Summary

Despite many beneficial outcomes of the conventional enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), several limitations such as the high-cost of the treatment and various inadvertent side effects including the occurrence of an immunological response against the infused enzyme and development of resistance to enzymes persist. These issues may limit the desired therapeutic outcomes of a majority of the lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs). Furthermore, the biodistribution of the recombinant enzymes into the target cells within the central nervous system (CNS), bone, cartilage, cornea, and heart still remain unresolved. All these shortcomings necessitate the development of more effective diagnosis and treatment modalities against LSDs. Taken all, maximizing the therapeutic response with minimal undesired side effects might be attainable by the development of targeted enzyme delivery systems (EDSs) as a promising alternative to the LSDs treatments, including different types of mucopolysaccharidoses ( MPSs ) as well as Fabry, Krabbe, Gaucher and Pompe diseases.

Keywords: Enzyme replacement therapies, Enzyme delivery systems, Targeted delivery systems, Lysosomal storage disorders, Mucopolysaccharidoses, Krabbe disease

Replacing the defective enzymes with a recombinant human enzyme in lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) and restoring the enzymatic activity was first proposed by Christian de Duve in 1964.1 The LSDs, as a heterogeneous group of disorders, are involved in various genetic defects.2 They are a group of 50-60 genetically inherited rare disorders, which are caused by the deficient activity of a specific lysosomal enzyme and the gradual accumulation of its non-degraded substrates, including sphingolipids, carbohydrates, glycogen, glycoproteins, and mucopolysaccharides.3 Lysosomal storage of substrates leads to a number of complications such as metabolic imbalances, widespread cellular dysfunction through cell signaling, communication alteration, and disruption of lipid rafts pathway, as well as downstream of autophagy processes.4 The LSDs patients during their early childhood suffer from multifaceted clinical symptoms that can affect their musculoskeletal system, lung, heart, liver, spleen, and eyes. In addition, most LSDs patients have mild to severe central nervous system (CNS) implications and they may even die in the early years of life owing to cardiorespiratory failures (Pompe disease).1

Various treatment strategies have been evaluated against the LSDs, including gene therapy, small molecule therapies, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), lysosome exocytosis, and organ/cell transplantation.5 Currently, ERT and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) have been advanced for the clinical trials, but due to the complicated nature of the LSDs, none of these methods addresses all aspects of the disease. Considering the effectiveness and limitations of each method when applied alone, combination of ERT and any other therapy is proposed in various studies to overcome these limitations.6 Up to now, several ERTs have been approved for the clinical applications in Gaucher, Fabry, Krabbe, and Pompe diseases, as well as different mucopolysaccharidoses MPSs (e.g., MPS I, II, and IV) as lysosomal storage disorders (Table 1).5 BioMarin Pharmaceutical Company is a global leader in developing and commercializing innovative biopharmaceuticals for the genetically derived rare diseases. Aldurazyme®, Vimzim®, and Naglazyme®, as recombinant human enzymes, have been produced by this company for the treatment of MPS I, IV, VI, respectively.

Table 1. Approved enzyme replacement therapies available for the lysosomal storage disorders .

| LSDs | Deficient enzyme | Inheritance | FDA approved ERT and Brand name |

|

MPS I (Hurler syn.) MPS II (Hunter syn.) MPS IV A (Morquio A syn.) MPS VI (Marateaux-Lamy syn.) |

α-L-iduronidase Iduronate sulfatase N-acetylgalactosamine 6-sulfatase N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfatase |

Autosomal X-linked Autosomal Autosomal |

Laronidase (Aldurazyme™)/ 2003-FDA, EMA Idursulfase (Elaprase™)/ 2006-FDA; 2007-EMA Elosulfase Alfa (Vimzim™)/ 2014-FDA Galsulfase (Naglazyme™)/ 2005-FDA; 2006-EMA |

| Fabry disease | α-galactosidase | X-linked |

Agalsidase α (Fabrazyme™)/ 2001-EMA Agalsidase β (Replagal™)/ 2003-FDA, EMA |

| Pompe diseas | α-glucosidase | Autosomal |

Aglucosidase (Myozyme™)/ 2006-FDA, EMA Aglucosidase (Lumizyme™)/ 2010-FDA |

| Gaucher disease | β -glucocerebrosidase | Autosomal |

Aglucerase (Ceredase™)/ 1991-FDA Imiglucerase (Cerezyme™)/ 1994-FDA; 1997-EMA Velaglucerase (VPRIV™)/ 2010-FDA, EMA Taliglucerase (Elelyso™)/ 2012-FDA |

| Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency | Lysosomal acid lipase | Autosomal | Sebelipase α (Kanuma™)/ 2015-FDA,EMA |

The intravenous (IV) administrations of approved enzymes in the LSDs generally represent significant clinical benefits, including improved walking ability, ameliorated respiration, and improved life-quality.7 The LSDs require continuous treatment for optimal clinical outcomes, therefore the cost-effectiveness and accessibility to ERT should be considered as an essential point in the treatment of these diseases. Despite the financial and regulatory advantages for the “orphan drug” in the U. S., pharmaceutical industries have priced the LSDs therapy products among the most expensive treatment modalities in the market. Unfortunately, due to the high-cost of ERT (usually over US$ 100 000/patient per year), they are not often accessible for countries with fewer fundings.8 Besides, the major impediment to the development of enzymes as drugs for the LSDs is the limited clinical trials due to patients paucity in the population. Furthermore, while performing pre-clinical studies in animal models has been strongly recommended, in most cases, due to the lack of such suitable animal models studies, the clinical trials have been performed directly in human patients.9

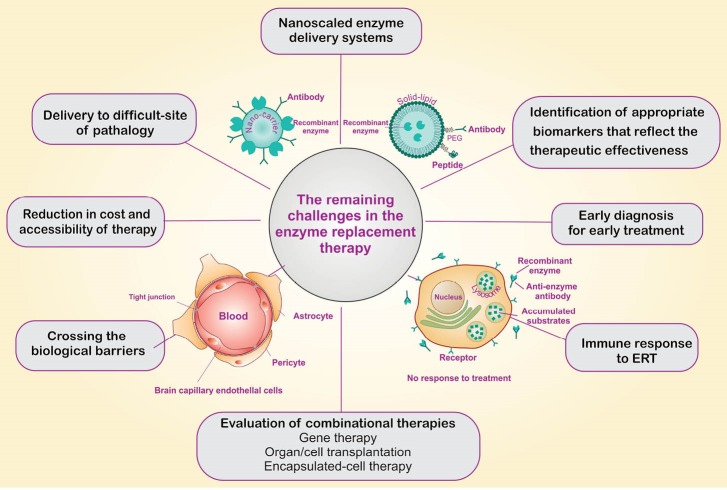

Immune response and the IgG antibodies (Abs) generation against the foreign infused enzymes is another considerable issue of the ERT, which plays a pivotal role in the patients' safety as well as efficacy and success of the treatment. In fact, the neutralizing Abs can reduce the efficacy of ERTs via direct interfering with the enzyme activity (Fig. 1). They can interact with the active site of the enzyme and/or ligands involved in the binding to a receptor on the target cells (mannose-6-phosphate receptors for most LSDs, mannose and lysosomal integral membrane protein 2 (Limp2) receptors for Gaucher disease) that lead to blocking the cellular uptake and lysosomal targeting of the enzyme.10 In addition, immune reactions intensity appears to be dependent on the presence or absence of residual mutant enzymes. Cross-reactive immunologic materials (CRIM) status may be predicted by genotyping for GAA gene in Pompe diseases, and initial/early immunomodulation may induce tolerance and result in an optimized therapy.7

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation for the remaining challenges in the enzyme replacement therapy.

Despite the therapeutic features of systemically-administered ERTs against LSDs, the biodistribution of the enzymes into the difficult sites of pathology (especially into CNS, bone, cartilage, cornea, and heart) still remains as a striking challenge. Further, in the MPS, the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in the cells and tissues all over the body result in devastating widespread dysfunctions in different tissues and organs. For instance, MPS manifestations in the eye include both the anterior segments (cornea, conjunctiva) and the posterior segments (retina, sclera, optic nerve).11 A clear evidence demonstrates that approximately 75% of LSDs patients with the neurological dysfunctions might not be treated with the available ERTs.12 The blood-brain barrier (BBB), as one of the main obstacles in the confrontation with the enzyme biodistribution, presents an impenetrable barrier between the bloodstream and the CNS, by which controls the inward and outward traverse of mostly hydrophilic enzymes utilized for the treatment of the LSDs selectively (Fig. 1).13,14 Further, as a result, ERT often fails to provide the desired clinical outcomes, in large part due to its non-specific biodistribution, low bioavailability, and high degradation rate. Therefore, enhancing the therapeutic response by the development of safe and efficient targeted enzyme delivery systems (EDSs) may provide a promising alternative to the currently used treatments in LSDs.15,16

Different methods have been developed to overcome the limited access of enzymes into the difficult pathological sites. Based on the receptor-mediated lysosomal enzyme delivery system, it has been shown that increasing the presence of M6P residues on the recombinant enzyme or enhancing the expression rate of the M6PRs on the target cells can improve the cellular uptake of the enzyme through active targeting mechanism.17,18

In recent years, unprecedented attention has been paid to the development of enzyme-loaded nanosystems (ENSs) using advanced nanobiomaterials to enhance the efficacy of ERT while minimizing the side effects.15 Different nanocarriers can be utilized for engineering of nanoscaled EDSs, including biodegradable nanomicelles, nanoliposomes, and polymer- and lipid-based nanoparticles (Fig. 1).19 Enzyme encapsulation can veil the enzyme and its physicochemical characteristics, which can eradicate some of the key limitations of ERT, including undesired immunologic reactions and biodegradation. It can also protect the recombinant enzymes from unwanted biological impacts, non-selective biodistribution, and improve the pharmacological response by increasing the drug absorption, controlled-release of enzyme supply, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD) properties.20,21

Besides, targeted NSs such as polymeric/lipidic nanoparticles, decorated with homing agents (e.g., aptamers or antibodies), can also be used in crossing the biological barriers such as BBB and blood-ocular-barrier (BOB). Thus, they are being considered as innovative and effective approaches for the treatment of brain disorders.12 In addition, encapsulated-cell therapy (ECT) along with another treatment strategy, has been considered as an interesting combined therapy method for the treatment of LSDs.22,23 One of the most pivotal advantages of ECT is to cover engineered cells by biocompatible devices that can be surgically implanted into different sites in the host body, especially in difficult-to-access sites such as the brain and eye to deliver constant amounts of the enzyme for prolonged periods of time.13 In the case of the eye, because of the efficient blockades provided by both epithelial and endothelial cells,24,25 the targeted delivery of drugs using advanced technologies and devices might provide great clinical outcomes.19 For example, thermos-responsive sol-gel injectable hydrogels offer great prospective applications in drug delivery, cell therapy and tissue engineering.26 It should be noted that some of these systems have mostly been used in the preclinical stages and the clinical researches are essential for the approval of their long-term safety and therapeutic outcomes.

Based on these findings, it is envisioned that the currently used ERT modalities are not completely effective for all types of LSDs. We envision that the ultimate therapy of LSDs in the future would be based on the gene and/or cell therapy. For example, in the case of Krabbe disease, AAVrh10 gene therapy has been shown to ameliorates the central and peripheral nervous system’s pathologies in murine and canine models of this disease.27 At this point, perhaps the main challenge in the treatment of LSDs is to deliver therapeutic agents to the diseased cells/tissue potentially using nanoscaled EDSs. Various multimodal nanomedicines have previously been developed against different types of diseases.28-42 Further, we know that the size and morphology of NSs can influence the pharmacokinetics and final fate of cargo drug molecules.43 Depending on the desired biological targets and impacts of the ERTs, the use of passive and active targeting mechanisms should be rationalized and fully addressed in the EDSs. Nevertheless, development of targeted NSs for enzyme delivery to CNS and other hard-to-reach tissue is considered as the main challenge. Vesicular trafficking mechanisms (e.g., clathrin-coated pits and membranous caveolae) in the LSDs should also be fully addressed. Lysosomal compartments, as acidic vesicular machineries of the cells, encompass over 60 different types of hydrolases and 50 membrane proteins and other biological machineries are involved in degradation of biological entities. We still need to understand the holistic roles of the lysosomal membrane transporters involved in the lysosomal trafficking.44 Interdigitating of lysosomal compartments with other cellular organelles seems to be largely dependent on the function of lysosomal ion channels and transporters, dysregulation of which might attribute to the pathogenesis of LSDs. We still need to know the roles of cell membrane vesicular entities such as lipid rafts and cytoplasmic macromolecules such as coat proteins in the vesicular trafficking of the cells. Likewise, to treat the LSDs, a number of issues in relevance to the genetics and/or epigenetics of the lysosomal compartments need to be understood. Taken all together, perhaps, it is the time to change our research perspective from a restricted outlook towards a holistic approach. To this end, we need to understand the hallmarks of the LSDs and their biochemical and clinical aspects to be able to improve patients’ well-being with more effective treatments. In this line, development of nanoscaled personalized medicines against LSDs appears to be an inevitable endeavor.

Ethical approval

There is none to be declared.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

The authors like to thank the scientific staff of the Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for their support.

Author's Biosketch

Mohammad Rafi received his PhD in Animal Biology from the University of Montpellier, France, in 1970. He taught Cell and Molecular Biology for over 17 years at the School of Science, Tabriz University, Iran, where he also served as Chair of the Department of Animal Biology. He is currently a Professor of Neurology in the Department of Neurology with a joint appointment in the Department of Neurosciences at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, USA. Though he has worked on several lysosomal storage diseases, his main research interest is gene therapy of neurodegenerative disorders using animal models of globoid cell leukodystrophy (Krabbe disease). With successful AAVrh10-mediated treatment of murine and canine models, his research is moving towards the treatment trials of human patients.

References

- 1.Desnick RJ, Schuchman EH. Enzyme replacement therapy for lysosomal diseases: lessons from 20 years of experience and remaining challenges. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2012;13:307–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090711-163739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenger DA, Luzi P, Rafi MA. Lysosomal storage diseases: heterogeneous group of disorders. Bioimpacts. 2013;3:145–7. doi: 10.5681/bi.2013.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Futerman AH, van Meer G. The cell biology of lysosomal storage disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:554–65. doi: 10.1038/nrm1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muro S. Strategies for delivery of therapeutics into the central nervous system for treatment of lysosomal storage disorders. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2012;2:169–86. doi: 10.1007/s13346-012-0072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon M, Muro S. Lysosomal enzyme replacement therapies: Historical development, clinical outcomes, and future perspectives. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;118:109–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkegaard T. Emerging therapies and therapeutic concepts for lysosomal storage diseases. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2013;1:385–404. doi: 10.1517/21678707.2013.780970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kishnani PS, Dickson PI, Muldowney L, Lee JJ, Rosenberg A, Abichandani R. et al. Immune response to enzyme replacement therapies in lysosomal storage diseases and the role of immune tolerance induction. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;117:66–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herder M. What Is the Purpose of the Orphan Drug Act? PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boudes PF. Clinical studies in lysosomal storage diseases: Past, present, and future. Rare Dis. 2013;1:e26690. doi: 10.4161/rdis.26690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le SQ, Kan SH, Clarke D, Sanghez V, Egeland M, Vondrak KN. et al. A Humoral Immune Response Alters the Distribution of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Murine Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;8:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willoughby C, Ponzin D, Ferrari S, Lobo A, Landau K, Omidi Y. Anatomy and physiology of the human eye: effects of mucopolysaccharidoses disease on structure and function – a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;38:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02363.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvalaio M, Rigon L, Belletti D, D'Avanzo F, Pederzoli F, Ruozi B. et al. Targeted Polymeric Nanoparticles for Brain Delivery of High Molecular Weight Molecules in Lysosomal Storage Disorders. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barar J, Rafi MA, Pourseif MM, Omidi Y. Blood-brain barrier transport machineries and targeted therapy of brain diseases. Bioimpacts. 2016;6:225–48. doi: 10.15171/bi.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardridge WM. Biopharmaceutical drug targeting to the brain. J Drug Target. 2010;18:157–67. doi: 10.3109/10611860903548354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuh RS, Baldo G, Teixeira HF. Nanotechnology applied to treatment of mucopolysaccharidoses. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13:1709–18. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2016.1202235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin-Banderas L, Holgado MA, Duran-Lobato M, Infante JJ, Alvarez-Fuentes J, Fernandez-Arevalo M. Role of Nanotechnology for Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Lysosomal Diseases A Focus on Gaucher's Disease. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:929–52. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160210130608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koeberl DD, Luo X, Sun B, McVie-Wylie A, Dai J, Li S. et al. Enhanced efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in Pompe disease through mannose-6-phosphate receptor expression in skeletal muscle. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;103:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y, Li X, Schuchman EH, Desnick RJ, Cheng SH. Dexamethasone-mediated up-regulation of the mannose receptor improves the delivery of recombinant glucocerebrosidase to Gaucher macrophages. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:705–11. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barar J, Aghanejad A, Fathi M, Omidi Y. Advanced drug delivery and targeting technologies for the ocular diseases. Bioimpacts. 2016;6:49–67. doi: 10.15171/bi.2016.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muro S. New biotechnological and nanomedicine strategies for treatment of lysosomal storage disorders. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2010;2:189–204. doi: 10.1002/wnan.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tam VH, Sosa C, Liu R, Yao N, Priestley RD. Nanomedicine as a non-invasive strategy for drug delivery across the blood brain barrier. Int J Pharm. 2016;515:331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakama H, Ohsugi K, Otsuki T, Date I, Kosuga M, Okuyama T. et al. Encapsulation cell therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis type VII using genetically engineered immortalized human amniotic epithelial cells. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;209:23–32. doi: 10.1620/tjem.209.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldo G, Quoos Mayer F, Burin M, Carrillo-Farga J, Matte U, Giugliani R. Recombinant encapsulated cells overexpressing alpha-L-iduronidase correct enzyme deficiency in human mucopolysaccharidosis type I cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;195:323–9. doi: 10.1159/000327532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barar J, Asadi M, Mortazavi-Tabatabaei SA, Omidi Y. Ocular Drug Delivery; Impact of in vitro Cell Culture Models. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2009;4:238–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barar J, Javadzadeh AR, Omidi Y. Ocular novel drug delivery: impacts of membranes and barriers. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:567–81. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.5.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fathi M, Barar J, Aghanejad A, Omidi Y. Hydrogels for ocular drug delivery and tissue engineering. Bioimpacts. 2015;5:159–64. doi: 10.15171/bi.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rafi MA, Rao HZ, Luzi P, Luddi A, Curtis MT, Wenger DA. Intravenous injection of AAVrh10-GALC after the neonatal period in twitcher mice results in significant expression in the central and peripheral nervous systems and improvement of clinical features. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;114:459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.12.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heidari Majd M, Asgari D, Barar J, Valizadeh H, Kafil V, Coukos G. et al. Specific targeting of cancer cells by multifunctional mitoxantrone-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles. J Drug Target. 2013;21:328–40. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2012.750325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heidari Majd M, Asgari D, Barar J, Valizadeh H, Kafil V, Abadpour A. et al. Tamoxifen loaded folic acid armed PEGylated magnetic nanoparticles for targeted imaging and therapy of cancer. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;106:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barar J, Kafil V, Majd MH, Barzegari A, Khani S, Johari-Ahar M. et al. Multifunctional mitoxantrone-conjugated magnetic nanosystem for targeted therapy of folate receptor-overexpressing malignant cells. J Nanobiotechnology. 2015;13:26. doi: 10.1186/s12951-015-0083-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johari-Ahar M, Barar J, Alizadeh AM, Davaran S, Omidi Y, Rashidi MR. Methotrexate-conjugated quantum dots: synthesis, characterisation and cytotoxicity in drug resistant cancer cells. J Drug Target. 2016;24:120–33. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2015.1058801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahmanian N, Eskandani M, Barar J, Omidi Y. Recent trends in targeted therapy of cancer using graphene oxide-modified multifunctional nanomedicines. J Drug Target. 2017;25:202–15. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2016.1238475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Same S, Aghanejad A, Akbari Nakhjavani S, Barar J, Omidi Y. Radiolabeled theranostics: magnetic and gold nanoparticles. Bioimpacts. 2016;6:169–81. doi: 10.15171/bi.2016.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fathi M, Zangabad PS, Aghanejad A, Barar J, Erfan-Niya H, Omidi Y. Folate-conjugated thermosensitive O-maleoyl modified chitosan micellar nanoparticles for targeted delivery of erlotinib. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;172:130–41. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranjbar-Navazi Z, Eskandani M, Johari-Ahar M, Nemati A, Akbari H, Davaran S. et al. Doxorubicin-conjugated D-glucosamine- and folate- bi-functionalised InP/ZnS quantum dots for cancer cells imaging and therapy. J Drug Target. 2018;26:267–77. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2017.1365876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zamanlu M, Farhoudi M, Eskandani M, Mahmoudi J, Barar J, Rafi M. et al. Recent advances in targeted delivery of tissue plasminogen activator for enhanced thrombolysis in ischaemic stroke. J Drug Target. 2018;26:95–109. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2017.1365874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fathi M, Sahandi Zangabad P, Majidi S, Barar J, Erfan-Niya H, Omidi Y. Stimuli-responsive chitosan-based nanocarriers for cancer therapy. Bioimpacts. 2017;7:269–77. doi: 10.15171/bi.2017.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandghanooni S, Eskandani M, Barar J, Omidi Y. Recent advances in aptamer-armed multimodal theranostic nanosystems for imaging and targeted therapy of cancer. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2018;117:301–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakhlband A, Eskandani M, Omidi Y, Saeedi N, Ghaffari S, Barar J. et al. Combating atherosclerosis with targeted nanomedicines: recent advances and future prospective. Bioimpacts. 2018;8:59–75. doi: 10.15171/bi.2018.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fathi M, Majidi S, Zangabad PS, Barar J, Erfan-Niya H, Omidi Y. Chitosan-based multifunctional nanomedicines and theranostics for targeted therapy of cancer. Med Res Rev. 2018 doi: 10.1002/med.21506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthaiou EI, Barar J, Sandaltzopoulos R, Li C, Coukos G, Omidi Y. Shikonin-loaded antibody-armed nanoparticles for targeted therapy of ovarian cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:1855–70. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S51880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omidi Y, Barar J. Targeting tumor microenvironment: crossing tumor interstitial fluid by multifunctional nanomedicines. Bioimpacts. 2014;4:55–67. doi: 10.5681/bi.2014.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barar J. Bioimpacts of nanoparticle size: why it matters? Bioimpacts. 2015;5:113–5. doi: 10.15171/bi.2015.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu H, Ren D. Lysosomal physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:57–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]