the regulation of mitochondrial metabolism. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 8: 266–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefani D., Raffaello A., Teardo E., Szabo I., Rizzuto R., 2011. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476: 336–340. 10.1038/nature10230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman J. S., Kaplan J. M., 2006. Factors regulating the abundance and localization of synaptobrevin in the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 11399–11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan R., McElwee J. J., Matthijssens F., Walker G. A., Houthoofd K., et al. , 2008. Against the oxidative damage theory of aging: superoxide dismutases protect against oxidative stress but have little or no effect on life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 22: 3236–3241. 10.1101/gad.504808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dues D. J., Schaar C. E., Johnson B. K., Bowman M. J., Winn M. E., et al. , 2017. Uncoupling of oxidative stress resistance and lifespan in long-lived isp-1 mitochondrial mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 108: 362–373. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emptage N. J., Reid C. A., Fine A., 2001. Calcium stores in hippocampal synaptic boutons mediate short-term plasticity, store-operated Ca2+ entry, and spontaneous transmitter release. Neuron 29: 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares H., Greenwald I., 2001. Genetic analysis of endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans: coelomocyte uptake defective mutants. Genetics 159: 133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Li H., Tai Y., Huang J., Su Y., et al. , 2013. Canonical transient receptor potential 3 channels regulate mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 11011–11016. 10.1073/pnas.1309531110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer-Jensen C., Davis M. W., Sarov M., Taylor J., Flibotte S., et al. , 2014. Random and targeted transgene insertion in Caenorhabditis elegans using a modified Mos1 transposon. Nat. Methods 11: 529–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M., Ishii N., Joguchi A., Yasuda K., Ayusawa D., 1998. A novel superoxide dismutase gene encoding membrane-bound and extracellular isoforms by alternative splicing in Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA Res. 5: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglio M. P., Hunter T., Bannister J. V., Bannister W. H., Hunter G. J., 1994. The manganese superoxide dismutase gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 33: 37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Macleod G. T., Wellington A., Hu F., Panchumarthi S., et al. , 2005. The GTPase dMiro is required for axonal transport of mitochondria to Drosophila synapses. Neuron 47: 379–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy R. D., Hoyos B., Robin E., Chen H., Liu L., et al. , 2005. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 1: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C. N., Klein-Flugge M. C., Howarth C., Attwell D., 2012. Oxidative phosphorylation, not glycolysis, powers presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms underlying brain information processing. J. Neurosci. 32: 8940–8951. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0026-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S. M., Baig H. S., Hammarlund M., 2016. Mitochondria localize to injured axons to support regeneration. Neuron 92: 1308–1323. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Hu Z., Sieburth D., Kaplan J. M., 2012. RIC-7 promotes neuropeptide secretion. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002464 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson K. S., Lienard B. M., McDonough M. A., Clifton I. J., Butler D., et al. , 2007. Structural and mechanistic studies on the inhibition of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor hydroxylases by tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 3293–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T., Bannister W. H., Hunter G. J., 1997. Cloning, expression, and characterization of two manganese superoxide dismutases from Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 28652–28659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang A. B., Ryu E. A., Artan M., Chang H. W., Kabir M. H., et al. , 2014. Feedback regulation via AMPK and HIF-1 mediates ROS-dependent longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: E4458–E4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N., Fujii M., Hartman P. S., Tsuda M., Yasuda K., et al. , 1998. A mutation in succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b causes oxidative stress and ageing in nematodes. Nature 394: 694–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S., Nelson J. C., Bend E. G., Rodriguez-Laureano L., Tueros F. G., et al. , 2016. Glycolytic enzymes localize to synapses under energy stress to support synaptic function. Neuron 90: 278–291. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. T., Culotta V. C., 2005. Activation of CuZn superoxide dismutases from Caenorhabditis elegans does not require the copper chaperone CCS. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 41373–41379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johri A., Beal M. F., 2012. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 342: 619–630. 10.1124/jpet.112.192138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W. G., 2007. Von hippel-lindau disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2: 145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamer K. J., Mootha V. K., 2015. The molecular era of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16: 545–553. 10.1038/nrm4039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. S., Tian J. H., Pan P. Y., Zald P., Li C., et al. , 2008. Docking of axonal mitochondria by syntaphilin controls their mobility and affects short-term facilitation. Cell 132: 137–148. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. S., Adriaanse B. A., Greig N. H., Mattson M. P., Cader M. Z., et al. , 2017. Mitophagy and Alzheimer’s disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 40: 151–166. 10.1016/j.tins.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. H., Korogod N., Schneggenburger R., Ho W. K., Lee S. H., 2005. Interplay between Na+/Ca2+ exchangers and mitochondria in Ca2+ clearance at the calyx of Held. J. Neurosci. 25: 6057–6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirichok Y., Krapivinsky G., Clapham D. E., 2004. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427: 360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivunen P., Hirsila M., Remes A. M., Hassinen I. E., Kivirikko K. I., et al. , 2007. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) hydroxylases by citric acid cycle intermediates: possible links between cell metabolism and stabilization of HIF. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 4524–4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krench M., Littleton J. T., 2017. Neurotoxicity pathways in Drosophila models of the polyglutamine disorders. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 121: 201–223. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S. K., Sando R., III, Lewis T. L., Hirabayashi Y., Maximov A., et al. , 2016. LKB1 regulates mitochondria-dependent presynaptic calcium clearance and neurotransmitter release properties at excitatory synapses along cortical axons. PLoS Biol. 14: e1002516 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen P. L., 1993. Aging and resistance to oxidative damage in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90: 8905–8909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Hwang A. B., Kenyon C., 2010. Inhibition of respiration extends C. elegans life span via reactive oxygen species that increase HIF-1 activity. Curr. Biol. 20: 2131–2136. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Yuan L. L., Johnston D., Gray R., 2002. Calcium signaling at single mossy fiber presynaptic terminals in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 87: 1132–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Dalgard C. L., Mohyeldin A., McFate T., Tait A. S., et al. , 2005. Reversible inactivation of HIF-1 prolyl hydroxylases allows cell metabolism to control basal HIF-1. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 41928–41939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Cai Q., Lu W., Sheng Z. H., Mochida S., 2009. KIF5B motor adaptor syntabulin maintains synaptic transmission in sympathetic neurons. J. Neurosci. 29: 13019–13029. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2517-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield K. D., Guzy R. D., Pan Y., Young R. M., Cash T. P., et al. , 2005. Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from loss of cytochrome c impairs cellular oxygen sensing and hypoxic HIF-alpha activation. Cell Metab. 1: 393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medler K., Gleason E. L., 2002. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) buffering regulates synaptic transmission between retinal amacrine cells. J. Neurophysiol. 87: 1426–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishur R. J., Khan M., Munkacsy E., Sharma L., Bokov A., et al. , 2016. Mitochondrial metabolites extend lifespan. Aging Cell 15: 336–348. 10.1111/acel.12439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Pan X., Nguyen T., Liu J., Holmstrom K. M., et al. , 2014. Unresolved questions from the analysis of mice lacking MCU expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 449: 384–385. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nix P., Hammarlund M., Hauth L., Lachnit M., Jorgensen E. M., et al. , 2014. Axon regeneration genes identified by RNAi screening in C. elegans. J. Neurosci. 34: 629–645. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3859-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurrish S., Segalat L., Kaplan J., 1999. Serotonin inhibition of synaptic transmission: GOA-1 decreases the abundance of UNC-13 at release sites. Neuron 24: 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Liu J., Nguyen T., Liu C., Sun J., et al. , 2013. The physiological role of mitochondrial calcium revealed by mice lacking the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nat. Cell Biol. 15: 1464–1472. 10.1038/ncb2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease S. E., Segal R. A., 2014. Preserve and protect: maintaining axons within functional circuits. Trends Neurosci. 37: 572–582. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer M., Kayzer E. B., Yang X., Abramson E., Kenaston M. A., et al. , 2011. Caenorhabditis elegans UCP4 protein controls complex II-mediated oxidative phosphorylation through succinate transport. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 37712–37720. 10.1074/jbc.M111.271452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell A. M., Youle R. J., 2015. The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 85: 257–273. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaraju V., Calloway N., Ryan T. A., 2014. Activity-driven local ATP synthesis is required for synaptic function. Cell 156: 825–835. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin E. B., Giaccia A. J., 2016. Hypoxic control of metastasis. Science 352: 175–180. 10.1126/science.aaf4405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson R. L., Yam L., Weimer R. M., Bend E. G., Hartwieg E., et al. , 2014. Axons degenerate in the absence of mitochondria in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 24: 760–765. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C. R., Chandel N. S., 2015. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 33: 8–13. 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R., Pinton P., Carrington W., Fay F. S., Fogarty K. E., et al. , 1998. Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science 280: 1763–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo G. J., Louie K., Wellington A., Macleod G. T., Hu F., et al. , 2009. Drosophila Miro is required for both anterograde and retrograde axonal mitochondrial transport. J. Neurosci. 29: 5443–5455. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5417-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar C. E., Dues D. J., Spielbauer K. K., Machiela E., Cooper J. F., et al. , 2015. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have opposing effects on lifespan. PLoS Genet. 11: e1004972 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber M., Chandel N. S., 2014. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 24: R453–R462. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz C., Kinge P., Hutter H., 2007. Axon guidance genes identified in a large-scale RNAi screen using the RNAi-hypersensitive Caenorhabditis elegans strain nre-1(hd20) lin-15b(hd126). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 834–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena L. A., Chandel N. S., 2012. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell 48: 158–167. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo-Matsuda N., Yasuda K., Tsuda M., Ohkubo T., Yoshimura S., et al. , 2001. A defect in the cytochrome b large subunit in complex II causes both superoxide anion overproduction and abnormal energy metabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 41553–41558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L. W., Niu R., Liu Y., 2016. Neuropeptide signals cell non-autonomous mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Cell Res. 26: 1182–1196. 10.1038/cr.2016.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpilka T., Haynes C. M., 2018. The mitochondrial UPR: mechanisms, physiological functions and implications in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19: 109–120. 10.1038/nrm.2017.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutov L. P., Kim M. S., Houlihan P. R., Medvedeva Y. V., Usachev Y. M., 2013. Mitochondria and plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase control presynaptic Ca2+ clearance in capsaicin-sensitive rat sensory neurons. J. Physiol. 591: 2443–2462. 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.249219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth D., Ch’ng Q., Dybbs M., Tavazoie M., Kennedy S., et al. , 2005. Systematic analysis of genes required for synapse structure and function. Nature 436: 510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth D., Madison J. M., Kaplan J. M., 2007. PKC-1 regulates secretion of neuropeptides. Nat. Neurosci. 10: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthammarak W., Somerlot B. H., Opheim E., Sedensky M., Morgan P. G., 2013. Novel interactions between mitochondrial superoxide dismutases and the electron transport chain. Aging Cell 12: 1132–1140. 10.1111/acel.12144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N., Inokuma K., Yasuda K., Ishii N., 1996. Cloning, sequencing and mapping of a manganese superoxide dismutase gene of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA Res. 3: 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot J. D., David G., Barrett E. F., 2003. Inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake affects phasic release from motor terminals differently depending on external [Ca2+]. J. Neurophysiol. 90: 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Zucker R. S., 1997. Mitochondrial involvement in post-tetanic potentiation of synaptic transmission. Neuron 18: 483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk J. M., 2015. Levels and location are crucial in determining the effect of ROS on lifespan. Worm 4: e1094607 10.1080/21624054.2015.1094607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk J. M., Hekimi S., 2009. Deletion of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase sod-2 extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000361 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk J. M., Hekimi S., 2012. Superoxide dismutase is dispensable for normal animal lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 5785–5790. 10.1073/pnas.1116158109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreken P., Ly C. V., Venken K. J., Koh T. W., Zhou Y., et al. , 2005. Synaptic mitochondria are critical for mobilization of reserve pool vesicles at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. Neuron 47: 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. L., Jiang B. H., Rue E. A., Semenza G. L., 1995. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 5510–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth J. L., Thayer S. A., 1994. Mitochondria buffer physiological calcium loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. 14: 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Chisholm A. D., 2014. C. elegans epidermal wounding induces a mitochondrial ROS burst that promotes wound repair. Dev. Cell 31: 48–60. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanase S., Onodera A., Tedesco P., Johnson T. E., Ishii N., 2009. SOD-1 deletions in Caenorhabditis elegans alter the localization of intracellular reactive oxygen species and show molecular compensation. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 64: 530–539. 10.1093/gerona/glp020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Hekimi S., 2010a A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 8: e1000556 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Hekimi S., 2010b Two modes of mitochondrial dysfunction lead independently to lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 9: 433–447. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee C., Yang W., Hekimi S., 2014. The intrinsic apoptosis pathway mediates the pro-longevity response to mitochondrial ROS in C. elegans. Cell 157: 897–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. Supplemental Material, Figure S1 and Figure S2 contain measurements of NLP-21 secretion in additional genotypes. Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.6849056.