Abstract

Patients with haematological malignancy are often profoundly immune suppressed, and more so if they require more than one line of therapy. Infection should always be considered when they become unwell. We discuss the differential diagnoses of a young man with multiply-relapsed Philadelphia chromosome-positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia who presented with neurological symptoms and cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis. The diagnostic approach needs to be rapid and structured, and may require microbiology and neurology support.

Keywords: CSF lymphocytosis, Lymphocytic pleocytosis, Varicella zoster encephalitis, Inotuzumab, Relapsed leukemia

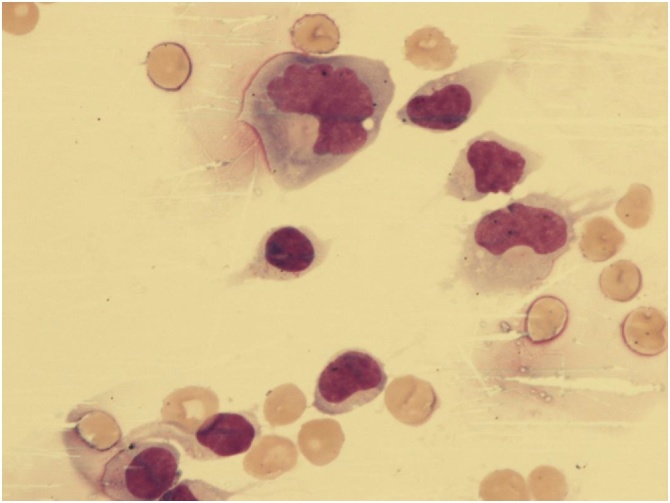

A 26-year old gentleman with Philadelphia Chromosome-positive common B-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) in his third remission presented with headache and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lymphocytosis four months after inotuzumab ozogamicin treatment. Microscopic images of his CSF are shown (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

High power image of the patient’s Cerebrospinal fluid (×1000).

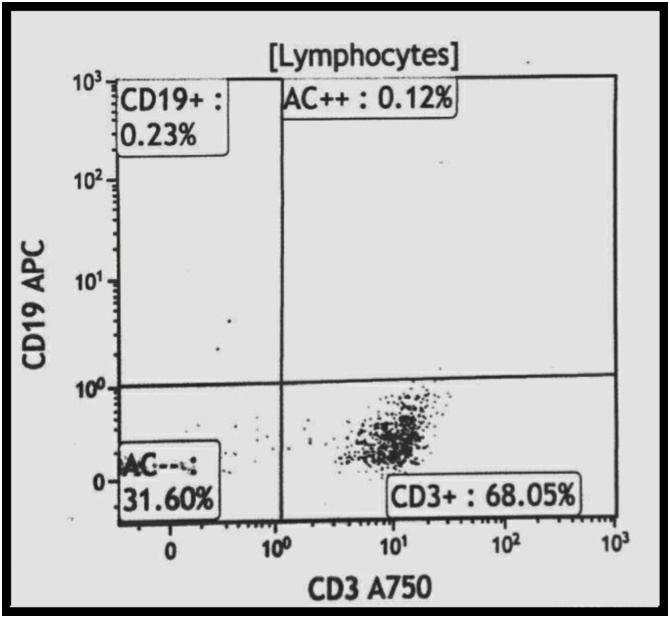

Our first differential was relapse of his disease, but morphology was not consistent. Flow cytometry confirmed an infiltrate by T- rather than B-lymphocytes (Fig. 2). MRI scanning of the brain showed increased signal hyperintensity in the left superior frontal gyrus on T2-weighted imaging.

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometry plots of the Cerebrospinal fluid. The lymphocytic infiltrate expressed CD3 and not CD19.

An experienced morphologist will suspect non-leukaemic etiology early, and infective causes are particularly important to exclude in this significantly immune-suppressed population. Herpes simplex, varicella zoster, cytomegalovirus, cryptococcal meningitis, neurosyphilis and lyme disease are all important considerations. Herpetic infection may be accompanied by a vesicular rash, but this is not always the case [2], [4]. Cytomegalovirus often causes multisystem infection, and serology and CMV viral load will confirm the diagnosis. Cryptococcus and Treponema are found world-wide and should always be considered. Lyme disease has been reported widely in the UK and may be suspected by the astute physician if the history of tick bite and a typical rash are elicited. Bacterial infection is also part of the differential of CSF lymphocytosis, but more commonly causes a neutrophilic infiltrate.

Non-infective inflammatory differentials are also possible in patients with a history of leukemia, and testing CSF for oligoclonal bands and serology for autoantibodies is advised. The support of neurology is important. Chemical meningitis can occasionally occur after intrathecal chemotherapy. Multiple sclerosis can occur and may not have a typical relapsing history at a first presentation, but is often associated with suggestive MRI appearances and oligoclonal bands on CSF. Susac's syndrome is a rare possibility, usually affecting young women and causing encephalopathy and visual changes. It is thought to be an immune-mediated endotheliopathy [1]. Autoimmune encephalopathy is a condition that presents acutely, and may be associated with serologic evidence of autoimmunity, non-specific slowing on electroencephalography and leptomeningeal enhancement on MRI. Benign recurrent lymphocytic meningitis and pseudomigraine are conditions characterized by recurrent episodes of headache and temporary neurological deficit - it is suggested they have a viral etiology [3].

Further testing confirmed varicella-zoster DNA by PCR in our patient's CSF and he received high dose acyclovir, making a complete recovery. Our case illustrates the importance of non-malignant differentials in this cohort of patients even when the risk of leukemia relapse is thought to be high.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Sources of funding

None

Consent

Written and signed consent taken.

Author contribution

Dr. Thomas Lofaro – Data Collection, Data Analysis and Writing.

Dr. Aritra Saha - Data Collection and Writing.

Dr. Richard Dillon – Study Design.

Dr. Kavita Raj – Study Design.

Contributor Information

Thomas Lofaro, Email: thomas.lofaro@nhs.net.

Aritra Saha, Email: aritraofficial@gmail.com.

Kavita Raj, Email: kavita.raj@nhs.net.

Richard Dillon, Email: richarddillon@nhs.net.

References

- 1.Kleffner I., Dörr J., Ringelstein M., Gross C.C., Böckenfeld Y., Schwindt W. Diagnostic criteria for Susac syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(December (12)):1287–1295. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314295. Epub 2016 Oct 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilden D.H., Lipton H.L., Wolf J.S., Akenbrandt W., Smith J.E., Mahalingam R. Two patients with unusual forms of varicella-zoster virus vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(November (19)):1500–1503. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascual J., Valle N. Pseudomigraine with lymphocytic pleocytosis. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2003;7(June (3)):224–228. doi: 10.1007/s11916-003-0077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagel Maria A., Gilden Don. Neurological complications of VZV reactivation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27(June (3)):356–360. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]